ABSTRACT

ADHD is a disability characterised by hyperactivity, impulsivity and difficulties maintaining attention. Despite extensive research on ADHD, the effects of existing treatments are moderate and inconsistent. Knowledge regarding children’s and adolescents’ everyday experiences of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and their understanding of these experiences is valuable for the further development of interventions. The aim of the following study was to systematically search for and review qualitative research on children’s and adolescents’ everyday experiences and understanding of their ADHD, and to suggest an integrative synthesis of the results. In total, 16 published and unpublished qualitative studies on the subject were identified. The analysis identified four categories: (1) experiences related to one’s body and psychological abilities: lack of control, having difficulties, and the biological determination of these experiences; (2) ambivalent experiences related to one’s own psychological needs: a need to adjust oneself and a need to be accepted as ‘who I am’; (3) ambivalent experience related to social others: demands and expectations are a problem, experiencing lack of belonging and stigma, but also receiving help from close social others; and (4) experiences related to the formation of personal identity. Erikson’s psychosocial theory of personal identity is suggested for an understanding of the results.

Introduction

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a diagnosis characterised by severe difficulties maintaining attention, coupled with impulsivity and hyperactivity (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Other related secondary symptoms of ADHD may be social, emotional and learning impairments (Wehmeier, Schacht, & Barkley, Citation2010), and comorbidity with psychiatric disorders such as disruptive behavioural disorders, depression and anxiety disorders is relatively high (Pliszka, Citation2003). The worldwide prevalence of ADHD among children and adolescents is estimated to be three to seven per cent (Rohde & Polanczyk, Citation2007), with two to nine times higher prevalence among boys than girls (American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force, Citation2013).

There is relatively strong consensus in the scientific community that ADHD is biological in nature (Barkley, Citation2002; Houghton, Citation2006). However, some scholars suggest an integrative approach for the aetiology of ADHD, emphasising the need for the inclusion of social and cultural factors (Singh, Citation2002).

The treatment of ADHD includes pharmacological treatments (Reichow, Volkmar, & Bloch, Citation2013) and psychosocial interventions such as cognitive therapy (Cortese et al., Citation2015), behavioural therapy (Daley et al., Citation2014) and parental training (Zwi, Jones, Thorgaard, York, & Dennis, Citation2011). Generally, the effects of existing treatments are moderate and inconsistent (Chan, Fogler, & Hammerness, Citation2016; Fabiano, Schatz, Aloe, Chacko, & Chronis-Tuscano, Citation2015; Prasad et al., Citation2013), and the predictors of treatment response remain largely unknown (Warikoo & Faraone, Citation2013). Due to the moderate and inconsistent effect of suggested treatments, there is a need for further development of interventions that will help children and adolescents with the disorder.

In order to develop effective interventions, several researchers underscore the need for knowledge concerning children’s own experiences and understanding of their life (Mason & Watson, Citation2014; Soffer & Ben-Arieh, Citation2014). According to this perspective, research in which children are the source of information about their life has high methodological value, as it contributes first-hand contextual information about the child’s experience, knowledge which is valuable from a clinical perspective (Ben-Arieh, Citation2005).

Lately, numerous qualitative studies have been conducted in order to understand children’s perception and understanding of their ADHD. Qualitative research methods allow for an open-ended exploration of the complexity of experiences, but also enable us to understand the actual manifestation of children’s behaviours in everyday situations and the contextual aspects related to these behaviours (Saini & Shlonsky, Citation2012). Thus, the purpose of this paper is to systematically search for and identify existing qualitative studies on the subject and to suggest an integration of their findings. The intended result of such integration would be to make sense of the available literature, to provide a broader, more context-sensitive and integrative understanding of how children and adolescents with ADHD experience their ADHD in everyday life and how they perceive these experiences.

