Abstract

Background

Established in 1992, the Norwegian Network for Personality Disorders (The Network) is a clinical research collaboration of specialist mental health and addiction services in Norway. Its primary focus is to facilitate systematic and relevant clinical assessment for patients with personality disorder and evaluate progress in psychotherapeutic treatment. However, large-scale data registers for personality disorder are still unique. This article presents the circumstances that led to the establishment of the Network, and its development and challenges in many areas, and through various phases.

Methods

In the following, we will outline how this close interaction between researchers, clinicians, and well-adapted systems has facilitated cooperation and clinical research. We will highlight some key factors that have been decisive during the network’s development, and not least for further adaptation and existence.

Results

Through 30 years, the Network has succeeded in establishing a large and sustainable clinical research collaboration with a persistent focus on personality disorder and psychotherapeutic treatment. The collaboration has resulted in a broad range of scientific contributions to the understanding of personality disorder, assessment and measurement methods, treatment alliance, clinical outcomes, service utilization, and costs. In addition, The Network has also resulted in a number of synergy effects that have benefited clinicians, patients, and researchers.

Conclusions

The Norwegian Network for Personality Disorders has become an acknowledged institution in the field. Many aspects of its development, organization, maintenance, and solutions to challenges may be relevant to others who plan to establish, maintain, or further develop similar collaborations.

Introduction

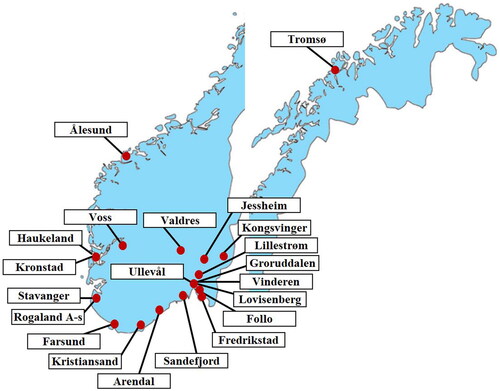

Research registers are increasingly established in clinical medicine and typically aim to aggregate large data sets, monitor clinical quality, treatment utility, and long-term developments. In contrast to controlled study designs, register-based research has the important asset of reflecting real-life clinical settings. One such is the Norwegian Network for Personality Disorders (The Network). On the year of its 30th anniversary, the Network is recognized as a uniquely well-established clinical research collaboration of treatment units specialized on treatment for patients with personality problems and disorders. The Network currently includes 21 treatment units within mental health and addiction services situated in all four health regions in Norway ().

Many aspects of the Network have been indirectly presented through a number of publications with clinical and or psychometric issues. In the following, we outline how this collaboration has developed and succeeded in establishing a large and sustainable clinical research network with a persistent focus on personality disorder (PD) and psychotherapeutic treatment. We will emphasize the close interactions between researchers, clinicians, and well-adapted systems facilitating data collection, positive synergies, and challenges in such clinical research collaboration. Some of this history will be unique to the Network, but many aspects of development, organization, maintenance, and solutions to challenges may be relevant to others who plan to establish, maintain, or further develop similar collaborations.

The Network was initiated in 1992 by a joint effort of researchers and clinicians across hospitals. Its establishment can be characterized as a ‘bottom-up’ process, and the emphasis on collaboration and communication has since then been a guiding principle. It originally included similar treatment units from three different hospitals (Ullevål Hospital, Akershus University Hospital, and Southern Norway Health Trust) and was at first entitled The Norwegian Network of Psychotherapeutic Day Hospitals [Citation1]. The aim was twofold; consolidate and support professional engagement for group-based treatments and PD, and implement standardized systems for clinical quality assurance and generation of research data. An anonymous research database was to be administered by Ullevål Hospital (today Oslo University Hospital). From the start, the collaboration introduced common procedures for clinical evaluation including both self-report instruments and semi-structured diagnostic interviews. The Network was open to include other hospitals and soon expanded. In parallel with the development of the Network and the increase in clinical data, the research group was also expanded and formalized.

Background factors

Several important background factors stimulated and facilitated the Network initiation. The preceding time period was generally characterized by a need for feasible alternatives to inpatient treatments. Time-limited psychotherapy programs fitted for patients with PD represented such a development and integrated traditions from group therapy, cognitive therapies, and therapeutic communities [Citation2]. A day hospital treatment program was implemented at Ullevål in 1978 [Citation3–5]. It was supported by a small but active research environment, and data collection for clinical research started at Ullevål in 1982, 10 years before the Network was established.

As a result of increasing interest in group-based treatment programs, a small group of Norwegian group therapists were trained by the Institute for Group Analyses (U.K.). This collaboration started in 1984, contributed to consolidate international contacts, resulted in further expanding interest for formal therapist qualification, and in 1992, the Norwegian Institute for Group Analysis (IGA) was founded. Group therapist training was from then on available for therapists in Norway. In contrast to other possibilities for psychotherapy qualification at the time, IGA training courses had an important asset of being open for health professionals across disciplines. Such improved access to education and clinical supervision represented substantial support for treatment programs in hospitals and mental health services across the country. It provided arenas for professional contact, consolidated a common theoretical approach and formal qualification, and facilitated development with local adjustments across the country. Several other hospitals developed day hospital programs inspired by Ullevål and group analyses, but by integrating, modifying, and adding elements according to local resources.

