ABSTRACT

Southeast Asian states are frequently viewed as jealously guarding their sovereignty and unwilling to delegate authority to multilateral organisations or private actors. In the contemporary response to regional piracy and armed robbery at sea (PAR), however, insurers and shippers have come to occupy a central governance role while the fortunes of private security actors (PSAs) have declined. Why? This paper conducts a qualitative case study analysis examining the evolving role of shipping and insurance companies and PSAs in the development and implementation of anti-PAR policies in Southeast Asia today. It argues that while the role of PSAs has diminished due to growing regional governance capacities, regional countries and multilateral regulatory frameworks have enlisted insurers and shippers as governance stakeholders, elevating them from beneficiaries of good order at sea to active shapers of this maritime order. The diverging experiences of PSAs and insurers/shippers demonstrate that the regulatory power relationship between states and private actors is not necessarily zero-sum as the role of insurers and shippers has grown even as state capacities have expanded. Ultimately, the paper illustrates the need to go beyond state- and PSA-centric analyses of maritime governance mechanisms in contemporary Southeast Asia.

Introduction

The notion that Southeast Asian states jealously guard their national sovereignty against the influence of multilateral organisations and private actors permeates analyses of the region’s international relations. The reluctance of regional countries to cede authority is frequently linked to the regional experiences of tensions during the Cold War (Jones Citation2009), and the Association for Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)Footnote1 has since institutionalised the norm of non-interference as a guiding principle (Suzuki Citation2019). Southeast Asian countries also seek to maximise their strategic autonomy and independence in their relations with regional and extra-regional powers (Strangio Citation2020). As Hameiri and Jones (Citation2015) highlight, regional states are thus frequently viewed as seeking to resist broader global trends that see the development of governance models involving non-state actors and different levels of governance. This focus on asserting sovereignty is seen as restricting the scope of security cooperation in a variety of domains (Caballero-Antony Citation2018).

One of the policy domains where the aim to assert national sovereignty is often said to have curtailed security cooperation is the regional response to piracy and armed robbery against ships (PAR). Regional lines of communication (SLOCs) are crucial for international trade, with 90,000 ships each year passing the Straits of Malacca and Singapore (SOMS), which link the Indian and Pacific Oceans (Pitakdumrongkit Citation2023). Southeast Asia has a long history of PAR: between 1995 and 2013, the region accounted for 41 per cent of all global PAR incidents, resulting in the death of 136 seafarers, twice as many as died around the Horn of Africa in the same time span (McCauley Citation2014). Interstate cooperation frequently remained underdeveloped due to sovereignty-related concerns and disputes. This ‘sovereignty limitation’ sustained areas such as the Sulu & Celebes Sea (S&CS) as ‘an environment in which terrorists and criminals alike can remain hidden from national law enforcement and counterterrorism agencies’ (Rabasa and Chalk Citation2012, 1).

The regional PAR situation has nevertheless improved significantly since the mid-2000s as national capacities and regional cooperation have improved. In June 2005, continued PAR activity in the SOMS led to the Lloyd’s Market Association (LMA)Footnote2 declaring the SOMS a high-risk zone, significantly raising insurance premiums for regionally active members (Rosenberg Citation2010, 86). The LMA’s decision drove subsequent anti-PAR policy measures by regional states that contributed to a relative decline in PAR after the mid-2000s (ReCAAP Citation2020). Since then, regional states have upgraded their maritime domain awareness capabilities, improved cooperation with regional and extra-regional partners, and enhanced their collaboration with private sector actors on data-sharing procedures (Lee Citation2022). With time, PAR has thus become less prevalent and less violent: whilst crew abductions were common between 2017 and 2020, they have effectively been eliminated since then (Lee Citation2022). Despite PAR prevailing as a security challenge, regional anti-PAR policies have proven largely effective.

Insurance and shipping companies remain the immediate victims of PAR in Southeast Asia. Insurers must navigate the impact of PAR on underwriting practices, premium rates, and overall risk management strategies. PAR attacks also mean that shippers incur higher insurance premiums, face delays in delivery, and must partially compensate for ransom payments and lost or damaged shipments (Hastings Citation2020, 6). In the past, PAR in Southeast Asia and insufficient governance responses drove self-help measures by shippers, including the usage of private security actors (PSAs) (Liss Citation2015a). When shipping costs increase, additional expenditures are often redistributed in the form of surging consumer prices, creating ripple effects beyond the industry.

The changing trends in regional PAR and responses thereto, including the role of sovereignty-related concerns, have been well-documented in the literature. Liss (Citation2014) identifies several factors historically driving regional PAR, including coastal impoverishment, overfishing, and corruption, whereas Hastings (Citation2012) discusses the role of organised crime. Although Storey (Citation2022) notes that regional cooperation remains partially ‘constrained by sensitivities over sovereignty’, he has also highlighted that a growing emphasis on greater collaborative efforts has reduced PAR (Storey Citation2008). Similarly, Raymond (Citation2009) and Liss (Citation2015) highlight the policy contributions of the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP), an organisation gathering data on regional PAR. Bateman (Citation2011) investigates the role of different regional platforms and Bentley (Citation2023) studies how China’s growing maritime presence in the region affects cooperative mechanisms. Lee (Citation2022) too documents the recent, largely positive trends in the regional PAR situation.

Whilst the role of PSAs is covered extensively in the literature, the discussion regarding insurers and shippers remains underdeveloped. Liss (Citation2007; Citation2015) highlights that the scope of PSA activity in Southeast Asia has diminished over the past years. In contrast, the role of insurers and shippers has grown: as the 2005 LMA decision indicates, some industry actors can exert policy and regulatory pressures on national governments, potentially leading to a shift in governance practices. Shippers have also begun developing independent best practices to enhance the security of their vessels, cargo, and employees (Hoe Citation2023). Furthermore, governments rely on industry actors to gather data on regional PAR. In this sense, some (but not all) industry actors can exercise political-regulatory agency and are not merely subjected to the regulatory measures taken by public institutions.

This paper provides a qualitative case study analysis examining why the fortunes of PSAs in regional anti-PAR responses have declined while the governance role of insurers and shippers has expanded. The paper argues that expanding governance capacities by regional states have diminished the demand for PSAs, reasserting the role of states as the primary respondents to PAR. Contrastingly, multilateral regulations and public actors have increasingly enlisted insurers and shippers as implementers and developers of shipping-related regulations. They have thus become part of the team ensuring good order at sea, here understood as an environment that ‘ensures the safety and security of shipping and permits countries to pursue their maritime interests and develop their marine resources in accordance with agreed principles of international law’ (Bateman, Ho, and Chan Citation2009, 4). In this context, the growing governance role of insurers and shippers has accompanied the extension of states’ capacity and authority in the maritime security domain, contributing to the decline in demand for PSAs. More broadly, the case of PAR in Southeast Asia demonstrates that the regulatory power relationship between states and private actors is not zero-sum as the growing authority of one side does not necessarily diminish the role of the other.

Some terminological choices are briefly worth noting. Whilst Southeast Asia is primarily affected by armed robbery at sea (ARS) rather than piracy, as will be discussed below, this paper collapses both terms into the concept of piracy and armed robbery against ships (PAR) for the sake of terminological clarity. For brevity purposes, the paper refers to individuals/groups committing PAR as pirates. To allow for a broader perspective on contemporary PAR, the paper also briefly discusses some elements of the Southeast Asian experience(s) in the context of other PAR-prone areas and the role public and private actors play in these geographies.

