Abstract

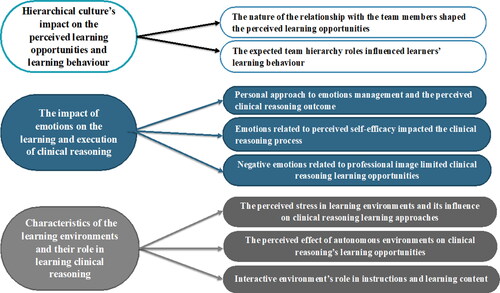

Phenomenon: As a core competency in medical education, clinical reasoning is a pillar for reducing medical errors and promoting patient safety. Clinical reasoning is a complex phenomenon studied through the lens of multiple theories. Although cognitive psychology theories transformed our understanding of clinical reasoning, the theories fell short of explaining the variations in clinical reasoning influenced by contextual factors. Social cognitive theories propose a dynamic relationship between learners’ cognitive process and their social and physical environments. This dynamic relationship highlights the essential role of formal and informal learning environments for learning clinical reasoning. Approach: My research aimed to explore the personal experience of learning clinical reasoning in a sample of postgraduate psychiatry trainee doctors using cognitive psychology and social cognitive theories. A stratified convenience sample of seven psychiatry trainee doctors working in the Mental Health Services in Qatar completed semi-structured interviews in 2020. I analyzed the data manually using theoretical thematic analysis. Findings: I identified three overarching themes with multiple subthemes. The first theme was the hierarchical cultural impact on perceived learning opportunities and learning behavior. The first theme had two subthemes that explored the relationship with team members and the expected hierarchy roles. The second theme was the impact of emotions on the learning and execution of clinical reasoning.The second theme had three subthemes that explored the personal approach to managing emotions related to perceived self-efficacy and professional image. The third theme was characteristics of learning environments and their role in learning clinical reasoning. The last theme included three subthemes that explored stressful, autonomous, and interactive environments. Insights: The results accentuate the complexity of clinical reasoning. Trainees’ experience of learning clinical reasoning was influenced by factors not controlled for in the curricula. These factors constitute a hidden curriculum with a significant influence on learning. Our local postgraduate training programmes will benefit from addressing the points raised in this study for effective and culturally sensitive clinical reasoning learning.

Introduction

Despite advancements in healthcare technology and research evidence, medical errors continue to jeopardize patient safety.Citation1–4 Medical errors are multidimensional and should be addressed at multiple levels, including medical education.Citation5 Clinical reasoning (CR) errors contribute to adverse medical outcomes and may still arise despite solid knowledge.Citation6

Cognitive theories had a revolutionary role in understanding CR by examining information organization in memory.Citation7 Information processing, organization, and retrieval increase in complexity with extensive clinical experience and instructions. Experts’ advanced non-analytical reasoning is based on recognizing patterns in the existing schemas (rich mental units).Citation7,Citation8 Cognitive theories were criticized for isolating cognition from its context when there was growing evidence of the impact of context on cognition, even among clinical experts.Citation9,Citation10 Social cognitive theories (SCT) brought a more inclusive understanding of contextual learning. The theories propose that humans behave and learn in a conceptual framework of triadic reciprocality where bidirectional relationships occur between personal factors and social and physical environments.Citation11,Citation12 Humans are viewed as active and independent learners who self-appraise and regulate through real and vicarious experiences.Citation13 Learning requires attention, retention, and motivation to reproduce the desired learning.Citation14

The situated and distributed cognitive theories are sub-theories of SCT which challenge knowledge detached from practice. They emphasize that for learning to occur, it must happen in the context in which one is expected to execute knowledge.Citation15,Citation16 Distributed cognition theory aims to understand the collective cognition of a group in a specific environment rather than examining individual cognition.Citation12 Collective cognition promotes the exchange of cognitive resources and facilitates dealing with complex CR.Citation17,Citation18

Many medical institutions developed specific CR curricula, as evidenced in international literature that supports the role of various forms of CR curricula in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education.Citation19 Undoubtedly, the previously discussed theories influenced major reform in medical curricula aiming to improve CR teaching and learning.Citation7,Citation20 These curricula accommodated cognitive development, integrated conceptual and experiential knowledge and Incorporated theoretical constructs like self-efficacy, observational and collaborative learning.Citation21–23 These curricula will likely improve further with more understanding of the contextual learning specific to the CR process. Understanding the local work culture and organizational structure is also essential for effective training.

This research explored the postgraduate psychiatry trainee doctors’ experience of CR learning in the psychiatry training programmes in the Mental Health Services of Qatar. Psychiatry was the focus of this research as CR in psychiatry may carry unique complexity compared to other medical fields. Psychiatry can be highly subjective and ambiguous, which may obscure the clarity of CR processes.Citation24 The published research in CR learning in Qatar is minimal. No previous local research addressed CR learning in psychiatry or explored CR contextual learning. My local postgraduate psychiatry curriculum does not have a specific CR curriculum either. Hence, studying the psychiatry trainees’ CR experience adds valuable insight to the specifics of the psychiatry CR processing and learning in the local context and helps understand the local contextual factors that could work as a hidden curriculum.

Methods

Ethics

The study received ethical approval from HMC-IRB (protocol number: MRC-0-19-306) on 05/11/2019 and the University of Dundee School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee (SMED REC Number 19/176) on 9/12/2019.

Setting

Historically, psychiatric care in Qatar was limited to inpatient and outpatient care provided in one centralized mental health hospital emphasizing medical management. The mental health hospital was part of a governmental public health care institution called Hamad Medical Corporation. Mental Health Services (MHS) has flourished due to the prioritization of mental health and well-being by the Qatar National Mental Health Strategy launched in 2013.Citation25 Such services were reformed to follow a bio-psycho-social model of care as this is considered the most valid approach in mental health care.Citation26 MHS was expanded to include community-integrated mental health services that provide care through multidisciplinary team members. MHS is the largest mental health service in Qatar and is the only institution that provides postgraduate psychiatry training programmes. Despite the shift in service delivery, many psychiatrists and patients continued to primarily focus on medical management. The medically focused management culture can also be found across many parts of the Middle East region. This engraved culture, coupled with the culture of traditional education where learners are relatively passive recipients of knowledge, likely perpetuated the hierarchical medical culture in MHS. MHS employees reflect demographic characteristics of Qatar, where up to 90% of the population are expatriates.Citation27 Most MHS psychiatry trainee doctors are from the Middle East region and share some cultural values.

