Abstract

Introduction: As competency-based education has gained currency in postgraduate medical education, it is acknowledged that trainees, having individual learning curves, acquire the desired competencies at different paces. To accommodate their different learning needs, time-variable curricula have been introduced making training no longer time-bound. This paradigm has many consequences and will, predictably, impact the organization of teaching hospitals. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of time-variable postgraduate education on the organization of teaching hospital departments.

Methods: We undertook exploratory case studies into the effects of time-variable training on teaching departments’ organization. We held semi-structured interviews with clinical teachers and managers from various hospital departments.

Results: The analysis yielded six effects: (1) time-variable training requires flexible and individual planning, (2) learners must be active and engaged, (3) accelerated learning sometimes comes at the expense of clinical expertise, (4) fast-track training for gifted learners jeopardizes the continuity of care, (5) time-variable training demands more of supervisors, and hence, they need protected time for supervision, and (6) hospital boards should support time-variable training.

Conclusions: Implementing time-variable education affects various levels within healthcare organizations, including stakeholders not directly involved in medical education. These effects must be considered when implementing time-variable curricula.

Background

In the past decade, postgraduate medical education (PGME) programs have widely adopted competency-based curricula. With its explicit focus on outcomes (Ten Cate and Scheele Citation2007; Frank et al. Citation2010; Englander et al. Citation2017), competency-based medical education (CBME) likely enhances accountability, making it an attractive educational innovation (Martin et al. Citation1998; Long Citation2000; Carraccio et al. Citation2002; Englander et al. Citation2017; Holmboe et al. Citation2017). A corollary to this transition to competency outcomes is that trainees acquire the desired competencies at different paces (Harden et al. Citation1999; Ten Cate and Scheele Citation2007), creating an argument for time-variable and individualized training.

Although the literature suggests that CBME will produce better doctors, the implementation of competency-based programs does not come without a cost (Laeeq et al. Citation2010; Jippes et al. Citation2012). Teaching hospital organizations, for instance, are greatly challenged (Ringsted et al. Citation2003; Ringsted et al. Citation2006; Ten Cate and Scheele Citation2007; Scheele et al. Citation2008; Lurie et al. Citation2009; Wasnick et al. Citation2010), as clinical teachers often struggle to implement new training methods in daily routines (van der Lee et al. Citation2013). The introduction of time-variable PGME complicates this issue even further as specialty training and clinical service are very much intertwined (Billett Citation2005; van Rossum et al. Citation2016; Holmboe et al. Citation2017), and trainees play an important role in the provision of healthcare. Time-variable training can put a strain on this relation and potentially lead to friction and conflict with the continuity of clinical service delivery (Greenhalgh et al. Citation2004; Greenhalgh et al. Citation2008; Greenhalgh et al. Citation2010; van Rossum et al. Citation2016). These potential downsides to time-variable training, however, have received scant attention in the literature (Lillevang et al. Citation2009).

Teaching hospitals are best described as complex, adaptive organizations consisting of multiple systems that interact in a complex manner (Plsek and Greenhalgh Citation2001; Wong et al. Citation2013; van Rossum et al. Citation2016). As the boundaries between their sub-systems are sometimes blurred, and change in one system, moreover, can affect other systems as well, the effects of such changes are highly unpredictable (Plsek and Greenhalgh Citation2001). It is through this lens of complexity theory that we aim to explore, using a systematic analysis, the effects of time-variable training programs on the organization of teaching hospitals. Insights into the effects of time-variable training may facilitate the implementation of outcome-based education and enhance its effectiveness. In doing so, we specifically focused on the organization of teaching units, addressing the following research question: In what ways does time-variable CBME impact the organization of teaching hospital departments?

Methods

Setting

We conducted this study in the Netherlands, where the fixed length of PGME programs had been abandoned since the adoption of new national regulations in the summer of 2014, signaling a switch to time-variable competency-based training programs. Although in the Netherlands PGME may be offered in either academic or non-academic hospitals, most programs educate their trainees in both settings. In gynecology, for instance, trainees receive three years of basic training in a non-academic setting and another 3 years of training in an academic setting. The number of trainees in each program varies making the total size of departments partly dependent on the PGME program that they offer.

