ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to compare the cultural-historical events and decisions regarding how to deal with the higher risks of HIV in MSM, and more specifically, gay populations in Sweden and the Netherlands. A narrative literature was used, based on 46 scientific articles and 20 additional semi-scientific resources. The themes of the arrival of HIV and AIDS, blood donations, offender/victim, the balance of risks with respect to the statistical probabilities and the human factor, and finally, prevention were discussed. It is concluded that certain context-specific historical events (the Dutch Bloody Sunday and the Swedish gay sauna ban) and culturally determined processes (trust in others in the Netherlands, and disapproval of casual sex in Sweden) have led to some important differences in how HIV and AIDS and the higher risks for gay men and MSM have been dealt with. In the Netherlands, there is a stronger protective attitude when it comes to the freedom and autonomy of MSM both when it comes to decisions about sexual behavior and to sharing any positive HIV status. In Sweden, on the other hand, there is a stronger tendency to enforce informing others of their HIV status. In both countries, despite efforts to prevent this, HIV has increased stigma for gay men and other MSM.

Introduction

When AIDS was discovered in the 1980s, the cause of the syndrome was initially not understood (Sharp & Hahn, Citation2011). Since AIDS was initially diagnosed in gay men, the link to homosexuality was made and the cause sought in the lifestyle of gay men (Kowalewski, Citation1988). Later, it became clear that AIDS is caused by a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that is primarily transmitted through unsafe sex and can also be transmitted through blood contact, such as through the use of shared hypodermic needles and blood transfusions (Barnett & Whiteside, Citation2002). With respect to transmission through sex, the risk is particularly high for unsafe anal sex, because rectal tissue is easily injured and the rectum is rich in immune cells that can become infected by HIV (Patel et al., Citation2014).

In the year 2021, we can fortunately conclude that we have come a long way in the fight against AIDS. There are drugs that, if used in time, allow the body to fight HIV so that it is only present in small quantities in the blood (Akshaya et al., Citation2021; Patel et al., Citation2021). The virus can even become undetectable, with chance of the virus spreading being effectively zero (Patel et al., Citation2021; Rodger et al., Citation2019). Moreover, pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) has been proven to be highly effective against the acquisition of HIV (preventive) (Jongen et al., Citation2021). PrEP can either be taken every day or a person can take two tablets 2–24 hours before a sexual encounter, followed by one tablet every 24 hours until 48 hours after the last sex act (event-driven) (Jongen et al., Citation2021). Although HIV is still more problematic in other countries, most Western European countries have successfully met the global 90–90-90 targets, with at least 90% of all PLHIV (People Living with HIV) diagnosed, at least 90% of people living with diagnosed HIV on treatment, and at least 90% of those on treatment virally suppressed (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Citation2020).

Nevertheless, a sterile cure is still very difficult at present and people living with HIV are often on permanent medication (Patel et al., Citation2021). In addition, the likelihood of symptoms is greater when someone discovers at a late stage that they are infected with HIV (Patel et al., Citation2021). For these reasons, prevention of the spread of the virus and early intervention in the event of infection are extremely important (World Health Organization, Citation2021). In Europe, men who have sex with men (MSM), the majority of whom identify themselves as gay (e.g., Boellstorff, Citation2011; Young & Meyer, Citation2005), are considered a major risk group due to the relatively higher prevalence of HIV and the elevated spread of HIV within this population (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Citation2020). However, this population generally already suffers from stigma, due to being a sexual minority group, and the discovery history of HIV and AIDS has also made HIV intertwined with stigma for gay men and other MSM (Purcell, Citation2021). As a result, there are psychological processes that make prevention difficult, such as that people might not disclose their positive HIV status out of fear for discrimination (Zimmermann et al., Citation2021). This makes the cultural-historical context relevant (Parry & Schalkwijk, Citation2020). Yet there are almost no studies to be found that examine this context. Understanding the interplay between culture and certain events in recent history may help to understand why certain policies and attitudes arose and thus what possibilities there are for improving preventive policies (Piot, Citation2006).

In this article, a narrative literature review is used to compare Sweden and the Netherlands. These countries are of interest when it comes to HIV prevention that focuses on MSM. With respect to HIV, Sweden was the first country in the world to achieve the UNAIDS/WHO 90–90-90 continuum (Gisslén et al., Citation2017) and the Netherlands has contributed significantly to medical developments to combat AIDS by advocating, propelled by clinical researcher Joep Lange, the combination therapy and showing its effects, even though combination therapy was initially thought to be irrational (Hankins, Wainberg, & Weiss, Citation2014; Van Doornum, Van Helvoort, & Sankaran, Citation2020). With respect to MSM and gay men specifically, and the LGBTQ+ community at large, both countries are characterized by a liberal climate with a long tradition of tolerance and acceptance of not only different sexual identities, but also of different religious, ideological and political positions. On the composite score of attitudes about homosexuality and gay rights, the Netherlands and Sweden score first and second place respectively (Smith, Son, & Kim, Citation2014). The large majority of both Dutch and Swedish citizens feel that homosexuality is a legitimate way of life (Van den Berg et al., Citation2014).

Both countries have participated in the sixth wave of the World Values Survey (Inglehart et al., Citation2014). This provides us with some insights into their respective cultural ethos, although it should be kept in mind that this reflects how people answered the survey back in 2011–2012. While democracy evidently is valued in both countries, a higher percentage of Swedish people (81.4%) than Dutch people (63.3%) rewarded the importance met a 9 or 10 score on a 10-point scale. With respect to religion, Christian denominations were the largest in both countries. The majority of the people in both countries feel respect for others as an important quality that children should learn at home (i.e., 86% of the Dutch and 87% of the Swedish). The survey also shows that people were somewhat more likely to think that others can be trusted in the Netherlands (66.1%) than in Sweden (60.1%). There was, however, a large difference in how the amount of free choice and control of people’s private lives were experienced, with 31.7% of the Swedish people giving a 9 or 10 rating on a 10-point scale, compared to only 7.4% of the Dutch.

The aim of this article is to compare the findings of these two countries in terms of their cultural-historical events and decisions regarding how to deal with the higher risks of HIV in MSM—and more specifically, gay populations. This will be done with the aim of understanding the current epidemiological situation and how it could be further improved. The information will provide perspectives that can help improve prevention policies (Zimmermann et al., Citation2021) as well as provide insights into ways to meet the recently set fourth “90” goal of improving the health-related quality of life for people living with HIV (Andersson et al., Citation2020).

Methods

A narrative review is an overview of previously published works with respect to a specific topic. It has a broader topic than a systematic review and can provide more insight into questions where not all contextual factors are known in advance, or the historical context is deemed relevant (Ferrari, Citation2015). A limitation of a narrative review, however, is that it is more difficult to reproduce, and the selection of the literature may be more subjective (Ferrari, Citation2015). For this reason, following Mason and Sultzman (Citation2019), it was decided to take a fairly systematic approach to searching the literature and reporting it.