Method

Study Design

The method that was used as a guide for the synthesis of the qualitative studies is the one suggested by Sandelowski and Barroso (Citation2007). This broadly used method in the context of health-care research (Saini & Shlonsky, Citation2012) aims to systematically review and integrate the findings from various qualitative research reports and to suggest an understanding of the phenomenon in a manner entailing more than merely the sum of all the studies’ results (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2007). The method consists of three stages: firstly, a systematic search for and retrieval of qualitative research reports; secondly, a critical appraisal of the identified reports according to inclusion criteria; and thirdly, an interpretative integration of the findings of those studies regarded as eligible by creating a categorisation of these findings.

Systematic Search for and Retrieval of Research Reports

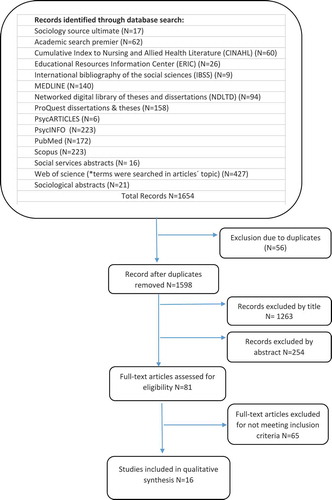

The inclusion criteria (see ) were defined as studies on children’s and adolescents’ experiences and understanding of their ADHD, whereby qualitative methods were used for collecting and analysing data. The children and adolescents, diagnosed with ADHD, had to be under 19 years of age at the time the study was conducted. A systematic search in 15 electronic bibliographic databases was performed in order to find research relevant to the aim of the study (see ). With the intention of finding a wide sample of reports, the search included peer-reviewed published articles as well as unpublished doctoral dissertations. The reason for the inclusion of doctoral-level theses in the search is that they are often an important source of knowledge in the area of health research (Olsson, Sundell, & Olsson, Citation2016), and are generally of satisfactory scientific quality as they are reviewed and assessed by an examination committee (Holbrook, Bourke, Lovat, & Dally, Citation2004).

Table 1. Inclusion criteria for studies in the meta-synthesis.

The parameters that were set in order to find studies regarding children were: ‘Children’ OR ‘Teenagers’ OR ‘Adolescence’ OR ‘Youth’ OR ‘Teens’. The search parameters that were set for ADHD were: ‘ADHD’ OR ‘Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder’ OR ‘Attention deficit’ OR ‘Hyperactivity disorder’. Following the recommendations of Sandelowski and Barroso (Citation2007), the methodological parameters that were set in order to find qualitative studies were: ‘Constant comparison analysis’ OR ‘Content analysis’ OR ‘Descriptive study’ OR ‘Discourse analysis’ OR ‘Ethnography’ OR ‘Exploratory analysis’ OR ‘Field observation’ OR ‘Field study’ OR ‘Focus group’ OR ‘Grounded theory’ OR ‘Hermeneutic’ OR ‘Interview study’ OR ‘Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis’ OR ‘Narrative’ OR ‘Naturalistic’ OR ‘Participant observation’ OR ‘Phenomenology’ OR ‘Qualitative methods’ OR ‘Qualitative research’ OR ‘Semiotics’ OR ‘Thematic analysis’.

The search was defined to look for the parameters in the studies’ abstracts. No temporal parameters were set besides the endpoint of the search process, which was April 2017. Due to practical restraints, the search for studies was limited to those that were written in English. The search process was undertaken with continuing consultation with a reference librarian.

Critical Appraisal of Studies

The critical appraisal of the studies consisted of two stages. In the first stage, in order to determine whether the report met the inclusion criteria, the titles, and if necessary the abstracts as well, were read and evaluated to determine overall relevance. Articles deemed relevant according to the inclusion criteria were exported to the reference management software Refworks©. Duplicate studies were identified by the software. Subsequently, the selected articles were closely read in their entirety to determine their relevance, again according to the inclusion criteria. At the end of this stage, an assembly of studies to be included in the meta-synthesis was completed. In the second stage of the critical appraisal, a cross-study tabular display with information from each study regarding different aspects of the study was constructed. These aspects were: location of the study, purposes and questions, characteristics of participants, conceptual and theoretical frameworks, methods for collecting and analysing data, and the study’s findings. This summary of research characteristics enabled increased comprehension of each individual study and made it easier to compare between the studies and search for patterns. To ensure validity of critical appraisal, continuous consultation was undertaken with a researcher supervisor with extensive experience in qualitative research.

