Abstract

Although the relevance of emotions for motivating climate change action is acknowledged in research, it lacks recommendation how to include emotions in Climate Change Education (CCE). This study draws on selected theories of emotions (the control-value theory according to Schutz and Pekrun (Citation2007) and the wheel of emotions according to Plutchik (Citation2001)) and applies them in a CCE context. It then discusses emotions and their antecedents (value and control appraisals) experienced by secondary school students (N = 297) participating simultaneously in the Austrian CCE program k.i.d.Z.21 and in Fridays For Future (FFF) during the 2019/2020 school year. Results of quantitative and qualitative analyses indicate that FFF participants differ from other students (OS) in their emotions and their value and control appraisals. Characteristic findings are their predominant attribution of internal control (74.6%) and their extrinsic values (68.7%), as well as a high proportion of positive emotions (79%) compared to negative emotions (21%). For learning in CCE, the selected theories of emotions are recommended, as they provide a nuanced picture of the dominant emotions and their value and control appraisals within learners.

Introduction

The year of 2019 will go down in history as a year of public commitment to climate action. During European elections, Climate Change (CC) was prominently discussed (Zalc et al., Citation2019); globally, binding climate reductions were agreed upon by national governments (UNFCC, Citation2019) and climate emergencies were declared by various cities and municipalities (Ellsmoor, Citation2019). Sparking these political reactions, a group of young people have been skipping school on Fridays since summer 2018 to stand up for their own future and for the future of generations to come. By joining the Fridays For Future (FFF) movement and participating in climate protests, young people demand swift and drastic societal action against global warming (Moor et al., Citation2020; Sommer et al., Citation2019; Wahlström, Kocyba, et al., Citation2019). Greta Thunberg, the leading character of the FFF-protests, and her peers, take a forceful stand against the missing political action to CC (Kennedy & Johnston, Citation2019; Overwien, Citation2019). Their rigorous demand “to act as if the house is on fire” (Probst, Citation2020) and their enthusiastic visions, manifested in chants like “We are unstoppable, another world is possible” (Queally, Citation2019) impressively showed the affective elements associated with the topic of CC. While climate protest settings were acknowledged as joyful and inspiring (Bowman, Citation2019; Landmann & Rohmann, Citation2020), negative emotions, like worry, frustration and anger, were recognised as key drivers for young people getting involved (Moor et al., Citation2020; Sommer et al., Citation2019). Beyond evoking emotions among the young protesters themselves, the spectators are also affected, either supporting demonstrations as engagement of young activists, or presuming extrinsic motivations for participation, like absenteeism from school (Reinhardt, Citation2019; Wehrden et al., Citation2019). Undoubtedly, the affective component in the course of the FFF protests arouse other people’s emotions - whether unintentionally or deliberately.

If climate protests are seen as a form of climate action that takes place within young people’s personal sphere of influence, they are likely to be highly effective in convincing key societal actors within governments to take responsibility and measures for climate protection (Chawla & Cushing, Citation2007; Davis et al., Citation2019). Besides, as real-world learning settings (Deisenrieder et al., Citation2020; Reinhardt, Citation2019) climate protests and their emotional dimension become relevant in the broader context of Climate Change Education (CCE) (Anderson, Citation2012; UNESCO, Citation2019). As CCE can be a catalyst for societal transformation processes towards a climate-friendly future by bringing about a profound change in individual values and lifestyles (O’Brien, 2018), emotions that emerge in learning settings beyond the classroom, such as in the context of climate protests, need to be taken into account.

However, in CCE, the role of emotions and particularly, the question of how to deal with emotions to trigger young people’s learning processes has not been thoroughly analyzed yet. Some reasons for this may be the lack of clear theoretical backgrounds and definitions of emotions in CCE learning settings (Grund et al., Citation2024). However, given the urgency of tackling the consequences of climate change through a society-wide response, both practical problem solving and clear theoretical models are urgently needed (Corner et al., Citation2014; Grund et al., Citation2024; Ives et al., Citation2020; Leichenko & O’Brien, Citation2020).

To bridge this research gap, the aim of this study is to analyze emotions that occur in the course of FFF climate protests by using selected theoretical models. Finally, recommendations for designing CCE learning environments are derived from the results.

To do so, the study is structured as follows. First, a brief review about the role of emotions in CCE is presented. Next, the study design and methods are described, including selected theoretical models of emotions. Subsequently, the results are discussed in relation to the existing literature. Lastly, conclusions are drawn for dealing with emotions in CCE learning settings that incorporate key features of FFF protests.

Emotions in climate change education

Any critical engagement with CC, including the context of education, can trigger emotions in individuals. In fact, in CCE, the emotional component of the individual is a crucial factor for effective learning and is considered as important as the cognitive or conative dimension (Kuthe, Keller, et al., Citation2019; Kuthe, Körfgen, et al., Citation2019; Oberauer et al., Citation2023). For instance, a dramatic presentation of existential threats to nature and humanity and the confrontation with missing climate action may evoke negative emotions (Baker et al., Citation2021; Cunsolo & Ellis, Citation2018; Verlie, Citation2019). Thus, emotions that are commonly mentioned in combination with CC are worry, fear, stress, guilt, anger, frustration and resignation (Burke et al., Citation2018; Corner et al., Citation2015; Kleres & Wettergren, Citation2017), whereas a positive emotion frequently added to this set of negative emotions is hope (Kidman & Chang, Citation2021; Myers et al., Citation2012; Ojala, Citation2012, Citation2017, Citation2023).

As to the ideal composition of emotions in CCE taking into account effective learning about CC, opinions significantly diverge. For instance, negative emotions are considered to positively influence learners’ willingness for CC action (Agostini & van Zomeren, Citation2021; Bilandzic et al., Citation2017; Feldman & Hart, Citation2018), supporting comprehension of the urgency of this challenge (Cunsolo et al., Citation2020; Smith & Leiserowitz, Citation2012). In a contrary position, negatively depicting the consequences of CC is regarded to at best managing to raise attention among learners (Riede et al., Citation2016). Even more, negative emotions can be an obstacle to effective learning about CC (González-Gaudiano & Meira-Cartea, Citation2019). In contrast, positive emotions are considered to have the power to dismantle people’s psychological barriers of taking climate action in their daily lives (Chawla & Cushing, Citation2007; Landmann & Rohmann, Citation2020; Odou & Schill, Citation2020), leading to the desire for positively framed learning settings (Ardoin & Bowers, Citation2020; Riede et al., Citation2016; Salama & Aboukoura, Citation2018). However, according to Ojala, Citation2012, Citation2017, it is ultimately a combination of negative and positive emotions that must be considered when designing CCE learning environments. For classifying emotions into positive and negative categories, the concept of valence can be applied (Frenzel & Stephens, Citation2017; Grund et al., Citation2024; Weiner & Craighead, Citation2010). Further, the range of different emotions can be shown by the so called wheel of emotions (Plutchik, Citation2001).

