Abstract

Purpose

This study explored audiologists’ perspectives regarding their interactions with workers with hearing loss (WHL).

Materials and methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with twenty-five audiologists working in the National Health Service (NHS) and independent companies (IC) in the UK and were thematically analysed.

Results

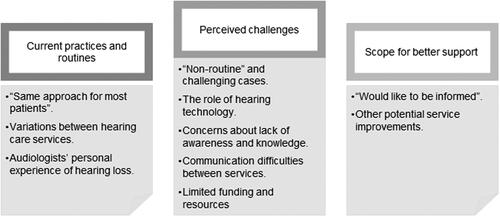

The developed themes and sub-themes (shown in parenthesis) are (1) Current practices and routines (Same approach for most patients; Variations between hearing care services; Audiologists’ personal experience of hearing loss) (2) Perceived challenges (Non-routine and challenging cases; The role of hearing technology; Concerns about lack of awareness and knowledge; Communication difficulties between services, Limited funding and resources) (3) Scope for better support (Would like to be informed; Other potential service improvements).

Conclusions

This study revealed that audiologists’ perceived deficiencies in the hearing rehabilitation for WHL and identified ways to improve it. Key priorities for improvement were found to include addressing audiologists’ informational and training needs, facilitating WHLs’ access to appointments, improving communication between services, raising awareness in the workplace, developing relevant resources and extending funding for provision of longer appointments and hearing technologies. This is the first time this information has been reported in the literature. Opportunities for conducting further research in this area are suggested.

Workers with hearing loss face many challenges in work life and have the option of audiologic rehabilitation to alleviate their difficulties and improve their wellbeing; however, this study suggests that workers' audiological care needs improvements.

Audiologists should assess and consider patients' work needs and psychosocial concerns in consultations to provide personalised care.

Audiology educational programmes, services, and the healthcare system can assist audiologists in helping workers with hearing loss by providing updated knowledge, continuous training and improved interprofessional communication and patients’ access to useful resources.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Hearing loss is an increasingly prevalent long-term health condition that impacts people’s health and lives, including various detriments to their working life. Workers with hearing loss (WHL) face hearing and communication difficulties at the workplace [Citation1–5] affecting their sense of job control and performance [Citation2,Citation6] and causing stress [Citation2,Citation3,Citation6,Citation7], tiredness and increased need for recovery after work [Citation5,Citation8], in addition to social integration difficulties at work [Citation3,Citation9]. They are less likely to be in employment compared to normal hearers; for the year 2019, the proportion of working-age persons who were in employment among persons with hearing loss (61.1%) [Citation10] was lower than that for the general working-age population (76.1%) in the UK [Citation11], which was also the case in previous years, despite improving over time. WHL also face financial difficulties [Citation12,Citation13], costing the UK economy £25 billion output loss yearly due to unemployment and lost productivity [Citation12,Citation14].

A recent scoping review synthesized the literature about working life's key issues relating to hearing loss and summed up the reported impacts of hearing loss on WHLs’ work life and well-being [Citation15]. The authors also detected many critical deficiencies in the literature, including a general lack of published research focusing on WHL during the last three decades, an absence of a multidimensional perspective that considers the individual in working life, societal and organizational contexts, and suggested WHLs’ vocational rehabilitation deficiencies.

It may be necessary to gain a better understanding of the detrimental effects of hearing loss on working-age people and society in order to deal with them. The population of WHL is growing continuously due to people living and working longer. Therefore, avoiding these detrimental impacts is crucial and could be done by ensuring WHL are receiving optimal rehabilitation that promotes healthy work-life, improves their well-being, and reduces financial losses at the level of the individual and society.

Reviewing the UK literature revealed that quality research and information relating to WHL and the involvement and efficiency of supporting services in assisting them is very limited. While some research focusing on WHL and their rehabilitation has been found to be conducted in a few countries at the international level, including Canada, Australia, Netherlands, Sweden, USA, [Citation1,Citation16–21], there is still a general lack of understanding of how audiologists and audiology services are supporting WHL and a lack of cost-benefit evaluation of audiological rehabilitation of WHL.

In the UK, in particular, audiologists are the main point of contact for WHL for help with hearing difficulties, and it is not well understood how audiologists support them. For instance, how audiologists conduct audiology appointments for WHL and how they manage WHL is largely unknown. The only found information comes from two research reports,’ Unlimited Potentials’ [Citation3] and ‘Managing hearing loss’ [Citation22], published online by the charity organization Royal National Institute for Deaf People. The experiences of WHL with their employers and audiology services were explored, as well as assessing the benefit of services targeting employed patients or those seeking employment, such as lip-reading and assistive listening devices (ALDs). The Royal National Institute for Deaf People research results suggest that audiologists in the UK did not give attention to issues associated with hearing loss in the workplace and offered the participants little help and information concerning their work-related problems. Their reports, however, lacked essential methodological details and a scholarly publishing procedure indicating there is a need for high quality evidence in this area. There is also a scarcity of research investigating audiologists’ views and the underlying barriers and facilitators to efficient WHLs’ audiological rehabilitation.

A few papers at the international level have commented on or have elements related to WHL’s audiologic care, although this is not the papers’ main topics. For example, a pilot survey was conducted in the United States to explore the experiences of 32 health care professionals affected by hearing loss and the communication strategies they employ at work [Citation20]. The survey included a question asking them about finding an audiologist to support them. More than half of these professionals reported difficulty in finding an audiologist knowledgeable in managing work-related needs.

Another study published in 2013 looked into Canadian WHLs’ experiences in addressing work challenges [Citation23]. In the interviews, the interviewers asked the workers a few questions about the support of professionals relating to work life. Many of their participants reported not having a discussion with their audiologists about work difficulties and reported not receiving work-related support. Overall, there is a consensus within the limited amount of literature on this topic of a general lack of occupational perspective in audiology appointments for WHL. No previous study has explored this in any depth, or sought to determine the underlying factors. High-quality research is needed to explore how audiologists in the UK perceive their support of WHL and explore the facilitators of/barriers to audiologists’ efficient support and interaction with WHL. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the audiological rehabilitation for WHL from the perspectives of audiologists and answer two research questions:

What are audiologists’ experiences and views of working with patients who work?