MHS provides a four-year psychiatry residency and three-year clinical fellowship training programmes. The clinical fellowship training prepares the fellows for future roles as consultant psychiatrists. Consultant psychiatrists supervise all the trainees. There were 41 psychiatry residents and clinical fellows in MHS when the research was conducted in 2020. The training programmes follow the Accreditation Council of Medical Education (ACGME) competency framework, which did not include CR as one of the competencies when this research was conducted. There is no explicit CR curriculum in local programmes but instead, it is learned implicitly with other competencies.

Author’s reflexivity statement

I am a psychiatry specialist at MHS. This research was a part of my MSc thesis in Medical Education. I completed undergraduate studies in Sudan and postgraduate psychiatry training in Ireland. This facilitated a broader exposure to various work cultures. My teaching role in MHS involves bedside teaching and delivering some didactic lectures to psychiatry residents. I do not hold any educational leadership role or supervisory position for trainee doctors. I am not involved in the trainees’ performance evaluations or assessments. My limited role in the trainees’ teaching probably created a balance of power during data collection and likely led to candid responses. My similar clinical background, education, and work culture probably facilitated my understanding of the participants’ experiences.

Sample and recruitment

I employed a stratified convenience sample. Stratification was based on the level of training to account for the influence of experience on CR. The sample size was not predetermined, but recruitment ended when saturation was reached. I obtained the trainee doctors’ details from the psychiatry postgraduate training programmes directors. I selected three clinical fellows and three residents as potential candidates. I emailed research participation invitations, including the Participant Information Sheet and a Consent Form. I included the first responder of each group in the first round of the semi-structured interviews, which served as the initial sample. I continued to recruit more participants simultaneously with the analysis. The recruitment was guided by themes synthesized from the preliminary data analysis and the participants’ level of training. These factors allowed for including participants with extreme views and experiences. Recruitment ceased after I could no longer synthesize new themes (thematic saturation point).Citation28 This sampling technique maximised the opportunities to develop concepts, uncover variations, and identify relationships among concepts.Citation29 Seven doctors completed the interviews; five resident doctors at years 1, 2, and 4, and two clinical fellows at years 1 and 3 of training. The sample included one woman and six men. The sample’s nationalities were Qatari, Sudanese, Egyptian, Lebanese, and Pakistani. I consider this sample a representative of the trainee doctors in MHS as it includes Middle Eastern nationalities. Because of the participants’ ethnic backgrounds, I expect them to share traditional learning values. I am satisfied that the sample covered a reasonable stretch of clinical experiences, which enriched the results. The theoretical framework guiding the data collection led to clarity in the data synthesis system.

Data collection tools and ethics protections

I conducted semi-structured interviews to gather data. Participants gave written consent as a prerequisite. I audio-recorded the interview sessions and transcribed the recorded data. I kept the recordings private and was the only person who accessed them. I destroyed the recordings after the final transcripts were generated. I instructed the participants not to mention names of patients or colleagues during interviews for confidentiality purposes. I assigned each participant a code that they selected themselves from multiple choices. I used the codes to address the participants during the interviews. I also used the codes to identify the transcript sheets to maintain the interviewees’ confidentiality. No names were included. The list of participants’ names with the assigned codes was only accessible to me. I destroyed this list as soon as I completed the data analysis.

Interview structure

I informed the participants of the main task of the interview in the invitation emails. I asked them to consider Eva et al.’s definition of CR when completing the interview task, which is “the ability to sort through a cluster of features presented by a patient and accurately assign a diagnostic label, with the development of an appropriate treatment strategy as the end goal.”Citation30(p.98) The task was “to facilitate studying clinical reasoning among psychiatry trainees; you are asked to reflect on a clinical event that happened during the last six months where you think you exercised good clinical reasoning, and also on a clinical event where you think you exercised poor clinical reasoning during that same time.” I anticipated that the 6 month interval was long enough to collect informative data and short enough to reduce recall bias. The interviews were conducted individually, face-to-face, and in English. The interviews lasted for an average of 50 to 60 min. I developed a semi-structured grid to guide the discussion (Appendix). The guided interview questions were open-ended based on the research’s conceptual framework. The questions addressed the perception of their CR process and how they learned it in various work environments. I used a reflexive journal to take notes during the interviews. The choice of semi-structured interviews provided a supportive framework yet enough flexibility to synthesize the data.Citation31

Analysis

I transcribed audiotapes verbatim. I analyzed the data using thematic analysis, a tool used to extract trends and patterns in data.Citation32 It is known for its analytical flexibility as it is not bound to any specific theoretical framework.Citation33 I used thematic analysis for this data set because it accommodates exploring and reporting the participants’ perception of CR learning using theoretical frameworks of the research. I followed the steps proposed by Braun and Clark during the analysis.Citation32 A summary of the analysis steps is provided in , and examples of the identified codes are presented in . I conducted all the analysis steps, which facilitated a deep understanding of the data.

Table 1. Theoretical thematic analysis steps.

Table 2. Examples of codes generated during thematic analysis.

Study rigor/trustworthiness

This study’s trustworthiness followed the four criteria recommended by Lincoln and Guba.Citation34 My prolonged engagement with the participants, facilitated by employing semi-structured interviews, enhanced credibility through deep discussion. I had the same clinical background as the participants, which contributed to an easier understanding of the discussed experiences. I used a reflexive research journal to take notes during and after the interviews to minimize personal biases. I reviewed and reflected on the audio recordings and the journal notes after each interview to identify any biases in the discussion. Being aware of my personal biases allowed for better management of potential biases in the consecutive interviews. In addition, I was not involved in the participants’ job performance evaluation, which created a power-neutral environment that probably promoted candid participation. Member check was employed once to achieve some level of credibility. I emailed all the participants the first draft of the transcripts with my detailed analysis of the discussion. I asked the participants about their agreement with my initial interpretation of our discussion. The transcripts were sent between 8-12 weeks after each interview. There were minor disagreements with one participant that were discussed and resolved.

