Abstract

Coherence is highly important in teacher education and professional development programs—the extent of shared vision between position holders contributes to the program’s success. Nevertheless, the research on shared vision and coherence has primarily focused on teacher training programs. Hence, in this study, we conducted 29 interviews with teachers, principals, and district and national superintendents of professional development to explore various perspectives among position holders in the education system. Teachers and principals stress the atmosphere in schools and the wholistic experience of a teacher within school, whereas the national and district superintendents focus on building personalized courses for each teacher. There are agreements regarding the significance of teacher motivation, peer learning and study of practice. This study explores the notion of coherence in professional development through a holistic perspective, providing practical implications for improving the way education systems promote teachers’ professional development.

Introduction

Studies have focused on the effectiveness of professional development programs; they relate to the importance of practice, the relevance of the content to teachers’ daily work, their opportunities to practice during the program, and their ability to implement the acquired skills and knowledge after the program ends (Avidov-Ungar & Herscu, Citation2020; Korthagen, Citation2016). Teachers’ professional development is under the spotlight of educational policymakers, mostly as a tool in leading changes and reforms (Knowles et al., Citation2014). Teachers’ professional development relies on the presumed connection between the quality of the whole system and the professionalism of its teachers. In this way, policymakers try to enhance the implementation of innovative instruction methods, technologies, and progressive paradigms, under professional development programs.

Coherence regarding professional development is an important factor that affects its success. Coherence means shared views about the objectives and the means for achieving them among the individuals who take part in a process/action (Fullan & Quinn, Citation2016). Conceptual coherence regarding the essence of professional development between teacher educators, stakeholders, and the teachers themselves, proved to be a significant factor in programs’ success (Cavanna et al., Citation2021; Grossman et al., Citation2008; Hammerness & Klette, Citation2015; Levine et al., Citation2023). This study aims to broaden the scope of professional development coherence and examine it along different echelons in the education system. It focuses not only on a specific program—but on teacher education in the system. The research question is: To what extent is there conceptual coherence regarding professional development among different echelons in the Israeli education system?

Literature review

Attitudes toward effective professional development of teachers

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development defined professional development as “activities that develop an individual’s skills, knowledge, expertise and other characteristics as a teacher” (OECD, Citation2009), in order to achieve better student learning (Darling-Hammond et al., Citation2017). Professional development is a lifelong process, not just attending a specific course or program (Kovalchuck & Vorotnykova, Citation2017). One of the main goals of teachers’ professional development, which corresponds with the term “teacher education,” is to influence teachers’ in-class practice and change their behavior (Korthagen, Citation2016).

Korthagen (Citation2016) raised a major problem in teachers’ professional development—the huge gap between theory and practice, and the lack of impact on the teachers’ behavior. Accordingly, he defined several types of professional development:

Professional Development 1.0: explaining theories to teachers;

1.1. Professional Development 1.1: explaining the theories and giving practical examples of demonstrating the tenets of the theory;

2. Professional Development 2.0: practicing new methods as a central part in curricula; a major part of the time is dedicated to actual teaching;

3. Professional Development 3.0: helping the teacher to learn from his/her individual experiences by practicing, reflecting and analyzing. The focus is on the teacher, on understanding underlying processes and building professional identity within the context of work.

Professional development 3.0 approach illustrates effective teachers as people who can use their own unique core abilities combined with the outer-acquired competencies (Korthagen et al., Citation2013). This approach is consistent with Avidov-Ungar and Herscu (Citation2020) who pointed out that influential and effective professional development programs are those which reshaped teachers’ behavior in class and contributed to raising student achievements. On the other hand, negative experiences from professional development stemmed from lack of practical implementation, irrelevance to the daily work in school, or lack of time to practice within the program’s timeframe.

Professional development of teachers is in the spotlight of educational policymakers and has been a target of government policy, as governments perceive the professional development of teachers as a tool for achieving organizational and professional goals, such as higher standards (Knowles et al., Citation2014). Policymakers stress structuring and providing programs of professional development, as well as monitoring the content and outcomes of the programs. Correspondingly, teachers’ professional development is one of the main catalysts for change in an education system (Fullan, Citation2020). When considering professional development as a pivotal tool for change in an education system through boosting the educational staff’s quality, coherence is highly important.

Coherence in regard to professional development and teacher education

Coherence is a shared depth of understanding about the purpose and nature of the work, in the minds and actions individually and especially collectively (Fullan & Quinn, Citation2016). Coherence is thus more about motives and purposes, an agreed view of a process, and a shared educational ideology rather than specific modes of action (Sullanmaa et al., 2019). Several scholars distinguish between structural coherence and conceptual coherence. Conceptual coherence is the degree of agreement toward the ideas and the visions and structural coherence is the degree of agreement toward the means of achieving the goals, logistics and design (Cavanna et al., Citation2021; Grossman et al., Citation2008).

Promoting coherence involves alignment of goals, resources and structures, and the leaders of institutions try to ensure implementation of these goals and vision. Such implementation requires: (1) focusing direction to build a collective purpose; (2) cultivating collaborative cultures, which build collective capacity; (3) deepening learning, which can accelerate improvement and innovation; (4) securing accountability based on capacity built within the school and projected out to university leadership (Fullan & Quinn, Citation2016). Richmond et al. (Citation2019) emphasize that coherence in education systems is a process in which all stakeholders negotiate and create a valuable vision, as well as the goals and measures to achieve them. In contrast, a wrong perception of coherence is to think of it as a fixed-end state which is determined by the head of an educational institution (Cavanna et al., Citation2021).