What do audiologists think are the facilitators and barriers to effectively supporting these patients?

The results may enhance the understanding of these issues and help promote practice and policy for WHL audiological rehabilitation.

Materials and methods

Design

A qualitative research paradigm was employed utilizing a pragmatic approach. The pragmatic approach in health research is suitable because it focuses on obtaining rigorous information that will serve decision-taking [Citation24]. This study allowed the researcher to focus on audiologists’ perspectives in the context of pragmatically utilizing the results to serve research and practice. The first author MZ (female) interviewed (1:1) audiologists working in the UK. Audiologists who agreed to participate filled in a questionnaire and signed a consent form. The questionnaire gathered demographic information and details about their work, such as their audiological work area, the service they worked for and their experience. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and thematically analysed by the first author. Ethical approval was obtained from the research ethics committee of the Institute of Sound and Vibration Research and the Health Research Authority and Health and Care Research Wales.

Participants

An email was sent to various Audiology departments and services in the UK, inviting them to participate in the study. 84 NHS audiology departments and eight IC (independent companies) were emailed. Those were selected based on the availability of their emails on their webpages. The research was also advertised in the British Academy of Audiology Horizons magazine, and a recruitment advert was posted on the Ida Institute Learning Hall webpage. In addition, a few audiologists who were known to the researcher were approached verbally. A purposive sampling strategy was chosen to select audiologists who work in adult rehabilitation clinics or cochlear implant services in the UK. This helped to gather a wide range of experiences and, at the same time, capture common perspectives. The characteristics of the recruited audiologists are summarized in .

Table 1. Participants' characteristics.

The interviews

Eleven of the audiologists were interviewed face-to-face, ten via telephone calls and four via online video calls. At the beginning of the interviews, the researcher introduced herself as a PhD student at the University of Southampton. The research topic and its purpose were described. The participants were asked to discuss three open-ended, semi-structured questions (Supplementary Appendix A). The researcher used follow-up prompts when needed. Four interviews were conducted first for piloting and resulted in minor edits to make the questions clearer. During the interviews and afterwards, the interviewer kept diaries to help stay close to the data and be reflexive. The interviews' duration ranged from 12 to 37 min (mean = 24.6 min, standard deviation = 5.8). Saturation of data was reached with 13 interviews. However, sampling continued until 25 participants had been interviewed. The reason was to sample more NHS audiologists because, during the initial analysis, some variations were noted between the NHS and IC audiologists’ perspectives.

Analysis

The thematic analysis was informed by the steps described by Braun and Clarke [Citation25,Citation26]. Grounded theory techniques including “word coding”, “line by line coding”, “sentence coding”, and making comparisons were borrowed, where deemed helpful. The transcribed interviews were transferred to NVIVO software (Version 12) for qualitative data management. An initial inductive coding followed. For the first 13 interviews, open coding was used to fully code the interviews using very low-level codes. This was done by tagging each word, sentence or line with code (grounded theory techniques) to stay close to the data and pay attention to detail [Citation27]. Simultaneously, higher-level codes were devised to tag more than one sentence with a general code. The general codes were then spliced if required. The analysis of the remaining interviews resulted in a minimal number of additional codes. The codes underwent reordering, refinement and categorization at that stage to form fewer and more powerful groupings consistent with the method of “splicing and linking” described by Dey [Citation28]. Through this process, the themes and subthemes were generated. Each theme and subtheme was named and defined in a coding manual.

The reliability and validity of the analysis were checked in two stages. Firstly, the coding manual was shared with another researcher, KA, who is experienced in qualitative data analysis but not in the interview subject matter. Six interviews (24%) were analysed independently by KA using the coding manual. Any inter-coder discrepancies were then discussed, and an inter-coder agreement was achieved [Citation29]. This process resulted in no changes to the coding manual. Secondly, ‘participant validation’ was checked by sending a summary of the interim results to all study participants, providing an opportunity to change and add information. Five participants responded, and all confirmed that the results were in line with their experiences. Their feedback was taken into consideration, and minor amendments were made.

Results

The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist was utilized to determine the information to be included in this paper [Citation30] (Supplementary Appendix B). In the interviews, the audiologists reported various insightful experiences and views regarding their appointments with WHL. Three main themes were generated, and these were subdivided into ten sub-themes, as shown in . Explanations of all the themes and subthemes supported by extracts from the interviews are presented in the following sections. Participants’ identifiers are present at the end of each extract and include the participant’s number, area of work, and the type of service they were working in at the time of the study. The identifiers are explained in below. The text between box brackets [ ] in the extracts is not the interviewee’s word; rather it is an explanation added by the researcher to clarify the context.

Table 2. Participants' identifiers.

Theme 1: Current practices and routines

This theme describes the audiologists’ perspectives relating to their practices and routines in WHL appointments. The following three subthemes represent these perspectives.

Subtheme 1.1: “Same approach for most patients”

Most of the audiologists indicated that the appointments are the same whether the patient works or not. They perceived audiology appointments as very prescriptive and repetitive, and that work might not be taken into account in consultations. Only a very small number said that work-specific needs dictated different support methods but that the rest of the appointment would be the same.

“The appointments are very standard through all the patients. There is no differentiation if they are working or not.” (P 6 AR IC AQP)

Subtheme 1.2: Variations between hearing care services

During the early stages of conducting the interviews, the researcher noticed differing practices and perspectives among audiologists, especially when comparing those working in different types of services. The analysis indicated that: 1) the audiologists themselves had different approaches in their assessment of patients’ work difficulties, the tests they carried out and the support they offered to WHL, even within the same type of service; 2) the services in which the audiologists worked were different in many aspects, influencing WHLs’ care. These two points are explained further below.

