Abstract

Ontologies such as CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CRM) aim to provide support for reuse, interoperability and advanced search in data through implementation of semantically rich data models. Such models, however, tend to produce complex data with a granularity that can be far from how end users conceptualize a domain. This study, using a qualitative field-research method and a naturalistic approach, aims to explore the information needs of users and how this aligns with CIDOC CRM entities. Main result is a set of ontology patterns describing a range of information needs. Such patterns can guide the implementation of ontology-based information systems.

Introduction

With the innovation of the Semantic Web and the growing demand for reuse and access to data in a global context, ontologies such as the CIDOC Conceptual Reference ModelCitation1 (CRM) provide a platform for integration of heterogeneous datasets through formally describing the implicit and explicit concepts and relationships used in cultural heritage documentation. A common framework for describing entities and their properties provides semantic glue between different datasets and therefore can help researchers explore more complex questions.

CIDOC CRM is the outcome of over 20 years of development and maintenance work. The CRM base standard provides the basic set of classes and properties and is complemented by modular extensions to support specialized documentation needs. CIDOC CRM is intended to be a common language between domain experts and implementors in the development of documentation standards and information systems with a focus on integrity and interoperability. However, elaborated ontologies are not easily understood by end users of information systems as the complex structures and level of details can be far from users’ perspectives. Therefore, there is always a need for a layer of transformation between the actual data and the users’ perspectives and their actual needs and questions. To contribute to such a transformation layer, we need a more profound understanding of what users are looking for when they search these information systems. Studying information needs has a long history and has been approached using various methods. However, the analysis of information needs in the context of ontologies has received less attention. Conducting empirical research in this area is crucial to comprehend and describe the alignment of user’s mental models to the models expressed in ontologies.

This study, designed with an exploratory framework, is intended to investigate the specific information that PhD-candidates seek during their information searches related to their own projects and examine how their information needs can be mapped to the semantic structures found in ontologies like CIDOC CRM. The study was conducted as part of a PhD research project at OsloMet University in Norway during the period 2013–2017. Our primary objective in this paper is to enhance the practicality of ontologies such as CIDOC CRM within cultural heritage information systems. We aim to identify shared characteristics and patterns in users’ information needs through ontological analysis.

Background

The exploration of cognitive processes in the realm of information retrieval traces its origins back to the 1960s, specifically in the early contributions of TaylorCitation2 as well as Paisley and Parker.Citation3 During this time, these pioneers recognized the significance of comprehending users’ knowledge frameworks and the dynamics of their interactions throughout the information retrieval process. Edwin Parker and William Paisley, as highlighted by Ruthven and Kelly,Citation4 made significant advancements by adopting an interdisciplinary approach that integrated psychology, communication, and information science into the study of user-centered information retrieval.

Within the framework of the user-centered approach, information is subjective, context-dependent, comprehensive, and intertwined with cognitive processes. This viewpoint underscores the need to comprehend information within specific contextual settings.Citation5 According to Dervin,Citation6 the concept of information is not a static entity with a fixed meaning that universally describes reality or can be effortlessly conveyed from information producer to receiver through conventional channels. Rather, information is a construct that is actively shaped through the cognitive process of sense making. Additionally, KellyCitation7 introduced the Personal Construct Theory, suggesting that people develop personal constructs when facing new situations to create meaning to their surroundings. Every person’s perception of the world comprises a fusion of diverse knowledge structures.Citation8

In the user-centered approach, comprehending information is intricately tied to the user’s knowledge structures within specific temporal and spatial contexts. Individuals interpret the same events in their distinct manners; thus, it is necessary to understand human behavior within a relevant context.Citation9 The primary aim of the cognitive approach is to explore how people’s knowledge structures interact with the information they have access to. This involves studying how these knowledge frameworks impact information selection, influence the perception of relevance, and even how the acquired information has the potential to reshape and alter these knowledge structures.Citation10

A main field of research related to users’ cognitions in the information retrieval process is the concept of information needs. An information need arises when the individual identifies gaps in their understanding. This recognized anomaly in their knowledge structure as termed by BelkinCitation11 as the Anomalous State of Knowledge (ASK), often revolves around a particular topic or situation, yet they may struggle to precisely articulate what’s required to resolve it.Citation12 BorlundCitation13 highlights that the cognitive perspective recognizes the user’s personal perception of their information needs, leading to subjective evaluations of information relevance. This perspective also emphasizes the significance of the surrounding context in shaping the user’s situation and information requirements.

Within the context of seeking information, SaracevicCitation14 introduces a stratified model that comprises three levels: cognitive (pertaining to knowledge structures), affective (encompassing intent, beliefs, motivation, emotions, and desires), and situational (centered around tasks) on the user’s side. Broadly, the cognitive and user-centered approach centers on understanding the genuine thoughts, actions, and emotions individuals experience when engaged in information search activitiesCitation15 within specific circumstances. IngwersenCitation16 categorizes information needs into three distinct types. First, the verificative information need (VIN) pertains to instances where the user aims to validate or locate particular items. Second, the conscious topical information need (CIN) relates to scenarios where the user seeks clarification, review, or further exploration of aspects within a familiar subject. Lastly, the muddled topical information need (MIN) encompasses situations in which the user desires to delve into new concepts or relationships beyond their established subject matter.

In another study, Ingwersen and JärvelinCitation17 introduce a division of needs into two primary groups: specific and exploratory. Under specific needs, they encompass the search for known items, known data elements, known topics or content, and factual data. In contrast, exploratory needs encompass muddled items, muddled data elements, muddled topics or content, and muddled factual data.

