?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

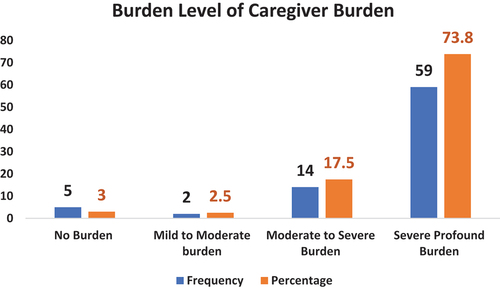

Dementia is a chronic disorder of the brain that affects cognitive performance. The caregivers of individuals with dementia experience a greater burden that affects their Quality of Life (QoL). This cross-sectional study conducted in India was designed to assess the caring burden and QoL among the caregivers of people with dementia, as well as to ascertain the relationship between QoL scores and burden. Our sample included 80 caregivers of people with dementia. Most of the caregivers (n = 59, 73.8%) had a higher level of caregiver burden. There was a negative correlation between caregiver burden scores and QoL. A higher level of caregiver stress and low QoL were experienced by caregivers of dementia patients. In developing countries like India, counseling, and education on home health care for people with dementia should be provided to reduce the burden and enhance the QoL of caregivers.

Introduction

A decline in a person’s cognitive ability, memory, or decision-making that interferes with a person’s day-to-day activities is collectively termed dementia. It refers to a range of conditions that cause abnormal changes in the brain rather than a single disease (Su et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; World Health Organization, Citation2023). Currently, dementia is the seventh most common cause of death among all diseases and a major contributor to disability and dependency among the older people as there are more than 55 million individuals with dementia, and every year, there are about 10 million new cases (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2023; World Health Organization, Citation2023).

The People Living with Dementia (PLWD) experience effects on their physical, psychological, social, and economic well-being along with family, society, and caregivers. Most older people with chronic illnesses are cared for by their close relatives (Duggleby et al., Citation2016). When an illness worsens, it necessitates a higher level of care, primarily provided by family members, which results in high medical costs, psychological stress, bad health, social isolation, and financial difficulty (Zacharopoulou, Zacharopoulou, & Lazakidou, Citation2015). Since they require thorough care depending on the stage of dementia, most of them will be looked after by their family or relatives (Brodaty & Donkin, Citation2009). It takes at least five hours a day for family caregivers to provide care for a person with dementia, which can be devastating emotionally, physically, and financially and cause stress in both families and carers (World Health Organization, Citation2023). Reduced execution of daily living tasks by the care recipients is a sign that the caregivers of PLWD are under more stress than before (Kim, Chang, Rose, & Kim, Citation2011). This leads to poor health of the caregivers’ and early institutionalization of PLWD (Etters, Goodall, & Harrison, Citation2008). Additionally, the caregiver burden is recognized to accompany it among those who provide care (Seidel & Thyrian, Citation2019).

The caregivers of PLWD bear a heavier strain than other caregivers (Chen et al., Citation2023; Hu et al., Citation2023; Lin et al., Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2022). Caregiver burden or stress is an unnoticeable, neglected and untreated or neglected health risk causing bad significance for both carers and individuals with dementia, comprising augmented illness and figures of mortality (Zwerling, Cohen, & Verghese, Citation2016). Most of them are older women who are also caretakers (Mondal, Tandon, & Dasgupta, Citation2021). The PLWD w are also impacted by this heavy burden of caregiving on the caretakers. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a greater caregiving load for informal caregivers of PLWD (Otobe et al., Citation2022).

The underlying cause of dementia affects the strain of providing care as well (Huang, Chang, Wang, & Jhang, Citation2022). As a result of caring for a person living with dementia, caregivers are more likely to cut back on their free time and interests, spend less time with their loved ones, and even quit their jobs. They frequently refrain themselves off from social interaction and as a result, feel lonely (Brodaty & Hadzi-Pavlovic, Citation1990). Caregiver health issues are frequently associated with a significant risk of developing weakened immunity, cardiovascular issues, and chronic diseases including diabetes, hypertension, anemia, arthritis, etc (Brodaty & Donkin, Citation2009).