The article provides key theoretical and empirical insights. Conceptually, it illuminates the complex regulatory relationship between private and public actors in the context of a form of economic globalisation that frequently empowers private actors. Empirically, the paper’s focus on insurers and shippers addresses an understudied part of the literature and demonstrates the need to go beyond state- and PSA-centric analyses of maritime governance mechanisms in contemporary Southeast Asia.

The paper is structured as follows. The first section briefly discusses the legal framework surrounding PAR. The following section examines the PAR policy responses of regional actors in the twenty-first century, finding that although states have reaffirmed their policy control over anti-PAR regimes, insurers and shippers have come to occupy an increasingly crucial role in the emerging regulatory regime. This has contributed to a declining demand for PSAs and the development of an increasingly hybrid regulatory regime.

PAR in Southeast Asia

ARS is the primary form of PAR in Southeast Asia as defined under international law. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) defines piracy as ‘Any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship’ occurring ‘in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State’ (United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea Citation2010). Piracy is thus defined by its occurrence on the high seas, where individual states do not hold sovereignty. Contrastingly, the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) defines ARS as incidents taking place ‘within a State’s internal waters, archipelagic waters and territorial sea’ (Citation2009). The SUA Convention (Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation) further formalises this definition by operationalising ARS as attacks that are executed in maritime areas in which the state holds sovereignty under international law (IMO Citation1988). ARS is significantly more prevalent in Southeast Asia than piracy: between 2007 and 2021, 81 per cent of all incidents reported by the ReCAAP qualified as ARS (Citation2021).

Southeast Asian PAR is historically linked to prevailing developmental challenges. Hastings conceptualises PAR-related activities (plan and execute the attack, flee the scene, sell the stolen goods or ship, negotiate for ransom payments) as being linked to political space (‘an unwillingness or at least inability of law enforcement and political elites to clamp down on their [pirates’] operations’) (Citation2020, 6). In the late 1990s, Indonesian pirates’ attacks in the SOMS increased as the 1997/1998 Asian Financial Crisis severely exacerbated pre-existing socio-economic challenges and instability in Indonesia (Rabasa and Chalk Citation2012, 17), providing locals communities with an incentive (balancing the economic losses incurred by the loss of labour and currency depreciation) and the opportunity (decreased state capacity amid greater political instability) to engage in PAR. The growth in China-bound trade concurrently rendered PAR more profitable (Purbrick Citation2018, 16). Similarly, pirates operating from the Riau Islands had previously struggled to find formal employment on the islands after migrating there in the 1980s (Eklöf Citation2015, 18). Pirates were thus primarily recruited from impoverished coastal communities (Liss Citation2014, 8). Attacks from the late 1990s onwards reflected the pirates’ marginalised socio-economic position as attacks would target easily boardable, slow-moving vessels commanded by lightly or non-armed crews, demanding only a limited degree of operational ‘sophistication’ (Hastings Citation2020, 11). Increased PAR therefore constituted a reaction to broader socio-economic trends.

Regional PAR is a highly cross-jurisdictional challenge, with the case of the Islamist Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) highlighting the importance of regional cooperation. The cross-border nature of the threat is partially a result of the region’s maritime geography. Some key SLOCs are extremely narrow, with only 1,7 miles separating Indonesia and Singapore at the narrowest point of the Singapore Strait (U.S. Energy Information Administration Citation2017). Moreover, the jurisdiction over spaces like the SOMS and the S&CS is shared between regional countries. When cooperation is underdeveloped, PAR can thrive. The Al-Qaeda linked ASG, based on Mindanao in the southern Philippines, staged attacks that frequently involved the killing of crew members and the extortion of ransom payments (Gerdes, Ringler, and Autin Citation2014), including in Malaysian Borneo (Borneo Post Citation2021). A key factor enabling PAR by the ASG was the limited degree of cooperation between Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines in the S&CS, which remained restricted due to sovereignty-related concerns (Storey Citation2018). Today, however, enhanced trilateral cooperation and Filipino counterterrorism operations have largely eroded the group’s scope, leading to a decline in kidnappings and PAR (International Crisis Group Citation2022). In this context, both national policy action and interstate cooperation was necessary to push back against PAR.

Beyond Southeast Asia, modern anti-PAR regimes have become characterised by the cross-jurisdictional cooperation between different state actors in PAR-prone areas and the growing involvement of PSAs in public-private partnerships (PPPs). PSA participation in the Gulf of Aden was actively encouraged by the United States (Spearin Citation2010), reflecting Washington’s openness for market-based security solutions that also shaped the contracting of PSAs in Afghanistan and Iraq (Fitzsimmons Citation2015). PSAs were part of a broader coalition involving state actors and regional organisations that successfully reduced PAR around the Gulf of Aden (Jakobsen Citation2023). As PAR declined, many insurance companies stopped considering large parts of the Indian Ocean as War-Listed Areas, a categorisation that incurs higher insurance premiums (Toucas Citation2023). In both Somalia and Guinea, pirates’ transnational operational scope highlighted the need for effective interstate cooperation (Oyewole Citation2016). In Somalia, the response to PAR also effectively empowered PSAs as cooperation occurred between private and public levels of governance. In Southeast Asia, however, increased regional cooperation has led to a decline in PSA participation.

Responses to PAR in Southeast Asia

In response to the 9/11 attacks, new multilateral regulatory efforts produced measures that curbed pirates’ political space. This reflected a broader securitisation of global means of transportation, including maritime traffic, under the ‘global war on terror’ (Purbrick Citation2018, 15). In 2002, all signatories to the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) were mandated to equip ships exceeding the weight of 300 gross tonnage with an automatic identification system (AIS) that enables the identification and tracking of ships, making it significantly harder to steal and sell stolen vessels (Wolejsza Citation2010). The 2004 introduction of the International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code additionally enhanced security supervision of shipping personnel to combat port-based crime (Mazaheri and Ekwall Citation2009). The reaction to 9/11 thus included the expansion of multilateral regulatory measures that began reducing pirates’ political space.

Growing market and international pressure on key Southeast Asian governments from the mid-2000s onward also saw a growing drive to enhance regional reporting and data-gathering mechanisms on PAR. The largest regional initiative is the ReCAAP, which was founded in 2006 and gathers data on regional PAR via the Singapore-based ReCAAP Information Sharing Centre. The ReCAAP describes itself as ‘the first regional government-to-government agreement to promote and enhance cooperation against piracy and armed robbery against ships in Asia’ (n.d.) and seeks to coordinate law enforcement responses to PAR attacks in real time. All ASEAN states bar Indonesia and Malaysia are signatories to the ReCAAP.Footnote3 The Kuala Lumpur-based IMB Piracy Reporting Centre (IMB PRC), a division of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), is a privately funded data-gathering contact point that sources its data from voluntary industry reporting (ICC Commercial Crime Services Citationn.d.). Like the ReCAAP, the PRC then contacts relevant law enforcement agencies, ideally enabling a swift response. The Information Fusion Centre (IFC) in Singapore further promotes multinational collaboration and conducts capacity and confidence-building measures, especially focusing on data-sharing mechanisms (Ministry of Defense of Singapore Citation2019). The ReCAAP, the IMB, and the IFC all represent initiatives to enhance coordination and build regional capacity to respond to PAR.

