Abstract

Background: The Amputee Body Image Scale (ABIS) and its shortened version (ABIS-R) are self-administered questionnaires to measure body image perception of amputee. Our aim was to assess the validity and reliability of the French ABIS (ABIS-F and ABIS-R-F).

Methods: Ninety-nine patients were included. The cross-cultural adaptation was performed according to the recommendations. Construct validity was assessed by measuring the correlation between ABIS-F or ABIS-R-F scores and quality of life, pain, anxiety, and depression. Internal consistency was measured with Cronbach’s α. The standard error of measurement, smallest detectable change, Bland and Altman limits of agreement, and intraclass correlation were the measures of agreement and reliability.

Results: A highest body image disturbance was associated with lowest quality of life, higher pain, and higher anxiety, and depression. Cronbach’s α was 0.91/0.89 (ABIS-F/ABIS-R-F). The standard error of measurement was 5.35/2.28 (ABIS-F/ABIS-R-F). The smallest detectable change was 14.82/6.31 (ABIS-F/ABIS-R-F). The mean difference in ABIS-F score was −3.90 with limits of agreement from −18.71 to 10.92. For ABIS-R-F, the mean difference was −2.12 with limits of agreement from −8.43 to 4.19. Intraclass correlation was 0.87/0.82 (ABIS-F/ABIS-R-F).

Conclusions: The French versions ABIS-F and ABIS-R-F share similar psychometric properties, both are as reliable, but ABIS-R-F has a better response structure and is more feasible.

The quality of life of amputees is impacted by their satisfaction with body image

The Amputee Body Image Scale questionnaire measures this perception and is available for French-speaking amputees

The Standard Errors of Measurement proposed could be useful for clinical and research purposes

Both ABIS and ABIS-R showed satisfactory construct validity, internal consistency, and reliability

The shortened version has a better response structure and is more readily feasible.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Amputation is a devastating event for most people. It involves the irreversible loss of physical integrity and changes in terms of body image and function. When it occurs, the patient does not know what his life will be like in the future. He is confronted to multiple adjustments in his professional life, in social activities, and in leisure. Some patients encounter problems in adapting, which include depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, social isolation [Citation1–4].

The amputee has to integrate at least three different body images: his complete body (before the limb loss), his amputated body, and his body with the prosthesis [Citation5]. Being amputated may provoke a feeling of shame for being incomplete, and/or a feeling of inferiority, which also makes social relationships more difficult. Few studies look at the relationship between body image and well-being in amputees. Body image refers to the perception we have of our body and its appearance. It is a complex set of representations including the way we perceive it, the way we are satisfied with it, and the way we judge it is attractive. It is affected by social values (we know for example, that beautiful people are more likely to be evaluated as competent and positive [Citation6]) and gender (female are more sensible of esthetic, men of size and strength [Citation7,Citation8]).

Low or bad body image satisfaction has been found to be related to depression, poorer quality of life, lower self-esteem, higher levels of anxiety, sexual functioning, and lower satisfaction with prosthesis [Citation3–5,Citation9–11]. More recently, Holzer et al. [Citation12] showed a decreased level of body image and quality of life, but not of self-esteem values in persons with a lower-limb amputation.

Satisfaction with body image also correlate with satisfaction with the prosthesis and its use. Wetterhahn et al. [Citation13] found a positive relationship between physical activity level and body image. Murray and Fox [Citation7] showed that for men higher level of functional satisfaction with the prosthesis was linked to lower level of body image disturbance. For female patients, satisfaction with the prosthesis seems to include esthetic and functional aspects. Moreover, Murray et al. [Citation14–16] pointed out the social and personal meanings of prosthesis use in restoring a “normal” appearance and life.