Females were shown to have the highest association with caregiver load (Chiari et al., Citation2021). Giving care to a family member who has dementia is linked to higher caregiving load, depression, and finally poor QoL for the caregiver. There is a strong negative correlation between higher burden in caregiving and lower QoL of PLWD caregivers (Karg, Graessel, Randzio, & Pendergrass, Citation2018; Romero-Mas, Ramon-Aribau, de Souza, Cox, & Gómez-Zúñiga, Citation2021). One of the most important factors is the carers’ QoL because they care for family members who have dementia and informal caregivers of PLWD have low health-related QoL (Garzón-Maldonado et al., Citation2017; Hazzan et al., Citation2022). Caregiving is strongly connected with negative effects on the caregivers’ QoL, which is negatively impacted by depressed symptoms. This effect is most frequently noticed when the condition is advanced when the caregiver must provide a great deal of care by closely monitoring the patient, spending a great deal of money on the PLWD medical bills, and is also impacted by the caregiver’s chronic sickness (Andreakou, Papadopoulos, Panagiotakos, & Niakas, Citation2016).

Poor QoL arises from caring for a loved one who has dementia. Female caregivers, older caregivers, and caregivers with the presence of any sort of medical conditions or co-morbidities are additional risk factors for poor QoL of the caregivers (Andreakou, Papadopoulos, Panagiotakos, & Niakas, Citation2016). When compared with younger informal carers, older PLWD caregivers had a lower QoL (Conrad, Alltag, Matschinger, Kilian, & Riedel-Heller, Citation2018). This may be caused by concerns about the future, the progression of the disease, the stress and illness of the patient, and it may be influenced by several factors affecting both the carers and care recipients (Vellone, Piras, Talucci, & Cohen, Citation2008; Vun, Cheah, & Helmy, Citation2020). This paper discusses the baseline findings of an interventional study directed at caregivers of PLWD focusing on the caregiver and their QOL.

Objectives

The objectives of the study were: (i) to assess the caring burden and QoL among those who provide care for PLWD, (ii) to find the correlation between the caregiver burden and the QoL among the caregivers of PLWD, (iii) and to find the association between caregiver burden and the baseline demographic variables among the caregivers of PLWD.

Participants and methods

To determine the caregiver burden and QoL among carers of PLWD, a descriptive cross-sectional study design was used. The Head of the Institution, Medical Superintendent, Medical Director, and Administrative Officer of the chosen institutions provided administrative permits for the study’s execution, and the caregivers provided written informed consent. The ethics committee gave their approval (IEC 776/2019) to the study protocol, which is also listed with the Clinical Trial Registry of India CTRI/2020/02/023362.

The sample size was determined at a 5% level of significance with suitable adjustments to facilitate multiple comparisons, 80% power and an anticipated correlation of 0.4, the minimum sample size required for the study to explore the relationship between the caregiver burden and QoL among caregivers of PLWD is 71.

The researcher developed a baseline demographic questionnaire. It included information about the age, gender of the caregiver, their relationship to the patient, and the duration of care they had given. The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) − 22, a 22-item Likert scale scoring from 0 to 4 with 0 Never, 1-rarely, 2-sometimes, 3-quite regularly, and 4-Near always, was used to quantify the burden of the caregiver. The ZBI-22 is further separated into two domains: role strain (2, 3, 6, 11–13) and personal strain (1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 14, 16–21). No domain included items 7, 10, 15, and 22. Greater caregiving stress in the study is indicated by higher scores. They were divided into four levels based on the participant’s score. The scores between 0 and 21 were categorized as little or no burden, 22 to 40 as mild to moderate burden, 41 to 60 as moderate to severe burden, and 61 to 88 as severe profound burden. It has a good reliability with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 For ZBI-22, there is one additional category for total scoring. Scores of 0 to 21 indicate no burden, while 22 to 80 indicate the presence of a burden (Lin, Ku, & Pakpour, Citation2017; Tripathi, Srivastava, Tiwari, Singh, & Tripathi, Citation2016).

