Abstract

Purpose

To investigate perspectives of multiple stakeholders involved in development and delivery of Vietnam’s first speech-language pathology degrees and derive recommendations for future degrees in Vietnam and other Majority World countries.

Methods

An exploratory-descriptive qualitative research design using focus groups and individual semi-structured interviews in the preferred language (English or Vietnamese) was used, with 70 participants from five stakeholder groups: project managers, students, academic educators, placement supervisors and interpreters. Transcriptions were analysed using thematic network analysis.

Results

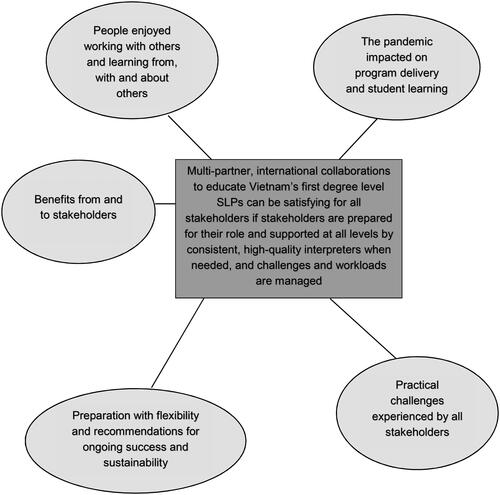

Analysis identified five organising themes: (1) People enjoyed working with/learning from others; (2) Benefits from/to stakeholders; (3) The pandemic impacted program delivery and learning; (4) Practical challenges; (5) Preparation with flexibility required for success and sustainability. From the five organising themes, one synthesising global theme was developed, conveying that satisfying international collaborations require preparation, support, high quality interpreting, and management of challenges.

Conclusions

Recommendations highlight the need for preparation, collaboration, support to manage challenges, flexibility, recognition for placement supervisors and high-quality interpreting. The recommendations are of relevance to other organisations engaged in development of professional degrees in Majority World countries. Future research would benefit from a critical investigation of the diverse perspectives of stakeholders involved in the development and implementation of international curricula.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Many Majority World countries are seeking to develop university degrees to build a workforce of speech-language pathologists to provide services to people with communication and swallowing disabilities

Collaborative relationships, flexibility, and delineation of roles and commitments are vital to partnership success

Conceptualisation of rehabilitation services in cross-cultural contexts must privilege the knowledge, experiences and preferences of local partners

Local capacity building will support training programs and rehabilitation services that are sustainable and culturally relevant.

Introduction

In many countries, speech-language pathologistsFootnote1 (SLPs) are a key part of the rehabilitation workforce for people experiencing communication and swallowing disabilities (CSwD). In Vietnam, until recently communication and swallowing services have been delivered by local community-based rehabilitation (CBR) workers [Citation1], rehabilitation technicians or rehabilitation doctors with none or only short course training in communication and swallowing, and by expatriate volunteers as part of surgical teams and NGOs working in Vietnam [Citation2–4]). Since 2010, a small number of one- or two- year certificate-level SLPs have been trained within one Vietnamese university. In its National Plan of Rehabilitation Development 2014–2020 [Citation5], the Vietnam Ministry of Health outlined an extensive expansion of rehabilitation services that included development of fully qualified, degree level SLPs. To achieve this goal, the Vietnamese government requested international support and collaboration. This paper describes the development and delivery of Vietnam’s first speech-language pathology degrees and presents the findings of a comprehensive evaluation involving all stakeholders involved in development, management and delivery of the degrees. Implications and recommendations for future degrees in Vietnam as well as other countries and agencies considering or engaged in development of similar degrees in other Majority WorldFootnote2 countries are presented.

Background

The World Report on Disability (WRD) [Citation8] noted that 15% of the world’s population experience some form of disability, however prevalence figures for people experiencing CSwD are unknown. Estimates from Minority World countries range from 1-37% [Citation9]; Australia for example estimated around 5% [Citation10]. Data for the incidence and prevalence of CSwD in Majority World countries is generally not available, mostly due to the capacity of different regions to collect data, and differences in how disability is defined, measured, and perceived [Citation11].

In many Majority World countries, there is limited access to SLPs, principally due to lack of a speech-language pathology workforce, or where one exists, access is restricted by service costs, geography, transport limitations and poor community awareness of the profession [Citation12,Citation13]. Different approaches to building a speech-language pathology workforce in Majority World countries have been described (see for example the 2013 International Journal of Speech Language Pathology Special Issue on responses to the WRD [Citation14] and the Handbook on Speech and Language Therapy in sub-Saharan Africa [Citation15].

There are known issues with the development of speech-language pathology training courses in Majority World countries including reliance on short term volunteers, issues of sustainability, “cultural appropriateness” [Citation16,Citation17], and risks of neo-colonialism [Citation18] in curriculum conceptualisation, development and delivery. Further, these courses often originate within medical models of practice that focus on hospital-based practice, rather than a more population-based approach [Citation19], or public health approach as recommended by Wylie et al. [Citation13], and may not use a biopsychosocial model such as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [Citation20].

The context in Vietnam

In 2016, the Vietnamese government completed its first ever large-scale national survey to identify people experiencing disabilities [Citation21]. An estimated 7.1% of a population of 92 million people were identified as living with some form of disability, though this figure is likely higher due to the limited reach of the survey. Of note, 7.8% of children and adults reported experiencing disabilities in more than one of the domains of hearing, cognition, psychosocial functioning, and communication. Reports from two of Vietnam’s biggest hospitals – Cho Ray Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) and Bach Mai Hospital in Hanoi indicated that about 200 000 people were treated for stroke every year, comprising 2.5% of hospital admissions [Citation2]. Many of these people will experience CSwD. Vietnam has long recognised the need to provide services for people experiencing disability, through training of traditional medicine practitioners, rehabilitation doctors and rehabilitation technicians, and through implementation of an extensive CBR program [Citation22]. However, this training typically lacks a specific focus on the needs of people experiencing CSwD [Citation23].