A few studies which explore the coherence of teacher education programs have shown that shared vision and understanding entail achieving the desired outcomes of such programs. Studies which focused on candidates in United States, Norway, Cuba, and Chile and found that in the more coherent programs, teachers implemented the techniques learned in the programs and expressed higher motivation to continue teaching in the education system (Cavanna et al., Citation2021; Hammerness & Klette, Citation2015). Other studies also demonstrated correlation between program coherence and theoretical knowledge, practical skills and professional identity (Heggen & Terum, Citation2013; Smeby & Heggen, Citation2012).

A few scholars contributed to the study of coherence by examining coherence as a process and not as a fixed-end state. Levine et al. (Citation2023) explored the redesign of teacher education programs at the University of Connecticut and interviewed the teacher educators in the redesign process. They showed that extensive discussions and conversations between diverse faculty members and negotiating a common set of core qualities enhanced the coherence. Surprisingly, the interviewees delivered the notion that “surfacing conflict and fragmentation contributed to coherence” (p. 81). Hermansen (Citation2020) drilled down the redesigning process of Norwegian teacher education programs in pursuit of higher coherence, focusing on their leaders’ practices. The leaders fostered institutional educational shared views, which Hermansen labeled as ‘institutional coherence’. Hermansen stressed that these leaders used epistemic, organizational and political practices, mapping the way of the leader to achieve the desired coherence. Another study by Canrinus et al. (Citation2019) compared the coherence of three teacher education programs in three different countries: Norway, Finland, and California, U.S. Their findings concluded that programs could improve their coherence by communication and collaboration between the various stakeholders. Grossman et al. (Citation2008) examined the perceived coherence of graduate students between the learned material in the university and the practice in the field. They found that the perceptual unity of the teacher educators and the effort invested in connecting the mentor teachers to the university curriculum yield higher perceived coherence. This body of research around coherence in teacher education programs paves the way to exploring professional development and teacher education coherence in broader organizations such as education systems.

Broadening the notion of coherence: from program research to system research

Levine et al. (Citation2023) addressed the fragmentation processes within organizations and explained that the lack of coherence can stem both from clashing beliefs and misunderstanding of visions and ideas. Consequently, different position holders under the same organization can enact different policies because of “unclear goals, and the absence of agreed-upon processes for doing things such as coordinating action or resolving disagreements” (p. 72). Levine et al. related to the difficulty of leading a coherent vision inside a teacher education program, because of governmental policy initiatives and directives from governance structures. Moreover, Floden et al. (Citation2021) argue that a significant disconnect can occur, when the ‘experts’ who lead the professional development process are not perceptually aligned with the ‘novices’ who undergo these processes and take the professional development courses. Furthermore, Floden et al. emphasize that “institutional culture must prioritize programmatic coherence and quality and not perpetuate a model where program stakeholders continue to train teacher candidates in informal silos grounded in their individual understandings of program goals and individualized measurement tools” (p. 9). This framework lies the foundations to further research regarding the policies of teacher education and professional development at a specific education system, broadening scope from institutional scope to the education system vision of promoting professional development as a whole.

These fragmentations and disconnects in organizations are manifested in the implementation of reforms and policies. De Voto et al. (Citation2021) explored the case of teacher assessment policy (edTPA) implementation in the USA which has led to change in some professional development programs. The Educative Teacher Performance Assessment (edTPA) is a subject-specific, performance-based teacher support and assessment system (Whittaker et al., Citation2018). They showed that there were implementation challenges (related to structural coherence) and philosophical challenges (related to conceptual coherence) which stemmed from incompatibility between policy design and/or organizational factors. This policy revealed a schism regarding what “good” teaching is and how best to measure it. Ganon-Shilon et al. (Citation2022) also found a similar response when implementing the Meaningful Learning Reform of the Israeli Ministry of Education. The study outlines principals’ different implementation styles from adaptive to oppositional, while communication mechanisms were highly important in both fostering trust and motivation toward the change and reflecting the difficulties to the position holders outside school. Reframing the findings of these studies within the framework of coherence, the policies implementation problems stemmed from lack of conceptual coherence, structural coherence (Cavanna et al., Citation2021; Grossman et al., Citation2008) and a progress of building coherence when structuring and implementing the policy (Hermansen, Citation2020; Levine et al., Citation2023).

Ultimately, the scholarship converges around the notion that high coherence of professional development and teacher education depends on the extent of the agreement and understanding of notions, perceived by different position holders within an organization such as a university or a broader system as an education system in a region or a state (Bros & Schechter, Citation2022; Cavanna et al., Citation2021; Floden et al., Citation2021; Fullan & Quinn, Citation2016; Levine et al., Citation2023).