In order to obtain a good overview of the literature, a search was conducted using a specific search string in PubMed, namely: ((AIDS or HIV) AND (gay or homo* or MSM) AND (stigma or social* or emotion* or psychologic*)) AND (Netherlands[Title] OR Dutch[Title] OR Sweden[Title] OR Swedish[Title])), and two somewhat broader search keys (MSM HIV Netherlands and MSM HIV Sweden) were used in Microsoft Academic. Additionally, articles were manually searched via backward and forward citations. Supplementary semi-scientific and official documents were also searched via Google and Google Scholar, as well as NGO websites in both countries and both majority languages (Dutch and Swedish). This way, we tried to also find any relevant publications that were published in the countries’ own languages, although it may be possible that some relevant papers were missed if they may not have been included in the online systems (especially papers that may have been published in national, printed Journals in the 1980s). The selection of articles is shown in the flow-chart in . Of the 82 publications found, 46 were ultimately found to provide relevant information for this review (). In addition, there were 20 semi-scientific sources used. The reason for inclusion was that the scientific literature often failed to describe relevant historical events and additional resources were necessary to provide more context. However, as the purpose was to describe the scientific findings, we did not include a direct policy document analysis, nor did we include a full analysis of how other historical events may have had a more indirect influence.

Table 1. Presentation of the scientific papers.

Please move to this location

Results

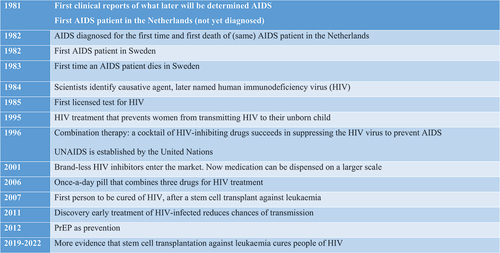

presents a historical timeline in order to give the reader a better understanding of when the events and changes described took place in relation to developments in understanding, treatment and prevention of HIV and AIDS.

Early 1980s: The arrival of HIV and AIDS

In the Netherlands, the first AIDS patient was admitted to a hospital in Amsterdam in November 1981. He was treated repeatedly, initially mainly for diarrhea, but by the spring of 1982 he had developed several very serious symptoms, including lung problems and a rare form of skin cancer, which were poorly understood (Mooij, Citation2004). A co-assistant who himself was gay and a member of the Gay Group Medicine as well as employee of the STD weekend clinic for gay men, was alarmed. He made the link with the disease recently discovered in the United States, especially when he heard that the patient was gay (Mooij, Citation2004). At that time, little was known about AIDS and the disease had only been diagnosed in gay men, which was why it as called “gay related immune deficiency” (Mooij, Citation2004). Upon inquiry, it turned out that the patient showed preference for sexual contacts with Americans, so “close to the hearth” and probably infected abroad (Mooij, Citation2004). Although he was not immediately taken seriously being a co-assistant, as history shows he turned out to be right. A few hours before the patient’s death, the diagnosis was made (Mooij, Citation2004). Only in the fall of the same year was the first patient diagnosed with AIDS in Sweden. By then, more was known about the symptoms of AIDS and the Swedish doctors recognized them in the (Norwegian) patient in question, who was gay and had visited the United States (Berner, Citation2011; Braekhus, Citation2020). He died in 1984, but another patient died of AIDS in Sweden earlier, in 1983.

The Dutch early reports on AIDS assumed that the virus would spread among “very [sexually] active homosexuals” but would not always be fatal (Koster, Citation2019). The early newspaper notifications in Sweden also showed some optimism, focusing more on the possible solutions that medicine would bring (Ljung, Citation2001). Yet, whereas in the Netherlands one was at least aware of the fact that AIDS would spread within the gay community, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare announced in 1983/1984 that the risk of an AIDS epidemic breaking out in Sweden had officially passed. This announcement was criticized and later had to be retracted (Ljung, Citation2001).

Blood donations

Not after long, it was discovered that blood donations were a risk for HIV/AIDS. There was particular danger for hemophiliacs who lack a clotting protein in their blood and depend on its administration for life (Mooij, Citation2004). This was because pools were used for this purpose, for which the blood of thousands of people was used (Mooij, Citation2004).

In the Netherlands, the link between AIDS and blood donations was made almost immediately. AIDS manifested itself in the Netherlands first and foremost in Amsterdam (Galesloot, Citation2007). In Amsterdam, there was a thriving homosexual nightlife in the late 1970s and early 1980s which had led to the spread of diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhea (Galesloot, Citation2007). Successful treatment was possible through the municipal health service, where the head of infectious diseases was researching a vaccine against hepatitis B. Moreover, many gay men donated blood because they were screened for syphilis and hepatitis B for free in the process (Mooij, Citation2004). As a result, there were already connections between the blood transfusion service, the municipal health services, and representatives of various gay federations and organizations.

The comparison between AIDS and hepatitis B was made and the first cases of AIDS among hemophilia patients in the United States provided sufficient reason for a meeting (Oosting, Citation1995). At the initiative of the Central Laboratory for Blood Transfusion Service, representatives of the blood bank organizations, the gay movement, the Dutch Association of Hemophilia, the Medical Inspectorate of Public Health, and of the municipal health services of Amsterdam and Rotterdam met on what was later called “Bloody Sunday”; specifically on 30th January 1983 (Dijstelbloem, Citation2014; Oosting, Citation1995). The blood banks saw AIDS as a medical problem and took the position that homosexual men should be excluded as blood donors. However, the input from the gay movement showed that the disease AIDS also clearly had a social dimension (Dijstelbloem, Citation2014; Oosting, Citation1995). In a manner common for the Netherlands, a lengthy discussion resulted in a compromise; an education campaign and voluntary withdrawal of blood donations by high-risk groups, including gay men (Oosting, Citation1995).

Although this process could also have fit well within Swedish culture, there was not yet such a network. Sweden had a decentralized, blood bank-based organization (Berner, Citation2011). Blood donation was a private decision without the strong moral connotation, that characterized it in the Netherlands and other European countries that had more recently experienced war (Berner, Citation2011). In Sweden, there was a small group of medical professionals in and around Stockholm, who since the early 1980s had met regularly to discuss what they considered to be a worrying health situation for gay men (Berner, Citation2011). This group established the Gay Men’s Health Clinic named “Venhälsan” (Vein Health) and communicated regularly with personnel at local hospitals, health authorities, and concerned epidemiologists at the National Bacteriological Laboratory (Berner, Citation2011). When the doctors at Venhälsan discovered a high frequency of potential pre-AIDS symptoms among their patients and found out that many of them were blood donors, they advised the major Swedish gay organization RFSL that gay men should refrain from donating blood. As history shows, RFSL chose to adopt this message and recommended that gay and bisexual men in Sweden refrained from donating blood (Ljung, Citation2001; Berner, Citation2011; Thorsén, Citation2013). Although RFSL was aware that this decision would risk stigmatizing the community at large, its executive board also felt it would be a disservice to deny the correlation and thus made the political decision and consideration that it should be made clear that gay men were doing everything they could to hinder the spread of AIDS in Sweden (Berner, Citation2011; Svéd, Citation2000). In fact, RFSL:s recommendation preceded that of the National Board of Health and Welfare, which hesitated for a long time before making such an announcement due to fear of public backlash (Berner, Citation2011; Thorsén, Citation2013).