Selection

As contextual differences between departments and institutions may affect the organization of PGME and, in turn, how the introduction of time-variable PGME programs unfolded, we took a purposive sample of departments (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967) that reflected this diversity in settings. Our first criterion was to select educational programs that varied in size and setting. We selected gynecology and obstetrics (large sized; around 15 trainees), neurology (medium sized; 6–10 trainees) and urology (small sized; 2–3 trainees), all in academic and non-academic hospitals. We subsequently included four other departments of other teaching hospitals who had extensive experience with the process of implementing time-variable education and, as such, had developed “best practices” in this field of endeavor.

As a next step, we invited the clinical teacher and the manager of each department to participate in an interview, as we believed these persons to be the best informed of tensions between the organization and education. Together, the clinical teacher and department manager were responsible for both the PGME program and clinical service. In some departments, however, particularly of university hospitals, there was only one individual who fulfilled both roles. In these cases, we did not include a second participant from the same hospital department.

Data collection

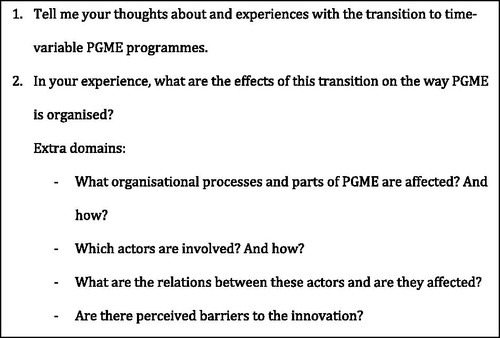

For our exploratory case study, we held in-depth, semi-structured interviews, in which we focused on the interaction between organizational systems during the transition to time-independent PGME programs. The initial questions were guided by theoretical concepts of complex organizations (). When new themes emerged during the interviews, we explored these and included them in the analysis.

The first author conducted all the interviews in a closed room in which only he and the participant were present. The interviews, which lasted about 50–75 min each, were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim and took place in the period between November and December 2015. We invited all participants to check a summary of the interview and they all confirmed its accuracy. All participants gave their written informed consent and were assured that their data would be processed anonymously. The study was approved by the ethical review board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO-ERB; file number 549).

Analysis

We analyzed the data using qualitative data analysis software MaxQDA (Marburg, Germany). We began the analysis during the data collection phase to facilitate the exploration of emerging themes and issues in subsequent interviews (Pope et al. Citation2000). Following a thematic analytical approach (Savin-Baden and Major Citation2012), the first author performed an initial open coding of the data. After six interviews, a second researcher (EP) open-coded two of the transcripts. The researchers discussed differences until they reached full agreement on the interpretation of the coding. These results were discussed with the full research group. Differences were resolved by combining or splitting codes. By constant comparison of the data, the results were organized around main categories, ultimately resulting into categorization in general themes.

Because the research process was done in active engagement, it is important to reflect on the background of the research team involved in this study (Watling and Lingard Citation2012). The main researcher (TvR) has a background in public administration and is, as a faculty of Maastricht University not in a position of power over the participants of this study. The other researchers are physicians and experts in health professions education research (EP, IH, HS) and in innovation, implementation and change management in medical education (FS). The professors are actively engaged in both national and international change initiatives in medical education, the main researcher and HS participate in both national and local projects to reform PGME.

Results

The total of 13 participants where affiliated with eight different departments, five of these departments where sited in non-academic teaching hospitals, three where associated with academic hospitals. Seven participants identified themselves as a clinical teacher and five participants identified themselves as a department manager. One participant identified himself both as clinical teacher and department manager. All participants had been actively involved in the transition from traditional PGME to time-variable and competency-based PGME. Overall the participants experienced the process as challenging. Although their responses point to differences between teaching hospitals and between departments in the way PGME and the transition to CBME were organized, we could still discern general themes over which unexpected consensus existed. The following six interrelated effects emerged:

Time-variable training requires flexible planning.