The standard World Health Organisation Quality of Life Brief Version (WHOQOL BREF) questionnaire, which has 26 items, was used to measure the overall QoL. It has four domains namely the physical health domain, psychological health, social relationships, and environmental domain. This tool has a good test-retest reliability of 0.66–0.84 for each of the four domains (Lin et al., Citation2019; Lin, Li, Lin, & Chen, Citation2016; Tripathi, Srivastava, Tiwari, Singh, & Tripathi, Citation2016). Both tools were offered in English and the regional language Kannada. The necessary authorities granted permission for the usage of the tools in both the local Kannada language and English. Permission to use ZBI-22 was obtained online from MAPI trust and permission to use the WHOQOLBREF scale was obtained from the WHO site. The ZBI and WHOQOL-BREF were extensively utilized in studies on caregivers of dementia patients to evaluate their burden and QoL. As a result, the researcher decided to use the same scales. Both Kannada and English versions of the data collecting tools were given, based on the interests of the study participants.

The formal and informal caregivers between the ages of 18 and 70 who understood Kannada or English were recruited from selected hospitals in the Udupi District. Before recruiting the study participants, administrative approval was sought from the medical superintendent, department heads, and administrative officials. The institutional research committee and institutional ethics committee gave their approval to the project.

The caregivers were selected from the designated hospitals since most of them visit the psychiatric OPD for follow-up and consultation with their relatives suffering from dementia. After screening the caregivers to meet the inclusion criteria, the Principal Investigator explained the study procedure to the caregivers and obtained the informed consent. Before being enrolled in the study, participants were given a Participant Information Sheet with comprehensive information about the investigation. Details about the study, including its title, goals, lead investigator’s name, length of the trial, questionnaires utilized potential hazards and benefits, etc., were included on this participant information sheet. The study’s subjects were only chosen after providing written consent. The study’s participants’ privacy and confidentiality were always maintained.

Data analysis

To establish the baseline demographics of the caregivers of dementia patients, descriptive statistics using frequency tables and percentages were used. Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed to determine the correlation between the ZBI and QoL scores. The Chi-square test was performed to investigate the association between baseline demographic factors and caregiver burden. Jamovi (2.3.24), a graphical user interface for R programming and Microsoft Excel were used to conduct the statistical analysis.

Results

Eighty caregivers out of 110 met the requirements for inclusion. There was only one male caregiver out of the total participants recruited. The average age of the caregivers was 46 ± 12.7. Most of the carers (n = 44, 55%) were homemakers (n = 66, 82.5%), provided care for 2–4 hours each day (n = 48, 60%), and lived in rural areas (n = 53, 66.3%). (). Daughters-in-law were the majority (n = 46, 57.5) in terms of relationship to the care recipient whereas there were few other caregivers (Son −1, Cousin 1, Neice-1, Home nurse-1)

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of caregivers of PLWD n = 80.

The majority of PLWD were females (n = 48, 60%), over 70 years old (n = 57, 71.3%), were in-laws (n = 46, 57.5%) to the caregivers, were suffering from Alzheimer’s disease (n = 39, 48.8%), were chronic alcoholics (n = 16, 20%), chronic smokers (n = 14, 17.5%), and tobacco chewers (smokeless tobacco users) (n = 5, 6.3%). ().

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of PLWD. n = 80.

describes the ZBI and QoL scores split down by domain. While the mean QoL score was 45.9 ± 13.9, and the mean ZBI score was 63.40 ± 16.99 (). Most of the carers (n = 59, 73.8%) reported feeling extremely burdened when caring for the dementia patient (). We discovered a negative correlation (r = −0.370, p < .05) between caregiver burden and QoL ratings.

