?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Social media platforms have become common for engaging community stakeholders online in infrastructure projects. While online engagement can play a meaningful role in an infrastructure project’s value creation and distribution, limited empirical evidence exists on how infrastructure project organizations’ social media communication contributes to community stakeholders’ online engagement. This study applied uses and gratifications theory to examine the impact of infrastructure project organizations’ social media communication on community stakeholders’ online engagement. A mixed methods, theory-testing embedded case study was conducted, using social media messages from the project’s official Facebook pages as the primary data. Data were analyzed through generalized linear models, supplemented by qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews and project documents. The findings indicate that the project organization engaged the community stakeholders online through communication that disseminated timely information of the project’s value creation or included entertaining content. However, communication aimed at initiating dialogue, building relationships, and negotiating value creation terms did not engage the community stakeholders online. The study contributes to construction project management research as one of the first studies to empirically shed light on what kind of social media communication engages community stakeholders online, paving the way for future stakeholder engagement and sustainability practices in infrastructure project settings.

Introduction

Engaging with nonmarket stakeholders, such as local communities and authorities, interest groups and other non-governmental organizations, is crucial for ensuring that infrastructure projects deliver socially valuable and sustainable outcomes (Mathur et al. Citation2008). Stakeholder engagement, understood as the inclusion of diverse stakeholders in organizational activities (Greenwood Citation2007), is a continuous process and covers a wide range of practices from unidirectional sharing information to actual enfranchisement, where de facto decision-making authority is provided to the stakeholders (Klein et al. Citation2019, McGahan Citation2020). In practice, nonmarket stakeholder engagement can take place across various channels, platforms, and organizational interfaces (Chinyio and Akintoye Citation2008, Storvang and Clarke Citation2014, Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2020). Recently, the use of digital social media platforms has become common in infrastructure project contexts (Ram and Titarenko Citation2022), and the platforms have rapidly become a key channel for engaging particularly community stakeholders during the project implementation phase (Ninan, Clegg, et al. Citation2019, Ninan et al. Citation2020, Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2022). In the UK, for instance, the London Crossrail and High Speed Rail 2 project organizations use their official X (former Twitter) and Facebook accounts for transparent disclosure of information to their communities that spurs online discussions on these projects’ value creation.

Within construction project research, value creation with and for nonmarket stakeholders is receiving increasing attention, as the pressing societal and sustainability concerns and purpose of projects call for taking claims from different stakeholders into account and collaborating with them beyond the maximization of shareholder value (Gil Citation2022) – a perspective that has particularly been advanced by new stakeholder theory (McGahan Citation2021, Citation2023). Engaging particularly community stakeholders, who do not have an official or contractual link to the project organization but are the primary beneficiaries (or in some cases, sufferers of negative externalities) of the project, is especially relevant in the context of infrastructure projects to ensure sustainable value creation and the project’s social license to operate (Di Maddaloni and Davis Citation2017, Loosemore and Lim Citation2017, Derakhshan et al. Citation2019, Derakhshan and Turner Citation2022). That is, community stakeholders are an essential stakeholder group whose feedback and input (resources) are paramount for infrastructure projects’ joint value production. For example, empirical accounts of infrastructure projects provide evidence of community stakeholders’ demands for social responsibility, pursuit of social and environmental goals, and use of influencing mechanisms such as complaints, appeals, legal disputes, and protests (Di Maddaloni and Davis Citation2017, Nguyen et al. Citation2018, Unterhitzenberger et al. Citation2020), even in social media and online contexts (Williams et al. Citation2015, Lobo and Abid Citation2020, Ninan and Sergeeva Citation2022). If these are ignored, they can negatively influence value creation through suboptimal value creation proposition (Gil and Fu Citation2022).

Viewing infrastructure projects from a project value and stakeholder engagement perspective, social media platforms can therefore be conceptualized as places where value is both created and distributed between the project organization and community stakeholders’ exchanges (Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2022). For example, assuming that reasonable value related concessions have been made in the planning phase to the engaged community stakeholders, social media can be used in the implementation phase to keep the community engaged online and to make sure that the final distribution of value negotiated with these stakeholders is perceived fair. However, changes and unexpected events are likely to take place that may also require reopening the negotiation process and discussing, adjusting, or even redefining what value is and how it is created to maintain community stakeholders’ online engagement. But an infrastructure project organization may also need to be assertive occasionally and let the community know the boundaries of subsequent concessions to ensure they will not try to sabotage the project or make claims disproportional to what is at stake in the project. Social media platforms with their interactional features and tools, offer an appropriate channel for this kind of online engagement (Ram and Titarenko Citation2022). However, very few studies in the field of construction management have yet studied this topic.

Previous research on construction management has discussed and conceptualized the role of social media in stakeholder engagement, particularly in the context of infrastructure projects involving community stakeholders (Williams et al. Citation2015, Ninan, Clegg, et al. Citation2019, Lobo and Abid Citation2020, Ninan et al. Citation2020, Derakhshan and Turner Citation2022, Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2022, Toukola and Ahola Citation2022). This line of research has uncovered the benefits of social media (Toukola and Ahola Citation2022) and the typical roles that community stakeholders and project organizations can adopt on social media (Williams et al. Citation2015, Lobo and Abid Citation2020, Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2022). This research has also identified various higher level social media strategies (e.g. persuading, framing and hegemonizing strategies) and practices (e.g. promoting the organization, giving progress updates, and appealing to the community) for managing community stakeholders (Ninan, Clegg, et al. Citation2019, Ninan et al. Citation2020). Although this previous research has provided initial evidence of project organizations’ roles on social media and how social media platforms can be utilized for stakeholder engagement, very little empirical evidence has been documented of project organizations’ communication content (i.e. social media content) and its details (i.e. content strategies) that contribute to community stakeholders’ online engagement. The lack of knowledge is likely to complicate the efforts of project, communications, and PR managers to design effective social media content strategies for community engagement purposes and enhance infrastructure projects’ value creation. Against this background, the present study seeks to complement previous research by investigating the relationship between infrastructure project organizations’ social media content and community stakeholders’ online engagement. To that end, the study addresses the following research question: How does infrastructure project organization’s social media content contribute to community stakeholders’ online engagement?

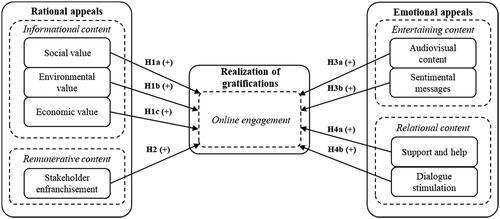

We approached the phenomenon from the perspective of uses and gratifications theory (UGT) (Ruggiero Citation2000), which argues that individuals (e.g. community stakeholders) consume media content (e.g. infrastructure project organizations’ social media messages) that satisfies their specific needs. Utilizing UGT and research and theory on stakeholder engagement, we theorized that communication that appeals to community stakeholders’ rational needs (i.e. informational or remunerative social media content) contributes positively to their online engagement. In this study, we approached online engagement from the behavioral perspective (Schivinski et al. Citation2016), which posits that online engagement is expressed through actions such as liking, commenting, and sharing. We further theorized that communication that appeals to community stakeholders’ emotional needs (i.e. entertaining or relational social media content) contributes to their online engagement positively.