Learners must be active and engaged.

Accelerated learning sometimes comes at the expense of clinical expertise.

Fast-track training for gifted learners jeopardizes the continuity of care.

Dedicated time for supervision is needed.

Hospital boards should support time-variable CBME.

Time-variable training requires flexible and individual planning

It was a common procedure for clinical teachers in all departments to assess the trainee’s level of professional competence at the start of the training so as to be able to construct an individualized training program. As some trainees needed less time to achieve the required level of competence, the teachers personalized the program accordingly, during or at the end of the program, by offering the opportunity to do more research or to achieve extra learning objectives, for example. In the words of clinical teacher 1: “In practice, the individualized program is decided at the beginning of the training […] that a part that is normally part of the training will not be provided this time.”

Learners must be active and engaged

It was through interaction with their clinical teachers that trainees’ individual trajectories ultimately took shape. While at the beginning of the training previously gained experience and competencies were the key determinants, feedback conversations played an important role later on in the program. Hence, if trainees wished to have any say in the adjustment of their training program, they had to be able to actively communicate their learning and development preferences to their critical judges, i.e. the clinical teachers. This made self-managing capabilities and pro-active behavior essential assets, as the following quote illustrates:

That is a more self-managing attitude: ‘thinking for yourself about the next steps and how this can be planned in a way that I can do that’ instead of coming to me and saying that you want more time in the operation theatre. I much more appreciate it when people who come to me and explain their needs […] have already looked at the schedule for opportunities and want to discuss those. (Clinical teacher 15).

Accelerated learning sometimes comes at the expense of clinical expertise

Most participants emphasized the importance of clinical immersion. In PGME, trainees have traditionally played a central role in the clinical process, and learned while executing clinical tasks. Because of this there is not always a clear distinction between work and training. They start under close supervision and progress to increasing independence. Accelerated learning trajectories sometimes resulted in reduced clinical immersion, curtailing vital opportunities to acquire clinical expertise. Hence, in order to become a competent physician, spending sufficient time in patient care remained an absolute necessity. The following quote reflects this view:

‘Well, this moment arrived at the end of the training. We had the impression that the trainee had experienced too little exposure to clinical practice, resulting in an insufficient sense of responsibility towards the patients’. (Manager 12).

Fast-track training jeopardizes the continuity of care

Unlike traditional PGME curricula that are structured around fixed units that take place during specific parts of the program, time-variable programs allow gifted learners who prematurely reach the desired level of competence to move on to the next part of the program. As becomes clear from the quote below, such an approach frustrates the organizational structure, jeopardizing the continuity of care:

Well, you tell me. For instance, a trainee working in the emergency department finishes after three months instead of four. Congratulations, you are very good. And the emergency department now has to deal with being understaffed for a month. […] If you do it like that […] that you let people start an internship and then shorten the duration of the internship if they acquire the required level of competence earlier, then hell breaks loose! Because then you adapt the programme along the way. To be honest, I do not see a solution to that problem. (Clinical teacher 1).

Dedicated time for supervision is needed

Participants indicated that clinical teachers often juggled multiple responsibilities. Not only were they involved in teaching, but they also participated in other activities such as clinical service delivery, management tasks and research projects. This made for a delicate balancing act and compromises in terms of time allocation. For example, for most clinical teachers, providing supervision caused a delay in clinical service. The switch to time-variable training programs aggravated this problem, since it shifted the emphasis of supervision more strongly towards continuity and direct formalized point-of-care feedback which was also more time-consuming. The introduction of time-variable education, therefore, affected the time allocation of clinical teachers:

We all had our own filled consulting hours, […] supervised trainee consultations and the delivery rooms. In the outpatient clinic, outpatient contacts were less tightly planned, which, as a side effect, led to longer waiting times for a given number of patients. All the same, they [trainees] often stood in rows in the hallway. (Manager 6).