T. D. WilsonCitation18 contends that within each instance of seeking information, there exist fundamental task-related objectives to be fulfilled. A task, as characterized by Toms,Citation19 encompasses a clear objective or purpose, with an anticipated yet potentially uncertain outcome. In general, tasks can exhibit varying levels of complexity. Complexity, from an objective standpoint, can arise due to the presence of task layers, which comprise progressively smaller sub-tasks constituting the larger task. TomsCitation20 suggests an inherent hierarchy within tasks, wherein each sub-task possesses its distinct objectives, conditions, activities, actions, and outcomes that are separate from the primary task, yet essential for the advancement and completion of the main task. Given that, a research project can be considered a complex task with multiple potential paths to a goal that leads to several information needs.

CIDOC conceptual reference model (CRM)

In the last decades, ontologies and conceptual reference models have gained wide acceptance as fundament for developing documentation standards and information systems in many domains – including cultural heritage and digital humanities. A seminal definition of what an ontology implies, in the context of engineering, is given by Gruber who defined ontology as “an explicit specification of a conceptualization.”Citation21 This definition is later elaborated upon by others, including AgarwalCitation22 who defines an ontology as a representation of a shared domain understanding that facilitates meaningful communication, consequently bolstering information system interoperability. The constructs in ontologies not only characterize the real world but also explicitly represent domain semantics, enabling their application across heterogeneously structured databases with similar semanticsCitation23 and promoting the reusability of domain knowledge. Pragmatically, a common ontology defines the vocabulary for exchange of information and formulating queries.

The CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CRM) serves as an extensive ontology, providing a solution to the intricate task of coherent integration of heterogeneous cultural-heritage data spanning archives, libraries, and museums. The engineering of ontologies inherently requires some formalisms for the specifications, and CIDOC CRM is based on the formalisms of object-oriented modeling using classes and properties. Classes represent the kinds of abstract or concrete entities (things) we describe, and properties describe the characteristics of the things and the relationships between things. Both classes and properties in CIDOC CRM are organized in inheritance hierarchies to express narrower and broader meanings of each. The classes in the base CRM are formally identified using number prefixed with the capital letter E, and properties are identified accordingly using the capital letter P. In addition, all classes and properties have human understandable labels which are commonly used when referencing a specific class or property. CIDOC CRM is an event-centric ontology which implies a focus on human activities and the documentation of how things and events happened in space and time. Given this focus, the Temporal Entity (E2) emerges as a pivotal concept within the model. The Temporal Entity is embedded within a defined Time Span (E52) and is situated at a specific Place (E53), ultimately leading to a transformation in the world’s state.Citation24 Certain Actors (E39) play a role in this Temporal Entity, exerting an influence on or being connected to Conceptual Objects (E28) or Physical Things (E18). Ultimately, for the purpose of classification, the CRM employs the notion of Types (E55) to categorize various elements. CIDOC CRM, functioning as a comprehensive framework, incorporates several extensions tailored to specific domains or applications such as FRBRooCitation25 (Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records) and its successor LRMoo,Citation26 CRMinf (argumentation model), CRMarchaeo (excavation model), CRMsci (scientific observation model), and several others.

In relation to the user-centered cognitive approach to information retrieval, we can argue that an ontology-based approach attempts to solve the challenge of users’ individual comprehension by engineering semantically rich models developed to be sound, flexible, reusable, and meaningful to all users. With this in mind, one motivation of the study presented in this paper is to explore users’ comprehension of the information they need and how this aligns with and is expressed in the CIDOC CRM ontology.

Methods

This study aims to explore the actual information needs of users and how this aligns with the classes and properties defined in the CIDOC CRM and related domain-specific extensions. CIDOC CRM was selected as the preferred ontology due to its widespread use and extensibility, which accommodates concepts and information present in cultural-heritage data across various domains. The study is based on a naturalistic approach with a qualitative field-research method called Contextual Inquiry used for exploring the real needs of users in their natural settings. For decades, researchers employing positivistic (rationalistic) methodologies have carried out laboratory and experimental inquiries into users’ information behavior, seeking quantifiable and statistically analyzable insights. Nonetheless, as WildemuthCitation27 elucidates, laboratory studies suffer from limitations: they do not capture a comprehensive, unbiased account of individuals’ actions, convictions, and inclinations; they do not delve into people’s conduct within the framework of their own professional and personal spheres; they lack the capacity to deeply observe specific contextual factors like environments and artifacts; and they do not unveil implicit meanings and shared understandings inherent in communication and social interchange. On the contrary, the naturalistic paradigm, as articulated by Lincoln and Guba,Citation28 proposes that realities exist as integrated wholes inseparable from their contexts. This viewpoint discourages dissecting them for isolated examination of components while still emphasizing a holistic approach, asserting that the entirety surpasses the mere sum of its individual parts. Users’ information needs manifest as subjective, cognitive constructs formed during their interactions with their surroundings. Gaining a profound understanding of this construct necessitates qualitative research, wherein the researcher immerses themselves in the participants’ experiences and engages with them on a meaningful level.Citation29 As asserted by Corbin and Strauss,Citation30 the primary motivation behind opting for qualitative research is the aspiration to transcend the known and enter the participants’ realities, embracing their perspectives and, thereby, unearthing insights that enrich empirical knowledge development. Hence, contextual inquiry emerges as the most fitting approach to delve into users’ genuine information needs within their natural settings in this study.

