Abstract

Background: Many clinicians believe that preparedness before surgery for possible post-surgery side effects reduces the level of bother experienced from urinary incontinence and decreased sexual health after surgery. There are no published studies evaluating this belief. Therefore, we aimed to study the level of preparedness before radical prostatectomy and the level of bother experienced from urinary incontinence and decreased sexual health after surgery.

Material and methods: We prospectively collected data from a non-selected group of men undergoing radical prostatectomy in 14 centers between 2008 and 2011. Before surgery, we asked about preparedness for surgery-induced urinary problems and decreased sexual health. One year after surgery, we asked about bother caused by urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction. As a measure of the association between preparedness and bothersomeness we modeled odds ratios (ORs) by means of logistic regression.

Results: Altogether 1372 men had urinary incontinence one year after surgery as well as had no urinary leakage or a small urinary dribble before surgery. Among these men, low preparedness was associated with bother resulting from urinary incontinence [OR 2.84; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.59–5.10]. In a separate analysis of 1657 men we found a strong association between preparedness for decreased sexual health and experiencing bother from erectile dysfunction (OR 5.92; 95% CI 3.32–10.55).

Conclusion: In this large-sized prospective trial, we found that preparedness before surgery for urinary problems or sexual side effects decreases bother from urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction one year after surgery.

‘All things are ready, if our mind be so’, wrote Shakespeare in Henry V [Citation1]. Translated into the cancer survivorship field this wisdom may indicate that preparing patients for surgery-induced side effects lowers the extent to which a side effect bothers the cancer survivor. Not surprisingly, many clinicians believe that the better the preparedness the lower the level of bother. There are, as yet, no studies to support this belief. In particular, we know little about the relationships between level of preparedness for urinary problems or decreased sexual health and being bothered by urinary incontinence or erectile dysfunction, respectively.

With a literate population willing to contribute to research by completing extensive questionnaires, Sweden offers favorable conditions for prospective trials. Taking advantage of this situation, urologists in 14 centers, prospectively attempted to collect information from all men undergoing radical prostatectomy. They were able to form study groups without having to face any selection-induced problems. The data collection included clinical record forms (CRFs) as well as outcomes reported by patients in the extensive questionnaires they completed both before and after surgery. In this setting, we studied the association between preparedness before surgery and bother one year after surgery as related to urinary incontinence and/or erectile dysfunction.

Material and methods

Overview

The study population consisted of all men who participated in the open, prospective, non-randomized trial LAParoscopic Prostatectomy Robot Open (LAPPRO) focusing on the pros and cons of open retropubic radical prostatectomy (RRP) and robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (RALP). Patients diagnosed with prostate cancer and planned for radical prostatectomy were recruited from 14 Swedish departments of urology between 1 September 2008 and 7 November 2011. Many details have been given previously [Citation2–5].

Patients

We have data on virtually all men undergoing radical prostatectomy at the 14 departments during the recruitment period. We studied all men who did not have urinary leakage or a very small urinary leakage, i.e. urinary dribble, before surgery but who were incontinent one year after surgery and answered whether or not they were bothered from urinary problems. We also studied all men who did not have erectile dysfunction before surgery but who reported having erectile dysfunction one year after surgery and answered whether or not they were bothered from decreased sexual health.

Data collection

CRFs were filled out by nurses and surgeons before, during and at 1.5–3 months, 12 and 24 months after surgery. Patient-reported data were collected before surgery and at 3, 12 and 24 months after surgery via mailed questionnaires. All CRFs and questionnaires were administered and collected by the trial secretariat, which monitored the centers regularly [Citation2]. The patient questionnaires were developed for LAPPRO and employed a clinimetric atomized approach as in 26 previous questionnaires developed by our group, including one randomized controlled trial evaluating the effects of radical prostatectomy [Citation6–11]. The questionnaires were based on our previously developed questionnaires for similar patient groups [Citation6,Citation11]. However, some questions were modified and new questions were added, including questions on preparedness for side effects assessed in the current study. Nevertheless, the questionnaires were rigorously face-validated clinimetrically and further tested in a pilot study to ensure that they were understood correctly by men with a recent diagnosis of prostate cancer [Citation2]. Furthermore, the EuroQol 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) [Citation12] and a modified version of the five-item International Index of Erectile Function International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) [Citation13] were added to the questionnaires to calculate quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and comparison purposes, respectively.

