Abstract

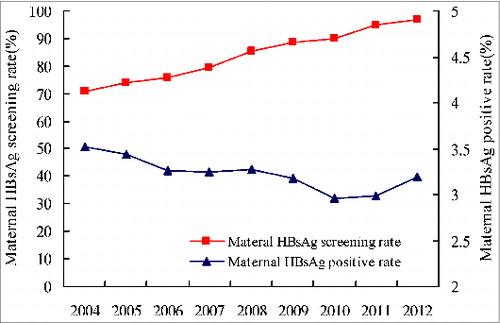

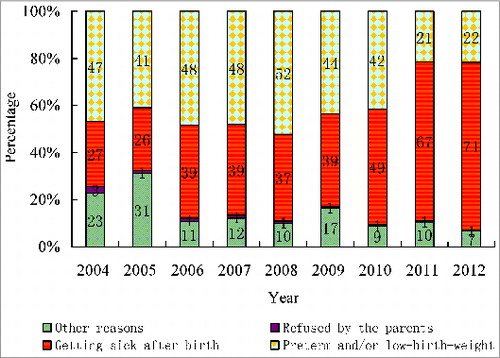

Post-exposure prophylaxis with hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) alone is highly effective in preventing perinatal hepatitis B virus (HBV) transmission and the World Health Organization recommends administering HepB to all infants within 24 h after delivery. Maternal screening for HBsAg and administration of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) in addition to HepB for infants born to HBsAg-positive pregnant women can increase the effectiveness of post-exposure prophylaxis for perinatal HBV transmission. In Shangdong Province, China which has a high prevalence of chronic HBV infection, HepB birth dose and HBIG were integrated into the routine childhood immunization program in 2002 and July 2011 respectively. We assessed progress toward implementation of these measures. Hospital-based reporting demonstrated an increase in maternal screening from 70.7% to 96.9% from 2004–2012; HepB birth dose coverage (within 24 h) remained high (96.3–97.1%) during this period. For infants with known HBsAg-positive mothers, the coverage of HBIG increased from 85.0% (before July 2011) to 92.1% (after July 2011). However, HBIG coverage in western areas of Shandong Province remained at 81.1% among infants with known HBsAg-positive mothers. Preterm/low-birth-weight and illness after birth were the most commonly reported reasons for delay in the first dose of HepB to >24 h of birth. Additional education on the safety and immune protection from HepB and HBIG might help to correct delays in administering the HepB birth dose and low HBIG coverage in the western areas of the Shandong Province.

Introduction

Perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV) from mothers to infants is a major source of chronic HBV infection.Citation1,2 Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) with hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) is 70–95% effective in preventing perinatal HBV transmission among infants born to mothers who are hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive and hepatitis B e antigen positiveCitation3; while HepB and Hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) at birth, followed by 2 to 3 additional doses of HepB, is 85–95% effective.Citation3-5 Studies in areas highly endemic for HBV have shown that passive-active PEP with HBIG and HepB more effectively prevents perinatal HBV transmission than HepB alone.Citation6-8 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends universal HepB as soon as possible after birth, preferably within 24 h regardless of maternal HBsAg status, even in countries with low-endemicity.Citation9 In the United Sates, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers receive HepB and HBIG within 12 h of birth, and HepB before hospital discharge for infants of mothers with known HBsAg-negative status.Citation3

A national survey in 1992 demonstrated a high prevalence of chronic HBV infection in China, with nearly 10% HBsAg-positivity.Citation10 In 2002, China began integrating HepB into its routine childhood immunization program, with an emphasis on the timeliness of the HepB birth dose. Since 2002, HepB has been provided to infants free of charge with a mandatory first dose within 24 h of birth, followed by two additional doses at 1 and 6 mo of age. Infants not receiving a HepB birth dose before hospital discharge were followed up and vaccinated in the immunization clinics near their home. To improve coverage of timely HepB birth dose, all obstetric wards in China were required to establish separate inoculation rooms, with trained nurses to vaccinate all infants with HepB. Beginning in July 2011, the Chinese government also began providing HBIG free of charge for infants born to HBsAg-positive women; HBIG was given concurrently with the HepB birth dose. The cost of maternal HBsAg screening tests, roughly 10 RMB (US$1.6) per test, was not routinely covered by the Chinese government.

