?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Research Findings: This study examined the associations between early childhood education (ECE) teachers’ pre-service education (PE), professional development (PD) experiences, ECE quality, and child development. The participants included 52 teachers and 706 children from 52 preschool classes in Shanghai and Guizhou. Teacher educational level was associated with classroom interaction quality. The frequency and diversity of PD activities that ECE teachers experienced in the past year were also related to overall ECE quality. Mediational analyses indicated that the diversity and frequency of PD were indirectly associated with child development through ECE quality. Region of residence moderated the associations between PE and child development and between ECE quality and child development. Practice or Policy: Together, the findings highlight the need for policy to support ECE teachers’ professional learning from pre-service education to ongoing professional development.

Early childhood education (ECE) programs are expanding at an unprecedented pace in middle-income countries, and it is important that the teachers of these programs provide children with high-quality early learning experiences (Yoshikawa et al., Citation2015). Therefore it is essential to enhance the quality of the ECE workforce through pre-service education (PE) and professional development (PD; Brunsek et al., Citation2020). PE refers to completing a formal teacher training program before joining the profession. Pre-service teacher education programs generally vary in admission requirements and length of specialized training (Lin & Magnuson, Citation2018). The term PD denotes activities that develop teachers’ knowledge, skills, and expertise when they are already working as teachers (Brunsek et al., Citation2020).

Various modalities have been used to promote teachers’ PD. These include traditional lecture-based workshops, conference attendance, and feedback from supervisors based on classroom observations. These PD activities may target different aspects of teaching and learning in the early years, ranging from general pedagogical knowledge (e.g., classroom management) to domain-specific pedagogical content knowledge and skills (e.g., knowledge about emergent literacy and pedagogical knowledge on how to facilitate it). Enhancing the quality of ECE teachers through PE and PD is widely viewed as an effective strategy to improve ECE quality (Egert et al., Citation2018).

The definition of what constitutes high-quality ECE provision varies across cultures and contexts. That stated, there is general agreement that some dimensions of structural quality (e.g., availability of materials and infrastructure) and process quality (e.g., teacher-child interaction and children’s learning experience) are important indicators of quality, regardless of context. Most of the studies that have evaluated the association between teacher quality and classroom quality have yielded inconsistent findings and have been conducted in Western and developed countries (Early et al., Citation2007; Egert et al., Citation2018; Manning et al., Citation2019). Limited attention has been paid to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where the majority of the world’s children live and where ECE teachers typically receive lower levels of PE and fewer opportunities for PD than their counterparts in high-income countries (Neuman et al., Citation2015). The extent to which professional learning experiences shape teacher practices and affect student learning in LMICs remains unclear.

China operates the world’s largest ECE system, and the national government is committed to increasing access to and the quality of ECE, as evidenced by the increasing investment in the sector (National People’s Congress, Citation2019). The country is also focusing on strengthening the ECE workforce by expanding the scope of PE and PD. However, scant research attention has been paid to the evaluation of the role of PE and PD on classroom quality and child development. Furthermore, only a handful of studies (Hu et al., Citation2020; Hu, Fan, et al., Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2020) have examined the associations between ECE teachers’ PD and child development, and these studies have yielded inconsistent findings on the role of PD on ECE quality and child development. In the current study, we expand on previous work, examine the associations between ECE teachers’ PE, PD, ECE quality, and child development in China, and consider whether such associations vary across regions and urban – rural areas.

Association Between PE, PD, and ECE Quality

It is generally assumed that ECE teachers’ PE is important for ECE quality and, in turn, for child development. There is an increasing call for ECE teachers to have obtained at least a bachelor’s degree (Early et al., Citation2007). However, contrary to common perception, the evidence does not consistently indicate that ECE teachers with Bachelor’s degrees provide higher-quality ECE. A recent meta-analysis found that only 36 out of 72 effect sizes in 45 studies reported positive but small effects of ECE teachers’ PE on ECE quality, whereas the rest found no significant effect of teachers’ levels of education on ECE quality (Manning et al., Citation2019).

