Abstract

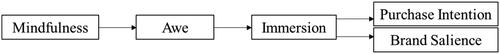

Mindfulness is gaining traction as an advertising tactic to boost audience engagement. Despite this, existing research provides limited insight into the impact of advertisements with integrated mindfulness elicitations, particularly regarding the mechanisms that might alter short-term memory retention. In the research, five studies examined how integrating elicitations of mindfulness, specifically through attention to the body, can be integrated into advertising. The studies explored how such integrated advertisements can manifest awe in consumers, thereby enhancing their immersion in the advertisement. Specifically, ads that incorporate mindful body cues (open body awareness, body scan, body senses, breath cues) versus a control condition absent of these cues enhance purchase intention and brand salience among viewers. This research practically introduces and defines mindfulness-integrated advertising to the field and theoretically illustrates the potential of mindfulness to influence information processing by elevating awe and immersion, and subsequently short-term memory, thereby boosting brand salience.

Mindfulness, the practice of focused attention, acceptance, and awareness of the present moment (Langer Citation1992; Kabat-Zinn Citation2015), is gaining traction in advertising. Brands are incorporating mindfulness into their campaigns through sensory experiences (e.g., KFC, see https://youtu.be/B5_xesq0-oY) and body cues such as breathing (e.g., Alberta Travel, see https://youtu.be/eke4s0erdgs), drawing consumer engagement (O’Leary Citation2016). However, the advertising field’s understanding of mindfulness-integrated advertisements and their impact on consumer information processing remains nascent. This understanding is crucial, especially since mindfulness positively influences consumer cognition (Errmann, Seo, and Septianto Citation2022).

Contemplative techniques, including reflective, spiritual, and imaginative methods, are becoming more prevalent in advertising, prompting a closer examination of their role (Waller and Casidy Citation2021; Septianto et al. Citation2021; Dodds, Jaud, and Melnyk Citation2021). The current research explores how the contemplative technique of mindfulness can enhance brand salience through consumer memory retention (Chiesa, Calati, and Serretti Citation2011). Brand salience is a measure of a brand’s visibility in a consumer’s memory across various contexts (Bergkvist and Taylor Citation2022; Romaniuk and Sharp Citation2004) and is key for advertising effectiveness (Rossiter and Percy Citation2017). Yet, brand salience tends to decline rapidly after ad exposure, with memory of brands dropping by 50% within a day of ad exposure (Nielsen Citation2017). This trend underscores the need for strategies that can enhance memory retention of brands in ads (Bergkvist and Taylor Citation2022). The current research suggests that mindfulness, by fostering awe and immersion, could help viewers’ memory.

This research aims to reveal how mindfulness enriches information processing and enhances advertising effectiveness. Studies demonstrate that mindfulness augments cognitive resources, fostering the ability to interpret information in novel ways and promote openness to new experiences (Orazi, Chen, and Chan Citation2019; Chan and Wang Citation2019; Errmann, Seo, and Septianto Citation2022). This mindful state is correlated with increased sense acuity and profound contemplation (Rojas-Gaviria and Canniford Citation2022), often leading to experiences of awe (Keltner and Haidt Citation2003), which deepens immersion, the sensation of being enveloped by an ad (Witmer and Singer Citation1998). Such immersion allows consumers to feel a greater presence with and awareness of the content (Kim et al. Citation2017), echoing characteristics central to mindfulness (Baer, Smith, and Allen Citation2004).

The research investigates how mindfulness techniques that focus on body awareness can amplify the impact of advertisements. Concentrating on body sensations not only liberates cognitive capacity but also increases environmental alertness (Orazi, Chen, and Chan Citation2019; Van Vugt Citation2015), which in turn can enhance attention to environmental elements (Chiesa, Calati, and Serretti Citation2011) such as a brand’s logo within an ad. The current research argues that mindfulness-integrated advertising invokes awe—a profound experience that intensifies sensory perceptions, body sensations, and visual engagement (Howell et al. Citation2011), fostering curiosity, observation, and openness (Errmann, Seo, and Septianto Citation2022). Shifts in mental schemas that evoke awe (Rudd, Vohs, and Aaker Citation2012) may result in a more immersive advertisement experience (Kim et al. Citation2017). Such contemplative consumer engagement underscores the transformative power of mindfulness in altering the reception of advertising content.

Five studies explore how mindfulness-elicitation techniques that involve attention to the body (open body awareness, body scan, body senses, breath cues) can elevate awe and immersion, thereby strengthening brand salience and purchase intentions. Study 1 demonstrates the impact of open body awareness on brand salience and purchase intent, mediated by immersion. Studies 2 (body scan) and 3 (body senses) explore the full conceptual model with the serial mediation of awe and immersion. Studies 4 and 5 (breath cues) generalize these effects across different advertising mediums, showcasing the broad applicability of mindfulness-integrated advertisements.

This research is pertinent to those interested in the cognitive processes behind brand awareness (Bergkvist and Taylor Citation2022), crafting mindful ads (O’Leary Citation2016), and consumers desiring content that encourages contemplation (Dodds, Jaud, and Melnyk Citation2021; Waller and Casidy Citation2021), contributing to advertising literature in three ways: first, it uncovers a distinct cognitive process where mindful body cues enhance ad memory, providing an innovative strategy to combat the quick decay of brand salience (Bergkvist and Taylor Citation2022); second, it expands our understanding of awe by showing how an internal body focus can alter perceptions of awe, broadening the concept beyond its traditional emotional scope (Septianto et al. Citation2021); and third, it contributes to knowledge of immersion by proposing that immersive viewing can be self-generated by an audience, offering additional knowledge to the belief that immersion is exclusively influenced by external media environments (Kim et al. Citation2017; Sung et al. Citation2022; Wang, Gohary, and Chan Citation2023). Insights from this study are crucial for advertisers, suggesting that integrating mindfulness into campaigns can significantly boost viewer engagement and improve short-term brand-memory retention.

Theoretical Development

Mindfulness: Integration into Advertising

Mindfulness, as focused attention on the body, is posited to augment cognitive functions (Chiesa, Calati, and Serretti Citation2011), which, in turn, can significantly modify how information is processed in ads. Mindfulness can heighten attentiveness to a broad range of stimuli, encourage purposeful awareness during tasks, and deter automatic reactions (Baer, Smith, and Allen Citation2004). These cognitive enhancements have two key implications for advertising: they can generate positive associations with brands, potentially influencing purchase intentions, and strengthen working memory, contributing to brand salience.

Mindfulness can evoke positive emotions (Lindsay et al. Citation2018), reducing negative cognitive reactions (Hill and Updegraff Citation2012) and increasing cognitive regulation capacity (Errmann, Seo, and Septianto Citation2022; Orazi, Chen, and Chan Citation2019). Positive emotional connections between viewers and advertised products (Glaser and Reisinger Citation2022), alongside the cognitive flexibility afforded by mindfulness (Moore and Malinowski Citation2009), may reframe an ad as a positive encounter.

Furthermore, enhanced cognitive resources through mindfulness (Ndubisi Citation2014) aid viewers in concentrating on cognitively demanding ads (Chang Citation2013), crucial for processing ad materials like texts or other visual aids (Mick Citation1992). Mindfulness that directs attention to body sensations can curb distractions and heighten alertness, bolstering short-term memory (Chiesa, Calati, and Serretti Citation2011) and executive function (Zeidan et al. Citation2010)—factors key to maintaining brand presence in immediate memory (Bergkvist and Taylor Citation2022).

