Abstract

This guide provides an understanding of what teacher identity is and how it can be developed and supported. Developing a strong teacher identity in the context of health professions education is challenging, because teachers combine multiple roles and the environment usually is more supportive to the identity of health practitioner or researcher than to that of teacher. This causes tensions for those with a teaching role. However, a strong teacher identity is important because it enhances teachers’ intention to stay in health professions education, their willingness to invest in faculty development, and their enjoyment of the teaching role. The guide offers recommendations on how to establish workplace environments that support teacher identity rather than marginalise it. Additionally, the guide offers recommendations for establishing faculty development approaches that are sensitive to teacher identity issues. Finally, the guide provides suggestions for individual teachers in relation to what they can do themselves to nurture it.

Introduction

I really want to hold on to my role as a doctor. […] And when I’m standing at a bedside to teach students how to examine patients, I do feel that I’m a doctor. I don’t see myself as a teacher then. (Van Lankveld et al. Citation2017a)

When we make decisions about where to invest our professional time, we either implicitly or explicitly take into consideration our understanding of who we are and who we would like to be. In other words, our professional identity. When we talk about our work, we present ourselves in a certain way and thus construct a professional identity. When we justify ourselves or align with certain professional groups, we do this in the light of our understanding of who we are, or would like to be, and by doing so, we also manage others’ impressions of who we are and thus negotiate a professional identity.

Practice points

Teacher identity is defined as a teacher’s understanding of him- or herself as a teacher. It concerns questions like: Do teachers see and present themselves as a teacher? Do they feel emotionally attached to their role? What kind of teacher do they consider themselves to be, present themselves to others and would they like to be?

Supporting teacher identity is important, since identity serves as an organising element in teachers’ professional decision making.

Many teachers in health professions education see teaching as an important part of their identity. However, many of them also feel marginalised, given that teaching lacks prestige and recognition when compared to patient care and research. This causes tensions for those who see themselves as teachers.

Currently many workplaces are not very supportive of a distinct and strong teacher identity. It is therefore important to improve this and support teacher identity.

For this purpose, this AMEE guide offers recommendations to support teacher identity, both in the workplace context and in faculty development activities.

The question for teachers in health professions education (HPE) is, however, to what extent being a teacher is an important part of their professional identity. The teacher in the excerpt above, though spending about 95% of her professional life on teaching, does not see herself, nor present herself to others, as a teacher, but rather as a clinician. Teachers in HPE often combine several roles; they not only are teachers, but also clinicians or researchers. For some, the teacher role is an important part of their identity, but for others, the clinical or researcher roles are much more central.

Whether or not these individuals see themselves as teachers, present themselves as teachers to others and are emotionally attached to their teaching role, are the questions central to teacher identity. It is important to strengthen HPE teacher identity, since research has shown that many teachers feel their role is seen by others as subordinate to the more valued roles of researcher and clinician (Sabel and Archer Citation2014; Hu et al. Citation2015; Van Lankveld et al. Citation2017a). Yet, those who more strongly identify with the teaching role differ from those who do not in terms of their intention to stay in HPE, their willingness to invest in their professional development as teachers, and their enjoyment of the teaching role (Beauchamp and Thomas Citation2009; Trautwein Citation2018).

Purpose of the guide

This central goal of this guide is to offer recommendations on how to support and strengthen teacher identity. The guide summarises what teacher identity is, how it is conceived of in the academic literature, what is known about teacher identity in HPE, and particularly, how it can be supported and enhanced. The guide aims to enrich our understanding of what teacher identity is and what we can do to nurture it. The guide offers recommendations on how to establish both workplace environments that support teacher identity rather than marginalise it, and faculty development approaches that are sensitive to teacher identity issues.

Contemporary conceptions of teacher identity

What is teacher identity?

In the educational literature, teacher identity is defined as a teacher’s understanding and presentation of him/herself; it concerns whether teachers conceive of themselves as a teacher, whether and how they feel emotionally attached to the teacher role, the kind of teacher they consider themselves to be and would like to be, and as such present themselves to others (Beijaard et al. Citation2004; Holland and Lachicotte Citation2007).

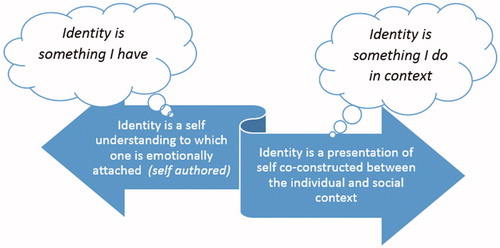

Identity can be understood as a continuum between an individual feature of a person and a relational phenomenon. On the one side of the continuum are scholars who see teacher identity as something a person has, as a way teachers conceive of themselves as teachers (i.e. Beijaard et al. Citation2004). On the other side of the continuum are those scholars who see teacher identity as something teachers do, as a way they present themselves during social interactions in response to others’ impressions of themselves (Sfard and Prusak Citation2005; Akkerman and Meijer Citation2011). In our view, identity includes both. It can be seen as both an understanding and as a presentation of oneself, shaped and reshaped in constant dialogue between a person and their social environment ().

Identity as an organising element

Teacher identity is thought to be a critical organising element in a teacher’s professional life (Beauchamp and Thomas Citation2009). It shapes what teachers find important within their context, what they get enthusiastic about, and what they get upset about when threatened. Identity is strongly related to professional commitments, ideals, interests, beliefs and values, ethical standards and moral obligations (Eteläpelto et al. Citation2014). Teachers interpret the past, present and future, value themselves and others, and make choices about how to act, in light of their identity (Beauchamp and Thomas Citation2009; Steinert et al. Citation2019). In other words: identity serves as a source of meaning and organising element in teachers’ professional lives. Identity is ‘a resource that people use to explain, justify and make sense of themselves in relation to others, and to the world at large’ (Beauchamp and Thomas Citation2009).

Developing teacher identity

Current conceptions of teacher identity portray teacher identity not as stable, but as shifting and dynamic and as a product of a constant dialogue between one’s inner self and the multiple social, political, cultural and institutional contexts in which it is engendered and performed (Rodgers and Scott Citation2008; Beauchamp and Thomas Citation2009; Monrouxe Citation2010).

Particularly in narrative approaches to identity, much attention is given to the ways teachers present themselves in their stories about teaching (Søreide Citation2006). In telling stories about what it is like to be a teacher, teachers actively position themselves vis a vis others and thus negotiate a teacher identity (Sfard and Prusak Citation2005). Through these narrative resources, they manage others’ and their own impressions of themselves; not only of who they are, but also of who they are not or would (not) like to be (Monrouxe Citation2010). Narrative approaches to identity acknowledge that in this ongoing dynamic process of storied self-presentation, multiple identities can be involved, relating to different professional roles, backgrounds, contexts or situations. Depending on the situation one is in, teachers might see and present themselves differently. These different identities might sometimes conflict with each other, which might lead to tensions for the teachers involved.

In sociocultural approaches to identity, attention is paid to the social, cultural, historical and institutional contexts in relation to which teachers realise their work (Holland and Lachicotte Citation2007). Teachers construct and enact their identity not in isolation, but in continuous dialogue with the ways their role is recognised, supported and rewarded by other people in their workplace contexts (Hermans and Hermans-Konopka Citation2010; Hermans and Gieser Citation2012). The beliefs and messages told about teaching in these contexts may become a lens through which teachers come to evaluate and see themselves (Holland et al. Citation1998). What matters for teachers, therefore, is the degree to which their identity is nurtured by members of their own community and the degree to which it is validated by other communities (Penuel and Wertsch Citation1995). Academic and workplace contexts make certain identities more possible and marginalise others. As teachers participate in multiple contexts, the messages revealed in these different contexts may be sometimes contradictory and conflicting, leading to tensions in teachers’ identity.

In this paper, we base our recommendations for supporting HPE teacher identity on both narrative and sociocultural perspectives of identity. We acknowledge the vital structuring effects of the different contexts in which teachers in HPE participate and the tensions that may arise as a consequence of these different contexts, as pointed out by socio-cultural theory. We also pay attention to the narrative resources that teachers use as building blocks for constructing a teacher identity.

