ABSTRACT

Background & aims

Confidence is a crucial yet poorly understood concept in rehabilitation. Therapies enhancing confidence lack specificity and confidence outcome measures vary. This review aimed to explore therapy techniques designed to impact confidence in stroke survivors, identify outcome measures used to assess confidence and to define the core components of confidence treatments. Particular consideration was given to treatment of confidence in people living with communication disorders, such as aphasia.

Methods

Databases were searched using the scoping review framework. Published, peer reviewed, English language articles focused on stroke rehabilitation with measurements and explorations of confidence/self-efficacy were included. Studies were allocated to treatment category groups based on authors’ descriptions of the intervention.

Results

Nine thousand and one records were screened, 516 assessed, and 26 studies included. Studies were categorised into intervention types: self-efficacy, self-management, impairment-based or technology-incorporated interventions, with a few unique, non-recurring approaches (such as drama therapy). Twenty-three quantitative and six qualitative measures were extracted. Quantitative measures included standardized assessments (scales or questionnaires), or study-specific measures. The most common measure was the “Stroke Self-Efficacy Questionnaire”.

Conclusion

With respect to treatment components, there were overlaps between many studies. There was not a specific approach that was clearly associated with enhanced confidence outcomes. Rather, interventions implemented elements of multiple approaches. There were a few therapies whose primary focus was improving confidence. Specifically, only three studies explicitly sought out to “regain confidence” or “change self-efficacy” or focus on self-efficacy outcomes. Other studies examined confidence as a secondary outcome. There was a pattern of using general stroke-specific confidence/self-efficacy related outcome measurement tools rather than context/skill specific confidence/self-efficacy measurement tools. Though confidence is a crucial yet poorly understood concept in neurorehabilitation, this scoping review may contribute towards its development and maturation with the field.

Introduction

Annually, one in four individuals aged above 25 will experience a stroke in their lifetime (World Stroke Organization, Citation2022). A stroke is typically a life-altering event with ripple effects on physical, personal, and psychological aspects of an individual’s life. Rehabilitation may aim to remediate, adapt, or help adopt new skills, identity, or lifestyle. The rehabilitation process is a joint effort between stroke survivors and healthcare professionals in identifying relevant and achievable goals.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) model proposed by the World Health Organization is considered an ideal model to guide rehabilitation and research (Jahan & Ellibidy, Citation2017). The ICF model is dynamic by nature, as it considers “health” a construct of the levels of interaction between the body, person, and environment. It also takes into account how structure and function may interplay, either directly or indirectly, while considering the effects of impairments, limitations, and restrictions on the perception of disability (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2001). The consideration of environmental and personal characteristics of people with disabilities, and their personal experiences, perceptions and functioning may assist in the improvement in quality of life. Confidence may serve as a good example of such a personal characteristic that is impacted by experiences, perceptions, and functioning. Furthermore, the ICF model supports interventions directed to change behaviours (e.g., self-efficacy/confidence), adapt environments, and modify systems considering an individual’s well-being through individualized interventions with personalised outcomes. (Jahan & Ellibidy, Citation2017).

Collaborative efforts have been made to reach a consensus regarding research priorities in the areas important to stroke survivors, their care-givers and health professionals. Most topics identified have been directly stroke-related impairments such as mobility, communication (e.g., aphasia), and vision (Pollock et al., Citation2014). Another domain was the social limitation of living with, coping, and adjusting to stroke and how it affects confidence (Pollock et al., Citation2014). More recently, the Stroke Association identified priorities for research related to stroke and long-term care from the perspective of relevant stakeholders. Among the priorities mentioned was identifying ways to “support adjustment, improve motivation, wellbeing and engagement” as well as identifying interventions that would help remediate the long-term impact of stroke (Stroke Association, Citation2021). Although not explicitly mentioned, confidence and self-efficacy may be considered intrinsic to these concepts.

The term “confidence” has been discussed in the literature but vaguely defined. “Self-efficacy” is more commonly seen and sometimes used interchangeably with “confidence”. Self-efficacy has been defined as having the required precursor attributes to execute a specific task (A. Bandura, Citation1977). Others have described confidence as a construct of self-efficacy, self-esteem, and environmental factors that reflect on the independent capability to act (Horne, Citation2016). Confidence has been defined as a perception of abilities to execute a certain task (Babbitt & Cherney, Citation2010). Poulsen et al. (Citation2014) defined confidence as an “affirmation of capability level” (Poulsen et al., Citation2014). ICF defines confidence as a set of mental functions that produce a personal disposition that is self-assured, bold, and assertive (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2001). Within more mainstream accounts of confidence, it has been expressed as the ability to “bet on oneself” to succeed in a given task (Robertson, Citation2021). Confidence is seen to be composed of two main elements, the first being an internal component that stems from the belief that a certain act can be executed. The second component tends to be more external and relates to the expected outcome of this specific act for oneself within the environment. This trajectory gives rise to four possibilities: either a positive outcome, disengagement, self-doubt or hesitation in the certainty of outcomes. The most positive being the belief that a certain act can be executed, and it will have a positive outcome. This happens when the mind is engaged, leading to a stage of preparation and positive expectations. The least optimistic happens when the mind is disengaged with no interest in the outcomes. That leads to decreased motivation and loss of interest. The two remaining possibilities either lead to self-doubt or hesitance in the certainty of occurrence of an expected outcome. Both can lead to a state of anxiety, mood disturbances and shaken confidence (Robertson, Citation2021).