Shandong Province is located in the eastern part of China and has a population of 96.8 million.Citation11 In May 2003, the Health Bureau of Shandong Province issued a directive mandating all hospitals with obstetric wards provide to local Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (L-CDC) a monthly report consisting of aggregate HBV immunoprophylaxis data. This study analyzed the rates of maternal HBsAg screening, and the coverage and timeliness of the HepB birth dose in Shandong Province from 2004–2012. Data for HBIG administration available from 2011–2012 were also analyzed.

Methods

Data collection

Per the above mention directive, all the hospitals with obstetric wards were required to report information for each newborn that included mother's name, HBsAg status (positive, negative or unknown), date and time of the infants’ birth, HepB type and lot number, manufacturer, time of injection, and reason for untimely administration. The date and time of HBIG injection were also required to report since January 2011. The above data were aggregated by the hospitals and were reported monthly in three reporting forms: One form summarized the total number of the newborns, the number of the newborns with timely birth dose of HepB and the number of the newborns with delayed birth dose. All the data were grouped separately for infants born to local residents and to immigrant parents. The second form summarized the number of the newborns by maternal HBsAg status and starting in January 2011, the number of the newborns with or without HIBG administration was aggregated by maternal HBsAg status. The third form summarized the main reasons (preterm and/or low-birth-weight, getting sick after birth, refused by the parents and other reasons) for the delayed first dose. These reporting forms were submitted to the CDC at county level where the data were entered into an online database hosted by the provincial CDC.

Definitions

Annual maternal screening rate for HBsAg was the percentage of pregnant women tested for HBsAg during pregnancy or at delivery among all pregnant women with a live birth. Annual maternal HBsAg positive rate was the percentage of HBsAg-positive women among all women tested for HBsAg before delivery annually. Preterm was defined as being born before the 37th week of gestation. Low birth weight was infant birth weight less than 2500 g. HepB birth dose coverage was the percentage of infants who received HepB within 24 h of birth among all live births, and HBIG coverage was the percentage of infants who received HBIG before hospital discharge among infants of HBsAg-positive women. Locally born infants were defined by having a mother and/or father whose registration was in the same county where the infant was born. Immigrant infants were defined by a mother and/or father's registration in a county different from the infant's birth county, which potentially affected access to care.

Data input and analysis

Data in monthly reports were entered into Epidata (Version 3.02) with statistical analyses utilizing SPSS (Version 15.0). We calculated program outcome indicators including maternal screening rate, maternal HBsAg positive rate, HepB birth dose coverage, and HBIG coverage according to the above definitions. Seventeen prefectures of Shandong Province were divided into five areas according to geographical location; rates of maternal HBsAg screening, HBIG coverage and HepB birth dose were compared among the five areas. The proportion of infants who received the HepB birth dose at different intervals after birth, <12 h, 12–24 h, and >24 h were calculated by the status of maternal HBsAg; these data were first available in September 2012.

Results

Maternal HBsAg screening and HBIG administration

From 2004–2012, maternal HBsAg screening rate increased from 70.7% to 96.9%; maternal HBsAg-positive rate remained stable at 3.2–3.5% (). During the first six months of 2011, HBIG coverage was 84.9% (12490/14704) in the province and was 93.3% (2655/2845), 70.4% (2381/3381), 93.0% (3047/3278), 86.2% (1745/2024) and 83.8% (2662/3176) in the eastern, western, southern, northern and middle region, respectively. During July 2011 through 2012, HBIG coverage of the province increased to 92.1% with obvious increases observed in four of the five geographic regions comparing to the coverage during the first half of 2011. With the exception of the western region (81.1%), HBIG coverage was over 95% (95.3–98.3%)(). Maternal HBsAg screening rates by geographic area were between 94.6–98.7% ().

