Abstract

Background

Poor academic performance and failure can cause undesired effects for students, schools, and society. Understanding why some students fail while their peers succeed is important to enhance student performance. Therefore, this study explores the differences in the learning process between high- and low-achieving pre-clinical medical students from a theory of action perspective.

Methods

This study employed a qualitative instrumental case study design intended to compare two groups of students—high-achieving students (n = 14) and low-achieving students (n = 5), enrolled in pre-clinical medical studies at the Universiti Malaya, Malaysia. Data were collected through reflective journals and semi-structured interviews. Regarding journaling, participants were required to recall their learning experiences of the previous academic year. Two analysts coded the data and then compared the codes of high- and low-achieving students. The third analyst reviewed the codes. Themes were identified iteratively, working towards comparing the learning processes of high- and low-achieving students.

Results

Data analysis revealed four themes—motivation and expectation, study methods, self-management, and flexibility of mindset. First, high-achieving students were more motivated and had higher academic expectations than low-achieving students. Second, high-achieving students adopted study planning and deep learning approaches, whereas low-achieving students adopted superficial learning approaches. Third, in contrast to low-achieving students, high-achieving students exhibited better time management and studied consistently. Finally, high-achieving students proactively sought external support and made changes to overcome challenges. In contrast, low-achieving students were less resilient and tended to avoid challenges.

Conclusion

Based on the theory of action, high-achieving students utilize positive governing variables, whereas low-achieving students are driven by negative governing variables. Hence, governing variable-based remediation is needed to help low-achieving students interrogate the motives behind their actions and realign positive governing variables, actions, and intended outcomes.

This study found four themes describing the differences between high- and low-achieving pre-clinical medical students: motivation and expectation, study methods, self-management, and flexibility of mindset.

Based on the theory of action approach, high-achieving pre-clinical medical students are fundamentally different from their low-achieving peers in terms of their governing variables, with the positive governing variables likely to have guided them to act in a manner beneficial to and facilitating desirable academic performance.

Governing variable-based remediation may help students interrogate the motives of their actions.

Key Messages

Introduction

Poor academic performance and failure are unfavourable outcomes that should be addressed as early as possible [Citation1–3]. A recent systematic review of international medical schools reported an attrition rate ranging between 2.4% and 26.2%, making for an average of 11.1% [Citation4]. Meanwhile, a Malaysian study reported that 2.1% to 12.1% (mean 5.3%) of Year 1 medical students enrolled at a public medical school failed to progress to the next stage of their studies [Citation5]. This situation is of particular concern insofar as public medical school training is substantially subsidized by the Malaysian government, with poor outcomes constituting a financial loss in a developing country. This expense is compounded by the fact that remediation for low-achieving students requires substantial time and resources from the educational institution. Moreover, low-achieving students in Malaysia have been found to suffer stress and depression [Citation6,Citation7]. As such, it is vital that medical educators guide students to excel to the best of their abilities.

A comparison of high- and low-achieving medical students may elucidate effective and ineffective learning processes as these students represent the extreme ends of academic achievement [Citation8–Citation10]. Several quantitative studies [Citation3,Citation8,Citation11–13] have sought to determine the factors that impact academic output by differentiating between high- and low-achieving students. Such research indicates that low-achieving students tend to demonstrate lower task value, self-efficacy, and self-discipline, and endure greater degrees of anxiety, frustration, and boredom. However, an in-depth qualitative investigation into the learning process—that is, a study employing multiple dimensions of how and why learning takes place [Citation14]—is required to explain the differences between high- and low-achieving students in this respect.

Some scholars have qualitatively examined academic failure [Citation15] and academic success [Citation16]. Their studies found that high-achieving students had high self-expectations, practiced deep learning approaches, and learned from their mistakes [Citation16]. In contrast, low-achieving students tended to set inappropriate self-expectations, adopt ineffective study methods, and normalize failure [Citation15]. However, different institutions have different admission criteria, curricula, teaching and learning activities, and forms of assessment—extraneous variables that may impact students’ academic achievement [Citation17]. Although the influence of extraneous variables can be mitigated by examining learning outcomes at the same institution, few qualitative studies have pursued this approach to exploring the differences between high- and low-achieving students. Moreover, qualitative studies that have examined students within a single institution, such as Todres et al. [Citation9] and Mirza and Usmani [Citation10], have focussed on intermediate and final-year students. Understanding the experiences of students in the early stages of their studies is important for elucidating early remediation [Citation1,Citation18], which can prevent cycles of failure [Citation18,Citation19]. Therefore, after recognizing the gaps in the literature and realizing that some students from our medical school fail while their peers succeed, we decided to explore the differences between the learning processes of high-and low-achieving pre-clinical medical students at the Universiti Malaya, Malaysia. Accordingly, the following research question guided this study:

How did the learning processes between high- and low-achieving students differ?