While this cognitive shift may mirror other advertising frameworks, it has distinctive qualities. For instance, the central route of persuasion involves the thoughtful evaluation of arguments presented and demands significant cognitive processing, typically employed when the listener is motivated and able to engage with the subject matter (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986). However, the cognitive engagement demanded by mindfulness is markedly different, both in terms of its depth and nature and the expected influence on attitude changes toward the advertisement. Rather than requiring an active cognitive process, mindfulness adopts an observant and experiential approach, grounding the viewer’s attention on their body, mind, and the advertisement. This cognitive engagement leans on conscious awareness and observation rather than content evaluation (Langer Citation1992). While not primarily aiming to induce long-term attitude changes, it focuses on evoking transient states and enhancing short-term memory.

Integrating mindfulness elicitations that concentrate on body sensations, such as body awareness, body scans, and breath cues, into advertising may enhance the ad’s impact on purchase intentions and brand salience. This mindfulness-centered approach serves as a cognitive anchor, sharpening the viewer’s awareness and reducing mind-wandering (Van Vugt Citation2015), which in turn improves their immediate recall of the ad’s content (Chiesa, Calati, and Serretti Citation2011). Formally:

H1:

The integration of mindfulness-elicitation techniques (open body awareness, body scan, body senses, breath cues) into an advertisement will result in higher purchase intentions and increased brand salience when compared to an advertisement without these techniques (control).

Mindfulness and Immersion

Audience engagement in ads can arise through various mechanisms. Storytelling can embed products within narratives (Escalas Citation2004; Glaser and Reisinger Citation2022), thematic visuals can enhance content fluency for audiences (Germelmann et al. Citation2020; Chang Citation2013), and displays of skill can foster a flow experience (Martins et al. Citation2019). Central to audience engagement is the concept of immersion, defined as a distinct presence that attunes individuals to mediated experiences (Kim et al. Citation2017) and involves being enveloped by sensory information (Slater and Wilbur Citation1997). Immersion occurs when individuals are fully absorbed in the present-moment, a state that mindfulness-integrated advertisements can enhance. Highly immersive environments facilitate a sense of presence, increasing engagement with the advertisement (Kim et al. Citation2017).

Immersion profoundly affects cognitive processes like attention and imagery, leading to cognitive engagement (Wang, Gohary, and Chan Citation2023). It stimulates mental visualization of product interaction, often boosting purchase intent as viewers envisage the product’s benefits in their lives (Escalas Citation2007). Moreover, an immersive state can enhance viewer interaction with the advertisement, allowing for more profound observations about the products or brands, which also stimulates working memory related to the ad.

Mindfulness is pivotal in deepening immersion, centering mental attention on one’s body and surroundings, thus heightening alertness (Van Vugt Citation2015). This alertness leads to a perceived unity within the advertising environment (Wang, Gohary, and Chan Citation2023), strengthening the connection with the ad content and increasing purchase intent as the viewer becomes more involved with the showcased product or service (Escalas Citation2007). Thus, mindful attention in ads can make consumers more observant and engrossed in the ad stimuli, boosting immersion and ad effectiveness.

Immersion, defined by its deeply absorptive quality, is distinct from other forms of engagement, such as flow, fluency, or narrative transportation. It encompasses not just concentration but also the vividness of the experience, fostering a sense of engagement that transcends physical presence (Cowan and Ketron Citation2019; Lombard et al. Citation2015). In contrast, flow is characterized by deep involvement in skill-based activities, with a focus on imaginative resources that shift attention from the environment to the task at hand (Csikszentmihalyi and LeFevre Citation1989; Marty-Dugas and Smilek Citation2019). Immersion captivates consumers with the richness and intricacy of the depicted scenario, while flow channels attention toward the execution of an activity.

Narrative transportation, on the other hand, engrosses consumers through storytelling, drawing them into the narrative space rather than the immediate setting (Escalas Citation2004; Seo et al. Citation2018). It is defined by the process of becoming absorbed in the events as they unfold within a story (Seo et al. Citation2018), effectively transporting individuals into the story’s world, where they become participants rather than observers. Unlike immersion or flow, narrative transportation focuses less on the direct experience or specific task, concentrating more on the narrative’s development and outcome.

Mindfulness, emphasizing present-moment awareness and bodily consciousness, complements the immersive qualities of advertising, intensifying the audience’s engagement with sensory information and visual representations (Slater and Wilbur Citation1997), thereby boosting the effectiveness of the advertisement. Formally:

H2

Perceived immersion will mediate the relationship between mindfulness-elicitation techniques (open body awareness, body scan, body senses) integrated into an advertisement and its effectiveness (purchase intentions and brand salience), as compared to a control advertisement without these techniques.

Mindfulness, Awe, and Immersion

When consumers encounter awe, they become attuned to sensations of wonder and amazement, often in response to vastness or experiences that challenge their worldview (Keltner and Haidt Citation2003). Awe, a cognitive-conceptual emotion linked to transcendence (Pilgrim, Norris, and Hackathorn Citation2017), has unique influences on behavior and judgment in advertising contexts. It can prompt an abstract mindset, enhancing the allure of desirable and temporally distant products (Septianto et al. Citation2021) and can even affect perceptions of time, increasing consumer patience (Rudd, Vohs, and Aaker Citation2012).

Awe’s key cognitive role is its capacity to refresh mental schemas (Keltner and Haidt Citation2003), a process that can be activated by visuals of expansive landscapes, panoramic scenes, and beautiful settings (Septianto et al. Citation2021), as well as by powerful music (Pilgrim, Norris, and Hackathorn Citation2017) and spiritual experiences (Shiota, Keltner, and Mossman Citation2007). Mindfulness, which fosters acute awareness of the present, aids in this schema updating by encouraging an openness to new experiences (Errmann, Seo, and Septianto Citation2022). In enhancing consumer sensory engagement, mindfulness sets the stage for awe (Howell et al. Citation2011), with its focus on attention and awareness promoting deep contemplation (Brown and Ryan Citation2003). Mindfulness’s effect on cognitive functions, such as attentiveness to environmental stimuli (Baer, Smith, and Allen Citation2004), primes individuals for a stronger response to awe-inducing elements in advertisements.

This heightened state of awe can serve as a gateway to deep immersion in advertising (Kim et al. Citation2017). Awe draws on intense feelings of wonder (Griskevicius, Shiota, and Neufeld Citation2010), sparking cognitive processes that evoke curiosity and a desire to explore (Shiota, Keltner, and John Citation2006). This curiosity also reduces the need for immediate cognitive closure (Shiota, Keltner, and Mossman Citation2007), potentially deepening the immersive experience. Immersion, defined as a profound presence within mediated experiences (Kim et al. Citation2017) and a state of being surrounded by sensory information (Slater and Wilbur Citation1997), is likely intensified by awe as it heightens sensitivity to sensory inputs, fostering deeper engagement with advertisements. Awe, prompted by mindfulness, presents an expansive and profound experience beyond one’s usual context, necessitating deeper immersion to integrate and understand the ad content (Garland et al. Citation2015; Shiota, Keltner, and Mossman Citation2007).

Immersion, induced by awe, can influence purchase intent and brand salience. It allows for the ad’s message to be processed more deeply, possibly enhancing brand salience. Additionally, the immersive experience may intensify consumers’ emotional bonds with the product, thus elevating purchase likelihood. Hence, awe’s role in fostering immersion could be crucial in amplifying advertising effectiveness. Formally:

H3

Perceived awe (a) and subsequent immersion (b) will serially mediate the effect of mindfulness-elicitation techniques (body scan, body senses) in an advertisement on its effectiveness (purchase intentions and brand salience), compared to a control advertisement without these techniques.

Overview of Studies

The series of five experimental studies presented in this manuscript systematically investigate the influence of mindfulness-elicitation techniques (see ) on advertising effectiveness. In Study 1, the initial causal effects of mindfulness as elicited by open body awareness are examined. The same advertisement devoid of open body awareness serves as the control, allowing for a direct comparison of their impact on purchase intentions and brand salience (Hypothesis 1). This study also probes the role of perceived immersion as a mechanism underlying this relationship (Hypothesis 2).