Table 3. Domain wise caregiver burden scores and quality of life sores of the caregivers of PLWD. n = 80.

Based on the Mann-Whitney U test at a 5% level of significance, we conclude that there is a statistically significant difference in the QoL scores across two levels of hours of care, caregiver burden and two levels of education. A similar phenomenon is also observed in the context of the presence of chronic illness among caregivers as depicted in .

Table 4. Role of socio-demographic variables on caregiver burden and quality of life of caregivers n = 80.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the QoL and caregiver burden among PLWD caregivers. Out of 80 samples, there was just one male caregiver in the study. Because men locally who are relatives of PLWD go to work to provide for their families and because their wives, daughters, or daughters-in-law typically take care of their parents, it was not possible to recruit a significant number of male carers for this study. Most of the time, a person’s daughter-in-law, wife, or daughter took care of them. The study is contradicted by a Taiwanese study that reported that poor activities of daily living and being a son were associated with a greater level of burden among caregivers (Tsai et al., Citation2022).

It is noteworthy that daughters-in-law made up the majority of (n = 46, 57%) carers for PLWD. This could be a result of Indian tradition, which generally involves parents residing with their offspring, particularly their son and daughter-in-law. Men often provide for their families through work, therefore the wife, who is typically the daughter-in-law of the individual living with dementia, will be responsible for the family and other domestic duties. As a result, daughters-in-law assume the role of their in-laws’ informal caregivers as they get older because most males work to support the family. However, due to changes in the family system, there are some situations where the wife or daughter will provide care (Herat-Gunaratne et al., Citation2019).

Most (n = 66, 82.5%) of the caregivers were homemakers, and two caregivers were working in the private sector where one was a paid caregiver, and the other one was the son who was living and taking care of his mother and the only breadwinner in the family. Along with caring for their loved one with dementia, a small number of caregivers (n = 12, 15%) owned businesses that included agriculture, tailoring, and horticulture such as cultivating jasmine flowers, areca nut cultivation, and cultivating coconut plantations where they could add income for their family expenses.

In the current study, the majority (73.8%) of the caregivers experienced severe profound burden, while 17.5% experienced moderate to severe burden. This finding is supported by few studies (Liu, Heffernan, & Tan, Citation2020; Settineri, Rizzo, Liotta, & Mento, Citation2014; Tsai et al., Citation2021; Tulek et al., Citation2020; Zarit, Reever, & Bach-Peterson, Citation1980). Duration of caring could be one factor leading to burden as the majority (n = 48, 60%) of the caregivers spent at least 2–4 hours per day in the patient’s activities such as giving a bath, giving back massage, taking the patient for a walk, feeding, etc whereas few (n = 32, 40%) of the caregivers spent only up to 2 hours in patient the activities. This study discovered a negative correlation between the WHOQOL-BREF scores and ZBI scores, indicating that as the burden increases, there is a decline in the QOL. The results are corroborated by a prior study done in India that evaluated the caregiver burden and QoL among PLWD carers that and discovered a negative relationship between the Zarit Burden ratings and QoL (Tripathi, Srivastava, Tiwari, Singh, & Tripathi, Citation2016).

In the current study, the majority (n = 59, 73.8%) of the caregivers experienced severe profound burden, while few (n = 14, 17.5%) caregivers experienced moderate to severe burden. These findings are supported by a few studies published earlier where caregivers of PLWD experienced a severe burden (Liu, Heffernan, & Tan, Citation2020; Settineri, Rizzo, Liotta, & Mento, Citation2014; Tsai et al., Citation2021, Citation2022; Tulek et al., Citation2020; Zarit, Reever, & Bach-Peterson, Citation1980). Duration of caring could be one factor leading to burden as majority (n = 48, 60%) of the caregivers spent at least 2–4 hours per day in patient’s activities such as giving a bath, giving back massage, taking the patient for a walk, feeding, etc whereas few (n = 32, 40%) of the caregivers spent only up to 2 hours in patient activities. This is also supported by a study done in Spain which reported a negative correlation between the duration of caring and QoL (Romero-Mas, Ramon-Aribau, de Souza, Cox, & Gómez-Zúñiga, Citation2021).

