Abstract

This study explored online group clinical supervision participation, as a component of pre-registration education following mental health nursing students’ clinical placements. Clinical supervision has historically been valued as a supportive strategy by healthcare professionals to develop practice and competence and prevent burnout. As many student nurses do not have access to clinical supervision via practice areas as a standardised process, their experiences of engaging in or benefitting from clinical supervision are wide-ranging. In view of this, we are identifying a theory-practice gap between theoretical knowledge and practice experience. This study incorporated a qualitative inquiry using reflexive thematic analysis and applying poststructural theoretical perspectives. Online group clinical supervision was delivered to student mental health nurses whereby focus groups followed to discuss their views, understandings and experiences of online group clinical supervision. This was against a back drop of Covid-19 lockdown restrictions. Thematic synthesis identified two main areas for improving participation and pedagogy comprising; Improving Confidence and Trust in (Online) Participation and The Need for Familiarity in CS Participation and Understanding. Thematic and poststructural analysis demonstrated participants’ positive outlooks on the values of clinical supervision, whilst also identifying the finer nuances of the differences in accessing group clinical supervision through an online format. This study adds to the literature on using group clinical supervision within the student mental health nurse population by identifying the benefits of group clinical supervision for student nurses. It has additionally found that the silences and inhibitions surrounding online participation are important areas for further research.

Introduction

In the UK, the supervision of student nurses in pre-registration education is currently discussed in the context of the Standards for Student Supervision and Assessment (Nursing & Midwifery Council, 2018) which have been in effect since 2019. The standards set out the expectations for the learning, support and supervision of students in the practice environment. However, the classification of “supervision” holds many forms and further clarification of the type of supervision being offered should be clear and accessible when introducing supervision systems (Howard & Eddy-Imishue, Citation2020; Victorian Government, Citation2018). Different forms of supervision can include; managerial, safeguarding, clinical, restorative, reflective and developmental, as well as practice supervision towards proficiency development within student nurses’ practice placements. Often these terms are used interchangeably blurring the underlying purpose and meaning of supervision in practice, which can in turn affect the participation, quality, clarity and aims of the supervision that is being offered or implemented.

From an academic perspective, students are allocated both personal and academic supervisors to support them in their studies with the aim of keeping the academic progress and personal support supervision distinct. From the perspectives of a personal and academic supervisor, this is a difficult balance to effectively achieve as both aspects often intertwine. Whilst a student is undertaking a clinical placement, the student will continue to receive support from an academic and a personal supervisor, and it is debateable who is in the more relevant position to be offering supervision to the student nurse.

For the purposes of this article, we are referring to the term clinical supervision (CS) which has been described as “a formal process of professional support and learning which enables individual practitioners to develop knowledge and competence, assume responsibility for their own practice and enhance consumer protection and safety in complex situations” (Royal College of Nursing [RCN], 2003, p. 3). In addition, we are integrating the restorative function of CS in our supervision approach to balance personal stress which in turn can positively affect work performance (Brunero & Lamont, Citation2012; Rothwell et al., Citation2021; Wallbank, Citation2013). Though CS has historically been valued as a supportive strategy by healthcare professionals (Proctor, Citation1986) and a means of preventing burnout (Rothwell et al., Citation2021; Wallbank, Citation2013), there remains problems in its implementation across healthcare services. Recent research points to problems continuing around poor experiences of CS and limited evidence of its successful implementation, uptake and impact (Masamha et al., Citation2022).

Initiatives such as the Professional Nurse Advocate (NHS England, Citation2021) reinforces the importance of good quality CS and provides active leadership for participation in CS by training nursing staff to become clinical supervisors. This initiative is beneficial for nursing professionals and identifies: “It is of particular relevance to all nurses and student nurses” (NHS England, Citation2021, p. 5), however this is incongruous to what student nursing populations have experienced in practice, which is a lack of an identified process to access CS. This is concerning considering Health Education England [HEE] (Citation2019) identified in their “NHS Staff and Learners” Mental Wellbeing Commission’ report, the importance of reducing stress for student nurses pre and post undergraduate health care education.

In recognition of the shortfall in providing formal, widespread CS for student nurses, this study addresses the gap in formal CS support for (mental health) student nurses by investigating online group CS provision and participation, as a component of pre-registration education following clinical practice placement experiences. This was facilitated by academic programme lecturers and was amidst the Covid-19 pandemic.

