ABSTRACT

The growing threat of climate change and global tensions resulting in energy shortages has led many countries to reconsider the merit of nuclear energy to meet national emissions reduction targets and provide domestic energy security. Australia's unique nuclear experience has led to a prohibition on building nuclear reactors, distinctive from other G20 countries. With Australia's energy transition underway, an exploration of the discourse surrounding nuclear energy in the national debate is timely to understand the barriers and opportunities for nuclear power in our energy future. This article investigates how nuclear energy is framed in media and by debate stakeholders, how this potentially constraints the energy source, and the influence of an increasingly carbon-conscious world on the debate. A critical discourse analysis of nuclear energy in Australia and semistructured interviews are used to understand the discourse landscape. The study finds that the discursive practises of politically conservative social actors engaged in the debate significantly shape how nuclear energy is perceived and received by the public, contributing to a polarised and politicised debate. It highlights the significance of climate change and energy security discourses in sustaining media salience whilst exposing the exclusionary nature of select nuclear energy rhetoric which limit the debate. Further research into public perceptions and discourses around nuclear energy in Australia is required given the need to decarbonise.

Introduction

As climate change becomes increasingly apparent in Australia and internationally, it is necessary and urgent to decarbonise our energy grids (IPCC Citation2023). The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 exacerbated global energy insecurities as gas prices skyrocketed (Osička and Černoch Citation2022). Within this context, nuclear energy has been posited as a solution by some environmental, business and political stakeholders. Countries, including China (Hibbs Citation2018), Russia, and India (Pioro et al. Citation2020) have expanded their nuclear power capacities.

The (re)emergence of nuclear energy as a proposed solution to climate change has generated a new identity within environmentalism, namely pro-nuclear environmentalists, who resist the anti-nuclear stance of mainstream environmentalism (Van Munster and Sylvest Citation2015). Pro-nuclear environmentalists argue that countries should rapidly adopt nuclear energy to achieve decarbonisation (Shellenberger Citation2020) utilising future generation small modular reactors (SMRs), which are claimed to be simpler, safer, and cheaper than existing technologies (Vujić et al. Citation2012). In contrast, many environmentalists posit that 100% renewables will achieve net zero emissions (Nolt Citation2022).

Australia occupies a unique position regarding nuclear energy matters, being one of a few developed countries without nuclear power despite holding the world’s largest known uranium deposits and being the third largest exporter of uranium (World Nuclear Association Citation2022a). In addition, nuclear energy has been banned both federally and at various state levels for over two decades (Eckermann Citation2018). This ‘Janus-faced’ position originated from the environmentalist, anti-uranium and anti-war movements of the 1980s (Lowe Citation2021). An increasing number of right-wing Australian politicians have, however, recently expressed support for nuclear energy, calling for its prohibition to end and a ‘mature debate’ about the energy source to begin. Additionally, opinion polls suggest public support for nuclear energy is increasing, whilst federal and multiple state inquiries into nuclear energy have also occurred. As such, this study aims to investigate the influence of climate change on the nuclear energy debate in Australia and explore its framing in media and by debate stakeholders. In particular, we aim to identify the social and political contexts that stimulate and stifle discussion of nuclear energy in Australia. Second, we identify the social actors who participate in this discourse and how they impact the debate and third, we aim to analyse how nuclear energy has been framed in media and by stakeholders in the debate and how this may constrain this form of energy generation in Australia. These research aims parallel Norman Fairclough’s three-part analysis in the Critical Discourse Analysis approach, which is used to answer these research questions.

Literature review

Critical discourse analysis

The understanding of discourse pioneered by Michel Foucault (see Foucault (Citation2003; Citation1975; Citation1979)) posits that forms of representation are combined to shape the ‘truth’ of objects of knowledge and appropriate social conduct (Cresswell Citation2009). In this way, forms of representation actively constitute societal knowledge about various phenomena, holding significant power in society (Berg Citation2009). Media is implicit in perpetuating various discourses, shaping how issues are publicly understood and debated (Boykoff Citation2018).

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is an interdisciplinary research method for the study of media discourses. Discourse analysis is defined by Rogers-Hayden, Hatton, and Lorenzoni (Citation2011, 109) as ‘a process, usually formal, in which the language of a person, organization, or community is scrutinized so that patterns and key themes can be identified’. Fairclough, Mulderrig, and Wodak (Citation2011, 357) described CDA as a ‘problem orientated interdisciplinary movement’ involving various theoretical lenses and methodologies developed by a cohort of social science scholars. CDA is specifically designed to analyse ‘structural relations of dominance, discrimination, power and control’ as manifested in discourse (cited in Blommaert and Bulcaen Citation2000, 448; Wodak Citation1999, 204).

CDA emerged in the late 1980s, pioneered by the works of Fairclough (Citation1992), Wodak (Citation1999) and van Dijk (Citation2013). Fairclough (Citation1992) established a three-part analysis process: discourse-as-text, discourse-as-discourse-practice, and discourse-as-social-practice. Discourse-as-text is concerned with the analysis of concrete instances of discourse via linguistic features in texts such as word choice, grammar and semantic relations (Catalano and Waugh Citation2020). Discourse-as-discourse-practice is concerned with analysis of the production, consumption and circulation of these concrete linguistic objects (Blommaert and Bulcaen Citation2000). Discourse-as-social-practice is concerned with analysing the sociocultural context behind textual production (Blommaert and Bulcaen Citation2000).

Nuclear (energy) discourse

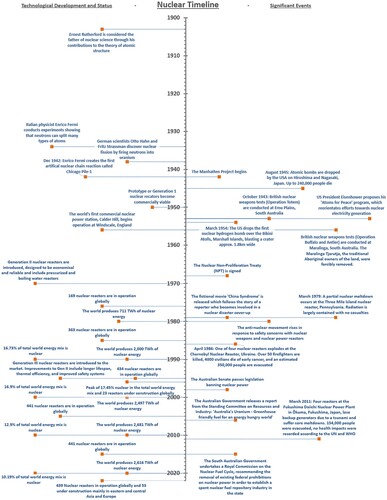

The discourse surrounding nuclear energy, has been characterised by rapid changes in public perception and ongoing scepticism. provides a timeline of nuclear technology development alongside significant nuclear events, which have shaped public discourse. Nuclear energy emerged out of World War II, resulting in an ongoing association with its destructive capacities (Gamson and Modigliani Citation1989). Following World War II, the United States of America (USA) shifted its focus to include peaceful civilian uses for nuclear technology in the form of nuclear energy (U.S. Department of Energy Citation2022). Deliberate discursive shifts emerged in political rhetoric and within film and television (Palmero Citation2019). Simultaneously, nuclear bomb testing occurred in various countries, including in the USA with the devastating bombing of Bikini Atoll (National Cancer Benefits Center Citation2022).

