Abstract

Purpose

Long-term needs of stroke survivors (especially psychosocial needs and stroke prevention) are not adequately addressed. Self-management programmes exist but the optimal content and delivery approach is unclear. We aim to describe the process undertook to develop a structured self-management programme to address these unmet needs.

Materials and methods

Based on the Medical Research Council framework for complex interventions, the development involved three phases: “Exploring the idea”: Evidence synthesis and patient and public involvement (PPI) with stroke survivors, carers and healthcare professionals. “The iterative phase”: Development and iterative refinement of the format, content, underpinning theories and philosophy of the self-management programme My Life After Stroke (MLAS), with PPI. MLAS consists of two individual appointments and four group sessions over nine weeks, delivered interactively by two trained facilitators. It aims to build independence, confidence and hope and focusses on stroke prevention, maximising physical potential, social support and managing emotional responses. MLAS is grounded in the narrative approach and social learning theory. “Ready for research”: The refinement of a facilitator curriculum and participant resources to support programme delivery.

Results

Through a systematic process, we developed an evidence- and theory-based self-management programme for stroke survivors

Conclusions

MLAS warrants evaluation in a feasibility study.

My Life After Stroke(MLAS) has been developed using a systematic process, to address the unmet needs of stroke survivors.

This systematic process, involved utilising evidence, theories, patient and public involvement, expertise and guidelines from other long-term conditions. This may further help the development of similar self-management programme within the field of stroke.

MLAS warrants further evaluation within a feasibility study.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

The longer term problems experienced by people with stroke and their carers are well recognized [Citation1,Citation2]. A UK survey found that stroke survivors wanted more information about stroke and support for the emotional and social impact of stroke, as well as highlighting the many physical and cognitive challenges people face post-stroke (such as memory, concentration problems, and fatigue) [Citation1]. Psychosocial consequences following stroke can have a significant impact on quality of life and long-term functioning [Citation3,Citation4] and there is now a greater recognition and drive to improve people’s mental health and well-being [Citation5,Citation6]. Providing further information and strategies for stroke prevention are also crucial, as over a quarter of stroke survivors are likely to have another stroke within 5 years and up to 40% at 10 years [Citation7].

Many stroke services are tailored to stroke survivor needs during the acute period, with long-term support currently consisting of a recommended 6 month follow up and subsequent annual reviews within primary care [Citation8]. While these reviews are recommended and patients should be able to be referred back into appropriate services (such as physiotherapy or psychology) as needs arise [Citation9], there is a disparity in terms of provision and stroke survivors and carers feel abandoned [Citation10]. Furthermore, psychosocial needs increase over time, compared to functional needs which decrease over time, highlighting an additional need for the provision of appropriate services over a longer period of time [Citation11].

Self-management programmes (SMPs) in other long-term conditions have demonstrated benefits both in trials as well as implementation [Citation12,Citation13]. Within stroke, the content and format of self-management programmes varies widely [Citation14–16]. There is evidence to support many self-management strategies, especially in relation to behaviour change, self-efficacy and goal-setting [Citation15,Citation17], but there are no agreed criteria for what a self-management programme should include within stroke. In diabetes, for example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance advises self-management programmes are tailored to the needs of the individual. Diabetes SMPs are developed with a specific aim to support the person to self-manage their condition. These SMPs are often accompanied by a structured curriculum that is theory-driven and evidence-based, are delivered by trained facilitators and are quality assured and audited regularly [Citation18]. While diabetes and stroke are different diseases, both are long-term conditions which require self-management. With this in mind, our aim was to:

Develop an evidence-based, theory-driven, structured self-management programme for stroke survivors to address their unmet psychosocial and information needs about stroke and stroke management.