History of the speech-language pathology profession in Vietnam

Professions and professionalisation cannot be understood outside of the social-political environment in which they are embedded [Citation18]. Therefore, given the long history of colonisation in Vietnam (by the Chinese, French and later the influence of the American war), it is inevitable that outsider influences impact upon the development of the speech-language pathology profession. Accounts in the English-language literature of the speech-language pathology profession in Vietnam date from where volunteer internationally-trained SLPs travelled to Vietnam to provide services and train local health professionals in aspects of speech-language pathology [Citation24]. By the 1990s, Vietnamese doctors, nurses and physiotherapists had commenced providing speech-language pathology services as part of their daily work [Citation3]. In more recent times, training courses of between 3 - 24 months have been offered in specific aspects of speech-language pathology and as part of university degrees in rehabilitation [Citation2]. A 2016 needs assessment for the US Agency for International Development (USAID) [Citation2] found that speech-language pathology services available in hospitals were largely directed to supporting people with cleft lip/palate after surgeries, and to people experiencing vocal misuse, head and neck cancer and various neurological conditions. There were some services developing for people experiencing CSwD after stroke, and for children with developmental disabilities. Special education teachers who had received short course training about communication disabilities from special education colleges and universities throughout Vietnam were also providing services for children with complex disabilities [Citation25]. However, in general, support for people experiencing CSwD was found to be severely limited. Recent research ([Citation26] in preparation) revealed that people in Vietnam with family members experiencing communication and swallowing disabilities seek help from the limited number of SLPs and doctors with expertise in this area, not from traditional medicine sectors. This growing demand for SLP services was one factor driving development of a speech language pathology workforce in Vietnam.

Development of a speech-language pathology workforce in Vietnam

To achieve its goal of developing a university qualified speech-language pathology workforce as outlined in its National Development Plan of Rehabilitation Development 2014-2020 [Citation5], Vietnam sought assistance from international donors. USAID conducted a needs assessment [Citation2] and subsequently provided VietHealth with funding for a 5-year project to develop and deliver government approved speech-language pathology degrees. This funding was administered by the Medical Committee of Netherlands Vietnam (MCNV), a Hanoi based NGO. To obtain speech-language pathology expertise in curriculum design and delivery, a collaborative partnership between Trinh Foundation Australia (TFA), an NGO supporting universities and service providers in Vietnam, Vietnamese universities which would host the degrees and selected international universities, recognised through multi-lateral MOUs, was viewed as a solution. TFA has a 15 year history of responding to requests from Vietnamese universities and service providers to develop speech-language pathology education and services, and was able to obtain the technical expertise requested to develop curricula frameworks, source volunteer international lecturers requested to develop and teach relevant subjects, and source volunteers requested to supervise students’ clinical placements in Vietnam. MCNV managed all government and university liaison, paperwork for the various ministries, budgeting, and the day to day running of the project. The project was designed with the primary aim to develop the capacity of Vietnamese lecturers to deliver future speech-language pathology Bachelor level degrees in four medical universities (University of Medicine and Pharmacy (UMP) HCMC; Hue University of Medicine and Pharmacy; Da Nang University of Medical Technology and Pharmacy (DUMTP); Hai Duong University of Medical Technology) by offering a Master level degree in speech-language pathology at UMP. While both Master and Bachelor graduates in Vietnam are eligible to provide services to people with CSwD in the workplace, only Master graduates may teach in universities. The intention was that Master graduates would continue to develop and deliver Bachelor degrees across Vietnam and support the first generation of Vietnamese SLPs to provide services across the full scope of speech-language pathology practice. A second aim was to develop and pilot a Bachelor degree curriculum at DUMTP for later roll out to other universities.

Development, structure and delivery of speech-language pathology curricula

The project commenced in 2017 with a series of consultation workshops with representatives from Vietnamese government ministries of Health and Education and major hospitals and medical universities. A technical consultant provided information on and facilitated discussion about global models of education and possible scopes of practice from both Majority and Minority World countries. Vietnamese stakeholders clarified what they wanted and what was achievable for Vietnam at this stage in the journey of developing culturally and linguistically appropriate speech-language pathology services and education. Attendees clearly stated their desire for development of a scope of practice and national curricula that aligned with Minority World standards for education and practice (for example [Citation27]). To avoid neo-colonialism in telling Vietnamese colleagues “what was best for them” and to continue respectful engagement, the technical consultant worked with attendees to develop curricula frameworks and desired learning outcomes to be addressed in a 4-year Bachelor degree and a 2-year Master degree, which met their aspirations, and to benchmark these against international standards. Once agreement was achieved amongst the Vietnamese stakeholders in the project, academics from partnering universities commenced writing speech-language pathology subjects. Both degrees contained foundational content taught by Vietnamese academics on Ho Chi Minh philosophy, developmental psychology, Vietnamese phonetics and linguistics, anatomy and physiology, research methods, and ethics.

Perhaps because the degrees were sitting in medical schools, the curricula were not closely aligned with public health approaches to speech-language pathology education recommended by Wylie et al. [Citation13]; however, the ICF [Citation20] and the biopsychosocial model were adopted as key curricula threads, and the curricula explicitly included content on public health approaches, determinants of health and disability, and the education of others (e.g., carers, teachers, families). At the request of the Vietnamese ministries and universities, speech-language pathology subjects in the initial iteration of the degrees were led by international SLPs, with Vietnamese experts where possible, and addressed the full scope of speech-language pathology practice across the life span, with an emphasis on case-based learning and practical skills development. All content was delivered in Vietnamese, with spoken interpretation and translation of study materials provided in English when subjects were led by English-speaking academics. Both degrees included six clinical placements of 2–9 weeks duration, co-supervised by local Vietnamese and international SLPs. The Master students completed a research thesis co-supervised by international SLPs and UMP staff in the nursing and medicine faculties. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, long-term volunteers were placed in Vietnam by the Australian government to help build local capacity to teach and coordinate the degrees. Technical consultants provided support remotely throughout the project.

The Bachelor degree commenced in September 2019 with 20 students, and the Master degree with 14 students (junior doctors and physiotherapists) commenced in November 2019. The COVID-19 pandemic interrupted teaching in both degrees and required a rapid transition to online learning that included tele-placements with and without tele-supervision, and online cased-based learning and assessment. Further information about the impact of and adjustments made in response to the pandemic is provided in an earlier paper [Citation28].

Need for evaluation of the project

While the literature contains descriptions of new speech-language pathology programs in Majority World countries - see for example [Citation29–31], there are few rigorous evaluations of such programs. The funder of the project required a comprehensive evaluation of the outcomes for quality assurance and improvement purpose. There was no funder or Vietnamese government involvement in the design, conduct or analysis of the evaluation.

Research aims

The research aims were to investigate:

the experiences of stakeholders in development and delivery of Vietnam’s first speech-language pathology degrees;

stakeholder recommendations for the degrees going forward.

It was anticipated that findings and implications would support future speech-language pathology programs in Vietnam and offer insights and recommendations to inform the development of speech-language pathology programs in other Majority World contexts. This paper reports on the qualitative component of the evaluation. The aim of this paper is to present a summary and synthesis of key findings from all stakeholder groups in the project. Subsequent papers will provide a more in-depth analysis of individual stakeholder data sets, using different lenses and a critical perspective. The research was approved by Charles Sturt University, Australia, Human Research Ethics Committee [Protocol H22032].

