Abstract

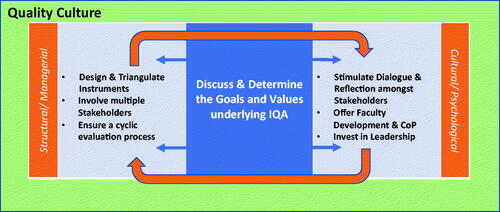

Internal quality assurance (IQA) is one of the core support systems on which schools in the health professions rely to ensure the quality of their educational processes. Through IQA they demonstrate being in control of their educational quality to accrediting bodies and continuously improve and enhance their educational programmes. Although its need is acknowledged by all stakeholders, creating a system of quality assurance has often led to establishing a ‘tick-box’ exercise overly focusing on quality control while neglecting quality improvement and enhancement. This AMEE Guide uses the concept of quality culture to describe the various dimensions that need to be addressed to move beyond the tick-box exercise. Quality culture can be defined as an organisational culture which consists of a structural/managerial aspect and a cultural/psychological aspect. As such this AMEE Guide addresses tools and processes to further an educational quality culture while also addressing ways in which individual and collective awareness of and commitment to educational quality can be fostered. By using cases within health professions education of both formal and informal learning settings, examples will be provided of how the diverse dimensions of a quality culture can be addressed in practice.

Introduction

Aims of internal quality assurance

Internal quality assurance (IQA) can be described as the set of activities and processes implemented by educational organisations to control, monitor, improve and enhance educational quality. IQA is not only essential to the day-to-day practices of educational management and organisation, but also provides evidence towards accrediting bodies that the educational practices within an organisation are up to standard (i.e. external quality assurance). This AMEE Guide specifically focuses on IQA practices.

Practice points

Fostering a quality culture requires attention to structural/managerial aspects and cultural/psychological aspects.

Different stakeholders may have a different take on ‘what the goal of internal quality assurance is’ and ‘what quality is’. Addressing these questions will help to provide guidance to quality assurance processes.

Addressing the structural/managerial aspect of a quality culture requires a cyclical process in which responsibilities are clearly defined, evaluation instruments are informed by educational theory, and all relevant stakeholders get a voice.

Addressing the cultural/psychological aspect of a quality culture requires leadership, faculty development, enabling Communities of Practice, reflection and dialogue.

Many different concepts are used when discussing the aims of IQA within educational organisations. These concepts are often used interchangeably without noting different connotations and definitions that are attached to them. When the aim of IQA is quality control, educational organisations want to check whether the outcomes of an educational programme are conform predetermined standards (Harvey Citation2004–Citation2021). Monitoring educational quality refers more to the procedures that an educational organisation has in place to ensure the quality of education provided (Harvey Citation2004–Citation2021). Quality improvement often refers to processes in place to ensure that something is ‘up to standard’ (where it previously was below a certain standard) (Williams Citation2016). Williams (Citation2016) suggests that the term quality enhancement describes the deliberate and continuous process of augmenting students’ learning experiences (QAA Citation2003). Quality control, monitoring, improvement and enhancement are all important goals of IQA. However, each concept comes with its own standards and processes. Therefore, an educational organisation needs to consider which goals of IQA it is striving towards and whether the right processes are in place to attain them.

Adverse effects of good intentions – seeking balance

‘Being in control’ of educational quality and having a sound IQA system are important areas of attention for accreditation bodies (EUA Citation2009). As a consequence, however, quality assurance runs the risk of being considered a ‘beast that requires feeding’: a list of bureaucratic boxes that needs to be ticked (Newton Citation2000). Harvey and Stensaker (Citation2008) signalled that the continuous generation of quality control data has often been disconnected from staff and students’ needs which actually inhibited educational improvement and enhancement. Ultimately, both quality control and improvement are needed, as also voiced by teachers participating in a study by Kleijnen et al. (Citation2014) who acknowledged that enhancement should be at the core of IQA without neglecting the importance of monitoring educational quality. For brevity purposes, this guide will from here on out speak of monitoring and enhancement where monitoring covers both control and monitoring goals, and enhancement covers the improvement and enhancement goals of IQA.

Building a quality culture

The European University Association (EUA) coined the concept of quality culture as ‘an organisational culture that intends to enhance quality permanently and is characterised by two distinct elements: a cultural/psychological element of shared values, beliefs, expectations and commitment concerning quality and a structural/managerial element with defined processes that enhance quality and aim at coordinating individual efforts’ (EUA Citation2006, p. 10). The notion of quality culture captures the intention to nurture shared educational values, flexibility, openness, a sense of ownership, and a collective commitment – alongside IQA systems and processes (Sursock Citation2011; Bendermacher et al. Citation2020). A quality culture is considered to help coordinate individual improvement efforts, shape mutual expectations, and stimulate a collective responsibility (EUA Citation2006). It is through a created synergy between these elements and evaluation programmes that continuous educational enhancement becomes embedded in the everyday teaching practice (Ehlers Citation2009; Blouin Citation2019).

This AMEE guide

An earlier AMEE Guide, number 29, (Goldie Citation2006) looked into the history of programme evaluation and described various sets of questions one needs to ask when designing a system of evaluation, including ethical questions. Guide number 67 (Frye and Hemmer Citation2012), built on the suggestions by Goldie and provided an overview of common evaluation models which can be used to determine whether an educational programme (ranging from the level of course to curriculum) has brought about change, i.e. focusing on the outcomes of an educational programme.

This AMEE Guide focuses on building a comprehensive approach to IQA of education by using the concept of quality culture (EUA Citation2006; Ehlers Citation2009; Blouin Citation2019). We describe practices (see ) that educational organisations can use to optimise the processes and systems informing IQA while simultaneously fostering the awareness of and commitment to continuous enhancement of educational quality (Bendermacher et al. Citation2017). Throughout the following paragraphs, we will use cases from the field of health professions education, to illustrate how quality culture development in health professions education can be nurtured. It is important to note that the practices we describe are not hierarchical in nature and that there is no real linearity to the process of employing them. Defining and creating an organisational quality culture requires simultaneous attention to all aspects.

Figure 2. Competing values model (Kleijnen Citation2012 – based on Quinn and Rohrbaugh Citation1983).