The inconsistent and sometimes contradictory research evidence about the influence of PE has led to a sharper focus on a broader range of PD activities to support pedagogical practices and children’s learning. According to the National Professional Development Center on Inclusion (National Professional Development Center on Inclusion [NPDCI], Citation2008), three aspects are core to the success of PD programs: the “Who,” the “How,” and the “What.” The effectiveness of PD is related to “Who” provides and receives PD; the “How” refers to the approaches and modalities of PD; and the “What” refers to the content of PD. PD provided by different stakeholders may represent different experiences and may vary considerably. Those organized and provided by local education departments and higher education institutions may differ from school-based PD activities as outside experts can bring in their unique expertise. For example, Gerde and Powell (Citation2009) found that PD which involved researchers relied more heavily on evidence-based knowledge and practices. Yet, recent meta-analyses on which models of PD delivery are the most effective have yielded inconclusive findings. A combination of different delivery models (e.g., PD which incorporates on-site observation, consultation, and workshops) may not necessarily be as effective as those approaches which adopt a single delivery model (Egert et al., Citation2018). PD programs with coaching components are more effective than those that do not have a coaching element (Brunsek et al., Citation2020; Egert et al., Citation2018). No firm conclusion can be drawn on the frequency necessary for PD to be deemed effective in meeting its objectives, but extant studies indicate that sufficient time must be spent on PD and the amount of time necessary will vary depend on the objectives of the PD topic (Brunsek et al., Citation2020). In summary, effective PD should involve outside experts, actively engage teachers, and be of sufficient quantity (Desimone, Citation2009; Guskey & Yoon, Citation2009). Encouragingly, evidence indicates that PD with the abovementioned features has moderate positive effects on ECE quality (Egert et al., Citation2018; Markussen-Brown et al., Citation2017). In contrast, PD seems to yield a much smaller, albeit significant, effect on child learning than does ECE quality. As Markussen-Brown et al. (Citation2017) indicated, the effect of PD has to be substantial to translate into better learning outcomes for children.

Desimone (Citation2009) proposed a Theory of Change model to understand the different proximal and distal influences on teacher learning. Desimone’s (Citation2009) model posits that teachers’ learning through PE and PD leads to changes in teachers and, in turn, changes in child development. This process is also influenced by the surrounding contexts (e.g., the school environment, curriculum, and policy). The mediating effect of classroom quality between PD and child development has been documented in children’s science learning (Gropen et al., Citation2017; Piasta et al., Citation2015). However, in a review of 25 studies, Markussen-Brown et al. (Citation2017) revealed that classroom process quality did not mediate the relation between PD and children’s language and literacy development. In general, their findings only permit the tentative conclusion that PD may influence certain aspects of children’s development through classroom quality.

Furthermore, most PD programs that have had significant impacts on ECE quality and child development have been designed and delivered by researchers under controlled conditions (Powell et al., Citation2010). Large-scale and educator-led PD programs in a real-world context have not been as effective as anticipated, which indicates the variability and complexity of PD, especially in authentic settings (Powell et al., Citation2010). In addition, most PD interventions target language and literacy (Schachter, Citation2015). Although the focus on language and literacy may be intentional as they are the basis for learning in other domains, the lack of research attention paid to other domains may lead to an incomplete understanding of the association between PD and children’s overall development.

