Abstract

Grade 4 unclassified renal cell carcinoma, with a sarcomatoid component (URCCSC) is a rare high grade tumor presumptively derived from all histological subtypes of renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Even though rare, URCCSC generates a great deal of interest, as it is a particularly aggressive variant of RCC, that is poorly responsive to chemo-immunotherapy. Whether it originates from a separate sarcomatoid cell clone within the tumor or from true cell dedifferentiation from RCC has yet to be established. The diagnosis of URCCSC is usually based on morphological and immunohistochemical characteristics of the neoplastic cells which show transitional epithelial/mesenchymal features. In fact, the frequent loss of epithelial markers and gain of mesenchymal phenotypes, can result in difficulties in interpreting diagnostic data. Consequently assigning the optimal therapeutic treatments can be hindered due to this biological “complexity." Here we present the clinicopathological records of a 51 year-old patient who underwent an excision of a periureteral retroperitoneal mass, and whose first pathological diagnosis was malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST). Eleven months after surgery, a CT-scan revealed a local recurrence of the disease. Later on the patient was admitted to our hospital and a systemic, sarcoma-oriented, treatment was initiated. A partial remission was observed but only with a dacarbazine based regimen administered as a third line therapy, after which a second surgery took place. The removed tumor was diagnosed as URCCSC based on the peculiar morphologic and immunohistochemical characteristics of the cells. Pathological assessment of the first intervention was re-evaluated, resulting in a diagnosis of URCCSC. This case-report therefore highlights the implications that an erroneous pathologic diagnosis can have for the clinical management of this disease. Furthermore, the unexpected response to a dacarbazine based regimen, indicates that this drug should be included among the therapeutic options available against this type of renal carcinoma.

Abbreviations

| RCC | = | renal cell carcinoma |

| SRCC | = | sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma |

| URCCSC | = | unclassified renal cell carcinoma with a sarcomatoid component |

| ISUP | = | international society of urology pathology |

| NSE | = | neuron specific enolase |

| EMA | = | epithelial membrane antigen |

| SMA | = | smooth muscle actin |

| GFAP | = | glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| NF neurofilament | = | |

| MPNST | = | malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor |

| IORT | = | intraoperative radiation therapy |

| CT | = | computed tomosarcomatoid component |

| EMT | = | epithelial mesenchymal transition |

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is currently the most common form of kidney cancer. In 2006 it was responsible for the fatalities of 102,000 people, accounting for 2–3% of all malignant diseases in adults worldwide.Citation1 However, unlike other malignancies, such as colorectal cancer in which adenocarcinomas account for 98% of histotypes,Citation2 RCC is not one single entity, but rather a group of malignancies that arise from cells of various parts of nephrons. In addition, each group, or sub-type of RCC may be prone to sarcomatoid differentiation. This sarcomatoid transition can occur when RCC cells develop a spindle-cell like and/or pleomorphic appearance, increasing their mesenchymal differentiation and losing their epithelial features. In such instances these types of RCC are referred to sarcomatoid renal cell carcinomas (SRCCs).Citation3

Microscopically, these tumors may be pure sarcomatoid carcinomas without recognizable epithelial elements, or more often, biphasic, with both carcinomatous and sarcomatoid components, with the latter being seen, in some series, between 1% to 8% of RCCs.Citation4-Citation6

The associated RCC may be of clear cell type, chromophobe, papillary, collecting duct, mucinous tubular, spindle cell, acquired cystic disease–associated, and unclassified carcinomas.Citation7

In 2004, Cheville et al.Citation3 observed that sarcomatoid differentiation occurs more commonly in chromophobe RCC (8.7%), compared to clear cell RCC (5.2%) and papillary cell RCC (1.9%) respectively.

The sarcomatoid elements are most often composed of fascicles of malignant spindle cells, pleomorphic undifferentiated cells, or of an unclassified morphology with or without heterologous differentiation along the lines of chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, or rhabdomyosarcoma.

The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus conference stated that a pure sarcomatoid pattern, reported in 4% of all sarcomatoid carcinomas should be diagnosed as grade 4 unclassified renal cell carcinoma with a sarcomatoid component URCCSC.Citation8

Although the specific molecular mechanisms responsible for the sarcomatoid transformation of a renal tumor are unclear, it seems likely that both clear cell and sarcomatoid components of RCC derive from the same progenitor cell.Citation6 Furthermore, because sarcomatoid changes can develop in all types of RCC, and there is, hitherto, no evidence that RCC develops de novo as a sarcomatoid carcinoma, the 2004 WHO classification does not consider it an entity per se, but rather as a progression of RCC.Citation9

Even though rare, SRCCs generate a great deal of interest as it is a particularly aggressive variant of RCC that is poorly responsive to chemo-immunotherapy. Therefore, the purpose of this report is to describe the clinical, histological and immunohistochemical features of a case of URCCSC, highlighting the implications that an erroneous pathologic diagnosis can have for the clinical management of this disease and supporting a possible therapeutic role for S-100 protein tumor immunoexpression in URCCSCs.