Our perspective – reflexivity

This guide is written from the perspective of an expert group on IQA at Maastricht University, Faculty of Health Medicine and Life Sciences (FHML) entitled ‘task force programme evaluation’. The task force is, in collaboration with relevant stakeholders, responsible for monitoring and enhancing educational quality of all educational programmes within FHML. This responsibility is executed by (1) ensuring valid and reliable data collection through standardized instruments, (2) executing in-depth studies on educational quality through a mix of quantitative and qualitative research methodologies, (3) providing faculty development on educational quality assurance to relevant stakeholders, and (4) stimulating a dialogue towards continuous quality enhancement of the programmes within FHML. The authors of this AMEE Guide are all researchers within the School of Health Professions Education and have backgrounds in educational sciences (RS, IW, DD), educational psychology (JW), health sciences (CS), and policy and management (GB). In addition, one of the authors (GB) is a policy advisor who specializes specifically in the concept of quality culture and, through his research, has further explored the concept of quality culture. We are aware that not all health professions education schools employ similar task forces and that sometimes the task of programme evaluation may rest on the shoulders of a single individual. Nevertheless, we hope that our experiences, research and insights provide the necessary guidance and support to anyone involved in educational quality assurance.

Fostering a quality culture – what are we striving for?

Discuss and determine underlying goals and values

What is quality?

When considering what goals IQA has, an important question to address is ‘what do we mean when we say quality?’; what is often forgotten is that quality lies in the eye of the beholder. This may result in multiple stakeholders within a single organisation having different conceptions when it come to the question ‘what is quality?’. In their seminal work Defining Quality, Harvey and Green (Citation1993) discerned five different conceptions of quality: excellence, perfection/consistency, fit-for-purpose, value for money, and transformation. Seeing quality as striving for ‘fit-for-purpose’ requires, for example, ensuring that educational goals are attained and that graduates pass a certain standard. Through the lens of quality as transformation, however, IQA would be striving to determine to what extent ‘value has been added’ to the student and that students have been empowered. Although it is outside of the scope of this AMEE Guide to go into depth on each definition, we encourage readers to familiarise themselves with these conceptions of quality. Familiarity with these conceptions will provide a vocabulary through which stakeholders within an educational organisation can discuss which definition(s) they value and foreground. We believe that educational organisations will always be aiming to attain different types of quality simultaneously. Imagine ensuring that the finances of a programme are in order versus ensuring the ranking of an educational organisation. Therefore, we strongly advise readers to discuss with relevant stakeholders in their own organisation what quality means to them. Because, just like defining the aims of IQA within your organisation, the conception(s) of quality that are held will provide direction and guidance on how to design instruments and procedures for IQA, which stakeholders to involve and how to shape a quality culture. Misalignment in perceptions about goals of IQA and conceptions of quality may thwart the process of building a fruitful quality culture as the processes that inform quality as fit-for-purpose are different to those informing quality as transformation.

Which quality culture?

It is important to realise that a quality culture is not something that institutions have to develop from scratch and also that there is no such thing as ‘the ideal’ quality culture. That is, each institution already possesses a certain kind of quality culture which determines how that institution reacts to external developments, and attempts to foster internal collaborations (Bendermacher Citation2021). Moreover, a quality culture is influenced by the organisation’s context and its developmental phase in dealing with quality management (Harvey and Stensaker Citation2008). For instance, educational organisations who are in the early stages of setting-up their IQA system would probably benefit most from first focusing on monitoring and controlling educational quality (i.e. to install or fine-tune procedures and standards). Those organisations who already have established a robust system which monitors whether minimum criteria are met, can shift their focus towards continuous enhancement while addressing changes in the organisation’s environment. Reflection exercises like discussing the Organisational Culture Assessment Index (see Box 1) can aid stakeholders to disclose their core values. This discussion can help shape strategies and solutions that lead to a better alignment between these values and organisational procedures (Berings and Grieten Citation2012). Such reflections and dialogues can also help to alter the emphasis from ‘whether things are being done well’, to ‘whether the right things are being done’ (Cartwright Citation2007).

Building a quality culture – structural & managerial components

No system of IQA can exist without a regular influx of data that helps to address the goals of IQA and provides input for stakeholders to monitor and enhance the programme’s quality. To ensure that this system contributes to strengthening the quality culture, the following aspects need to be considered: the design and triangulation of instruments, involvement of stakeholders, and the cyclical nature of IQA.

Design & triangulation of instruments

Incorporating educational principles in design

IQA should be geared towards the key components that make up a curriculum, such as educational activities or courses, and should build evaluation instruments firmly grounded in theories and the literature on learning and teaching (Frick et al. Citation2010). In other words, the items of an evaluation instrument must be derived from what the literature has shown determines the quality of an educational programme. If the design of IQA instruments is based on these educational principles, this will augment the chances of outcomes of data collection being actionable by the different stakeholders (Bowden and Marton Citation1999; Dolmans et al. Citation2011). Educational principles can be defined as a way of thinking about how and why an educational program is effective (). Depending on the nature of the curriculum or the programme you want to evaluate, multiple educational principles might apply. In Box 2, we provide two examples (1) principles of constructivist learning to evaluate problem-based learning, and (2) cognitive apprenticeship to evaluate clinical teaching.

In addition to the fact that educational principles are important to keep in mind when designing an instrument, it is essential to also consider the fact that education is highly context-specific, i.e. what might work, based on theoretical principles, might differ dependent on the particular aims and target groups as well as contextual differences (Hodges et al. Citation2009; Kikukawa et al. Citation2017). As a consequence, the design of instruments, which is preferably based on theoretical guidelines, remains a matter of customisation. It is important to continuously adapt and align your instruments, depending on what your aims are and the context in which the instruments are being used.

Triangulation of instruments

Depending on the aims of IQA, the aspects of the programme you are trying to evaluate and the stakeholders whose input you need, requirements for instrument design change. When the primary aim is to control and monitor quality for accountability purposes, collecting valid and reliable data for a standardised set of factors from the majority of the population takes precedent (Dolmans et al. Citation2011). This goal warrants a quantitative approach to data collection. When the focus is on the improving and enhancing of educational quality, the information that is needed should be rich, descriptive and more qualitative in nature so that clear and specific input can be found on how to improve and enhance education. Since educational quality is multidimensional and learning environments are complex, it is recommended to combine both quantitative and qualitative methods to measure it (Cashin Citation1999). Questionnaires, interviews, classroom observations, document analysis and focus groups are all commonly used (Braskamp and Ory Citation1994; Seldin Citation1999). For instance, one could first evaluate a course by administering a large-scale quantitative student questionnaire to bring into focus the course’s overall strengths and weaknesses. Subsequent qualitative focus groups can then elaborate on these data and place them in a clearer perspective. Building a quality culture requires triangulation of different instruments and procedures to provide a holistic overview of the quality of an educational programme and to collect data that may inform either monitoring or enhancement purposes.