Contextual inquiry is a qualitative field-research method and essentially involves immersing oneself in the users’ work environment, observing their activities, and engaging in discussions about their experiences.Citation31 By witnessing users’ authentic engagement in tasks, researchers unearth nuanced information about their activities, often revealing insights that users might struggle to articulate.Citation32

Participants in our study were selected purposefully, and included PhD candidates who were working with complex tasks and were assumed to regularly engage in search activities using different cultural heritage information systems and are active searchers. During the purposive sampling, primary focus was on recruiting a diverse group of PhD candidates from various academic disciplines who were potential users of library resources, museum artifacts, and archival materials. We also made a deliberate effort to ensure a balanced representation of genders among the participants and to include individuals at different stages of their respective PhD projects. To identify and enlist participants, a variety of online sources were employed. These sources encompassed the university’s official website, websites associated with various museums, faculty webpages from diverse departments, and the profile pages of PhD candidates. These profiles provided information about their respective PhD projects, such as titles and topics, and occasionally offered brief descriptions of their projects, their research interests, any published work, and the date of most recent updates to their pages, which allowed us to avoid including outdated information. The selection of participants for this study was primarily based on their geographical proximity to the researcher, located in Oslo. The chosen participants, aged between 30 and 55, represent a diverse group in terms of gender and nationality. Their fields of expertise covered a wide spectrum, including history, law, archaeology, social science, library and information science, literature, and biology.

Data collection in a natural setting was conducted through semi-structured interviews and observations. Participants have been observed and interviewed about their own information needs and search experiences in the context of their PhD research projects, with a preference for conducting these interactions at their respective workplace. This approach allowed us to gain insights into their actual information needs and search experiences. Participants were requested to discuss their most recent or ongoing information needs and either perform new searches or recreate their recent search activities, demonstrating their approach to finding answers to their specific information needs. Participants were given the freedom to use any information systems they preferred and to conduct as many search tasks as they deemed necessary (or replicate their recent searches) and formulating their own queries to meet their individual information needs within the context of their PhD projects.

Each of these contextual interview and observation sessions was conducted in English, lasting between 45 to 110 minutes, and was audio-recorded. Over the course of 12 hours of contextual interviews, 26 search events were observed, and a sum of 43 information needs were collectively expressed by 9 participants.

The data gathered for this study yielded a substantial volume of unstructured information. This included audio recordings of interview sessions, notes from observations, verbatim transcripts of interviews (encompassing various observed search events and interviews), researcher memos (in the form of research journals), and some screenshots depicting instances of participants’ replicated search activities. The resulting data has been analyzed through different phases. As part of the analysis, the information needs of researchers were illustrated as stories which include both the contextual information and the search events for each participant. These stories have become the bases for the next phase of the analysis, which we describe as an ontological analysis. Through ontological analysis, it becomes possible to semantically conceptualize users’ information needs by recognizing entities, relationships, and prevalent patterns within those needs. Information needs of participants have been expressed using CIDOC CRM classes and properties, subsequently visualized via network diagrams. Each diagram represents an information need and the query that has been used during the search event. In the final phase of analysis, general patterns of information needs have been recognized and modeled in CIDOC CRM through comparative analysis. The modeling is generalized into a set of patterns describing various information needs. In naming these general patterns, the researchers drew inspiration from the principles of CIDOC CRM to label these identified patterns accordingly.

The process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting qualitative data is a time-intensive endeavor, resulting in common constraints such as limited sample sizes and substantial time commitments, which this study also encountered. Consequently, it was not feasible to encompass all conceivable user information needs comprehensively. Moreover, the inherent subjectivity of qualitative data stemming from specific contexts complicates the application of traditional reliability and validity criteria. The replication of qualitative studies is impeded by the central role played by the researcher and the inability to recreate unique contexts, making it challenging to duplicate the precise outcomes of this study. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, the qualitative researcher, serving as the primary tool for data collection and analysis, establishes a closer connection to reality through direct observations and interviews, thereby enhancing internal validity of the study.Citation33

Results

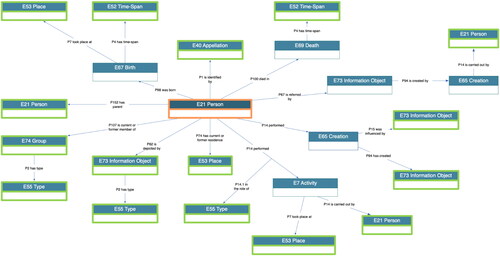

This part presents the outcomes of the analytical procedures. The results from the data analysis in the prior two phases are generalized into trends or patterns in the information needs of participants seeking cultural-heritage information. These information needs have been interpreted directly from participants’ expressions and subsequently modeled using CIDOC CRM and its extensions. The ontological representation encapsulates fundamental and simplified patterns that are substantiated by empirical findings within this study’s user information needs analysis. In most of these overarching patterns of user’s information needs, the target of information seeking is one of the principal notions of Actor (E39), Thing (E70), or Event (E5). Participants are particularly looking for: Actors who have created something, are collaborating on something, or are recipients of someone’s communication; Things that are created by an actor, inspired by another entity, refer to an actor, event, or thing, or represent a translation of another entity; Events or activities that are associated with a specific entity. However, there are also cases where users are not specifically seeking information about the individual entities of Actor (E39), Thing (E70), or Event (E5). Instead, their interest encompasses all entities associated with these three principal notions. In other words, the users are looking for comprehensive information that spans across the various entities associated with Actor, Thing, and Event, providing a broader context for understanding these main entities.

