ABSTRACT

This study explored the process of identity adjustment following adolescent brain injury, within the systemic context of the parent–adolescent dyad. Six young people with an ABI (mean age 16.5 years, range 15–18 years; TBI: n = 3) were individually interviewed, and six respective mothers (mean age 45 years, range 37–50 years). A novel relational qualitative grounded theory approach was used, with analyses of dyads linked in an attempt to capture the shared process of adaptation post-injury for young people and their parents. Shared themes emerged for adolescents and mothers regarding “continuity and change” and “acknowledging or rejecting” experiences of change post injury. Adolescents experienced change as an, at times, distressing sense of being “not normal”. While mothers turned towards their child, working hard to try to “fix everything”, adolescents sought continuity of identity in the context of peer relationships, withdrawing socially to avoid feeling abnormal, reframing or finding new relationships. Some mothers sought to fill social losses through family or disability-specific activity. This study provides a relational understanding of the process of identity adjustment post adolescent BI. Future research and clinical practice should recognize the significant work of mothers, and significance of social relationships to adolescents’ emerging post-injury identity.

Introduction

ABI is a leading cause of disability for young people and has the potential to affect the physical, emotional and psychological aspects of an individual's functioning (Kreutzer et al., Citation2016). It can lead to changes in an individual's sense of self and the core qualities that define them (Ownsworth, Citation2014) and have devastating impacts for both the individual and their family, especially so for children with acquired brain injury. Negative emotional outcomes for children following acquired brain injury such as internalizing and externalizing problems are common (Bloom et al., Citation2001) and might be more likely to arise in the context of poorer family functioning (Anderson et al., Citation2005). Furthermore, the consequences of the child's injury have an impact on family functioning (Rashid et al., Citation2014) with a bidirectional relationship between parental communication and adolescent behavioural outcomes also evidenced (Moscato et al., Citation2021). Parent–adolescent interactions following in the context of severe brain injury demonstrate stronger associations between criticism, conflict and behavioural and functional outcomes compared with orthopaedic injury controls (Wade et al., Citation2003). This highlights the close connection of child and family outcomes following brain injury.

Following brain injury there are also marked alterations in how individuals experience themselves (Nochi, Citation2000; Ownsworth, Citation2014) and in adulthood this experience of altered identity has been recognized as associated with negative psychological outcomes, although such changes may not be unique to acquired brain injury (Beadle et al., Citation2016). A diversity of terms related to “self” and “identity” have been used in the brain injury literature reflecting a range of theoretical orientations, summarized by Ownsworth (Citation2014). These include: cognitive representational models of self or self-concept (Ownsworth & Haslam, Citation2016); social identity theory (Haslam et al., Citation2008; Walsh et al., Citation2015) which relates internalized models of “selves” (me) to specific social identities or roles (we); contextual approaches representing identities as narratives constructed through lived experience (Ellis-Hill et al., Citation2008) or through social interactions with others, in particular the family (Yeates et al., Citation2007). James’ (Citation1890) view of the “self as duplex” has been elaborated in a contemporary developmental identity model distinguishing an “acting” aspect of “self” and an “observing” aspect (Harter, Citation2015).

Across these diverse orientations, research studies indicate individuals can experience a subjective sense of loss of “self” (Nochi, Citation1998) or discontinuity between pre-injury and current sense of self (Couchman et al., Citation2014), often closely tied to experience of self in specific types of activity or social context (Gracey et al., Citation2008; Levack et al., Citation2014). Subjective sense of self-discrepancy can be a barrier to adjustment (Ownsworth & Haslam, Citation2016), with poorer mental health outcomes linked with greater discrepancy (Cantor et al., Citation2005).

Adolescence is a critical time for identity development, and a successful negotiation through adolescence is considered to lay the groundwork for psychosocial development in adulthood (Erikson, Citation1959; Marcia, Citation1980). According to social identity theory, belonging within a social group becomes pivotal in adolescence (Newman et al., Citation2007), with this social identity becoming internalized within one's concept of self over time (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1986). A prominent development identity theory is that of Harter (Citation2015) which highlights the particular “liabilities” that can arise negotiating development of identity at different stages of childhood and adolescence. Harter argues that the “self” is primarily a cognitive construct but is fundamentally influenced by parent and peer relationships. The ways in which the parent perceives the child's identity post brain injury can impact markedly upon the self-identity of the child (Bohanek et al., Citation2006). Adolescents also engage increasingly beyond the family, and wider social engagement becomes key to healthy development (Patton et al., Citation2016). Adolescents with ABI are particularly vulnerable to experience disruption to their developing sense of identity, and also between their current and imagined or hoped for identities (Van Leer & Turkstra, Citation1999).

With social context emphasized as an important aspect of identity development, it is unsurprising that “fitting back in” at school is a potentially important need for an adolescent with brain injury (Sharp et al., Citation2006). Whiffin et al. (Citation2019)..concludes that family members are active agents in the sense making of the “self-concept” for the (adult) brain injured individual (alongside their own identity adjustment post injury). A successful resolution of self-identity for the brain injured individual has also been demonstrated as key to both individual and family functioning (Couchman et al., Citation2014) and better family function affects outcomes for young people with BI (Micklewright et al., Citation2012; Yeates et al., Citation2010). Therefore, brain injury impacts upon identity and, in turn, upon emotional outcomes in adults and adolescents with brain injury. Changes in the injured adolescent and in their relationships with others, especially family, can establish bidirectional processes that impact upon psychological adaptation. While the relationship between identity and psychological outcomes has been well evidenced in adult brain injury literature, this has been explored less in adolescent brain injury, and there has been less attention to identity as negotiated in relationships with parents. Given the likely interdependence of adolescent and parent adaptation and identity, research exploring the negotiation of changed identity within the parent–adolescent relationship is warranted.

