Abstract

A key question in drugs research is why people use psychoactive substances. Diverse motives such as boredom, habit, and pain relief have served as explanations, but little is known about how adult cannabis users motivate their use in prohibitionist policy contexts, like Sweden. The aim is to explore what motives a sample of adult Swedish cannabis users refer to when they give meaning to their use. We ask: what aspects of cannabis use (e.g. drug effects, individual characteristics and social contexts) are emphasized in their accounts, and how are such aspects combined to describe motives and justify use? In this study, motives are perceived as culturally situated action, and our analysis is based on online text messages (n = 238) and interviews (n = 12). Participants emphasized either the characteristics of the use situation (motives such as party, relaxation and social function) or of him-/herself as an individual (motives such as mindfulness, identity marker and somatic function). They often mentioned medical and recreational motives in the same account, and carefully presented themselves as rational individuals. The motives reflect that the drugs discourse is increasingly medicalized, that responsibility is highly esteemed in contemporary societies, and that cannabis use is still stigmatized in Sweden.

Keywords:

Introduction

The question of why people use psychoactive substances has always spurred research. Diverse motivating factors such as curiosity, habit, peer pressure and pain relief have been put forward. Regarding cannabis, research has shown that people primarily use it for time-out (e.g. Parker, Aldridge, & Measham, Citation1998), enhancement (e.g. Osborne & Fogel, Citation2008), social conformity (e.g. Cloutier, Kearns, Knapp, Contractor, & Blumenthal, Citation2019; Lee, Neighbors, & Woods, Citation2007) and pleasure in a wide sense (e.g. Hathaway, Citation2004; Liebregts et al., Citation2015).

Recent research, however, also stresses a link between drug policy developments and fluctuations in reported consumption motives (Mitchell, Sweitzer, Tunno, Kollins, & McClernon, Citation2016). In line with this, some studies suggest that the political trend of legalizing medical cannabis use is related to an upsurge of medical motives (Athey, Boyd, & Cohen, Citation2017; Lancaster, Seear, & Ritter, Citation2017; Lankenau et al., Citation2018; Lau et al., Citation2015; Mitchell et al., Citation2016; Satterlund, Lee, & Moore, Citation2015). People report using cannabis in order to reduce symptoms related to ADHD (Pedersen, Citation2015), multiple sclerosis and rheumatism (Coomber, Oliver, & Morris, Citation2003), and sleep deprivation and unrest (O'Brien, Citation2013). This seems to be the case also in regions with restrictive attitudes and primarily illegal markets (Dahl & Asmussen Frank, Citation2011; Hakkarainen et al., Citation2015; Pedersen, Citation2015; Ware, Adams, & Guy, Citation2004).

In parallel with these findings, it has been argued that the boundaries between medical and recreational motives have blurred (Athey et al., Citation2017; Hakkarainen et al., Citation2019; Pedersen & Sandberg, Citation2013). People also appear to have several motives for substance use, rather than a single one (Cloutier et al., Citation2019; Littlefield, Vergés, Rosinski, Steinley, & Sher, Citation2013; McCabe & Cranford, Citation2012). Moreover, it has been stated that some drug effects (e.g. feeling lethargic) can be sought after in one context (relaxation) and seen as problematic in another (working) (Hathaway, Citation2004), and that biochemical effects often play a minor role in users’ experiences (Shortall, Citation2014).

Studies conclude that adult cannabis users often describe it as a solitary practice, less characterized by peer interaction than youth use (Asmussen Frank, Christensen, & Dahl, Citation2013; Kronbaek & Asmussen Frank, Citation2013), and as a responsible and rational behavior if conducted properly (Dahl & Demant, Citation2017; Duff et al., Citation2012; Lau et al., Citation2015; Rödner, Citation2006). Despite a growing literature, it is evident that more research is needed on adult cannabis use and related motives and justifications (Asmussen Frank et al., Citation2013; Dahl & Demant, Citation2017; Hathaway, Citation2004; Kronbaek & Asmussen Frank, Citation2013), not least from different cultures (Duff et al., Citation2012) such as those characterized by drug prohibitionism.

While the cannabis legalization movement has had major influence on drug policy in other Western states (Pardo, Citation2014; Rogeberg, Citation2015), it is non-existent in Sweden with its long tradition of prohibition (Edman & Olsson, Citation2014) and political goal of a drug free society (Skr, Citation2015/16:86). All involvement with illicit drugs is criminalized, including a maximum penalty of six months imprisonment for personal use. State-regulated medical cannabis is miniscule. Last month use among persons aged 15–34 is also notably lower in Sweden (2.2%) compared with other European countries (e.g. Denmark: 6.1% and Germany: 6.7%, EMCDDA, Citation2018). Regardless of these comparably low prevalence figures, police work often targets street-level drug use (Tham, Citation1998). Thus, the Swedish situation regarding cannabis use and control does not reflect central claims of the normalization thesis (Parker et al., Citation1998), which states that there has been an increase of supply, demand and cultural acceptance of the substance (Liebregts et al., Citation2015).

The normalization thesis (Parker et al., Citation1998) has gained much attention (Measham & Shiner, Citation2009; Pennay & Measham, Citation2016; Sznitman & Taubman, Citation2016) and support in research on both youth (e.g. Duff, Citation2003, Citation2005; Järvinen & Demant, Citation2011; Järvinen & Ravn, Citation2014) and adult drug use (e.g. Duff et al., Citation2012; Lau et al., Citation2015; Liebregts et al., Citation2015). However, its tenet that cannabis users no longer feel stigmatized and forced to justify their use has been challenged. Data from various contexts suggest that cannabis users do worry about legal sanctions, try to hide their use (Hathaway, Citation2004; Hathaway, Comeau, & Erickson, Citation2011; Lau et al., Citation2015; Liebregts et al., Citation2015) and are eager to justify it (Pennay & Moore, Citation2010; Peretti‐Watel, Citation2003; Sandberg, Citation2012). From this perspective, it has been concluded that cannabis use should still be perceived as stigmatized deviance, at least in contexts with comparably low levels of use and high levels of control, such as the Nordic countries (Asmussen Frank et al., Citation2013; Dahl & Demant, Citation2017; Sznitman, Citation2008).