To test our hypotheses, we relied on an embedded case study design (Yin Citation2015, p. 50) based on theory-testing case research and deductive reasoning (Ketokivi and Choi Citation2014). Specifically, we used generalized linear models (GLMs) to analyze Wall posts and comments (N = 824) from the official Facebook account of an infrastructure project (Tampere Tunnel) during the period of implementation (2014–2017). We followed the convergent parallel design to mixed methods research (Snelson Citation2016) by supplementing the quantitative analysis with qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews and project documents. The findings provide partial support for our theory, confirming that the project organization engaged the community stakeholders online through communication that appealed to their rational information and emotional entertainment needs. However, communication that sought to build relationships and negotiate value creation terms (remunerative content) did not engage the community stakeholders online. The findings were robust for alternative estimators.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. First, we derive and contextualize the key concepts of this study. We then outline UGT and derive contextualized hypotheses before describing the research design, methods, and analysis. The findings are then presented and discussed in light of previous research and theory to derive contributions. We conclude by outlining managerial implications, research limitations, and ideas for future research.

Conceptual background

There are two central conceptual approaches to community stakeholder engagement: first, viewing it as an organizational activity, and second, considering it as a stakeholder’s engaged state. These two approaches are derived and contextualized in the following two subsections.

Community stakeholder engagement as an infrastructure project organization’s practice on social media

The first approach related to organizational activity pertains to an infrastructure project organization’s social media communication, which is an organizational practice used to involve community stakeholders in the project’s online activities, being consistent with the dominant managerial definition for stakeholder engagement (Greenwood Citation2007, pp. 317–318). There are at least five degrees of engagement involved in this practice, informing, consulting, collaborating, co-deciding, and empowering (Luyet et al. Citation2012). Informing means that a project organization only offers information about the project to its community stakeholders with emphasis on one-way communication, whereas consultation means that a project organization presents the project to community stakeholders with the expectation of collecting input (e.g. suggestions, ideas, or opinions), which may or may not affect decision-making in the project. Collaboration is similar to consultation, but it assumes that the collected input affects decision-making. In co-decision, a project organization and community stakeholders work together to reach an agreement or a decision. Lastly, empowering means that a project organization delegates decision-making authority to community stakeholders.

Infrastructure project organizations often utilize informing, consulting, and collaborating as the most common degrees of engagement for community stakeholders (Chinyio and Akintoye Citation2008, Storvang and Clarke Citation2014, Loosemore and Lim Citation2017, Di Maddaloni and Davis Citation2018, Lehtinen, Aaltonen, et al. Citation2019, Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2020, Toukola and Ahola Citation2022). Co-decision and empowerment, the two highest degrees of engagement, allow community stakeholders to actively participate in the project’s decision-making, a concept referred to as stakeholder enfranchisement in new stakeholder theory (Klein et al. Citation2019, McGahan Citation2021). In our research context, an infrastructure project organization may choose to enfranchise community stakeholders on social media, as these stakeholders are the primary beneficiaries and possess thus valuable resources (e.g. inputs, ideas) for the project’s value creation (Gil Citation2023).

From an infrastructure project organization’s perspective, there are two primary modes of communication when engaging community stakeholders in the project’s social media activities: communicating to (stakeholder debate) and communicating with stakeholders (stakeholder dialogue) (Freeman et al. Citation2017, p. 7, Kujala and Sachs Citation2019). In stakeholder debate, organizations confront and defend their agenda to achieve own organizational objectives and see themselves in competition with other stakeholders (Kaptein and Van Tulder Citation2003). In so doing, organizations speak to influence their stakeholders and their behavior, reflecting the instrumental connotation of stakeholder theory. Stakeholder dialogue, in turn, means that organizations are constructive, focus on emphatic collaboration, exchange opinions, interests and expectations with other stakeholders, give voice to them, listen to their concerns, and seek to find mutually beneficial outcomes, reflecting the normative stance of stakeholder theory (Lehtimaki and Kujala Citation2017). Past research has recognized the strengths of stakeholder dialogue in stakeholder communication (Bebbington et al. Citation2007, Vinnari and Dillard Citation2016).

The degree of engagement significantly influences infrastructure project organizations’ mode of communication. For instance, stakeholder debate is the suitable mode when an infrastructure project organization aims to inform or consult community stakeholders. On the other hand, stakeholder dialogue becomes the preferred choice when the objective is to empower or co-decide with community stakeholders. In cases where the degree of engagement is collaboration, the appropriate mode—either stakeholder dialogue or debate—depends on whether the collaboration is authentic (normative engagement) or primarily serves the project organization’s objectives (instrumental engagement). The degree of engagement guides the project organization in selecting the most effective mode of communication for productive stakeholder interaction.

The degree of engagement and mode of communication together highlight the need to tailor communication channels, such as social media, to the uncertainty and equivocality of information to be processed for different stakeholders (Daft and Lengel Citation1986). In this regard, the use of different communication media affects the amount and richness of information that can be communicated, typically requiring a balance to be struck between the breadth and depth of communication (Daft and Lengel Citation1986). In our research context, the breadth of communication is related to the extent to which an infrastructure project organization communicates with different community stakeholders, while the depth of communication refers to the intensity with which the project organization communicates with a single community stakeholder (Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2022).

The characteristics and technological features of social media applications enable infrastructure project organizations to utilize all five degrees of engagement and both modes of communication (Ninan et al. Citation2020). Social media channels are computer-mediated technologies (Web 2.0-based applications, including but not limited to X, Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram) that enable the interactive creation and sharing of multiple types of information like audio, graphics, pictures, text and video in virtual networks and communities (Kietzmann et al. Citation2011). Social media are effective and efficient means of reaching a wide range of community stakeholders for whom social media are increasingly a natural way to communicate in construction projects (Williams et al. Citation2015, Lobo and Abid Citation2020), thus facilitating the achievement of the breadth of communication. For instance, X can be used to appeal to community stakeholders, to provide progress updates, to promote the project organization, and to deliver targeted marketing, helping to build a positive brand image and support for project activities (Ninan, Clegg, et al. Citation2019). Project organizations can also use social media for stakeholder dialogue purposes to exchange and accumulate knowledge (Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2022), facilitating the depth of stakeholder communication. For example, social media can be used for rapid communication between community stakeholders and project organization that accelerates the exchange of information and offers community stakeholders an easy way to participate in value creation activities (Toukola and Ahola Citation2022).

Community stakeholder engagement as a community stakeholder’s engaged state online

The second conceptual approach to community stakeholder engagement focuses on how the above defined organizational practice contributes to community stakeholders’ online engagement. Community stakeholders’ online engagement relates to the conceptualization of stakeholder engagement as an individual’s psychological stateFootnote1 that is achieved through a phenomenological experience (Brodie et al. Citation2011). A phenomenological experience means a personal, interactive experience with a specific engagement object (Brodie et al. Citation2019), which can include online content and interactions (Manetti and Bellucci Citation2016), and interpersonal and computer-mediated interactions (Brodie et al. Citation2013) and other stimuli. An engaged psychological state can include both rational and emotional attachments, like various feelings of satisfaction, to the engagement object (Brodie et al. Citation2011). The engagement agent in our study is the infrastructure project organization’s social media representative, and the engagement object is the specific piece of social media communication. Thus, through certain social media content and human-computer mediated interaction, a community stakeholder may reach an engaged state online that includes emotional or rational attachments to the project organization and its social media content.