In terms of how the emotional level can be addressed in the educational context, and in particular in FFF as an out-of-classroom learning setting, the concept of achievement emotions also becomes relevant (Schutz & Pekrun, Citation2007). In this model, emotions are tied directly to achievement activities or to achievement outcomes. Besides, they are determined by self-related and situational appraisals, comprising the two groups of subjective value and subjective control appraisals (Pekrun et al., Citation2007).

In fact, in CCE individual values, such as the appreciation of nature, are considered more fundamental in effective learning about CC than any other factor (Bouman et al., Citation2020; Corner & Clarke, Citation2017; Hornung, Citation2022; Maio, Citation2017), as they are acknowledged as an essential foundation for triggering transformative action (Heath & Gifford, Citation2006; Moser & Dilling, Citation2012; Saribas et al., Citation2017). As a result, the developers of (CCE) learning environments also need to be concerned with the values of the target group - in this case, young people (Corner et al., Citation2015). Value appraisals are considered as antecedents of emotions (Pekrun, Citation2006) and can be differentiated into extrinsic values that relate to the instrumental usefulness of (CC) actions, while intrinsic values refer to the value of the action itself - in this case climate action (Pekrun et al., Citation2007). While some years ago, CC seemed to have little impact on young people (Michelsen et al., 2015), today’s so-called generation FFF is assumed to be already materially saturated and committed to climate action in the present and future (Gehm, Citation2020).

Regarding the second antecedents of emotions, control appraisals are intensely discussed within the context of protest participation. Being involved in such collective actions can trigger a greater sense of internal and external control among individuals and shape the participants’ motivation and sense of agency to engage in future climate activities (Becker & Tausch, Citation2015; Schwartz et al., Citation2022). Whether internal control attributions imply that a person expects that one’s own climate actions are likely to bring about change (Cleveland et al., Citation2020; Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002), external control attributions describe that an event is perceived as being beyond one’s own control of climate action (Ernst et al., Citation2017). In the context of CCE, however, it is rather dealt with the concept of individuals’ locus of control and its positive influence on taking climate action (Agostini & van Zomeren, Citation2021; Boubonari et al., Citation2013; Leal Filho et al., Citation2019). Acknowledging its similarity to control appraisals, past CCE research identifies a missing or low locus of control about the effects of CC among the majority of teenagers (79%), whereas a high locus of control exists only within one fifth of teenagers (Kuthe, Keller et al., Citation2019). Interestingly, it is ultimately a combination of locus of control, climate change values and emotions including hope that might significantly contribute to future climate action (O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Ojala, Citation2017; Sahin et al., Citation2021).

Study design and methods

This study was carried out within the Austrian research-education cooperation k.i.d.Z.21 which aims at empowering young people from Austria and Germany to take the challenge of CC. During an entire school year 2019/2020, the students were involved in different learning modules that were characterized by the following aspects (Keller et al., Citation2019; Kuthe, Körfgen, et al., Citation2019; Riede et al., Citation2016):

peer-to-peer collaboration

transdisciplinary collaboration between schools and society

learner-centred approaches that address young peoples’ pre-conceptions and interests

research- and experiment-based learning

authentic learning settings

In a continuing monitoring process, the students’ learning process was evaluated via standardized online questionnaires before and after the project year.

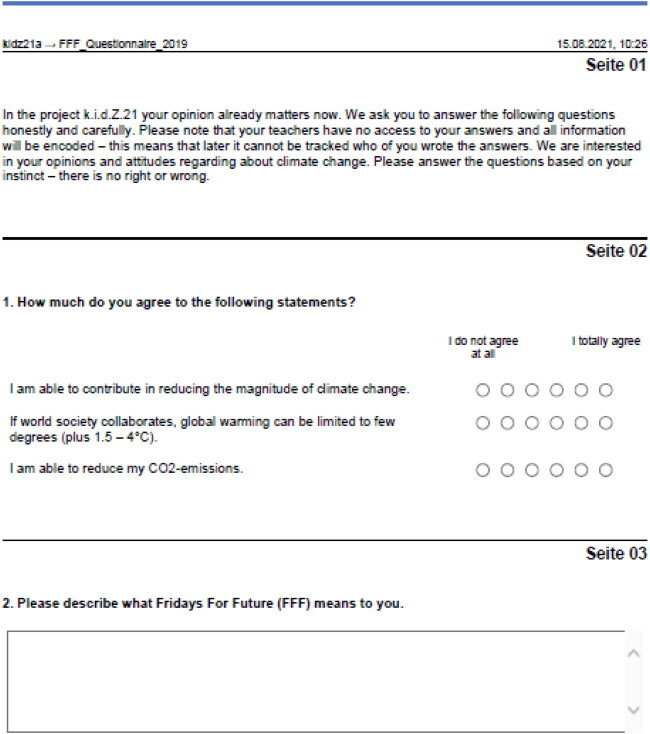

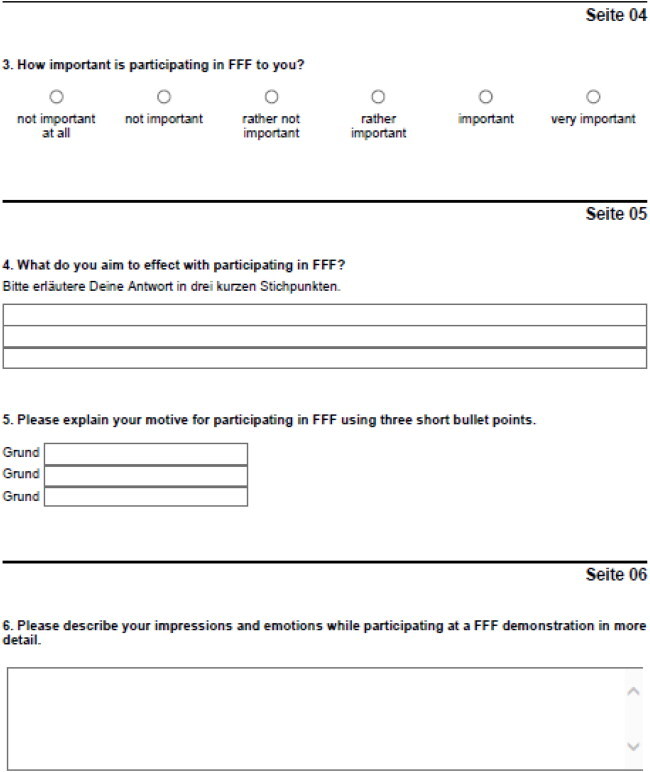

Keller et al. demonstrate a major learning success of selected learning approaches if applied in out-of-school learning settings of the High Alpine Mountains (Keller et al. (Citation2019). In the year 2019, reacting to the global FFF movements that also took place in the city of Innsbruck, an additional online survey was conducted and was responded by N = 297 students, whereof N = 176 students took part in FFF and N = 121 did not participate in the protests. It comprised three quantitative item batteries and four qualitative questions relating to the topic of FFF (see A1, FFF_Questionnaire). Due to the restrictions that came with the FFF protests that used to take place in Innsbruck as a consequence of global pandemic, protests were prohibited in the years 2020 and 2021, and thus, this study analyses research data of 2019.