On the basis of these considerations, the aim of this article is to explore what motives Swedish adult cannabis users refer to when they give meaning to their use. We ask: what aspects of cannabis use (e.g. drug effects, individual characteristics and social contexts, what Zinberg (Citation1984) in his classic work on drug addiction defines as drug, set and setting) are emphasized in their accounts, and how are such aspects combined in order to describe motives and justify use? Rather than descriptively adding to previous lists of cannabis use motives, our ambition is to go into detail with how motives are structured in accounts and how they reflect and perhaps shape cultural norms that surround cannabis in Sweden today.

Theory

We analyse motives as ‘story-like constructions’ (Orbuch, Citation1997, p. 459), and focus on how individuals, when they are ‘doing motives’ (Blum & McHugh, Citation1971, p. 104), produce, reproduce and make intelligible their social reality. We use Burke’s (Citation1969/Citation1945) theory on dramatism which provides ‘a logic of inquiry’ into motives (Overington, Citation1977, p 133). It was recently used by Järvinen and Miller (Citation2014) in a study of how staff at harm reduction programs talk about their work. As they point out, Burke’s framework can be used ‘for comparing and contrasting diverse vocabularies of motives’ (Järvinen & Miller, Citation2014, p. 882; see also: Athey et al., Citation2017; Osborne & Fogel, Citation2008). As Burke (Citation1969/Citation1945) emphasizes the role of context, his work is well-aligned with research on adult cannabis users showing the importance of the setting for drug use experiences and for the reporting of different motives (e.g. Duff et al., Citation2012; Hathaway, Citation2004).

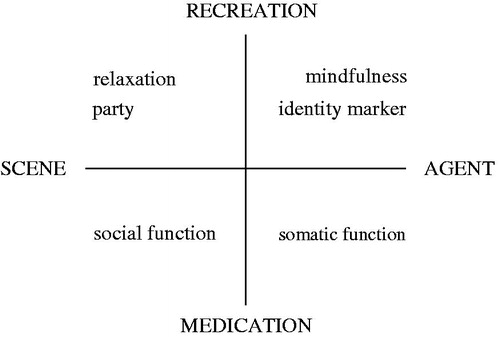

Burke (Citation1969/Citation1945) suggests that motives always, explicitly or implicitly, encompass five interrelated aspects – act, scene, agent, agency and purpose – that together form the so-called ‘dramatistic pentad’. Crucial are the relationships, the so-called ratios, between aspects that evoke particular vocabularies of motive (Anderson & Prelli, Citation2001). Some ratios may be more salient in a given empirical case (Meisenbach, Remke, Buzzanell, & Liu, Citation2008). In our analyses (see more under Methods and ), the scene-act ratio and the agent-act ratio were clearly identifiable and gave structure and meaning to the cannabis users’ accounts. The scene-act ratio encompasses instances where the act emanates from and can be seen as an extension of what lies implicitly in the scene (Burke, Citation1969/Citation1945, p. 7). In the agent-act ratio, focus shifts from the quality of the situation to the quality of the person. In these instances, the motive is situated in the characteristics of the agent. The act is thus described as a representative extension of the individual’s identity and personality (Burke, Citation1969/Citation1945, p. 19).

Methods

Online sample

We approached users at Sweden’s largest and most important online forum for drug discussions called Flashback Forum (Månsson, Citation2017).

In October 2017 we started a discussion thread at this forum, presenting the research project and posing the following questions: 1) ‘Why do you use cannabis and what is achieved by doing it?’, 2) ‘What is it like to be a cannabis user in Sweden?’ (see, Barratt, Citation2011 for a similar approach). We also made alerts about this thread in Facebook groups dedicated to cannabis to attract people who might be interested in contributing. Throughout the time the discussion thread was open, the researchers were active in responding to participant queries (see also: Barratt et al., Citation2015).

After eight days we posted a message that we would leave the thread, which ended the discussion. We had then received 238 posts (not including our own) from 150 individual members with an average word count of 200. In this article, we focus on motives, thus primarily analyzing the question of why the participants use cannabis. People at Flashback Forum are anonymous, but there is an age limit of 18 which may indicate that the participants are adults.

Interview sample

Some online contributors and otherwise interested individuals contacted the research team. Although it was not our initial plan to do interviews, those who contacted us were invited to participate in interviews during November/December 2017. No inclusion criteria were used, but all had extensive cannabis experiences. We conducted 12 telephone interviews (45–60 min), with questions relating to three themes: cannabis use (e.g. ‘Can you tell me why you use cannabis?’, ‘Where/when do you use cannabis?’), identity (e.g. ‘How important is it for you to use cannabis?’, ‘Describe your view on risks/problems with using cannabis?’), social context (e.g. ‘What is your view on how society handles cannabis?’, ‘What is it like to be a cannabis user in Sweden?’). The sample consists of Swedish men (n = 10) and women (n = 2) from two age spans, 20–39 years (n = 7) and 40–65 years (n = 5). Half of the sample resided in cities and half in small towns or rural areas. The participants represent a variety of occupations (e.g. self-employed, government employee, academic, blue collar) and living conditions (e.g. family with children, single households). We do not know anything about their ethnic background, but they all spoke Swedish without accent and all but one had Swedish sounding names.