Developing a teacher identity in health professions education

Literature on teachers in HPE shows that many HPE teachers see teaching as an important part of their identity. These teachers feel responsible to teach and feel satisfied that they can contribute to students’ growth and development (Hu et al. Citation2015; Steinert and Macdonald Citation2015). However, many of them also report tensions in their identity; they particularly feel that education is often viewed by others as additional or accessory to the more discursively valued roles of clinician or researcher (Sabel and Archer Citation2014; Van Lankveld et al. Citation2017a). They feel that clinical work and research productivity are often more valued than teaching, and that teaching lacks prestige and recognition when compared to patient care and research (Kumar et al. Citation2011; Brownell and Tanner Citation2012; Bartle and Thistlethwaite Citation2014; Sabel and Archer Citation2014; Hu et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, teachers in HPE report a lack of dedicated time for educational activities (De Cossart and Fish Citation2005; Budden et al. Citation2017). It thus seems the case that the context in HPE is usually more supportive to the identity of health practitioner or researcher over that of teacher (Cantillon et al. Citation2019). There is in effect a hidden curriculum in many workplace settings that undermines teacher identity. This causes tension for those who see themselves as teachers; these teachers report feeling marginalised and lacking self-esteem (Kumar et al. Citation2011, Sabel and Archer Citation2014; Hu et al. Citation2015; Van Lankveld et al. Citation2017a).

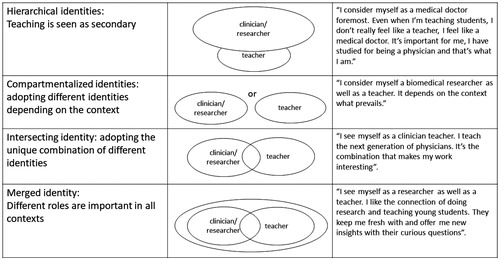

As many teachers in HPE often combine several roles, they have to consider these different roles in their identities. The recent literature shows that teachers do this in different ways (see ). Some see their teaching role as secondary to their primary role of care provider or researcher (Dybowski and Harendza Citation2014; Sabel and Archer Citation2014; Van Lankveld et al. Citation2017a). Like the teacher in the excerpt we started this guide with, these teachers see themselves as clinician or researcher first and foremost, even though they do take on formal educational roles. Other teachers, on the other hand, see their different roles of care provider, researcher and teacher as compartmentalised (Roccas and Brewer Citation2002). Depending on the context, they alternatively see themselves as teacher, researcher or care provider. Others again, see their different roles as intersecting or merged (Cantillon et al. Citation2019). These teachers find both roles important, and either stress the unique combination of those roles (intersecting) or attribute equal importance to both roles, regardless of the context (merged). It is the teachers in the two latter groups who experience less tensions and who are more likely to see positive connections between the different roles. For example, these teachers hold that expertise in clinical practice reinforces their credibility as a teacher (Davies et al. Citation2011) or that having a formal educational role enhances their status amongst clinical peers (Lake and Bell Citation2016). Other positive connections between the different roles concern strongly holding the view that being a physician implicitly also means being a teacher, or seeing the development in one role as positively impacting on the other (Steinert and Macdonald Citation2015; Van Lankveld et al. Citation2017a).

Figure 2. Variety of ways in which teachers juggle their different identities. (based on data from an earlier study (Van Lankveld Citation2017))

In summary, developing a teacher identity in academic and clinical workplace settings is challenging by nature of the multiple roles teachers in HPE have. It is even more problematic since many workplaces are not very supportive of a distinct and strong teacher identity. This leads to tensions in their teachers’ identity and to hierarchical and compartmentalised identities. Instead, intersecting and merged identities are preferable, since, as explained earlier, individuals with a strong identity as a teacher enjoy their teaching role more, are more likely to stay in health professions education, and are more willing to invest in their professional learning. It is therefore important to support teacher identity, both in workplaces and in faculty development. In workplaces, it is important to engender a more conducive workplace environment for the development of intersecting and merged identities. Additionally, it is important to establish faculty development approaches that are sensitive to teacher identity issues and that enhance teacher identity. In the rest of this paper, we will provide recommendations to do so.

Supporting teacher identity

In this section, we provide recommendations for supporting teacher identity of teachers in HPE. We distinguish between the workplace context and the faculty development context. This distinction between the two environments is based on the insightful work of O’Sullivan and Irby (Citation2011), who argue that both workplaces and faculty development influence the professional learning of teachers in the health professions. We have used O’Sullivan and Irby’s distinction between workplace and faculty development to classify our recommendations. Within the workplace context, O’Sullivan and Irby describe four influential components:

(1) The institution with its associated systems and culture;

(2) The nature and content of the work that teachers do;

(3) The relationships and networks that teachers engage in;

(4) The mentoring and coaching that teachers have access to.

We have used this distinction in four components to further classify our recommendations concerning the workplace. In O’Sullivan and Irby’s model, these four influential components are distinct, but in practice they are very much interrelated. We will provide recommendations concerning the workplace first, before we continue with providing recommendations concerning faculty development. Most of the recommendations are based on evidence from the literature on teacher identity in HPE, whilst some are derived more indirectly from the literature on teacher identity in general. Throughout both sections, we have added boxes with examples from practice, further suggestions for realising the suggestions, and suggestions for individual teachers. Recommendations may need to be adapted to the specific contexts and cultures of the local institutions, depending on the local structures and the resources available.

Box 1 Recommendations for supporting teacher identity

Recommendations for the workplace:

Recognise and reward teaching in career frameworks.

Acknowledge teaching excellence in grants and awards.

Support a positive message about teaching.

Take a deliberate and proactive approach to new teacher development.

Minimise the conflict created by competing demands.

Ensure that all teachers are provided with the knowledge and skills needed for their specific teaching role(s).

Establish formal or encourage informal teacher networks and communities.

Encourage teachers to join local or national medical education organisations.

Provide (novice) teachers with opportunities to observe teaching activities of (more experienced) colleagues.

Utilise peer mentoring

Utilise coaching through reflective practice.

Recommendations for faculty development:

Encourage storytelling about teaching.

Reinforce appreciative and positive stories about teaching and about connections between teaching and other roles.

Facilitate teachers to reflect on their teaching role, its meaning for them, and their underpinning values, beliefs and motivations.

Be sensitive to the context teachers work in.

Stimulate the building of social relations and support networks.

Establish a longitudinal and continuing approach to teacher development.

Recommendations for the workplace

The institution with its associated systems and culture

As teacher identity is shaped by the normative and cultural context of the host institution with its associated systems and culture (Kumar and Greenhill Citation2016), it can be supported by fostering an institutional culture that through its incentives for teaching and the enacted values of the organisation, is positive towards teaching and learning. Below we provide three relevant recommendations for doing so.