Community stakeholders’ engaged state can manifest in many ways, but the three most common perspectives developed in consumer marketing research include behavioral, emotional, and cognitive perspectives (van Doorn et al. Citation2010), of which the behavioral perspective is most used in online engagement studies (Lim et al. Citation2022). The behavioral perspective posits that community stakeholders’ engaged state is expressed through actions such as viewing, liking, commenting, sharing, and creating content (Trunfio and Rossi Citation2021). Research tends to assume that an engaged state includes a positive sentiment (e.g. supporting the project). However, it can also encompass a neutral stance (e.g. not clearly against nor for the project) or a negative sentiment (e.g. against the project). It is important to consider that different actions constitute different levels of online engagement. Schivinski et al. (Citation2016) developed and verified the COBRA (Consumer Online Brand Related Activities) model that differentiates between three behavioral levels of online engagement: consumption, contribution and creation. Consumption constitutes the lowest level of online engagement, where community stakeholders express their engagement through passive viewing of the project organization’s social media content. In turn, contribution captures a more active level of online engagement, where community stakeholders contribute to the project organization’s communication by liking, sharing, and commenting on the contents. Lastly, creation includes the highest level of online engagement and manifests itself when community stakeholders spontaneously participate in the project organization’s content creation by creating project related content themselves.

Theory and hypotheses

UGT, social media communication and community stakeholders’ online engagement

UGT is a communication theory explaining that individuals use media content to satisfy their specific needs (Katz and Foulkes Citation1962). These needs are dichotomized into rational and emotional categories, where rational desires encompass informational or remunerative content, while emotional needs involve entertaining or relational content (Dolan et al. Citation2016). Failure to meet these needs may lead to individuals becoming exasperated and, consequently, abandoning the respective media (Palmgreen and Rayburn Citation1979). Originating from traditional mass media like radio and television (Ruggiero Citation2000), UGT has evolved with contemporary applications focusing on individuals’ usage of the internet, online gaming, social media, and mobile phones (Stafford et al. Citation2004, Wu et al. Citation2010, Grellhesl and Punyanunt-Carter Citation2012, Dolan et al. Citation2019). Business and management scholars have extended UGT’s application to understand organizations’ social media communication and stakeholders’ online engagement in distinct contexts, notably in consumer marketing (see, e.g. Dolan et al. Citation2019; Osokin Citation2019).

UGT is based on five key assumptions (Katz et al. Citation1973). The first assumption states that individuals are not only passive consumers but also active contributors (Ruggiero Citation2000). Social media functionalities and features allow community stakeholders to be highly active in contributing to project organizations’ content (e.g. liking and commenting on content), sharing it with other users and creating their own content (Smock et al. Citation2011). This aligns with the behavioral perspective on online engagement introduced in the previous section, which states that community stakeholders’ engaged state is expressed through actions such as viewing, liking, commenting, sharing, and creating content. The second assumption posits that individuals link gratification and media choice through a phenomenological experience (Dolan et al. Citation2019). This means that individuals can reach an engaged psychological state through the fulfillment of specific needs (i.e. rational or emotional as explained above) related to the content they use. Thus, UGT is consistent with the conceptual definition of online engagement, introduced in previous section, where community stakeholders can achieve an engaged state through a phenomenological experience including rational or emotional attachments to the organization’s social media content.

The third assumption asserts that the media competes with other sources of gratification (Katz et al. Citation1973). In the context of social media, this means that organizations must offer satisfying media content that is designed to appeal to their users’ rational or emotional needs (Malthouse et al. Citation2013). Otherwise, if the needs of individuals are not met, they become exasperated and will likely abandon the media in favor of competing gratifications (Palmgreen and Rayburn Citation1979). In our study context, the previous implies that an infrastructure project organization needs to carefully select the appropriate content (informational, remunerative, entertaining and/or relational), including suitable degree of engagement and mode of communication (introduced in previous section), when designing social media content to ensure that community stakeholders’ rational and/or emotional needs are satisfied.

The fourth assumption is a methodological, stating that the reasons for individuals’ media use can be derived from data supplied by the individuals themselves (Katz et al. Citation1973). In the context of social media, this means that collecting data (e.g. reactions, comments) from individuals yields information about their reasons for using the media. The fifth and final assumption is also methodological, asserting that when studying individuals’ use of media (Katz et al. Citation1973), value judgments about the cultural significance of media should be suspended. In the context of social media, this underscores the importance of directing the analysis towards individuals and their orientation rather than assessing the value of the media itself.

In the next subsections, we will formulate contextualized hypotheses concerning the four content types (informational, remunerative, entertaining, and relational) related to emotional and rational needs.

Project organization’s informational social media content and community stakeholders’ online engagement

Individuals who appreciate facts, logic, knowledge, and utility often seek and consume media content that is informational (Dolan et al. Citation2019). Informative media content provides users with factual and helpful information (Lee et al. Citation2018). Obtaining information is thought to be one of the main reasons for individual participation in social media (Dholakia et al. Citation2004). Such information may include knowledge about an organization, a brand, or products, prices, services, campaigns, events, and other items (de Vries et al. Citation2012). In practice, social media communication of informational content focuses on communicating to stakeholders at lower degrees of engagement, involving messages based on facts and logic that target the desired audience with knowledge-related information (Swani et al. Citation2017).

In the context of infrastructure projects, there is plenty of evidence that community stakeholders are interested in information about projects’ value creation and distribution (Di Maddaloni and Davis Citation2017, Citation2018, Nguyen et al. Citation2018, Derakhshan et al. Citation2019, Denny-Smith et al. Citation2020, Derakhshan and Turner Citation2022), which is primarily connected to social, environmental, and economic value of the project (Maddaloni and Sabini Citation2022). Hence, infrastructure project organizations can communicate information about project’s value creation via social media to satisfy community stakeholders’ needs for information and engage them online. Regarding social value, infrastructure projects offer significant social infrastructure, capital, benefits and impacts for community stakeholders (Eskerod and Ang Citation2017, Di Maddaloni and Davis Citation2018, Vuorinen and Martinsuo Citation2019, Maddaloni and Sabini Citation2022). For instance, new infrastructure, services, utilities, and jobs that are valuable to community stakeholders. Therefore, following UGT, an infrastructure project organization’s social media content related to social issues and the value generated by them should satisfy the community stakeholders’ needs and thus contribute to their online engagement. On that basis, we formulated the following hypothesis.

H1a: Infrastructure project organizations’ social media content about the project’s social value increases community stakeholders’ online engagement.

Infrastructure projects are also known to generate environmental concerns, such as site emissions, noise and air pollution, and natural resource expenditure, that are of relevance to community stakeholders (Aaltonen and Kujala Citation2010, Eskerod and Huemann Citation2014, Liu et al. Citation2018). However, infrastructure projects can also offer positive environmental outcomes, such as the development of green spaces and gardens and the use of environmentally sound technologies and materials (Lehtinen, Peltokorpi, et al. Citation2019, Maddaloni and Sabini Citation2022). These and other environmental issues have a key impact on the value created and distributed to community stakeholders and especially to those who live in the local area or those who are specifically interested in the environmental impacts and footprints of infrastructure projects in general (Vuorinen and Martinsuo Citation2019). Thus, following UGT, to increase community stakeholders’ online engagement, infrastructure project organizations should disseminate content including transparent information that addresses projects’ issues related to environmental value. On that basis, we formulated the following hypothesis.