Ullevål Hospital had a defined research ambition, but with one single unit, data collection was nonetheless slow. However, the establishment of similar treatment units had rendered new possibility for collaboration across hospitals. A joint data aggregation could generate research more rapidly and improve statistical power [Citation6]. The strong research environment with expanding ambitions at Ullevål was a central background for the initiative to form the Network, and mutual professional engagement across hospitals was central motivations.

The Network received initial start-up funding from the Quality Assurance Committee of the Norwegian Medical Association (1994–1996). Since then, the Network has been funded by small annual fees of participating units, mainly to cover expenses for the general manager.

Treatment within the network

At the start, treatments were inspired by early studies from the Ullevål day unit and international research [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7,Citation8]. Time-limited programs were run by a multidisciplinary team of therapists and integrated psychodynamic group therapy (small and large groups) with other group-based interventions such as art therapy, body-awareness, and focused cognitive therapies. Step-down models introduced long-term outpatient group therapy after the more intensive time-limited day treatment [Citation9]. Today, several specialized treatments for PD are developed in outpatient formats [Citation10], and the Network aims to include a broad range of treatment approaches. Due to this development, the Network was renamed as The Norwegian Network for Personality Disorders in 2018. Although this new name refers to a specific diagnostic category, the Network has never limited its target group to those with a formal PD diagnosis. Many patients who are referred to units within the Network struggle with personality-related challenges without meeting the diagnostic threshold for a PD. Therefore, approximately 35% of the patients included in the Network’s central database do not have a formal PD diagnosis. However, since most of these patients have personality-related problems, they are offered the same treatment as those with PD. demonstrates current treatment approaches for patients referred to treatment in the period 2017–2022.

Table 1. Most common treatment approaches within the Network.

Main components of the Network collaboration

The Network has a simple organizational structure. In essence, it is run by two persons; the general manager (GM) and the senior adviser (SA), and each collaborates closely with the managers of the respective treatment units and members of the research group. The GM (first author) heads and maintains the Network collaboration and has done this since its establishment. For the first 23 years, Sigmund Karterud at Oslo University Hospital was SA of the Network. From 2015 Elfrida Kvarstein (last author) took over and is also the leader of the research group. In collaboration with the research group, the SA plans and organizes the different research projects from the Network Database. The SA also arranges regular meetings with the treatment units focusing on various clinical issues. Something that has been particularly beneficial for the Network is that the GM has a combination of competence within mental health research and system engineering and software programming. Usually, such expertise is represented by different people, which significantly increases the costs of development and maintenance.

In parallel with the development of the clinical collaboration, the research group was gradually established. As the research database grew, the data provided grounds for several doctoral theses, and many of these researchers are still associated with and actively participating in the research group. In addition, several researchers associated with various treatment units in the Network have joined the research group over the years. Today members are still recruited across hospitals and institutions, and clinicians from the Network interested in research can also participate. All research projects within the Network are supported and designed in collaboration with researchers from this group. Formally, the group is called Research Group for Personality Psychiatry and is affiliated with the University of Oslo.

A common, specialized computer system standardizes data collection and enables export to statistical applications. This specially designed system is a nucleus of the collaboration, incorporating all data on diagnostics and patient self-reports. The unique potential of using data systems to collect clinical data across different treatment units was recognized from the start. By this system, anonymous data from all units are combined and aggregated in a central database. In addition to serving the researchers with data, the system also serves leaders, clinicians, and patients with clinical information [Citation11–13]. Graphical profiles are easily generated, reflecting the patient’s current clinical status, development and alliance over time, and are suitable supplements to clinical evaluation and dialogue. Annually, all treatment units receive a standardized individual report of their activity, with comparisons to former years. The report comprises sociodemographic data on patients assessed, admitted and completed treatment, and characteristics such as diagnostics, user satisfaction, treatment outcomes (symptom distress and different aspects of social and personality functioning), and drop-out rates. However, these reports are only descriptive and since clinical data from each year within each unit are represented by somewhat few patients (n = 30–50), they only serve as trends to be monitored. More scientific analyses are conducted on the central database. However, these local reports may indicate areas in need of practice revision, improvements relative to former years, and arguments for reorganizing or supporting existing health services. For local health services, management implies balancing treatment quality against costs and available resources. The ability to document regular reviews of activity and clinical effects may thus render treatment units less vulnerable to budget cuts.

Regular contact between GM, clinicians, and researchers has been essential in the development of the Network. Logistics also require that local units (leaders, clinicians, and mercantile staff) have easy access to and regular contact with the GM. As this collaboration requires continuous updating of clinical competence, the Network arranges annual clinical conferences to unite and create common arenas for clinicians and researchers, providing updates on PDs, treatment interventions, and current research. Similarly, regular seminars focus on diagnostic assessment, use of clinical measures, as well as updates on computer software and registration routines. With the growing number of participating units and geographical distances, digital meetings are currently dominating. Furthermore, a close association to the research group is emphasized, as members of this group contribute in conferences and seminars.