Methods

Study design and context

In order to conduct an in-depth exploration of the learning processes of high- and low-achieving students, this study adopted a qualitative instrumental case study design [Citation20]. More specifically, it constructed and compared two cases: high- and low-achieving students. A qualitative instrumental case study design was utilized because both cases demonstrate very distinct representations (i.e. outstanding achievement and marked failure) [Citation21]. Comparing these cases is intended to determine both effective and ineffective learning processes [Citation22].

This study was conducted at the Universiti Malaya, the oldest and highest-ranking public university in Malaysia, from September 2019 to July 2020. Ethical approval was obtained from the Universiti Malaya Research Ethics Committee (UM.TNC2/UMREC − 647), and written consent forms were obtained from all participants prior to the study.

In Malaysia, medical education entails a five-year undergraduate program. Top performing high school graduates (i.e. A-Level equivalent) typically enter medical school at the age of 19 or 20. Medical graduates are required to undergo mandatory two-year internships at public hospitals before obtaining their licences to practice medicine unsupervised. Gaining acceptance into the medical program is highly competitive. For admission to the Universiti Malaya, applicants are required to possess excellent high school examination results and perform well in both the BioMedical Admissions Test (BMAT) and multiple mini-interviews. Accordingly, the annual intake is approximately only 160 students, the majority of whom are 19 years old. The medical curriculum consists of two stages: a two-year pre-clinical medical stage and a three-year clinical stage. Additionally, curriculum content is horizontally and vertically integrated [Citation23]. Year 1 and Year 2 pre-clinical medical students share similar education environments, such as didactic lectures, interactive seminars, weekly clinical immersion programs, and problem-based learning sessions, whereas, Years 3, 4, and 5 clinical medical students undergo clinical rotations at the teaching hospital.

Theoretical approach

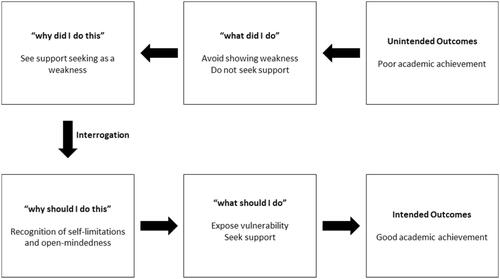

This study adopts a theory of action approach to examine the differences between high- and low-achieving first-year students at a Malaysian university. According to the theory of action approach, human actions are derived from mental variables that consciously or unconsciously govern respective actions [Citation24,Citation25]. These governing variables can be identified through actions or the rationales given for specific actions [Citation24,Citation25]. Actions are based on these governing variables and result in outcomes. Simply put, governing variables (i.e. “why did I do this?”) decide actions (i.e. “what did I do?”), and the actions decide outcomes (i.e. “what did I get?”).

In respect to academic success, the theory of action contends that positive governing variables (i.e. positive values like responsibility) lead to positive actions (e.g. consistency in studying), resulting in intended outcomes (i.e. success). In contrast, negative governing variables (i.e. negative values such as a lack of motivation) lead to negative actions (e.g. procrastination), resulting in unintended outcomes (i.e. failure) (). Academic success thus originates from the positive governing variables of high-achieving students, while academic failure is rooted in the negative governing variables of low-achieving students. Intended outcomes can be ensured by altering governing variables, thereby regulating actions [Citation26,Citation27]. As such, investigating the association between governing variables, actions, and outcomes can facilitate the identification and modification of one’s learning process [Citation18].

Figure 1. Theory of action [Citation24].

![Figure 1. Theory of action [Citation24].](/cms/asset/a9a16abd-cf5a-480f-987d-2c4017bc9260/iann_a_1967440_f0001_b.jpg)

By identifying the positive governing variables and actions of high-achieving students and correcting the negative governing variables and actions of low-achieving students enrolled in medical education, this study provides insights for the design of interventions intended to enhance academic success among medical students [Citation20].

Case selection

The selected medical school has pre-clinical assessments on the mastery of basic and clinical sciences knowledge (e.g. a written knowledge-based assessment and anatomy and pathology spot tests), clinical skills (e.g. objective structure clinical examination), public health (e.g. key feature questions), and professionalism (e.g. a reflective portfolio). The written knowledge-based assessment—that is, summative assessment—results are given as a numerical score, whereas the other types of assessment only indicate a satisfactory or unsatisfactory outcome. The written knowledge-based assessment consists of multiple-choice questions examining students’ understanding of normal and pathological human structures, functions, and behaviours relevant to a diagnosis, management plans, and the prevention of health problems in the integrated curriculum (e.g. musculoskeletal sciences, haematology, neurosciences, renal and urology). Students who fail any assessment are required to repeat the entire academic year.