Research design

Research context—professional development in Israel

Unit A for professional development in Israel’s Education Ministry is responsible for providing professional development courses and programs (Israeli Ministry of Education, Citation2019). According to the unit’s perspective, there is a profound connection between the quality of the education system and the professional development of its educational staff. It is customary for every in-service teacher to participate in professional development programs of at least 60 h per year, and the teacher’s salary is determined by the number of programs that the teacher has taken (among a few other factors). Furthermore, the ministry funds 14,000 professional development programs, and offers funding for the MA, PhD, and other academic degrees (Israeli Ministry of Education, Citation2019). These programs consist of traditional frontal courses (resemble Korthagen’s professional development 1.0, Citation2016), as well as new methods of professional development frameworks: Professional learning communities, teacher-led school communities, school professional development processes, educational initiatives, micro-accreditation, digital courses, academic courses, postgraduate learning tracks, and more. These are provided through city centers of professional development, teachers’ guides and mentors who are employed and funded by Unit A (Israeli Ministry of Education, Citation2024).

Participants

This study contains 29 interviews with the following participants: the current head of Unit A under the Israeli Education Ministry, four national superintendents under Unit A, six district professional development superintendents, six heads of city centers for professional development, one head of innovative education center, five principals and six teachers. The participants were aged 29–65, all of them are women except one. The participants’ seniority in the education system was 1–36 years. Seeking to maximize the depth and richness of the data, we used maximal differentiation sampling (Creswell, Citation2021), also known as heterogeneous sampling. This varied sample allowed exploring different perspectives from different parts of the system, and thus evaluating the shared views and the degree of coherence. The superintendents were addressed via email according to their position, whereas the teachers and the principals were recruited by their ability to meet the criteria of the diverse sample. For example, a few Arab teachers were addressed and one gave permission to be interviewed. These were found through snowball sampling (Parker et al., Citation2019). Participants did not have any existing relationship to the researchers. The participants attributes are presented in .

Table 1. The participants, segmented to sectors according to the maximal differentiation sampling.

Data collection

Data were collected between February and July 2022. First, nine semi-structured interviews were conducted in order to formulate first impressions and lay the foundations for another set of data collection with more refined questions (e.g. can you identify discrepancies in the visions of different echelons regarding professional development). The preliminary findings were processed and presented to three educational experts for evaluation. They pointed out areas to focus on as well (e.g. the role of the principal in promoting teachers’ professional development). Thus, the first interviews assisted in forming refined interview questions and creating a more focused semi-structured interview protocol. Afterwards, the last 20 interviews were conducted with revised questions. The interviews were conducted online through Zoom communication, were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim and lasted between 40 min and 80 min, depends on the interviewee’s schedule. Ultimately, the two sets of interviews (the first 9 and the last 20) did not differ significantly besides adding focused questions regarding specific areas. Therefore, the two datasets are referred as one dataset of 29 participants. Overall, 253 pages of transcript were produced out of the interviews.

A semi-structured interview is a conversation with the interviewee, in which the researcher prepares a series of questions, but lets the interviewee raise related topics and subjects, which contributes to the research’s goals. This tool allows capturing the subjective experience of each of the interviewees, describing the reality as it is in the maximum depth possible (Sabar Ben-Yehoshua, Citation2016). The interview questions were broad, in order to capture the similarities and discrepancies of perspectives: (1) what is your vision regarding teachers’ professional development? (2) what is the system’s view? (3) Tell me about contradictive views of different layers in the system regarding professional development. (4) Tell me about a teacher that develops and another teacher that doesn’t. (5) What should a principal do regarding the professional development of his/her staff?

Data analysis

Analysis of interview data followed Marshall and Rossman’s (Citation2011) four stages, namely, organizing the data, generating tentative themes, testing the emergent themes, and seeking alternative explanations. In the current study, organizing the data was manifested in transcribing the interviews once and then reading them one after another. Afterwards, the second stage of generating tentative themes was manifested in sorting quotes that relate to specific issues of agreement and disagreements. The third stage was to refine and clarify the areas of discrepancy and coherent areas. Within this stage, each participant’s views were filled in a table according to the themes found in the second stage. These tables for each theme were the base for formulating figures which clarify the expressions of each perspective in each layer in the education system. Finally, after writing the three main areas which emerged from the data, a few alternative explanations were tested, and several were mentioned and elaborated on. At this point, we reworked categories to reconcile disconfirming data with the emerging analysis (Richards & Morse, Citation2013) as well as seeking alternative explanations to the emerging themes.

Ethics

Several measures were taken in order to maintain the ethical standard: each participant had explicitly stated if he/she agreed to be recorded and was able to stop the interview whenever he/she liked. The confidentiality of the participants is ensured, since pseudonyms are used for citing the participants and their institutions. This study was approved by the Faculty of Education’s Ethical Committee.

Findings

The data analysis yielded two major themes: (1) The principal’s role in the teachers’ professional development (2) Factors that stimulates and hinders professional development. Within each theme, different perspectives raised from different layers in the education system, reflecting discrepancies and agreements. In each theme, the perspectives of each layer were analyzed and presented as figures, illustrating the expression of each view by division to layer.