The pedagogy of clinical supervision in mental health nursing and pre-registration education

Though early seminal work referred to concepts of supervision (see Kolb, Citation1984; Proctor, Citation1986), CS did not receive significant recognition of its value in the UK until the 1990s with Butterworth and Faugier (Citation1992) advocating its values and use. Studies have investigated how CS supports graduate nurses and identified its importance in managing stress and retention (Cummins, Citation2009; HEE, Citation2019; Wallbank & Hatton, Citation2011), however these studies have involved all nursing fields and not focussed primarily on the field of mental health. The field of mental health nursing internationally and especially in the UK and Scandinavia; have been early adopters of CS (White & Winstanley, Citation2010), recognising the benefits of CS in providing support and a protected space for reflection. In their integrative review, Howard and Eddy-Imishue (Citation2020) highlighted many positive outcomes for the use of CS in mental health nursing such as reduction in staff burnout, safer practice, developing competencies, problem solving, support in complex decision making, improved patient outcomes and retention of staff, however it was indicated that further development is required to understand participation barriers, especially within inpatient mental health nursing. Furthermore, it was concluded that to implement CS effectively, a personal and organisational needs analysis is required rather than utilising a one size fits all approach. It follows that expecting all clinical placement areas to role model successful systems of CS is currently unrealistic, and pre-registration nursing education can support in building both knowledge and skills in what effective CS looks like for the future registered mental health nursing workforce. Within this dynamic, we are identifying a theory-practice gap whereby there is a disconnect between theoretical knowledge and CS practice experience, impacting specifically on newly qualified nurses and students within clinical placements (Abu Salah et al, Citation2018; Abu Salah & Salama, Citation2018; Saifan et al., Citation2021). Therefore, our pedagogic approach involved teaching the essential principles of a model of CS as well as promoting its use in clinical practice.

Within nursing practice, group CS benefits have been identified as enabling peer discussion, normalisation of experiences, being taken seriously by other group members, discussing practice issues and developing new ideas (Carver et al., Citation2014; McCarthy et al., Citation2021). With regards to the use of group CS involving mental health nursing students, a longitudinal study conducted in the UK concluded that whilst students found aspects of group CS helpful, a number of issues needed to be addressed by educators aiming to implement group CS initiatives. These included addressing the preparation of students, structural and resource concerns and any group dynamics considerations (Carver et al., Citation2014). Clibbens et al. (Citation2007) identified group CS can be chosen as a form of CS for mental health nursing students, because of its cost effectiveness and potential for a supportive atmosphere.

Methods

Research aim

The purpose of this research was to explore mental health nursing students’ experiences of online group CS to gain multi-layered accounts of student experience. It was aimed that outcomes of the inquiry would direct future directives in student nurse CS arrangements as an essential pedagogical approach. As stated, this study has been developed in recognition of a lack of established processes for student nurses to access CS within clinical placement areas. The group CS was developed to give the students the opportunity to reflect on their (placement) learning experiences, share their practice with other student nurses and give opportunity to improve the learning and understanding of professional issues and personal development. Our pedagogic approach involved teaching the essential principles of a model of CS (Proctor, Citation1986) which would be experienced in clinical practice as a registered mental health nurse. Shulman (Citation2005, p. 52) ascertained that signature pedagogies are implemented according to “…the types of teaching that organise the fundamental ways in which future practitioners are educated for their new professions suggesting that instruction is closely linked to the discipline taught.” The online group CS offered access to restorative support during the Covid-19 pandemic when face-to-face student contact in Higher Education had been ceased during periods of lockdown (Hubble & Bolton, Citation2020). The research was guided by the following questions:

What is the understanding and perceptions of the purpose of clinical restorative supervision?

What were the experiences of what was helpful or challenging about online group CS?

What was the learning around professional issues if this was established?

How can (online) group CS pedagogy and student participation be improved for student mental health nurses?

Study design

The study design involved using a qualitative methodology and method in the form of reflexive thematic analysis. Braun and Clarke’s framework for reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019) is a systematic method widely employed in qualitative research to identify, analyse, and report themes within a dataset. The framework for reflexive thematic analysis offered a robust and adaptable approach that empowered the researchers to prioritise the voices and perspectives of participants while maintaining methodological rigour. The process began with a deep dive into the data, aiming to familiarise ourselves with its content and context. Initial codes were generated to label significant segments, capturing essential ideas and patterns. Subsequently, these codes were scrutinised for identified themes, fostering a nuanced understanding of the dataset. Through careful review and refinement, themes were defined and named, each with a clear and distinctive identity. Narratives were then crafted, detailing and supporting each theme with illustrative examples, all while maintaining reflexivity and transparency. This design was identified as the best approach for the research, as analytic approaches which are orientated to describing, interpreting and finding patterns have been identified as a good fit for online focus group data (Fox & Braun, Citation2017). Additionally, the design met the interpretative reflexive focus of this research study which embraced qualitative research values and the subjective skills that the researchers brought to the process (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021a).