The Amputee Body Image Scale (ABIS) and its shortened version (ABIS-R) are self-administered questionnaires created to measure specifically body image perception of amputees, from the patient’s perspective. These questionnaires are only available in English [Citation4,Citation17], Turkish [Citation18] and Chinese [Citation19]. The ABIS questionnaire, developed by Breakey in 1997 [Citation4], comprises 20 items to assess how a patient with an amputation perceives and feels about his body experience. The response to each item is rated on a 1 to 5 Likert scale (from “Never” to “All the time”). The total score is obtained by summing all items, thus resulting in a value between 20 and 100. The shortened version of the questionnaire (ABIS-R) was described by Gallagher in 2007 [Citation17] and has been validated with 6 fewer items (14 items, items 2, 7, 11, 16, 17, and 19 were removed), rated on a 0 to 2 scale (“Never”, “Hardly ever or Sometimes”, “Most of the time or All the time“), with a total score ranging between 0 and 28. For both ABIS and ABIS-R, a low score indicates relative body image concern, a high score indicates the presence of a more serious body image disturbance perception. There is no cutoff.

The aim of this study was to assess the validity and reliability of the French ABIS (ABIS-F) and its shortened version (ABIS-R-F).

Methods

This study took place in three centers in Switzerland (two university orthopedics centers: Geneva, and Lausanne, and one rehabilitation center in Sion, also including patients from the Cantonal Hospital (Sion)), and in one center of rehabilitation in France (Nancy). Ninety-nine patients were included: inclusion criteria were: persons with a lower-limb amputation for more than 1 year, living at home, in the reference list of these four medical centers. Not French speaking patients were excluded. Our study was approved by the ethical committee of the canton Valais (CCVEM 043/11). Permission was granted to use and translate the ABIS developed by James Breakey. Eligible patients first received an information letter and were asked to give a written informed consent.

Cross-cultural adaptation

The cross-cultural adaptation of ABIS-F and ABIS-R-F was performed according to the recommendations of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) outcomes committee [Citation20], and as recommended by others in the literature [Citation21,Citation22]. The following five steps were documented in a written report: forward translation from English to French by two translators whose native language was French and fluent in English (T1 and T2). None of the translators were physicians. One of the translators was informed about the aims of the study and the other received only limited information (so-called naïve translator). Synthesis of T1 and T2 was done to form a unique translated version T12 by resolving any discrepancies under supervision of a methodologist not involved in the translation process. Back translation of the T12 version from French to English was by two English native speakers who were fluent in French (BT1 and BT2). These two translators were naïve to the study and not linked to the medical domain. Consensus meeting with all the involved subjects (translators, methodologist, specialist physicians in rehabilitation) in order to resolve any discrepancies and doubts met during the translation to establish the pre final French version of the ABIS-F and ABIS-R-F. This pre final version was administered to French native speaking people with a lower-limb amputation. They were asked to write commentaries on difficulties of the questionnaire, especially comprehension. The definitive versions of French ABIS and ABIS-R were validated during a new consensus meeting.

Validation

The definitive version of the ABIS-F questionnaire was administered to 99 patients, who also completed validated French versions of the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) [Citation23–25], the Brief Pain Inventory [Citation26,Citation27], the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [Citation28,Citation29], and some items of the Prosthetic Profile of the Amputee [Citation30]. The SF-36 is a self-questionnaire measuring quality of life. It consists of one multi-item scale that assesses physical component (SF-36-PCS) and mental component (SF-36-MCS) (both range 0–100). The lower the score, the higher the disability. A score of 100 is equivalent to no disability. The Brief Pain Inventory assesses the severity of pain and its impact on functioning. It is widely used in both research and clinical settings. We used different subscales of the Brief Pain Inventory: pain severity score, and pain interference measures that included seven items which assess pain disability in general activities: pain interference in general activities, work outside the home, homework, walking, sleep, relations with other people, enjoyment of life. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is a commonly used scale to determine the levels of anxiety and depression a patient is experiencing. It is a fourteen items scale, with seven items relating to anxiety and seven items focusing on depression, rating from 0 to 3 with a maximal total score of 21 points. The Prosthetic Profile of the Amputee is a questionnaire that measures the factors potentially related to prosthetic use and the actual use of the prosthesis by people with a lower extremity amputation. We used several items of this questionnaire (dichotomized as a yes or no answer): suffering from phantom pain, trouble with putting the prosthesis, wearing the prosthesis all the time, already fallen with the prosthesis, needing technical help (crutches) to walk with the prosthesis, relatives’ acceptation of the amputation and the prosthesis.