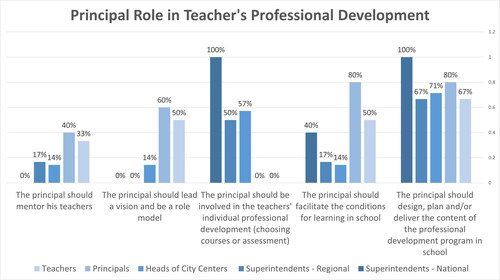

The principal’s role in the teacher’s professional development

Within the different layers in the education system, the principal role regarding professional development is one of the most debatable issues between Unit A, its professional development centers and the schools layer—the principals and teachers. The first disagreement is the involvement of the principal in the individual teacher’s processes and progression. Unit A position holders stress that the principal should choose the professional development program with the teacher and make sure the insights learned in these programs are manifested in school’s routine. Vanessa, a regional superintendent, stresses the one-on-one conversations and collaborative thinking:

The principal should be more involved in the professional development of his staff, and it is his full responsibility. It means to have conversations with them and to see where the teacher wants to go, what kind of career the teacher looks for, what is important for her. On the other hand, the principal should tell the teachers what he thinks – where the teacher should improve, what can the principal suggest, the principal should reflect what he sees. Another thing is to monitor the process during the process, it means that that choosing the relevant program is not enough.

The principal wants to promote his organization, to instill an educational vision – so he needs to make sure that his staff learns accordingly. The professional development is a tool for fulfilling school’s goals, the individual’s goals and the district’s goals. I would be happy if every principal would have a conversation with every teacher and ask the teacher what he learns.

We speak PBL in our school. Every subject (team) dives into that language, and gets into this pedagogical framework. We have mentors in our school, who grew out of the basic circle of PBL. Now they are in their professional development, they have specific courses for mentors… Every teacher who implements PBL is attached to a mentor. They have regular meetings where the mentor guides that teacher. The mentor watches the teacher’s lessons, and the teacher goes to the mentor’s lessons to see how it goes.

Expressing contradiction between Unit A expectations and perspectives of the principals, when asked about their involvement in the personal professional development process of their teachers, all of the principals said that they can’t reach that. Some of them said explicitly that they didn’t have time for one-on-one conversations with teachers. Quincy, an ultra-orthodox Jewish high school principal, is asked about the way her teachers choose a professional development program: “Usually a teacher that teaches a specific subject feels that something is missing. If she feels so, she registers herself in the field in which she wants to advance.” Allison, a mid-school principal, is asked about her involvement in the professional development program of each of her teachers: “I am not involved at all besides when teachers come to me and ask for permissions and days off because they take a professional development program.”

It seems that the teachers appreciate their autonomy, and they don’t expect the principals to be involved in their personal process. Daisey, a vice principal in a mid-school, describes how a principal can promote professional development in school:

let the teacher choose where she wants to develop and not to impose a program. To trust her. Once you have good teams and good subfield coordinators, a teacher can develop. Unfortunately, in our school the subfield teams don’t function.

She was nice and loving and I liked to conversate with her and learn from her vision – about putting the student in the center and promote skills and not knowledge … a principal succeeds in building the school staff and harness the teachers. It is very important in the teacher’s professional development – if the teacher feels connected and welcomed.

Finally, all the layers agree that there are a lot of requirements and demands from a principal, and the principals are overloaded with bureaucratic tasks, in a way that these expectations about mentoring and taking care of the teachers’ professional development cannot be fulfilled. Gloria, the head of the professional development unit under the ministry, explains that “Many principals choose an external expert and move forward, not because of bad intentions, but because they don’t have time and they are overloaded.” Jenny: “If you want professional teachers you need to mentor them. This is my opinion. But the principals have so many things to do so they can’t. Don’t be optimistic about it.”

The theme of the principal role regarding professional development of teachers addresses a low area of coherence: the policymakers and districts believe that the principal should be involved in the personal professional development of each teacher and the schools layer believes that the principal should let them have their autonomy. Some of the interviewees push the principal to be a role model and a mentor, whereas some want the principal to focus on programs and courses.

What stimulates and hinders professional development

The belief in the motivation of the individual teacher is highly coherent. When the interviewees told stories about professional development, they mentioned that it must stem from the natural tendency of the teacher—to learn and to change the instruction methods. Accordingly, a teacher can attend courses and programs, have a lot of experience and still to not develop. Lilly, a regional superintendent, explains the importance of inner motivation of a teacher:

I always say that there are external factors that can lead a horse to water, but if you change or not change, that depends on you…. I believe that today, someone that doesn’t study out of his inner motivation does not deserve to be a teacher.

Because I wanted it – I overcame obstacles and I grew. How do you say – when you work with your heart, you develop and nurture. If you don’t focus on your root, only with your paycheck and the convenience or the things you can or cannot miss, then you are not in the right field.

Another area with relatively high coherence is peer learning. Peer learning mainly occurs when there is a platform to hold it. Some of the principals took care of the meetings and their content. Allison, a mid-school principal, stressed the significance of peer learning within these weekly meetings:

We take successful projects and we let the people who led them explain about it in our weekly meeting. The teachers wait for it. Another thing is building study material together, writing it down in the meeting and then teachers check for each other.

My learning is around the staff, and I strongly believe in peer learning. If I have a difficulty I turn to a child’s emotional therapist and consult her. I always make my decisions with the principal and her vices, with the counsel and behavior analyst. I believe that the development is the cooperation of a team.

Another area of high coherence is the study of practice and learning from experience. When asked about their progression and development of their career, most interviewees answered that they learned from their experiences. The study of practice can happen individually, as some of the teachers reflect on their lessons and instruction methods. Naomi, a teacher from the southern periphery of Israel, explains what the study of practice is:

It can be noticing that there is a cool way to open a lesson or teaching the same material in different methods. It is developing ways to promote the strong ones or nurture the weak ones, it always exists. I don’t think that I have had a lesson and I haven’t checked if there is a better way to teach it than the way in the book because I don’t like the instruction methods in the book. So this is the study – you always read and research and learn.