Quantitative analysis

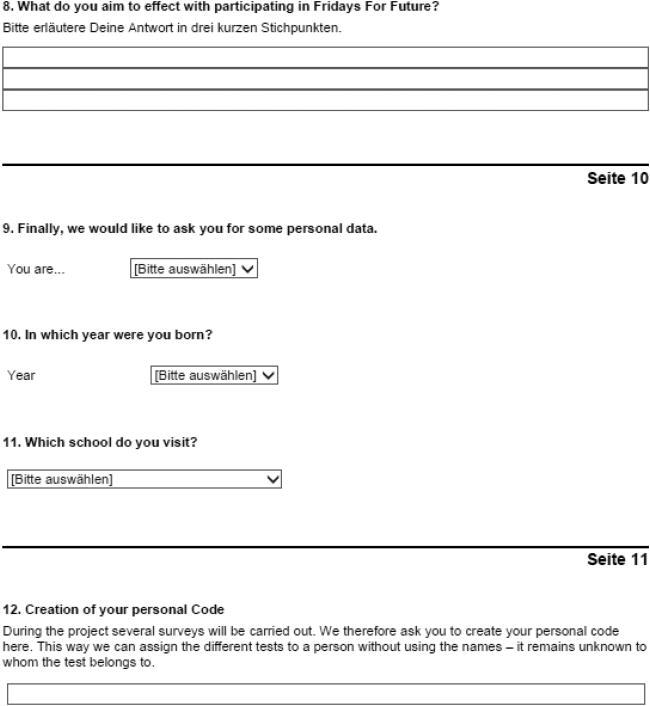

Firstly, two closed questions each asking for the value of participating in FFF and the perceived control of contributing to climate protection are asked (see A1, FFF_Questionnaire). The quantitative data is evaluated by IBM SPSS Statistics 25. For the quantitative analysis of the sample, the t-test for dependent samples is deployed in order to compare the results of the pre- and post-test, while significant changes are indicated by the symbol “*” (see A2, Table 1_Quantitative Results). A test for normal distribution is forgone, as the t-test is robust against violation of the normal distribution and the sample size is bigger than 50 (Lix et al., Citation1996; Salkind, Citation2010). The evaluation is based on a level of confidence of 95% (z = 1.96). A significance level of p < 0.5 is considered as significant in the analysis of the data. In order to measure the practical relevance of the results, the correlation coefficient Pearson’s r according to Bravais–Person is calculated. The interpretation of the effect size (r = 0.10 weak effect, r = 0.30 medium effect, r = 0.50 strong effect) is used according to Cohen, Citation1992). Measuring the scale reliability (SR) of the constructs composed of different items of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha is calculated. The interpretation of Cronbach’s alpha is used according to Mohammed & Pandhiani, Citation2017) in a study about students’ evaluation of teaching effectiveness (a value of Cronbach’s alpha >0,7 is accepted to be sufficient) (see also Streiner, Citation2003). Two groups of FFF participants and non-participants or other students (OS) are compared regarding their mean value and standard deviation with the t-test for independent samples.

Qualitative analysis

The qualitative analysis process basically consists of two different parts:

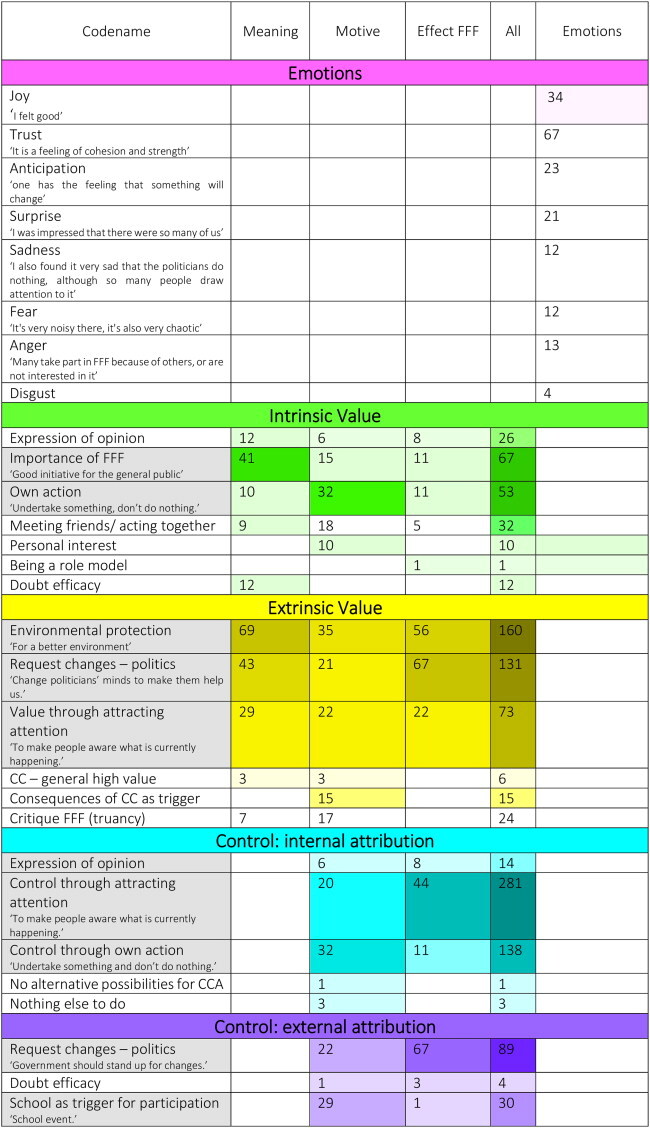

Firstly, based on three open questions asking for a) meaning, b) motives and c) effects of participating in FFF (see A1, FFF_Questionnaire), the control-value theory of Pekrun et al. (Citation2007) is applied. Students’ answers are categorized into the four different appraisals, comprising extrinsic/intrinsic values and external/internal attributions (see ).

