?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper nuances the dualism between local councils and local executives and distinguishes distinct patterns of interactions between councillors and executive members based on Anthony King's modes of executive–legislative relations. Several hypotheses explaining council–executive relations were tested using original survey data on Dutch local councillors. The interparty mode (coalition vs opposition) was found to be the most dominant relative to the non-party mode (council vs executive board) and the crossparty mode (policy specialists vs policy specialists). Councillors operate less frequently in the interparty mode when the governing coalition is oversized, and female councillors operate less often in the interparty mode than male councillors. Furthermore, an analysis of councillors shifting between modes suggests that councillors operate in the interparty mode when politically salient issues are at stake, in the non-party mode when the position of the council is at stake, and in the crossparty mode when dealing with technocratic issues.

Introduction

The relations between local councillors and members of the local executive comprise a crucial component of local democracies. Local councillors are the representative link between ordinary people and local government. They are supposed to represent the people and scrutinise the local executive. Responding to a survey question on their most important tasks European councillors mention defining the main goals of the municipality, representing requests and issues emerging from local society and controlling municipal activity (Klok and Denters Citation2013). However, their performance on these tasks is lower than their ambition. This ‘role behaviour deficit’ is particularly high for tasks related to their relations with the executive: defining goals and controlling activity.

This may be due to the widely observed executive dominance over councils. A sample of European councillors that was asked how influential 22 different actors are over local government activities perceived the mayor and the executive board as the most influential actors. They ranked themselves only as the 12th most influential, below the municipality administration, upper levels of government and professional consultants and experts (Plüss and Kübler Citation2013). Mayors too perceive councillors as the least influential in comparison to themselves and executive boards ‘particularly in municipalities with a collective form’ (Navarro et al. Citation2018, 366; cf.; Egner and Heinelt Citation2008; Denters Citation2006). An example of the ‘collective form’ of local government organisation is the Netherlands. Here, a mayor together with a few aldermen form a collegiate body – the executive board – responsible for the executive branch of local government (Mouritzen and Svara Citation2002). Observers of Dutch council–executive relations suggest that executive dominance is caused by the executive’s central position in the early stages of policymaking, exclusive competencies, extensive departmental support and councillors being part-time amateur politicians (Castenmiller, Peters, and Van den Berg Citation2018; Schaap Citation2019, 58–59).

These analyses, however, have treated councils and executive boards as two collective and cohesive institutions that operate independently from each other, thereby ignoring other important political relationships that hide under the label of ‘executive–legislative relations’. In legislative studies, Antony King (Citation1976, 11) has advocated to ‘“think behind” the Montesquieu formula’. Breaking with the ‘two-body image’, King identifies multiple ‘modes’ of executive–legislative relations that describe distinct relationships between various combinations of actors within the executive–legislative arena. This framework has been found useful in making sense of executive–legislative relations in several countries, such as the United Kingdom, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and the Nordic countries (Andeweg Citation1992; Damgaard Citation2000; Müller Citation1993; Russell and Cowley Citation2018; Saalfeld Citation1990).

This literature, however valuable, seems stuck in description and lacks systematically tested explanations as it is difficult to rigorously assess explanations of observed differences because of the ‘small N, many variables’ problem. Furthermore, not yet having been applied to local governments, King’s conceptualisation of executive–legislative relations offers a promising avenue to further our understanding of the relations between local councillors and executive boards. How councillors interact with each other and with members of the executive is of central importance to the performance, legitimacy and accountability of local government. This is especially apparent because local councils are the only directly elected collective body in local government and as such connect citizens to local decision-makers. How councillors operate reveals how they fulfil their representative roles, on which interests they rely during the policy process and how the executive is held to account.

Using King’s framework and the empirical testing ground of local councils in the Netherlands, this study aims to answer the following research question: how often do local councillors operate in the various modes of executive–legislative relations and which factors can explain this? To answer this question the results of original survey data on councillors were analysed. The following section will introduce a conceptualisation of how councillors operate vis-à-vis each other and members of the executive board. Next, the case selection and the research design are explained after which the empirical findings are presented. Following the finding that three modes of executive–legislative relations co-occur in local councils, a second question is addressed: to what degree do councillors specialise in different modes or shift between modes of executive–legislative relations and which factors explain mode shifting? Finally, the findings and implications are discussed highlighting this study’s contribution to improving our understanding of council behaviour, as well as to improving our understanding of executive–legislative relations in general.

Conceptualising relations between councillors and executive members

King’s (Citation1976) seminal article distinguishes between different ‘modes’ of executive-legislative relations, each characterised by a particular interaction pattern and role conception. In each of these interaction patterns, a distinct combinations of councillors and executive members oppose each other. Following Andeweg and Nijzink’s (Citation1995) modification of King’s framework, I distinguish between three main patterns of interaction: (1) the non-party mode, in which members of the council interact with the executive board; (2) the interparty mode, in which councillors (and aldermen) from one party interact with councillors (and aldermen) from another party; and (3) the crossparty mode, in which councillors and aldermen combine to interact based on special non-partisan interests.Footnote1 All three modes describe the relations between councillors and members of the executive board, but each is characterised by a different line of conflict ().

Figure 1. Modes of council–executive relations (cf. Andeweg and Nijzink Citation1995, 154).

The non-party mode

In the non-party mode, councillors act as representatives of the council as a whole on a non-party basis and as a counterweight to the executive board. This mode resembles the classic two-body image. In the Netherlands, local councils are formally the highest administrative organs of municipalities, whereas the mayor and aldermen form a collegial board bearing collective responsibility for the executive functions of local government. Councillors have several instruments available to control the executive board and prevent or sanction abuse of executive powers, such as questions, amendments, committees, etc. (Ashworth and Snape Citation2004; Verhelst and Peters Citation2024).

In the Netherlands, there has been a normative emphasis on councillors operating in the non-party mode since reforms of the local government system in 2002. These reforms intended to transform local governments from a so-called ‘monistic’ to a ‘dualistic’ system, in which the council and executive board have separate powers and responsibilities. Most importantly, membership of the council and the executive board became incompatible, aldermen could no longer act as chairs of council committees, and formal powers and support for councillors were expanded (Denters, Van der Kolk, and Klok Citation2005). The legal requirement for aldermen to combine their office with the councillorship before 2002 represents an extreme case of the interparty mode because it indicates close ties between aldermen and their party’s councillors. The prohibition of this combination in the 2002 reforms represents a shift to the non-party mode, especially when aldermen are recruited from outside the council (or the municipality) (Andeweg and Nijzink Citation1995, 160–61). Since the reforms, councillors have considered their scrutiny task more important than before (De Groot, Denters, and Klok Citation2010).

Dutch mayors do not have a confidence relationship with the council; they are appointed by the national government – followed by the council’s advice – for a six-year term. Although nearly all mayors are party members, they are generally expected to act non-partisan (Karsten, Schaap, and Hendriks Citation2014). Though not representing a presidential model, the independent position of mayors also introduces a degree of separation of powers in Dutch local politics.

The interparty mode

In the interparty mode, local councils do not function as a cohesive institution but as an arena in which councillors (and aldermen) of a party operate as a unified bloc and compete with councillors (and aldermen) from other parties. Across Europe councillors have organised themselves into party groups with strong party unity (Copus and Erlingsson Citation2012; Razin Citation2013; Sweeting Citation2009; Van Vonno Citation2019) and party group behaviour may complicate effective council oversight (Copus Citation2008; Leach and Copus Citation2004). Councillors mention implementing their party programme as one of their top tasks (Klok and Denters Citation2013). For many of them, the party is ‘the only vehicle through which politics can effectively and legitimately be conducted’ (Copus Citation2004, 42).