Methods

Situating the researchers and evaluation team

In qualitative research, the identities and positionalities of researchers are important as they speak to issues of power and are the instruments through which data is collected and analysed, and research findings constructed and represented [Citation32]. Six members of the research team who designed the program evaluation and analysis of data are white, English-speaking speech-language pathologists and academics living in a Minority World country. All are past or present TFA Board directors and have varying levels of experience in academia, local and international program development and evaluation, and in mixed methods research. Three of these researchers plus a fourth researcher who is Vietnamese, bilingual (Vietnamese/English) and living in Vietnam, were involved in the day-to-day management of the project (government and hospital liaison, curriculum design and delivery). Program data collection and analysis were led by two researchers with no prior involvement in the project - a bilingual (Vietnamese/English) academic residing in a Minority World country, who acted as participant recruiter and translator/interpreter of the data collection tools and interview transcripts; and a second researcher (English-speaking) who is an experienced SLP researcher residing in a Minority World country who conducted the first pass data analysis in order to reduce bias in analysis. A further bilingual (Vietnamese/English) Vietnamese researcher resided in Vietnam and had peripheral involvement in the program.

An exploratory-descriptive qualitative research design [Citation33] was adopted for this research. Qualitative research was selected for this research as it provides opportunities for highlighting the voices of marginalised communities and methods can be adapted to the needs of particular contexts or circumstances (as was necessary during the pandemic) [Citation34]. Exploratory-descriptive qualitative research has its origins in exploratory research [Citation35] and descriptive qualitative research [Citation36]. Consistent with this research design focus groups and individual semi-structured interviews were used for data collection, transcripts were transcribed and content analysis [Citation37] was used to analyse individual stakeholder data sets. Later, thematic network analysis [Citation38] was used to integrate and synthesise data across stakeholder data sets.

Data collection methods

Semi-structured individual interviews and focus groups were used with a total of 70 participants from five “information rich” stakeholder groups, including high level stakeholders, students, academic educators, placement supervisors and support staff (see ). All interviews and focus groups were conducted in the preferred language of the participants and via Zoom given the global spread of participants, except for two participants who preferred to respond to interview questions in writing. One of the responses was provided mostly in Vietnamese and was translated into English for analysis.

Table 1. Stakeholder groups, data collection methods, and participant numbers.

Data collection tools

The questions for the semi-structured interviews and focus groups [Citation39] were developed by a sub-set of the evaluation team and circulated to all members of the evaluation team for review, addition and deletion of items, and wording changes to ensure clarity, especially for questions to be translated into Vietnamese for certain stakeholder groups (e.g., students, Vietnamese university staff, Vietnamese placement supervisors). Translation was undertaken by a NAATI (National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters Endorsed Qualification - https://www.naati.com.au/) accredited English/Vietnamese translator who was experienced with speech-language pathology and teaching and learning terminology. The data collection tools are included in Appendix 2.

Participant recruitment

All participant recruitment was undertaken by the Vietnamese/English bilingual researcher who was not previously known to stakeholders; that is, she had not been involved in curriculum design, implementation, teaching or clinical placement supervision. Having a person unknown to research participants is considered beneficial to reducing the risk of coercion which may arise from a request for participation in the research from a person known to participants. This is particularly relevant in Vietnamese culture where emphasis is placed on saving face, particularly with those perceived to be in a position of power [Citation40]. Emails were sent in the appropriate language to prospective participants in each stakeholder group, using email addresses already held in the project database. The email invited stakeholders to participate in a semi-structured interview or focus group, with an attached Information Sheet which provided the contact details of the primary researcher if potential participants had questions about the research, a Consent form, and links to Doodle Polls seeking preferences for interview/focus group dates and times. On receipt of the consent form and response to the Doodle Poll, interviews and focus groups were arranged Reminder emails were sent to all prospective participants at two weeks after original contact and again two weeks later, in order to maximise participant numbers.

Data analysis

Data collected in Vietnamese were translated and all data were analysed in English. An initial inductive content analysis [Citation37] was undertaken for the purposes of reporting back to the project funding body (see [Citation39] for further details). One member of the research team developed a coding framework for at least one transcript from each stakeholder group data set. The framework was applied to each data set separately for each of the stakeholder groups and rigour was enhanced through other team members completing the remaining analysis. For this initial analysis, codes were grouped into sub-categories and categories consistent with content analysis methods.

To integrate and synthesise findings across stakeholder groups, three team members reanalysed the data using thematic network analysis, which is useful for organising large amounts of qualitative data and facilitating “structuring and depicting of these themes” [Citation38, p.387]. Two researchers returned to the code level of the data conducted in the initial content analysis. Codes were then grouped and basic themes were identified for each stakeholder group. In accordance with the analysis process described by Attride-Stirling [Citation38], basic themes across all stakeholder groups were ordered hierarchically and then grouped under organising theme levels. A global theme was generated which provided an overarching summary of the interpretation of the data across all stakeholder groups. presents the six steps recommended by Attride-Stirling [Citation38] and a description of how this tool was applied to the reanalysis of the data.

Table 2. Application of thematic network analysis as described by attride & stirling (2001).

Research rigour was enhanced by a third researcher reviewing and discussing the analysis until consensus was reached on the final basic and organising themes. The research team used thick description, that is, provided exemplar quotes for the basic themes in each organising theme, and the third researcher checked that exemplar quotes appropriately illustrated basic themes. Following review of the basic and organising themes, and examination of tables and visual representation, the research team reached consensus on the global theme.

Results

Data analysis identified five organising themes in the collation of 63 basic themes across all stakeholder groups. One global theme was developed: Multi-partner, international collaborations to educate Vietnam’s first degree level SLPs can be satisfying for all stakeholders if stakeholders are prepared for their role and supported at all levels by consistent, high-quality interpreters when needed, and challenges and workloads are managed. A basic theme from every stakeholder group was not always represented in an organising theme and some stakeholder groups had more basic themes represented within specific organising themes. For example, basic themes from the student stakeholder group were highly represented in organising theme 3, The pandemic impacted on program delivery and student learning. Refer to Appendix 1.

provides a visual representation of the overarching global theme in the centre and the five organising themes. Consistent with TNA methods, the global theme captures the essence of the data and the interaction between the organising and basic themes.

Figure 1. Visual representation of thematic network analysis of global theme (dark grey) and organising themes (light grey) (Attride-Stirling, 2001).

Below is a summary of each organising theme using illustrative quotes. Further illustrative quotes are found in .

Table 3. Basic themes and quotes related to organising theme 1: People enjoyed working with others and learning from, with and about others.

Table 4. Basic themes and quotes related to organising theme 2: Benefits from and to stakeholders.

Table 5. Basic themes and quotes related to organising theme 3: the pandemic impacted on program delivery and student learning.