Figure 1. Section of the control-value theory according to Schutz and Pekrun (Citation2007), modified by the authors for the purpose of this study. Appraisals (purple) comprise control and value appraisals (pink + blue entailing external/internal attributions and extrinsic/intrinsic values respectively) influence achievement emotions (yellow) which, in turn, influence the achievement activity, represented by participating in FFF (orange).

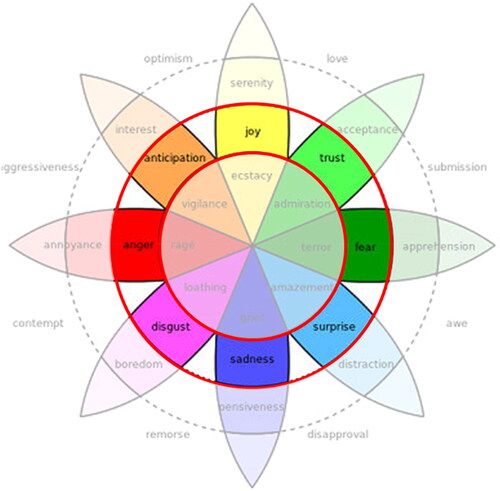

Figure 2. Wheel of emotions by Plutchik (Citation2001), adapted by the authors for the purpose of the study. The arrangement in a circle allows depicting similar emotions near to each other whereas opposite emotions are 180° apart. Eight sectors indicate the primary emotions (red ring).

In the FFF context, this theory can be interpreted as followed: students participate in FFF climate protests and attribute certain value and control appraisals, as well as achievement emotions to this activity.

Regarding internal control attributions in more detail, they describe if students perceive that participating in FFF can change the course of CC, e.g. by convincing/moving major societal actors to take measures for CC action (= outcome).

In contrast, if the situation is perceived to produce positive outcomes without any need for the individual to act, or that it will produce negative outcomes if no countermeasures are taken, it is talked about external control attribution. For example, students assume that others are in control of a situation independent of their own actions, e.g. major societal actors should take measures for CC action without any keywords indicating the students’ contribution to this outcome, it is described as external control attributions.

Regarding value appraisals, intrinsic values refer to the value of participating in FFF climate protests as a particular CC action per se, whereas extrinsic values relate to the instrumental usefulness of participating in FFF, like convincing/moving major societal actors to take measures for CC action.

In the second part, an open question asks for d) emotions that emerge during participating in FFF protests (see A1, FFF_Questionnaire). Students’ answers are analyzed along the wheel of emotions according to Plutchik (Citation2001) see () and they are coded into eigth basic bipolar emotions (See A3, Table 2_Qualitative Results). While negative emotions comprise sadness, anger, fear and disgust, positive emotions entail trust, joy, surprise and anticipation (Robinson, 2008).

All open-ended questions are analyzed by structured content analysis by identifying respective keywords in the text material (Krippendorff, Citation2019; Mayring, Citation2015), using the software MAXQDA, Citation2020 Plus Network. Reliability of qualitative results is secured by Cohen’s Kappa as a measure of intercoder reliability (Wirtz & Caspar, Citation2002). Therefore, one fifth of data material was coded by two different coders along the pre-defined category scheme (see A4, coding scheme). Subsequently, the results of the calculation of intercoder reliability were analyzed, and divergent codings were discussed to reach agreement. Afterwards the category scheme was defined in more detail, an intercoder reliability of 92% is reached.

Results

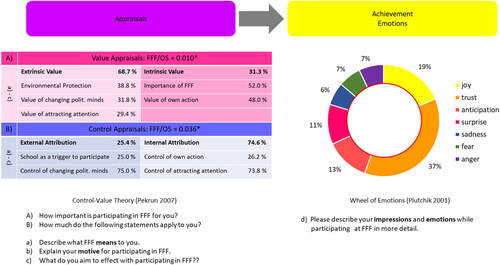

In the following section, results based on both emotions theories are summarized in a chart and are categorized into quantitative and qualitative results (see ).

Figure 3. Results based on the applied concepts of control-value-theory and wheel of emotions. Quantitative results from control and value appraisals and emotions are summarized (captures of tables) and represented by significant values. Qualitative results are represented by relative values (in the tables and in the ring). Results are based on quantitative (A, B) and qualitative questions (a-d) (see A1 FFF_questionnaire).

Starting with quantitative results (see A2, Table 1_Quantitative Results), the value appraisal among FFF participants is significantly higher in comparison to OS (significance = 0.010*). Regarding the control appraisals, in average, the FFF group also significantly differs from OS (significance = 0.010*).

Proceding with qualitative results that are based on the control-value theory of Pekrun et al., Citation2007, students answers are coded into extrinsic and intrinsic values and into external and intenal control attributions (see , tables and ring, also see A3, Table 2_Qualitative Results).

By three open questions asking for the a) meaning, b) motive and c) effect of participation in FFF (see A1, FFF_Questionnaire), we found that concerning value appraisals,

an extrinsic value of participating in FFF-activities (68.7%) can be determined, which means students, for example, aim to influence decisions of other people or of the government; e.g. requesting changes from politics (31.8%) (“government should stand up for changes”) or that they value attracting attention (29.4%) (“to make people aware of what is currently happening”) (see A3, Table 2_Qualitative Results). Other extrinsic values could not be determined, for example, if the value of the action lies in reaching another goal, like staying absent from school. Lastly, environmental protection complements to an extrinsic value (“for a better environment”) named by 38.8%, because the motives of participating in FFF and thus, the answer relates to an extrinsic value.

Continuing with intrinsic values (31.33%), individuals’ values are attributed to the participation in FFF, for instance, to show one’s personal attitude towards CC, comprising the value of own action (“do something good for the climate”) and importance of FFF (“good initiative for the general public”).

Regarding control appraisals, internal control attributions (74.6%) link the own participation in FFF to bring about change which means that they feel to have control over one’s own action (26.2%) (“I want to undertake something and don’t do nothing”) or of attracting attention (73.8%) (“Change other people’s minds”).

Closing with external control attribution (25.4%), students perceive the situation to produce positive outcomes without their own need to act, as they ascribe the control over climate action to others or to the situation itself. Thus, according to the students, politics should stand up for change (75.0%) (“The politicians should finally act”) and besides, FFF is considered as a “school event” (25.0%) that has triggered their participation.

Proceeding with the Wheel of Emotions (see ), emotions comprise joy (19%) (“I felt good”), trust (37%) (“It is a feeling of cohesion and strength”), anticipation (13%) (“one has the feeling that something will change”), surprise (11%) (“I was impressed that there were so many of us”) add to 80% of positive emotions. In addition, sadness (6%) (“I also found it very sad that the politicians do nothing, although so many people draw attention to it”), fear (7%) (“It’s very noisy there, it’s also very chaotic”), anger (7%) (“Many take part in FFF because of others, or are not interested in it”) add to 20% of negative emotions.