Before surgery, we asked ‘How prepared do you feel you are to live with possible urinary side effects after the operation?’ and ‘How prepared do you feel you are to live with possible sexual side effects after the operation?’ with response options ‘Completely prepared’, ‘Very much prepared’, ‘Somewhat prepared’, and ‘Not at all prepared’. When the questions were used as outcomes they were dichotomized into yes for response options ‘Completely prepared’, ‘Very much prepared’ and no for the response options ‘Somewhat prepared’, and ‘Not at all prepared’.

Questions concerning urinary incontinence and sexual health were identical before and after surgery.

We asked, ‘During the past months, how much urine have you leaked during the day?’ with response options ‘Not relevant, I do not leak urine during the day’, ‘A little, ‘Moderate’ and ‘Very much’. The same question was asked also after surgery. In one question we referred to morning erection and in another to erection in relation to sexual activity. We asked, ‘During the previous month,…, how stiff was your penis?’ with response options ‘Not relevant, I have not had a morning erection’, (or ‘Not relevant, I have not been sexually active’), ‘My penis has never been sufficiently stiff for intercourse’, ‘My penis has been sufficiently stiff for intercourse on fewer than half of the occasions’, ‘My penis has been sufficiently stiff for intercourse on more than half of the occasions’, and ‘My penis has always been sufficiently stiff for intercourse’. The man was considered potent if the response to any of these questions was ‘My penis has been sufficiently stiff for intercourse on more than half of the occasions’. If this response was not used for any question, the man was classified as impotent.

Patient-reported bother from urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction, and negative impact on self-esteem were outcomes in the part of the study that addressed consequences of patient-reported preparedness for urinary problems and sexual side effects. One year after surgery we asked two questions: 1) ‘If you have had urinary leakage during the day during the previous month and you were to spend the rest of your life with it, what do you think of that?’ with response options ‘Not applicable, I have no problems with urinary leakage during the day’, ‘It would not bother me at all’, ‘It would bother me slightly’, ‘It would bother me moderately’, and ‘It would bother me very much’ and 2) ‘If your erection has become worse compared with previously and this condition were to continue for the rest of your life, what do you think of that?’ with response options ‘Not applicable, my erection has not become worse’, ‘Not applicable, I have not had an erection’, ‘It would not bother me at all’, ‘It would bother me slightly’, ‘It would bother me moderately’, and ‘It would bother me very much’. Each of these responses was dichotomized into high bother for a response of at least ‘Moderately’, otherwise low bother. We also asked, ‘If your erection has worsened or disappeared, has this affected your self-esteem?’ with response options ‘Not applicable, my erection has not worsened’, ‘Not applicable, I have not had an erection, ‘No, this has not affected my self-esteem at all’, ‘Yes, this has affected my self-esteem slightly’, ‘Yes, this has affected my self-esteem moderately’, and ‘Yes, this has affected my self-esteem very much’. The responses were dichotomized into high negative impact on self-esteem for a response of at least ‘Moderately’, otherwise low negative impact on self-esteem. The outcomes were dichotomized to facilitate interpretation.

Statistical analysis

Missing data were handled by creating 20 imputation-completed datasets using multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE). For calculations relating to predictors of preparedness for urinary problems and sexual side effects, we considered only those men who were preoperatively continent, or potent, respectively. To get groups of men with optimal contrast before and after surgery, for each outcome we considered only subgroups of men who were continent or potent before surgery, and were incontinent or impotent one year after surgery, respectively. For each outcome, we further restricted all calculations to patients without missing information on the outcome variable.