Development and maintenance of the computer system

In the context of designing and revising the computer system for the Network, users are clinicians, mercantile staff, patients and researchers, and all may have different expectations, ambitions, or claims. User involvement is generally a guiding principle in all phases of system implementation [Citation14,Citation15]. Poor quality of the end product can be the result of misunderstandings, unrealistic expectations, or skepticism [Citation16,Citation17]. On all user levels, careful consideration and communication is therefore essential [Citation18–22]. In line with multiple reports on system implementation, it is also a core philosophy of the Network that developments and activities must balance interests of all relevant users.

When first initiating the Network collaboration, researchers, clinicians, and mercantile staff at each unit were actively involved. Here, clinical and practical utility of the system and selected assessment instruments was essential. Inspired by the methodology of Goal Directed Project Management [Citation23], details on research ambitions, clinical routines, resources, expectations, clinical competence, as well as experience with personal computers, were recorded by separate interviews at each unit. The placing of assessments needed to echo treatment phases, and in the first phase of the Network, assessments were applied in line with the structure of step-down treatment. Research based on the first 10 years of the Network reflects the structure in this period – at baseline and end of day hospital treatment, start and end of outpatient group therapy, in addition to 1- and 5-year follow-ups [Citation9,Citation24,Citation25].

Information system development is an ongoing process of evaluation and adaptation based on feedbacks from research, health service organization, clinicians, and patients. The system needs to adapt to shifting reality, and user involvement and contact on all levels is thus a never ending process [Citation26]. This form of development has also been evident in the Network throughout the years, especially where new clinical assessment methods or treatment modalities are introduced and require modification of practical routines. Thus, in line with a shift from day treatment programs to outpatient treatments, data collection shifted in 2009 to a longitudinal design more able to reflect treatment processes and change over time.

Updating processes have been important in order to keep the Network on track as a vital and relevant collaboration. When clinical routines are changed, the system needs to reflect these. If clinical instruments are found questionable due to psychometric limitations or lack of clinical relevance, they need to be removed or replaced. When users suggest improvements or new functionality of the computer system, such features are important to discuss.

Within the Network, the computer system has been revised approximately every 3–4 years, for various reasons. First, since the computer system serves as a clinical tool, most revisions were related to clinical utility and graphical presentations of individual profiles and clinical course. Second, the shift from day treatment to outpatient treatment entailed a change of routines for data collection. Third, several questionnaires were discontinued or replaced by new instruments. For instance, the Ward Atmosphere Scale [Citation27] was not relevant any longer because of day treatment was phased out. Another example is the Revised NEO-Personality Inventory [Citation28], which was replaced by the Severity Indices of Personality Problems [Citation29] because clinicians found this instrument more clinically relevant. Moreover, the Revised Symptom Checklist-90 [Citation30] had to give way to other more personality-related measures in 2017, such as the Toronto Alexithymia Scale 20 [Citation31], the Experiences in Close Relationships [Citation32], and the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale [Citation33].

Researchers and clinicians need to be familiar with each other’s work

As Friis [Citation34] points out, knowledge from empirical research should not only be implemented in clinical practice, ‘… it should be developed there’. (p.439). However, research projects solely decided by researchers may lack relevance for ordinary clinical practice, resulting in increasing distance and low clinical engagement [Citation35,Citation36]. Remote researchers may have unrealistic ambitions, applying instruments that require a lot of resources. Moreover, measurements lacking clinical relevance or are difficult to understand for patients and clinicians, challenge the feasibility and validity of the research. Furthermore, a collection of too much data is another pitfall. If research results are difficult to relate to clinical practice, they may remain unused by clinical leaders and policy decision-makers [Citation37]. Clinicians need to be familiar with ongoing research and how it addresses relevant clinical topics. Motivation is known to increase when there is some kind of reciprocity [Citation38], and it is a clear advantage if researchers are visible and available, explicitly linking research questions to clinical practice, and as in the Network, actively participating in regular clinical conferences and seminars.

Effective data collection is crucial

Data from continuous clinical research collaborations are based on routine assessments and may be particularly vulnerable to missing data [Citation39]. With a partly paper-based data collection, logistic challenges are evident – such as ensuring that forms are distributed to therapists and patients at the right time, collecting and registering the filled-in forms, and distributing the feedback to clinicians in the form of graphical profiles. Routines are especially vulnerable in periods of high working-load and organizational changes. In order to prevent the accumulation of problems with negative, increasingly distressing cycles or disengagement, it is important to establish regular contact with the leaders and clinicians. It is also important not to blame the clinicians for not following routines, but rather to acknowledge their situation, address the difficulties, and calmly motivate them to get back on track. In the long run, the alliance and cooperation is more important than some occasionally missing data.