Ethics

We provided information about the research project on Flashback Forum, also stating that participation was voluntary and that anonymity was guaranteed. This information was repeated orally to the interviewed participants. We anonymized participants by changing names and by omitting sensitive information. The study was approved by the ethical vetting board in Stockholm (registration number: 2016/709-31/5 and 2017/2178-32).

Analysis

Since the online posts appeared as answers to a questionnaire, we developed a content-based coding schedule. Thirteen codes (e.g. ‘relaxation’, ‘have fun’, ‘pain’, ‘alternative medicine’) were identified and used to analyze the questions ‘Why do you use cannabis and what is achieved by doing it?’. Individual posts were treated as separate units that could be assigned several codes.

Many participants referred to both recreational and medical motives in their posts. With this as a starting point, we tabulated the frequency of only recreational, only medical, and combinations of recreational and medical motives. A few (6 individuals) did not mention specific motives and could not be classified.

An initial coding based on recreational and medical categories was conducted on both materials (e.g. recreation: ‘to socialize’, ‘to have fun’; medicine: ‘to be normal’, ‘to use less prescribed medicines’). To probe deeper into the motives, the five aspects of Burke’s (Citation1969/Citation1945) theory were applied to these codes. This theoretically driven analysis enabled a more nuanced view on the initial codes, making it possible to see both differences and similarities in how motives were structured.

Following the material, it became clear that the participants primarily relied on the scene-act ratio (Burke, Citation1969/Citation1945, p. 7) or the agent-act ratio (Ibid., p. 19) when motivating their cannabis use. To make the analysis manageable, we therefore focused on these two ratios and made a basic typology. This yielded four qualitatively different accounts of cannabis use: relaxation and party, mindfulness and identity marker, social function and, lastly, somatic function. While this approach cannot fully elucidate all the specifics found in the data, it was useful for making sense of how participants accounted for their cannabis use. The classification of motives as either recreation or medication is based on how they were presented in the empirical material. For example, although previous research indicates that relaxation can be perceived as medical (Pedersen & Sandberg, Citation2013; Reinarman, Nunberg, Lanthier, & Heddleston, Citation2011), we classified it in line with the participants’ focus on recreation.

Results

In the Flashback Forum material it was more common for the participants to line up several reasons for using cannabis, than to describe one single motive. For some, this could be recreational or medical motives, but as seen in , many combined motives from both categories. In individual posts there were accounts of cannabis use as a ‘necessary medicine’ in one paragraph to be followed by ‘getting high’ in the next one.

Table 1. Motives for cannabis use identified in Flashback Forum thread.

Before we analyse how the scene-act and the agent-act ratios were manifested in the online and interview material, we briefly outline the logic of the ratios.

Relaxation, party and social function are motives that emphasize the social setting (the scene) of cannabis use. The distinctive feature of these accounts is that the act is described as an extension of the scene. What separates these three motives is the distinction made between how the act of using cannabis was described by participants. In , we illustrate this by placing party and relaxation at the top (recreation) and social function at the bottom (medication).

Mindfulness, identity marker and somatic function on the other hand, are motives that emphasize cannabis use as mainly driven by the individual characteristics of the agent. These motives, focused on the agent-act ratio, are also separated in relation to how the act of using cannabis was described. Mindfulness and identity marker are placed at the top of the figure (indicating recreation) and somatic function at the bottom (indicating medication).

Cannabis use as recreation

Relaxation and party (scene-act ratio)

Participants often mentioned relaxation in their accounts of cannabis use (top left in ). This was typically described as a way to achieve a laidback mode in a secluded social space, for example a cozy Friday night dinner with a partner, equivalent to other people’s wine consumption. Similar to previous research (e.g. Osborne & Fogel, Citation2008), the participants in our study talked about ‘detaching from work’ and ‘stressing down’, where cannabis use represented a break from a demanding life. In all, this type of account illustrated how the participants tried to justify their cannabis use by juxtaposing it with the culturally accepted use of alcohol and by emphasizing that they keep to conventional lifestyles (see also: Dahl & Demant, Citation2017; Kronbaek & Asmussen Frank, Citation2013).

Similar to these accounts were descriptions of how cannabis was used to party (top left in ). The participants were careful to point out that such use was rational and did not interfere with other obligations in life, suggesting the presence of informal rules (Asmussen Frank et al., Citation2013; Hathaway, Citation2004; Rödner, Citation2006). In accounts referring to party, cannabis use was described as indicating a difference between the mundane and the extraordinary that pertained to time-out situations (e.g. travels, music festivals, friend reunions, etc.). This is illustrated by Carl, a man in his 60ies who uses cannabis daily, who talked about when he and his friends visited a reggae club.

I had a few friends over. We were going to a reggae club and everybody was there. Five hundred people dancing and having fun. Then I came home, and the police had busted the door open and torn up the apartment. And found ten grams of weed. And I said: ‘Oh my god, how can you bust the door open? Why didn’t you call?’. ‘We did, but you didn’t answer.’ ‘No you didn’t! Check my phone.’ I don’t know what will happen with it. I have been to a hearing and I’ve told them exactly how it is. ‘Well, this is it: I smoke. It’s for pain and it’s relaxing for me.’

As seen above, the setting is described as somewhat extraordinary, and according to Carl’s story, the event itself seems to justify cannabis use. The act is both expected and accepted at the club. The extract also illustrates how he reformulates a recreational motive (have fun) to a medical motive (pain) when describing a contact with the police, probably because it is believed to render less severe sanctions in a prohibitionist context.