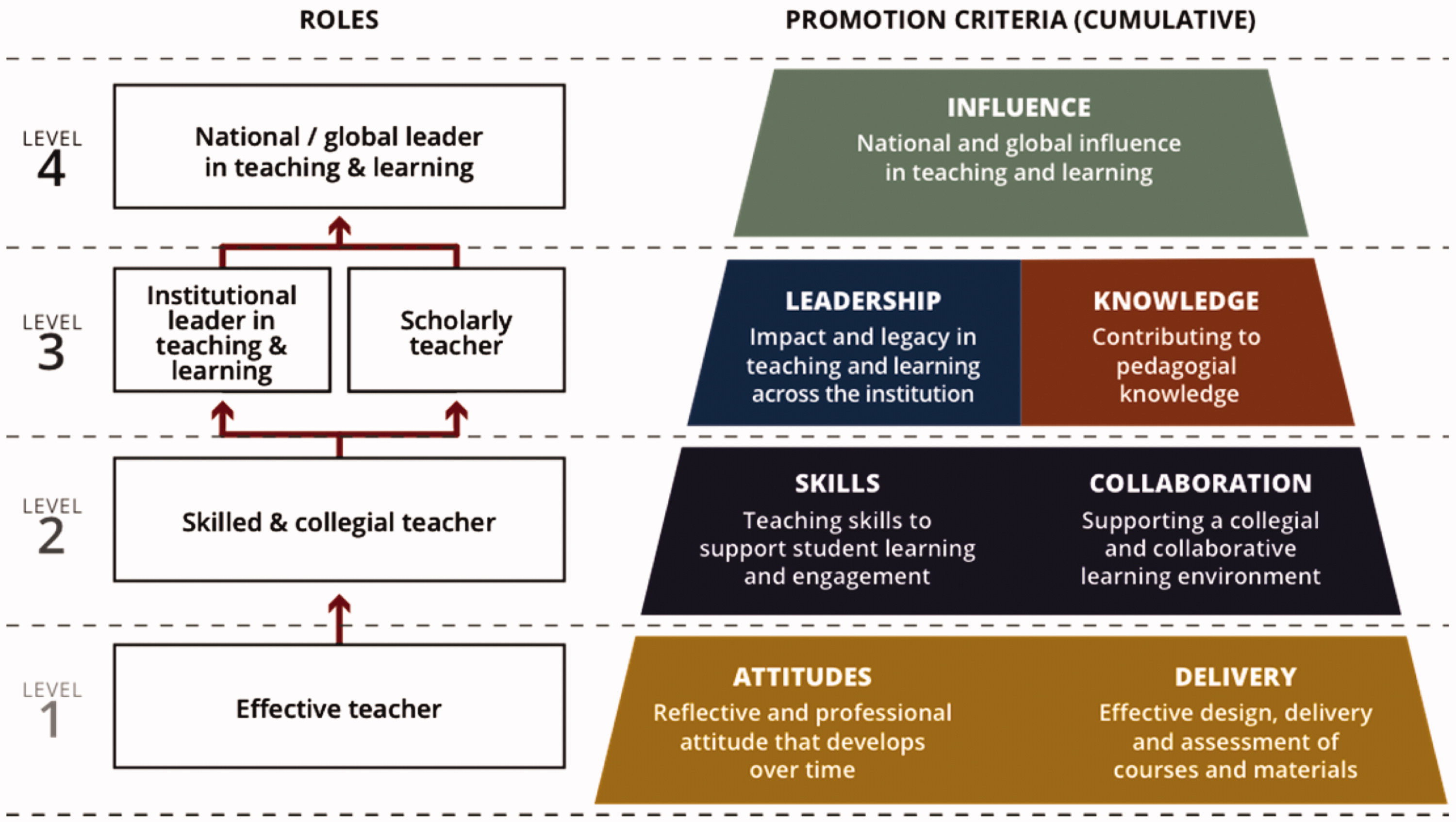

Recommendation 1: Recognise and reward teaching in career frameworks

Although literature points to the value of formal recognition and reward of the teacher role in establishing an institutional culture positive to teaching, at many universities teaching credentials are not or only weakly used as basis for promotion (Kumar et al. Citation2011; Paslawski et al. Citation2013; Steinert and Macdonald Citation2015). Career frameworks help in validating the teacher identity (Kumar and Greenhill Citation2016). A career framework enables teachers and their supervisors to better recognise teaching achievements and reflect on a teacher’s development. Several authors show that these frameworks should address the full breadth of teaching roles: not just delivery, but also design, assessment, management/leadership, scholarship and own professional development, thus acknowledging and valuing the full breath of teaching-related activities (Graham Citation2018; Harden and Lilley Citation2018). It is important that formal policies to recognise teaching are applied in practice, else it risks conveying a hidden message that contradicts or undermines the original intentions (Cox et al. Citation2011; Hafler et al. Citation2011).

Suggestions for organisations

Institutions that want to increase recognition of teaching in academic careers could lead an institutional discussion to adopt a teaching framework to make teaching achievement explicit in an academic career.

Possible steps could be:

Take an existing teaching framework as starting point. One example is the Career Framework for University Teaching (Graham Citation2018), see figure below, but many other frameworks exist like the UK professional standards framework (HEA Citation2011), or the AAMC Toolbox for Evaluating Educators (Gusic et al. Citation2013).

Discuss with a broad range of stakeholders how such a framework could translate to the own institution:

What would promotions criteria look like for the different levels in your institution?

Which forms of evidence could you think of in your context?

How should teaching achievements be weighed against the other tasks in an academic career?

Figure: Graphic representation of the Career Framework for University Teaching (Graham Citation2018). Reprint with permission.

Figure: Graphic representation of the Career Framework for University Teaching (Graham Citation2018). Reprint with permission.

Suggestions for teachers

• When writing your CV, yearly evaluation report, or other accounts of your academic performance, make sure to mention your educational activities and achievements. Take into account your education roles in full breath: including for instance innovation projects, educational products, committees, awards, invited lectures, etc.

• Use these data to map your development on a framework and reflect on your current positioning and future ambitions as a teacher together with your supervisor and/or mentors.

Recommendation 2: Acknowledge teaching excellence in grants and awards

Incentives like teaching awards and educational innovation or scholarship grants enact the idea that outstanding and/or innovative teaching is appreciated and valued and help enthusiast, active teachers to stand out and build cases for promotion. As such, grants improve HPE teachers’ status among their colleagues in their departments, enhance their careers, and lead to local or even national recognition (Adler et al. Citation2015). Further, receiving an award validates ones teacher identity, improves teachers’ self-confidence, and builds their reputation (Skelton Citation2012; Fitzpatrick and Moore Citation2015). It is important though, that teaching awards are not the only instruments used to establish a workplace culture that is positive towards teaching, since in that case they risk being interpreted as lip service only (Skelton Citation2012). Nevertheless, grants and awards can play an important symbolic function in establishing a positive workplace culture towards teaching and learning because they convey a message that teaching is important.

Example

In the Netherlands, the national government recently started to award 66 Comenius grants on a yearly basis for educational innovation to teachers in higher education, in three levels ranging from 50.000 to 500.000 euro. The grants allow teachers to bring their educational vision to practice and build a career in educational innovation. Besides these national grants, several Dutch universities have their own educational incentive funds installed to support teachers in educational innovation.

Suggestions for organisations

As far as teaching awards are concerned, the literature gives the following advice (Huggett et al. Citation2012; Newton et al. Citation2017):

Make sure to use fair and transparent criteria.

Consider a jury for granting the awards, consisting of students, peer teachers as well as experts in the field of education.

Do not only award individual teachers, but also teaching teams.

Prevent the ‘usual suspects’ to dominate the awards, by carefully considering to award good teaching in its full breadth, e.g. most innovative teaching team, best improved 1st year course, most enthusiastic new teacher, most innovative course, exam that yielded strongest learning outcomes, best educational leadership, etc.

Publicise the awards widely such that not only winners, but also nominees get broad recognition, as well as the department and colleagues of the winners, for being the context that supported them in their teacher development.

Ensure active participation of top leadership and students in the awards ceremony since this shows serious involvement of the institution.

Embed the awards in the institution’s quality assurance policy, as well as in the institution’s system of promotion and tenure.

Suggestions for teachers

Look for opportunities for grants and awards. Apply yourself or encourage colleagues to do so.

Participate in panels or committees awarding grants or awards: you will enlarge your network, gain insight in what is excellent teaching or educational innovation, and build your own teaching CV at the same time.

If opportunities do not yet exist in your institution or department, take initiative to start an award. Little more is needed than enthusiasm.

Recommendation 3: Support a positive message about teaching

Apart from the formal institutional policies, it is particularly the informal organisational culture with the stories and narratives told about teaching that teachers are sensitive to (Cantillon et al. Citation2019). Stories that teachers, colleagues and managers tell, convey implicit underlying messages about how teaching is being valued (Van Lankveld et al. Citation2017a). Particularly those in leading positions such as deans, managers and department leaders, should be aware of the stories they tell in public about teaching, research and clinical work and the underlying message they reveal. A deliberate policy of including positive or innovative teaching narratives in organisational gatherings (e.g. conferences) and communication strategies, (e.g. websites and newsletters) can play a key role in positioning teaching as equally valued compared with research and healthcare practices.

Suggestions for organisations

In both formal and informal communication (e.g. newsletter, social media, new year speech, etc) devote equal attention to teaching, clinical, and research achievements.

In ‘facts & figures’ (e.g. in year report) mention not just teaching volume and student satisfaction but also (numbers of) other teaching achievements such as innovations, awards and grants.

Suggestions for teachers

Actively seek opportunities to provide input for news items about your teaching activities:

Write a blog about your teaching experiences.

