Abstract

Metastatic melanoma is frequently fatal. Optimal treatment regimens require both rapid and durable disease control, likely best achieved by combining targeted agents with immunotherapeutics. In order to accomplish this, a detailed understanding of the immune consequences of the kinase inhibitors used to treat melanoma is required.

Following the identification of oncogenic driver mutations in the BRAF kinase in cutaneous melanoma, BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi), such as vemurafenib and dabrafenib, are now standard-of-care treatments for patients with metastatic melanoma bearing V600 BRAF mutations. The durability of clinical benefit is often short-lived, however, with BRAFi resistance developing within a median of 6 to 7 months after treatment initiation (reviewed in)Citation1 often due to MAPK pathway reactivation or P13K pathway activation. Recent efforts to extend the durability of BRAFi and to reduce side-effects due to paradoxical pathway activation in cells harbouring RAS mutations have focused on combining BRAFi with MEK inhibitors (MEKi), such as trametinib.Citation2

Several reports have demonstrated that BRAF inhibition can be pro-immunogenic, with increasing expression of melanoma differentiation antigens and some Cancer Testis antigens in BRAF V600-mutated melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo following BRAFi exposure. Furthermore, treatment of patients with BRAFi is associated with infiltration of the tumor by T lymphocytes, increased markers of T-lymphocyte cellular cytotoxicity, and decreased expression of immunosuppressive cytokines, correlating with response to therapy (reviewed in).Citation3 Together with the recent clinical successes using antibodies that target the molecular immune checkpoints CTLA4 and PD-1, the combination of kinase inhibition with immunotherapy is now being pursued for the treatment of melanoma (reviewed in).Citation4 However, the degree to which kinase inhibition may directly affect immune function remains poorly defined.

In our recent study we examined the effect of BRAFi (dabrafenib), alone or in combination with a MEKi (trametinib), on isolated immune cell populations including lymphocytes and monocyte derived dendritic cells (moDC) in vitro. We found that dabrafenib had no detectable impact on isolated CD4+ or CD8+ T-lymphocyte function and phenotype, or on moDCs, while trametinib, alone or in combination with dabrafenib, modulated immune cell function.Citation5

While our results with dabrafenib were similar to the reported effects of vemurafenib on T lymphocytes, the BRAFi BMS908662, has been shown to enhance T-cell proliferationCitation6 (and reviewed in).Citation3 Furthermore, a recent retrospective analysis of peripheral lymphocytes reported that vemurafenib, but not dabrafenib, -treated patients had decreased peripheral lymphocyte counts and altered CD4+ T-lymphocyte phenotype and function, as compared with baseline samples.Citation7 Taken together, these finding highlight the need for further comparative studies to decide which BRAFi should best be combined with immunotherapy.

Unlike BRAFi, MEK1/2 inhibitors, including U0126 and PD0325901 block ERK phosphorylation regardless of BRAF mutational status and have previously been shown to reduce T-lymphocyte viability, proliferation, IFNγ production and cytokine secretion in vitro (). We therefore sought to determine the effect of trametinib on isolated T-lymphocytes and moDCs. While dabrafenib did not impair healthy T-lymphocyte function, trametinib, alone or in combination with dabrafenib, reduced viability, proliferation, IFNγ production and cytokine secretion in our in vitro experiments on isolated cells. In addition, the activation of antigen-specific CD8+ T-lymphocytes was inhibited.

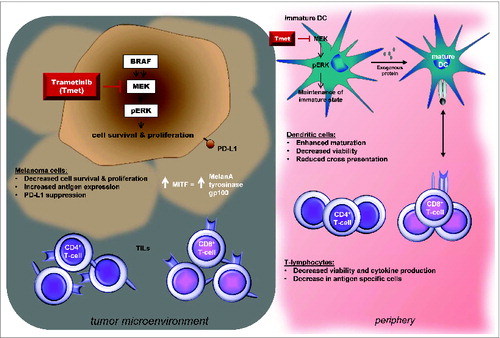

Figure 1. Proposed consequences of MEK inhibition on tumor and immune cell populations. MEK inhibition (MEKi) increases expression of the melanoma differentiation marker MDA on melanoma cells, suppresses PD-L1 expression in vitro and can reverse the decrease in MDA and CD8+ T-cell infiltrate seen in patient tumors at the time of progression while on BRAFi. MEKi also modulates T-lymphocyte and monocyte-derived dendritic cell (moDC) function in vitro. MEKi reduces T-lymphocyte viability and proliferation and IFNγ production and cytokine secretion. Trametinib also inhibits the activation of antigen-specific T-cells, cross presentation of tumor antigens and TNFα and IL-6 production. MEKi promotes maturation of moDCs in the presence of LPS or TNFα in vitro. Further studies in vivo will be required to evaluate the potential clinical impact of these in vitro findings.