ASEAN has focused on facilitating the cooperation between member states and extra-regional actors. During the 2003 ASEAN Regional Forum summit, which involves all ASEAN states as well as extra-regional actors such as Australia, China, Japan, and the US, the summit’s statement on PAR stipulated that regional responses require ‘cooperation and coordination among all institutions concerned […] Effective responses to maritime crime require regional maritime security strategies and multilateral cooperation in their implementation’ (ASEAN Citation2003). Following the summit, ASEAN began hosting meetings between maritime specialists that focused on coordinating law enforcement interactions, intelligence exchanges, and the shared investigation of PAR reports (Rosenberg Citation2010, 88). These measures received support by the Japanese Coast Guard and Japanese civilian agencies, which provided equipment and capacity-building measures to Southeast Asian recipients (Bradford Citation2021, 83). As such, regional responses have been directly supported by extra-regional actors. The ARF’s 2018 Work Plan For Maritime Security, which identified ‘Building Measures based on International and Regional Legal Frameworks, Arrangements and Cooperation’ and ‘Capacity Building and Enhancing Cooperation of Maritime Law Enforcement Agencies in the Region’ as regional priorities, reaffirmed this emphasis on extra-regional involvement. The United States, for instance, provides technical and financial assistance to capacity-building programmes, especially focusing on bolstering intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities (U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Indonesia Citationn.d.). Regional coastguard and maritime law enforcement agencies have generally welcomed the delivery of capacity-building equipment and training (Till Citation2022). Extra-regional support is provided on a primarily bilateral basis and reasserts the role of regional states as the primary respondents to PAR. ASEAN’s function mirrors the role of other regional organisations: in the Gulf of Guinea, ECOWAS also plays a mainly supporting role as anti-PAR patrols are implemented by regional and extra-regional actors (Teixeira and Pinto Citation2022). As such, Southeast Asian states remain the actors developing and implementing anti-PAR measures.

The degree of extra-regional involvement is shaped by the preferences of individual countries, which have frequently sought to reassert exclusive sovereign control over PAR responses. There are instances of openness to extra-regional involvement, most notably in the Philippines, where Filipino forces cooperate with the US Navy to patrol the S&CS (Purbrick Citation2018). In late 2001 Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore also granted permission to the US Navy to escort Afghanistan-bound supply chips through national waters in the SOMS (Richardson Citation2001). More broadly, however, regional states have sought to ensure sovereign control over their maritime jurisdictions. This ambition is particularly visible in the cases of Indonesia and Malaysia. In 2004, when the US proposed the Regional Maritime Security Initiative (RMSI), which would have entailed the posting of American units to Indonesian and Malaysian waters in the SOMS (Cheney-Peters Citation2014), Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur rejected the RMSI on the grounds ‘that the Malacca Strait is not an international strait and the primary responsibility for keeping the area safe for navigation rests on the littoral states’ (Morada Citation2006, 9). One year later, Malaysia also declined the offer of a Japanese naval presence after a Japanese-owned vessel was attacked in the Strait of Malacca (Koh Citation2016). The extent to which regional countries have cooperated with extra-regional actors has thus varied, reflecting different ideational preferences and relations with extra-regional states.

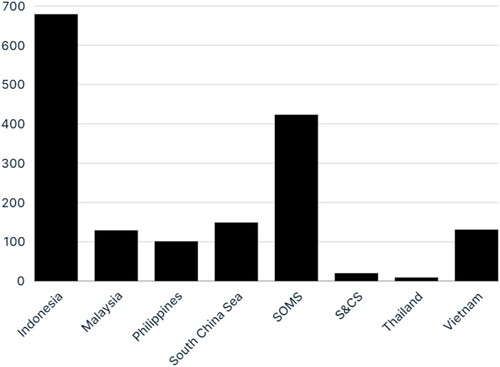

Over time, key littoral states have nevertheless embraced minilateral and sub-regional initiatives, most notably in the SOMS and the S&CS. This sub-regional approach manifests a response to the inherently cross-border character of regional PAR. As indicates, Indonesia remains the most PAR-prone country in the region (see ). However, the de facto numbers for Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore are higher considering that areas such as S&CS and the SOMS are shared between littoral states.

Figure 1. Number of PAR incidents per location, 2004-2022. Source: ReCAAP annual reportsFootnote4.

The anti-PAR surface patrol Malsindo was established by Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore in 2004 and focused on securing the SOMS. In 2006, its mandate was expanded through the provision of air support via the ‘Eyes in the Sky Initiative’ (EITSI) that also included Thai forces. Malsindo was subsequently renamed the Malacca Straits Patrol Network (MSPN) and thereby signalled a shared resolve to curb the political space of pirates. The creation of Malsindo and the eventual formation of the MSPN correlated with the general decline in PAR following the mid-2000s, suggesting that the initiatives contributed to the reduction of pirates’ political space alongside the other regulatory efforts that were launched around the same time. In 2017, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines also formalised the Trilateral Cooperation Agreement (TCA), which facilitates greater regional military cooperation in the S&CS (Mishra and Wang Citation2022). These expanding cooperative mechanisms have reduced abductions and enhanced security in the S&CS (ReCAAP Citation2022). In both cases, initiatives involving key littoral states with a focus on limited geographical spaces proved sufficient to effectively counteract PAR.

Although the case of Malsindo/the MPSN demonstrates the continued role of sovereignty-related issues, the governments partaking in the MSPN have since developed other arrangements to conduct transnational operations. Due to sovereignty-related concerns of national governments, MSPN surface forces partially lack hot pursuit protocols, which prohibits them from pursuing pirates in the jurisdictions of other partaking countries (McCauley Citation2014). Similarly, EITSI overflights lack permission to enter the air space of cooperating states beyond three nautical miles (Liss Citation2012). Some bilateral arrangements have now been struck to close these gaps: in July 2023, the Indonesian Maritime Security Agency, commonly known as Bakamla, seised the Iran-registered tanker MT Arman 114 in Malaysian waters after it had been found to illegally transfer oil to another foreign vessel in Indonesia’s EEZ surrounding the Natuna Islands (Sulaiman and Nangoy Citation2023). The seizure was performed following collaboration between Bakamla and Malaysian authorities in accordance with previously agreed upon hot pursuit protocols (Indonesia Ocean Justice Initiative Citation2023). The existence of sovereignty-related concerns has thus not entirely prevented countries from deepening some cooperative mechanisms.

Cooperation on data-sharing has also improved over time. Malaysia, which hosts the IMB, has not joined the ReCAAP to avoid undermining the role of the IMB whereas Indonesia has cited sovereignty concerns as a reason for not joining the ReCAAP (Hribernik Citation2013). Until the mid-2010s, their lack of participation meant that the ReCAAP ‘achieved little in terms of information sharing’ (von Hoesslin Citation2016, 22). Now, however, both Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur have come to effectively support the ReCAAP by partaking in data-sharing mechanisms and capacity-building practices (Poonawatt Citation2023, 5). Indonesia’s and Malaysia’s de facto participation in the organisation may also help to explain the increase in recorded PAR incidents: as information fusion and analysis capacities have improved, the data reported by organisations like ReCAAP likely remains somewhat static as a larger percentage of fewer events is recorded.

Regional states have additionally invested extensively into their domestic maritime capacities, enhancing their ability to monitor maritime spaces and enforce national legislation. One of the factors motivating these investments has been China’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea, which has driven naval investments in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam (Chang Citation2021). Regional states have also invested into their civilian maritime law enforcement agencies to expand their ability to respond to Chinese incursions and non-traditional challenges, including terrorism, trafficking, illegal fishing, and PAR (Parameswaran Citation2019). As a result, the independent capacity to monitor and control maritime jurisdictions has improved alongside enhanced multilateral mechanisms.