Construct validity was assessed by measuring the Pearson correlation coefficient between ABIS-F or ABIS-R-F scores and the SF-36 (SF-36-PCS and SF-36-MCS), subscales of the Brief Pain Inventory (pain severity and pain interference), Anxiety and Depression. Our hypotheses were that we would observe positive correlations between ABIS-F/ABIS-R-F and pain severity, pain interference, anxiety, and depression. We expected negative correlations between ABIS-F/ABIS-R-F and SF-36 subscales (SF-36-PCS and SF-36-MCS). A correlation is considered excellent if r > 0.91, good if r between 0.71 and 0.90, medium if r between 0.51 and 0.70, and poor if r between 0.31 and 0.50. A correlation <0.30 is not considered as significant [Citation31]. We also measured the associations between the aforementioned items of the Prosthetic Profile of the Amputee and ABIS-F or ABIS-R-F scores by means of t-tests. We expected ABIS-F/ABIS-R-F scores to be higher in patients who suffer from phantom pain, who have trouble with putting the prosthesis, who do not wear the prosthesis all the time, who have already fallen with the prosthesis, who need technical help to walk, and patients whose relatives do not completely accept their amputation and prosthesis. Construct validity is considered acceptable if at least 75% of the results are in correspondence with our hypotheses [Citation32].

Internal consistency was measured with Cronbach’s α, which indicates the homogeneity between items. Values for α can range from 0 (no internal consistency) to 1 (perfect internal consistency). A value above 0.8 is considered acceptable [Citation31].

A principal-component analysis was performed to test the unidimensionality of the measure. When the first component accounts for 40% of the total variance, or when the first eigenvalue is sufficiently larger than the other ones, it can be assumed that the set of items is measuring a single dimension [Citation33].

A Rasch rating-scale model was performed on the 20 items of ABIS-F, as well as on the 14 items of ABIS-R-F, to investigate whether the rating scales were being used in the expected manner, following suggested criteria [Citation34]. The validity of the model was also analyzed by examining the pattern of item difficulties, infit and outfit statistics. These results were compared to those obtained in the English version [Citation17] to assess the cross-cultural validity of the questionnaire.

A sample of 24 patients completed the ABIS-F twice within a few days (5–7 days) to allow for reproducibility evaluation. Both agreement and reliability were assessed.

Agreement concerns the absolute difference between repeated measures. A high agreement is required to distinguish clinically important changes from measurement error. The standard error of measurement (SEM) was used to express agreement. It equals the square root of the error variance of an ANOVA analysis, including systematic differences [Citation32]. The standard error of measurement can be converted into the smallest detectable change (SDCind) as SDCind=1.96×√2 × SEM. SDCind is the smallest change that can be interpreted as a “real” change, in one individual. The smallest detectable change measurable in a group of n people (SDCgroup) is obtained as SDCgroup = SDCind/√n. The limits of agreement (LoA) described by Bland and Altman [Citation35] were also reported. The limits of agreement equal the mean change in scores of repeated measurements ±1.96 × standard deviation of these changes.

Reliability is important for discriminative purposes if one wants to distinguish among patients, despite measurement error. The intraclass correlation (ICC) was used as the reliability parameter. It was computed with a two-way random-effects model (ICC(2,1) according to Shrout and Fleiss [Citation36] or ICC(A,1) according to McGraw and Wong [Citation37]) as systematic differences are considered to be part of the measurement error.

The proportion of patients achieving the lowest or highest possible score was computed in order to detect any floor or ceiling effects. Ceiling and floor effects were defined as present if at least 15% of results reached the maximum or the minimum value [Citation38].

Normal based confidence intervals (CI) were computed using 500 bootstrap replications; the confidence level was set at 95%. All statistical analyses were performed on complete-case data using Stata 15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), except the Rasch models that were computed with Winsteps 4.0.1 (Winsteps® Rasch measurement computer program. Beaverton, Oregon).

Results

shows characteristics of the patients and the average scores in the different questionnaires. ABIS-F and ABIS-R-F were strongly associated, with a correlation of 0.97 (95% CI [0.95; 0.98]).