This study selected cases based on assessment results for the 2019/2020 academic year. As students obtained satisfactory results in all assessments except the written knowledge-based assessment, cases were selected based on their performance in the knowledge-based assessment. This selection indicates that high achievement was confined to the cognitive domain. Based on their score in the written knowledge-based assessment, students were invited to a meeting at the beginning of the 2020/2021 year, where the researchers explained the aims, procedures, and measures of the study and ensured participant confidentiality.

Following this process, 31 students who scored in the ninetieth percentile in the written knowledge-based assessment were identified as high-achieving students [Citation28,Citation29] and invited to meet with the researchers, whereafter a total of 14 high-achieving students consented to participate in the study voluntarily. This process was repeated to recruit low-achieving students who scored in the tenth percentile of the knowledge-based assessment [Citation29,Citation30]; however, only 5 of 21 low-achieving students agreed to participate in the study.

Data collection

We collected data using reflective journals and semi-structured interviews. For the reflective journals, we used a Microsoft Word document template that contained a list of questions, with a text box provided for each question. The questions were designed according to Gibbs’ reflective cycle and intended to encourage participants to reflect on and describe their experiences in the previous academic year [Citation31]. Gibbs’ reflective cycle enables participants to recall and express their actions and feelings and engage in self-reflection; these details provide important insight into the learning process. Content validation was performed with three academicians, followed by face validation and a pilot study with students [Citation31]. Instructions emphasized that there was no right or wrong answer and encouraged students to express their genuine thoughts and feelings. The reflective journal formats for high- and low-achieving students were identical, except that the reflective journal for the former used the phrase “academic success,” while that for the latter used “unsuccessful attempt”; reflective journal formats are provided in Appendix 1. Participants received an empty template of the reflective journal via email and returned their completed reflective journals by replying to the sender, thereby ensuring confidentiality. Only the student support officer had access to these emails. All communications between individual students and the student support officer were private. Participants were allocated two weeks to complete their reflective journals.

Following the submission of the reflective journals, semi-structured one-to-one interviews were conducted. Guided by the theory of action approach, interview questions were developed to investigate what (i.e. actions) students did in their previous academic year and why (i.e. governing variables) (Appendix 2). The interviews were conducted in interview rooms at the researchers’ office. The interview rooms were quiet and private. The role of the interviewer was filled by the student support officer at the medical school. She was a medical graduate, who had received in-house training to offer academic performance and well-being support to medical students. The interviewer read the students’ reflective journals prior to the interview in order to obtain a general idea of the students and draft interview prompts. To build a good rapport with students and understand them better, the interviewer asked the students to share their family background and hobbies. Based on students’ initial responses, they were prompted with contingency questions to provide further clarification. Each interview lasted 60 to 80 min. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, producing a total of 164 pages for high-achieving students and 83 pages for low-achieving students.

Reflective journals and interviews complemented each other. First, important questions were repeated across methods to verify students’ learning approaches (e.g. “what did you do before attending teaching activities?” in the interview and “how did you prepare for the teaching session?” in the reflective journal). Second, the interviews sought further clarification on students’ responses in the reflective journals (e.g. “you mentioned trying to pay attention and writing notes; could you tell me what the process of writing notes involved?”), thereby aligning the reflective journals and interviews.

This study, including all data collection, was conducted in English. English is a compulsory subject in both primary and secondary education in Malaysia and is commonly used in daily communication. English is the medium of instruction in the medical program at the Universiti Malaya, with all students expected to be fluent in both written and spoken English.

Data analysis

This study employed thematic analysis to examine data. The thematic analysis comprises a set of procedures to identify and describe patterns in the data [Citation32]. This study used this approach because it is flexible and appropriate for studying students’ learning processes from different angles [Citation32,Citation33]. Steps proposed by Braun and Clark [Citation32] were used to analyze interview transcripts and reflective journals. After collecting the data, two analysts read the interview transcripts and reflective journals line-by-line multiple times in order to gain familiarity with the data and achieve contextual sensitivity [Citation21].

Reflective journals and interview transcriptions were saved as Microsoft Word documents and imported into QDA Miner Lite 2.0, a free computer-assisted qualitative analysis software program for analyzing textual data. Using QDA Miner Lite 2.0, two analysts independently searched and coded “what did students do?” and “why did they do this?” for Year 1 high-achieving students. Discussions were held to compare the initial codes and solve discrepancies. Using the agreed-upon codes, the two coders subsequently coded Year 2 high-achieving students. Discussions were held again to verify that there were no newly emergent codes. An identical coding process was applied to analyze Year 1 and Year 2 low achieving students.