Despite such improvements, sovereignty-related issues remain a factor limiting the scope of regional cooperation. The Spratly Islands archipelago in the South China Sea is disputed between China, Taiwan, and several ASEAN states, and parts of the Spratlys are currently occupied by China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam (Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative Citationn.d.). As such, regional disputes exist between China and ASEAN states as well as between different Southeast Asian countries. Indonesia and Malaysia also have ongoing disputes in the Malacca Strait and the Sulawesi Sea (Yuniar Citation2022) while Manila continues to claim parts of Malaysian Borneo (Parameswaran Citation2016). Sovereignty-related disputes consequently form a set of issues limiting the extent of regional maritime cooperation.

The prevalence of other structural challenges in the region also limits the policy focus on PAR. Land-based criminality, corruption, and uneven development trajectories remain pervasive regional issues that have been exacerbated by the effects of COVID-19. The deprioritisation of PAR is frequently mirrored domestically, including in PAR-prone countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia, neither of which view PAR as a major security priority (Poonawatt Citation2023). As a result, domestic policy action is often limited. Pirates detained in Indonesia, for instance, are prosecuted under sections of the Criminal Code rather than more specific PAR-related legislation that is in place in, for example, Singapore, and are mostly imprisoned for relatively short periods of time (Fenton and Chapsos Citation2019, 229). Domestic frameworks and priorities here remain the key factors shaping states’ responses to PAR. As resources remain finite and political priorities are frequently placed elsewhere, key states often do not securitise PAR to a degree that would invoke a more immediate, coordinated, and comprehensive security response.

Over time, Southeast Asian countries have enhanced their regional cooperation on PAR, for instance in the context of the MSPN and the TCA. Although the effects of specific anti-PAR policies are difficult to isolate given that major international regulatory efforts were launched around the same time, the combination of regulatory changes, subregional initiatives, and expanding domestic capacities correlate with a decline in PAR. Sovereignty-related concerns have nevertheless partially limited the scope of cooperation. Although PAR is unlikely to be fully eliminated as a challenge if the structural factors driving PAR are not addressed more comprehensively, the progress made by subregional initiatives offers wider insights on what could contribute to more effective policy models: a focus on subregional approaches with limited aims and buy-in from key regional actors. Whilst the regional response to PAR appears to reaffirm the conclusion that regional countries continue to shield their sovereign regulatory control, a closer examination of the changing role of private sector actors partially complicates this analysis.

The evolving role of private sector actors

Private security actors (PSAs)

The governance role of PSAs has gradually expanded over the course of the twenty-first century. Since the end of the Cold War, PSAs ‘are increasingly being recognised by governments, civil societies and international organisations as legitimate actors that can have a positive impact on international security’ (Kinsey Citation2006, 4). This privatisation of security, Abrahamsen and Williams write, ‘is part of a broader rearticulation of the state that reworks the distinctions between the public and the private, as well as the global and the local’ (Citation2011, 171). The subsequently developed global security assemblages, they propose, are constituted by ‘complex hybrid structures of actors, knowledge, technologies, norms, and values that stretch across national boundaries but operate in national settings’. The reconfiguration of security governance capacities follows a neoliberal logic that espouses the ‘commodification of security, where security is a commodity to be bought and sold in a competitive marketplace rather than a public good provided by the state’ (Abrahamsen and Leander Citation2015, 4). In a neoliberalised global economy, PSAs have partially obtained governance functions that have been commonly associated with the Westphalian state.

To avoid the blurry lines between private military contractors (PMCs) and private security contractors (PSCs), this article simply categorises them as PSAs. Although PMCs and PSCs are often argued to fulfil different operational functions for their employers, as argued by Richards and Smith (Citation2007), these operational distinctions are often difficult to discern and maintain in practice (Bures and Cusumano Citation2021). To account for the practical ambivalence surrounding the mandates of private contractors, the paper broadly categorises them as PSAs.

The PSA sector is frequently poorly regulated and has been criticised for aggravating rather than ameliorating insecurity. National agencies mandated to regulate PSAs have often been underfunded or captured by industry actors, and many PSAs are believed to be operating outside any effective regulatory framework (Shearing and Stenning Citation2015, 144–145). Regulatory concerns have been endemic, with major discussions in the United States being sparked by the 2007 killing of Iraqi civilians by personnel of the PSA Blackwater, now rebranded as Academi (Fitzsimmons Citation2015, 101). Today, the Wagner Group operates as a quasi-state force for the Russian military in a series of conflicts throughout the world and is responsible for repeated human rights violations (Fasinotti Citation2022). Leander also finds that security privatisation has negatively affected ‘weak (or non-existent) public security orders’ in fragile conflict environments as ‘the market for force drains resources from public security establishments and undermines their legitimacy, hence making contestation both from the inside and the outside more likely’ (Citation2005, 618). As such, an expanding governance role of PSAs can reflect and reinforce lacking and/or declining state capacities.

PSA activity around the SOMS began increasing in the early 2000s as PAR attacks grew in frequency. Framing their services in the context of suspected terrorist threats in the SOMS and fears of the collusion between terrorist organisations and an Acehnese separatist movement in Sumatra, PSAs would either staff their personnel on merchant vessels or, in some cases, provide their own ships as escorts (Liss Citation2015a). Further, partially armed PSAs would provide training, be present to deter attack on offshore installations, and engage in ransom negotiations and rescue operations (Liss Citation2007). At the time, the growing usage of PSAs by actors in the shipping industry highlighted that ‘government authorities and agencies are often unable to provide security, training, and technical security equipment on the scale that is sought by the maritime industry since September 11’ or was required under the post-9/11 regulatory frameworks (Liss Citation2007, 13). Besides the delivery of risk analysis assessments, PSAs therefore provided ‘services that have traditionally been in the realm of militaries and law enforcement agencies’ (Liss Citation2014, 174). In this context, the strategic vacuum generated by states’ governance shortcomings motivated self-help measures by industry actors, namely the hiring of PSAs. PSAs thus began to partially occupy governance functions traditionally performed by states.

By the mid-2000s, most regional states sought to clamp down on PSAs and reassert sovereign control over maritime security provision. In 2005, the Singapore-based newspaper The Straits Times released several articles on the presence of armed PSAs in Indonesian and Malaysian waters, evoking an outcry in both countries, with Malaysian authorities warning that they would criminally try armed PSA employees detained in Malaysian waters (Liss Citation2012). Although PSA activity often continued regardless as local officials were paid off (Liss Citation2007), top-level politicians in Indonesia and Malaysia evidently sought to signal the reassertion of state control. Today, PSA regulations in Indonesia and Malaysia prohibit armed PSAs on vessels within their jurisdiction whereas laws in the Philippines and Singapore are laxer (Cheney-Peters Citation2014; Liss Citation2014a). Notably, the policy emphasis has been on restricting the presence of foreign PSAs rather than eliminating the private security industry as such, with domestic private security sectors generally growing throughout Southeast Asia (Hernandez Citation2017). Although there likely remains a disconnect between PSA regulations and their implementation, the regulatory frameworks in key littoral countries have frequently focused on reasserting sovereign control by formally restricting PSA activity.