Disabilities that emerge following stroke typically have an adverse effect on an individual’s confidence/self-efficacy. Confidence is an area of mental functions that may also change due to alterations in temperament or personality functions (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2001). Reports of decreased confidence were present in stroke survivors due to activity limitations which decrease abilities to be independent (Rudd et al., Citation2017). Strokes have the ability to significantly impact the lives of stroke survivors, not only as time-limited disruptions at the acute stage of stroke illness but also in the long term, as stroke symptoms become chronic and established. There are long term effects that range from personal issues to social adjustment which stroke survivors need to adapt to after their stroke. Shift in life roles, isolation, and depression are only a few of the problems commonly seen after stroke (Jones & Riazi, Citation2011). Anxiety and depression were found to be the most common adverse psychological states accompanying aphasia (Laures-Gore et al., Citation2020; Zanella et al., Citation2023). Outcomes of these feelings may project as negative thoughts, low self-esteem, and decreased confidence. Decreased confidence is a vital communication barrier that may restrict stroke survivors from social participation and lead to social isolation only to exacerbate the issue even further.

The literature recommends and reiterates the need to create therapy methods to improve self-efficacy and confidence in stroke survivors (Flowers et al., Citation2016; Pollock et al., Citation2014) although a previous review found limited literature to guide this work. In a review of self-efficacy and self-management after stroke, Jones and Riazi (Citation2011) found 22 articles that support the notion that self-efficacy is an important determiner of post-stroke therapy outcomes. They concluded that there is a substantial need to develop interventions supporting self-management and confidence (Jones & Riazi, Citation2011). Wright et al. (Citation2017) conducted a systematic review on factors associated with post-stroke anxiety aiming to find an association between post-stroke depression and pre-stroke factors. They concluded that coping strategies and confidence may be targeted to help decrease post-stroke anxiety (Wright et al., Citation2017).

Following the ICF model’s holistic approach to health, personal characteristics such as confidence/self-efficacy can be seen as stemming indirectly from effective treatment (i.e., secondary goal) or directly as the main focus (i.e., a primary goal). A search of the literature to identify the current state of rehabilitation methods and outcome measures within may be helpful in achieving a better understanding of therapy techniques that impact confidence either directly or indirectly. In addition, to the best of our knowledge, there are no previously published systematic reviews covering the topic of therapy techniques for confidence in rehabilitation with stroke survivors.

Aims

The aim of this scoping review is to explore current practices related to self-confidence therapies in stroke rehabilitation and identify confidence outcome measures. A particular focus will be given to literature related to communication confidence to aid and inform the development of a bespoke speech and language therapy program for people with aphasia in the future. Specifically, this paper aims to:

Explore treatment approaches targeting or impacting on confidence/self-efficacy in stroke rehabilitation.

Identify confidence/self-efficacy related outcome measures used in the context of stroke rehabilitation research literature.

Methods

Due to the developing evidence related to confidence and self-efficacy in the field of stroke rehabilitation and the desire to “map the literature on a particular topic” and “identify types and sources of evidence”, scoping review methodology was used to explore the literature (Daudt et al., Citation2013, p. 8). This scoping review followed the framework suggested by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005). The five stages of a scoping review framework were applied. The first stage was the identification of the research question, then the identification of relevant studies, followed by selecting included studies, then charting data, and finally collating, summarizing and reporting results (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005).

Research question

Specifically, this paper will address the following questions:

What approaches are evident in the literature to treating or impacting confidence within the context of: a. stroke rehabilitation, and b. communication?

What outcome measures have been utilised?

Protocol and registration

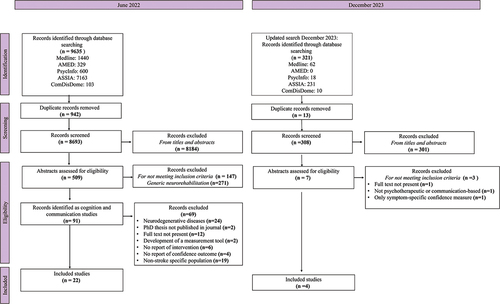

The scoping review protocol complied with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines and was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on May 24, 2022 (Registration No. CRD42022327454). PRISMA-ScR guidelines were also followed during the design and preparation of the scoping review (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Information sources and search strategy

The following relevant databases in the field of neuropsychology and rehabilitation were searched: Medline, AMED: Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, PsycINFO, ASSIA: Applied Social Sciences Index and abstracts and ComDisDome. Databases were searched from the earliest year recorded in each database to June 2022, with no limits imposed on the searches. The search was re-run for updates in December 2023. The development of a search strategy was supported by librarians and based on terms to identify studies related to confidence and/or self-efficacy in the context of rehabilitation of acquired neurogenic disorders. Search terms were initially supplemented with a comprehensive list of acquired neurological disorders that was used based on a published Cochrane review interested in a population of stroke or other adult non-progressive acquired brain damage (Chung et al., Citation2013). Only stroke-related records were identified from this initial search then a strictly stroke-related search strategy was applied to update search results in December 2023. For an example of the search strategy, see Appendix A.