In both countries it was decided over time that MSM (overall) were to be officially excluded from blood donations. In Sweden, this happened in 1985 due to the panic that arose among government agencies after a young boy suffering from hemophilia contracted HIV from a unit of blood plasma given to him at a Swedish hospital (Ljung, Citation2001). The Netherlands followed a few years later in 1988 driven by the statistics that demonstrated higher risks for donations from MSM (Oosting, Citation1995). Both countries chose to exclude MSM rather than gay men, specifically, to emphasize behavior rather than sexual identity and orientation. The consensus was that there were “no risk groups,” only “risky behaviors” (Schiller, Crystal, & Lewellen, Citation1994). As of September 2021, however, MSM in the Netherlands are able to donate blood if they are in a long-term, monogamous relationship. In the second half of the 2010s in Sweden, the public opinion and advocacy campaign named “Rainbow Blood” led the National Board of Health and Welfare to change the rules for blood donation to allow gay and bisexual men who have not had sex for one year to donate blood. In May 2021, the National Board of Health and Welfare shortened the waiting period in Sweden to six months.

Offender or victim?

Both in Sweden and in the Netherlands, the discovery of AIDS and subsequently HIV as a cause was met with fear (Hageman, Citation2018; Månsson, Citation1990). Attempts were made to take into account the fact that the increased risk among gay men could lead to further stigmatization of this already vulnerable group and opted for a message aimed at the general public, rather than targeting the high-risk groups. In the Netherlands, the motto was “Prevention can be done, cure cannot. Have safe sex, stop AIDS” (Hageman, Citation2018). In Sweden, however, the motto “We can cure your anxiety” was used by the Swedish government to convince people to get tested (Månsson, Citation1990). The problem with this slogan, is that anxiety was only relieved in the case of a negative test result and thus did not catch on with those at risk, and even resulted in a slight decrease in testing among gay and bisexual men (Månsson, Citation1990). The slogan was in keeping with a broader focus in Sweden on wanting to protect the general masses; thus treating those who spread the virus not only as victims, but also as perpetrators. In contrast, RFSL published a 16-pages-long brochure in 1983 that detailed the complex symptomatology that AIDS presented itself with, including information on its dismal prognosis and the lack of medical treatments available at the time (Thorsén, Citation2013). To accentuate the seriousness of the situation, the brochure read (in upper-case letters) “EVERYTHING SPEAKS FOR AIDS BEING INFECTIOUS” (Thorsén, Citation2013, p. 55) and also urged people to practice safer sex. This example further illustrates the lack of dissonance between the Swedish government and the nonprofit sector at large (including the gay community), as the various strategies proposed to prevent the spread of AIDS often contradicted each other (Svéd, Citation2000). Such a dissonance was not to be seen in the Netherlands where AIDS policy instead grew out of collaboration between various interested parties, both governmental and nonprofit alike (Sandfort, Citation1998, p. 4).

Despite Sweden being seen as liberal when it comes to sex and sexuality, at the same time there is a pronounced moral limitation to this; sex is good and allowed, as it goes: “socially approved, mutually satisfying sexual relations between two (and only two) consenting adults or young adults who are more or less sociological equals” (Dennermalm et al., Citation2019; Kulick, Citation2005, p. 208). Casual sex and risky sex behavior among gay men was condemned, including in the media, and in 1987 there was a so-called “ban on sauna clubs” implemented by the Swedish Parliament. Historically sauna clubs functioned as a hidden safe place for men who wanted to have sex with other men, where they could feel free from condemnation and stigma (Bérubé, Citation2003). Ultimately, the sauna clubs had to be closed down because these spaces were primarily seen as venues for sexual liaisons, which thus increased the risk of spreading HIV among the population and where concerns for sexual health became like a “distant memory” (Finer, Citation1988; Woods & Binson, Citation2003). In addition, in 1988 it became mandatory for people with HIV in Sweden to disclose one’s HIV status to sexual partners (as to practice safer sex), and violating these rules was punishable by law (Andersson, Citation2003; Finer, Citation1988). Only with improved possibilities to treat HIV and prevent infection (see ), the reporting obligation has later (in 2013) been abolished for people who have an undetectable plasma viral load, are therapy compliant and are not known to have another sexually transmitted disease (Albert et al., Citation2014). Nonprofit organizations have always tended to criticize the offender approach, and some doctors from the Swedish “Doctors against AIDS” even broke the law and allowed people to test anonymously (Finer, Citation1988). Although it is not exactly known why this approach was ultimately chosen by the Swedish government (Svéd, Citation2000), the greater need for control over life (anatomo-politics), moral condemnation of free sex, and negative media portrayals of the gay scene, may have had something to do with it. Even more so, during the 1980s the Swedish government evidently sought to prioritize public announcements that targeted the general population (“AIDS concerns everyone”)—rather than any certain “at-risk” group in particular. George Svéd, previous chairperson of RFSL, noted that after multiple back and forths, the National Board of Health and Welfare only granted RFSL a total of “25,000 SEK” (Citation2000, p. 231) to run their so-called “internal health campaigns” (i.e., for gay and bisexual men), whereas the government-led Swedish National Commission on AIDS was practically given an unlimited budget for theirs (which targeted the nuclear family). At large there was a lack of communication and consensus between the Government of Sweden and RFSL, especially as their “practice safe sex” campaigns contradicted each other and pointed to different prevention strategies and interventions in Swedish society (Svéd, Citation2000; Thorsén, Citation2013).

However, while NGOs in the Netherlands primarily focused on providing and disseminating information (e.g., safe sex guides) to prevent the spread of HIV (similarly to those in Sweden), science-based prevention strategies always remained central—with both government agencies and nonprofit organizations. It goes without saying that some Western European countries responded more efficiently to HIV and AIDS than others did. As Aggleton wrote: “While many governments procrastinated pretending that AIDS would not become a major public health issue, a few reacted more positively acting quickly to control the epidemic and to provide care and support to people who were directly affected. Without doubt, the Netherlands’ response was of the latter kind” (Citation1998, p. xiii). Sandfort pointed to this said response in more detail, writing that at the time AIDS was first detected “a number of organizations already existed [in the Netherlands] with sufficient knowledge and experience to meet the needs of groups most at risk for HIV infection” (Citation1998, p. 3). Moreover, in the Netherlands there remained a general awareness that AIDS was not just a biomedical problem—but also had “major social and political dimensions” (Sandfort, Citation1998, p. 4), more so than other diseases at the time. The Dutch government did not dictate how transmission of HIV was to be prevented, as such, and neither did the medical authorities (Moerkerk, Citation1990; Sandfort, Citation1998). In fact, HIV/AIDS policies in the Netherlands were grounded in private initiative, where “various interested parties of different backgrounds and sometimes conflicting interests collaborated” with one another (Sandfort, Citation1998, p. 4; see also Schnabel, Citation1989). Already fairly influential in Dutch society at the time, in contrast to Sweden (Andreasson, Citation2000), the Dutch gay movement was an active participant in this collaboration.