In the Netherlands, local councillors are elected for a four-year term through a semi-open list system of proportional representation. Virtually all councillors are members of a party group, either from local branches of established national parties or from independent local parties. Dutch local government is an example of parliamentarism, in which aldermen are appointed by a coalition majority in the council and depend on the confidence of the council (Bäck Citation2005). Because parties are the main actors in local government formation (Bäck Citation2003; Debus and Gross Citation2016; Gross Citation2023), party allegiances bridge the council–executive distinction. Aldermen owe their position to their party and they unite with their party colleagues in the council as their fates are tied together. Aldermen joining meetings of ‘their’ party group is an indication of party coordination of council–executive relations (Peters and Castenmiller Citation2020, 26–27). Although mayors are formally appointed by the central government, in practice the recommendation of the council for a particular candidate is always followed. Moreover, Dutch mayors have few policy competencies apart from being responsible for public safety and are expected to be apolitical; the partisan background of the aldermen, who form the executive board with the mayor, is more important for the policies it pursues.

Within the interparty mode, two submodes – the intracoalition mode (coalition party vs coalition party) and the opposition mode (coalition parties vs opposition parties) – are recognised. The intracoalition mode is salient when conflicts among coalition councillors arise due to the need to govern together even though policy preferences may diverge, which can take the form of scrutinising coalition partners. However, the opposition mode has been considered particularly important and will be the focus of the remainder of this article. In the opposition mode, coalition councillors align together with the executive board to interact with opposition councillors. In Dutch councils, the coalition-opposition distinction became more salient after attempts in the 1970s to replace so-called ‘mirror coalitions’ – which reflect the composition of the council in a true monistic fashion – with minimum winning coalitions with a coalition agreement (Tops Citation1990).

The 2002 reforms were partly motivated by the observation that aldermen had more influence over ‘their’ party than the other way around in the interparty mode (Denters et al. Citation2000). This situation was described as ‘politicised monism’ (Denters and De Jong Citation1992) or as ‘coalition dualism’ (contrasted to institutional dualism) (Tops and Van der Volk Citation1993), because of the close cooperation between aldermen and the coalition parties vis-à-vis the opposition parties. Compared to dualistic council–executive relations, these (politicised) monistic council–executive relations were considered to contribute to executive dominance over a weak council.

Still today, opposition councillors feel less informed than coalition councillors, because coalition party groups coordinate the implementation of the coalition agreement and manage unexpected events during informal consultations (Peters and Castenmiller Citation2020, 28). Consequently, opposition councillors focus more on formal council instruments, like questions and amendments, to monitor and control the executive or to signal disagreement with the coalition (Otjes, Nagtzaam, and Van Well Citation2023; Verhelst, Reynaert, and Steyvers Citation2011), whereas coalition parties prioritise political interests over good information and accountability (Cole Citation2001; Peters and Castenmiller Citation2020, 31).

The crossparty mode

In the crossparty mode, non-partisan interests are the basis of interactions between councillors and members of the executive board. Councillors act as advocates of these interests. They form alliances with councillors and aldermen who defend similar interests and compete with councillors and aldermen defending other interests or generalists, regardless of party membership. The picture in being 90 degrees tilted emphasises that interactions in the crossparty mode not only ignore the legal distinction between the council and the executive, but also councillors’ membership of their party. Cross-party interests may originate from policy specialisation and local policy networks.

Councils are internally organised into specialised committees in which councillors may act more as policy specialists than as partisans; 30% of Dutch councillors consider themselves as specialist rather than generalist. According to 48% of Dutch councillors, party specialists determine the position of their party group on policy issues (Van Vonno Citation2019, 670). These findings offer further support for the impact that the division of labour within councils and party groups has on how councillors operate. Aldermen too specialise in a particular policy domain and are supported by specialist civil servants who may cater to certain needs of citizens or interest groups. This policy specialisation in councils and executive boards may transform politicians into ‘accomplices’ of certain departmental interests (Saalfeld Citation2000, 367).

Councillors who are involved with local policy networks are also likely to shift their focus of representation to special interest. Societal groups ask relatively frequently for local politicians’ support during policy processes (De Vries Citation2008). Councillors maintain contacts with leading actors from voluntary associations and private business representatives. Especially in ‘corporatist’ and ‘progrowth’ urban governance models, councillors ensure the involvement of local interest organisations and local business actors (Plüss Citation2013).

Explaining relations between councillors and executive members

To explain the prevalence of the non-party, interparty and crossparty modes across local councillors I employ a neo-institutionalist approach. Local political institutions provide a framework within which councillors must operate vis-à-vis other councillors and executive members: these are constraints for or offer opportunities to councillors to pursue their objectives, and they also generate norms which shape council behaviour.

At the municipality level, the institutional mechanisms that organise council support of the executive board affect council–executive relations. Whether executive coalitions are oversized or minimal winning affects the room of manoeuvre that councillors have. Oversized (or surplus majority) coalitions include one or more parties that are not needed for a majority, whereas minimal winning coalitions do not include such ‘unnecessary parties’ (Serritzlew, Skjæveland, and Blom-Hansen Citation2008). Both coalition types exist in Dutch local councils. After the local elections of 2014, 175 oversized coalitions – including more parties than necessary to control a council majority – were formed compared to 205 minimal winning coalitions (Boogaard Citation2015, 337).Footnote2

Under oversized coalitions, the opposition is relatively small and the opposition mode may therefore be less prevalent. Instead, the non-party mode may be more dominant because oversized coalitions are more secure against councillors who oppose the executive board. In minimal winning coalitions, party groups will be more likely to discipline their members to toe the coalition line and less likely to allow them to operate in the non-party mode, because opposition to the executive board will have more serious consequences than in oversized coalition (Andeweg Citation1992; Müller Citation1993). When coalitions are oversized and have a firm majority, councillors experience fewer constraints to operate in the non-party mode and to risk harming coalition unity.

Oversized coalition hypothesis: If the executive board is supported by an oversized coalition, councillors operate less frequently in the opposition mode and more frequently in the non-party mode than if it is supported by a minimal winning coalition.

A second institutional mechanism to ensure effective governance is the coalition agreement that parties negotiate during the formation process (Gross and Krauss Citation2021; Visser, Vollaard, and Meijerink Citation2015). Though not legally binding, coalition agreements significantly constrain the behaviour of coalition councillors. They do not only bind aldermen to the coalition parties, but also the coalition parties to each other. Proposals that originate from these agreements are expected to discipline coalition councillors as deviating from the coalition agreement may harm the stability and performance of the coalition. Opposition councillors are more likely to oppose these proposals either because of their content or to attack the coalition (cf. De Winter Citation2004). The proportion of the executive board’s proposals originating from the coalition agreement will be larger when that agreement comprises more policy details.

Coalition agreement hypothesis: The more comprehensive a coalition agreement is, the more frequently councillors operate in the opposition mode.

The broader institutional environment in which councillors operate depends on the size of their municipality. In municipalities with larger populations, there are generally more interest groups representing different sectoral interests than in municipalities with smaller populations (Baglioni et al. Citation2007), eloquently formulated by Dahl and Tufte (Citation1973) as the ‘Plumber’s Law’: ‘a community of 1,000 inhabitants is likely to have only one plumber – and no specific organization of plumbers. (…) A city of 100,000 will have 100 plumbers or so, and very likely an organization of plumbers. A city of a million, with 1,0000 plumbers, will probably have a plumbers’ organization with a number of subunits and some specialised services’ (39). These interest groups articulate sectoral interest and contact councillors to influence public policy.