A main challenge in data collection within the Network has been particularly related to retrieving data at the end of treatment. According to clinicians in the Network, routines and motivations for distributing and completing questionnaires could be difficult for some in this phase. The implementation of repeated assessments every 6 months is a more complicated design [Citation39], but nonetheless provided opportunity for more measurement occasions and thereby less strain on the last assessment, and better overall utilization of data. The challenges related to missing data from routine assessments might be partly resolved by automation, for example by digitizing the management of data collection.

Digital assessment systems are frequently and increasingly used in research and may save considerable logistics of data collection. In Norway digital systems are currently also being introduced as clinical routines within mental health services. Patients are requested to fill in self-report questionnaires by mobile phone or tablet, and their scores are directly imported to their electronic journals. General implementation of such systems across the country takes time, but will imply standardization of digital infrastructure, data protection, data collection, and electronic statements of consent. For the Network, this development will facilitate a full transition of the current computer-based system to complete digital systems for all participating units and will represent a radical simplification of the data collection.

Despite clear advantages, introduction of digital assessment instruments may also have some uncertainties. When patients are physically given a booklet with questions and informed about the importance and purpose of the assessment, they can sit back and relax, hold on to it, look through it, and in many ways own it. They may be disturbed when filling in the form, but can easily continue later. Today, the booklet of questionnaires used in the Network is around 20 pages long. It covers a wide range of relevant clinical aspects related to PD, mental symptoms, life quality and social adaptation, emotional and relational personality functioning, traumatic exposures, alcohol and substance use, self-destructive behaviors, as well as measures of treatment satisfaction and alliance. A data collection of this magnitude may be more tiresome to complete in a digital format. This will certainly challenge researchers and clinicians when selecting more specialized and comprehensive questionnaires in addition to more generic clinical measures.

Synergies of the network

Over 30 years, the Network collaboration has resulted in a large and continuously increasing research database, comprising longitudinal clinical data with unique detail on PD. As far as we know, there is no clinical database that can be compared to the current size of the one the Network possesses. Data from the Network has been basis for several doctoral theses, masters and specialist theses, and numerous scientific papers. However, research is only one of three concrete main results of this collaboration. The second is the development of a professional community related to the understanding and treatment of patients with personality-related problems and disorders, while the third is the availability of a clinical tool to ensure quality of clinical assessments, treatment alliance, and treatment course. The first studies based on Network data indicated that the clinical research collaboration in general represented benefits at the individual patient level [Citation12], the unit level [Citation11], and a general health care level [Citation13]. Moreover, different treatment components could be evaluated [Citation40–43], and overall treatment outcomes explored [Citation9,Citation24].

Indirectly, the collaboration has led to a number of additional gains and opportunities that were not initially intended. Examples of these are described below, including the establishment of more separate groups of researchers with focus on specific research areas, such as the NorAMP and NONSTOP-GEN projects.

Taking consequences of own research

If research results are difficult to understand or apply in practice, they may remain unused by clinical managers and decision-makers [Citation37]. Clear communication of research results is therefore crucial for whether the research leads to positive changes. Close collaboration between clinicians and researchers may increase willingness to take consequences of research outlining less favorable results. In the Network, research led to more discussions on treatment formats and patient suitability. Studies indicated that day hospital treatment intensity could be shortened to fewer days per week [Citation9], and that the short-term day hospital program was less suitable for poorly functioning patients with borderline PD [Citation44]. The transition from the day hospital phase to long-term outpatient group therapy was difficult for vulnerable patients who dropped out of treatment [Citation45]. Accumulation of clinical research results in the Network and results from a randomized controlled trial conducted within one of the Network units led to a shift from first recommending step-down treatment models to focusing more on outpatient treatments [Citation46,Citation47]. From 2008 specialized PD approaches such as Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT) were increasingly introduced for patients with borderline PD and studies confirmed promising benefits [Citation48–53].

Identifying areas in need of knowledge development

The Network database has provided grounds for research on the less-studied condition, avoidant PD. Studies from the Network have identified poor functioning and high distress levels in this patient group, on level with borderline PD, and poorer results of treatment processes based on long-term outpatient group therapy [Citation24,Citation25,Citation54]. Further research collaborations have explored this disorder with a focus on social anxiety, childhood neglect, attachment, and alexithymia [Citation55–58], longitudinal course of functioning [Citation59] as well as qualitative aspects [Citation60–62]. In 2017 a research network for avoidant PD was established, sharing experiences and aiming to facilitate treatment research. The magnitude of data accumulated within the Network over years has enabled research on a range of PD conditions, including also rare conditions, such as schizoid, schizotypal, narcissistic, histrionic, and antisocial PD [Citation63–67].

Quick access to large datasets

Multicenter collaborations may speed up research. A recent example is a study initiated within the Network after the close-down of services due to the Covid-19 pandemic, where 12 units and the research group joined forces for a survey among the patients. Under a year after, two articles were published [Citation68,Citation69]. Other synergy examples include when physical therapists across Network units collaborated to create a questionnaire measuring bodily experience [Citation70], or when units collaborated in a study of patient–therapist and therapist–therapist agreement on interpersonal problems [Citation71], or when the units collaborated in a reliability study of the Global Assessment of Functioning scale [Citation72]. All these studies were conducted parallel to ordinary clinical routines.

The Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Personality Psychiatry

When it comes to professional collaboration and the sharing of information, it has primarily been people connected to the Network, including patients, who have benefited from this. In order to reach out more widely in society and the healthcare system, far more resources are required. The Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Personality Psychiatry (NAPP) was formally established in 2012 to build and spread expertise in the assessment and treatment for people with PDs. The allocation of this expansion to the section for Personality Psychiatry, Oslo University Hospital, was largely based on the professional research environment and cross-regional contacts built up over time through the Network collaboration. NAPP today organizes user-groups, courses, and conferences on PD and assessment. Its advisory function addresses patients, relatives, health professionals, and authorities. A further spin-off within NAPP is the Quality Laboratory for Psychotherapy (The Lab), established in 2013 as a supervisory service aiding clinicians and researchers by assessing therapist fidelity to MBT [Citation73,Citation74]. In collaboration with the Lab, the Network arranges MBT-inspiration seminars twice a year – as a supervisory seminar, discussing different therapeutic challenges.

Biobank

In line with cheaper and better biotechnology, the focus on mental health and genetics has increased considerably. In 2007 the Norwegian Network Study of Personality and Genetics (NONSTOP-GEN) was established within the Network, including participating patients from five treatment units and a collaboration with the Norwegian Centre for Mental Disorders Research (NORMENT). NONSTOP-GEN is a general bio-bank that aims to identify the genetic basis of PDs. In 2020, NONSTOP-GEN joined the «International Borderline Genomics Consortium», which recently has conducted a genome-wide association study on borderline PD [Citation75].

Diagnostic assessment of PD

With respect to diagnosing PD, the Network adheres to section II of the DSM-5, using the SCID-5-PD to assess these diagnoses [Citation76,Citation77]. More recent revisions of classification systems for PD, both within the DSM- and European ICD-systems, are not yet implemented in Norway. However, in association with the Network, a separate research group established the Norwegian Multicenter Study of the DSM-5 Alternative Model for Personality Disorders (NorAMP) conducting research on the validity and psychometric properties of the AMPD-model of DSM-5 [Citation78].

Challenges

The new proposed changes in PD classification of the ICD-11 [Citation79] involve major changes for clinicians and researchers, representing both opportunities but also some great challenges [Citation80]. The future classification of PD within research is still uncertain, but it will most likely be based more on dimensional models than on categorical classifications. Within clinical research collaborations rapid accumulation of data can speed up evidence of validity and utility of such changes.

Missing data is always a challenge to research. Even well designed or organized, a range of challenges affecting management, coordination, co-operations, and data collection will occur. The most vulnerable part of the chain is the practical aspect of data collection. That is, keeping stable routines.

Conflicts within hospitals or treatment units or controversies among clinicians may inflict the clinical environment, treatment quality, and also hamper research collaborations. Such environmental aspects may also impact collaboration in the Network. Over the years controversies among clinicians have e.g. included unwillingness to diagnose PDs, to use psychological assessment instruments, or unwillingness to provide reputable, evidence-based treatment. Ensuring that the Network provides regular arenas for communication and discussion between units/unit leaders is helpful, since many face similar problems and can contribute with constructive feedback. Some controversies may make research collaboration impossible, but generally, management of clinical research collaborations is a process requiring reflection, patience, openness, and humility. It is also essential to have support from local health service leaders who appreciate the Networks’ target group, aims for combining treatment and research, and are willing to prioritize this activity within the organization.

Changes in the organization of mental health services may challenge research collaborations by imposing increased administrative work load within the units or disturbing the structure and focus of the research. It is therefore important that the Network collaboration with its systems and research designs is flexibly adjusted to new requirements. During the last 30 years, mental health services in Norway have undergone several reorganizations, from increasing establishment of outpatient clinics, fusion of smaller hospitals to larger health trusts, and the introduction of New Public Management (2002). Later developments include rights to health care for defined patient groups/conditions (2005), and implementation of standard treatment packages with given evaluation points (2019). During processes of health service reorganizations, small treatment units or teams are particularly vulnerable to discontinuation. Altogether, 35 treatment units have joined the Network since its establishment. Among these, 15 have withdrawn over time. One unit was merged with another, one was withdrawn due to lack of technological resources, and three were closed for financial reasons. Further 10 units were closed or dissolved due to reprioritization of treatment options or major reorganizations, of which one has rejoined.

Conclusions

Over the years, patients, clinicians, and researchers have engaged in evaluating PD treatment, and by this joint effort, the Norwegian Network for Personality Disorders has become an acknowledged institution in the field. With its adaptive capacity, it has survived 30 years with developments and changes in theoretical, clinical, legal, and technological areas. The research has contributed to the understanding of PD, led to several revisions of treatment programs, and assessment of clinically important PD features. Our experience is that the unique close proximity of system, clinical, and research competence as well as regular contact with clinicians and users within the Network creates a positive synergy, ensuring continued relevance of all collaborative efforts. We hope this summary and review of experiences can inspire researchers and clinicians alike and help them in identifying opportunities and challenges in similar long-term projects.

