Abstract

Background

Suicide prevention gatekeeper Training (GKT) is a frequently used suicide prevention intervention, however, there is still limited information about its long-term impact and effectiveness of online delivery.

Aims

The current study aimed to test the effectiveness of online GKT compared to in-person GKT in improving participant training outcomes.

Methods

A non-randomised comparison of pre-, post- and six-month follow-up data was conducted. In total 545 people participated in GKT, 317 in SafeTALK in-person sessions and 228 in online “Start” GKT by LivingWorks. Main outcome measures included: perceived knowledge; perceived preparedness; gatekeeper efficacy; and gatekeeper reluctance to intervene.

Results

Linear mixed model analysis demonstrated a significant effect for time for both modes of delivery for all four outcome measures. Post-hoc testing revealed that significant improvement in all outcomes were maintained above baseline at six-months following online and in-person training.

Conclusions

Online training performed as good, or better than in-person GKT, on measured outcomes demonstrating utility and effectiveness of the modality for use in suicide prevention training practices. Findings additionally indicate that online training may reach participants that in-person programs do not. This study provides evidence that Online GKT has significant utility in addressing a crucial need for online alternatives to evidence-based suicide prevention training.

Introduction

Suicide prevention training interventions, also called Gatekeeper Training (GKT), have utility in addressing the issue of suicide by increasing readily available support (Mann et al., Citation2005). GKT programs are designed to teach the lay public basic skills in recognising and responding to individuals at risk of mental health distress and potential suicide (Burnette et al., Citation2015). General public education is important, as evidence suggests that many people in crisis do not seek assistance from formal mental health services (Corrigan, Citation2004; Pitman & Osborn, Citation2011). The presence of trained and alert individuals in the general community offers the opportunity to identify and support at-risk individuals who may otherwise not seek assistance. To date, most GKT programs have been delivered to trainees in-person.

Online training has previously been established as a viable option to help meet suicide prevention training needs as it employs flexible, easy-to-use, and relatively inexpensive internet technology (Hill et al., Citation2023; Stone et al., Citation2005). Additional benefits include decreased training costs, improved administration flexibility, and increases in the learner’s control regarding the training process (Long et al., Citation2008). A small number of GKT programs have previously offered an online option (e.g. QPR; Quinnett, Citation2007), and previous studies support the feasibility of implementing and delivering online GKT programs (Ghoncheh et al., Citation2016; Lamis et al., Citation2017; Lancaster et al., Citation2014). Web-based training in the form of e-learning modules has demonstrated improved outcomes are maintained at three-months follow-up compared to baseline scores (Ghoncheh et al., Citation2016); however, no in-person data were collected in this study to allow modal comparison. Lancaster et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated that web-based training may be as effective as in-person training in the short term. Long-term outcomes in both groups declined from post-test to six-months (Lancaster et al., Citation2014); however this decline was generally consistent with other similar longitudinal GKT studies (Holmes et al., Citation2021b). Recent research has continued to highlight the need for increased reach and uptake of GKT by offering digital versions (Torok et al., Citation2019). Understanding the differences in learning outcomes between online and in-person training is important to better understand the respective efficacy of the two modalities.

SafeTALK is a suicide prevention training program designed to train GKs to recognise and respond to the signs of suicidality (Turley, Citation2018). The program is approximately 4-h in duration and is delivered in-person. SafeTALK has been shown to improve longitudinal GK outcomes in school environments (Bailey et al., Citation2017) and the general population (Holmes et al., Citation2021a). The developers of SafeTALK (LivingWorks) recently released an online GKT alternative called “Start.” Start is a 1.5-h GKT undertaken entirely online. The content covered in each of these GKT packages reflects largely the same underlying framework; however, differences in the duration of training limit the detail available in the online training. Regardless, these two GKT programs provide an ideal opportunity to evaluate the effect of delivery modality (online or in-person) on the efficacy of GKT. To the author’s knowledge no peer-reviewed evaluations of Start online GKT have yet been conducted.

This research aimed to test the effectiveness of online GKT compared to in-person GKT in improving suicide prevention outcomes. Specifically, this study aimed to explicate if online GKT would produce equivalent six-month follow-up outcomes when compared with in-person GKT on the outcomes of knowledge, preparedness, efficacy, and reluctance to intervene.