Some participants even spoke of an impasse, since to be able to provide feedback, they needed to be available; in order to make time available, they needed more experienced trainees to take over some of their attending work; however, this was not always possible as the more gifted learners had often aborted clinical service to embark on a more advanced stage of training. One manager expressed this sentiment: “every part of modern education takes time. A lot of time, we are giving feedback until we are groggy.” (Manager 4).

Hospital boards must support time-variable CBME

All participants regarded PGME as an important mission of teaching hospitals, especially so since having a PGME program was alleged to lead to a higher quality of clinical care. In their perception, hospital boards also shared this view and took the delivery of a high-quality PGME program very seriously, as a clinical teacher explained: “Otherwise we are just a plain production hospital. And we do not want to be that. The board does not want that either.” (Clinical teacher 1).

Yet, the introduction of time-variable education sparked tensions between hospital departments and their supervisory boards. Since most hospital units operated autonomously, they made their own estimates of staffing and output delivery. Uncertainty about the availability of both trainees and clinical teachers introduced by time-variable education rendered this job complex, while hospital boards, acting as watchdogs, merely added to this pressure:

The other issue is whether we [the department] can balance our budget. And then we have our research tasks, mainly research. And yes, as long as it all runs smoothly no one notices anything […] but when it goes wrong, they [the management] know how to find us. (Clinical teacher 19).

One way to overcome the problem of varying trainee availability and to ensure the continuity of care was to assign certain clinical tasks the trainee would normally have performed to other professionals, a policy called task reallocation. Nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or hospitalists, for instance, could take over some of the trainees’ work, even though they did not have the same qualifications as advanced trainees did. This strategy, however, provided only a partial solution to the challenges brought by time-variable training, as the appointment of extra staff caused additional budgetary stress, heightening tensions between department and hospital board even further.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the effects of time-variable and individualized CBME on the organization as perceived by clinical teachers and department managers involved in the innovation. The thematic analysis yielded six themes, denoting relevant effects. What stood out as a major effect of the implementation of time-variable training was the pressure placed on clinical service. While on the one hand the introduction of time-variable education called for a more demanding role of clinical teachers, on the other hand, it enabled trainees to abort clinical service upon achieving the desired competencies. As a result, clinical teachers faced the almost impossible task to provide feedback more frequently and in a less planned fashion, while they could rely less on trainees taking over their clinical tasks, which undermined the continuity of patient care. In this case, the innovation did not just have repercussions on the educational system, but adversely affected (Rogers Citation2003) other organizational levels as well. This finding ties in nicely with the notion that teaching hospitals are complex organizations that consist of multiple interacting systems (Plsek and Greenhalgh Citation2001; van Rossum et al. Citation2016). Hence, plans to implement educational innovations should make provision for the eventuality that their execution has unforeseen effects.

Another observation, albeit indirect, was that nearly all individual trajectories were tailored to the trainee’s level of competence at the commencement of training, but were not adjusted along the way. Hence, the legacy of the previous modular and time-based programs was still felt, as users experienced difficulties in breaking with former working procedures. In other words, rather than being implemented according to its original plan, the innovation was being shaped and redesigned by its users. From this, we may conclude that user readiness, indeed, plays an important role in an innovation’s rollout, as Rogers was already keen to point out: users are not mere passive recipients, but are actively altering the innovation to make it fit in the organization’s structure (Rogers Citation2003).

Finally, we observed no major differences of opinion between clinical teachers and department managers. A plausible explanation for this could be that the departments of these teaching hospitals attached great importance to education and PGME. Although we did not explore this in depth, both groups felt highly involved with education. Yet, it may seem obvious that not only clinical teachers, but equally the management of the hospital experienced difficulties from the introduction of CBME.