Notes on contributors

Geir Pedersen, (MA, PhD) is leader of the Norwegian Network for Personality Disorders at Section for Personality Psychiatry and Specialized Treatments, Oslo University Hospital. He is an active researcher, and specializes in clinical research on personality disorder, assessment methods, clinical quality systems and psychometrics.

Theresa Wilberg is a professor of psychiatry at University of Oslo and senior researcher at Oslo University Hospital. She has published several scientific articles and book chapters within the field of personality psychiatry, and has co-authored a textbook on personality psychiatry and a book on avoidant personality problems.

Benjamin Hummelen, (MD, PhD) is senior researcher at the Department of Research and Innovation, Division of Mental Health and Addiction, Oslo University Hospital. He is the principal investigator of the Norwegian Study of the DSM-5 Alternative Model for Personality Disorders and has published numerous papers on the clinical utility and validity of this new model.

Elfrida Hartveit Kvarstein, (MD, PhD) is head senior consultant at Section for Personality Psychiatry and Specialized Treatments, Oslo University Hospital and associate professor at the University of Oslo (UiO). She is leader of the Research group for Personality Psychiatry, UiO and specializes in clinical research on personality disorder.

Acknowledgments

We highly acknowledge Professor Sigmund Karterud for his groundbreaking work for group treatment in Norway, and for his innovative contribution to the Network, both as initiator and chief advisor during 23 years. With his countless publications and lectures, Karterud has been a great source of inspiration for the Network as well as for similar clinical research collaborations, not only in Norway but also internationally.

We would also like to express our gratitude to all the 35 treatment units which in the last 30 years have been connected to the Network. The good cooperation between these, and between them and the research group, has been decisive for the large-scale implementation of treatment for patients with personality disorders in Norway.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Not applicable as no data have been used.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Karterud S, Pedersen G, Friis S, et al. The Norwegian network of psychotherapeutic day hospitals. Ther Communities. 1998;1:15–28.

- Rosie JS. Partial hospitalization: a review of recent literature. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1987;38(12):1291–1299.

- Karterud S. The primary task of open heterogenous groups in a therapeutic community. J Oslo City Hosp. 1981;31:71–74. PMID7320792

- Karterud S, Vaglum S, Friis S, et al. Day hospital therapeutic community treatment for patients with personality disorders: an empirical evaluation of the containment function. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180(4):238–243.

- Vaglum P, Friis S, Irion T, et al. Treatment response of severe and nonsevere personality disorders in a therapeutic community day unit. J Personal Disord. 1990;4(2):161–172.

- Piper WE. Psychotherapy research in the 1980s: defining areas of consensus and controversy. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(10):1055–1063.

- Budman SH, Demby A, Soldz S, et al. Time-limited group psychotherapy for patients with personality disorders: outcomes and dropouts. Int J Group Psychother. 1996;46(3):357–377.

- Piper WE, Rosie JS, Azim HF, et al. A randomized trial of psychiatric day treatment for patients with affective and personality disorders. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(8):757–763.

- Karterud S, Pedersen G, Bjordal E, et al. Day hospital treatment of patients with personality disorders. Experiences from a Norwegian treatment research network. J Personal Disorders. 2003;17(3):243–262.

- Storebø OJ, Stoffers-Winterling JM, Völlm BA, et al. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5:CD012955.

- Karterud S, Wilberg T, Pedersen G, et al. Quality assurance of psychiatric day hospital treatment. II: ward level. Nordisk Psykiatrisk Tidsskrift. 1998;52(4):327–335.

- Urnes Ø, Karterud S, Pedersen G, et al. Quality assurance of psychiatric day hospital treatment. I: individual level. Nordisk Psykiatrisk Tidsskrift. 1998;52(3):251–262.

- Wilberg T, Karterud S, Pedersen G, et al. Quality assurance of psychiatric day hospital treatment. III: health care system level. Nordisk Psykiatrisk Tidsskrift. 1998;52(5):431–439.

- Harris MA, Weistroffer HR. A new look at the relationship between user involvement in systems development and system success. Commun Assoc Inf Syst. 2009;24:739–756.

- Hwang MI, Thorn RG. The effect of user engagement on system success: a meta-analytical integration of research findings. Inf Manag. 1999;35(4):229–236.

- Bano M, Zowghi D. A systematic review on the relationship between user involvement and system success. Inf Softw Technol. 2015;58:148–169.

- Kujala S. User involvement: a review of the benefits and challenges. Behav Inf Technol. 2003;22(1):1–16.

- Baronas AK, Louis MR. Restoring a sense of control during implementation: how user involvement leads to system acceptance. MIS Q. 1988;12(1):111–126. https://www.jstor.org/stable/248811

- Barki H, Hartwick J. Rethinking the concept of user involvement. MIS Q. 1989;13(1):53–63.

- Maurish ME. Introduction. In: Maurish ME, editor. Handbook of psychological assessment in primary care settings. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 2000. p. 3–41.

- Zeffane R, Cheek B, Meredith P. Does user involvement during information systems development improve data quality? Hum Syst Manag. 1998;17(2):115–121.

