Abstract

Background: The literature on antipsychotic medication in psychosis lack systematization of the empirical knowledge base on patients’ subjective experiences of using antipsychotic drugs. Such investigations are pivotal to inform large-scale trials with clinically relevant hypotheses and to illuminate clinical implications for different sub-groups of individuals.

Aims: To re-analyze and summarize existing qualitative research literature on patient perspectives of using antipsychotic medication.

Method: A systematic literature search was performed in September 2018 (Protocol registration no. CRD42017074394). Using an existing framework of meta-analyzing qualitative research, full text evaluation was conducted for 41 articles. Thirty-two articles were included for the final synthesis.

Results: Four meta-themes were identified: (1) short-term benefits; (2) adverse effects and coping processes; (3) surrender and autonomy; (4) long-term compromise of functional recovery.

Conclusions: While largely positive about acute and short-term use, patients are more skeptical about using antipsychotic drugs in the longer term. The latter specifically relates to processes of functional and social recovery. The clinical conversations about antipsychotic medication need to include evaluations of contexts of patient experience level, patient autonomy processes, patient values and risk preferences, and patient knowledge and knowledge needs in addition to assessing the severity of symptoms of psychosis.

Introduction

Standardized clinical treatment guidelines recommend that individuals with psychosis be treated with antipsychotic medication in the acute phase as well as throughout the protracted phases of maintenance and recovery (APA, Citation2006; NICE, Citation2014). Antipsychotic medication has unequivocally proven effective in acute and short-term treatment (Bola, Kao, & Soydan, Citation2012; Lally et al., Citation2017; Leucht et al., Citation2017; Mackin & Thomas, Citation2011). Over the longer term, there are significant challenges related to this type of treatment.

First, a sizable share of those remitting after a first episode psychosis may be able to achieve a good long-term outcome with a very low dose or without antipsychotic drugs at all. Robust predictors for the early identification of these patients are still lacking, which may result in excessive use of antipsychotic medicine (Harrow, Jobe, Faull, & Yang, Citation2017; Moilanen et al., Citation2013; Murray et al., Citation2016; Wunderink, Nieboer, Wiersma, Sytema, & Nienhuis, Citation2013). Second, severe side effects, particularly associated with long-term use, include grey matter volume decrease and lateral ventricular volume increase (Fusar-Poli et al., Citation2013; Moncrieff & Leo, Citation2010), diabetes (Rajkumar et al., Citation2017), metabolic syndrome (Vancampfort et al., Citation2015), and reduced subjective quality of life and functioning (Wunderink et al., Citation2013; Wykes et al., Citation2017). Third, shared decision-making has become a stated priority in medical treatment in an attempt to reduce the use of compulsory treatment and increase subjective empowerment and adherence to treatments that are actively chosen (Leng, Clark, Brian, & Partridge, Citation2017). Hence, shared decision-making is a central part of the recovery paradigm (Alguera-Lara, Dowsey, Ride, Kinder, & Castle, Citation2017). This perspective has emerged resulting from a growing body of evidence showing a gap between the realities of those who use, refuse, or are forced to take antipsychotic medication and professionals and researchers (Faulkner, Citation2015; Moncrieff, Citation2013). Nevertheless, and despite non-adherence to treatment recommendations continuing to be considered a sizeable public health problem (Kane, Kishimoto, & Correll, Citation2013), few studies have investigated the effects of shared decision-making in mental healthcare settings (Boychuk, Lysaght, & Stuart, Citation2018; Schauer, Everett, del Vecchio, & Anderson, Citation2007; Slade, Citation2017; Stovell, Morrison, Panayiotou, & Hutton, Citation2016).

Large scale, prospective long-term, double-blind, controlled studies using clearly defined samples in terms of illness type, severity, and duration evaluating treatment effect are lacking (Sohler et al., Citation2016). These types of studies are essential to reveal how antipsychotic treatment affects critical functioning throughout the course of illness (Rhee, Mohamed, & Rosenheck, Citation2018; Zipursky & Agid, Citation2015). Also, meta-analyses of qualitative studies are needed to systematically describe and summarize the growing empirical qualitative knowledge base on service users’ subjective perspectives on using antipsychotic drugs. Such studies are essential to inform large-scale trials with clinically relevant hypotheses, as well as to illuminate clinical implications for different sub-groups of individuals.

Objective

The aim of this study is re-analyze and summarize the existing qualitative research literature on patient perspectives on using antipsychotic drugs.

Method

Qualitative meta-analyses offer secondary analyses of multiple primary studies addressing the same research question (Finfgeld, Citation2003; Timulak, Citation2014). To ensure comprehensive and transparent reporting of methods and results, this qualitative meta-analysis was performed in three steps: first, the PRISMA guidelines (Hutton et al., Citation2015; Moher et al., Citation2015) were applied for search strategy and data extraction. Second, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist (CASP, Citation2013) was used for quality appraisal and final study inclusion. Third, data analysis followed an established framework for meta-analyzing qualitative studies (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008; Timulak, Citation2009). The protocol was registered at PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews in August 2017 (Registration no. CRD42017074394).

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was performed using the following electronic databases: PsycINFO, CINAHL, Embase, Medline, Web of Science, SCOPUS, and Cochrane Library. Search terms were developed to identify qualitative research exploring experiences of taking anti-psychotic medications from a first-person perspective, and final search terms were adapted accordingly to fit the different databases’ search engines. In addition to relevant subject headings, all searches included the following terms: (antipsychotic* or neuroleptic* or aripiprazole or clozapine or molindone or nialamide or olanzapine or quetiapine or reserpine or risperdone or sulpiride or tetrabenazine or acepromazine or azaperone or benperidol or butaclamol or chlorpromazine or chlorprothixene or clopenthixol or clozapine or droperidol or etazolate or flupenthixol or fluphenazine or fluspirilene or haloperidol or loxapine or lurasidone hydrochloride or mesoridazine or methiothepin or methotrimeprazine or molindone or ondansetron or paliperidone palmitate or penfluridol or perazine or perphenazine or pimozide or prochlorperazine or promazine or quetiapine fumarate or raclopride or remoxipride or ritanserin or spiperone or sulpiride or thioridazine or thiothixene or tiapride hydrochloride or trifluoperazine or trifluperidol or triflupromazin) AND (psychosis* or psychoses* or psychotic* or schizo* or delusio* or hallucinat* or hallucinos* or paranoi*) AND (focus group* or qualitative research or qualitative study or qualitative studies or qualitative method* or phenomenolog* or interpretive or interpretative or hermeneutic* or “first person” or "self-report*" or narrativ* or “grounded theory” or “field stud*”). The search query was approved by an information scientist and was limited to title, abstract, and key words. In addition, a manual literature search was performed using reference lists of reviews and meta-analyses. No time restriction period was applied for publication inclusion. The final search was performed 25 September 2018.