In the Netherlands, on the other hand, unlike in Sweden (Christianson et al., Citation2008) the consensus has always been that both people living with HIV, and those who do not, have a responsibility in not spreading the virus and furthermore assumed that criminalizing spreading might actually have the opposite effect, such as more anonymous contacts and fear of testing (Kuijsten, Citation2017; Schaalma et al., Citation1993). As Sandfort wrote: “In preventing HIV infection, the starting principle was that people are responsible for both their own and other people’s health and that moralizing doesn’t help” (Citation1998, p. 4). That said, there have been regular discussions about the criminality of intentionally transmitting HIV, which does end up being seen as punishable under the circumstance of power imbalance, coercion, or deception (Donner, Citation2005).

However, while in the Netherlands as well as in Sweden, cases have made the news of people who have intentionally infected others with HIV, it has never been examined whether these reports have influenced people’s attitudes about others with HIV. Moreover, in Sweden specifically these cases have tended to revolve around heterosexual men (Ljung, Citation2001) spreading the virus to women (while HIV is predominantly found in gay men and other MSM). As such, while intentional transmission of HIV has been deemed a criminal act without bias, at large such policies have mostly come to affect the MSM population (or even people completely unaware of their HIV status). This is why criminalization for long has been seen as counter-productive by NGOs in Sweden, as it ultimately comes to affect the wrong persons (Ljung, Citation2001; Thorsén, Citation2013).

That said, although both countries could not fully prevent gay men being negatively affected by stigmas that resulted from the higher prevalence of HIV in this population, in both countries the level of internalized homonegativity remained low compared to other countries (Ross et al., Citation2013).

A balance of risks: Statistical probabilities and the human factor

The history of both cultures has always involved a complex interplay of statistical probabilities and the human factor. There has always been consideration for the fact that the odds being greater for MSM to obtain and spread the virus can increase stigma, and testing campaigns have, for example, therefore often focused on all people, instead of the specific MSM risk groups (Finer, Citation1988; Hageman, Citation2018). With increasing insights, there is also reduced stigma in society toward gay men and MSM (Bos et al., Citation2001). Both the improvements in treatment and the reduction in stigma benefit the quality of life of MSM living with HIV, which was still significantly lower at the beginning of the century (Eriksson et al., Citation2000) than in later studies that have seen a reduction in stigma (Zeluf-Andersson et al., Citation2019), but still demonstrate HIV/AIDS-related stigma about MSM (Haney, Citation2016; Herder, Agardh, Citation2019; Jallow et al., Citation2007; Stutterheim et al., Citation2014; Zimmermann et al., Citation2021).

In a similar way, individuals do make considerations. On the one hand, with improved treatment methods, people have also become less afraid of HIV, and this is reflected in their (more risky) sexual behavior (Heijman et al., Citation2012; Van Den Boom et al., Citation2013; Zimmermann et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, several studies show that MSM in particular, who tend to have more casual sexual encounters (and do not use condoms), are also more willing to take measures to reduce the risks by using PrEP and getting tested; especially with advancing understanding and improved education (Bil et al., Citation2015; Den Daas et al., Citation2016; Herder et al., Citation2020; Janssen et al., Citation2001; Ross et al., Citation2014; Slurink et al., Citation2020). The highest HIV risks are therefore found in a minority group of “risk-taking” MSM, who tend to use substances that lead to certain behavioral inhibitions (Basten et al., Citation2018; Persson et al., Citation2015; Petersson et al., Citation2016), and/or choose to have unsafe sex in other countries (Persson et al., Citation2018).

A problem with statistical probabilities, however, is that they are not “fair” in human terms or from cultural perspectives (Asad, Citation1994; Urla, Citation1993). Statistics, as such, can be overly misleading and misrepresentative. The same behavior, such as unsafe anal sex, may be less risky within heterosexual contacts than for MSM; given that there are more people with HIV within the MSM population. Moreover, people are not only guided by statistics, but also by emotions and desires. As explained by Herek (Citation2007), in many societies there is sexual stigma or “socially shared knowledge about homosexuality’s devalued status in society” (p. 907). Regardless of people’s individual opinions and own sexual preferences, there is an awareness of the fact that they live in a social context where there exist negative stereotypes about homosexuality; considered to be deviant, whereas heterosexuality is considered the norm. This can create feelings of shame and stigma, but also self-stigma, where people’s self-concept is affected by internalization of stigma (Herek, Citation2007). That is, the fear of reinforcing the stigma that people with HIV practice unsafe sex, or that others may think that someone who has HIV stands in the way of prevention, such as refusing preventive PrEP use (e.g., Gaspar et al., Citation2022; Herder et al., Citation2020; Marra & Hankins, Citation2015; Montess, Citation2020).

Fears, perceived stigma, but also continued poor education (about sexual health, especially), can keep people from not getting tested (Den Daas et al., Citation2016; Persson et al., Citation2016; Slurink et al., Citation2021) and also cause delays in seeking health care after diagnosis (Van Veen et al., Citation2015). Moreover, some men may continue to have unsafe anal sex in the first year following HIV diagnosis, much due to their emotional state and difficulty with accepting the diagnosis and changing their behavior thereafter (Heijman et al., Citation2017).

Prevention

When it comes to encouragement of prevention, testing and treatment, research in both countries shows that it is important to especially educate the more difficult-to-reach groups, such as ethnic minority groups and young people who do not (yet) dare to openly express their non-heterosexual identities, for example through (more anonymous) online education and interventions (Den Daas et al., Citation2019; Schonnesson et al., Citation2015; Tikkanen & Ross, Citation2003; Van Veen et al., Citation2015). Network testing, as well as low-threshold places where people are able to get tested and access screening, increase the likelihood of people getting tested (Krabbenborg et al., Citation2021; Schonneson et al., Citation2015; Strömdahl et al., Citation2019).

With respect to PrEP or condom-use as prevention, Dutch studies emphasize that there is a trade-off between the convenience of not having to use condoms when using PrEP on the one hand, and an increased risk of STDs and disapproval because PrEP does not offer protection against STDs (and because its use may imply a licentious sex life as it is mainly used by risk groups), on the other hand (Van Bilsen et al., Citation2019; Van Dijk et al., Citation2021; Zimmerman et al., Citation2020). Potential side-effects may also be a reason for people not using PrEP (Van Dijk et al., Citation2020). Appropriate knowledge is widely available, although knowledge among some health professionals is still not up to date (Van Dijk et al., Citation2021). Swedish researchers have not yet addressed these issues explicitly, with the exception of a qualitative study carried out in 2016 among Swedish MSM traveling to Berlin, with experience of substance abuse. It was found that these men held positive attitudes toward the use of PrEP (Dennermalm et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, public information about PrEP by Swedish and Dutch organizations is very similar, mentioning the advantages and disadvantages and further procedures. However, it seems that in the Netherlands the emphasis is more on using PrEP because people may prefer not to use a condom (Mantoman, Citation2021), whereas in Sweden the emphasis is more on using PrEP if you are not good at using a condom (RFSL, Citation2018).

With respect to informing others about one’s positive HIV status, an important difference is that people are not forced to disclose their positive HIV status in the Netherlands, whereas they are still obliged to do so upon diagnosis in Sweden (or at least until the point where their viral load is effectively zero). As a consequence, there is more room in the Netherlands than in Sweden for policies that explicitly aim to help someone inform others without negative consequences (Götz & Spijker, Citation2018). Possible ways of doing this include health professionals informing the sexual partners and contact tracing, i.e., informing the wider social network within which the infection may have taken place. In both cases, the ill person can remain anonymous (Götz & Spijker, Citation2018; Van Aar et al., Citation2012).