Furthermore, the policy problems and policy processes are generally more complex in larger municipalities (Denters et al. Citation2014, 101–16). Addressing bigger societal problems concerning crime, poverty, migrants, etc., requires larger bureaucracies. The specialisation of the policy process also fosters policy specialisation among local councillors. The size of the council, which varies between 9 and 45 seats in the Netherlands depending on population size, also determines councillors’ opportunities for policy specialisation (Dahl and Tufte Citation1973). A more comprehensive interest group system together with institutional opportunities for policy specialisation are important conditions for the crossparty mode in which councillors build alliances based on non-partisan sectoral interests.

Municipality size hypothesis: The larger the population of the municipality is, the more frequently councillors operate in the crossparty mode.

Turning to a party-level explanation, the distinction between coalition and opposition parties is highly relevant. To ensure the stability of the coalition, coalition councillors may operate more often as one bloc vis-à-vis the opposition. A coalition councillor opposing the executive board risks damaging the coalition and the party’s image. Coalition councillors may anticipate this or may be pressured by aldermen or the party leadership to avoid operating in the non-party mode (Copus Citation2008; King Citation1976, 15; Van Vonno Citation2012). Opposition councillors do not experience these additional risks that are associated with the non-party mode (Otjes, Nagtzaam, and Van Well Citation2023). They may feel more freedom to build alliances across the coalition-opposition divide.

Opposition party hypothesis: Opposition councillors operate less frequently in the opposition mode and more frequently in the non-party mode than coalition councillors.

To explain individual-level differences, I rely on an application of the neo-institutionalist ‘logic of appropriateness’ (March and Olsen Citation1989): the roles that are connected to membership of a local council. A legislative role is a ‘coherent set of ‘norms’ of behaviour which are thought by those involved in the interactions being viewed, to apply to all persons who occupy the position of legislator’ (Wahlke Citation1962, 8). In local councils, roles prescribe behaviour that councillors consider most appropriate for them in their position in the council. The modes of executive–legislative relations are associated with distinct roles and expected behaviour:

[I]n the non-party mode, the MP sees his role as a ‘parliamentarian’, feels loyalty to the institution of parliament, representing ‘the’ people (…); in the inter-party mode, the MP sees himself as a ‘partisan’, loyal to his political party and its programme, representing his party’s voters (…); and in the cross-party mode, an MP defines his role as an ‘advocate’, representing a particular regional or sectoral (but nonpartisan) interest(…). (Andeweg Citation1997, 116)

Gender has been widely acknowledged as a factor that influences legislators’ role conception, most importantly because female legislators adapt their behaviour to people’s expectations about what appropriate behaviour is for men and women. Consequently, they are more cooperative, willing to compromise and less obstructive and conflictual than male legislators (Barnes Citation2016; Volden, Wiseman, and Wittmer Citation2013). Compared to male MPs, female MPs are less likely to attack their political opponents or to use incivility during parliamentary debates (Poljak Citation2022), and female opposition MPs focus less on conflicts with (or within) the coalition than male opposition MPs in parliamentary questions (De Vet and Devroe Citation2023). Therefore, the opposition mode being ‘characterized by, indeed defined by, conflict’ (King Citation1976, 18), should be less important for female councillors than for male councillors. Instead, women may be more likely to build alliances outside their parties to unite against the executive board in the non-party mode or to defend other interests in the crossparty mode.

Gender hypothesis: Female councillors operate less frequently in the opposition mode and more frequently in the non-party and crossparty modes than male councillors.

Legislative roles can further be subdivided into position roles and preference roles: ‘[p]osition roles are associated with positions that require the performance of many specific duties and responsibilities’, whereas preference roles are ‘associated with positions that require the performance of few specific duties and responsibilities’ (Searing Citation1994, 12). In other words, position roles do not leave much room to play other roles. Certain positions in local councils may prescribe councillors’ conceptions of their own roles and their operation in the modes of executive–legislative relations.

One such position is the vice-chairmanship of the council. According to the Dutch Local Government Act (article 77.1) the vice-chair replaces the mayor as chair of the council in their absence. In practice, they are also involved with preparations for council sessions as well as other duties revolving around the organisation of the council, e.g., chairing an agenda committee. Vice-chairs are generally expected to act as a politically neutral ‘guardian of the local council’, safeguarding the functioning of the council as a whole and representing the council vis-à-vis the executive board (Karsten and Zuydam Citation2019). Therefore, they should operate more often in the non-party mode than other councillors.

Another potential position role is the leadership of a party group. Though there is little formal regulation on party groups in local councils, the standard model of Dutch councils’ rules of procedures defines a party group as ‘councillors who were elected on the same candidate list’ and mentions a chairperson of the party group. This councillor chairs the (often weekly) party group meetings which most councillors consider the main decision-making centre in their party group (Van Vonno Citation2019, 670), and receive monetary compensation in addition to the regular allowance for councillors. As leaders of party groups are supposed to represent their party within the council they should operate more often in the interparty (and opposition) mode than other councillors.

The third potential position role is the chairmanship of council committees. The Dutch Local Government Act (art. 81, 19, 21) regulates that committee chairs organise committee meetings, create the agenda, and participate in those meetings. As committee chairs are supposed to represent their committees, which are usually specialised based on policy area, they should operate more often in the crossparty mode than other councillors.

Position hypothesis: Vice-chairs of councils operate more frequently in the non-party mode, leaders of party groups operate more frequently in the opposition mode, and chairs of council committees operate more frequently in the crossparty mode than other councillors.

Case selection and research design

This study analyses how Dutch councillors interact with each other and members of the local executive. The Netherlands is a decentralised unitary state. Like in many European local governments, elections are held using a PR party-list system. Consequently, multipartyism and coalitions are features of local politics. Dutch local government has the collective form with aldermen and a mayor forming a collegiate body responsible for all executive functions (Mouritzen and Svara Citation2002). Mayors are formally centrally appointed, but the difference with council-elected mayors has become smaller as the advice of the council on applicants is usually followed. Therefore, Dutch local government is roughly similar to Belgian, Luxembourgish, Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, Danish and Austrian local governments.

The structure of local government is the same for all Dutch municipalities in terms of competencies and institutional set-up (in contrast to countries like Germany or the United Kingdom), having the methodological advantage to circumvent the ‘many variables, small N’ problem because factors such as coalition agreement are comparable. However, the near absence of variation in the institutional characteristics of local government (except for council size) prevents the investigation of the effects of formal institutions on council–executive relations, such as the effects of the compatibility of membership of the council and the executive. The generalisability of the findings to two-party systems or strong-mayor forms of local government is probably quite limited.

The unit of analysis is the individual local councillor. At the time of the data collection (May and June 2018), there were 380 councils and 8,823 councillors in the Netherlands. A stratified sample of 25 councils was drawn. The best source for measuring the prevalence of the opposition, non-party and crossparty modes are councillors themselves. They are in the most favourable position to observe how they operate. In May and June 2018, a link to a short online questionnaire was sent by email to all persons who had been a member of one of the selected councils before the elections of March 2018 (together 571 [former] councillors). Councillors from this period were selected as they had sufficient experience at the time of the study; 260 (former) councillors (45.5%) responded; 11 did not complete the whole survey and were excluded from the analyses.Footnote3 Municipalities in the sample have on average a slightly smaller population than the universe of Dutch municipalities, but this difference is not statistically significant. The average effective number of parties is similar to the universe of Dutch municipalities. The number of very large urban municipalities is limited, however, and we must be careful with generalising the results beyond members of small and medium-sized municipalities.Footnote4 Because the largest councils have been described as more politicised (Tops Citation1990), the interparty mode may be underestimated.