Inclusion criteria

The included articles were required to meet all of the following criteria:

Empirical study published in English language in peer reviewed journals.

Derived from a sample meeting criteria (DSM/ICD) for a psychotic disorder.

Using qualitative methods for both data collection and data analysis (minimum score of 1 (satisfactory quality) on overall study rating. See , right column).

Explicitly explore first-person perspectives of taking antipsychotic medication, including both first- and second-generation drugs.

Table 1. Quality appraisal.

Data material and data analysis

All potential studies were exported into a reference citation manager and duplications were removed. Two independent reviewers (M. V. and K. O. L.) separately performed the screening of titles and abstracts. Based on this screening they suggested a list of articles eligible for full text review (N = 41). Next, a consensus meeting was arranged with J. B., K. O. L., C. M., and M. V. Here, eligible articles were critically assessed based on full-text review using a two-step procedure; (1) a systematic quality appraisal framework (CASP, Citation2013), including a separate quality evaluation of each of the eligible studies according to the 10 CASP criteria (see for details), and (2) an established framework for meta-analyzing qualitative data (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008; Timulak, Citation2009) and consensual qualitative research (Hill, Thompson, & Williams, Citation1997) using the following steps:

J. B., K. O. L., M. V., A. H., and C. M. read all papers independently and made preliminary analytic notes establishing tentative and characteristic themes. A theme is a construct “that captures something significant about the data in relation to the research question and represent some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set” (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). Themes were secondary analysis of primary study reported categories or themes. We aimed to develop nuanced and in-depth knowledge about the phenomenon of focus by analyzing both commonalities as well as variations in the primary data.

A meeting with J. B., K. O. L., M. V., and C. M. was held to compare preliminary analyses and decide structure of meta-themes, and development of a model of interrelated processes between meta-themes.

To ensure representativeness and overall relevance across the data material, J. B. and C. M. re-read primary articles, searched for illustrative quotes, and started the write-up of the findings.

Last, the tentative model of findings, with illustrative quotes, was sent to A. H. who served as a critical auditor assessing the interpretations made through our descriptions of the central organizing concepts.

Next, the consensus evaluation of the 41 eligible studies was sent to an auditor (A. H.) for critical evaluation of the data extraction process. The auditor carried out the same 2-step analytic process as described above. L. D. had a general role, including interlinking the study findings to the literature and discussing their clinical implications.

Methodological integrity and validity checks

Performing methodological and validity checks is recommended practice when conducting qualitative meta-analyses (Timulak, Citation2009), and such procedures ensure that the interpretation of data is shared by multiple researchers (Levitt, Pomerville, & Surace, Citation2016). The following methodological integrity and validity checks were performed in order to enhance the quality of our analysis:

Inter-rater reliability measures (Kappa) between K. O. L. and M. V. while screening and selecting studies were performed to ensure that inclusion criteria were clearly stated and that papers were assessed equally.

Consensus processes were chosen to foster multiple interpretations and perspectives of the data. The overall aim of consensual research is to improve decision quality through valuing diversity in viewpoints, equal involvement and mutual respect among the involved researchers (Hill et al., Citation2005) by facilitating an open dialogue throughout the screening, analysis and write-up process. All researchers read through the data papers and independently established a tentative framework of results prior to the analysis seminar to stimulate multiple perspectives and mutual involvement.

A critical auditor was selected to review and provide detailed feedback on each stage of the analysis and writing process. In accordance with Hill (Citation2012), the critical auditor’s role was to check whether important material was represented in the meta-themes and that the wording captured the essence of data material and the validity of the structure of findings.

Keeping the first-person account in mind while interpreting the data was sought to accommodate the voice of the patient. Practically, this meant that we attended carefully to and prioritized patient quotes while analyzing the data, and we also searched for illustrative quotes to inform the writing of the findings.

Results

Search results

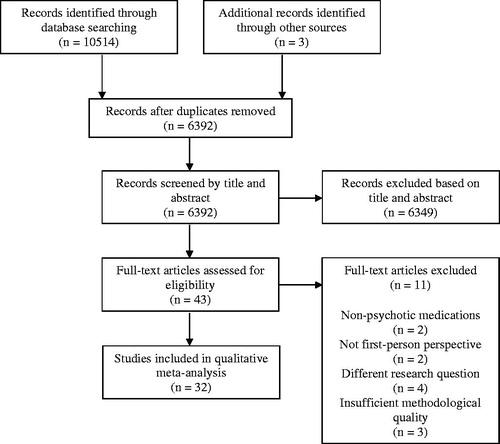

The electronic search returned 10,514 articles. A hand search of reference lists of reviews and meta-analyses returned a further three articles. After duplicates were removed, there were left 6392 articles. Six thousand three hundred forty-nine articles were excluded after a review of title and abstract, yielding them outside inclusion criteria. Full text evaluation was conducted for 43 articles, of which 32 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included for the final analysis. The main reasons for exclusion were the following: the study sample did not consist of participants meeting criteria (DSM/ICD) for a psychotic disorder or diagnosis of some/all participants was unclear or not stated, unclear, or not stated pharmacological treatment, did not explore first-person perspectives of taking anti-psychotic medication, or not involving qualitative analysis of qualitative data (see for details on the review process). Inter-rater reliability for inclusion of articles was satisfactory-high (Kappa = 0.76).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the reviewing process according to PRISMA (adapted from Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Citation2009).