Results

I interviewed seven trainee doctors (five residents and two clinical fellows). Three themes were identified, each with subthemes ().

Theme 1: Hierarchical culture’s impact on perceived learning opportunities and learning behavior

Even though the local postgraduate psychiatry training programmes transitioned to a contemporary bio-psycho-social curriculum in the last two decades, the hospital culture differed. The medically focused care in the hospital promoted a hierarchical culture with the dominance of the most senior clinicians, consultant psychiatrists. The influence of the hierarchical culture on CR learning was evident. Two subthemes were identified related to the hierarchical culture.

Subtheme 1: The nature of the relationship with the team members shaped the perceived learning opportunities

I perceived consultants’ experiential knowledge as the most significant factor for identifying the consultants as the primary source of learning CR. Dr Z, 3rd year clinical fellow, emphasized the importance of mastery attained by the consultants through their extensive practical experience.

You can find someone younger than you who has more knowledge, but the clinical practice is different… I think that is why I discuss with someone senior… the experience is different from the core knowledge… what we are looking for is the experience.

On the contrary, interactions with peers focused on emotional support, informal information-sharing through storytelling, and cross-checking competencies but were not perceived to reach higher cognitive processing levels. The trainees, perhaps influenced by the hierarchical culture, minimised peer-supported CR learning.

“It is more informal… I never relied in patient management on colleagues at my level…it helps to hear similar experiences and how they dealt with… it makes me feel I am not doing anything wrong and I have the same struggles perhaps as everyone else…To be honest, speaking to the consultant would be easier because it is a teaching relationship training relationship, so I come and confess (laugh), but peers (pause), we are all peers” Dr C, 4th year resident.

Despite minimising the significance of peer-supported CR learning, the trainees cited peer relations as one of the strategies for dealing with emotions associated with CR. These relations were perceived as relatable, trustworthy, and safe with balanced power poles.

“I do not think I will be open to everyone (about poor CR), but certain people who I trust, friends and colleagues, I will discuss with them… it helps me at least in releasing the stress related to the case that I am not able to manage” Dr L, 4th year resident.

“I actually look for doctors who are senior to me, but they went through the same process and training, so they can relate… they likely worked recently in my role” Dr F, 1st year resident.

The hierarchical culture influenced the trainees’ perception of learning by modeling. The consultants were the most reported role model. The impact of modeling was enhanced further when the consultant’s actions were viewed as correct and admirable.

“I have seen some seniors who are very good communicators… I have seen how they approach patients in a way that made me learn” Dr H, 2nd year resident.

Learning by modeling was criticized by some participants for missing the experiential element and lacking standardization due to the trainees’ diverse experiences. Dr C, 4th year resident, criticised the opportunistic nature of modeled learning. “So, we observe consultants sometimes doing this, but we are not trained…no clear training to make sure that everybody is trained in this hospital on how to manage patients on polypharmacy”

Dr M, 2nd year resident, highlighted the perceived limited learning by observing intuitive CR. “So this patient came and within seconds the supervisor tells you we should give this patient olanzapine or risperidone (names of medications) and you do not understand what the diagnosis is”.

The participants’ perceptions of multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings also conformed to the hierarchy rules. The MDT meetings were limited to information sharing with no meaningful information processing. The trainees were overly dependent on the direct discussion with the consultants.

“What I noticed with MDT is a matter of taking information… they feel it is your role as a doctor to decide after taking the information… asking them what they think after taking the information is not something we do” Dr Z, 3rd year clinical fellow.

Despite trainees’ reports of the low value of MDT meetings, the influence of the interactions with MDT members cannot be ignored. Cognitive dissonance experienced by some trainees had a significant impact on their CR. Dr M, 2nd year resident, witnessed an intense response to a clinical problem from experienced nurses, which led to questioning his CR accuracy at the time. The cognitive dissonance experienced by Dr M influenced a reevaluation of his CR’s cognitive process.

“The nurses were very anxious … he was circulated by six nurses, and they had difficulties managing him… it was very impactful because two of them were senior nurses, so if they panic that means something.”

Subtheme 2: The expected team hierarchy roles influenced learners’ learning behavior

Trainees at various levels of training have adapted to the hierarchical culture differently. The junior trainees perceived the hierarchy as protective against challenging clinical cases, promoting less stressful CR learning. At the same time, the senior trainees assimilated to the cultural rules and fulfilled their expected roles within the hierarchy, which also impacted their CR.

“If they (consultants) have higher expectations of me, I will be more distracted and stressed… now I can focus on certain things in terms of knowledge and higher expectations will distract my attention and effort” Dr F, 1st year resident.

“He was under our team, and the nurse and the junior doctor tried to convince him to take his medications with no luck and that me being the senior in the team, I felt that I needed to do something influential… Yeah, I felt I must be a role model” Dr Z, 3rd year clinical fellow.

The trainees’ CR experience when moving up the team hierarchy also differed. Despite moving to a senior position in the team hierarchy, some reported clinical vulnerability and poor CR when encountering familiar clinical scenarios. Dr M, 2nd year resident, attributes poor CR to ambiguity about his position in the decision-making hierarchy.

“Unfortunately, it was my first few days in this ward when this patient was brought and I could say that I was adjusting to the ward… umm… and I was still getting to know my role and things went very fast.”

This clinical vulnerability might be a direct outcome of the consultant’s clinical dominance, which shielded some trainees from aspects of CR training and led to overreliance on the consultants. On the other hand, some consultants supported their trainees learning CR by graded exposure to complex clinical problems. The discrepant learning experiences highlighted opportunistic CR learning when no individualised CR training was available.

“Maybe the position … I was a resident at that time not a fellow (pause) so I did not feel comfortable taking decisions… the consultant had the ultimate say” Dr T, 2nd year fellow.

“I was a senior resident working in the inpatient, and my consultant told me that next week lead the round…no one else had done this before with me… that’s what I mean if the consultant is training minded, then they would do something like this” Dr C, 4th year resident.