Variations between the audiologists:

Firstly, the audiologists discussed how they asked about their patients’ difficulties in relation to work during the appointment. Each audiologist had a different approach, but very few of them reported asking specific questions about work. Most asked general questions like “What has brought you here today?” or used the COSI questionnaire and waited for the patient to volunteer this information.

I must admit… I tend to ask them, “How are you getting on with it?” generally, but… don’t ask any specific questions about work… it’s possible to miss it… unless they brought it up. (P 9 CI IC AQP)

They explained that exploring work-life would require time and additional consideration beyond what they were accustomed to providing. Further, some routines are prioritised.

It's the time pressure… I suppose it's harder to suddenly go out the box and look at a particular person's needs, if they're are not the average person coming through… because you're automatically going to do the hearing test… get the COSI [Client Oriented Scale of Improvement] and REMs [Real Ear Measurements] done, gotta get them out. (P 10 AR IC AQP)

Two audiologists expressed concerns about asking patients about their work.

You don't want to ask about work specifically because it might be that someone doesn't have a, like, paid job… you don't necessarily want to raise that. If you ask… then you're implying that they should be working. (P 13 AR NHS)

Thus, it appeared that exploring patients' difficulties in relation to work varies between audiologists and cannot be considered a routine activity.

Secondly, the audiologists talked about the range of hearing tests they carried out for WHL. Pure tone audiometry, including otoscopy, was the usual test undertaken by all and the sole test for many.

We don't do any other tests, it's pure tone audiometry and otoscopy for everybody. (P 7 AR IC AQP)

Other than pure tone audiometry, the tests performed varied and included tympanometry, speech perception tests, uncomfortable loudness levels, feedback tests and real ear measurements. Some do tympanometry routinely and irrespective of its need.

We do tympanometry routinely on everybody, and not just if we think they might have something wrong. (P 4 AR IC)

Some of the audiologists thought that speech perception tests help in counselling working patients.

A lot of patients who've got normal or very mild high frequencies hearing loss are really struggling in their work environments… for those patients I would do speech in noise tests to help mainly with counselling really, for them to have an idea with why they're experiencing the difficulties… and what strategies we could work with them. (P 17 AR NHS)

Overall, the tests done for WHL, other than pure tone audiometry, exhibited a diversity of practice between the different audiologists.

Thirdly, provision of hearing aids or cochlear implants dominated the discussions about support and were found to be the main focus, if not the sole focus, in the management.

The sort of things we normally do is talk to them about hearing device fitting, whether that be hearing aid… possibly cochlear implants. (P 12 AR NHS)

The criteria to fit hearing aids were different. Some thought patients' difficulties dictated the decision, while others relied on the results of pure tone audiometry.

A lot of it is down to where the loss is on the graph. (P 8 AR IC)

You have to be flexible, you can't really say 'I'd only fit hearing aids is going to be if A B C; you have to take into consideration… the difficulties they are having. (P 16 AR NHS)

One audiologist raised a similar issue regarding the criteria for obtaining a cochlear implant from the NHS and argued that some WHL could benefit from cochlear implantation, especially if their job was hearing demanding, but the current criteria for who can get a cochlear implant from the NHS do not take into account functionality issues like work.

For candidacy of implantation, the work situation is considered completely irrelevant, unimportant… it has no bearing whatsoever. (P 9 CI IC AQP)

The additional support methods included offering or mentioning ALD, discussing communication tactics, advice on making adjustments at work, workshops and drop-in sessions for devices, providing written information and signposting to other services that could help (Access to Work, DeafPlus, hearing therapy services, social services, occupational services, lip-reading classes). The most popular suggestions were about ALD and Access to Work. Each of the others was mentioned by one or a few audiologists, and they did not necessarily offer it to every patient.

Sometimes we'll discuss listening tactics. (P 23 AR IC AQP)

Regarding offering, mentioning or demonstrating ALD, some audiologists said they did it if deemed helpful for work. However, many barriers prevented them from offering this kind of support (Further details in the theme Perceived challenges).

We may look at solutions for certain situations, for example an additional microphone for meeting situations. (P 4 AR IC)

Similarly, many barriers hindered signposting patients to charities, organizations or services that can help them, especially Access to Work, to obtain help for devices. Nevertheless, a few audiologists said they sometimes mention that but with hesitance (more about this in the theme Perceived challenges).

"Access to Work perhaps works a bit better for them, is to have more support from their employer… We sometimes mention that" (P 3 AR IC)

Generally, the audiologists reported that they supported WHL differently, apart from advising on and fitting hearing aids and cochlear implants. The range of the other support methods seems to be narrowly utilized.

Variations between services

When it comes to caring for WHL, most audiologists discussed the differences between NHS and IC services in great detail. They also compared services that offer team care, such as cochlear implants services, and those that do not, such as most audiology clinics.

The NHS audiologists and those in IC, and those who moved between services, spoke about two main differences between the NHS and independent services: access to services and the support offered. It appears that appointments in most audiology departments in the NHS are less accessible for working patients than those in IC. However, there could be some variation between the NHS audiology departments.

The only thing that possibly would impact on the service that we offer to that particular… demographic working population is our opening hours… it can be difficult for them to access the service. (P 15 AR NHS)

Moreover, the audiologists stated that hearing technologies offered in IC are more helpful to workers. IC have more technology choices like ALD, and their hearing aids are more advanced and have better cosmetic options.

Those that do… have generally come to see us because anything else they tried, NHS hearing aids aren't helping them enough in work environments. (P 8 AR IC)

The audiologists believed that services using a team approach to discuss patients’ cases together, such as cochlear implant services, provide better care to WHL, especially if that team includes a hearing therapist. But most adult rehabilitation services do not use a team approach.

If they… need further support because they're not adjusting to their hearing loss at work, so they need further support for ALD, all that sort of thing… we can…refer in, into their service {hearing therapists} … they are part of the audiology team. (P 15 AR NHS)

Subtheme 1.3: Audiologist's personal experience of hearing loss

Many audiologists found it helpful to have personal experience of hearing loss, whether it was being affected by hearing loss themselves, their colleagues at work, or even having a WHL within the family. They believed that this positively influenced the care they provided to WHL.