Table 6. Basic themes and quotes related to organising theme 4: Practical challenges were experienced by all stakeholders.

Table 7. Basic themes and quotes related to organising theme 5: Need for preparation with flexibility and recommendations for ongoing success and sustainability.

Organising theme 1 - People enjoyed working with others and learning from, with and about others

All stakeholder groups reported the experience of working collaboratively and learning with others as enjoyable even though there were some challenges, as noted later in themes 3 and 4. Students enjoyed working together and learning from the international lecturers: “I like it most that I could learn a new subject with leading experts. The lectures were very comprehensive, helping us understand each aspect of the lesson” (Student - Master), and with the international placement supervisors: “I enjoyed the clinical placements (CPs) in which we had our supervisors guiding us at the hospitals. We learnt a lot from their feedback and correction” (Student - Bachelor). The international educators enjoyed working with the students: “That’s one thing I really like, that they were responsive, even though there’s a language barrier between the service and a translator between us they are still trying to participate as much as they can” (International lecturer), and admired their dedication to learning despite the language barrier and impact of the pandemic: “I really enjoyed the absolute dedication of the students. They wanted to learn, they wanted to be involved, they wanted to do the best that they could. … despite all of their other [pandemic related] challenges [they] joined every meeting” (International thesis supervisor).

The Vietnamese educators enjoyed the learning opportunities that working with the international educators afforded them: “The opportunity to work with other experts in SLT, a chance to revise knowledge in SLT I learnt before” (Vietnamese placement supervisor).

Most high-level stakeholders felt mutually supported by each other: “The support provided by [NGO] was fantastic. I had regular contact with both my [NGO] mentor and with … the technical adviser to the programs” (High level stakeholder -AVI volunteer); and “We’ve had on ground support by MCNV and universities” (High level stakeholder - Project consultant). Good relationships were seen as key to mutual support: “So for me personally it’s been very satisfying to develop relationships [with people] in another country” (High level stakeholder – TFA). Regular contact and communication were also seen as essential and where this was absent, people felt unsupported: “I felt less supported by the (host) university. I worked from home (in Vietnam, because no office at university) … I didn’t feel we were completely aligned” (High level stakeholder – AVI volunteer). See for all basic themes in this organising theme, with supporting quotes from participants.

Organising theme 2 - Benefits from and to stakeholders

Benefits of participation in the program were reported by all stakeholder groups who participated in the evaluation. Students reported benefiting from their face to face placements: “When we did our placements, we were supervised by great supervisors. This is different from the learning experience that Rehabilitation students majoring in other fields had.” “They taught us in a very detailed way and gave us chance to practise as well” (Students – Bachelor).

Students also reported benefitting from teaching provided by the international educators: “They also combined theories and practice, giving us chance to have hands-on experience of the theories we were learning. … their teaching was always very engaging and interesting” (Student - Bachelor). “They had great teaching methods. They encouraged students to be active learners through group activities and discussions” (Student - Master).

Vietnamese lecturers reported some benefits from exchange of ideas and learning about a new profession in Vietnam: “I also want to be able to pick the minds of those working in similar fields because I know these academics had already been carefully selected. We could start at professional exchange of information and go further from there; I think it would benefit the course as a whole and ultimately, our students.” Vietnamese placement supervisors reported benefits from working alongside international placement supervisors: “I also enjoyed the fact that I was supervised/mentored by Australian supervisors who helped me when I supervised the students. I had a very good supervisor/mentor, he helped answer all questions I had after each clinical practice session.”

Benefits for sustainability of project outcomes were identified by high-level stakeholders and support personnel involved in the project: “I like most the sustainability of the project. … MCNV didn’t choose this easy path [short training programs], they chose a long-term program with more challenges.” (High level stakeholder – TFA); “[we were] always trying to see how we can include the local (Vietnamese) speech pathologists …, to build capacity” (High level stakeholder - project consultant).

See for all basic themes with supporting quotes from participants.

Organising theme 3 - The pandemic impacted on program delivery and student learning

The pandemic impacted the workloads of all stakeholders as teaching pivoted to online learning. High-level stakeholders had difficulty with permissions and acquisition of technology needed to make online delivery viable and most Vietnamese educators had little experience with online teaching prior to the pandemic, so acquiring the technology and skills needed for online teaching was an issue: “When I was preparing for face to face lectures, my teaching plan was different, it involved lots of interactions between lecturer and students. But we had to change to online mode when COVID hit, so I couldn’t use that plan. If I teach again in the future courses, I would like to use the teaching plan with lots of interactions with students” (Vietnamese lecturer).

Rapidly changing requirements were mentioned by a number of groups: “But I think that is COVID … you know you’ve got these grand plans and you know the world comes along and sweeps them out the way …, everything being thrown into the mix and we all, we’ve become very resilient and very flexible in life, I think, as a result” (International lecturer).

International lecturers specifically commented on the onerous workload involved in re-packaging materials intended for face to face delivery for use online and on the intensity of online teaching. Instead of being released from normal duties and their university, they juggled their normal workload and online teaching: “It was exhausting as I did three weeks straight, where I taught from 11am till 7 pm [my] time, five days a week. … and I was still effectively teaching at [my university] at that time as well, so managing my [normal] job between 7 am and 11 am every day” (International lecturer).

International lecturers also noted that online teaching afforded fewer opportunities for developing relationships: “[lecturers who were able to teach face to face in Vietnam before the pandemic] had come back and there were photos [of] lunches and … birthday cakes [with the students]. I got the sense that they got to know those students. … and just the way that she talked about those relationships that she built with individuals and the fact that they cared and …, I felt like I lost that part” (International lecturer).

For students, online teaching meant reduced opportunities for interactive learning: “online learning limited our chance for teamwork and exchange of ideas with other classmates” (Student - Bachelor). Information technology (IT) issues made participation difficult for educators and students: “It was our first time studying online, we were not familiar with the technology and internet connection was not really good - stable, which affected our experience.” (Student-Master). Some students in Vietnam had limited bandwidth or unreliable internet access: “Poor internet connection … I couldn’t hear what the lecturers said. I also couldn’t request them to repeat” (Student - Bachelor). “We lost connection 30-40% of the time and it was annoying to be disconnected or connection quality was not good” (Student - Bachelor).

See for all basic themes with supporting quotes from participants.