Considering the lack of agreement regarding quality assessment of qualitative research and the intra-reviewer inconsistency related to the use of such assessments (Mays & Pope, Citation2000), no critical appraisal of research quality was applied. In line with the method suggested by Sandelowski and Barroso (Citation2007), the critical appraisal of studies presented here ‘emphasizes differences in kind between qualitative findings as presented in research reports, not differences in quality between qualitative studies’ (p. 138).

Classifying Studies’ Findings: Identifying Categories and Interpretative Integration

The purpose of this stage of the analysis was to inductively identify categories and underlying conceptual relationships between themes that were found in the different studies. The classification of themes was done based on semantic relationships between them, such as ‘X is a type of Y’, ‘X is a reason for doing Y’, ‘X is a consequence of Y’ and ‘X is a part of Y’. In the taxonomic analysis, it was not the prevalence of the appearance of a theme that was significant but rather the theme’s contribution to the conceptual understanding of the categories and the relations between them.

The interpretative integration aimed to suggest a comprehensive understanding of the categories identified through the taxonomy analysis, and how the different categories may be related to each other. To ensure validity of the suggested categories and the interpretative synthesis, internal peer reviews were applied during the integration procedure. These peer-review procedures were carried out in the form of three seminars, at which the different possible interpretations of the data as well as the validity of these interpretations were discussed. Internal peer reviewers were both experts in research methodology and individuals with clinical knowledge in the subject area.

Ethical Approval

All studies included in the synthesis had been approved by an ethics committee. Ethical approval for the present study was not required, as it involved the synthesis of existing literature based on studies conducted with ethical approval.

Results

The systematic search for studies (see ) generated 1,654 articles, and exclusion due to duplication and the initial screening of titles and abstracts resulted in a remaining 81 articles. These articles were read in their entirety and assessed for eligibility, resulting in a total of 16 articles, which were used in the meta-synthesis. Critical appraisal of these 16 studies included in the meta-synthesis (see ) showed that 12 were published, peer-reviewed articles, and four were unpublished doctoral dissertations. Most studies were conducted in the UK (44%) and in the US (18%), and the majority used semi-structured interviews (81%). Methods of data analysis varied from discourse analysis, constant comparative analysis, thematic data analysis and content analysis to interpretative phenomenological analysis. In total, an aggregate of 205 participants were involved in the studies, 149 boys (73%) and 56 girls (27%) ranging from six to 19 years old. Most of the children and adolescents were taking medication regularly or had experience of taking medication.

Table 2. Summary of papers included in meta-synthesis by aims, methodological design, data analysis, participants, and results.

The interpretation and categorisation of the data generated four categories (see ). The first category relates to experiences of corporeal and psychological abilities of behaviours, emotions and cognitive abilities. The reason for categorising these experiences together is that they express individual internal processes that are often interrelated. This ‘body, behaviours, emotions and cognitions’ category consisted of three subcategories: lack of control; having difficulties; and biological determinates. The ‘lack of control’ subcategory expresses themes related to children’s and adolescents’ experiences of having difficulties controlling their behaviours, of having overwhelming emotions that they experience lacking the ability to control, and having difficulties maintaining focus and controlling their attention. The second subcategory consists of themes related to the notion of experiencing difficulties and living with a disability. The third subcategory, related to experiences concerning corporeal and psychological abilities, is based on their being biologically determinate, a consequence of being biologically different. Interestingly, only one study reports a theme expressing children’s and adolescents’ positive experiences related to their body, behaviours, emotions and cognitions.

Table 3. Categorisation of children’s experiences and understanding of their ADHD.