Methods and findings

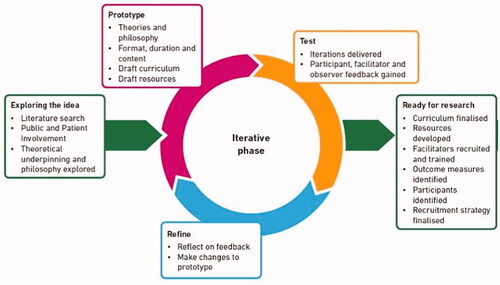

The development of the My Life After Stroke (MLAS) programme followed a systematic, iterative process, based on the Medical Research Council framework [Citation19,Citation20] for the development of complex interventions and our in-house pathway and experience for developing SMPs [Citation21–23]. Key aspects of this process are detailed within the phases detailed below and summarised in . The core development team included psychologists, nurses and a physiotherapist, alongside a research team. In addition to the expertise in their area, our development team had previous experience in developing and delivering self-management programmes in other long-term conditions [Citation20,Citation24,Citation25] and were well-placed to develop, review, progress and refine this intervention through the process detailed below.

Figure 1. Key steps in the development process of the self-management programme.

Phase 1 “exploring the idea”

Literature search

In this phase, a comprehensive literature search was undertaken to identify research of self-management interventions for stroke survivors in order to pragmatically inform the development of our intervention. It was also carried out to check if there was an existing effective intervention that could be used or adapted in order to meet stroke survivors’ needs. The search included studies from 2005 to 2015 and was limited to pilot studies, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews of RCTs, in English (Supplementary Appendix 1 for search terms used). These studies were considered in terms of their sample, details of intervention, primary outcomes and theoretical underpinning, where relevant.

The literature review identified 25 RCTs and 6 systematic reviews relevant to the aims of this study. Interventions were delivered individually face-to-face (n = 11), group-based (n = 7), via telephone (n = 3), online (n = 2) or as a workbook (n = 2). Not all interventions recorded a theoretical underpinning, however, theories that were cited included self-efficacy (n = 5), implementation of intentions (n = 2), stress and coping (n = 2), adult learning theory (n = 2) and chronic disease self-management (n = 2). Topics across the identified interventions included: understanding stroke (recovery, re-occurrence, medication, prevention), practical advice, managing emotions and behaviours, health behaviour change (promotion of health lifestyle), dealing with stress and fatigue and future focus. Resources used within the interventions included personalised manual/workbook, written tip sheets, card tasks (to identify goals), prevention package, risk factor profiles, keeping well plan, fatigue diary and problem rating sheets. Outcome measures used in studies included measuring quality of life, mental health status, knowledge, self-efficacy and fatigue. Some used general health measures and others, stroke-specific ones. As illustrated in , a number of important considerations emerged from the literature, which informed our SMP.

Table 1. Findings from the literature and how this was used to inform our self-management programme.

The findings from the literature search were discussed by the development team. In addition to the theories generated in the search, further theories [Citation32,Citation33] were identified as relevant through experience within the core development team. The patient-centred empowerment model [Citation34,Citation35] was also highlighted based on the research team’s previous work [Citation12]. Stroke survivors live with the effects of their stroke every minute of every day, yet only access healthcare providers for a limited period of time, therefore empowering patients to make decisions about what is important for them, their health and their life is important to support self-management.

Patient and public involvement (PPI)

Consultation workshops (n = 2) were held with stroke healthcare professionals (HCPs) and stroke survivor groups (n = 3) separately, to identify each group’s perspective on stroke survivor needs, the timing and format of a stroke SMP as well as priorities for content. Each workshop lasted approximately an hour, followed a topic guide (examples provided in Supplementary Appendix 2) and was run by 2 members of the research team; one took the lead for asking questions and facilitating the discussion and the other made notes and asked clarifying questions where necessary. HCPs included 2 physiotherapists, 2 nurses, 1 occupational therapist, 1 speech and language therapist, 1 support worker and 2 consultants. Three separate stroke survivor groups of between 4-8 people (including carers) were consulted across Leicester and Cambridge across the duration of the development process. Members of the research team also had informal discussions with the regional Stroke Association manager, Stroke Association group leader and the Early Supported Discharge Stroke manager.