Ask your institute’s communication department whether they are interested in a remarkable student learning experience, an interview about you as a teacher, an educational innovation, a teaching award or grant, or anything else that could put your or your colleagues’ teaching in the spotlights.

The nature and content of the work that teachers do

The nature and content of the work that participants do at the workplace are also crucial in supporting or inhibiting professional identity (Wenger Citation1998). For teachers, it is through the opportunities to enact the teaching role and interact and build relationships with learners, that they grow and construct a teacher identity. A teacher’s practice and his or her identity are mutually linked (Akkerman and Meijer Citation2011). Below we will provide three recommendations for supporting teacher identity related to the work of HPE teachers.

Recommendation 4: Take a deliberate and proactive approach to new teacher development

Healthcare and clinical institutions are likely to derive greater benefit from new entrant teaching staff if they take a deliberate and proactive approach to teacher development. New entrants learn through experiences and engagement, as they are socialised into the norms, values and goals of the host institution (Ng et al. Citation2017). Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) concept of ‘legitimate peripheral participation’ offers a useful perspective, suggesting that newcomers legitimately start their participation at the periphery of a community. With deliberate support from and opportunities to observe more established community members, they can gain teaching skills and become more engaged (Jippes et al. Citation2013; Van Lankveld et al. Citation2016). There is also good evidence to show that new entrants’ learning is enhanced through reflection on teaching and learning experiences as well as debriefing meetings with more experienced members (Stupans and Owen Citation2010). As they move in a centripetal fashion towards fuller participation in the community, new members of the teaching team could be provided with increasing teaching responsibilities (Steinert Citation2010). With increasing experience, they can then take on more complex or advanced teaching roles. In the process of growing in their role, they adopt the values and norms of the educational community, and gain recognition and status within that community, and thus further strengthen their teacher identity (Cruess et al. Citation2018).

Recommendation 5: Minimise the conflict created by competing demands

When there is conflict in expectations and activities between workplace roles, tensions between identities can occur. These tensions can be reduced through allowing staff members to negotiate their roles rather than getting roles thrust upon them (Rodgers and Scott Citation2008). Furthermore, it is important to afford teaching activities appropriate time and resources in order to avoid teaching becoming a burdensome activity that is conducted at the expense of other work tasks (Pratt et al. Citation2006). Rather than presenting it as a low-status duty service, it is important to frame teaching as an honourable and rewarding task.

Another way to minimise the conflict created by competing demands, is to establish dedicated education units (DEUs) in university hospitals (Moscato et al. Citation2007). These are units, centres or wards that provide routine clinical care for patients, but are also regarded within the institution as a special place for clinical education. DeMeester (Citation2012), found that clinician educators participating in a DEU had a strengthened sense of teacher identity, given the opportunities to work with like-minded colleague-teachers and exchange ideas and insights. Enhanced teacher identity was sustained despite the fact that staff in the DEU had to provide the same clinical care as elsewhere in the host institution (DeMeester Citation2012). There are many guides to inform the establishment of dedicated education units, including a detailed guide by Watson et al. (Citation2012).

Suggestions for organisations

In a clinical workplace supportive of teaching, a number of measures can be implemented to minimise the conflict created by competing demands, e.g.:

Make teaching activity visible in job plans, thus emphasising the importance of this activity for the individual and colleagues.

Ensure that teaching opportunities are time-protected alongside other required duties such that each does not adversely impact on the other.

Allocate time not just for face-to-face teaching encounters but also for prior preparation and subsequent evaluation, design, assessment, and own professional development. For some, additional tasks may also include mentoring, management of education and pedagogic scholarship.

In clinical settings, modify traditional service delivery models to take into account the need to provide concurrent high quality teaching commitments for example through extending the consultation time for patients during ‘teaching clinics’ to allow extra time to facilitate enhanced supervision and learning experiences.

Suggestions for teachers

Take a proactive stance in negotiating and managing the various teaching roles and responsibilities.

Consider novel ways of distributing teaching workload amongst the team e.g. by aligning the content or complexity of teaching roles to the clinical and teaching expertise of staff members. One such model named VITAL (vertical integration in teaching and learning model) has been successfully applied in general practice in Australia where general practitioner trainees and senior students were inducted to be co-teachers with more senior colleagues (Dick et al. Citation2007).

Recommendation 6: Ensure that all teachers are provided with the knowledge and skills needed for their specific teaching role(s)

It is important that all teachers have the opportunity to formally develop their teaching practice through specific teaching skills training. As teachers build competence and confidence in teaching, their teacher identity is strengthened (Lieff et al. Citation2012; Van Lankveld et al. Citation2017c). Additionally, HPE teachers may wish to consider pursuing formal teaching qualifications. Formal certification in this way has been shown to further promote legitimisation and professionalisation of the teaching role, encourage educational practice and scholarship, improve self-efficacy and foster belonging to an educator community (Sethi et al. Citation2018).

Example

In an undergraduate medical school, all individuals who have input into the teaching of medical students are expected to undertake formal training in this area. This is achieved through:

Offering a range of faculty development workshops that cover basic teaching skills through to advanced methods.

Making faculty development workshops accessible to all involved, from junior trainees through to senior consultants and nonclinical and clinical staff members alike.

Only allowing those who have completed such training to participate in student teaching activities.

Such workshops can be used as part of building up credits towards more formal teaching qualifications such as a postgraduate certificate in healthcare education. Staff are positively encouraged to pursue this route.

Suggestions for teachers

Teaching becomes easier and more enjoyable the better you are trained in teaching skills. Therefore:

Seek out opportunities to develop your teaching abilities through attending faculty development workshops matched to your personal needs.

Formalise your teaching expertise through credentialing and certification routes such as pursuing postgraduate qualifications in teaching.

Participate in peer-review of teaching (Siddiqui et al. Citation2007).

Create and maintain an educator portfolio to help you reflect on your accomplishments as teacher and the feedback you receive from learners (Klenowski et al. Citation2006).

The relationships and networks that teachers engage in

As relationships and networks shape how people perceive themselves, educational institutions need to consider ways of enabling relationships and networks between educators to develop. In so doing, they provide a rich environment for teacher identity formation. Relationships are particularly important for new entrants to a workplace because they provide guidance on how to inhabit and perform the role of teacher (Hoffman and Donaldson Citation2004). Next to that, relationships and networks also provide teachers a sense of belonging and a feeling that they are part of a community in which their role is valued (Van Lankveld et al. Citation2017b). Additionally, relationships and networks help teachers to develop a common conceptual language in which they can communicate about their teaching experiences (Barrett Citation2013; Sabel and Archer Citation2014). The concept of relationships and networks is therefore an important consideration in supporting and enhancing teacher identity. Below we provide two recommendations for nurturing relationships and networks.

Recommendation 7: Establish formal or encourage informal teacher networks and communities

Formal or informal networks and communities provide considerable support for teacher identity (Hurst Citation2010; Steinert et al. Citation2019). By grouping together, even loosely, teachers can overcome the individualism prevalent in academic workplaces and discover others with common interests, experiences and perspectives. Established teacher role models can play a critical role, and can serve as resources to identify with, enabling younger teachers to imagine a future developmental trajectory as teacher (Kumar et al. Citation2011; Lieff et al. Citation2012; Burton et al. Citation2013; Bartle and Thistlethwaite Citation2014).

Networks and communities can be deliberately established top-down, or can grow bottom-up. Top-down established networks or communities, sometimes called academies of educators, provide spaces for teachers to share teaching experiences and practices; what Huber and Hutchings (Citation2005) termed the ‘teaching commons.’ Bottom-up approaches to networks and communities often are self-organised, less formal and looser, with teachers coming together who share a common interest or work in similar contexts (Brown and Duguid Citation2001). In order to get started, Kumar and Greenhill (Citation2016) suggest that clinical teachers could deliberately utilise their existing networks to find other teachers who share their interest in teaching and who would like to collaborate. Teachers who find each other this way could then decide their areas of common interest and how they meet, communicate and interact. From such small beginnings like-minded teachers can establish enduring informal support networks that shore up their teacher identity as well as facilitate the sharing of educational innovations and opportunities (Kumar and Greenhill Citation2016).