The influence of prohibitionism on motive accounts was also seen in the way the participants approached the question of why they use cannabis. Accounts of medical cannabis use usually surfaced immediately, to be complemented with accounts of recreation later on, when the interview participants were ‘warmed up’ and had received follow up questions. Moreover, it should be noted that Carl’s story about a large social gathering that includes cannabis use is uncommon in the data. While motives referring to the social aspects of cannabis use (such as ‘sharing a joint’) are well-documented (see e.g. Osborne & Fogel, Citation2008), the participants did not present them as particularly relevant in Sweden. Accounts of social situations where cannabis is normalized and everybody uses it without much thought were rare, only mentioned in relation to experiences of using cannabis in other countries such as Thailand, the Netherlands and Spain.

Mindfulness and identity marker (agent-act ratio)

Another motive that focused on recreation was related to bolstering creativity and concentration in for example work, sports or hobbies. These accounts focused on the characteristics of the user and on positive individual traits that distinguished the participant as unique, different from those who do not use illicit substances (see also: Sandberg, Citation2012). Accordingly, cannabis made them able to flourish, enjoy the little things in everyday life and reach a state of mindfulness (top right in ). Mikael, a man in his 30ies who uses cannabis regularly, illustrates this below:

I have also used it [cannabis] before going out running, and it becomes a totally different experience. You enjoy the moment more. […] But I have never tried to use it for any other purpose than being home, an ‘at-home-moment’. So I don’t know what it would be like to do it with a group of friends and go out to a bar.

Here, the participant talks about the joys of cannabis in his everyday life. It should anyhow be noted that Mikael like several other participants started the interview by describing cannabis as something used for its ‘healing powers’ (see below, the section on Somatic function). Mikael discovered the recreational effects after some time of what he described as medical use. Research has suggested that a reversed order is more common (e.g. Athey et al., Citation2017; Coomber et al., Citation2003).

In highlighting cannabis use as enhancement of experience, these accounts targeted how the substance creates certain mindsets. Like Danjel, a man in his 20ies who uses cannabis regularly:

I mean it’s much easier to reach a state of meditation. It’s much easier to write texts. You get a lot of new angles, you progress in all kinds of things depending on what you do. […] I can smoke a joint and sit and go through company structures and think ‘well, you could do something better with this’. You get sort of another perspective. If you write music lyrics, the lyrics will become a bit different.

Unlike accounts of cannabis use as relaxation related to a specific social situation (scene), Danjel here describes how he deliberately uses cannabis to help him prosper in different activities. As illustrated also by Mikael above, this motive account refers primarily to what kind of person the user is (creative, curious, calm) and what drug effects he or she wants to achieve. Similar to Mikael, Danjel furthermore talked about medical motives for using cannabis and described how he has a prescription for Ritalin (ADHD medicine), that he chooses not to use because cannabis serves him better.

Not all accounts of recreational cannabis use that was primarily based on the individual characteristics of the user elaborated on what the participants tried to achieve. Sometimes cannabis use was described as a goal in its own right, as a natural extension of the participants’ identities (‘I’m just that kind of person’), and we consequently labelled this motive identity marker (top right in ). Like Emilia, a woman in her 30ies who uses cannabis daily and claims that cannabis is ‘life-enhancing’ in general but not ‘overwhelming’ or hindering. As seen in the quote below, participants like Emilia also said that there were no particular setting that prescribed cannabis use, it could take place anywhere and anytime as long as no one was bothered (see also: Asmussen Frank et al., Citation2013; Duff et al., Citation2012):

It’s not a big deal to me, and it’s not a big deal for people in my surroundings. I smoke, everyone knows that I smoke. Some of my friends smoke, others don’t. My partner doesn’t smoke. I don’t know, there are no particular occasions for me, I can smoke anytime.

Emilia and participants who accounted for this motive were careful in presenting themselves as ‘normal’ (see also: Dahl & Demant, Citation2017; Sandberg, Citation2012). They described how they had well-paid jobs, acted rationally and responsibly and had social relations with both users and non-users of cannabis. Hans, a man in his 50ies who uses cannabis daily, said:

I earn pretty decently from my job and have a career. So, we are fine, and so are my friends who share this hobby [cannabis] with me. […] don’t get me wrong, but I don’t see mildly on drug abuse. I have a problem with people under the influence of drugs and drunk people. And I have a problem with the language, or the contexts, or the arguments that many times are made by people that I don’t think are like me really. So I just thought ‘I don’t see it like that at all, I don’t feel the high that much, and I do it basically because it’s nice and then there’s not much more to it.’

Hans emphasizes his established position in society, conveying that cannabis use is only one aspect of his rich life. In addition, he opposes the general indulgent views on cannabis circulated at Flashback Forum, and contrasts his own use with drug abuse and being intoxicated. Rather than presenting it as a marker of deviance, the activity is described as a ‘hobby’ and as an extension of a conventional lifestyle. Finally, his account also challenges a prohibitionist drug policy that defines all illicit substance use as problematic. Hans, instead, describes cannabis use as an identity marker similar to having a family and a career.

Cannabis use as medication

Social function (scene-act ratio)

One motive highlighted that cannabis use is helpful in managing ‘everyday demands’, ‘a hectic society’ and a ‘busy family life’. These accounts of achieving social function (bottom left in ), emphasized the social setting and that life is difficult in many respects. The participants described their cannabis use as secret, wholly functional, and as making them capable to engage with people.

Gustav, a man in his 30ies who has been using cannabis on and off since being a teenager, described how his use developed from weekly binge use with friends to daily small doses to cope with family life:

When the family came and it was more everyday routines and such, when you got less time for everything, then I got easily annoyed. I guess I’m like that. And when I get annoyed I act out. […] Then I can have a hit [of cannabis], and then I come down and become calm so I can handle the situation. Become calm and safe, and can let go of the stress that affects my temper. So my need for cannabis increases when I enter stressful everyday environments […] But at work I can handle the stress because then I’m at work.