Involving all relevant stakeholders

Identifying stakeholders

When designing a system of continuous quality enhancement various stakeholders need to be involved. Since ‘quality is in the eye of the beholder’ and we need to consider the context in which evaluations take place, each stakeholder should be invited to add their perspective on educational quality to render a holistic programme of evaluation (Harvey and Stensaker Citation2008). To identify stakeholders one may consider questions like ‘Who are the recipients of this education?’ ‘Who are involved in teaching and managing this education?’ ‘Who can judge the effectiveness of this education?’. Once relevant stakeholders are identified, the question arises of how and through which instruments they can be involved, what aspects and level of education they can best evaluate, followed by the question of best timing of involving them and approaching them. Depending on context and timing, each stakeholder might have their own situated knowledge and lived experience as well as contribution to offer in the process of enhancing educational quality (Kikukawa et al. Citation2021). All these questions need to be considered within the light of the local context in which stakeholders will be involved as appropriate involvement may take different shapes depending on institutional, accreditation or even cultural standards.

Involving key stakeholders

Students have traditionally been subjected to course evaluations, for, as the consumers of education, they are considered to have a crucial stake in the QA process (Coates Citation2005; Marsh Citation2007). As ‘experienced experts’, they can provide detailed, information on distinct educational entities such as a course, workshop or teachers’ performance. This data can be collected both quantitatively through validated questionnaires and qualitatively through interviews and focus groups. Although different data might be generated (numeric and narrative, generic and specific), as a whole, involving students’ perspectives can provide insight into the way the curriculum is put into practice compared to how it has been designed, including perceived strong points and points for improvement. To strengthen a quality culture students can also be involved in education and institutional decision-making. They can, for instance, serve on a student evaluation committee (SEC) (Stalmeijer et al. Citation2016) or, as student representatives, join faculty and programme coordinators on management bodies (Elassy Citation2013; Healey et al. Citation2016). These students often already have gained content expertise, developed a shared language with faculty, and learned how to overcome potential power relations. There is a strong movement towards more deliberate involvement of students in the design, implementation and decision making regarding educational practices (e.g. Bovill et al. Citation2016). This is reflected in different, approaches to student participation like design-based research, participatory design, co-creation, co-design, student voice, student–staff partnership, students as change agents, student engagement, and student empowerment (Seale Citation2009; Anderson and Shattuck Citation2012; Bovill et al. Citation2016). By intensifying the active engagement of students in the educational (design) processes, the aim is to simultaneously improve teaching and learning of both faculty and students (Bovill et al. Citation2016). It is important to stress that this approach goes beyond just listening to student voices; the focus is on empowering students to actively collaborate with teachers and educational management (Bovill et al. Citation2011). Through this approach students and staff can form partnerships, co-create, and (re-)design education (Martens et al. Citation2019; Citation2020).

Not only students’ input can be insightful, inviting faculty into the evaluation process can give great insight into practical teaching and organizational aspects and simultaneously increase buy-in and commitment. While faculty is mostly the user of evaluation data to improve courses and training programmes, they can also become evaluation respondents and thereby contribute to IQA. Teaching staff could also be included structurally during or at the end of an educational activity to evaluate observed pitfalls or organizational challenges. As an example, consider involving PBL tutors in the evaluation of PBL cases, lectures and workshop providers on the alignment of their educational activities, or mentors in fulfilling their roles in programmatic assessment (see Box 3). On a meta-level, faculty can also be engaged in the evaluation of programme-evaluation procedures. Considering the absence of formal evaluation data for course coordinators’ performance, course coordinators could actively invite faculty to engage in feedback dialogues and reflection or debriefing sessions. Moreover, by empowering teaching staff to co-design (part of the) IQA approaches, their involvement in these practices and their required follow-up might be further increased (Bendermacher Citation2021).

The future employers of students are also important stakeholders in IQA: how do representatives from the work field feel about the graduates? Are students joining the work field well-prepared and equipped with the required skills, knowledge and attitudes? Does the curriculum reflect the needs of the workforce? Employers could be consulted ad-hoc in dialogue or through questionnaires when designing a new curriculum or on a more regular basis to discuss students’ performance during internships or curriculum or alumni evaluations.

Alumni can provide valuable information through evaluation questionnaires about areas they missed in the programme and the extent to which the competences taught and trained have helped them in their career(choice). This can be particularly insightful when facing a curriculum redesign, indicating that involvement of alumni is not required on a structural level.

In a similar vein, clients or patients can shed light on students’ preparedness to enter the field or on educational quality improvement from their perspective (Romme et al. Citation2020). This can either be in the context of designing education but also through inviting their feedback on student’s performance in a simulated setting or during clinical rotations. This, however, requires the development and use of validated questionnaires, awareness of power dynamics and respect for individual patient preferences concerning the provision of performance evaluation (Sehlbach et al. Citation2020).

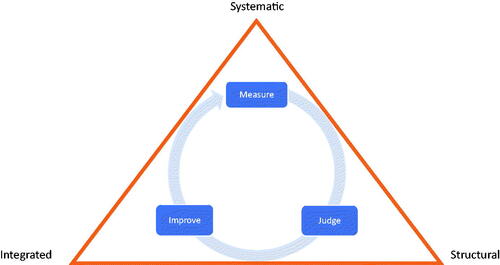

A cyclical approach to IQA – systematic, structural and integrated

To ensure that data generated by IQA practices results in continuous improvement of educational quality, IQA requires a cyclic process characterised by practices that are (1) systematic, (2) structural and (3) integrated (Dolmans et al. Citation2003) ().

Systematic implies that all important educational design elements of a curriculum are addressed and covered by a variety of evaluation instruments and procedures (Dolmans et al. Citation2003). Systematic also applies to the involvement of stakeholders. For example, evaluating a PBL curriculum requires information about various aspects of each course: lectures, practicals, tutorial group meetings, the quality of PBL tutors, the quality of the assessment and performance of students. This information should be provided by the stakeholders involved in the course: students, lecturers, teachers, PBL tutors, course coordinators.