Study eligibility and selection

Duplicates were removed using Endnote 20.2 software and the Rayyan website (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016). Titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion or exclusion using the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Published, peer reviewed, English-language articles related to rehabilitation techniques in adults, with a diagnosis of stroke with empirical data and/or protocols related to intervention.

Papers in which the abstract mentions confidence /self-efficacy as a target and/or measured outcome.

Speech and language specific confidence outcome measures.

Psychotherapeutic or communication-based studies.

Exclusion criteria

Review papers, posters, books, and conference proceedings.

Papers not reporting or exploring confidence/self-efficacy or confidence outcome measures in abstracts.

Papers pertaining to neurodegenerative diseases e.g., Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease etc.

Papers reporting only non-relevant “symptom specific” measures (eg balance confidence scale) in the abstract.

Papers discussing medication treatments and pharmaceutical interventions.

Papers reporting confidence in relation to carers or others and not the individual undergoing treatment.

Titles and abstracts were manually screened. The full text of publications was assessed for inclusion in the review. Any disagreements about study inclusion were resolved through discussion with co-authors and reasons for study exclusion were recorded. The results are presented in as a PRISMA Flowchart.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction

Data extraction was completed while recording the following: (1) aims of the study, (2) participant details (sample size, diagnosis) (3) description of intervention methodology (type, theory, duration, frequency), (4) profession providing treatment, (5) treatment highlights, (6) confidence related analysis (outcome measurement tool, therapy outcome regarding confidence) in addition to study identifiers such as manuscript title, author, and year of publication. All extracted data was based solely on the paper authors self-reporting in their abstracts and/or methods. Data was recorded in an excel spreadsheet. A copy of the data extraction form is provided in Appendix B.

Data synthesis

Data synthesis was based on the description of studies offered by the authors in each case. The included records were analysed and synthesised based on study characteristics and reported aspects of the study intervention. Study characteristics include year of publication and participant diagnosis. Reported aspects such as intervention approaches and outcome measures were also used to synthesise the included records. Studies were grouped based on the intervention reported in each study, each group included studies that mentioned a specified theory, framework, approach, or mode of delivery the study intervention used. We were not focused on critically appraising the quality of studies or the authors accuracy of self-reported treatment approach in this scoping review.

Results

Systematic search results

The 26 included records were published in the fields of cognition or communication with psychotherapeutic or communication approaches. These studies were further grouped based on the reported underpinning theory, treatment approach, overarching theme, or technique used for each study intervention.

Study characteristics

Included studies are displayed in , organised by intervention approach/theory (see below) then chronological order. An analysis of study characteristics is explained below.

Table 1. Summary of included studies based on intervention then chronological order.

Participant diagnosis

All included studies focused on stroke survivors (n = 26). Ten of these studies specified working with participants with aphasia and one with anomia (word-finding difficulty).

Intervention approach: The included studies were grouped based on the theoretical underpinning of a study provided by the authors, in that the therapy was based on a broader theory of intervention or an overarching theme for intervention. Overall, there were 5 groupings created for the purposes of this paper summarized in . The authors of four studies mentioned the use of an impairment-based or symptom-focused treatments where the main goal of their treatment was remediating a specific skill, with measurement of confidence as a secondary outcome. There were seven reports of implementing a self-efficacy approach (n = 7), with Bandura’s self-efficacy theory (A. Bandura, Citation1977) specifically mentioned in some of the included studies, adapting concepts of “mastery and vicarious experiences” implementing “social persuasion”, and taking into consideration “physiological and emotional states” (A. E. Bandura, Citation1995, pp. 3–5).

Table 2. Summary of study groupings.

Self-management interventions were explicitly reported in three studies that focused on the personal management of different aspects of chronic conditions done individually. Seven studies incorporated the use of technology into their treatment. This was either through delivering therapy using a digital means or supplementing face to face or group treatment with technology for further training. The five remaining studies either mentioned non-recurring approaches or frameworks or included models or programs that only appeared once.

Outcome measurement tools used to measure confidence or self-efficacy

All included studies reported, or in the case of protocols planned to use, an outcome measure related to confidence or self-efficacy. Twenty included studies reported quantitative measures to evaluate confidence/self-efficacy in their studies (n = 20, 76.9%). Quantitative measures included standardized assessments composed of scales or questionnaires or study specific produced measures. A total of twelve quantitative outcome measurement tools were reported with five repeated tools amongst included studies. The mostly widely used outcome measure was, the ‘Stoke Self-Efficacy Questionnaire’ (Jones et al., Citation2008). One study created an outcome measurement tool specifically for their study. The remaining studies (n = 6, 23%) used qualitative interviews or self-reports to explore changes in confidence/self-efficacy. Only four out of the eleven studies on people with aphasia reported the use of an aphasia-specific outcome measure to measure confidence, the Communication Confidence Rating Scale for Aphasia. A summary of quantitative confidence/self-efficacy related outcome measures is illustrated in .