Once a PPI event had taken place, a de-brief immediately occurred between those running the event; their initial thoughts were documented and important themes were highlighted. These were then fed back and discussed with the wider research development team and triangulated alongside evidence from the literature search to iteratively inform and make decisions in relation to the development of our intervention. Topic guides were amended for subsequent consultation workshops, to further discuss, refine or clarify issues.

Consultation with stroke HCPs highlighted priority areas for the SMP. One priority included emotional needs and practical strategies to manage low mood. Furthermore, HCPs thought facilitators who would be delivering the SMP would need support and training in this. A second priority included prevention strategies of further strokes, which HCPs believed would be most beneficial if offered after the initial six weeks post-stroke. The rationale for this was that stroke survivors would be better able to process this information once the therapy-intense period had occurred. A third priority was to provide ongoing support and education to aid stroke survivors’ recovery, adjustment and adaptation. Again, this would optimally be offered after the acute phase as stroke survivors can feel abandoned as intensive therapy reduces, therefore follow-on support is needed to help this transition. Fourthly, an introductory individual appointment prior to attending group sessions was suggested to help prepare individuals for the SMP, as well as enhancing uptake to the programme. HCPs advised there should be opportunities for stroke survivors to consolidate their understanding throughout the SMP as well as facilitators using simple language and short sentences, to accommodate for memory and other cognitive changes people can have following stroke. It was acknowledged that challenges may exist in offering a SMP suitable for all stroke survivors who are at different stages with varying disabilities and effects (e.g., catering for physical disabilities as well as cognitive and speech problems).

Our PPI work with stroke survivors and carers also recommended an individual appointment at the start of the SMP. They stressed the importance of the programme to be held in an accessible, community venue and to include a focus on emotional management and building confidence. Stroke survivors supported the suggestion of the programme consisting of 4-5 group sessions and while the duration of each session was not a concern to them, they did prefer sessions to be in the morning, due to the risk of fatigue experienced later in the day. PPI members liked the idea of the narrative approach, journey metaphor and the identified core areas for content (see below), although disagreements about including the topic “what is a stroke” were aired, due to PPI members’ differing personal understanding of stroke. The philosophy of our SMP was developed further through exercises within PPI groups, using hypothesised scenarios of stroke survivors (theories and philosophy are described in detail in phase 2). In addition to providing feedback on the content of the SMP, stroke survivor and carer PPI members decided the name of our SMP: “My Life After Stroke” (MLAS). From this point onwards, we will refer to our SMP as MLAS.

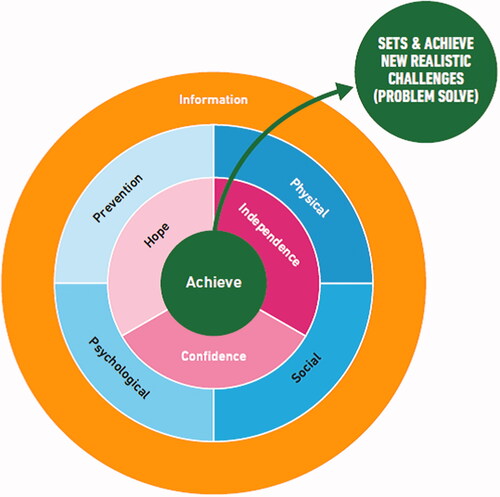

Figure 2. The aim and core focus of the MLAS programme.

Phase 2 “the iterative phase”

Prototype

Based upon the work from Phase 1, a prototype SMP was developed.

Philosophy

The philosophy underpinning MLAS is patient-centred and one of empowerment. More specifically, people who have had a stroke seek to maximise their well-being and quality of life which is achieved across four areas: social well-being and integration; acquiring a level of understanding of, and capacity to manage, their emotional responses to living with a stroke; maximise own physical potential (including cognitive and sensory abilities); minimising risk of future stroke.