Table 1. HBsAg screening rate among pregnant women, rates of infant HBIG administration and HepB birth dose coverage by region, Shandong Province, July 2011-December 2012

HepB birth dose coverage

From 2004–2012, HepB birth dose coverage rate within 24 h of birth was 96.3% to 97.1% per calendar year within the province, an increase from <80.0% before 2004 (data not shown).Citation12 Coverage was 94.5% among locally born infants compared with 96.7% among immigrated infants in 2012. Between September and December 2012, timing of the HepB birth dose was within 12 h for 69.0% and 12 to 24 h for 27.3% of infants. The corresponding proportions were similar both among infants of HBsAg-positive, HBsAg-negative mothers, and HBsAg-unknown mothers and among infants with different vaccination status ().

Table 2. HepB birth dose coverage with different interval after birth by maternal HBsAg and vaccination status in Shandong Province, September to December 2012*

The distribution of reasons given for HepB birth dose delay beyond 24 h of life shifted between 2004 and 2012. From 2004–2010, the leading reason was preterm/low birth weight, accounting for between 41.0% (4085/9955) and 52.2% (10002/19165). In 2011 and 2012, the reason of preterm/low birth weight decreased to 21.5% (4943/22999) and 21.8% (5618/25730), respectively, and was replaced by illness, which accounted for 67.3% (15471/22999) and 70.8% (18228/25730), respectively ().

Discussion

We report progress of the perinatal HBV prevention program in Shandong Province, China from 2004–2012. The results demonstrated steady progress in administering HBV immunoprophylaxis, and identified potential areas for further improvement. Although universal HepB coverage for infants in China began in 1992, HepB was self-paid and there were no guidelines for vaccination until HepB was integrated into China's routine immunization schedule in 2002. The establishment of inoculation rooms in obstetric wards and increased training of healthcare professionals contributed to an increase in HepB birth dose coverage to above 96% since 2004. HBIG coverage among infants born to known HBsAg-positive mothers increased to above 92% after July 2011.

From 2004–2010, the reason for approximately one half of delayed HepB birth doses was preterm and/or low birth weight. Worldwide, 10% of all live births are preterm and 85% are in Africa and Asia.Citation13 In some urban areas of China, the prevalence of preterm birth is reported to be 7.8%, far lower than the rate of preterm/low birth weight given as the reason for delayed HepB.Citation14,15 Some Chinese physicians may have delayed HepB at birth to avoid the perception that HepB contributes to adverse events in these higher risk infants, despite overwhelming evidence of HepB safety and efficacy.Citation16

A recent study in China showed that delayed HepB birth dose among preterm infants was significantly associated with an increased risk for mother-to-child HBV transmission.Citation17 Preterm/low-birth weight infants should receive HepB at birth; for infants <2000 g, the HepB birth dose should not be counted toward the primary series; 3 additional doses (total of 4 doses) are needed for these infants because seroprotection rates after 3 doses can be lower than among term infants with normal birth weight.Citation3,9,18 In the second half of 2010, province-wide education and training on HepB birth dose in preterm/low birth weight infants was provided for physicians and nurses within obstetrics wards, and the proportion of preterm/low birth weight infants with delayed birth dose decreased in 2011 and 2012. Consideration for official directives affirming the utility and safety of HepB birth dose among these infants might be useful, along with national training to improve timeliness of birth dose coverage in this population.

Illness became the leading reported reason for delayed HepB birth dose in 2011–2012, accounting for about 70% of all HepB doses delayed beyond 24 h of life. Specific diagnoses were not reported. Among infants born to HBsAg-positive mother, 2.7% had the delayed birth dose in the province in 2012, leading to a increased risk of HBV transmission.Citation8,9 In China, there is no official guidance for HepB birth dose among infants who are ill. We speculate that some healthcare providers may have delayed birth dose administration because of concerns about the safety of HepB with concomitant illness.

HepB is safe and contraindicated only for individuals with a history of allergic reactions to any of the vaccine's components according to WHO guidelines.Citation9 ACIP recommends deferring routine immunization in persons with moderate or severe acute illness until the illness resolves, but does not address administration of HepB birth dose among ill infants born to HBsAg-positive women.Citation3,19 The assumption has been that all HBV-exposed infants should receive HBIG and HepB at birth because the known benefit of immunoprophylaxis to prevent perinatal HBV transmission outweighs any theoretical increased risk for an adverse reaction. Future work should focus on education of clinicians regarding the importance of early immunoprophylaxis to prevent perinatal HBV transmission, focusing on infants born to HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-unknown mothers.