Table 3. Quantitative confidence/self-efficacy outcome measures reported.

Summary of included studies categorized based on intervention

The included studies were previously allocated to one of five categories based on self-reported treatment approach/modality. Below is a narrative synthesis for each category.

Impairment-based/symptom-focused treatments

Impairment-based or symptom-focused treatments were used in four studies where the main goal of their treatment was remediating a specific skill or improving effects of stroke, with measurement of confidence as a secondary outcome. Treatment was often presented within a specified framework that had hierarchy of tasks and cues. Interventions reported were a constellation of therapies such as interventions focusing on cognitive, interpersonal, and functional skills (Dignam et al., Citation2015; Young et al., Citation2013), with various modes of delivery such as computer-based and group therapy (Dignam et al., Citation2015; Rodriguez et al., Citation2013). The utilization of trained caregivers or employed visitors to support therapy implementation was also reported (Grasso et al., Citation2019). Although these studies followed a framework for implementation, there was still a level of personalization of therapy in terms of skill levels and reflecting on personal situations that added an element of individualization to the interventions. Studies also reported the implementation of an “intensive therapy” (n = 2; Dignam et al., Citation2015; Rodriguez et al., Citation2013). These studies related intensity to the amount of therapy hours the participants were receiving during the interventions applied in their studies, which was on average at least 2 hours of therapy a day for the duration of their intervention which ranged from 2–16 weeks.

Self-efficacy (SE)

Self-efficacy (SE) was reported in seven studies that built their therapy on concepts of SE. The concept of self-efficacy was frequently used as an approach to self-managed therapy programs (Jones et al., Citation2016, Citation2009; Lo et al., Citation2019, Citation2021). Workbooks were a common resource used to map goals, keep personalized records, and provide problem-solving strategies (Adamit et al., Citation2023; Hawley et al., Citation2022; Jones et al., Citation2016, Citation2009; Lo et al., Citation2019; Smith et al., Citation2023). Banudra’s principles for self-efficacy (A. Bandura, Citation1977) were mentioned as the basis for four studies (Adamit et al., Citation2023; Jones et al., Citation2016, Citation2009; Lo et al., Citation2019).

Overall, the included studies that had an element of self-efficacy embedded within their therapy approaches, used SE concepts to promote self-awareness and increase ownership to allow for self-management. This was mainly accomplished by providing knowledge and strategies used in similar situations prior to identifying the individual’s goals (Jones et al., Citation2016, Citation2009). Once a goal is identified, a personalised action plan is set to achieve this goal (Adamit et al., Citation2023; Lo et al., Citation2019; Osei et al., Citation2023). The progress is determined through self-reflection and may be supplemented with feedback in a group context. Group feedback allows input and suggestions from other individuals facing similar issues and sharing common goals. When workbooks are used, there usually is an explanation of the process beforehand and support available when needed throughout.

Self-management

Three studies based their interventions on self-management. Self-management is defined as “an individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences, and life style changes inherent with living with a chronic disease” (Barlow et al., Citation2002). Two studies approached the ability to apply self-management techniques as a skill. The study interventions aimed to build and reinforce behaviours that will facilitate the skill of self-management. They also provided supporting self-evaluation components to their interventions to reinforce the use of self-management for personal, pre-set goals (Kendall et al., Citation2007; McKenna et al., Citation2015). The third study focused on providing a platform for post stroke-care with access to video material and/or healthcare providers’ consultation when needed (Lo et al., Citation2023).

Technology incorporated

Seven studies incorporated the use of technology as a central feature of their treatment. This was either through presenting therapy stimuli using a computer, or using a computer as a means to provide therapy (videoconferencing), or utilizing a digital means of technology (e.g., iPad application) to supplement face-to-face therapy sessions. Some studies compared computer-based interventions to in-person therapy and noted the importance of human interaction and socialization despite therapy gains seen after the use of technology (Meltzer et al., Citation2018). A pre-treatment training to introduce and prepare participants for technology use was reported (Caute et al., Citation2019; Cherney & Halper, Citation2008). Technology allowed users to personalize aspects of their training stimuli and access to training material was usually not confined to therapy sessions (Amaya et al., Citation2018; Cherney & Halper, Citation2008; Palmer et al., Citation2013; Wentink et al., Citation2016). During the delivery of technology-based therapy, if not delivering therapy through tele-practice, therapists’ role was to monitor and provide support when needed.

Non-recurring studies

An array of therapy approaches was reported in the five remaining studies. This group contained several underrepresented studies with therapy approaches that did not reoccur more than once in the included studies such as community-based clubs (Lesser & Watt, Citation1978), drama therapy (Cherney et al., Citation2011) and motivational interviewing (Gual et al., Citation2020). Speech and language specific studies in this group focused on psychosocial skills that assist in the facilitation of communication such as confidence and adaptive strategies for people living with aphasia and communication difficulties (Horne et al., Citation2019; Ryan et al., Citation2017). Most studies had three main stages to their interventions: an introduction/acquisition stage, an application/training stage, and an adaptation/generalization stage. Some studies had a hierarchal manner of addressing self-views and highlighting strengths to achieve a sense self-perceived belief in ability to apply change (Gual et al., Citation2020).