We considered how we would ensure Trustworthiness criteria in relation to our chosen form of thematic analysis—reflexive thematic analysis, had been considered and fulfilled. In relation to thematic analysis, Nowell et al. (Citation2017:3) state “…trustworthiness criteria are pragmatic choices for researchers concerned about the acceptability and usefulness of their research to a number of stakeholders.” Trustworthiness criteria were introduced by Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985) as credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability and will thus be outlined in how we strived towards meeting these criteria. The credibility measures put in place concerning the participant’s views and the researchers’ representation of them included persistent observation, triangulation between data collection (video-audio recordings and transcripts) and member checking of transcript accuracy. Researchers also had peer debriefing to discuss the research process throughout. To encourage transferability, thick descriptions of participants’ narratives were obtained and provided as quotes in the results section of this article, with the intention that anyone seeking to transfer findings to their own student population can consider its transferability factors. To meet the criteria of dependability we have provided an account of the research process and the specific application of reflexive thematic analysis. Through the reporting of the study we justify choices in research design, analysis and applied theory and have kept records of transcripts, field notes and reflexive diaries which provide an audit trail to the study. Aspects of these are presented in tabular form and in the results and discussion sections of this article. All of these aforementioned steps point to the confirmability of this research and how we established our interpretations and findings of the study.

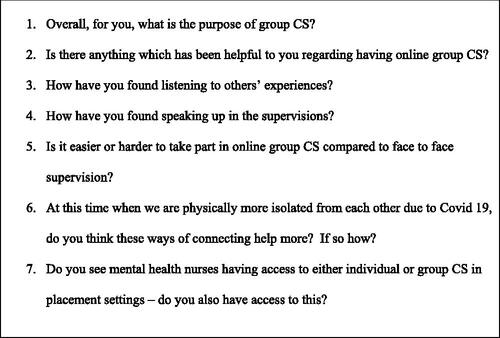

The process of the study involved offering mental health student nurses the opportunity to attend online group CS sessions lasting up to an hour via Microsoft Teams. These occurred at the end of the duration of the students’ clinical placements. Students could attend the supervision sessions without an obligation to participate in the research study (i.e. the focus groups). An overview of the structure and aims of the group supervision were given to the students via an information session. These were based on Proctor’s (Citation1986) model which is focussed on three stages; formative (professional development/education), restorative (emotional development/supportive) and normative (organisational responsibilities/competencies). The group CS sessions were delivered via separate year groups of year one students and year two students. Separate year one and two focus groups additionally occurred from supervision attendees. Focus groups have been identified as giving opportunity for unique insights for critical inquiry as a deliberate, dialogic, and democratic practice which is already engaged in real-world problems (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992 cited in Kamberelis & Dimitriadis, 2005). The focus groups lasted an hour’s duration and were also conducted over Microsoft Teams. We, as the two researchers facilitated both the group CS and the focus groups. One of us was a personal supervisor (tutor) for the identified students. This enabled a supportive strategy whereby the personal supervisor could follow up any emotional support required. The other researcher/facilitator could approach questioning from a more distanced position. A topic guide directed the areas of questioning (see ).

Participants

Online group CS sessions occurred before the focus groups were arranged. A purposive sample of participating students from the first and second year online CS groups in the Mental Health Nursing programme were invited to attend three focus groups. A sample of 13 students was obtained which culminated in 65% of the supervision group attendees. Representation occurred from all the supervision groups across the three focus groups (Group 1: n = 6, Group 2: n = 5, Group 3: n = 2). The BSc Mental Health Nursing programme is a three-year degree incorporating both academic and clinical placement modules. Successful completion enables graduates to register the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) nursing register in order to practise as a qualified registered mental health nurse in the UK.

Ethical approval via the Research Ethics Committee was granted by the researchers’ host institution (ID: FHS322). As well as focussing upon informed consent for possible participants, we also considered our researcher roles as “insider/participant researchers” and paid attention to how our personal supervisory and educator relationships may influence the communication occurring within the focus groups.

Data analysis

The online focus group meetings were transcribed using the integral transcription function within Microsoft Teams. These transcripts acted as primary sources of data in combination with the text produced in the “chat” function which had been used by some participants during the focus groups and the audio-visual recordings. The point was reached where no new information, insights and themes appeared to us from the collected data. The decision to conclude the analysis at the point was rooted in the recognition that the research goals had been met, ensuring that the study’s findings were grounded, exhaustive, and reflective of the depth and breadth of the data. Rather than adhering to conventions of data saturation depictions, we adhered to Braun and Clark’s (Citation2021b) research design and process regarding reflexive thematic analysis which encompasses searching for the meaning and meaningfulness through analysis within the dataset. Braun and Clarke (Citation2021b, p. 10) state:

…attempting to predict the point of data saturation cannot be straightforwardly tied to the number of interviews (or focus groups) in which the theme is evident, as the meaning and indeed meaningfulness of any theme derives from the dataset, and the interpretative process.