The discourse that developed during the 1940s and early 1950s capitalises on nuclear technology’s inherent mysterious nature and discursive mystification (Kinsella Citation2005) which restricted capacity for public discussion (Irwin, Allan, and Welsh Citation2000), thereby enhancing the influence of media and other discursive institutions to shape the hegemonic view of nuclear technologies (Renzi et al. Citation2017). The 1960s was characterised by a discourse of nuclear dualism amid cold war tensions where nuclear technology’s peaceful and destructive uses were compared by the public (Gamson and Modigliani Citation1989). The 1970s saw a proliferation of nuclear reactors being built globally, while the oil crisis of the early 1970s introduced energy independence discourses in favour of nuclear power (Gamson and Modigliani Citation1989). The partial nuclear meltdown at the Three Mile Island (TMI) nuclear reactor, near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in 1979 (World Nuclear Association Citation2022e) marked a turning point in discourse through the event coinciding with the release of The China Syndrome, a fictional film about a news reporter embroiled in a nuclear meltdown cover-up that was discursively used within news reporting (Shaw Citation2013). Discourses concerned with trust in authorities were evident following the TMI disaster and were reinforced in 1986 when the Chernobyl 4 Nuclear Reactor in the former USSR (now part of Ukraine) exploded due to a poorly run safety procedure and a flawed reactor design (Gamson and Modigliani Citation1989; World Nuclear Association Citation2022c).

At the turn of the twenty-first century, nuclear energy’s share in the global energy mix was plateauing at around 16% and far fewer reactors were under construction (Roser, Ritchie, and Rosado Citation2022). By the mid-2000s, however, the potential of nuclear energy was increasingly being recognised due to its low-carbon nature and capacity to mitigate climate change. A New Nuclear Build program in the United Kingdom (UK) was announced in 2008 and increasingly pro-nuclear government rhetoric began being accepted by media outlets across the country (Doyle Citation2011) and reluctantly by the public (Bickerstaff et al. Citation2008). This nuclear renewal was underpinned by discourses of energy independence and energy security supported by perceived gas insecurities and national emissions reductions targets (Rogers-Hayden, Hatton, and Lorenzoni Citation2011). In 2011, however, three reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, Japan, lost backup generators due to a major tsunami, suffering core meltdowns (World Nuclear Association Citation2022d) and shifting public opinion away from nuclear energy.

Since 2011, many studies have examined how nuclear energy is framed by governments and in media, including in China (Hibbs Citation2018), South Korea (Yun Citation2012), Ireland (Devitt et al. Citation2019), Switzerland (Arlt, Rauchfleisch, and Schäfer Citation2019) and the Netherlands (Vossen Citation2020), plus there are comparative studies across countries (Kepplinger and Lemke Citation2016). Most studies are event-driven and focus on ‘critical discourse moments’, being ‘periods that involve specific happenings’ (Carvalho Citation2008, 166). Several studies found that media shifted its stance away from supporting nuclear energy as a result of the Fukushima accident, leading to changes in public opinion (Devitt et al. Citation2019). Other studies including in Czechia and Slovakia (Kratochvíl and Mišík Citation2020), Turkey (Balkan-Sahin Citation2019) and Hungary (Sarlós Citation2015), note the use of climate change and energy security discourses in pro-nuclear media representation and right-wing government rhetoric. Right-wing media outlets support nuclear dominated debates in South Korea (Yun Citation2012), Spain (Mercado-Sáez, Marco-Crespo, and Álvarez-Villa Citation2019) and Turkey (Balkan-Sahin Citation2019).

In 2022, just under 10% of the total world energy mix constitutes nuclear energy, a decline from its peak of 17.45% in 1996 (see ) (Roser, Ritchie, and Rosado Citation2022). As of July 2023, 57 nuclear reactors were under construction, mainly in middle, east and southeast Asia (International Atomic Energy Agency Citation2023). These trends follow the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) inclusion of nuclear energy within all mitigation pathways in their 2022 report (Abdulla et al. Citation2022). Given many countries’ commitments to net-zero targets through the 2015 Paris Agreement, nuclear energy is seen as a long-term viable solution for decarbonisation (Abdulla et al. Citation2022), creating a tension between protecting the environment from future nuclear accidents and mitigating climate change.

The ‘reluctant acceptance’ (Bickerstaff et al. Citation2008) of nuclear energy as a solution to climate change during the 2000s and 2010s exhibits a shift in public perception and a destabilising of the environmental movement. Pro-nuclear environmentalists or ‘enlightened’ environmentalists (Pinker Citation2021) argue climate change threats exceed those of nuclear energy, requiring us to rapidly embrace nuclear energy (Van Munster and Sylvest Citation2015) in line with ecomodernist approaches. This is perceived as dividing the environmental movement into what McCalman (Citation2019) termed the arcadian (focused on the conservation or preservation of nature) and utilitarian schools of thought, with the latter seen as responding pragmatically to concerns such as climate change, although the environmental movement has always been divided (McManus Citation1996; Pepper Citation1984). Energy independence and energy security discourses, as well as ‘techno-rationality’ and ‘abstract faith in science’ discourses, underpin the arguments of pro-nuclear environmentalists (McCalman Citation2019; McCalman and Connelly Citation2019). These utilitarian environmentalists point to the potential of future ‘fourth generation technologies’ such as SMRs to justify their position (McCalman and Connelly Citation2019). Summers et al. (Citation2019) find that similar ‘technoscientific imaginary’ argumentations are utilised by nuclear professionals against ‘antis’, culminating in denigrations summarised as accusations of scientific ignorance and utilisation of religious-like dogma.

Nuclear (energy) in Australia

Australia has a unique relationship and history with nuclear technology. Between 1952 and 1963 the British government, with support from the Australian government, conducted atomic bomb testing in South and Western Australian Indigenous lands, knowing they were occupied by Indigenous communities (Lowe Citation2021). This historical abuse of Indigenous People signals an ongoing ‘trust deficit’ between Australians and the Government and a ‘widespread cynicism toward … nuclear’ Ogilvie-White (Citation2015, 62).