The current study aims to develop an understanding of the process of identity adjustment following adolescent ABI, with sensitivity and attentiveness to the relational context of the parent–child dyad, to understand the process through the lenses of both parent and adolescent. Given the importance of family and social context to neurorehabilitation outcomes the findings may help further inform clinical practice.

The research question for the current study is: what processes of change, adaptation and re/construction of identity are described by adolescents with ABI and their parent(s)?

Methods

Context and design

The main author (CG) was pursuing a long-standing interest in adolescence and the passage to adulthood, with research and clinical experience in this area. Discussions with the supervisory team highlighted the complex ways in which parents of children with a brain injury attending a specialist neuropsychological rehabilitation service appear to negotiate identity changes, which led to the development of the current study.

This study employed a contextually sensitive grounded theory (GT) approach to explore the shared and individual experiences and process of identity change in adolescents post-ABI and their parents. A critical realist approach was taken, in which it is assumed there is an external “reality” but this can only be known through the lens of specific social contexts. The study utilized “grounded theory-lite” (Pidgeon & Henwood, Citation1997) and drew on Charmaz’s (Citation2014) constructionist grounded theory which pays particular attention to the co-construction of the GT given the social contexts of participants and of the researchers, rather than attempting to achieve an objectively “true” generalizable theoretical account. Consistent with constructionist and critical realist approaches, GT lite uses GT techniques to develop categories and concepts to develop an understanding of the relationships between these but may not have as its aim to reach data saturation or generate a fully articulated grounded theory (Braun & Clarke, Citation2014). Furthermore, given the interest in the relational aspects of the adolescent–parent interaction, we sought to not only capture the individual processes of parents and adolescents, but apply the analysis in such a way as to capture shared or relational aspects of interactions pertinent to experience of identity change.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were that the adolescent was (a) between 10 and 19 years old, (b) living at home, (c) six months or more post brain injury, (d) had sustained their ABI since turning 10 years old. For parents, inclusion criteria were that they: (a) were a primary caregiver, (b) had sufficient ability in English. Exclusion criteria for young people were severe language difficulties or impairments; and for both members of the dyad, severe mental health and/or substance misuse disorder that would present a barrier to engaging in study tasks.

Participants

Six adolescents with ABI and a respective parent () were recruited from a community-based UK National Health Service paediatric specialist neurorehabilitation service (convenience sampling). All participants where both parent and adolescent expressed an interest were included. All participants had ABI which had been evidenced through brain change recorded from scans and recorded in their patient notes. For a “GT Lite”, as few as six participants may be sufficient (Braun & Clarke, Citation2014, p. 50), thus guiding a sample size of six dyads.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Procedure

Ethical approval was sought and granted from the Health Research Authority and NHS Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 213891). The local gatekeeper (clinical psychologist, SW) within the service and the clinical team identified all potential participants meeting inclusion criteria from their active caseloads to seek consent to be contacted about the study by the researcher. Following this, prospective participants expressing an interest were contacted, provided with information and, if willing, consented to the study. In the timeframe for recruitment, six dyads came forward, preventing the researcher from applying purposive or theoretical sampling (selection of cases to ensure diversity of sample) as is typical in GT. Participants were informed as to the members of the research team and that the study was being conducted as part fulfilment of the lead researcher's (CG) doctorate in clinical psychology.

Data collection and analysis

Semi-structured interviews were conducted, and audio recorded in participants’ homes by the main author (CG, a white, female, doctoral trainee clinical psychologist and mother). Participants were not previously known to the main author (CG) although were known to other members of the research team not directly involved in interviews or data analysis (SW, FG). Parents and adolescents were interviewed separately to best enable each narrative to be heard (Daly, Citation1992). Interviews utilized a topic guide (see Appendix) that was fluid and amended as the process went on to increasingly elucidate the emergent theory. Earlier interviews signalled a possible divergence in the dyad with mothers focusing on their adolescent child, and the adolescents focusing on their peer relationships to the exclusion of their mothers. Questions therefore shifted towards attempting to identify shared experiences and also exploring these specific orientations of mothers and adolescents. One mother interviewed twice, owing to time constraints in the initial interview. One adolescent had his mother present owing to expressive communication difficulties. The participant's mother was requested by the researcher to refrain from answering on the participants’ behalf, but rather just to clarify the word or phrase where articulation difficulties made this especially unclear. Interviews averaged 68 min for adolescents and 75 min for parents. Eight of the 12 interviews were transcribed by an independent transcriber, and four by the primary researcher (CG). Member checking of the transcript was not sought. All steps of the coding were reviewed by a member of the research team with expertise in qualitative research (FG) and the emergent analysis discussed with research team members with relevant clinical experience (FG, SW). In keeping with GT methods (Charmaz, Citation2014), there was a simultaneous process of data collection and analysis. This entailed the use of constant comparative methods in order to examine new data in relation to existing data and the emergent analysis; facilitating the development of conceptual categories; and the systematic use of GT analytic methods to navigate towards abstract analytic levels. Each dyad was analysed in tandem (CG), and connections were sought within and then between dyads through an iterative constant comparison process of flip-flopping between data and analysis (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1968) towards an overarching individual and relational account of identity adjustment. Consistent with GT “lite” and the critical realist approach, theoretical sufficiency (Charmaz, Citation2014) was sought rather than full data saturation. Theoretical sufficiency was considered achieved when no further elaboration of the conceptual coding was possible from the interview data through seeking contradictory or inconsistent information previously gathered from the interviews.

Given the critical realist stance of the study, it would be inappropriate to consider the robustness of the methods through a positivist lens, which is concerned with internal and external validity, reliability and objectivity / risk of bias. A number of frameworks have been proposed for ensuring rigour of qualitative methods, which tend to vary according to epistemological position. Here we drew on Yardley’s (Citation2000) reflection on dilemmas in quality of qualitative research, and Lincoln and Guba’s (Citation1985) well established criteria for trustworthiness in qualitative research. This covers credibility of the findings, transferability, dependability (recognizing if there is not a single shared psychological reality, an attempt is made to detail the contexts to which the findings apply), and confirmability (if the researcher is not seen as achieving complete neutrality or objectivity, then the process by which results are obtained needs to be transparent and include reference to reflexivity and auditability of the analytic process).

