Abstract

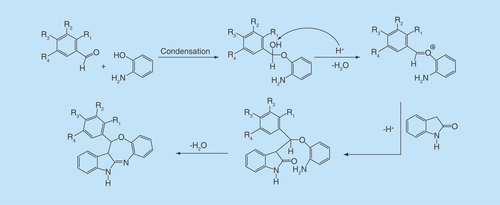

Aim: A new series of compounds (1a–16a) bearing indole-fused benzooxazepine was synthesized, characterized and evaluated for anticancer activity. Materials & methods: In this study, all the synthesized compounds were screened via in vitro anticancer testing on Hep-G2 cancer cell line. A computational study was carried out on cancer-related targets including IL-2, IL-6, COX-2 Caspase-3 and Caspase-8. Results: Some of the synthesized compounds effectively controlled the growth of cancerous cells. Conclusion: The most active compounds – 6a, 10a, 13a, 14a and 15a – exemplify notable anticancer profile with GI50 <10 μg/ml. Preliminary structure–activity relationship among the tested compounds can produce an assumption that the electronegative groups at phenyl ring attached with indole-fused benzooxazepine are instrumental for the activity. Molecular docking study showed crucial hydrogen bond and π–π stacking interactions, with good ADMET profiling and molecular dynamic simulation.

Lay abstract Indole, azepine and six-membered flexible rings are getting much attention for cancer drug discovery. To contribute to the development of drugs for liver cancer, we designed a new structural class of compounds, indole-fused benzooxazepines. All the compounds were subjected to a preliminary bioassay analysis against Hep-G2 cancer cell line to determine their effect. Studies were also performed on various cancer-related targets to understand the mechanism of action. Our findings show that five compounds were of remarkable efficacy and warrant further investigation.

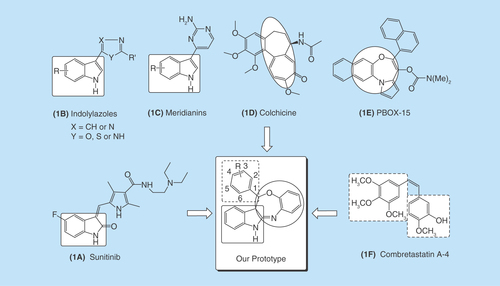

Graphical Abstract

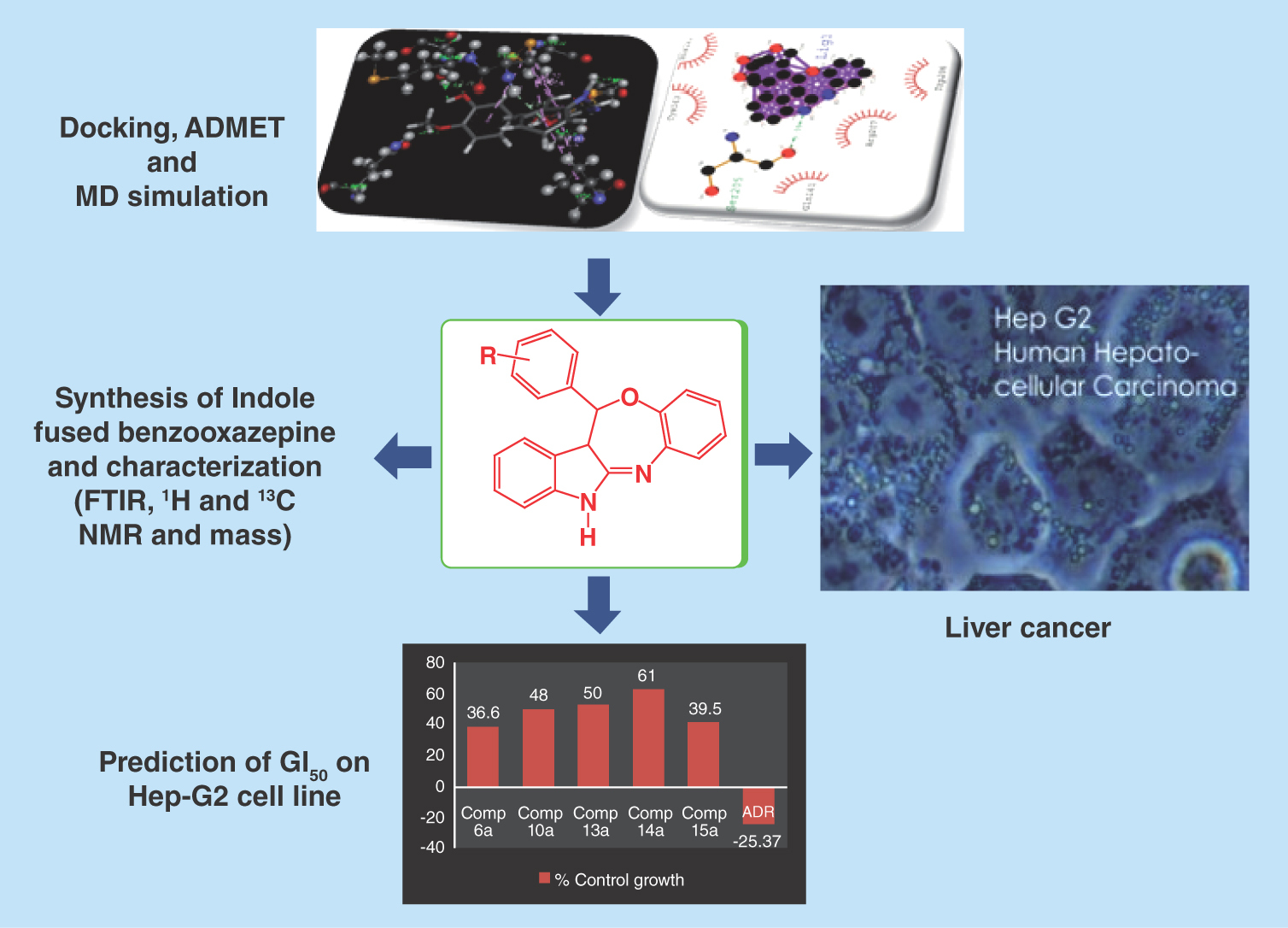

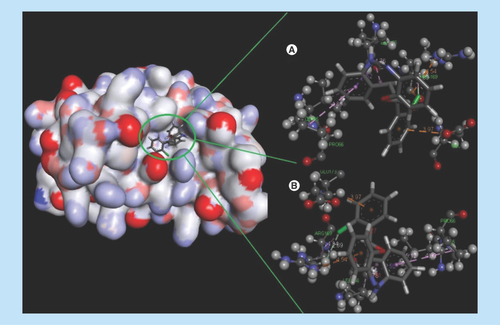

Figure 4. Docking complex of 14a with IL-6.