The Australian anti-nuclear movement can be characterised as a fusion between the anti-war, anti-uranium and environmentalist movements (Lowe Citation2021). British atomic testing marks the beginnings of anti-nuclear sentiment, compounded by French nuclear testing in the Pacific (Kirchhof and Meyer Citation2014) and uranium mining inquiries in the mid-1970s (McCausland Citation2001). McGaurr and Lester (Citation2009) argue that the complex political history underpinning nuclear energy in Australia, including issues of Indigenous land rights, exploitation and environmental risks, has stifled political discussion of commercial nuclear uses.

Australia has built no commercial nuclear energy projects due to the abundance of cheap coal and gas deposits (Eckermann Citation2018), however, Australia did open uranium mines in various states (Kay Citation2022) while the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) operates the OPAL research reactor at Lucas Heights (Sydney) for research and nuclear medicine production (World Nuclear Association Citation2022b).

In 1998 the Australian Senate passed legislation, codified in the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, prohibiting the construction of nuclear power plants, complementing separate state prohibition acts passed in the 1980s and 1990s (Cronshaw Citation2020). The Australian and various state governments have since, however, published various reports and established inquiries into the viability of lifting the existing prohibitions and expanding the nuclear energy industry in 2006, 2015 and 2019 (Cronshaw Citation2020). In September 2021, the Australian government announced an agreement with the USA and UK to acquire nuclear-propelled submarines under the AUKUS trilateral security pact (Murphy and Daniel Citation2021), thereby reintroducing debate about establishing a nuclear energy industry in Australia (Nuclear Engineering International Citation2022).

A number of academic papers explore aspects of nuclear technology and discourse within Australia including media representation (McGaurr and Lester Citation2009), the impact of climate change and the Fukushima accident on public perception (Bird et al. Citation2014), demographic differences in risk perception (Harris et al. Citation2018), consumer preferences (Borriello, Burke, and Rose Citation2019), economic opportunity (Turner Citation2020), and the competitiveness of SMRs in Australia (Malatesta Citation2021). McGaurr and Lester (Citation2009) analysed how The Australian newspaper correlated reporting on climate change and nuclear energy in the period 2005–2007, finding a shift in the framing of nuclear energy from an environmental problem to a technological solution to the climate issue. The Australian dominated reporting on nuclear energy during the study period with the announcement and release of findings of the 2006 federal inquiry into nuclear energy proving particularly salient (McGaurr and Lester Citation2009). McGaurr and Lester (Citation2009, 184) identify several discourse frames including nuclear fix, which promulgates a faith in nuclear technology to solve climate change, the debate we have to have, which argues that nuclear energy should be debated, and cool heads/hot heads, which calls for a rational response to climate change incorporating nuclear energy and criticising ‘irrational’ anti-activists.

Overall, minimal research has been conducted on nuclear energy in Australia, and none of the above studies use Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA).

As outlined, the discourse surrounding nuclear energy has been extensively researched since the 1980s, with most studies focusing on critical discourse moments. Research on nuclear discourse within the Australian context, however, is limited to investigating media representation within the context of the Australian Government’s inquiry into nuclear energy in 2006 (McGaurr and Lester Citation2009). Given the 2015 Paris Agreement, the nuclear submarine deal in 2021 and the emergence of pro-nuclear environmentalists, this study aims to investigate the influence of climate change on the nuclear energy debate in Australia and explore its framing in media and by debate stakeholders by using CDA to examine discourse between 2015 and 2022, addressing the issue of a lack of studies conducted over longer time periods (Kristiansen Citation2017).

Research methods

Newspaper analysis

The research program analysed the content of interview transcripts and articles from five major Australian publications (the ABCFootnote1, The Australian, The Advertiser, The SMH, and The Age). These national and state publications were chosen based on their editorial positions, geographical spread and correspondence to state inquiries into nuclear energy. Important details of the chosen newspapers are provided in . The editorial position of the newspaper was chosen based on its ownership. The Saturday Paper and The Guardian Australia newspapers were searched but with only 8 and 6 results, respectively, these papers were excluded.

Table 1. Summary of the newspapers chosen in this study.

Factiva was used to search for articles (print and online) between January 2015 and June 2022, which covered state inquiries in 2015 and 2019, the Paris Agreement (2015) and the announcement of the AUKUS submarine deal (2021).

A scoping exercise was conducted to identify appropriate keywords for searching Factiva. The keywords were chosen based on a trial-and-error method where various word arrangements were tested with filter functions until a satisfactory sample of articles was found. The final keywords adopted as shown in the Factiva search format were: atleast2 nuclear energy or atleast2 nuclear power or (nuclear energy and nuclear waste).

NVivo was used to organise, code and analyse the data. The codes were chosen based on Carvalho’s (Citation2008) analytical framework and Reynold’s (Citation2019) coding scheme, which adopt a Fairclough inspired three-tier analysis, focusing on media representations through time and across publications. The initial codes chosen were tested for relevance across time by analysing articles between January and March of 2015 and then 2019, with the initial codes remaining relevant in 2019.

Interviews

Interviews were conducted with stakeholders engaged in the nuclear energy debate in Australia as well as journalists who write about energy issues. A list of potential interviewees was generated from newspaper articles, websites, television and other publicly accessible sources, including a range of stakeholders from both sides of the nuclear debate.

An event at ANSTO in June 2022 resulted in 2 people following up via email, while a book launch in July 2022 for ‘Fact or Fission’ by Richard Broinowski added another interviewee. No official representative from ANSTO was engaged given the organisation’s affiliation with the Australian Government and the legality surrounding discussing the nuclear energy prohibition. Current or former affiliates to ANSTO interviewed provided responses wholly based on their own personal opinions. Overall, 20 semi-structured interviews were conducted: 19 virtually and 1 in person. Saturation of participant responses was achieved. An identifying scheme was developed, to check for bias, with 11 pro-nuclear, 4 anti-nuclear, 3 neutral and 2 interviewees’ position being unknown. The associated coding (P = pro-nuclear, A = anti-nuclear, N = neutral, U = unknown) is used when interviewees are quoted. Where interviewees are named, their consent was provided.

The following section presents the results derived from these methods.