As measures of effect, univariable relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using log-binomial regression as odds ratios (ORs) might overestimate the corresponding RRs. In addition, because of convergence issues when performing multivariable log-binomial regression, logistic regression was performed to calculate crude and adjusted ORs with 95% CIs. All presented RRs and ORs are pooled estimates derived from the multiple imputations.

An automated selection procedure was used for identification of potential predictors for patient preparedness for urinary problems and sexual side effects. The same procedure was used for identification of confounders for the association of preparedness for urinary problems and bother from urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction, and impact on self-esteem. For each outcome, we created separate logistic regression models through backward stepwise selection for each of the 20 imputation-completed datasets, and variables that remained in at least half of the 20 models were then included in a final pooled model [Citation14]. The selection criterion was minimum Akaike information criterion for predictors, while the more inclusive criterion p < 0.20 was used for confounders to avoid under adjustment.

Unless otherwise specified, a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was performed in Stata, version 11.2 (StataCorp, TX, USA) and R, version 3.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), using the mice package.

Results

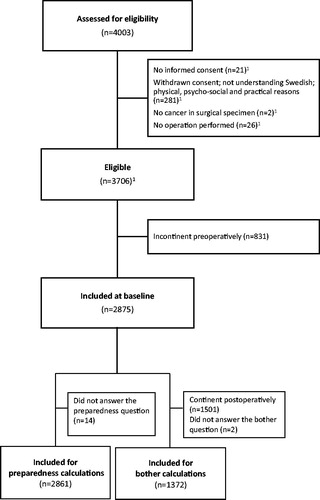

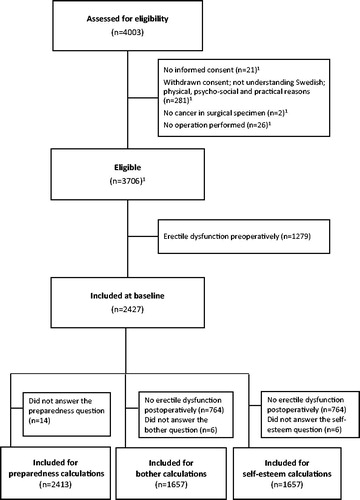

A total of 2875 patients were included at baseline for the analysis regarding urinary incontinence (, ). Regarding the analysis for erectile dysfunction 2427 patients were included at baseline (, ).

Figure 1. (a) Flowchart of the study populations regarding predictors for preparedness for urinary problems and the association between preparedness for urinary problems and risk of bother from urinary incontinence. (b) Flowchart of the study populations regarding predictors for preparedness for sexual side effects and the association between preparedness for sexual side effects and risk of bother from erectile dysfunction. 1Numbers may not add as the same individual may have fulfilled more than one exclusion criterion.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of all men selected for analysis regarding urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction, respectively.

Urinary incontinence, preparedness

shows predictors of patient preparedness before surgery for urinary problems after radical prostatectomy, studied one by one as well as in a multivariable model. Variables to the final multivariable model were selected by backward selection. CIs not overlapping 1.0 in the multivariable model we obtained for age, having a partner, preparedness for the prostate cancer diagnosis and being confident of cure.

Table 2. Predictors of patient preparedness before surgery for urinary problems after radical prostatectomy.

Urinary incontinence, bother

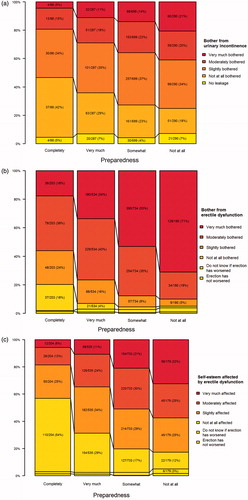

shows strong association between not being prepared for urinary problems and being bothered by urinary incontinence. In the multivariable model, being ‘Completely’ prepared as reference (OR 1.00) we obtained OR 1.68 (CI 0.93–3.04) for being ‘Very much’ prepared. The corresponding figures for being ‘Somewhat’ prepared OR 2.30 (CI 1.32–4.00) and for ‘Not at all’ prepared OR 2.84 (CI 1.59–5.10). presents the absolute numbers concerning degree of preparedness and bother from urinary incontinence. The results were not modified by degree of urinary incontinence.