Within this review, in addition to studies being allocated to the specific groups, they were also grouped based on their interest in confidence/self-efficacy. Only three studies had interventions that directly addressed confidence/self-efficacy in their intervention (Horne et al., Citation2019; Jones et al., Citation2009; Osei et al., Citation2023), five studies built their interventions based off concepts of self-efficacy and the remaining 18 studies measured self-efficacy or confidence as a secondary outcome of intervention. Specific intervention components were also collated and the degrees of overlap between study intervention elements are illustrated in

Table 4. Components of study interventions.

Overall outcome results

As for the overall outcomes related to confidence/SE, out of the twenty-one intervention studies (the review contains five study protocols with no outcome data) all but two intervention studies reported an improvement in confidence/SE outcome measurements. The other two intervention studies reported no changes in confidence/self-efficacy levels/scores (Kendall et al., Citation2007; Wentink et al., Citation2016).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review exploring the rehabilitation of confidence in stroke survivors. This review aimed to gain a better understanding of the type of therapies implemented in rehabilitation that could affect confidence/self-efficacy and to identify outcome measurements that have been used. Due to the variability of studies found in the review’s outcome results, the seemingly most feasible approach was to group studies based on authors self-reports. Below is a discussion of different aspects within the review:

Overlap of intervention characteristics

Results revealed a range of reported approaches with increasing numbers of studies mentioning “confidence” over the years. Although different theories were reported to be underpinning therapeutic approaches, there were varying degrees of overlap in intervention characteristics between all included studies (.). These overlapping characteristics include underpinning theories, treatment approaches, therapy supplements, and delivery modes. The overlap was mostly seen in the elements of intervention structure, such as therapy delivery mode (i.e., group or individual sessions), therapy setting (i.e., in-person or virtual) and the use of workbooks or logs to support therapy concepts and keep track of performance.

Implementation of the ICF framework within interventions

Although the included studies varied in the level of description of interventions, a pattern of incorporating an ICF framework was noticed. Most included studies took into account the levels of interaction of the bio-psycho-social aspects of an individual while undertaking therapy. There was an overall emphasis on working towards individualised goals in many of the studies. Some studies even tailored their interventions to maximize the level of support needed in rehabilitation based on individual priorities. The selection of personally relevant goals and self-reflection were common trends that appeared in many interventions.

Aims of interventionss

Most studies had a specific aim for intervention, but it was interesting to see many interventions building skills that might generalize beyond the intended aim of the intervention. When the included studies are viewed based on how they relate to confidence/self-efficacy, three patterns seem to emerge. The first of these are interventions directly aimed towards impacting confidence or self-efficacy, which were a minority of studies. The second pattern was interventions derived from self-efficacy concepts that did not explicitly address confidence or self-efficacy in the intervention. Most studies (18/26, 69%) seem to follow the third pattern where self-efficacy/confidence was measured as a secondary outcome of an intervention.

Representation of confidence/self-efficacy within the studies

Within the included studies, it was evident that the terms “confidence” and “self-efficacy” were both used to represent a psychosocial construct of belief in ability. Bandura’s self-efficacy theory was frequently referred to in many of these studies. Most interventions had a systematic progression where specific behaviours or attitudes were targeted gradually and aspects of self-reflection and taking perspective were introduced to promote skill building. This hierarchal approach towards addressing self-views or behavioural patterns seems to yield a sense of ownership, control and ability to apply change.

Underrepresented intervention approaches

Interestingly, studies with an artistic and creative approach were underrepresented, relative to expectations, in this review. This might be due to the nature of publishing, being a more community accessible news-based article rather an academic article, therefore not well represented in searches conducted on academic search engines.

Confidence/self-efficacy outcome measurement tools

There was an array of reported confidence/self-efficacy outcome measurement tools. The type of quantitative outcome measures used seem to indicate a tendency to use stroke-specific more than general confidence/self-efficacy outcome measurement tools. Despite the recurrent use of stroke-specific measures of confidence/self-efficacy, there was less use of context/skill specific standardised assessments such as reading, communication and performing life activities. This could be due to the nature of the majority of intervention studies included in this review, not focusing on addressing confidence-self-efficacy directly, therefore not interested in using skill-specific measures but rather the overall impact of intervention on general confidence/self-efficacy. In addition, some studies felt the need to produce study-specific outcome measures for confidence/self-efficacy despite the presence of standardized alternatives.

Confidence/self-efficacy and stroke survivors with aphasia

As evidenced by , a number of studies (n = 11) noted the inclusion of stroke survivors with aphasia and took into account the language difficulties people with aphasia might face. Those interventions were either administered by speech and language therapists, who are familiar with different supportive communication strategies and techniques to aid people with aphasia, or reported the implementation of some form of Patient, Carer and Public Involvement (PCPI) or consultation of people with aphasia. PCPI was implemented during the development of interventions and mostly utilised to guide and support the development of workbooks or logs.