(A) Structural conformational changes before MD simulation. (B) Structural conformational changes after MD simulation: Back bone of active site domain complex, which indicates the contraction of ligand with amino acids residue.

MD: Molecular dynamic.

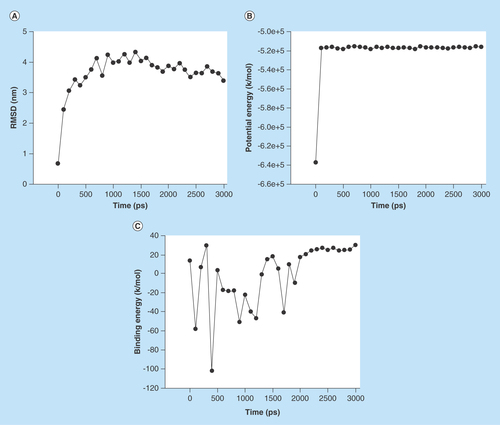

Figure 5. The stability profile of ligand–protein complex under the molecular dynamic simulation.

(A) Average RMSD versus time graph that indicates convergence of the simulated structure toward an equilibrium state with respect to a reference structure (starting structure). (B) Potential energy of complex versus time graph that indicates the stability of ligand–protein complex and (C) Binding energy of complex versus time graph that also indicates stability of ligand–protein complex.

RMSD: Root-mean-square deviation.

Liver cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide, and accounts for more than 600,000 deaths every year. The majority of patients with liver cancer die within a year after diagnosis [Citation1]. The most common form of liver cancer in adults is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which generally starts as a single tumor that grows larger or as many small cancer nodules throughout the liver. There is currently a demand for the discovery and development of new lead compounds of simple structure, exhibiting excellent antitumor property and new mechanisms of action [Citation2].

Indole scaffold is one of the most widely reputed structural units used to identify new drug candidates as antiproliferative agents. A representative member of this class is sunitinib (), which is currently used in clinics as a multitargeting tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumor [Citation3]. Besides this, a diverse variety of indolylazoles (), such as labradorins 1 and 2 and indolylthiazoles, are known for their cytotoxic activities against human lung cancer. Marine indole alkaloids, meridianins () and their synthetic analogs, have shown prominent anticancer activities against breast cancer [Citation4,Citation5].

The interest in seven-membered heterocycles among synthetic chemists and pharmacologists has increased persistently not only because of the variety of bioactivities but also due to high reactivity and some ubiquitous properties of these compounds. The naturally occurring antimitotic agent colchicine () and its synthetic analogs have been studied extensively for cancer chemotherapy, however, it lacks in vivo anticancer efficacy at its maximum-tolerated dose [Citation6] because its maximum-tolerated dose is limited to around 1 mg/kg [Citation7]. Azepine analogs such as oxazepine have been subject to much investigation, since they are a class of totally synthetic pharmacological agents with diverse action [Citation2,Citation8]. Recently, pyrrolo-1,5-benzoxazepine, a well-known group of microtubule-targeting agents, was shown to display antitumor effects, mainly inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in several human cancer models [Citation9]. A member of this family, pyrrolo-1,5-benzoxazepine-15 (), has shown potent pro-apoptotic activity in a variety of human tumor cell types including liver (Hep-G2), breast (MCF7) and colon (HCT116) cancer cell lines, with minimal toxicity toward normal blood and bone marrow cells [Citation9,Citation10]. A cis-stilbene natural product combretastatin A-4 () is a lead compound of vascular-disrupting agents targeting tumor blood vessels that binds to the colchicine site and exerts potent cytotoxicity, particularly due to having a cis-configuration-linking bridge and two relatively flexible six-membered hydrophobic rings with the appropriate dihedral angle [Citation11–13].

According to the rational approach of drug designing, the fusion/attachment of relevant heterocyclic rings within a single structural framework can result in a novel scaffold of interest with enhanced biological activity. Thus, inspired by the aforementioned promising findings and the rational approach of drug designing, a novel series of compounds containing an indole moiety directly attached to benzooxazepine with a relatively flexible six-membered hydrophobic ring in a single-molecular framework have been designed and synthesized to establish an important pharmacophoric structure with powerful anticancer potentials. These have further been evaluated for their anticancer activity via in vitro screening on the Hep-G2 cell line and molecular docking study with ADMET profiling and molecular dynamic (MD) simulation at Caspase-3, Caspase-8, IL-2, IL-6 and COX-2 receptor site to establish the molecular mechanism of the title compounds. A feasible one-pot-efficient synthetic approach was employed for the synthesis of the proposed derivatives. Some representative chemical structures of important compounds possessing indole, seven-membered ring, benzooxazepine, six-membered flexible ring and our synthesized prototype containing these fragments have been presented in , which possibly endows better complementarity with the receptor molecule.

Materials & methods

General

The chemicals and reagents were procured from Sigma-Aldrich chemicals and used without further purification. The progress of the reaction was monitored by thin layer chromatography on silica gel G plates using iodine vapors and UV light as visualizing agents. Melting points were determined by open capillary method and are uncorrected. After physical characterization, the compounds were subjected to spectral analysis. The IR spectra were recorded on Perkin Elmer RX1 FTIR spectrophotometer using KBr discs and the values are expressed in per centimeter and only noteworthy absorption levels are listed. The positive mode of ESI-MS spectra was recorded on Waters UPLC TQD mass spectrometer at CDRI, Lucknow. The NMR (1H and 13C NMR) spectra were recorded at 400 and 100 MHz on a Bruker DRX300 model spectrometer at CDRI, Lucknow. The chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (δ values), using TMS as the internal standard.

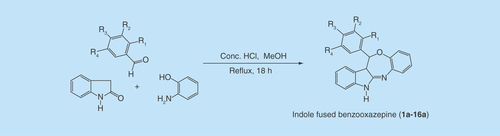

Chemistry

In view of few one-pot synthetic methodologies of azepine moiety using acidic catalysts [Citation14–17], we inspired to prepare our designed compounds by one-pot-efficient synthetic route, which is delineated in . By adopting the reported procedures of the Biginelli reaction [Citation18–20], indolin-2-one, an aromatic aldehyde and 2-amino phenol underwent an acid-catalyzed, three-component reaction to constitute a rapid and facile synthesis of indole-fused benzooxazepines (1a–16a). The possible mechanism of the reaction is delineated in . The first step in the mechanism is believed to be the condensation between the aldehyde and 2-amino phenol. The intermediate so-generated acts as an electrophile for the nucleophilic addition on the methylene group of indolin-2-one, presumably through the formation of enol tautomer. The resulting adduct undergoes condensation between >C = O and NH2 to give the cyclized product. The mechanism is somewhat similar to the Biginelli reaction.