Quality appraisal and study characteristics

Of the included studies (CASP-based assessment, see ), 19 studies achieved satisfactory and 11 studies excellent total score. Generally, contextual, reflexive and ethical issues achieved lowest scores. Across articles, a total of 519 participants were included and the mean number of participants was 16.7 (SD = 7). Participants’ age ranged from 13 to 70 years and mostly came from Anglo-American cultures (see Supplementary material, Sample and context). Mean age was not possible to calculate as several studies only included age range. Approximately 42% were female participants. A precise number was not possible to estimate due to missing reports of gender in some studies. While all included papers comprised experiences of taking some type of antipsychotic medication, 20 studies did not specify drug type. Five studies applied second generation and five studies used combined first- and second-generation drugs. The studies originated from a variety of countries, including Australia (4), Brazil (1), Canada (3), China (1), Iran (1), Ireland (1), Norway (4), Sweden (2), Taiwan (1), United Kingdom (12), and United States (2). A descriptive overview of included studies is presented in Supplementary material.

Meta themes

Four meta-themes resulted from the meta-analytic procedures, in which we look for both thematic divergence and convergence in the results sections of the included papers. The meta-themes comprise the first-person experiential domains of (a) short-term benefits, (b) adverse effects and coping processes, (c) surrender and autonomy, and (d) the long-term compromise of functional recovery. The degree of representativeness held by the different meta-themes could be indicated by how many of the included papers contribute to the theme. provides a summary of which individual papers contribute to the four meta-themes and indicates coverage. In the following, we detail descriptions of each meta-theme and provide one or more quotes from contributing articles for illustrative purposes.

Table 2. Number and coverage.

Short-term benefits

In the acute and early phase, patients described themselves as particularly affected by severe symptoms. Psychotic states, such as paranoia, mental chaos, and extreme fear, were perceived as terrifying and made patients highly motivated to reduce the burden of these symptoms. Antipsychotic medication was, particularly when reflected on retrospectively, seen as efficient in reducing active psychosis symptoms in the acute phase, but also in preventing relapse and re-hospitalization. Achieving functional recovery in the later course, were by many seen as dependent on first reducing psychosis symptoms. Thus, the threshold to commit to short-term antipsychotic treatment was lower than when compared to long-term use.

I’m very satisfied with the treatment I received. I got a lot of help. I felt very safe on the ward. I trusted NN (psychiatrist). She was fantastic … all the staff was actually like that…. I was difficult to deal with, I must admit, I wasn’t a very easy patient. I wasn’t violent, but I refused everything and initially I didn’t want to take any medicine. Nevertheless, they were able to convince me. I decided to use my antipsychotic medication for one or perhaps two years, then I thought I would be able to sustain myself without it. I will adhere to my doctor’s recommendation (Yeisen, Bjornestad, Joa, Johannessen, & Opjordsmoen, Citation2017)

Adverse effects and coping processes

Antipsychotic treatment was not seen as unconditionally good. Finding an expedient drug and optimal dosage was seen as a struggle to find a balance between positive effects and unwanted side effects. The vast majority of studies described serious side effects. Reducing acute phase psychotic symptoms was mostly perceived to outweigh side effects. During this stage, side effects were not perceived as particularly destructive. However, when psychotic symptoms abated, most patients found side effects exceedingly detrimental to their mental health and well-being. The significance of these experiences was also emphasized in the article titles in which long-term treatment was described in terms such as “the least worst option” (Morant, Azam, Johnson, & Moncrieff, Citation2017) and “the greater of two evils?” (Hagen, Nixon, & Peters, Citation2010), and on-going use was dependent on positive effects outweighing negative ones.

This drug has caused me a lot of evil, but I need it. It helps in daily life. But there’s the side effect too, which bothers in daily life as well (Vedana & Miasso, Citation2014)

The first time after taking it I couldn’t get up for 12 h. Now 2–4 h after taking it I can get up but I can’t get out of bed. It makes me dark under my eyes. It makes me feel weak for hours. I have somehow to get used to it (Gray & Deane, Citation2016)

Side effects perceived to cause functional decline, such as reduced mental capacity and sedation, were seen as the most compromising. Sexual dysfunction and weight gain were emphasized in some papers. Patients described a strong association between side effects limiting daily functioning and non-adherence to antipsychotic drugs, often against medical recommendations. The following quote illustrates the disruptive severity of the side-effects to the person’s achievement of his or her own goals.

The medication makes me put on weight actually, reduces my motivation, changes other people’s attitudes towards me for the worse, makes me feel depressed, sometimes I’m restless, sometimes has a negative effect on my day to day living. Well just that it makes me so physically disabled, so it reduces my ability to function normally (Morant et al., Citation2017)

Surrender and autonomy

Communication early in the course of treatment were often described from the patient perspective as a process of surrendering, in which patients felt compelled to trust professional judgment and recommendations, including treatment with antipsychotic medication. Surrendering was a highly stressful process which required patients to develop a degree of trust in the professional person’s being knowledgeable and (at least) benign. Particularly, in cases of severe paranoia and lessened insight, trust was hard to accomplish. This often led to poor adherence or forced antipsychotic treatment.

So I was compliant with medication throughout my hospitalization… . Still sceptical, I think … when you’re in the hospital, it’s best to take your medication. You tend to get out faster [laughter] if you do that (Tranulis, Goff, Henderson, & Freudenreich, Citation2011)

Most patients perceived communication about antipsychotic treatment to be primarily a one-way interaction in the short-term perspective. They rarely felt involved in treatment decisions, and often had unanswered questions concerning the adverse effects and treatment rationale. This type of communication was experienced as a disregard of personal treatment preferences, a lack of trust, and ultimately an invalidation of the personhood of the patient who struggled with psychotic symptoms. Such a perceived imbalance often led to poor collaboration with treatment providers, feelings of powerlessness and resignation, and termination of antipsychotic treatment. Furthermore, many patients perceived professionals as applying sanctions when they did not submit to the proposed treatment regime. Such a use of power was experienced as particularly disturbing. The following two quotes illustrate this tension between surrender, information, and collaboration.

