Abstract

Issue

Health systems have been increasingly called upon to address population health concerns and continuing medical education (CME) is an important means through which clinical practices can be improved. This manuscript elaborates on existing conceptual frameworks in order to support CME practitioners, funders, and policy makers to develop, implement, and evaluate CME vis-a-vis population health concerns.

Evidence

Existing CME conceptual models and conceptions of CME effectiveness require elaboration in order to meet goals of population health improvement. Frameworks for the design, implementation and evaluation of CME consistently reference population health, but do not adequately conceptualize it beyond the aggregation of individual patient health. As a pertinent example, opioid prescribing CME programs use the opioid epidemic to justify their programs, but evaluation approaches are inadequate for demonstrating population health impacts. CME programs that are built to have population health outcomes using frameworks intended primarily for physician performance and patient health outcomes are thus not able to recognize either non-linear associations or negative unintended consequences.

Implications

This proposed conceptual framework draws on the fields of clinical population medicine, the social determinants of health, health equity, and philosophies of population health to build conceptual bridges between the CME outcome levels of physician performance and patient health to population health. The authors use their experience developing, delivering, and evaluating opioid prescribing- and poverty-focused CME programs to argue that population health-focused CME must be re-oriented in at least five ways. These include: 1) scaling effective CME programs while evaluating at population health levels; 2) (re)interpreting evidence for program content from a population perspective; 3) incorporating social determinants of health into clinically-oriented CME activities; 4) explicitly building fluency in population health concepts and practices among health care providers and CME planners; and 5) attending to social inequity in every aspect of CME programs.

Introduction

Continuing medical education (CME) was cast in the late 2000s as an important means to change clinical practice in response to widespread calls to reduce medical error and improve quality of care.Citation1 As we near the end of another decade, health systems are being increasingly called upon to not only improve clinical outcomes but to also improve population health.Citation2–4 In this conceptual paper, we first argue that existing CME frameworks and conceptions of CME effectiveness need elaboration in order to meet the needs of this population health improvement agenda. Existing models either poorly conceptualize population health or assume population health outcomes to be the aggregate of individual patient health outcomes. We then explore the example of opioid analgesic prescribing CME to justify the pressing imperative to better conceptualize the relationship between CME and population health and to demonstrate hazards of assuming linear associations between individual patient outcomes and population health outcomes. Finally, we draw on insights from clinical population medicine (CPM), health equity, and philosophies of population health science to build the conceptual bridges connecting the typical outcome levels of physician knowledge, physician performance, and patient health to population health. We build a heuristic of “numerator work” (typical, physician-focused clinical interventions) and “denominator work” (typical population health interventions) to characterize five different means through which CME might align with population health imperatives. Taking examples from our extensive experience with developing, delivering, and evaluating CME programs focused on opioid analgesic prescribing and addressing poverty, we provide a framework for how CME practitioners, funders, and policy makers can develop, implement, and evaluate CME vis-a-vis population health concerns.

CME outcomes frameworks and population health

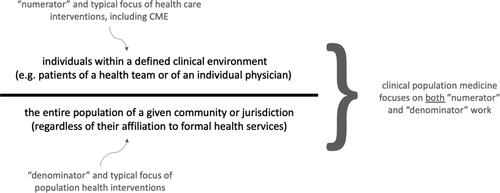

A variety of outcomes frameworks are used widely within CME, perhaps none more so than that of Moore et al.,Citation1 herein referred to as Moore’s framework. This framework developed in an era of increased concern about medical error and quality of care, and when CME was cast as one means for achieving service improvement via changing physician performance. There are many important contributions from this framework, but we will focus here on what the authors identify as the central point of their article, namely that, “before [CME] outcomes can be measured, educational planning focused on the outcomes must occur so that these outcomes can be expected to happen.”Citation1(p5) Their expanded outcomes framework identifies the multiple possible levels at which CME activities can be planned and assessed ().

Figure 1. Moore et al.’s expanded outcomes framework—levels 1 to 7 (adapted from Moore et al.Citation5).

Population health is clearly included in this framework at the top of the pyramid as level 7—we interpret their use of “community health” as synonymous with population health. Moore et al. note that ideal planning for CME would begin with community health status and then describe a process of “backward planning” from population health concerns to the other levels to identify the gap that can be addressed through CME. Notably, they expect that most gaps that CME can address will be at the physician competence level. They note that planning starting from population health status is idealized and may be impractical, and that most CME planning will likely begin with a focus on physician competence (level 4). Importantly, they do not conceptualize how the various levels integrate, but tacitly assume that improvements in physician competence will improve performance, then patient health and ultimately population health—concerns around this assumption have been persistent in the field of medical education for several decades.Citation6

This tacit progressive connection between the levels, and specifically to population health, becomes apparent in their discussion of CME outcomes measurement. Even though their expanded framework includes population health as an explicit outcome of interest, their discussion of outcomes assessment focuses only on competence, performance, and patient health status. Population health outcome assessment is not considered, as is evident from their outcome assessment table (; from Moore et al.Citation5).

Table 1. From Moore et al.’sCitation1 outcomes measurement framework - population health (Level 7) is NOT included.

Table 3. Hazard ratios between opioid doses and overdose, data from Dunn et al.Citation7

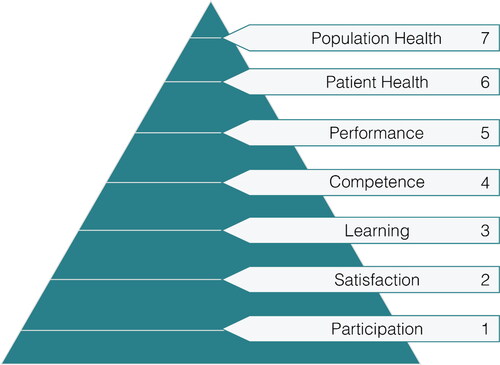

Moore et al.Citation5 published an update of their earlier framework as a response to changes in the continuing education field. Their updated framework focused on health professionals, rather than just physicians, and also more on interprofessional practice than on individual providers, though the framework is meant to continue to be relevant for CME specifically. Despite writing in an era that internationally is now much more attuned to population health, including in health professions education,Citation8 Moore et al.’s 2018 update does not better conceptualize population health and its connection to CME planning, assessment, and outcomes. For example, though the text of their paper discusses starting needs assessments from population health status, their needs assessment figure launches the needs assessment process only at “identify gap in patient health status” ().