Practical implications

This study has demonstrated that the effects of implementing time-variable curricula may extend beyond the educational program, spilling over into other levels in the organization as well. In practice this means not only that time-variable curricula affect the organization of both teaching hospitals and clinical service but also that multiple organizational barriers complicate their implementation. Hence, to render the implementation of time-variable training successful, service provision should be more flexible adjusted to education. Moreover, the scheduling and staffing problems that ensue should be managed adequately and more flexible to maintain a favorable learning environment facilitating learners who leave rotations early. A final implication of the new insights gained from the study at hand is that efforts should be directed at training clinical teachers to cope with this new teaching method and at critically evaluating the effects of teachers’ new role on workplace-based education, so that the pros and cons of this innovation can be carefully weighed.

Strengths and limitations

The transition to time-variable PGME programs is a very recent development, and, to our knowledge, this is the first empirical study to explore the effects of this innovation on the organization of teaching hospitals. The fact that we collecting data from multiple specialities and different types of hospitals can be considered a strength, as it enhanced the generalizability of our results. Although the goal of our analysis was to include a wide variation of cases, and therefore yielded a wide variety of themes and in-depth information about the effects of time-variable training on the organization, theoretical saturation was not a main goal of this study. It should be borne in mind that, the innovation still being in its infancy, effects may change over time, some of them becoming more pronounced, while others may fade.

Further research

The present study into the effects of introducing time-variable PGME programs identified several areas of interest that deserve further scrutiny in future studies. One major question that remains unanswered is how higher management and policymakers can ensure an impeccable embedment of educational innovations in clinical service. And how the relation between clinical teacher and department manager can influence the implementation and adoption of educational innovations. Additionally, we welcome research into trainees’ position and role in time-variable CBME, particularly their approaches to learning and relationship with their clinical teachers. Furthermore, the results of this explorative study showed no major differences between academic and non-academic departments and between smaller and larger sized departments. Further research should focus on these differences. A final fundamental topic we invite future research to address is the balance between the benefits and unintended consequences of time-variable training.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the introduction of time-variable training causes collateral damage, raising the question of whether its educational benefits outweigh the burden imposed on the organization. While the scientific world is looking for the answer, teaching units are finding their ways to cope with emerging issues, sometimes by altering the innovation’s original intent.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethical review board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO-ERB; file number 549). The work was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Notes on contributors

Tiuri R. van Rossum, MSc, is a researcher and lecturer at the School of Health Professions Education (SHE), Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Fedde Scheele, MD, PhD, is a Professor at the Athena institute, VU University and School of Medical Sciences of the VU University medical centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and practices gynecology at the OLVG Teaching Hospital, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Henk E. Sluiter, MD, PhD, is a manager of postgraduate medical education, Deventer Hospital, Deventer, The Netherlands, and practices internal medicine in the department of internal medicine and nephrology, Deventer hospital, Deventer, The Netherlands.

Emma Paternotte, MD, PhD, practices gynaecology at Meander Medical Center, Amersfoort, The Netherlands.

Ide C. Heyligers, MD, PhD, is a Professor at the School of Health Professions Education (SHE), Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands, and Orthopaedic surgeon and manager of postgraduate medical education at Zuyderland medical centre, Heerlen, The Netherlands.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Angelique van den Heuvel and Lisette van Hulst for their writing assistance.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Billett S. 2005. Constituting the workplace curriculum. J Curriculum Stud. 37:1–15.

- Carraccio C, Wolfsthal SD, Englander R, Ferentz K, Martin C. 2002. Shifting paradigms: from Flexner to competencies. Acad Med. 77:361–367.

- Englander R, Frank JR, Carraccio C, Sherbino J, Ross S, Snell L, Collaborators I. 2017. Toward a shared language for competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 39:582–587.

- Frank JR, Snell LS, Ten Cate O, Holmboe ES, Carraccio C, Swing SR, Harris P, Glasgow NJ, Campbell C, Dath D. 2010. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 32:638–645.

- Glaser GG, Strauss AL. 1967. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New Brunswich (U.S.A.) and London (U.K.): Aldine Transaction.