Structural points to the importance of periodic evaluation at regular intervals (Dolmans et al. Citation2003). Frequency of these intervals should be determined based on the importance of the aspect being evaluated (). For instance, if after two academic years the course quality has stabilised, one may decide to evaluate parts of the programme in depth only once in 2 years to avoid evaluation fatigue (Svinicki and Marilla Citation2001). It is important that these practices are clear and agreed upon. Policy documents should communicate the different activities (e.g. questionnaire, focus groups etc.), purposes (e.g. monitor versus enhance), frequency of activities (e.g. regular intervals, avoid ad-hoc evaluations), levels of curriculum (e.g. course level versus curriculum level) and relevant stakeholders (e.g. responsibilities) involved in IQA.

Figure 3. Cyclic process of IQA – Inspired by Dolmans et al. Citation2003.

Finally, IQA practices should be integrated, meaning that relevant stakeholders are aware of and give shape to their responsibilities within monitoring and enhancing educational quality (Dolmans et al. Citation2003). Educational organisations should enable active involvement of stakeholders by giving them a voice in the IQA process. Furthermore, organisations need to ensure that improvement plans are developed, implemented and evaluated, and that this process is discussed regularly and transparently. Overall, when IQA activities are integrated in the organisation's regular work patterns, this will contribute to a continuous cyclical process and continuous enhancement of educational quality.

Building a quality culture – cultural & psychological components

If we want to ensure that the data collected for IQA purposes will indeed feed into a quality culture in which all stakeholders are aware of and feel commitment towards continuously enhancing educational quality, several components require attention: the extent to which reflection and dialogue are stimulated, supporting stakeholders through faculty development and enabling communities of practice, and leadership that fosters a quality culture.

Stimulating reflection and dialogue regarding educational quality

Stimulating reflection

Having data on educational quality does not automatically lead to enhancement of education quality (Richardson and Placier Citation2001; Hashweh Citation2003). Although grounding the design of your evaluation in theoretical principles will generate rich data that is theoretically grounded, context-specific and more actionable (Bowden and Marton Citation1999) research also demonstrates that the recipients of that data, may need help translating the data to activities that will enhance educational quality (Stalmeijer et al. Citation2010; Boerboom et al. Citation2015; van Lierop et al. Citation2018). There may be a long road between paper and action. Translating data to action may be stimulated in different ways. Action may be spurred by providing contrasting evaluation data. For example, when reporting evaluation results of a course, one can consider to report relative evaluation data (e.g. comparison with other courses, with the course results of the previous year) next to the evaluation results of a course (see Box 4). Similarly, but in the case of providing feedback to individual teachers, asking teachers to fill out a self-assessment and presenting these results next to actual student evaluations of the teacher in question could provide the teacher in question with added insights of areas to improve in. Clinical teachers being interviewed about the effect of this self-assessment indicated that especially negative discrepancies between their self-assessment and the evaluations of students were experienced as a strong impetus for change (Stalmeijer et al. Citation2010). However, in the same study, clinical teachers indicated needing help to translate certain aspects of the feedback to action. For example, they had a hard time helping students to formulate learning goals and requested additional coaching. Furthermore, there is evidence that evaluation data may cause emotional reactions like denial or defensiveness (DeNisi and Kluger Citation2000; Sargeant et al. Citation2008; Overeem et al. Citation2009) making discussion of the data essential. van Lierop et al. (Citation2018) experimented with coaching for clinical teachers by introducing peer group reflection meetings in which clinical teachers would discuss their self-assessments and student evaluations. The study found that the peer group reflection meetings assisted clinical teachers in formulating plans for improvement.

Dialogue

To ensure continuous enhancement of educational quality, it is important that the data which is being collected informs improvement initiatives and is discussed by all layers and structures of the educational organisation. The organisational dialogue should similarly be structurally embedded within the organisational process as quality assurance. Otherwise it may run the risk of becoming a jungle of information without appropriate steps being taken to act on the evaluation results. To do so, evaluation should be a recurring topic on the agenda of different levels in the curriculum (e.g. course, clerkship, year, bachelor). This open dialogue about the evaluation activities should be informed by action plans formulated by coordinators on the different levels of the educational organisation. Implementation and evaluation of these action plans should be discussed regularly. Results must be discussed openly so that they can be used effectively to improve education continuously (Dolmans et al. Citation2011; Bendermacher et al. Citation2020). That is, avoiding judgemental, assessing way of discussing results and performances, instead focus on constructive language supporting improvement. In this way, dialogue will enhance the use of evaluative data for improvement purposes (Kleijnen et al. Citation2014). Creating opportunities for this dialogue should take on a structural character, meaning that these discussions are organised with a set frequency and involving all relevant stakeholders. For example, course coordinators can discuss evaluation reports with teachers and student representatives during reflection sessions (van der Leeuw et al. Citation2013), formulate specific plans for action and attach a timeline to implementation and evaluation of these plans on a structural basis. On a larger scale, students can be made active owners of educational quality by presenting evaluation results and plans for improvement during (online) lectures (Griffin and Cook Citation2009). Making them a part of the discussion will provide students with an extra incentive to participate in evaluation procedures if they see the results of their participation and are afforded the opportunity to be heard by faculty and exchange views (Griffin and Cook Citation2009; Healey et al. Citation2015).

Supporting stakeholders through faculty development and communities of practice

Faculty development on quality assurance

Providing faculty development for stakeholders actively involved within the process of quality assurance, is another strategy that may be employed to ensure that data on educational quality can be effectively translated to enhancement of educational quality. Depending on the role that a certain (group of) stakeholder(s) has within the process of quality assurance, different aspects can be addressed during faculty development workshops. For example, at FHML we provide yearly workshops for members of the student evaluation committees (SEC) (Stalmeijer et al. Citation2016) and the educational programme committees (EPC). The SEC, usually comprise 10–12 students, and their goal is to generate qualitative data on educational activities and to discuss outcomes with teaching teams. In a yearly workshop, members of the SEC are provided with guidelines on how to effectively fulfil their role (Box 5).

Another yearly workshop is provided to members of the EPC. In the Netherlands, each university programme is mandated by law to have an EPC. An EPC consists of a mix of staff and student representatives and is tasked with overall monitoring of educational quality at the programme level. The EPC can give advice, either on request or on their own initiative, on education matters like examination regulation and its implementation, education budget, educational innovation, and the system of IQA. During the yearly workshop (see Box 5) EPC members are trained jointly and involved in an active discussion about their role in the process of educational quality assurance.