H1b: Infrastructure project organizations’ social media content about the project’s environmental value increases community stakeholders’ online engagement.

Finally, infrastructure projects have significant economic impacts on community stakeholders due to their large budgets and extended duration (Williams et al. Citation2015, Ninan, Mahalingam, et al. Citation2019). For example, budgetary overruns negatively impact the value distributed to community stakeholders, who suffer economic losses because they effectively fund many infrastructure projects (Flyvbjerg Citation2014). Budgetary overruns may also result in reductions in the project’s scope, such as reduced social infrastructure, to balance financing, which also impacts the value generated for community stakeholders. Moreover, delays in the project schedule may have unintended environmental effects, such as further emissions and noise pollution that affect the value created for community stakeholders (Lehtinen, Aaltonen, et al. Citation2019). Conversely, if a project is successfully delivered under budget or ahead of schedule, there are positive impacts on the value created for community stakeholders. For example, public funds are saved without additional negative impacts on environmental or social value. Therefore, following UGT, an infrastructure project organization’s social media messages that include open and timely information about the project’s issues related to economic value should satisfy community stakeholders’ needs and increase their online engagement. On that basis, we formulated the following hypothesis.

H1c: Infrastructure project organizations’ social media content about the project’s economic value increases community stakeholders’ online engagement.

Project organization’s remunerative social media content and community stakeholders’ online engagement

Remunerative media content serves a utility function for the user (Dolan et al. Citation2016) that may include (but is not limited to) personal gains such as economic incentives and other individual benefits (Muntinga et al. Citation2011). Consumer marketing research has shown that remunerative content includes messages about giveaways, prize draws, bonus and loyalty schemes, price discounts, special offers, contests, votes, and sweepstakes (Cvijikj and Michahelles Citation2013). However, these are unlikely to be relevant to the present research context because infrastructure projects are not consumer goods, and it is unlikely that remunerative social media content offered by a project organization would include traditional forms of personal gain.

Nevertheless, there is evidence that utility may extend beyond mere personal gain. For instance, social media users may experience opportunities to influence organizational activities and value creation as remunerative (Füller Citation2006). These can include opportunities to vote for a company’s new product design or feature or opportunities to compete to develop a new logo for an organization. Community stakeholders of infrastructure projects are well known for their desire to seize opportunities to influence project’s value creation and distribution, e.g. through complaints, protests, appeals and other means (Aaltonen et al. Citation2015, Nguyen et al. Citation2018, Citation2019). These means serve a utility function and can be thus remunerative because they can impact the project’s value creation and distribution, e.g. in the form of changes related to environmental or social value components, from which community stakeholders benefit (Olander Citation2007, Lehtinen, Aaltonen, et al. Citation2019). Moreover, unexpected changes and events are likely to take place during the infrastructure project implementation that require project organizations to enfranchise community stakeholders and reopen the value creation process to negotiate, discuss, adjust, or even redefine what value is and how it is created, by whom, and who claims the value (Gil and Fu Citation2022, Gil Citation2023).

In the context of social media, the above means that infrastructure project organizations can timely focus on communicating with stakeholders at the highest degree of engagement and enfranchise community stakeholders when contextual conditions require it (e.g. due to unexpected changes or events) and offer opportunities to influence value creation to ensure that the final distribution of value negotiated with these stakeholders is reasonable. However, a project organization likely needs to be assertive and make the boundaries of enfranchisement rather strict so that community stakeholders will not try to sabotage the project or make disproportional claims. This is because during project implementation, major decisions have often been irreversibly locked-in (Flyvbjerg Citation2014), meaning that community stakeholder enfranchisement can realistically concern only minor to moderate project details.

Following the above analysis, community stakeholder enfranchisement via social media, for instance, through social media votes, contests, or requests for feedback and opinions that offer community stakeholders legitimate decision-making authority over certain issues of project’s value creation or distribution, should be remunerative to community stakeholders and thus satisfy their needs and increase their online engagement. On that basis, we formulated the following hypothesis.

H2: Infrastructure project organizations’ social media content that offers community stakeholders de-facto decision-making authority over specific issues of the project’s value creation or distribution increases the community stakeholders’ online engagement.

Project organization’s entertaining social media content and community stakeholders’ online engagement

Individuals who value emotional release through media often look for entertaining content (Dolan et al. Citation2019). ‘Entertaining’ refers to content that provides media users with fun and enjoyment, contributing to relaxation, hedonistic pleasure, aesthetic enjoyment, escapism, and emotional release (Eighmey and McCord Citation1998). There is evidence that entertainment is a key reason for consuming, creating, and contributing to organizational social media content (Lin and Lu Citation2011). Such content typically focuses on communicating to stakeholders at lower degrees of engagement, involving the use of audiovisual content and humor, often supported by emoji and emoticons to enhance affectivity (Muntinga et al. Citation2011).

In the case of infrastructure projects, there is also recent evidence of the importance of emotional issues in stakeholder engagement. Particularly, (Derakhshan and Turner Citation2022) derived the concept stakeholder experience from consumer marketing research, which highlights how stakeholders’ emotions and feelings play a key role in how they engage with a project organization. The importance of feelings and emotions in stakeholder engagement is also verified by the emotional perspective of online engagement studies (van Doorn et al. Citation2010, Schivinski et al. Citation2016). Thus, online engagement is not only about project organizations informing and enfranchising community stakeholders (H1-H2), but also about how issues are communicated to stimulate positive feelings and experiences among community stakeholders.

On social media, this kind of entertaining content primarily includes sentimental messages, such as humor (e.g. sarcasm, jokes), less formal content (e.g. emoji, memes) and other sentiments that consider community stakeholders’ feelings (Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2022). In addition to text-based content, this kind of content can consist of entertaining visualizations related to the project and its value (Turkulainen et al. Citation2015, Ninan, Clegg, et al. Citation2019, Ninan et al. Citation2020). For instance, 3D illustrations of the project’s plans or videos such as stylish/cinematic drone footage of a construction site can evoke positive emotions among community stakeholders and effectively communicate the progress and value of the project in an entertaining, engaging, informative, and transparent manner (Alin et al. Citation2013, Hietajärvi and Aaltonen Citation2018). Hence, based on the above analysis, an infrastructure project organization’s social media messages that are entertaining (i.e. sentimental text or entertaining audiovisual content), should appeal to community stakeholders’ emotions, stimulate positive feelings, and thus increase their online engagement. On that basis, we formulated the following hypotheses.

H3a: Infrastructure project organizations’ social media communication that offers entertaining audiovisual content increases community stakeholders’ online engagement.

H3b: Infrastructure project organizations’ social media communication that includes sentimental content increases community stakeholders’ online engagement.

Project organization’s relational social media content and community stakeholders’ online engagement

Relational media content offers social benefits and meets individuals’ social needs that include a sense of community and belonging (Osokin Citation2019). In practice, relational content typically focuses on communicating with stakeholders at higher degrees of engagement, providing opportunities for social interaction and integration, to connect with a community or social group, to share feelings, experiences, and views, and to seek support and help (relational value) (Muntinga et al. Citation2011, Dolan et al. Citation2016).