Theme 2: The impact of emotions on the learning and execution of clinical reasoning

Emotions developed as a theme that affects both CR process and its learning. Three subthemes were identified.

Subtheme 1: Personal approach to emotions management and the perceived clinical reasoning outcome

Personal approaches to emotional management appeared to affect CR. The trainees who used emotions to leverage performance and increase motivation reported more successful CR than peers with less ability to handle emotions. Dr C, 4th year resident, acknowledged the anxiety a novel clinical experience caused. He described feeling “apprehensive” when encountering a high-risk patient with postnatal depression with suicide and infanticide risks for the first time. This apprehension was perpetuated by the patient’s lack of previous clinical assessments to guide him. “The challenge was to sort out the risk and to come to a diagnosis; this was her first encounter with psychiatry”. His awareness of the need to manage his emotions translated positively into his diagnostic reasoning. Managing emotions through cognitive and psychological preparedness led to creating a therapeutic environment that contributed to successful diagnostic reasoning. “I think the way I organized the session… I tried to structure my mind so I could capture everything I needed to know and ask about … I tried to make her as comfortable as possible so she opened up about her suicidal and infanticidal ideas, she said she could not talk to anyone before about these, and she felt very comfortable sharing with me if she did not (feel comfortable) perhaps my judgment could have been impaired”.

On the contrary, Dr T, a first-year clinical fellow, failed to recognize and manage the negative emotions that arose during an encounter with a patient and his family, which led to poor management reasoning. Shortly after the doctor discharged the patient, he was readmitted in a police-assisted involuntary admission status. Dealing with a family with highly expressed emotions led to frustration and judgmental views of the family being “biased” and “trying to take advantage of the health system”.

“Yes, I felt sorry for him, I felt he does not need to be in this environment, and this stresses him out more than being home supported by his family”

“The father appeared emotional… he was crying and described difficulties with other children at home that did not seem to have direct links to the patient, so I thought the family is biased and the patient can be managed at home”

Subtheme 2: Emotions related to perceived self-efficacy impacted the clinical reasoning process

Threats to self-efficacy had an emotional impact that affected CR negatively. Dr T’s premature discharge decision was also influenced by feeling less efficacious after treating a similar patient previously. Dr T may have tried to compensate in her CR for a previous instance of experiencing negative feelings of self-efficacy.

“I would say around the same time in the ward, there was another thing going on with another patient that was fit for discharge, but the family would not come to take him for similar circumstances, and I was not able to discharge the second patient as the family did not agree to discharge the patient”

By contrast, experiences that created positive emotions may have boosted self-efficacy and CR.

“I previously encountered a case of pseudo seizure close to this one, and I read on how to differentiate pseudo seizure from seizure”

Trainees’ self-efficacy was also boosted by external validation, especially if it was perceived as of high value. Dr H, 2nd year resident, explained how he felt when the consultant, who is perceived at the top of the clinical competency hierarchy, agreed with his CR. “Proposing the management plan, which turned out to be correct, made me feel that I could manage this case… the supervisor agreeing on this plan was a good sign to me”.

Subtheme 3: Negative emotions related to professional image limited clinical reasoning learning opportunities

Fear of professional image damage led to poor CR in many instances. Dr T described losing “confidence” in her CR under covert pressure of contradicting MDT members’ CR. “nurses identified him as low risk and a candidate for discharge, and the bed manager came by and said if you have any stable patients we need to discharge them and need to prioritize and all of that…I guess so yes, there was not enough confidence in myself when all these people were saying this”. Dr T was also concerned about being judged by her team for poor bed management, especially with repeated requests for efficient bed usage by ward staff. She felt “pressured by the bed crises” “all the people that need to get into the hospital and to this acute care and they were not able to because other people are occupying beds while they should be moving along”

Negative emotional experiences, including embarrassment about exposing clinical vulnerability, limited the trainees’ reflection on poor CR experiences. These negative emotions were more prominent in the context of hierarchical culture.

“I find talking to consultants more formal, and the questions that I find silly myself, I find it difficult to ask them… sometimes you may encounter a consultant who does not even know your name, so If you ask silly questions and this is the first encounter with him he is going to hold a wrong impression for a long time” Dr F, 1st year resident.

Dr C, 4th year resident, identified negative feelings provoked by contact with other team members. Dr C reported feeling “overwhelmed” when he received written feedback from the clinical pharmacist’s audit of a patient’s polypharmacy management. This feeling led to a rapid medication adjustment, precipitating the patient’s relapse. “So, I was overwhelmed by the input from the clinical pharmacist, and I felt I needed to do something quickly to fix the medications”. Dr C probably did not want to be perceived as deviating from a specific culture of prescribing practice the clinical pharmacists advocate. “That urge (reduce medications quickly) was influenced by what we hear from the clinical pharmacist; whenever we have a patient on many medications, the clinical pharmacist jumps in and says this is polypharmacy and we should not do this, we have to minimize and optimize medications…so that is always on my mind”. Deviation from what is perceived as the best practice might threaten the learner’s perceived professional image.

Theme 3: Characteristics of the learning environments and their role in learning clinical reasoning

Each learning environment carries unique complexities due to various environmental elements. Three subthemes were identified upon examining contextual CR learning.

Subtheme 1: The perceived stress in learning environments and its influence on clinical reasoning learning approaches

Stress in the learning environments may originate from either internal factors related to the trainee or external factors related to the surroundings, or both. Night duties in the Emergency Department were a good example of internal factors (sleep deprivation and fatigue) and external factors (time pressure, acutely ill patients with heightened emotions, and a noisy environment).

“I do not prepare well in terms of sleep, so lots of times a decision is made, and in the morning I feel that I am not happy with the decision…the Emergency Department can be challenging… you go to the patients who are already waiting for several hours, so they already built some degree of frustration before I intervene” Dr L, 4th year resident.

With the perceived powerful role of the consultants, the trainees described emotional elements in their interactions with consultants that affected the CR learning environment. The perceived power imbalance possibly mediated the rise of emotions. Hence, the trainees put the consultants responsible for creating a safe learning environment.