Table 1. Characteristics of the patients and summary measures of the questionnaires.

Cross cultural adaptation

The French translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the ABIS and ABIS-R was made according to the usual guidelines [Citation20]. No important difficulties were encountered during the translation process. Pre-test ABIS-F version was tested in a sample of patients with lower limb amputation. The questionnaire was well accepted by patients.

Validation study

The correlations between ABIS-F or ABIS-R-F and the different questionnaires are given in . As expected, a highest body image disturbance was associated with lowest quality of life, higher pain severity and interference, and higher anxiety and depression. We notice that these correlations were similar with ABIS-F and with ABIS-R-F.

Table 2. Correlations (95% Confidence Intervals) between the different questionnaires and ABIS-F and ABIS-R-F.

Associations between ABIS-F or ABIS-R-F and items of the Prosthetic Profile of the Amputee are given in . Patients who suffer from phantom pain and those who have trouble with putting their prosthesis have a poorer body image. There was no clear association between body image and needing of technical help (crutches) to walk with the prosthesis. Patients whose relatives completely accept their amputation and their prosthesis have a better body image. Wearing the prosthesis or not, and previous falls were not associated with body image. Thus, 9 out of 12 hypotheses were satisfied, which corresponds to the recommended 75% [Citation32].

Table 3. Associations between ABIS-F or ABIS-R-F and items of the prosthetic profile of the amputee.

Cronbach’s α was 0.91 (bootstrap 95% CI [0.88; 0.94]) for ABIS-F and 0.89 [0.87; 0.92] for ABIS-R-F, which illustrates a good internal consistency for both scores. A coefficient between 0.70 and 0.95 is expected for a satisfying consistency [Citation32]. A very high value (between 0.95 and 1) would indicate redundancy of one or more items and is not desirable.

Principal-component analysis showed that the first component explained 43% of variance when using ABIS-F items (eigenvalue = 8.68), respectively 45% with the reduced ABIS-R-F (eigenvalue = 6.26). The scree plots clearly identified one single dimension before the “elbow”, also underlining the unidimensionality of the test.

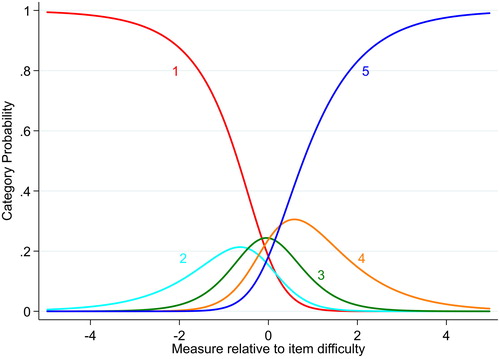

The rating-scale model showed that the 20 items ABIS-F did not comply with the set criteria for category functioning. The probability of using rating categories 2, 3, and 4 was never higher than receiving other ratings (). Item measures () ranged from −0.86 (item 19) to 0.77 (item 5).

Table 4. Item calibrations (measure) with standard error (SE) and Infit and Outfit mean-square statistics (MnSq) for the 20 items of Amputee Body Image Scale (ABIS-F), in order of misfit.

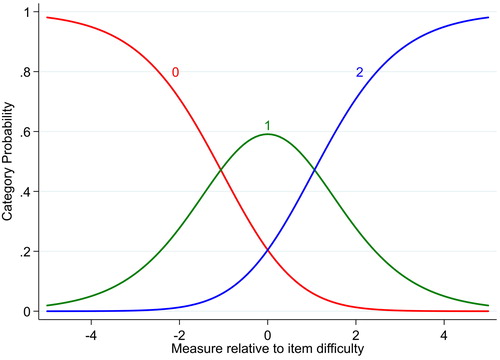

In the shortened version ABIS-R-F, category probability curves illustrate a satisfactory category functioning (). Item measures () ranged from −1.45 (item 3) to 1.81 (item 4), and no missfitting item was observed (all MnSq between 0.6 and 1.4). The item separation index was 4.77 (item separation reliability = 0.96), and the person separation index was 2.42 (person separation reliability = 0.85).