In infrastructure project setting, we can distinguish two types of relational content. The first relates to content that provides community stakeholders support and help with topical project issues. For instance, this type of content can include social media messages that provide community stakeholders customer support-oriented help, such as information about which project personnel to contact regarding topical project issues like changing traffic arrangements, improving sense of community and belonging (Ninan, Clegg, et al. Citation2019, Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2020). The second type relates to relational content that is based on the strengths of stakeholder dialogue (Bebbington et al. Citation2007, Eskerod et al. Citation2015, Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2022). Through stakeholder dialogue, infrastructure project organizations seek to build relationships and trust with community stakeholders, which are two key mechanisms that contribute to community stakeholders’ engagement and overall stakeholder experience (Mathur et al. Citation2008, Storvang and Clarke Citation2014, Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2020, Derakhshan and Turner Citation2022). For example, project organizations can provide relevant discussion topics related to topical project issues to stimulate dialogue and facilitate community stakeholders to share opinions and views and connect with each other and the project organization (Eskerod and Huemann Citation2014, Chow and Leiringer Citation2020). In addition, project organizations can openly address questions from the community stakeholders to build trust with them (Lehtinen, Aaltonen, et al. Citation2019, Chow and Leiringer Citation2020). Following the above analysis, project organizations’ social media messages that provide support and help (e.g. customer support-oriented help with topical project issues) or stimulate dialogue (e.g. by providing discussion topics or openly addressing community stakeholders’ questions) should foster a sense of community and belonging, satisfy community stakeholders’ social needs, and thus increase their online engagement. On that basis, we formulated the following two hypotheses.

H4a: Infrastructure project organizations’ social media content that offers support and help increases the community stakeholders’ online engagement.

H4b: Infrastructure project organizations’ social media content that stimulates dialogue with or among community stakeholders increases their online engagement.

integrates the hypotheses in a research model.

Empirical research methods

Research design

We adopted an embedded single-case design with two units of analysis (Yin Citation2015, p. 50): the project organization and the social media message. Our aim, following theory-testing case research and deductive reasoning (Ketokivi and Choi Citation2014), was to test the contextualized logic of UGT in relation to how an infrastructure project organization communicates in social media to engage community stakeholders online. The design met the duality criterion for case research (Ketokivi and Choi Citation2014), meaning that the hypotheses took account of the contextual idiosyncrasies of infrastructure projects, social media communication and community engagement while seeking for sense of generality by applying UGT.

The single case was based on the common case rationale (Yin Citation2015, p. 52), which captures the everyday circumstances of an infrastructure project organization in utilizing social media communication for community stakeholder engagement purposes. The common case is an excellent opportunity to illustrate the developed theory and test it for drawing insights about the phenomenon in general (Siggelkow Citation2007). In selecting the case, we used the following criteria: the case project’s organization must have been using social media actively, practically as its primary communication channel toward community stakeholders, and its implementation period must have been completed, so that all social media communication could be traced down, verified, and studied retrospectively. The selected case that met the above criteria was an infrastructure project in Finland called Tampere Tunnel.

Case context

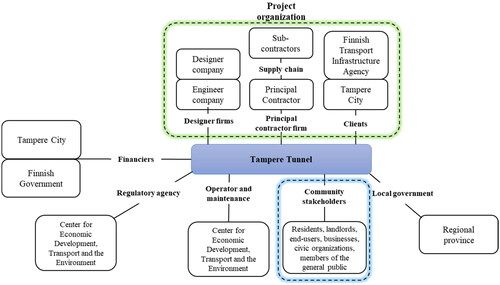

The objective of Tampere Tunnel was to reposition a 4 km stretch of highway (Finnish national road 12) in the urban area of Tampere City, and to construct the country’s longest tunnel (2.3 km). The project encompassed new interchanges and cloverleaf arrangements to connect the tunnel to the surrounding infrastructure, including various technical and functional systems and devices for safety, automation, control, and telecommunications. The project budget was €180.3 million, and it was implemented between 2014 and 2017. Tampere Tunnel was one of the first alliance projects in Finland. The project’s key stakeholders are presented in , with a focus on the project organization and community stakeholders in this study.

The project organization had established a dedicated communications team for managing all stakeholder engagement and communication. According to the original project plan, the team’s objectives that guided social media communication were:

Offer key stakeholders (e.g. inhabitants, housing associations) sufficient and timely information about the project, its progress, and effects

Improve the public image of the project

Support the progress of the project through communications

Be prepared for communications regarding disturbances

Gather and disseminate information regarding the environmental changes (effects on people and landscape)

Involve people.

This team included 7 people (Project Manager, Chairman of the Alliance Executive Team, Deputy Project Manager, and Public Relations Manager, Communications Director, and two communications personnel) who had divided responsibilities and roles for managing the project’s different communication channels. The Public Relations Manager (interviewee No. 7 in Appendix ) was in charge of social media communication. The official project plans emphasized community engagement and inclusion of community stakeholders’ values as key project objectives. The project objectives related to community stakeholders included indicators, such as positive publicity, that were measured and used to continuously develop engagement and communication activities.

The communications team established the project’s official Facebook account at the beginning of the implementation period and actively used it for community engagement purposes, posting at least once every day (excluding holidays) until completion. Since the project organization had no other active social media channels, community stakeholders also adopted Facebook as the main point of online contact. There were also other communication channels that supported the use of Facebook in the project such as public events, meetings, workshops, and conventional media but they were used less frequently.

The social media account had over 2,000 followers by the end of the project completion in early 2017. The number of followers increased rapidly from the beginning of the project implementation period in late 2014 and reached saturation in early 2015, with a significant drop in the rate of new followers per week. The number of Facebook reactions, comments and shares from community stakeholders also grew steadily over the years (see descriptive statistics in Appendix ). The number of community stakeholders’ contributions to the project organization’s single Wall post relative to followers was around 5–10% (i.e. number of “active users”). For comparison, around two times larger (in terms of budget, but scope is even larger) infrastructure project in Finland, Raide-Jokeri, has around 4,200 followers on Facebook which is twice the number in our case project (as of early 2023). Also, the significantly larger (over 200 times the budget and scope) High Speed Rail 2 project in the UK has around 19,000 followers on Facebook (as of early 2023). In both these projects, the number of community stakeholders’ contributions to a single Wall post relative to followers is also around 5–10% (i.e. number of “active users”), so we are confident that the case project represents a “common” case.

The case project’s community stakeholders predominantly interacted and demonstrated their online engagement by reacting to the project organization’s social media content with Facebook reactions. While community stakeholders also initiated their own discussion topics, posed questions, and provided open feedback to the project organization, it was evident that majority of the interaction took place through Facebook reactions. Our investigation of the community stakeholder demographics revealed that most members belonged to the project’s local community. We also found that the relationship between the community stakeholders and the project organization was generally co-operative, with only a few opposing members. We also investigated a random sample of the community stakeholders’ accounts and found that the community consisted mostly of private persons and a few NGOs and firms.

Our analysis also showed that vast majority of the interaction between the project organization and community stakeholders took place on the project organization’s Facebook pages rather than the community stakeholders’ Facebook pages. The community stakeholders did not have a single dedicated Facebook page/user account for coordinating their activities. While there were occasional “unofficial” or parallel discussions on other Facebook pages/accounts (e.g. a community stakeholder reposting/sharing the original messages or tagging the project organization’s account on another page/Wall post and initiating discussion), these did not attract significant interaction. For instance, 73% of the project organization’s Facebook messages had zero shares/reposts, or user tags. Additionally, 14% of the messages had a single share/repost, or user tag. There were only some cases with more than two shares/reposts, or user tags, with the highest recorded being 27. Hence, the outreach beyond the project organization’s official Facebook pages was exceedingly limited. It thus seems that community stakeholders’ online engagement behavior was mainly at the consumption and contribution levels (Schivinski et al. Citation2016). Therefore, we decided to limit our analysis to the official account of the project organization.