At the end of the day it should be an individual’s choice what they put into their body and I’m making a choice and I mean, whether that choice is good or bad? But if you were given more support to make the choices, then they’d probably be less disastrous because you wouldn’t just be left on your own doing it by your own means (Geyt, Awenat, Tai, & Haddock, Citation2017)

He told me that [unless I took the medication] I would never be able to go to a normal school … and that I would never be able to finish high school normally. And that I would never graduate. And that I needed to get used to the idea that I would be on medication for the rest of my life … that’s what he actually told me (Hagen, Nixon, & Peters, Citation2010)

During the early stages, when patients suffered from cognitive impairments and florid symptoms, they saw that it was necessary for professionals to take sufficient time to provide, and often repeat, important information. Shortly after the acute phase – which for many patients involved reduced psychotic symptoms and improved functioning – patients emphasized that was pivotal to receive thorough information about the biology of psychosis, effects and side effects of antipsychotic medications, and the expected duration of use, all put forward in honest and understandable, everyday language.

Also, in the longer term, patients saw it as essential that communication was reciprocal, respectful, and involved a high degree of user involvement both in treatment planning and treatment delivery. Obtaining proper information, either from the treatment provider or from personal reading, and thus becoming knowledgeable about one’s own condition and process, seemed important when moving from the short-term horizon to thinking about living with the challenges over a longer term perspective. Moreover, patients preferred professionals to view recovery as an individual matter and to appreciate that antipsychotics were one of many tools and not necessarily the main ingredient in recovery. A perceived disproportionate or exclusive focus on antipsychotic drugs was described as being in conflict with participants’ ideas of improving as a social process, and often resulted in resistance and non-adherence.

I think therapy was beneficial. Not so much the drugs. The overly vast focus on drugs made me angry. My problems were not about that. What worked was when I told my therapist how I was doing, and he managed to tell me in another way why I felt that way…. I think my Community Psychiatric Nurse takes on board what I say she’s quite good, I can like test the waters with her and then we will think about it and not just on one single answer but look for a variety of avenues to follow (Bjornestad, Davidson, et al., Citation2017)

Other information sources, such as the Internet, social media, and peers, augmented the dialogue between patients and professionals. Gaining knowledge, comparing drug effects, and learning from others with first-hand experience of antipsychotic treatment were commonly used strategies in moving from an initial surrender to authority to forming an autonomous opinion on the process, with an increasing sense of personal agency as a result. Patients regularly used this information to challenge expert decisions and negotiate treatment choices.

See we talk to each other and I know from a few of them in here what they are taking so I learn from them. We know by the colors and we know what are good ones and also the ones that don’t help us much. The doctors they try a few and we know from speaking to each other in here which ones we take that help the most. So we learn from each other and compare how the tablets work. It’s easy see when someone changes tablets we can see how they behave and ask what they got to help (Stewart, Anthony, & Chesson, Citation2010)

Long-term compromise of functional recovery

Long-term antipsychotic use was often perceived to disturb individual efforts and the person’s sense of agency in overcoming psychosis. Both these aspects were assessed as necessary to enable the transition from being in need of care to reaching functioning levels necessary for satisfactory participation in society. Medication made it difficult to parse out the improvement resulting from the person’s decisions and actions – as opposed to the drugs – and thereby reduced the perceived impact of individual efforts. Long-term use of antipsychotic medication also gave patients a feeling of being stigmatized and deviant, and hence not suitable for social inclusion and citizenship. The following quote illustrates this theme.

When you go out it’s like advertising you have a mental illness, so the side effects draw attention to the fact that you have a mental illness. And even though you might be quite well mentally, the side effects stigmatize you…you can’t even go over to your sister’s place and go out into the yard without the neighbors thinking she’s got someone there who is mentally ill…you know your legs are going up and down all the time and they think you’re a lunatic. It’s like wearing a sign on your forehead (Usher, Citation2001)

Long-term use was seen as a balancing act between anxieties about relapse, which worked as a reminder not to quit medications, and anxieties about irreparable bodily damage caused by the drugs, which was an incentive to terminate use. Another motivation for continued use was fear-based statements from professionals, including warnings about the dire consequences of decreasing or terminating antipsychotic treatment. This tug of war was perceived by many as a drug labyrinth with no possibilities for escape, which again gave rise to a sense of inadequacy, emotional flattening and fear. The following two quotes illustrate this theme.

It was like the lesser of two evils…. You can be scared and paranoid or you can have no saliva. I was going to take the no saliva but…it was trial and error…I’m glad I got to the stage…where I actually feel like they are working (Murphy et al., Citation2015)

When I told him again for the third time that I was trying to get off these drugs, all he could do was get mad at me. He started ranting on about how symptoms would come back 10% worse every time I stopped taking the medication. It was crazy, and I was thinking “so every time you put me on the medications so that I can’t feel anything, I’m going to get more and more psychotic every time I finally get the courage to take myself off them? (Hagen et al., Citation2010)

Conversely, for those with a more positive perception of long-term use, it was essential to adapt use to everyday settings, including work, parenting, and social life. Here, reducing side effects through either dose-reduction or through manipulating the time points for when the hardest side effects were hitting – e.g. taking drugs in the middle of the night instead of in the morning – were seen as crucial. This usually involved some experimenting alone and in dialogue with professionals. The following quote illustrates this process of personalization and negotiating degrees of freedom in order to achieve autonomy.