Theories

The theoretical basis to MLAS was grounded within a narrative approach due to the focus on social and psychological elements of living post-stroke and to accommodate a potential broad range of time since first stroke. This would allow participants to discuss what life was like before and after stroke and become more aware of their journey with stroke [Citation32,Citation33].

Another important theory was Social Learning Theory and a main construct of this is self-efficacy. Self-efficacy [Citation36] is key to supporting behaviour change, confidence, independence and overcoming barriers. The format and content of MLAS provide the opportunity for people to share mastery experiences and vicariously learn from, support and motivate, each other. A cognitive behavioural therapy approach was also employed to help people consider how their thoughts, emotions, physiological responses and behaviour interlink, with the aim of participants considering barriers (and subsequently solutions) to achieving physical, social and psychological well-being. In relation to stroke prevention, the capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour (COM-B) model was consulted to inform and identify techniques to support relevant behaviour change [Citation37,Citation38]. Furthermore, activities within MLAS allows participants to set goals, action plan, problem solve and self-monitor [Citation39], with the support of facilitators. A detailed breakdown of how these theories underpinned the MLAS sessions are shown in .

Table 2. Topics and corresponding theories and strategies to support the programme aims within each session of MLAS.

Prototype

Aim

From the work detailed above, the aims of MLAS were to help participants to:

Achieve – assist participants to acknowledge and adjust to the new realities of their situation, (including emotional responses) and set themselves new and realistic challenges (including reducing their risk of further stroke).

Build hope, independence and confidence – increase their confidence in their abilities and skills to take on new challenges, encourage participants to feel hopeful that they can achieve the aims they set themselves and build independence to live their life.

In order to support stroke survivors to achieve these aims, content was included across four core topic areas: prevention, psychological, physical and social needs. Through group sessions, facilitation and interactivity, the provision and sharing of information underpins this content. As such, an overall conceptual map was developed ().

Facilitator behaviours

In order to achieve the aims of MLAS using the identified philosophy and theories, the facilitator’s role while delivering our SMP was to:

Demonstrate a curious, non-judgemental approach towards participants.

Skilfully support participants to explore their personal thoughts and feelings.

Avoid giving specific advice and instead support participants to develop their own solutions and strategies to the problems they face.

Facilitate the group’s awareness of sources of support and information.

Promote the sharing of knowledge and ideas between the participants and signpost where appropriate.

Format and content

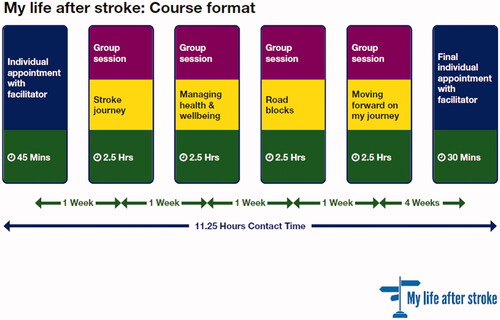

Through the above work, the SMP format and topics were established. The MLAS programme consists of one 30–45 min one-to-one individual appointment, 4 weekly group sessions of 2.5 h each and a final 30 min one-to-one individual appointment 4 weeks after the final group session (). describes the content across all sessions as well as highlighting the corresponding theory, approach or supportive tool. Carers were also invited to attend if the stroke survivor wished.

Figure 3. Format of the MLAS programme.

Draft curriculum and resources

A curriculum detailing session plans and associated supportive resources were drafted, to support facilitator delivery. Handouts were also created and provided for participants which included an action plan, worksheets to use within sessions and information regarding how to reduce risk for further strokes. Participants could then also refer back to these handouts after sessions, to help them achieve their goals.