Figure 2. Moore et al.’sCitation5 needs assessment in the outcomes framework.

Their technique of using “5 whys” to move from population health needs to actionable gaps for health professional education (HPE) is more detailed than the older framework. But this technique does not provide any specific means for maintaining a focus on population health. Instead, it reinforces attention on competence and performance at the clinical level. Similar to the older model, their assessment of impact focuses on health provider performance and patient health status and does not discuss populations. The 2018 update does provide some additional nuance about what they consider a population to be, namely, “population [is] defined by political or geographical considerations by a health system, by a group practice, or a disease.”Citation5(p906) However, the framework provides minimal insight into how population health outcomes may be different from an aggregate of patient health outcomes. In summary, Moore’s very influential planning and assessment framework prominently includes references to population health but does not further conceptualize what this is and how it could be addressed by CME. One can surmise then, that the under-conceptualization of population health may be due to an assumption that population health can be adequately subsumed within the concept of individual patient health.

While we have focused here on Moore’s framework, this conflation of population health with patient health is a consistent feature of other medical education outcomes frameworks. For example, Kirkpatrick’s frameworkCitation9,Citation10 and its specific adaptation to medical and health professions education,Citation11 is very widely used in the medical education evaluation literature. This framework identifies four levels of outcomes assessment. The fourth levels of “a) changes in organization practice” and “b) benefits to patient/clients” make no clear distinction between individual patient health and population health outcomes. Indeed Moore’s approach has explicitly built on the hierarchical approach of Kirkpatrick,Citation12 so this concordance should not be surprising. Notably, even less widely used nonhierarchical outcomes frameworksCitation13 also do not distinguish between patient and population health outcomes.

CME effectiveness and population health

We could not identify any systematic or other reviews of CME effectiveness and population health outcomes. However, there is substantial literature examining CME effectiveness in general. Critically examining this literature reinforces the poor conceptualization of population health and its conflation with individual patient health status.

An umbrella review by Cervero and GainesCitation14 of systematic reviews of CME effectiveness updates a previous report and included eight systematic reviews of CME effectiveness published between 2003 and 2014. Cervero and Gaines do not mention population health as an outcome of interest. Tellingly, though their aim is to examine the effectiveness of CME broadly, their inclusion criteria are focused specifically on effects at the levels of physician performance and clinical outcomes. Six of the eight systematic reviews in their reportCitation15–20 likewise make no further mention of population health or population health effectiveness. As one example, Marinopoulos et al. are very specific about their definition of clinical outcomes as “any change in patient health status, health-related behaviour of patients or attitudes about the physicians towards whom the CME intervention was directed.”Citation20(p13) There is no specific inclusion of population health within this definition.

In another included systematic review, Mansouri and Lockyer reference Moore’s framework, including a specific reference to population health, in their introduction.Citation21 However, in their methods they identify only 3 outcomes of interest: physician knowledge, physician performance and patient outcomes. We see a similar pattern in the review by Mazmanian et al.Citation22 of CME and clinical outcomes. While the authors are specifically focused on clinical outcomes, which they define as “what happens to patients once care has been rendered,”Citation22(p49S) they reference an earlier version of Moore’s framework (which includes population health as an outcome level)Citation12 and include an explicit reference to population health. The authors take pains to describe what constitutes a clinical outcome, and in doing so appear to conflate individual patient outcomes with population outcomes in saying, “in addition to measures of health status, such as [blood pressure] and fasting blood glucose, measures of patient satisfaction, medication adherence, and smoking cessation were included. These measures … coincide with highest levels of performance proposed by Moore” (emphasis ours).Citation22(p51S) This same conflation of population health with patient health is replicated in systematic reviews and perspectives of CME effectiveness which operationalize Kirkpatrick’s framework instead of Moore’s framework.Citation23,Citation24

Thus, similar to CME outcomes frameworks, the CME effectiveness literature either does not consider population health outcomes despite recognizing frameworks that reference population health, or this literature under-conceptualizes population health by conflating it with patient health. In their discussion, Mazmanian et al.Citation22 recognize that the focus of health care (and thus the focus of CME since its participants are health care providers) is on areas that are “amenable” to treatment. They are concerned specifically about the causal connections between clinical practices and health outcomes by identifying that deficiencies in medical care contribute only about 10% to mortality, compared to 40% by behavioral factors, 20% by social circumstances and 30% by genetics. As noted by other commentators on the appropriate levels and kinds of evaluation for CME,Citation6 this seems to give some rationale for CME programs to retreat from any inclusion of population health and to focus outcomes on measurable patient outcomes, as the (causal) relationships between clinical care and population health are considered to be either too tenuous or too complex.

Opioid analgesic prescribing CME and population health

We will now turn to opioid analgesic prescribing CME as an instructive case to: 1) justify the pressing need to align CME and population health, 2) highlight why conceptualizing population health outcomes as conflated with patient health outcomes is problematic, and 3) propose a characterization of population health outcomes that recognizes its connection with patient health outcomes but also clearly distinguishes the two outcome types.

Justifying the need to align CME and population health

Opioid-related harms continue at epidemic levels throughout North America—constituting one of the worst public health crises of this generation.Citation25,Citation26 In many jurisdictions, harms have in fact accelerated in the context of the global Covid-19 pandemic.Citation27 Recent trends suggest that while an increasing proportion of overdose deaths are due to illicit opioids such as heroin, fentanyl, and fentanyl analogues, as well as polysubstance use, prescribed opioids continue to be significant contributing factors.Citation28,Citation29 As we have noted elsewhere, increases in years of life lost through drug overdoses have also been noted in countries such as the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, Sweden, and Finland.Citation30,Citation31 Likewise, besides high-income North America, the regions of Eastern Europe, Australasia, North Africa, and the Middle East have a significantly higher age-standardized prevalence of opioid use disorder compared to the global estimate.Citation32 There have been a wide variety of policies addressing this epidemic, many of which have focused on prescribing. These include interventions such as prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs),Citation33 regulatory profession investigations,Citation34 and the development and dissemination of clinical practice guidelines.Citation35,Citation36

HPE, specifically CME, has been central to the implementation of many of these strategies in North America, as identified in a number of major policy documentsCitation37,Citation38 and even media reports.Citation39 Two systematic reviews have likewise examined continuing HPE as opioid epidemic health policy interventions. Furlan et al.Citation40 reviewed all strategies to improve the appropriate use of opioids, reduce the prevalence of opioid use disorder, and reduce deaths from prescribed opioids. They identified HPE as a promising strategy to improve the appropriate use of opioids and to reduce opioid misuse, abuse, diversion, and addiction. There were insufficient studies examining HPE for the population health outcomes of opioid overdose and death. Moride et al.Citation41 conducted a systematic review of interventions targeting the prescription of opioids. While the majority of these included studies focused on PDMPs, they did identify seven studies describing CME programs. In addition to summarizing the effectiveness of the various kinds of programs, this review was novel in classifying the outcomes using an evaluative framework, namely in terms of process (about the intervention), effectiveness (about the participants), and impact outcomes (about patients, the health system, and population health). However, the specific breakdown across evaluation outcome type for education programs versus other kinds of programs was not reported.