Clinical Case

In October 2008 a 51 year-old patient underwent, at the reference hospital, an excision of a periureteral retroperitoneal mass measuring 20 mm. The pathological report indicated that the margins of resection were free of neoplastic infiltration and subsequent microscopic examination revealed a neoplasm composed of medium to large sized cells. The cells were described as solid and cord aggregates with nuclear pleomorphism, containing spindle profiles and variable cytoplasmic rims. In addition, cellular necrosis, severe cyto-nuclear atypia and high mitotic index (MIB-1: 70%) was also present. The immunohistochemical analyses showed that the cells were positive for S-100 protein, Neuron Specific Enolase (NSE), and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and negative for smooth muscle actin (SMA), desmin, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), CD34, chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD57, Neurofilament (NF). While, wide spectrum cytokeratin (CK MNF116) was reported as negative. Based on these findings a Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor (MPNST) was diagnosed.

In December 2008, in another hospital, the patient underwent an evaluation to determine whether a radical nephroureterectomy with complementary treatment via intraoperative radiation treatment (IORT) and/or brachytherapy was suitable. However, since a computed tomography (CT) scan was negative and the pathological re-evaluation was in agreement with the previous diagnosis a decision was made in favor of a strict follow up. However, the CT scan of the chest and abdomen, performed later in July 2009, revealed a round lesion measuring 25 mm into the fourth hepatic segment alongside 2 heterogenous hyperdense solid formations, measuring 20 mm into the perirenal seat in contiguity with the pelvis. Solid tissue surrounded the proximal and middle homolateral ureter causing mild hydronephrosis, and an increase in para-aortic sub-renal lymph node size was also observed.

In September 2009 the patient referred to our center and, according to the previous diagnosis of MPNST, received systemic treatment with liposomal doxorubicin (Myocet®) in a regimen of 50 mg/m2 on day 1 every 3 weeks combined with ifosfamide 3000 mg/m2 on day 1–3 as part of our institutional protocol. After 2 cycles of this treatment, a CT scan was performed and showed that the lesions were stable, according to the RECIST criteria. However, after the fourth cycle of this treatment, an increase in the size of lomboaortic and renal adenopathies was observed together with a rapid progression of hepatic metastases. Therefore, a 7000 mg/m2 weekly pump infusion of ifosfamide was initiated for 3 cycles, until a further progression of hepatic and lymph node disease was observed.

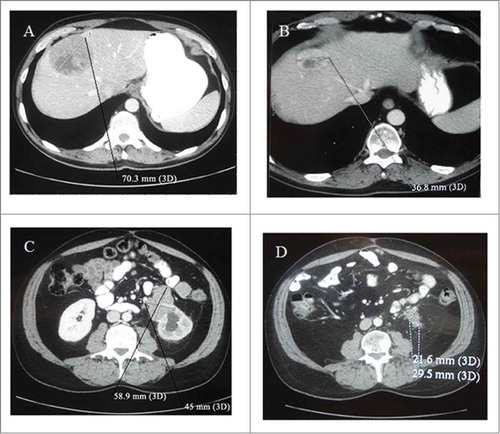

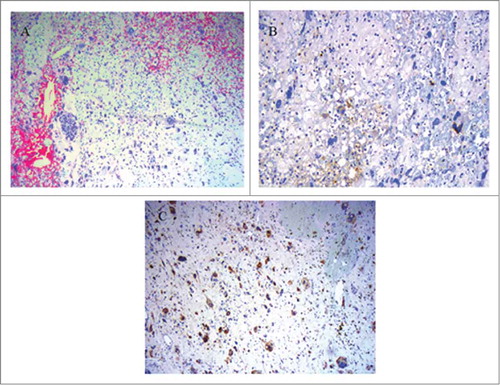

In March 2010, despite the clinical worsening of the patient, a further line of treatment with epirubicin, at 30 mg/m2 on day 1–3 combined with dacarbazine 300 mg/m2 on day 1–3 every 3 weeks, was administered. After the third cycle of this treatment, a significant reduction in both the hepatic and node lesions were observed (). Overall, the patient received 7 cycles of chemotherapy and subsequently underwent radical left nephrectomy, with the removal of 2 pararenal lesions and hepatic metastasectomy followed by IORT on the local relapse. Microscopically the excised tumor was composed of small and giant, multinucleated, anaplastic, bizarre, spindle and pleomorphic cells, with scattered areas of hemorrhage and coagulative cell necrosis throughout the tumor. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells exhibited S-100 protein positivity and a focal expression of pancytokeratins (panCK (AE1, AE3, PCK26 clone) (). These observations allowed us to propose a diagnosis of URCCSC, pT3aNx (0) G4.