Although specific accommodations and adaptations were taken into consideration within the intervention itself and/or external aids used within these studies, only a few used aphasia-specific outcome measurement tools to measure confidence. This may be due to some of these studies taking place before the establishment of an aphasia-specific confidence outcome measure. Also, some stroke-specific outcome measures, such as the Confidence after Stroke Measure for example, are accessible and can be administered to an array to stroke survivors with or without comorbidities such as aphasia.

Review indications and future studies

The points mentioned above further highlight the need for interventions specifically geared towards building confidence and self-efficacy in stroke rehabilitation, especially if that is a personal goal for stroke survivors. It might also suggest that confidence/self-efficacy is a difficult construct to address directly unless it is context specific (i.e., communication confidence) or skill specific (i.e., self-efficacy for self-management). It also shows that confidence/self-efficacy is impacted or even improves as a byproduct of rehabilitation, a sense of doing and working towards something relevant. In fact, the overall outcomes related to confidence/self-efficacy support the contention that most interventions, whether they explicitly targeted confidence/self-efficacy or not, did positively impact confidence/self-efficacy levels. Even if no changes in confidence/self-efficacy were present, there were no reports of a decrease in confidence/self-efficacy levels or scores after any intervention.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review has several strengths, as to our knowledge, this is the first scoping review exploring confidence outcomes in rehabilitation. This review followed the PRISMA-ScR guidelines in order to be as systematic as possible during the search and filtration process. In addition, the term “self-efficacy” was used adjacent to “confidence” to enhance the likelihood of identifying relevant studies as the term ‘self-efficacy” is more commonly seen and sometimes used interchangeably with “confidence”.

Although this review aimed to scope the rehabilitation scene for therapies relevant to confidence, some limitations exist. One is the imposed restriction of including only psychotherapeutic and communication related studies during the result filtering process. This may have led to the overlooking of some studies, although it did increase the focus of the review and a reasonably large number of relevant studies were identified in spite of this restriction.

Additionally, the analysis of intervention descriptions was exclusively based on what the authors reported as the theory/approach for their study intervention and no critical appraisal was conducted. Individual components of the mentioned therapy approaches were not validated for authenticity. However, achieving a therapy validity check would have been difficult given that many studies failed to provide enough detail to complete a “Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR)” like description of their intervention.

Also, subjective interpretations of study allocation are present with this method, despite efforts to unify judgment based on self-reports and provided data. Although was illustrated to acknowledge the possible overlap between studies, due to the lack of cohesion in the field, any grouping approach would arguably be fairly subjective and somewhat arbitrary.

Conclusion

While the literature appears to be vast and varying at first glance, there are degrees of overlap and interaction in deeper levels. This review indicates that there is no single identified rehabilitation therapy approach used to target confidence. Instead, incorporating elements from multiple therapy approaches, in line with the ICF model, allows for the application of an intervention with various skill outcomes. Adding an aspect of self-driven and personalized goals to an intervention appears to lead to positive confidence-related outcomes. There is a pattern of using stroke-specific confidence/self-efficacy outcome measures more than context/skill specific confidence/self-efficacy measurement tools. This scoping review aided in the initial mapping of the existing literature related to confidence in stroke rehabilitation and different types of evidence were identified.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.5 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge their appreciation to Eleanor Marshall, an undergraduate Psychology student at the University of Manchester, for her contribution in re-running the updated search strategy and screening of studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2024.2340804

References

- Adamit, T., Shames, J., & Rand, D. (2023). Functional and Cognitive Occupational Therapy (FaCoT) improves self-efficacy and behavioral–emotional status of individuals with mild stroke; analysis of secondary outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 20(6), 5052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065052

- Amaya, A., Woolf, C., Devane, N., Galliers, J., Talbot, R., Wilson, S., & Marshall, J. (2018). Receiving aphasia intervention in a virtual environment: The participants’ perspective. Aphasiology, 32(5), 538–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2018.1431831

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Babbitt, E. M., & Cherney, L. R. (2010). Communication confidence in persons with aphasia. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 17(3), 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr1703-214

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. E. (1995). Self-efficacy in Changing Societies. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.10.4.313

- Barlow, J., Sturt, J., & Hearnshaw, H. (2002). Self-management interventions for people with chronic conditions in primary care: Examples from arthritis, asthma and diabetes. Health Education Journal, 61(4), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/001789690206100408

- Caute, A., Woolf, C., Wilson, S., Stokes, C., Monnelly, K., Cruice, M., Bacon, K., & Marshall, J. (2019). Technology-enhanced reading therapy for people with aphasia: Findings from a quasirandomized waitlist controlled study. Journal of Speech Language & Hearing Research, 62(12), 4382–4416. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_JSLHR-L-18-0484

- Cherney, L. R., & Halper, A. S. (2008). Novel technology for treating individuals with aphasia and concomitant cognitive deficits. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 15(6), 542–554. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr1506-542