Table 1. Mindfulness elicitations.

Study 2 continues this exploration, utilizing the same brand imagery as Study 1 but contrasting a travel-focused control advertisement with a mindful elicitation featuring a body scan technique. This comparison extends the investigation to include the serial mediation effects of awe and immersion on the efficacy of advertising (Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3).

Addressing the potential confounding effects of visual esthetics, Study 3 shifts the context to faster-paced scenes and introduces an unknown fictitious brand to assess effects on the full model (Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3). This study emphasizes the distinct elicitation technique of focusing on body senses to attribute any observed effects to the mindfulness elicitation rather than to visual esthetics.

Expanding the scope, Studies 4 and 5 assess the external validity of Hypothesis 1, applying mindfulness elicitation through breath cues in varied formats: a meditation video and a static print advertisement from existing brands. These studies further generalize the versatility of mindfulness elicitation across media formats and existing mindfulness campaigns.

Across the studies, real advertisements that incorporate mindfulness elicitations are employed. Various product types—outdoors, food, mental health, and transportation—are featured to assess the general applicability of the mindfulness elicitations integrated into advertisements. The placement of real and fictional brand logos is strategically varied within the advertisements to measure brand salience without the confound of placement effects. delineates the mindfulness elicitation techniques utilized in each study and the corresponding hypotheses tested. shows the full conceptual model. The research studies received ethics approval from the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee, under approval number 22/200. The approval confirms adherence to ethical guidelines for participant recruitment, informed consent, and data management, safeguarding the rights and welfare of all participants.

Study 1

Study 1 has three main goals. First, it aims to provide initial evidence supporting Hypotheses 1 and 2 by examining if ads with body-focused mindfulness cues can elevate purchase intentions and brand salience, with perceived immersion acting as a mediator. For this purpose, a baseline REI advertisement is compared with a modified version that includes meditation text to foster body awareness (Errmann, Seo, and Septianto Citation2022). The objective is to demonstrate that the impact of mindfulness in advertising stems from body-centered attention rather than visual cues like nature scenes or slow-paced footage. Lastly, the study assesses the effects on an actual brand by incorporating the brand logo at the end of the ad.

Method

In Study 1, 169 participants from the Dynata consumer panel (51% female, Mage = 37.89, SD = 12.51) completed the study for compensation. The study used a single-factor, two-level between-subjects design, contrasting a mindfulness advertisement (coded as 1) with a control (–1).

Participants were randomly assigned to watch an ad with the REI logo that appeared at the end; the mindful group additionally received open body awareness meditation instructions (Errmann, Seo, and Septianto Citation2022) integrated into the ad. The control group viewed the ad without these instructions (see the Supplemental Online Appendix for stimuli of this and all subsequent studies). Mindfulness was assessed using a 21-item state mindfulness scale (e.g., “I actively explored my experience in the moment”; all items used the same 7-point scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = .81; Tanay and Bernstein Citation2013; full scale and all proceeding scales can be found in the Supplemental Online Appendix), and a one-way ANOVA indicated higher mindfulness scores in the mindful condition (M = 4.28, SD = 1.14) compared to the control condition (M = 3.92, SD = 1.11), F(1, 168) = 4.45, p = .036, η2 = .026.

Perceived immersion was measured next with a scale from Kim et al. (Citation2017), consisting of four items on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = .92). Purchase intentions were then measured using four statements on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = .95), adapted from Evans et al. (Citation2017).

Demographic questions (age, ethnicity, gender, income, and education level) preceded inquiries about brand familiarity on a 7-point scale (1 = not familiar at all, 7 = very familiar), as a real brand was featured. Results revealed that participants had the same familiarity of REI in the mindful condition (M = 4.98, SD = 1.11) to that of the control condition (M = 4.79, SD = 1.12), F(1, 168) = 1.01, p = .702. Brand salience was assessed with an open-ended question about outdoor adventure brands by asking, “When you think of planning an outdoor adventure, what brands come to mind?” adapted from Bergkvist and Taylor (Citation2022) to measure brand salience when prompted by the category. This question was strategically placed at the survey’s end, after approximately three minutes had passed, to minimize the influence of immediate recall (Rossiter Citation2014). Responses that mentioned REI were coded as 1, while all other brands were coded as 0.

To establish measurement validity, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted with the items related to mindfulness (measured state mindfulness), immersion, and purchase intentions. These statistical reporting results can be found in the Supplemental Online Appendix for the current study and all proceeding studies.

Results and Discussion

The four immersion items were averaged such that higher scores indicated greater immersion. ANOVA results showed that participants perceived the mindful ad to be more immersive (M = 4.28, SD = 1.46) than the control ad (M = 3.64, SD = 1.50), F(1, 168) = 7.71, p = .006, η2 = .044. The four purchase intention items were averaged such that higher scores indicated greater purchase intentions. ANOVA results showed higher purchase intentions toward the brand in the mindful ad (M = 4.96, SD = 1.15) than the control ad (M = 4.29, SD = 1.16), F(1, 168) = 9.90, p = .002, η2 = .056.

For brand salience, a chi-squared test showed that the mindfulness ad conditions varied (χ2 [1] = 12.98, p < .001). A higher proportion of respondents in the mindful ad commented that the first brand that came to mind was REI (20/88 = 22.7%) rather than the control ad (3/81 = 3.7%).

A mediation analysis was conducted using PROCESS Model 4 with 10,000 bootstrap samples (Hayes Citation2017). The model examined the indirect effects of the mindfulness ad conditions (mindful = 1, control = −1) via perceived immersion on the ad effectiveness of purchase intentions and brand salience (separate analysis for each dependent variable). As expected, the indirect effects were significant for both purchase intentions (B = .189, SE = .070, 95% CI: .054 to .332) and brand salience (B = .171, SE = .077, 95% CI: .043 to .344).

The findings suggest that advertisements integrating the mindfulness-elicitation technique of open body awareness can improve ad effectiveness by increasing immersion, brand salience, and purchase intentions. Next, it is important to address the variation of text instructions within the ads and consider potential confounding variables, such as narrative transportation and flow, now that initial causality has been established. Additionally, examining alternative body-awareness mechanisms (such as body scan, body senses, breath cues) will strengthen the internal validity of the model and support the hypotheses further.

Study 2

Study 2 aims to achieve four objectives. First, it replicates the REI advertisement from Study 1, ensuring text length and word count are similar in both mindful and control conditions to eliminate text processing as an immersion factor. Second, it tests the mindfulness elicitation of a body scan (Van De Veer, Van Herpen, and Van Trijp Citation2016). Third, it examines narrative transportation and flow as potential confounding variables to verify their influence on brand salience and purchase intentions. Finally, it seeks to test the sequential mediation of awe and immersion on ad effectiveness as proposed in Hypothesis 3.

Method

In Study 2, 200 participants from the CloudResearch consumer panel (Litman, Robinson, and Abberbock Citation2017; 50.3% female, Mage = 35.64, SD = 13.42) completed the study for compensation. The study used a single-factor, two-level between-subjects design, contrasting a mindfulness advertisement (coded as 1) with a control (-1). Two participants were excluded due to failing an attention check, leaving 198 participants.

Participants were randomly assigned to either the mindful or control condition, both featuring the one-minute REI ad from Study 1. The mindful condition incorporated a body scan script (Errmann et al. Citation2021), while the control condition included text about travel experiences to match the video’s visuals. A one-way ANOVA using the 21-item state mindfulness scale (Tanay and Bernstein Citation2013; α = .77) indicated higher mindfulness in the mindful condition (M = 4.88, SD = 1.05) compared to the control condition (M = 4.35, SD = 1.14), F(1, 197) = 11.27, p < .001, η2 = .057.