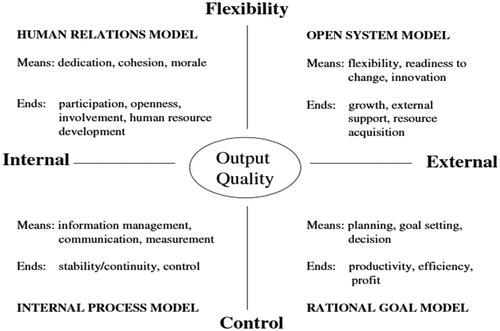

Box 1 The organisational culture assessment index

A well-known questionnaire to conceptualise organisational values is the Organisational Culture Assessment Index (OCAI). The OCAI is based on a competing values framework which includes two dimensions. The first dimension encompasses an internal versus an external orientation. The second dimension concerns a control or flexibility orientation. Organisations can strive to invest in different orientations at the same time: to be structured and stable (internal/control orientation), to be a collaborative community, (internal/flexible orientation), to be proactive and innovative (external/flexible orientation), and to be goal-oriented and efficient (external/control orientation). The different combinations of value orientations result in four organisational culture models which reflect the means and ends an organisation can target at (internal process- human relations-, open system-, and rational goal model). The OCAI sketches both the current and preferred value orientation of organisational members and therewith can be used to identify the direction in which the organisation needs to develop (Cameron and Quinn Citation1999).

Box 2 Educational principles translated to IQA instrument-design

Evaluating Problem Based Learning (PBL) – Constructivist Learning Principles

At FHML, we apply a PBL approach, which fits well with four educational principles: contextual, constructive, collaborative, and self-directed learning (Dolmans Citation2019). These principles are aligned with the vision of our institute in which it is stated that our educational programs are perceived to have high quality if they are well aligned with these four educational principles. These principles have been defined in the educational literature, empirically tested and are known to be effective in educational practice. Therefore, we have used the educational principles underlying PBL as the backbone for a standardized questionnaire used to evaluate all Bachelor courses at FHML. This questionnaire is administered after each course and filled out by students that followed the course. Results are reported back to all stakeholders involved.

Example items (Likert scale 1 = fully disagree; 5 = fully agree) are:

Contextual: The course encouraged me to apply what I learned to other cases

Constructive: The educational activities encouraged me to actively engage with the course content

Collaborative: The educational activities stimulated collaboration with fellow students

Self-directed: I was encouraged to study various resources during the course

Providing feedback to clinical teachers – Cognitive Apprenticeship

Another example is an approach we took to evaluating clinical teaching during clinical rotations by building on the teaching methods as described in Cognitive Apprenticeship (Collins et al. Citation1989). In order to provide feedback to individual physicians tasked with clinical teaching, we constructed items out of the teaching methods (modelling, coaching, scaffolding, articulation, reflection, exploration) which could be filled out by medical students (Stalmeijer et al. Citation2008; Citation2010b). The feedback produced by this instrument was thought to be highly relevant and actionable by clinical teachers (Stalmeijer et al. Citation2010a; Citation2010b).

Example items (Likert scale 1 = fully disagree; 5 = fully agree) are, The clinical teacher…:

Modelling: …created sufficient opportunities for me to observe them

Coaching: …gave useful feedback during or immediately after direct observation of my patient encounters

Articulation: …asked me questions aimed at increasing my understanding

Exploration: …encouraged me to formulate learning goals

For the full instrument see: Stalmeijer et al. (Citation2010a).

Box 3 Evaluating the experience of being a mentor in programmatic assessment

Multiple-Role Mentoring (Meeuwissen et al. Citation2019)

The Master in Medicine at FHML is designed according to principles of competency-based education and programmatic assessment. Students’ learning is supported by physician-mentors who have the role to both coach the student but also provide advice on their assessment. Using semi-structured interviews, the experience of the mentors with ‘multiple-role mentoring’ was explored. Based on the results it was concluded that mentors chose different approaches to fulfilling their mentor role and sometimes struggled. The results gave rise to revision of the faculty development directed towards mentors.

Box 4 Stimulating reflection through IQA – two examples

Providing relative evaluation data on quality of clerkships

Students doing their clerkships through FHML are asked to evaluate each clerkship using a questionnaire informed by theories on workplace learning (Strand et al. Citation2013). As part of the report, clerkship coordinators and affiliated hospitals are presented with two sets of relative evaluation data: comparison between clerkships provided within the same hospital and comparison between the same clerkship provided by different affiliated hospitals.

Experience tells us that especially this contrasting data helps clerkship coordinators get a sense of how they perform and where to improve.

Comparison clerkships within one hospital

Hospital X in Y

Comparison clerkship between hospitals.

Internal Medicine Rotations Affiliated Hospitals FHML

Box 5 Faculty development examples

Workshop Topics for Student Evaluation Committee (SEC) members (Stalmeijer et al. Citation2016)

Next to highlighting the importance of the quality assurance cycle, the role of student therein is explained, students learn how to evaluate specific educational activities of the curriculum, their alignment, practical organization and their learning affect according to the PBL criteria. Students are then offered ample opportunity in form of role play to practice how to provide effective feedback to course coordinators and members of the planning group.

Workshop Topics Educational Programme Committee (EPC) members

The following topics are incorporated in the training

Defining educational quality

Defining educational quality assurance, its facets and determinants

Monitoring vs enhancing educational quality

Moving from quality assurance to quality enhancement

Analysing a case related to EQA aimed at understanding what is required for a balanced quality assurance system

Using the concept of Quality Culture to see how FHML can improve its EQA approaches

Communities of practice

A Community of Practice (CoP) can be defined as a ‘persistent, sustaining, social network of individuals who share and develop an overlapping knowledge base, set of beliefs, values, history, and experiences focused on a common practice and/or mutual enterprise’ (Barab et al. Citation2002, p. 495). The establishing of communities of practice (CoPs), can further educational enhancement as they foster an exchange of expertise and ideas for innovation (de Carvalho-Filho et al. Citation2020). CoPs facilitate staff in gaining new perspectives and opportunities to improve, e.g. by means of sharing good practice. CoPs are specifically relevant for the nurturing of the psychological dimension of a quality culture; they form an environment in which the valuing of teaching and learning, reflection on daily work experiences and challenges, and teacher identity building is central (Cantillon et al. Citation2016). Constructive peer feedback processes in CoPs, and the offering of mutual professional and social support help to balance the relation between developing a sense of ownership and feeling accountable for educational enhancement (Bendermacher et al. Citation2020). An open and longitudinal character of CoPs is essential to their success; they should go beyond the mere establishment of a temporal group of those already highly involved and committed to education. At FHML we organise several activities aimed at stimulating CoPs like journal clubs, monthly meetings in which educational innovations are presented and discussed, and a longitudinal leadership training for course coordinators in which participants are explicitly invited to share experiences with their colleagues. We recommend the twelve tips by Carvalho-Filho and colleagues (2020) for inspiration on how to implement a CoP for faculty development purposes.