We are responsible for connecting between theory and practice, which is very important. Clinical instruction, in which the teacher examines and researches and looks over his lesson with an inquiring eye, checks the lesson and himself, observes and derives lessons, refines the instruction processes and assessment processes. This is very important.

A school which is a learning organization is a school for both students and teachers. In this school they have mutual learning, not necessarily with a lecturer, but in communities that sit together and develop together. As a result, the cultural climate gets better, the sense of belonging gets better, leave the knowledge aside, the motivation goes up. Parallelly, the professionality goes up.

Professional development is peer learning and it is the study of practice. You usually study your practices with your colleagues – let’s take some things we built together and check what works and what doesn’t, and why…. This is very important, peer learning and solving shared problems and consulting – this is the effective way for professional development.

Look, there is no time. The school is madness – the problems of today are not the problems of tomorrow…. There is no time to stop and think. I am no longer a teacher, I just solve problems all day, patchwork, patchwork, patchwork. From the moment you arrive at school until you come out, it is crazy.

I had an B.A. and M.A and additional jobs in school and being a homeroom teacher and I have my children – so I didn’t have time to participate in these programs in the afternoons…. This year I started guiding a group in maintaining weight and nutrition. I hope to develop in this course and after a few years – enough with schools.

This is a rat race. This is what I feel. I try to be professional and be good at it, but I don’t have the time. I have one hour in my weekly schedule in school that is dedicated to my own development. In the other hours which I am not in class, there are meetings. You don’t have the time to build lesson plans and study the materials, so how do they want me to be professional?… This is my sixth year in the system and now I am looking for my way out.

She runs from place to place, from the mid-school to the high school, she doesn’t have time for the course of neither mid-school nor high school. The whole organization hinders her development. She is breathless and she doesn’t have a team. It is hard for me to see how this teacher can develop; I can see her running away from our school.

In school I have the support of the principal. He gives me responsibility and trusts me. Also, the other staff at school – they are like my family, my second home. I go there happily, even if I am busy and I have a lot of things to do, and I don’t have a minute for myself – I go to school with joy.

Another factor which is stressed by school layer is the modeling, which was not raised by the superintendents. Allison, a mid-school principal, goes over the things that helped her progression and developed her: “Before I became a principal, I had a feeling that the professional development was disconnected from the things that happen in school…I learned from people along the way. There are people who left a mark on me—principals, colleagues and position holders.”

Also Bella, an elementary school principal, explains about a significant superintendent that has contributed to her professional development: ”I have known her for 22 years. I decided that she is my mentor for life, I call her ‘my pedagogical mother’. I learned a lot from her—how to speak, how to write and think. I had a role model and I want to be like that to my staff.”

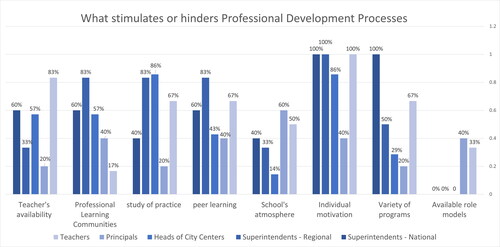

Figure 1. Percentage of each sub-group’s perspectives in the interviews, regarding the factors that stimulate or hinder professional development processes.

The variety of courses, programs and learning methods can help teachers build the most suitable professional development for them. When the programs can meet the teachers’ needs, their motivation will increase. As a result of this perspective, Unit A leads a personalization of the programs for every teacher. As seen in , this perspective is stressed more by the layer of superintendents, both national and regional, but also expressed by the majority of the interviewed teachers. Gloria, the head of Unit A, explains why she invests in variety of programs:

I cannot improve school’s atmosphere and environment. I can do several other things, like thinking of additional methods for professional development, that every teacher can choose his own way; the most convenient learning. There are teachers that learn in three concentrated days or teachers who love communities or teachers who like to learn alone. I need to allow everything, with guidance and support.

I think the definition has changed. We used to talk about giving the teachers the tools to improve their work, today we talk about personalization and how the professional development should provide the needs of all the teachers. Even if it demands adaptations, flexibility and building an ‘open’ syllabus, in which we understand the group’s needs and building the content accordingly.

It is important to speak the same language as the teachers (that come to professional development programs) … Working in youth village is not like working in un urban high school. It is a different language and a different world. You know, it is like a surgeon and a dentist. You can’t say that you are a doctor so you can do everything.

Discussion

Areas with high coherence

Most of the participants agreed that professional development must stem from the individual teacher’s will, aspirations, and motivations (as seen in ), therefore the courses must be adapted to the teacher. Accordingly, policymakers and districts promote variety of programs and courses (Israeli Ministry of Education, Citation2019). The superintendents name this process ‘personalization’, and some even state that their vision is to build the most suitable professional development program for every teacher. These processes are accepted by different echelons, therefore they reflect high coherence and agreement (Cavanna et al., Citation2021; Floden et al., Citation2021; Fullan & Quinn, Citation2016).