Cannabis use is here situated within the framework of a conventional family life with routines, stress and arguments. Drug effects such as intoxication are downplayed and sometimes even explicitly rejected, and cannabis use is instead explained with reference to its soothing effects that facilitate social functioning. In this type of account, as also exemplified by Hans’ account above, the motive for cannabis use includes a rejection of typical external categorizations of users, such as ‘drug abuser’. For Gustav, cannabis use was a means to become a ‘good parent’ or a ‘stable partner’, that is, to fit with social situations that required responsibility and stability. While emphasizing this as an effective way to handle everyday concerns, these accounts also involved being afraid of what will happen if the authorities find out about cannabis use (e.g. being fired from work, withdrawal of driver's license and losing custody of children).

Some of the accounts of cannabis as a means to achieve social functioning drew not only on the social context of use, but included explicit references to personal problems. Like Ivar in the quote below, a man in his 40ies who uses cannabis every day to become a ‘well-functioning human being’.

Everybody always called me an ADHD boy since I was young […] So I become calmer [with cannabis] and can focus, foremost. Otherwise I have great difficulties in concentrating, I’m extremely nervous and can hardly sit still. It’s thanks to this, cannabis has changed my life, I’ve used cannabis to get out of a pretty destructive alcohol addiction among other things. There are only benefits for me in every way. So it’s thanks to this I’ve been able to start a company and live off it.

This account shows how cannabis is perceived to help Ivar overcome personal difficulties, and that the use is motivated also with reference to scenic properties (e.g. being labeled an ‘ADHD boy’). Participants who gave this type of account self-identified with some sort of dysfunction, claimed that they were ‘different’ and that they had a hard time matching the expectations of society (see Pedersen, Citation2015). While cannabis use was described as self-medication, the scope of what cannabis can do surpasses here simple fixing of personal problems, and points towards enabling decent living conditions and a mature lifestyle (see Lancaster et al., Citation2017).

However, like so many of the participants in this study, Gustav and Ivar did not only account for medical motives. For example, Gustav described how he could enjoy the moment of a perfect beach sunset on his own by smoking a bit more than usually, and Ivar talked about parties where cannabis was used.

Somatic function (agent-act ratio)

As touched upon above, medical cannabis use was also described with a primary focus on the individual characteristics of the user (bottom right in ). In these accounts, cannabis use was perceived as the best medicine for a variety of diagnoses and conditions, including ADHD, depression, back pain, insomnia and eating disorders. This indicates that the participants wanted to separate their use from recreation. Mikael, a man in his 30ies with an inflammatory disease, claimed to be ‘self-medicating with cannabis’:

What actually interests me are the healing powers of cannabis. For that reason I have smoked cannabis, but also used CBD [cannabidiol, a cannabis compound] oil to decrease the effect of intoxication. Why I did it was, from what I could tell, because the healing components are very much in the THC [tetrahydrocannabinol, a cannabis compound], but it is also what gives an intoxicating effect. And to extract the healing components of the THC you need the other part, that also lessens the feeling of intoxication.

Here, Mikael explained how he actively tried to prevent intoxication through a sophisticated mode of administration (see Pedersen, Citation2015; Pedersen & Sandberg, Citation2013 for similar reasoning about CBD). He also described how he advanced his intuitive understanding of the ‘healing powers’ of cannabis by reading up. This account involves (as also illustrated above by Hans and Gustav) a pronounced control over cannabis use, which contributes to distance the participant from traditional negative labels of cannabis users common in prohibitionist policy contexts (see Rödner, Citation2006). The adoption of a medicalized language and the specialized knowledge about certain strains and their particular effects found in several accounts clearly draws on a medicalized and technical drugs discourse (see also: O'Brien, Citation2013). For example, Carl is looking for ‘Blueberry’ with a high level of CBD to ease his pain, and Danjel alternated as ‘the medical effects depends on the strain.’

This indicates that cannabis had often replaced prescribed medicines like painkillers, antidepressants and ADHD medicine. The participants acknowledged that cannabis was superior to these medicines, as it did not produce unwanted side effects (see also: Lau et al., Citation2015). In such risk comparisons, cannabis was perceived as the better of two substances. Below this is illustrated by Andreas, a man in his 30ies who has been using cannabis daily for a few years:

I had a Ritalin first thing in the morning and then the fucking anxiety started creeping up around 10–11. Then I took an anxiety pill at 12. And then at night you’re so fucking wound up from the Ritalin when it starts to ebb away, so you take a sleeping pill to sleep. Then you are hungover from the sleeping pill so you take medicines to lessen the side effects from the other medicine. It’s just a fucking vicious circle.

While this account presents a ‘vicious circle’ of negative drug effects stemming from state approved substances, and provides a medical motive for using an illicit substance allegedly unrelated to such problems, the participants tended to mix medication with recreation. On the one hand, they distinguished these two kinds of cannabis use, and thus types of motives, by delineating different settings (e.g. alone or with friends), patterns of use (e.g. smoking one ‘hit’ or several joints), frequency of use (e.g. daily or on special occasions) and main purposes (e.g. coping or putting a gilt edge on life). On the other hand, their accounts yielded that they were seldom exclusively dedicated to either medication or recreation.

Discussion

This study analysed motives as retrospective, flexible and context dependent accounts of how individuals acted, in what kind of situation and with what purpose. We identified six main motives for cannabis use: relaxation, party, mindfulness, identity marker, social function and somatic function. The data showed that the participants often embraced both recreational and medical motives for using cannabis, and that their accounts mirrored a prohibitionist drug policy context, a medicalized drugs discourse and attempts to self-present as rational and responsible citizens.