In China, the HepB birth dose coverage was defined as infant vaccination within 24 h after birth. The birth dose coverage was stable and high at 96–97% in the province from 2004–2012, with similar among different geographic regions. WHO recommends all infants receive their first dose of HepB as soon as possible after birth, preferably within 24 h.Citation9 Some studies have found that timing of PEP may have an impact on efficacy.Citation5,20 In some nations, HepB birth dose is recommended within 12 h after birth for infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers.Citation3,19,21 Our study showed that 69.0% of newborn infants received HepB in Shandong Province within 12 h of birth; the percentage was 70.2% among newborn infants born to HBsAg-positive women. In areas with high rates of in-hospital births such as Shandong Province, the feasibility of administrating vaccine within 12 h would be high. Changes in the standard for birth dose administration from 24 h to 12 h among infants with HBsAg-positive mothers could be evaluated in China; such measures would best be evaluated in conjunction with assessing outcomes of exposed infants and maternal HBV titers.

Since July 2011, HBIG has been given free of cost to the infants born to HBsAg positive mothers in Shandong Province. Overall HBIG coverage increased from 85.0% in 2011 to 92.1% in 2012. HBIG coverage was uniquely lower in the western areas compared with other areas of Shandong Province. Western region is the most economically backward area in the province where the people's awareness about HBV prevention might be relatively low. In Heze, the biggest manuscript in the western area of Shandong Province with a population of 8.3 million, the government encouraged the hospitals transitioning from public to private in the last few years, which might also have had an impact on HBIG coverage rates. Additional study is required to understand the reasons for lower HBIG coverage. Maternal HBV screening has increased from 70% to 97% in the last nine years. This increase and high percentage represent tremendous progress despite costs of screening being incurred by individual families. Economic development, improvement in medical care and public health infrastructure, and greater public health consciousness are likely reasons for success. Since post-exposure prophylaxis with both HepB and HBIG is more effective compared with HepB alone for prevention of perinatal HBV transmission,Citation3 continued efforts to support maternal HBsAg screening and HBIG coverage are needed.Citation6,7 HBsAg testing free of charge might improve the rates of screening among pregnant women, cost-effectiveness studies are needed to evaluate.

There are several limitations to our study. Information was derived from monthly reports, which provided aggregate data. When data were reported from the hospitals to Shandong Provincial-CDC, few quality control measures were taken. Because there are no recommendations in China for testing HBV-exposed infants for infection or antibody response to vaccination, we were unable to report perinatal outcomes for HBV infection.

In summary, in recent years Shandong Province has achieved high levels of maternal HBV screening rates, HepB birth dose coverage, and HBIG coverage among infants with known HBsAg-positive mothers. Continued education and training of healthcare providers is needed to ensure longer-term success. Future research should focus on reasons for HepB birth dose delays, education of providers on the immunogenicity and safety of HepB vaccination, and for determining the reasons for low HBIG coverage in the western areas of the province.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

There were no potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues in the hospitals and the CDCs at county and prefectural level in Shandong Province for data collection and reporting.

Funding

This study was supported by the grants from the Major Project of National Science and Technology (No. 2012ZX10002–2001) and from the Shandong Medical and Health Science and Technology Development Programs (No. 2011HD006).

References

- Lavanchy D. Worldwide epidemiology of HBV infection, disease burden, and vaccine prevention. J Clin Virol 2005; 34(Suppl 1):S1-3; PMID:16461208; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1386-6532(05)00384-7

- Jonas MM. Hepatitis B and pregnancy: an underestimated issue. Liver Int 2009; 29(Suppl 1):133-9; PMID:19207977; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01933.x

- Mast EE, Margolis HS, Fiore AE, Brink EW, Goldstein ST, Wang SA, Moyer LA, Bell BP, Alter MJ; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) part 1: immunization of infants, children, and adolescents. MMWR Recomm Rep 2005; 54(RR-16):1-31; PMID:16371945