Test & refine

MLAS was tested in two iterative cycles; iteration one enlisted volunteers (10 stroke survivors and 4 carers) from an existing stroke support group in the community and iteration two was delivered to six stroke survivors and three carers who volunteered from contacts within the research development team or wider support groups. Participants remained within the same cohort, to encourage building relationships and support.

Two members of the development team (both HCPs with previous experience of SMP delivery) facilitated each session of the programme (with the same two facilitators for each cohort where possible), with an observer making notes. After each iterative session, feedback was obtained from the group about what they felt went well, what didn’t go so well, what they would want to change and what they thought about the resources used. Observation notes were discussed within the development team and further amendments made to the draft curriculum plans where necessary. A feedback PPI group was held by a researcher not involved in the delivery at the end of each iteration programme, for participants to share their thoughts and insights on the programme and facilitators. The number of iterations and refinements were balanced between funding availability, feedback and consensus within the research development team.

Feedback

MLAS was well received, with minor amendments made to the content, resources and delivery. Some written activities were changed to a verbal format to accommodate communication needs and physical abilities of participants. Some resources were revised to use less technical language. There was a need to write key summary points, to aid those with memory problems. The narrative journey metaphor was further incorporated and referred to more often throughout MLAS to enhance participant engagement.

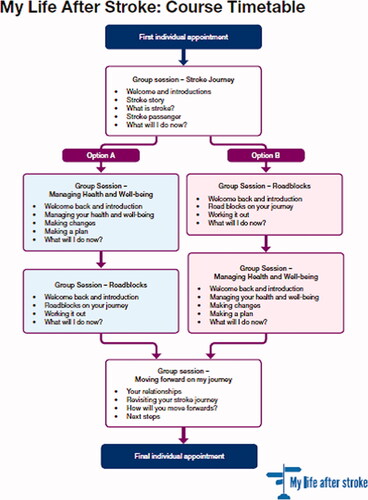

Feedback led to changes to the ordering and content of some sessions. For example, group sessions 2 and 3 were made interchangeable based on participants’ preference and an additional section about relationships was introduced to group session 4 ().

Figure 4. Timetable and content of sessions for MLAS following the iterations.

The initial individual appointment was perceived to be fundamental to an effective delivery of MLAS group sessions. This individual appointment allowed stroke survivors the time and freedom to detail their stroke (and often share their frustration of having had a stroke), and reflect on their experience before being able to embrace the MLAS programme. Therefore the first individual appointment was made compulsory (either face-to-face or via telephone) prior to attending the group sessions.

Phase 3 “ready for research”

Feedback from the iterative phase led to an amended version of MLAS, in which the resulting resources and curriculum were developed. An overview of the final timetable for MLAS can be seen in . A curriculum detailing key outcomes, content, facilitator behaviours, participant activities and resources to be used for each session, along with a session outline, example open questions and guidance was finalised. Resources, including a road map, action plan and photographic images of ways to manage health and well-being, were produced. Handbooks for participants for each group session were developed, utilising guidance [Citation40] to facilitate reading and understanding, which would be provided in the corresponding group session. This re-iterated information and also provided worksheets and opportunities for participants to write down useful information for themselves. A stroke directory of useful local and national services, groups and support available was also completed. This version would then be tested in a feasibility study with stroke survivors recruited from primary care [Citation41]. Now we had finalised the content, structure and theoretical underpinning of MLAS, the research development team looked more closely at potential outcomes measures we could use as part of the upcoming feasibility study. From the outcome measures identified as part of the literature search and wider investigation, we identified Stroke Self-Efficacy Questionnaire [Citation42], Stroke-Specific Quality Of Life Scale (SS-QOL) [Citation43], Stroke Impact Scale (SIS) [Citation44] and Southampton Stroke Self-Management Questionnaire (SSSMQ) [Citation45] as outcomes relevant to stroke survivors which the intervention might influence.