We conducted a scoping review of evaluations of opioid prescribing CME programs, their underlying theories, and conceptual models or frameworks, and how these related to the reported outcomes.Citation42 We used Moore’s framework to distinguish between kinds of outcomes (Levels 1–7). In this review, we identified 32 studies of opioid analgesic and naloxone (opioid antagonist) prescribing education programs, 84% of which used population health concerns related to opioid prescribing and opioid use to justify the development and evaluations of their programs. Only three of these 32 studies included population-level outcomes in their program evaluations and none of these outcome data sets were directly tied to the populations served by the educational program participants.Citation43–45

One reason for this may be that there was poor use of theory or conceptual models. In this same scoping review only seven studies explicitly described a theory, model, or framework that guided their intervention development, delivery, or evaluation.Citation46–52 Most of these were theories of individual behavior change such as the Theory of Planned Behavior or the Transtheoretic Model of Behavior Change. We did not identify use of any theories, models, or frameworks of behavior change models for population health. Two studies did explicitly cite Moore’s framework,Citation50,Citation51 however, neither of these studies reported population health outcomes. There is a clear gap, then, between the justification for opioid analgesic CME programs and their measured effects on population health perhaps because of a lack of clear guiding conceptual models or frameworks for doing so.

Problematizing the conflation of population health outcomes with clinical outcomes

There are reasons from the North American opioid epidemic to question an assumed linear or aggregative relationship between clinical and population health outcomes. As outlined earlier, much opioid epidemic policy has focused on prescribing practices and specifically reducing prescribing—from reducing the frequency and doses of new starts of opioids for acute and chronic pain, to reducing doses for people who are already on long-term opioid therapy. The logic of such approaches is obvious; if exposure to prescribed opioids is the driving force leading to opioid-related harms, then reducing prescribing should reduce opioid-related harms. In fact, numerous studies both in the United States (US) and Canada have demonstrated that these efforts (e.g., clinical practice guidelines, regulatory pressures, PDMPs, and CME) have now reduced the amounts of opioids prescribed, though absolute levels are still high.Citation25,Citation26,Citation53 At the population level, however, opioid harms such as mortality have continued to increase.Citation25,Citation26 This is in part because of increased access and exposure to a contaminated, and highly lethal, non-prescribed drug supply.Citation54 Clinical interventions, such as CME, that might focus only on performance measures (e.g., total prescribing) or patient-level outcomes (e.g., total dose of opioids consumed) would miss this negative and harmful association with increased population-level mortality. We cannot rely on an assumed linear association between clinical or individual patient outcomes and beneficial population health outcomes.

This is consistent with one of the basic principles of population health science outlined by Keyes and Galea that “the causes of differences in health across populations are not necessarily an aggregate of the causes of differences in health within populations”Citation55(p21) (emphasis ours). As one example of this distinction between individual and population health, McMichael notes a thread of population health research identifying that, in developed countries, life expectancy correlates inversely to income inequality (a characteristic of a population) but demonstrates little correlation to average income (a characteristic of individuals). Measurement of population health outcomes is something distinct and beyond the measurement of large numbers of patient health outcomes. Therefore, it is incumbent on those who fund, develop, deliver, and evaluate opioid prescribing CME to develop a framework that effectively accounts for populations that are not “merely aggregates of free-range individuals”Citation56(p887) especially since population health concerns are being used to justify opioid CME investments. We assert that this will also be true for other foci of CME that are justified using potential population health benefits.

Patient health versus population health outcomes

A useful addition to existing CME outcomes frameworks would be a clear distinction between patient health and population health outcomes. We have established that population health outcomes are often characterized as simple, larger-scale aggregations of patient health outcomes. Such a characterization of population health, however, would only be operational in the uncommon cases where the health phenomenon of interest demonstrates minimal clinical and social complexity. Instead, we suggest that considering health outcomes in terms of the two continuous parameters of: a) the specificity of the outcome compared to the focus of the CME intervention, and b) the scope of the population of interest compared to the reach of the CME intervention provides a more realistic and ample range of population health outcomes (). Very specific population health outcomes and a narrow scope of the population would characterize the prototypical population health outcome that is a simple aggregation of patient health outcomes. At the opposite end of the spectrum, more general health outcomes with a very wide scope for the population of interest would be considered as “distributive” population health outcomes. This breadth accords with distinctions between “narrow” and “broad” accounts of population health, and thus population health interventions and outcomes, within the population health science literature.Citation57 In we have provided some clarifying examples of these different kinds of population health outcomes in terms of an opioid prescribing CME program. Of note, we see both parameters as continuous without hard barriers between low, moderate, and high specificity or narrow, moderate, and wide scope.

Table 2. Categorizing population health outcomes by specificity of the outcome and the scope of the population compared to the CME intervention.