- Cherney, L. R., Oehring, A. K., Whipple, K., & Rubenstein, T. (2011). “Waiting on the words”: Procedures and outcomes of a drama class for individuals with aphasia. Seminars in Speech & Language, 32(3), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1286177

- Chung, C. S., Pollock, A., Campbell, T., Durward, B. R., & Hagen, S. (2013). Cognitive rehabilitation for executive dysfunction in adults with stroke or other adult non‐progressive acquired brain damage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008391.pub2

- Daudt, H. M. L., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s Framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

- Dignam, J., Copl, D., McKinnon, E., Burfein, P., O’Brien, K., Farrell, A., & Rodriguez, A. D. (2015). Intensive versus distributed aphasia therapy: A nonrandomized, parallel-group, dosage-controlled study. Stroke, 46(8), 2206–2211. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009522

- Flowers, H. L., Skoretz, S. A., Silver, F. L., Rochon, E., Fang, J., Flamand-Roze, C., & Martino, R. (2016). Poststroke aphasia frequency, recovery, and outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 97(12), 2188–2201. e2188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.03.006

- Grasso, S. M., Shuster, K. M., & Henry, M. L. (2019). Comparing the effects of clinician and caregiver-administered lexical retrieval training for progressive anomia. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(6), 866. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2017.1339358

- Gual, N., Perez, L. M., Castellano-Tejedor, C., Lusilla-Palacios, P., Castro, J., Soto-Bagaria, L., Coll-Planas, L., Roque, M., Vena, A. B., Fontecha, B., Santiago, J. M., Lexell, E. M., Chiatti, C., Iwarsson, S., & Inzitari, M. (2020). IMAGINE study protocol of a clinical trial: A multi-center, investigator-blinded, randomized, 36-month, parallel-group to compare the effectiveness of motivational interview in rehabilitation of older stroke survivors. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 321. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01694-6

- Hawley, L., Morey, C., Sevigny, M., Ketchum, J., Simpson, G., Harrison-Felix, C., & Tefertiller, C. (2022). Enhancing self-advocacy after traumatic brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 37(2), 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000689

- Horne, J. (2016). Measuring Confidence After Stroke [ Doctoral dissertation. University of Nottingham].

- Horne, J. C., Hooban, K. E., Lincoln, N. B., & Logan, P. A. (2019). Regaining Confidence after Stroke (RCAS): A feasibility randomised controlled trial (RCT). Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0480-z

- Jahan, A., & Ellibidy, A. (2017). A review of conceptual models for rehabilitation research and practice. Journal of Rehabilitation Sciences, 2(2), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.rs.20170202.14

- Jones, F., Gage, H., Drummond, A., Bhalla, A., Grant, R., Lennon, S., McKevitt, C., Riazi, A., & Liston, M. (2016). Feasibility study of an integrated stroke self-management programme: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 6(1), e008900. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008900

- Jones, F., Mandy, A., & Partridge, C. (2009). Changing self-efficacy in individuals following a first time stroke: Preliminary study of a novel self-management intervention. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23(6), 522–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508101749

- Jones, F., Partridge, C., & Reid, F. (2008). The stroke self-efficacy questionnaire: Measuring individual confidence in functional performance after stroke. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(7b), 244–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02333.x

- Jones, F., & Riazi, A. (2011). Self-efficacy and self-management after stroke: A systematic review. Disability & Rehabilitation, 33(10), 797–810. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2010.511415

- Kendall, E., Catalano, T., Kuipers, P., Posner, N., Buys, N., & Charker, J. (2007). Recovery following stroke: The role of self-management education. Social Science & Medicine, 64(3), 735–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.012

- Laures-Gore, J. S., Dotson, V. M., & Belagaje, S. (2020). Depression in poststroke aphasia. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(4), 1798–1810. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00040

- Lesser, R., & Watt, M. (1978). Untrained community help in the rehabilitation of stroke sufferers with language disorder. British Medical Journal, 2(6144), 1045–1048. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.6144.1045

- Lo, S. H. S., Chau, J. P. C., Chang, A. M., Choi, K. C., Wong, R. Y. M., & Kwan, J. C. Y. (2019). Coaching Ongoing Momentum Building On stroKe rEcovery journeY (‘COMBO-KEY’): A randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open, 9(4), e027936. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027936

- Lo, S. H. S., Chau, J. P. C., Choi, K. C., Shum, E. W. C., Yeung, J. H. M., & Li, S. H. (2021). Promoting community reintegration using narratives and skills building for young adults with stroke: A protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Neurology, 21(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-020-02015-5

- Lo, S. H. S., Chau, J. P. C., Lau, A. Y. L., Choi, K. C., Shum, E. W. C., Lee, V. W. Y., Hung, S. S., Mok, V. C. T., Siow, E. K. C., Ching, J. Y. L., Mirchandani, K., & Lam, S. K. Y. (2023). Virtual multidisciplinary stroke care clinic for community-dwelling stroke survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Stroke, 54(10), 2482–2490. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.123.043605