Once all data were coded, the two analysts compared the codes of high- and low-achieving students. The two analysts were careful to avoid a priori fixed and polarized notions that there will be differences. The two analysts identified eight corresponding patterns; for example, “better time management” among high-achieving students corresponded with “poor time management” among low-achieving students. Subsequently, related patterns were fitted into a theme; for instance, the two patterns of “time management” and “consistency in studies” were categorized under the theme of “self-management.” As participants’ responses in interviews/reflective journals exposed their identities as high- or low-achieving students, the data could not be blinded. Therefore, the third analyst reviewed the coding results to minimize bias. All excerpts were reviewed to ensure that there was no bias in the selection of quotes. The three analysts deduced that data saturation had been achieved as codes were repeated among participants, with low-achieving students noting that they should have taken the actions practiced by high-achieving students [Citation34]. We used both data (reflective journals and interviews) and investigator (analysts) triangulation in this study [Citation35]. Triangulation is conducted to gain an understanding of a phenomenon by using different methods, or data, to examine the convergence of information and minimize bias [Citation36].

Results

Descriptive characteristics of participants

A total of 19 pre-clinical medical students participated in this study. These participants consisted of eight Year 1 students and eleven Year 2 students, the majority of whom were either 19 or 20 years old. Their demographics in terms of years of study, age, and gender are summarized in .

Table 1. Participants’ demographics.

Data analysis produced four themes: motivation and expectation, study methods, self-management, and flexibility of mindset.

Theme 1: Motivation and expectation

Intrinsic motivation

High- and low-achieving students exhibited differences in terms of intrinsic motivation and academic expectations. In respect to intrinsic motivation, high-achieving students expressed an interest in medicine, finding the study of the human body and mysteries of medicine fascinating. In contrast, low-achieving students doubted their decision to pursue a medical degree, exhibited little to no interest in medicine, and admitted to feeling lost and aimless in their studies. Low-achieving students also expressed feeling frustrated after observing students from non-medical degree programs have more time to engage in social activities and considered their medical degree a barrier preventing them from enjoying their favourite activities.

Academic expectations

In terms of academic expectations, high-achieving students set higher expectations for themselves in terms of academic outcomes, such as aiming to obtain the Dean’s Award and graduating on time. In contrast, low-achieving students had lower expectations and simply wanted to pass their exams. During the interviews, low-achieving students mentioned the need to set higher academic expectations.

Theme 2: Study methods

Study plan

High- and low-achieving students exhibited differences in their study methods, particularly in terms of planning their studies and their approach to learning. In regard to the former, high-achieving students planned their studies for upcoming weeks, including what they should prepare before attending classes and what to review after classes. By planning ahead, high-achieving students felt secure and calm ahead of classes or exams. In contrast, low-achieving students did not create systematic study plans ahead of time but acted according to their mood at the time. However, low-achieving students noted that they had prepared study plans for the 2020/2021 academic year, which helped them be more organized in their studies compared to the previous year.

Learning approach

In respect to the learning approach, high-achieving students attempted to comprehend the medical content by relating different learning topics with one another. For instance, if they learned a pre-clinical topic, they endeavoured to associate it with clinical practices. They thus avoided merely memorizing the medical content without comprehensively understanding and exploring the reasoning behind the body function mechanism. In contrast, low-achieving students adopted superficial learning, typically feeling satisfied with simply skimming or scanning the lecture notes with no clear objective. They also admitted to skipping topics they found less interesting.

Theme 3: Self-management

Time management

High- and low-achieving students exhibited two differences in terms of self-management, namely, time management and consistency of studying. First, high-achieving students demonstrated better time management than low-achieving students, allocating an appropriate amount of time for studies, friends, family, and relaxation. In contrast, low-achieving students tended to procrastinate studying for examinations until the last minute. However, during the interviews, low-achieving students recognized their lack of time-management skills and were determined to avoid procrastinating going forward.

Consistency

In respect to consistency of studying, high-achieving students studied consistently and kept up with the topics discussed in classes. They also repeatedly reviewed their lecture notes to ensure that they were mastering the knowledge and ability to apply it in the future. Although low-achieving students attempted to study consistently, they eventually gave up when the content became challenging. Low-achieving students thus lacked consistency in studying and tended to prioritize enjoying themselves rather than studying.