Figure 2. (a) Bother from urinary incontinence by degree of preparedness in continent men who became incontinent after radical prostatectomy. (b) Bother from erectile dysfunction by degree of preparedness in potent men who became impotent after radical prostatectomy. (c) Negative impact on self-esteem due to erectile dysfunction by degree of preparedness in potent men who became impotent after radical prostatectomy.

Table 3. The association between patient preparedness for urinary problems and bother from urinary incontinence in daytime after radical prostatectomy.

Erectile dysfunction, preparedness

shows predictors of patient preparedness before surgery for decreased sexual health after radical prostatectomy, studied one by one as well as in a multivariable model. Variables in the final multivariable model were selected by backward selection. CIs not overlapping 1.0 in the multivariable model we obtained for age, country of birth, anxiety, preparedness for the prostate cancer diagnosis, being confident of cure and being planned for nerve-sparing surgery.

Table 4. Predictors of patient preparedness for sexual side effects after radical prostatectomy.

Erectile dysfunction, bother

shows a strong association between not being prepared for decreased sexual health and being bothered by erectile dysfunction. In the multivariable model, being ‘Completely’ prepared as reference (OR 1.00) we obtained OR 2.41 (CI 1.70–3.42) for being ‘Very much’ prepared. The corresponding figures for being ‘Somewhat’ prepared OR 4.86 (CI 3.37–7.00) and for ‘Not at all’ prepared OR 5.92 (CI 3.32–10.55). presents the absolute numbers for concerning degree of preparedness and bother from erectile dysfunction. The results were not modified by degree of erectile dysfunction.

Table 5. The association between patient preparedness for sexual side effects and level of bother from erectile dysfunction in men with erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy.

Erectile dysfunction, self-esteem

shows a strong association between not being prepared for decreased sexual health and negative self-esteem because of erectile dysfunction. presents the absolute numbers concerning degree of preparedness and negative impact on self-esteem. The results were not modified by degree of erectile dysfunction.

Table 6. The association between patient preparedness for sexual side effects and impact on self-esteem because of erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy.

Complete case analyses showed somewhat lower ORs concerning the effects of being prepared on bother from urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction, respectively, and negative impact on self-esteem (data not shown).

Discussion

In this population-based study of patients undergoing radical prostatectomy with preoperatively assessed preparedness for side effects and postoperatively assessed bother from such event, symptomatic patients with low preparedness for urinary problems and sexual side effects had an increased risk of bother from urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction one year after radical prostatectomy. Moreover, low preparedness for sexual side effects was associated with an increased risk of negative impact on self-esteem due to erectile dysfunction after surgery.

Patients’ preparedness has been investigated in other surgical contexts, e.g. breast cancer [Citation15] and orthopedic surgery [Citation16]. However, in a PubMed search in February 2015, we found no articles investigating the relation between preparedness and bother concerning urinary problems and decreased sexual health. Data in a retrospective setting from our group indicate that preoperative information about possible side effects after radical prostatectomy may decrease bother by erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence (Dahlstrand et al., pers. comm.). Several randomized controlled trials [Citation17–22] investigated the effect of psychosocial intervention after treatment for prostate cancer on urinary bother [Citation17–22], sexual bother [Citation17–19,Citation22], or sexual satisfaction [Citation20,Citation21,Citation23]. Psychosocial intervention was associated with less sexual bother or higher sexual satisfaction in all but one study [Citation17,Citation18,Citation20–23]. Only one study showed an effect of psychosocial intervention on urinary bother [Citation18]. Nevertheless, these studies are not comparable to the current study because of differences in study design and methodology. One might speculate that low preparedness for urinary and sexual problems increases the risk of bother from urinary incontinence after surgery through absence of the possibility of anticipatory coping, i.e. coping that precedes the potential side effect. Awareness of a negative event may increase the feeling of being in control and may also enable better mental preparation and adjustment to the event [Citation24]. So, although few researchers have investigated the extent to which preparedness influences bother from symptoms that occur after radical prostatectomy, available data support our finding.