Finally, structures of the synthesized compounds were established by IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR spectroscopy and MS. The formation of indole-fused benzooxazepine derivatives was supported by the presence of –N = C and >C–O–C< stretching band (1600–1700 and 1200–1300 cm-1), and absence of –OH stretching band (3500–3600 cm-1) in the IR spectra. In addition, appearance of two azepinic >CH– peaks in aliphatic region (δ = 1.5–4.0) of 1H NMR spectra also confirms the formation of oxazepine ring in the reaction. Furthermore, mass spectra were used to confirm the assigned molecular weight of compounds in form of their stable fragments.

An efficient one-pot reaction procedure was employed to afford the titled compounds. A solution of 2-oxindole (0.40 g, 3.0 mmol), appropriate aromatic aldehyde (3.0 mmol) and 2-amino phenol (0.327 g, 3.0 mmol) in methanol (15 ml) with catalytic amount of conc. HCl (1.5 ml) was placed in 100-ml round-bottom flask and heated under reflux for 18 h approximately. The progress of reaction was monitored by TLC, using the solvent system ethyl acetoacetate:n-hexane (4:6). After completion of the reaction, the mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature overnight. The solid products so-formed were collected by filtration, dried and recrystallized with methanol. All the products thus obtained physically appeared as pure needle-shaped bright crystals, giving a single spot on the TLC plate.

12-Phenyl-12,12a-dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indole (1a)

Yield: 72%; Melting range (°C): 184–188; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3078.7 (N–H str), 1706.9 (C = N str), 1328.2 (C–N str), 1232.2 (C–O–C str), 1463.2 (C = C str, aromatic), 3149.9 (C–H str, aromatic), 1613.5 (N–H bend); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 8.09 (s, 1H, –NH–), 7.84 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.65 (dd, 3H, ArH), 7.47 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.25 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.21 (t, 1H, ArH), 6.87 (dd, 2H, ArH), 7.04 (t, 1H, ArH), 3.49 (s, 1H, >CH–), 1.60 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 170.09, 159.82, 141.63, 137.80, 135.08, 132.19, 130.11, 129.89, 129.53, 128.89, 128.54, 127.64, 123.33, 122.10, 122.00, 119.50, 110.27, 109.68; MS (EI): m/z 313.2 [M+1]+ (15), 221.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

4-(12,12a-Dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indol-12-yl)phenol (2a)

Yield: 68%; Melting range (°C): 193–195; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3203.5 (N–H str), 1680.9 (C = N str), 1339.0 (C–N str), 1229.6 (C–O–C str), 1463.7 (C = C str, aromatic), 3203.5 (C–H str, aromatic), 1583.4 (N–H bend), 3203.5 (O–H str); 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 10.49 (s, 1H, –NH–), 10.11 (s, 1H, ArH), 8.37 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.65 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.57 (d, 2H, ArH), 7.51 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.17 (t, 2H, ArH), 6.84 (dd, 4H, ArH), 3.42 (s, 1H, –OH), 3.37 (s, 1H, >CH–), 3.14 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (DMSO-d 6, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 169.60, 159.85, 143.03, 137.14, 135.36, 132.37, 129.94, 125.53, 125.19, 122.57, 121.86, 121.54, 119.53, 116.18, 115.75, 110.47, 109.63; MS (EI): m/z 329.4 [M+1]+ (11), 237.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

3-(12,12a-Dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indol-12-yl)phenol (3a)

Yield: 60%; Melting range (°C):196–198; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3020.9 (N–H str), 1684.3 (C = N str), 1335.6 (C–N str), 1224.5 (C–O–C str), 1463.9 (C = C str, aromatic), 3020.9 (C–H str, aromatic), 1615.6 (N–H bend), 3170.2 (O–H str); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 8.27 (s, 1H, –NH–), 7.75 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.63 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.51 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.34 (t, 3H, ArH), 7.21 (d, 3H, ArH), 7.09 (s, 1H, ArH), 6.859 (m, 2H, ArH), 5.02 (s, 1H, –OH), 3.49 (s, 1H, >CH–), 2.17 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 172.05, 162.05, 144.05, 137.14, 135.36, 132.37, 129.94, 125.53, 125.19, 122.57, 121.86, 121.54, 119.53, 116.18, 115.75, 110.46, 109.62; MS (EI): m/z 329.4 [M+1]+ (16), 237.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

12-(4-Chlorophenyl)-12,12a-dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indole (4a)

Yield: 70%; Melting range (°C): 181–184; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3487.0 (N–H str), 1711.0 (C = N str), 1327.2 (C–N str), 1204.4 (C–O–C str), 1463.2 (C = C str, aromatic), 3176.1 (C–H str, aromatic), 1612.8 (N–H bend), 742.4(C–Cl str); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 8.79 (s, 1H, –NH–), 8.23 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.75 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.59 (dd, 3H, ArH), 7.47 (m, 3H, ArH), 7.22 (m, 1H, ArH), 7.03 (t, 1H, ArH), 6.92 (m, 2H, ArH), 3.52 (s, 1H, >CH–), 1.71 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 170.32, 141.98, 140.05, 136.17, 136.08, 135.78, 133.50, 132.46, 130.86, 130.40, 129.42, 129.22, 128.76, 128.31, 123.22, 122.16, 121.65, 119.60, 110.60, 109.94; MS (EI): m/z 347.9 [M+1]+ (19), 255.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

12-(4-Bromophenyl)-12,12a-dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indole (5a)

Yield: 80%; Melting range (°C): 166–169; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3480.8 (N–H str), 1701.4 (C = N str), 1334.1 (C–N str), 1209.2 (C–O–C str), 1460.2 (C = C str, aromatic), 3178.5 (C–H str, aromatic), 1616.5 (N–H bend), 741.2(C–Br str); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 8.32 (s, 1H, –NH–), 8.13 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.72 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.59 (m, 6H, ArH), 7.23 (t, 1H, ArH), 7.04 (t, 1H, ArH), 6.88 (dd, 2H, ArH), 1.63 (s, 2H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 169.99, 141.83, 136.10, 133.96, 133.62, 132.20, 131.76, 131.04, 130.43, 128.24, 124.07, 123.28, 122.20, 121.68, 110.50, 109.86; MS (EI): m/z 392.1 [M+1]+ (22), 301.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