Organising theme 4 - Practical challenges were experienced by all stakeholders

There were multiple challenges associated with developing and delivering the degrees for all stakeholder groups. Navigating the Vietnamese processes and regulations was challenging for the high-level stakeholders: “First the program was not in the [government] system yet, so it took time for us to develop the project at first. In Vietnam we had to obey regulations, paperwork requirements, so it was hard” (High level stakeholder – MCNV). Choosing culturally relevant content for subjects and teaching evidence-based practice were challenges for international educators: “I was uncertain whether examples were entirely appropriate given the language differences” (International lecturer); “Trying to teach evidence-based practice where the students … are very conscious that there is no evidence in Vietnam, and so you talk about evidence-based practice and they go, but where is our evidence?” (International lecturer). Teaching to promote clinical reasoning, mindful of current workplace practices was a further challenge: “No one had time for session planning ….so I was trying to teach this, introduce this, but also really aware that the minute I left, it was going to go back to how it was because they didn’t have the time and the structure set up to allow them to do this.” (International placement supervisor)

Several students talked about their “difficulty with English” which limited their learning opportunities, and therefore translation of teaching materials and interpreting was critical to support student access to content in English. However, procuring and retaining sufficient experienced interpreters for the duration of the degrees was difficult. Further, the quality of interpreting and translating was variable. Some was of high quality: “In general, interpreting and translation at the beginning of the course was great but towards the end due to the lack of interpreters, they had to call for others and some of these new people were not that great” (Student - Master); but at other times, translation from English to Vietnamese posed challenges: “many materials … the meaning was lost in translation, making it hard to understand” (Student - Bachelor).

Challenges were exacerbated by the pandemic, as noted in Organising theme 3. In addition, some placements could not be undertaken face to face as planned because hospitals would not allow students and placement supervisors onsite. Face to face placements were replaced with online simulations and case studies, however students reported that these had limitations: “Online placements were not very good as there was too much theoretical knowledge and little practice; we couldn’t practice on real patients and have contact with patients’ parents” (Student – Master).

Students reported feeling less prepared in some areas of clinical practice: [due to pandemic disruptions some topics were not well covered] “swallowing disorder, stuttering. There are others too but those two were the most challenging. The teachers provided us with videos to watch. There was one session for the teachers to guide us and one practice session. Sometimes we didn’t fully understand the video, the time between practice and theory was far apart. And for theory, we read materials by ourselves most of the time” (Student - Master). See for all basic themes with supporting quotes from participants.

Organising theme 5 - Preparation with flexibility and recommendations for ongoing success and sustainability

The need for preparation but flexibility in all roles involved in delivering the degrees was frequently discussed. The need for ongoing involvement of international expertise was requested: “More experts from Australia or other countries to come to Vietnam to teach and supervise to train more SLTs” (Student - Master). Advocacy for the new profession and mentoring of graduates to build capacity and ensure sustainability was also noted: “It’s an important part of our future as well to base it through, you know, the mentoring” (High-level stakeholder – TFA). The need for preparation and consistent availability of quality interpreters was frequently commented on by several stakeholder groups; for example: “Students also noticed the change in interpreters/translators, they know there were trained interpreters/translators and they didn’t see them. They saw someone who has never done specialisation interpreting and now interprets for the [Master] class, that’s not ok. As service users, they noticed that hiccup” (International lecturer).

Students made numerous recommendations for improvement, including for some resequencing of subjects to improve learning: “This is about the order of subjects. Maybe because this is the first program, the arrangement of subjects was not always appropriate. For example, the subject on research methodology should be taught early so that we could start working on our thesis but we learnt that subject when we almost completed our proposal. … some were learnt very early like head and neck disorders, and it took a long time ‘til we learnt cleft palate.” (Student - Master); and about increasing the number of face to face clinical placements (which were reduced due to the pandemic): “the chance for us to review our knowledge learnt in class, apply it to real life, working on real patients. These clinical placements will prepare for us to be ready when working with real patients.” (Student - Master). Vietnamese placement supervisors commented on their need for more clinical experience and training to better support future students: “… gain as much clinical practice experience as possible”; “… update your knowledge and skills of teaching and supervising.”

Most international educators indicated willingness to contribute to future degrees if certain expectations were met; for example, role clarification and increased collaboration with Vietnamese counterparts: “Yes, I would be willing to supervise [theses] again in the future but if I was going to be involved with … a Vietnamese university supervisor, I would only supervise if they came to some of the meetings with the students” (International thesis supervisor); “I think it would have been a positive thing to hear about what would they like, they may not have been able to advise about topics, but a sit down discussion to make it a more collaborative approach” (International thesis supervisor); and increased co-teaching with Vietnamese counterparts: “I think co-teaching [with Vietnamese colleagues] will be fabulous” (International lecturer). See for all basic themes with supporting quotes from participants.

Discussion

A comprehensive evaluation was undertaken of the perspectives and recommendations of all stakeholders involved in Vietnam’s first speech-language pathology degrees: a four-year Bachelor degree for high school leavers and a two-year Master degree for existing health professionals who would lead subsequent speech-language pathology Bachelor degrees. Stakeholders in this international collaborative project included high level personnel who funded and managed the project, educators, students, and support personnel such as interpreters. Qualitative data arising from focus groups and individual interviews was analysed using thematic network analysis [Citation38] to identify perspectives, experiences and recommendations for future curriculum development and delivery of degrees. The analysis identified numerous basic themes which grouped into five organising themes as listed in , and one global theme encompassing the organising themes. Numerous recommendations from all stakeholder groups were identified in the data and are discussed later in the paper. The majority of stakeholders reported mutual benefits and enjoyed working with and learning from each other, but this required stakeholders to be well prepared and committed to their roles in the project and to be clear about their roles in the context of all other stakeholder roles. While they enjoyed the experience, Vietnamese placement supervisors did not report benefits for them, possibly because student supervision was an additional load to their already heavy client caseloads. No qualitative data was available from Vietnamese thesis supervisors about their experiences of co-supervision with international supervisors. On advice about lack of time to participate in interviews or focus groups, a decision was made by the research team to ask this stakeholder group to complete short surveys. Survey data were gathered from other groups also to broaden the data set for the evaluation. While survey data are not the focus of the paper, the responses from all stakeholder groups are similar to the themes in the data collected in interviews and focus groups. Failure to capture interviews with Vietnamese thesis supervisors is a limitation of this study.

It is acknowledged that colonialism is not a historical phenomenon of the past, but rather an ongoing practice implemented through global relationships including health care practices and research methodologies [Citation34]. The pervasive impact of colonialism has been suggested to potentially mute criticism of engagement between Majority and Minority World educators and learners. Our experience with the educators and students involved in this project is that they were willing to express concerns and provide critical feedback in end-of-subject and end-of-placement oral debriefing sessions (these data are not included in the data set for this paper). The data analysed in the evaluation and reported in this paper also was not silent on things not enjoyed; these have been placed into organising themes 3 and 4 which consider “expected” challenges as well as those exacerbated by the pandemic.