Material and methods

Participants

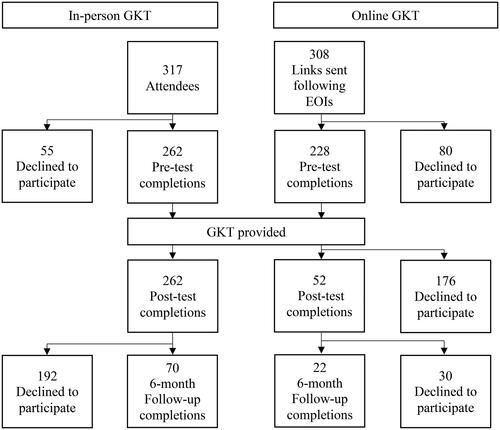

A total of 545 community members voluntarily participated across both training modalities offered in the study. Three hundred and seventeen (317) individuals participated in one of 12 in-person GKT sessions and 228 participated in online GKT (). Of the 317 in-person attendees, 262 consented to participate in research, completing pre- and post-training surveys in-person. All 228 online trainees participated in online training by completing the pre-training questionnaire and training session. For all training programs, informed consent was sought prior to beginning the pre-test survey. Ethics approval was provided by the University of the Sunshine Coast Human Research Ethics Board (S181250).

Materials

Interventions

The SafeTALK 4-h training program GKT program of LivingWorks was selected as the in-person intervention SafeTALK. Turley (Citation2018) provides a succinct review of the evidence and rationale for SafeTALK. The online GKT program, LivingWorks “Start,” is a 1.5-h online suicide prevention training course developed by LivingWorks. This program was developed from the same foundational base of evidence as SafeTALK, and included input from experts in suicide prevention, education, psychology, public health, and social work.

Measures

Demographic details collected included participant gender, age, and prior Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) training or previous suicide prevention training. Survey items were selected from previously used measures (Wyman et al., Citation2008), with amendments made to reflect provision to a general community population. The four scales assessed were: (i) perceived knowledge (7 items); (ii) perceived preparedness (5 items); (iii) GK efficacy (6 items), and (iv) GK reluctance to intervene (6 items). All scales were assessed on a seven-point Likert scale. Reliability at pre-, post- and follow-up as tested by Cronbach’s α measure of internal consistency, was excellent for knowledge (.96, .93, .94) and preparedness (.95, .92, .93), acceptable for efficacy (.77, .74, .81), and marginal for reluctance (.50, .53, .71).

Design

A non-randomised comparison of pre-post and follow-up was the design chosen for this study. Research design was a balance of funding, time, and methodological rigour. Though RCT’s are desirable (and lacking in this area of research) this project could not accommodate the resources required. Recruitment for both interventions occurred separately via e-newsletter distribution and a social media marketing campaign targeting all Sunshine Coast, Queensland residents. SafeTALK GKT was conducted from February 2019 until November 2019; Start GKT occurred during May and June 2020. SafeTALK attendees were provided with a research project information sheet and copy of the survey upon arrival at the training location. Ten minutes survey completion time was provided prior to commencing the training to allow participants time to complete the pre-test survey. This was followed by the delivery of the in-person GKT program. Consistency of in-person training was maintained with the use of the same GKT facilitator and location across all 12 workshops. Following training completion, SafeTALK participants were invited to complete the post-test evaluation prior to departing the training location. Start online training access (via link) was provided to participants upon completion of the pre-test survey, access to the post-test survey was provided within seven days of training completion.

Six months after their training session, participants were emailed a link to complete a follow-up survey. The follow-up survey was provided via an online link available for completion on computer or mobile platforms. Responses were case matched to pre- and post-test responses via emails linked to participant codes. No incentives were offered for participation, though the training was offered without cost to participants. Throughout all SafeTALK training sessions there was a support person present and available for attendees to speak with if they experienced any stress or distress as a result of the presented content. Online and phone resources and contacts were available throughout the online training for participants to access support should they experience distress during the training.

Data analysis

All hard-copy data from in-person workshops were de-identified during digital input. Follow-up responses were case matched via email addresses linked to participant codes generated from participant names. Reverse scored items were re-calculated and mean scores for each scale were determined. Although Shapiro-Wilk statistics indicated the assumption of normality was violated for a number of outcomes, analyses of skewness and kurtosis statistics indicated the scales had acceptable distribution (range −1.5 to +1.5; Tabachnick et al., Citation2007).