Table 5. Item calibrations (measure) with standard error (SE) and Infit and Outfit mean-square statistics (MnSq) for the revised 14 items of Amputee Body Image Scale (ABIS-R-F), in order of misfit.

The Standard Error of Measurement among the 24 patients was estimated at 5.35 [3.48; 7.21] for ABIS-F and 2.28 [1.41; 3.14] for ABIS-R-F. The Smallest Detectable Change in one individual was 14.82 [9.65; 19.98] for ABIS-F and 6.31 [3.91; 8.71] for ABIS-R-F. These values correspond to the smallest change in score that can be considered as above the measurement error in an individual and can thus serve as an estimate for the minimal clinically important difference. The Smallest Detectable Change measurable in a group was 3.02 [1.88; 4.17] for ABIS-F and 1.29 [0.76; 1.82] for ABIS-R-F. These values correspond to the smallest change in score that can be considered as above the measurement error, in a group of 24 subjects.

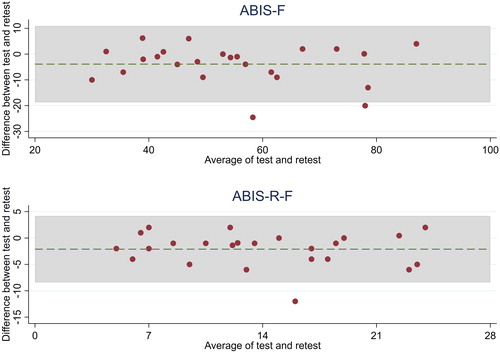

The mean difference in ABIS-F score between test and retest was −3.90 [−7.09; −0.70]) with Bland and Altman limits of agreement from −18.71 to 10.92. Two observations (= 8.3%) are outside the limits of agreement. For ABIS-R-F, the difference was −2.12 [−3.48; −0.76] and limits of agreement ranged from −8.43 to 4.19. One single observation (= 4.2%) lies outside these limits ().

Reliability was excellent, with an intraclass correlation of 0.87 [0.80; 0.94] for ABIS-F and 0.82 [0.71; 0.92] for ABIS-R-F, both being higher than the recommended minimum standard of 0.70 [Citation39].

No patient obtained a score of 20 or 100 points in ABIS-F. With ABIS-R-F, 1 patient (= 1.0%) had a score of 0 and 2 (= 2.0%) obtained the maximum score of 28, showing absence of floor or ceiling effects in both scales.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to make a cross cultural adaptation of the ABIS for French speaking persons with a lower-limb amputation. The French translation and adaptation of the ABIS and its short version ABIS-R was made according to Beaton’s recommendations [Citation20]. No important difficulty was encountered during the translation process and the questionnaire was well accepted by patients. The results in this study showed that the French versions of the ABIS, in the original form and in the shorter form, were reliable for the measurement of body image perception in French speaking persons with a lower-limb amputation and thus we propose to use the shorter form, the ABIS-R-F.

The Rasch analysis showed results very similar to those of the original English version [Citation17], assessing the cross-cultural validity of the questionnaire. The rating-scale diagnostics showed some disordered thresholds in the original ABIS-F, and confirmed the appropriateness of collapsing categories in the reduced ABIS-R-F. This modification eliminates underused categories, and the inability of respondents to discern between categories. Moreover, the ABIS-R-F showed a wide spread of item difficulties (from −1.45 to 1.81).

In our study, internal consistency measured with Cronbach’s α, was excellent for ABIS-F and ABIS-R-F, 0.87 and 0.82, respectively, and could be compared to the originals (Cronbach’s α 0.88 [Citation4] and 0.84 [Citation17], respectively). Test–retest was also excellent with an intraclass correlation of 0.87 for ABIS-F and 0.82 for ABIS-R-F. No test-retest reliability was mentioned for the ABIS original [Citation4] and ABIS-R [Citation17]. Our results were comparable to Bumin et al. [Citation18] who found that test-retest reliability in the ABIS Turkish version was 0.94 and to Lai et al. [Citation19] who found 0.86 for the ABIS Chinese version.