In the current study, given the critical realist stance of the research team, reflexive processes were used throughout including regular reflective supervision and use of a reflective journal with entries completed immediately following each interview and throughout the analytic process. This enabled the researcher (CG) to maintain an awareness of their own construction of the analysis in keeping with markers of quality such as trustworthiness and transparency (Yardley, Citation2000) and to share and reflect on this with the research team. Member checking of transcripts was not completed. However, in keeping with Yardley's marker of “impact and importance”, findings were discussed with a specialist team in paediatric neuropsychological rehabilitation and other paediatric rehabilitation professionals and affirmation of the resonance of findings with clinical experience was provided. This further indicates potential transferability (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985) of findings beyond the study sample.

Results

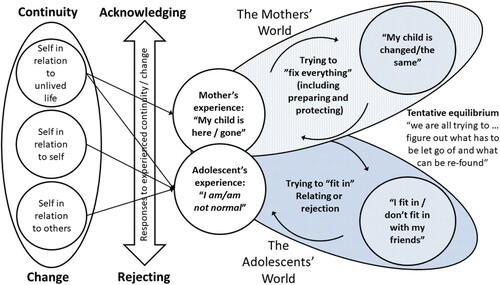

The grounded theory analysis (see and ) yielded themes illustrating individual and shared processes related to the experiences of “Continuity and Change” in identity and responses of “Acknowledging and Rejecting” these changes.

Figure 1. Grounded theory of dyadic identity change processes post adolescent BI.

Table 2. Summary of overarching conceptual themes and subthemes from the grounded theory analysis

Individual processes described by the adolescent post injury related to appraisal of current self in relation to past self (“'self in relation to self”), and to others. Adolescents and mothers also reflected on changes by comparison with the “unlived life” lost. Adolescents acknowledged tensions around normality and abnormality (“I am / am not normal”) to varying degrees, while mothers described their counterpart to this in their experiences of “hereness” and “goneness” (“My child is here/gone”) of their adolescent child post-injury.

Within this relational space of negotiating current and future identity change and continuity, mothers and adolescents engaged in diverging attempts to “resolve identity discrepancies”. While mothers sought to minimize discrepancies by attending to the needs of their adolescent child (by trying to “fix everything”, preparing and protecting), adolescents typically turned towards peer relationships to make sense of identity changes, seeking to relate to others and fit in. This constructed a relational space that was both heavily interlinked and imbalanced in terms of the relational attention of mother to child, and child to peers. Attempts to “fit in” or to “fix everything” could at times have the paradoxical effect of highlighting difference or change for both parties, while at other times could be adaptive. Adolescents’ attempts to “fit in” also risked paradoxical effects of rejection or were managed through beliefs that the pre-injury friendships were still there when this was not the case. Mothers in particular spoke of experiences of a type of loss or grief about changed aspects of their child. The dyads also at times indicated some shared experiences of identity adaptation and a movement towards a tentative equilibrium, as attempts were made to resolve discrepancies or accept changes.

Continuity and change: Experience of the current self and other selves

Adolescents described, to varying degrees, how they experienced tensions between change and continuity across different aspects of “self”, as illustrated on the far left of . These arose where the adolescent reflected on their past self, their lost future self or compared themselves to others.

Self in relation to past self

This theme captures the adolescents’ own reflective process of observing and experiencing their “current self”. Accounts all indicated some degree of an experience of rupture to self along a spectrum from minimal perceived changes to experiences of being a wholly different person. Young people could recognize differences in comparison to pre-injury selves in many domains – changes to skills including motor functioning (altered gait for example), energy levels or fatigue, and sexual development. Adolescents described how, when awareness of a limitation or change was triggered, this self-appraisal provoked a range of responses including frustration, upset and at times feeling suicidal.

These negative responses arose especially for young people who expected themselves to be able to operate across life domains as they always had done. Leah spoke about physical development rupture: “My stroke messed with my hormones, so my body is still basically like it was when I was 13 and it's kind of put my self-esteem real low”. Aiden noted how “Sports was my life” prior to injury, and Matt spoke about being “a different person when I came back [home from hospital].” For some, experience of discrepancies sat alongside experiences of continuity of self.

Self in relation to the unlived life

Dyads recognized the unlived life of the adolescent, their imagined future had they not acquired a brain injury. Noah reflected how “if I wouldn't have had the accident, I would’ve been in the big class with everyone else”. This unlived life was present also for mothers as a point of comparison when describing their adolescent child post-injury. Kath spoke about seeing her son Aiden's peers progress along the academic trajectory he would have gone down, and the life she had expected for him before the injury.

Self in relation to others

Accounts of relatedness and/or rejection from peers were shared in every dyad. For four adolescents, friendships were spoken of as fundamentally altered post injury, characterized by sense of being rejected or friendships withdrawing. For other dyads, divergent accounts emerged, where mothers perceived peer rejection and the adolescent described friendships as continuing unaffected. A sense emerged of the relational space of the young person whereby sensitivity to rejection from peers and being perceived as changed could lead them to recoil or withdraw, impacting upon future opportunities for peer relatedness. Leah explained how: “I don't like confronting people, so … I just kind of avoided it … em so just ended up kind of accepting that, um, we just weren't friends anymore”.

Finally, intimate relationships were touched upon in interviews, and this element of the young person's life seemed ruptured and on the “backburner” for the young people who alluded to it, while for others there was a replacement of challenging or rejecting experiences of friendships within the relative safety of 1:1 intimate relationships.