As such, the drop in PSA activity in Southeast Asia must be viewed as the result of improved regional maritime governance capacities rather than changes in regulation. As PAR incidents began declining following the mid-2000s due to the expansion of anti-PAR policy measures, the market demand for PSAs dried up (Liss Citation2015a). While it is unclear whether anti-PSA regulations practically hampered the abilities of PSAs to provide their services, concurrently improving governance and the associated decline of PAR reduced the market demand for PSAs. Another indicator is the decline in violent attacks noted by Lee (Citation2022), which further reduces companies’ incentive to hire PSAs. Furthermore, the limited size of key SLOCs such as the SOMS makes these spaces easier to patrol for states with growing maritime capabilities (Cheney-Peters Citation2014). As national enforcement capacities and regional cooperation have improved, the role of PSAs has declined. As such, states have reaffirmed their role as the primary respondents to PAR at the expense of PSAs.

More broadly, states’ frequent unwillingness to cede the monopoly on violence to non-state actors is not unique to Southeast Asia. The PSA ESC Global Security notes that countries in the Gulf of Guinea ‘do not allow private guards and weapons to be deployed, instead requiring the use of local Navy personnel’ (n.d.). During anti-PAR operations in the Gulf of Somalia, different European countries exhibited different approaches toward the use of PSAs in the protection of their merchant fleets. These approaches were shaped by divergent attitudes toward PSAs, including a normative preference for a national monopoly on violence over market-based solutions (Cusumano and Ruzza Citation2018, 81). The divergent approaches observable in Southeast Asia mirror these ideational differences and speak to a frequent unwillingness of public actors to delegate authority.

Ultimately, the regulatory power dynamic between states and private actors in the case of PSAs was one-sided and operated according to a zero-sum logic. Demand for PSAs grew in the early 2000s as a form of self-help as PAR increased and states appeared largely incapable and/or unwilling to effectively curtail PAR. However, the presence of non- or under-regulated PSA staff in a state’s maritime jurisdiction broadly undermined ‘security and government control of violence’ (Liss Citation2014a, 175), incentivising governments to reassert control over PSAs and strengthen their delivery of security as a public good. As Southeast Asian countries bolstered their capacities, the leverage of and demand for PSAs diminished. The unwillingness of many regional states to delegate security-related responsibilities to PSAs here mirrors the behaviour and preferences of other states in other geographical contexts. Whilst PSAs could potentially contribute to maintaining good order at sea if sufficiently regulated, PSA activity can also hollow out the state’s capacities, reducing its long-term ability to independently provide security as a public good. The formal pushback against PSAs as well as the states’ improved governance efforts and capabilities therefore formally and practically reaffirmed states’ sovereign control.

Insurance and shipping companies

Insurers and shippers have traditionally operated as beneficiaries of state-led maritime security orders and largely continue to rely on state actors to provide for navigable SLOCs. These industry actors depend on the continued navigability of SLOCs to deliver their products and services. As such, disruptions in shipping through clogged-up bottlenecks (for instance caused by PAR or international tensions) present an immediate risk to their commercial profitability. Growing maritime insecurity can prompt insurers to raise premiums, thus requiring shippers to focus on less volatile but less cost-effective shipping routes, which raises operational costs (Bensassi and Martínez-Zarzoso Citation2011). PAR also can drive an increase in expenditures on guards and defensive equipment while curtailing revenues by delaying shipments and damaging the company’s ship and cargo (Hoe Citation2023; Stamer, Yang, and Sandkamp Citation2022). Given that states remain the primary respondents to PAR, insurers and shippers have an interest in lobbying public stakeholders to ensure freedom of navigation. In response to missile attacks by the Yemeni Houthi rebels on commercial ships passing through the Red Sea in late 2023, for instance, a statement by the international shipping association BIMCO read that ‘BIMCO believes nation states must collaborate to remove the current threat to international shipping and, if necessary, neutralise the threat by military means within the boundaries of international law’ (Fraende Citation2023). In this context, insurers and shippers have long been the beneficiaries of state-led maritime security orders.

As we have seen, however, perceived public governance failures can drive industry actors to take self-help measures, for instance by contracting PSAs. For firms in the insurance and reinsurance market, the focus on proactively identifying and responding to geopolitical trends and pricing these trends into the firms’ models was directly linked with the 9/11 attacks, during which sectoral firms incurred exorbitant financial losses (Dua Citation2019). The decision of the LMA to raise insurance premiums in response to PAR attacks in the SOMS can thus be viewed as aiming to manage and minimise corporate risk. These self-help measures can then have security effects, for instance when insurers support the hiring of insufficiently regulated and legally unaccountable PSAs by shipping companies.

The dynamics between states and insurers and shippers have changed over time as the shifting regulatory frameworks after 9/11 expanded the maritime security roles of private actors. The ISPS Code, for instance, requires shipping companies to assign Company and Ship Security Officers to develop and enact security plans for the vessels (Bradford and Edwards Citation2022). AIS-linked data generated on ships also allows national agencies to detect potentially illegal activities by vessels, incentivising shippers to enhance the monitoring of vessel activities (Collyns Citation2022). Since 2003, shipping companies must further implement the Seafarers’ Identity Documentation Convention of the International Labour Organisation, which registers seafarers in a biometric identification system for security screening purposes (Bateman, Ho, and Chan Citation2009). Additionally, the Ship Security Alert Systems (SSAS), mandated as part of the SOLAS Convention, allows ship operators to discretely contact public authorities and/or previously contracted PSAs (Hoe Citation2023). As discussed, the data-sharing activities of the ReCAAP also depend on shipping firms feeding them data. While these regulations reasserted state control over industry actors, for instance by allowing state authorities to board a ship operating under another state’s flag if there were concerns that the SUA Convention was being violated by the ship or its staff (Hoe Citation2023), the PAR-linked governance mechanisms have become increasingly tied to the close cooperation between state and industry actors. In this context, shipping regulations have enlisted industry actors as maritime security stakeholders that now actively partake in anti-PAR governance regimes. Crucially, the increasingly central role of insurers and shippers did not coincide with a delegation of governance responsibilities per se as PSAs were not made part of this emerging regulatory coalition.

This regulatory alignment is also strengthened by some private actors reshaping industry regulations and practices in a way that benefits the interests of states. Take the Best Management Practices (BMP) published by BIMCO since 2009, which aim to deter PAR attacks and cover ‘protection measures as well as reporting procedures for ships and their crew, as well as shipping companies’ (Hoe Citation2023). The BMP are now adopted by most shipping companies operating in the SOMS (Hoe Citation2023). This exemplifies a process of self-governance, driven by the motivation to maintain profitability and manage risk. Alongside the recent spur in cybersecurity legislation, industry associations such as the International Chamber of Shipping (Citation2021) have also published best cybersecurity practices for their members. The important point here is not that industry actors self-regulate (as they have a commercial interest in bolstering their sectoral resilience and profitability) but that they do so in a manner that broadly complements the policy agenda of multilateral organisations and (most) national governments. Industry actors therefore do not simply ‘receive’ regulatory measures from public actors but independently shape norms and regulations within the industry, which in turn benefits’ states capacities to respond to PAR. This process reflects and reinforces the transition of insurers and shippers from beneficiaries to parts of the team creating good order at sea.

However, the regulatory relationship between public and private actors is not one-sided as insurers and shippers can exert pressure on governments to pursue policies that benefit industry actors. This is effectively what transpired when the LMA raised premiums for companies operating in the SOMS in June 2005. Although Malsindo had been launched prior to the LMA announcement, the timing of the commencement of the EITSI in September 2005 suggests that the private market pressure generated sufficient grounds for the Malsindo countries to ramp up their efforts and at least be perceived as combatting PAR (Raymond Citation2009). Domestic PAR legislations also partially changed in response, leading to the formation of Indonesian and Malaysian maritime law enforcement units dedicated to securing the Malacca Strait in July 2005 (Song Citation2007). Industry actors can thus develop a feedback loop that provides policy inputs to public stakeholders who can then (potentially) transform these inputs into a form of policy output. Through exerting pressure, industry actors can lobby governments to adopt practices and invoke regulatory changes that produce wider governance effects. Importantly, the growing role of insurers and shippers has not meant that states have become less significant. Instead, growing state capacities have been accompanied by a more central governance function for insurers and shippers. This dynamic defies the zero-sum mechanism that played out in the relation between regional states and PSAs, where growing state capacity effectively eliminated demand for PSAs.