No floor or ceiling effects were found for the total score of ABIS-F and ABIS-R-F, indicating a good content validity and a good reliability [Citation32] of the questionnaires. For the original ABIS and ABIS-R nor for the adaptations in Turkish and Chinese, no information on floor or ceiling effects was available.

The correlations between ABIS-F and SF-36 were quite low and negative (see ). The low correlation may be explained by the fact that the SF-36 is a generic questionnaire for quality of life perception, not specific to amputees. The two questionnaires score in opposite direction and that explains the negativity of the correlation. A higher SF-36 score indicates a better quality of life, but a higher ABIS score means a poorer body image perception.

The correlations between ABIS-F and the Brief Pain Inventory showed a quite poor correlation with pain intensity but were much higher with pain interference with activities. Relative to the correlation with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale, a highest body image disturbance was associated with higher score in the anxiety and depression scale.

Another original point in this study was the association between ABIS-F or ABIS-R-F and items of the Prosthetic Profile of the Amputee. Patients who suffer from phantom pain and those who have trouble with putting their prosthesis on had a poorer body image. Patients whose relatives completely accepted their amputation and their prosthesis had a better body image.

We concluded that there was a relation between body image perception and these factors: anxiety, depression, pain interference, phantom pain, prosthesis’ use ease and relatives’ acceptance. In the original ABIS article [Citation4], Breakey found a positive relationship between the ABIS scale and the Clinical Anxiety Scale (0.57), similar to our results (0.51 for the ABIS-F and 0.52 for the ABIS-R-F). No correlation between anxiety and ABIS was made by other authors [Citation17–19] and there was no previous correlation made with the other factors.

A strength of our study was a Smallest Detectable Change that we proposed, 14.82 for ABIS-F and 6.31 for ABIS-R-F. These values corresponded to the smallest change in score that could be considered as above the measurement error in an individual. This was not published in the former studies. In the absence of a minimal clinically important difference described in previous ABIS studies, we could use the Smallest Detectable Change as an estimate for it [Citation40]. That means that the score has to vary of 14.82 points minimum in the ABIS-F or 6.31 points in the ABIS-R-F to conclude that there is an evolution in the body image perception for a person with a lower-limb amputation. This can be used to measure patient’s body image satisfaction evolution. These values could also be useful to calculate the sample size required. Future research should identify the minimal clinically important difference.

For the reproducibility evaluation, 24 patients answered the ABIS-F twice, which is less than recommended by some [Citation32], although no clear recommendations exist [Citation41]. The precision of estimations (length of 95% CI) of SEM, SDCind or ICC would be improved with a larger sample size, but the estimated values should not change much. Since the observed values were satisfactory, we are confident about the reliability of ABIS-F and ABIS-R-F.

As a limitation for this study, we can note that the correlations’ results are valid in a population of people with a lower-limb amputation living at home, with a quite good adaption to the amputation, and wearing a prosthesis. Future research should explore if the correlations are similar in different populations, in a home care resident population for example.

Conclusions

This study was successful in developing a French cross cultural adaptation and validation of the ABIS-F and ABIS-R-F. The French versions of ABIS and ABIS-R could be used with confidence in patients with lower limb amputation. The short form (ABIS-R-F) is as reliable as the long form and has a better response structure. Moreover, it will take a shorter time for the patient as for the examiner. Thus we propose to use it, instead of the long form.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Laure Huchon (Institut Régional de Réadaptation, Nancy), and Khalid Segrouchni (Wallis Canton Hospital, Sion) for their active help in collecting the data, and all patients for their participation. The authors also thank Viviane Dufour (Institute for Research in Rehabilitation, Sion) for the preparation of questionnaires, mailings, and for help in formatting the database.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Frierson RL, Lippmann SB. Psychiatric consultation for acute amputees: report of a ten-year experience. Psychosomatics. 1987;28:183–189.

- Kashani JH, Frank RG, Kashani SR, et al. Depression among amputees. J Clinic Psychiatry. 1983;44:256–258.

- Horgan O, MacLachlan M. Psychosocial adjustment to lower-limb amputation: a review. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:837–850.

- Breakey JW. Body image: the lower-limb amputee. J Prosthet Orthot. 1997;9:58–66.