In all cases, adolescents’ explanations of changed identity centred around stories about connectedness and/or rejection within social relationships more than parent relationships. Where friendships ceased, young people most often made meaning of this by attributing change to self, and internalizing reasons for the rejection, as illustrated below.

Acknowledging and rejecting: Response to experienced continuity or change

The ways in which participants made sense of or tried to resolve or acknowledge issues of change and continuity resonated across all accounts, representing a range of complete or partial acknowledgement or rejection of the injury and changes. This resulted in unique but overlapping sense of change for adolescents (“I am / am not normal”) and mothers (“My child is here / gone”).

I am/am not normal

Adolescent accounts indicated a questioning of their normality in relation to peers as part of their experience of discrepancy. Leah expresses this sense of not being normal: “I just kind of want to be normal, I want to kind of see myself as a normal person”. Jack's sense of complete change is clearly illustrated here:

I just feel like that's something in my head, what's make me think differently, feel differently and just do stuff differently. Like I just feel like a completely different person because of it … than I was.

There was some variation among the adolescents regarding how they talked about this altered sense of “normality”. For Jordan this was about his “self in relation to (past) self”, wanting to get “back to my normal self”. The sense of experiencing oneself as abnormal could lead to ideas about the perceptions of others, as articulated here by Jack:

Just thought I was some weirdo … . I just thought that something was wrong with me … I just didn't know what. That's why I was thinking that they must be thinking the same thing.

Throughout the interviews, young people often struggled to accept their injury as this profoundly challenged their sense of normality with “normality” of identity and brain injury being viewed as mutually exclusive. Some adolescents indicated the importance of being seen as not disabled in order to retain a sense of “normal” identity.

My child is here/gone

Mothers made meaning of rupture and discrepancies in their child's identity through perceiving their child from continuous or “here” to discontinued or “gone”. Sometimes accounts pointed to a phenomenon of simultaneously incongruent experiences of the grieved for and the remaining child (my child is here and gone). Mothers also indicated tension around how to hold a disability identity alongside a non-disabled one for their adolescents.

In contrast to other accounts, Kirsty reported she did not recognize any elements of her child as different, indicating a belief that this would be incongruent with her role as mother. “I don't (see him as different) because I’m his mum, so I’m not going to view him different.” Kath spoke at times about her son post injury in a way that implied he was an iteration of her “real” pre-injury son, who could be visible at moments post injury, describing oscillations between the now child and pre-injury child that she experiences.

This was echoed in Natalie's description of ongoing interactions with a grieved for child, who she perceived was being “re-found” in new roles such as volunteering at a sports centre, where “you suddenly see him again”; while reflecting she sometimes struggled to recognize him: “he can be cruel, and when he's like that I don't recognize him, and it does feel like he's gone”. She pointed towards a grieving process but:

It's not what you would call a clean grief … we are further away from the little boy we had and … there were a lot of key things about Matt that, some of them are core things, some of them are still very much there. But there's, there's a massive percentage of him that's been lost.

Grief over this incongruence between pre and post injury was acknowledged also by Amanda. “It is like a bereavement […] He is the same but different … Some of the boy has gone … . The bits that have gone are the bits that I’m hoping over time, we can support.”

Resolving discrepancies

A range of responses to changes were described by adolescents and their mothers. These included recognizing or holding on to elements of continuity, seeking to renegotiate peer relationships or (for mothers) working hard on reconstructing systems so family connection and activities replace peer absence. Adolescents sought ways to minimize the distress associated with relationship loss or rejection. Mothers spoke about attempts to rebalance, resolve, acknowledge or reject the various troubling, weird, abnormal frightening things experienced by their child and themselves. As described below, they described attempts to “fix everything” through a series of processes which were sometimes conflicting as they tried to protect the child while also promoting autonomy.

Fitting in

Adolescents sought ways to manage any experienced self-discrepancies to find a way to “fit in”. They spoke about attempting to negotiate or renegotiate their social domain in a response to ruptures and tensions in their relationships. Responses included finding ways to explain changes in a way that was unrelated to brain injury changes or seeking new avenues for relationships.

Several young people indicated that alongside a sense of friends withdrawing, they also made active choices or reacted to pull away and to seek others they could feel more connected with. Jordan found a sense of relatedness with new friends based upon shared experiences of adversity, feeling his old friends didn't understand him as they “hadn't been through stuff”. At times, friendship losses were rationalized as owing to normal adolescent life or to experiencing the other person as changed, to realign continuity of self-narrative. Jack highlighted his experience of post-injury changes being magnified by the reactions of peers.

As I was losing more and more people, I felt more and more different. Like … I wouldn't be losing all these people if I was normal.

I think mostly … I think it was like the social side of things. Like both the online community and kind of starting to make new friends, em, so it was kind of just like em you know, like maybe this could get better, that kind of thing, I might as well kind of accept it rather than just dwell on it and then feel worse. So yeah.

Fixing everything

Mothers worked hard to attempt to reduce the perceived discrepancies and distress experienced by their child, trying to balance competing needs and minimize the consequences of brain injury. This sense of expectation as a mother is illustrated here where Kath explained how “It's your job, to make him feel like everything's better”.

Two key and potentially discrepant processes were described: Preparing and Protecting. Preparing referred to the process of looking towards the future, by getting all supports and structures in place that may reduce the possibility of feeling “abnormal” and support the child's future needs and development towards adulthood. Mothers made efforts to set up and support their child, being highly motivated to fight and advocate for appropriate services and supports. As Kath says, it “puts a fire in you that you never thought you had”. They made attempts to support their children to recognize and align with personally meaningful goals, and consciously or otherwise spoke to instilling resiliency as they approach the future.