This study discovered a negative correlation between the WHOQOL-BREF scores and ZBI scores (r = −0.370, p < .05), indicating that as the burden increases, the QoL decreases. The results are corroborated by a prior study that evaluated the caregiver burden and QoL among PLWD carers in India and discovered a negative relationship between the Zarit Burden ratings and QoL (Tripathi, Srivastava, Tiwari, Singh, & Tripathi, Citation2016).

We found a significant association between the caregivers’ QoL, and the hours of care given per day to the PLWD. This finding is also supported by a Spanish study that reported a negative correlation between the duration of caring and QoL.

Limitations

Due to the smaller sample size of caregivers of PLWD, the results of this current descriptive cross-sectional study cannot be directly applied to represent a larger population of caregivers of PLWD compared to the previous research studies.

Most of the caregivers in this study were females. Females and males may have different levels of QOL and psychological health. Therefore, the findings could not be generalized to male participants.

Future implications

According to the results of this descriptive cross-sectional survey, caring for a person with dementia can be strenuous. The socio-demographic profile and psychological characteristics of the carer are the key contributors to the burden of caring. Appropriate interventions such as home health care education, awareness camps, self-help groups, and community help groups are recommended to decrease the burden and improve QoL. Research studies with a bigger sample size could be conducted by healthcare professionals, especially nurses, doctors, and counselors for early detection of caregiving stress that could prevent future indications of depression or mental instability among caregivers to reduce caregiver burden and improve the QoL.

Conclusion

The study results reveal a higher caregiving burden and low QoL among caregivers of PLWD. These findings are an eye-opener as they strongly suggest implementing measures to reduce caregiver burden to enhance the QoL of the caregivers of PLWD. The healthcare providers must periodically evaluate the caregiver burden among those who care for PLWD to provide interventions such as education on home health care of PLWD, stress reduction interventions, awareness programs, and self-help groups, that can lessen the burden and improve the QoL.

Abbreviations

| QOL | = | Quality of life |

| PLWD | = | People living with dementia |

| ZBI | = | Zarit Burden Interview |

| OPD | = | Outpatient departments |

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andreakou, M. I., Papadopoulos, A. A., Panagiotakos, D. B., & Niakas, D. (2016). Assessment of health-related quality of life for caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients. International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2016, 1–7. doi:10.1155/2016/9213968

- Brodaty, H., & Donkin, M. (2009). Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(2), 217–228. National Library of Medicine. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/hbrodaty

- Brodaty, H., & Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. (1990). Psychosocial effects on carers of living with persons with dementia. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 24(3), 351–361. doi:10.3109/00048679009077702

- CDC. (2023, September 20). CDC’s Alzheimer’s disease and healthy aging program. Centers for disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/index.html#:~:text=Alzheimer

- Chen, Y.-J., Su, J.-A., Chen, J.-S., Liu, C., Griffiths, M. D. … Lin, C.-Y. (2023). Examining the association between neuropsychiatric symptoms among people with dementia and caregiver mental health: Are caregiver burden and affiliate stigma mediators? BMC Geriatrics, 23(1). doi:10.1186/s12877-023-03735-2

- Chiari, A., Pistoresi, B., Galli, C., Tondelli, M., Vinceti, G. … Zamboni, G. (2021). Determinants of Caregiver Burden in Early-Onset Dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra, 11(2), 189–197. doi:10.1159/000516585

- Conrad, I., Alltag, S., Matschinger, H., Kilian, R., & Riedel-Heller, S. G. (2018). Quality of life among older informal caregivers of people with dementia. Der Nervenarzt, 89(5), 500–508. doi:10.1007/s00115-018-0510-8