Discussion

This paper has described the systematic process that took place to develop MLAS, a self-management programme for stroke survivors. MLAS was supported by a comprehensive curriculum for facilitators to deliver MLAS as intended, as well as utilising various resources to help support participants through their journey with stroke. MLAS is underpinned by relevant content from the evidence base, the narrative approach and social learning theories, goal setting and action planning in order to support people to adjust, achieve and build hope, independence and confidence following stroke. The development of MLAS utilised stroke survivor input and feedback throughout.

A variety of self-management interventions for stroke survivors have been developed, which include face-to-face and telephone delivery, in individual and group formats. Collectively, they provide low-quality evidence that participants experience improvement in quality of life and self-efficacy [Citation16]. Characteristics of MLAS that differentiate it from previous programmes are its target population (longer-term stroke survivors and their carers, recruited from primary care) and being applicable for a UK health service. To our knowledge, MLAS is the only intervention that explicitly details the underpinning theories and philosophy of the programme and utilises a written curriculum, trained facilitators and a quality assurance process, which draws upon experience and guidelines in other long-term conditions [Citation12,Citation18].

During the first group session of the first iterative programme, participants focused on the emotional management aspects of stroke whereas during the second iteration, participants’ focus was towards stroke prevention. This may simply reflect the different needs of different participants. Alternatively, for the first iteration, participants were recruited from one stroke support group, where they often had guest speakers, so these participants may already have felt knowledgeable about stroke prevention. However, participants in the second iteration, were recruited from different sources and had not met before, so their experiences and knowledge may have been different (which may more accurately represent real-world where referrals are likely to be from different sources). Therefore, we enabled group sessions “Roadblocks” and “Managing Health and Well-being” to be interchangeable, so that the needs of the group inform the session order. At the end of the “Stroke Journey”, a consensus decision is made by the group, regarding which session is delivered next.

Input from healthcare professionals, stroke survivors and carers was vital within the development of MLAS, as guidelines recommend [Citation20]. Further feedback was sought from stroke survivors and carers during testing of the first iterative versions of MLAS. This helped to make MLAS as relevant, helpful and appropriate to as many stroke survivors as possible, taking into account the wide range of difficulties and disabilities stroke can cause.

It is appreciated that it may be difficult for stroke survivors to attend all six sessions due to other conflicting appointments or commitments. However, the individual appointment (preferably delivered face-to-face but could be achieved via telephone) and group session one were deemed mandatory for participants. This is because of the importance of allowing participants to share details of their stroke privately, for the facilitator to understand any adaptations the participant may need for the group sessions and for participants to understand the narrative approach and the journey metaphor, which is referred to throughout all MLAS sessions. It appeared extremely valuable for participants to detail their stroke during their individual appointment in order to allow them to move on. This may be because it was the first opportunity they had had to discuss this significant event; GP appointments tend to be a short and problem-focussed and therapy input tends to focus on a physical problem and goal. Conversely, MLAS provides an opportunity for participants to be listened to and enables them to reflect and problem-solve with appropriate support. However, for stroke survivors to go into great detail and description of their stroke can be disruptive and time-consuming within the group sessions, hence the importance of the first individual appointment.

A potential limitation of this work was that funding and time allowance meant we only carried out two iterations in order to refine MLAS. However, given the amount of PPI in developing MLAS, the positive feedback gained during the iterations and the limited modifications that were needed between the two iterations, this was probably adequate prior to a feasibility study. Most participants were White British so MLAS may need further adaptation for Black and Minority Ethnic stroke survivors. As the feasibility of MLAS is yet to be tested, additional costs for translation and cultural adaptation had not yet been considered. Given the patient-centred nature of MLAS, with patient’s sharing their own narrative and accessible information guidelines [Citation40] being followed, hopefully much of MLAS is translatable across different ethnicities and cultures. However further work, utilising culturally-relevant PPI may be needed after further evaluation of MLAS.