Protecting referred to the mother's feeling for their child's experiences of discrepancies, distress and sense of abnormality. Mothers described attempts to alleviate or prevent distress through limiting exposure to potentially challenging experiences in the world post injury. Specific types of process to anticipate and reduce distress included: padding (compensating, mediating relationships), being present, and holding the psychological load (subjugating and sacrificing, being the emotional punch bag, and worrying over vulnerability).

Kath described efforts to address rejection by friends by attempting to fill the friend role herself:

Because he hasn't got that best friend. You know. He doesn't see his friends as he would. So, I might be- … So I have to fit into all of these different roles and try and be a bit of everything for him, so he doesn't miss too much of it, you know.

Mothers faced dilemmas over how to best support their children. Kirsty said: “I didn't want him feeling sorry for himself and getting in a deep depression and that. So yeah, we were out doing lots of stuff”. Faye spoke about how she dropped boundaries around her son for fear of triggering an episode of distress. Here she recognizes with hindsight that this may have not been helpful: “He was there doing whatever he wanted … . Not good. … coming home two-two, three o’clock in the morning … ., not feeling any structure or routine”.

Natalie reflected on how she “didn't want (her son) feeling like he was wrapped in bubble wrap”, and so “tried to sort of take a step back whenever I could”. She recognized the challenge of supporting autonomy while still perceiving her child as fragile and described an increasing need to hide scaffolding from him as he got older so he felt more like an adult.

Similarly, Amanda recognized challenges with stepping back and letting her child be more independent:

“It's hard for me sometimes to not take over. I know I do that sometimes that if he's struggling to get something, I sometimes butt in.”…. “Because of what happened that stays in your head. It's my issues, not his issues of letting him go.”

This was reflected in her son Jordan's experience, who spoke about how he had felt infantilised post injury: “she'd treat me like a child”.

Adaptation towards a tentative equilibrium: “What has to be let go of and what can be re-found”

To various extents, all accounts pointed to processes of moving towards tentative balance through finding new meanings in life post-injury. Social reconnections had been reframed, reconstructed or new ones built. Improvements were recognized and mothers acknowledged reduced anxiety and dependence to greater or lesser extents. Adolescents indicated optimism while mothers acknowledged the path forward as unclear.

There were references to expansion of self and post traumatic growth. Aiden recognized some value in his experience of brain injury (“I think people can learn from me”) and in the social connections the dyad had made (“me and mum have met a lot of nice new people”) while Leah shared a sense of transitioning from rumination towards an acceptance, and a sense of rebirth; acknowledging friendship loss but also the opportunities to start new ones.

Jack recognized that he is experiencing “more good days than bad”, while his mum looked tentatively forwards: “I’ve accepted that the future is uncertain, and I’ve just got to take each day as it comes”.

Matt reflected on reframing his injury

I’m trying to see it as more of a positive thing than as a negative thing, because seeing it as something that's always holding me back, then I’m always going to be held back for the rest of my life.

He's either trying to, well I guess we all are in a way, either trying to let go of or reclaim, re-find, or try and figure out what has to be let go of and what can be re-found and what can be worked on you know. And, trying to accept ether way. It's still early days. And we are 7 years in.

No fixed end point was described, with ongoing struggles of sense making and new challenges discussed alongside a sense of optimism and acknowledgement that the young person was in a better place in terms of their experiences of self. The amount of work and time implicated here is clearly very significant. Recovery narratives were redefined, with Natalie explaining “it isn't as much something that you get past, it's more that you learn to live with it.”

Discussion

This study set out to identify individual and relational processes of change, adaptation and reconstruction of identity in a sample of adolescents with brain injury and their mothers. The grounded theory analysis identified a core relational issue of experiencing post-injury changes in terms of “normality” for the adolescents and in terms of being “here or gone” for the mothers. Mothers turned towards their child engaging in efforts to “fix” their actual and anticipated sense of abnormality through the actions of protecting them from current challenges or preparing them for the future. At times this created a tension where their efforts might paradoxically highlight post-injury changes such as increased dependence. At the same time, adolescents oriented towards their peer groups, engaging in a process of maintaining or seeking new ways to constitute themselves socially in the context of tensions around continuity and change. Again, at times efforts to “fit in” were met with rejection generating further challenges to resolve. Over time, both adolescents and mothers made attempts to resolve discrepancies, address feelings of loss or grief, find new meanings to help cope with the present challenges or to feel optimistic about the future. The significant amounts of time and effort and the instability of these adaptive changes was evident.

These accounts of fundamental changes to the sense of oneself described here are consistent with existing accounts in the literature on identity following brain injury in adults (Ownsworth, Citation2014), and the relational responding and orientating to continuity has also been illustrated by Yeates et al. (Citation2007) in their study of awareness in the family context. In the current analysis, the relational responding to perceived changes seemed to elicit a response in both the adolescent and mother to attempt to resolve or minimize these discrepancies. Mothers drew upon social expectations of the role of mother in how they responded to distressing changes in their child. This included a construction of the adolescent as “unchanged” by the injury, as well as social expectations to protect their child from happenings like peer rejection. Importantly, for both members of the dyad, narratives around change often sat alongside narratives about continuity (Ellis Hill et al., Citation2019) requiring significant work within the family context. This relational “work” has been described by Whiffin et al. (Citation2021) in their meta-synthesis of family adaptation following adult TBI. The current analysis extends this to recognize the work of the brain injured adolescent in their own important peer relationship context, and at times of the mothers in attempting to “fix” the effects of disrupted or lost relationships.