However, the effects and consequences of these differences in preventive approaches remain unclear. Firstly, there are almost no studies comparing Sweden and the Netherlands. The most recent European HIV/AIDS surveillance shows that the number of new HIV diagnoses in the Netherlands was 2.3 per 100,000 population and in Sweden 3.5 per 100,000 population, whereas specifically for MSM the rates were 1.4 for the Netherlands and 1.1 for Sweden (European Union, Citation2021). This indicates that relatively more MSM persons have been diagnosed with HIV in the Netherlands. However, it does not tell us why this is; whether it has to do with the cultural-historical context and differences in prevention policy or even just with the larger population of homosexual people in the Netherlands (Varrella, Citation2021). It is found that whereas people are tested positively in one country, the infection can have taken place in another country; for example, where HIV is still more widespread and fewer measures of prevention are in place. In fact, this is the case for Sweden. With approximately 400 to 500 new cases of HIV reported each year, the majority of the new diagnoses in Sweden consist of cases where the HIV infection has been transmitted before migration to the country (Mehdiyar et al., Citation2020, Citation2016). This may perhaps also explain the recent discovery of the highly virulent subtype-B lineage of HIV-1 (i.e., the “VB variant”) circulating in the Netherlands (Wymant et al., Citation2022), which is the most common variant of HIV found in the Middle East and North Africa.

Concluding remarks

This narrative review makes clear that in the Netherlands and Sweden, despite sharing a fairly similar cultural ethos, certain context-specific historical events and culturally determined processes have led to some important differences in how HIV and AIDS and the higher risks for gay men (or MSM, more broadly) have been dealt with throughout the years. Both countries have certainly made many positive steps in combating AIDS and stopping further spread of HIV. In the Netherlands, there is a stronger protective attitude when it comes to the freedom and autonomy of MSM; both when it comes to decisions about sexual behavior and to sharing any positive HIV status. In Sweden, on the other hand, there is a stronger tendency to enforce certain behavior through policymaking, which the wider masses tend to abide. Besides the pronounced cultural tendencies—to trust others more in the Netherlands, to place focus on control over life in Sweden (with a less liberal orientation toward casual sex)—the Dutch “Bloody Sunday” seems to have been responsible for this approach, which was a historical event that took place due to already existing networks between the blood transfusion and health services and the Dutch gay movement. In contrast, such a network did not yet exist in Sweden in the early 1980s (and in many ways, still does not exist to this day).

In both countries, the risk of further stigmatization of gay men has been dealt with consciously, yet these measures have not been able to completely prevent the discovery of HIV/AIDS from becoming strongly associated with stigma. Moreover, talking about “MSM” rather than “gay men” more specifically seems to have had little effect. The improved options in both HIV prevention and treatment have led to a reduction in stigma and improved quality of life for people living with the virus, but there is still further progress to be made in this regard. This will also be necessary more precisely because stigma is currently seen as a limiting factor in prevention.

This narrative review aims, at large, to encourage researchers to show more consideration for the cultural-historical context in research on HIV. Future research could potentially focus on cross-country comparisons in order to better understand opportunities to strengthen prevention, as well as achieve the fourth “90” goal in terms of health-related quality of life for people living with HIV. In the predominantly gay-friendly countries where much has been invested in education and treatment, this will presumably be easier than in countries with less optimal conditions in this regard. More broadly, such comparisons may also be able to provide insights about the influence of cultural-historical context in countering other infectious diseases on a global scale.

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. That said, the authors extend many thanks to the University Library at Jönköping University for agreeing to pay for the Open Access fees of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aggleton, P. (1998). Series editor’s preface. In T. Sandfort (Ed.), The Dutch response to HIV. UCL Press.

- Akshaya, A., Jothi Priya, A., & KR, D. (2021). Recent advances in the treatment of HIV infection-A review. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology, 25(3), 5891–5903. https://www.annalsofrscb.ro/index.php/journal/article/view/2124

- Albert, J., Berglund, T., Gisslén, M., Gröön, P., Sönnerborg, A., Tegnell, A., … Widgren, K. (2014). Risk of HIV transmission from patients on antiretroviral therapy: A position statement from the public health agency of Sweden and the Swedish reference group for antiviral therapy. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 46(10), 673–677. doi:10.3109/00365548.2014.926565

- Andersson, S. (2003). 1988 års smittskyddslag. [1988’s Contagious Diseases Act]. In S. Andersson & S. Sjödahl (Eds.), Sex: En Politisk Historia. Gothenburg, Sweden: Alfabeta Bokförlag AB.

- Andersson, G. Z., Reinius, M., Eriksson, L. E., Svedhem, V., Esfahani, F. M., Deuba, K., … Ekström, A. M. (2020). Stigma reduction interventions in people living with HIV to improve health-related quality of life. The Lancet HIV, 7(2), e129–e140. doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30343-1

- Andreasson, M. (Ed.). (2000). Homo i Folkhemmet: Homo- och Bisexuella i Sverige 1950–2000. [Homo in the Swedish Folkhem: Homo- and bisexual people in Sweden 1950-2000]. Gothenburg, Sweden: Anamma.

- Asad, T. (1994). Ethnographic representation, statistics and modern power. Social Research, 61(1), 55–88. doi:10.1215/9780822383345-003

- Barnett, T., & Whiteside, A. (2002). AIDS in the twenty-first century: Disease and globalization . Palgrave Macmillan.

- Basten, M., Heijne, J. C. M., Geskus, R., Den Daas, C., Kretzschmar, M., & Matser, A. (2018). Sexual risk behaviour trajectories among MSM at risk for HIV in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. AIDS, 32(9), 1185–1192. doi:10.1097/qad.0000000000001803

- Berner, B. (2011). The making of a risk object: AIDS, gay citizenship and the meaning of blood donation in Sweden in the early 1980s. Sociology of Health & Illness, 33(3), 384–398. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01299.x

- Bérubé, A. (2003). The history of gay bathhouses. Journal of Homosexuality, 44(3–4), 33–53. doi:10.1300/J082v44n03_03

- Bil, J. P., Davidovich, U., van der Veldt, W. M., Prins, M., de Vries, H. J. C., Sonder, G. J. B., & Stolte, I. G. (2015). What do Dutch MSM think of preexposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV-infection? A cross-sectional study. AIDS, 29(8), 955–964. doi:10.1097/qad.0000000000000639

- Boellstorff, T. (2011). But do not identify as gay: A proleptic genealogy of the MSM category. Cultural Anthropology, 26(2), 287–312. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1360.2011.01100.x

- Bos, A. E. R., Kok, G., & Dijker, A. J. (2001). Public reactions to people with HIV/AIDS in the Netherlands. AIDS Education and Prevention, 13(3), 219–228. doi:10.1521/aeap.13.3.219.19741

- Braekhus, L. A. (2020, March 1). Norske Roar var Sveriges første aids-offer [Norwegian Roar was Sweden’s first AIDS victim]. ABC Nyheter. https://www.abcnyheter.no/helse-og-livsstil/helse/2020/03/01/195652804/norske-roar-var-sveriges-forste-aids-offer