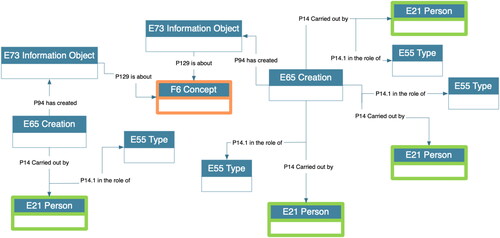

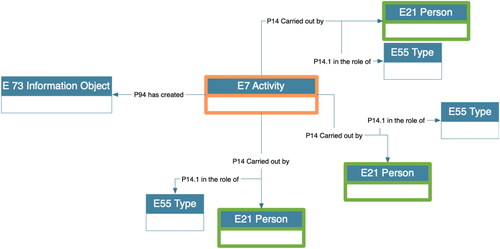

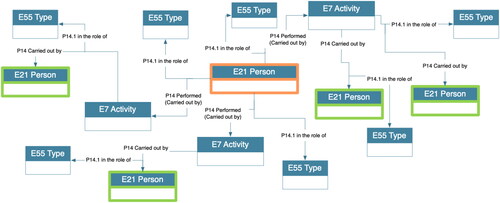

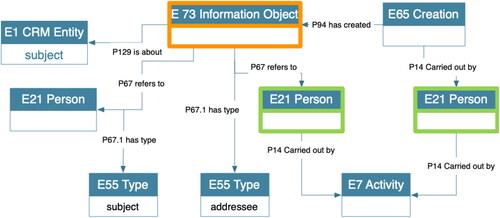

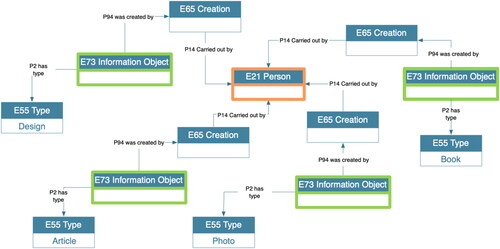

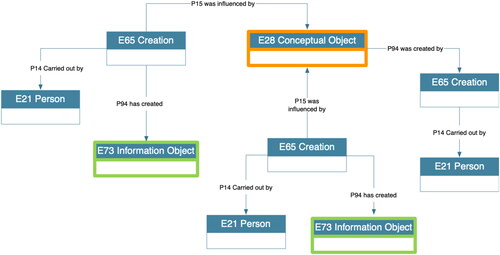

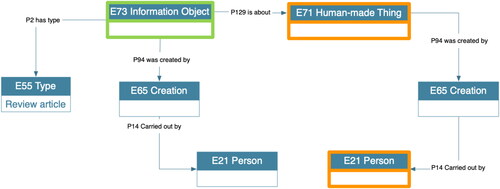

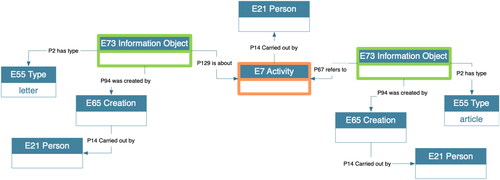

In the upcoming section, we offer an ontological representation of the general patterns observed in participants’ information requirements as they seek cultural-heritage information. Each pattern will be introduced with a description and an ontological diagram displaying its structure, accompanied by real examples extracted from participants’ search activities. The primary CIDOC CRM classes in these patterns are highlighted with an orange border and the classes that represent the user’s actual information need are presented with a green border. Each rectangle represents a particular instance of the class it is labeled with. Some instances have additional notes to distinguish between them. In some patterns we have included multiple instances of the same type to indicate that users would be interested in a variety of instances. In the pattern’s presentation, the use of E39 Actor is replaced with the subtype E21 Person, for the simple reason of readability and the fact that the majority of instances included persons and not the other subtypes of E39 Actor.

Pattern 1: Network of people working on a concept

The pattern of Network of people working on a concept () focuses on individuals engaged in collaborative or individual activities related to a specific concept. This pattern is centered around individuals and addresses a segment of users’ information needs where they seek to identify individuals who have worked on a particular concept (F6). An instance illustrating this pattern involves a participant searching for individuals who have written about a specific concept, aiming to identify potential interviewees. The query he employs represents a specific subject of interest. However, the underlying information requirement driving this focused search diverges notably from the typical exploratory subject-based searches. In conventional exploratory searches, users generally seek information or materials directly related to the chosen topic. In contrast, the motivation behind this particular topic-driven search extends beyond merely seeking information resources like books or articles. The primary objective here is to identify individuals or organizations who have produced content about this subject. This stems from his intention to identify potential interviewees among those who have engaged with this topic. Hence, individuals (E21 Person) become the primary focus of the participants’ information needs.

Pattern 2: Network of collaborators on an activity

The patten of Network of collaborators on an activity () covers the realm of collaboration, encompassing details about the collaborators themselves and the distinct roles each person assumes within the collaborative effort. The central element within this pattern is a specific activity (E7), undertaken by various individuals (E21). Within this framework, each collaborator (E21 Person) can engage in the activity while taking on a specific role (p14.1) of any type (E55). An instance exemplifying this pattern is seen in the case of a participant seeking individuals who have participated in the creation (E7) of a specific law. The participant initiates a search query based on the law’s name; nevertheless, the primary objective behind this pursuit deviates from a standard topic-oriented exploration. Instead, the participant’s focus lies in pinpointing the individuals who contributed, directly or indirectly, to the development of the law. Central to this user’s information requirement within this pattern is the identification of persons engaged in cooperative efforts related to a specific activity.