- Denis F, Ranger-Rogez S, Alain S, Mounier M, Debrock C, Wagner A, Delpeyroux C, Tabaste JL, Aubard Y, Preux PM. Screening of pregnant women for hepatitis B markers in a French Provincial University Hospital (Limoges) during 15 years. Eur J Epidemiol 2004; 19:973-8; PMID:15575357; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10654-004-5755-9

- Wong VC, Ip HM, Reesink HW, Lelie PN, Reerink-Brongers EE, Yeung CY, Ma HK. Prevention of the HBsAg carrier state in newborn infants of mothers who are chronic carriers of HBsAg and HBeAg by administration of hepatitis-B vaccine and hepatitis-B immunoglobulin. Double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet 1984; 1:921-6; PMID:6143868; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(84)92388-2

- Hsu HM, Lee SC, Wang MC, Lin SF, Chen DS. Efficacy of a mass hepatitis B immunization program after switching to recombinant hepatitis B vaccine: a population-based study in Taiwan. Vaccine 2001; 19:2825-9; PMID:11282193; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00015-9

- Yang YJ, Liu CC, Chen TJ, Lee MF, Chen SH, Shih HH, Chang MH. Role of hepatitis B immunoglobulin in infants born to hepatitis B e antigen-negative carrier mothers in Taiwan. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003; 22:584-8; PMID:12867831; http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000073123.93220.a8

- Lee C, Gong Y, Brok J, Boxall EH, Gluud C. Effect of hepatitis B immunisation in newborn infants of mothers positive for hepatitis B surface antigen: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2006; 332:328-36; PMID:16443611; http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38719.435833.7C.

- WHO. Hepatitis B vaccines. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2009; 84:405-19; PMID:19817017

- Dai ZC, Qi GM. Viral Hepatitis Seroepidemiological survey in Chinese population 1992-1995. Beijing, China Science and technical documents publishing house 1997:39-59

- Shandong Provincial Bureau of Statistics Survey Offince of the National Bureau of Statistics in Shanghai. Shandong statistical yearbook. Beijing, China Statistics Press 2013:57.

- Zhang L, Xu A, Yan B, Song L, Li M, Xiao Z, Xu Q, Li L. A significant reduction in hepatitis B virus infection among the children of Shandong Province, China: the effect of 15 years of universal infant hepatitis B vaccination. Int J Infect Dis 2010; 14:e483-8; PMID:19939719; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2009.08.005

- Beck S, Wojdyla D, Say L, Betran AP, Merialdi M, Requejo JH, Rubens C, Menon R, Van Look PF. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bull World Health Organ 2010; 88:31-8; PMID:20428351; http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.08.062554

- Subspecialty Group of Neonatology, Pediatric Society, Chinese Medical Association. An initial epidemiologic investigation for preterm infants in China. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi 2005; 7:25-8.

- Langkamp DL, Hoshaw-Woodard S, Boye ME, Lemeshow S. Delays in receipt of immunizations in low-birth-weight children: a nationally representative sample. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001; 155:167-72; PMID:11177092; http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.155.2.167

- Zuckerman JN. Protective efficacy, immunotherapeutic potential, and safety of hepatitis B vaccines. J Med Virol 2006; 78:169-77; PMID:16372285; http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.20524

- Li F, Wang Q, Zhang L, Su H, Zhang J, Wang T, Huang D, Wu J, Yan Y, Fan D. The risk factors of transmission after the implementation of the routine immunization among children exposed to HBV infected mothers in a developing area in northwest China. Vaccine 2012; 30:7118-22; PMID:23022150; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.031

- Saari TN; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. Immunization of preterm and low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2003; 112:193-8; PMID:12837889; http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.112.1.193

- Atkinson WL, Pickering LK, Schwartz B, Weniger BG, Iskander JK, Watson JC; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. General recommendations on immunization. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2002; 51(RR-2):1-35; PMID:11848294

- Stevens CE, Toy PT, Tong MJ, Taylor PE, Vyas GN, Nair PV, Gudavalli M, Krugman S. Perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission in the United States. Prevention by passive-active immunization. JAMA 1985; 253:1740-5; PMID:3974052; http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1985.03350360066020

- Institute of Medicine. Hepatitis and liver cancer: A National Strategy for prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press, 2010.