Adjunct to thematic analysis we used a poststructural lens “to seek the voice that escapes easy classification and that does not make easy sense. It is not a voice that is normative, but one that is transgressive” (Mazzei & Jackson, Citation2009, p. 4). Poststructuralism encourages the cocreation of self and social science and advises that knowing the self and subject are intertwined, inviting us to reflect on our method, thus opening us to new ways of knowing (Richardson & St. Pierre, Citation2005). Adding in a further layer by using theory in the rigorous analytic reading of the qualitative data, addresses complex areas which required further analysis. This involved “plugging in” specific concepts from theorists within the analysis of the data (e.g. power/knowledge, deconstruction, intra-activity) (Jackson & Mazzei, Citation2012). This enabled an opportunity to use philosophical concepts to further view the data through differing perspectives to examine the complexities of social life (Jackson & Mazzei, Citation2012); in this case, accounts of online group CS relating to placement experiences. The reflexive thematic analysis premise outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2019) involves recognising researcher subjectivity as a resource for telling “stories,” whilst interpreting and creating rather than attempting to find a final “truth.” This interlinks well with the poststructural underpinnings in this research which Richardson highlights as the need to understand ourselves reflexively as persons writing from particular positions at specific times, recognising there is no single truth (Richardson & St. Pierre, Citation2005). Applying these principles to our research study, we are aiming to examine and recognise our own understanding of ourselves in the roles of lecturers, CS facilitators and participant/insider researchers. As such, our method recognises our thinking and writing processes throughout the data analysis of this research project in making sense of lives and culture in theorising and producing knowledge (St. Pierre, Citation2015).

Results

The findings from the thematic analysis including participant quotes are illustrated in . In addition, key theoretical perspectives and concepts illustrate analytic inquiry to enable the plugging in of theory-into-data-into-theory, and a folding in of ourselves as researchers into the texts and theoretical thresholds (Jackson & Mazzei, Citation2012). To keep a focus on the overall inquiry of this research, the findings of the research are presented with each guiding research question resulting in identified themes, theoretical perspectives and researcher reflections:

Table 1. Thematic analysis and synthesis.

What is the understanding and perceptions of the purpose of clinical restorative supervision?

As researchers and focus group facilitators, we experienced and were part of student discussions on how online group CS can bring students together to produce and recognise Unifying Experiences. Some students expressed genuine surprise that some of their experiences whilst engaged in a clinical placement had also been experienced by other students. This was particularly pertinent to first year students. Students voiced this helped them feel more secure that it “wasn’t just them” who had felt a particular way, whether this be vulnerable or unsure in certain placement or clinical situations.

Group CS was perceived as particularly important to enable the expressions of feelings and experiences in a safe place, in addition there was an expression of responsibility whereby students were enthusiastic in using CS as a means and tool for learning, to reflect and consider how they could make improvements and deepen their considerations of events and situations they had been part of in their clinical placements.

I think it could be a point of reflecting on areas where you can improve on or that you lacked insight on. (1)

CS was perceived as An Accessible Way of Gaining Support with one participant commenting;

(in) smaller groups you get to know others, read people, you can say look I’m struggling here and get help. (1)

A minority of students talked about group CS as something else, showing A Misunderstanding of what CS is and to us as researchers, this showed a confusion in the varied teaching and placement structures which use the word “supervision” in their multiple processes to mean something other than CS. This highlighted the complexities and challenges to student understanding and was pertinent to a minority of first year students.

Even with the majority of students voicing an understanding of what CS entails, we paid attention to what was left out, looking at presence and absence and where language was strained (Jackson & Mazzei, Citation2012). What we noticed was that though accepted meanings of CS were being voiced, there was an absence of what the experience of engaging in CS felt like in participants’ accounts. It was therefore important for us as the researchers to employ a deconstructive approach to what was being missed in participants’ accounts here with regards to the gaps between CS voiced as important for the role of a mental health nurse—and the absence of CS expressed as an embodied experience. This was a trace element which haunted and echoed in the text and required recognition that there was learning and experience still to come (Derrida, Citation1997).

What were the experiences of what was helpful or challenging about online group supervision?