I wear hearing aids… for me, that quite often of an advantage because they're talking to someone who can relate, can advise, so that helps… I've had the same sort of experiences. (P 8 AR IC)

I work with people who have hearing loss… they have all this knowledge about… what someone with a hearing loss is entitled to, what they can be directed to and what people should be doing… I'm quite lucky to have that resource and if I had questions, I would go to them. (P 11 CI IC AQP)

Theme 2: Perceived challenges

The audiologists reported experiencing several challenges when dealing with WHL and focused on five main issues, presented in the following subthemes.

Subtheme 2.1: "Non-routine" and challenging cases

All the audiologists perceived WHL as a special kind of patient. Their appointments were perceived challenging and "non-routine" due to many reasons. The audiologists held this view because of not coming across patients who work very often in clinics. Moreover, WHL has more specific needs, especially when compared to the average patient coming through (presbycusis), and they seem more informed and have hearing loss acceptance difficulties and high expectations. All require more time in the appointment.

Their [WHL] listening situations are more complex than I would say for… traditional 70- to 80-year-old who's having hearing loss… that their listening needs, I guess, are less complex or less challenging… their expectations perhaps were a little different as well…I think people… who may be a little bit older… their expectations are lower… or it might be younger people at work, I guess they're more well-informed, so they may be read on the internet the sorts of things that might be available in terms of technology… They're coming with more specific questions… so you're trying to do your standard test batch and your standard, um, structured interview, but at the same time they've got additional specific needs… that you maybe wouldn't get in more routine patients. (P 12 AR NHS)

On the other hand, a few of the audiologists pointed out that since WHL are mostly younger, fitting them with hearing aids was more efficient than when working with older adults.

With the younger, working adults, it's a lot more efficient… because, for example, when you are fitting them… they more quickly get a grasp of like what's going on and so you can… get through things up quicker. (P 14 AR NHS)

Subtheme 2.2: The role of hearing technology

All the interviewees had a positive attitude towards hearing technologies' in supporting WHL. The discussions were about hearing aids or cochlear implants, ALD, mobile applications and tele-audiology.

A range of wireless devices… could be really helpful for working-age adults… and we've had good feedback that they work well. (P 14 AR NHS)

The challenges that were brought up regarding hearing technologies were:

Hearing aids help, but they still have their limitations and alone cannot fix all work difficulties.

Hearing aids really are the biggest priority, but I know they don't always meet all of the needs. (P 2 AR IC AQP)

The audiologists think they lack experience in dealing with some of the hearing technologies, mainly ALD.

We're not getting enough experience of using it (ALD) to build up… when we do use it we're scared of it. (P 5 AR IC AQP)

Audiologists find it hard to stay up-to-date: hearing technology is advancing quickly, the technology keeps changing, and there is so much out there. Not only NHS audiologists but also most IC audiologists expressed the same concern.

There's so much equipment out there that's… beyond our knowledge or beyond our professional boundaries… it's hard… to help them make that specific decision on what to buy… that's stopping me from helping them any more than what I do already. (P 18 AR NHS)

Subtheme 2.3: Concerns about lack of awareness and knowledge

The audiologists expressed concerns regarding their own lack of awareness and knowledge, and the lack of awareness among WHL themselves, people in the workplaces, such as colleagues and employers, and people in the general community. Most of the audiologists discussed at least one of these aspects. The most popular point of discussion was the lack of awareness and knowledge among audiologists themselves. Some of the audiologists talked about being unaware of the available help that can benefit working patients.

Actually I, I tend not to be completely aware of the resources that are available. (P 1 CI IC AQP)

Many others talked about Access to Work, commenting that they did not know much about it and were not confident that they knew how it works, which affected their advice to patients.

"Access to Work, I know that it's there… but I don't necessarily know what they are exactly entitled or what they can do." (P 2 AR IC AQP)

Many expressed significant concern that their education and training to become audiologists lacked specifics about the working population.

I can't remember there being a topic on Access to Work when I studied… I don't really remember there being anything on… work situations. (P 11 CI IC AQP)

A few others felt unsure whose responsibility it is to support WHL.

There are so many barriers there are so many things we don't know. Um, I don't know whose responsibility is to, to help with that [helping WHL with work] (P 17 AR NHS)

Subtheme 2.4: Communication difficulties between services

Many of the audiologists experienced difficulties communicating with other services or organizations to obtain information. This issue was viewed as a barrier to the help they could give WHL, whether that was between audiology services themselves, between audiology services and other services like social services, or between audiologists and patients' employers.

It was a big barrier to get in touch, like with the social services, to know the extra solutions for my patients. And it is also a barrier from the NHS itself… we are suppliers of NHS hearing aids, but we have no communication with ENT [Ear Nose Throat specialists] or GPs [General Practitioners]. (P 6 AR IC AQP)

One audiologist was upset because the way the service is structured under the AQP scheme meant the services did not talk to each other.

The Qualified provider status, in theory, we're all competitors so we don't really talk to anyone which is a shame… I'm quite cross about that 'cause, um, as an audiologist… all that shared knowledge is cut off. I don't know what's going on in [place names redacted] or [place name redacted] or, you know? They might have some really good ideas but because we're in competition with them we can't really talk to them… it's fragmented. (P 10 AR IC)

A few audiologists also spoke about the lack of communication between them and patients' employers.

We don't liaise with their work specifically. Occasionally people might ask us to write a supporting letter… if they're having trouble with their employers. (P 19 AR NHS)

Subtheme 2.5: Limited funding and resources

Funding issues, as well as lack of resources, were a concern of many of the audiologists. The resources mentioned included leaflets with helpful information for working patients, contact information of services that can help WHL, suitable speech tests and the ability to carry them out, technologically advanced hearing aids, ALD and, finally, the ability of audiologists to visit the workplace of their patients to assess its accessibility and make better recommendations. Most of these resources were perceived to be limited for financial reasons.