The elements of self-concept (ideas and beliefs about oneself) and identity (selves enacted in roles or activities with others) were closely linked for the adolescents (Di Battista et al., Citation2014). Accounts indicated clearly how experience of social identities (for example, in relationships with peers) framed beliefs about themselves (for example, being seen by others as, and feeling oneself as “weird” or “abnormal”). While this is a typical aspect of adolescent development (Harter, Citation2015), experiences of abnormality and loss of self perhaps reflect something more uniquely related to brain injury, resonating with the narratives described by (Nochi, Citation1998). Adolescents’ description of their altered experience of self post-injury as being in a different body, sensing “weirdness” or disconnection or not being the person who they were before, echoing the existential threat to identity described in the adult literature (Ben-Yishay, Citation2000, p. 128). Adolescents attempted to negotiate this negative experience of self through social withdrawal or attempts to find new peer relationships that aligned with their post-injury self (e.g., as having “been through stuff”). The current study additionally highlights the role of mothers whose actions of “protecting” or “preparing” in anticipation of feared challenges might impact upon this process.

For mothers, their adolescent child was experienced along a spectrum from “hereness” to “goneness” post-injury and sometimes incongruent simultaneous experiences of both. Core and continuous elements of the child were acknowledged alongside loss and bereavement, again echoing the complexities of sense-making narratives shared in family adaptation to brain injury (Whiffin et al., Citation2021). Social discourses about the maternal role being concerned with “care” and “nurturing” (Arendell, Citation2000) were evident in themes such as “my job is to fix everything” when attempting to address their concerns about experiences of change post-injury. This finding is unsurprising as it reflects a common social conceptualization of motherhood. However, in the context of brain injury attempts to “protect” or to ignore changes could have unhelpful implications for longer-term adaptation and for the rehabilitation process.

Mothers’ negotiation of tensions between desires to protect and prepare and in the process reduce current or future discrepancies for the young person is also evidenced in the qualitative work of Roscigno and Swanson (Citation2011). The challenges faced in this negotiation of mothering a child post BI who is also an adolescent seeking to develop autonomy led mothers to at times take a more controlling position which the adolescent might contest or react against (Yeates et al., Citation2007) or less structured, resulting in potential increased risks. Adolescent accounts did not reflect awareness or acknowledgement of the significant efforts engaged in by their mothers to attempt to aid continuity and “normality”. This could have been a reflection of the social place of mothers as ever present for them, lack of attainment of sufficient perspective taking to appreciate their mother's contribution, or issues with development of self-awareness. As noted in adult (Gracey et al., Citation2009; Lyon et al. Citation2021) and adolescent (Compas et al., Citation2017; King et al., Citation2020) literature, some exposure to challenge or difficulty might be a necessary substrate to adaptation, incorporating shifts in self-awareness, identity and self-concept.

Though mothers made efforts to mediate and scaffold friendships as well as compensate for friendship losses, this was the area where discrepancy seemed most located in the narrative of the adolescents. This is aligned with adolescent literature on the increasing importance of social belonging through this phase of development (Roscigno et al., Citation2011), but it may also be that this is the area where the adolescent most notices change because this is the one their mother can least protect them from.

The tensions of change and continuity for mothers in the current study resonate with existing literature on family responses to brain injury. For example, Whiffin et al. (Whiffin et al., Citation2019, Citation2021) highlight how experiences of brain injury result in biographical disruption, with narrative structures capturing the tension or balance between continuities and discontinuities. In this current study, mothers tried to come to a place of resolve in relation to their child, while simultaneously seeing the unlived life, and drew upon discourses of continuity and change, presence and absence, normality and abnormality in their experiences of the child. Social attitudes of disability were evident within the dyad accounts and were generally negative, aligned with being “not normal” and a barrier to having a desired identity. Mothers spoke of struggling with both accepting their child as in some way changed or disabled alongside recognizing the continuous unchanged child. This sat in tension with the adolescents’ goal of finding ways to maintain or reclaim a social identity as “normal” upon which peer relationships often seemed dependent. In the process of adjustment towards some kind of equilibrium, our analysis bears some similarity to the conclusions of Muenchberger et al. (Citation2008) description of “tentative balance” in negotiating identity change.

The current findings therefore point to processes which echo typical adolescent developmental patterns and social roles of motherhood. However, following brain injury, specific issues related to negotiation of changes are clearly evident. Negotiation of these individual, shared and social aspects of self and identity is not linear and does not end in a resolved endpoint, despite the mothers’ intentions to “fix all” for the young people. This indicates that a notion of being “adjusted” might be limited and not reflect the lived reality of adolescents with brain injury and their mothers. Accounts have testified the enduring emotional responses to BI, which can progress well beyond the period of physical recovery (Muenchberger et al., Citation2008). Although participants did not describe reaching an adjusted end point, new meanings and relationships seemed to facilitate a tolerance of discrepancies and dilemmas and potential for a positive future for both members of the dyad. In this way, adaptation to life post injury, as noted by Whiffin et al. (Citation2021) is an ongoing process that requires significant existential and practical “work” on the part of all family members affected.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of the current study is the dual interview process to gain a rich relational perspective on the experience of identity changes post adolescent BI providing new insights into this specific aspect of family adaptation. In order to meet quality criteria for qualitatve research conducted from a critical perspective, we drew on the frameworks of Yardley (Citation2000) and Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985). Employing the dyadic approach helped address sensitivity to context. Use of reflexive diaries and supervision, and explicit tracking of analytic procedures contributed to the transparency of the analysis.

Attempts were made to maintain a reflexive stance on the analysis through use of a reflective diary and reflections on the construction of the analysis in supervision. Although findings were discussed with clinical professionals in the field, member checking was not conducted which allows for the possibility of transcription errors arising. Furthermore, the analysis could have been improved through further co-construction of themes directly with participants, which would improve the trustworthiness of findings. While description of participant characteristics and context might help with transferability of findings, a limitation of the study is the specific (White British, mothers and mainly sons) demographic of the sample and the specific lens of the lead researcher (CG, female, white, European, clinical psychologist) and the research team (white UK clinical psychologists). The sampling approach and sample size limited options for purposive and theoretical sampling to extend and develop the analysis over time. Therefore, the GT presented here should be seen as a partial and contextually constrained account. Further research with a larger and more diverse sample is needed, particularly given diversity in cultural and religious practices (as well as parental roles and relationships between sons and daughters) associated with motherhood and with identity in adolescence. There is a broader issue with lack of representation of men in family adaptation research in brain injury (Whiffin et al., Citation2021). Future research should address this in explicitly seeking to recruit fathers.