- Rybarczyk B, Nyenhuis DL, Nicholas JJ, et al. Body image, perceived social stigma, and the prediction of psychosocial adjustment to leg amputation. Rehab Psychol. 1995;40:95.

- Dion K, Berscheid E, Walster E. What is beautiful is good. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1972;24:285

- Murray CD, Fox J. Body image and prosthesis satisfaction in the lower limb amputee. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24:925–931.

- Parkes M, Napier M. Psychiatric sequelae of amputation. Brit J Psychiatry. 1975;9:440–446.

- Fisher K, Hanspal R. Body image and patients with amputations: does the prosthesis maintain the balance?. Int J Rehab Res. 1998;21:355–364.

- Atherton R, Robertson N. Psychological adjustment to lower limb amputation amongst prosthesis users. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:1201–1209.

- Woods L, Hevey D, Ryall N, et al. Sex after amputation: the relationships between sexual functioning, body image, mood and anxiety in persons with a lower limb amputation. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:1663–1670.

- Holzer LA, Sevelda F, Fraberger G, et al. Body image and self-esteem in lower-limb amputees. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92943

- Wetterhahn KA, Hanson C, Levy CE. Effect of participation in physical activity on body image of amputees. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81:194–201.

- Murray CD. Being like everybody else: the personal meanings of being a prosthesis user. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:573–581.

- Murray CD. The social meanings of prosthesis use. J Health Psychol. 2005;10:425–441.

- Murray CD, Forshaw MJ. The experience of amputation and prosthesis use for adults: a metasynthesis. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:1133–1142.

- Gallagher P, Horgan O, Franchignoni F, et al. Body image in people with lower-limb amputation: a Rasch analysis of the Amputee Body Image Scale. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86:205–215.

- Bumin G, Bayramlar K, Yakut Y, et al. Cross cultural adaptation and reliability of the Turkish version of Amputee Body Image Scale (ABIS). Bmr. 2009;22:11–16.

- Lai FH, Wong E, Wong SK, et al. Development and validation of a Body Image Assessment for patient after lower limb amputation—the Chinese Amputee Body Image Scale-CABIS—. Asian J Occup Ther. 2005;4:1–11.

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186–3191.

- Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1417–1432.

- Acquadro C, Conway K, Hareendran A, et al. Literature review of methods to translate health-related quality of life questionnaires for use in multinational clinical trials. Value in Health. 2008;11:509–521.

- Leplège A, Ecosse E, Verdier A, et al. The French SF-36 Health Survey: translation, cultural adaptation and preliminary psychometric evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1013–1023.

- Perneger TV, Leplège A, Etter J-F, et al. Validation of a French-language version of the MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) in young healthy adults. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48:1051–1060.

- Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;2:98–483.

- Cleeland C, Ryan K. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singap. 1994;23:129–138.

- Poundja J, Fikretoglu D, Guay S, et al. Validation of the French version of the brief pain inventory in Canadian veterans suffering from traumatic stress. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;33:720–726.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370.

- Bocéréan C, Dupret E. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in a large sample of French employees. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:354.

- Gauthier-Gagnon C, Grisé M-C. Prosthetic profile of the amputee questionnaire: validity and reliability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:1309–1314.

- Fermanian J. Validation of assessment scales in physical medicine and rehabilitation: how are psychometric properties determined? Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2005;48:281–287.

- Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42.

- Hattie J. Methodology review: assessing unidimensionality of tests and items. App Psycholog Measurement. 1985;9:139–164.

- Linacre JM. Investigating rating scale category utility. J Outcome Measurement. 1999;3:103–122.

- Bland JM, Altman D. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. The Lancet. 1986;327:307–310.

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:420.

- McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:30.

- McHorney CA, Tarlov AR. Individual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res. 1995;4:293–307.

- Oliva TA, Oliver RL, MacMillan IC. A catastrophe model for developing service satisfaction strategies. J Market. 1992;56:83–95.

- Copay AG, Subach BR, Glassman SD, et al. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J. 2007;7:541–546.

- Anthoine E, Moret L, Regnault A, et al. Sample size used to validate a scale: a review of publications on newly-developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:2.