Theme 4: Flexibility of mindset

Exposure of vulnerability and support seeking

High- and low-achieving students exhibited two differences in the flexibility of their mindsets, specifically in terms of their exposure to vulnerability and willingness to seek support, and in their willingness to adapt to changes. First, when facing academic and emotional challenges, high-achieving students regularly turned to their peers and family members for support, who encouraged them to strive for better results. In contrast, low-achieving students were reluctant to show weakness to those around them, tending to believe that neither their family members nor peers would understand their struggles and potentially invalidate them. However, during the interviews, low-achieving students claimed to have changed their mindset regarding showing vulnerability and seeking support, acknowledging the importance of reaching out to family, friends, and lecturers when facing challenges. By seeking support from peers and lecturers, low-achieving students found themselves better equipped to face challenges in their studies.

Willingness to adapt to changes

With respect to students’ willingness to adapt to change, high-achieving students recalled trying a variety of study methods until they identified the most suitable method for medical studies. In this regard, they noted changing their duration of the study, approach to revision, and use of technology to improve the effectiveness of their studying. In contrast, low-achieving students continued using the same study method despite realizing that it was ineffective. Low-achieving students appeared less resilient and more likely to avoid challenges.

Discussion

Based on the qualitative data from a small number of students, this study indicated that high-achieving students exhibited greater degrees of motivation and self-expectation, more effective study methods, better self-management, and more flexible mindsets compared to their low-achieving peers. These differences can be explained using a theory of action framework, which contends that positive actions increase the likelihood of attaining favourable academic achievements. This section discusses this study’s theoretical and practical implications, as well as its limitations.

Theoretical implications

The findings of this study correspond with those of the existing literature. Like previous studies [Citation3,Citation10,Citation16,Citation37], the high-achieving students examined in this study adopted deep learning methods (i.e. methods intended to facilitate an understanding of the content rather than rote memorization) and study consistently. Previous studies also reported that high-achieving students had better class attendance [Citation38], demonstrated better self-discipline when managing their studies [Citation12,Citation13], and showed a willingness to work hard [Citation13]. In addition to using failure as a motivation to improve, high-achieving students tended to learn from their mistakes and were willing to change [Citation3]. They also attributed their academic achievements to the student support received from the medical school [Citation10,Citation16]. The findings of this study also correspond to previous studies demonstrating the relationships between actions and outcomes [Citation8,Citation11,Citation15,Citation39,Citation40]. Although high-achieving students did not use the term “governing variable,” they were likely to be governed by intrinsic motivation [Citation3], a sense of responsibility for themselves and patients, recognition of their own limitations, and open-mindedness. These positive governing variables are fundamental to the intended outcomes for students [Citation25].

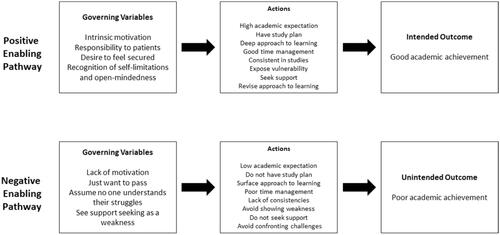

Correspondingly, negative governing variables may have guided students to act in a way that negatively impacted their academic outcomes [Citation25]. Similar to prior studies, the low-achieving students examined in this study were found to lack concrete motivations to pursue a medical degree and typically “just wanted to pass” [Citation15]. Consequently, these students exhibited low academic expectations [Citation9], adopted a superficial learning approach [Citation15], demonstrated poor time management [Citation15], and did not study consistently [Citation11,Citation41]. Moreover, as they considered needing support a sign of weakness, low-achieving students rarely sought help and tended to avoid confronting challenges [Citation15]. Failure to seek help may result in higher degrees of stress due to an inability to cope with challenges [Citation9,Citation10]. This study found similar negative actions among low-achieving students that led to procrastination and an acceptance of undesirable outcomes [Citation24,Citation25]. illustrates the differences in the learning processes of high- and low-achieving students from a theory of action perspective.

Figure 2. Differences in learning processes between high- and low-achieving students from the Theory of Action perspective.

The similarity between the results of this study and those of previous research indicates similar characteristics of high- and low-achieving students across national contexts. Malaysian students are not alone in respect to the challenges of excelling in medical studies. As such, international collaboration and the sharing of resources between medical schools may prove invaluable to address this common issue.

Practical implications

The findings of this study have important practical implications as they demonstrate the value of effective remediation for early-stage medical students underpinned by a theory of action approach. This result is particularly important insofar as remediation should be extensively mapped into a learning theory to ensure sound design [Citation42]. Indeed, this study actively recruited pre-clinical medical students as participants in order to identify the need for remediation at an early stage of learning. Early remediation is essential to reducing the risk of academic failure and cycles of failure [Citation18].