12-(4-Fluorophenyl)-12,12a-dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indole (6a)

Yield: 65%; Melting range (°C): 167–170; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3143.3 (N–H str), 1706.2 (C = N str), 1328.0 (C–N str), 1221.0 (C–O–C str), 1463.0 (C = C str, aromatic), 3071.3 (C–H str, aromatic), 1613.8 (N–H bend), 1160.4 (C–F str); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 8.96 (s, 1H, –NH–), 8.33 (t, 1H, ArH), 7.78 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.66 (q, 2H, ArH), 7.58 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.50 (t, 1H, ArH), 7.14 (m, 4H, ArH), 6.88 (dd, 2H, ArH), 3.49 (s, 1H, >CH–), 1.77 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 170.56, 164.76, 162.27, 141.96, 136.45, 134.64, 131.66, 130.24, 129.17, 127.84, 123.05, 122.09, 121.75, 119.42, 116.21, 115.99, 110.62, 109.92; MS (EI): m/z 331.2 [M+1]+ (8), 239.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

12-(3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl)-12,12a-dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indole (7a)

Yield: 77%; Melting range (°C): 167–170; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3688.0 (N–H str), 1691.1 (C = N str), 1336.0 (C–N str), 1250.9 (C–O–C str), 1466.5 (C = C str, aromatic), 3169.0 (C–H str, aromatic), 2940.2 (C–H str, aliphatic), 1570.7 (N–H bend); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 8.12 (s, 1H, –NH–), 7.81 (dd, 2H, ArH), 7.51 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.47 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.22 (t, 1H, ArH), 7.05 (t, 1H, ArH), 6.92 (m, 3H, ArH), 3.88 (m, 9H, 3–OCH3), 1.61 (s, 2H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 170.16, 168.15, 153.52, 152.95, 141.71, 139.73, 138.25, 137.87, 130.27, 129.53, 128.87, 126.90, 125.84, 123.42, 122.06, 121.97, 119.28, 110.37, 109.67, 107.04, 61.28, 56.49; MS (EI): m/z 403.4 [M+1]+ (14), 312.0 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

12-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-12,12a-dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indole (8a)

Yield: 66%; Melting range (°C): 187–190; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3074.0 (N–H str), 1701.7 (C = N str), 1329.8 (C–N str), 1174.0 (C–O–C str), 1462.0 (C = C str, aromatic), 3147.3 (C–H str, aromatic), 2835.9 (C–H str, aliphatic), 1604.0 (N–H bend); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 9.45 (s, 1H, –NH–), 9.06 (s, 1H, ArH), 8.35 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.79 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.73 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.65 (d, 2H, ArH), 7.48 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.19 (dd, 1H, ArH), 7.00 (m, 3H, ArH), 6.88 (t, 1H, ArH), 3.86 (s, 3H, –OCH3), 3.51 (s, 1H, >CH–), 2.09 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 171.24, 168.81, 161.83, 141.83, 139.68, 137.88, 134.68, 131.73, 129.62, 128.40, 127.40, 126.05, 125.94, 124.17, 122.81, 121.85, 118.94, 114.29, 113.99, 110.55, 109.81, 55.59; MS (EI): m/z 343.3 [M+1]+ (17), 251.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

12-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-12,12a-dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indole (9a)

Yield: 65%; Melting range (°C): 188–190; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3148.5 (N–H str), 1714.8 (C = N str), 1464.9 (C–N str), 1274.4 (C–O–C str), 1431.1 (C = C str, aromatic), 3077.6 (C–H str, aromatic), 2947.4 (C–H str, aliphatic), 1609.4 (N–H bend); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 9.34 (s, 1H, –NH–), 8.31 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.81 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.65 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.53 (t, 1H, ArH), 7.38 (m, 1H, ArH), 7.18 (m, 3H, ArH), 6.98 (m, 4H, ArH), 3.91 (s, 1H, >CH–), 3.83 (s, 3H, –OCH3), 1.96 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 170.87, 168.62, 159.87, 142.08, 140.10, 137.88, 136.33, 135.29, 130.12, 129.95, 128.11, 126.85, 125.50, 123.44, 121.99, 119.46, 117.92, 115.96, 114.47, 110.59, 109.97, 55.56; MS (EI): m/z 343.2 [M+1]+ (14), 251.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

5-(12,12a-Dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indol-12-yl)-2-methoxyphenol (10a)

Yield: 81%; Melting range (°C): 194–197; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3170.3 (N–H str), 1686.8 (C = N str), 1466.2 (C–N str), 1204.9 (C–O–C str), 1438.4 (C = C str, aromatic), 3037.4 (C–H str, aromatic), 2893.1 (C–H str, aliphatic), 1618.9 (N–H bend), 3391.8 (O–H str); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 8.91 (s, 1H, –NH–), 7.79 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.76 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.60 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.48 (t, 1H, ArH), 7.28 (dd, 1H, ArH), 7.20 (t, 2H, ArH), 7.02 (m, 2H, ArH), 6.88 (m, 2H, ArH), 4.03 (s, 1H, –OH), 3.97 (s, 1H, >CH–), 3.92 (s, 3H, –OCH3), 3.47 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 170.76, 168.10, 159.87, 147.54, 146.51, 141.22, 139.77, 138.34, 129.68, 127.16, 124.32, 123.05, 121.97, 117.90, 114.93, 112.20, 110.17, 109.43, 56.31; MS (EI): m/z 359.4 [M+1]+ (20), 268.0 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

5-(12,12a-Dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indol-12-yl)-2-ethoxyphenol (11a)

Yield: 82%; Melting range (°C): 191–193; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3133.8 (N–H str), 1687.4 (C = N str), 1441.1 (C–N str), 1207.2 (C–O–C str), 1577.2 (C = C str, aromatic), 3068.7 (C–H str, aromatic), 2975.0 (C–H str, aliphatic), 1620.1 (N–H bend), 3416.2 (O–H str); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 8.90 (s, 1H, –NH–), 7.78 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.74 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.49 (t, 1H, ArH), 7.43 (t, 2H, ArH), 7.18 (m, 3H, ArH), 7.02 (m, 2H, ArH), 6.90 (m, 3H, ArH), 6.10 (s, 1H, >CH–), 5.96 (s, 1H, –OH), 3.49 (s, 1H, >CH–), 4.14 (s, 3H, –OC2H5); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 171.76, 169.10, 147.55, 146.52, 141.21, 139.77, 138.29, 129.56, 128.21, 126.98, 125.33, 124.21, 122.87, 121.97, 117.98, 114.79, 112.05, 110.19, 109.44, 56.18, 53.17; MS (EI): m/z 373.7 [M+1]+ (15), 282.0 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