A linear mixed effects model was conducted to evaluate the impact of the mode of delivery on training outcomes over time. The model is similar in many ways to multiple regression, but it requires additional work to specify models and to assess goodness-of-fit (Cnaan et al., Citation1997). The extra complexity involved is compensated for by the additional flexibility it provides in model fitting. making it is well suited to measuring changes in repeated measures over time (Walker et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, unlike Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and its sub-variations, linear mixed effects models are capable of handling uneven temporal variation between data collection points (Krueger & Tian, Citation2004) and are effective at managing missing data that can occur through attrition (Detry & Ma, Citation2016). As such, linear mixed effects model is the most suitable statistical analysis technique in this case.

Gender, age, prior MHFA training, and previous suicide prevention training were entered as covariates. The inclusion of these demographic covariates improved the model fit on all outcomes. Post-hoc testing was conducted to determine the presence of significant differences between the mode of delivery on training outcomes measured at each time point, and to determine significance of change between time points by mode. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.

Results

Two hundred and sixty-two in-person participants completed pre-test, 251 completed post-test, and 70 participants completed six-month follow-up surveys, representing an attrition rate of 73.7%. Of the 228 online Start participants who completed pre-test, 54 participants completed the post-test, and 22 completed the follow-up, representing an attrition rate of 90.3%. Participation rates for each scale by training mode and data collection point are presented in .

Table 1. Responses for each variable split by training mode and data collection point.

No significant demographic differences were identified between modal (i.e. in-person compared to online delivery) groups. There were also no significant differences between participants who completed follow-up evaluations and those who did not, for age, gender, or prior MHFA training. However, there were significant between-group differences for follow-up compared with no follow-up for prior suicide prevention training; those with prior suicide prevention training were over-represented in the online follow-up sample. Participant demographics are presented in .

Table 2. Participant demographics and prior training.

Knowledge

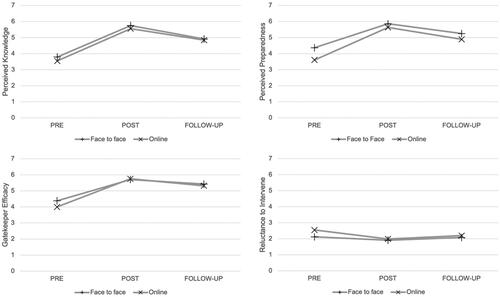

Linear mixed model analysis demonstrated a significant effect for time for both modes of delivery. No significant main effect for mode was present in knowledge, nor was there an interaction effect for mode*time (). Post-hoc analysis revealed a significant modal difference in mean scores at pre-test with in-person participants reporting higher perceived knowledge (F(1,504.07) = 3.94, p = .048) but not post-test nor at six-month follow-up (F(1,307,86) = 2.50, p = .115; F(1,114.57) = 0.08, p = .774). Both modes recorded significant increases from pre- to post-test, significant decreases from post-test to follow-up, and a significant overall increase from pre-test to follow-up (, ).

Figure 2. Longitudinal comparison of online and in-person on tested outcomes. Error bars are too small to display (SE data range.042–.218).

Table 3. Main effects for Time and Mode, and interaction effects for Mode*Time on GKT outcomes.Table Footnotea

Table 4. Post-hoc testing results for mean differences over time by mode of delivery.

Preparedness

A significant main effect of time was observed for both modes of delivery. A significant main effect for mode was present in the outcome of preparedness, and a significant interaction effect was present for mode*time (). Post-hoc analysis showed a significant difference in group means at pre-test (F(1,496.64) = 34.98, p < .001) and post-test, with in-person participants reporting higher preparedness (F(1,325.33) = 3.99, p = .047), but not follow-up (F(1,110.61) = 1.99, p = .161). Both modes recorded significant increases from pre- to post-test, significant decreases from post-test to follow-up, and a significant overall increase from pre-test to follow-up (, ).

Efficacy

Efficacy demonstrated a significant main effect for time for both modal groups; however, no significant main effect for mode was present. There was a significant interaction effect for mode*time (). Post-hoc testing showed a significant difference in means at pre-test, with in-person participants reporting higher efficacy (F(1,509.31) = 14.81, p < .001), but not at post-test or follow-up (F(1,335.93) = 0.16, p = .686; F(1,123.48) = 0.38, p = .538). Both modes recorded significant increases from pre- to post-test, significant decreases from post-test to follow-up, and a significant overall increase from pre-test to follow-up (, ).