A lot of the information leaflets they've got a lot of old people on them… people talking in in situations that are maybe not relevant to young working people. (P 17 AR NHS)

I would go into the place at work… that's what we do with children in education… that doesn't happen at work, and yet… one of the arguments about cochlear implants is that it improves people's productivity and makes them able to work. So, it's a kind of funny disconnection there… we're not paid to do that. (P 9 CI IC AQP)

Many audiologists talked about the financial burden behind hearing technologies. Most of them commented on the NHS fund for hearing technologies and argued that the NHS's funded hearing technology is limited. In addition, the NHS does not pay for ALD through its departments, despite that these could help people who work.

The NHS at the moment provides hearing aids, anything else is classed as hearing aid accessories… So, the, the bits and pieces like the Roger pen… we do not provide that… we don't have the budget for that. (P 16 AR NHS)

Some of the audiologists discussed access to ALD and their funding by the NHS through the Access to Work scheme. Two of them argued that, although the NHS can partially fund ALD, the kind of ALD given to patients are not necessarily the best for them, i.e. some of the audiologists thought that Access to Work is not an efficient resource.

If they go around down the Access to Work route, they quite often get told that they can only have a Roger Pen, for which they need extra adaptors and everything, which makes it quite clunky. The whole idea here is it's supposed to be they are a working-age, they want something that's efficient that isn't really obtrusive. (P 14 AR NHS)

On the other hand, a few had a different, more positive view towards Access to Work as a resource.

if you've got somebody… who's really struggling at work to enable them to stay at work, Access to Work is a very good tool to use… you're half government funded and half the employer. (P 15 AR NHS)

Finally, a very small number said that they did have enough resources, despite being financially constrained.

I think that the resources that are available to us are fairly extensive… it tends to be more of a help than a hindrance. I don't think we are hindered particularly, other than possibly financially, but I think that's probably true across the NHS. (P 15 AR NHS)

In general, however, most audiologists think there are limited resources and funding, which could be negatively affecting the service they provide to WHL.

Theme 3: Scope for better support

The audiologists shared a standard view of improving the audiological rehabilitation of WHL. They "would like to be informed". Moreover, they made various suggestions that could help improve the support given to WHL by their audiologists.

Subtheme 3.1: "Would like to be informed"

Most audiologists envisioned providing a better service for working patients if they were empowered by knowledge; thus, they would like to be well informed about WHL and their help.

I think there's a huge scope… for extra support in this area… I think we will be better able to support people if we kind of knew what we were dealing with, really. (P 1 CI IC)

Many of the audiologists expressed the need for a directory containing information relevant to this population, including information about what support is available for WHL, whether in terms of hearing technologies, support services and their contact details, or information about what WHL are entitled to.

It would just be useful to know a bit more. I know that there is a lot of information out there about all the products but it's all quite all over the place, so if it were to be able to put together in one kind of booklet or something that would be quite helpful. (P 2 AR IC AQP)

Two of the audiologists also suggested having work-related education in audiology training. One of them said:

You could have… the university courses do modules on work-based information, that would be useful, so the students could refer to it. (P 10 AR IC AQP)

Experience, ongoing learning and training were seen to be useful from the audiologist's point of view, but they need more of it.

Additional training might help. I think it's important to make sure that you're up to date with, you know… what other services are available or ALD, because its moving on so quickly. (P 12 AR NHS)

The need for specific literature on WHL was also raised by a few of the audiologists, reflecting the significant gap the researcher found when reviewing the literature on WHL.

Often we draw on skills that we have from other areas of audiology… we kind of assume that they're relevant to that [relevant to WHL], we don't really know that for certain… it's like kind of lack of research, isn't it really? (P 1 CI IC AQP)

Subtheme 3.2: Other potential service improvements

Besides saying they needed information and training, the audiologists were inventive in their suggestions of additional methods to improve the service to WHL, which highlights the wide scope for potential improvements. The suggestions included liaising with patients' workplaces (visiting patients' workplaces, communicating with the patient's employer, and educating the people at work about WHLs' difficulties and how to help them), educating WHL and providing them with written information to empower self-management, better communication with other services and external organizations, making funding and access to ALD through Access to Work easier and more transparent and more tailored to each patient, utilizing mobile applications and tele-audiology to enable making real-time adjustments to hearing aids, and allowing more time for the appointments if needed.

Supplementary Appendix C includes audiologists’ suggestions for improving the care for WHL.

I am quite excited by the new hearing aids… they do allow you to program them remotely… this is gonna be really useful for people at work… somebody at work could phone me at work and say: "I can't hear in this situation," and I can make real-time adjustments to their hearing aids while they are in that situation.(P 21 AR IC)

Discussion

This research presents new knowledge about audiologists' experiences when dealing with WHL and advances our understanding of the facilitators and barriers in providing support for WHL.

Limited focus on patients' work needs in audiological rehabilitation

The audiologists' accounts of their experiences related to their practices and perspectives suggest that the care offered to workers is not standardised and not necessarily tailored to their work-needs; nor is it sufficient, which echoes WHLs' accounts in previous research [Citation3,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23]. For most of the interviewees, there appeared to be a lack of focus on patients’ working life in their practice. Audiologists asking patients about their working life and offering help specific to work-life difficulties were notably the exception, confirming earlier research [Citation23]. A few audiologists were reluctant to even ask patients about their work. Audiologists must identify if their patients have work difficulties, whether in terms of accessing employment or managing their existing jobs so that the audiologists can provide informed support. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommended assessing and addressing patients' work needs by audiology service providers [Citation31]. Recognizing patients' specific needs was one of four principles the British Society of Audiology indicated to be crucial to use in routine auditory rehabilitation appointments [Citation32]. Regardless of this, most of the audiologists' in this study reported using the same approaches in assessing and managing patients whether the patient was working or not. This finding resonates with previous research indicating a lack of patient-centeredness in audiology appointments [Citation33,Citation34].