12-(p-Tolyl)-12,12a-dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indole (12a)

Yield: 72%; Melting range (°C): 197–199; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3139.2 (N–H str), 1693.9 (C = N str), 1460.4 (C–N str), 1199.6 (C–O–C str), 1460.4 (C = C str, aromatic), 3070.1 (C–H str, aromatic), 2893.5 (C–H str, aliphatic), 1606.1 (N–H bend); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 9.38 (s, 1H, –NH–), 8.21 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.82 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.68 (d, 1H, ArH), 7.53 (t, 1H, ArH), 7.57 (d, 2H, ArH), 7.28 (t, 2H, ArH), 7.19 (t, 1H, ArH), 7.12 (t, 1H, ArH), 6.94 (d, 1H, ArH), 6.86 (t, 1H, ArH), 3.49 (s, 1H, >CH–), 2.42 (s, 3H, –CH3), 2.00 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 171.08, 141.94, 140.32, 139.96, 138.02, 132.38, 131.41, 129.86, 129.28, 128.82, 127.19, 125.67, 123.11, 122.06, 121.90, 119.25, 110.55, 109.88, 21.88; MS (EI): m/z 327.7 [M+1]+ (16), 235.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

12-(3-Chlorophenyl)-12,12a-dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indole (13a)

Yield: 78%; Melting range (°C): 194–197; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3184.9 (N–H str), 1708.3 (C = N str), 1463.5 (C–N str), 1201.1 (C–O–C str), 1410.3 (C = C str, aromatic), 3078.3 (C–H str, aromatic), 1613.2 (N–H bend), 783.3 (C–Cl str); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 9.12 (s, 1H, –NH–), 8.36 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.73 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.62 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.52 (dd, 2H, ArH), 7.45 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.41 (d, 2H, ArH), 7.25 (dd, 1H, ArH), 7.05 (t, 1H, ArH), 6.89 (d, 1H, ArH), 6.86 (t, 1H, ArH), 3.49 (s, 1H, >CH–), 1.83 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 170.40, 142.18, 136.89, 135.77, 134.92, 131.68, 130.57, 130.21, 129.75, 129.65, 129.04, 127.52, 123.32, 122.24, 121.49, 119.73, 110.71, 110.12; MS (EI): m/z 347.7 [M+1]+ (9), 255.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

12-(2-Chlorophenyl)-12,12a-dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indole (14a)

Yield: 75%; Melting range (°C): 188–190; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3185.6 (N–H str), 1713.6 (C = N str), 1462.7 (C–N str), 1230.8 (C–O–C str), 1462.7 (C = C str, aromatic), 3180.6 (C–H str, aromatic), 1614.6 (N–H bend), 747.4 (C–Cl str); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 9.09 (s, 1H, –NH–), 7.87 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.73 (dd, 1H, ArH), 7.50 (dd, 1H, ArH), 7.40–7.31 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.21 (t, 2H, ArH), 6.92 (d, 2H, ArH), 6.84 (t, 1H, ArH), 3.55 (s, 1H, >CH–), 1.83 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 170.15, 142.17, 140.44, 134.67, 134.03, 133.76, 133.16, 132.67, 131.90, 131.33, 130.96, 130.24, 129.83, 129.40, 126.83, 126.39, 123.40, 122.25, 121.58, 120.27, 110.10; MS (EI): m/z 347.9 [M+1]+ (18), 255.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

12-(2-Bromophenyl)-12,12a-dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indole (15a)

Yield: 77%; Melting range (°C): 187–190; IR (KBr; νmax/cm-1): 3139.5 (N–H str), 1712.6 (C = N str), 1460.7 (C–N str), 1231.6, 1201.2, (C–O–C str), 1460.7 (C = C str, aromatic), 3076.8 (C–H str, aromatic), 1614.0 (N–H bend), 741.0 (C–Br str); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 8.84 (s, 1H, –NH–), 7.81 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.71 (d, 3H, ArH), 7.40 (t, 1H, ArH), 7.32–7.25 (m, 3H, ArH), 7.21 (t, 1H, ArH), 6.93 (d, 2H, ArH), 6.81 (t, 1H, ArH), 3.49 (s, 1H, >CH–), 1.71 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 169.98, 142.06, 140.44, 136.04, 135.68, 134.03, 133.42, 132.70, 131.04, 130.46, 129.10, 127.46, 124.41, 123.44, 122.10, 121.60, 120.26, 110.60; MS (EI): m/z 392.2 [M+1]+ (10), 301.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

12-(2-Fluorophenyl)-12,12a-dihydro-5H-benzo[2,3][1,4]oxazepino[5,6-b]indole (16a)

Yield: 72%; Melting range (°C): 190–192; IR (KBr) (νmax/cm-1): 3151.8 (N–H str), 1710.8 (C = N str), 1460.3 (C–N str), 1221.8 (C–O–C str), 1460.3 (C = C str, aromatic), 3080.5 (C–H str, aromatic), 1611.9 (N–H bend), 1094.0 (C–F str); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ (ppm) 8.12 (s, 1H, –NH–), 7.90 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.71 (t, 1H, ArH), 7.45 (q, 2H, ArH), 7.25 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.22 (m, 4H, ArH), 6.87 (t, 3H, ArH), 3.49 (s, 1H, >CH–), 1.59 (s, 1H, >CH–); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ (ppm) 169.55, 159.54, 141.84, 132.67, 131.86, 130.55, 130.44, 129.99, 129.44, 124.29, 124.26, 123.55, 123.23, 122.19, 121.79, 116.49, 116.28, 110.32; MS (EI): m/z 331.5 [M+1]+ (14), 239.9 [M – C6H4N]+ (100).

Cell culture & sulforhodamine B assay

Hep-G2 cells were grown in Roswell Park Memorial Institute media (RPMI 1640) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM l-glutamine in T-75 flask at 37°C, 5% CO2, 95% air and 100% relative humidity for 24 h. After growing, 100-μl cells containing media were inoculated into 96-well plates at a concentration of 5 × 103 cells/well. Separately, all the compounds to be tested were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide at 100 mg/ml and diluted to 1 mg/ml using water and stored frozen prior to use. Next day, 100 μl of compounds containing media was added in each well (10, 20, 40 and 80 μg/ml) and incubated at standard conditions for 48 h. To terminate the reaction, 50 μl of the cold 30% trichloroacetic acid was added and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. The supernatant was discarded; the plates were washed five-times with tap water and air dried. Furthermore, 50 μl of sulforhodamine B solution at 0.4% (w/v) in 1% acetic acid was added to each of the wells and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. After staining, the residual dye was removed by washing five-times with 1% acetic acid and the plates were air dried. The bound stain was subsequently eluted with 10 mM trizma base and the absorbance was read on a plate reader at a wavelength of 540 nm with 690-nm reference wavelength. The results were obtained in triplicate on separate plates and finally the average values were determined from these three experiments.