Leadership that fosters a quality culture

To value the voice of students and staff members, educational leaders can make a difference by facilitating debate about the quality of education (Sursock Citation2011), but also by listening and being responsive to others within the organisation (Knight and Trowler Citation2000). A review conducted by Bland et al, indicated that, in addition to creating an open communication climate, favourable leadership behaviours for successful curriculum development concern assertive, participative and cultural/value-influencing behaviours (Bland et al. Citation2000). That is, successful leaders promote collaboration, share values in the light of the envisioned change, and build trust and facilitate involvement (Bland et al. Citation2000).

Bendermacher et al. (Citation2021) highlighted that in their efforts to nurture a quality culture, leaders acting at different levels within the organisation face various challenges. On the higher management level, leaders typically deal with ‘political’, ‘strategic’ and ‘structural’ issues which concern rules, policies, responsibilities and accountability, needed for a quality culture to take root. Educational leadership entails a balancing of present structures and systems with staff values and requires coalition building, negotiation and mediating for resources (Bolman and Deal Citation2003). To this end, educational leaders should work to build strong relationships and networks within the institution and stimulate collaboration and interaction (O’Sullivan and Irby Citation2011). Leaders working on the organisational meso, or micro level appear to be more engaged in the direct improvement of the educational content and focus more on facilitating team learning. Complex organisational structures and emerging trends of interdisciplinary collaboration in health professions education, cause the influence of leaders to be exerted more and more in indirect ways (Meeuwissen et al. Citation2020; Bendermacher et al. Citation2021). The influence of leaders on educational quality enhancement is increasingly being manifested through shared, collaborative and distributed approaches (e.g. McKimm and Lieff Citation2013; Sundberg et al. Citation2017; Sandhu Citation2019). Hence, instead of attributing responsibility for educational quality enhancement to ‘strong’ leaders, leaders are expected to be motivators, mentors, and facilitators and leadership in health professions education is changing from individual staff supervision, guidance, and support to a focus on the broader collective.

In the knowledge-intensive setting of health professions education institutes, educational leaders and other teaching staff members co-construct meaning and solutions to organisational issues (Tourish Citation2019). As leadership in health professions education is multi-layered, within the reality of (medical) school hierarchies, one might be a leader and a follower at the same time (McKimm and O’Sullivan Citation2016). Moreover, instead of being mere leadership recipients, academics can steer the leadership of others and impact organisational developments through co-creation (Uhl-Bien et al. Citation2014).

Interventions that can aid educational leaders to make the most out of quality culture development and IQA include: training leaders to stimulate reflection, expertise, and knowledge sharing, learning leaders to foster safety and trust relations in teacher teams, and strengthen leader’s situational sensitivity (Hill and Stephens Citation2005; Edmondson et al. Citation2007; Nordquist and Grigsby Citation2011). In order to continuously enhance, health professions education is best served with leaders who are able to combine multiple styles and who are able to coalesce different stakeholder goals and ambitions (Lieff and Albert Citation2010).

Conclusion

Using the concept of ‘Quality Culture’ this AMEE Guide has described various practices that can aid educational organisations in moving beyond the ‘tick-box’ exercises that IQA practices often evoke. We are not claiming that this is an easy task. Continuous enhancement of educational quality is a veritable team effort requiring the contribution of many. By addressing practices needed to create the systematic/managerial and cultural/psychological aspects of a quality culture (see ), we hope this AMEE Guide provides inspiration and direction for all those with a stake in educational quality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Renée E. Stalmeijer

Renée E. Stalmeijer, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the School of Health Professions Education, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Jill R. D. Whittingham

Jill R. D. Whittingham, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the School of Health Professions Education, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Guy W. G. Bendermacher

Guy W. G. Bendermacher, PhD, is a Policy Advisor at the Institute for Education, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Ineke H. A. P. Wolfhagen

Ineke H. A. P. Wolfhagen, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the School of Health Professions Education, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Diana H. J. M. Dolmans

Diana H. J. M. Dolmans, PhD, is a Professor at the School of Health Professions Education, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

Carolin Sehlbach

Carolin Sehlbach, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the School of Health Professions Education, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

References

- Anderson T, Shattuck J. 2012. Design-based research: a decade of progress in education research? Educational Researcher. 41(1):16–25.

- Barab SA, Barnett M, Squire K. 2002. Developing an empirical account of a community of practice: Characterizing the essential tensions. Journal of the Learning Sciences. 11(4):489–542.

- Bendermacher GWG. 2021. Navigating from Quality Management to Quality Culture [dissertation]. Maastricht: Ipskamp Printing.

- Bendermacher GWG, De Grave WS, Wolfhagen IHAP, Dolmans DHJM, Oude Egbrink MGA. 2020. Shaping a culture for continuous quality improvement in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 95(12):1913–1920.

- Bendermacher GWG, Dolmans DHJM, de Grave WS, Wolfhagen IHAP, Oude Egbrink MGA. 2021. Advancing quality culture in health professions education: experiences and perspectives of educational leaders. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 26(2):467–487.

- Bendermacher GWG, Oude Egbrink MGA, Wolfhagen IHAP, Dolmans DHJM. 2017. Unravelling quality culture in higher education: a realist review. High Educ. 73(1):39–60.

- Berings D, Grieten S. 2012. Dialectical reasoning around quality culture. 7th European Quality Assurance Forum (EQAF) of the European University Association (EUA), Tallinn.

- Bland CJ, Starnaman S, Wersal L, Moorehead-Rosenberg L, Zonia S, Henry R. 2000. Curricular change in medical schools: how to succeed. Acad Med. 75(6):575–594.

- Blouin D. 2019. Quality improvement in medical schools: vision meets culture. Med Educ. 53(11):1100–1110.

- Boerboom TBB, Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DHJM, Jaarsma DADC. 2015. How feedback can foster professional growth of teachers in the clinical workplace: a review of the literature. Stud Educ Eval. 46:47–52.