“It depends on the consultant; a lot of people in residency are afraid to voice their opinion if they disagree… they are afraid of embarrassment, afraid of how this will reflect on their evaluation” Dr T, 1st year clinical fellow.

“I was with one of the best supervisors… he used to make an introduction… I am quoting him… ‘I am asking you this question not because I am examining you just to have healthy communication’” Dr H, 2nd year resident.

The complexity and ambiguity of the clinical problems worked as an external stressful factor. Patients with severe enduring mental illness present with multiple challenges, including cognitive and communication deficits, stigma, and obscure illness insight that complicates the clinical picture.

“It was not a typical case of the acutely disturbed patient that you would easily say the patient is not well and you should keep him in the hospital… we are mostly used to patients being brought when they are in full relapse… but he was very quiet, and there was nothing apart from talkativeness, he accepted medications and was saying all the right things” Dr T, 1st year clinical fellow.

Subtheme 2: The perceived effect of autonomous environments on clinical reasoning learning opportunities

The learning environment characterized by a degree of autonomy was perceived to facilitate CR learning. The autonomy was accompanied by a sense of responsibility to manage learning.

“I have to make my own decision based on my discretion to discuss with someone or not… in some cases, it is unnecessary” Dr M, 2nd year resident.

“When I feel that I may not do the best thing for the patient because of my lack of knowledge or experience, I feel that I should protect the patient first from my ignorance (laugh)” Dr C, 4th year resident.

Dr C used his advantageous position as the front-line psychiatrist in the Emergency Department to deliver a patient-centred management plan founded on his knowledge of hospital resources. “But knowing what resources we have in the inpatient unit will sometimes make me err on the side of not admitting this patient as she is likely not to benefit from it”.

Hospital-based outpatient clinics also provide autonomous environments. Clinics have the least input from MDT compared to other settings; hence, the sense of individual ownership was greater.

“It was no pressure from anybody else to take any decision, there was direct contact with the patient… no middle person… outpatient setting is more relaxed” Dr T, 1st year clinical fellow.

Some trainees enjoyed autonomy in the supervision sessions with the consultants, which were perceived as learner-centred environments.

“Ward rounds are more clinically oriented and guided by whatever cases that we have but in supervision you have the freedom to choose the topics… just discuss whatever you want” Dr L, 4th year resident

Subtheme 3: Interactive environment’s role in instructions and learning content

Environments that provided opportunities for self-reflection on real clinical experiences supported by formal or informal discussion were perceived to improve CR learning. Case discussions were perceived to consolidate knowledge and boost confidence over time.

“The more patient I saw and discussed, the more I realize I am more competent” Dr H, 2nd year resident.

The case presentation teaching activity provides a complete story of the CR of the indexed case. This helped learners to have a comprehensive chronological understanding of the CR process. The anxiety associated with the formality of the discussion was perceived as a motivator to better performance.

“In the educational activity, there is a real case… it helps you learn because it is like a patient that you see… it is presented from the time it was seen in the hospital and what interventions were done… how to diagnose and how to manage” Dr M, 2nd year resident.

“Like if you know that this case will be discussed with a group of seniors, most likely at the back of your mind, you know that you need to make more efforts … If it is informal… aaamm… I do not think I will make more efforts” Dr Z, 3rd year clinical fellow.

On the other hand, the informal discussion was described as sharing stories in a relaxed environment. The informal discussion was mainly among peers outside the formal clinical environment. Informal discussions also substituted for some of the training deficits.

“Others may learn something from my story, and I may learn from them” Dr M, 2nd year resident.

“I cannot remember any training activities with the title (managing resources) but the interpersonal discussion with the other residents, fellows and consultants improved my skills in this area” Dr H, 2nd year resident.

Learning environments that lacked interactivity were perceived to contribute to superficial learning.

“The thing is, with these didactic sessions, we remember 10 to 20% of what was taught in the session, so what I remember from the session is things that I had an experience in or I did not do well in it, so when I discuss it clicks, and then I say I have to do this the next time” Dr C, 4th year resident.

Both junior and senior trainees praised the series of interview sessions that were part of the teaching activities in the first year of residency. The trainees valued the structured interactive simulation coupled with constructive feedback. Other reported valuable elements included a conducive learning environment, protected learning time, and a close to real-life experience yet free from normal work pressure.

“In year one we had interview skills sessions… one resident interviewed the patient and the rest observed and offered feedback…the resident had to reflect on it… I remember it helped with the critical reflection being observed and receiving feedback” Dr C, 4th year resident.

“Time dedicated to learning … it has a limited number of people, and you prepare in advance, and it is not part of the service, so you do not have to write notes or medications, just interview the patient… the sessions were very efficient” Dr F, 1st year resident.

Discussion

Evaluating the contextual factors of the learning/working environment provided insight into the dynamic relationship between the trainees’ cognition, emotions, and the other elements surrounding them.

Hierarchical culture’s impact on the perceived learning opportunities and the learning behavior

The team hierarchical culture significantly impacted the trainees’ perceived CR learning. The consultants were perceived as the most influential role models, and the consultant-centred learning environments as more conducive to CR learning. Similar to the findings in this study, previous research on the attributes of learning by modeling suggested clinical competence as one of the frequently cited factors by the trainees.Citation35–37 In this sample, the trainees’ attention and memory, which are components of learning by observation, were selective to the consultants’ behavior, while other learning resources were downplayed.Citation14 The consultants’ centrality in CR learning likely minimised the potential benefit of cognitive exchange and observational learning when working with MDT. Peer-based learning, which provides an excellent power-neutral learning experience, was also minimized.Citation38,Citation39 Self-efficacy and motivation, which are central to executing modeled behavior, were also responsive to the hierarchical cultural values and the social rules of the clinical environment.Citation40 This response varied between empowerment and oppression. The hierarchical culture was also linked to emotions; this likely resulted from the power imbalance within the team and affected the trainees’ learning behavior. The hierarchal environments provide minimal distributed cognitions and demote creativity by limiting exposure to diverse behavior.Citation40