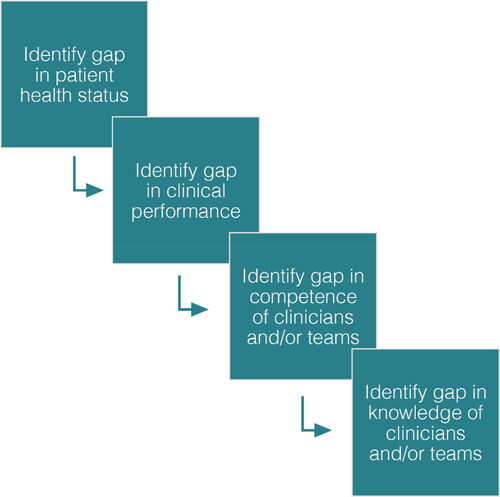

Clinical population medicine

One paradigm that might be helpful in elaborating a framework for population health focused CME is clinical population medicine (CPM) which Orkin et al. define as “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious application of population health approaches to care for individual patients and design of health care systems.”Citation58(p405) In a further essay about population health improvement through a new model of health service delivery in the province of Ontario, Canada, OrkinCitation59 delineates a notion of a population of individuals within a defined clinical environment (e.g., health team, physician’s practice) against the notion of a population in a given community or jurisdiction, regardless of their affiliation with or access to clinical services. He captures the former population as the “numerator” and the latter as “denominator” and argues that CPM, besides maintaining its traditional focus on “numerator work,” should also focus on “denominator work” ().

We will use this numerator/denominator distinction to explore the means through which CME can conceptually be expected to improve population health. First, we will use examples from opioid prescribing CME programs to: a) identify opportunities to scale effective programs across numerators; and, b) the importance of refocusing content from numerators to denominators. Then we will draw from our experience with Treating Poverty, a CME program focused on addressing social determinants of health, to: c) reorient classic denominator problems into tractable numerator problems; d) demonstrate the relevance of training clinicians in denominator work; and e) attend to equity as a priority in population health-oriented initiatives, including CME.

Scaling across numerators

One means to population level impact is via scalability. If a CME program has evident salutary effects on individual patients and is delivered to a large enough physician population, it should scale these effects to a large number of patients and therefore have a discernable population level effect. This is an example of doing large-scale “numerator work.” There are several examples of this among the opioid analgesic prescribing CME programs identified in our scoping review. Zisblatt et al.Citation60 report on a 2-hour train-the-trainer program (TTP) to increase the reach of an opioid prescribing CME program previously led only by subject area experts. The TTP trained 89 non-expert trainers over a 9-month period, who subsequently trained 1,419 health care provider participants in opioid prescribing over a two-year period. This compares favorably to a reach of 1,742 participants trained by the preexisting cohort of expert trainers. Importantly, they found no significant differences in participant knowledge, confidence, attitudes, and performance between the expert-led and trainer-led cohorts. Compared to the expert trainers, the non-expert trainers over-reached into rural health care providers where there are often disproportionate harms from opioids and poorer access to CME. Population health outcomes for this program were not reported.

Besides TTPs, another common means of increasing reach and achieving scalability is via technology. For example, Katzman et al.Citation61 report on a pain management and substance use disorder continuing education program that targeted health care providers in the US Indian Health Service (IHS). Given the vast geographic spread of the IHS, the continuing education providers made the live program available via teleconferencing software. Use of this technology facilitated participation of 1,315 health care provider participants distributed across 28 states. This program had previously been evaluated and had shown to be effective in improving health care provider knowledge of pain.

Another CME program that has leveraged technology to deliver opioid prescribing education is Safer Opioid Prescribing, of which authors have led the development and delivery.Citation62 This program delivers accredited CME using live webinars, which facilitates reach to physicians in rural and remote communities where there are disproportionate harms from opioids and poorer access to high quality CME. A recent evaluation of this program has demonstrated that this delivery model in fact reaches Ontario physicians in rural and non-major urban areas just as well as it reaches physicians practicing in major urban centers, and program fidelity is maintained over a variety of cohort sizes.Citation63

One possible means, then, of achieving population effects of CME is to increase reach. By reaching a larger health care provider population or a larger targeted health care provider group, the individual clinical effects can be multiplied over larger groups of individuals. This aggregative approach, however, is still susceptible to the non-linear associations between clinical effects and population effects. As outlined above, multiplying individual clinical effects through increasing the reach of CME does not necessarily translate into salutary distributive population effects, especially in problems characterized by non-linear relationships and complexity such as the opioid epidemic.

Reorienting content from numerators to numerators and denominators

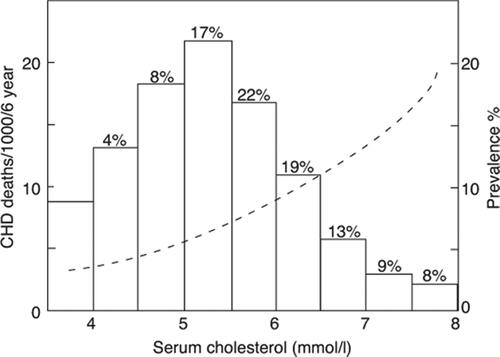

Another means of achieving a population health focus of CME is a change in the orientation not of the delivery system but in the content covered in the CME program and thus a change in the target populations of the subsequent clinical activities. Rose et al.Citation7 in his influential book on preventative medicine, has identified that prevention efforts in clinical practice tend to focus on “high-risk” individuals—namely the minority of the population that is at highest risk of developing a poor health outcome. This is seen as an efficiency-driven compromise given that large-scale, mass prevention efforts are either non-clinical in nature (e.g., improving air quality) or too expensive to deploy to the entire population (e.g., mass screening for lung cancer). However, Rose argues that focusing primarily on the high-risk subgroup ignores the population distribution of risk exposure, and thus misses important opportunities for prevention. He notes the majority of cases for a specific disease will in fact be in the low-risk group, though the prevalence rate will be higher in the high-risk group (). Even though there is a much higher prevalence rate of coronary heart disease (dotted line in ) in people with higher serum cholesterol levels (the “high risk” group), the proportion of overall deaths due to coronary heart disease (histogram bars) is much higher in the people with lower serum cholesterol levels (the “low risk” group).

Figure 4. Population distribution of CHD deaths according to serum cholesterol (from RoseCitation7).

He argues that a preventative approach aiming to have meaningful population health effects must consider an entire population, consider risk-distribution within this population, and not just focus on the overall population (a typical public health approach) or the high-risk subgroup (a typical clinical or health systems approach). Yet, the majority of clinical approaches to opioid prescribing in North America have taken a high-risk prevention approach. This is evident in how primary evidence around dose-related risks of opioids have been synthesized and communicated in clinical practice guidelines and then incorporated into knowledge translation tools and CME programs. In 2010 Dunn et al.Citation64 published what has since become a seminal paper (cited nearly 800 times as per Web of Science) in which they identified that as the dose of the prescribed opioids increased, so too did the risk of overdose (). For example, those who were on >100 milligrams of morphine equivalent (MME) per day had a nearly 9-fold increase in overdose risk as compared to those on a dose of 1–20 MME per day.