Two other areas of high coherence are the study of practice and peer learning. The participants agree that the professional development is strongly related to the practice, and it must be connected the daily work (Darling-Hammond, Citation2017). This reinforces the notion of strong connection between professional development and changing the teachers’ practices (Korthagen, Citation2016; OECD, Citation2009). Most of the interviewees agreed upon the importance of peer learning in schools. Almost all of them mentioned they advised to and learned from colleagues; policymakers and the districts promote Professional Learning Communities as a method of professional development—they offer it as a program, provide content, a guide and infrastructure. As in Korthagen’s professional development 3.0 view (Citation2016), and the description of a professional development process of a teacher by the OECD (Citation2009), a few of them stressed their belief that the practical knowledge is in the field, and people can learn and build this knowledge through peer learning.

Professional Learning Communities are reported as an efficient initiative, as they are welcomed gladly by their participants. These communities lead to an increase of student achievement, an increase of the time the teacher allocates for professional development and an increase of the satisfaction level of the participants (Raz & Moskovich-Zeit, Citation2019; Shartz, Citation2018). Building and supporting Professional Learning Communities addresses Korthagen’s (Citation2016) problem about the gap between theory and practice, because the content of these communities is the practices, instruction methods and everyday dilemmas, as a part of school’s reality. The conceptual coherence regarding practical learning and peer learning in the education system can offer an explanation for the Professional Learning Communities initiative’s success. In this case, the policymakers, districts and schools held a coherent vision about effective professional development and the ways to implement it (Cavanna et al., Citation2021; Grossman et al., Citation2008).

Areas with low coherence

The role of the principal regarding professional development is the most incoherent subject which has risen in the interviews. When asked about the principal role, the schools layer expressed satisfaction from the autonomy in choosing the courses they take and in implementing the insights learned in the programs they take, aligning with the global trend of valuing teacher’s autonomy (Strong & Yoshida, Citation2014) and principal autonomy (Addi-Raccah, Citation2015; Higham & Earley, Citation2013; Pilton, Citation2015). All the principals mentioned that they are not involved in the individual’s teacher courses. We believe this less coherent area is a discrepancy which can be labeled as an overt ‘clashing belief’ and not just ‘misunderstood vision’ (Levine et al., Citation2023), even decreasing the degree of coherence around that issue.

Bredeson (Citation2000) defines four areas where a principal can affect a teacher’s professional development: (1) being an instructional leader: (2) facilitating effective learning environment (3) direct involvement (4) assessment of the professional development outcomes. These roles can explain the discrepancy between the layer of policymakers and districts, and the school layer. The policymakers and districts expect the principal to be involved in each teacher’s professional development, guide the teacher, help the teacher implement the new methods learned in the program and give more personal attention to these programs, emphasizing Bredson’s (2000) direct involvement role and assessment role. When principals and teachers are asked about their expectations from the principal regarding professional development, they don’t mention involvement in the teachers’ courses, but they speak of mentoring, modeling and nurturing school atmosphere and infrastructure, emphasizing Bredson’s (2000) instructional leader and facilitator role. As seen in , the teachers want the principal to take care of the professional teams’ meetings and take care for the coordinator’s function, as well as the atmosphere in school.

Figure 2. Percentage of each sub-group’s perspectives expressions in the interviews, regarding the principal role in teacher’s professional development.

Another expectation of the schools layer is that the principal will be an instructional and pedagogical leader, as manifested in leading an educational vision, mentoring the staff (not necessarily about their programs) and being a role model. Continuously, the principal should facilitate school routines that foster teachers’ professional development processes, allocating time for personal mentoring and establishing a professional school community characterized by expectations for high teaching quality, thus developing the school’s human capital (Fullan, Citation2020). Furthermore, an extensive body of research emphasizes the importance of the principal as an instructional leader, which invests time and effort in pedagogy, in teachers’ professional development and in leading an educational language in school. This assumption lies on the connection between instructional leader behavior of the principal, high teacher motivation and high student achievements (Dutta & Sahney, Citation2022; Hallinger & Hosseingholizadeh, Citation2020; Liu & Hallinger, Citation2018; OECD, Citation2009 and more). A study in Taiwan (Chang et al., Citation2017) exhibits the principal role as a facilitator. In this study 453 teachers were asked about the influence of their principal on their professional development. The surveys raised that principal behaviors of “building a supported environment”, and “adjusting organization and performance” are significant in teachers’ professional development and in leading a change in school. This discrepancy of different principal roles, resembles the ‘disconnect’ definition of ‘experts’ who determine the institutional policy out of their individual understanding, while allocating less considerations for novices’ (teachers and principals) views (Floden et al., Citation2021).

Second, the significance of the factors that hinders or stimulates professional development reflects the ‘disconnect between experts and novices’ (Floden, Citation2021) as well. The districts and policymakers emphasize the personalization process and the variety of programs and courses. When they were asked about their vision—they spoke of maximum differentiation of contents and methods, thus sewing the best ‘professional development suit’ for the individual teacher (resembles Darling-Hammond, Citation2017). Some of them stressed the atmosphere in schools, the role of the principal and the organization’s structure, but their vision was mostly narrowed to programs. The school layer was more focused on the everyday reality in schools, the wholistic experience of the teacher in school—the relationships with the principal and peers, the atmosphere, sense of belonging as the main factors that affect the ability to develop. It seems that the variety of courses affects the teacher’s professional development, but the organization and the reality in schools also have a major impact on the development (Kovalchuck & Vorotnykova, Citation2017).