The case of insurers and shippers differs notably from that of PSAs as the growing capacity of states has not led to a reduced role for these industry actors but has, in fact, actively promoted their role as governance actors. This development speaks to a larger dynamic in a globalised economy in which private entities are not solely subjects to regulatory and governance developments but occupy governance functions in their own right (May Citation2015, 2). Private entities now ‘play a fundamental role in providing public goods and exercise powers commonly associated with formal state institutions’ (Barkan Citation2015, 1). However, the changing role of some industry actors has not simultaneously reduced the role of national governments. As economic globalisation has partially rearranged regulatory powers, sovereignty has ultimately become more layered and hybridised, illustrating that the redistribution of regulatory powers in the relationship between states and private actors is not zero-sum.

Conclusion

The extant literature on PAR in Southeast Asia has mainly concentrated on the role of states and PSAs while insufficiently analysing the increasingly crucial role of insurers and shippers. This paper has sought to address this gap. The paper has found that although Southeast Asian countries are commonly viewed as jealous defenders of their sovereignty, the case of regional PAR demonstrates that the reassertion of sovereign control over anti-PAR measures has not been diametrically opposed to a growing governance role of some private sector actors. However, the growing governance role of the private sector is isolated to some firms and sectors rather than the private sector as a whole. In this context, the role of PSAs has declined as regional capabilities have grown. While sovereignty-related concerns partially limit the scope of interstate cooperation, the regional pushback against PAR has been specifically effective in cases where initiatives have been subregional and defined by a limited geographical scope, limited objectives, and buy-in from key regional public stakeholders. These initiatives can provide a larger blueprint for how PAR-linked cooperative mechanisms could be structured going forward, both in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

Although some of the factors shaping regional PAR possess a necessarily distinct Southeast Asian character, some broader conclusions regarding the nature of contemporary anti-PAR regimes can be drawn. Whilst national authorities remain the primary actors implementing anti-PAR responses, industry actors, most notably insurance and shipping companies, have themselves emerged as governance actors by exerting pressure on national governments, collaborating with government initiatives, and developing their own practices of responding to PAR. The expanding capacities of some industry actors and states have here developed in tandem rather than in opposition to one another. In Southeast Asia, this trend does not track with the activities of PSAs, which have been sidelined as governance has improved. However, the demand for PSA activity may be greater in settings characterised by less state capacity and a less pronounced international focus. Ultimately, the process of rearranging governance capabilities and responsibilities between public actors and different private economic agents therefore remains fluid and contested.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Aaron Magunna

Aaron Magunna is a PhD student at the University of Queensland in Australia. His research focuses on how countries in Asia respond to China–US competition by adapting their security, trade, and technology policies. Aaron holds a Master's degree in International Relations from the University of Groningen in the Netherlands and worked in the think tank sector before re-entering academia.

Notes

1 ASEAN has ten members: Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, and Brunei. Timor-Leste was given in-principle admission to the organisation in late 2022.

2 The LMA is a London-based insurance and reinsurance market that does not provide insurance itself but regulates components of the insurance market for its members, for instance by raising insurance premiums for markets characterized by a high degree of economic volatility.

3 The non-Southeast Asian signatories to ReCAAP are Australia, Bangladesh, China, Denmark, Germany, India, Japan, South Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, Sri Lanka, the UK, and the US.

4 No data available for the S&CS between 2004 and 2012.

References

- Abrahamsen, Rita, and Anna Leander. 2015. “Introduction.” In Routledge Handbook of Private Security Studies, edited by Rita Abrahamsen, and Anna Leander, 1–7. New York: Routledge.

- Abrahamsen, Rita, and Michael C. Williams. 2011. “Security Privatization and Global Security Assemblages.” The Brown Journal of World Affairs 18 (1): 171–180. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24590788.

- ASEAN. 2003. “ARF Statement on Cooperation Against Piracy and Other Threats to Security.” https://asean.org/arf-statement-on-cooperation-against-piracy-and-other-threats-to-security/.

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. N.d. “Occupation and island building.” https://amti.csis.org/island-tracker.

- Barkan, Joshua. 2015. Corporate Sovereignty: Law and Government Under Capitalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bateman, Sam. 2011. “Solving the “Wicked Problems” of Maritime Security: Are Regional Forums up to the Task?” Contemporary Southeast Asia 33 (1): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1355/cs34-1a.

- Bateman, Sam, Joshua Ho, and Jane Chan. 2009. “Good Order at Sea in Southeast Asia.” S. Rajaratnam School for International Studies. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/PR090427_Good_Order_at_Sea_in_SEA.pdf.

- Bensassi, Sami, and Immaculada Martínez-Zarzoso. 2011. “How Costly is Modern Maritime Piracy for the International Community?” Ibero-America Institute for Economic Research. https://ideas.repec.org/p/got/iaidps/208.html.

- Bentley, Scott. 2023. The Maritime Fulcrum of the Indo-Pacific: Indonesia and Malaysia Respond to China’s Creeping Expansion in the South China Sea. Newport: Naval War College Press.

- Borneo Post. 20 August 2021. “Abu Sayyaf members shot dead in Sandakan planned kidnapping for ransom, says Sabah CP.” https://www.theborneopost.com/2021/08/20/abu-sayyaf-members-shot-dead-in-sandakan-planned-kidnapping-for-ransom-says-sabah-cp/.

- Bradford, John. 2021. “Japanese Naval Activities in Southeast Asian Waters: Building on 50 Years of Maritime Security Capacity Building.” Asian Security 19 (1): 79–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14799855.2020.1759552.

- Bradford, John, and Scott Edwards. 2022. “Evolving Stakeholder Roles in Southeast Asian Maritime Security.” S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/idss/ip22058-evolving-stakeholder-roles-in-southeast-asian-maritime-security/#.ZBRwe3bMK3B.

- Bures, Oldrich, and Eugenio Cusumano. 2021. “The Anti-Mercenary Norm and United Nations’ use of Private Military and Security Companies: From Norm Entrepreneurship to Organized Hypocrisy.” International Peacekeeping 28 (4): 579–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2020.1869542.

- Caballero-Antony, Mely. 2018. Negotiating Governance on Non-Traditional Security in Southeast Asia and Beyond. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Chang, Felix. K. 2021. “Southeast Asian Naval Modernization and Hedging Strategies.” The Asan Forum. https://theasanforum.org/southeast-asian-naval-modernization-and-hedging-strategies/.

- Cheney-Peters, Scott. 2014. “Whither the Private Maritime Security Companies of South and Southeast Asia? (Part 2)” Center for International Maritime Security. https://cimsec.org/part-2-whither-pmscs-south-southeast-asia/.

- Collyns, Dan. 2022. At Least 6% of Global Fishing ‘Probably Illegal’ as Ships Turn off Tracking Devices. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/nov/02/at-least-6-percent-global-fishing-likely-as-ships-turn-off-tracking-devices-study.

- Cusumano, Eugenio, and Stefano Ruzza. 2018. “Security Privatisation at sea: Piracy and the Commercialisation of Vessel Protection.” International Relations 32 (1): 80–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117817731804.