Citing Dunn et al.’s observational study in there influential national (Canadian) clinical practice guideline, Busse et al.Citation35 recommended both restricting opioid doses to below 90 MME and considering tapering for cases in which doses were already greater than 90 MME. These specific recommendations, and other recommendations for what to do for high-risk patients are what Busse et al.Citation65 argued would distinguish their guideline from previous US national guidelines.Citation36 Likewise, this Canadian guideline was specifically motivated by harms from prescribed opioids and is targeted toward “those who prescribe opioids or create policy regarding this issue.”Citation35(pE660) Many knowledge translation products (such as the Center for Effective Practice’s opioid tapering template)Citation66 specifically reference these guidelines to justify clinical actions that should be implemented in response to dose-related risks. Thus, we see in the knowledge generation, synthesis, and translation process an instantiation of Rose’s “high-risk strategy”: identifying the patient population at highest risk and then implementing clinical interventions (in this case tapering opioids) to reduce that risk with the aim of having population-level effects. CME programs aiming to be evidence-based and relying on this chain of evidence and evidence synthesis would thus be inclined to instantiate this kind of high-risk strategy in the practices of their physician participants.

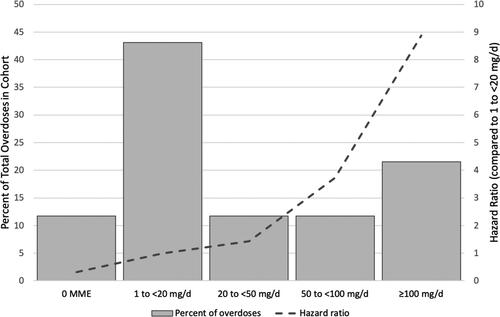

A truly population-focused strategy, on the other-hand, would use a population-level perspective on risk, including the distribution in low- and high-risk groups. In , we have re-interpreted Dunn et al.Citation64 data using the population prevention lens of Rose. Along the x-axis are the same cohorts stratified by opioid dose in MME. On the left y-axis is the percent of total overdoses and on the right y-axis is the hazard ratio (as compared to the 1–20 MME group). In this representation of the data, Dunn et al.’s original observation that the hazard ratio increases as dose increments increase is clear. What is also evident, however, is that the majority of overdoses are in the lower-risk groups, similar to what Rose identified for coronary heart disease. Greater than 40% of the overdoses were in the 1–20 MME group while just over 20% were in the >100 MME group. A Rose-influenced population-based approach to addressing these data would suggest that in addition to focusing on the high-risk group (>100 MME), preventative interventions should also be initiated for the rest of the population.

Figure 5. Population distribution of opioid overdoses according to opioid dose (reinterpreted from Dunn et al.Citation64).

For CME interventions to be able to do more “denominator” work, the underlying knowledge base and thus content must be (re)structured to focus on population-level interventions. According to our parameters for population health outcomes, this involves increasing the scope of the population of interest for the CME intervention. If the evidence, and syntheses thereof, instead focus on narrow, high-risk populations, we can expect CME interventions to continue to focus only on “numerator” work and achieve at best aggregative population health outcomes that are susceptible to non-linear effects.

Three ways to do denominator work

As Mazmanian et al.Citation22 identified, much of population health is driven not by health care interventions but by circumstances outside of the health care system. VallesCitation67 in his monograph Philosophy of Population Health Science cogently argues, in fact, that health is a social phenomenon along multiple dimensions. It is metaphysically social as per the WHO definition of health; empirically social in that the causes and effects of health and disease are related to social phenomena; and ethically social in that health promotion in a population is entwined with social empowerment. A population health science methodology, then, must account for and address this social nature of health. In many ways, this has been borne in a movement to recognize and address social determinants of health (SDOH). One might argue that such an approach is outside of the bounds of clinical medicine and more within the bounds of public health. Likewise, public health practitioners and philosophers may fear the over-medicalization of inherently social or non-clinical issues. Valles addresses this “boundary problem” of population health science and CPM by arguing, “I have no objection to limiting the professional domain or behavior of individual types of experts within interdisciplinary and intersectoral population health science, while still maintaining that population health science, as a whole, must engage with all aspects of the causes and effects of health in human populations.” Citation67(p85) In effect, the injunction of CPM is to identify areas where health professionals can participate in denominator work—and for our purposes, where CME can be employed to support such work.

An example of such an effort is a CME program delivered by the Ontario College of Family Physicians called Treating Poverty, for which authors have led the development.Citation68 Poverty is a known and important SDOH.Citation67 This live, 5-hour in-person program teaches participants to: 1) Intervene in poverty using the “Poverty Tool”; 2) Guide patients to relevant income benefit programs and critically assess income benefit programs that require physician input; 3) Build and empower a practice team to address poverty and social determinants of health; and, 4) Advocate for patients living in poverty. Using Treating Poverty as an example, we can identify three additional methods through which CME might also do “denominator work” which must more clearly be the focus of population health initiatives. These include: inverting denominator problems into numerator problems, training clinicians in population health, and attending to equity and social marginalization by disaggregating denominators.

Inverting denominator problems into numerator problems

First, objectives one and two of this innovative CME program essentially invert a “denominator problem” (poverty, an SDOH) into a clinical and “numerator problem” by providing clinicians with means and tools to assess and intervene on poverty during clinical encounters using routine clinical tasks. This aligns with the CPM function of “population health assessment,” namely diagnosing and addressing priority health problems and health hazards in the communityCitation59 and aligns with the population health approach of attending to “causes of causes” such as poverty. We can expect such an approach to decrease the specificity of the expected outcomes given the multiple kinds of effects across domains that poverty has on health,Citation69 including general measures such as all-cause mortality.Citation70

Training clinicians in population health

The third and fourth objectives identify a second means through which to connect CME to population health, namely training clinicians in population health. They help to fulfill another CPM function of putting “the right people in the right place”Citation59 by developing a clinical workforce fluent in both clinical practice and population health, which is also an important recommendation of the Lancet commission on HPE.Citation8 For those who would argue that these functions are outside of the scope of practice of physicians, as one prominent example “Health Advocate” is a clearly defined competency of the CanMEDS frameworks of the College of Family Physicians of Canada and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada,Citation71,Citation72 the accepted standards for Canadian medical education planning.