More specifically, this study proposes governing variable-based remediation. Per , this remediation is intended to guide low-achieving students to shift from a Negative Enabling Pathway to a Positive Enabling Pathway. It is imperative that the Negative Enabling Pathway be identified and eliminated. By replacing negative governing variables with positive governing variables, students will be empowered to act proactively and identify positive actions to achieve an intended outcome. Indeed, the appropriate learning approach has been shown to require less effort and lead to better results [Citation24,Citation25], making the proposed remediation more effective. For instance, if possessing positive governing variables, students will actively seek remediation, rather than passively waiting for remediation to be offered. This observation corresponds with the findings of Yip et al. [Citation39] that developing a self-motivated attitude is essential for academic success.

Through governing variable-based remediation, students can be taught to identify their own Negative Enabling Pathways and recognize the misalignment of negative governing variables and intended outcomes. They can subsequently work on developing a Positive Enabling Pathway to realign their governing variables and actions with their intended outcomes [Citation43]. Interrogating one’s governing variables is a process of detecting and correcting errors [Citation24,Citation44,Citation45], one achievable via guiding or self-reflection on one’s actions.

In this study, several low-achieving students informed the interviewer that they had made some changes similar to the actions of high-achieving students. Arguably, the process of reflecting on their previous year via journaling and the interview helped these students shift from a Negative Enabling Pathway to a Positive Enabling Pathway. However, this postulation remains preliminary and requires further evidence. In this respect, interventions involving the application of governing variable-based remediation are needed to evaluate and further develop the model proposed by this study. Such remediation could provide guided steps to help students identify, reflect on, and correct their governing variables [Citation46]. Guided reflection may be an appropriate first step of governing variable-based remediation, particularly as it can serve as a basis for an enabler diagnostic tool [Citation47] to support students and facilitators in identifying and eliminating negative governing variables. Although the result of unintended outcomes could be influenced by a plethora of factors, governing variable-based remediation will support the development of resilient and lifelong learners who are self-aware and able to adapt to any situation and context.

However, remediation is meaningless if students do not embrace it. In this study, the low achieving students failed to seek help when they needed it. This resistance to seeking help might be due to the effects of learned helplessness [Citation48] and impostor syndrome—soloist [Citation49]. To address their learned helplessness, low-achieving students could recall their experiences of previous successes and accomplishments to strengthen their convictions that further efforts can produce similar successes at medical school [Citation50]. Since soloists see help-seeking as a sign of failure, the governing variable-based remediation must be made non-threatening to students. Furthermore, the remediation should be actively proffered to students.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations as follows:

First, this qualitative instrumental case study was conducted at a single institution, indicating that the explanation illustrated in may not be generalizable. A description of the research site helps enhance the transferability of findings in qualitative studies [Citation51]. Accordingly, the findings of this study may be transferrable to other medical schools sharing similar characteristics. Nevertheless, future studies should consider a multi-institutional study with larger samples. This study constitutes an initial step, with future investigations recommended to consolidate and evaluate the model by collecting empirical evidence (). Quantitative experimental design or regression analyses may be useful in assessing the cause-and-effect relationship between governing variable-based remediation and academic performance.

Second, differences in the learning process are not the only explanation for academic success or failure. While the determinants of academic performance are multifactorial [Citation4,Citation40], this study could not investigate all possibilities. Some explanations lie beyond the learning process, including personal, social, family, health, and financial issues [Citation52,Citation53]. In this study, the participants’ socioeconomic backgrounds were not measured; however, this factor could have influenced their academic performance. For example, students whose parents are physicians could have experienced greater financial stability and received more guidance and advice concerning the challenges they might face in medical school. Additionally, further investigations are needed to understand why low-achieving students either are not able to seek help or feel uncomfortable doing it. Therefore, there is a need to identify students at risk of low academic achievement and to provide them with the necessary support.

Third, while one-time individual interviews were in-depth and practical, this may have condensed discussion of the learning processes that occurred over the year and overlooked some details. Future investigations should consider conducting follow-up interviews with participants.

Fourth, case selection was confined to cognitive acquisition (i.e., written knowledge-based assessment). The findings of this study do not explain students’ performance differences in other types of assessment, namely, attitudes and skills acquisition. Using similar methods to those employed in this study, future studies should consider investigating the differences in various types of assessment. Such research may prove useful in demonstrating the generalizability of differences between high- and low-achieving students in respect to the learning process.