The Case of China

The Chinese Context

In China, teachers need to obtain post-secondary diplomas in ECE prior to teaching in an ECE setting (Ministry of Education [MoE], Citation2012). National directives to enhance PE for ECE quality have been in place since 2010. By 2018, 80.97% of ECE teachers had obtained at least associate degrees (Ministry of Education [MoE], Citation2019). However, significantly fewer ECE teachers (22.72%) held Bachelor’s degrees than teachers in primary schools (59.1%) and junior secondary schools (86.22%; MoE, Citation2019). The Chinese government has mandated PD for ECE teachers. The MoE decrees a minimum of 360 hours of PD participation in a 5-year cycle for all teachers and specifies that 5% of preschool budgets should be reserved to support teacher PD (MoE, Citation2012). ECE teachers can access a wide range of PD programs offered by external providers, such as provincial and local educational bureaus, teacher education institutions, and other commercial companies. Among them, local educational bureaus are obligated to organize regular fee-free PD activities for teachers in their administrative districts. Participants must pay for certification programs provided by teacher education institutions. Commercial companies, usually textbook distributers and teacher training companies, provide PD of varying quality. The cost to schools for the PD varies and commercial agencies set their fees. The National Teacher Training Program (NTTP), initiated by the MoE and organized by local governments and higher education institutions, is the most influential and ground-breaking nationwide PD program, and it has served over 2 million ECE teachers in less developed regions (National People’s Congress, Citation2019).

In addition to the PD opportunities offered by external providers, school-based PD remains the most accessible and common PD practice in China (Wong, Citation2012). This includes a wide range of activities, such as individual mentoring, lesson plans, peer observation, teaching demonstration competitions, and others. Many PD programs offered by external agencies such as local education bureaus either restrict quotas or give priority to teachers with a higher professional rankFootnote1 and permanent job status, which makes it difficult for the teachers who may benefit the most from PD to access it. Therefore, the MoE requires all preschools, regardless of auspices, to organize school-based PD on a regular basis (MoE, Citation2012). With the rapid expansion of ECE services in the past decade, the number of newly built preschools has surged in tandem with the number of novice teachers. If the majority of teachers in a preschool are inexperienced, school-based PD may not be sufficient to promote teachers’ professional growth, and there may indeed be a“pooling of ignorance.” Hence, it is important to have diverse providers of PD.

Extant Studies in China

In keeping with findings from studies conducted in Western contexts, extant studies have yielded inconsistent findings on the association between teachers’ PE and classroom quality in the Chinese context. Some have reported that the level of teachers’ education is unrelated to classroom process quality (Hu et al., Citation2020; Hu, Dieker, et al., Citation2016) and child development (Su et al., Citation2021a), whereas others have reported positive associations with ECE quality (Hu, Fan, et al., Citation2016) and children’s language development (Wang et al., Citation2020). One possible explanation for the inconsistent findings is related to how teachers’ levels of education are operationalized across studies. The studies that found positive associations between teachers’ education, ECE quality, and child development outcomes often categorized teacher education using a binary indicator and used a comparatively low education level as a threshold. For example, Hu, Fan, et al. (Citation2016) considered whether or not teachers had completed upper secondary school, and Wang et al. (Citation2020) categorized teachers based on whether or not they had received any postsecondary education. In contrast, studies that reported null results coded teachers’ levels of education as a continuous variable (Hu et al., Citation2020) or considered whether or not teachers had obtained associate degrees. As mentioned earlier, over 80.97% of ECE teachers had obtained associate degrees by 2018. Hence, it may be more meaningful to compare teachers with and without Associate and Bachelors degrees in ECE. Recent studies indicate that specialized training in ECE is not related to Chinese ECE quality and child development (Su et al., Citation2021a; Hu, Dieker, et al., Citation2016). Wang et al. (Citation2020) reported a negative association between PE and children’s vocabulary acquisition. They attributed their counterintuitive findings to the relatively low quality of the PE programs attended by teachers in rural areas.

Few empirical studies have examined the association between ECE teachers’ PD and child development. In their study conducted in rural China, Wang et al. (Citation2020) reported that ECE teachers’ PD was not related to children’s development. One possible reason for the result is that they only used a binary-coded variable to indicate whether teachers had attended at least one PD activity, and over 80% of the participants answered that they had, which resulted in small variations in the PD experience. Hence, measurement issues may have made it difficult to detect associations. To a certain extent, other evidence implicitly indicated that PD is positively associated with classroom quality and child outcomes. For example, studies have found that an ECE teacher’s professional rank (a composite of teaching experience, professional training, and professional competence) is positively associated with ECE quality and child development (Hu, Fan, et al., Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2020). However, to determine the specific contribution of PD to ECE quality and child development, it is necessary to have a specific indicator of PD and to avoid relying on proxy variables.