Using CME to develop a clinical workforce attuned to population medicine can further buttress the applicability of Moore et al.Citation5 toward population health. Moore et al. define a “backwards planning” approach where “representatives of clinical teams involved in the care of the target patient population should engage in discussion about the gap using the ‘5-why’s’ technique. The ‘5-why’s’ is an iterative interrogative technique used to explore the cause-and-effect relationships underlying a particular problem. The primary goal of the technique is to unearth the root cause of a defect or problem by repeating the question ‘Why?’ until no more causes are proposed.”Citation5(p906) However, if the representatives of clinical teams have no training in population health, and specifically in population health as related to but distinguishable from clinical practice, then it is unlikely that population-level root causes will be considered by such a process and thus unlikely that population-focused CME interventions will be designed. Alternatively, clinicians and education planners who are attuned to and trained in population health will be more likely to incorporate social and population perspectives as part of CME interventions. We can expect this kind of activity to impact both the specificity and scope of CME interventions and thus the expected population-level outcomes.

Attending to equity and social marginalization by disaggregating denominators

Third, a population health perspective holds the potential to bring an explicit equity-focused analysis and understanding to CME. While the traditional population health approach of Rose focuses on an entire population, an approach that incorporates an equity lens into its analysis seeks to understand and address the health and social needs of groups that have been socially marginalized. We can describe this as a process of disaggregating denominators. As Frohlich and PotvinCitation73 note, without attending to social marginalization (“vulnerable populations” in their words), population health interventions can in fact worsen social inequalities. Social marginalization not only exposes people to multidimensional adverse health risks but can also be a risk for not being able to access or benefit from population health interventions. For example, CME interventions that depend solely on improvements in clinical care to achieve population health improvements will be unlikely to impact parts of a population with barriers to accessing clinical care. To defend against this, McLaren et al.Citation74 suggest a focus of population health strategies that are more structural (i.e., social and economic) than agentic (depending on individual engagement in behavior change). This injunction aligns well with the recent accumulation of knowledge that more upstream and structural population health interventions are less likely to worsen social inequalities.Citation75

Population health focused CME programs must be able to attend to these concerns in multiple ways. In a reworking of the Treating Poverty curriculum in 2018, the curriculum development group (which included experts with lived experience of poverty and physicians with experience in social policy development) included knowledge and skills components in the workshop focused on identifying and addressing specific needs of socially marginalized groups. This included a particular focus on people who are Indigenous, Black, and/or women. In the program, participants are also guided through an examination of their own privilege and social position, as the counteracting of individual privilege is explored as an intervention to address historical and systemic drivers of inequitable health outcomes. Such an approach follows the suggestion by Frohlich and PotvinCitation73 that effective population health strategies must bridge gaps in values between population health promoters (in this case physicians who are CME participants) and socially marginalized peoples. This can also facilitate the participation of socially marginalized peoples in problem articulation, intervention development, and program evaluation. This may be one strategy through which programs can be better oriented and equipped to do the challenging work, such as disaggregating data along dimensions of social marginalization, to evaluate for differential intervention effects and specifically the potentiality of increasing social inequality. This is a persistent challenge for population health interventions even outside of CME.Citation76 Such an approach would both widen and deepen the scope of the population under consideration for CME programs and thus facilitate contention with larger populations but in nuanced ways that account for within-population dynamics.

Conclusion

Individual health care providers and health systems are increasingly expected to perform in ways that promote population health. The core competencies of medical professionals and for health professionals generally include specific references to health advocacy and community health. In their influential review of the effectiveness of CME, Cervero and Gaines cite HouleCitation77 to claim that the fundamental purpose of continuing education is “to facilitate the successful performance of practitioners in the diverse practice characteristic of professional work.”Citation14(p12) Therefore, it is essential that frameworks for the design, implementation, and evaluation of CME not only reference population health, but also provide the foundation to support population health initiatives. In this paper, we have drawn on the approaches of clinical population medicine, health equity, and philosophies of population health sciences to make some initial steps in this direction of further buttressing existing CME models to support population health outcomes. In particular, we used the concepts of outcome specificity and population scope to distinguish between the commonly considered aggregative patient health outcome from more uniquely distributive population health outcomes. Furthermore, we related this to the heuristic of “numerator and denominator work” to propose that CME must be oriented to both improving and scaling effective numerator work, which has been its traditional aggregative focus, as well as developing pathways for physicians to do varied kinds of denominator work. This can take multiple forms, such as interpreting evidence from a population prevention perspective, incorporating social determinants of health into CME activities and using CME to explicitly train a population health-oriented practice force and CME planning force.

These are not intended as an exhaustive listing of the means by which CME can effect population health change or a restrictive heuristic of only numerator and denominator work. Examples of other CME innovations, either from within or outside of opioid prescribing and poverty-focused CME or from other jurisdictions, may provide other pathways through which population health may be improved. We see this framework as elaborating on rather than displacing widely used frameworks such as those of Moore and Kirkpatrick for cases in which population health outcomes are of important concern to the CME intervention at hand. Likewise, there are a variety of additional considerations for the conduct and evaluation of population health-focused CME programs such as feasibility, evaluation methodologies, appropriate data sources, and intercalation with non-educational initiatives which will require further consideration and elaboration. Such additional considerations will likely amplify challenges that have already been raised for the adequate incorporation of patient health outcomes in medical education.Citation78

Though we have drawn primarily from the field of opioid prescribing within the context of the North American opioid epidemic to justify the imperative for a population health framework, the non-linear associations between clinical interventions and population health are not unique to this field. Complexity has increasingly been identified as a feature of many health and health care problemsCitation79 and so the insights included here should be generalizable. Finally, we have explicitly restricted our focus to CME rather than continuing health profession education generally. We elected to do this given that we have drawn from literature specifically on CME effectiveness and on clinical population medicine. We believe this framework could be adapted to continuing education in other health professions, or continuing health profession education generally, which may entail new and different considerations beyond the scope of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Drs. Whitney Berta and Ivan Silver for helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript, Dr. Aaron Orkin for better illuminating the numerator/denominator heuristic of clinical population medicine, and Mr. Darren Cheng for assistance with manuscript formatting.

Declaration of interest

Dr. Sud is the Director of and Faculty for Safer Opioid Prescribing, an opioid prescribing continuing medical education program for which he receives a stipend. Dr. Bloch received funding from the Ontario College of Family Physicians to design and deliver the Treating Poverty continuing medical education workshop.