- Howcroft D, Wilson M. Paradoxes of participatory practices: the Janus role of the systems developer. Inf Organ. 2003;13(1):1–24. (02)00023-4

- Andersen ES, Grude KV, Haug T. Goal directed project management: effective techniques and strategies. 4th ed. London (UK): Kogan Page Publishers; 2009. ISBN 0749457554, 9780749457556

- Wilberg T, Karterud S, Pedersen G, et al. Outpatient group psychotherapy following day treatment of patients with personality disorders. J Pers Disord. 2003;17(6):510–521.

- Kvarstein E, Karterud S. Large variations of global functioning over five years in treated patients with personality traits and disorders. J Pers Disord. 2012;26(2):141–161.

- Rai A, Lang SS, Welker RB. Assessing the validity of IS success models: an empirical test and theoretical analysis. Inf Syst Res. 2002;13(1):50–69.

- Moos RH. Ward atmosphere scale manual. 3rd ed.. Palo Alto (CA): Mind Garden; 1996.

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO five factor inventory (NEO-FFI), Professional Manual. Odessa (FL): Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1992.

- Verheul R, Andrea H, Berghout CC, et al. Severity indices of personality problems (SIPP-118): development, factor structure, reliability, and validity. Psychol Assess. 2008;20(1):23–34.

- Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R: symptom checklist-90-R: administration, scoring and procedures manual. Minneapolis (MN): National Computer Systems; 1994.

- Bagby RM, Parker JDA, Taylor GJ. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia scale—I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38(1):23–32.

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: an integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 1998. p. 46–76.

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26(1):41–54.

- Friis S. How to help clinically relevant research survive? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132(6):439–440.

- Sundet R. Forsker og terapeut - sammenfletting av roller som grunnlag for en forskende klinisk praksis. TPH. 2014;11(1):35–43.

- Callaghan P, David A, Lewis S, et al. Developing support for mental health clinical research: the Mental Health Research Network experience. Clin Invest. 2012;2(5):459–463.

- Stewart R. Mental disorders and mortality: so many publications, so little change. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132(5):410–411.

- Kopelman S. Tit for tat and beyond: the legendary work of Anatol Rapoport. Negotiation Confl Manage Res. 2020;13(1):60–84.

- Clark DM, Layard R, Smithies R, et al. Improving access to psychological therapy: initial evaluation of two UK demonstration sites. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47(11):910–920.

- Johns S, Karterud S. Guidelines for art group therapy as part of day treatment program for patients with personality disorders. Group Anal. 2004;37(3):419–432.

- Karterud S, Pedersen G. Short-term day hospital treatment for personality disorders: benefits of the therapeutic components. Ther Communities. 2004;25:43–54.

- Karterud S, Urnes Ø. Short-term day treatment programs for personality disorders. What is the optimal composition? Nord J Psychiatry. 2004;58(3):243–249.

- Leirvåg H, Pedersen G, Karterud S. Long-term continuation treatment after short-term day treatment of female patients with severe personality disorders: body awareness group therapy versus psychodynamic group therapy. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64(2):115–122.

- Kvarstein E, Karterud S, Pedersen G. Treatment course of the most severe borderline patients in the Norwegian Network of Psychotherapeutic Day Hospitals. Ther Communities. 2004;25:120–130.

- Hummelen B, Wilberg T, Karterud S. Interviews of female patients with borderline personality disorder who dropped out of group treatment. Int J Group Psychother. 2007;57(1):67–91.

- Arnevik E, Wilberg T, Urnes Ø, et al. Psychotherapy for personality disorders: 18 months’ follow-up of the Ullevål Personality Project. J Pers Disord. 2010;24(2):188–203.

- Gullestad F, Wilberg T, Klungsøyr O, et al. Is treatment in a day hospital step-down program superior to outpatient individual psychotherapy for patients with personality disorders? – results from a randomized clinical trial comparing different modalities. Psychother Res. 2012;22(4):426–441.

- Kvarstein EH, Pedersen G, Urnes Ø, et al. Changing from a traditional psychodynamic treatment programme to mentalization-based treatment for patients with borderline personality disorder – does it make a difference? Psychol Psychother. 2015;88(1):71–86.

- Kvarstein EH, Pedersen G, Folmo E, et al. Mentalization-based treatment or psychodynamic treatment programs for patients with borderline personality disorder - the impact of clinical severity. Psychol Psychother. 2019;92(1):91–111.

- Morken KTE, Binder P-E, Arefjord NM, et al. Mentalization based treatment from the patients’ perspective–what ingredients do they emphasize? Front Psychol. 2019;10:1327.

- Morken KT, Karterud SW. Mentalization-Based Group Therapy (MBT-G) in a pilot study of female personality disordered and substance-abusing patients. Gruppenpsychotherapie Und Gruppendynamik. 2019;55(3):183–205.

- Ditlefsen IT, Nissen-Lie HA, Andenaes A, et al. “Yes, there is actually hope!” — a qualitative investigation of how patients experience mentalization-based psychoeducation tailored for borderline personality disorder. J Psychother Integration. 2021;31(3):257–276.