Possibly the communication that takes place between the professional caregiver and the person to be operated on will have a significant impact on the patient’s preparedness. We have no information regarding the nature or quality of this communication in our study. However, an indirect measure of the importance of this patient-physician communication is the finding that men who were planned for nerve-sparing surgery, and were so informed by their surgeon prior to the operation, were less well prepared than other men to deal with decreased sexual health. In addition, we do not know if the men include psychological aspects or practical problems in their thinking about the concept of preparation along with future urinary tract problems or problems with sexual health. However, we do have information about socio-demographic factors and we have found that age, having a partner, preparedness for the diagnosis, and belief in being cured are of primary importance. We have not found any previous articles investigating predictors of preparedness before radical prostatectomy; thus, at this point more data are needed before we can say more about exactly what forms of preparedness work best.

Answering a questionnaire that you are bothered by a symptom may be regarded as a rather abstract exercise. We do not know on the basis of these answers what actually bothers the patient in his daily life. On the basis of a study by Sunny et al., we know that ability to have an erection can affect the quality of the marriage and we may speculate that this in turn affects the man’s self-esteem [Citation11]. Galbraith et al. documented the co-variation between health-related quality of life and marital satisfaction [Citation25]. Nevertheless, we need much more data before we can tell what the bother arising from urinary incontinence and decreased sexual health means in the man’s daily life.

Apart from the large size of the study group, having information retrieved before surgery on preparedness and after surgery about bother is the major strength of our study. Moreover, we had a participation rate of about 90% and information was collected by a neutral third party, avoiding I-want-to-please-my-surgeon induced bias. In order not to dilute the results we excluded men also having urinary dribble before surgery. That is, this criterion for continence is much more stringent that if one uses, for example pads. A similar philosophy was employed concerning sexual health. The major weakness is that the term preparedness and bother are conceptually unclear; we need much more information before we can tell what the associations reflect in more detail.

In the absence of a scientifically sound foundation, many clinics follow the principle that a well prepared patient will be better able to deal with any surgery-induced side effects that may result. However, other clinics follow the principle that one should let sleeping dogs lie, which means in practice that we should not add to the patient’s concerns about the surgery itself, but should wait until side effects do appear and deal with them then.

Imputation may increase precision, but may, if the values are not missing at random, introduce a bias. The differences we found between complete case analyses and the analyses based on imputed data sets did not change our interpretation of the data.

The literature on cancer patients’ information needs tells us that the majority of patients want information about treatment side effects [Citation26,Citation27]. Finding the best balance between providing too much information and providing too little is difficult and can only be accomplished on the basis of substantial clinical experience and intuition. Possibly our finding showing an association between preparedness and bothersomeness after surgery may increase efforts to identify those men who want to know more about most if not all possible side effects and want the best possible communication with health care. Possibly means for communication can be better adapted to ones needs and personality characteristics. Possibly healthcare professionals can do more than today in guiding towards contacting peer groups or in finding relevant information on the internet.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Mark S. Litwin for valuable advice. We also thank the following foundations for support: Swedish Cancer Foundation [2010/593], Region Västra Götaland, Sahlgrenska University Hospital [ALF grants 138751 and 146201], agreement concerning research and education of doctors, Swedish Research Council, Mrs Mary von Sydow Foundation, and Anna and Edvin Berger foundation. We also thank Dr Sven Grundtman for including patients in the trial. We thank all prostate cancer survivors who provided information.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Shakespeare W. Henry V. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company; 1935.