The second category that was found related to themes expressing children’s and adolescents’ thoughts, feelings and experiences of what needs they have. A subcategorisation of these experiences resulted in two subcategories describing the two somewhat ambivalent experiences of the need to adapt but also to be accepted for ‘who I am’. The one subcategory expresses the need to be able to adjust to demands related to everyday situations, for example by being able to control themselves. This can be achieved by taking medication and developing adaptation skills. The other subcategory consists of the experience of needing to be accepted as ‘who I am’ without adjustments or efforts to control oneself. This ambivalence between the needs of self-adaptation and of being accepted as ‘who you are’ is particularly exemplified in the ambivalence of experiences involving medication. In some studies medication was experienced as a help, enabling behavioural control, while in other studies it was experienced as a factor contributing to children’s experience of lack of control, as it enables them to attribute their own behaviour to being on or off medication.

The third category that was identified considers themes related to children’s and adolescents’ experiences of their social environment. Similar to the second category, an ambivalent sense of experience was recognised within the subcategories. The first three subcategories expressed negative experiences of social others: others have demands and expectations that lead to the manifestation of ADHD and negative feelings; experience of stigmatisation; and a lack of belonging. On the other hand, the fourth subcategory reflects themes regarding others as a source of help and support – support which is necessary for everyday functioning.

The fourth category involved experiences of self-identity formation and was comprised of themes related to the question of ‘who I am’. Two subcategories were identified related to different types of experiences. The first consisted of themes describing challenges in the experience of identity formation. Such themes included ‘ADHD defined self’, meaning that children and adolescents perceived who they were in terms of ADHD diagnosis criteria, and defined themselves in terms of how they have been perceived by others rather than how they have perceived themselves. The second subcategory related to themes describing normative experiences of identity formation.

Discussion

A clear characteristic of the first three categories of experiences is the expression of a lack of control and ambivalence. Children and adolescents with ADHD may experience their behaviours, emotions and cognitions as things that exist outside themselves, as aspects not related to their will and intentions but rather to the ADHD. This experience may create a feeling of separation between the self and one’s own behaviours, thoughts, and emotions. In addition, the experience of one’s own psychological needs is characterised by ambivalence: experiencing a need to adjust to environmental demands and to achieve control over aspects of oneself (by taking medication or training skills) on the one hand, experiencing a need to be accepted as ‘who I am’ on the other. Furthermore, the experience of their closest social environment is ambivalent. Family, teachers and peers, even though they might be a source of help and support, are also a source of demands – the very demands that might lead to the manifestation of the disability. Also, the lack of a feeling of belonging and the experience of being perceived as a stereotype may lead to ambivalent experiences towards social others.

Given the fact that many of the participants in the integrated studies were adolescents, the emergence of themes considering issues of identity formation is not surprising. According to Erikson’s (Citation1968) theory of psychosocial development, the developmental psychosocial task of adolescence is the formation of a stable internal presentation of self, an identity. In Erikson’s view (Citation1994[1980]), even if the first representations of identity occur during childhood, it is only in adolescence that a crystallised form of identity develops, a process in which childhood identifications come to be challenged and replaced by new, more genuine, identity configurations. A positive resolution of this psychosocial process is possible due to the mutuality between the individual and the social environment in which the individual lives, when the social environment allows the individual, with their unique physical and psychological characteristics, to find their meaning and social role in a successful way (Erikson, Citation1968; Erikson, Citation1994[1980]). A possible hypothesis that might be constructed from the results is that the experience of children and adolescents with ADHD of forming a stable personal identity might be related to their experience of a lack of control over their body, behaviours, emotions and cognitions as well as their ambivalence towards their psychological needs and their close social environment. This assumption, however, should be further developed in future research, as it can have significance in clinical settings.