In conclusion, we have developed an evidence-based, theory-driven self-management programme for stroke survivors with the aim of addressing feelings of abandonment and providing self-management support later in their stroke journey. Feedback from MLAS was positive, with minimal amendments implemented. Further comprehensive evaluation is necessary to determine its acceptability and effectiveness; MLAS has subsequently been used as part of a feasibility and cluster randomised controlled trial within primary care [Citation46].

Ethical approval

Favourable ethical opinion was granted by the West Midlands, South Birmingham Research Ethics Committee on 23rd February 2017 (IRAS 213022).

appendix_2_Topic_guide_for_consultation_workshops.docx

Download MS Word (22.8 KB)Appendix_1_Search_strategy.docx

Download MS Word (210.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The MLAS development group involved a number of team members including Rosie Horne, Clare Makepeace, Lorraine Martin Stacey, Yvonne Doherty, Jayna Mistry as well as facilitators and PPI members who contributed to various aspects of study set up, trial management, intervention development, refinement and delivery for who we are thankful to.

Disclosure statement

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. VJ, LA, MC, EK, RM, JM, MJD are, or were, employed through their respective organisations during this work. Intellectual property rights are held through the University of Leicester on behalf of the DESMOND collaborative at Leicester Diabetes Centre.

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- McKevitt C, Fudge N, Redfern J, et al. Self-reported long-term needs after stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1398–1403.

- Department of Health. Cardiovascular disease outcomes strategy: improving outcomes for people with or at risk of cardiovascular disease; 2013. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/217118/9387-2900853-CVD-Outcomes_web1.pdf

- Kirkevold M, Bronken BA, Martinsen R, et al. Promoting psychosocial well-being following a stroke: developing a theoretically and empirically sound complex intervention. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(4):386–397.

- Kirkevold M, Martinsen R, Bronken BA, et al. Promoting psychosocial wellbeing following stroke using narratives and guided self-determination: a feasibility study. BMC Psychol. 2014;2(1):4.

- Department of Health. No health without mental health; 2011. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213761/dh_124058.pdf

- Improvement NHS. Psychological care after stroke: improving stroke services for people with cognitive and mood disorders; 2011. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2017/11/Psychological-Care-after-Stroke.pdf

- Mohan KM, Wolfe CD, Rudd AG, et al. Risk and cumulative risk of stroke recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1489–1494.

- NICE. Stroke in adults; quality standard; 2010. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs2

- Stroke Assocation. State of the nation: stroke statistics; 2017. Available from: https://www.mynewsdesk.com/uk/stroke-association/documents/state-of-the-nation-2017-68765

- Pindus DM, Mullis R, Lim L, et al. Stroke survivors' and informal caregivers' experiences of primary care and community healthcare services – a systematic review and meta-ethnography. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192533.

- Taylor SJC, Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, et al. Health services and delivery research. A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions: PRISMS – practical systematic review of self-management support for long-term conditions. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2014.

- Davies MJ, Heller S, Skinner TC, Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed Collaborative, et al. Effectiveness of the diabetes education and self-management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;336(7642):491–495.

- Skinner TC, Carey ME, Cradock S, DESMOND Collaborative, et al. Diabetes education and Self-Management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND): process modelling of pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64(1–3):369–377.

- Lennon S, McKenna S, Jones F. Self-management programmes for people post stroke: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(10):867–878.

- Warner G, Packer T, Villeneuve M, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of stroke self-management programs for improving function and participation outcomes: self-management programs for stroke survivors. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(23):2141–2163.

- Fryer CE, Luker JA, McDonnell MN, Cochrane Stroke Group, et al. Self management programmes for quality of life in people with stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(8):CD010442.

- de Silva D. Evidence: helping people to help themselves. London: The Health Foundation; 2011.

- NICE. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management (NG28). 2015. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28/resources/type-2-diabetes-in-adults-management-1837338615493

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Medical Research Council Guidance, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

- Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000;321(7262):694–696.