The cannabis use motives accounted for in this study resemble key motives found in previous research, such as enhancement (Osborne & Fogel, Citation2008), relaxation (O'Brien, Citation2013), expansion (Simons, Correia, Carey, & Borsari, Citation1998), time-out (Parker et al., Citation1998), pain relief (Athey, Boyd & Cohen, Citation2017), and reduction of ADHD symptoms (Pedersen, Citation2015). Similarly, the findings corroborate many aspects of adult cannabis use that have been reported before. Of key interest is that cannabis use was only rarely described as a social recreational activity. Instead, the participants generally claimed to hide their cannabis use from outsiders (see also: Hathaway et al., Citation2011; Lau et al., Citation2015; Liebregts et al., Citation2015) and do it privately (see also: Asmussen Frank et al., Citation2013). While this may be a typical characteristic of adult cannabis use, it may also reflect a prohibitionist drug policy where cannabis use is considered as deviance, and where individuals worry about legal sanctions (Edman & Olsson, Citation2014; Sznitman, Citation2008). Studies on youth cannabis use indicate that adolescents often refer to cannabis normalization and risk comparisons (with other substances) to justify their untoward behavior (Pennay & Moore, Citation2010; Peretti‐Watel, Citation2003; Sandberg, Citation2012). The motives identified in this study suggest, instead, that the participants primarily perceived cannabis use as enabling assumedly productive and healthy lifestyles (Trnka & Trundle, Citation2014).

With Burke’s ‘logic of inquiry’ (Overington, Citation1977, p. 133) it became evident that some motives were primarily referring to the characteristics of the individual cannabis user (e.g. improve somatic function), and others referred to the social context (e.g. improve social function). Our study illustrates that when individuals are ’doing motives’ (Blum & McHugh, Citation1971, p. 104), they position themselves in relation to the setting and the drug effects they expect (Zinberg, Citation1984). Our results therefore highlight the importance of taking context into consideration when studying motives.

Furthermore, the participants associated medical and recreational motives with different situations, patterns of use and types of cannabis products. While it can be expected that the setting is emphasized in accounts of recreation such as party and relaxation, it is interesting that the participants in this study described medical cannabis use in a similar fashion. Cannabis use was, for instance, spurred by stressful social situations and thought of as an efficient way to handle and ultimately be able to enjoy them. Regarding accounts that emphasized the personal characteristics of the user, these could be expected in relation to medical cannabis use to cure or handle pain, sleep deprivation and other physical deficiencies. They were, however, more analytically interesting when pinpointing recreational use. In accounts of cannabis use as an identity marker, it was obvious that the participants tried to trivialize cannabis use and distance themselves from the notion that illicit drug users are outcasts.

Our study thus illustrates how the participants tried to characterize adult cannabis use as something better and more medically motivated than youthful and/or abusive cannabis use (see also: Asmussen Frank et al., Citation2013; Lau et al., Citation2015; Sandberg, Citation2012). The interviews and the Flashback Forum posts were filled with references to a medical language where the substance was associated with specific drug effects that could ‘fix’ certain problems. According to our interpretation it also appeared as if the participants thought that medicine was better suited than recreation in justifying their behavior, as exemplified in accounts of trying to avoid intoxication and of expressing medical motives in relation to judgmental observers. This suggests that a potential change in lay discourse on cannabis use may be at hand also in Sweden’s prohibitionist drug policy context, a finding corroborating prior Nordic research (Pedersen & Sandberg, Citation2013). Nothing in our data suggests, however, that the normalization of adult cannabis use that take place in other parts of the world have contributed to lessen the stigmatization that cannabis users report in Sweden.

Limitations

Our sample is small and encompasses a select group of cannabis users with vested interests in rationalizing and placing their acts in a favorable light. It can be assumed that individuals who regard their cannabis use as insignificant or uninteresting, or who primarily use other substances, were unlikely to present themselves at online cannabis forums and were hence not sampled. Therefore, this mapping and analysis of cannabis use motives should not be seen as final or generalizable to the whole population of Swedish adult cannabis users.

Conclusion

There was a fuzzy boundary between accounts of medical and recreational cannabis use motives in this sample of Swedish cannabis users. The participants combined and oscillated between these different motive types. Their careful efforts to explain how cannabis makes them function in everyday life, and how the substance can be used in different situations and with different purposes, perhaps suggest that the Swedish cannabis discourse is nowadays less centered on cannabis use as deviance or rebellion. Given that this indicates a development towards a more nuanced discourse, it is probably the result of recent years’ influx of information about cannabis legalization in other parts of the world. The finding that cannabis use to handle stressful situations was accounted for as primarily a medical motive, may indicate that the medical discourse is expanding to include more aspects of cannabis use. While the medicalization of cannabis use entails a curtailed view on drug use as pleasure (Lancaster et al., Citation2017), it is possible that a stronger discursive link between cannabis and improvements in personal wellbeing can contribute to de-stigmatize users who live under drug prohibitionism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, F.D., & Prelli, L.J. (2001). Pentadic cartography: Mapping the universe of discourse. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 87, 73–95. doi:10.1080/00335630109384319

- Asmussen Frank, V., Christensen, A.S., & Dahl, V.H. (2013). Cannabis use during a life course–integrating cannabis use into everyday life. Drugs and Alcohol Today, 13, 44–50. doi:10.1108/17459261311310844

- Athey, N., Boyd, N., & Cohen, E. (2017). Becoming a medical marijuana user: Reflections on Becker’s trilogy—Learning techniques, experiencing effects, and perceiving those effects as enjoyable. Contemporary Drug Problems, 44, 212–231. doi:10.1177/0091450917721206

- Barratt, M.J. (2011). Beyond internet as tool: A mixed-methods study of online drug discussion (Doctoral dissertation). Curtin University.