Suggestions for organisations

In order to get a teacher network or community off the ground, some initial steps that could be taken are presented below (based on De Carvalho-Filho et al. Citation2019), but might need adaptation to the local context and culture:

Organise work floor buy-in, e.g. by deliberately including informal educational leaders.

Try to recruit teachers with acknowledged educational expertise or people with a reputation for educational innovation.

Grow from the bottom up: encourage members to invite new members themselves.

Get started with an agreed urgent but solvable educational problem that everyone has in common. This ensures early engagement and a win-win for all participants.

Be inclusive and allow varying degrees of membership (from full members who attend everything to peripheral members who drop in occasionally).

Target recruitment via existing educational structures and events.

Approach the host institution to seek recognition, acknowledgement and support.

Suggestions for teachers

Many organisations offer educational meetings, lunches or other opportunities to meet other teachers. Participation will lead to inspiration for your teaching but most importantly also will contribute to meeting like-minded teachers. Also, it is worthwhile to find 5–7 peers who are at a similar level of experience and form a peer group that meets regularly. These peer-meetings can be used to help each other reflect on didactic and organisational issues regarding your teaching and teaching career. Many models to guide the peer-reflection process are freely available on the internet, for instance intervision (Franzenburg Citation2009).

Recommendation 8: Encourage teachers to join local or national medical education organisations

Apart from ad hoc or local networks, there are also official or organisational routes whereby teachers can develop networks of support. Teachers in the health professions could be actively encouraged to join national educator groupings, such as ANZAHPE in Australian and New Zealand, or ASME in the UK. There are also general transnational health professions education organisations such as AMEE and FAIMER (the latter supporting health professions educators in low income countries; Burdick et al. Citation2010), or those with a specific interest, such as ASPIH, The Association for Simulated Practice in Healthcare. Participation in such organisations or networks can mitigate isolation and enhance teachers’ opportunities to meet and interact with others who share areas of interest and passion.

The mentoring and coaching that teachers have access to

Mentoring and coaching programs have been shown to be an important constituent in developing a strong and resilient teacher identity (Sambunjak et al. Citation2006; Kashiwagi et al. Citation2013). Whilst careful and close mentoring can be helpful in developing skills in teaching, it can also be helpful in navigating institutional culture and providing access to networks and connections (Carey and Weissman Citation2010; Santhosh et al. Citation2020). Below we provide three recommendations for supporting teacher identity through mentoring and coaching.

Recommendation 9: Provide (novice) teachers with opportunities to observe teaching activities of (more experienced) colleagues

Experienced colleagues serve as role models for novice teachers, in that they model desired and potentially innovative practices. They also serve as a critical friend, provide emotional support, and embody a teacher identity (Dahlgren et al. Citation2006). Furthermore, they are living examples of how to deal with the complexity of teaching as part of the multiple task environment of HPE, and the potential benefits of having multiple tasks and acting in a brokering role across different practices (Van den Berg et al. Citation2017).

Suggestions for organisations

Institutional mentoring programmes can usefully support teacher identity development (Steinert et al. Citation2019). Such programmes may involve:

Assigning mentors to new and/or less experienced faculty members.

The mentor acting as a role model and having their teaching observed by the mentee.

Regular meetings to reflect on current practice and set future goals.

Furthermore, these programmes can also act as networks or communities.

Suggestions for teachers

Where institutional mentorship programmes are available, act as both a mentor and a mentee. Where such programmes do not yet exist, consider how mentoring could be used within your own practice, as well as with those you work with.

Engage with mentoring programmes offered by medical education organisations such as AMEE. Such programmes enable participants to work with a mentor from another institution to identify strengths as a teacher, as well as areas for further professional development. A mentor from a different institution or country could bring new insights to your teaching practice.

Recommendation 10: Utilise peer mentoring

Mentoring typically involves someone more experienced mentoring a less experienced colleague. Peer mentoring involves both parties acting as mentee and mentor, allowing both to benefit from both the mentoring as well as the development of skills as a mentor. Peer mentoring has been found to be a more sustainable mentoring model than traditional mentoring, and one that leads to great and longer term socialisation (Carey and Weissman Citation2010). Peer mentoring also contributes to developing a community (Santhosh et al. Citation2020) and thus supports identity development (Kalliola and Mahlakaarto Citation2011).

Recommendation 11: Utilise coaching through reflective practice

Coaching is argued to be less directive than mentoring with a focus on performance for the achievement of goals, either personal or organisational (Lovell Citation2018). Coaching can be used to strengthen teacher identity by providing opportunities for individuals to consider their professional identity development, particularly through reflective practice (Walkington Citation2005; Hökkä et al. Citation2017). Coaching type conversations focus on supporting an individual to learn and develop his or her own course of action, rather than providing advice. Coaching conversations enable individual teachers to identify goals, explore options and plan for action (Deiorio et al. Citation2016).

Suggestions for organisations

Teacher identity development can be supported through the use of coaching conversations. Coaching questions might include:

What is your goal as a teacher?

How might this be achieved?

What steps are needed to achieve your goal?

What is currently working well/not well in your teaching practice/role?

What are possible obstacles and challenges?

What does success look like?

In these conversations, career frameworks can be used (see paragraph 4.1.1), for example by supporting the mentee in relating their own professional values to these frameworks.

The identity coaching programme as described by Hökkä et al. (Citation2017) provided participants with opportunities to develop their teacher identity through coaching focused workshops. Activities included group discussions, reflective writing, drawing, and drama work. Such an identity coaching programme was found to have a positive impact on developing collective identity, empowerment and agency as teachers (Hökkä et al. Citation2017).

Suggestions for teachers

Coach yourself by using the above coaching questions in relation to your goals and how these could be achieved.

Recommendations for faculty development

Faculty development initiatives can play an important role in supporting and reaffirming teacher identity formation in HPE; it provides an environment where teachers can develop their teaching competencies, thus adding not only to their own sense of being a skillful teacher, but also making their commitment to teaching visible to colleagues, managers or potential future employers (Sabel and Archer Citation2014). It also supports teacher identity by offering narrative resources for constructing a teacher identity, like a common language in which teachers can communicate about teaching and positive stories about teaching (Lieff et al. Citation2012). Additionally, it provides an environment in which teaching is valued, and where the teaching role is acknowledged for being complex and important (Van Lankveld et al. Citation2017c). In that sense, faculty development provides an environment where teachers feel appreciated and find a sense of belonging and solidarity to a professional community (Lieff et al. Citation2012). Below we provide six recommendations for supporting teacher identity in faculty development activities.

Recommendation 1: Encourage storytelling about teaching

Storytelling about teaching experience enhances connection and communication between teachers (Huber and Hutchings Citation2005). In personal stories, teachers share professionally significant experiences, which not only helps in understanding the complexity of teaching practice, but also provides mirrors for teachers to reflect on their own (Shank Citation2006). Exchanging teaching experiences provides teachers with opportunities to position themselves vis a vis others and negotiate a teacher identity. While doing so, they not only manage others’ impressions of who they are, but also of who they are not. Telling stories thus entails negotiating one’s identity (Watson Citation2006).

Recommendation 2: Reinforce appreciative and positive stories about teaching and about connections between teaching and other roles

Faculty development is the place where positive stories about teaching can be shared that form an alternative for the prevalent negative stories. It is thus important to create opportunity for sharing these stories. Examples of such positive stories include notions of service in relation to teaching the next generation of health professionals and making a significant contribution to the patient care of the future (Steinert and Macdonald Citation2015). Other stories include notions of repaying one’s own teachers and giving something back to the healthcare profession. These elements can provide the building blocks for teachers to develop alternative stories about teaching than the ones dominant in current HPE. Particularly the stories that build on other existing identities like those of care provider or researcher are strong, as they mentally create coalitions between the multiple roles academics have and reduce tensions between these different identities and stimulate intersecting and merged identities rather than hierarchical and compartmentalised ones (Hermans and Hermans-Konopka Citation2010). Also, the satisfaction of seeing learners develop and the fun of interacting with them have been found to be strong motivators of teachers and thus can function as building blocks for alternative identity stories (Sabel and Archer Citation2014; Hu et al. Citation2015).