Limitations

A qualitative meta-synthesis is a method for integrating qualitative studies to achieve a better, more nuanced understanding of a particular lived experience (Saini & Shlonsky, Citation2012). However, one aspect of this method that should be taken into consideration is the reinterpretation of data that have already undergone initial interpretation. In other words, the synthesised data are two stages away from the individuals’ own words. The ‘words of children and adolescents’ were first interpreted and integrated by the researchers who conducted the original qualitative studies, and these interpretations were interpreted a second time and integrated during the process of the meta-synthesis (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2007). This process runs the risk of losing parts of the participants’ experiences.

Another methodological limitation of the study is the fact that no consideration was made for the time and place in which the studies were conducted. The context underlying a qualitative study can impact upon various aspects related to the relevance or interpretation of the findings. Some of the possible contextual variables may include: social attitudes towards ADHD; educational aspects and legislation that might be different between countries and over periods of time; and what might be significant for the individuals’ experience of ADHD in everyday life and their understanding of these experiences. The aspect of time can also be relevant in regard to changes between different editions of the DSM, as the diagnostic criteria changed between the last two editions. Additionally, the fact that the search criteria were limited to studies written in English may have an impact on the identification of experiences within the meta-synthesis.

A third methodological aspect to consider is the fact that no assessment of the methodological quality of the studies was done. In the meta-synthesis, all studies were weighed equally without taking into consideration the study’s qualitative approach or method of analysis, or the type and size of the study sample. The reason for assessing the studies equally was the relatively limited number of studies that were found on the subject, and the assumption that all the studies have contributed equally to the knowledge in the field.

Disclosure statement

The author has received no direct or indirect financial benefits arising from the direct applications of this research. The author has no potential conflicts of interest regarding this research.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5 ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- Barkley, R. A. (2002). International consensus statement on ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(12), 1389.

- Ben-Arieh, A. (2005). Where are the children? Children’s role in measuring and monitoring their well-being. Social Indicators Research, 573(3). doi:10.1007/s11205-004-4645-6

- Bradley, J. (2009). Children and teacher’s perceptions of adhd and medication (unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Southampton, UK.

- Brady, G. (2014). Children and ADHD: Seeking control within the constraints of diagnosis. Children and Society, 28(3), 218–230.

- Chan, E., Fogler, J. M., & Hammerness, P. G. (2016). Treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adolescents: A systematic review. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 315(18), 1997.

- Cortese, S., Ferrin, M., Brandeis, D., Buitelaar, J., Daley, D., Dittmann, R. W., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2015). Review: Cognitive training for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Meta-analysis of clinical and neuropsychological outcomes from randomised controlled trials. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54, 164–174.

- Daley, D., Van, O., Ferrin, M., Danckaerts, M., Doepfner, M., Cortese, S., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2014). Review: Behavioral interventions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials across multiple outcome domains. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53, 835–847.e5.

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

- Erikson, E. H. (1994[1980]). Identity and the life cycle. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Fabiano, G., Schatz, N., Aloe, A., Chacko, A., & Chronis-Tuscano, A. (2015). A systematic review of meta-analyses of psychosocial treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review, 18(1), 77–97.

- Friio, S. S. (1998). The experiences of adolescents with ADHD, a phenomenological study (unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Calgary, Canada.

- Gallichan, D. J., & Curle, C. (2008). Fitting square pegs into round holes: The challenge of coping with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 13(3), 343–363.

- Grant, T. N. (2009). Young people’s experiences of ADHD and social support in the family context: An interpretative phenomenological analysis (unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of East London, UK.

- Hallberg, U., Klingberg, G., Setsaa, W., & Moller, A. (2010). Hiding parts of one’s self from others - a grounded theory study on teenagers diagnosed with ADHD. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 12(3), 211–220.

- Holbrook, A., Bourke, S., Lovat, T., & Dally, K. (2004). Investigating PhD thesis examination reports. International Journal of Educational Research, 41(2), 98–120.

- Honkasilta, J., Vehmas, S., & Vehkakoski, T. (2016). Self-pathologising, self-condemning, self-liberating: Youths’ accounts of their ADHD-related behavior. Social Science and Medicine, 150, 248–255.