Overall, few studies have explored the associations between ECE teachers’ PD and child outcomes in the Chinese context, and they have mainly focused on PE and child outcomes. With the exception of Wang et al. (Citation2020), no recent studies have examined the association between ECE teachers’ overall PD and child outcomes. Given the Chinese government’s massive effort to improve ECE teachers’ access to PD, there is a need for more empirical evidence to document the association between PD and child development.

The Influence of Region of Residence

China has marked provincial and urban – rural disparities. Provinces in western and central regions are less developed, and regional disparities are becoming more pronounced. These disparities are evident in ECE services, especially in the quality of the ECE workforce. Recruiting well-prepared teachers in less developed regions and rural areas has long been challenging (National People’s Congress, Citation2019). In 2018, 33.87% of ECE teachers in the eastern region held Bachelor’s degrees and above, whereas fewer than 20% of ECE teachers from the central region had obtained equivalent degrees. Similarly, the number was 27.21% for urban areas and 14.25% for rural areas (MoE, Citation2019).

ECE teachers in less-developed regions are also less likely to receive in-service PD from external agencies. Outside experts were seldom engaged in rural teachers’ PD due to geographic remoteness, tight school budgets, and lack of professional networks (Hu, Fan, et al., Citation2016). It has been reported that nearly 90% of ECE teachers working in the most impoverished counties could not participate regularly in the PD activities provided by the NTTP (Zheng, Citation2014). In addition to the fewer opportunities for participation, PD activities tended to be one-off mass lectures in rural areas, which do not cater to teachers’ needs for ongoing support (Hu, Fan, et al., Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2020). It is also reported that PD topics were often repeated due to overlapping one-off programs, e.g., teacher ethics (Li et al., Citation2020). In a study conducted in rural China, Wang et al. (Citation2020) indicated that ECE teachers’ PD failed to improve children’s learning outcomes. These results raise concerns about the quality of PD in rural areas.

The variations in teacher quality and professional support give rise to disparities in classroom quality (Su et al., Citation2021a), which are associated with classroom-based and regional disparities in child development. Using data collected from five provinces across the Eastern, Middle, and Western regions of China, Zhou et al. (Citation2018) found that 3- to 6-year-olds who lived in western and rural areas performed significantly more poorly in six developmental domains than their counterparts in economically advantaged provinces.

Region of residence has a profound influence on the PE and PD of ECE teachers, classroom quality, and child development. There is some evidence supporting the compensatory hypothesis that children from less developed regions may benefit more from high-quality ECE provision than their counterparts (Su et al., Citation2021a). However, it is still not clear whether children across regions and from both urban and rural areas can benefit equally from ECE teachers’ participation in PE and PD. Little is known about whether and to what extent PE and PD can mitigate regional and urban – rural disparities in educational quality and child development outcomes.

The Present Study

This study examines associations between ECE teachers’ PE and PD experience, ECE quality, and child development across regions and urban – rural areas. Based on Desimone’s teacher PD model (Citation2009), we propose a hypothesized model to unpack the associations between ECE teachers’ PE, PD, ECE quality, and child development, as illustrated in . We examine the associations between ECE teachers’ learning experience (PE and PD) and ECE quality and child development. We also test the extent to which the region of residence moderates the associations. Two research questions are addressed: (1) Are ECE teachers’ PE and PD associated with ECE quality and child development? (2) Does the area of residence (urban vs. rural) moderate the associations between ECE teachers’ PE, PD, ECE quality, and child development?

Figure 1. Hypothesized theory of change model based on Desimone’s (Citation2009).