Figure 1. CT scan of the abdomen performed before the start of epirubicin plus dacarbazine treatment and 6 months later. The hepatic and adenopathic lesions regressed from 70.3 mm (A) to 36.8 mm (B) and from 58.9 × 45 mm (C) to 21.6 × 29.5 mm respectively (D).

Figure 2. Microscopic features of the grade 4 unclassified renal cell carcinoma, with sarcomatoid component (URCCSC). (A) Patternless arrangement of tumor cells with pleomorphic and spindle cell morphology (H&E x10). (B) Focal immunopositivity for Keratins of neoplastic cells, showing epithelial differentiation. panCK (AE1, AE3,PCK26 clone) (H&E x 25). (C) Immunopositivity for S-100 of neoplastic cells. S-100 clone (H&E × 25).

The review of original pathological slides of the first intervention confirmed the diagnosis of URCCSC.

In May 2011 a CT scan showed the appearance of liver metastasis, and an area of osteo-rarefaction in the iliac bone, close to the anterior superior iliac spine had taken place. Consequently, the patient received a first line metastatic treatment for RCC with sunitinib in a regimen of 50 mg/day for 4 weeks on treatment and 2 weeks off (schedule 4/2). The treatment was discontinued in January 2012 because the patient was found to have a lung micronodule and bone progression. In February 2012 dacarbazine 300 mg/m2 on day 1–3 every 3 weeks was again administered and a CT scan performed 3 months later demonstrated the complete resolution of the lung lesion, a reduction of the hepatic lesion and a stabilization of the osteo-rarefaction of the iliac bone.

Discussion

A number of hypotheses have been proposed to explain the cellular composition of SRCC. It was first suggested that the sarcomatoid component (SC) of the RCC might derive from the metaplastic transformation of the carcinoma.4 More recently, Conant et al.Citation10 showed that the mesenchymal cells in the SC undergo morphological modifications from their epithelial origin via epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT). These morphological changes result in the higher proliferative and metastatic activity of SRCC compared to ordinary RCC.Citation11 Furthermore, another explanation postulates that the atypical spindle cells may represent a bizarre pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic reaction in the stroma surrounding the invasive areas of RCC.Citation12 As a result, cyto-morphology alone may not be sufficient for diagnostic purposes, since the dedifferentiated sarcomatoid elements, especially in pure URCCSC, may simulate a variety of benign or malignant tumors.Citation13 Consequently, immunohistochemistry, aimed at accurately typing neoplastic cells, must effectively integrate cyto-morphological studies in order to formulate a correct diagnosis.

The majority of URCCSCs observed are negative, actin and desmin markers; whereas they stain positive for vimentin and sometimes cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) and EMA.Citation14 In general, cytokeratins, in sarcomatous carcinomas, are predominantly negative with only rare, weakly, positive cells noted among anaplastic malignant cells.Citation1 Interestingly, both pure and biphasic SRCCs are usually S-100 protein negative, according to DeLong et al.Citation5 who reported that among 23 cases of SRCC, only one case showed focal staining for S-100 protein in a focus of chondroid metaplasia. Although more recently, Gadre et al.Citation13 listed a diffuse positive staining of the neoplastic cells for the S-100 protein in a renal tumor predominantly composed of SC. This observation reflects the results obtained in our own case, where we also found that the primary and the relapse tumors expressed the S-100 protein and concomitantly stained positive for EMA and focally for cytokeratins. Considering that the S-100 protein is generally positive in melanoma cells but is rarely seen in SRCC, we can speculate that the presence of S-100 protein in SRCC, may potentially be used as a possible marker to predict a positive response to dacarbazine a drug mainly used in the treatment of melanomas and in some histotypes of sarcoma. However, further exploration will be needed to establish the clinical relevance of the expression of S-100 protein in this rare histologic subtype of RCC.