Being Visible and Not Visible centred around students’ discussions on face to face versus online presence within group CS. There were communications expressed in the discomfort of turning cameras on, difficulty in understanding online subtleties within communication and some expressed a face to face preference.

you can’t see people’s faces and expressions [online]…. (3)

(face to face) you can feel the support in the room. It’s different online. (1)

These factors continued in to the next theme; Carrying on the Conversation whereby continuing discussion focussed on experiences of remoteness of the online environment:

You feed off other people’s reactions and interactions better when it’s in-person than online. (1)

I don’t like the awkward silence online. (3)

(it is) a point of reflecting on areas where you can improve on or where you lacked insight. (2)

In addition, it was evident Being Valued as Part of the Group Supervision Process was both a beneficial experience and a means of connecting with others, even though online CS may be problematic to some:

you are not forgotten (1)

When someone steps up and breaks the ice, it’s a bit easier. (2)

What was the learning around professional issues if this was established?

The student as professional and assuming a professional identity was a prominent theme here, with especial reference to Trying to Live up to the “Good Student” Role. Students discussed some situations where they were striving to make a good impression and contribute meaningfully within their placement interactions, but found themselves negatively perceived through misunderstandings. Consequently, this caused stress and the students tried to understand the dynamics of how and why these situations had occurred, reflecting on the complexities of communication and team working.

My mentor expected so much from me…I didn’t know what was expected from me. (1)

Applying Foucault’s (Citation1980) view on the deployment of power and how the subject is affected via social relations and cultural practices, power relations with placement professionals influenced student subjectivities by inducing a chain of relations. This enabled processes that included feelings of repression which transgressed to a strengthening of some relationships or at the least widened discussion and understanding within the multi-disciplinary team environment. An example of this is when a student talked about borrowing a piece of equipment during their placement and then encountering misunderstanding regarding when they would return it. Because of Covid-19 working arrangements they had been told no one would be in the office until a particular date, so they delayed returning the equipment. A team member then chastised them for their late return of the equipment as they had wanted to borrow it themselves. The student explained they had felt blamed as though they had done something wrong and had behaved unprofessionally. Sharing this experience had enabled a sharing of subjectivity that had been constructed in relationships with others in everyday practices (Jackson & Mazzei, Citation2012), and had enabled a further process of “becoming,” leading to a more embodied empowered self. Placement Experiences and Linking this to Supervision further highlighted differing experiences and opportunities in the experience of CS. It appeared the majority of students had not had direct experiences of CS within their clinical placements, however all 13 participating students in this study gained experiences in online group CS.

No I’ve not seen any supervision being discussed within my placement area. (2)

How can (online) group CS pedagogy and student participation be improved for student mental health nurses?

From reviewing all data included within the identified themes of this research study, we conducted a themes synthesis in order to address this final question. The two main areas for improvement were identified as Improving Confidence and Trust in (Online) Participation and The Need for Familiarity in CS Participation and Understanding. There were differences in the engagement and perceptions of the online group CS process between the students that had participated in CS before and those that had not. This suggests that more needs to be done to prepare students about what CS entails from an educational perspective as well as support the embodied experiences of being a contributor in the group CS process (embracing both comfort and discomfort as features of CS). Supporting students to understand the importance of reflexive learning by experience throughout their nurse education and as a registered practitioner could support a growing appreciation of the value of CS as a careerlong vision.

Rogers (Citation1959) identified growth and acceptance when engaging in genuine relationships, with people sharing commonalities (comparable to student nurses in a group CS setting). To achieve this, we surmised it is essential that the facilitators were competent in facilitation rather than being in the “teacher role,” ensuring that CS was student focused and led through experiential learning.

Discussion

The findings from the thematic analysis demonstrate participants’ positive outlooks on the values of group CS in general, whilst also identifying the finer nuances of the differences and challenges in accessing this form of supervision through an online format. The thematic analysis particularly identified the ongoing developments and shifts in learning that students were experiencing, including what CS entails and how they can obtain access to it. The access issues involved consideration of engaging in CS in a clinical placement setting but also demonstrated the embodied experiences of accessing the group CS as part of this research study and how this group CS as a pedagogic approach enabled clinical placement experience discussion and gaining support from peers. Within discussions around the understanding and perceptions on the purpose of group CS, particular benefits of restorative components were identified including how it can support to unify experiences, provide an accessible way of gaining support and open up understandings of what CS is. These themes have also been reflected in registered mental health nurses’ experiences of what makes CS effective, especially with regards to positive experiences of CS and the continued engagement and ownership of CS (Buus et al., Citation2013; Gonge & Buus, Citation2011, Citation2015; Howard & Eddy-Imishue, Citation2020).