- Barratt, M.J., Potter, G.R., Wouters, M., Wilkins, C., Werse, B., Perälä, J., … Blok, T. (2015). Lessons from conducting trans-national Internet-mediated participatory research with hidden populations of cannabis cultivators. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, 238–249. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.12.004

- Blum, A.F., & McHugh, P. (1971). The social ascription of motives. American Sociological Review, 36, 98–109. doi:10.2307/2093510

- Burke, K. (1969/1945). A grammar of motives. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Cloutier, R.M., Kearns, N.T., Knapp, A.A., Contractor, A.A., & Blumenthal, H. (2019). Heterogeneous patterns of marijuana use motives using latent profile analysis. Substance Use & Misuse, 54, 1485–1498. doi:10.1080/10826084.2019.1588325

- Coomber, R., Oliver, M., & Morris, C. (2003). Using cannabis therapeutically in the UK: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Drug Issues, 33, 325–356. doi:10.1177/002204260303300204

- Dahl, H.V., & Asmussen Frank, V. (2011). Medical marijuana–exploring the concept in relation to small scale cannabis growers in Denmark. In T. Decorte, G. Potter, & M. Bouchard (Eds.), World wide weed–Global trends in cannabis cultivation and its control (pp. 57–74). Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

- Dahl, S.L., & Demant, J. (2017). “Don’t make too much fuss about it.” Negotiating adult cannabis use. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 24, 324–331. doi:10.1080/09687637.2017.1325444

- Duff, C. (2003). Drugs and youth cultures. Is Australia experiencing the normalization of adolescent drug use? Journal of Youth Studies, 6, 433–446. doi:10.1080/1367626032000162131

- Duff, C. (2005). Party drugs and party people: Examining the “normalization” of recreational drug use in Melbourne, Australia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 16, 161–170. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.02.001

- Duff, C., Asbridge, M., Brochu, S., Cousineau, M.M., Hathaway, A.D., Marsh, D., & Erickson, P.G. (2012). A Canadian perspective on cannabis normalization among adults. Addiction Research & Theory, 20, 271–283. doi:10.3109/16066359.2011.618957

- Edman, J., & Olsson, B. (2014). The Swedish drug problem: Conceptual understanding and problem handling, 1839–2011. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 31, 503–526. doi:10.2478/nsad-2014-0044

- EMCDDA [European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction] (2018). Statistical bulletin 2018. Retrieved from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/data/stats2018/gps

- Hakkarainen, P., Decorte, T., Sznitman, S., Karjalainen, K., Barratt, M.J., Frank, V.A., … Wilkins, C. (2019). Examining the blurred boundaries between medical and recreational cannabis – results from an international study of small-scale cannabis cultivators. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 26, 250–258. doi:10.1080/09687637.2017.1411888

- Hakkarainen, P., Frank, V.A., Barratt, M.J., Dahl, H.V., Decorte, T., Karjalainen, K., … Werse, B. (2015). Growing medicine: Small-scale cannabis cultivation for medical purposes in six different countries. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, 250–256. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.07.005

- Hathaway, A.D. (2004). Cannabis users' informal rules for managing stigma and risk. Deviant Behavior, 25, 559–577. doi:10.1080/01639620490484095

- Hathaway, A.D., Comeau, N.C., & Erickson, P.G. (2011). Cannabis normalization and stigma: Contemporary practices of moral regulation. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 11, 451–469. doi:10.1177/1748895811415345

- Järvinen, M., & Demant, J. (2011). The normalisation of cannabis use among young people: Symbolic boundary work in focus groups. Health, Risk & Society, 13, 165–182. doi:10.1080/13698575.2011.556184

- Järvinen, M., & Miller, G. (2014). Selections of reality: Applying Burke’s dramatism to a harm reduction program. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25, 879–887. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.02.014

- Järvinen, M., & Ravn, S. (2014). Cannabis careers revisited: Applying Howard S. Becker's theory to present-day cannabis use. Social Science & Medicine, 100, 133–140. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.002

- Kronbaek, M., & Asmussen Frank, V. (2013). Perspectives on daily cannabis use: Consumerism or a problem for treatment? Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 30, 387–402. doi:10.2478/nsad-2013-0034

- Lancaster, K., Seear, K., & Ritter, A. (2017). Making medicine; producing pleasure: A critical examination of medicinal cannabis policy and law in Victoria, Australia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 49, 117–125. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.07.020

- Lankenau, S.E., Kioumarsi, A., Reed, M., McNeeley, M., Iverson, E., & Wong, C.F. (2018). Becoming a medical marijuana user. International Journal of Drug Policy, 52, 62–70. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.11.018

- Lau, N., Sales, P., Averill, S., Murphy, F., Sato, S.O., & Murphy, S. (2015). Responsible and controlled use: Older cannabis users and harm reduction. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, 709–718. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.03.008

- Lee, C.M., Neighbors, C., & Woods, B.A. (2007). Marijuana motives: Young adults' reasons for using marijuana. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 1384–1394. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.010

- Liebregts, N., van der Pol, P., van Laar, M., de Graaf, R., van den Brink, W., & Korf, D.J. (2015). The role of leisure and delinquency in frequent cannabis use and dependence trajectories among young adults. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, 143–152. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.07.014

- Littlefield, A.K., Vergés, A., Rosinski, J.M., Steinley, D., & Sher, K.J. (2013). Motivational typologies of drinkers: Do enhancement and coping drinkers form two distinct groups? Addiction, 108, 497–503. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04090.x

- Månsson, J. (2017). Cannabis discourses in contemporary Sweden: Continuity and change (Doctoral dissertation). Department of Social Work, Stockholm University.