The percent growth inhibition was calculated using the formula [(Ti-Tz)/(C-Tz)] × 100%. The abbreviations used in formula were considered as: Time zero (Tz), control growth (C) and test growth in the presence of drug at the four concentration levels (Ti). [Citation21,Citation22].

In silico screening

The primary structures of compounds were designed with ChemDraw Ultra 12.0 and their geometry was optimized six-times with Gauss view 5.0. On the other hand, National Centre for Biotechnology Information and Protein Data Bank were used as chemical sources to get the established five homological cancer protein targets, namely IL-2 (1Z92), IL-6 (1IL6), Caspase-3 (1QX3), Caspase-8 (1IBC) and COX-2 (4COX), respectively [Citation23–25]. Active site was recognized with the help of CASTp database. Furthermore, in silico molecular docking studies of titled derivatives were performed using Autodock 4.1 along with its LGA algorithm for automated flexible ligand docking and binding energy evaluated in the form of negative kilocalorie per mole. Probable hydrogen bonds and π bonds were evaluated.

Prediction of physiochemical properties

The Med Chem Designer and QikProp were used to predict the ADME properties of the compounds for analyzing the drug likeness of all the molecules. Chemical structure was optimized via ligprop. Furthermore, ADME profiling of all these structure was calculated. In this study, we have evaluated % ABS and Lipinski's violation [Citation26].

MD simulation

The dynamic simulation was used to investigate and track the behavior of used inhibitor into active site domain of IL-6. Best molecular docking pose of ligand–protein was selected for MD simulation using Elmar Krieger MD simulation tools [Citation27]. AMBER03 force field was assigned to perform real-time MD simulation [Citation28]. The complex was solvated with HOH model (density = 0.997 g/l) into the defined 10 A0 larger simulation cell boundary and the default physiological pH 7.4 were adjusted. Furthermore, we used 0.9% NaCl (physiological solution) containing Na+ and Cl- ions concentration as a mass fraction to maintain and neutralize the simulation cell boundary. Temperature and pressure were assigned on 298 K and 1 bar, respectively. Then, the system was submitted for 3000 ps time for running the MD simulation to get snapshots (sim) trajectory. Finally, sims trajectory were analyzed and corresponding data plotted by using Sigma Plot 11.0 tools.

Results & discussion

In vitro study of anticancer activity on the Hep-G2 cell line

All the synthesized indole-fused benzooxazepines were screened against human hepatoma (Hep-G2) cancer cell lines (). Effects of the synthesized compounds (1a–16a) and the standard drug adriamycin (ADR) on human hepatoma cell line (Hep-G2 cells) are demonstrated in Supplementary Figure 1. The microscopic pictures (Supplementary Figure 2A–F) are showing the effect of treatments with the active compounds (6a, 10a, 13a, 14a and 15a) and ADR on Hep-G2 human liver cancer cell line. Although the parent compound 1a showed the moderate cytotoxic potential (GI50 = 48.3 μg/ml) against the Hep-G2 cell line; however, some of its substituted derivatives exhibited high selectivity (GI50 <10 μg/ml) toward the Hep-G2 cell line. Activity results proved that substitutions at 2, 3 and 4 positions of the phenyl ring play a crucial role in imparting the anticancer activity. The C-4 substitutions (–OH, –Cl, –Br, –OCH3 and –CH3) on phenyl ring led to compounds 2a, 4a, 5a, 8a and 12a without any significant improvement in cytotoxicity, except the compounds 6a, possessing more electronegative group (F), exhibited better cytotoxicity (GI50 <10 μg/ml). Similarly, the C-3 substitutions with Cl on phenyl ring led to compound 13a with better cytotoxicity profile (GI50 <10 μg/ml). In addition, the C-2 substitutions with Cl and Br on phenyl ring led to compounds 14a and 15a with significant improvement in cytotoxicity (GI50 < 10 μg/ml), whereas the C-2 substitutions with more electronegative group (F) led to compound 16a with slightly reduced cytotoxicity profile (GI50 = 10.7). In general, it may be concluded that the halogenations of phenyl ring were more beneficial for the anticancer activity when compared with the parent compound 1a. In conjugation with this, the introduction of methoxy group at C-3 and C-4 position led to compounds 8a and 9a with slightly improved activity (GI50 = 15.8 and 36.7), whereas 3,4,5-trimethoxy substitution led to compound 7a with slightly decreased anticancer activity (GI50 = 52.6). The hydroxylation or methylation of phenyl ring (compounds: 2a, 3a and 12a) is detrimental for the cytotoxic activity. However, while retaining the important methoxy substitution at C-4 position, hydroxylation at C-3 position led to compound 10a with an appreciable improvement in cytotoxic potential (GI50 <10 μg/ml), whereas alteration of methoxy group with ethoxy group (compound 11a) again lost the cytotoxic potential. Interestingly, the growth curve of in vitro data suggested that, at 10 μg/ml concentrations of active compounds, the % control growths are 50% or below 50%, but they do not fall in the negative value of % control growth. Thus, for the future, it might be expected that all the active compounds of the series will kill the cancerous cell while minimizing the normal cell death.