- Christianson, M., Lalos, A., & Johansson, E. (2008). The law of communicable diseases act and disclosure to sexual partners among HIV-positive youth. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 3(3), 234–242. doi:10.1080/17450120802069109

- Den Daas, C., Doppen, M., Schmidt, A. J., & De Coul, E. O. (2016). Determinants of never having tested for HIV among MSM in the Netherlands. BMJ Open, 6(1), e009480. doi:10.1136/BMJOPEN-2015-009480

- Den Daas, C., Geerken, M. B. R., Bal, M., de Wit, J., Spijker, R., & Op de Coul, E. L. M. (2019). Reducing health disparities: Key factors for successful implementation of social network testing with HIV self-tests among men who have sex with men with a non-western migration background in the Netherlands. AIDS Care, 1–7. doi:10.1080/09540121.2019.1653440

- Dennermalm, N., Ingemarsdotter Persson, K., Thomsen, S., & Forsberg, B. C. (2019). “You can smell the freedom”: A qualitative study on perceptions and experiences of sex among Swedish men who have sex with men in Berlin. BMJ Open, 9(6), e024459. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024459

- Dennermalm, N., Scarlett, J., Thomsen, S., Persson, K. I., & Alvesson, H. M. (2021). Sex, drugs and techno–a qualitative study on finding the balance between risk, safety and pleasure among men who have sex with men engaging in recreational and sexualised drug use. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–12. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10906-6

- Dijstelbloem, H. (2014). Missing in action: Inclusion and exclusion in the first days of AIDS in The Netherlands. Sociology of Health & Illness, 36(8), 1156–1170. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12159

- Donner, J. P. H. (2005). Consequenties uitspraak van de Hoge Raad van 18 januari 2005 inzake strafbaarheid overbrengen mogelijke HIV-besmetting [Consequences of Supreme Court ruling of 18 January 2005 on criminality of transmitting possible HIV infection]. Letter from the Minister of Justice to the President of the Lower House of the States General, No. 157. https://www.parlementairemonitor.nl/9353000/1/j9vvij5epmj1ey0/vi3anz9jgdzv

- Eriksson, L. E., Nordstrom, G., Berglund, T., & Sandstrom, E. (2000). The health-related quality of life in a Swedish sample of HIV-infected persons. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(5), 1213–1223. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01592.x

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. (2020). HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2020 (2019 data). European Union. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/hivaids-surveillance-europe-2020-2019-data

- European Union. (2021). HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2021 – 2020 data. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2021-Annual_HIV_Report_0.pdf

- Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing, 24(4), 230–235. doi:10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

- Finer, D. (1988). The HIV/AIDS situation in Sweden. Swedish Institute.

- Galesloot. (2007). Angst en fascinatie voor aids [Fear and fascination for AIDS]. Ons Amsterdam, nov/dec. https://onsamsterdam.nl/angst-en-fascinatie-voor-aids

- Gaspar, M., Wells, A., Hull, M., Tan, D. H. S., Lachowsky, N., & Grace, D. (2022). “What other choices might I have made?”: Sexual minority men, the Prep cascade and the shifting subjective dimensions of HIV risk. Qualitative Health Research, OnlineFirst, May 26, 2022, doi:10.1177/10497323221092701

- Gisslén, M., Svedhem, V., Lindborg, L., Flamholc, L., Norrgren, H., Wendahl, S., … Sönnerborg, A. (2017). Sweden, the first country to achieve the joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)/World Health Organization (WHO) 90‐90‐90 continuum of HIV care targets. HIV Medicine, 18(4), 305–307. doi:10.1111/hiv.12431

- Götz, H., & Spijker, R. (2018). Soa en HIV partner management; Waarschuwen, testen en behandelen van seksuele partners. Draaiboek. Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport. https://lci.rivm.nl/draaiboeken/partnermanagement

- Hageman, M. (2018, June). De opkomst van aids; Aids in de polder [The rise of AIDS; AIDS in the polder]. Historisch Nieuwsblad. https://www.historischnieuwsblad.nl/de-opkomst-van-aids/

- Haney, J. L. (2016). Predictors of homonegativity in the United States and the Netherlands using the Fifth Wave of the World values survey. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(10), 1355–1377. doi:10.1080/00918369.2016.1157997

- Hankins, C. A., Wainberg, M. A., & Weiss, R. A. (2014). In tribute to Joep Lange. Retrovirology, 11(1), 1749. doi:10.1186/s12977-014-0082-z

- Heijman, T., Geskus, R. B., Davidovich, U., Coutinho, R. A., Prins, M., & Stolte, I. G. (2012). Less decrease in risk behaviour from pre-HIV to post-HIV seroconversion among MSM in the combination antiretroviral therapy era compared with the pre-combination antiretroviral therapy era. AIDS, 26(4), 489–495. doi:10.1097/qad.0b013e32834f9d7c

- Heijman, T., Zuure, F., Stolte I. & Davidovich, U. (2017). Motives and barriers to safer sex and regular STI testing among MSM soon after HIV diagnosis. BMC Infectious Diseases, 17(1). doi:10.1186/s12879-017-2277-0

- Herder, T., & Agardh, A. (2019). Navigating between rules and reality: A qualitative study of HIV positive MSM’s experiences of communication at HIV clinics in Sweden about the rules of conduct and infectiousness. AIDS Care, 1–7. doi:10.1080/09540121.2019.1566590

- Herder, T., Agardh, A., Björkman, P., & Månsson, F. (2020). Interest in taking HIV Pre-exposure prophylaxis is associated with behavioral risk indicators and self-perceived HIV risk among men who have sex with men attending HIV testing venues in Sweden. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(6), 2165–2177. doi:10.1007/s10508-020-01740-9

- Herek, G. M. (2007). Confronting sexual stigma and prejudice: Theory and practice. Journal of Social Issues, 63(4), 905–925. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00544.x

- Inglehart, R., Haerpfer, C., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., … Puranen, B. et al. (eds.). (2014). World values survey: Round six - country-pooled datafile version. Madrid: JD Systems Institute. www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp

- Jallow, A., Sporrong, S. K., Walther-Jallow, L., Persson, P. M., Hellgren, U., & Ericsson, Ö. (2007). Common problems with antiretroviral therapy among three Swedish groups of HIV infected individuals. Pharmacy World & Science, 29(4), 422–429. doi:10.1007/s11096-007-9092-4

- Janssen, M., de Wit, J., Hospers, H. J., & Van Griensven, F. (2001). Educational status and young Dutch gay men’s beliefs about using condoms. AIDS Care, 13(1), 41–56. doi:10.1080/09540120020018170

- Jongen, V. W., Hoornenborg, E., Elshout, M. A., Boyd, A., Zimmermann, H. M., Coyer, L., … SchimVan der Loeff, M. F., & the Amsterdam PrEP Project team in H-TEAM Initiative. (2021). Adherence to event‐driven HIV PrEP among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Analysis based on online diary data, 3‐monthly questionnaires and intracellular TFV‐DP. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 24(5). doi:10.1002/jia2.25708

- Koster, A. (2019, May 31). 1982: AIDS. Out in Rotterdam. https://digitup.nl/outinrotterdam/1982-aids/