They are so strong so I set the alarm clock to half past three in the morning, take the medicine and go back to sleep. Then I wake up at half past seven and get up. If I had taken them at half past seven, as prescribed, my work mates would think that I was drunk when I came to work (Bülow, Andersson, Denhov, & Topor, Citation2016)

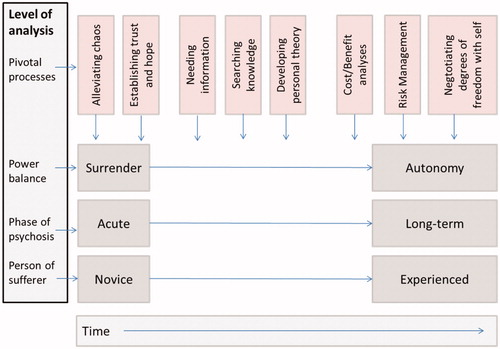

A proposed model of processes between meta-themes

presents a first-person experiential model of using antipsychotic medication based on the meta-analysis of 32 included studies. The model proposes meta-thematic content organized on a time continuum, including the experience level of the person suffering from psychosis, illness phases, and power dynamics. The developmental process from being a novice user of mental health services in general, and antipsychotic medication in particular, to becoming an experienced patient, was pivotal. Meanings attached to antipsychotic medications were significantly different when the horizon was the short-term acute situation rather than the long-term recovery-oriented perspective. While the need to be helped by medication and experts to silence chaos and terror overshadowed other needs when inexperienced patients went through acute phases, a personal cost–benefit analysis and a risk management analysis became central at later stages. Hence, evolving knowledge, value-based opinions, and need for a sense of personal responsibility seems to constitute an overarching process.

Developing autonomy with regard to one’s own suffering and interactions with mental health services appeared to be an organizing principle that followed a similar path. Achieving autonomy seemed to emerge from increased knowledge via information from professionals, peers and, importantly, one’s own explorations and experimentations. Becoming knowledgeable helped the person to develop autonomy in the face of his or her initial sense of surrender, and subsequently to establish a sense of personhood. This sense of self (Davidson & Strauss, Citation1992) has long been argued to be central to recovery processes. From the perspective of becoming autonomous, cost–benefit analyses and risk evaluations appeared to change throughout the course of suffering. Side effects that were acceptable for the short term seemed autonomously evaluated vis-à-vis the long-term goals and values of the individual. Risk negotiated from within oneself yielded different results than when the doctor was responsible for the risk matrix. For illustration, in the included study by Geyt et al. (Citation2017), one quote states that the rational choice from the doctor’s perspective is understandably to tolerate as little risk on the patients’ behalf as possible, whereas when a patient is considering pros and cons, a certain degree of risk is a necessary part of recovery.

Discussion

Clinical implications

Study findings shed light on how the prescribing and use of antipsychotic drugs should be tailored to patients’ individual symptoms, functioning, and experience level. The meta-analytic results echo previous research findings suggesting antipsychotic medication as an efficient treatment of psychosis during the acute phase and short-term (Leucht et al., Citation2017; Sohler et al., Citation2016). A reported challenge in psychosis is that a substantial sub-group of patients stop taking antipsychotic drugs before recommendations indicate (Kane et al., Citation2013). Rather than assuming that this decision is due to denial or a lack of insight, as is often suggested, it should be explored whether such decision results from an autonomous process in which the more experienced patient needs to negotiate level of perceived freedom vis-à-vis his or her own psychotic experiences. In line with other research on user experiences, it seems pivotal for treatment to be efficient to early identify these types of discrepancies in professionals’ and service users’ views (Davidson, Citation1992; Russo, Citation2018). Our results underscore that patients should be continuously informed about antipsychotic treatment by many sources. Results support that antipsychotic drugs are best presented as a part of a comprehensive treatment package – including, for example, psychotherapy, family therapy, and/or rehabilitation supports – and not as the exclusive or primary tool for recovery.

Further, information appears to best facilitate successful use when delivered in a manner that supports and sustains the person’s concerns with his or her autonomy and individual efforts. A straightforward and honest use of everyday language can promote a collaborative framework (Dixon, Holoshitz, & Nossel, Citation2016; Thomas, Citation2015), and a respectful tone was considered a powerful remedy for early discontinuation. Patients described preferring communications to be especially clear and to include repetition of important aspects over time.

Over the longer-term, treatment professionals should be sensitive to changes in patients’ needs and treatment preferences. In particular, introducing functional and social aspects into the dialog, aspects previously shown critical for remission and recovery (Bjornestad, Joa, et al., Citation2016; Bjornestad, ten Velden Hegelstad, et al., Citation2017; Davidson et al., Citation2001; Marder & Galderisi, Citation2017), seems crucial for a fruitful dialogue to develop and to promote a successful long-term outcome. Here, a system-wide implementation of safeguards and checkpoints to monitor the quality and impact of patients’ experiences related to treatment, including antipsychotic drugs, seems called for. Findings advocate, in addition to evaluating the severity of symptoms of psychosis in themselves, contexts of patient experience level, patient autonomy processes, patient values and risk preferences, and patient knowledge and knowledge needs, need to be included in the clinical conversation about medication use.