The challenges of the group CS as an online forum included enabling participation and open conversation. A study by McCutcheon et al. (Citation2018) found that a blended learning approach to the learning of supervision skills in pre-registration nurses scored higher in motivation, attitudes, satisfaction and knowledge compared to a purely online group. However, our study also highlighted the benefits of feeling valued as a result of participation in online group CS. Although this was a positive thematic outcome, being able to participate and voice opinions through the online group CS format raised several observations from us as the involved researchers. We found that when supervision participants had their cameras turned on they did openly communicate with verbal speech. When we as facilitators asked students why some would not turn their cameras on, they said they felt uncomfortable, though complained it was not helpful not being able to see facial expressions and body language as you would in a face-to-face supervision in a physical room. These appeared to be contradictory statements. As researchers, we found this frustrating but found ourselves reflecting on the meanings of what appeared to be contradictions, barriers to communication and repressed expression.

It means recognizing and confronting (or embracing) the inevitable ‘failings’ and falterings of voice - and exploring the ways in which voice is articulated – not only via clear verbal expressions – but also through silences, non-decipherable sounds, utterances, sighs, laughter, stutters, whispers, gestures, misunderstandings and refusals. (Chadwick, Citation2021, p. 80)

It was important here to not only recognise the critical role of transcription in our research interpretations (Chadwick, Citation2017) but incorporate our intent listening and observing of audio-visual recordings data and how we as researchers may have affected participant communication through our own emotional responses with regards to the dance between interviewees and ourselves (see Chadwick, Citation2018).

Silences were challenging because we did not know the possible personal or technological circumstances which may be influencing this. As facilitators we did experience many of the silences as “pregnant pauses.” By this we mean that there was a sense some students did have key contributions they wanted to voice, but something was holding them back:

…the silences are pregnant with what is to be said but cannot be said, just yet, of the ought-to-be-said, but that which is unutterable due to the possible repercussions, and the what-is-said, the meanings conveyed more loudly in silent speech. (Mazzei, Citation2007, p. 35)

This research has demonstrated the importance of not seeing online group CS sessions as ring-fenced static experiences of learning. During the research study, some students voiced supervision discussions were continued following the online group CS. This was a peer group initiative to continue developing the problem solving and peer support aspects of the discussion which had occurred in the formal group CS session. Peer group CS can involve spontaneous discussion that occurs through a dyad or in a group context (Golia & McGovern, Citation2015). Chabeli (Citation2001) ascertained that peer group supervision can be instrumental in group assessment and can support students’ appraisals of their learning which can be less threatening without tutor presence. A qualitative systematic review of peer assisted learning identified students form friendships and develop a sense of community whilst enabling shared understanding of being a student nurse within clinical environments (Carey et al., Citation2018). We concluded that both of these factors related to students’ autonomous actions to extend supervision discussions throughout this study. The themes we have identified have reflected our pedagogic approach whereby as lecturers we aimed to encourage students via their reflections, to make connections between theory and professional practice (Sheppard et al., Citation2018; Vereijken & van der Rijst, Citation2023). In addition, throughout the reflective discussion, we aimed to provide a process for student mental health nurses to produce discourses to support them in ways of thinking about their clinical experiences and to transform their particular knowledge domain (mental health nursing) (see Ashwin et al., Citation2014).

The synthesis of the identified themes have pointed towards key areas for development regarding improving student participation in group CS and our associated pedagogy. Improving confidence and Trust in (Online) Participation is important for increasing access for students to participate in group CS. These initial group CS sessions have provided a starting point for this form of CS and have raised an opportunity to further define and explore how to facilitate increased engagement. For group CS to become a familiar and non-threatening means of developing personal and professional development, there is a Need for Familiarity in Group CS Particiation and Understanding. Both of these areas point towards future directions for research.

Limitations

Although representation of the supervision groups were obtained within the focus groups, one group only contained two participants. We question whether this may have limited the opportunity for rich discussion from a greater variety of viewpoints, as focus groups emphasise the interactions between participants (Morgan, Citation1997) which could potentially enhance themes identification from the amount and quality of the data generated (Guest et al., Citation2017). However, the number of focus groups conducted for this study aligns with other research which has reported a sample size of two to three focus groups can identify at least 80% of themes on a topic—and furthermore, in a study with a homogenous population using a semistuctured guide, 90% of themes were identified within three to six focus groups (Guest et al., Citation2017). In addition we employ the concept of information power which aligns within the method of reflexive thematic analysis and indicates the more relevant information a sample holds—fewer particpants are needed (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021b).