The respondents were asked a few questions concerning their experiences as councillors during 2014–2018, the period between the two most recent local elections.Footnote5 This procedure produces a risk of a recency effect, where respondents’ memories are dominated by their most recent experiences. However, the main interest of this study is to explain the variation in the prevalence of the modes. All respondents were asked to fill in the questionnaire around the same time, so an equal recency effect on all respondents is assumed. Respondents were asked to describe how often their relations with other councillors and the executive board had resembled descriptions of the opposition, non-party and crossparty modes on 7-point scales, where 1 represents ‘(almost) never’ and 7 represents ‘(almost) always’.Footnote6 Councillors from parties that had been represented in the executive board were considered coalition councillors, whereas councillors of parties without representation in the executive board were considered opposition councillors. Respondents were also asked about their gender and whether they had been vice-chair of their council, leader of their party group and chair of a council committee. Furthermore, respondents were invited to submit written comments to their answers to closed-ended questions.

At the municipality level, information about coalition types and coalition agreements was retrieved from public sources, usually municipality websites. When publicly available information was insufficient, municipalities were contacted to provide additional information. The length of coalition agreements in number of words was used as a proxy for coalition agreement comprehensiveness (Müller and Strøm Citation2008; Visser, Vollaard, and Meijerink Citation2015). Obviously, the number of words in coalition agreements does not necessarily express how comprehensive it is. Vague statements or the language creativity of the official who drafts the agreement may positively influence a coalition agreement’s length. However, it is impossible for short agreements to represent many constraints. Longer agreements are more likely to cover more policies and more detailed compromises. Even vague statements can set the agenda or remove the status quo policy option. Above all, empirically the number of words in national coalition agreements correlates highly with their precision and completeness (Indridason and Kristinsson Citation2013, 830–31; Timmermans and Moury Citation2006). Municipality size was operationalised as the number of inhabitants on 1 January 2018 as registered by Statistics Netherlands (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek).

Two control variables were included to account for any interference in modelling the effects of the explanatory variables. First, the fragmentation of the local party system operationalised as the effective number of parties was added to the model (Laakso and Taagepera Citation1979), because of its consequences for patterns of coalition formation and relations between the coalition majority and the opposition. Second, a dummy for councillors of independent local parties (versus local branches of national parties) was included. Independent local parties are the largest ‘party family’ in Dutch local councils but vary substantially in their profiles and backgrounds. Despite their differences, councillors of local parties are generally more orientated towards their representational role of connecting with local society rather than their administrative and governing roles (Boogers Citation2023; Denters Citation2023).

The survey data have a hierarchical structure in which councillors are nested within local councils. To account for correlated errors for councillors within a local council, a multilevel regression model was conducted, allowing intercept coefficients to vary by council. To correct for the skewed distribution of coalition agreement length, a log transformation was performed. In the absence of a coalition agreement the variable was coded 0. The continuous dependent and independent variables were rescaled to range from 0 to 1 enabling a more meaningful interpretation of the effect sizes.Footnote7

Empirical evidence from Dutch local councils

summarises councillors’ answers to the questions of how often their interactions with other councillors and the executive board resembled the opposition, non-party and crossparty modes. On average, councillors most frequently operate in the opposition mode (mean = 4.2). This is substantially and significantly more often than the frequency in which councillors operate in the non-party and crossparty modes. However, there is substantial variation. The frequency distribution of the opposition mode is roughly equally distributed around the middle category. Even though the importance of the opposition mode may be slightly overestimated due to the previously discussed recency effect,Footnote8 the opposition mode is clearly most important in the relations between Dutch councillors and executive boards. The three modes are strongly correlated positively.Footnote9 This indicates that the modes capture distinct aspects of a general level of conflict within local politics and that the three modes coexist simultaneously.

Opposition councillors operating frequently in the opposition mode often say this is due to the coalition acting as a unified front and being unwilling to support opposition proposals such as amendments or resolutions: ‘The coalition opposed almost by definition anything initiated by the opposition. Whereas the opposition followed its own political line per party, especially with regard to proposals from the executive board, and therefore often, mostly, supported the board’s proposals’.Footnote10 According to many of them, this is an explicit strategy of the coalition: ‘[T]here was a clear rule from the coalition to not support issues from the opposition’. According to one opposition councillor, coalition councillors regularly express dissatisfaction with the executive board in private but always unify with the executive board in public. Some coalition councillors spontaneously mention these complaints raised by the opposition. Although they may also operate in the opposition mode, they explain their behaviour by referring to the larger agreement on local policies among coalition parties: ‘The opposition (…) suspected us of having made an issue [policy proposal] watertight. That was not the case. Although we regularly shared our substantive positions on issues. Logically. If you can’t get through a door with each other, you won’t become a coalition’.

Although the opposition mode is dominant in Dutch local councils, councillors also operate in the non-party and crossparty modes, though less frequently. The difference between the frequency of councillors operating in the non-party (mean = 2.7) and the crossparty modes (mean = 2.6) is negligible and not statistically significant. The frequency distributions of both the non-party and the crossparty modes are positively skewed; 31% of the respondents operate (almost) never in the non-party mode and 35% of the respondents operate (almost) never in the crossparty mode. Respondents probably had the most difficulty with the crossparty mode; more respondents answered ‘don’t know/no opinion’ (15 against 2 for the opposition and non-party modes) and the distribution of the crossparty mode has a second peak at the middle category (18%). This is an indication that the middle category attracted many respondents who were not sure what to answer but tried to give a more or less acceptable answer anyway.

Those councillors frequently operating in the non-party mode emphasise the dominance of the executive board. ‘The board just did its own thing (…), not fun for the opposition, but certainly not for coalition parties’, according to one opposition councillor. Other councillors mention instances of the council as a whole controlling the executive board. One coalition councillor wrote that the council was occasionally dissatisfied with an alderman’s proposals: ‘Not our problem, we were elected to represent the interests of our voters’. When the whole council opposes a certain executive proposal, the alderman typically adapts them to the council’s preferences or withdraws them, according to multiple respondents. However, coalition discipline is pointed to as the reason for councillors operating relatively little in the non-party mode.

Regarding the crossparty mode, one councillor argues that councillors’ specialisations into a specific policy area give them an information advantage making it easy to convince councillors with other policy specialisations. Some councillors who operate barely in the crossparty mode refer again to the strong dominance of parties and more specifically the coalition-opposition divide. ‘I discuss [frictions between my portfolio and others] within my party group and they can be resolved ideologically very well’, according to a councillor operating (almost) never in the crossparty mode (‘1’).

Regression analyses

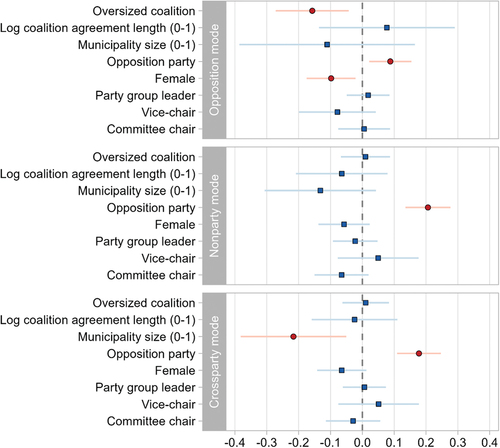

The results of the multilevel linear regression analyses of the opposition, non-party and crossparty modes are presented in .Footnote11 Because all variables were rescaled to range from 0 to 1, the regression coefficients indicate the percentage point change in the frequency in which councillors operate in a specific mode from the minimum to the maximum in the independent variables (or from the baseline to the alternative category for binary variables).