ERK signaling helps maintain dendritic cells (DCs) in an immature state, and MEK inhibition has previously been shown to promote maturation of moDCs induced by agents such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or tumor necrosis α (TNFα). Similarly, we found that inhibition of ERK phosphorylation with trametinib promoted the maturation of moDCs in the presence of LPS. If matured in the presence of trametinib, alone or in combination with dabrafenib, moDCs lost their ability to cross-present the tumor antigen NY-ESO-1 in vitro.Citation5

Taken together, our findings showed that the combination of trametinib with dabrafenib can reduce the proliferation and function of isolated human T lymphocytes and modulate moDC cross-presentation (), indicating that the immune enhancing effects of BRAF inhibition can be countered by MEK inhibition in vitro. Despite this, there was no difference in the frequency of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) between patients receiving BRAFi alone or BRAFi plus MEKi, although TIL functionality was not assessed.Citation8 It has been suggested that MEKi may affect naïve T lymphocytes more than memory T cells.Citation8 Moreover, in an in vitro study by Jiang et al, MEK inhibition suppressed PD-L1 expression making melanoma cells more susceptible to immune destruction.Citation9 Thus, combining MEKi with blockade of the PD-1 pathway may be clinically useful. Clearly the immune consequences of MEKi, both in isolation and in combination, requires further study in vivo where complex interactions between multiple cell populations occur.

The era of molecularly targeted cancer therapy has arrived, yet many of the agents now in clinical use have multi-faceted, and, so far, poorly characterized effects on the immune and stromal components of the tumor. With recent successes for both kinase inhibition and immunotherapy there is increasing interest in combining these treatment approaches. To optimize such combinations a detailed understanding of the immune consequences of administering such pharmacological agents is needed. This will require studies evaluating the effects of drugs, individually and in combination, on isolated cell populations in both pre-clinical models and in clinical trials designed to prospectively evaluate immune cell function and validate biomarkers alongside clinical endpoints (for a review of completed clinical trials see).Citation10 Such studies will provide the scientific rationale for the selection, timing and sequencing of kinase inhibitors and immunotherapeutics in order to maximise the rate, depth and duration of disease control. Finally, these evaluations should permit further understanding of the potential for each agent to amplify the anticancer toxicities of the partnered drug as well.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

JSC has honoraria from the speaker bureau of GSK and has served as a consultant/advisory for GSK, BMS and Merck. MCA has received an honorarium in a scientific advisory role for GSK.

References

- Lito P, Rosen N, Solit DB. Tumor adaptation and resistance to RAF inhibitors. Nat Med 2013; 19(11):1401-9; PMID: 24202393; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm.3392

- Andrews MC, Behren A, Chionh F, Mariadason J, Vella LJ, Do H, Dobrovic A, Tebbutt N, Cebon J. BRAF inhibitor-driven tumor proliferation in a KRAS-Mutated colon carcinoma is not overcome by MEK1/2 inhibition. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(35):e448-51; PMID: 24190114; http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.50.4118

- Vella LJ, Andrews MC, Behren A, Cebon J, Woods K. Immune consequences of kinase inhibitors in development, undergoing clinical trials and in current use in melanoma treatment. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2014; 10(8):1107-23; ISN:1744-8409, http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/1744666x.2014.929943

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Wolchok JD. Immune checkpoint blockade. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2014; 28(3):585-600; PMID: 24880949; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2014.02.002

- Vella LJ, Pasam A, Dimopoulos N, Andrews M, Knights A, Puaux AL, Louahed J, Chen W, Woods K, Cebon JS. MEK inhibition, alone or in combination with BRAF inhibition, affects multiple functions of isolated normal human lymphocytes and dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol Res 2014; 2(4):351-60; PMID: 24764582; http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0181

- Callahan MK, Masters G, Pratilas CA, Ariyan C, Katz J, Kitano S, Russell V, Gordon RA, Vyas S, Yuan J, et al. Paradoxical activation of T cells via augmented ERK signaling mediated by a RAF inhibitor. Cancer Immunol Res 2014; 2(1):70-9; PMID: 24416731; http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0160

- Schilling B, Sondermann W, Zhao F, et al. Differential influence of vemurafenib and dabrafenib on patients’ lymphocytes despite similar clinical efficacy in melanoma. Ann Oncol 2014;25(3):747-53; http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt587

- Frederick DT, Piris A, Cogdill AP, Griewank KG, Livingstone E, Sucker A, Zelba H, Weide B, Trefzer U, Wilhelm T, et al. BRAF inhibition is associated with enhanced melanoma antigen expression and a more favorable tumor microenvironment in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19(5):1225-31; PMID: 24504444; http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1630

- Jiang X, Zhou J, Giobbie-Hurder A, Wargo J, Hodi FS. The activation of MAPK in melanoma cells resistant to BRAF inhibition promotes PD-L1 expression that is reversible by MEK and PI3K inhibition. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19(3):598-609; PMID: 23095323; http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2731

- Ascierto PA, Margolin K. Ipilimumab before BRAF inhibitor treatment may be more beneficial than vice versa for the majority of patients with advanced melanoma. Cancer 2014. PMID: 24577788; http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28622