- Duggleby, W., Williams, A., Ghosh, S., Moquin, H., Ploeg, J., Markle-Reid, M., & Peacock, S. (2016). Factors influencing changes in health related quality of life of caregivers of persons with multiple chronic conditions. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 14(1). doi:10.1186/s12955-016-0486-7

- Etters, L., Goodall, D., & Harrison, B. E. (2008). Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: A review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20(8), 423–428. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00342.x

- Garzón-Maldonado, F. J., Gutiérrez-Bedmar, M., García-Casares, N., Pérez-Errázquin, F., Gallardo-Tur, A., & Torres, M. M. V. (2017). Health-related quality of life in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurología (English Edition), 32(8), 508–515. doi:10.1016/j.nrleng.2016.02.011

- Hazzan, A. A., Dauenhauer, J., Follansbee, P., Hazzan, J. O., Allen, K., & Omobepade, I. (2022). Family caregiver quality of life and the care provided to older people living with dementia: Qualitative analyses of caregiver interviews. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1). doi:10.1186/s12877-022-02787-0

- Herat-Gunaratne, R., Cooper, C., Mukadam, N., Rapaport, P., Leverton, M. … Bowers, B. J. (2019). “In the Bengali vocabulary, there is no such word as care home”: Caring experiences of UK Bangladeshi and Indian family carers of people living with dementia at home. The Gerontologist, 60(2). doi:10.1093/geront/gnz120

- Hu, Y. L., Chang, C. C., Lee, C. H., Liu, C. H., Chen, Y. J., Su, J. A., … Griffiths, M. D. (2023). Associations between affiliate stigma and quality of life among caregivers of individuals with dementia: Mediated roles of caregiving burden and psychological distress. Asian Journal of Social Health and Behavior, 6(2), 64.

- Huang, W. C., Chang, M. C., Wang, W. F., & Jhang, K. M. (2022). A comparison of caregiver burden for different types of dementia: An 18-month retrospective cohort study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 798315. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.798315

- Karg, N., Graessel, E., Randzio, O., & Pendergrass, A. (2018). Dementia as a predictor of care-related quality of life in informal caregivers: A cross-sectional study to investigate differences in health-related outcomes between dementia and non-dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1). doi:10.1186/s12877-018-0885-1

- Kim, H., Chang, M., Rose, K., & Kim, S. (2011). Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of individuals with dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(4), 846–855. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05787.x

- Lin, C. Y., Hwang, J. S., Wang, W. C., Lai, W.-W., Su, W. C. … Wang, J.-D. (2019). Psychometric evaluation of the WHOQOL-BREF, Taiwan version, across five kinds of Taiwanese cancer survivors: Rasch analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 118(1), 215–222. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2018.03.018

- Lin, C.-Y., Ku, L.-J. E., & Pakpour, A. H. (2017). Measurement invariance across educational levels and gender in 12-item Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) on caregivers of people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(11), 1841–1848. doi:10.1017/s1041610217001417

- Lin, C.-Y., Li, Y.-P., Lin, S.-I., & Chen, C.-H. (2016). Measurement equivalence across gender and education in the WHOQOL-BREF for community-dwelling elderly Taiwanese. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(8), 1375–1382. doi:10.1017/s1041610216000594

- Lin, C.-Y., Shih, P.-Y., & Ku, L.-J. E. (2019). Activities of daily living function and neuropsychiatric symptoms of people with dementia and caregiver burden: The mediating role of caregiving hours. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 81, 25–30. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2018.11.009

- Liu, Z., Heffernan, C., & Tan, J. (2020). Caregiver burden: A concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 7(4), 438–445. doi:10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.07.012

- Liu, Z., Sun, W., Chen, H., Zhuang, J., Wu, B. … Yin, Y. (2022). Caregiver burden and its associated factors among family caregivers of persons with dementia in Shanghai, China: A cross-sectional study. British Medical Journal Open, 12(5), e057817. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057817

- Mondal, S., Tandon, R., & Dasgupta, J. (2021). An exploratory study of caregiver burden amongst urban upper class adults in India during COVID‐19. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 17(S7). doi:10.1002/alz.052800