Figure 3. Coefficient plot of multilevel regression analyses of the opposition, non-party and crossparty modes. Note: error bars denote 95% confidence intervals. Circle points denote statistical significance (p < .05). Control variables are not displayed.

As expected, councillors operate less frequently in the opposition mode when the coalition is oversized (mean = 3.6) than when it is minimal winning (mean = 4.4). Controlling for the other variables, councillors operate 16%-points less frequently in the opposition mode under oversized coalitions than under minimal winning coalitions (p = .015). Although respondents are slightly more likely to operate in the non-party mode under oversized coalitions, this difference is not statistically significant neither is the effect of coalition type in the model of the crossparty mode.

Councillors from opposition parties were expected to operate less frequently in the opposition mode and more frequently in the non-party mode than councillors from coalition parties. In support of the opposition party hypothesis, opposition councillors’ responses to the non-party mode survey question are on average higher (mean = 3.5) than those of coalition councillors (mean = 2.1). However, contrary to the opposition party hypothesis, opposition councillors are also more likely to operate in the opposition mode (mean = 4.6) than coalition councillors (mean = 3.8). In fact, opposition councillors operate substantially more frequently than coalition councillors in all three modes, representing the strongest effects found in these analyses. Controlling for the other variables, they operate 9%-points more frequently in the opposition mode (p = .010), 21%-points more frequently in the non-party mode (p < .001) and 18%-points more frequently in the crossparty mode (p < .001) than coalition councillors.

Partly supporting the gender hypothesis female councillors operate substantially less frequently in the opposition mode (mean = 3.6) than male councillors (mean = 4.3). Their responses to the opposition mode question are 10%-points lower than those of male councillors, controlling for the other variables (p = .013). In our sample female respondents operate also slightly less in the other two modes than male respondents, but these differences are smaller and do not reach conventional levels of significance. Contrary to the expectation, municipality size decreases the frequency of councillors operating in the crossparty mode. Although larger municipalities should theoretically be a more conducive environment for the crossparty mode, councillors in the largest municipality operate 22%-point less often in the crossparty mode than councillors in the smallest municipality, controlling for the other variables (p = .011). The effects of the other explanatory variables are smaller and not statistically significant, although the effects of coalition agreement length on the opposition mode and of being vice-chair of the council on the non-party mode are in the expected direction.Footnote12 Regarding the control variables, the substantial and statistically significant effect of being a member of an independent local party deserves mentioning. Councillors of local parties operate 14%-point more frequently in the opposition mode than councillors of national parties (p < .001, see Appendix C).

Shifting between modes

The empirical evidence presented thus far has provided evidence that the existence of the opposition, non-party and crossparty modes are not mutually exclusive. This can be the result of either councillors specialising in one mode or of councillors shifting between modes depending on the situation at hand. In role theory, switching between roles rather than specialising in one particular role has been argued to be quite plausible: ‘it would seem to be an oversimplification to classify MPs based on a single role orientation, just as odd as classifying great actors as either “Hamlets”, “Uncle Vanyas”, or “Algy Moncrieffs”’ (Andeweg Citation1997, 122; cf.; Wahlke Citation1962, 17).

The available data allow for a measurement of the degree of shifting between modes of executive–legislative relations. The lowest degree of mode shifting is achieved when a councillor operates (almost) always in one mode, while they operate (almost) never in the other two modes (perfect specialiser). When a councillor operates equally frequently in all three modes, the degree of mode shifting is highest (and a councillor shifts between modes to the same degree; perfect shifter). To capture the relative frequencies of the three modes, the level of dispersion of the modes was calculated for each respondent, rescaled to range from 0 to 1 and inversed to ease interpretation. Using the standard deviation measure this was calculated as follows:

where modem represents the frequency in which a councillor operates in mode m. The higher this value is the more a councillor shifts between the three modes; ‘1’ indicates a perfect mode shifter: a councillor operating equally frequently in the opposition, non-party and crossparty modes (e.g., ‘6’ for all modes, or ‘1’ for all modes); ‘0’ indicates a perfect mode specialiser: a councillor operating (almost) always in one mode (e.g., the opposition mode), while (almost) never operating in the other two modes (e.g., the non-party and crossparty modes). The mean of the mode shifting measure is 0.65, but there is substantial variation (). As mode specialisers almost exclusively specialise in the opposition mode, shifting between modes is the most important explanation of the coexistence of the three modes in Dutch local councils.

Figure 4. Histogram of the degree to which councillors shift between the opposition, non-party and crossparty modes.

Why do some councillors shift more between modes than others do? A possible institutional explanation for these differences may be the size of the local council (cf. Van Vonno Citation2012). As the number of seats in councils increases, workforce and resources increase, while the number of tasks councillors are expected to perform remains the same. Large councils, therefore, may allow their members to specialise in one particular mode, whereas small councils force councillors to shift between modes.

Mode shifting hypothesis: The larger the local council is, the lower the degree to which councillors shift between modes.

The effect between council size and mode shifting is indeed negative and statistically significant, but quite small, r = −.14, p = .036 (). Controlling for party group size in a multilevel model, the effect remains negative – councillors shifting 11%-points less in the largest council compared to the smallest – but loses its statistical significance.

Figure 5. Scatterplot (with jitter) of the relationship between local council size and mode shifting.

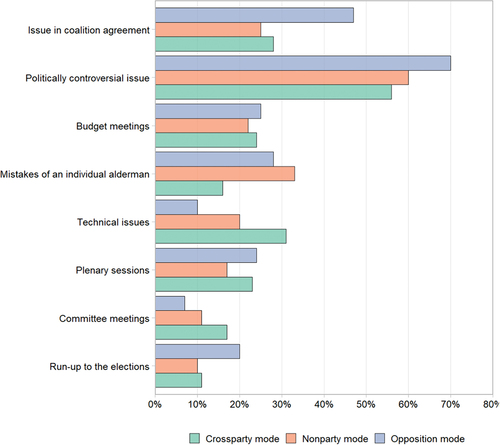

A second question about mode shifting is under what circumstances councillors shift to a particular mode. Whenever respondents did not choose an extreme position when asked how frequently they operated in a mode of executive–legislative relations, they were asked a follow-up question presenting them with various situations which had influenced their operation in that mode (cf. Andeweg Citation1997). These situations included features of the issue at hand (politically controversial, technical, budget, mentioned in the coalition agreement), the arena (plenary session, committee meeting) and timing (run-up to the elections). For each situation, respondents indicated whether they would be more likely to shift to the mode concerned ().

It is not surprising that the level of conflict is higher for politically controversial issues. For the purposes here, the relative importance of the situations for each mode is important. Relatively speaking, the most important discriminating factor is whether an issue was mentioned in the coalition agreement. A coalition councillor who operates seldom in the opposition mode writes that ‘[o]nly in the situation that the executive board was on the brink of resigning over an issue in the coalition agreement did I have the feeling we were opposing the opposition’. Next, politically controversial issues are an important reason to shift to the opposition mode. Mistakes of an individual alderman, during which the council function of oversight is crucial, are relatively more often mentioned as a situation in which councillors shift to the non-party mode, though the opposition mode is not far behind. During these affairs, coalition councillors possibly tend to collude with the alderman in question to protect coalition unity. As was to be expected, technical issues are relatively more associated with the crossparty mode and least associated with the opposition mode. One councillor mentions that cooperation was rarely possible, mostly on ‘matters of minor importance’.