Financial disclosure statement

Work for this project has been supported in part by the Substance Use and Addictions Program, Health Canada (1920-HQ-000031). The funder had no role in study design, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. There are no other funding sources to disclose.

References

- Moore DE, Jr., Green JS, Gallis HA. Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29(1):1–15. doi:10.1002/chp.20001.

- Farmanova E, Kirvan C, Verma J, et al. Triple aim in Canada: developing capacity to lead to better health, care and cost. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(6):830–837. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzw118.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Population health approach: the organizing framework. Public Health Agency of Canada. https://cbpp-pcpe.phac-aspc.gc.ca/population-health-approach-organizing-framework/. Published 2013. Accessed December 14, 2019.

- Ontario Ministry of Health. Patients first: action plan for health care. Ontario Ministry of Health. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/ms/ecfa/healthy_change/. Published 2019. Accessed December 14, 2019.

- Moore DE, Jr., Chappell K, Sherman L, Vinayaga-Pavan M. A conceptual framework for planning and assessing learning in continuing education activities designed for clinicians in one profession and/or clinical teams. Med Teach. 2018;40(9):904–913. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1483578.

- Belfield C, Thomas H, Bullock A, Eynon R, Wall D. Measuring effectiveness for best evidence medical education: a discussion. Med Teach. 2001;23(2):164–170. doi:10.1080/0142150020031084.

- Rose GA, Khaw K-T, Marmot MG. Rose’s Strategy of Preventive Medicine: The Complete Original Text. New ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008.

- Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5.

- Kirkpatrick DK. Evaluation of training. In: Craig RL, ed. Training and Development Handbook: A Guide to Human Resource Development. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1976:317.

- Kirkpatrick DK. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers Inc.; 2006.

- Barr H, Freeth D, Hammick M, Koppel I, Reeves S. Evaluations of interprofessional education: a United Kingdom review for health and social care. Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education. http://caipe.org.uk/silo/files/evaluations-of-interpro-fessional-education.pdf. Published 2000. Accessed April 24, 2015.

- Moore D. A framework for outcomes evaluation in the continuing professional development of physicians. In: Davis D, Barnes B, Fox R, eds. The Continuing Professional Development of Physicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Press; 2003:249–274.

- Roland D. Proposal of a linear rather than hierarchical evaluation of educational initiatives: the 7is framework. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:35. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2015.12.35.

- Cervero R, Gaines J. Effectiveness of Continuing Medical Education: Updated Synthesis of Systematic Reviews. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education; 2014.

- Al-Azri H, Ratnapalan S. Problem-based learning in continuing medical education: review of randomized controlled trials. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(2):157–165.

- Bloom BS. Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(3):380–385. doi:10.1017/s026646230505049x.

- Davis D, Galbraith R, American College of Chest Physicians Health and Science Policy Committee. Continuing medical education effect on practice performance: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 Suppl):42S–48S. doi:10.1378/chest.08-2517.

- Forsetlund L, Bjorndal A, Rashidian A, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD003030.

- Lowe MM, Bennett N, Aparicio A, American College of Chest Physicians Health and Science Policy Committee. The role of audience characteristics and external factors in continuing medical education and physician change: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 Suppl):56S–61S. doi:10.1378/chest.08-2519.

- Marinopoulos SS, Dorman T, Ratanawongsa N, et al. Effectiveness of continuing medical education. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2007;(149):1–69.

- Mansouri M, Lockyer J. A meta-analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27(1):6–15. doi:10.1002/chp.88.

- Mazmanian PE, Davis DA, Galbraith R, American College of Chest Physicians Health and Science Policy Committee. Continuing medical education effect on clinical outcomes: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 Suppl):49S–55S. doi:10.1378/chest.08-2518.

- Tian J, Atkinson NL, Portnoy B, Gold RS. A systematic review of evaluation in formal continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27(1):16–27. doi:10.1002/chp.89.

- Yardley S, Dornan T. Kirkpatrick’s levels and education ‘evidence’. Med Educ. 2012;46(1):97–106. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04076.x.

- Government of Canada. National report: apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada. Government of Canada. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/datalab/national-surveillance-opioid-mortality.html. Published 2020. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Drug overdose deaths. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Published 2019. Accessed October 25, 2019.

- Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. Opioids and Stimulant-Related Harms in Canada. In: Public Health Agency of Canada, ed. Ottawa; 2021.

- Gomes T, Khuu W, Craiovan D, et al. Comparing the contribution of prescribed opioids to opioid-related hospitalizations across Canada: a multi-jurisdictional cross-sectional study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;191:86–90. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.028.

- CIHI. Opioid Prescribing in Canada: How Are Practices Changing? Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2019.

- Ho JY. The contemporary American drug overdose epidemic in international perspective. Popul Dev Rev. 2019;45(1):7–40. doi:10.1111/padr.12228.

- Sud A, Armas A, Cunningham H, et al. Multidisciplinary care for opioid dose reduction in patients with chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic realist review. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0236419. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0236419.

- Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Ferrari A, et al. The Global Burden of Disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(12):987–1012. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7.

- Sproule B. Prescription Monitoring Programs in Canada: Best Practice and Program Review. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse; 2015.

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. Education the preferred outcome in opioid prescribing investigations. In: McNinch E, ed., Dialogue. Vol 14. Toronto, ON: College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario; 2018:19–21.

- Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2017;189(18):E659–E666. doi:10.1503/cmaj.170363.

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1–49. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1.

- Alford DP. Opioid prescribing for chronic pain-achieving the right balance through education. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):301–303. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1512932.

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Joint Statement of Action to Address the Opioid Crisis: A Collective Response (Annual Report 2016–2017). Ottawa, ON 2017.

- Webster F, Rice K, Sud A. A critical content analysis of media reporting on opioids: the social construction of an epidemic. Soc Sci Med. 2020;244:112642. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112642.

- Furlan AD, Carnide N, Irvin E, et al. A systematic review of strategies to improve appropriate use of opioids and to reduce opioid use disorder and deaths from prescription opioids. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;2(1):218–235. doi:10.1080/24740527.2018.1479842.

- Moride Y, Lemieux-Uresandi D, Castillon G, et al. A systematic review of interventions and programs targeting appropriate prescribing of opioids. Pain Physician. 2019;22(3):229–240. doi:10.36076/ppj/2019.22.229.