Pattern 3: Person’s collaborators

The pattern of Person’s collaborators () focuses on the individuals (E21 Person) who engage in activities (E7) alongside a specific person (E21). These individuals may assume various roles within these activities, roles that can be delineated in the model using the concept of type (E55). This pattern addresses the information requirements of users who are interested in gaining a comprehensive understanding of a specific individual’s professional connections. An illustrative instance of this pattern arises in the case of a participant who is actively seeking information about individuals who have collaborated with a particular designer over the course of the designer’s career. Additionally, the participant is keen on obtaining specifics about the roles undertaken by these collaborators in their joint projects. To embark on this quest, the participant initiates a search using the designer’s name as the query with the explicit intention to uncover details about the designer’s collaborative efforts. This entails not only identifying the individuals with whom the designer has partnered but also understanding the projects they have jointly undertaken. In this scenario, the participant’s primary objective is to get insights that could spark innovative perspectives for the participant’s own research project.

Pattern 4: Addressee of correspondence

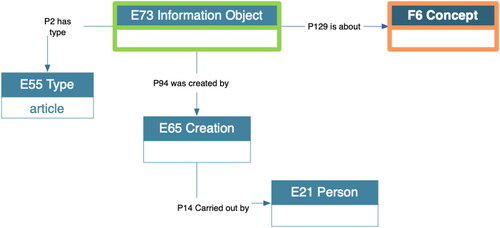

The pattern involving the recipient of an individual’s correspondences () encompasses the scenario where a person (E21) composes a letter (E73 Information Object) intended for a specific recipient, noted within the letter as the addressee. The content of the letter can pertain to or reference any subject matter (E1 CRM Entity). An instance illustrating this pattern is found in the experience of a participant who has initiated a query on a designer’s name and comes across a letter composed by the designer. In this case, having prior knowledge of the designer, the participant’s current objective is to uncover the intended recipient of the letter, alongside any potential collaborative interactions between them. In essence, the participant endeavors to locate the addressee (E21 Person) of the communication (E73 Information Object), while also delving into the subject matter of the letter (that is shown by property ‘P129 is about’). The pattern of Addressee of correspondences can also serve as a starting point for users to discover a person’s collaborators. Much like this trend, HennickeCitation34 identified the correspondence pattern as one of the patterns observed in the study of archival users’ reference queries. In his thesis, he introduced some new properties to complement the CIDOC CRM properties used for ontologically representing this pattern. His intention was to encompass both instances of composing a letter with the intent to send it to someone and creating a speech meant for an audience. However, in the current study, the addressee’s pattern for correspondence is depicted using the existing CIDOC CRM classes, properties, and sub-properties.

Pattern 5: Works created by a person

The pattern of Works created by a person () centers on works that a person has generated through creative activities. A person (E21) can engage in various creative activities (E65 Creation), yielding diverse outcomes including instances of Informational Objects (E73) or Physical Human-Made Objects (E24). This pattern is valuable for addressing some participants’ information queries, such as identifying all publications written by a specific author, the sweater design created by a designer, the photos captured by a particular travel writer, and the books authored by a certain individual. These books, photos, articles, and designs are categorized as information objects (E73) originating from creation activities (E65 Creation) conducted by distinct individuals (E21). In each of these instances, the participants commence their exploration by inputting a query based on the name of a particular individual.

Pattern 6: Works inspired by a conceptual object

The pattern of Works inspired by a Conceptual Object () revolves around the idea of deriving creative inspiration from the works of others while producing something new. Within this framework, during the process of crafting a new creation, an individual (E21) undertakes a creative endeavor (E65 Creation) that is influenced by the ideas present in a distinct work previously created by another person (E21). An illustration of this pattern can be seen in the case of the participant who initiates a query on a specific topic and the name of a particular sociologist. The participant’s intent in this search is to locate research articles (E73 Information Object) that have employed a distinct theory (E89 Propositional Object) proposed by this sociologist. In this specific case, the participant possesses prior knowledge about the sociologist. Her objective is to delve into the utilization of this sociologist’s theories by other scholars in their own academic works. The participant’s intention is to gain insights into the various ways in which these theories have been incorporated and applied within scholarly discourse. This endeavor reflects a desire to comprehend the broader impact and influence of the sociologist’s theoretical framework across the academic landscape.

Pattern 7: Discussions around a person and/or person’s created work

The pattern of Discussions around a person and/or person’s created work () centers on conversations held by others about a specific individual and/or their accomplishments. These discussions not only pertain to the person but also implicitly encompass the activity (E65) carried out by that person and the resultant work produced from that activity (E65) that can be either a conceptual object (E28) or a physical, human-made thing (E24). This pattern addresses the segment of users’ information needs where they seek to find what has been communicated about a particular individual (E21), their activities (E7), and the work they have created. Such insights help users gain a deeper understanding of the person and their contributions. Instances of this pattern are evident when participants express their interest in accessing conversations related to a specific designer and her particular design, discussions about a certain translator and her translated book, as well as implicit discussions about the book’s translation, or even discussions about a particular book or article authored by an individual. The information objects capable of fulfilling such need can be of various types (E55), such as a review article, a critique published in a newspaper, discussions or interviews on television programs, and more. What makes this pattern intriguing is that in all these instances, participants initiate searches using the name of a person.