- Kowalewski, M. R. (1988). Double stigma and boundary maintenance: How gay men deal with AIDS. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 17(2), 211–228. doi:10.1177/089124188017002004

- Krabbenborg, N., Spijker, R., Żakowicz, A. M., de Moraes, M., Heijman, T., & de Coul, E. O. (2021). Community-based HIV testing in The Netherlands: Experiences of lay providers and end users at a rapid HIV test checkpoint. AIDS Research and Therapy, 18(1). doi:10.1186/s12981-021-00357-9

- Kuijsten, S. (2017, June 1). HIV-jurisprudentie; vier zaken [HIV case law; four cases]. Het Rechtenstudentje. https://www.hetrechtenstudentje.nl/jurisprudentie/hiv-jurisprudentie-vier-zaken/

- Kulick, D. (2005). Four hundred thousand Swedish perverts. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 11(2), 205–235. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/179985/summary

- Ljung, A. (2001). Bortom oskuldens tid: en etnologisk studie av moral, trygghet och otrygghet i skuggan av hiv. Uppsala, Sweden: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

- Månsson, S. A. (1990). Phucho-social aspects of HIV testing—the Swedish case. AIDS Care, 2(1), 5–16. doi:10.1080/09540129008257708

- Mantoman. (2021, August 3). PrEP tegen hiv [PrEP against HIV]. https://mantotman.nl/nl/snel-regelen/prep-tegen-hiv

- Marra, E., & Hankins, C. A. (2015). Perceptions among Dutch men who have sex with men and their willingness to use rectal microbicides and oral pre-exposure prophylaxis to reduce HIV risk – A preliminary study. AIDS Care, 27(12), 1493–1500. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1069785

- Mason, S. & Sultzman, V Olds. (2019). Stigma as experienced by children of HIV-positive parents: a narrative review. AIDS Care, 31(9), 1049–1060. doi:10.1080/09540121.2019.1573968

- Mehdiyar, M., Andersson, R., Hjelm, K., & Povlsen, L. (2016). HIV-positive migrants’ encounters with the Swedish health care system. Global Health Action, 9(1), 31753. doi:10.3402/gha.v9.31753

- Mehdiyar, M., Andersson, R., & Hjelm, K. (2020). HIV-positive migrants’ experience of living in Sweden. Global Health Action, 13(1), 1715324. doi:10.1080/16549716.2020.1715324

- Moerkerk, H. (1990). AIDS prevention strategies in European countries. In M. Paalman (Ed.) Promoting safer sex: Proceedings of an International Workshop, May 1989, the Netherlands. Swets & Zeitlinger.

- Montess, M. (2020). Demedicalizing the ethics of PrEP as HIV prevention: The social effects on MSM. Public Health Ethics, 13, 288–299. doi:10.1093/phe/phaa016

- Mooij, A. (2004). Geen paniek! (No panic!). Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

- Oosting, M. (1995). Openbaar rapport: Klacht over een gedraging van het ministerie van Welzijn, Volksgezondheid en Cultuur vanuit de Nederlandse Vereniqinq van Hemofilie-Patienten aan de Nationale Ombudsman, 95/271[Public report: Complaint about a conduct of the Ministry of Welfare, Public Health and Culture from the Dutch Association of Haemophilia Patients to the National Ombudsman]. https://www.nationaleombudsman.nl/system/files/rapport/Rapport%201995271.pdf

- Parry, M. S., & Schalkwijk, H. (2020). Lost objects and missing histories: HIV/AIDS in the Netherlands. In Museums, sexuality, and gender activism (pp. 113–125). Routledge.

- Patel, P., Borkowf, C. B., Brooks, J. T., Lasry, A., Lansky, A., & Mermin, J. (2014). Estimating per-act HIV transmission risk: A systematic review. AIDS (London, England), 28(10), 1509. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000298

- Patel, K., Zhang, A., Zhang, M. H., Bunachita, S., Baccouche, B. M., Hundal, H., … Patel, U. K. (2021). Forty years since the epidemic: Modern paradigms in HIV diagnosis and treatment. Cureus, 13(5), e14805. doi:10.7759/cureus.14805

- Persson, K. I., Tikkanen, R., Bergström, J., Berglund, T., Thorson, A., & Forsberg, B. C. (2015). Experimentals, bottoms, risk-reducers and clubbers: Exploring diverse sexual practice in an Internet-active high-risk behaviour group of men who have sex with men in Sweden. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 18(6), 639–653. doi:10.1080/13691058.2015.1103384

- Persson, K. I., Berglund, T., Bergström, J., Eriksson, L. E., Tikkanen, R., Thorson, A., & Forsberg, B. C. (2016). Motivators and barriers for HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Sweden. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(23–24), 3605–3618. doi:10.1111/jocn.13293

- Persson, K. I., Berglund, T., Bergström, J., Tikkanen, R., Thorson, A., & Forsberg, B. (2018). Place and practice: Sexual risk behaviour while travelling abroad among Swedish men who have sex with men. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 25, 58–64. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.01.009

- Petersson, F. J. M., Tikkanen, R., & Schmidt, A. J. (2016). Party and play in the closet? Exploring club drug use among Swedish men who have sex with men. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(9), 1093–1103. doi:10.3109/10826084.2016.1160117

- Piot, P. (2006). The HIV pandemic: Local and global implications. Oxford University Press.

- Purcell, D. W. (2021). Forty years of HIV: The intersection of laws, stigma, and sexual behavior and identity. American Journal of Public Health, 111(7), 1231–1233. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2021.306335

- RFSL. (2018, December 20). PrEP. https://www.rfsl.se/en/organisation/health-sexuality-and-hiv/prep/

- Rodger, A. J., Cambiano, V., Bruun, T., Vernazza, P., Collins, S., Degen, O., … Pechenot, V. (2019). Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (PARTNER): Final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. The Lancet, 393(10189), 2428–2438. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30418-0

- Ross, M. W., Berg, R. C., Schmidt, A. J., Hospers, H. J., Breveglieri, M., Furegato, M., & Weatherburn, P. (2013). Internalised homonegativity predicts HIV-associated risk behavior in European men who have sex with men in a 38-country cross-sectional study: some public health implications of homophobia. British Medical Journal, 3(2), e001928. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001928

- Ross, M. W., Tikkanen, R., & Berg, R. C. (2014). Gay community involvement: Its interrelationships and associations with internet use and HIV risk behaviors in Swedish men who have sex with men. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(2), 323–333. doi:10.1080/00918369.2013.839916

- Sandfort, T. (1998). Pragmatism and consensus: The Dutch response to HIV. In T. Sandfort (Ed.), The Dutch response to HIV. UCL Press.

- Schaalma, H. P., Petesr, L., & Kok, G. (1993). Reactions among Dutch youth toward people with AIDS. Journal of School Health, 63(4), 182–187. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.1993.tb06113.x

- Schiller, N. G., Crystal, S., & Lewellen, D. (1994). Risky business: The cultural construction of AIDS risk groups. Social Science & Medicine, 38(10), 1337–1346. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)90272-0

- Schnabel, P. (1989). De diepten van een epidemic; over de maatschappelijke gevolgen van AIDS. [The depths of an epidemic; on the social consequences of AIDS. In A. Noordhof-DeVries (Ed.), AIDS; een Nieuwe Verantwoordelijkheid voor Gezondheidszorg en Onderwijs. Swets & Zeitlinger.