The impact of emotions on the learning and execution of clinical reasoning

The impact of emotions on CR learning was complex and linked to multiple factors related to CR learning, including two other themes in this research. Their perceived value of clinical team relationships and the stress level associated with the learning environment affected trainees’ emotions. Similar to this research, trainees perceived that team dynamics carried an emotional burden and affected clinical decision-making in previous work.Citation41 The team hierarchical culture created stressful learning environments for some learners. The trainees’ response differed from accelerated performance stimulated by the desire to impress the consultant to avoidance behavior and burnout when stress exceeded the trainees’ psychological abilities. Excessive worry about exposing vulnerabilities and damaging one’s professional image drove this avoidance coping strategy . The trainee’s opinion on the consultants’ responsibility in creating a psychologically safe learning environment is consistent with previous research.Citation42,Citation43 The trainees’ emotional responses can also be understood using the self-efficacy construct from a social-cognitive learning perspective. Self-efficacy, which correlates with performance, is boosted by positive emotions from previously successful experiences and vice versa.Citation44,Citation45 Self-efficacy-related emotions in this research showed context specificity, and the trainees linked their beliefs, emotions, and the subsequent CR to previous similar clinical contexts. Emotions compete with and manipulate cognitive resources, leading to cognitive overload.Citation46 Learning environments would only support the trainees with poor self-efficacy if constructed to facilitate graded exposure to stress to eliminate avoidance behavior.Citation40 Hence, learning tasks can be structured to minimize emotions and cognitive overload to support the learners, especially the vulnerable ones. Also, learning to acknowledge and reflect on the emotional cues in clinical encounters, which are typically difficult to control, enhances the clinician’s CR.Citation47,Citation48

Characteristics of learning environments and their role in learning clinical reasoning

The characteristics of the learning environment were also perceived to influence learning. Trainees favoured clinical environments that provided a degree of learning autonomy. The autonomy likely facilitated meeting their perceived personal needs and improved their motivation to learn.Citation49,Citation50 The interactive environment that enabled instant or latent constructive feedback was favored compared to a destructive or no feedback environment. Constructive feedback is also likely to enhance self-efficacy, while destructive feedback causes negative emotions and may lead to feedback avoidance.Citation51,Citation52 A psychologically unsafe environment, in addition to demoting self-efficacy, may decrease learners’ satisfaction and reduce the effectiveness of debriefing and feedback.Citation42,Citation53 It can also increase learners’ avoidance behavior, diminishing reflective learning opportunities.Citation53 Teachers can promote a psychologically safe learning environment that views learning as a continuous process of knowledge and skill development rather than a medium to display mastery.Citation53 Effective learning strategies that promote psychological safety may include connecting affective and cognitive experiences, facilitating peer support, challenging the existing medical hierarchical cultures and the negative views of making mistakes.Citation42,Citation54,Citation55 Environments detached from the clinical environments, like didactics, were considered dull, with minimal experiential or vicarious learning opportunities. These environments were not perceived to facilitate deep learning. Only learners who can reflect critically and practice reflectively can link taught materials to previous experiences.Citation56 The successful brief experience of the trainees with simulation learning advocates for extending this activity across all levels of training. Face-to-face or online simulation is an innovative and effective method of teaching CR in the medical field.Citation57–61 Simulation provides situated cognitive learning that can be manipulated to offer graded exposure to clinical environments considering learners’ specific needs. Unlike busy clinical environments, simulation sessions allow ample time for constructive feedback that further boosts self-efficacy.

Limitations

The sample size in this research might be considered small. However, there is no consensus on the sample size for qualitative research. The literature cites that saturation can be achieved by as little as five participants to a bigger sample reaching up to 400 participants.Citation62–65 Achieving enough depth of information can justify small sample sizes. Also, this sample represented a relatively small and homogenous population which may justify its size. Despite the different nationalities of the participants, I assumed that they share the traditional teaching and learning culture prevalent in the Middle East region. Based on my knowledge of the programmes, I assumed the sample was representative of the trainees’ nationalities. These assumptions are based on my knowledge of Middle Eastern culture. They could represent personal biases of the participants’ culture, which I was aware of during data collection and analysis. Due to limited resources, I did not oversample to test saturation nor piloted the semi-structured interview questions.Citation66 A single-author study brought some limitations to the methodology and the results. Verification of the collected data and analysis by another researcher could have minimized bias and improved rigor. Despite these limitations, I expect this research to have acceptable transferability facilitated by the detailed description of the research process, which allows the reader to judge its transferability to different settings. The psychiatry educational programmes in the neighbouring countries, which share similarities in culture, medical institutions’ structure, and the implementation of ACGME-accredited curricula, are the most suitable setting for transferring the results.

Summary and recommendations

It is important to note that much of CR learning was influenced by factors not controlled for in the curricula. Culture impacts learning and behaviour constructed in a social context.Citation67,Citation68 The hierarchical culture’s prominent role in CR learning is an example of cultural influence on CR. The learners who focus on the consultants may fail to learn collaborative multidisciplinary teamwork; this may lead to a CR that focuses on medical management and neglects the psychological and social factors necessary for holistic mental illness management. Self-efficacy and performance decline in organizations with highly centralised and formal cultures.Citation69 The training programmes will benefit from implementing strategies to change the hierarchical culture through decentralised activities, structured peer-supported activities, promoting multidisciplinary work, and, most importantly, faculty development programmes.

Emotions emerged as a significant factor in trainees’ CR learning, and they should be factored into any educational review or development for effective educational designs. Trainees taught CR in an artificial classroom environment free of stress and emotions will likely face CR difficulties when working in clinical environments. The complexity of real clinical cases in clinical environments carries a significant emotional and cognitive load that impacts the CR process. The trainees’ abilities to deal with stress and emotions certainly show individual variation; therefore, early educational interventions that teach how to manage the affective state and reduce stress while learning CR will facilitate the desired learning. Simulation can be considered to enable graded exposure to stress by manipulating the learning environment.

The previously discussed factors constitute a hidden curriculum and have an influential role in learning. MHS postgraduate training programmes will benefit from addressing the points raised in this study for effective and culturally sensitive CR learning.