- Bolman LG, Deal TE. 2003. Reframing organizations. Artistry, choice, and Leadership. 3rd ed. San Fransisco (CA): Jossey-Bass.

- Bovill C, Cook‐Sather A, Felten P. 2011. Students as co‐creators of teaching approaches, course design, and curricula: implications for academic developers. Int J Acad Devel. 16(2):133–145.

- Bovill C, Cook-Sather A, Felten P, Millard L, Moore-Cherry N. 2016. Addressing potential challenges in co-creating learning and teaching: overcoming resistance, navigating institutional norms and ensuring inclusivity in student–staff partnerships. High Educ. 71(2):195–208.

- Bowden J, Marton F. 1999. The university of learning. Educa + Train. 41(5):ii–ii.

- Braskamp LA, Ory JC. 1994. Assessing faculty work. Enhancing individual and institutional performance. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass.

- Cameron KS, Quinn RE. 1999. Diagnosing and changing organizational culture based on the competing values framework. Reading (MA): Addison-Wesley.

- Cantillon P, D'Eath M, De Grave W, Dornan T. 2016. How do clinicians become teachers? A communities of practice perspective. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 21(5):991–1008.

- Cartwright MJ. 2007. The rhetoric and reality of “quality” in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education. 15(3):287–301.

- Cashin WE. 1999. Learner ratings of teaching: uses and misuses. In: Seldin P, editor. Changing practices in evaluating teaching Anker: Bolton (MA): Anker Publishing Co., Inc; p. 25–44.

- Coates H. 2005. The value of student engagement for higher education quality assurance. Qual Higher Educ. 11(1):25–36.

- Collins A, Brown JS, Newman SE. 1989. Cognitive apprenticeship: teaching the crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. In: Knowing, learning, and instruction: essays in honor of Robert Glaser. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; p. 453–494.

- de Carvalho-Filho MA, Tio RA, Steinert Y. 2020. Twelve tips for implementing a community of practice for faculty development. Med Teach. 42(2):143–149.

- DeNisi AS, Kluger AN. 2000. Feedback effectiveness: can 360-degree appraisals be improved? AMP. 14(1):129–139.

- Dolmans DHJM. 2019. How theory and design-based research can mature PBL practice and research. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 24(5):879–891.

- Dolmans DHJM, Stalmeijer RE, Van Berkel HJM, Wolfhagen IHAP. 2011. Quality assurance of teaching and learning: enhancing the quality culture. In: Dornan T, Mann K, Scherpbier A, Spencer J, editors. Medical education theory and practice. Edinburgh: Elsevier; p. 257–264.

- Dolmans DHJM, Wolfhagen HAP, Scherpbier AJJA. 2003. From quality assurance to total quality management: how can quality assurance result in continuous improvement in health professions education? Educ Health (Abingdon). 16(2):210–217.

- Edmondson AC, Dillon JR, Roloff KS. 2007. Three perspectives on team learning: outcome improvement, task mastery, and group process. ANNALS. 1(1):269–314.

- Ehlers UD. 2009. Understanding quality culture. Qual Assur Educ. 17(4):343–363.

- Elassy N. 2013. A model of student involvement in the quality assurance system at institutional level. Qual Assur Educ. 21(2):162–198.

- EUA 2006. Quality culture in European universities: a bottom-up approach. Brussels: European University Association.

- EUA 2009. ENQA report on standards and guidelines for quality assurance in the European higher education area. Brussels: ENQA.

- Frick TW, Chadha R, Watson C, Zlatkovska E. 2010. Improving course evaluations to improve instruction and complex learning in higher education. Educ Tech Res Dev. 58(2):115–136.

- Frye AW, Hemmer PA. 2012. Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE guide no. 67. Med Teach. 34(5):e288–e299.

- Goldie J. 2006. AMEE Education Guide no. 29: evaluating educational programmes. Med Teach. 28(3):210–224.

- Griffin A, Cook V. 2009. Acting on evaluation: Twelve tips from a national conference on student evaluations. Med Teach. 31(2):101–104.

- Harvey L. 2004–2021. Analytic quality glossary. http://www.qualityresearchinternational.com/glossary/

- Harvey L, Green D. 1993. Defining quality. Assess Eval Higher Educ. 18(1):9–34.

- Harvey L, Stensaker B. 2008. Quality Culture: understandings, boundaries and linkages. Eur J Educ. 43(4):427–442.

- Hashweh MZ. 2003. Teacher accommodative change. Teach Teach Educ. 19(4):421–434.

- Healey M, Bovill C, Jenkins A. 2015. Students as partners in learning. In: Enhancing learning and teaching in higher education: engaging with the dimensions of practice. Maidenhead: Open University Press; p. 141–172.

- Healey M, Flint A, Harrington K. 2016. Students as partners: reflections on a conceptual model. Teach Learn Inq. 4(2):8–20.

- Hill F, Stephens C. 2005. Building leadership capacity in medical education: developing the potential of course coordinators. Med Teach. 27(2):145–149.

- Hodges BD, Maniate JM, Martimianakis MA, Alsuwaidan M, Segouin C. 2009. Cracks and crevices: globalization discourse and medical education. Med Teach. 31(10):910–917.

- Kikukawa M, Stalmeijer R, Matsuguchi T, Oike M, Sei E, Schuwirth LWT, Scherpbier AJJA. 2021. How culture affects validity: understanding Japanese residents' sense-making of evaluating clinical teachers. BMJ Open. 11(8):e047602.

- Kikukawa M, Stalmeijer RE, Okubo T, Taketomi K, Emura S, Miyata Y, Yoshida M, Schuwirth LWT, Scherpbier AJJA. 2017. Development of culture-sensitive clinical teacher evaluation sheet in the Japanese context. Med Teach. 39(8):844–850.

- Kleijnen J. 2012. Internal quality management and organisational values in higher education; conceptions and perceptions of teaching staff [dissertation]. Maastricht: School of Health Professions Education/Heerlen; Zuyd University of Applied Sciences.

- Kleijnen J, Dolmans DHJM, Willems J, van Hout H. 2014. Effective quality management requires a systematic approach and a flexible organisational culture: a qualitative study among academic staff. Quality in Higher Education. 20(1):103–126.

- Knight PT, Trowler PR. 2000. Department-level cultures and the improvement of learning and teaching. Stud Higher Educ. 25(1):69–83.

- Lieff SJ, Albert M. 2010. The mindsets of medical education leaders: how do they conceive of their work? Acad Med. 85(1):57–62.