Implications and recommendations

Clinical implications of the current study include being aware of, valuing and adequately supporting mothers in the multifaceted roles that they perceive themselves as occupying, and being conscious of the identity-related dilemmas and tensions mothers might have regarding protection and autonomy of their adolescent child. For young people, the research points towards the importance of social relationships in constitution of self and identity, at this stage of development. This emphasizes the need to work with social contexts such as schools, peers, or interest groups as part of the rehabilitation process. Findings indicate a need to be appreciative of the pushes and pulls between mothers, adolescents, friends, and other family members as all negotiate discrepancies and tensions, and to not impose therapeutic or service models that are overly linear or structured to prevent discovery of new meanings (i.e., being overly focused on reducing deficits or achieving goals), or to conceptualize the outcome of intervention as an end point of “adjustment” but rather as an ongoing process.

Conclusions

This grounded theory study of mother-adolescent dyads following brain injury provides a novel analysis of identity changes in the parent–child context at this critical developmental stage. Further research to extend the insights gleaned from this work is required, in particular research and clinical intervention that are appropriately inclusive of and sensitive to both family and peer relationships, aligned with the family's own social and cultural context.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are extended to all participants for their time, and the clinical team for their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, V., Catroppa, C., Haritou, F., Morse, S., & Rosenfeld, J. (2005). Identifying factors contributing to child and family outcome 30 months after traumatic brain injury in children. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 76(3), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2003.019174

- Arendell, T. (2000). Conceiving and investigating motherhood: The decade’s scholarship. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1192–1207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01192.x

- Beadle, E. J., Ownsworth, T., Fleming, J., & Shum, D. (2016). The impact of traumatic brain injury on self-identity. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 31(2), E12–E25. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000158

- Ben-Yishay, Y. (2000). Post-avute neuropsychological rehabilitation: A holistic perspectove. In A. L. Christensen & B. P. Uzell (Eds.), Critical issues in neuropsychology, international handbook of neuropsychological rehabilitation (pp. 127–136). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Bloom, D. R., Levin, H. S., Ewing-Cobbs, L., Saunders, A. E., Song, J., Fletcher, J. M., & Kowatch, R. A. (2001). Lifetime and novel psychiatric disorders after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(5), 572–579. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-0035033378&partnerID=40&md5=a497c7e6928031fc465d78b5a631f50b https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200105000-00017

- Bohanek, J., Marin, K., Fivush, R., & Duke, M. (2006). Family narrative interaction and children's sense of self. Family Process, 45(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00079.x

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- Cantor, J., Ashman, T., Schwartz, M., Gordon, W., Hibbard, M., Brown, M., Spielman, L., Charatz, H. J., & Cheng, Z. (2005). The role of self-discrepancy theory in understanding post–traumatic brain injury affective disorders: A pilot study. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 20(6), 527–543. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-200511000-00005

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Compas, B. E., Jaser, S. S., Bettis, A. H., Watson, K. H., Gruhn, M. A., Dunbar, J. P., Williams, E., & Thigpen, J. C. (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 939–991. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000110

- Couchman, G., McMahon, G., Kelly, A., & Ponsford, J. (2014). A new kind of normal: Qualitative accounts of Multifamily Group Therapy for acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 24(6), 809–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2014.912957

- Daly, K. (1992). The fit between qualitative research and characteristics of families. In J. Gilgun, K. Daly, & G. Handel (Eds.), Qualitative methods in family research (pp. 3–12). Sage Publication.

- Di Battista, A., Catroppa, C., Anderson, V., Godfrey, C., & Soo, C. (2014). “In my before life”: Relationships, coping and post-traumatic growth in adolescent survivors of a traumatic brain injury. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 46(10), 975–983. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-1883

- Ellis-Hill, C., Payne, S., & Ward, C. (2008). Using stroke to explore the life thread model: An alternative approach to understanding rehabilitation following an acquired disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(2), 150–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280701195462

- Ellis-Hill, C., Thomas, S., Gracey, F., Lamont-Robinson, C., Cant, R., Marques, E. M., Thomas, P. W., Grant, M., Nunn, S., Paling, T., Thomas, C., Werson, A., Galvin, K. T., Reynolds, F., & Jenkinson, D. (2019). HeART of Stroke: randomised controlled, parallel-arm, feasibility study of a community-based arts and health intervention plus usual care compared with usual care to increase psychological well-being in people following a stroke. BMJ Open, 9(3), e021098.

- Erikson, E. H. (1959). Identity and the life cycle: Selected papers. Psychological Issues, 1(1), 1–171.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory.

- Gracey, F., Evans, J., & Malley, D. (2009). Capturing process and outcome in complex rehabilitation interventions: A “Y-shaped” model. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 19(6), 867–890. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010903027763

- Gracey, F., Palmer, S., Rous, B., Psaila, K., Shaw, K., O’Dell, J., Cope, J., & Mohamed, S. (2008). “Feeling part of things”: Personal construction of self after brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 18(5–6), 627–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010802041238

- Harter, S. (2015). Self-processes and developmental psychopathology. In Developmental psychopathology (Vol. 1, pp. 370–418). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470939383.ch11

- Haslam, C., Holme, A., Haslam, S., Iyer, A., Jetten, J., & Williams, W. (2008). Maintaining group memberships: Social identity continuity predicts well-being after stroke. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 18(5-6), 671–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010701643449

- James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology. Holt and company.