Limitations

The qualitative meta-analysis is relatively comprehensive with regard to the number of sampled articles, but might be limited by the variability between the included studies. By which method and design first-person experiences with anti-psychotic medication are studied differs in the sample. Thus, concepts such as degree of coverage for individual meta-themes should be interpreted with caution. Programmes of qualitative studies in which a field agreeing on a set of interview schedules and methods to use for a given research question for a particular period in time would be a potential development. Another potential limitation is that the data material in this meta-analysis includes three articles reported by some of the present authors (J. B., L. D., and M. V.), suggesting a risk of bias. To overcome this limitation we have composed a group of researchers in which half had not taken part in previous studies, and established rigorous reflexivity processes as described in the methods section, to ensure stringency. The critical auditor (A. H.) in this study was not involved in the research projects that constitute our data material and is, therefore, independent. All authors have a background as clinical psychologists, which may have contributed to an important analytical distance in carrying out the study. In so doing, however, the research team does not include people with first-hand experiences with antipsychotic medication or the groups of professionals (medical doctors and nurses). Coverage (see ) should also be interpreted with caution, as lack of coverage can be due to slight differences in scope and interview schedules in heterogeneous individual studies. Finally, grey literature was not included. While this allowed for strict and transparent inclusion criteria and legitimacy as the peer-review processes in established scientific journals ensure a basic level of quality, important first-person descriptions may have been overlooked in this process. We recommend that future studies systematize the grey literature of people’s experiences of using antipsychotic medication. This limitation will in this study typically raise the risk of reporting bias, implying that the included studies represent selective research dissemination.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to all phases of the paper. Associate Professor Jone Bjornestad: had the idea for the article, significant contribution in the literature search, analysis, model development and writing and is the guarantor of this article. Clinical psychologist and research fellow. Kristina O. Lavik: had a significant contribution in the literature search, analysis and writing. Professor Larry Davidson: was central in interlinking the study findings to the literature and discussing their clinical implications. Associate Professor Aslak Hjeltnes: served as a critical auditor for critical evaluation of the data extraction process. Professor Christian Moltu: had a significant role in full-text review, analysis, model development, and writing of the article. Associate Professor Marius Veseth: had a significant contribution in the literature search, analysis, model development, and writing of this article.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (40.5 KB)Acknowledgements

A special thanks to the staff at the Medical Library of Stavanger University Hospital for assistance with the literature search.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alguera-Lara, V., Dowsey, M. M., Ride, J., Kinder, S., & Castle, D. (2017). Shared decision making in mental health: The importance for current clinical practice. Australasian Psychiatry, 25(6), 578–582. doi:10.1177/1039856217734711

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2006). Practice Guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders: Compendium. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Pub.

- Bjornestad, J., Bronnick, K., Davidson, L., Hegelstad, W. T. V, Joa, I., … Melle, I. (2016). The central role of self-agency in clinical recovery from first episode psychosis. Psychosis, 1–9, 140–148. doi:10.1080/17522439.2016.1198828.

- Bjornestad, J., Davidson, L., Joa, I., Larsen, T. K., Hegelstad, W. T. V, Langeveld, J., … Bronnick, K. (2017). Antipsychotic treatment: Experiences of fully recovered service users. Journal of Mental Health, 1–7, 264–270. doi:10.1080/09638237.2017.1294735

- Bjornestad, J., Joa, I., Larsen, T. K., Langeveld, J., Davidson, L., ten Velden Hegelstad, W., … Johannessen, J. O. (2016). “Everyone Needs a Friend Sometimes”–Social predictors of long-term remission in first episode psychosis. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1491. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01491

- Bjornestad, J., ten Velden Hegelstad, W., Joa, I., Davidson, L., Larsen, T. K., Melle, I., … Bronnick, K. (2017). “With a little help from my friends” social predictors of clinical recovery in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Research, 255, 209–214. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.041

- Bola, J. R., Kao, D. T., & Soydan, H. (2012). Antipsychotic medication for early-episode schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38(1), 23–25. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbr167

- Boychuk, C., Lysaght, R., & Stuart, H. (2018). Career decision-making processes of young adults with first-episode psychosis. Qualitative Health Research, 28(6), 1016–1031. doi:10.1177/1049732318761864

- Bülow, P., Andersson, G., Denhov, A., & Topor, A. (2016). Experience of psychotropic medication–An interview study of persons with psychosis. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(11), 820–828. doi:10.1080/01612840.2016.1224283

- Carrick, R., Mitchell, A., Powell, R. A., & Lloyd, K. (2004). The quest for well‐being: A qualitative study of the experience of taking antipsychotic medication. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 77(1), 19–33. doi:10.1348/147608304322874236

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). (2013). Qualitative Research Checklist. Retrieved from http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_951541699e9edc71ce66c9bac4734c69.pdf

- Chang, Y. T., Tao, S. G., & Lu, C. L. (2013). Qualitative inquiry into motivators for maintaining medication adherence among Taiwanese with schizophrenia. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 22(3), 272–278. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00864.x

- Cocoman, A. M., & Casey, M. (2018). The physical health of individuals receiving antipsychotic medication: A qualitative inquiry on experiences and needs. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(3), 282–289. doi:10.1080/01612840.2017.1386744

- Das, A. K., Malik, A., & Haddad, P. M. (2014). A qualitative study of the attitudes of patients in an early intervention service towards antipsychotic long-acting injections. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 4(5), 179–185. doi:10.1177/2045125314542098

- Davidson, L., Haglund, K. E., Stayner, D. A., Rakfeldt, J., Chinman, M. J., Kraemer Tebes, J. (2001). “It was just realizing… that life isn't one big horror": A qualitative study of supported socialization. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 24(3), 275. doi:10.1037/h0095084

- Davidson, L., & Strauss, J. S. (1992). Sense of self in recovery from severe mental illness. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 65(2), 131–145. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1992.tb01693.x

- Dixon, L. B., Holoshitz, Y., & Nossel, I. (2016). Treatment engagement of individuals experiencing mental illness: Review and update. World Psychiatry, 15(1), 13–20. doi:10.1002/wps.20306

- Faulkner, A. (2015). Randomised controlled trials: The straitjacket of mental health research? (1st ed.). McPin Talking Point Papers. Retrieved from http://mcpin.org/wp-content/uploads/talking-point-paper-1.pdf

- Finfgeld, D. L. (2003). Metasynthesis: The state of the art-so far. Qualitative Health Research, 13(7), 893–904. doi:10.1177/1049732303253462

- Fusar-Poli, P., Smieskova, R., Kempton, M. J., Ho, B. C., Andreasen, N. C., & Borgwardt, S. (2013). Progressive brain changes in schizophrenia related to antipsychotic treatment? A meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(8), 1680–1691. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.06.001

- Gault, I., Gallagher, A., & Chambers, M. (2013). Perspectives on medicine adherence in service users and carers with experience of legally sanctioned detention and medication: A qualitative study. Patient Preference and Adherence, 7, 787–799. doi:10.2147/PPA.S44894

- Gee, L., Pearce, E., & Jackson, M. (2003). Quality of life in schizophrenia: A grounded theory approach. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1(1), 31. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-31