Discussion

Although the importance of the emotional dimension for effective learning about CC has received increasing attention in CCE research in recent years (Cunsolo & Ellis, Citation2018; Grund et al., Citation2024; Jones, Citation2017; Oberauer et al., Citation2023; Ratinen, Citation2021; Salama & Aboukoura, Citation2018), there is still a lack of theoretical foundations and clear definitions. In this study, exploring the emotions that emerge in students while participating in FFF has revealed some interesting findings for CCE learning environments.

Along the wheel of emotions (Plutchik, Citation2001), positive emotions outnumber negative emotions by a factor of three, comprising mainly “joy,” “trust,” “anticipation” and “surprise.” By recognising the FFF climate protests as positively framed learning settings, the findings are in line with some authors’ recommendations for effective learning in CCE (Riede et al., Citation2016; Salama & Aboukoura, Citation2018; Wilks, Citation2010). However, in contrast to the balanced combination of negative emotions and hope, as some researchers suggest in order to initiate transformative learning in CCE (Jacobson et al., Citation2020; O’Brien et al., Citation2019; Ojala, Citation2012, Citation2017, Citation2023), our results fall short with only a small proportion of negative emotions (“sadness” (7%), “fear” (7%) and “anger” (6%). This also contradicts prior FFF research, mainly reporting negative emotions, like worry, anxiety, panic, frustration, fury and anger among participants (Kühnert, Citation2020; Moor et al., Citation2020; Sommer et al., Citation2019). However, whereas previous research referred to emotions as drivers for participation, this study investigated emotions that emerged during the process of participating itself, which might explain the difference in findings.

Moreover, by applying the concept of achievement emotions (Pekrun & Stephens, Citation2010), value and control appraisals were identified as determinants of students’ emotions and as additional critical variables for effective learning about CC (Sahin et al., Citation2021). Concerning value appraisals, students attend FFF because they value “changing political minds,” “attracting attention” to the topic of CC and “protecting the environment,” thus demonstrating their extrinsic values. Simultaneously, these extrinsic values are closely linked to particular types of effective climate actions, confirming the power of values for triggering transformative action (Bouman et al., Citation2020; Chiari et al., Citation2016; Moser & Dilling, Citation2012). Furthermore, the findings correspond with recent FFF research, identifying political engagement or persuading policymakers to take science seriously, as the main motives for young people’s participation (Bowman, Citation2019; Evensen, Citation2019; Wahlström, Sommer et al., Citation2019). Moreover, these motives reflect the key requirements that young people have for an effective CCE learning environment (Jones & Davison, Citation2021).

At the same time, the results contradict one of the central criticisms of hypocricy, pointing to skipping school as the main extrinsic value of participating in FFF (Reinhardt, Citation2019; Wehrden et al., Citation2019). Besides, this study identifies students’ intrinsic values, such as recognising the “importance of FFF,” as well as valuing the “own action” of participation, supporting the claim that “stopping the climate crisis” is becoming a central value for the materially saturated youth of the Western world (Gehm, Citation2020). For years, the CCE debate has been divided over values in relation to climate change: whether intrinsic values are associated with positive engagement on climate change, or whether self-enhancing values are seen as an obstacle (Boyes & Stanisstreet, Citation2012; Corner et al., Citation2014; Hibberd & Nguyen, Citation2013). Eventually, the shared extrinsic and intrinsic values emerging among school students during participating in FFF might point to a possible solution approach to the discussion about how to overcome the identified gap of intrinsic, post‐materialistic values in CCE (Bouman et al., Citation2020; Hibberd & Nguyen, Citation2013).

Concerning control appraisals, this study reveals both internal and external types among participants in FFF protests. Apparently, participants acknowledge themselves having the internal control for positive climate action, by “undertaking their own action” and by “attracting attention” during their participation, while they reveal their external control attributions by demanding “changes from politics.”

In CCE research, individuals’ locus of control is considered to be a crucial factor in triggering different types of CC actions (Agostini & van Zomeren, Citation2021; Bamberg et al., Citation2015; Chawla & Cushing, Citation2007; Cleveland et al., Citation2020; Ernst et al., Citation2017; Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002), but may not be present in a proportion of teenagers (Kuthe, Keller, et al., Citation2019). The FFF protests allow the students to learn actively, independently and democratically in authentic environments outside the classroom (France & Haigh, Citation2018; Jones & Davison, Citation2021; Spector et al., Citation2014). Such learning environments may increase both external and internal control attributions (Schwartz et al., Citation2022) among different groups of teenagers, including those with low levels of control for climate action (Kuthe, Keller et al., Citation2019).

To recapitulate the aspects discussed, it can be adhered that FFF participants are clearly different from OS in terms of their emotions and their appraisals, as confirmed by quantitative and qualitative analyses.

Indeed, the FFF case example demonstrates how value and control assessments can be triggered by authentic, out-of-school CCE learning settings (Agostini & van Zomeren, Citation2021; France & Haigh, Citation2018; Spector et al., Citation2014).

Lastly, for initiating the desired climate change action, CCE requires learning interventions that acknowledge the primary role of emotions to initiate the desired climate action (Baker et al., Citation2021; Grund et al., Citation2024; Oberauer et al., Citation2023; Schwartz et al., Citation2022).

Conclusion

Bridging the gap between emotions and learning in CCE, the case study of the FFF climate protests demonstrated how theoretical models can be applied to obtain information about the prevailing emotions of the audience. Furthermore, value and control appraisals were identified as determinants of emotions, which at the same time represent critical variables for effective learning in CCE. In a positively framed environment characterized by “trust,” “joy” and “anticipation,” students appreciate the “importance of FFF” which they value and control in order to “attract attention.” It also gives them the value and the control to carry out their “own action” and to “undertake something,” by “demanding changes from politics.”

Resonating with the students’ value concepts and enabling solution-oriented learning, FFF appears to be an authentic, real-world learning setting promotes young people’s participation in protest as a highly effective form of climate action. In conclusion, learning settings that mirror key features of the FFF climate protests reveal success factors for effective learning in CCE even beyond the affective component. Following the pandemic, climate protests have been re-emerging worldwide under the name of diverse initiatives, enabling public engagement from the values up and allowing CCE to learn continuosly from this authentic setting.