- Schonnesson, L. N., Bowen, A. M., & Williams, M. L. (2015). Project SMART: Preliminary results from a test of the efficacy of a Swedish internet-based HIV risk-reduction intervention for men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(6), 1501–1511. doi:10.1007/s10508-015-0608-z

- Sharp, P. M., & Hahn, B. H. (2011). Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 1(1), a006841. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006841

- Slurink, I. A. L., van Benthem, B. H. B., van Rooijen, M. S., Achterbergh, R. C. A., & van Aar, F. (2020). Latent classes of sexual risk and corresponding STI and HIV positivity among MSM attending centres for sexual health in the Netherlands. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 96(1), 33–39. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2019-053977

- Slurink, I. A., Götz, H. M., van Aar, F., & van Benthem, B. H. (2021). Educational level and risk of sexually transmitted infections among clients of Dutch sexual health centres. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 095646242110136. doi:10.1177/09564624211013670

- Smith, T. W., Son, J., & Kim, J. (2014). Public attitudes toward homosexuality and gay rights across time and countries. (Report of the UCLA). School of Law, Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/public-attitudes-intl-gay-rights/

- Strömdahl, S., Hoijer, J., & Eriksen, J. (2019). Uptake of peer-led venue-based HIV testing sites in Sweden aimed at men who have sex with men (MSM) and trans persons: A cross-sectional survey. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 95(8), 575–579. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2019-054007

- Stutterheim, S. E., Sicking, L., Brands, R., Baas, I., Roberts, H., van Brakel, W. H., … Bos, A. E. R. (2014). Patient and provider perspectives on HIV and HIV-Related stigma in Dutch health care settings. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 28(12), 652–665. doi:10.1089/apc.2014.0226

- Svéd, G. (2000). När AIDS kom till Sverige. [When AIDS came to Sweden]. In M. Andreasson (Ed.), Homo i Folkhemmet: Homo- och Bisexuella i Sverige 1950–2000. Gothenburg, Sweden: Anamma.

- Thorsén, D. (2013) Den svenska aidsepidemin: Ankomst, bemötande, innebörd. [The Swedish AIDS epidemic: Arrival, response, and meaning]. (PhD dissertation). Uppsala, Sweden: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-193732

- Tikkanen, R., & Ross, M. W. (2003). Technological tearoom trade: Characteristics of Swedish men visiting gay internet chat rooms. AIDS Education and Prevention, 15(2), 122–132. doi:10.1521/aeap.15.3.122.23833

- Urla, J. (1993). Cultural politics in an age of statistics: Numbers, nations, and the making of Basque identity. American Ethnologist, 20(4), 818–843. doi:10.1525/ae.1993.20.4.02a00080

- Van Aar, F., Schreuder, I., van Weert, Y., Spijker, R., Götz, H., & de Coul, E. O. (2012). Current practices of partner notification among MSM with HIV, gonorrhoea and syphilis in the Netherlands: An urgent need for improvement. BMC Infectious Diseases, 12(1), 1–11. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-114

- Van Bilsen, W. P. H., Boyd, A., van der Loeff, M. F. S., Davidovich, U., Hogewoning, A., van der Hoek, L., … Matser, A. (2019). Diverging trends in incidence of HIV versus other sexually transmitted infections in HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) in Amsterdam. AIDS, 1. doi:10.1097/qad.0000000000002417

- Van den Berg, M., Bos, D. J., Derks, M., Ganzevoort, R. R., Jovanović, M., Korte, A. M., & Sremac, S. (2014). Religion, homosexuality, and contested social orders in the Netherlands, the Western Balkans, and Sweden. In Religion in times of crisis (pp. 116–134). Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004277793_008

- Van Den Boom, W., Stolte, I. G., Witlox, R., Sandfort, T., Prins, M., & Davidovich, U. (2013). Undetectable viral load and the decision to engage in unprotected anal intercourse among HIV-Positive MSM. AIDS and Behavior, 17(6), 2136–2142. doi:10.1007/s10461-013-0453-9

- Van Dijk, M., Duken, S. B., Delabre, R. M., Stranz, R., Schlegel, V., Rojas Castro, D., … Jonas, K. J. (2020). PrEP interest among men who have sex with men in the Netherlands: Covariates and differences across samples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(6), 2155–2164. doi:10.1007/s10508-019-01620-x

- Van Dijk, M., de Wit, J. B. F., Kamps, R., Guadamuz, T. E., Martinez, J. E., & Jonas, K. J. (2021). Socio-Sexual experiences and access to healthcare among informal PrEP users in the Netherlands. AIDS and Behavior, 25(4), 1236–1246. doi:10.1007/s10461-020-03085-9

- Van Doornum, G., Van Helvoort, T., & Sankaran, N. (2020). Leeuwenhoek’s Legatees and Beijerinck’s beneficiaries: A history of medical virology in The Netherlands (pp. 361). Amsterdam University Press. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/22972/9789048544066.pdf?sequence=1

- Van Veen, M., Trienekens, S., Heijman, T., Gotz, H., Zaheri, S., Ladbury, G., … van der Sande, M. (2015). Delayed linkage to care in one-third of HIV-positive individuals in the Netherlands. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 91(8), 603–609. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2014-051980

- Varrella, S. (2021, October 18). Sexual attraction worldwide by country. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1270119/sexual-attraction-worldwide-country/

- Woods, W., & Binson, D. (2003). Public health policy and gay bathhouses. Journal of Homosexuality, 44(3–4), 1–21. doi:10.1300/J082v44n03_01

- World Health Organization. (2021, July 17). HIV/AIDS factsheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids

- Wymant, C., Bezemer, D., Blanquart, F., Ferretti, L., Gall, A., Hall, M., van Hes, A. M. H. et al. (2022). A highly virulent variant of HIV-1 circulating in the Netherlands. Science, 375(6580), 540–545. doi:10.1126/science.abk1688

- Young, R., & Meyer, I. (2005). The trouble with “MSM” and “WSW”: Erasure of the sexual-minority person in public health discourse. American Journal of Public Health, 95(7), 1144–1149. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.046714

- Zeluf-Andersson, G., Eriksson, L. E., Schönnesson, L. N., Höijer, J., Månehall, P., & Ekström, A. M. (2019). Beyond viral suppression: The quality of life of people living with HIV in Sweden. AIDS Care, 31(4), 403–412. doi:10.1080/09540121.2018.1545990

- Zimmermann, H. M., Jongen, V. W., Boyd, A., Hoornenborg, E., Prins, M., de Vries, H. J., … Davidovich, U. (2020). Decision-making regarding condom use among daily and event-driven users of preexposure prophylaxis in the Netherlands. Aids, 34(15), 2295–2304. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000002714

- Zimmermann, H. M., Bilsen, W. P., Boyd, A., Prins, M., Harreveld, F., & Davidovich, U. (2021). Prevention challenges with current perceptions of HIV burden among HIV‐negative and never‐tested men who have sex with men in the Netherlands: A mixed‐methods study. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 24(8). doi:10.1002/jia2.25715