- Troughton J, Chatterjee S, Hill SE, et al. Development of a lifestyle intervention using the MRC framework for diabetes prevention in people with impaired glucose regulation. J Public Health. 2016;38(3):493–501.

- Stone M, Patel N, Daly H, et al. Using qualitative research methods to inform the development of a modified version of a patient education module for non-English speakers with type 2 diabetes: experience from an action research project in two South Asian populations in the UK. Diver Health Social Care. 2008;5:199–206.

- Carey M, Daly H. Developing and piloting a structured, stepped approach to patient education. Prof Nurse. 2004;20(2):37–39.

- Smith J, Forster A, Young J. A randomized trial to evaluate an education programme for patients and carers after stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18(7):726–736.

- Apps LD, Mitchell KE, Harrison SL, et al. The development and pilot testing of the self-management programme of activity, coping and education for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (SPACE for COPD). Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:317–327.

- Cheng HY, Chair SY, Chau JP. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for stroke family caregivers and stroke survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(1):30–44.

- Pfeiffer K, Beische D, Hautzinger M, et al. Telephone-based problem-solving intervention for family caregivers of stroke survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(4):628–643.

- Marsden D, Quinn R, Pond N, et al. A multidisciplinary group programme in rural settings for community-dwelling chronic stroke survivors and their carers: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24(4):328–341.

- Sabariego C, Barrera AE, Neubert S, et al. Evaluation of an ICF-based patient education programme for stroke patients: a randomized, single-blinded, controlled, multicentre trial of the effects on self-efficacy, life satisfaction and functioning. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18(4):707–728.

- Cadilhac DA, Hoffmann S, Kilkenny M, et al. A phase II multicentered, single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of the stroke self-management program. Stroke. 2011;42(6):1673–1679.

- Jones F, Mandy A, Partridge C. Changing self-efficacy in individuals following a first time stroke: preliminary study of a novel self-management intervention. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(6):522–533.

- Chow EO. Narrative therapy an evaluated intervention to improve stroke survivors' social and emotional adaptation. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29(4):315–326.

- Chow EO. Responding to lives after stroke: Stroke survivors and caregivers going on narrative journeys. International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work. 2013;(4):38–44. Available from: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.813946639021165

- Anderson RM, Funnell MM. Patient empowerment: myths and misconceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(3):277–282.

- Funnell MM, Anderson RM. Empowerment and self-management of diabetes. Clinical Diabetes. 2004;22(3):123–127.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215.

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42.

- Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

- NICE. Behaviour change: individual approaches (PH49); 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph49

- Stroke Association. Accessible information guidelines. London: Stroke Association; 2012.

- Johnson VL, Apps L, Kreit E, et al. The feasibility of a self-management programme (My Life After Stroke; MLAS) for stroke survivors. Disabil Rehabil. 2022. DOI:10.1080/09638288.2022.2029960

- Jones F, Partridge C, Reid F. The stroke self-efficacy questionnaire: measuring individual confidence in functional performance after stroke. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(7b):244–252.

- Williams LS, Weinberger M, Harris LE, et al. Development of a stroke-specific quality of life scale. Stroke. 1999;30(7):1362–1369.

- Duncan PW, Bode RK, Min Lai S, et al. Rasch analysis of a new stroke-specific outcome scale: the stroke impact scale11No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit upon the author(s) or upon any organization with which the author(s) is/are associated. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2003;84(7):950–963.

- Boger EJ, Hankins M, Demain SH, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of a new patient-reported outcome measure for stroke self -management: the Southampton stroke self-management questionnaire (SSSMQ). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:165–165.

- Mullis R, Aquino MRJ, Dawson SN, IPCAS Investigator Team, et al. Improving primary care after stroke (IPCAS) trial: protocol of a randomised controlled trial to evaluate a novel model of care for stroke survivors living in the community. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e030285.