- Folmo EJ, Stänicke E, Johansen MS, et al. Development of therapeutic alliance in mentalization-based treatment—goals, bonds, and tasks in a specialized treatment for borderline personality disorder. Psychother Res. 2021;31(5):604–618.

- Wilberg T, Karterud S, Pedersen G, et al. The impact of avoidant personality disorder on psychosocial impairment is substantial. Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(5):390–396.

- Eikenaes I, Hummelen B, Abrahamsen G, et al. Personality functioning in patients with avoidant personality disorder and social phobia. J Pers Disord. 2013;27(6):746–763.

- Eikenaes I, Egeland J, Hummelen B, et al. Avoidant personality disorder versus social phobia: the significance of childhood neglect. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0128737.

- Eikenaes I, Pedersen G, Wilberg T. Attachment styles in patients with avoidant personality disorder compared with social phobia. Psychol Psychother. 2016;89(3):245–260.

- Simonsen S, Eikenaes IU-M, Bach B, et al. Level of alexithymia as a measure of personality dysfunction in avoidant personality disorder. Nord J Psychiatry. 2021;75(4):266–274.

- Kvarstein EH, Antonsen BT, Klungsøyr O, et al. Avoidant personality disorder and social functioning: a longitudinal, observational study investigating predictors of change in a clinical sample. Personal Disord. 2021;12(6):594–605.

- Sørensen KD, Wilberg T, Berthelsen E, et al. Lived experience of treatment for avoidant personality disorder: searching for courage to be. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2879.

- Sørensen KD, Råbu M, Wilberg T, et al. Struggling to be a person: lived experience of avoidant personality disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(4):664–680.

- Pettersen MS, Moen A, Børøsund E, et al. Therapists’ experiences with mentalization-based treatment for avoidant personality disorder. Eur J Qual Res Psychotherapy. 2021;11:143–159. https://ejqrp.org/index.php/ejqrp/article/view/126

- Hummelen B, Pedersen G, Wilberg T, et al. Poor validity of the DSM-IV schizoid personality disorder construct as a diagnostic category. J Personal Disord. 2015;29(3):334–346.

- Hummelen B, Pedersen G, Karterud S. Some suggestions for the DSM-5 schizotypal personality disorder construct. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(4):341–349.

- Karterud S, Øien M, Pedersen G. Validity aspects of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, narcissistic personality disorder construct. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(5):517–526.

- Bakkevig JF, Karterud S. Is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, histrionic personality disorder category a valid construct? Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(5):462–470.

- Paap MCS, Braeken J, Pedersen G, et al. A psychometric evaluation of the DSM-IV criteria for antisocial personality disorder: dimensionality, local reliability, and differential item functioning across gender. Assessment. 2020;27(1):89–101.

- Kvarstein EH, Zahl KE, Stänicke L, et al. Vulnerability of personality disorder during the Covid-19 crises – a multicenter survey of treatment experiences among patients referred to treatment. Nord J Psychiatry. 2022;76(1):52–63.

- Kvarstein EH, Zahl KE, Stänicke L, et al. Vulnerability of personality disorder during Covid-19 crises - a multicenter survey of mental and social distress among patients referred to treatment. Nord J Psychiatry. 2022;76(2):138–149.

- Pedersen G, Tybring-Petersen K, Tønder M, et al. Spørreskjema for måling av kroppsopplevelse. Tidsskrift for Norsk Psykologforening. 2013;50:992–998. https://psykologtidsskriftet.no/fagartikkel/2013/10/sporreskjema-maling-av-kroppsopplevelse

- Pedersen G, Hagtvet KA, Karterud S. Interpersonal problems: self-therapist agreement and therapist consensus. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(3):308–317.

- Pedersen G, Hagtvet KA, Karterud S. Generalizability studies of the global assessment of functioning (GAF) - split version. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(1):88–94.

- Folmo EJ, Karterud SW, Bremer K, et al. The design of the MBT-G adherence and quality scale. Scand J Psychol. 2017;58(4):341–349.

- Karterud S, Pedersen G, Engen M, et al. The MBT Adherence and Competence Scale (MBT-ACS): development, structure and reliability. Psychother Res. 2013;23(6):705–717.

- Streit F, Awasthi S, Rietschel M, et al. TH50. Genome-wide association study of borderline personality disorder – first results from The International Borderline Genomics Consortium. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;51:e221. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.08.222

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed., DSM-5. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, et al. User’s guide for the SCID-5-PD (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorder). Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association; 2015.

- Hummelen B, Johan, Braeken J, Christensen TB, et al. A psychometric analysis of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-5 Alternative Model for Personality Disorders Module I (SCID-5-AMPD-I): level of personality functioning scale. Assessment. 2021;28(5):1320–1333.

- WHO [Internet]. ICD-11 clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines for mental and behavioural disorders. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2022. Available from: gcp.network/en/private/icd-11-guidelines/disorders

- Bach B, Kramer U, Doering S, et al. The ICD-11 classification of personality disorders: a European perspective on challenges and opportunities. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2022;9(1):12.