Reluctance to intervene

Significant main effects for time and mode were present for the outcome of reluctance, as well a significant interaction effect for mode*time. Post-hoc testing showed a significant mean difference at pre-test with in-person participants reporting lower reluctance (F(1,458.28) = 46.13, p < .001), but not post-test or follow-up (F(1,324.67) = .78, p = .378; F(1,91.24) = .65, p = .422). Both modes recorded significant decreases (less reluctance to intervene) from pre- to post-test; however, only SafeTALK recorded a significant increase between post-test and follow-up resulting in no significant difference between pre-test and follow-up. Start showed no significant change from post-test to follow-up, with a significant difference retained between pre-test and follow-up (, ).

Discussion

We sought to identify whether online GKT would produce equivalent learning outcomes for knowledge, preparedness, efficacy, and reluctance to intervene at six-month follow-up compared to in-person GKT. A significant main effect for time was present in all outcomes for online training. Post-hoc testing revealed significant improvement in all outcomes were maintained at six months, despite some decline from post-test to the six-month follow-up. Online GKT was shown to be effective as a suicide prevention training tool in improving knowledge, preparedness, efficacy, and reluctance to intervene. In comparison to in-person GKT, findings demonstrated online GKT is as effective on the outcomes tested. Our results corroborate previous research comparing modes of delivering another GKT (Question, Persuade, and Refer), finding online as effective as in-person training (Lancaster et al., Citation2014). The use of online learning environments is increasing, so it is crucial to understand the impact of transitioning training to this attractive mode of delivery.

Key findings & implications

A key contribution of this study is that online training produced and maintained a significant overall reduction in reluctance to intervene in trainees, outperforming in-person training on this outcome. The reasons for this reported maintenance of training (in the absence of in-person effectiveness) appear to be due to the initially higher reluctance recorded in online participants at baseline. A previous study has highlighted the effectiveness of GKT in decreasing stigma, a primary driver of reluctance to intervene, by focusing on increasing help-seeking behaviours and raising awareness of effective mental health treatment (Bean & Baber, Citation2011). However, a recent review of longitudinal GKT programs noted the lack of strong evidence for training to impact long-term attitudes towards suicide (Holmes et al., Citation2021b). The findings of this study are promising but require replication before firm conclusions supporting the relative benefits of online training in the domain of reluctance to intervene can be established.

The time difference between online (1.5 h) and in-person (4 h) training appears not to have impacted training effectiveness. Prior research comparing two-day (ASIST) with 2 h GKT (QPR or RESPONSE) found similar results, with all three programs performing equally (Coleman & Del Quest, Citation2015). Trainees participating in longer training (ASIST) were noted to have higher scores at pre-test, potentially resulting in a ceiling effect (Coleman & Del Quest, Citation2015). This phenomenon was also observed in the present study. Nonetheless, it has been demonstrated that brief GKT training can also show significant effects, perhaps suggesting that extended or more intensive training may not be necessarily be required to influence outcomes (Coleman & Del Quest, Citation2015).

An important finding of the present study is that online training can reach individuals who may otherwise not participate in GKT. Post-hoc analyses revealed online participants, compared with in-person participants, recorded significantly lower means for knowledge, preparedness, and GK efficacy, and higher for reluctance to intervene at baseline, with this difference not significant at follow-up. These findings indicate that initially, participants choosing to take part in online training are less knowledgeable, less prepared, and feel less efficacy and more reluctance to perform the GK role. Therefore, online training programs may have additional reach to engage individuals with less previous exposure to suicide prevention information or training opportunities. The reduced time and resources required to participate online (compared to in-person) potentially attract participants who are “time poor,” who cannot attend the scheduled workshop times, or who feel hesitant to put themselves into a formal training environment.

It has previously been reported that GKs with limited time and resources can benefit from the accessibility, simplicity, and flexibility of online training (Ghoncheh et al., Citation2016). In the context of in-person GKT, some trainees may be hesitant to participate or fully engage in the training because of the sensitivity associated with the issue of suicide (Lancaster et al., Citation2014). The anonymity afforded by online training may allow for acceptable social interaction if the trainee lacks self-efficacy (Kraiger, Citation2015). Online GKT has the potential to reach a wider population of participants, and they appear to have less confidence in their abilities upon entering training. Study findings indicate that online GKT may benefit a wide range of lay GKs due to the increased access for those that may otherwise not participate (in in-person workshops). This information poses an interesting question around what these individuals may do with their training, what will be their likelihood of intervention behaviour given the apparent reluctance to engage in-person with the content? Perhaps these individuals may apply the training within themselves to some degree, or perhaps in the changing world of online communication these individuals may be the new vanguard of electronic communication intervention.