Implications, limitations, and further research

When referring to the main research question ‘To what extent is there conceptual coherence regarding professional development among different echelons in the Israeli education system’, we have found that the coherence is partial, as most fragmentation of visions occurs between two main layers; the schools layer and the districts and policymakers layer. These two layers hold an agreement (high coherence) regarding the importance of study of practice and peer learning, individual teacher’s motivation and Professional Learning Communities. On the other hand, the school layer and the districts and policymakers layer differ (low coherence) in their vision of the principal’s role regarding teachers’ professional development, and regarding the importance of key factors which stimulate professional development, such as modeling and mentoring versus personalized programs.

The study leads to three main recommendations for educators and policymakers. First, as seen in the interviews, coherent processes which reflect the views in the field and in the administration yield positive results which are welcomed and promoted across different echelons in the education system. Accordingly, policymakers and districts should take into considerations the need to build coherent processes, acknowledging that top–down processes could not be fully implemented in schools (De Voto et al., Citation2021; Ganon-Shilon et al., Citation2022). Thus, when there are discrepancies and misunderstandings, we recommend creating coherence around a new vision (Floden et al., Citation2021), and building of process of negotiating alignment among stakeholders’ various views (Levine et al., Citation2023) by enacting a process that includes a variety of teacher educators working together. It also involves gathering stakeholders from different echelons, fostering communication and collaboration between the various stakeholders (Canrinus et al., Citation2019). For example, the discrepancy of the principal role in teachers’ professional development can be addressed by gathering groups of principals with policymakers and districts representatives, surfacing the conflict and the fragmentation (Levine et al., Citation2023). These solutions must take in consideration the extensive burden that lies on the principal’s shoulders and the attention that is needed for every individual teacher’s development.

Second, the schools layer posits that principals need to invest more time and effort being an instructional leader who mentors his/her staff, being a role model and a facilitator that provides the supportive environment for teachers’ learning processes inside schools. Yet, the administrative burden on their shoulders distracts them from dealing with pedagogical processes. Studies in England, Germany and Israel reflect the education system’s will for lifting this administrative burden over the principals’ shoulders (Addi-Raccah, Citation2015; Higham & Earley, Citation2013; Pilton, Citation2015) as the findings from PISA report which show that the Israeli principal invest only 20% of his time in pedagogy and 40% in administrative work (OECD, Citation2016). Transferring some of the administrative work from principals to other sections in the education system could foster the professional development processes in schools and push the principal to the desired behavior of instructional leader. Thirdly, professional development sections should broaden the efforts which promote professional development processes. These include promoting mentoring and modeling processes in schools, nurturing the atmosphere and dealing with stress in work, since these factors have a major impact on teacher’s professional development (Korthagen, Citation2016; Kovalchuck & Vorotnykova, Citation2017).

The current study’s findings are limited, as a result of the small-scale sample and the qualitative research method. Hence, the study does not determine the level of coherence in the Israeli education system, but maps some of the perspectives that rise from the different echelons and offer a glance to the spectrum of views in an education system regarding professional development. Further studies with a wider sample are needed in order to validate the current study’s findings and to understand the coherence of the professional development’s notion in other parts of the system.

The current study was focused on the conceptual aspect of coherence, but not on the processes of cultivating coherence through redesign and change. Thus, further research can focus on the decision-making processes and the resources that leaders and policymakers invest in collaboration and negotiation of values and visions within education systems. Further studies can also explore the change of perspectives over a few years, thus provide an overview of new discrepancies and agreements in the education system regarding professional development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Addi-Raccah, A. (2015). School principals’ role in the interplay between the superintendents and local education authorities. Journal of Educational Administration, 53(2), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-10-2012-0107

- Avidov-Ungar, O., & Herscu, O. (2020). Formal professional development as perceived by teachers in different professional life periods. Professional Development in Education, 46(5), 833–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1647271

- Bredeson, P. (2000). The school principal’s role in teacher professional development. Journal of in-Service Education, 26(2), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674580000200114

- Bros, E., & Schechter, C. (2022). Coherence between policymakers and school leaders: Exploring a pedagogical reform. Journal of School Leadership, 32(5), 488–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/10526846211067641

- Canrinus, E. T., Klette, K., & Hammerness, K. (2019). Diversity in coherence: Strengths and opportunities of three programs. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(3), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117737305

- Cavanna, J. M., Molloy Elreda, L., Youngs, P., & Pippin, J. (2021). How methods instructors and program administrators promote teacher education program coherence. Journal of Teacher Education, 72(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487119897005

- Chang, D. F., Chen, S. N., & Chou, W. C. (2017). Investigating the major effect of principal’s change leadership on school teachers’ professional development. IAFOR Journal of Education, 5(3), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.22492/ije.5.3.07

- Creswell, J. W. (2021). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice? European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1315399

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute.