Study 2 assessed perceived immersion (α = .80), awe (α = .94), and purchase intentions (α = .87). Awe was measured on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) using a three-item scale designed for message processing (Hinsch, Felix, and Rauschnabel Citation2020). To account for their possible influence, narrative transportation and flow were evaluated with three-item scales (Escalas Citation2004; Martins et al. Citation2019).

For narrative transportation (α = .85), participants rated how well they could visualize the events of the video, see themselves in the story, and their mental involvement in the story (7-point scale; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; Escalas Citation2004). Flow experience (α = .78) was measured by items assessing focus, desire to view other content, and enjoyment of the video task (7-point scale; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; Martins et al. Citation2019). After these assessments, participants responded to an attention check by selecting “2” out of a list of options, brand familiarity, and demographic queries. Results revealed that participants had the same familiarity of REI in the mindful condition (M = 3.99, SD = 1.15) to that of the control condition (M = 3.85, SD = 1.12), F(1, 197) = .87, p = .582. Finally, the study ended with the brand salience question from Study 1, which asked participants to recall outdoor adventure brands. Brand mentions were coded, with REI noted as 1 and all others as 0.

To further enhance validity, results of an analysis using the measured state mindfulness scale as the independent variable in the model are reported. Results show a consistent pattern with the manipulated mindfulness conditions and are shown in the Supplemental Online Appendix for the current study and all proceeding studies.

Results and Discussion

ANOVA results showed that participants perceived the mindful ad to be more awe inducing (M = 4.38, SD = 1.30) than the control ad (M = 3.94, SD = 1.26), F(1, 197) = 6.99, p = .020, η2 = .025. Next, an ANOVA revealed that participants perceived the mindful ad to be more immersive (M = 4.70, SD = 1.71) than the control ad (M = 4.16, SD = 1.58), F(1, 197) = 8.51, p = .004, η2 = .042. Further, results from an ANOVA revealed higher purchase intentions toward the brand in the mindful ad (M = 4.92, SD = 1.11) than the control ad (M = 4.52, SD = 1.18), F(1, 197) = 5.84, p = .017, η2 = .029.

For brand salience, a chi-square test showed that the mindfulness advertisement conditions varied (χ2 [1] = 13.90, p < .001). A higher proportion of respondents in the mindful ad commented that the first brand that came to mind was REI (47/99 = 47.4%) rather than the control ad (22/99 = 22.2%).

The control items of narrative transportation and flow were tested. Scores for the items were averaged, with higher scores denoting greater narrative transportation and flow. ANOVA results showed no significant difference between the mindful ad (M = 5.24, SD = 1.22) and the control ad (M = 5.11, SD = 1.28), F(1, 197) = .57, p = .450 in narrative transportation, and similarly for flow, participants perceived the mindful ad (M = 5.44, SD = 1.01) to be similar to that of the control ad (M = 5.37, SD = 1.12), F(1, 197) = .23, p = .627.

An ANCOVA, adjusting for narrative transportation and flow, found no significant effects on purchase intentions from these variables. There were nonsignificant effects of narrative transportation, F(1, 197) = 2.01, p = .294 and flow, F(1, 197) = 1.07, p = .300. However, results revealed higher purchase intentions toward the brand in the mindful ad (M = 4.88, SD = 1.19) than the control ad (M = 4.56, SD = 1.26), F(1, 197) = 6.24, p = .013, η2 = .035.

Finally, a serial mediation analysis was conducted using PROCESS Model 6 with 10,000 bootstrap samples (Hayes Citation2017). The analysis explored the indirect effects of the mindfulness ad conditions (mindful = 1, control = −1) as the independent variable, via perceived awe and immersion as the mediators, on purchase intentions and brand salience (separate analysis for each dependent variable). The indirect effects were significant for both purchase intentions (B = .037, SE = .018, 95% CI: .007 to .079) and brand salience (B = .124, SE = .059, 95% CI: .032 to .265; including the control items as covariates did not change the results; see full statistical results in Supplemental Online Appendix).

These results show support for Hypothesis 3, demonstrating the effectiveness of using a body scan as a mindfulness elicitation in the full conceptual model. They also clarify that immersion is not merely due to text engagement within the ad, thereby eliminating this confound. The lack of significant differences in narrative transportation and flow between the mindful and control ads suggests these elements are consistent across various ad types and not unique to mindfulness techniques. An intriguing question for the next study is whether body awareness can be induced through auditory cues rather than text, and if brand salience is maintained when a fictitious brand and logo are introduced in the advertisement.

Study 3

Study 3 expands on Study 2, testing different esthetics, product category, and mindfulness body elicitations to ensure broad applicability. It uses food visuals to rule out the possibility that, in the current research, mindfulness or awe is linked to nature imagery, as has been noted in previous studies (Hartmann, Apaolaza, and Eisend Citation2016; Rudd, Vohs, and Aaker Citation2012). The study applies mindfulness-integrated advertising to the food-service category, with the mindful ad featuring an adapted HelloFresh “mindful moments” ad focusing on body senses, contrasted with a control ad highlighting the pleasure of eating, ensuring both ads have a similar voice tone and esthetics. To isolate the effect of mindfulness from brand recognition, both conditions present a fictitious brand early on, assessing if brand salience remains high without brand familiarity (Bergkvist and Taylor Citation2022). Additionally, this study controls for mood, arousal, and valence—factors that may potentially impact the effect of awareness to body senses (Lin et al. Citation2016).

Method

In Study 3, 205 participants from the CloudResearch consumer panel (Litman, Robinson, and Abberbock Citation2017; 50% female, Mage = 40.52, SD = 14.21) completed the study for compensation. The study used a single-factor, two-level between-subjects design, contrasting a mindfulness advertisement (coded as 1) with a control (–1). Seven participants were excluded due to failing an attention check, leaving 198 participants.

Participants were randomly assigned to watch an ad with mindful voice cues to elicit attention to body senses (mindful condition) or an ad emphasizing the enjoyment of eating (control condition). Both 45-second ads shared visual styles and voice tones, with a fictitious “Meal Chef” logo replacing HelloFresh.

Using the state mindfulness scale from prior studies (α = .80), participants in the mindful condition exhibited higher mindfulness (M = 4.25, SD = 1.12) than those in the control ad (M = 3.89, SD = 1.23), F(1, 197) = 4.81, p = .029, η2 = .024. Measures of perceived immersion (α = .85), awe (α = .96), and purchase intentions (α = .88) followed. Participants also rated their mood (7-point scale; 1 = happy, 7 = unhappy; Toneatto and Nguyen Citation2007) and arousal (7-point scale; 1 = low, 7 = high; Di Muro and Murray Citation2012; Shapiro, MacInnis, and Park Citation2002). Next, participants answered the same attention-check question as Study 2, demographic questions, and the brand salience question, “When you think of meal-planning services, what brands come to mind?” adapted from Bergkvist and Taylor (Citation2022). Responses citing Meal Chef were coded as 1, all others as 0.

Results and Discussion

ANOVA results showed that participants perceived the mindful ad to be more awe inducing (M = 4.59, SD = 1.22) than the control ad (M = 3.09, SD = 1.38), F(1, 197) = 39.47, p < .001, η2 = .168. Next, ANOVA results showed that participants perceived the mindful ad to be more immersive (M = 4.44, SD = 1.73) than the control ad (M = 3.69, SD = 1.62), F(1, 197) = 16.39, p < .001, η2 = .077. Finally, ANOVA results showed higher purchase intentions toward the brand in the mindful ad (M = 4.74, SD = 1.15) than in the control ad (M = 4.21, SD = 1.19), F(1, 197) = 10.29, p = .002, η2 = .050.