Acknowledgements

Besides, we’d also like to thank the University of Innsbruck and its Institute of Teaching and Learning for funding publication costs. Many thanks also to our dear former and current colleagues of our working group who have done great work in the run-up to this publication and who are still supporting us with their experience. Last but not least, we would like to thank all the students from Austria and Bavaria who answered our questions in digital form with great patience and diligence during the pandemic. Eventually, thanks to all our collaborating teachers, who are motivated to participate in the several projects of our working group Education and Communication for Sustainable Development (EDUCOMSD).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, whether in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, nor in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agostini, M., & van Zomeren, M. (2021). Toward a comprehensive and potentially cross-cultural model of why people engage in collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of four motivations and structural constraints. Psychological Bulletin, 147(7), 667–700. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000256

- Anderson, A. (2012). Climate Change Education for Mitigation and Adaptation. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 6(2), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408212475199

- Ardoin, N. M., & Bowers, A. W. (2020). Early childhood environmental education: A systematic review of the research literature. Educational Research Review, 31, 100353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100353

- Baker, C., Clayton, S., & Bragg, E. (2021). Educating for resilience: Parent and teacher perceptions of children’s emotional needs in response to climate change. Environmental Education Research, 27(5), 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1828288

- Bamberg, S., Rees, J., & Seebauer, S. (2015). Collective climate action: Determinants of participation intention in community-based pro-environmental initiatives. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 43, 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.06.006

- Becker, J. C., & Tausch, N. (2015). A dynamic model of engagement in normative and non-normative collective action: Psychological antecedents, consequences, and barriers. European Review of Social Psychology, 26(1), 43–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2015.1094265

- Bilandzic, H., Kalch, A., & Soentgen, J. (2017). Effects of Goal Framing and Emotions on Perceived Threat and Willingness to Sacrifice for Climate Change. Science Communication, 39(4), 466–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547017718553

- Boubonari, T., Markos, A., & Kevrekidis, T. (2013). Greek pre-service teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and environmental behavior toward marine pollution. The Journal of Environmental Education, 44(4), 232–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2013.785381

- Bouman, T., Verschoor, M., Albers, C. J., Böhm, G., Fisher, S. D., Poortinga, W., Whitmarsh, L., & Steg, L. (2020). When worry about climate change leads to climate action: How values, worry and personal responsibility relate to various climate actions. Global Environmental Change, 62, 102061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102061

- Bowman, B. (2020). Imagining future worlds alongside young climate activists: A new framework for research. Fennia - International Journal of Geography, 197(2), 295–305. https://doi.org/10.11143/fennia.85151

- Boyes, E., & Stanisstreet, M. (2012). Environmental education for behaviour change: Which actions should be targeted? International Journal of Science Education, 34(10), 1591–1614. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2011.584079

- Burke, S. E. L., Sanson, A. V., & van Hoorn, J. (2018). The psychological effects of climate change on children. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(5), 35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0896-9

- Chawla, L., & Cushing, D. F. (2007). Education for strategic environmental behavior. Environmental Education Research, 13(4), 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701581539

- Chiari, S., Völler, S., & Mandl, S. (2016). Wie lassen sich Jugendliche für Klimathemen begeistern? Chancen und Hürden in der Klimakommunikation. GW-Unterricht, (1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1553/gw-unterricht141s5

- Cleveland, M., Robertson, J. L., & Volk, V. (2020). Helping or hindering: Environmental locus of control, subjective enablers and constraints, and pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of Cleaner Production, 249, 119394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119394

- Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783

- Corner, A., & Clarke, J. (2017). Talking climate: From research to practice in public engagement. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46744-3

- Corner, A., Markowitz, E., & Pidgeon, N. (2014). Public engagement with climate change: The role of human values. WIREs Climate Change, 5(3), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.269

- Corner, A., Roberts, O., Chiari, S., Völler, S., Mayrhuber, E. S., Mandl, S., & Monson, K. (2015). How do young people engage with climate change? The role of knowledge, values, message framing, and trusted communicators. WIREs Climate Change, 6(5), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.353

- Cunsolo, A., & Ellis, N. R. (2018). Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nature Climate Change, 8(4), 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0092-2

- Cunsolo, A., Harper, S. L., Minor, K., Hayes, K., Williams, K. G., & Howard, C. (2020). Ecological grief and anxiety: The start of a healthy response to climate change? The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(7), e261–e263. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30144-3

- Davis, J. L., Love, T. P., & Fares, P. (2019). Collective social identity: Synthesizing identity theory and social identity theory using digital data. Social Psychology Quarterly, 82(3), 254–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272519851025

- Deisenrieder, V., Kubisch, S., Keller, L., & Stötter, J. (2020). Bridging the action gap by democratizing climate change education—The Case of k.i.d.Z.21 in the context of Fridays For Future. Sustainability, 12(5), 1748. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051748

- Ellsmoor, J. (2019). Climate emergency declarations: How cities are leading the charge. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamesellsmoor/2019/07/20/climate-emergency-declarations-how-cities-are-leading-the-charge/?sh=5b6bb074f149.

- Ernst, J., Blood, N., & Beery, T. (2017). Environmental action and student environmental leaders: Exploring the influence of environmental attitudes, locus of control, and sense of personal responsibility. Environmental Education Research, 23(2), 149–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2015.1068278

- Evensen, D. (2019). The rhetorical limitations of the #FridaysForFuture movement. Nature Climate Change, 9(6), 428–430. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0481-1

- Feldman, L., & Hart, P. S. (2018). Is There Any Hope? How Climate Change News Imagery and Text Influence Audience Emotions and Support for Climate Mitigation Policies. Risk Analysis : An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis, 38(3), 585–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12868

- France, D., & Haigh, M. (2018). Fieldwork@40: Fieldwork in geography higher education. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 23(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2018.1515187

- Frenzel, A., & Stephens, E. J. (2017). Emotionen. In T. Götz, A. Frenzel, M. Dresel, & R. Pekrun (Eds.), Emotion, motivation und selbstreguliertes Lernen (pp. 148–160). StandardWissen Lehramt, Band 3481.

- Gehm, F. (2020). Das Internet-Problem von Fridays For Future. https://www.welt.de/wirtschaft/article213620160/Fridays-for-Future-Onlinestreiks-locken-kaum-Jugendliche-an.html.