- Greenhalgh T, Hinder S, Stramer K, Bratan T, Russell J. 2010. Adoption, non-adoption, and abandonment of a personal electronic health record: case study of HealthSpace. BMJ. 341:c5814.

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. 2004. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Quarterly. 82:581–629.

- Greenhalgh T, Stramer K, Bratan T, Byrne E, Mohammad Y, Russell J. 2008. Introduction of shared electronic records: multi-site case study using diffusion of innovation theory. BMJ. 337:a1786.

- Harden RM, Crosby JR, Davis MH. 1999. AMEE guide no. 14:outome-based education part1 – an introduction to outcome-based education. Med Teach. 21:7–14.

- Holmboe ES, Sherbino J, Englander R, Snell L, Frank JR, Collaborators I. 2017. A call to action: the controversy of and rationale for competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 39:574–581.

- Jippes E, Van Luijk SJ, Pols J, Achterkamp MC, Brand PLP, Van Engelen JML. 2012. Facilitators and barriers to a nationwide implementation of competency-based postgraduate medical curricula: a qualitative study. Med Teach. 34:589–602.

- Laeeq K, Weatherly RA, Masood H, Thompson RE, Brown DJ, Cummings CW, Bhatti NI. 2010. Barriers to the implementation of competency-based education and assessment: a survey of otolaryngology program directors. Laryngoscope. 120:1152–1158.

- Lillevang G, Bugge L, Beck H, Joost-Rethans J, Ringsted C. 2009. Evaluation of a national process of reforming curricula in postgraduate medical education. Med Teach. 31:e260–e266.

- Long DM. 2000. Competency-based residency training: the next advance in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 75:1178–1183.

- Lurie SJ, Mooney CJ, Lyness JM. 2009. Measurement of the general competencies of the accreditation council for graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 84:301–309.

- Martin M, Vashisht B, Frezza E, Ferone T, Lopez B, Pahuja M, Spence RK. 1998. Competency-based instruction in critical invasive skills improves both resident performance and patient safety. Surgery. 124:313–317.

- Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. 2001. Complexity science: the challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ. 323:625–628.

- Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. 2000. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 320:114.

- Ringsted C, Hansen TL, Davis D, Scherpbier AJJA. 2006. Are some of the challenging aspects of the CanMEDS roles valid outside Canada? Med Educ. 40:807–815.

- Ringsted C, Østergaard D, Van der Vleuten CPM. 2003. Implementation of a formal in‐training assessment programme in anaesthesiology and preliminary results of acceptability. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 47:1196–1203.

- Rogers EM. 2003. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press.

- Savin-Baden M, Major CH. 2012. Qualitative research: the essential guide to theory and practice. London: Routledge.

- Scheele F, Teunissen P, Van Luijk S, Heineman E, Fluit L, Mulder H, Meininger A, Wijnen-Meijer M, Glas G, Sluiter H. 2008. Introducing competency-based postgraduate medical education in the Netherlands. Med Teach. 30:248–253.

- Ten Cate O, Scheele F. 2007. Competency-based postgraduate training: can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad Med. 82:542–547.

- van der Lee N, Fokkema JP, Westerman M, Driessen EW, van der Vleuten CP, Scherpbier AJ, Scheele F. 2013. The CanMEDS framework: relevant but not quite the whole story. Med Teach. 35:949–955.

- van Rossum TR, Scheele F, Scherpbier AJ, Sluiter HE, Heyligers IC. 2016. Dealing with the complex dynamics of teaching hospitals. BMC Med Educ. 16:1.

- Wasnick JD, Chang L, Russell C, Gadsden J. 2010. Do residency applicants know what the ACGME core competencies are? One program’s experience. Acad Med. 85:791–793.

- Watling CJ, Lingard L. 2012. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 70. Med Teach. 34:850–861.

- Wong CA, Davis JC, Asch DA, Shugerman RP. 2013. Political Tug-of-War and pediatric residency funding. N Engl J Med. 369:2372–2374.