- McCabe, S.E., & Cranford, J.A. (2012). Motivational subtypes of nonmedical use of prescription medications: results from a national study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51, 445–452. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.004

- Measham, F., & Shiner, M. (2009). The legacy of “normalization”: The role of classical and contemporary criminological theory in understanding young people’s drug use. International Journal of Drug Policy, 20, 502–508. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.02.001

- Meisenbach, R.J., Remke, R.V., Buzzanell, P., & Liu, M. (2008). “They allowed”: Pentadic mapping of women's maternity leave discourse as organizational rhetoric. Communication Monographs, 75, 1–24. doi:10.1080/03637750801952727

- Mitchell, J.T., Sweitzer, M.M., Tunno, A.M., Kollins, S.H., & McClernon, F.J. (2016). “I use weed for my ADHD”: a qualitative analysis of online forum discussions on cannabis use and ADHD. PLoS One, 11, e0156614. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156614

- O'Brien, P.K. (2013). Medical marijuana and social control: Escaping criminalization and embracing medicalization. Deviant Behavior, 34, 423–443. doi:10.1080/01639625.2012.735608

- Orbuch, T.L. (1997). People's accounts count: The sociology of accounts. Annual Review of Sociology, 23, 455–478. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.23.1.455

- Osborne, G.B., & Fogel, C. (2008). Understanding the motivations for recreational marijuana use among adult Canadians. Substance Use & Misuse, 43, 539–572. doi:10.1080/10826080701884911

- Overington, M.A. (1977). Kenneth Burke and the method of dramatism. Theory and Society, 4, 131–156. doi:10.1007/BF00209747

- Pardo, B. (2014). Cannabis policy reforms in the Americas: a comparative analysis of Colorado, Washington, and Uruguay. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25, 727–735. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.05.010

- Parker, H., Aldridge, J., & Measham, F. (1998). Illegal leisure: The normalization of adolescent recreational drug use. London: Routledge.

- Pedersen, W. (2015). From badness to illness: Medical cannabis and self-diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Addiction Research & Theory, 23, 177–186. doi:10.3109/16066359.2014.954556

- Pedersen, W., & Sandberg, S. (2013). The medicalisation of revolt: a sociological analysis of medical cannabis users. Sociology of Health & Illness, 35, 17–32. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01476.x

- Pennay, A., & Measham, F. (2016). The normalisation thesis–20 years later. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 23, 187–189. doi:10.3109/09687637.2016.1173649

- Pennay, A., & Moore, D. (2010). Exploring the micro-politics of normalisation: Narratives of pleasure, self-control and desire in a sample of young Australian ‘party drug’users. Addiction Research & Theory, 18, 557–571. doi:10.3109/16066350903308415

- Peretti‐Watel, P. (2003). Neutralization theory and the denial of risk: Some evidence from cannabis use among French adolescents. The British Journal of Sociology, 54, 21–42. doi:10.1080/0007131032000045888

- Reinarman, C., Nunberg, H., Lanthier, F., & Heddleston, T. (2011). Who are medical marijuana patients? Population characteristics from nine California assessment clinics. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43, 128–135. doi:10.1080/02791072.2011.587700

- Rödner, S. (2006). Practicing risk control in a socially disapproved area: Swedish socially integrated drug users and their perception of risks. Journal of Drug Issues, 36, 933–951. doi:10.1177/002204260603600408

- Rogeberg, O. (2015). Drug policy, values and the public health approach–four lessons from drug policy reform movements. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 32, 347–364. doi:10.1515/nsad-2015-0034

- Sandberg, S. (2012). Is cannabis use normalized, celebrated or neutralized? Analysing talk as action. Addiction Research & Theory, 20, 372–381. doi:10.3109/16066359.2011.638147

- Satterlund, T.D., Lee, J.P., & Moore, R.S. (2015). Stigma among California’s medical marijuana patients. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 47, 10–17. doi:10.1080/02791072.2014.991858

- Shortall, S. (2014). Psychedelic drugs and the problem of experience. Past & Present, 222, 187–206. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtt035

- Simons, J., Correia, C.J., Carey, K.B., & Borsari, B.E. (1998). Validating a five-factor marijuana motives measure: Relations with use, problems, and alcohol motives. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45, 265–273. doi:10.1037//0022-0167.45.3.265

- Skr. 2015/16:86. En samlad strategi för alkohol-, narkotika-, dopnings- och tobakspolitiken 2016 – 2020 [A cohesive strategy for alcohol, narcotic drugs, doping and tobacco policy 2016–2020]. Stockholm: Ministry of Health and Social Affairs.

- Sznitman, S.R. (2008). Drug normalization and the case of Sweden. Contemporary Drug Problems, 35, 447–480. doi:10.1177/009145090803500212

- Sznitman, S.R., & Taubman, D.S. (2016). Drug use normalization: a systematic and critical mixed-methods review. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77, 700–709. doi:10.15288/jsad.2016.77.700

- Tham, H. (1998). Swedish drug policy: a successful model? European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 6, 395–414. doi:10.1023/A:1008699414325

- Trnka, S., & Trundle, C. (2014). Competing responsibilities: Moving beyond neoliberal responsibilisation. Anthropological Forum, 24, 136–153. doi:10.1080/00664677.2013.879051

- Ware, M.A., Adams, H., & Guy, G.W. (2004). The medicinal use of cannabis in the UK: results of a nationwide survey. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 59, 291–295. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00271.x

- Zinberg, N.E. (1984). Drug, set, and setting: The basis for controlled intoxicant use. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.