Results

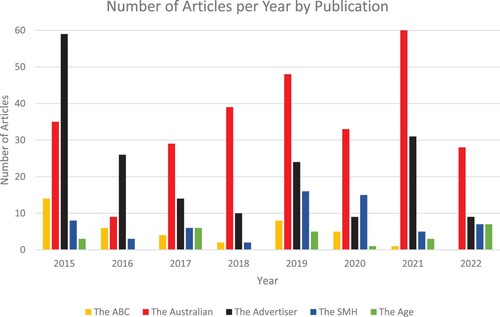

A total of 593 articles between January 2015 and June 2022 were analysed, comprising 40 from the ABC, 285 in The Australian, 181 in The Advertiser, 62 in The SMH and 25 in The Age.

The number of articles published annually in the study period is shown in .

demonstrates that a majority of reporting on nuclear energy in Australia comes from The Australian and The Advertiser publications.

The importance of climate change and the necessity to decarbonise was cited as a leading cause behind current discussions around nuclear energy in Australia. Nine participants, identifying in both the proponent and opponent camps, referenced this factor.

It’s all driven by the climate change debate.

George Takacs (N1)

So I think that’s why it’s cropped up again, now, in particular, is that dysfunction of the National Energy Market (NEM), failure of the market, reality that the power prices have proved high, … . The conversation starts again.

Ben Heard (P11)

When discussing the current nuclear prohibition, many articles (26/49) referenced its constraining nature on commercial opportunity and debate. Both proponents and opponents of nuclear energy similarly emphasised the constraining qualities of the prohibition on nuclear energy in Australia. Jasmin Diab (P8) remarked that the CSIRO would not look at nuclear energy in their contribution to the Technology Investment Roadmap because of its illegality. Another respondent (P2) argued that the prohibition generates uncertainty over public discussion of nuclear energy.

Renewable energy was frequently discussed in opposition to nuclear energy in media, with their areas of compatibility rarely noted. This aligns with the rhetoric of interviewees who regularly juxtaposed nuclear energy with wind and solar power, especially pro-renewables opponents of nuclear energy.

With regards to energy security, nuclear energy was framed as addressing these issues mainly by right-wing papers. This is mirrored by proponent interviewees who utilised the discourse of energy security to argue for Australia’s adoption of nuclear energy, specifically referring to the current renewables transition and increasing electricity prices.

A large portion of articles discussing the nuclear debate argued that nuclear energy should be discussed and considered in Australia’s future energy mix, particularly SMRs, largely from right-wing outlets. Interviewees on both sides of the debate also noted future SMRs, although with opposing enthusiasms.

The attractive thing in Australia is … small modular reactors.

Adi Paterson (P9)

They are paper reactors fuelled on ink. They don’t exist.

Mark Diesendorf (A3)

Framing of anti-nuclear advocates

The use of words relating to faith when criticising anti-nuclear people was isolated to right-wing media, particularly in opinion pieces. An opinion piece by right-wing commentator Andrew Bolt in The Advertiser (Primitives Hold Power – 13 June 2022) argues that political backlash against nuclear is ‘back-to-the-caves primitivism, driven not by reason but the latest Earth-worshipping faith’. Similarly to this media rhetoric, three interviewee proponents utilised religious connotations to describe anti-nuclear/pro-renewables stakeholders. Right-wing media also framed opponents as technologically slow through the use of words like ‘primitive’ and ‘luddites’.

Framing of pro-nuclear people

Proponents of nuclear energy are framed as ‘rational’ and modern. One article in The Advertiser utilises the changed stance of Zion Lights (an activist formerly with Extinction Rebellion UK) to express she’s ‘seen the light and switched to nuclear’ (Former rebel now spruiking nuclear cause – 24 October 2021). Two proponent participants similarly noted the ‘rational’ and ‘honest’ nature of being a pro-nuclear environmentalist, for example:

You cannot be an intellectually honest environmentalist and be anti-nuclear.

Logan Smith (P10)

In the conducted interviews, both sides of the debate expressed frustration about a tension between proponents arguing about a lack of debate and opponents arguing that the issue has already been debated. Proponents expressed a ‘lack of good faith debate’ (P11), exacerbated by partisan media treatment.

Most interviewees agreed that the debate is polarised in Australia. Four participants remarked that a reason for its polarisation is that nuclear energy has been ideologically assigned to conservatism, such as:

[Nuclear energy] has a real identitarian [sic] marker of conservatism in Australia, which is deeply unhelpful, because that really agitates the conversation to be almost immediately and always quite adversarial, and quite ugly.

Ben Heard (P11)

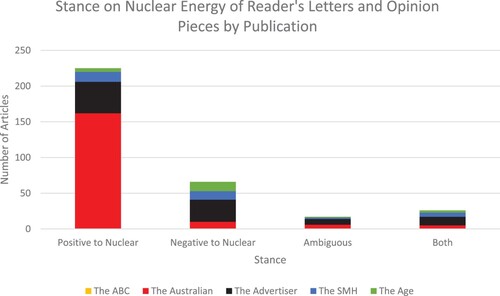

In addition to , opinion writers, their relevant affiliations and stance taken on nuclear energy were considered. A majority of opinion writers published in right-wing outlets (42/51) have a positive attitude towards nuclear energy (30/51). In contrast to the right-wing media, The SMH and Age published less opinion pieces and generally provide a greater balance of proponent and opponent views.

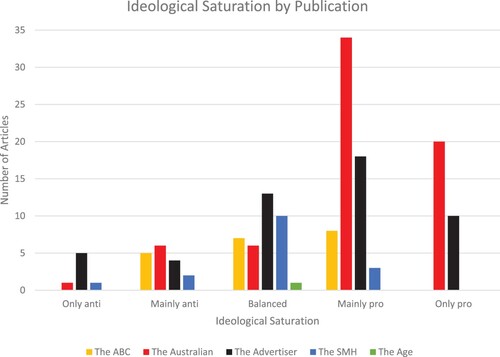

As shown in , right-wing media outlets dominated articles coded with pro-nuclear ideological saturation.

Paralleling this saturation, interviewees on both sides of the debate noted the dominance and promotional nature of News Corporation (The Australian & The Advertiser) in the debate.

Three participants noted that the topic of nuclear energy can be easily dismissed by people politically opposed to right-wing media:

If I’ve written a column in a newspaper that they [readers] just axiomatically hate, it’s a bit of a non-starter, bit dead in the water.

Ben Heard (P11)

I think it’s convenient for conservatives … to create a distraction from their own problems over climate policy.