Concerning the two different council arenas, the differences regarding plenary sessions are very small, whereas a shift to the opposition mode may have been expected. However, during committee meetings, in which the policy specialists of party groups are the main actors, councillors tend to shift to the crossparty mode. During the run-up to the next local council elections, relatively many respondents shift towards the opposition mode. Moving through the political business cycle party groups become more dominant to advertise their platform to the public resulting in a shift towards the interparty (and opposition) mode.

Discussion and conclusion

I have argued that relations between local councillors and executive boards can be conceptualised as relations between two cohesive institutions (non-party mode), as relations between actors across the council–executive divide based on party or coalition allegiances (interparty mode, subdivided into an intracoalition and opposition mode), or based on other special interests (crossparty mode) (Andeweg and Nijzink Citation1995; King Citation1976). Having presented empirical evidence of these patterns of interactions this study found the interparty mode, operationalised as the opposition mode, to be dominant in Dutch local councils. Despite the non-party mode’s normative and constitutional significance, it is of relatively minor importance in actual relations between councillors and executive boards, as is the crossparty mode. Although not equally strong, all modes are present in council–executive relations.

Several institutional explanations for council–executive relations were examined. The analyses showed that councillors operate less frequently in the opposition mode when the governing coalition is oversized. Smaller coalition majorities lead to a stronger coalition-opposition divide in the council. However, no support was found for the expectation that councillors would operate more often in the non-party mode under oversized coalitions. Conforming to predominant expectations about women politicians, female councillors are less likely to operate in the opposition mode than male councillors, but contrary to expectations they do not operate more often in the non-party and crossparty modes. As expected, opposition councillors operate more frequently in the non-party mode than coalition councillors. Coalition councillors are probably less inclined to seek confrontation with members of the board they support. Although they were expected to have more incentives to operate in the opposition mode than opposition councillors, a reversed correlation was found between opposition membership and the opposition mode.

Interestingly, the findings suggest that opposition councillors operate more frequently in all three modes. However, it remains an empirical question to what extent councillors’ actual behaviour resembles the descriptions they responded to. One limitation of this study is the reliance on self-report data, which may differ from their actual behaviour for several reasons, e.g., social desirability bias. Because of the normative bias against ‘monism’, which resembles the opposition mode, coalition councillors may have emphasised how they operate independently from their coalition partners and party colleagues in the executive board. Another possible explanation is that members of the coalition experience less conflict in general, or at least within the relationships that are described by the opposition, non-party and crossparty modes. The intracoalition mode (or an intraparty mode) may be more salient to them.

Another puzzling finding is that the size of the municipality affected the operation in the crossparty mode negatively, whereas increased opportunities for policy specialisation and stronger policy networks were expected to make this mode more dominant. One possibility is that politicians in smaller municipalities are less influenced by national political dynamics and be more pragmatic compared to politicians in larger municipalities (cf. Haselbacher and Segarra Citation2022).Footnote13

There may be other potential bases for the crossparty mode than sectoral interests. Ties with less formalised social networks and small communities may be even more important for local politics. Councillors may act as local problem solvers on behalf of these groups. The proximity between councillors and their voters and communities is probably smaller in smaller municipalities and ‘such proximity brings with it a blurring of the boundaries between the political, personal and private life of the councillor and which can see one facet or another of council duties and responsibilities spill into the councillor’s work and social life’ (Copus Citation2016, 106). Unfortunately, the data to examine this were not available.

The remaining explanatory variables failed to reach conventional levels of statistical significance. The irrelevance of coalition agreements for the prevalence of the opposition mode is particularly surprising. In the literature on coalition governance, written policy agreements are considered a crucial means to bind governments and coalition parties to each other. Coalition agreements at the local have been an understudied phenomenon though (Martin Gross and Krauss Citation2021; Visser, Vollaard, and Meijerink Citation2015). More research is needed to examine to what extent the use of coalition agreements at the local level differs from the national level.

Institutional positions were expected to be among the strongest determinants of councillors’ relations with each other and the executive board, as their position roles prescribe the operation in a particular mode. One possible explanation is that these roles are not position roles as defined by Searing (Citation1994) in all contexts. For example, the position of committee chair may only be relevant to a councillor during the committee meeting that they chair. In other situations, such as plenary debates or participation in another committee, this position does not produce its normative expectations. In other words, the positions of vice-chair, party group leader and committee chair are not total institutions that shape all council behaviour. Role conception as a mediating variable between position and operating in the modes was missing in the analyses. Positions may explain councillors’ role conception, but other factors may prevent the latter’s effect on actual behaviour, e.g., due to role conflict.

The final part of this study’s investigation focused on how often and why councillors shift between the interparty, non-party and crossparty modes. The exploration of reasons to shift between the three modes offers indications for the importance of the specific issue at hand. The findings suggest that councillors deal with politically salient issues in the interparty mode. The non-party mode may be more important when the position of the council is at stake, for example when aldermen make mistakes or do not give certain information to the council. Councillors shift to the crossparty mode when dealing with technocratic issues, policy details, or when interests not being politically controversial are at stake. Although there is substantial variation in the degree of mode shifting, this can hardly be accounted for by the size of the council. Future work could focus on the characteristics of individual councillors to explain why some of them shift a lot between modes, while others tend to specialise, e.g., level of education or political experience.

Clearly, the relationship between councillors and executive boards is an issue which requires further investigation. The present study has shown that considering various modes of council–executive relations aids this. For example, future work could apply this framework to a mayor-council system to examine the impact of a stronger mayor on council–executive relations. It is encouraging that Verhelst and Peters (Citation2024) recently presented an analytical framework of council scrutiny that considers three motivations for scrutiny activities that roughly fit the interparty, crossparty and non-party modes:

Politically, [scrutiny] can serve as a conscious act to defend the office’s position, as a partisan act (…). Instrumentally, scrutiny can improve government performance or understand policies and develop knowledge and expertise (policy entrepreneurialism). Legally, scrutiny can be inspired by the desire to secure the proper functioning of the legislature (council management)’.Footnote14

Exploring these different patterns of interactions has nuanced the dualism between councils and executives and has emphasised the central role that parties play in local councils. Distinguishing between various modes of council–executive relations thus offers a more complex but also more realistic image of relations between councillors and members of the executive board.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (47 KB)Acknowledgments

I thank Rudy Andeweg, Peter Castenmiller, the attendants of the workshop on local government of the 2021 Dutch-Flemish political science conference and the anonymous peer reviewers for comments on earlier versions of this paper. I thank Max Pepels for his assistance in the design of .

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2024.2349162.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. See Müller (Citation1993, footnote 1) for differences in the interpretation of the modes of executive-legislative relations.

2. None of the executive boards were based on minority support.

3. Respondents were informed about the aims of the study, and they were promised full confidentiality. Their consent was required before moving forward with the questionnaire. Ethical approval was not required. Sample details are described in Appendix A.

4. Nijmegen en Westland are the two municipalities in the sample with more than 100,000 inhabitants. As one of the anonymous reviewers has argued, future work might consider systematic (instead of stratified) random sampling to decrease the potential for sampling issues.

5. In 5 municipalities the partisan composition of the executive coalition changed during 2014–2018. The respondents from these municipalities were explicitly asked to answer the survey questions with the period of the most recent coalition in mind (Appendix A).

6. See Appendix B for the question wording. My approach was inspired by Andeweg (Citation1992) who uses data from a single survey question asking Dutch MPs to identify the pattern of interactions that dominates executive-legislative relations in the Netherlands.