- Dua, Jatin. 2019. “Hijacked: Piracy and Economies of Protection in the Western Indian Ocean.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 61 (3): 479–507. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417519000215.

- Eklöf, Stefan. 2015. Pirates in Paradise: A Modern History of Southeast Asia’s Maritime Marauders. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

- ESC Global Security. N.d. “Maritime Security in the Gulf of Guinea.” https://www.escgs.com/services/maritime-security/security-in-west-africa.

- Fasinotti, Federica S. 2022. “Russia’s Wagner Group in Africa: Influence, Commercial Concessions, Rights Violations, and Counterinsurgency Failure.” Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2022/02/08/russias-wagner-group-in-africa-influence-commercial-concessions-rights-violations-and-counterinsurgency-failure/.

- Fenton, Adam J., and Ioannis Chapsos. 2019. “Prosecuting Pirates: Maritime Piracy and Indonesian Law.” Australian Journal of Asian Law 19 (2): 217–232.

- Fitzsimmons, Scott. 2015. Private Security Companies During the Iraq War: Military Performance and the use of Deadly Force. London and New York: Routledge.

- Fraende, Mette K. 2023. “BIMCO calls for immediate end of attacks on international shipping.” BIMCO. https://www.bimco.org/news/priority-news/20231218-attacks.

- Gerdes, Luke M., Kristine Ringler, and Barbara Autin. 2014. “Assessing the Abu Sayyaf Group's Strategic and Learning Capacities.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 37 (3): 267–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2014.872021.

- Hameiri, Shahar, and Lee Jones. 2015. Governing Borderless Threats: Non-Traditional Security and the Politics of State Transformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hastings, Justin V. 2012. “Understanding Maritime Piracy Syndicate Operations.” Security Studies 21 (4): 683–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2012.734234.

- Hastings, Justin V. 2020. “The Return of Sophisticated Maritime Piracy to Southeast Asia.” Pacific Affairs 93 (1): 5–30. https://doi.org/10.5509/20209315.

- Hernandez, Carolina G. 2017. “Mapping Security Provision in Southeast Asia.” Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/13556.pdf/.

- Hoe, Toh Keng. 2023. “The Maritime Security Roles of the Shipping Community in Southeast Asia.” S. Rajaratnam School for International Studies. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/idss/ip23002-the-maritime-security-roles-of-the-shipping-community-in-southeast-asia/.

- Hribernik, Miha. 2013. “Countering Maritime Piracy and Robbery in Southeast Asia.” European Institute of Asian Studies. https://www.eias.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/EIAS_Briefing_Paper_2013-2_Hribernik.pdf.

- ICC Commercial Crime Services. N.d. “IMB Piracy Reporting Centre.” https://www.icc-ccs.org/piracy-reporting-centre.

- IMO. 1988. “Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Maritime Navigation.” https://treaties.un.org/doc/db/terrorism/conv8-english.pdf.

- IMO. 2009. “Code of Practice for the Investigation of the Crimes of Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships.” https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/Security/Documents/A.1025.pdf.

- Indonesia Ocean Justice Initiative. 2023. “IOJI Appreciates the Arrest of Iran's Super Tanker Vessel by Bakamla RI.” https://oceanjusticeinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/PR_IOJI-Appreciates-the-Arrest-of-Irans-Super-Tanker-Vessel-by-BAKAMLA-RI_ENG.pdf.

- International Chamber of Shipping. 2021. “The Guidelines on Cyber Security Onboard Ships.” https://www.ics-shipping.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/2021-Cyber-Security-Guidelines.pdf.

- International Crisis Group. 2022. “Addressing Islamist Militancy in the Southern Philippines.” https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/philippines/addressing-islamist-militancy-southern-philippines.

- Jakobsen, Peter V. 2023. “Somali Piracy, Once an Unsolvable Security Threat, has Almost Completely Stopped. Here’s why.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/somali-piracy-once-an-unsolvable-security-threat-has-almost-completely-stopped-heres-why-213872.

- Jones, Lee. 2009. “ASEAN’s Unchanged Melody? The Theory and Practice of ‘Non-Interference’ in Southeast Asia.” Durham University. https://www.dur.ac.uk/resources/ibru/conferences/sos/lee_jones_paper.pdf.

- Kinsey, Christopher. 2006. Corporate Soldiers and International Security: The Rise of Private Military Companies. New York: Routledge.

- Koh, Collin S. L. 2016. “The Malacca Strait Patrols: Finding Common Ground.” S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/CO16091.pdf.

- Leander, Anna. 2005. “The Market for Force and Public Security: The Destabilizing Consequences of Private Military Companies.” Journal of Peace Research 42 (5): 605–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343305056237.

- Lee, Yin Mui. 2022. “Piracy and armed robbery as amm evolving threat to Southeast Asia’s Maritime Security.” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. https://amti.csis.org/piracy-as-an-evolving-threat-to-southeast-asias-maritime-security/.

- Liss, Carolin. 2007. “The Privatisation of Maritime Security - Maritime Security in Southeast Asia: Between a rock and a hard place?” Murdoch University. https://researchportal.murdoch.edu.au/esploro/outputs/workingPaper/The-Privatisation-of-Maritime-Security–/991005544865607891.

- Liss, Carolin. 2012. “Commercial Anti-Piracy Escorts in the Malacca Strait.” In Maritime Private Security: Market Responses to Piracy, Terrorism and Waterborne Security Risks in the 21st Century, edited by Claude Berube, and Patrick Cullen. New York: Routledge.

- Liss, Carolin. 2014. “Assessing Contemporary Maritime Piracy in Southeast Asia: Trends, Hotspots, and Responses.” Hessische Friedens- und Konfliktforschung. https://www.hsfk.de/fileadmin/HSFK/hsfk_downloads/prif125.pdf.

- Liss, Carolin. 2014a. “Security Sector Reform in Southeast Asia: The Role of Private Security Providers.” In Security Sector Reform in Southeast Asia: From Policy to Practice, edited by Felix Heiduk, 159–180. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Liss, Carolin. 2015a. “PMSCS in Maritime Security and Anti-Piracy Control.” In Routledge Handbook of Private Security Studies, edited by Rita Abrahamsen, and Anna Leander, 61–70. New York: Routledge.

- Liss, Carolin. 2015. “Piracy in Southeast Asia: Trends, hot Spots and Responses.” In Piracy in Southeast Asia: Trends, Hot Spots and Responses, edited by Caroline Liss, and Ted Biggs. New York: Routledge.

- May, Christopher. 2015. Global Corporations in Global Governance. New York and London: Routledge.

- Mazaheri, Arsham, and Daniel Ekwall. 2009. “Impacts of the ISPS Code on Port Activities: A Case Study on Swedish Ports.” World Review of Intermodal Transportation Research 2 (4): 326–342. https://doi.org/10.1504/WRITR.2009.026211.

- McCauley, Adam. 2014. “The Most dangerous waters in the world.” Time. https://time.com/piracy-southeast-asia-malacca-strait/.

- Ministry of Defense of Singapore. 2019. “Fact Sheet on Information Fusion Centre (IFC) and Launch of IFC Real-Time Information-Sharing System (IRIS.” https://www.mindef.gov.sg/web/portal/mindef/news-and-events/latest-releases/article-detail/2019/May/14may19_fs.

- Mishra, Rahul, and Peter B. M. Wang. 2022. “Middle-Power Security Agreements Help Maintain Regional Maritime Order.” Australian Strategic Policy Institute. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/middle-power-security-agreements-help-maintain-regional-maritime-order/.