Pattern 8: Discussions around an activity

The pattern of Discussions around an activity () reflects an information need where the user seeks any form of documented information associated with a specific activity (E7) undertaken by an individual (E21) or a group of people. An illustration of this pattern can be observed in the case of a participant who aims to locate all available textual information regarding a travel writer’s expedition (E7 Activity). As described by the participant, the desired information could be encompassed within various types of information objects (E73), including a government funding document, letters granting access to specific locations, the travel writer’s written travel book, and more. Despite this diversity of potential sources, the participant begins his search by simply entering the travel writer’s name as the search query.

The pattern illuminates the intricacies of users’ information needs, traversing through distinct activities while encompassing a spectrum of information object types and formats. Essentially, the pattern showcases how users may have varying requirements when seeking information related to specific activities.

Pattern 9: Discussions around a concept

The pattern of Discussions around a concept () centers on a specific concept often recognized as a subject or topic, however the heart of the information need of the user is spanning a variety of information object types and formats. Given that concepts can be interpreted diversely across communities, this pattern caters to users seeking insights into how a specific concept has been deliberated within their own field or across various fields. An illustration of this pattern can be observed in the information needs of a participant who aims to explore how the concept of materiality has been employed and debated within the realm of archaeology. The information objects (E73) containing such discussions could have different formats like journal articles, books, or newspaper articles. In practice, the participant initiates a search using the query “materiality archaeology,” a combination of the central concept and the specific field of study, aiming to find relevant materials that address the intersection of materiality and archaeology.

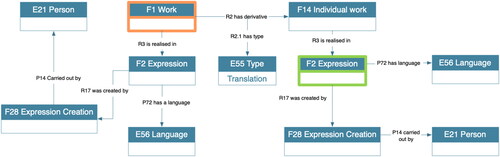

Pattern 10: Translation of a work

The pattern of Translation of a work () focuses on the notion of linguistic objects, which are identifiable expressions in natural languages. Within the CRM framework, a linguistic object is considered distinct from the medium through which it is conveyed. This pattern encompasses instances where a written text has been translated into a different language. An illustrative example of this pattern is a participant commencing a search for an English-language edition of a book, even though they already have a copy of the book in Spanish. In this scenario, the participant undertakes a search using a query on a phrase that includes a portion of the book’s title. The participant’s objective is to find the English translation of the book for quoting purposes in his work and prefers not to use quotes in Spanish. In this study, we have structured the work’s translation pattern using CIDOC CRM classes and attributes. Nevertheless, it could also be represented in an alternative manner using FRBRoo classes and attributes as shown by Aalberg et al.Citation35

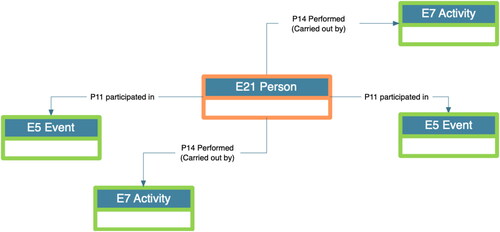

Pattern 11: Event/activity related to a person

The pattern Event/activity related to a person () is centered on documented activities undertaken and events that transpired throughout the lifespan of an individual. An illustrative example of this pattern is the participant who initiates a query on the name of a recently discovered author and aims to uncover all research activities undertaken by this author. In this pattern, activities (E7) or events (E5) related to a particular person are the target of information need. This pattern has the capacity to offer users novel perspectives by showcasing diverse activities associated with an individual, aiding them in discovering new facets within their research.

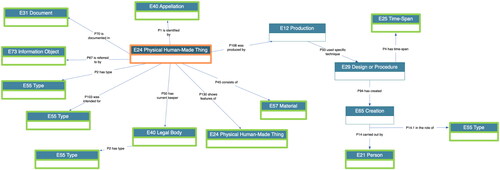

Pattern 12: Associated details concerning a particular entity

The pattern of Associated details concerning a particular entity demonstrates a specific interest of user in discovering factual information that pertains to specific identifiable entities of the classes of Actor, Thing, or Event. This pattern is dedicated to users who seek comprehensive, factual knowledge about actors, things, and events, and it provides a framework to help them access various aspects of this information in a structured and organized manner.

An example of this pattern is seen in the case of a participant who initiated a search using a query on the name of a travel writer aiming to uncover comprehensive information regarding the travel writer’s journeys to the North (E7 Activity). Anything associated with this specific activity (E7)—whether it involves individuals, documents, references to time and place, or other interconnected activities—can arouse curiosity for this participant.

Another example of this pattern is the participant who seeks to gather comprehensive information about a specific sweater (E22 Physical Human-made Thing). In this case also, the participant initiates a query on the name of the designer who has designed the sweater. The sought-after information spans from intricate details concerning the sweater’s physical attributes, such as its color, material, texture, design, and potential title, to its intended purposes and exhibition location(s).

When it comes to acquiring factual information about an individual (E21 Person), instances include the participants who were driven to collect comprehensive information concerning a specific person featured in search result listings. The type of information that aligns with these participants’ requirements encompasses aspects like the person’s image, overarching biographical data, profession, affiliations, created works, and the person’s activities. Illustrations showcasing this pattern are depicted in for information related to a specific thing and for information related to a specific person. The heart of this pattern is that users would be interested in a range of entities and properties directly or indirectly associated to the known entity in the search. This pattern has the potential to spark novel ideas by offering diverse forms of related information aligned with users’ search objectives.