For brand salience, a chi-squared test showed that the mindfulness ad conditions varied (χ2 [1] = 5.17, p = .016). A higher proportion of respondents in the mindful ad commented that the first brand that came to mind was Meal Chef (57/98 = 58.16%) rather than the control ad (42/100 = 42%).

Regarding the control items, ANOVA results indicated no significant differences in mood, arousal, or valence between the mindful and control ad conditions. Participants rated their mood as similarly positive for both the mindful ad (M = 2.74, SD = 1.45) and the control ad (M = 2.93, SD = 1.32), F(1, 197) = .86, p = .353. Arousal levels were also comparable between the mindful ad (M = 3.53, SD = 1.22) and control ad (M = 3.64, SD = 1.23), F(1, 197) = .39, p = .532. Additionally, the valence attributed to the mindful ad (M = 5.12, SD = 1.34) was similar to the control ad (M = 5.01, SD = 1.32), F(1, 197) = .35, p = .553.

An ANCOVA, adjusting for mood, arousal, and valence found no significant effects on purchase intentions from these variables. There were nonsignificant effects of mood, F(1, 197) = .84, p = .360, arousal, F(1, 197) = .54, p = .294, and valence, F(1, 197) = .20, p = .648. However, results revealed higher purchase intentions toward the brand in the mindful ad (M = 4.74, SD = 1.62) than in the control ad (M = 4.21, SD = 1.56), F(1, 197) = 10.23, p = .002, η2 = .062.

A serial mediation analysis was conducted using PROCESS Model 6 with 10,000 bootstrap samples (Hayes Citation2017). The serial mediation analysis explored the indirect effects of the mindfulness ad condition (mindful = 1, control = −1) as the independent variable, via awe and perceived immersion as the mediators, on purchase intentions and brand salience (separate analysis for each dependent variable). The indirect effects were significant for both purchase intentions (B = .055, SE = .023, 95% CI: .016 to .108) and brand salience (B = .089, SE = .040, 95% CI: .024 to .183; full statistical results in Supplemental Online Appendix).

These results further support Hypothesis 3 and the full conceptual model. The use of a fictitious brand demonstrates that brand salience is independent of brand recognition, supported by the logo’s early placement in the ads. Additionally, these findings show that the mindfulness effects are not reliant on natural imagery or slow-paced ads, emphasizing body-focused attention as the critical factor. Studies 4 and 5 will aim to generalize these effects by evaluating the model’s external validity across various product types, like meditation services and transit, in different ad formats.

Study 4

Study 4 seeks to enhance the generalizability of mindfulness-integrated advertisements’ impact on brand salience by using an authentic ad from the Calm app. It compares a breathing meditation (mindful condition) to a relaxation-themed video (control condition) to ascertain that the observed mindfulness effect is due to body cues, specifically breathing, rather than general relaxation themes. Additionally, the consistent display of the logo throughout both ad conditions serves to further scrutinize the influence on brand salience.

Method

In Study 4, 200 participants from the CloudResearch consumer panel (Litman, Robinson, and Abberbock Citation2017; 50% female, Mage = 40.45, SD = 14.51) completed the study for compensation. The study used a single-factor, two-level between-subjects design, contrasting a mindfulness advertisement (coded as 1) with a control (−1). No participants failed the attention check.

Participants were randomly placed into two groups. The mindful group watched a 30-second Calm ad featuring a breath meditation with the text, “breathe in, hold, breathe out,” while the control group saw a relaxation-themed version with the text, “relax, hold, no stress.” Both ads had the same visuals and sound, but only the mindful ad included breathing (body) cues. The Calm logo was visible throughout both versions. After viewing, participants completed the state mindfulness scale, revealing higher mindfulness in the mindful condition (M = 5.26, SD = 1.01) compared to the control condition (M = 4.01, SD = 1.05), F(1, 199) = 15.56, p < .001, η2 = .162.

Participants then rated their familiarity with Calm on a 7-point scale, with participants in the mindful condition showing a similar familiarity (M = 4.18, SD = 1.85) to participants in the control condition (M = 3.87, SD = 1.92), F(1, 199) = 1.33, p = .249. Demographics, the same attention check as prior studies, and brand salience, “When you think of some mindfulness brands, what brands come to mind?” were recorded. Mentions of Calm were coded as 1, other brands as 0.

Results and Discussion

For brand salience, a chi-squared test showed that the mindfulness ad conditions varied (χ2 [1] = 15.46, p < .001). A higher proportion of respondents in the mindful ad commented that the first brand that came to mind was Calm (49/100 = 49%) rather than the control ad (22/100 = 22%). Study 4 confirmed that mindful breath cues positively impact brand salience. Study 5 will investigate whether this effect is unique to video formats by testing its influence through a print advertisement.

Study 5

Study 5 has three goals: to examine if breath cues translate to print ads, to focus on a single body cue related to breath to isolate its influence, and to enhance ecological validity by analyzing a genuine mindfulness campaign from the New Orleans Transit Authority conducted in 2023.

Method

In Study 5, 200 participants from the CloudResearch consumer panel (Litman, Robinson, and Abberbock Citation2017; 50% female, Mage = 37.54, SD = 10.61) completed the study for compensation. The study used a single-factor, two-level between-subjects design, contrasting a mindfulness advertisement (coded as 1) with a control (–1). No participants failed the attention-check question.

In the mindful ad condition of the study, participants were shown a genuine mindfulness poster from the Regional Transit Authority featuring the text, “Pause, Breathe.” The control ad condition presented a modified version of this poster with the text, “Pause, Be Happy,” lacking any direct body cues. Both used the same visual design and displayed the RTA logo in the bottom right corner. ANOVA results indicated higher state mindfulness in the mindful condition (M = 4.01, SD = 1.46) compared to the control condition (M = 3.25, SD = 1.70), F(1, 199) = 23.37, p = .004, η2 = .086.

Brand familiarity was also assessed on a 7-point scale, with no significant difference in perceived familiarity between the mindful condition (M = 3.47, SD = .89) and control condition (M = 3.54, SD = .88), F(1, 199) = .05, p = .818. Participants then completed demographic queries and the same attention check from prior studies, and responded to a brand salience question related to transit services, “When you think of some transit service brands, what brands come to mind?”. Brand mentions were coded with RTA as 1 and other brands as 0.

Results and Discussion

For brand salience, a chi-squared test showed that the mindfulness ad conditions varied (χ2 [1] = 8.11, p = .004). A higher proportion of respondents in the mindful ad commented that the first brand that came to mind was RTA (regional transport authority) (21/100 = 21%) rather than the control ad (7/100 = 7%). Study 5 reinforces the effectiveness of incorporating body-cue elicitations into real-world advertising, even in static formats like print. The use of a single word, “breathe,” indicates that mindfulness can be elicited with minimal text cues, suggesting that a simple prompt to pause and focus on the body can influence consumer memory.

General Discussion

The present research establishes that integrating mindfulness, by directing attention to the body, into advertising amplifies awe and immersion, thereby boosting purchase intentions and brand salience. Various types of mindfulness cues (open body awareness, body scans, attention to senses, breath cues) were examined in ads for both real and fictitious brands, including existing mindfulness advertisements. The research introduces mindfulness as a construct that can enhance ad effectiveness by improving purchase intentions and brand salience (Studies 1–5; Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, the psychological mechanisms underpinning mindfulness-integrated advertising were explored, namely immersion (Studies 1–3; Hypothesis 2) and awe (Studies 2–3; Hypothesis 3), illuminating how they can enhance viewer engagement and contribute to a more engaging experience.