Facebook as a medium for stakeholder communication and online engagement

Facebook is one of the largest social networking sites, which allows community stakeholders to interact with each other and the infrastructure project organization. Community stakeholders can list personal information on their profile page, which can be designated as private (visible only to connected users) or public (visible to anyone). In turn, the project organization can list basic information about itself on its profile page. Facebook allows project organizations to publish content that may include pictures, videos, music, articles, or text as “Wall posts” in their “timeline”, which shows all published Wall posts in chronological order. Community stakeholders can see the project organization’s latest Wall posts in their “feed”, which consists primarily of other connected users’ latest posts and advertisements.

The project organization interacts with its community stakeholders primarily through Wall posts on its pages. Community stakeholders who have clicked “Follow” on the project organization’s profile page become members of its social media community and can see its Wall posts on their timeline. Community stakeholders can interact with Wall posts through three unique tools: reactions, shares, and comments. Reactions include six different animated emoji (Like, Love, Haha, Wow, Sad, Angry) that allow community stakeholders to express their engagement. In addition, they can initiate discussion by writing comments to which other community stakeholders and the project organization can reply with follow-up comments. Comments are primarily text-based but can also include links, pictures, video, emoji, music, and articles. Community stakeholders can also share the Wall post content with their own social group by clicking the “Share” feature or by leaving a comment that “tags” it for specific users. Community stakeholders can also initiate discussion with the project organization by leaving a Wall post on its timeline.

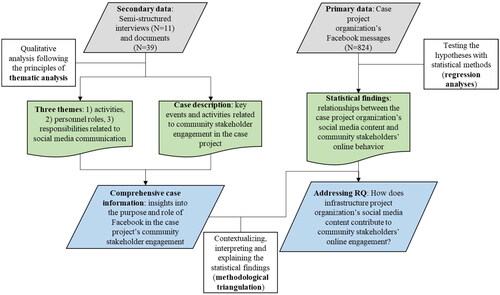

Data collection

The case study followed the convergent parallel design to mixed methods research (Snelson Citation2016) and employed three methods of data collection, social media data, semi-structured interviews, and documents. summarizes the convergent parallel design research process in the form of a flowchart. Social media data served as the primary data for testing the hypotheses, while interviews and documents provided secondary data to develop a comprehensive understanding of the case project, particularly with regard to community stakeholder engagement and the role and use of social media, enabling interpreting and explaining the quantitative findings further (i.e. methodological triangulation). Semi-structured interviews and documents are valid methods in case studies (Yin Citation2015, pp. 107–113), and social media data as an online naturalistic method of inquiry is increasingly used, as it is free of biases such as researcher bias and Hawthorne effect (Ninan Citation2020).

The primary data were collected from Tampere Tunnel’s official Facebook account’s webpages.Footnote2 The project organization’s every Wall post (n = 564) and comment (n = 260) was systematically gathered from the account’s timeline in chronological order throughout the project implementation period. Raw messages, including text, pictures, videos, and links, were copied and coded as raw content. The date was then coded as day/month/year, and post type was coded as either Wall post or comment. This resulted in N = 824 messages, which were stored as a database.

The secondary data (11 semi-structured interviews, 39 documents) including interview protocol has been summarized in Appendix . We interviewed several key organizations and personnel in different roles from the project organization to cover a wide range of viewpoints to community stakeholder engagement. We interviewed the key personnel from the communications team: Project Manager, Public Relations Manager, Chairman of the Alliance Executive Team, and Deputy Project Manager. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. We selected interviewees using purposive sampling (Robinson Citation2014) to ensure that the informants were knowledgeable about the project and its community stakeholder engagement. The interviews were typical for a case study, including a relaxed atmosphere and open-ended questions with a focus on the interviewee’s own voice and viewpoints.

In addition to interviews, we systematically gathered publicly available electronic documents related to the project. The documents helped us to triangulate the interview data and deepen our understanding of the case and its context. The documents included original project plans and reports that were openly accessible online (Client’s webpages). We also searched online news articles from regional and national media and news companies’ webpages and from relevant national trade journals’ webpages. All identified articles were assessed for their relevance, and those that did not relate to the project were excluded (e.g. articles merely mentioning the project’s name but in reality, addressed something else).

Study variables and measures

Independent variables

To measure informational content associated with H1a–H1c, we relied on the categorical variable publication topic, which is a metric developed and tested specifically to measure the content of social media communication (Bonsón and Ratkai Citation2013, Bonsón et al. Citation2015). Publication topic encompasses seven topics about which organizations disclose information online: social issues, environmental issues, marketing issues, financial issues, governance and management issues, customer support, and other. The first author coded the raw content in terms of these categories, treating them as non-mutually exclusive. After pilot coding 150 messages, the second author reviewed the coding and an author meeting was held to discuss and reach a consensus about three necessary amendments to adjust the coding categories to the idiosyncrasies of infrastructure projects. First, the financial and marketing categories were combined as economic issues, as the focus on financial transparency or marketing project progress alone failed to capture the content associated with H1c. Second, a technical issues category was added to capture messages about specific technical solutions. Finally, the other category was excluded, as the revised categories adequately captured informational content.

To measure remunerative content related to H2, we derived the dichotomous variable enfranchisement opportunity from conceptualizations of remunerative content in existing research (Ashley and Tuten Citation2015, Dolan et al. Citation2019) with the help of stakeholder research and conceptualization of stakeholder enfranchisement (Klein et al. Citation2019, Gil Citation2023). This variable measures whether a message enabled community stakeholders to influence project implementation and value creation through de facto decision-making authority—for instance, by inviting them to vote or decide on specific project activities. Messages that provided these opportunities were coded 1 while messages that did not were coded 0.

We relied on two variables to measure entertaining content related to H3a and H3b. Based on previous research, we first derived the categorical variable audiovisual to measure whether a message includes entertaining audiovisual content (videos or pictures) (Jahn and Kunz Citation2012, Sabate et al. Citation2014). The second was the dichotomous variable sentiment, which we derived from previous conceptualizations (de Vries et al. Citation2012, Cvijikj and Michahelles Citation2013, Dolan et al. Citation2016). Messages that included sentiments (e.g. humor, jokes, sarcasm), possibly supported by emoji or memes, were coded 1 while messages that did not were coded 0.

To measure relational content related to H4a, we relied on the customer support category of the publication topic variable, which captured messages offering general support and help. To measure content related to H4b, we derived the dichotomous variable dialogue stimulation from existing conceptualizations of relational media content (Lovejoy et al. Citation2012, Citation2012, Viglia et al. Citation2018) with the help of stakeholder communication research and conceptualization of stakeholder dialogue (Kujala and Sachs Citation2019, Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2022). Messages that sought to stimulate dialogue (two-way communication) with or responses from the community stakeholders by means of questions or discussion topics were coded 1 while messages that served merely to inform the social media community were coded 0. To avoid multicollinearity issues, those messages that enfranchised community stakeholders (H2) were coded 0 for dialogue stimulation (H4b).