Conclusion

This study adds to the current literature on using group CS within the student nurse population, in particular within the field of mental health nursing, and has identified a pedogogic approach towards closing the theory-practice gap. It aligns with other research in this sphere by highlighting the benefits of participation in group CS and echoes research which has signified that group CS is an effective means for student nurses to gain support and promote learning and peer support. Furthermore, by integrating a poststructural approach to analysis throughout this inquiry and valueing voice equally in what is said and what is not said; the silences and inhibitions surrounding online participation in particular, have additionally been identified. These areas have indicated that supplementary inquiry is needed for further development and research focussing upon inproving confidence, trust, understanding and familarity to improve enagagement. The findings of this study have further relevance in addressing pedagogic changes in online and digital pedogogy which have occurred since the pandemic, whereby both blended learning and purely online education delivery have continued, expanded and remained.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abu Salah, A., Aljerjawy, M., & Salama, A. (2018). The role of clinical instructor in bridging the gap between theory and practice in nursing education. The International Journal of Caring Sciences, 11(2), 876–882.

- Abu Salah, A. M. A., & Salama, A. (2018). Gap between theory and practice in the nursing education: The role of clinical setting. JOJ Nurse Health Care, 7(2), 55570. https://doi.org/10.19080/JOJNHC.2018.07.555707

- Ashwin, P., Abbas, A., & McLean, M. (2014). How do students’ accounts of sociology change over the course of their undergraduate degrees? Higher Education, 67(2), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9659-

- Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performitivity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(3), 801–831. https://doi.org/10.1086/345321

- Baumeister, R., & Leary, M. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociolgy. University of Chicago Press (cited in: Kamberelis, G., & Dimitriadis, G. (2005). Focus groups: Strategic articulations of pedagogy, politics, and inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 887–907). Sage Publications Ltd.)

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021a). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021b). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- Brunero, S., & Lamont, S. (2012). The process, logistics and challenges of implmenting clinical supervision in a generalist tertiary referral hospital. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 26(1), 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00913.x

- Butterworth, T., & Faugier, J. (1992). Clinical supervision and mentorship in nursing. Chapman & Hall.

- Buus, N., Cassedy, P., & Gonge, H. (2013). Developing a manual for stregthening mental health nurses’ clinical supervision. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34(5), 344–349. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2012.753648

- Carey, M., Kent, B., & Latour, J. (2018). Experiences of undergraduate nursing students in peer assisted learning in clinical practice: A qualitative systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 16(5), 1190–1219. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003295

- Carver, N., Clibbens, N., Ashmore, R., & Sheldon, J. (2014). Mental health pre-registration nursing students’ experiences of group clinical supervision: A UK longitudinal qualitative study. Nurse Education in Practice, 14(2), 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.08.018

- Chabeli, M. (2001). Alternative assessment and evaluation methods in clinical nursing education Monograph IV. Internal publication. Rand Afrikaans University.

- Chadwick, R. (2017). Embodied methodologies: Challenges, reflections and strategies. Qualitative Research, 17(1), 54–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794116656035

- Chadwick, R. (2018). Bodies that birth: Vitalizing birth politics. Routledge.

- Chadwick, R. (2021). Theorizing voice: Toward working otherwise with voices. Qualitative Research, 21(1), 76–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120917533

- Clibbens, N., Ashmore, R., & Carver, N. (2007). Group clinical supervision for mental health nursing students. British Journal of Nursing, 16(10), 594–598. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2007.16.10.23505

- Cummins, A. (2009). Clinical supervision: The way forward? A review of the literature. Nurse Education in Practice, 9(3), 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2008.10.009

- Derrida, J. (1997). Deconstruction in a nutshell: A conversation with Jacques Derrida. Fordham University Press.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings: 1972–1977 (L. Marshall, C. Gordon, J. Mepham, & K. Soper, Trans.; C. Gordon, Ed.). Pantheon Books.

- Fox, F., & Braun, V. (2017). Conducting online focus groups. In V. Clarke & D. Gray (Eds.), Collecting qualitative data: A practical guide to textual, media and virtual technologies. Cambridge University Press.

- Golia, G. M., & McGovern, A. R. (2015). If you save me, I’ll save you: The power of peer supervision in clinical training and professional development. British Journal of Social Work, 45(2), 634–650. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct138

- Gonge, H., & Buus, N. (2011). Model for investigating the benefits of clinical supervision in psychiatric nursing: A survey study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 20(2), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00717.x

- Gonge, H., & Buus, N. (2015). Is it possible to strengthen psychiatric nursing staff’s clinical supervision? RCT of a meta-supervision intervention. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(4), 909–921. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12569

- Guest, G., Namey, E., & McKenna, K. (2017). How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods, 29(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X16639015

- Health Education England (HEE). (2019). NHS staff and learners’ mental wellbeing commission, developing people for health and healthcare. Health Education England.