Fifth, low-achieving students were less responsive to participating in this study despite receiving the same presentation of the study’s aim and procedures and being assured that all data were confidential. This low participation rate may be attributable to the fact that low-achieving students tend to be unwilling to share their experiences and feelings due to low self-esteem [Citation54]. In improving the participation rate of low-achieving students, future researchers may wish to consider building long-term relationships with students prior to conducting their research, encouraging participation by establishing trust and mutual understanding of how sharing learning experiences may benefit them. In this study, low-achieving students expressed similar comments, indicating redundancy and the interview data are rich. A systematic review of justifying sample size sufficiency in qualitative studies recognizes the aforementioned criteria for data saturation and sample adequacy [Citation55]. Furthermore, interview data were triangulated with reflective journal data. Future qualitative studies encountering low participation rates may wish to adopt the methodology demonstrated in this study to ensure the credibility of their data.

Finally, to be empathic and ethical, researchers did not request that high- or low-achieving students justify their decision not to participate in the study. Future studies may wish to investigate reasons for refusing to participate in such research, as this could aid in developing a better engagement plan.

Conclusion

Learning improvements for both high- and low-achieving pre-clinical medical students should be taken into consideration in order to review their governing variables, which, in turn, influence their learning processes. Furthermore, low-achieving pre-clinical medical students must interrogate the motives of their actions and realign their positive governing variables, actions, and intended outcomes.

Author contributions

CCF, VP, WHH, and JV were involved in the conception and design of the study. CCF, NLBG, and AJL were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data. CCF, NLBG, AJL were involved in the drafting of the manuscript. VP, WHH, and JV revised the manuscript critically. This version of the manuscript has been read and approved for publication by all authors. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from students.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Nurul Atira Khairul Anhar Holder, the student support officer for her contribution. We also wish to thank the students for participating in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets collected and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Yates J. Development of a 'toolkit' to identify medical students at risk of failure to thrive on the course: an exploratory retrospective case study. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):95.

- Maher BM, Hynes H, Sweeney C, et al. Medical school attrition-beyond the statistics a ten year retrospective study. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):13.

- Walke YS, Samuel LJ, Bandodkar LV. A cross-sectional comparative study to determine the factors contributing to the academic performance of the high performers and low performers in 2nd year medical students. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2015;4(6):1072–1079.

- O’Neill LD, Wallstedt B, Eika B, et al. Factors associated with dropout in medical education: a literature review. Med Educ. 2011;45(5):440–454.

- Holder NAKA. The hows and whys of academic failure among year 1 struggling students Kuala Lumpur. Malaysia: Universiti Malaya; 2020.

- Yusoff MSB, Pa MNM, Mey SC, et al. A longitudinal study of relationships between previous academic achievement, emotional intelligence and personality traits with psychological health of medical students during stressful periods. Educ Health. 2013;26(1):39–47.

- Melaku L, Mossie A, Negash A. Stress among medical students and its association with substance use and academic performance. J Biomed Educ. 2015;2015:1–9.

- Artino AR Jr, Hemmer PA, Durning SJ. Using self-regulated learning theory to understand the beliefs, emotions, and behaviors of struggling medical students. Acad Med. 2011;86(10 Suppl):S35–S8.

- Todres M, Tsimtsiou Z, Sidhu K, et al. Medical students’ perceptions of the factors influencing their academic performance: an exploratory interview study with high-achieving and re-sitting medical students . Med Teach. 2012;34(5):e325–e31.

- Mirza IA, Usmani A. Attribution to success and failure among medical students. Experience at Bahria University Medical and Dental College Karachi. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2017;6(67):890–898.

- Aleidi SM, Elayah E, Zraiqat D, et al. Factors affecting the academic performance of medical, dental, and pharmacy students in Jordan. Jordan J Pharm Sci. 2020;13(2):169–182.

- Lievens F, Coetsier P, De Fruyt F, et al. Medical students’ personality characteristics and academic performance: a five-factor model perspective . Med Educ. 2002;36(11):1050–1056.

- Khalil MK, Williams SE, Hawkins HG. The use of learning and study strategies inventory (LASSI) to investigate differences between low vs high academically performing medical students. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(1):287–292.

- Alexander PA, Schallert DL, Reynolds RE. What is learning anyway? A topographical perspective considered. Educ Psychol. 2009;44(3):176–192.

- Patel R, Tarrant C, Bonas S, et al. The struggling student: a thematic analysis from the self-regulated learning perspective . Med Educ. 2015;49(4):417–426.

- Abdulghani HM, Al-Drees AA, Khalil MS, et al. What factors determine academic achievement in high achieving undergraduate medical students? A qualitative study. Med Teach. 2014;36(sup1):S43–S8.