Clear communication enabled by good IT and good interpretation was required between stakeholders to support collaboration and role and task implementation. Challenges which inevitably arise in international collaborations and associated workloads for stakeholders need to be managed with flexibility. The pandemic impacted the implementation of the degrees, but flexibility in roles and modes of learning and assessment, as well as management of IT demands and stakeholder workloads allowed continuation and completion of the degrees. Some face to face clinical education placements were curtailed due to the pandemic and although replaced with online case-based learning and simulation, students still reported reduced clinical confidence - see [Citation28] for more detail.

The need for high-quality interpreters and translators trained in speech-language pathology concepts and terminology who were consistently available for teaching and meetings was identified by almost all stakeholders. Students spoke of needing to access the (mostly English language) evidence base and engage in discussions with the English speaking educators. Consideration about the processes of engagement with information that is not the preferred language of students and educators is a key recommendation. Access to Vietnamese-English interpreters would support international lecturers to engage with students in Vietnamese. Further, access to interpreters throughout the entirety of a program would support communication between all parties. This would have resource implications but may lead to graduates being able to access resources for their ongoing professional development and global professional engagement whilst content is developed that is relevant to the Vietnamese context and is available in Vietnamese.

In this project, translation and interpreting challenges arose from insufficient numbers of qualified interpreters with knowledge of speech-language pathology terminology and concepts, difficulties with retention of interpreters, and the variable skill of international lecturers and clinical educators to work with interpreters. The importance of trained interpreters in professional contexts including health education and the delivery of health services has been highlighted previously [Citation41–43]. Further, while interpreters play the primary role in the process of information transmission, professionals working with interpreters must also be skilled in working with interpreters to achieve the desired outcomes of interpreted communications [Citation44].

To support the quality of interpretation and translation in future programs, a number of recommendations are made. Ongoing, targeted training and professional development in speech-language pathology terminology, concepts and professional practice should be available to interpreters so that they are adequately prepared both in terms of knowledge and skills, and understanding of the profession. Education and training should also be available to professionals and others working with interpreters so that they understand the role of interpreters and how to support successful communication via an interpreter.

Induction courses before a program commences and then prior to and during the teaching of individual subjects would support a shared understanding of terminology, concepts and ideas, the nature of a project/subject, including the aims and expected outcomes, and debriefing sessions would allow timely discussion and resolution of issues that have arisen. The convening of both formal and informal networks of speech-language pathology interpreters could provide opportunities to access collegial support, mentoring and professional development, exchange information about developments in the speech-language pathology profession, and may improve retention. It is important to note that as planned, the second iteration of the degrees are being run by Vietnamese SLPs, and interpreting will only be needed when English-speaking educators are invited by them to participate in teaching.

A final insight regarding interpreters relates to the role they may play as mediators or “cultural bridges” between international and local stakeholders. The interpreter as “cultural broker” [Citation45, p.884] is a person who has experience and knowledge in two cultures, translates messages from one language to another, and provides information and guidance regarding cultural and contextual factors that may shape communication. In the current project, the interpreter and coordinator of meetings between international thesis co-supervisors and students was an invaluable mediator. As an experienced academic and researcher with a PhD in aspects of speech-language pathology from an international university, she was able to accurately interpret and translate concepts and terms. She could also, support interactions between students and their international thesis supervisors during online supervision meetings, advise students about their research writing, and provide information to the international co-supervisors who were unfamiliar with Vietnamese thesis requirements.

Despite advice from the project’s speech-language pathology technical consultants about the risks of neo-colonialism [Citation12], Vietnam ministries, funders and managers of the project wanted evidence-based degrees, benchmarked against Minority World countries’ curricula frameworks and scopes of practice. This posed several key problems. For the technical consultants, it created tension between a desire to avoid neo-colonial practices and a desire to respect the stated preferences of Vietnamese stakeholders. A decision was made to respect informed decisions, while continuing to discuss how curricula and scopes of practice might evolve to reflect Vietnamese culture and resources. For curricula designers and educators writing and delivering subjects to meet the request for evidence-based teaching, there was a tension between application of a “Western” evidence base in a culturally different context. While international educators developed and delivered integrated curricula with significant use of case-based learning, with content co-constructed with Vietnamese colleagues to be contextually relevant to Vietnam, engagement with the content by students and Vietnamese clinical educators and academics was challenging. There may be a range of reasons for this, including different understandings of EBP concepts and their relevance to Vietnam; challenges accessing the (mainly) English-language research, data bases and EBP syntheses in speech-language pathology; minimal published speech-language pathology research in Vietnam on which to draw; and lack of time.

Significant consideration was given to the practice context in Vietnam during curricula development and delivery. Wickenden et al. [Citation16] advised that there is a need to critically appraise the suitability of importing programs and materials developed in one context to another, specifically in relation to their cultural appropriateness. Attempts to transpose or duplicate a profession from one context (the Minority World) to another (the Majority World) risks services that are not culturally, linguistically and economically relevant [Citation46]. As an initial step to content development, Vietnamese speech and language therapists, students and SLPs from Minority World contexts with experience working in Vietnam collaborated to develop program content, including clinical cases that were as culturally relevant to the Vietnamese context as possible. Students also provided relevant case examples to lecturers during the teaching of practical activities. Nonetheless, as noted in Organising theme 4, the need for enhanced cultural relevance in the curricula was commented on particularly by students, international lecturers and placement supervisors. Vietnamese speech-language pathology academics have now begun to build a culturally relevant evidence base; professional development in EBP is also a future consideration.

As argued by Abrahams et al. [Citation12], for the speech-language pathology profession to be culturally responsive, there is a critical need to examine the colonial and power-based origins of the profession and reconceptualise the profession by moving towards a framework that privileges the knowledges, experiences, and preferences of diverse communities and contexts. Examination of Minority World frameworks currently guiding the education and practice of speech-language pathologists in Vietnam and curricula revision and adaptation to increase cultural relevance are key recommendations for future degrees in Vietnam. This critical examination and development should be led by the universities at which current and future speech and language therapy programs are delivered, and under the direction of Vietnamese SLPs. Vietnamese stakeholders have requested ongoing international collaborations using mentoring between experienced speech-language pathology academics and Vietnamese speech-language pathology academics to strengthen the capacity of Vietnamese universities to develop their degrees. To ensure the relevance and sustainability of the profession in Vietnam, it will be vital to shift away from international collaborators and consultants as “the experts,” to Vietnamese educators and SLPs leading the development of the profession, including the development of a contextually-relevant evidence base to inform practice of speech-language pathology practice in Vietnam.

While the 5-year project has concluded, the next stage of ensuring sustainability of degrees and ongoing success for the graduates and educators is just beginning. We have begun to implement the numerous recommendations identified in the research and included in the following section. We believe that these recommendations will be of interest to others working to develop education programs in Majority World countries.

Implications for rehabilitation

There are several implications and recommendations, aligned with the organising themes identified in the thematic network analysis, are described below.