Guided by previous research and the Chinese context, we made the following predictions: (1a) ECE teachers’ PE and PD would be associated with ECE quality; (1b) ECE teachers’ PD, but not PE, would be directly associated with child development; (1c) ECE teachers’ PD was indirectly associated with child development through ECE quality; and (2) The associations between ECE teachers’ PE and PD and ECE quality and child development were stronger for ECE quality and child development in less developed regions and rural areas than more developed, urban areas.

Method

Research Sites and Participants

This study was part of a larger project conducted in two distinct provincial-level administrative regions of China: Shanghai municipality in Eastern Coastal China and Guizhou province in Southwest China. The two regions differ substantially in terms of their socioeconomic development and education. The annual GDP per capita of Shanghai was three times more than Guizhou (National Bureau of Statistics of China [NBS], Citation2019). As one of the most underdeveloped and mountainous provinces of China, 54% of Guizhou’s population lives in rural areas, whereas 88% of Shanghai’s population resides in urban areas (NBS, Citation2019). In general, distinct socioeconomic differences can be observed across the two regions.

To ensure the representativeness of the participating preschools, they were selected based on the region of residence (urban vs. rural; downtown vs. suburban), auspices (public vs. private), and the local government’s rating of preschool quality. In Guizhou, two urban preschools and two rural preschools in each region were invited to participate, resulting in 16 preschools from four regions of the province. In Shanghai, 13 preschools were randomly selected from four downtown and six suburban districts. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China [NBS] (Citation2021), Shanghai is a highly developed municipality, and its suburban districts are also considered urban areas. There is less variation across its districts than across the regions in Guizhou province. Therefore, in the analysis, we did not distinguish between urban and suburban areas in Shanghai.

Twenty-nine preschools (6 privately funded and 23 publicly funded), representing the range of typical preschools in the local districts and regions, participated in this study. The participating preschools provided full-day ECE programs for children aged 3 to 6. Preschools in China typically have three levels of age-segregated classes, with classes for 3-year-olds (K1), 4-year-olds (K2), and 5-year-olds (K3). We intentionally targeted K2 children as their class teachers had worked with them for at least one year. Furthermore, the daily schedule of K2 children would not be influenced by K3 teachers focusing on preparing children for the transition from preschool to primary school, a common K3 practice in China. Our sample included one to six K2 classes in each preschool, except for three rural preschools which had mixed-age classes. The small number of children enrolled in these three preschools made it impractical to have age-segregated classes.

Initially, we planned to randomly recruit 10 boys and 10 girls from one K2 class in each preschool because an adequate sample size (e.g., 50 clusters with 20 units) is needed to obtain unbiased parameter estimates (Kreft, Citation1996). However, some rural preschools had fewer than 20 children in a single K2 class, and a few only offered mixed-age programs. Furthermore, many principals expressed concerns about fairness and felt that parents would ask why only one K2 class was chosen. Hence, we adjusted the sampling plan to address the principals’ concerns. In general, 10 boys and 10 girls were randomly selected from one to three K2 or mixed-age classes in each preschool in Guizhou; 10 boys and 10 girls were randomly selected from two K2 classes in each preschool in Shanghai. Ultimately, 706 children (Mage = 57.68, SD = 4.78) with 52 classroom teachers at 29 preschools from 18 different districts of Shanghai and Guizhou province participated in this study. The children in Shanghai were significantly older and came from families with higher levels of parental education and occupational status (ps < .001). Detailed information on child and family background is presented in .

Table 1. Children and family characteristics.