Facilitators/barriers to audiological rehabilitation for WHL and the needed improvements

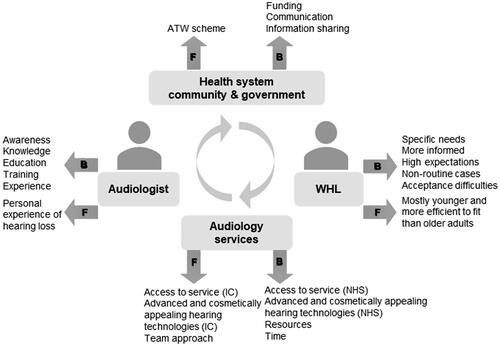

The audiologists discussed the underpinning factors affecting their experiences with, and care for, WHL (shown in ). They also highlighted the important issues that should be prioritized and the scope for service improvements. In this study the facilitators and barriers for efficient rehabilitation for WHL were found to be present at the level of the health system, audiology services, audiologists and the patient, as mapped in . When all the barriers at these levels interact, it is not surprising that this results in challenging interactions and suboptimal rehabilitation for workers. Moreover, there could be additional barriers perceived by the WHL themselves, adding an extra layer of complexity. Therefore, this work's natural progression is to explore WHLs' perspectives to gain a holistic understanding.

Figure 2. The facilitators and barriers that the audiologists perceived to be affecting WHLs' audiological rehabilitation. F: facilitator; B: barrier; ATW: Access to Work; WHL: workers with hearing loss; NHS: National Health Services; IC: independent companies.

clearly shows the presence of many barriers influencing audiologists-WHLs' interactions and WHLs' rehabilitation, leaving WHLs' needs unmet. One of the key findings at the audiologists' level was their perception of lacking the information and training regarding WHL and their support, which confirms previous research [Citation21]. In this study, the audiologists reported inadequate access to information, deficiencies in information sharing with the involved parties, and the inability to keep up with the continuously emerging hearing technologies. This finding is not surprising; access to information is a basic need of healthcare professionals and could be problematic for audiologists [Citation20,Citation34], which directly influences decision-making in healthcare. Thus, it is not surprising that the audiologists saw addressing their informational and training needs as their priority.

The implication of being informed manifested in the better experiences reported by some of the audiologists who had personal experiences with hearing loss and felt it facilitated WHLs' appointments and the care they could give. This finding is in accord with other research findings in the healthcare field indicating that healthcare professionals' personal experience of the problem was found to help them be more prepared to deal with patients [Citation35,Citation36]. Their personal experiences enhance their ability to empathize with and understand the needs of their patients and have more awareness of support methods because they too once required this support. Audiologists' ongoing support should be provided from their basic education and training through to continuous in-service learning to address these informational and counselling skills needs.

The audiologists indicated that their audiology education and training appeared to have neglected the work aspect of patients' lives, reported in an earlier study [Citation21]. Therefore, the difficulties they reported when conducting consultations for WHL could be because they were unprepared to deal with this population when they started their career. They were then not accumulating the relevant experience needed due to not frequently encountering WHL in clinics, meaning such encounters are regarded as 'non-routine', and due to the lack of training opportunities and research focusing on hearing loss patients’ working lives and WHLs’ rehabilitation practice. Both audiology services and audiology research have been mainly focused on serving children and older adults and improving their care. Still, not much information and policy is available on middle-age groups, the working-age adults. For example, looking into one of the NHS audiology services improvement documents updated in 2017 reveals no consideration for improving audiology provision for WHL, but it focused on that for the other age groups [Citation37].

At the level of the WHL, the finding that audiologists consider WHL to be non-routine and challenging cases is reported for the first time in the literature. The audiologists approach appointments with WHL as 'routine' in terms of the tests they do and questions they ask, while recognizing that this group is different and has specific needs. Are WHL really challenging because of being non-routine, being more informed, having specific needs and higher expectations and acceptance difficulties, as these audiologists thought? Or did the audiologists perceive them this way because of the reported lack of knowledge, training and experience needed to support this population? Or could it be that there are priority practices, such as doing tympanometry testing for all cases that take a valuable time from the appointment that could be used in the interview or the parts of the appointment concerning management?

The answers are likely to be multifactorial. For example, if there were sufficient time in the appointment and the audiologist had sufficient resources and could easily access information, they might have not perceived WHL as challenging as they did. No doubt workers' needs and attributes could be out of the comfort zone of the audiologists. Especially in that WHLs' are more likely to be informed and have more challenging questions to audiologists because they are likely to be younger and use the internet to access information compared to the older, routine audiology patients. The emerging 'informed patient' concept has been a matter of discussion in the field of health care and appears to cause constraints on healthcare professionals, as discussed in the paper' Ignorance is Bliss Sometimes' [Citation38] but has not been studied in audiology. This study has brought to light the informed patient concept in this area and its challenge on audiologists in WHLs' appointments, signifying a need for future research in this area.

The flexibility needed to facilitate WHLs' access to audiology appointments and the hearing technologies offered were two main service aspects perceived to be affecting WHLs' care. IC were perceived to be superior in both. Patients in the UK reported previously not attending their general practitioners' appointments due to their inability to leave work [Citation39]. Similarly, this could be a difficulty facing WHL when accessing NHS audiology services, as our study indicates and is worth investigating in future work. Moreover, the results indicate that advanced and cosmetically appealing hearing technologies are offered for purchase from IC and not offered in the NHS. The NHS started offering free behind the ear hearing aids in the 1970s, which was a significant step forward. Nevertheless, the audiologists indicated they were found less helpful to WHL than the advanced hearing aids available in IC. Further, the audiologists believed that overall hearing aids alone could not help in all scenarios and suggested that ALD could be of special value for assisting WHL at work.

Having to deal with hearing device-related stigma [Citation40] and difficult listening situations at work is a huge undertaking and is critical for employees' occupational stability. They need smart and effective technologies to handle their complex hearing needs at work and they could be looking for 'discreet, modern fittings' as described by Kirkwood [Citation41] to avoid the stigma and embarrassment they experience at work [Citation3]. Therefore, making available powerful and advanced hearing technologies that are cosmetically acceptable is not a luxury but rather necessary to keep people at work. However, cost-effectiveness should be first established. There is no research on their benefit to workers, and the evidence on ALD overall is still ambivalent and only focused on the older users [Citation42] and has not targeted the younger working users.