- King, G., Seko, Y., Chiarello, L. A., Thompson, L., & Hartman, L. (2020). Building blocks of resiliency: A transactional framework to guide research, service design, and practice in pediatric rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(7), 1031–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1515266

- Kreutzer, J., Mills, A., & Marwitz, J. (2016). Ambiguous loss and emotional recovery after traumatic brain injury. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 8(3), 386–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12150

- Levack, W., Boland, P., Taylor, W., Siegert, R., Kayes, N., Fadyl, J., & McPherson, K. (2014). Establishing a person-centred framework of self-identity after traumatic brain injury: A grounded theory study to inform measure development. BMJ Open, 4(5), e004630. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004630

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G.. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry (pp. 289–331). SAGE.

- Lyon, I., Fisher, P., & Gracey, F. (2021). Putting a new perspective on life”: A qualitative grounded theory of posttraumatic growth following acquired brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(22), 3225–3233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1741699

- Marcia, J. (1980). Identity in adolescence. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 159–187). Wiley.

- Micklewright, J., King, T., O'Toole, K., Henrich, C., & Floyd, F. (2012). Parental distress, parenting practices, and child adaptive outcomes following traumatic brain injury. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 18(2), 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617711001792

- Moscato, E. L., Peugh, J., Taylor, H. G., Stancin, T., Kirkwood, M. W., & Wade, S. L. (2021). Bidirectional effects of behavior problems and parenting behaviors following adolescent brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 66(3), 273.

- Muenchberger, H., Kendall, E., & Neal, R. (2008). Identity transition following traumatic brain injury: A dynamic process of contraction, expansion and tentative balance. Brain Injury, 22(12), 979–992. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050802530532

- Newman, B., Lohman, B., & Newman, P. (2007). Peer group membership and a sense of belonging: Their relationship to adolescent behavior problems. Adolescence, 42(166), 241–264.

- Nochi, M. (1998). “Loss of self” in the narratives of people with traumatic brain injuries: A qualitative analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 46(7), 869–878. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00211-6

- Nochi, M. (2000). Reconstructing self-narratives in coping with traumatic brain injury. Social Science and Medicine, 51(12), 1795–1804.

- Ownsworth, T. (2014). Self-identity after brain injury. Psychology Press.

- Ownsworth, T., & Haslam, C. (2016). Impact of rehabilitation on self-concept following traumatic brain injury: An exploratory systematic review of intervention methodology and efficacy. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 26(1), 1–35. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2014.977924

- Patton, G., Sawyer, S., Santelli, J., Ross, D., Afifi, R., Allen, N., Arora, M., Azzopardi, P., Baldwin, W., Bonell, C., Kakuma, R., Kennedy, E., Mahon, J., McGovern, T., Mokdad, A. H., Patel, V., Petroni, S., Reavley, N., Taiwo, K., … Viner, R. (2016). Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. The Lancet, 387(10036), 2423–2478. Lancet Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1

- Pidgeon, N., & Henwood, K. (1997). Using grounded theory in psychological research. In N. Hayes (Ed.), Doing qualitative analysis in psychology (pp. 245–273). Psychology Press.

- Rashid, M., Goez, H. R., Mabood, N., Damanhoury, S., Yager, J. Y., Joyce, A. S., & Newton, A. S. (2014). The impact of pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) on family functioning: A systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 7(3), 241–254.

- Roscigno, C., & Swanson, K. (2011). Parents’ experiences following children’s moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: A clash of cultures. Qualitative Health Research, 21(10), 1413–1426. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732311410988

- Roscigno, C. I., Swanson, K. M., Vavilala, M. S., & Solchany, J. (2011). Children's longing for everydayness: Life following traumatic brain injury in the USA. Brain Injury, 25(9), 882–894.

- Sharp, N. L., Bye, R. A., Llewellyn, G. M., & Cusick, A. (2006). Fitting back in: Adolescents returning to school after severe acquired brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 28, 767–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280500386668

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (2nd ed., pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall.

- Van Leer, E., & Turkstra, L. (1999). The effect of elicitation task on discourse coherence and cohesion in adolescents with brain injury. Journal of Communication Disorders, 32(5), 327–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9924(99)00008-8

- Wade, S. L., Taylor, H. G., Drotar, D., Stancin, T., Yeates, K. O., & Minich, N. M. (2003). Parent-adolescent interactions after traumatic brain injury: Their relationship to family adaptation and adolescent adjustment. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 18(2), 164–176.

- Walsh, R. S., Muldoon, O. T., Gallagher, S., & Fortune, D. G. (2015). Affiliative and ‘self-as-doer’ identities: Relationships between social identity, social support, and emotional status amongst survivors of acquired brain injury (ABI). Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 25(4), 555–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2014.993658

- Whiffin, C., Ellis-Hill, C., Bailey, C., Jarrett, N., & Hutchinson, P. (2019). We are not the same people we used to be: An exploration of family biographical narratives and identity change following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(8), 1256–1272. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2017.1387577

- Whiffin, C. J., Ellis-Hill, C., Bailey, C., Jarrett, N., & Hutchinson, P. J. (2019). We are not the same people we used to be: An exploration of family biographical narratives and identity change following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(8), 1256–1272. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2017.1387577

- Whiffin, C. J., Gracey, F., & Ellis-Hill, C. (2021). The experience of families following traumatic brain injury in adult populations: A meta-synthesis of narrative structures. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 123, 104043. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJNURSTU.2021.104043

- Yardley, L. (2000). Dilemmas in qualitative health research. Psychology and Health, 15(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440008400302

- Yeates, G., Henwood, K., Gracey, F., & Evans, J. (2007). Awareness of disability after acquired brain injury and the family context. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 17(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010600696423

- Yeates, K., Taylor, H., Walz, N., Stancin, T., & Wade, S. (2010). The family environment as a moderator of psychosocial outcomes following traumatic brain injury in young children. Neuropsychology, 24(3), 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018387