Class sizes ranged from 19 to 49, with an average teacher – child ratio of 1:12.01 in Shanghai, 1:21.04 in urban Guizhou, and 1:18.31 in rural Guizhou. All observed classroom teachers were female with 1 to 30 years of teaching experience (Myears = 8.67, SD = 6.46). Almost all observed teachers (98%) held certificates for teaching in preschools. Less than a third of the observed teachers (30.77%) held a Bachelor’s degree, and 75% had majored in ECE. Compared to Guizhou, the teachers in Shanghai were significantly older, more experienced, and more likely to have tenured positions as well as higher professional ranks. They also had smaller class sizes and more favorable teacher – child ratios than other teachers (ps < .05). Information on teacher and classroom characteristics is presented in .

Table 2. Observed teacher and classroom characteristics.

Measures

Classroom Teachers’ PE and PD Experience

The teachers completed a survey on their PE and PD experience. The questionnaire was developed by Rao & Lau (Citation2016) to align with the survey themes planned for UNESCO’s Survey of Teachers in Pre-Primary Education (STEPP) in LMICs. The questionnaire was translated, adapted, and has already been used in China (Yang & Rao, Citation2021).

PE. Unlike previous studies, which have primarily used teachers’ highest educational attainment as the indicator of PE (Hu, Dieker, et al., Citation2016; Lin & Magnuson, Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2020), we used teachers’ initial education level, prior to entering the profession, to reflect their full-time educational preparation experience. We did not use the highest level of education as teachers may have upgraded their qualifications through online certification courses and part-time credential programs, which are not always recognized by the State. Notably, a significant number of preschool teachers in China acquire additional qualifications through this means. The information about classroom teachers’ PE, including initial education level (1 = bachelor’s degree and above, 0 = no bachelor’s degree) and specialization in ECE (1 = yes, 0 = no), was dummy coded.

PD. Guided by the “Who, How, and What” framework of the NPDCI (Citation2008), we measured ECE teachers’ PD in terms of its frequency and diversity in the past year: Frequency of school-based PD (How), Frequency of externally offered PD (How), Diversity of content (What), and Diversity of providers (Who). The respondents were asked to report how often they had participated in externally organized PD activities (e.g., visiting and observing in other preschools and attending workshops or conferences) and school-based PD activities (e.g., peer observation and school-based seminars) in the past year. These were reported on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 2 = once or twice a year, 3 = several times a year, 4 = once a month, 5 = more than once a month). In addition to the frequency of PD, we asked the respondents to report on the diversity of PD providers (e.g., government education departments, universities, and commercial organizations) because different PD providers bring unique expertise and perspectives. For example, the PD provided by government officials may focus on aligning the curriculum with national guidelines and policies, while teacher training institutes may emphasize pedagogical content knowledge. In contrast, PD offered by commercial entities may focus on how to best use their products to promote learning. Hence, the experience of teachers who have participated in PD activities provided by different external organizations may differ considerably. Teachers were also asked to report on the diversity of PD contents (e.g., child development, child abuse, maltreatment, family, and community engagement) over the past year. The high score indicates multiple providers provided the PD and covered diverse topics. Cronbach’s alpha of the 22 items related to PD experience was 0.82, indicating good internal consistency.

ECE Quality

Measuring ECE quality has long been a challenge in LMICs. Most well-established ECE quality measurements have been developed to reflect a Euro-American view on quality ECE, which lacks contextual appropriateness and cultural responsiveness for LMICs (Raikes et al., Citation2020). This study adopted the Measure of Early Learning Environments scale (MELE; Raikes et al., Citation2020), a classroom observation tool designed for use specifically in LMICs, to assess ECE quality. The MELE is composed of four domains: Learning Activities (9 items), Classroom Interactions and Approaches to Learning (11 items), Classroom Arrangement, Space and Materials (13 items), and Facilities and Safety (6 items). The first domain evaluates teacher support and guidance during math, literacy and language, science, motor, and art activities. The second domain focuses on teachers’ classroom management, group and individual interaction strategies, and children’s engagement. The third domain assesses the degree to which learning materials (e.g., books and materials for socio-dramatic play) are available and utilized. The last domain evaluates safety and hygiene conditions and practices.