Acknowledgement

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. I would like to acknowledge the enormous support of the MHS and the psychiatry trainees. I also would like to thank Dr Bonnie Lynch of the University of Dundee for her excellent supervision of the MSc thesis, of which this paper is part.

Disclosure statement

I have no conflict of interest. The research did not receive any funds or grants.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Eva KW, Hatala RM, Leblanc VR, Brooks LR. Teaching from the clinical reasoning literature: combined reasoning strategies help novice diagnosticians overcome misleading information. Med Educ. 2007;41(12):1152–1158. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02923.x.

- Pinnock R, Welch P. Learning clinical reasoning. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014;50(4):253–257. doi:10.1111/jpc.12455.

- WHO. Patient Safety - Data and Statistics. Published 2017. https://www.who.int/patientsafety/policies/en/%0D. Accessed November 1, 2020.

- Rodziewicz T, Hipskind J. Medical Error Prevention - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. StatPearls Publishing. Published 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499956/. Accessed November 1, 2020.

- Connor DM, Durning SJ, Rencic JJ. Clinical reasoning as a core competency. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1166–1171. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003027.

- Norman G, Eva K. Diagnostic error and clinical reasoning. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):94–100. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03507.x.

- Schmidt HG, Mamede S. How cognitive psychology changed the face of medical education research. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2020;25(5):1025–1043. doi:10.1007/s10459-020-10011-0.

- Süß HM, Oberauer K, Wittmann WW, Wilhelm O, Schulze R. Working-memory capacity explains reasoning ability - And a little bit more. Intelligence. 2002;30(3):261–288. doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(01)00100-3.

- Case K, Harrison K, Roskell C. Differences in the clinical reasoning process of expert and novice cardiorespiratory physiotherapists. Physiotherapy. 2000;86(1):14–21. doi:10.1016/S0031-9406(05)61321-1.

- Cuthbert L, Teather D, Teather B, Sharples M. Expert/novice differences in diagnostic medical cognition - A review of the literature. In: Cognitive Science Research Paper; 1999:1–33, February. doi:10.1.1.136.978.

- Bandura A. Six Theories of Child Development. Vol. 6. JAI Press; 1989.

- Torre D, Durning SJ. Social cognitive theory: thinking and learning in social settings. In: Cleland J, Durning SJ, eds. Researching Medical Education. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015:105–116. doi:10.1002/9781118838983.ch10.

- Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol. 1989;44(9):1175–1184. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175.

- Bandura A. Observational learning. In: Wolfgang D, ed. The International Encyclopedia of Communication. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008:1–3. doi:10.1002/9781405186407.wbieco004.

- Brown JS, Collins A, Duguid P. Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educ Res. 1989;18(1):32–42. doi:10.3102/0013189X018001032.

- Wilson AL. The promise of situated cognition. New Directions Adult Continuing Educ. 1993;1993(57):71–79. doi:10.1002/ace.36719935709.

- Olson APJ, Durning SJ, Fernandez Branson C, Sick B, Lane KP, Rencic JJ. Teamwork in clinical reasoning – cooperative or parallel play? Diagnosis. 2020;7(3):307–312. doi:10.1515/dx-2020-0020.

- Mayo AT, Woolley AW. Teamwork in health care: Maximizing collective intelligence via inclusive collaboration and open communication. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(9):933–940. doi:10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.9.stas2-1609.

- Cooper N, Bartlett M, Gay S, et al. Consensus statement on the content of clinical reasoning curricula in undergraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2021;43(2):152–159. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1842343.

- Monrouxe LV, Beck E, Da Silva ALS, Mukhalalati B. Applications of social theories of learning in health professions education programs: A scoping review. Front Med. 2022;9:912751. https://www.researchregistry.

- Colbert CY, Graham L, West C, et al. Teaching metacognitive skills: Helping your physician trainees in the quest to “know what they don’t know. Am J Med. 2015;128(3):318–324. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.11.001.

- Kosior K, Wall T, Ferrero S. The role of metacognition in teaching clinical reasoning: Theory to practice. Educ Health Prof. 2019;2(2):108. doi:10.4103/EHP.EHP_14_19.

- Marcum JA. An integrated model of clinical reasoning: Dual-process theory of cognition and metacognition. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(5):954–961. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2012.01900.x.

- Fernando I, Cohen M, Henskens F. A systematic approach to clinical reasoning in psychiatry. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(3):224–230. doi:10.1177/1039856213486209.

- Sharkey T. Mental health strategy and impact evaluation in Qatar. BJPsych Int. 2017;14(1):18–21. doi:10.1192/s2056474000001628.

- Tripathi A, Das A, Kar S. Biopsychosocial model in contemporary psychiatry: Current validity and future prospects. Indian J Psychol Med. 2019;41(6):582–585. doi:10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_314_19.

- Online Qatar. Qatar population and expat nationalities. Published 2019. https://www.onlineqatar.com/visiting/tourist-information/qatar-population-and-expat-nationalities. Accessed January 4, 2023.

- Sebele-Mpofu FY. Saturation controversy in qualitative research: Complexities and underlying assumptions. A literature review. Cogent Soc Sci. 2020;6(1). doi:10.1080/23311886.2020.1838706.

- Butler AE, Copnell B, Hall H. The development of theoretical sampling in practice. Collegian. 2018;25(5):561–566. doi:10.1016/j.colegn.2018.01.002.

- Eva KW. What every teacher needs to know about clinical reasoning. Med Educ. 2005;39(1):98–106. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01972.x.

- Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. Br Dent J. 2008;204(6):291–295. doi:10.1038/bdj.2008.192.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Alhojailan MI. Thematic analysis : A critical review of its process and evaluation. In: WEI International European AcademicConference Proceedings. Vol. 1;2012:8–21.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions Program Eval. 1986;1986(30):73–84. In: doi:10.1002/ev.1427.

- Bahmanbijari B, Beigzadeh A, Etminan A, Rahmati Najarkolai A, Khodaei M, Seyed Askari SM. The perspective of medical students regarding the roles and characteristics of a clinical role model. Electron Phys. 2017;9(4):4124–4130. doi:10.19082/4124.