Bob Carr (N3)

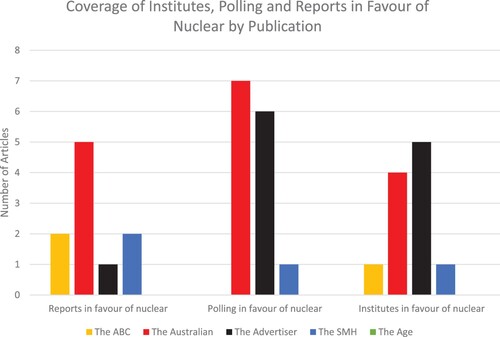

Coverage of nuclear energy’s inclusion in degree pathwaysFootnote2 in the IPCC’s Special Report in 2018 (Global Warming of 1.5°) was only present in right-wing media. Right-wing outlets published content relating to pro-nuclear environmentalism and research, such as by the Energy Policy Institute and Institute of Public Affairs, whilst also favourably publishing various polling and reports that suggest nuclear support is increasing ().

A general trend of increased media representation around the times of significant events, such as the various government inquiries and announcement of the AUKUS deal, was led largely by the chosen right-wing media outlets, with the exception of the release of findings related to the Federal and NSW inquiries which saw The SMH dominating. Notably, during times outside of significant events right-wing publications continued to publish articles about nuclear energy.

Participants bolstered this finding, noting the stimulating nature of the AUKUS submarine deal and the state and federal inquiries into nuclear energy.

[AUKUS] was very important in kicking off the current debate.

Tyrone D’Lisle (P4)

Analysis

Major themes generated from the newspaper analysis and interviews were the dominance of right-wing media and politics in the nuclear energy debate and their explicit promotion of nuclear power; fluctuations in media reporting and the prominence of climate change and energy security to keeping nuclear energy salient; the adversarial characterisations of both sides of the debate; and a struggle over the state of the debate by stakeholders in Australia. This section uses these themes to answer the three research questions.

Contexts that stimulate and stifle

In contrast to McGaurr and Lester (Citation2009), the framing of nuclear energy around climate change was prevalent throughout the entire study period, exemplifying its significance in maintaining nuclear energy media salience. The use of energy security and climate change frames aligns with framing in several international studies (Doyle Citation2011; Rogers-Hayden, Hatton, and Lorenzoni Citation2011), and illuminates the reuse of similar frames from the 1970s (Gamson and Modigliani Citation1989). The role of AUKUS in generating media salience asserted by Nuclear Engineering International (Citation2022) was similarly confirmed, in addition to media salience generated by various nuclear inquiries.

The prominence of events in sparking media attention and debate on nuclear energy illustrates the relevance of specific social contexts, Fairclough’s discourse-as-social-practice, to the nuclear energy debate in Australia. The dominance of right-wing media during time periods outside of these signifies an attempt to maintain media salience and suggests a promotional intent by right-wing actors.

Overall, the recent nuclear energy debate has been provoked by concerns about climate change, energy security, the occurrence of various political inquiries into nuclear technology, and the AUKUS announcement, whilst discussion has been limited by Australia’s prohibition. These factors highlight the introduction of contexts experienced internationally into the Australian discussion. Nevertheless, unique factors continue to play a role in stimulating and stifling debate in Australia.

Social actors: discursive techniques and their impacts

In addition to representing a majority of media coverage on nuclear energy in the given time period, as found by McGaurr and Lester (Citation2009), the chosen right-wing media largely accessed pro-nuclear voices in their opinion pieces and readers’ letters. Interview participants remarked on the pervasiveness of right-wing News Corporation in media debate and their promotional intent. These findings align with those of Yun (Citation2012) and Mercado-Sáez, Marco-Crespo, and Álvarez-Villa (Citation2019). The resulting partisan media landscape is speculated by interviewees to generate politicisation and further polarisation and is possibly a deliberate tactic to generate media salience (Kenis and Barratt Citation2022). The lack of reporting on nuclear energy in more progressive papers, where there is no appetite to open a debate about an issue that is currently banned because they favour renewable energy options, exacerbates this partisan media landscape.

Participants engaged in nuclear advocacy noted the ability for advocacy in right-wing media to be easily dismissed by ideologically opposed citizens, highlighting the negative implications associated with those who produce and circulate this discourse (Fairclough Citation1992).

With regards to overall differences in nuclear energy media coverage, right-wing media promoted pro-nuclear research, polling, and voices, whilst more progressive papers published reporting on previous nuclear accidents, Indigenous issues and provided a greater balance in opinion writing. These results align with Doyle (Citation2011).

Australian right-wing politicians also represent a majority of political proponent voices, similar to international studies (Balkan-Sahin Citation2019; Sarlós Citation2015; Yun Citation2012). This factor compounds the politicisation of the debate and frustrates proponents of nuclear energy who argue it generates the conditions for the topic to be discredited.

Nuclear energy framing and its implications

The framing of nuclear energy in Australia by media and stakeholders exacerbates a politicised and polarised discussion.

Proponents of nuclear, including interviewees and the right-wing press, positively attributed the development of SMRs and fourth generation technology, noting their role as the future of commercial nuclear power generation. Additionally, stakeholders from both sides noted the prevalence of energy security discourses in pro-nuclear arguments whilst right-wing outlets endorsed nuclear energy as a solution to energy shortages and rising electricity prices, similarly to Rogers-Hayden, Hatton, and Lorenzoni (Citation2011). These findings corroborate with the discourses presented by McCalman (Citation2019) and McCalman and Connelly (Citation2019), specifically energy security and abstract faith in science discourses. This abstract faith in science discourse is similarly described by McGaurr and Lester (Citation2009), illustrating their continued use in Australian right-wing media.

Doyle (Citation2011) finds that right-wing media in the UK utilise industry voices to frame nuclear energy through a neoliberal lens, similar to the findings of Yun (Citation2012), Mercado-Sáez, Marco-Crespo, and Álvarez-Villa (Citation2019) and Balkan-Sahin (Citation2019), and delegitimise environmentalists and concerns about climate change (see also McGaurr and Lester (Citation2009)). This mirrors Australian right-wing media citing pro-nuclear opinion pieces from industry and business groups such as the Minerals Council of Australia and utilising climate denialist rhetoric to argue a pro-nuclear case. Furthermore, anti-nuclear/environmentalist stakeholders are negatively framed through the use of derogatory terms.