- Thorsteinsdottir T, Stranne J, Carlsson S, et al. LAPPRO: a prospective multicentre comparative study of robot-assisted laparoscopic and retropubic radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2011;45:102–12.

- Persson J, Wilderang U, Jiborn T, et al. Interobserver variability in the pathological assessment of radical prostatectomy specimens: findings of the laparoscopic prostatectomy robot open (LAPPRO) study. Scand J Urol 2014;48:160–7.

- Haglind E, Carlsson S, Stranne J, et al. Urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction after robotic versus open radical prostatectomy: a prospective, controlled, nonrandomised trial. Eur Urol 2015;68:216–25.

- Steineck G, Bjartell A, Hugosson J, et al. Degree of preservation of the neurovascular bundles during radical prostatectomy and urinary continence 1 year after surgery. Eur Urol 2015;67:559–68.

- Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, et al. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med 2002;347:790–6.

- Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Onelov E, et al. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1175–86.

- Dunberger G, Lind H, Steineck G, et al. Fecal incontinence affecting quality of life and social functioning among long-term gynecological cancer survivors. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2010;20:449–60.

- Steineck G, Hunt H, Adolfsson J. A hierarchical step-model for causation of bias-evaluating cancer treatment with epidemiological methods. Acta Oncol 2006;45:421–9.

- Steineck G, Bergmark K, Henningsohn L, et al. Symptom documentation in cancer survivors as a basis for therapy modifications. Acta Oncol 2002;41:244–52.

- Sunny L, Hopfgarten T, Adolfsson J, et al. Economic conditions and marriage quality of men with prostate cancer. BJU Int 2007;99:1391–7.

- Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996;37:53–72.

- Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, et al. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 1997;49:822–30.

- Wood AM, White IR, Royston P. How should variable selection be performed with multiply imputed data? Stat Med 2008;27:3227–46.

- Manne SL, Topham N, Kirstein L, et al. Attitudes and decisional conflict regarding breast reconstruction among breast cancer patients. Cancer Nurs 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000320.

- Cox J, Cormack C, Prendergast M, et al. Patient and provider experience with a new model of care for primary hip and knee arthroplasties. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs 2016;20:13–27.

- Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS, Eton DT, et al. Improving quality of life in men with prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial of group education interventions. Health Psychol 2003;22:443–52.

- Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, Scipio C, et al. Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African American prostate cancer survivors and their intimate partners. A pilot study of telephone-based coping skills training. Cancer 2007;109:414–24.

- Giesler RB, Given B, Given CW, et al. Improving the quality of life of patients with prostate carcinoma: a randomized trial testing the efficacy of a nurse-driven intervention. Cancer 2005;104: 752–62.

- Canada AL, Neese LE, Sui D, et al. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2005;104:2689–700.

- Schover LR, Canada AL, Yuan Y, et al. A randomized trial of internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer 2012;118: 500–9.

- Weber BA, Roberts BL, Resnick M, et al. The effect of dyadic intervention on self-efficacy, social support, and depression for men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2004;13:47–60.

- Mishel MH, Belyea M, Germino BB, et al. Helping patients with localized prostate carcinoma manage uncertainty and treatment side effects: nurse-delivered psychoeducational intervention over the telephone. Cancer 2002;94:1854–66.

- Anderson EA. Preoperative preparation for cardiac surgery facilitates recovery, reduces psychological distress, and reduces the incidence of acute postoperative hypertension. J Consult Clin Psychol 1987;55:513–20.

- Galbraith ME, Arechiga A, Ramirez J, et al. Prostate cancer survivors' and partners' self-reports of health-related quality of life, treatment symptoms, and marital satisfaction 2.5-5.5 years after treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum 2005;32:E30–41.

- Jenkins V, Fallowfield L, Saul J. Information needs of patients with cancer: results from a large study in UK cancer centres. Br J Cancer 2001;84:48–51.

- Cassileth BR, Zupkis RV, Sutton-Smith K, et al. Information and participation preferences among cancer patients. Ann Intern Med 1980;92:832–6.