- Lorig, K. R., Ritter, P., Stewart, A. L., Sobel, D. S., Brown, B. W., Jr., Bandura, A., Gonzalez, V. M., Laurent, D. D., & Holman, H. R. (2001). Chronic Disease Self-Management Program: 2-Year Health Status and Health Care Utilization Outcomes. Medical Care, 1217–1223. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008

- McKenna, S., Jones, F., Glenfield, P., & Lennon, S. (2015). Bridges self-management program for people with stroke in the community: A feasibility randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Stroke, 10(5), 697–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijs.12195

- Meltzer, J. A., Baird, A. J., Steele, R. D., & Harvey, S. J. (2018). Computer-based treatment of poststroke language disorders: A non-inferiority study of telerehabilitation compared to in-person service delivery. Aphasiology, 32(3), 290–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2017.1355440

- Osei, S. K. J., Adomako–Bempah, E., Yeboah, A. A., Owiredu, L. A., Ohene, L. A., & Leung, D. Y. (2023). Nurse-led telerehabilitation intervention to improve stroke efficacy: Protocol for a pilot randomized feasibility trial. Plos one, 18(6), e0280973. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280973

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Palmer, R., Enderby, P., & Paterson, G. (2013). Using computers to enable self-management of aphasia therapy exercises for word finding: The patient and carer perspective. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 48(5), 508–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12024

- Pollock, A., St George, B., Fenton, M., & Firkins, L. (2014). Top 10 research priorities relating to life after stroke–consensus from stroke survivors, caregivers, and health professionals. International Journal of Stroke, 9(3), 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00942

- Poulin, V., Korner-Bitensky, N., Bherer, L., Lussier, M., & Dawson, D. R. (2017). Comparison of Two Cognitive Interventions for Adults Experiencing Executive Dysfunction Post-stroke: A Pilot Study. Disability and Rehabilitation: An International, Multidisciplinary Journal, 39(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3109/2F09/6382/88.2015.1123303

- Poulsen, A. A., Ziviani, J., Kotaniemi, K., & Law, M. (2014). ‘I think i can’: Measuring confidence in goal pursuit. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 77(2), 64–66. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802214X13916969447074

- Robertson, I. (2021). How Confidence Works: The New Science of Self-belief, Why Some People Learn It and Others Don’t. Random House.

- Rodriguez, A. D., Worrall, L., Brown, K., Grohn, B., McKinnon, E., Pearson, C., Van Hees, S., Roxbury, T., Cornwell, P., MacDonald, A., Angwin, A., Cardell, E., Davidson, B., & Copl, D. A. (2013). Aphasia LIFT: Exploratory Investigation of an Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Programme. Aphasiology, 27(11), 1339–1361. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.825759

- Rudd, A. G., Bowen, A., Young, G., & James, M. A. (2017). National clinical guideline for stroke: 2016. Clinical Medicine. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.17-2-154

- Ryan, B., Hudson, K., Worrall, L., Simmons-Mackie, N., Thomas, E., Finch, E., Clark, K., & Lethlean, J. (2017). The aphasia action, success, and knowledge programme: Results from an Australian phase I trial of a speech-pathology-led intervention for people with aphasia early post stroke. Brain Impairment, 18(3), 284–298. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2017.5

- Smith, S., Parkinson, J., Caitens, T., Sanders, A., Murphy, L., & Hamilton, K. (2023). Promoting adherence to stroke secondary prevention behaviours by imparting behaviour change skills: Protocol for a single-arm pilot trial of living well after stroke. BMJ Open, 13(1), e068003. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068003

- Stroke Association. (2021). The Stroke Priority Setting Partnership. Retrieved March 16, 2022, from https://www.stroke.org.uk/sites/default/files/research/stroke_priority_setting_partnership_full_report.pdf

- Townsend, S. (2009). Regaining confidence after stroke course V2. Shropshire: [Audio Visual CD].

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., andStraus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Wentink, M. M., Berger, M. A., de Kloet, A. J., Meesters, J., Band, G. P., Wolterbeek, R., Goossens, P. H., Vliel, V., & P, T. (2016). The effects of an 8-week computer-based brain training programme on cognitive functioning, qol and self-efficacy after stroke. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 26(5), 847–865. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2016.1162175

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2001). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42407/9241545429.pdf?sequence=1

- World Stroke Organization. (2022). Learn about stroke. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://www.world-stroke.org/world-stroke-day-campaign/why-stroke-matters/learn-about-stroke

- Wright, F., Wu, S., Chun, H.-Y.-Y., & Mead, G. (2017). Factors associated with poststroke anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke Research & Treatment, 2017, 2124743. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2124743

- Young, A., Gomersall, T., Bowen, A., & Investigators, A. C. T. N. (2013). trial participants’ experiences of early enhanced speech and language therapy after stroke compared with employed visitor support: A qualitative study nested within a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 27(2), 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215512450042

- Zanella, C., Laures-Gore, J., Dotson, V. M., & Belagaje, S. R. (2023). Incidence of post-stroke depression symptoms and potential risk factors in adults with aphasia in a comprehensive stroke center. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 30(5), 448–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2022.2070363