Services offering team care and where audiologists offer counselling, like cochlear implant services, where perceived by the audiologists to be superior in WHL care. Both the present research and previous research indicate that counselling is often omitted in audiology appointments [Citation43], although one of the most frequent need workers demanded in one survey was counselling regarding how to manage workplace difficulties [Citation44]. Therefore, it could be useful if appointments for WHL incorporated some specific counselling relating to work difficulties and needs. Allowing time for that and training audiologists appropriately would improve their ability to counsel workers and offer personalized care in audiology appointments [Citation45].

All the issues identified here contribute to a picture of suboptimal audiology care for WHL, together with the audiologists' own perceptions of not being sufficiently supported by relevant resources and funding at the level of their services and the health system itself. All of these issues have important implications for audiology service delivery. A sufficient number of audiology staff who are trained to support working adults effectively is needed. Ideally, various bodies besides audiologists should offer support to WHL, including social workers, hearing therapists, occupational therapists, charity organizations like the Royal National Institute for Deaf People, and governmental policies and schemes like Access to Work, supported by employers and hearing technology companies. Nevertheless their role in supporting WHL has not been investigated and the results suggest a lack of communication between them and audiologists. Future research should explore the role of the various bodies in supporting WHL and to explore whether adequately prepared audiologists have different perceptions of WHL if they had access to the required information and resources.

This study can be utilized to provide clinical insights for readers, particularly for those involved in audiology practice and decision making. Just because of taking part in this study, some of the audiologists started reflecting on what they did in their practice with WHL and prompted them to think more about this population and what they can do to help them better.

I'm gonna still be thinking… when I see… working adults now a lot more really. (P 17 AR NHS)

The results can also be used to inform the development of standards of care for WHL and service quality improvements. The audiologists offered plenty of suggestions that could facilitate their role in the care for WHL and improve patient support. However, WHL experiences and views need to be first taken into account to understand better all their needs (this work has been done as part of a PhD study and is awaiting publication). Moreover, this research area is still embryonic, and research is needed to decide what interventions are practical, applicable, and cost-effective and should have priority and would positively impact WHL. Despite the limitations of qualitative research with a limited sample, the findings are still considered applicable to audiologists in the UK who are similar to our sample and are working in similar contexts [Citation46,Citation47].

Limitations

The study sample comprised more audiologists working in IC (15) than audiologists working in the NHS (10). This issue could have affected the results because the practices in different types of services could be different; however, many of the IC audiologists reported working in the NHS and moving between services. They reflected on their experiences when they were working in the NHS and made comparisons, which fed into the results. In addition, many of the IC provide NHS services under the AQP scheme and the participants deliberated on the differences in their experiences with the NHS and private patients in their clinics. It should also be kept in mind that the audiologists who agreed to participate could be more motivated and hold different experiences and views from the participants who did not participate. This kind of bias in research is common and often hard to avoid.

Conclusion

The literature generally lacks adequate knowledge about WHL [Citation15] and their rehabilitation. While some research about hearing loss patients and working life exist at the international level, there is a severe lack of research in the UK and a general lack of research focusing on WHLs’ support and audiological rehabilitation. This is the first study presenting audiologists' experiences and views of their appointments with WHL and outlining the key facilitators and barriers to providing quality audiological care for workers. Overall, the results suggest a lack of focus on occupational issues and patients’ work life in audiology consultations. The audiologists faced several challenges leading WHL to not be sufficiently well-supported, with variations in care between audiologists and services. The participants perceived audiologists and services offering flexible and easy access to appointments, team care, counselling, advanced hearing technologies and cosmetically appealing devices as superior in the care for WHL.

In addition, this research has highlighted the barriers perceived by the audiologists to providing care for WHL. The main obstacles were related to poor communication between services and insufficient resources and funding. Moreover, audiologists regarded WHL as challenging cases when conducting appointments and felt underequipped with information and training regarding supporting WHL. Areas where improvements are required, were outlined in this paper at an audiologist and service level and beyond.

Improvements should originate not only from audiologists but also from the individual, work organization and the educational and healthcare systems. It is not the sole responsibility of WHL and audiologists to influence the workers’ wellbeing and capacity to cope in the workplace. Audiologists also need to be supported by their departments and the healthcare system to offer improved care for their patients, for example via resources, funding, and training. A core improvement could be ensuring the audiologists are well-informed and trained and making sure they explore their patients' work life in audiology appointments. This is key to uncovering any difficulties related to work and achieving effective care through personalized goal-setting and informed support. To further our research and enhance the validity of the results, the perspectives of WHL on the same topic were explored and will be triangulated with audiologists' perspectives to be published soon.

Appendices_151021.docx

Download MS Word (25 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the University of Jordan for providing the support for the larger project from which this paper grew. The authors express their appreciation to the audiologists who participated in this study. Last but not least, special thanks to Dr Krithika Anil for checking the reliability of the interviews' coding and Dr Mark Fletcher for the constant assistance and advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Backenroth GA, Ahlner BH. Quality of life of hearing-impaired persons who have participated in audiological rehabilitation counselling. Int J Adv Couns. 2000;22(3):225–240.

- Morata TC, Themann CL, Randolph RF, et al. Working in noise with a hearing loss: perceptions from workers, supervisors, and hearing conservation program managers. Ear Hear. 2005;26(6):529–545.

- Mathews L. Unlimited potential? A research report into hearing loss in the workplace. London: Action on Hearing Loss; 2011.

- Scherich DL. Job accommodations in the workplace for persons who are deaf or hard of hearing: current practices and recommendations. J Rehab. 1996;62(2):27.

- Hua H, Anderzen-Carlsson A, Widen S, et al. Conceptions of working life among employees with mild-moderate aided hearing impairment: a phenomenographic study. Int J Audiol. 2015;54(11):873–880.