- González-Gaudiano, E. J., & Meira-Cartea, P. Á. (2019). Environmental education under siege: Climate radicality. The Journal of Environmental Education, 50(4-6), 386–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2019.1687406

- Grund, J., Singer-Brodowski, M., & Büssing, A. G. (2024). Emotions and transformative learning for sustainability: A systematic review. Sustainability Science, 19(1), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-023-01439-5

- Heath, Y., & Gifford, R. (2006). Free-market ideology and environmental degradation. Environment and Behavior, 38(1), 48–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916505277998

- Hibberd, M., & Nguyen, a (2013). Climate change communications & young people in the Kingdom: A reception study. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics, 9(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1386/macp.9.1.27_1

- Hornung, J. (2022). Social identities in climate action. Climate Action, 1-9, 1(1) https://doi.org/10.1007/s44168-022-00005-6

- Ives, C. D., Freeth, R., & Fischer, J. (2020). Inside-out sustainability: The neglect of inner worlds. Ambio, 49(1), 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01187-w

- Jacobson, L., Åkerman, J., Giusti, M., & Bhowmik, A. (2020). Tipping to staying on the ground: Internalized knowledge of climate change crucial for transformed air travel behavior. Sustainability, 12(5), 1994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051994

- Jones, C. A., & Davison, A. (2021). Disempowering emotions: The role of educational experiences in social responses to climate change. Geoforum, 118(2), 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.11.006

- Jones, M. (Ed.). (2017). The handbook of secondary geography. The Geographical Association.

- Keller, L., Stötter, J., Oberrauch, A., Kuthe, A., Körfgen, A., & Hüfner, K. (2019). Changing climate change education: Exploring moderate constructivist and transdisciplinary approaches through the research-education co-operation k.i.d.Z.21. GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 28(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.28.1.10

- Kennedy, E. H., & Johnston, J. (2019). If you love the environment, why don’t you do something to save it? Bringing culture into environmental analysis. Sociological Perspectives, 62(5), 593–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121419872871

- Kidman, G., & Chang, C. ‑H. (2021). Hope and its implication for geographical and environmental education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 30(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2021.1878753

- Kleres, J., & Wettergren, Å. (2017). Fear, hope, anger, and guilt in climate activism. Social Movement Studies, 16(5), 507–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2017.1344546

- Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145401

- Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). SAGE.

- Kühnert, T. (2020). Wie emotional darf Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung sein? https://www.bpb.de/mediathek/302320/wie-emotional-darf-bildung-fuer-nachhaltige-entwicklung-sein.

- Kuthe, A., Keller, L., Körfgen, A., Stötter, H., Oberrauch, A., & Höferl, K. ‑M. (2019). How many young generations are there? – A typology of teenagers’ climate change awareness in Germany and Austria. The Journal of Environmental Education, 50(3), 172–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2019.1598927

- Kuthe, A., Körfgen, A., Stötter, H., Keller, L., Riede, M., & Oberrauch, A. (2019). Strengthening personal concern and the willingness to act through climate change communication. In W. Leal Filho, B. Lackner, & H. McGhie (Eds.), Climate change management. Addressing the challenges in communicating climate change across various audiences (pp. 65–79). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98294-6_5

- Landmann, H., & Rohmann, A. (2020). Being moved by protest: Collective efficacy beliefs and injustice appraisals enhance collective action intentions for forest protection via positive and negative emotions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 71, 101491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101491

- Leal Filho, W., Mifsud, M., Molthan-Hill, P., J. Nagy, G., Veiga Ávila, L., & Salvia, A. L. (2019). Climate change scepticism at universities: A global study. Sustainability, 11(10), 2981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102981

- Leichenko, R., & O’Brien, K. (2020). Teaching climate change in the Anthropocene: An integrative approach. Anthropocene, 30, 100241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2020.100241

- Lix, L. M., Keselman, J. C., & Keselman, H. J. (1996). Consequences of assumption violations revisited: A quantitative review of alternatives to the one-way analysis of variance F test. Review of Educational Research, 66(4), 579–619. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543066004579

- Maio, G. R. (2017). The psychology of human values. A psychology press book. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- MAXQDA. (2020). Software für qualitative Datenanalyse [Sozialforschung GmbH]. MAXQDA. https://www.maxqda.de/faq/wie-zitiert-man-maxqda#.

- Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical background and procedures. In A. Bikner-Ahsbahs, C. Knipping, & N. Presmeg (Eds.), Advances in mathematics education. Approaches to qualitative research in mathematics education: Examples of methodology and methods (Vol. 23, pp. 365–380). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9181-6_13

- Michelsen, G., Grunenberg, H., Mader, C., & Barth, M. (2015). Nachhaltigkeit bewegt die jüngere Generation: Ergebnisse der bundesweiten Repräsentativbefragung und einer qualitativen Explorativstudie, Mai-Juli 2015. Greenpeace Nachhaltigkeitsbarometer: Vol. 2015. VAS. https://www.greenpeace.de/sites/www.greenpeace.de/files/publications/nachhaltigkeitsbarometer-2015-zusammenfassung-greenpeace-20160113_0.pdf.

- Mohammed, A., & Pandhiani, M. S. (2017). Analysis of factors affecting student evaluation of teaching effectiveness in Saudi higher education: The case of Jubail University College. American Journal of Educational Research, 5(5), 464–475. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-5-5-2

- Moor, J. d., Uba, K., Wahlström, M., Wennerhag, M., & Vydt, M. d (2020). Protest for a future II: Composition, mobilization and motives of the participants in Fridays For Future climate protests on 20-27 September. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339446838_Protest_for_a_future_II_Composition_mobilization_and_motives_of_the_participants_in_Fridays_For_Future_climate_protests_on_20-27_September_2019_in_19_cities_around_the_world.

- Moser, S. C., & Dilling, L. (2012). Communicating climate change: Closing the science‐action gap. In Dryzek, J. S. Norgaard, R. B. & Schlosberg, D. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of climate change and society. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199566600.003.0011

- Myers, T. A., Nisbet, M. C., Maibach, E. W., & Leiserowitz, A. A. (2012). A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change. Climatic Change, 113(3-4), 1105–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0513-6

- O’Brien, K. L., Hochachka, G., & Gram-Hanssen, I. (2019). Creating a culture for transformation. In G. Feola, H. Geoghegan, & A. Arnall. (Eds.), Climate and culture (pp. 266–290). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Oberauer, K., Schickl, M., Zint, M., Liebhaber, N., Deisenrieder, V., Kubisch, S., Parth, S., Frick, M., Stötter, H., & Keller, L. (2023). The impact of teenagers’ emotions on their complexity thinking competence related to climate change and its consequences on their future: Looking at complex interconnections and implications in climate change education. Sustainability Science, 18(2), 907–931. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01222-y

- Odou, P., & Schill, M. (2020). How anticipated emotions shape behavioral intentions to fight climate change. Journal of Business Research, 121(2), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.047

- Ojala, M. (2012). Hope and climate change: The importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environmental Education Research, 18(5), 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.637157

- Ojala, M. (2017). Hope and anticipation in education for a sustainable future. Futures, 94, 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2016.10.004

- Ojala, M. (2023). Hope and climate-change engagement from a psychological perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 49, 101514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101514

- Overwien, B. (2019). Wie emotional darf Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung sein? https://www.bpb.de/mediathek/302320/wie-emotional-darf-bildung-fuer-nachhaltige-entwicklung-sein.