Regardless, it is apparent that online GKT reduces the difference in abilities and produces long-term positive training outcomes. Online training may be utilised as a key part of a wider suicide prevention strategy, whether as a booster training session, to supply training to regional or remote locations, or to build an online community of GKs. These findings support the use of online GKT to complement specific and wider suicide prevention initiatives.

Limitations

Some limitations require discussion. Firstly, the sampling was non-random and delivery groups were not randomised; this study could be improved by using random sampling. Secondly, the data collection periods were not aligned. Thirdly, there was no control group; as such it is not possible to determine that the significant effect for time was due to the interventions. Fourthly, the instruments used in this study were adapted for this purpose and have not yet been validated. Fifth, there was a rather high attrition at the follow-up particularly for online GKT follow-up. Furthermore, although acceptable at follow-up, the reliability coefficient for the reluctance scale at pre-test and post-test was poor. However, Cronbach’s α variation is not uncommon in repeated measures designs as a result of response shift phenomena. Response shift refers to a change in one’s self-evaluation of the target construct (e.g. knowledge about suicide, or reluctance to engage with at-risk-individuals) as a result of (1) a change in the respondent’s internal standards of measurement (i.e. recalibration), (2) a change in the respondent’s values (i.e. reprioritisation), or (3) a redefinition of the construct by the respondent (i.e. reconceptualisation; Schwartz et al., Citation2007). Regardless of the specific underlying mechanism, lower α’s are consistent with the literature (Hawgood et al., Citation2020; Lancaster et al., Citation2014; Wyman et al., Citation2008). Finally, dropout in both groups was high; however attrition rates of this nature are not uncommon in GKT evaluation literature (Hawgood et al., Citation2021).

Conclusion

In conclusion, and in consideration of the abovementioned limitations, the results of this study indicate that online training is an effective suicide prevention GKT tool. Compared with in-person training, online training performed as good, or better, on outcomes of knowledge, preparedness, efficacy, and reluctance to intervene. Findings indicate that online training may reach participants that in-person programs may not. Research directions stemming from this important research should be focused on the behavioural outcomes of suicide prevention (identification, intervention, & referral) as well as the impacts of GKT on additional outcome measures, such as attitude(s) towards suicide. Such research would build well upon the present findings showing online GKT has significant utility in addressing a crucial need for online alternatives to evidence-based suicide prevention training.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was granted by the University of the Sunshine Coast Human Research Ethics Committee (S181250).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bailey, E., Spittal, M. J., Pirkis, J., Gould, M., & Robinson, J. (2017). Universal suicide prevention in young people. Crisis, 38(5), 300–308. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000465

- Bean, G., & Baber, K. M. (2011). Connect: An effective community-based youth suicide prevention program. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 41(1), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00006.x

- Burnette, C., Ramchand, R., & Ayer, L. (2015). Gatekeeper training for suicide prevention: A theoretical model and review of the empirical literature. Rand Health Quarterly, 5(1), 16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28083369

- Cnaan, A., Laird, N. M., & Slasor, P. (1997). Using the general linear mixed model to analyse unbalanced repeated measures and longitudinal data. Statistics in Medicine, 16(20), 2349–2380. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19971030)16:20<2349::AID-SIM667>3.0.CO;2-E

- Coleman, D., & Del Quest, A. (2015). Science from evaluation: Testing hypotheses about differential effects of three youth-focused suicide prevention trainings. Social Work in Public Health, 30(2), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2014.938397

- Corrigan, P. (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. The American Psychologist, 59(7), 614–625. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614

- Detry, M. A., & Ma, Y. (2016). Analyzing repeated measurements using mixed models. JAMA, 315(4), 407–408. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.19394

- Ghoncheh, R., Gould, M. S., Twisk, J. W., Kerkhof, A. J., & Koot, H. M. (2016). Efficacy of adolescent suicide prevention e-learning modules for gatekeepers: A randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health, 3(1), e8. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.4614