Right-wing newspaper framing around the necessity for a rational debate on nuclear energy aligns with the debate we have to have and cool heads/hot heads discourses formulated by McGaurr and Lester (Citation2009). Proponents of nuclear energy utilised religious wording to describe and criticise anti-nuclear/pro-renewables stakeholders, similarly to Summers et al.’s (Citation2019) findings and McCalman’s (Citation2019) connection of environmentalism to religious concepts. These criticisms point to the irrationality of anti-nuclear stakeholders, exemplifying their ‘hot heads’ in comparison to the rationality or ‘cool heads’ of pro-nuclear stakeholders.

Framing pro-nuclear environmentalists as ‘rational’ or ‘enlightened’, as Pinker (Citation2021) does, and as identified by Summers et al. (Citation2019) and McCalman and Connelly’s (Citation2019) scientific rationality discourse, was mirrored by select proponents, exposing the characterisations associated with identifying as a pro-nuclear environmentalist. Conversely, opponents’ framing of proponent environmentalists as ‘dividing’ the environmentalist movement and disrupting the renewables transition indicates an entirely reversed characterisation.

The framing of nuclear energy in opposition to renewable energy was distributed across all publications, differing from the siloed use of renewables as nuclear rebuttal in left leaning publications in the UK (Doyle Citation2011). Arguing nuclear energy is a distraction was utilised by opponents and represented at a higher proportion in The SMH, a centre-left leaning outlet (), aligning with its use in a UK left paper (Doyle Citation2011). Similar criticism is acknowledged by proponent and opponent stakeholders in arguing nuclear energy is a political wedge, corroborating the findings presented by McGaurr and Lester (Citation2009).

Overall select discourses found in other studies are used in the Australian context, specifically energy security, faith in science, scientific rationality, debate we have to have and cool heads/hot heads. These discourses rationalise nuclear energy given energy security concerns and future technology development, frame the debate as necessary and characterise pro-nuclear environmentalists as rational and therefore superior to anti-nuclear stakeholders. This study identifies the use of new discourses including pro-nuclear environmentalists divide, renewables vs nuclear, and nuclear distraction/wedge. Many of these discourses act to compare and scrutinise, whether that be debate stakeholders or energy sources. In addition to the partisan media treatment, this nuclear energy framing contributes to the polarising and politicised nature of the debate.

Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to understand how nuclear energy is framed in Australian media and by stakeholders, how this potentially constrains the energy source, and explore the influence of climate change on the debate. To achieve this aim, the study deployed three research questions to interrogate the three-tiers of discourse present in this debate, namely discourse-as-text, discourse-as-discourse-practice, and discourse-as-social-practice (Fairclough Citation1992)

With regards to social practice, the role of climate change, nuclear inquiries and the announcement of AUKUS within the Australian context have been to stimulate debate and sustain its relevance. Concerns of energy insecurity, originating from the necessity to transition to a low-carbon economy and perpetuated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, has similarly placed nuclear energy on the energy agenda as a possible solution. Australia’s nuclear energy prohibition currently plays a constraining role in considering the nuclear option.

With regards to discourse practice, Right-wing media and politicians dominate the nuclear media discussion and in doing so limit its appeal to politically non-conservative people, whilst their discursive techniques compound these effects. There is a deliberate promotion of nuclear energy by right-wing media through selective coverage of pro-nuclear voices. The resulting impact of this partisan treatment is speculated as increasing polarisation and politicisation of the debate.

With regards to text, nuclear energy framing in media and by stakeholders is characterised as divisive and adversarial, constraining the capacity for middle-ground discussions. Some discourse frames found in previous studies align with the research findings of this study, while additional frames identified here include pro-nuclear environmentalists divide, renewables vs nuclear, and nuclear distraction/wedge. This framing compounds the effects of the partisan media treatment in perpetuating the polarised debate and therefore constraining it.

CDA was a useful analytical method to reveal discursive manipulations beyond texts and this study was the first to deploy this methodology on this particular topic. The importance of who dominates the nuclear energy debate and their discursive techniques cannot be understated. Therefore, the application of CDA and its analysis of the three tiers of discourse exposing the multiple layers of influence shaping the debate were essential. This study’s use of a longer time period, as opposed to research time periods premised on critical discourse moments (Kristiansen Citation2017), highlighted the dominance of right-wing media and their potential intent.

In assessing the three tiers of discourse analysed in the research questions, a considerably skewed and divided discourse arena emerged with right-wing media and politicians overwhelmingly dominating the discussion, but the discussion being limited in appeal to politically left leaning constituents and people identifying as pragmatically neutral in the debate. More work needs to be done to provide accurate and impartial media coverage so that nuclear energy can be judged based on scientific evidence, to decide whether the energy source has a place in Australia’s energy future.

Climate change and energy security concerns are helping to maintain media salience of nuclear energy and to re-frame the debate. As Australia transitions to a de-carbonised future, this research is a timely contribution to understanding the factors which shape public understandings of this low-carbon energy source and the advantages of utilising a CDA methodology to investigate media coverage of controversial issues.

Acknowledgement

The Authors would like to acknowledge and thank the two reviewers for their helpful and constructive feedback on an earlier version of this article. We would also like to thank the Editor for their support and encouragement through the submission process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The ABC’s digital print media is included, recognising that the national broadcaster is multi-platform and not traditionally a newspaper.

2 Degree pathways are hypothetical global warming scenarios that the IPCC uses to describe possible climate futures.

3 4 week unique audience for digital news, 2019 – 2020 (Australian Government Citation2020).

4 This sentence does not need a separate line. Can it please be moved as the last sentence in the above paragraph.

References

- Abdulla, A., A. A. Khourdajie, M. Babiker, Q. Bai, I. Bashmakov, C. Bataille, G. Berndes, et al. 2022. “Technical Summary.” In Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Working Group III Contribution to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), edited by A. Jäger-Waldau, and T. Sapkota, 1–133. Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg3/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_FinalDraft_TechnicalSummary.pdf.

- Arlt, D., A. Rauchfleisch, and M. S. Schäfer. 2019. “Between Fragmentation and Dialogue. Twitter Communities and Political Debate About the Swiss “Nuclear Withdrawal Initiative”.” Environmental Communication 13 (4): 440–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1430600.

- Australian Government. 2020. Australian Broadcasting Corporation Annual Report 2019-2020. Australian Government. Retrieved 06/09/2022 from https://www.transparency.gov.au/annual-reports/australian-broadcasting-corporation/reporting-year/2019-20-60.

- Balkan-Sahin, S. 2019. “Nuclear Energy as a Hegemonic Discourse in Turkey.” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 21 (4): 443–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2018.1506282.