- Geyt, G. L., Awenat, Y., Tai, S., & Haddock, G. (2017). Personal accounts of discontinuing neuroleptic medication for psychosis. Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 559–572. doi:10.1177/1049732316634047

- Gray, R., & Deane, K. (2016). What is it like to take antipsychotic medication? A qualitative study of patients with first‐episode psychosis. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 23(2), 108–115. doi:10.1111/jpm.12288

- Hagen, B. F., Nixon, G., & Peters, T. (2010). The greater of two evils? How people with transformative psychotic experiences view psychotropic medications. Ethical Human Psychology and Psychiatry, 12(1), 44–59. doi:10.1891/1559-4343.12.1.44

- Harrow, M., Jobe, T. H., Faull, R. N., & Yang, J. (2017). A 20-year multi-followup longitudinal study assessing whether antipsychotic medications contribute to work functioning in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 256, 267–274. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.069

- Hill, C. E. (2012). Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Hill, C. E., Knox, S., Thompson, B. J., Williams, E. N., Hess, S. A., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 196–205. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196

- Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., & Williams, E. N. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. Counseling Psychologist, 25(4), 517–572. doi:10.1177/0011000097254001

- Hui, C. L., Lo, M. C., Chan, E. H., Chen, E. S., Ko, R. W., Lee, E. H., … Chen, E. Y. (2016). Perception towards relapse and its predictors in psychosis patients: A qualitative study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 11(3), 224–228. doi:10.1111/eip.12378

- Hutton, B., Salanti, G., Caldwell, D. M., Chaimani, A., Schmid, C. H., Cameron, C., … Jansen, J. P. (2015). The PRISMA Extension Statement for Reporting of Systematic Reviews Incorporating Network Meta-analyses of Health Care Interventions: Checklist and explanations PRISMA extension for network meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 162(11), 777–784. doi:10.7326/M14-2385

- Kane, J. M., Kishimoto, T., & Correll, C. U. (2013). Non‐adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: Epidemiology, contributing factors and management strategies. World Psychiatry, 12(3), 216–226. doi:10.1002/wps.20060

- Lally, J., Ajnakina, O., Stubbs, B., Cullinane, M., Murphy, K. C., Gaughran, F., & Murray, R. M. (2017). Remission and recovery from first-episode psychosis in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of long-term outcome studies. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 211(6), 350–358. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.117.201475

- Leng, G., Clark, C., Brian, K., & Partridge, G. (2017). National commitment to shared decision making. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 359, j4746. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4746

- Leucht, S., Leucht, C., Huhn, M., Chaimani, A., Mavridis, D., Helfer, B., … Davis, J. M. (2017). Sixty years of placebo-controlled antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: Systematic review, Bayesian meta-analysis, and meta-regression of efficacy predictors. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(10), 927–942. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16121358

- Levitt, H. M., Pomerville, A., & Surace, F. I. (2016). A qualitative meta-analysis examining clients’ experiences of psychotherapy: A new agenda. Psychological Bulletin, 142(8), 801–830. doi:10.1037/bul0000057

- Lorem, G. F., Frafjord, J. S., Steffensen, M., & Wang, C. E. (2014). Medication and participation: A qualitative study of patient experiences with antipsychotic drugs. Nursing Ethics, 21(3), 347–358. doi:10.1177/0969733013498528

- Lloyd, H., Lloyd, J., Fitzpatrick, R., & Peters, M. (2017). The role of life context and self-defined well-being in the outcomes that matter to people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 20(5), 1061–1072. doi:10.1111/hex.12548

- Mackin, P., & Thomas, S. H. (2011). Atypical antipsychotic drugs. BMJ, 342(7798), 650–654. doi:10.1136/bmj.d1126

- Marder, S. R., & Galderisi, S. (2017). The current conceptualization of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 14–24. doi:10.1002/wps.20385

- McCann, T. V., & Clark, E. (2004). Embodiment of severe and enduring mental illness: Finding meaning in schizophrenia. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 25(8), 783–798. doi:10.1080/01612840490506365

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., … Stewart, L. A. & PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematisk Reviews, 4(1), g7647. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

- Moilanen, J., Haapea, M., Miettunen, J., Jääskeläinen, E., Veijola, J., Isohanni, M., & Koponen, H. (2013). Characteristics of subjects with schizophrenia spectrum disorder with and without antipsychotic medication – A 10-year follow-up of the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort study. European Psychiatry, 28(1), 53–58. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.06.009

- Moncrieff, J., & Leo, J. (2010). A systematic review of the effects of antipsychotic drugs on brain volume. Psychological Medicine, 40(09), 1409–1422. doi:10.1017/S0033291709992297

- Moncrieff, J. (2013). The bitterest pills: The troubling story of antipsychotic drugs. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Morant, N., Azam, K., Johnson, S., & Moncrieff, J. (2017). The least worst option: User experiences of antipsychotic medication and lack of involvement in medication decisions in a UK community sample. Journal of Mental Health, 27(4), 322–328. doi:10.1080/09638237.2017.1370637

- Morrison, P., Meehan, T., & Stomski, N. J. (2015). Living with antipsychotic medication side‐effects: The experience of Australian mental health consumers. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 24(3), 253–261. doi:10.1111/inm.12110

- Murphy, A. L., Gardner, D. M., Kisely, S., Cooke, C., Kutcher, S. P., & Hughes, J. (2015). A qualitative study of antipsychotic medication experiences of youth. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(1), 61–69.