7. See Appendix C for descriptive statistics.

8. The election campaign of 2018 may have incentivised councillors to operate more frequently in the opposition mode during the final period of investigation (see below).

9. Pearson’s Rs for opposition/non-party mode: .445, p < .001; opposition/crossparty mode: .369, p < .001; non-party/crossparty mode: .567, p < .001.

10. All quotations from respondents were translated by the author.

11. See Appendix C for tables presenting the results of the multilevel models and descriptive statistics of the variables.

12. In the municipalities Opmeer and Etten-Leur the coalition parties did not write a coalition agreement. Instead, (almost) all parties wrote a policy programme that the executive board was supposed to execute. This type of ‘council-wide’ agreement (raadsbreed akkoord) was explicitly meant to weaken the coalition-opposition divide and to strengthen the autonomy of the council vis-à-vis the executive board. Unfortunately, it was impossible to disentangle the effects of the absence of a coalition agreement and the presence of a council-wide agreement, as there were no cases with neither or with both agreements. In these two councils, the opposition mode was less prevalent (mean = 3.5) than in the other councils (mean = 4.2).

13. I thank one of the anonymous reviewers for this suggestion.

14. Emphases added.

References

- Andeweg, R. B. 1992. “Executive-Legislative Relations in the Netherlands: Consecutive and Coexisting Patterns.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 17 (2): 161–182. https://doi.org/10.2307/440056.

- Andeweg, R. B. 1997. “Role Specialisation or Role Switching? Dutch MPs Between Electorate and Executive.” The Journal of Legislative Studies 3 (1): 110–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572339708420502.

- Andeweg, R. B., and L. Nijzink. 1995. “Beyond the Two-Body Image: Relations Between Ministers and MPs.” In Parliaments and Majority Rule in Western Europe, edited by H. Döring, 152–178. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Ashworth, R., and S. Snape. 2004. “An Overview of Scrutiny: A Triumph of Context Over Structure.” Local Government Studies 30 (4): 538–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300393042000318987.

- Bäck, H. 2003. “Explaining and Predicting Coalition Outcomes: Conclusions from Studying Data on Local Coalitions.” European Journal of Political Research 42 (4): 441–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00092.

- Bäck, H. 2005. “The Institutional Setting of Local Political Leadership and Community Involvement.” In Urban Governance and Democracy: Leadership and Community Involvement, edited by M. Haus, H. Heinelt, and M. Stewart, 65–101. London: Routledge.

- Baglioni, S., B. Denters, L. Morales, and A. Vetter. 2007. “City Size and the Nature of Associational Ecologies.” In Social Capital and Associations in European Democracies: A Comparative Analysis, edited by W. A. Maloney and S. Roßteutscher, 224–43. 16. London: Routledge.

- Barnes, T. D. 2016. Gendering Legislative Behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boogaard, G. 2015. “Van afspiegelingscolleges naar procescolleges: Decentrale coalitievorming in 2014.” Tijdschrift voor Constitutioneel Recht 6 (4): 330–344. https://doi.org/10.5553/TvCR/187966642015006004001.

- Boogers, M. 2023. “Lokalo’s in de gemeenteraad: Doen ze het anders?” Bestuurswetenschappen 77 (1): 12–18. https://doi.org/10.5553/Bw/016571942023077001003.

- Castenmiller, P., and K. Peters. 2018. ‘Wel aan het hoofd, maar niet de baas: De verhouding tussen raad en college in de praktijk’. In De Gemeenteraad: Ontstaan en ontwikkeling van de lokale democratie, edited by H. Vollaard, G. Boogaard, J. Van den Berg, and J. Cohen, 207-223. Amsterdam: Boom Uitgevers.

- Cole, M. 2001. “Local Government Modernisation: The Executive and Scrutiny Model.” The Political Quarterly 72 (2): 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.00362.

- Copus, C. 2004. Party Politics and Local Government. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Copus, C. 2008. “English Councillors and Mayoral Governance: Developing a New Dynamic for Political Accountability.” The Political Quarterly 79 (4): 590–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2008.00961.x.

- Copus, C. 2016. In Defence of Councillors. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Copus, C., and G. Erlingsson. 2012. “Parties in Local Government: A Review.” Representation 48 (2): 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2012.683489.

- Dahl, R. A., and E. R. Tufte. 1973. Size and Democracy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Damgaard, E. 2000. “Parliament and Government.” In Beyond Westminster and Congress: The Nordic Experience, edited by P. Esaiasson and K. Heidar, 265–280. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press.

- Debus, M., and M. Gross. 2016. “Coalition Formation at the Local Level: Institutional Constraints, Party Policy Conflict, and Office-Seeking Political Parties.” Party Politics 22 (6): 835–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815576292.

- De Groot, M. S., B. Denters, and P.-J. Klok. 2010. “Strengthening the Councillor as a Representative and Scrutiniser: The Effects of Institutional Change on Councillors’ Role Orientations in the Netherlands.” Local Government Studies 36 (3): 401–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003931003730469.

- Denters, B. 2006. “Duo or Duel? The Relations Between Mayors and Councils in Democratic Local Government.” In The European Mayor: Political Leaders in the Changing Context of Local Democracy, edited by H. Bäck, H. Heinelt, and A. Magnier, 271–285. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90005-6_12.

- Denters, B. 2023. “Lokale en niet-lokale raadsleden: Verschillen en overeenkomsten in stijl en focus van representatie.” Bestuurswetenschappen 77 (1): 19–35. https://doi.org/10.5553/Bw/016571942023077001004.

- Denters, B., and H. M. De Jong. 1992. Tussen burger en bestuur: Een empirisch onderzoek naar de positie van het raadslid in de Overijsselse gemeenten. Enschede: Twente University - CBOO.

- Denters, B., M. J. F. Goldsmith, A. Ladner, P. E. Mouritzen, and L. E. Rose. 2014. Size and Local Democracy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Denters, B., H. Van der Kolk, E. Birkenhager, H. M. De Jong, A. M. Loots, and R. M. Noppe. 2000. “Aan het hoofd der gemeente staat…: Een onderzoek naar de werking van het formele gemeentelijke bestuursmodel ten behoeve van de Staatscommissie Dualisme en lokale democratie.” In Dualisme en lokale democratie, edited by Staatscommissie Dualisme en lokale democratie, 143–227. Alphen aan den Rijn: Samsom.

- Denters, B., H. Van der Kolk, and P.-J. Klok. 2005. “The Reform of the Political Executive in Dutch Local Government.” In Transforming Political Leadership in Local Government, edited by R. Berg and N. Rao, 15–28. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- De Vet, B., and R. Devroe. 2023. “Gender and Strategic Opposition Behavior: Patterns of Parliamentary Oversight in Belgium.” Politics & Governance 11 (1): 97–107. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v11i1.6135.

- De Vries, M. S. 2008. “Stability Despite Reforms: Structural Asymmetries in Dutch Local Policy Networks.” Local Government Studies 34 (2): 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930701852286.

- De Winter, L. 2004. “Government Declarations and Law Production.” In Patterns of Parliamentary Behavior: Passage of Legislation Across Western Europe, edited by H. Döring and M. Hallerberg, 35–56. London: Routledge.

- Egner, B., and H. Heinelt. 2008. “Explaining the Differences in the Role of Councils: An Analysis Based on a Survey of Mayors.” Local Government Studies 34 (4): 529–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930802217504.

- Gross, M. 2023. “Determinants of Government Membership at the Subnational Level: Empirical Evidence from Large Cities in Germany (1999–2016).” Government and Opposition 58 (1): 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.41.