In silico study of anticancer activity

In silico molecular docking was performed using five established liver cancer targets, namely IL-2, IL6, COX-2, Caspase-3 and Caspase-8 via Autodoc 4.1 along with LGA algorithm parameter for automated flexible ligand docking. Docking images for the active compounds 6a, 10a, 13a, 14a and 15a with the related targets IL-2, IL-6, COX-2, Caspase-3 and Caspase-8 are illustrated in Supplementary Figure 3 that indicate the amino acids interaction with the ligands, H- and π-bonds and their bond lengths. The binding affinity (kcal/mol), number of H- and π-bonds, and amino acids interaction for only active compounds are shown in , whereas the binding affinity and (kcal/mol) and amino acids interactions for all the synthesized compounds are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The molecular docking studies of all the compounds had shown the good binding affinity with the selected targets. Predominantly, compounds 6a, 10a, 13a, 14a and 15a exhibited potent affinity with selected molecular targets having interaction energies ranges from -6.6 to -10.9 kcal/mol with various molecular targets. Compound 6a displayed the good binding affinity with the COX-2 (-10.5 kcal/mol and 15 π-bonds), IL-2 (-8.7 kcal/mol, 2H and five π-bonds), IL-6 (-8.3 kcal/mol and nine π-bonds), Caspase-3 (-7.1 kcal/mol, 1H and four π-bonds) and Caspase-8 (-7.0 kcal/mol, 1H and seven π-bonds). A similar fashion was observed for the compounds 13a and 14a; however, compound 10a manifested somewhat less affinity toward Caspase-3 (-6.8 kcal/mol and four π-bonds) and Caspase-8 (-6.7 kcal/mol, 2H and eight π-bonds), whereas compound 15a exhibited less affinity toward Caspase-3 (-6.6 kcal/mol, 1H and eight π-bonds). Although all of the active synthesized compounds have moderate-to-excellent binding affinities toward IL-2, IL6, COX-2, Caspase-3 and Caspase-8, the binding energies on COX-2 receptor site are predominantly high (9.1–10.9 kcal/mol). From this, it might be predicted that the promising cytotoxic potential of these active compounds, which was confirmed by the in vitro anticancer activity on human HCC Hep-G2 cell line, might be better mediated through COX-2-dependent mechanism ( & ).

Prediction of ADME properties

A computational study was performed via QikProp tools to predict the physiochemical properties of the compounds 1a–16a. The ranges of the calculated property of the molecules with average value are shown in . Herein, we also predicted the percentage of absorption (% ABS), rotatable bonds (n-ROTB), number of hydrogen bond donors (n-OHNH), number of hydrogen bond acceptors (n-OH), predicted octanol/water partition coefficient (QPlogPo/w) and Lipinski's violation. It was investigated that the synthesized compounds showed the % ABS ranging from 85 to 100%. Moreover, all of the synthesized compounds followed the violated Lipinski's parameters. Other parameter such as QPlogPo/w predicts octanol/water partition coefficient, which was found within the accepted range of -2.0 to 6.5.

MD simulation

MD simulation of compound 14a was performed with IL-6. This ligand displayed the good binding affinity, H-bond and contraction with back bone structure of IL-6. So, we decided to study the influences of compound 14a into the active site domain of IL-6 on the structure protein. Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), potential energy and binding energy of the IL-6 with compound 14a containing complex were calculated by MD trajectory frames. The RMSD, potential energy and binding energy are profiled in . Through the graphic profile, we observed the structural stability of backbone structure throughout the MD simulation. No more fluctuation was observed into the RMSD after the time (100 ps), which indicates the stability of back bone structure with ligand near the 1000 ps time in MD simulation. Potential energy and binding energy of complex were calculated with time, which indicated that the potential energy (kJ/mol) do not show more fluctuation after 100 ps time, whereas average complex binding energy was observed near -1.6 kg/mol. The fluctuation into the residue of back bone structure is shown in .

Finally, we performed these calculations of data, where we found the structural stability of compound 14a along with IL-6 into active site domain.

Conclusion

We have synthesized a series of novel indole-fused benzooxazepines that displayed a potent cytotoxicity against the Hep-G2 cell line for the treatment of HCC. While considering all the newly synthesized compounds together, it may be concluded that the fusion of indole-fused benzooxazapines with substituted phenyl ring as a hydrophobic side chain establishes an important pharmacophoric structure and the positions 2, 3 and 4 of the phenyl side chain are the key reactive sites that could be altered with different groups to elicit valuable anticancer profiles. More precisely, the substitutions with more electronegative halogen atoms at phenyl ring directly attached to the indole-fused benzooxazepine led to compounds 6a and 13a–15a, eliciting enhanced cytotoxic potential with GI50 < 10 μg/ml, which was also supported by molecular docking study. In addition, 3-hydroxy-4-methoxy phenyl-substituted indole-used benzooxazepine led to compound 10a, which also exhibited enhanced cytotoxic potential with GI50 < 10 μg/ml. Computation study demonstrated good oral absorption and human albumin protein binding. Hence, these titled compounds might be stable in the pharmaceutical dosage form. Moreover, the titled compounds contain a novel pharmacophore incorporating indole-fused benzooxazepine that have never been synthesized prior to this study to our knowledge; so, the present scaffold may emerge as an anticancer lead for the future.

The in vivo anticancer studies of potent compounds in the series, studies to improve anticancer activity and toxicity profiling of indole-fused benzooxazepines are in progress.

Future perspective

Cancer is still a big challenge for researchers and there is an immense need for exploration and development of novel lead compounds. Ergo, there is a desideratum for more potent, less toxic and less expensive anticancer drugs. To accomplish this goal, indole, azepine and six-membered flexible rings are getting much attention for cancer therapy. The synthesized indole-fused benzooxazepines attached with six-membered flexible ring might be counted as primary lead molecules for future modification and optimization, to afford potential anticancer drugs. Interestingly, from the growth curve of in vitro data, it might be expected in the future that all the active compounds of series will kill the cancerous cell while minimizing the normal cell death. In addition, a feasible one-pot-efficient synthetic approach for the proposed derivatives will make it cost effective. Lastly, these newly synthesized lead compounds need to go through further in vivo anticancer activity and toxicity profiling for better clarification of suitability of titled compounds for the treatment of various types of cancer.

Table 1. In vitro cytotoxicity data of synthesized compounds against human hepatoma (Hep-G2) cancer cell lines.

Table 2. Docking affinity of active compounds with assigned anticancer receptors.

Table 3. Pharmacokinetic parameters important for oral bioavailability and protein-binding parameters of synthesized compounds.

Indole and seven-membered azepine rings have been individually reported for their potential benefits in the prevention of different cancers.

Indole-fused benzooxazepines incorporated with a flexible substituted phenyl ring were synthesized by one-pot three-component approach as new pharmacophoric lead compounds for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma.

In vitro study on the Hep-G2 cell line showed that substitutions with more electronegative groups at phenyl ring directly attached with indole-fused benzooxazepine generally elicited enhanced cytotoxic potential.

Molecular docking on related targets including IL-2, IL-6, COX-2, Caspase-3 and Caspase-8 receptor site supported the in vitro study on the Hep-G2 cell line; ADMET profiling showed the better oral absorption; and MD simulation study showed the good structural stability of compound 14a along with IL-6 into active site domain.