Theoretical Contributions

The research builds upon existing knowledge of awe and immersion and introduces the influence of mindfulness techniques on brand salience to counter memory decay. First and foremost, this research highlights information processing activated by viewers’ mental faculties (Van Vugt Citation2015), improving the immediate recall of an ad’s content (Chiesa, Calati, and Serretti Citation2011). Specifically, body cues rooted in mindfulness amplify the attention that viewers devote to an ad. Mindfulness helps augment concentration on ads (Chang Citation2013) and supports processing of ad content, such as text or other logos (Mick Citation1992). Mindfulness represents a cognitive combat to memory decay that has been associated with brand salience in advertising literature (Bergkvist and Taylor Citation2022), showcasing the pivotal role mindfulness can play in enhancing memory retention in advertising.

Second, while studies have examined how advertisements with visuals of natural spectacles or expansive landscapes can invoke awe (Septianto et al. Citation2021), this article posits a fresh viewpoint. It suggests that experiences that challenge one’s worldview (Keltner and Haidt Citation2003) or evoke a cognitive-conceptual emotion (Pilgrim, Norris, and Hackathorn Citation2017) can be provoked not merely through visuals of natural magnificence (Rudd, Vohs, and Aaker Citation2012) but also through alternative imagery like food. Awe, in this context, may be instigated through processing effects of mindfulness, such as contemplation (Rojas-Gaviria and Canniford Citation2022), rather than sheer environmental esthetics. Thus, mindfulness’s effect on cognitive functions (Baer, Smith, and Allen Citation2004) primes viewers to better pay attention to elements in advertisements that may induce awe. Further, although this study accounted for mood and valence, there wasn’t a distinct emotional variation in awe among viewers. Hence, this research doesn’t contradict the findings of researchers who explore awe (e.g., Septianto et al. Citation2021); it augments them, illustrating that viewer processing can modulate awe reactions, thereby enriching previous insights.

Finally, most research on immersion has focused on the idea that unique aspects of a consumer’s surroundings foster immersion—examples include virtual settings mimicking tangible interactions (Kim et al. Citation2017), visual platforms enveloping audiences (Wang, Gohary, and Chan Citation2023), or augmented reality altering spatial perceptions (Sung et al. Citation2022). Alternatively, the current study argues for a novel angle on immersion. Instead of the environment being the immersion antecedent (Kim et al. Citation2017), it tests four different forms of mindfulness body elicitations to showcase that consumers can internally initiate immersion, thereby enriching their viewing experiences without relying on external environmental triggers (Slater and Wilbur Citation1997). Mindfulness presents that looking inward to sensations and feelings may promote profound experiential immersion (Garland et al. Citation2015; Shiota, Keltner, and Mossman Citation2007) to advertising content.

Managerial Implications

In recent decades, the domain of advertising has been presented with challenges to administer attention-grabbing advertisements and construct effective brand awareness. High levels of clutter and increased advertising frequency have made it increasingly difficult for messages to stand out (Bergkvist and Taylor Citation2022). In this context, the concept of mindfulness holds important managerial implications. Incorporating mindfulness techniques into advertising can significantly boost viewer engagement, leading to increased brand salience. For example, an advertisement for a tea might begin by inviting viewers to take a deep breath and focus on the sensation of the air filling their lungs before showcasing the product. This approach harnesses the power of mindfulness by directing viewers’ attention to their own body experiences, then transitioning that heightened awareness to the product. By prioritizing these immersive experiences over traditional esthetic visuals or sound cues, advertisers may elicit more attention from audiences.

Mindfulness in advertising may allow consumers to become more attuned to their subjective experiences, fostering improved decision making aligned with their well-being (Kasser and Sheldon Citation2009; Howell et al. Citation2011). By evoking mindfulness, advertisements can heighten consumer self-awareness, helping them discern their reactions to the brand. Such increased awareness can guide more informed perceptions and attitudes toward the brand. Advertisers can harness this potential by creating content that is resonant, authentic, and reflective of consumers’ values. For example, a skincare brand promoting holistic wellness might incorporate guided visualizations of skin rejuvenation, inviting viewers to imagine and feel the benefits even before introducing the product. Further, owned media campaigns like Calm’s mindfulness initiatives serve as contemplative tools rather than mere distractions. Commercials fashioned as immersive experiences, reminiscent of meditation videos, can stimulate positive emotions and bolster the brand’s perceived authenticity and relevance (see Kemp Citation2019). However, although integrating mindfulness into advertising provides marketers with innovative avenues for crafting engaging campaigns, the novelty of mindfulness may decline as more advertisers use the approach.

Nevertheless, managers must tread cautiously due to the ethical implications inherent in such strategies. While the mechanism of body cues can be applied broadly across product categories, the integration of mindfulness—deeply rooted in ancient Eastern traditions—might not resonate with the core values of every brand. Brands like Lululemon, whose ethos revolves around well-being, contemplation, and reflection (as illustrated on lululemon.com), would naturally align with mindfulness-centric advertising. On the contrary, fast-fashion brands, which might prioritize rapid consumption and frequent trend shifts, may find themselves at odds with the introspective and contemplative philosophy of mindfulness. Thus, it becomes imperative for managers to consider not only the effectiveness but also the authenticity and ethical coherence of such marketing approaches.

Limitations and Future Research

Regarding the mindfulness elicitations, it is noteworthy that the REI advertisement, a real market ad used as a control ad in Study 1, did not induce a state of mindfulness. This implies that the ad, absent of body cues, does not induce mindfulness. The research suggests the advertisement would benefit from calling attention to body cues. Further, as each study aimed to test specific mindfulness cues, there are minor differences between the mindful and control elicitations, such as narration tone. Exploring different versions of elicitations was therefore important to mitigate any minor differences in the stimuli.

Regarding participants, the studies included experiments that randomly assigned participants into conditions for a payment, as is typical of research experiments. To ensure forced attention does not influence the results, two additional studies were conducted with participants having the option to “opt in” or “opt out” of viewing the mindful and control stimuli from Study 4 and Study 5. The pattern is the same as results reported in the manuscript and results can be found in the Supplemental Online Appendix. This helps reduce factors such as the novelty of the advertisements. However, it is noted that mindfulness cues may feel novel to consumers and that effects may decline if mindfulness advertisements are frequently used.

Regarding measures and reporting, although the current research utilized a measure of narrative transportation commonly employed in advertising (Escalas Citation2004), the scale did not encompass the dimension of emotion (Green and Brock Citation2000). Nonetheless, the current research validated that there was no difference in mood, valence, and arousal, thus addressing various aspects of affect. Finally, the average variance extracted of the perceived immersion construct in Study 2 is below the acceptable thresholds suggested by the literature (Diamantopoulos and Siguaw Citation2000). This result is reported in the Supplemental Online Appendix. All other constructs are above the threshold.

Regarding future research, practitioners and researchers might question whether advertisements could overly immerse viewers, causing them to focus more on self-related meditation than the advertisement itself. Previous studies suggest that a disconnect between an ad’s storyline and product negatively affects persuasion (Glaser and Reisinger Citation2022). In the current research context, an overly immersive meditation might distract viewers from the advertisement. While this study found that body scans did not overly distract the viewer, exploring when and how such disengagement might occur and how to mitigate it remains a strong area of interest.

Second, Study 4 incorporated an existing meditation advertisement from the Calm app, a brand intrinsically tied to mindfulness due to its product nature. However, it was crucial to test mindfulness ads associated with brands or product categories not explicitly linked to mindfulness, such as RTA, the fictitious brand Meal Chef, and REI. The mindfulness effect was consistent, unaffected by variations in visuals (food, nature, static images) or diverse products and brands. Future research could investigate potential incongruities between certain brands or visuals and the mindfulness effect. It is anticipated that the effects will persist as long as body cues are included, but congruency exploration could yield interesting insights.