In 2002 Escudier et al.Citation15 carried out a Phase II trial of doxorubicin in combination with Ifosfamide in patients with metastatic SRCC. They obtained no objective responses in 23 patients, with a median time to progression of only 2.2 months. In light of this trial it was perhaps not surprising that the observed progression of the disease to ifosfamide and liposomal doxorubicin treatment and to the weekly ifosfamide infusion, arose. Conversely, it was surprising to observe the patient's partial response to a combination of epirubicin and dacarbazine or dacarbazine only treatments. A response that might be due to changes in the tumor phenotype making the neoplastic cells more sensitive to the chemotherapy. However, the percentage of SC may also have influenced the response of the cells to the drug. Unfortunately, the activity of dacarbazine in the treatment of SRCC has been rarely investigated and the studies on the use of this drug are few and dated.Citation16,17

The results obtained in the present case report indicate that the expression of S-100 protein, in URCCSCs, is a promising observation that may have positive therapeutic implications. Accordingly, dacarbazine based regimens, as a potential effective first line treatment in metastatic SRCC, may be considered in patients with S-100 protein expressing renal tumors. However, it should be noted that despite the interesting observations reported herein, this work represents just one case report. Therefore further validation in context of a clinical trial is required before a dacarbazine regimen can be recommended as a first line treatment.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- Gupta K, Miller JD, Li JZ, Russell MW, Charbonneau C. Epidemiologic and socioeconomic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): A literature review. Cancer Treat Rev 2008; 34:193-205; PMID:18313224; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.12.001

- Centre M, Jemal A, Smith R, Ward E. Worldwide variations in colorectal cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2009; 59:366-78; PMID:19897840; http://dx.doi.org/10.3322/caac.20038

- Cheville JC, Lohse CM, Zincke H, Weaver AL, Leibovich BC, Frank I, et al. Sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: An examination of underlying histologic subtype and an analysis of associations with patient outcome. Am J Surg Pathol 2004; 28:435-41; PMID:15087662; http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000478-200404000-00002

- Farrow GM, Harrison EG Jr, Utz DC. Sarcomas and mixed malignant tumors of the kidney in adults. Part III. Cancer 1968; 22: 556-63; PMID:4299778; http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(196809)22:3<556::AID-CNCR2820220310I>3.0.CO;2-N

- DeLong W, Grignon DJ, Eberwein P, Shum DT, Wyatt JK. Sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma. An immunohistochemical study of 18 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1993; 117:636-40. 5; PMID:7684893

- de Peralta-Venturina M, Moch H, Amin M, Tamboli P, Hailemariam S, Mihatsch M, et al. Sarcomatoid differentiation in renal cell carcinoma: A study of 101 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; 25:275-84; PMID:11224597; http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000478-200103000-00001

- Delahunt B, Cheville JC, Martignoni G, Humphrey PA, Magi-Galluzzi C, McKenney J, et al. The international society of urological pathology (ISUP) grading system for renal cell carcinoma and other prognostic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37:1490-504; PMID:24025520; http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299f0fb

- Cheville JC, Lohse CM, Zincke H, Weaver AL, Blute ML. Comparisons of outcomes and prognostic feature among histological subtypes of renal cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2003; 27:612-24; PMID:12717246; http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000478-200305000-00005

- Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA, eds: World Health Organization Classification of Tumors: Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2004

- Conant JL, Peng Z, Evans MF, Naud S, Cooper K. Sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma is an example of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Pathol 2011; 64:1088-92; PMID:22003062; http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200216

- Guarino M, Rubino B, Ballabio G. The role of ephitelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer pathology. Pathology 2007; 39:305-18; PMID:17558857; http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00313020701329914

- Tanas MR, Sthapanachai C, Nonaka D, Melamed J, Oliveira AM, Erickson-Johnson MR, et al. Pseudosarcomatous fibroblasticmyofibroblastic proliferation in perinephric adipose tissue adjacent to renal cell carcinoma: a lesion mimicking well-differentiated liposarcoma. Mod Pathol 2009; 22:1196-200; PMID:19525929; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.84

- Gadre SA, Math SK, Elfeel KA, Farghaly H. Cytology of a sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma with unusual coexpression of S-100 protein: a case report, review of the literature and cytologic-histologic correlation. Diagn Cytopathol 2008; 37:195-8; http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/dc.21003

- Kuroda N, Toi M, Hiroi M, Shuin T, Enzan H. Review of sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma with focus on clinical and pathobiological aspects. Histol Histopathol 2003; 18:551-5; PMID:12647806

- Escudier B, Droz JP, Rolland F, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Gravis G, Beuzeboc P, et al. Doxorubicin and ifosfamide in patients with metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: A phase II study of the Genitourinary Group of the French Federation of Cancer Centers. J Urol 2002; 168:959-61; PMID:12187199; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64551-X

- Yap BS, Baker LH, Sinkovics JG, Rivkin SE, Bottomley R, Thigpen T, et al. Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, adriamycin, and DTIC (CYVADIC) combinationchemotherapy for the treatment of advanced sarcomas. Cancer Treat Rep 1980; 64:93-8; PMID:7379060

- Lupera H, Theodore C, Ghosn M, Court BH, Wibault P, Droz JP. Phase II trial of combination chemotherapy with dacarbazine, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, doxorubicin, and vindesine (DECAV) in advanced renal cell cancer. Urology 1989; 34:281-3; PMID:2815451; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0090-4295(89)90326-9