- Marsh HW. 2007. Students’ evaluations of university teaching: dimensionality, reliability, validity, potential biases and usefulness. In: Perry RP, Smart JC, editors. The scholarship of teaching and learning in higher education: an evidence-based perspective. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; p. 319–383.

- Martens SE, Meeuwissen SNE, Dolmans DHJM, Bovill C, Könings KD. 2019. Student participation in the design of learning and teaching: disentangling the terminology and approaches. Med Teach. 41(10):1203–1205.

- Martens SE, Wolfhagen IHAP, Whittingham JRD, Dolmans DHJM. 2020. Mind the gap: teachers’ conceptions of student-staff partnership and its potential to enhance educational quality. Med Teach. 42(5):529–535.

- McKimm J, Lieff SJ. 2013. Medical education leadership. In: Dent J, Harden RM, Hunt D, editor. A practical guide for medical teachers. London: Churchill Livingstone-Elsevier; p. 343–351.

- McKimm J, O’Sullivan H. 2016. When I say … leadership. Med Educ. 50(9):896–897.

- Meeuwissen SN, Stalmeijer RE, Govaerts MJB. 2019. Multiple-role mentoring: mentors’ conceptualisations, enactments and role conflicts. Med Educ. 53(6):605–615.

- Meeuwissen SNE, Gijselaers WH, Wolfhagen IHAP, Oude Egbrink MGA. 2020. How teachers meet in interdisciplinary teams: hangouts, distribution centers, and melting pots. Acad Med. 95(8):1265–1273.

- Newton J. 2000. Feeding the Beast or Improving Quality?: Academics' perceptions of quality assurance and quality monitoring. Quality in Higher Education. 6(2):153–163.

- Nordquist J, Grigsby RK. 2011. Medical schools viewed from a political perspective: how political skills can improve education leadership. Med Educ. 45(12):1174–1180.

- O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. 2011. Reframing research on faculty development. Acad Med. 86(4):421–428.

- Quinn RE, Rohrbaugh J. 1983. A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Manag Sci. 29(3):363–377.

- Overeem K, Wollersheim H, Driessen EW, Lombarts K, Van De Ven G, Grol R, Arah O. 2009. Doctors’ perceptions of why 360-degree feedback does (not) work: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 43(9):874–882.

- QAA. 2003. Handbook for enhancement-led institutional review: Scotland. Gloucester: Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education.

- Richardson V, Placier P. 2001. Teacher change. In: Richardson V, editor. Handbook of research on teaching. Washington (DC): American Educational Research Association; p. 905–947.

- Romme S, Bosveld MH, Van Bokhoven MA, De Nooijer J, Van den Besselaar H, Van Dongen JJJ. 2020. Patient involvement in interprofessional education: a qualitative study yielding recommendations on incorporating the patient’s perspective. Health Expect. 23(4):943–957.

- Sandhu D. 2019. Healthcare educational leadership in the twenty-first century. Med Teach. 41(6):614–618.

- Sargeant J, Mann K, Sinclair D, Van der Vleuten CPM, Metsemakers J. 2008. Understanding the influence of emotions and reflection upon multi-source feedback acceptance and use. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 13(3):275–288.

- Seale A. 2009. A contextualised model for accessible e-learning in higher education: understanding the students’ perspective. Berlin (Heidelberg): Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Sehlbach C, Govaerts MJB, Mitchell S, Teunissen TGJ, Smeenk FWJM, Driessen EW, Rohde GGU. 2020. Perceptions of people with respiratory problems on physician performance evaluation-a qualitative study. Health Expect. 23(1):247–255.

- Seldin P. 1999. Changing practices in evaluating teaching: a practical guide to improved faculty performance and promotion/tenure decisions. Vol. 10. San-Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass.

- Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DHJM, Wolfhagen IHAP, Muijtjens AMM, Scherpbier AJJA. 2008. The development of an instrument for evaluating clinical teachers: involving stakeholders to determine content validity. Med Teach. 30(8):e272–e277.

- Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DHJM, Wolfhagen IHAP, Muijtjens AMM, Scherpbier AJJA. 2010a. The Maastricht Clinical Teaching Questionnaire (MCTQ) as a valid and reliable instrument for the evaluation of clinical teachers. Acad Med. 85(11):1732–1738.

- Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DHJM, Wolfhagen IHAP, Peters WG, van Coppenolle L, Scherpbier AJJA. 2010b. Combined student ratings and self-assessment provide useful feedback for clinical teachers. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 15(3):315–328.

- Stalmeijer RE, Whittingham JRD, de Grave WS, Dolmans DHJM. 2016. Strengthening internal quality assurance processes: facilitating student evaluation committees to contribute. Assess Eval Higher Educ. 41(1):53–66.

- Strand P, Sjöborg K, Stalmeijer R, Wichmann-Hansen G, Jakobsson U, Edgren G. 2013. Development and psychometric evaluation of the undergraduate clinical education environment measure (UCEEM). Med Teach. 35(12):1014–1026.

- Sundberg K, Josephson A, Reeves S, Nordquist J. 2017. Power and resistance: leading change in medical education. Stud Higher Educ. 42(3):445–462.

- Sursock A. 2011. Examining quality culture part II: processes and tools-participation, ownership and bureaucracy. Brussel: EUA Publications. https://wbc-rti.info/object/document/7543/attach/Examining_Quality_Culture_Part_II.pdf.

- Svinicki MD, Marilla D. 2001. Encouraging your students to give feedback. New Dir Teach Learn. 2001(87):17–24.

- Tourish D. 2019. Is complexity leadership theory complex enough? A critical appraisal, some modifications and suggestions for further research. Organ Stud. 40(2):219–228.

- Uhl-Bien M, Riggio RE, Lowe KB, Carsten MK. 2014. Followership theory: a review and research agenda. Leadersh Quart. 25(1):83–104.

- van der Leeuw RM, Slootweg IA, Heineman MJ, Lombarts MJMH. 2013. Explaining how faculty members act upon residents’ feedback to improve their teaching performance. Med Educ. 47(11):1089–1098.

- van Lierop M, de Jonge L, Metsemakers J, Dolmans DHJM. 2018. Peer group reflection on student ratings stimulates clinical teachers to generate plans to improve their teaching. Med Teach. 40(3):302–309.

- Williams J. 2016. Quality assurance and quality enhancement: is there a relationship? Qual Higher Educ. 22(2):97–102.