- Hawgood, J., Koo, Y. W., Sveticic, J., De Leo, D., & Kõlves, K. (2020). Wesley LifeForce suicide prevention gatekeeper training in Australia: 6 Month follow-up evaluation of full and half day community programs. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11(1572), 614191. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.614191

- Hawgood, J., Woodward, A., Quinnett, P., & De Leo, D. (2021). Gatekeeper training and minimum standards of competency: Essentials for the suicide prevention workforce. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 43(6), 516–522. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000794

- Hill, R. M., Picou, P., Hussain, Z., Vieyra, B. A., & Perkins, K. M. (2023). Randomized controlled trial of an online suicide prevention gatekeeper training program: Impacts on college student knowledge, gatekeeper skills, and suicide stigma. Crisis, 45(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000917

- Holmes, G., Clacy, A., Hermens, D. F., & Lagopoulos, J. (2021a). Evaluating the longitudinal efficacy of SafeTALK suicide prevention gatekeeper training in a general community sample. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 51(5), 844–853. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12741

- Holmes, G., Clacy, A., Hermens, D. F., & Lagopoulos, J. (2021b). The long-term efficacy of suicide prevention gatekeeper training: A systematic review. Archives of Suicide Research, 25(2), 177–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1690608

- Kraiger, K. (2015). Transforming our models of learning and development: Web-based instruction as enabler of third-generation instruction. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(4), 454–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2008.00086.x

- Krueger, C., & Tian, L. (2004). A comparison of the general linear mixed model and repeated measures ANOVA using a dataset with multiple missing data points. Biological Research for Nursing, 6(2), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1099800404267682

- Lamis, D. A., Underwood, M., & D’Amore, N. (2017). Outcomes of a suicide prevention gatekeeper training program among school personnel. Crisis, 38(2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000414

- Lancaster, P. G., Moore, J. T., Putter, S. E., Chen, P. Y., Cigularov, K. P., Baker, A., & Quinnett, P. (2014). Feasibility of a web-based gatekeeper training: Implications for suicide prevention. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(5), 510–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12086

- Long, L. K., DuBois, C. Z., & Faley, R. H. (2008). Online training: The value of capturing trainee reactions. Journal of Workplace Learning, 20(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620810843629

- Mann, J. J., Apter, A., Bertolote, J., Beautrais, A., Currier, D., Haas, A., Hegerl, U., Lonnqvist, J., Malone, K., Marusic, A., Mehlum, L., Patton, G., Phillips, M., Rutz, W., Rihmer, Z., Schmidtke, A., Shaffer, D., Silverman, M., Takahashi, Y., … Hendin, H. (2005). Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. JAMA, 294(16), 2064–2074. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.16.2064

- Pitman, A., & Osborn, D. P. (2011). Cross-cultural attitudes to help-seeking among individuals who are suicidal: New perspective for policy-makers. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 199(1), 8–10. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.087817

- Quinnett, P. (2007). QPR gatekeeper training for suicide prevention the model, rationale and theory (pp. 1–38). QPR Institute.

- Schwartz, C. E., Andresen, E. M., Nosek, M. A., & Krahn, G. L. (2007). Response shift theory: Important implications for measuring quality of life in people with disability. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(4), 529–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.032

- Stone, D. M., Barber, C. W., & Potter, L. (2005). Public health training online: The National Center for Suicide Prevention Training. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 29(5 Suppl 2), 247–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.019

- Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., & Ullman, J. B. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (Vol. 5). Pearson Boston.

- Torok, M., Calear, A. L., Smart, A., Nicolopoulos, A., & Wong, Q. (2019). Preventing adolescent suicide: A systematic review of the effectiveness and change mechanisms of suicide prevention gatekeeping training programs for teachers and parents. Journal of Adolescence, 73(1), 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.04.005

- Turley, B. (2018). SafeTALK literature review: An overview of its rationale, conceptual framework, and research foundations. https://legacy.livingworks.net/resources/research-and-evaluation/

- Walker, E. A., Redfern, A., & Oleson, J. J. (2019). Linear mixed-model analysis to examine longitudinal trajectories in vocabulary depth and breadth in children who are hard of hearing. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 62(3), 525–542. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_jslhr-l-astm-18-0250

- Wyman, P. A., Brown, C. H., Inman, J., Cross, W., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Guo, J., & Pena, J. B. (2008). Randomized trial of a gatekeeper program for suicide prevention: 1-year impact on secondary school staff. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.104