- Berg, L. D. 2009. “Discourse Analysis.” In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, edited by R. Kitchin, and N. Thrift, 215–221. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Bickerstaff, K., I. Lorenzoni, N. F. Pidgeon, W. Poortinga, and P. Simmons. 2008. “Reframing Nuclear Power in the UK Energy Debate: Nuclear Power, Climate Change Mitigation and Radioactive Waste.” Public Understanding of Science (Bristol, England) 17 (2): 145–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662506066719.

- Bird, D. K., K. Haynes, R. van den Honert, J. McAneney, and W. Poortinga. 2014. “Nuclear Power in Australia: A Comparative Analysis of Public Opinion Regarding Climate Change and the Fukushima Disaster.” Energy Policy 65: 644–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.09.047.

- Blommaert, J., and C. Bulcaen. 2000. “Critical Discourse Analysis.” Annual Review of Anthropology 29 (1): 447–466. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.447.

- Borriello, A., P. Burke, and J. Rose. 2019. “Consumers’ Preferences for Different Energy Mixes in Australia.” International Choice Modelling Conference, Kobe, Japan.

- Boykoff, M. T. 2018. “Mass Media and Environmental Politics.” In The Politics of the Environment, edited by C. Okereke, 101–115. London: Routledge.

- Carvalho, A. 2008. “Media (Ted) Discourse and Society: Rethinking the Framework of Critical Discourse Analysis.” Journalism Studies (London, England) 9 (2): 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700701848162.

- Catalano, T., and L. R. Waugh. 2020. Critical Discourse Analysis, Critical Discourse Studies and Beyond. Cham: Springer.

- Cresswell, T. 2009. “Discourse.” In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, edited by R. Kitchin, and N. Thrift, 211–214. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Cronshaw, I. 2020. Australian Electricity Options: Nuclear. Parliament of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp2021/AustralianElectricityOptionsNuclear.

- Devitt, C., F. Brereton, S. Mooney, D. Conway, and E. O’Neill. 2019. “Nuclear Frames in the Irish Media: Implications for Conversations on Nuclear Power Generation in the age of Climate Change.” Progress in Nuclear Energy 110: 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2018.09.024.

- Doyle, J. 2011. “Acclimatizing Nuclear? Climate Change, Nuclear Power and the Reframing of Risk in the UK News Media.” International Communication Gazette 73 (1-2): 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048510386744.

- Eckermann, D. 2018. History of Australia’s Nuclear Prohibition - That day in December. Bright New World. https://www.brightnewworld.org/media/2018/10/18/history-of-australias-nuclear-prohibition-5ceab.

- Fairclough, N. 1992. Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Fairclough, N., J. Mulderrig, and R. Wodak. 2011. “Critical Discourse Analysis.” In Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, 2nd ed., edited by T. A. van Dijk, 357–378. London: Sage.

- Foucault, M. 1975. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

- Foucault, M. 1979. The History of Sexuality. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

- Foucault, M. 2003. Madness and Civilization. London: Routledge.

- Gamson, W. A., and A. Modigliani. 1989. “Media Discourse and Public Opinion on Nuclear Power: A Constructionist Approach.” American Journal of Sociology 95 (1): 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1086/229213.

- Harris, J., M. Hassall, G. Muriuki, C. Warnaar-Notschaele, E. McFarland, and P. Ashworth. 2018. “The Demographics of Nuclear Power: Comparing Nuclear Experts’, Scientists’ and Non-Science Professionals’ Views of Risks, Benefits and Values.” Energy Research & Social Science 46: 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.05.035.

- Hibbs, M. 2018. The Future of Nuclear Power in China. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/433874/the-future-of-nuclear-power-in-china/1404928/.

- International Atomic Energy Agency. 2023. IAEA Power Reactor Information System https://pris.iaea.org/pris/.

- IPCC. 2023. “Summary for Policymakers.” In Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Core Writing Team, edited by H. Lee, and J. Romero, 1–34. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.

- Irwin, A., S. Allan, and I. Welsh. 2000. The Risk Society and Beyond: Critical Issues for Social Theory. London: Sage.

- Kay, P. 2022. Australia’s Uranium Mines: Past and Present. Parliament of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Former_Committees/uranium/report/c07.

- Kenis, A., and B. Barratt. 2022. “The Role of the Media in Staging air Pollution: The Controversy on Extreme air Pollution Along Oxford Street and Other Debates on Poor air Quality in London.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 611–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420981607.

- Kepplinger, H. M., and R. Lemke. 2016. “Instrumentalizing Fukushima: Comparing Media Coverage of Fukushima in Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland.” Political Communication 33 (3): 351–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1022240.

- Kinsella, W. J. 2005. “One Hundred Years of Nuclear Discourse: Four Master Themes and Their Implications for Environmental Communication.” In The Environmental Communication Yearbook, edited by S. L. Senecah, 1 ed., 49–72. London: Routledge.

- Kirchhof, A. M., and J.-H. Meyer. 2014. “Global Protest Against Nuclear Power. Transfer and Transnational Exchange in the 1970s and 1980s.” Historical Social Research (Köln) 3 (1): 165–190. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.39.2014.1.165-190.

- Kratochvíl, P., and M. Mišík. 2020. “Bad External Actors and Good Nuclear Energy: Media Discourse on Energy Supplies in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.” Energy Policy 136: Article 111058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111058.

- Kristiansen, S. 2017. “Characteristics of the Mass Media’s Coverage of Nuclear Energy and its Risk: A Literature Review.” Sociology Compass 11 (7): Article e12490. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12490.

- Lowe, D. 2021. “Atomic Testing in Australia: Memories, Mobilizations and Mistrust.” In Remembering Social Movements: Activism and Memory, edited by S. Berger, S. Scalmer, and C. Wicke, 95–112. London: Routledge.

- Malatesta, T. 2021. “The Environmental, Economic, and Social Performance of Nuclear Technology in Australia.” Journal of Nuclear Engineering and Radiation Science 7 (4): Article 041202. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4049758.

- McCalman, C. 2019. “Nuclear Heresy: Environmentalism as Implicit Religion.” (Publication Number uk.bl.Ethos.767296) (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Sheffield. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/22794/.

- McCalman, C., and S. Connelly. 2019. “Destabilizing Environmentalism: Epiphanal Change and the Emergence of pro-Nuclear Environmentalism.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (5): 549–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1119675.

- McCausland, S. 2001. “Voices of Opposition: Documenting Australian Protest Movements.” Archives and Manuscripts 29 (2): 48–63. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.206263861653015.