- De Voto, C., Olson, J. D., & Gottlieb, J. J. (2021). Examining diverse perspectives of edTPA policy implementation across states: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Journal of Teacher Education, 72(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487120909390

- Dutta, V., & Sahney, S. (2022). Relation of principal instructional leadership, school climate, teacher job performance and student achievement. Journal of Educational Administration, 60(2), 148–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-01-2021-0010

- Floden, R. E., Carter Andrews, D. J., Jones, N. D., Marciano, J., & Richmond, G. (2021). Toward new visions of teacher education: Addressing the challenges of program coherence. Journal of Teacher Education, 72(1), 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487120976416

- Fullan, M. (2020). Leading in a culture of change. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Fullan, M., & Quinn, J. (2016). Coherence making: How leaders cultivate the pathway for school and system change with a shared process. School Administrator, 73, 111–127.

- Ganon-Shilon, S., Shaked, H., & Schechter, C. (2022). Principals’ voices pertaining to shared sense-making processes within a generally-outlined pedagogical reform implementation. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 25(6), 941–965. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2020.1770864

- Grossman, P., Hammerness, K. M., McDonald, M., & Ronfeldt, M. (2008). Constructing coherence: Structural predictors of perceptions of coherence in NYC teacher education programs. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108322127

- Hallinger, P., & Hosseingholizadeh, R. (2020). Exploring instructional leadership in Iran: A mixed methods study of high-and low-performing principals. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 48(4), 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143219836684

- Hammerness, K., & Klette, K. (2015). Indicators of quality in teacher education: Looking at features of teacher education from an international perspective. In G. K. LeTendre & A. W. Wiseman (Eds.), Promoting and sustaining a quality teacher workforce (pp. 239–277). Emerald Group.

- Heggen, K., & Terum, L. I. (2013). Coherence in professional education: Does it foster dedication and identification? Teaching in Higher Education, 18(6), 656–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.774352

- Hermansen, H. (2020). In pursuit of coherence: Aligning program development in teacher education with institutional practices. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(6), 936–952. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1639815

- Higham, R., & Earley, P. (2013). School autonomy and government control: School leaders’ views on a changing policy landscape in England. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 41(6), 701–717. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213494191

- Israeli Ministry of education (2019). Unit A for educational staff’s professional development, Policy and instructions to educational staff in the “New Horizon” program.

- Israeli Ministry of Education (2024). January 17). Unit A for educational staff’s professional development – about the unit. https://edu.gov.il/horaa/MinhalOvdeyHoraa/professional-development/Pages/about.aspx

- Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., III, & Swanson, R. A. (2014). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Routledge.

- Korthagen, F. (2016). Inconvenient truths about teacher learning: Towards professional development 3.0. Teachers and Teaching, 23(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1211523

- Korthagen, F. A. J., Kim, Y. M., & Greene, W. L. (Eds.). (2013). Teaching and learning from within: A core reflection approach to quality and inspiration in education. Routledge.

- Kovalchuck, V., & Vorotnykova, I. (2017). E-coaching, e-mentoring for lifelong professional development of teachers within the system of post-graduate pedagogical education. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 18(3), 214–214. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.328956

- Levine, T. H., Mitoma, G. T., Anagnostopoulos, D. M., & Roselle, R. (2023). Exploring the nature, facilitators, and challenges of program coherence in a case of teacher education program redesign using Core practices. Journal of Teacher Education, 74(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224871221108645

- Liu, S., & Hallinger, P. (2018). Principal instructional leadership, teacher self-efficacy, and teacher professional learning in China: Testing a mediated-effects model. Educational Administration Quarterly, 54(4), 501–528. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X18769048

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2011). Designing qualitative research (5th ed.) Sage.

- OECD (2009)., Leading to learn: School leadership and management styles. In: Creating effective teaching and learning environments: First results from TALIS.

- OECD (2016). PISA 2015: Results in focus. PISA.

- Parker, C., Scott, S., & Geddes, A. (2019). Snowball sampling., In P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J.W. Sakshaug, & R.A. Williams (Eds.), SAGE research methods foundations. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526421036831710

- Pilton, J. W. (2015). International trends in principal autonomy. Lehigh University.

- Raz, T., & Moskovich-Zeit, A. (2019). Evaluating English teachers’ professional learning communities in 2017–2018. Israeli Ministry of Education, the Central Authority for Measurement and Evaluation in Education.

- Richards, L., & Morse, J. M. (2013). Readme first: For a user’s guide to qualitative methods (3rd ed.) Sage.

- Richmond, G., Bartell, T., Carter Andrews, D. J., & Neville, M. L. (2019). Re-examining coherence in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(3), 188–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487119838230

- Sabar Ben-Yehoshua, N. (2016). Traditions and genres in qualitative research. Philosophies, strategies and advanced tools. Mofet Institution.

- Shartz, Z. (2018). Professional learning communities network in the reality of a changing world: The case of science and technology in middle school. Kriat Beinaim, 31, 23–29.

- Smeby, J. C., & Heggen, K. (2012). Coherence and the development of professional knowledge and skills. Journal of Education and Work, 27(1), 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2012.718749

- Strong, L. E. G., & Yoshida, R. K. (2014). Teachers’ autonomy in today’s educational climate: Current perceptions from an acceptable instrument. Educational Studies, 50(2), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2014.880922

- Sullanmaa, J., Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2019). Differences in state- and district-level stakeholders’ perceptions of curriculum coherence and school impact in national curriculum reform. Journal of Educational Administration, 57(3), 210–226.

- Whittaker, A., Pecheone, R. L., & Stansbury, K. (2018). Fulfilling our educative mission: A response to edTPA critique. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 26(, 30. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1171719 https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.26.3720