In alignment with organising theme 1, People enjoyed working with others and learning from, with and about others, it is recommended that all partners acknowledge the importance of, and continually strive to maintain, good working relationships between stakeholders. This includes considering the cultural and contextual differences, utilising excellent communication and responding with flexibility to challenges.

In alignment with organising theme 2, Benefits from and to stakeholders, it is recommended that all roles are clearly defined so that all stakeholders understand their roles in the context of the larger project. This can be achieved through providing thorough negotiation and briefings so that all stakeholders are collaborating and working to meet clearly defined commitments. Both Vietnamese and international professionals indicated that this work was completed on top of their existing employment commitments. More benefits may accrue for Vietnamese placement supervisors if adjustments are made to their clinical caseloads to make student supervision manageable. For international volunteers, support from employers to include international teaching in their workload could enhance their capacity to contribute.

In alignment with organising theme 3, The pandemic impacted on program delivery and student learning, it is important to acknowledge that unpredictable circumstances may impact on the project. These circumstances may affect different stakeholders differently, so rapid responses, flexibility, empathy, clear communication and willingness to adapt are recommended in these circumstances.

In alignment with organising theme 4, Practical challenges were experienced by all stakeholders, there are several recommendations relating to quality interpretation. It is important to ensure the quality and consistency of interpreters. This includes ensuring strong protocols are in place for sourcing and maintaining quality interpreters, such as committing to consistent and appropriate working conditions, payment, training and continuing professional development (CPD) for interpreters.

The majority of recommendations are aligned with organising theme 5, Preparation with flexibility and recommendations for ongoing success and sustainability. A priority should be to build local capacity for Vietnamese academics, researchers and clinicians for curriculum design to enhance relevance to the local context, teaching, research and supervision of CPs. This could be achieved in a range of ways: through mentoring, using both local Vietnamese expertise and international colleagues; provision of CPD; support of local champions in the profession; and remuneration of international lecturers to retain their involvement.

Limitations and future directions

While this paper provides a diverse range of stakeholder perspectives on the development of Vietnam’s first speech-language pathology degrees, there are a number of limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings. First, this paper provides a descriptive summary of the findings from each of the stakeholder groups; however, the authors recognise the impact of their lens on the interpretation of data, as is inherent with all qualitative research. While the authors come from varied cultural and professional backgrounds, it is acknowledged that the profession of speech-language pathology itself has its roots in colonial notions of homogenising communication styles and Western health practices which may not be easily transferred into Majority World settings [Citation12]. The lack of explicit investigation of coloniality with participants in this research is a limitation. Future research in this space should adopt a critical lens to interrogate the potential impacts of neo-colonialism and power structures on the development of the speech-language pathology profession both in Vietnam and worldwide [Citation34].

Second, it is acknowledged that some participant groups (e.g., Vietnamese lecturers and supervisors) were more difficult to engage and therefore the breadth of their experiences may not have been captured in this research. Future research should consider opportunities to engage hard to reach stakeholder groups to ensure that a diversity of perspectives is represented in the research.

Third, while research materials and data collection were conducted in both Vietnamese and English by a NAATI accredited Vietnamese-English interpreter, funding constraints did not allow for back translation of all materials and responses. The accuracy of the interpretation was therefore not verified. It is also important to acknowledge and address potential differences in the understanding of terms, concepts and ideas that may have resulted from the “triple subjectivity” inherent in cross-cultural research [Citation45 p. 6]. Specifically, the knowledge of the researchers, of the research participants and of the interpreters will be shaped by their culture, gender, language, previous experiences and pre-conceptions [Citation47], and these aspects may impact how ideas, concepts and phenomenon and understood and communicated. In research where understanding of concepts and ideas is necessarily influenced by language and culture, potential for misunderstanding and misrepresentation of information is heightened. This highlights the importance of all members of the research team engaging in discussion throughout the research process to support authentic representation of participants’ experiences.

Fourth, it is acknowledged that some members of the evaluation team were involved in the development of the degrees being evaluated, and that this could lead to bias in the interpretation and reporting of these data. The tensions between “insider” and “outsider” led research in qualitative methodologies is acknowledged [Citation48]. This evaluation attempted to navigate these tensions through the use of an outsider, (i.e., someone not involved in the program), to minimise potential power imbalances during data collection and applying the expertise and knowledge of insiders in data analysis and interpretation.

Conclusion

This paper presents the results of a thematic network analysis of data collected from a range of stakeholders involved in the development and delivery of Vietnam’s first speech-language pathology degrees. Analysis identified a global theme and five organising themes which emphasise the enjoyment and benefits to stakeholders when preparation, collaboration, support to manage challenges, flexibility, and high-quality interpreting are provided effectively. The paper describes the many challenges faced by stakeholders during the pandemic and how these were managed. Several key recommendations were identified in the analysis, which are of relevance beyond Vietnam, to universities and organisations engaged in the development of professional degrees in Majority World countries.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the volunteer speech-language pathologists who developed and taught subjects, and supervised student placements and research theses. We also thank the many Ministry officials, university administrators and academics, non-government organisations, hospital administrators and speech-language pathologists in Vietnam who made this project possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Also known in other countries as speech pathologists, speech therapists,speech and language therapists, phoniatricians, logopedists, as well as other titles. The scope of practice for these latter groups may differ to that of the earlier named groups.

2 In this paper we use the term Majority World and Minority World. These terms are preferred to low/high income countries, developing/developed countries, third world/first world [Citation6]. All terms are contested in the literature [Citation7] but the use of Majority/Minority World appears to be used most frequently in peer reviewed literature.

3 SLT is speech and language therapy.

4 BSLT is refers to student in bachelor of speech and language therapy; MSLT refers to student in master of speech and language therapy.

References

- World Health Organization. Community-based rehabilitation: CBR guidelines. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Eitel S, Vu HT. Management systems international. Speech and language therapy assessment in Vietnam. Washington (DC): US Agency for International Development; 2017.

- Ducote C. Speech-language pathology services for individuals with cleft lip/palate in less developed nations: the operation smile approach. Perspect Speech Sci Orofac Disord. 1998;8(1):12–14. doi: 10.1044/ssod8.1.12.

- Jones H. The development of an access approach to a community-based rehabilitation program. Asia Pac Disabil Rehabil J. 1997;8:39–41.

- Vietnam Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA). Resolution no. 4039 QD-BYT: resolution to approve the national plan of rehabilitation development in the period 2014-2020 Socialist Republic of Vietnam; 2014.

- Shallwani S. Why I use the term ‘Majority world’ instead of ‘developing countries’ or ‘Third world’. Post to Culture and Context, International Development, International Perspectives; 2015. https://sadafshallwani.net/2015/08/04/majority-world/.