- Otobe, Y., Kimura, Y., Suzuki, M., Koyama, S., Kojima, I., & Yamada, M. (2022). Factors associated with increased caregiver burden of informal caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 26(2), 157–160. doi:10.1007/s12603-022-1730-y

- Romero-Mas, M., Ramon-Aribau, A., de Souza, D. L. B., Cox, A. M., & Gómez-Zúñiga, B. (2021). Improving the quality of life of family caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease through virtual communities of practice: A quasiexperimental study. International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2021, 1–10. doi:10.1155/2021/8817491

- Seidel, D., & Thyrian, J. R. (2019). Burden of caring for people with dementia – comparing family caregivers and professional caregivers. A descriptive study. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 12, 655–663. doi:10.2147/jmdh.s209106

- Settineri, S., Rizzo, A., Liotta, M., & Mento, C. (2014). Caregiver’s burden and quality of life: Caring for physical and mental illness. International Journal of Psychological Research, 7(1), 30–39. doi:10.21500/20112084.665

- Su, J.-A., Chang, C.-C., Wang, H.-M., Chen, K.-J., Yang, Y.-H., & Lin, C.-Y. (2019). Antidepressant treatment and mortality risk in patients with dementia and depression: A nationwide population cohort study in Taiwan. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease, 10, 204062231985371. doi:10.1177/2040622319853719

- Su, J.-A., Chang, C.-C., Yang, Y.-H., Chen, K.-J., Li, Y.-P., & Lin, C.-Y. (2020). Risk of incident dementia in late-life depression treated with antidepressants: A nationwide population cohort study. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 34(10), 1134–1142. doi:10.1177/0269881120944152

- Tripathi, R., Srivastava, G., Tiwari, S., Singh, B., & Tripathi, S. (2016). Caregiver burden and quality of life of key caregivers of patients with dementia. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(2), 133. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.178779

- Tsai, C.-F., Huang, M.-H., Lee, J.-J., Jhang, K.-M., Huang, L.-C. … Fuh, J.-L. (2022). Factors associated with burden among male caregivers for people with dementia. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association, 85(4), 462–468. doi:10.1097/jcma.0000000000000704

- Tsai, C.-F., Hwang, W.-S., Lee, J.-J., Wang, W.-F., Huang, L.-C. … Fuh, J.-L. (2021). Predictors of caregiver burden in aged caregivers of demented older patients. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1). doi:10.1186/s12877-021-02007-1

- Tulek, Z., Baykal, D., Erturk, S., Bilgic, B., Hanagasi, H., & Gurvit, I. H. (2020). Caregiver burden, quality of life and related factors in family caregivers of dementia patients in Turkey. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(8), 741–749. doi:10.1080/01612840.2019.1705945

- Vellone, E., Piras, G., Talucci, C., & Cohen, M. Z. (2008). Quality of life for caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 61(2), 222–231. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04494.x

- Vun, I. J., Cheah, W. L., & Helmy, H. (2020). Quality of life and its associated factors among caregivers of patients with dementia–A crosssectional study in Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia. Neurology Asia, 25(2), 165–172.

- World Health Organization. (2023, March 15). Dementia. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- Zacharopoulou, G., Zacharopoulou, V., & Lazakidou, A. (2015). Quality of life for caregivers of elderly patients with dementia and measurement tools: A review. International Journal of Health Research and Innovation, 3(1), 2051–5065. https://www.scienpress.com/Upload/IJHRI/Vol%203_1_4.pdf

- Zarit, S. H., Reever, K. E., & Bach-Peterson, J. (1980). Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist, 20(6), 649–655. doi:10.1093/geront/20.6.649

- Zwerling, J., Cohen, J. A., & Verghese, J. (2016). Dementia and caregiver stress. Neurodegenerative Disease Management, 6(2), 69–72. doi:10.2217/nmt-2015-0007