- Morada, Noel M. 2006. “Regional Maritime Security Initiatives in the Asia Pacific: Problems and Prospects for Maritime Security Cooperation.” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/projekt_papiere/Morada_ks.pdf.

- Oyewole, Samuel. 2016. “Suppressing Maritime Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea: The Prospects and Challenges of the Regional Players.” Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs 8 (2): 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/18366503.2016.1217377.

- Parameswaran, Prashanth. 2016. “Malaysia's Najib Vows to Defend Sabah Sovereignty in Duterte Meeting.” The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2016/08/malaysias-najib-vows-to-defend-sabah-sovereignty-in-duterte-meeting/.

- Parameswaran, Prashanth. 2019. “Managing the Rise of Southeast Asia’s Coast Guards.” The Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/2019-02_managing_the_rise_of_southeast_asias_coast_guards.pdf.

- Pitakdumrongkit, Kaewkamol. 2023. “Geoeconomic Crossroads: The Strait of Malacca’s Impact on Regional Trade.” The National Bureau of Asia Research. https://www.nbr.org/publication/geoeconomic-crossroads-the-strait-of-malaccas-impact-on-regional-trade/.

- Poonawatt, Kornwika. 2023. “Multilateral Cooperation Against Maritime Piracy in the Straits of Malacca: From the RMSI to ReCAAP.” Marine Policy 152: 105628–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105628.

- Purbrick, Martin. 2018. “Pirates of the South China Seas.” Asian Affairs 49 (1): 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/03068374.2018.1416010.

- Rabasa, Angel, and Peter Chalk. 2012. “Non-Traditional Threats and Maritime Domain Awareness in the Tri-Border Area of Southeast Asia: The Coast Watch System of the Philippines.” RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/occasional_papers/2012/RAND_OP372.pdf.

- Raymond, Catherine Z. 2009. “Piracy and Armed Robbery in the Malacca Strait.” Naval War College Review 62 (3): 1–12. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol62/iss3/4.

- ReCAAP. 2020. “Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships in Asia: January-March 2020.” https://www.recaap.org/resources/ck/files/reports/quarterly/ReCAAP%20ISC%201st%20Quarter%202020%20Report.pdf.

- ReCAAP. 2021. “Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia: January to December 2021.” https://www.recaap.org/resources/ck/files/reports/annual/ReCAAP%20ISC%20Annual%20Report%202021.pdf.

- ReCAAP. 2022. “Update of ReCAAP ISC Advisory - Cases of Abduction of Crew from Ships in the Sulu-Celebes Seas.” https://www.recaap.org/resources/ck/files/alerts/2022/Update%20of%20ReCAAP%20ISC%20Advisory%20-%20Cases%20of%20Abduction%20of%20Crew%20from%20Ships%20in%20the%20Sulu-Celebes%20Seas%20(15%20Sep%2022).pdf.

- ReCAAP. N.d. “About ReCAAP Information Sharing Centre.” https://www.recaap.org/about_ReCAAP-ISC.

- Richards, Anna, and Henry Smith. 2007. “Addressing the Role of Private Security Companies Within Security Sector Reform Programmes.” Saferworld. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/39540/PSC_report.pdf.

- Richardson, Michael. 2001. “Supply Carriers Are Vulnerable in Strait of Malacca, Admiral Says: U.S. Escorts Ships to the War Zone.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/12/03/news/supply-carriers-are-vulnerable-in-strait-of-malacca-admiral-says-us.html.

- Rosenberg, David. 2010. “The Political Economy of Piracy in the South China Sea.” In In Piracy and Maritime Crime: Historical and Modern Case Studies, edited by Bruce A. Elleman, Andrew Forbes, and David Rosenberg. Newport: Naval War College.

- Shearing, Christopher, and Philip Stenning. 2015. “The Privatization of Security: Implications for Democracy.” In Routledge Handbook of Private Security Studies, edited by Rita Abrahamsen, and Anna Leander, 140–148. New York: Routledge.

- Song, Yann-huei. 2007. Security in the Strait of Malacca and the Regional Maritime Security Initiative: Responses to the US Proposal.” International Law Studies 83: 97–156. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1163&context=ils.

- Spearin, Christopher. 2010. “Against the Current? Somali Pirates, Private Security, and American Responsibilization.” Contemporary Security Policy 31 (3): 553–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2010.521708.

- Stamer, Vincent, Shuyao Yang, and Alexander Sandkamp. 2022. “The rum is Gone! The Impact of Maritime Piracy on Trade and Transport.” Centre for Economic Policy Research. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/rum-gone-impact-maritime-piracy-trade-and-transport.

- Storey, Ian. 2008. “Securing Southeast Asia’s Sea Lanes: A Work in Progress.” Asia Policy 1: 95–128. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24904662.

- Storey, Ian. 2018. “Trilateral Security Cooperation in the Sulu-Celebes Seas: A Work in Progress.” ISEAS -Yusof Ishak Institute. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/[email protected].

- Storey, Ian. 2022. “Piracy and the Pandemic: Maritime Crime in Southeast Asia, 2020-2022.” Fulcrum. https://fulcrum.sg/piracy-and-the-pandemic-maritime-crime-in-southeast-asia-2020-2022/.

- Strangio, Sebastian. 2020. In the Dragon's Shadow: Southeast Asia in the Chinese Century. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Sulaiman, Stefano, and Fransiska Nangoy. 2023. “Indonesia Seizes Iranian-Flagged Tanker Suspected of Illegal Oil Transfer.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/indonesia-seizes-iranian-flagged-tanker-suspected-illegal-transshipment-oil-2023-07-11.

- Suzuki, Sanae. 2019. “Why is ASEAN not Intrusive? Non-Interference Meets State Strength.” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies 8 (2): 157–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2019.1681652.

- Teixeira, Carlota A., and Jamie Nogueira Pinto. 2022. “Maritime Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea.” GIS. https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/piracy-gulf-guinea/.

- Till, Geoffrey. 2022. “Order at Sea: Southeast Asia’s Maritime Security.” Lowy Institute. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/order-sea-southeast-asia-s-maritime-security.

- Toucas, Vanessa. 2023. “Indian Ocean Removed from the Piracy High Risk Area from 1st of January 2023.” Latitude Brokers. https://latitudebrokers.com/indian-ocean-removed-from-the-piracy-high-risk-area-from-1st-january-2023/.

- United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea. 2010. “Legal Framework for the Repression of Piracy Under UNCLOS.” https://www.un.org/depts/los/piracy/piracy_legal_framework.htm.

- U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Indonesia. N.d. “Fact Sheet: U.S. Building Maritime Capacity in Southeast Asia.” https://id.usembassy.gov/our-relationship/policy-history/embassy-fact-sheets/fact-sheet-u-s-building-maritime-capacity-in-southeast-asia/.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. 2017. “The Strait of Malacca, a key oil trade chokepoint, links the Indian and Pacific Oceans.” https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=32452.

- von Hoesslin, Karsten. 2016. “The Economics of Piracy in South East Asia.” Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/global-initiative-economics-of-se-asia-piracy-may-2016.pdf, p. 22.

- Wolejsza, Piotr. 2010. “Data Transmission in Inland AIS System.” International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation 4 (2): 179–182.

- Yuniar, R. W. 2022. “Indonesia's Land and Maritime Border Disputes with Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam.” South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/explained/article/3163035/indonesias-land-and-maritime-border-disputes-malaysia.