- Khan T, Abimbola S, Kyobutungi C, et al. How we classify countries and people – and why it matters. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(6):e009704. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009704.

- World Health Organization and World Bank. World report on disability. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011.

- Law J, Boyle J, Harris F, et al. Prevalence and natural history of primary speech and language delay: findings from a systematic review of the literature. Intl J Lang Comm Disor. 2000;35(2):165–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-6984.2000.tb00001.x.

- Speech Pathology Australia. Submission to the senate community affairs reference Committee - Inquiry into the prevalence of different types of speech, language and communication disorders and speech pathology services in Australia. Melbourne: Speech Pathology Australia; 2014.

- Mpofu E. Rehabilitation an international perspective: a Zimbabwean experience. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23(11):481–489. doi: 10.1080/09638280010008889.

- Barrett H, Marshall J. Implementation of the world report on disability: developing human resource capacity to meet the needs of people with communication disability in Uganda. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2013;15(1):48–52. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2012.743035.

- Wylie K, McAllister L, Davidson B, et al. Adopting public health approaches to communication disability: challenges for the education of speech-language pathologists. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2014;66(4–5):164–175. doi: 10.1159/000365752.

- International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. Special issue on responses to world report on disability. Int J Speech-Lang Pathol. 2013;15(1).

- Lüdtke U., Kiya E, Kinyua Karia M. (Eds). Handbook of speech-language therapy in Sub-Saharan Africa: integrating research and practice. Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2023.

- Wickenden M, Hartley S, Kariyakaranawa S, et al. Teaching speech and language therapists in Sri Lanka: issues in curriculum, culture and language. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2003;55(6):314–321. doi: 10.1159/000073255.

- Wylie K, McAllister L, Davidson B, et al. Changing practice: implications of the world report on disability for responding to communication disability in under-served populations. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2013;15(1):1–13. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2012.745164.

- Abrahams K, Kathard H, Harty M, et al. Inequity and the professionalisation of speech-language pathology. Prof Professionalism. 2019;9(3):3285.

- Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):380–383. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.3.380.

- World Health Organization (WHO). International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Vietnam General Statistics Office. The national survey on people with disabilities. Hanoi: Vietnam Statistics Office; 2016.

- World Health Organization. Human resources for health country profiles: Vietnam. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Atherton M, McAllister L, Luong TCV, et al. Community-based rehabilitation workers in Vietnam need assistance to support communication and swallowing: sustainable development goals 3, 4, 8, 10, 17. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2023;25(1):107–111. doi: 10.1080/17549507.2022.2132292.

- Landis PA. Training of a paraprofessional in speech pathology: a pilot project in South Vietnam. ASHA. 1973;15(7):342–344.

- Armstrong E, Pham D, Nguyen TT, et al. Needs assessment on speech and language therapy education (SALT) in Vietnam; 2018. https://trinhfoundation.org/news/needs-assessment-on-speech-and-language-therapy-(salt)-education-in-vietnam.

- Nguyen SD, Nguyen DV, McAllister L, et al. Self-help and help seeking by families of children with a communication disability in Vietnam. (in preparation).

- Revised IALP Education Guidelines. (September 1, 2009): IALP guidelines for initial education in speech-language pathology. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2010;62:210–216. doi: 10.1159/000314782.

- McAllister L, Atherton M, Winkworth A, et al. A descriptive case report of tele-supervision and online case-based learning for speech and language therapy students in Vietnam during the Covid-19 pandemic. S Afr J Commun Dis. 2022;69(2):a897.

- Ahmad K, Ibrahim H, Othman BF, et al. Addressing education of speech-language pathologists in the world report on disability: development of a speech-language pathology program in Malaysia. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2013;15(1):37–41. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2012.757709.

- Bondoc IP, Mabag V, Dacanay CA, et al. Speech-language pathology research in the Philippines in retrospect: perspectives from a developing country. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2017;19(6):628–636. doi: 10.1080/17549507.2016.1226954.

- Karanth P. Four decades of speech-language pathology in India: changing perspectives and challenges of the future. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2002;54(2):69–71. doi: 10.1159/000057917.

- Berger R. Now I see it, now I don’t. Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2015;15(2):219–234. doi: 10.1177/1468794112468475.

- Hunter DJ, McCallum J, Howes D. Defining exploratory-descriptive qualitative (EDQ) research and considering its application to healthcare. Proceedings of Worldwide Nursing Conference 2018. Worldwide Nursing Conference; 2018. http://nursing-conf.org/accepted-papers/#acc-5b9bb119a6443.

- Watermeyer J, Neille J. The application of qualitative approaches in a post-colonial context in speech-language pathology: a call for transformation. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2022;24(5):494–503. doi: 10.1080/17549507.2022.2047783.

- Stebbins RA. Exploratory research in the social sciences. London: Sage Publications; 2001.

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;33(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G.

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

- Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual Res. 2001;1(3):385–405. doi: 10.1177/146879410100100307.

- McAllister L, Tran V, Verdon S, et al. Report on evaluation of the implementation of the project of speech and language therapy education development in Vietnam. Hanoi: Trinh Foundation Australia and the Medical Committee of Netherlands Vietnam; 2022.

- Kien NT. The “sacred face”: what directs Vietnamese people in interacting with others in everyday life. J Soc Sci Humanit. 2015;1:246–259.

- Beltran-Avery MP. The role of the health care interpreter: an evolving dialogue. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. Washington (DC): National Council of Interpreting in Health Care; 2001.

- Santhanam SP, Gilbert CL, Parveen S. Speech-language pathologists’ use of language interpreters with linguistically diverse clients: a nationwide survey study. Commun Dis Q. 2019;40(3):131–141. doi: 10.1177/1525740118779975.

- Elkington EJ, Talbot KM. The role of interpreters in mental health care. SAfr J Psychol. 2016;46(3):364–375.

- Clark E. Interpreters and speech pathologists: some ethnographic data; 2020. https://criticallink.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CL2_Clark.pdf.

- Temple B, Edwards R. Interpreters/translators and cross-language research: reflexivity and border crossings. Int J Qual Methods. 2002;1(2):1–12. doi: 10.1177/160940690200100201.

- Hyter YD. A conceptual framework for responsive global engagement in communication sciences and disorders. Topics Lang Dis. 2014;34(2):103–120. doi: 10.1097/TLD.0000000000000015.

- Caretta M. Situated knowledge in cross-cultural, cross-language research: a collaborative reflexive analysis of researcher, assistant and participant subjectivities. Qual Res. 2015;15(4):489–505. doi: 10.1177/1468794114543404.

- Dwyer SC, Buckle JL. The space between: on being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2009;8(1):54–63. doi: 10.1177/160940690900800105.