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

- Pekrun, R., Frenzel, A. C., Götz, T., & Perry, R. P. (2007). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: An integrative approach to emotions in education. In P. A. Schutz & R. Pekrun (Eds.), Emotion in education (pp. 13–36). Academic Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/41004922_The_control-value_theory_of_achievement_emotions_An_integrative_approach_to_emotions_in_education.

- Pekrun, R., & Stephens, E. J. (2010). Achievement emotions: A control-value approach. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(4), 238–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00259.x

- Plutchik, R. (2001). The Nature of Emotions: Human emotions have deep evolutionary roots, a fact that may explain their complexity and provide tools for clinical practice. American Scientist, 89(4), 344–350. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27857503?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents. https://doi.org/10.1511/2001.28.344

- Probst, M. (2020). "Unser Haus brennt noch immer": Thunberg in Davos. https://orf.at/stories/3151752/.

- Queally, J. (2019). ‘We are unstoppable, another world is possible!’: Hundreds storm police lines to shut down massive coal mine in Germany. https://www.commondreams.org/news/2019/06/22/we-are-unstoppable-another-world-possible-hundreds-storm-police-lines-shut-down.

- Ratinen, I. (2021). Students’ knowledge of climate change, mitigation and adaptation in the context of constructive hope. Education Sciences, 11(3), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11030103

- Reinhardt, S. (2019). Fridays For Future – Moral und Politik gehören zusammen. https://www.budrich-journals.de/index.php/gwp/article/view/33478. https://doi.org/10.3224/gwp.v68i2.01

- Riede, M., Keller, L., & Greissing, A. (2016). The importance of positive messages and solution-oriented framing of climate change: A casestudy in the context of secondary school education. In B. Hinger (Ed.), Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Fachdidaktik. Zweite "Tagung der Fachdidaktik" 2015: Sprachsensibler Sach-Fach-Unterricht - Sprachen im Sprachunterricht (pp. 97–127). Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Fachdidaktik 2. Tagung der Fachdidaktik 2015.

- Sahin, E., Alper, U., & Oztekin, C. (2021). Modelling pre-service science teachers’ pro-environmental behaviours in relation to psychological and cognitive variables. Environmental Education Research, 27(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1812538

- Salama, S., & Aboukoura, K. (2018). Role of emotions in climate change communication. In W. Leal Filho, E. Manolas, A. M. Azul, U. M. Azeiteiro, & H. McGhie (Eds.), Climate change management. Handbook of climate change communication: Vol. 1 (pp. 137–150). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69838-0_9

- Salkind, N. (2010). Encyclopedia of research design. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412961288

- Saribas, D., Kucuk, Z. D., & Ertepinar, H. (2017). Implementation of an environmental education course to improve pre-service elementary teachers’ environmental literacy and self-efficacy beliefs. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 26(4), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2016.1262512

- Schutz, P. A., & Pekrun, R. (Eds.) (2007). Emotion in education. Academic Press.

- Schwartz, S. E. O., Benoit, L., Clayton, S., Parnes, M. F., Swenson, L., & Lowe, S. R. (2022). Climate change anxiety and mental health: Environmental activism as buffer. Current Psychology (New Brunswick, N.J.), 42, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02735-6

- Smith, N., & Leiserowitz, A. (2012). The rise of global warming skepticism: Exploring affective image associations in the United States over time. Risk Analysis: An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis, 32(6), 1021–1032. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01801.x

- Sommer, M., Rucht, D., Haunss, S., & Sabrina, Z. (2019). Fridays For Future. Profil, Entstehung und Perspektiven der Protestbewegung in Deutschland. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335240815_Fridays_for_Future_Profil_Entstehung_und_Perspektiven_der_Protestbewegung_in_Deutschland.

- Spector, J. M., Merrill, M. D., Elen, J., & Bishop, M. J. (Eds.) (2014). Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (4th ed.). Springer. http://gbv.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=1317738. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3185-5

- Streiner, D. L. (2003). Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80(1), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18

- UNESCO. (2020). Climate Change Education. https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-sustainable-development/cce.

- UNFCC. (2019). Climate action and support trends: Based on national reports submitted to the UNFCCC secretariat under the current reporting framework. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Climate_Action_Support_Trends_2019.pdf.

- Verlie, B. (2019). Bearing worlds: Learning to live-with climate change. Environmental Education Research, 25(5), 751–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1637823

- Wahlström, M., Kocyba, P., Vydt, M. d., Moor, J. d., & Davies, S. (2019). Protest for a future: Composition, mobilization and motives of the participants in Fridays For Future climate protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European cities. https://eprints.keele.ac.uk/6571/7/20190709_Protest%20for%20a%20future_GCS%20Descriptive%20Report.pdf.

- Wahlström, M., Sommer, M., Vydt, M. d., Moor, J. d., & Davies, S. (2019). Fridays For Future: A new generation of climate activism: Introduction to country reports. In M. Wahlström, P. Kocyba, M. d. Vydt, & J. d. Moor (Eds.), Protest for a future: Composition, mobilization and motives of the participants in Fridays For Future climate protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European cities, https://protestinstitut.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/20190709_Protest-for-a-future_GCS-Descriptive-Report.pdf.

- Wehrden, H., von Kater-Wettstädt, L., & Schneidewind, U. (2019). Fridays For Future aus nachhaltigkeitswissenschaftlicher Perspektive. GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 28(3), 307–309. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.28.3.12

- Weiner, I. B., & Craighead, E. W. (Eds.) (2010). Corsini encyclopedia of psychology. John Wiley & Sons.

- Wilks, J. (2010). Child-friendly cities: A place for active citizenship in geographical and environmental education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 19(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382040903545484

- Wirtz, M. A., & Caspar, F. (2002). Beurteilerübereinstimmung und Beurteilerreliabilität: Methoden zur Bestimmung und Verbesserung der Zuverlässigkeit von Einschätzungen mittels Kategoriensystemen und Ratingskalen. Hogrefe Publisher for Psychology.

- Zalc, J., Becuwe, N., & Buruian, A. (2019). The 2019 European elections: Have European elections entered a new dimension? The 2019 post-electoral survey. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/files/be-heard/eurobarometer/2019/post-election-survey-2019-complete-results/report/en-post-election-survey-2019-report.pdf.

Appendices

A1. FFF_questionnaire

A2. Table 1_quantitative results

A3. Table 2_qualitative results

Coding categories, data extracted from MAXQDA - including selected case examples of students.