- Murray, R. M., Quattrone, D., Natesan, S., van Os, J., Nordentoft, M., Howes, O., … Taylor, D. (2016). Should psychiatrists be more cautious about the long-term prophylactic use of antipsychotics? British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(05), 361–365. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.116.182683

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). (2014). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: Prevention and management. NICE Clinical Guideline178. Retrieved from http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/evidence/cg178-psychosis-and-schizophrenia-in-adults-full-guideline3

- Phillips, L., & McCann, E. (2007). The subjective experiences of people who regularly receive depot neuroleptic medication in the community. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 14(6), 578–586. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01145.x

- Pyne, J. M., McSweeney, J., Kane, H. S., Harvey, S., Bragg, L., & Fischer, E. (2006). Agreement between patients with schizophrenia and providers on factors of antipsychotic medication adherence. Psychiatric Services, 57(8), 1170–1178. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.57.8.1170

- Rajkumar, A. P., Horsdal, H. T., Wimberley, T., Cohen, D., Mors, O., Borglum, A. D., & Gasse, C. (2017). Endogenous and antipsychotic-related risks for diabetes mellitus in young people with schizophrenia: A Danish Population-Based Cohort Study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(7), 686–694. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16040442

- Rhee, T. G., Mohamed, S., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2018). Antipsychotic prescriptions among adults with major depressive disorder in office-based outpatient settings: National trends from 2006 to 2015. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 79(2). doi:10.4088/JCP.17m11970

- Rogers, A., Day, J., Randall, F., & Bentall, R. P. (2003). Patients’ understanding and participation in a trial designed to improve the management of anti-psychotic medication. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38(12), 720–727. doi:10.1007/s00127-003-0693-5

- Rogers, A., Day, J. C., Williams, B., Randall, F., Wood, P., Healy, D., & Bentall, R. P. (1998). The meaning and management of neuroleptic medication: A study of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Social Science & Medicine, 47(9), 1313–1323. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00209-3

- Russo, R. (2018). Through the eyes of the observed: Re-directing research on psychiatric drugs. Talking Point Papers. Vol. 3. London: McPin Foundation. Retrieved from http://mcpin.org/wp-content/uploads/talking-point-paper-3-final.pdf

- Schauer, C., Everett, A., del Vecchio, P., & Anderson, L. (2007). Promoting the value and practice of shared decision-making in mental health care. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 31(1), 54–61.

- Slade, M. (2017). Implementing shared decision making in routine mental health care. World Psychiatry, 16(2), 146–153. doi:10.1002/wps.20412

- Sohler, N., Adams, B., Barnes, D., Cohen, G., Prins, S., & Schwartz, S. (2016). Weighing the evidence for harm from long-term treatment with antipsychotic medications: A systematic review. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(5), 477–485. doi:10.1037/ort0000106

- Stewart, D. C., Anthony, G. B., & Chesson, R. (2010). ‘It's not my job. I’m the patient not the doctor’: Patient perspectives on medicines management in the treatment of schizophrenia. Patient Education and Counseling, 78(2), 212–217. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.016

- Stovell, D., Morrison, A. P., Panayiotou, M., & Hutton, P. (2016). Shared treatment decision-making and empowerment-related outcomes in psychosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 209, 23–28. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.158931

- Svedberg, B., Backenroth-Ohsako, G., & Lützén, K. (2003). On the path to recovery: Patients’ experiences of treatment with long‐acting injections of antipsychotic medication. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 12(2), 110–118. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0979.2003.00277.x

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 45. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Thomas, N. (2015). What's really wrong with cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis? Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 323. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00323

- Timulak, L. (2009). Meta-analysis of qualitative studies: A tool for reviewing qualitative research findings in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 19(4–5), 591–600. doi:10.1080/10503300802477989

- Timulak, L. (2014). Qualitative meta-analysis. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative analysis (pp. 481–495). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Tranulis, C., Goff, D., Henderson, D. C., & Freudenreich, O. (2011). Becoming adherent to antipsychotics: A qualitative study of treatment-experienced schizophrenia patients. Psychiatric Services, 62(8), 888–892. doi:10.1176/ps.62.8.pss6208_0888

- Usher, K. (2001). Taking neuroleptic medications as the treatment for schizophrenia: A phenomenological study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 10(3), 145–155. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0979.2001.00205.x

- Usher, K., Park, T., & Foster, K. (2013). The experience of weight gain as a result of taking second‐generation antipsychotic medications: The mental health consumer perspective. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 20(9), 801–806. doi:10.1111/jpm.12019

- Vancampfort, D., Stubbs, B., Mitchell, A. J., De Hert, M., Wampers, M., Ward, P. B., … Correll, C. U. (2015). Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. World Psychiatry, 14(3), 339–347. doi:10.1002/wps.20252

- Vandyk, A. D., & Baker, C. (2012). Qualitative descriptive study exploring schizophrenia and the everyday effect of medication‐induced weight gain. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 21(4), 349–357. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00790.x

- Vedana, K. G. G., & Miasso, A. I. (2014). The meaning of pharmacological treatment for schizophrenic patients. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 22(4), 670–678. doi:10.1590/0104-1169.3427.2466

- Wunderink, L., Nieboer, R. M., Wiersma, D., Sytema, S., & Nienhuis, F. J. (2013). Recovery in remitted first-episode psychosis at 7 years of follow-up of an early dose reduction/discontinuation or maintenance treatment strategy: Long-term follow-up of a 2-year randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(9), 913–920. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.19

- Wykes, T., Evans, J., Paton, C., Barnes, T., Taylor, D., Bentall, R., … Vitoratou, S. (2017). What side effects are problematic for patients prescribed antipsychotic medication? The Maudsley Side Effects (MSE) measure for antipsychotic medication. Psychological Medicine, 47, 2369–2378. doi:10.1017/S0033291717000903

- Yeisen, R. A., Bjornestad, J., Joa, I., Johannessen, J. O., & Opjordsmoen, S. (2017). Experiences of antipsychotic use in patients with early psychosis: A two-year follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 299. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1425-9

- Zarea, K., Fereidooni-Moghadam, M., & Hakim, A. (2016). Adherence to medication regimen in patients with severe and chronic psychiatric disorders: A qualitative study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(11), 868–874. doi:10.1080/01612840.2016.1239147

- Zipursky, R. B., & Agid, O. (2015). Recovery, not progressive deterioration, should be the expectation in schizophrenia. World Psychiatry, 14(1), 94–96. doi:10.1002/wps.20194