Future research could investigate the well-being outcomes resulting from these advertisements. Mindfulness-integrated advertising might be considered a subset of transformative advertising, thus the potential of such advertising as a tool to enrich consumers’ lives merits exploration. A conceptual article could delineate the domains and subtleties of contemplative philosophies like mindfulness, minimalism, conscious consumption, and deceleration, and propose a transformative framework.

Finally, research could explore the long-term effects of integrating mindfulness into advertising strategies. As mindfulness becomes a habitual practice for consumers, it would be intriguing to investigate if they show heightened recall and engagement with brands that incorporate this philosophy. Does mindful alignment foster an enduring connection between consumers and brands, culminating in more sustainable relationships? By examining these aspects, research can shed light on the potential of mindfulness not just as a transient engagement tool but as a robust strategy to amplify lasting brand recognition and salience.

Supplemental Online Appendix

Download PDF (476.3 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amy Errmann

Amy Errmann (PhD, University of Auckland) is a Senior Lecturer, Department of Marketing, Auckland University of Technology.

References

- Baer, Ruth A., Gregory T. Smith, and Kristin B. Allen. 2004. “Assessment of Mindfulness by Self-Report: The Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills.” Assessment 11 (3): 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191104268029.

- Bergkvist, Lars, and Charles R. Taylor. 2022. “Reviving and Improving Brand Awareness as a Construct in Advertising Research.” Journal of Advertising 51 (3): 294–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2022.2039886.

- Brown, Kirk Warren, and Richard M. Ryan. 2003. “The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84 (4): 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

- Chan, Eugene Y., and Yitong Wang. 2019. “Mindfulness Changes Construal Level: An Experimental Investigation.” Journal of Experimental Psychology General 148 (9): 1656–1664.

- Chang, Chingching. 2013. “Imagery Fluency and Narrative Advertising Effects.” Journal of Advertising 42 (1): 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2012.749087.

- Chiesa, Alberto, Raffaella Calati, and Alessandro Serretti. 2011. “Does Mindfulness Training Improve Cognitive Abilities? A Systematic Review of Neuropsychological Findings.” Clinical Psychology Review 31 (3): 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.11.003.

- Cowan, Kirsten, and Seth Ketron. 2019. “Prioritizing Marketing Research in Virtual Reality: Development of an Immersion/Fantasy Typology.” European Journal of Marketing 53 (8): 1585–1611. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2017-0733.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, and Judith LeFevre. 1989. “Optimal Experience in Work and Leisure.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 56 (5): 815–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.5.815.

- Di Muro, Fabrizio, and Kyle B. Murray. 2012. “An Arousal Regulation Explanation of Mood Effects on Consumer Choice.” Journal of Consumer Research 39 (3): 574–584. https://doi.org/10.1086/664040.

- Diamantopoulos, Adamantios, and Judy A. Siguaw. 2000. Introducing Lisrel: A Guide for the Uninitiated. London: SAGE.

- Dodds, Sarah, David A. Jaud, and Valentyna Melnyk. 2021. “Enhancing Consumer Well-Being and Behavior with Spiritual and Fantasy Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 50 (4): 354–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1939203.

- Errmann, Amy, Jungkeun Kim, Daniel Chaein Lee, Yuri Seo, Jaeseok Lee, and Seongseop Sam Kim. 2021. “Mindfulness and Pro-Environmental Hotel Preference.” Annals of Tourism Research 90: 103263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103263.

- Errmann, Amy, Yuri Seo, and Felix Septianto. 2022. “‘Open to Give’: Mindfulness Improves Evaluations of Charity Appeals That Are Incongruent with the Consumer’s Political Ideology.” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research 7 (3): 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1086/719580.

- Escalas, Jennifer Edson. 2004. “Imagine Yourself in the Product : Mental Simulation, Narrative Transportation, and Persuasion.” Journal of Advertising 33 (2): 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2004.10639163.

- Escalas, Jennifer Edson. 2007. “Self-Referencing and Persuasion: Narrative Transportation Versus Analytical Elaboration.” Journal of Consumer Research 33 (4): 421–429. https://doi.org/10.1086/510216

- Evans, Nathaniel J., Joe Phua, Jay Lim, and Hyoyeun Jun. 2017. “Disclosing Instagram Influencer Advertising: The Effects of Disclosure Language on Advertising Recognition, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intent.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 17 (2): 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2017.1366885.

- Garland, Eric L., Norman A. Farb, Philippe R. Goldin, and Barbara L. Fredrickson. 2015. “Mindfulness Broadens Awareness and Builds Eudaimonic Meaning: A Process Model of Mindful Positive Emotion Regulation.” Psychological Inquiry 26 (4): 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294.

- Germelmann, Claas Christian, Jean Luc Herrmann, Mathieu Kacha, and Peter R. Darke. 2020. “Congruence and Incongruence in Thematic Advertisement–Medium Combinations: Role of Awareness, Fluency, and Persuasion Knowledge.” Journal of Advertising 49 (2): 141–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2020.1745110.

- Glaser, Matthias, and Heribert Reisinger. 2022. “Don’t Lose Your Product in Story Translation: How Product–Story Link in Narrative Advertisements Increases Persuasion.” Journal of Advertising 51 (2): 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1973623.

- Green, Melanie C., and Timothy C. Brock. 2000. “The Role of Transportation in the Persuasiveness of Public Narratives.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79 (5): 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701.

- Griskevicius, Vladas, Michelle N. Shiota, and Samantha L. Neufeld. 2010. “Influence of Different Positive Emotions on Persuasion Processing: A Functional Evolutionary Approach.” Emotion 10 (2): 190–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018421.

- Hartmann, Patrick, Vanessa Apaolaza, and Martin Eisend. 2016. “Nature Imagery in Non-Green Advertising: The Effects of Emotion, Autobiographical Memory, and Consumer’s Green Traits.” Journal of Advertising 45 (4): 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1190259.

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. London: Guilford Publications.

- Hill, Christina L. M., and John A. Updegraff. 2012. “Mindfulness and Its Relationship to Emotional Regulation.” Emotion 12 (1): 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026355.

- Hinsch, Chris, Reto Felix, and Philipp A. Rauschnabel. 2020. “Nostalgia Beats the Wow-Effect: Inspiration, Awe and Meaningful Associations in Augmented Reality Marketing.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 53 (May 2019): 101987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101987.

- Howell, Andrew J., Raelyne L. Dopko, Holli-Anne Passmore, and Karen Buro. 2011. “Nature Connectedness: Associations with Well-Being and Mindfulness.” Personality and Individual Differences 51 (2): 166–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.037.

- Jerath, Ravinder, Molly W. Crawford, Vernon A. Barnes, and Kyler Harden. 2015. “Self-Regulation of Breathing as a Primary Treatment for Anxiety.” Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 40 (2): 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-015-9279-8.

- Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 2015. “Mindfulness.” Mindfulness 6 (6): 1481–1483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0456-x.

- Kasser, Tim, and Kennon M. Sheldon. 2009. “Time Affluence as a Path toward Personal Happiness and Ethical Business Practice: Empirical Evidence from Four Studies.” Journal of Business Ethics 84 (S2): 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9696-1.

- Keltner, Dacher, and Jonathan Haidt. 2003. “Approaching Awe, a Moral, Spiritual, and Aesthetic Emotion.” Cognition & Emotion 17 (2): 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302297.

- Kemp, Madeleine. 2019. “Mindfulness in Marketing.” https://blog.dprandco.com/thinking/mindfulness-in-marketing

- Kim, Jooyoung, Sun Joo (Grace) Ahn, Eun Sook Kwon, and Leonard N. Reid. 2017. “TV Advertising Engagement as a State of Immersion and Presence.” Journal of Business Research 76: 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.001.

- Langer, Ellen J. 1992. “Matters of Mind: Mindfulness/Mindlessness in Perspective.” Consciousness and Cognition 1 (3): 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-8100(92)90066-J.