Discussion

In this study, participants were engaged in their own search tasks aimed at satisfying their PhD project-related information needs. In contrast to typical Information Retrieval (IR) studies, we tried to maintain a setting that closely resembled real-world situations by avoiding predefined search tasks, predetermined information needs, and specific information retrieval systems. This approach allowed us to uncover invaluable insights into the participants’ real information needs, enhancing our comprehension of their mental frameworks within the genuine working context. In other words, the insights were not artificially constructed or biased; rather, they provide a true reflection of the participants’ actual information needs, behaviors, and thought processes as they naturally occur in their everyday work environment.

The sample size of this study is limited, which affects the level to which our findings can be generalized. However, despite this limitation, we took deliberate steps during the sampling process to encompass diverse demographics. We made sure to include participants from various genders, fields of expertise, nationalities, and stages of research projects. Specifically, in most cases, we conducted interviews with at least two participants within each field to ensure a broader representation and minimize potential biases. This approach aimed to capture a more comprehensive range of perspectives within the constraints of our sample size, enhancing the depth and diversity of insights despite the inherent limitations in generalizability due to the smaller sample.

In this research, a distinctive analytical approach has been applied to examine qualitative data created by interviewing a group of researchers, leading to the creation of models that represent patterns of researcher’s information needs. These patterns have been articulated using CIDOC CRM’s classes and properties. The results illustrate the most prominent and simplified patterns, primarily based on empirical evidence derived from users’ information needs observed in this study. The findings of this investigation underline the diverse nature of information needs that queries can represent, making the task of retrieving pertinent data challenging for information systems. However, the emerging patterns could serve as a guide in identifying categories of information that users seek. This shift toward identifying patterns may be used to bring information systems closer to how users conceptualize information.

While comprehensive ontologies like CIDOC CRM encompass a wide range of entities and properties to provide thorough and detailed semantic explanations for fragments of information, this inclusiveness might present challenges during implementation. However, the findings of this study uncover overarching patterns indicating it is relevant to build information systems that utilize a limited selection of entity types and properties as searchable access points when designing search and retrieval features for ontology-based information, while still effectively addressing diverse information needs. How to design and implement search and exploration in ontology-based data has not been in the scope for this work but is highly relevant as future research. Patterns such as we have identified, can serve to guide the implementation of the transformation layer that is needed between the user interface that end users are interacting with and the lower-level indexing and retrieval of ontology-based data. The overarching patterns and types of information needs discovered in this study pertain specifically to complex tasks and expert researchers, necessitating validation in different contexts. Furthermore, given the exploratory nature of this research, it is essential to emphasize the need for future studies with larger, more targeted samples to validate, expand upon, and enhance the generalizability of these findings. Although generalizing to other populations is limited due to the nature of this exploratory research, the emerging concepts and patterns hold promise in shedding light on the information needs of users tackling complex tasks. It is also hoped that this study will motivate the Library and Information Science community to conduct additional research employing an ontology-based approach to effectively organize and present cultural heritage information, catering to users’ semantic information needs more comprehensively. Moreover, the idea of improving information indexing through consideration of entities and their relationships also merits further exploration.

Another area for future research with notable promise involves the exploration of the spatial separation and routes connecting query entities and entities corresponding to information needs.

To conclude, the study’s significance lies in the introduction of a promising methodology, which offers invaluable new insights into comprehending users’ information needs through qualitative and empirical studies. The identified patterns in this study aim to shed light on the diverse and complex nature of users’ information needs which should be taken into account when designing future information systems. This approach will help in building integrated systems capable of supporting various information needs, ultimately enhancing the efficiency of information retrieval processes. Another significant outcome of this research is the recognition of the need to shift from query-focused information systems to pattern-centric information systems.Citation36

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- CIDOC CRM Special Interest Group. Definition of the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (International Committee for Documentation, May 2023), https://www.cidoc-crm.org/Version/version-7.2.3.

- Robert S. Taylor, Question-Negotiation and Information Seeking in Libraries (Studies in the ManSystem Interface in Libraries, Report no. 3, July 1967).

- William J. Paisley and Edwin B. Parker, “Information Retrieval as a Receiver-Controlled Communication System,” in Proceedings of the Symposium on Education for Information Science (Washington, DC: Spartan Books, 1965), 23–31.

- Ian Ruthven and Diane Kelly, eds., Interactive Information Seeking, Behaviour and Retrieval (Facet Publishing, 2011).

- Brenda Dervin and Michael Nilan, “Information Needs and Uses,” Annual Review of Information Science and Technology 21 (1986): 3–33.

- Brenda Dervin, “Information as a User Construct: The Relevance of Perceived Information Needs to Synthesis and Interpretation,” in Knowledge Structure and Use: Implications for Synthesis and Interpretation, ed. Spencer A. Ward and Linda J. Reed (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1983), 155–83; Brenda Dervin, “From the Mind’s Eye of the User: The Sense-Making Qualitative-Quantitative Methodology,” Qualitative Research in Information Management 9 (1992): 61–84.

- George Alexander Kelly, Clinical Psychology and Personality: The Selected Papers of George Kelly, ed. Brendan Arnold Maher (Wiley, 1969).

- Peter Ingwersen, “Search Procedures in the Library—Analysed from the Cognitive Point of View,” Journal of Documentation 38, no. 3 (1982): 165–91. doi:10.1108/eb026727

- Kelly, Clinical Psychology.