- Houghton, S. (2006). Advances in ADHD research through the lifespan: Common themes and implications. International Journal of Disability, Development & Education, 53(2), 263–272.

- Kendall, J., Hatton, D., Beckett, A., & Leo, M. (2003). Children’s accounts of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Advances in Nursing Science, 26(2), 114–130.

- Kendall, L. (2016). “The teacher said I’m thick!” experiences of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder within a school setting. Support for Learning, 31(2), 122–137.

- Knipp, D. K. (2006). Teens’ perceptions about attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and medications. Journal of School Nursing (Allen Press Publishing Services Inc.), 22(2), 120–125. .

- Krueger, M., & Kendall, J. (2001). Descriptions of self: An exploratory study of adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 14(2), 61–72.

- Levanon-Erez, N., Cohen, M., Bar-Ilan, R. T., & Maeir, A. (2017). Occupational identity of adolescents with ADHD: A mixed methods study. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 24(1), 32–40.

- Leyland, S. (2016). “I was good when I didn’t have it”: giving the ‘ADHD child’ a voice: An interpretative phenomenological analysis (unpublished doctoral dissertation). The University of Wolverhampton, UK.

- Mason, J., & Watson, E. (2014). Researching children: Research on, with, and by children. In A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frønes, & J. Korbin (Eds.), Handbook of child well-being [E-reader version] (pp. 2757–2796). doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9063-8

- Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Qualitative research in health care: Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 320(7226), 50–52. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezp.sub.su.se/stable/25186737

- Olsson, T., Sundell, K., & Olsson, T. M. (2016). Research that guides practice: Outcome research in Swedish PhD theses across seven disciplines 1997–2012. Prevention Science, 17(4), 525.

- Pliszka, S. R. (2003). Psychiatric comorbidities in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Implications for management. Paediatric Drugs, 5(11), 741–750.

- Prasad, V., Brogan, E., Mulvaney, C., Grainge, M., Stanton, W., & Sayal, K. (2013). How effective are drug treatments for children with ADHD at improving on-task behaviour and academic achievement in the school classroom? A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 22(4), 203–216.

- Reichow, B., Volkmar, F., & Bloch, M. (2013). Systematic review and meta-analysis of pharmacological treatment of the symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 43(10), 2435–2441.

- Rohde, L. A., & Polanczyk, G. (2007). Epidemiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20(4), 386–392.

- Saini, M., & Shlonsky, A. (2012). Systematic synthesis of qualitative research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2007). Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

- Singh, I. (2002). Biology in context: Social and cultural perspectives on ADHD. Children & Society, 16(5), 360–367.

- Singh, I., Kendall, T., Taylor, C., Mears, A., Hollis, C., Batty, M., & Keenan, S. (2010). Young people s experience of ADHD and stimulant medication: A qualitative study for the NICE guideline. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 15(4), 186–192.

- Soffer, M., & Ber-Arieh, A. (2014). School-aged children as sources of information about their lives. In G. B. Melton, A. Ben-Aryeh, J. Cashmore, G. S. Goodman, & N. K. Worley (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of child research (pp. 555–574). Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Walker-Noack, L., Corkum, P., Elik, N., & Fearon, I. (2013). Youth perceptions of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and barriers to treatment. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 28(2), 193–218.

- Warikoo, N., & Faraone, S. V. (2013). Background, clinical features and treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 14(14), 1885.

- Wehmeier, P. M., Schacht, A., & Barkley, R. A. (2010). Review article: Social and emotional impairment in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact on quality of life. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46, 209–217.

- Wiener, J., & Daniels, L. (2016). School experiences of adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 49(6), 567–581.

- Zwi, M., Jones, H., Thorgaard, C., York, A., & Dennis, J. A. (2011). Parent training interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children aged 5 to 18 years. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, Art. No.: CD003018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003018.pub3