- Kramer SE, Kapteyn TS, Houtgast T. Occupational performance: comparing normally-hearing and hearing-impaired employees using the Amsterdam checklist for hearing and work. Int J Audiol. 2006;45(9):503–512.

- Gellerstedt LC, Danermark B. Hearing impairment, working life conditions, and gender. Scand J Disabil Res. 2004;6(3):225–245.

- Nachtegaal J, Kuik DJ, Anema JR, et al. Hearing status, need for recovery after work, and psychosocial work characteristics: results from an internet-based national survey on hearing. Int J Audiol. 2009;48(10):684–691.

- Canton K, Williams W. The consequences of noise-induced hearing loss on dairy farm communities in New Zealand. J Agromedicine. 2012;17(4):354–363.

- Department for Work & Pensions, Department of Health & Social care. The employment of disabled people. In: care DfWPaDoHS, editor. London (UK): Gov.UK; 2020.

- Office for National Statistics. Employment rate (aged 16 to 64, seasonally adjusted). Online: Office for National Statistics; 2021.

- Shield B. Hearing loss- Numbers and costs; evaluation of the social and economic costs of hearing impairment. In: AISBL ArfH-I. London: Brunel University London; 2018.

- International Longevity Centre. Commission on hearing loss: Final report. London (UK): International Longevity Centre; 2014.

- Greengross S. Commission on hearing loss: final report. London (UK): International Longevity Centre. 2014; p.1–38.

- Granberg S, Gustafsson J. Key findings about hearing loss in the working-life: a scoping review from a well-being perspective. Int J Audiol. 2021;60(supp2):60–11.

- Yoder S, Pratt S. Audiologists who have hearing loss: demographics and specific accommodations needs. J Acad Rehabilit Audiol. 2005;38:11–29.

- Kramer SE. Hearing impairment, work, and vocational enablement. Int J Audiol. 2008;47:S124–S30.

- Backenroth GA, Ahlner BH. Hearing loss in working life-some aspects of audiological rehabilitation. Int J Rehabil Res. 1998;21(3):331–334.

- Punch R. Employment and adults who are deaf or hard of hearing: current status and experiences of barriers, accommodations, and stress in the workplace. Am Ann Deaf. 2016;161(3):384–397.

- Trotter AR, Matt SB, Wojnar D. Communication strategies and accommodations utilized by health care providers with hearing loss: A pilot study. 2014.

- Shaw L, Jennings MB, Poost-Foroosh L, et al. Innovations in workplace accessibility and accommodation for persons with hearing loss: using social networking and community of practice theory to promote knowledge exchange and change. Work. 2013;46(2):221–229.

- Arrowsmith L. Managing hearing loss when seeking or in employment. London: Action of Hearing Loss; 2016.

- Shaw L, Tetlaff B, Jennings MB, et al. The standpoint of persons with hearing loss on work disparities and workplace accommodations. Work. 2013;46(2):193–204.

- Glasgow RE. What does it mean to be pragmatic? Pragmatic methods, measures, and models to facilitate research translation. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(3):257–265.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London; Sage; 2013.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London; Sage; 2006.

- Dey I. Qualitative research. A user-friendly guide for social scientists. London, NewYork; Routledge, 1993.

- Campbell JL, Quincy C, Osserman J, et al. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol Method Res. 2013;42(3):294–320.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hearing loss in adults: assessment and management (NICE Guideline 98). 2018 [cited 2021 Nov 10]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng98

- BSA. Common principles of rehabilitation for adults in audiology services. Practice Guidance. Bathgate: British Society of Audiology; 2016.

- Grenness C, Hickson L, Laplante-Levesque A, et al. Patient-centred care: a review for rehabilitative audiologists. Int J Audiol. 2014;53(Suppl 1):S60–S7.

- Grenness C, Hickson L, Laplante-Levesque A, et al. Patient-centred audiological rehabilitation: perspectives of older adults who own hearing aids. Int J Audiol. 2014;53:S68–S75.

- Woolf K, Cave J, McManus IC, et al. It gives you an understanding you can't get from any book. The relationship between medical students' and doctors' personal illness experiences and their performance: a qualitative and quantitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7(1):1–8.

- Mallory TH. Lessons from the other side of the knife. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(3 Suppl 1):2–4.

- NHS Improvement. Pushing the boundaries: Evidence to support the delivery of good practice in audiology. London (UK): NHS Improvement, 2010.

- Henwood F, Wyatt S, Hart A, et al. 'Ignorance is bliss sometimes': constraints on the emergence of the 'informed patient' in the changing landscapes of health information. Sociol Health Illn. 2003;25(6):589–607.

- Neal RD, Hussain-Gambles M, Allgar VL, et al. Reasons for and consequences of missed appointments in general practice in the UK: questionnaire survey and prospective review of medical records. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6(1):47–46.

- Wallhagen MI. The stigma of hearing loss. Gerontologist. 2010;50(1):66–75.

- Kirkwood DH. Thinking positively about ‘09. Hear J. 2008;61(12):4.

- Maidment DW, Barker AB, Xia J, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the effectiveness of alternative listening devices to conventional hearing aids in adults with hearing loss. Int J Audiol. 2018;57(10):721–729.

- Coleman CK, Muñoz K, Ong CW, et al. Opportunities for audiologists’ to use patient-centered communication during hearing device monitoring encounters. Semin Hear. 2018;39(1):32–43.

- Graaf R, Bijl RV. Geestelijke gezondheid van doven: psychische problematiek en zorggebruik van dove en ernstig slechthorende volwassenen. Netherlands: Trimbos-Instituut; 1998.

- Muñoz K, Ong CW, Borrie SA, et al. Audiologists' communication behaviour during hearing device management appointments. Int J Audiol. 2017;56(5):328–336.

- Miller WR. Qualitative research findings as evidence: utility in nursing practice. Clin Nurse Spec. 2010;24(4):191–193.

- Sandelowski M. "To be of use": enhancing the utility of qualitative research. Nurs Outlook. 1997;45(3):125–132.