- Tom D. Wilson, “The Cognitive Approach to Information-Seeking Behaviour and Information Use,” Social Science Information Studies 4, no. 2-3 (1984): 197–204. doi:10.1016/0143-6236(84)90076-0

- Nicholas J. Belkin, “Anomalous States of Knowledge as a Basis for Information Retrieval,” Canadian Journal of Information Science 5, no. 1 (1980): 133–143.

- Nicholas J. Belkin, Robert N. Oddy, and Helen M. Brooks, “ASK for Information Retrieval: Part I. Background and Theory,” Journal of Documentation 38, no. 2 (1982): 61–71. doi:10.1108/eb026722

- Pia Borlund, “The Cognitive Viewpoint: The Essence of Information Retrieval Interaction,” in The Janus Faced Scholar. A Festschrift in Honor of Peter Ingwersen (Royal School of Library and Information Science, 2010), 23–34.

- Tefko Saracevic, “The Stratified Model of Information Retrieval Interaction: Extension and Application,” Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Information Science 34 (1997): 313–27.

- Brenda Dervin, “Sense‐Making Theory and Practice: An Overview of User Interests in Knowledge Seeking and Use,” Journal of Knowledge Management 2, no. 2 (1998): 36–46. doi:10.1108/13673279810249369

- Peter Ingwersen, “Cognitive Analysis and the Role of the Intermediary in Information Retrieval,” in Intelligent Information Systems (Horwood, 1986), 206–37.

- Peter Ingwersen and Kalervo Järvelin, The Turn: Integration of Information Seeking and Retrieval in Context (Springer, 2005).

- Tom D. Wilson, “Models in Information Behaviour Research,” Journal of Documentation 55, no. 3 (1999): 249–270. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000007145

- Elaine G. Toms, “Task-Based Information Searching and Retrieval,” in Interactive Information Seeking, Behaviour and Retrieval, ed. Ian Ruthven and Diane Kelly (Facet, 2011), 43–60.

- Ibid.

- Thomas R. Gruber, “Toward Principles for the Design of Ontologies Used for Knowledge Sharing?,” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 43, no. 5-6 (1995): 907–28. doi:10.1006/ijhc.1995.1081

- Pragya Agarwal, “Ontological Considerations in GIScience,” International Journal of Geographical Information Science 19, no. 5 (2005): 501–36. doi:10.1080/13658810500032321

- Leo Obrst, “Ontologies for Semantically Interoperable Systems,” in Proceedings of the Twelfth,” International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (Association for Computing Machinery, 2003), 366–9. doi:10.1145/956863.956932

- Maja Žumer and Patrick Le Bœuf, “Conceptual Models: Museums & Libraries: Towards an Object-Oriented Formulation of FRBR Aligned on the CIDOC CRM Ontology,” in New Tools and New Library Practices, 30th ELAG Seminar (Bucharest, 2006).

- International Working Group on FRBR and CIDOC CRM Harmonisation. FRBR Object-Oriented Definition and Mapping from FRBRER, FRAD and FRSAD (International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, September 2017), https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/659.

- IFLA LRMoo Working Group with the CIDOC CRM Special Interest Group. LRMoo (Formerly FRBRoo) Object-Oriented Definition and Mapping from IFLA LRM (Currently Under Review for Approval by International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, May 2023), https://www.cidoc-crm.org/frbroo/ModelVersion/lrmoo-formerly-frbroo-version-0.9.4

- Barbara M. Wildemuth, ed., Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science, 2nd ed. (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016).

- Yvonna S. Lincoln and Egon G. Guba, Naturalistic Inquiry, vol. 75 (Sage, 1985).

- Linda Dale Bloomberg and Marie Volpe, Completing Your Qualitative Dissertation: A Road Map from Beginning to End (Sage Publications, 2018).

- Juliet M. Corbin and Anselm Strauss, Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed. (Sage Publications, 2008).

- Karen Holtzblatt and Hugh Beyer, Contextual Design: Evolved (Morgan & Claypool, 2014); Hugh Beyer and Karen Holtzblatt, “Contextual Design,” Interactions 6, no. 1 (1999): 32–42; Mary Elizabeth Raven, and Alicia Flanders, “Using Contextual Inquiry to Learn about Your Audiences,” ACM SIGDOC Asterisk Journal of Computer Documentation 20, no. 1 (1996): 1–13. doi:10.1145/227614.227615

- Holtzblatt and Beyer, Contextual Design.

- Sharan B. Merriam and Elizabeth J. Tisdell, Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation (John Wiley & Sons, 2015).

- Steffen Hennicke, “What is the Real Question? An Empirical-Ontological Approach to the Interpretative Analysis of Archival Reference Questions” (PhD diss., Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 2017).

- Trond Aalberg, Audun Vennesland, and Maliheh Farrokhnia, “A Pattern-Based Framework for Best Practice Implementation of CRM/FRBRoo,” in New Trends in Databases and Information Systems: ADBIS 2015 Short Papers and Workshops, BigDap, DCSA, GID, MEBIS, OAIS, SW4CH, WISARD, Poitiers, France, September 8-11, 2015. Proceedings (New York City: Springer International Publishing, 2015), 438–47.

- Maliheh Farrokhnia, “Searching for Cultural Heritage Information: Ontology-Based Modeling of User Needs” (PhD diss., Oslo Metropolitan University, 2019).