Suggestions for faculty development

In a faculty development activity, teachers can be stimulated to reflect on possible connections between their different roles of teacher, care provider and/or researcher by stimulating them to consider and discuss:

The importance they attribute to the different roles;

The similarities between the teaching role and their role of care provider or researcher;

The ways in which being a good teacher helps them to be a good clinician or researcher and the other way around;

The extent to which teaching is an integral part of the care provider’s or researcher’s role.

Recommendation 3: Facilitate teachers to reflect on their teaching role, its meaning for them, and their underpinning values, beliefs and motivations

Reflection has been shown to strengthen professional identity formation (Wald Citation2015; Trautwein Citation2018). In faculty development, this reflection can be stimulated in several ways. For example, it can stimulate groupwise reflection on what it takes to be a good teacher through discussing different conceptualisations of approaches to teaching (Nevgi and Lofstrom Citation2015), through collaborative investigation of video cases (Kumpulainen et al. Citation2012) or through collective discussion of shared problems and cases (Van Lankveld et al. Citation2017c). Other ways to stimulate reflection on identity entail art-based forms of reflection, in which images, photos, drawings and other artifacts are used to stimulate teachers to reflect on their memories of teachers, the way they see themselves as a teacher, and their development as a teacher over the years (Lavina and Lawson Citation2019). Finally, in the box below, we have included reflection questions that have been shown to help teachers reflect upon their role. We would like to stress however, that identity does not exclusively develop in focused reflective interventions, but develops constantly throughout all activities in faculty development, through the assembled messages that are explicitly and implicitly revealed about teaching.

Suggestions for faculty development

When stimulating teachers to reflect on their identity, it is helpful to have them reflect on the past, present and future, as well as on their self-understanding in relation to others. Helpful reflection questions to stimulate teachers to reflect on their role are:

Concerning the past:

Why did you become a teacher?

Looking back at your development as a teacher so far, how did you change?

Which past experiences have influenced you as a teacher?

What in the past helped you to grow as a teacher?

Concerning the present:

Do you consider yourself a teacher?

How important is teaching to you, compared to your other tasks?

What (according to you) is good teaching about?

What are your qualities as a teacher?

What is important to you in your contacts with students?

How does your image of an ideal teacher look like?

Concerning self in relation to others:

Do you feel part of a community of teachers?

What characterises you as a teacher compared to other teachers?

Who are role models to you, as a teacher?

Concerning the future:

What kind of teacher do you want to be in the future?

What are your goals and aspirations for the future?

What career path do you envision?

(based on: Korthagen and Vasalos Citation2005; Akkerman and Meijer Citation2011; Steinert et al. Citation2019).

Suggestions for teachers

Reflect on your identity using the questions above.

Recommendation 4: Be sensitive to the context teachers work in

Teacher identity is strongly influenced by the implicit culture and norms that prevail in the places where teachers work. Some researchers suggest the existence of a hidden curriculum in the workplace that undermines the effectiveness of faculty development (Hafler et al. Citation2011). It is vital therefore that faculty developers not only try to provide teachers with novel educational approaches, but also explore how such new learning can be realised in their learners’ workplace contexts (O’Sullivan and Irby Citation2011). Valuable approaches include facilitating learners to customise new approaches to the anticipated cultural realities of their workplaces. One way of doing this is to encourage learners to share stories about teaching practice in their workplace that reveal elements of workplace culture that need to be navigated. If time allows it is valuable for faculty developers to observe their learners in the places of work and develop teacher development approaches appropriate to the cultural landscapes that they have witnessed (Silver and Leslie Citation2009).

Recommendation 5: Stimulate the building of social relations and support networks

Social relationships represent critical determinants and supports for teacher identity (Cantillon et al. Citation2016). Faculty development can stimulate this through stimulating group work, allowing time for informal conversations during breaks and stimulating networks or special interest groups (Lieff et al. Citation2012). Additionally, one could include reflection on building one’s own support networks in the faculty development program, such as the network workshop discussed in the box below.

Suggestions for faculty development

Van Waes et al. (Citation2018) describe how brief network workshops (e.g. 45 minutes) can be included in faculty development programs, in which teachers are explicitly encouraged to develop their teaching networks:

First discuss the potential of networks to improve one’s practice.

Then ask participants to visualise their network, i.e. who they routinely consult with for educational ideas or advice, and have them reflect on the resources and expertise residing in it. Using such a reflective exercise, teachers become aware of the role of their current network in supporting their work and development as teachers.

Then ask teachers to reflect on the diversity of their network in terms of teaching experience and in terms of contacts within and outside the department and have them identify strong and weak points. They often realise at this stage that it is beneficial to reach beyond their own department (including supporting staff).

After sharing knowledge about strategies to rewire and maximise one’s network, encourage teachers to work with each other on the first steps towards expanding their existing network.

Teachers who participated in the network workshop were able to develop larger and more diverse networks over time with increased network dynamics.

Suggestions for teachers

Build your network of teachers and educational support staff, both in and outside your department, and use your network if you need advice or to test emerging ideas.

Recommendation 6: Establish a longitudinal and continuing approach to teacher development

Since relational factors are important in supporting and sustaining teacher identity, longitudinal professional development programs are more beneficial for supporting teacher identity than the episodic models that often apply (Lieff et al. Citation2012). Longitudinal programs engender greater trust between participants and therefore a stronger sense of belonging and a sense of connectedness with like-minded peers from outside their own department, with whom they share their commitment to teaching and can test new ideas (Andrew et al. Citation2009; Jauregui et al. Citation2019).

5. Concluding remarks

Teachers who have a strong teacher identity often experience greater enjoyment and meaning from teaching and are more involved in faculty development. In many workplaces in HPE however, teacher identity is hampered because of the predominant focus on clinical and research performance. Consequently, teachers may find it difficult to juggle their different roles and may see their different identities as hierarchical or compartmentalised, rather than as intersecting or merged. Thus it is important for organisations, individuals, and faculty development to pay attention to development, support and enhancement of teacher identity.

In this guide we have provided recommendations that we believe will shore up and enhance teacher identity. Some of these suggestions are relatively easy to implement and others will require considerable organisational buy-in and investment. We noted that much of the research on teacher identity in HPE is based in Western countries, in relatively resource-rich institutions. Hence, particularly in institutions with less resources, the recommendations will require adaptation to the specific context, structures, systems and culture of the local institution.

We have summarised the literature of the past decade on teacher identity within the field of health professions education. Several questions for future research still remain.

First, in the context of their work, how do HPE teachers navigate the tension between their various roles as clinicians, educators, leaders and researchers? Do they experience overlap or interaction between their respective roles, and how does that influence identity? What strategies do they develop to balance these different roles and shore up the respective role identities? And how does this develop over one’s career? How do experienced teachers sustain their teaching motivation in mid and late career?

Second, what are the consequences for teachers’ identities in relation to changes in workplace culture? In particular, in relation to systems of reward and recognition for teaching and the associated discourse with regard to the status of teaching.

Third, we welcome more research on faculty development interventions focused on strengthening teacher identity, particularly interventions for reducing the tensions between the multiple roles, and interventions to enhance teacher growth, development and identity over the course of a working life. Additionally, the development and evaluation of faculty development strategies that are more context-sensitive and workplace-based than off-site strategies would be welcome.

Fourth, as much of the research on teacher identity in HPE currently is based in Europe and Canada, we think more research in other countries is needed to find out whether teacher identity is experienced differently in different cultural contexts.

We encourage educational scholars to contribute to further understanding of these interesting topics.

Supporting teacher identity is, or certainly should be, a core focus for faculty developers and healthcare organisations with an educational mission. We think the time has come to regard the support of teacher identity as an essential value and goal for all institutions involved in health professions education.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Patricia O’Sullivan and Val Wass for providing very helpful feedback on an earlier version of this paper and Ruth Graham for giving permission to use the figure of the Career framework for University Teaching.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thea van Lankveld

Thea van Lankveld, PhD, is Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Education, Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences at Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

Harish Thampy

Harish Thampy, MB, ChB.(Hons), FRCGP, MSc. PFHEA, is Professor of Medical Education in the Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health at the University of Manchester, UK. He is the Academic Lead for Assessment for the Manchester MB ChB Programme and chairs a UK-wide near-peer teaching special interest group.