Author contributions

AK Singh performed the design and synthesis of compounds, spectral characterization of compounds, in vitro anticancer screening, computational study, data interpretation and writing of the manuscript. V Raj and A Rai participated in the computational study. AK Keshari participated in the synthesis of compounds. S Saha participated in the design of research protocols, supervised every step of the work and reviewed the whole manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Supplementary Material For: Supplementary Data

Download MS Word (983 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere thanks to CDRI, Lucknow, and USIC BBAU, Lucknow, for providing the spectral data. The authors acknowledge the support and facilities received from Advanced Centre for Treatment, Research and Education in Cancer (ACTREC), Navi Mumbai, India, for undertaking anticancer screening.

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.future-science/doi/full/10.2217/fsoa-2016-0079

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Sunil D, Isloor AM, Shetty P, Satyamoorthy K, Prasad ASB. 6-[3-(4-Fluorophenyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]-3-[(2-naphthyloxy)methyl][1,2,4]triazolo[3,4-b][1,3,4]-thiadiazole as a potent antioxidant and an anticancer agent induces growth inhibition followed by apoptosis in HepG2 cells. Arabian J. Chem. 3, 211–217 (2010).

- Rajanarendar E, Reddy MN, Krishna SR, Reddy KG, Reddy YN, Rajam MV. Design, synthesis, in vitro antimicrobial and anticancer activity of novel methylenebis-isoxazolo[4,5-b]azepines derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 50, 344–349 (2012).

- Raffa D, Maggio B, Raimondi MV et al. Recent advanced in bioactive systems containing pyrazole fused with a five membered heterocycle. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 97, 732–746 (2014).

- Pettit GR, Knight JC, Herald DL et al. Isolation of labradorins 1 and 2 from Pseudomonas syringae pv. Coronafaciens. J. Nat. Prod. 65, 1793–1797 (2002).

- Radwan MAA, El-Sherbiny M. Synthesis and antitumor activity of indolylpyrimidines: marine natural product meridianin D analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 15, 1206–1211 (2007).

- Nagle A, Hur W, Gray NS. Antimitotic agents of natural origin. Curr. Drug Targets 7, 305–326 (2006).

- Crielaard BJ, Wal SVD, Lammers T et al. A polymeric colchicinoid prodrug with reduced toxicity and improved efficacy for vascular disruption in cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomedicine 6, 2697–2703 (2011).

- Nedolya NA, Tarasova OA, Volostnykh OG, Albanov AI, Trofimov BA. Simultaneous synthesis of 4,5-dihydro-3H-azepines and 3H-azepines, bearing alkoxy and alkylsulfanyl substituents, through metallation of 2-aza-1,3,5-trienes by t-BuOK. J. Organomet. Chem. 696, 3359–3368 (2011).

- Maginn EN, Browne PV, Hayden P et al. PBOX-15, a novel microtubule targeting agent, induces apoptosis, upregulates death receptors, and potentiates TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells. Br. J. Cancer 104, 281–289 (2011).

- Belal A. Design, synthesis and anticancer activity evaluation of some novel pyrrolo[1,2-a]azepine derivatives. Arch. Pharm. 347, 515–522 (2014).

- Jiang JH, Zheng CH, Wang CQ et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 5,6,7-trimethoxy-1-benzylidene-3,4-dihydro-naphthalen-2-one as tubulin-polymerization inhibitors. Chin. Chem. Lett. 26, 607–609 (2015).

- Rajak H, Dewangan PK, Patel V et al. Design of combretastatin A-4 analogs as tubulin targeted vascular disrupting agent with special emphasis on their cis-restricted isomers. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 1923–1955 (2013).

- Nagaiah G, Remick SC. Combretastatin A4 phosphate: a novel vascular disrupting agent. Future Oncol. 6, 1219–1228 (2010).

- Curini M, Epifano F, Marcotullio MC, Rosati O. Ytterbium triflate promoted synthesis of 1,5-benzodiazepine derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 42, 3193–3195 (2001).

- Varala R, Enugala R, Adapa SR. Zinc montmorillonite as a reusable heterogeneous catalyst for the synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-1H-1,5-benzodiazepine derivatives. ARKIVOC 13, 171–177 (2006).

- Nardi M, Cozza A, Maiuolo L, Oliverio M, Procopio A. 1,5-Benzoheteroazepines through eco-friendly general condensation reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 52, 4827–4834 (2011).

- Nardi M, Cozza A, Nino AD, Oliverio M, Procopio A. One-pot synthesis of dibenzo[b,e][1,4]diazepin-1-ones. Synthesis 5, 800–804 (2012).

- Biginelli P. Synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones. Gazz. Chem. Ital. 23, 360–372 (1893).

- Kappe CO. 100 Years of the Biginelli dihydropyridine synthesis. Tetrahedron 49, 6937–6963 (1993).

- Youssef MM, Amin MA. Microwave assisted synthesis of some new thiazolopyrimidine, thiazolodipyrimidine and thiazolopyrimidothiazolopyrimidine derivatives with potential antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. Molecules 17, 9652–9667 (2012).

- Vanicha V, Kanyawim K. Sulforhodamine B colorimetric assay for cytotoxicity screening. Nat. Protocols 1, 1112–1116 (2006).

- Skehn P, Storeng R, Scudiero A et al. New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer drug screening. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 82, 1107 (1990).

- De Boer EC, De Jong WH, Steerenberg PA et al. Induction of urinary interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-2, IL-6, and tumour necrosis factor during intravesical immunotherapy with bacillus Calmette-Guérin in superficial bladder cancer. Cancer Immunolo. Immunother. 34, 306–312 (1992).

- Du J, Yang H, Zhang D et al. Structural basis for the blockage of IL-2 signaling by therapeutic antibody basiliximab. J. Immunol. 184, 1361–1368 (2010).

- Romanowski MJ, Scheer JM, O'Brien T, McDowell RS. Crystal structures of a ligand-free and malonate-bound human caspase-1: implications for the mechanism of substrate binding. Structure 12, 1361–1371 (2004).

- Lagorce D, Sperandio O, Galons H, Miteva MA, Villoutreix BO. FAF-drugs2: free ADME/tox filtering tool to assist drug discovery and chemical biology projects. BMC Bioinformatics 9, doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-396 (2008).

- Krieger E, Darden T, Nabuurs SB, Finkelstein A, Vriend G. Making optimal use of empirical energy functions: force-field parameterization in crystal space. Proteins 57, 678–683 (2004).

- Best RB, Buchete NV, Hummer G. Are current molecular dyanamics force fields too helial? Biophys. J. 95, L07–L09 (2008).