- Gross, M., and S. Krauss. 2021. “Topic Coverage of Coalition Agreements in Multi-Level Settings: The Case of Germany.” German Politics 30 (2): 227–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2019.1658077.

- Haselbacher, M., and H. Segarra. 2022. “Politics of Adjustment: Rural Mayors and the Accommodation of Refugees.” Territory, Politics, Governance 10 (3): 346–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2021.1934101.

- Indridason, I. H., and G. H. Kristinsson. 2013. “Making Words Count: Coalition Agreements and Cabinet Management.” European Journal of Political Research 52 (6): 822–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12022.

- Karsten, N., L. Schaap, and F. Hendriks. 2014. “Krachtig en kwetsbaar: De Nederlandse burgemeester en de staat van een hybride ambt.” Bestuurswetenschappen 68 (3): 48–67. https://doi.org/10.5553/Bw/016571942014068003004.

- Karsten, N., and S. Zuydam. 2019. “Hoeder van de raad of functie zonder inhoud? Een beschouwing op het vicevoorzitterschap van de gemeenteraad.” Bestuurswetenschappen 73 (3): 3. https://doi.org/10.5553/Bw/016571942019073003003.

- King, A. 1976. “Modes of Executive-Legislative Relations: Great Britain, France, and West Germany.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 1 (1): 11–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/439626.

- Klok, P.-J., and B. Denters. 2013. “The Roles Councillors Play.” In Local Councillors in Europe, edited by B. Egner, D. Sweeting, and P.-J. Klok, 63–83. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Laakso, M., and R. Taagepera. 1979. ““Effective” Number of Parties: A Measure with Application to West Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 12 (1): 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041407901200101.

- Leach, S., and C. Copus. 2004. “Scrutiny and the Political Party Group in UK Local Government: New Models of Behaviour.” Public Administration 82 (2): 331–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-3298.2004.00397.x.

- March, J. G., and J. P. Olsen. 1989. Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basis of Politics. New York, N.Y./London: The Free Press/Collier MacMillan.

- Mouritzen, P. E., and J. H. Svara. 2002. Leadership at the Apex: Politicians and Administrators in Western Local Governments. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Müller, W. C. 1993. “Executive-Legislative Relations in Austria: 1945–1992.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 18 (4): 467–494. https://doi.org/10.2307/439851.

- Müller, W. C., and K. Strøm. 2008. “Coalition Agreements and Cabinet Governance.” In Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining: The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe, edited by K. Strøm, W. C. Müller, and T. Bergman, 159–199. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Navarro, C., D. Karlsson, J. Magre, and I. Reinholde. 2018. “Mayors in the Town Hall: Patterns of Relations and Conflict Among Municipal Actors.” In Political Leaders and Changing Local Democracy: The European Mayor, edited by H. Heinelt, A. Magnier, M. Cabria, and H. Reynaert, 359–385. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Otjes, S. P., M. A. M. Nagtzaam, and R. L. van Well. 2023. “Scrutiny and Policymaking in Local Councils: How Parties Use Council Tools.” Local Government Studies 49 (5): 1110–1134. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2022.2123799.

- Peters, K., and P. Castenmiller. 2020. “Kaderstellen en controleren door de gemeenteraad: Een zware opgave.” Bestuurswetenschappen 74 (2): 10–33. https://doi.org/10.5553/Bw/016571942020074002003.

- Plüss, L. 2013. “Urban Governance and Its Impact on the Role Perception and Behaviour of European City Councillors.” Local Government Studies 39 (5): 721–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.670750.

- Plüss, L., and D. Kübler. 2013. “Coordinating Community Governance? Local Councillors in Different Governance Network Arrangements.” In Local Councillors in Europe, edited by B. Egner, D. Sweeting, and P.-J. Klok, 203–219. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Poljak, Ž. 2022. “The Role of Gender in Parliamentary Attacks and Incivility.” Politics & Governance 10 (4): 286–298. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v10i4.5718.

- Razin, E. 2013. “Councillors and Their Parties.” In Local Councillors in Europe, edited by B. Egner, D. Sweeting, and P.-J. Klok, 51–62. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Russell, M., and P. Cowley. 2018. “Modes of UK Executive–Legislative Relations Revisited.” The Political Quarterly 89 (1): 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12463.

- Saalfeld, T. 1990. “The West German Bundestag After 40 Years: The Role of Parliament in a “Party Democracy”.” West European Politics 13 (3): 68–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389008424807.

- Saalfeld, T. 2000. “Members of Parliament and Governments in Western Europe: Agency Relations and Problems of Oversight.” European Journal of Political Research 37 (3): 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00517.

- Schaap, L. ’. 2019. Lokaal bestuur. 8th ed. Dordrecht: Convoy Uitgevers BV.

- Searing, D. D. 1994. Westminster’s World: Understanding Political Roles. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Serritzlew, S., A. Skjæveland, and J. Blom-Hansen. 2008. “Explaining Oversized Coalitions: Empirical Evidence from Local Governments.” The Journal of Legislative Studies 14 (4): 421–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572330802442774.

- Sweeting, D. 2009. “The Institutions of “Strong” Local Political Leadership in Spain.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 27 (4): 698–712. https://doi.org/10.1068/c08114.

- Timmermans, A., and C. Moury. 2006. “Coalition Governance in Belgium and the Netherlands: Rising Government Stability Against All Electoral Odds.” Acta Politica 41 (4): 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500139.

- Tops, P. W. 1990. Afspiegeling en afspraak: Coalitietheorie en collegevorming in Nederlandse gemeenten (1946–1986). Den Haag: VUGA.

- Tops, P. W. 1993. “Monisme en dualisme: Het “primaat van de raad” nader nekeken.” In Leden van de Raad, …: Hoe zien raadsleden uit zeven grote gemeenten het raadslidmaatschap?, edited by B. Denters, and H. Van der Kolk, 145–167. Delft: Eburon.

- Van Vonno, C. M. C. 2012. “Role-Switching in the Dutch Parliament: Reinvigorating Role Theory?” The Journal of Legislative Studies 18 (2): 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2012.673061.

- Van Vonno, C. M. C. 2019. “Achieving Party Unity in the Netherlands: Representatives’ Sequential Decision-Making Mechanisms at Three Levels of Dutch Government.” Party Politics 25 (5): 664–678. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819836042.

- Verhelst, T., and K. Peters. 2024. “Scrutinising Council Scrutiny: From Theoretical Black Box to Analytical Toolbox1.” Local Government Studies 50 (1): 128–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2023.2185227.

- Verhelst, T., H. Reynaert, and K. Steyvers. 2011. “Foundation or Fragment of Local Democracy? Empirically Assessing the Roles of Local Councillors in Belgian Governance.” Lex Localis - Journal of Local Self-Government 9 (2): 103–122. https://doi.org/10.4335/9.2.103-122(2011).

- Visser, J., H. Vollaard, and F. Meijerink. 2015. “Hoe korter, des te langer? Over het verband tussen coalitieakkoorden en conflicten in gemeenten.” Bestuurswetenschappen 69 (4): 6–22. https://doi.org/10.5553/Bw/016571492015069004002.

- Volden, C., A. E. Wiseman, and D. E. Wittmer. 2013. “When are Women More Effective Lawmakers than Men?” American Journal of Political Science 57 (2): 326–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12010.

- Wahlke, J. C. 1962. “Theory: A Framework for Analysis.” In The Legislative System: Explorations in Legislative Behaviour, edited by J. C. Wahlke, H. Eulau, W. Buchanan, and L. C. Ferguson, 3–28. New York: John Wiley.