- Sud A, Molska G, Salamanca-Buentello F. Evaluations of continuing health provider education for opioid prescribing: a systematic scoping review. Acad Med.. 2021. Published Ahead of Print. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004186.

- Katzman JG, Comerci GD, Landen M, et al. Rules and values: a coordinated regulatory and educational approach to the public health crises of chronic pain and addiction. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):1356–1362. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.301881.

- Morton KJ, Harrand B, Floyd CC, Schaefer C, Acosta J, Logan BC, Clark K, et al. Pharmacy-based statewide naloxone distribution: A novel "top-down, bottom-up" approach. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017 Mar-Apr; 57(2S): S99–S106.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2017.01.017. PMID: 28292508.

- Cochella S, Bateman K. Provider detailing: an intervention to decrease prescription opioid deaths in Utah. Pain Med. 2011;12 Suppl 2 (Suppl 2):S73–S76. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01125.x.

- Alley L, Novak K, Havlin T, et al. Development and pilot of a prescription drug monitoring program and communication intervention for pharmacists. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16(10):1422–1430. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.12.023.

- Barth KS, Ball S, Adams RS, et al. Development and feasibility of an academic detailing intervention to improve prescription drug monitoring program use among physicians. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2017;37(2):98–105. doi:10.1097/CEH.0000000000000149.

- Eukel HN, Skoy E, Werremeyer A, Burck S, Strand M. Changes in pharmacists’ perceptions after a training in opioid misuse and accidental overdose prevention. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2019;39(1):7–12. doi:10.1097/CEH.0000000000000233.

- Spickard A, Jr., Dodd D, Dixon GL, Pichert JW, Swiggart W. Prescribing controlled substances in Tennessee: progress, not perfection. South Med J. 1999;92(1):51–54. doi:10.1097/00007611-199901000-00009.

- Sanchez-Ramirez DC, Polimeni C. Knowledge and implementation of current opioids guideline among healthcare providers in Manitoba. J Opioid Manag. 2019;15(1):27–34.

- Anderson JF, McEwan KL, Hrudey WP. Effectiveness of Notification and Group Education in Modifying Prescribing of Regulated Analgesics. CMAJ. 1996;154(1):31–39.

- Cardarelli R, Elder W, Weatherford S, et al. An examination of the perceived impact of a continuing interprofessional education experience on opiate prescribing practices. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(5):556–565. doi:10.1080/13561820.2018.1452725.

- Ontario Drug Policy Research Network. Ontario prescription opioid tool. Ontario Drug Policy Research Network. https://odprn.ca/ontario-opioid-drug-observatory/ontario-prescription-opioid-tool/. Published 2020. Accessed December 8, 2020.

- British Columbia’s Coroners Service. Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths in BC: January 1, 2010—September 30, 2020. Victoria, BC: Ministry of Public Safety & Solicitor General; 2020.

- Keyes K, Galea S. Population Health Science. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- McMichael AJ. Prisoners of the proximate: loosening the constraints on epidemiology in an age of change. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(10):887–897. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009732.

- Verweij M, Dawson A. The meaning of ‘public’ in ‘public health. In: Dawson A, Verweij M, eds. Ethics, Prevention, and Public Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007:13–29.

- Orkin AM, Bharmal A, Cram J, Kouyoumdjian FG, Pinto AD, Upshur R. Clinical population medicine: integrating clinical medicine and population health in practice. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):405–409. doi:10.1370/afm.2143.

- Orkin A. Clinical population medicine: a population health roadmap for Ontario health teams. Insights. 2019.

- Zisblatt L, Hayes SM, Lazure P, Hardesty I, White JL, Alford DP. Safe and competent opioid prescribing education: increasing dissemination with a train-the-trainer program. Subst Abus. 2017;38(2):176.

- Katzman JG, Fore C, Bhatt S, et al. Evaluation of American Indian health service training in pain management and opioid substance use disorder. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(8):1427–1429. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303193.

- Safer Opioid Prescribing. http://saferopioidprescribing.org. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- Sud A, Doukas K, Hodgson K, et al. A retrospective quantitative implementation evaluation of safer opioid prescribing, a Canadian continuing education program. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):101. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02529-7.

- Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85–92. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006.

- Busse JW, Juurlink D, Guyatt GH. Addressing the limitations of the CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2016;188(17-18):1210–1211. doi:10.1503/cmaj.161023.

- Centre for Effective Practice. Opioid tapering template. Centre for Effective Practice. https://cep.health/clinical-products/opioid-tapering-template/. Published 2018. Accessed December 12, 2019.

- Valles SA. Philosophy of Population Health Science: Philosophy for a New Public Health Era. London. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2018.

- Ontario College of Family Physicians. Treating poverty. https://cpd.ocfp.on.ca/enrol/index.php?id=95. Published 2019. Accessed December 12, 2019.

- Gupta RP, de Wit ML, McKeown D. The impact of poverty on the current and future health status of children. Paediatr Child Health. 2007;12(8):667–672. doi:10.1093/pch/12.8.667.

- Fiscella K, Franks P. Poverty or income inequality as predictor of mortality: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 1997;314(7096):1724–1727. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7096.1724.

- Frank J, Snell L, Sherbino J. Canmeds 2015 Physician Competency Framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. 2019.

- Shaw E, Oandasan I, Fowler N. CanMEDS-FM 2017: A Competency Framework for Family Physicians across the Continuum. Mississauga, ON: The College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2017.

- Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):216–221. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777.

- McLaren L, McIntyre L, Kirkpatrick S. Rose’s population strategy of prevention need not increase social inequalities in health. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(2):372–377. doi:10.1093/ije/dyp315.

- Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Welch V, Tugwell P. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(2):190–193. doi:10.1136/jech-2012-201257.

- Thomson K, Hillier-Brown F, Todd A, McNamara C, Huijts T, Bambra C. The effects of public health policies on health inequalities in high-income countries: an umbrella review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):869. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5677-1.

- Houle CO. Continuing Learning in the Professions. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1980.

- Cook DA, West CP. Perspective: reconsidering the focus on "outcomes research" in medical education: a cautionary note. Acad Med. 2013;88(2):162–167. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827c3d78.

- Sturmberg J. Embracing Complexity in Health: The Transformation of Science, Practice, and Policy. 1st ed.Springer International Publishing; 2019.