- Vergel J, Quintero GA, Isaza-Restrepo A, et al. The influence of different curriculum designs on students’ dropout rate: a case study. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1432963.

- Chou CL, Kalet A, Costa MJ, et al. Guidelines: the dos, don’ts and don’t knows of remediation in medical education. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(6):322–338.

- Casey PM, Palmer BA, Thompson GB, et al. Predictors of medical school clerkship performance: a multispecialty longitudinal analysis of standardized examination scores and clinical assessments. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):128– 128.

- Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. Vol. 5. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 4th ed. Saint Paul, MN: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2015.

- Christle CA, Jolivette K, Nelson CM. School characteristics related to high school dropout rates. Remedial and Special Education. 2007;28(6):325–339.

- Hays R. Integration in medical education: what do we mean? Educ Prim Care. 2013;24(3):151–152.

- Argyris C, Schon DA. Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1974. p. 224.

- Argyris C. Learning and teaching: a theory of action perspective. J High Educ Policy Manag. 1997;21(1):9–26.

- Argyris C. Action science and organizational learning. J Managerial Psych. 1995;10(6):20–26.

- Argyris C. Inner contradictions of rigorous research. California: Academic Press; 1980.

- Xiang Y, Dahlin M, Cronin J, et al. Do high flyers maintain their attitude?. Performance trends of top students. Washington D.C.: Thomas B. Fordham Institute; 2011.

- Loveless T, Parkas S, Duffett A. High-achieving students in the era of NCLB. Washington D.C.: Thomas B. Fordham Institute; 2008.

- Bromberg M, Theokas C. Breaking the glass ceiling of achievement for low-income students and students of color. Shattering expectations series. Washington, D.C: Education Trust; 2013.

- Holder NAKA, Sim ZL, Foong CC, et al. Developing a reflection guiding tool for underperforming medical students: an action research project. TJHE. 2019;7(1):115–163.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- King N. Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In: Catherine Cassell GS, editor. Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2004. p. 256.

- Varpio L, Ajjawi R, Monrouxe LV, et al. Shedding the cobra effect: problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Med Educ. 2017;51(1):40–50.

- Denzin NK. The research act: a theoretical introduction to sociological methods. New Jersey: Aldine Transaction; 2019.

- Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1189–1208.

- Ferguson E, James D, Madeley L. Factors associated with success in medical school: systematic review of the literature. BMJ. 2002;324(7343):952–957.

- Liles J, Vuk J, Tariq S. Study habits of medical students: an analysis of which study habits most contribute to success in the preclinical years. Med Ed Publish. 2018;7(1):61.

- Yip MC. Differences between high and low academic achieving university students in learning and study strategies: a further investigation. Educ Res Eval. 2009;15(6):561–570.

- Shukri AK, Mubarak AS. Factors of academic success among undergraduate medical students in Taif University, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Pharm. 2019;8(1):158–170.

- Hashim R, Hameed S, Ayyub A, et al. What went wrong: why did I fail. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2014;64(2):343–346.

- Cleland J, Leggett H, Sandars J, et al. The remediation challenge: theoretical and methodological insights from a systematic review. Med Educ. 2013;47(3):242–251.

- Greenwood J. The role of reflection in single and double loop learning. J Adv Nurs. 1998;27(5):1048–1053.

- Argyris C. Double-loop learning, teaching, and research. AMLE. 2002;1(2):206–218.

- Argyris C. Single-loop and double-loop models in research on decision making. Adm Sci Q. 1976;21(3):363–375.

- Denison AR, Currie AE, Laing MR, et al. Good for them or good for us? The role of academic guidance interviews. Med Educ. 2006;40(12):1188–1191.

- Synnott M. Reflection and double loop learning: the case of HS2. Teach Public Adm. 2013;31(1):124–134.

- Chaput de Saintonge DM. The helpless learner: a pilot study in clinical students. Med Teacher. 1998;20(6):583–586.

- Chandra S, Huebert CA, Crowley E, et al. Impostor syndrome: could it be holding you or your mentees back? Chest. 2019;156(1):26–32.

- Usher EL, Pajares F. Sources of self-efficacy in school: critical review of the literature and future directions. Rev Educ Res. 2008;78(4):751–796.

- Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):120–124.

- Hysenbegasi A, Hass SL, Rowland CR. The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2005;8(3):145.

- Joo S-H, Durband DB, Grable J. The academic impact of financial stress on college students. J College Student Retention: Res Theory Practice. 2008;10(3):287–305.

- Jouhari Z, Haghani F, Changiz T. Factors affecting self-regulated learning in medical students: a qualitative study. Med Educ Online. 2015;20(1):28694.

- Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, et al. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Method. 2018;18(1):1–18.