- Wright S. Examining what residents look for in their role models. Acad Med. 1996;71(3):290–292. doi:10.1097/00001888-199603000-00024.

- Yazigi A, Nasr M, Sleilaty G, Nemr E. Clinical teachers as role models: Perceptions of interns and residents in a Lebanese medical school. Med Educ. 2006;40(7):654–661. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02502.x.

- Perversi P, Yearwood J, Bellucci E, et al. Exploring reasoning mechanisms in ward rounds: A critical realist multiple case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):643. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3446-6.

- Tolsgaard MG, Kulasegaram KM, Ringsted CV. Collaborative learning of clinical skills in health professions education: The why, how, when and for whom. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):69–78. doi:10.1111/medu.12814.

- Bandura A. Self-Efficacy. In: Ramachaudran VS, ed. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. Academic Press; Vol 4;1994:71–81.

- Bucknall T. The clinical landscape of critical care: nurses’ decision-making. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43(3):310–319. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02714.x.

- Torralba KD, Jose D, Byrne J. Psychological safety, the hidden curriculum, and ambiguity in medicine. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(3):667–671. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04889-4.

- McClintock AH, Kim S, Chung EK. Bridging the gap between educator and learner: The role of psychological safety in medical education. Pediatrics. 2022;149(1):e2021055028. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-055028.

- Brown MJ. Relationship between stress management self-efficacy, stress mindset, and vocational student success [Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences]. Minneapolis, MN: Walden University; 2020.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychologist. 1982;37(2):122–147. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122.

- Plass JL, Kalyuga S. Four ways of considering emotion in cognitive load theory. Educ Psychol Rev. 2019;31(2):339–359. doi:10.1007/s10648-019-09473-5.

- Kozlowski D, Hutchinson M, Hurley J, Rowley J, Sutherland J. The role of emotion in clinical decision making: An integrative literature review. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):255. doi:10.1186/s12909-017-1089-7.

- Langridge N, Roberts L, Pope C. The role of clinician emotion in clinical reasoning: Balancing the analytical process. Man Ther. 2016;21:277–281. doi:10.1016/J.MATH.2015.06.007.

- Bush T. Overcoming the barriers to effective clinical supervision. Nurs Times. 2005;101(2).

- Edwards D, Burnard P, Hannigan B, et al. Clinical supervision and burnout: The influence of clinical supervision for community mental health nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(8):1007–1015. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01370.x.

- Whitman MV, Halbesleben JRB, Holmes O. Abusive supervision and feedback avoidance: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. J Organiz Behav. 2014;35(1):38–53. doi:10.1002/job.1852.

- Karl KA, O’Leary-Kelly AM, Martocchio JJ. The impact of feedback and self‐efficacy on performance in training. J Organiz Behav. 1993;14(4):379–394. doi:10.1002/job.4030140409.

- Driessen E, Van Tartwijk J, Dornan T. Teaching rounds: the self critical doctor: helping students become more reflective. BMJ. 2008;336(7648):827–830. doi:10.1136/bmj.39503.608032.AD.

- Korthagen F. Linking practice and theory: The pedagogy of realistic teacher education In Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Vol 28; 2001:4–17.

- Aronson L. Twelve tips for teaching reflection at all levels of medical education. Med Teach. 2011;33(3):200–205. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2010.507714.

- Stice JE. Using Kolb’s learning cycle to improve student learning. Engineering Education. 1987;77(5):291–296.

- Cleary TJ, Battista A, Konopasky A, Ramani D, Durning SJ, Artino AR. Effects of live and video simulation on clinical reasoning performance and reflection. Adv Simul. 2020;5(1):17. doi:10.1186/s41077-020-00133-1.

- Isaza-Restrepo A, Gómez MT, Cifuentes G, Argüello A. The virtual patient as a learning tool: A mixed quantitative qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):297. doi:10.1186/s12909-018-1395-8.

- Keiser MM, Turkelson C. Using simulation to evaluate clinical performance and reasoning in adult-geriatric acute care nurse practitioner students. J Nurs Educ. 2019;58(10):599–603. doi:10.3928/01484834-20190923-08.

- Plackett R, Kassianos AP, Kambouri M, et al. Online patient simulation training to improve clinical reasoning: A feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):245. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02168-4.

- Watari T, Tokuda Y, Owada M, Onigata K. The utility of virtual patient simulations for clinical reasoning education. IJERPH. 2020;17(15):5325. doi:10.3390/ijerph17155325.

- Boddy CR. Sample size for qualitative research. Qual Mark Res. 2016;19(4):426–432. doi:10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053.

- Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114523. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523.

- Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qual Health Res. 2017;27(4):591–608. doi:10.1177/1049732316665344.

- Fugard AJB, Potts HWW. Supporting thinking on sample sizes for thematic analyses: A quantitative tool. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2015;18(6):669–684. doi:10.1080/13645579.2015.1005453.

- Yang L, Qi L, Zhang B. Concepts and evaluation of saturation in qualitative research. Adv Psychol Sci. 2022;30(3):511–521. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2022.00511.

- Durning SJ, Artino AR, Boulet JR, Dorrance K, van der Vleuten C, Schuwirth L. The impact of selected contextual factors on experts’ clinical reasoning performance (does context impact clinical reasoning performance in experts?). Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17(1):65–79. doi:10.1007/s10459-011-9294-3.

- Rencic J, Schuwirth LWT, Gruppen LD, Durning SJ. Clinical reasoning performance assessment: Using situated cognition theory as a conceptual framework. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7(3):241–249. doi:10.1515/dx-2019-0051.

- Mustafa G, Glavee-Geo R, Gronhaug K, Saber Almazrouei H. Structural impacts on formation of self-efficacy and its performance effects. Sustainability. 2019;11(3):860. doi:10.3390/su11030860.

Appendix

Semi-structured interview structure:

Tell me about the context in which this event occurred.

What made CR easy? What made it difficult?

What factors related to you affected your CR?

What factors related to the patient affected your CR? Are any other factors that influenced your CR?

What were the resources available to you? How did this reflect on your CR?

What previous educational events had influenced your CR in this indexed case?

What was the influence of your regular educational activities on your CR in this instance?