For clarity and transparency, Appendix provides measurement examples regarding the independent variables.

Dependent variable

To measure the community stakeholders’ online engagement, we relied on the behavioral perspective of online engagement, specifically focusing on the contribution level. This measures how users actively engage online with an organization’s communication by liking, sharing and commenting on the contents (Schivinski et al. Citation2016, Lim et al. Citation2022). We calculated an aggregate and continuous variable, online engagement (= N of Facebook reactions [Likes + Love + Haha + Wow + Sad + Angry] + N of Shares [Shares/reposts + user tags] + N of Comments), based on the sum of three verified indicators commonly used in existing online engagement research (Lovejoy et al. Citation2012, Sabate et al. Citation2014, Bonsón et al. Citation2015, Manetti and Bellucci Citation2016, Dolan et al. Citation2019, Osokin Citation2019). The first indicator was the number of discrete Facebook reactions to a message. Because the Facebook update that introduced six different reactions was launched during the project implementation period, the six were added up as one indicator. Only some of the data included this update while most of the data included the old “Like” reaction. Even after the Facebook update, the vast majority of reactions were Likes. The second indicator was number of comments on a message, and the third indicator was number of shares including user tags on a message. This aggregate measure focuses on the project organization’s breadth of communication and fails to capture the depth of communication.

Control variables

We also included four control variables. First, we controlled for message length, calculated as the continuous variable message length (based on the number of characters) because longer messages that contain more content may increase the number of reactions and comments (de Vries et al. Citation2012, Sabate et al. Citation2014). To avoid bias, we subtracted links from the length. Second, we controlled for communication tone, as this can influence social media engagement behavior (Manetti and Bellucci Citation2016, Manetti et al. Citation2017, Etter et al. Citation2019). Specifically, distinct topics are often discussed in different tones, and the number of reactions and comments may depend on that tone. This was coded as a categorical variable based on a generic semantic analysis of Neutral, Positive, or Negative, treating the categories as mutually exclusive, with Neutral as the baseline. Third, Publication day was added as a dichotomous control variable, coding weekdays (Mon-Thu) as 1 and weekends (Fri-Sun) as 0 because this may influence the number of reactions and comments (Cvijikj and Michahelles Citation2013, Sabate et al. Citation2014, Dolan et al. Citation2019). In particular, messages created on weekdays may increase the number of reactions and comments, as most activities on Facebook occur during working days. This also means that project organization likely communicates more actively during weekdays compared to weekends. Fourth, publication year was added as a dummy control variable following initial regression analyses because the different phases of project implementation (e.g. early implementation vs. near completion) may influence community behavior and project organization’s communication (Aaltonen and Kujala Citation2010, Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2022).

Data analysis

The data analysis comprised two parallel phases (see for a summary). In the first phase, we carefully analyzed the secondary data, including interview transcripts and documents, to develop a profound understanding of the case context and research phenomenon, being instrumental for the second phase. The primary purpose of this first phase was methodological triangulation: to enable interpreting, contextualizing and explaining the subsequent statistical findings. Initially, we studied the secondary data to generate a comprehensive case description, highlighting key events and activities related to community stakeholder engagement. Following the principles of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), we focused on the identified communication team responsible for community stakeholder engagement in the project. From this analysis, we derived three themes pertaining to its 1) activities, 2) personnel roles, and 3) responsibilities related to social media communication. These themes offered insights into the purpose and role of Facebook in the case project’s community stakeholder engagement, facilitating the contextualization, interpretation, and explanation of the statistical findings in the subsequent second phase.

The second phase included testing the hypotheses with statistical methods by using the primary data (Facebook data). We began our data exploration and diagnostics by testing for variation in online engagement over years using mixed effects regression models (ICC ∼ 0.002) that indicated no such variation and confirmed that other estimators could be used. Mixed effects regression models were also tested for variation between Wall post and comment level (ICC ∼ 0.74); as this indicated variation between the levels, we utilized two subsamples: Wall posts (n = 564) and comments (n = 260). We then continued with multiple linear regressions (MLR) to further explore and diagnose the data. MLRs confirmed heteroskedasticity (megaphone opening right) and non-normality (positive kurtosis and skewness to the right) of residuals. While heteroskedasticity could be resolved with robust standard errors, it does not resolve the non-normality issue (i.e. nonlinear relationship between the dependent and independent variables). We also tried a natural logarithm transformation to model the dependent variable as a nonlinear function of the independent variables, which resolved the issues and provided a well specified model (R2 = 0.346): F-test null hypothesis rejected (F(20, 543) = 14.35, Prob > F = 0.000), normality of residuals confirmed (Kernel density, a very slight kurtosis (3.89) and positive skew (0.24)) and no multicollinearity (Mean VIF = 2.17), omitted variable (Ramsey RESET test result (Prob > F = 0.2314)) or heteroskedasticity issues (visual check of residuals vs. fitted values). However, transforming dependent variable is inferior to GLMs (Rönkkö et al. Citation2021).

Next, we explored GLMs. In this study, the functional form (i.e. link function) is not determined by previous theory and since the model includes mostly binary and categorical variables, it is difficult to determine it empirically with diagnostics and plotting. However, Poisson regression has been demonstrated to produce consistent estimates regardless of the actual distribution, especially with count data (such as in our study), and it should be used as the default choice because of its more general consistency (Wooldridge Citation2015, chapter 17.3). Also, consistency of estimates is more important than possible overall model fit (Rönkkö et al. Citation2021), thus favoring Poisson over negative binominal or other GLMs in this study. Therefore, we selected Poisson regression as the final estimator. To test the hypotheses, we constructed the following Poisson regression model with robust standard errors:

(1)

(1)

The Stata/MP 17.0 statistical software package was used to run the analysis.

Research findings

Analysis of comments subsample

The Poisson regression analysis for the comments subsample resulted in a completely misspecified model that failed to reject the null hypothesis that all of the coefficients of independent variables are equal to zero. We also tested Negative binominal, MLR and MLR with transformed dependent variable, but all the models were completely misspecified. Thus, we rejected any further interpretation of the findings for this subsample.

One likely explanation is that the project organization’s communication at comment level was purely reactive—that is, its comments are responses to queries from community stakeholders who have already chosen to communicate about the specific content. As such, these responses are not necessarily designed to engage all community stakeholders. For this reason, it is likely that the project organization’s comments do not attract reactions, comments, or shares in the same way as Wall posts, which are designed to engage the wider audience. Consequently, comment-level communication does not reflect our assumptions about the phenomenon, and we cannot interpret the findings for this subsample.

Poisson regression model for Wall post subsample

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the variables for the Wall post subsample are presented in Appendix , respectively. reports the Poisson regression model results for the Wall post subsample.

Table 1. Poisson regression model for Wall post subsample.

The analysis fully supports H1a; the project organization’s Wall posts regarding social value have a positive (coeff. 0.347) and significant (p < 0.01) relationship with online engagement, indicating that Wall posts about social issues increase reactions, comments and shares from the community stakeholders by 41.5% ((e0.347-1) × 100%). The analysis offers only partial support for H1b; as anticipated, the project organization’s Wall posts about environmental value exhibit a significant (p < 0.01) relationship with online engagement, but the effect is negative rather than positive (coeff. −0.422). This means that Wall posts about environmental issues reduce reactions, comments and shares by 34.4% ((e−0.422-1) × 100%), rejecting H1b. The analysis offers only partial support for H1c, and it is therefore rejected. Even though the proposed direction of effect is confirmed (coeff. 0.102) with an effect size of 10.7% ((e0.102-1) × 100%), messages about economic value did not exhibit a significant (p = 0.274) relationship.