Peter Cantillon

Peter Cantillon, Mb, MSc, MHPE, is a Professor of Primary Care in the School of Medicine, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland and director of the Irish Network of Healthcare Educators.

Jo Horsburgh

Jo Horsburgh, MEd, EdD, is a Principal Teaching Fellow in Medical Education and Director of Postgraduate Studies for the Centre for Higher Education Research and Scholarship, Imperial College, London, UK.

Manon Kluijtmans

Manon Kluijtmans, PhD, is Professor of Education to Connect Science and Professional Practice at the University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands. She is Vice-Rector Teaching and Learning, and Director of the Center for Academic Teaching, Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

References

- Adler SR, Chang A, Loeser H, Cooke M, Wang J, Teherani A. 2015. The impact of intramural grants on educators’ careers and on medical education innovation. Acad Med. 90(6):827–831.

- Akkerman SF, Meijer PC. 2011. A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teach Educ. 27 (2):308–319.

- Andrew N, Ferguson D, Wilkie G, Corcoran T, Simpson L. 2009. Developing professional identity in nursing academics: the role of communities of practice. Nurs Educ Today. 29(6):607–611.

- Barrett JK. 2013. Medical teachers in Australian hospitals: knowledge, pedagogy and identity [dissertation]. Melbourne: University of Melbourne.

- Bartle E, Thistlethwaite J. 2014. Becoming a medical educator: motivation, socialisation and navigation. BMC Med Educ. 14(1):110.

- Beauchamp C, Thomas L. 2009. Understanding teacher identity: an overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Camb J Educ. 39(2):175–189.

- Beijaard D, Meijer PC, Verloop N. 2004. Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teach Educ. 20(2):107–128.

- Brown JS, Duguid P. 2001. Knowledge and organization: a social-practice perspective. Organ Sci. 12(2):198–213.

- Brownell SE, Tanner KD. 2012. Barriers to faculty pedagogical change: lack of training, time, incentives, and… tensions with professional identity? CBE—Life Sci Educ. 11(4):339–346.

- Budden CR, Svechnikova K, White J. 2017. Why do surgeons teach? A qualitative analysis of motivation in excellent surgical educators. Med Teach. 39(2):188–194.

- Burdick WP, Diserens D, Friedman SR, Morahan PS, Kalishman S, Eklund MA, Mennin S, Norcini JJ. 2010. Measuring the effects of an international health professions faculty development fellowship: the FAIMER institute. Med Teach. 32(5):414–421.

- Burton S, Boschmans SA, Hoelson C. 2013. Self-perceived professional identity of pharmacy educators in South Africa. Am J Pharm Educ. 77(10):210–210.

- Cantillon P, Dornan T, De Grave W. 2019. Becoming a clinical teacher: identity formation in context. Acad Med. 94(10):1610–1618.

- Cantillon P, D'Eath M, De Grave W, Dornan T. 2016. How do clinicians become teachers? A communities of practice perspective. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 21(5):991–1008.

- Carey EC, Weissman DE. 2010. Understanding and finding mentorship: a review for junior faculty. J Palliat Med. 13(11):1373–1379.

- Cox BE, McIntosh KL, Reason RD, Terenzini PT. 2011. Culture of teaching: policy, perception, and practice in higher education. Res High Educ. 52(8):808–829.

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. 2018. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 93(2):185–191.

- Dahlgren LO, Eriksson BE, Gyllenhammar H, Korkeila M, Sääf-Rothoff A, Wernerson A, Seeberger A. 2006. To be and to have a critical friend in medical teaching. Med Educ. 40(1):72–78.

- Davies R, Hanna E, Cott C. 2011. “They put you on your toes”: physical therapists’ perceived benefits from and barriers to supervising students in the clinical setting. Physiother Can. 63(2):224–233.

- De Carvalho-Filho MA, Tio RA, Steinert Y. 2019. Twelve tips for implementing a community of practice for faculty development. Med Teach. 42(2):1–7.

- De Cossart L, Fish D. 2005. Cultivating a thinking surgeon: new perspectives on clinical teaching, learning and assessment. Harley: tfm Publishing Limited.

- Deiorio NM, Carney PA, Kahl LE, Bonura EM, Juve AM. 2016. Coaching: a new model for academic and career achievement. Med Educ Online. 21(1):33480.

- DeMeester DA. 2012. The meaning of the lived experience of nursing faculty on a dedicated education unit [dissertation]. Las Vegas: University of Nevada.

- Dick ML, King DB, Mitchell GK, Kelly GD, Buckley JF, Garside SJ. 2007. Vertical integration in teaching and learning (VITAL): an approach to medical education in general practice. Med J Aust. 187(2):133–135.

- Dybowski C, Harendza S. 2014. “Teaching is like nightshifts …”: A focus group study on the teaching motivations of clinicians. Teach Learn Med. 26(4):393–400.

- Eteläpelto A, Vähäsantanen K, Hökkä P, Paloniemi S. 2014. Identity and agency in professional learning. In: Billett S, Harteis C, Gruber H, editors. International handbook of research in professional and practice-based learning. Dordrecht: Springer; p. 645–672.

- Fitzpatrick M, Moore S. 2015. Exploring both positive and negative experiences associated with engaging in teaching awards in a higher education context. Innov Educ Tech Int. 52(6):621–631.

- Franzenburg G. 2009. Educational intervision: theory and practice. Probl Educ. 13(1):37–43.

- Graham RH. 2018. The career framework for university teaching: background and overview. London: Royal Academy of Engineering.

- Gusic ME, Amiel J, Baldwin CD, Chandran L, Fincher RM, Mavis B, O’Sullivan P, Padmore J, Rose S, Simpson D. 2013. Using the AAMC toolbox for evaluating educators: you be the judge! Med Ed Portal. 9:9313.

- Hafler JP, Ownby AR, Thompson BM, Fasser CE, Grigsby K, Haidet P, Kahn MJ, Hafferty FW. 2011. Decoding the learning environment of medical education: a hidden curriculum perspective for faculty development. Acad Med. 86(4):440–444.

- Harden RM, Lilley P. 2018. The eight roles of the medical teacher: the purpose and function of a teacher in the healthcare professions. London: Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Hermans H, Hermans-Konopka A. 2010. Dialogical self theory: positioning and counter-positioning in a globalizing society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hermans HJ, Gieser T. 2012. Introductory chapter: history, main tenets and core concepts of dialogical self theory. In: Hermans HJ, Gieser T, editors. Handbook of dialogical self theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; p. 1–22.

- [HEA] Higher Education Academy. 2011. The UK professional standards framework for teaching and supporting learning in higher education. London: Higher Education Academy.

- Hoffman KG, Donaldson JF. 2004. Contextual tensions of the clinical environment and their influence on teaching and learning. Med Educ. 38(4):448–454.

- Holland D, Lachicotte W. Jr. 2007. Vygotsky, Mead, and the new sociocultural studies of identity. In: Daniels H, Cole M, Wertsch JV, editors. The Cambridge companion to Vygotsky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; p. 101–135.

- Holland DC, Lachicotte W, Jr Skinner D, Cain C. 1998. Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Hu WCY, Thistlethwaite JE, Weller J, Gallego G, Monteith J, McColl GJ. 2015. It was serendipity’: a qualitative study of academic careers in medical education. Med Educ. 49(11):1124–1136.

- Huber MT, Hutchings P. 2005. The advancement of learning: building the teaching commons. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Huggett KN, Greenberg RB, Rao D, Richards B, Chauvin SW, Fulton TB, Kalishman S, Littlefield J, Perkowski L, Robins L, et al. 2012. The design and utility of institutional teaching awards: a literature review. Med Teach. 34(11):907–919.

- Hurst KM. 2010. Experiences of new physiotherapy lecturers making the shift from clinical practice into academia. Physiotherapy. 96(3):240–247.

- Hökkä P, Vähäsantanen K, Mahlakaarto S. 2017. Teacher educators’ collective professional agency and identity: transforming marginality to strength. Teach Educ. 63:36–46.

- Jauregui J, O’Sullivan P, Kalishman S, Nishimura H, Robins L. 2019. Remooring: a qualitative focus group exploration of how educators maintain identity in a sea of competing demands. Acad Med. 94(1):122–128.