- Howard, V., & Eddy-Imishue, G.-E. (2020). Factors influencing adequate and effective clinical supervision for inpatient mental health nurses’ personal and professional development: An integrative review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 27(5), 640–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12604

- Hubble, S., & Bolton, P. (2020). BRIEFING PAPER number 8893 coronavirus: Implications for the higher and further education sectors in England. House of Commons Library.

- Jackson, A. Y., & Mazzei, L. A. (2012). Thinking with theory in qualitatitive research. Routledge.

- Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall.

- Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

- Masamha, R., Alfred, L., Harris, R., Bassett, S., Burden, S., & Gilmore, A. (2022). ‘Barriers to overcoming the barriers’: A scoping review exploring 30 years of clinical supervision literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(9), 2678–2692. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15283

- Mazzei, L. A. (2007). Inhabited silence in qualitative research: Putting poststructural theory to work. Peter Lang.

- Mazzei, L. A., & Jackson, A. Y. (2009). Introduction: The limit of voice. In A. Y. Jackson & L. A. Mazzei (Eds.), Voice in qualitative inquiry: Challenging conventional, interpretive, and critical conceptions in qualitative research (pp. 1–13). Routledge.

- Mc Carthy, V., Goodwin, J., Saab, M. M., Kilty, C., Meehan, E., Connaire, S., Buckley, C., Walsh, A., O’Mahony, J., & O’Donovan, A. (2021). Nurses and midwives’ experiences with peer-group clinical supervision intervention: A pilot study. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(8), 2523–2533. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13404

- McCutcheon, K., O’Halloran, P., & Lohan, M. (2018). Online learning versus blended learning of clinical supervisee skills with pre-registration nursing students: A randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 82, 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.02.005

- Morgan, D. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research. Sage Publications.

- NHS England. (2021). Professional nurse advocate. https://www.england.nhs.uk/nursingmidwifery/delivering-the-nhs-ltp/professional-nurse-advocate/

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. (2018). Realising professionalism: Standards for education and training Part 2: Standards for student supervision and assessment. Nursing and Midwifery Council.

- Proctor, B. (1986). Supervision: A cooperative exercise in accountability. In M. Marken & M. Payne (Eds.), Enabling and ensuring: Supervision in practice. National Youth Bureau Council for Education.

- Royal College of Nursing (RCN). (2003). Clinical supervision in the workplace: Guidelines for occupational health nurses. RCN.

- Richardson, L., & St. Pierre, E. A. (2005). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 959–978). Sage.

- Rogers, C. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality and interpersonal relationships as developed in the client-centered framework. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of a science. Vol. 3: Formulations of the person and the social context. McGraw Hill.

- Rothwell, C., Kehoe, A., Farook, S. F., & Illing, J. (2021). Enablers and barriers to effective clinical supervision in the workplace: A rapid evidence review. BMJ Open, 11(9), e052929. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052929

- Saifan, A., Devadas, B., Daradkeh, F., Abdel-Fattah, A., Aljabery, M., & Michael, M. (2021). Solutions to bridge the theory-practice gap in nursing education in the UAE: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 490. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02919-x

- Sheppard, F., Stacey, G., & Aubeeluck, A. (2018). The importance, impact and influence of group clinical supervision for graduate entry nursing students. Nurse Education in Practice, 28, 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2017.11.015

- Shulman, L. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1162/0011526054622015

- St. Pierre, E. A. (2015). Writing as method. In The Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosw029.pub2

- Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. In C. Willig (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 17–36). SAGE Publications.

- Vereijken, M., & van der Rijst, R. M. (2023). Subject matter pedagogy in university teaching: How lecturers use relations between theory and practice. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(4), 880–893. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1863352

- Victorian Government. (2018). Clinical supervision for mental health nurses. An integrative review of the literature. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Wallbank, S. (2013). Maintaining professional resilience through group restorative supervision. Community Practitioner, 86(8), 23–25.

- Wallbank, S., & Hatton, S. (2011). Reducing burnout and stress: The effectiveness of clinical supervision. Community Practitioner: The Journal of the Community Practitioners’ & Health Visitors’ Association, 84(7), 31–35.

- White, E., & Winstanley, J. (2010). Does clinical supervision lead to better patient outcomes in mental health nursing? Nursing Times, 106(16), 16–18.

- Yahya, A., & Sukmayadi, V. (2020). A review of cognitive dissonance theory and its relevance to current social issues. MIMBAR: Jurnal Sosial Dan Pembangunan, 36(2), 480–488.