The analysis provides partial support for H2. Project organization’s Wall posts offering enfranchisement opportunities have a significant relationship with online engagement (p < 0.01), however, as the effect is negative (coeff. −1.554), this means they reduce reactions, comments and shares by 78.9% ((e−1.554-1) × 100%), and H2 is therefore rejected.

The analysis provides full support for H3a and H3b. Project organization Wall posts that include an entertaining picture (coeff. 0.47, p < 0.01) or a video (coeff. 1.125, p < 0.01) increase reactions, comments and shares by 60.0% ((e0.47-1) × 100%) and 208.0% ((e1.125-1) × 100%), respectively. Project organization Wall posts that include sentiments have a positive (coeff. 0.344) and significant relationship (p < 0.1) with online engagement, indicating that sentimental messages increase reactions, comments and shares by 41.1% ((e0.344-1) × 100%).

The analysis offers partial support for H4a. Wall posts that provide general support and help have a significant (p < 0.01) but negative (coeff. −0.396) relationship with online engagement—that is, they reduce reactions, comments and shares by 32.7% ((e−0.396-1) × 100%)—and H4a is therefore rejected. The analysis offers no support for H4b, and it is therefore rejected. Interestingly, messages that stimulated dialogue did not exhibit a significant (p = 0.398) relationship or proposed direction of effect (coeff. −0.148, meaning the effect size is −13.8% ((e−0.148-1) × 100%)).

It is also worth mentioning that Wall posts about the project’s governance and management issues have a significant (p < 0.05) but negative (coeff. −0.373) relationship with online engagement—that is, they reduce reactions, comments and shares by 31.1% ((e−0.373-1) × 100%).

Robustness tests for Wall post subsample

To test the robustness of our findings, we checked four relevant issues (see Appendix for all robustness test models). First, we utilized negative binominal regression (model M2) and MLR with transformed dependent variable (model M3) (natural logarithm) as alternative estimators to account for the nonlinear relationship between the dependent and independent variables. Second, we included a transformed MLR model without the independent variables enfranchisement opportunity and dialogue stimulation (model M4) that had low mean values in the sample, possibly causing bias in the estimates. Third, we included an MLR model without the control variable publication year (model M5) which had a higher VIF value than other variables (the only VIF value over 2.75), possibly causing collinearity bias. Fourth, we included two Poisson regression models with alternative dependent variables to ensure that our findings are robust, considering different measurements of online engagement used in previous online engagement studies (see, e.g. Dolan et al. Citation2019). The first model included only Facebook reaction Likes (model M6), while the second included a sum of Likes, Shares [Shares/Reposts + User tags] and Comments as the dependent variable (model M7).

Table A5. Robustness tests for wall post subsample.

The robustness checks yielded very similar findings except for three issues (see Appendix ). First, robustness test models M2-M5 yielded a significant relationship for economic issues with around the same effect size and direction, hinting that while the Poisson model gave an insignificant relationship with positive effect, there might in fact be a meaningful positive relationship between economic value and online engagement. Second, robustness test models M2-M5 yielded a significant and positive relationship for messages that included links, suggesting that the inclusion of links can enhance community stakeholders’ online engagement. In this case study, the explanation may be that the links were often associated with entertaining or informational content—for example, YouTube links to drone flights or visual information about topical project issues—offering further support for H1a-c and H3a. Third, robustness test models M2-M5 yielded an insignificant relationship between governance and management issues and online engagement, although the effect direction remains negative as in the Poisson model. Finally, it is worth noting that models M6 and M7, utilizing alternative dependent variables, yielded the same findings as the primary model, providing evidence of the robustness of the measurement for Online engagement.

Discussion and contributions

The present study provides insights into the types of social media content that infrastructure project organizations can emphasize on Facebook to enhance community stakeholders’ online engagement. Additionally, the findings illuminate the kinds of content that may not effectively engage community stakeholders online. Our discussion is structured into three subsections below, delineating the specific contributions of this study to construction project management research.

Project organizations engage community stakeholders online through information dissemination and entertainment

The present analysis reveals that social media communication which included informational and entertaining content related to value generated and distributed by the project increased community stakeholders’ online engagement. Similar findings related to informational and entertaining content have been found in other organizational contexts (see, e.g. Dolan et al. Citation2019, Osokin Citation2019). While previous construction management research has conceptualized the role of social media communication in stakeholder engagement (Williams et al. Citation2015, Ninan, Clegg, et al. Citation2019, Lobo and Abid Citation2020, Ninan et al. Citation2020, Pascale et al. Citation2020, Derakhshan and Turner Citation2022, Lehtinen and Aaltonen Citation2022, Ninan and Sergeeva Citation2022, Ram and Titarenko Citation2022, Toukola and Ahola Citation2022), the influence of project organizations’ social media content on nonmarket stakeholders’ online engagement has not previously been analyzed in detail. We contribute to this discussion as one of the first studies to empirically shed light on what kind of social media content on project’s value creation and distribution engages community stakeholders online. This paves the way for future stakeholder engagement and sustainability practice in infrastructure project settings. Moreover, detailed empirical examinations of stakeholder communication are overall limited in stakeholder theory and research (Freeman et al. Citation2017, Kujala and Sachs Citation2019). Therefore, our study offers valuable insights into how organizational communication engages community stakeholders online in the context of infrastructure projects and social media.

Regarding informational content, our findings suggest that communication on the project’s social and economic value increases community stakeholders’ online engagement. This aligns with the communications team’s objectives and with previous evidence that community stakeholders expect information on social and economic value generated by the project (Di Maddaloni and Davis Citation2017, Lehtinen, Aaltonen, et al. Citation2019, Vuorinen and Martinsuo Citation2019). Nevertheless, our findings did not support H1b that communication about environmental value would increase social media community stakeholders’ online engagement even though disseminating information about disturbances and environmental changes was one of the main aims of the communications team. As most of this content could be described as negative—providing information about noise, emissions, traffic interruptions, and other disturbances caused by the project—these issues did not attract many reactions, comments or shares from the social media community but were instead treated in a more neutral and passive way. This is an interesting finding, in that transparent communication about challenging or harmful issues did not increase community stakeholders’ online engagement as might have been expected in light of the potentially negative consequences for them (Di Maddaloni and Davis Citation2018, Liu et al. Citation2018).

The following are two possible explanations for the above observation. First, the project phase may have had some effect, as stakeholders typically believe that their capacity to influence environmental value is lower during the implementation phase of infrastructure projects (Aaltonen and Kujala Citation2010) as compared to the design phase, for example, when many environmental value related issues are still open for debate. Secondly, as the case project’s environmental value was not particularly controversial during the implementation period, the project organization’s relationship with the social media community was relatively cooperative. Consequently, community stakeholders tended to seek consensus rather than feeling any urgent need to mobilize or to criticize communication about environmental value. If the environmental situation was more controversial, stakeholders might well have reacted more intensively to strengthen their collective identity as potential opponents of the project (Rowley and Moldoveanu Citation2003, Liu et al. Citation2018, Nguyen et al. Citation2018, Citation2019).