- Lin, Yanli, Megan E. Fisher, Sean M. M. Roberts, and Jason S. Moser. 2016. “Deconstructing the Emotion Regulatory Properties of Mindfulness: An Electrophysiological Investigation.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 10 (SEP2016): 451. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00451.

- Lindsay, Emily K., Brian Chin, Carol M. Greco, Shinzen Young, Kirk W. Brown, Aidan G. C. Wright, Joshua M. Smyth, Deanna Burkett, and J. David Creswell. 2018. “How Mindfulness Training Promotes Positive Emotions: Dismantling Acceptance Skills Training in Two Randomized Controlled Trials.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 115 (6): 944–973. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000134.

- Litman, Leib, Jonathan Robinson, and Tzvi Abberbock. 2017. “TurkPrime.Com: A Versatile Crowdsourcing Data Acquisition Platform for the Behavioral Sciences.” Behavior Research Methods 49 (2): 433–442. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0727-z.

- Lombard, Matthew, Frank Biocca, Jonathan Freeman, Wijnand IJsselsteijn, and Rachel J. Schaevitz. 2015. Immersed in Media: Telepresence Theory, Measurement & Technology. New York: Springer.

- Martins, José, Catarina Costa, Tiago Oliveira, Ramiro Gonçalves, and Frederico Branco. 2019. “How Smartphone Advertising Influences Consumers’ Purchase Intention.” Journal of Business Research 94 (December 2017): 378–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.047.

- Marty-Dugas, Jeremy, and Daniel Smilek. 2019. “Deep, Effortless Concentration: Re-Examining the Flow Concept and Exploring Relations with Inattention, Absorption, and Personality.” Psychological Research 83 (8): 1760–1777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-018-1031-6.

- Mick, David Glen. 1992. “Levels of Subjective Comprehension in Advertising Processing and Their Relations to Ad Perceptions, Attitudes, and Memory.” Journal of Consumer Research 18 (4): 411. https://doi.org/10.1086/209270.

- Moore, Adam, and Peter Malinowski. 2009. “Meditation, Mindfulness and Cognitive Flexibility.” Consciousness and Cognition 18 (1): 176–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2008.12.008.

- Ndubisi, Nelson Oly. 2014. “Consumer Mindfulness and Marketing Implications.” Psychology & Marketing 31 (4): 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20691.

- Nielsen. 2017. “Understanding Memory in Advertising.” https://www.nielsen.com/insights/2017/understanding-memory-in-advertising/

- O’Leary, Shane. 2016. “Trendwatching—Brands Using Mindfulness in Advertising.” https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/trendwatching-brands-using-mindfulness-advertising-shane-o-leary/

- Orazi, Davide C., Jiemiao Chen, and Eugene Y. Chan. 2019. “To Erect Temples to Virtue: Effects of State Mindfulness on Other-Focused Ethical Behaviors.” Journal of Business Ethics 169 (4): 785–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04296-4.

- Petty, Richard E., and John T. Cacioppo. 1986. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. New York: Springer.

- Pilgrim, Leanne, J. Ian Norris, and Jana Hackathorn. 2017. “Music Is Awesome: Influences of Emotion, Personality, and Preference on Experienced Awe.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 16 (5): 442–451. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1645.

- Rojas-Gaviria, Pilar, and Robin Canniford. 2022. “Poetic Meditation: (Re)Presenting the Mystery of the Field.” Journal of Marketing Management 38 (15-16): 1821–1831. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2022.2112611.

- Romaniuk, Jenni, and Byron Sharp. 2004. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Brand Salience.” Marketing Theory 4 (4): 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593104047643.

- Rossiter, John R. 2014. “Branding’ Explained: Defining and Measuring Brand Awareness and Brand Attitude.” Journal of Brand Management 21 (7-8): 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2014.33.

- Rossiter, John R., and Larry Percy. 2017. “Methodological Guidelines for Advertising Research.” Journal of Advertising 46 (1): 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1182088.

- Rudd, Melanie, Kathleen D. Vohs, and Jennifer Aaker. 2012. “Awe Expands People’s Perception of Time, Alters Decision Making, and Enhances Well-Being.” Psychological Science 23 (10): 1130–1136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612438731.

- Seo, Yuri, Xiaozhu Li, Yung Kyun Choi, and Sukki Yoon. 2018. “Narrative Transportation and Paratextual Features of Social Media in Viral Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 47 (1): 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1405752.

- Septianto, Felix, Yuri Seo, Loic Pengtao Li, and Linsong Shi. 2021. “Awe in Advertising: The Mediating Role of an Abstract Mindset.” Journal of Advertising 52 (1): 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1931578.

- Shapiro, Stewart, Deborah J. MacInnis, and C. Whan Park. 2002. “Understanding Program-Induced Mood Effects: Decoupling Arousal from Valence.” Journal of Advertising 31 (4): 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2002.10673682.

- Shiota, Michelle N., Dacher Keltner, and Amanda Mossman. 2007. “The Nature of Awe: Elicitors, Appraisals, and Effects on Self-Concept.” Cognition and Emotion 21 (5): 944–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600923668.

- Shiota, Michelle N., Dacher Keltner, and Oliver P. John. 2006. “Positive Emotion Dispositions Differentially Associated with Big Five Personality and Attachment Style.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 1 (2): 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760500510833.

- Siegel, Daniel. 2007. “Mindfulness Training and Neural Integration: Differentiation of Distinct Streams of Awareness and the Cultivation of Well-Being.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 2 (4): 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsm034.

- Slater, Mel, and Sylvia Wilbur. 1997. “A Framework for Immersive Virtual Environments (FIVE): Speculations on the Role of Presence in Virtual Environments.” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 6 (6): 603–616. https://doi.org/10.1162/pres.1997.6.6.603.

- Sung, Eunyoung, Dai-In Danny Han, and Yung Kyun Choi. 2022. “Augmented Reality Advertising via a Mobile App.” Psychology & Marketing 39 (3): 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21632

- Tanay, Galia, and Amit Bernstein. 2013. “State Mindfulness Scale (SMS): Development and Initial Validation.” Psychological Assessment 25 (4): 1286–1299. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034044.

- Toneatto, Tony, and Linda Nguyen. 2007. “Does Mindfulness Meditation Improve Anxiety and Mood Symptoms? A Review of the Controlled Research.” The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 52 (4): 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370705200409.

- Van De Veer, Evelien Van De, Erica Van Herpen, and Hans C. M. Van Trijp. 2016. “Body and Mind: Mindfulness Helps Consumers to Compensate for Prior Food Intake by Enhancing the Responsiveness to Physiological Cues.” Journal of Consumer Research 42 (5): 783–803. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucv058.

- Van Vugt, Marieke. 2015. “Cognitive Benefits of Mindfulness Meditation.” In Handbook of Mindfulness: Theory, Research, and Practice, edited by Kirk Warren Brown, J. David Creswell, Richard M. Ryan, 190–207. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Waller, David S., and Riza Casidy. 2021. “Religion, Spirituality, and Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 50 (4): 349–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1944936.

- Wang, Liangyan, Ali Gohary, and Eugene Y. Chan. 2023. “Are Concave Ads More Persuasive? The Role of Immersion.” Journal of Advertising 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2023.2216262.

- Witmer, Bob G., and Michael J. Singer. 1998. “Measuring Presence in Virtual Environments: A Presence Questionnaire.” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 7 (3): 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1162/105474698565686.

- Zeidan, Fadel, Susan K. Johnson, Bruce J. Diamond, Zhanna David, and Paula Goolkasian. 2010. “Mindfulness Meditation Improves Cognition: Evidence of Brief Mental Training.” Consciousness and Cognition 19 (2): 597–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014.