- Kalliola S, Mahlakaarto S. 2011. The methods of promoting professional agency at work. Paper presented at the 7th international conference on researching work and learning; Shanghai.

- Jippes E, Steinert Y, Pols J, Achterkamp MC, van Engelen JML, Brand PLP. 2013. How do social networks and faculty development courses affect clinical supervisors’ adoption of a medical education innovation? An exploratory study. Acad Med. 88(3):398–404.

- Kashiwagi DT, Varkey P, Cook DA. 2013. Mentoring programs for physicians in academic medicine: a systematic review. Acad Med. 88(7):1029–1037.

- Klenowski V, Askew S, Carnell E. 2006. Portfolios for learning, assessment and professional development in higher education. Assess Eval High Educ. 31(3):267–286.

- Korthagen F, Vasalos A. 2005. Levels in reflection: core reflection as a means to enhance professional growth. Teach. 11(1):47–71.

- Kumar K, Greenhill J. 2016. Factors shaping how clinical educators use their educational knowledge and skills in the clinical workplace: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 16(1):68.

- Kumar K, Roberts C, Thistlethwaite J. 2011. Entering and navigating academic medicine: academic clinician‐educators’ experiences. Med Educ. 45(5):497–503.

- Kumpulainen K, Toom A, Saalasti M. 2012. Video as a potential resource for student teachers' agency work. In: Hjorne E, Van der Aalsvoort G, De Abreu G, editors. Learning, social interaction and diversity: exploring identities in school practices. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers; p. 169–187.

- Lake J, Bell J. 2016. Medical educators: the rich symbiosis between clinical and teaching roles. Clin Teach. 13(1):43–47.

- Lave J, Wenger E. 1991. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lavina L, Lawson F. 2019. Weaving forgotten pieces of place and the personal: using collaborative auto-ethnography and aesthetic modes of reflection to explore teacher identity development. Int J Educ Arts. 20(6):1–30.

- Lieff S, Baker L, Mori B, Egan-Lee E, Chin K, Reeves S. 2012. Who am I? Key influences on the formation of academic identity within a faculty development program. Med Teach. 34(3):E208–E215.

- Lovell B. 2018. What do we know about coaching in medical education? a literature review. Med Educ. 52(4):376–390.

- Monrouxe LV. 2010. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Med Educ. 44(1):40–49.

- Moscato SR, Miller J, Logsdon K, Weinberg S, Chorpenning L. 2007. Dedicated education unit: an innovative clinical partner education model. Nurs Outlook. 55(1):31–37.

- Nevgi A, Lofstrom E. 2015. The development of academics' teacher identity: enhancing reflection and task perception through a university teacher development programme. Stud Educ Eval. 46:53–60.

- Newton K, Lewis H, Pugh M, Paladugu M, Woywodt A. 2017. Twelve tips for turning quality assurance data into undergraduate teaching awards: a quality improvement and student engagement initiative. Med Teach. 39(2):141–146.

- Ng SL, Baker LR, Leslie K. 2017. Re-positioning faculty development as knowledge mobilization for health professions education. Perspect Med Educ. 6(4):273–276.

- O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. 2011. Reframing research on faculty development. Acad Med. 86(4):421–428.

- Paslawski T, Kearney R, White J. 2013. Recruitment and retention of tutors in problem-based learning: why teachers in medical education tutor. Can Med Educ J. 4(1):e49.

- Penuel WR, Wertsch JV. 1995. Vygotsky and identity formation: a sociocultural approach. Educ Psychol. 30(2):83–92.

- Pratt MG, Rockmann KW, Kaufmann JB. 2006. Constructing professional identity: the role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. Acad Manag J. 49(2):235–262.

- Roccas S, Brewer MB. 2002. Social identity complexity. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 6(2):88–106.

- Rodgers CR, Scott KH. 2008. The development of the personal self and professional identity in learning to teach. In: Cochran-Smith M, Feiman-Nemser S, McIntyre DJ, editors. Handbook of research on teacher education: enduring questions in changing contexts. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; p. 732–755.

- Sabel E, Archer J. 2014. Medical education is the ugly duckling of the medical world” and other challenges to medical educators' identity construction: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 89(11):1474–1480.

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marušić A. 2006. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 296(9):1103–1115.

- Santhosh L, Abdoler E, Babik JM. 2020. Strategies to build a clinician‐educator career. Clin Teach. 17(2):126–130.

- Sethi A, Schofield S, McAleer S, Ajjawi R. 2018. The influence of postgraduate qualifications on educational identity formation of healthcare professionals. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 23(3):567–585.

- Sfard A, Prusak A. 2005. Telling identities: in search of an analytic tool for investigating learning as a culturally shaped activity. Educ Res. 34(4):14–22.

- Shank MJ. 2006. Teacher storytelling: a means for creating and learning within a collaborative space. Teach Educ. 22(6):711–721.

- Siddiqui ZS, Jonas-Dwyer D, Carr SE. 2007. Twelve tips for peer observation of teaching. Med Teach. 29(4):297–300.

- Silver IL, Leslie K. 2009. Faculty development for continuing interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J Cont Educ Health Prof. 29(3):172–177.

- Skelton A. 2012. Colonised by quality? Teacher identities in a research-led institution. Brit J Sociol Educ. 33(6):793–811.

- Steinert Y. 2010. Faculty development: from workshops to communities of practice. Med Teach. 32(5):425–428.

- Steinert Y, Macdonald ME. 2015. Why physicians teach: giving back by paying it forward. Med Educ. 49(8):773–782.

- Steinert Y, O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. 2019. Strengthening teachers’ professional identities through faculty development. Acad Med. 94(7):963–968.

- Stupans I, Owen S. 2010. Clinical educators in the learning and teaching space: a model for their work based learning. Int J Health Prom Educ. 48(1):28–32.

- Søreide GE. 2006. Narrative construction of teacher identity: positioning and negotiation. Teach. 12(5):527–547.

- Trautwein C. 2018. Academics’ identity development as teachers. Teach High Educ. 23(8):995–1010.

- Van den Berg JW, Verberg CPM, Scherpbier AJJA, Jaarsma ADC, Lombarts KM. 2017. Is being a medical educator a lonely business? The essence of social support. Med Educ. 51(3):302–315.

- Van Lankveld T. 2017. Strengthening medical teachers’ professional identity: understanding identity development and the role of teacher communities and teaching courses [dissertation]. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

- Van Lankveld T, Schoonenboom J, Kusurkar R, Beishuizen J, Croiset G, Volman M. 2016. Informal teacher communities enhancing the professional development of medical teachers: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 16:109.

- Van Lankveld T, Schoonenboom J, Kusurkar RA, Volman M, Beishuizen J, Croiset G. 2017a. Integrating the teaching role into one’s identity: a qualitative study of beginning undergraduate medical teachers. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 22(3):601–622.

- Van Lankveld T, Schoonenboom J, Volman M, Croiset G, Beishuizen J. 2017b. Developing a teacher identity in the university context: a systematic review of the literature. High Educ Res Dev. 36(2):325–342.

- Van Lankveld T, Schoonenboom J, Croiset G, Volman M, Beishuizen J. 2017c. The role of teaching courses and teacher communities in strengthening the identity and agency of teachers at university medical centres. Teach Teach Educ. 67:399–409.

- Van Waes S, De Maeyer S, Moolenaar NM, Van Petegem P, Van den Bossche P. 2018. Strengthening networks: a social network intervention among higher education teachers. Learn Instr. 53:34–49.

- Wald HS. 2015. Professional identity (trans) formation in medical education: reflection, relationship, resilience. Acad Med. 90(6):701–706.

- Walkington J. 2005. Becoming a teacher: encouraging development of teacher identity through reflective practice. Asia-Pac J Teach Edu. 33(1):53–64.

- Watson C. 2006. Narratives of practice and the construction of identity in teaching. Teach. 12(5):509–526.

- Watson SL, Flotman B, Fourie W, McClelland B, Kivell D, Cooper L, Whittle R. 2012. A practical guide to developing a dedicated education unit. Wellington: Ako Aotearoa; The National Centre for Tertiary Teaching Excellence.

- Wenger E. 1998. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.