- McGaurr, L. C., and E. Lester. 2009. “Complementary Problems, Competing Risks: Climate Change, Nuclear Energy and the Australian.” In Climate Change and the Media, edited by T. Boyce, and J. Lewis, 174–185. New York: Peter Lang.

- McManus, P. 1996. “Contested Terrains: Politics, Stories and Discourses of Sustainability.” Environmental Politics 5 (1): 48–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644019608414247.

- Mercado-Sáez, M.-T., E. Marco-Crespo, and À Álvarez-Villa. 2019. “Exploring News Frames, Sources and Editorial Lines on Newspaper Coverage of Nuclear Energy in Spain.” Environmental Communication 13 (4): 546–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1435558.

- Murphy, K., and H. Daniel. 2021. Australia Nuclear Submarine Deal: Aukus Defence Pact with US and UK Means $90bn Contract with France Will be Scrapped. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/sep/16/australia-nuclear-submarine-deal-contract-france-scrapped-defence-pact-us-uk.

- National Cancer Benefits Center. 2022. History of Bikini Atoll. https://www.bikiniatoll.info/history-of-bikini-atoll/.

- Nolt, J. 2022. “Nuclear Power.” In The Routledge Companion to Environmental Ethics, edited by B. Hale, A. Light, and L. Lawhon, 338–348. New York: Routledge.

- Nuclear Engineering International. 2022. Australian Submarine Deal Sparks Debate About Nuclear Energy. https://www.neimagazine.com/news/newsaustralian-submarine-deal-sparks-debate-about-nuclear-energy-9156685.

- Ogilvie-White, T. 2015. “Australia’s Rocky Nuclear Past and Uncertain Future.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 71 (5): 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096340215599783.

- Osička, J., and F. Černoch. 2022. “European Energy Politics After Ukraine: The Road Ahead.” Energy Research & Social Science 91: Article 102757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2022.102757.

- Palmero, C. M. 2019. “Nuclearism: Media Discourse, Image-Schemata, and the Cold war.” Critical Approaches to Discourse Analysis Across Disciplines 11 (2): 145–168.

- Pepper, D. 1984. The Roots of Modern Environmentalism. London: Routledge.

- Pinker, S. 2021. “Enlightenment Environmentalism: A Humanistic Response to Climate Change.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 33 (2): 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/jacf.12455.

- Pioro, I., R. Duffey, P. Kirillov, and N. Dort-Goltz. 2020. “Current Status of Reactors Deployment and Small Modular Reactors Development in the World.” Journal of Nuclear Engineering and Radiation Science 6 (4), https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4047927.

- Renzi, B. G., M. Cotton, G. Napolitano, and R. Barkemeyer. 2017. “Rebirth, Devastation and Sickness: Analyzing the Role of Metaphor in Media Discourses of Nuclear Power.” Environmental Communication 11 (5): 624–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2016.1157506.

- Reynolds, C. 2019. “Building Theory from Media Ideology: Coding for Power in Journalistic Discourse.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 43 (1): 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859918774797.

- Rogers-Hayden, T., F. Hatton, and I. Lorenzoni. 2011. “‘Energy Security’ and ‘Climate Change’: Constructing UK Energy Discursive Realities.” Global Environmental Change 21 (1): 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.09.003.

- Roser, M., H. Ritchie, and P. Rosado. 2022. Nuclear Energy. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/nuclear-energy.

- Roy Morgan Research. 2022. Australian Newspaper Readership. Think News Brands. https://www.roymorgan.com/findings/total-news-readership-continues-to-grow-up-0-9-per-cent-for-the-12-months-to-march-2022.

- Sarlós, G. 2015. “Risk Perception and Political Alienism: Political Discourse on the Future of Nuclear Energy in Hungary.” Central European Journal of Communication 8 (14): 93–111.

- Shaw, T. 2013. ““Rotten to the core”: Exposing America’s energy-media complex in The China Syndrome.” Cinema Journal 52 (2): 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2013.0011.

- Shellenberger, M. 2020. Apocalypse Never: Why Environmental Alarmism Hurts us all. New York: HarperCollins.

- Summers, I., A. Agee, M. R. Scott, and D. Endres. 2019. “The Discursive Construction of the Anti-Nuclear Activist.” In Networking Argument, edited by C. Winkler, 114–121. London: Routledge.

- Turner, L. 2020. “Techno-economic Assessment of the Australian co-Generation Opportunity Utilising Next Generation Nuclear Technology.” (Honours Thesis). University of Queensland. UQ eSpace. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:ca6cd8e.

- U.S. Department of Energy. 2022. The History of Nuclear Energy. Washington D.C. Retrieved from https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/The%20History%20of%20Nuclear%20Energy_0.pdf.

- van Dijk, T. A. 2013. News as Discourse. 1 ed. New York: Routledge.

- Van Munster, R., and C. Sylvest. 2015. “Pro-nuclear Environmentalism: Should we Learn to Stop Worrying and Love Nuclear Energy?” Technology and Culture 56 (4): 789–811. https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.2015.0107.

- Vossen, M. 2020. “Nuclear Energy in the Context of Climate Change: A Frame Analysis of the Dutch Print Media.” Journalism Studies 21 (10): 1439–1458. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2020.1760730.

- Vujić, J., R. M. Bergmann, R. Škoda, and M. Miletić. 2012. “Small Modular Reactors: Simpler, Safer, Cheaper?” Energy 45 (1): 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2012.01.078.

- Wodak, R. 1999. “Critical Discourse Analysis at the End of the 20th Century.” Research on Language & Social Interaction 32 (1-2): 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.1999.9683622.

- World Nuclear Association. 2022a. Australia’s Uranium. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-a-f/australia.aspx.

- World Nuclear Association. 2022b. Australian Research Reactors and Synchrotron. https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-a-f/appendices/australian-research-reactors.aspx.

- World Nuclear Association. 2022c. Chernobyl Accident 1986. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/safety-and-security/safety-of-plants/chernobyl-accident.aspx.

- World Nuclear Association. 2022d. Fukushima Daiichi Accident https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/safety-and-security/safety-of-plants/fukushima-daiichi-accident.aspx.

- World Nuclear Association. 2022e. Three Mile Island Accident. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/safety-and-security/safety-of-plants/three-mile-island-accident.aspx.

- Yun, S.-J. 2012. “Nuclear Power for Climate Mitigation? Contesting Frames in Korean Newspapers.” Asia Europe Journal 10 (1): 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-012-0326-2.