The original MELE tool was translated from English into Chinese and back-translated to ensure the equivalence of the English and Chinese versions. A few items were modified to ensure that all items were appropriate to the Chinese cultural context. To be specific, (a) the definition of item 11, the development of literacy to the development of emergent literacy and pre-writing skills, was extended to reflect the current practices of Chinese literacy learning in preschools; (b) one item about promoting science exploration ability was added because it was addressed by the MoE; and (c) the original item 29 Diversity “respect for different ethnic, religious groups” was changed to “respect for people from different ethnic and religious groups, and those with special needs,” given that most children were from the Han Chinese ethnic group. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87 for the MELE and ranged from 0.66 to 0.76 for the subscales. The correlation between the total scale and subscales was high (rs = 0.73–0.84, p < .01) and relatively high among the subscales (rs = 0.42–0.63, p < .01). To ensure the concurrent validity of the MELE, we examined the association between it and the established tool Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale-Extension (ECERS-E; Sylva et al., Citation2010). The regression results suggested that the total MELE score explained 69% of the variance in the ECERS-E (R2 = 0.69, F (1, 50) = 109.33, p < .001), indicating strong concurrent validity of the MELE.

Child Development

The East Asia – Pacific Early Child Development Scales (Short Form) EAP-ECDS (SF) was used to measure child development. The EAP-ECDS are a direct assessment tool for evaluating the development of children aged 3 to 5 (Rao et al., Citation2019). The EAP-ECDS is a psychometrically robust, well-established, and culturally appropriate measure that has been used and validated in seven countries in East Asia and the Pacific, including China (Rao et al., Citation2019). The Short Form has also been validated.

Seven domains of learning were assessed using the EAP-ECDS: Cognitive Development (8 items, α = 0.91), Language and Emergent Literacy (6 items, α = 0.83), Socio-Emotional Development (6 items, α = 0.81), Motor Development (4 items, α = 0.50), Health, Hygiene, and Safety (4 items, α = 0.69), Cultural Knowledge and Participation (4 items, α = 0.72), and Approaches to Learning (6 items, α = 0.82). Each item was binary coded (1 = successful completion, 0 = unsuccessful completion). We focused on Cognitive Development (CGD), Language and Emergent Literacy (LEL), Socio-emotional Development (SED), and Approaches to Learning (ATL).

Covariates

Children’s characteristics

Children’s age was measured in months, and gender was dummy coded (1 = boy, 0 = girl).

Family socioeconomic status (SES). Information about children’s family SES was collected through a parent-reported questionnaire. Family SES was composed of four variables: fathers’ and mothers’ highest educational attainment and their occupations. Parents’ educational attainment was coded into eight categories from 1 = no formal education to 8 = postgraduate and above. Parents’ occupations were categorized into five levels from 1 = non/semi-skilled workers to 5 = highly specialized personnel and senior administrators. The four variables were standardized as z-scores, and the average of the standardized scores was calculated as the index of family SES (Cohen et al., Citation2006).

Program and classroom covariates. A set of program and classroom covariates that may be associated with ECE quality and child development were controlled for in the analyses: preschool auspices (1 = publicly-funded, 0 = privately-funded), preschool hours, preschool size, class size, teacher-to-child ratio, class teachers’ teaching experience, permanent job status (1 = permanent teacher, 0 = nonpermanent teacher), and professional rank (1 = having a professional rank, 0 = no professional rank).

Areas of residence. The regions of residence were coded as 1 = Shanghai, 2 = urban Guizhou, and 3 = rural Guizhou.

Procedure

Data were collected from November 2017 to June 2018. The same group of assessors conducted the classroom observations and child assessments in Shanghai and Guizhou. Written consent was obtained from the principals of the participating preschools, teachers, and parents. The teacher questionnaires were distributed directly to the observed teachers and took around 20 minutes to complete. The information about family SES was provided by the parents through – in most circumstances – parent questionnaires. At least one parent (father/mother) on behalf of their spouse, responded to questions related to family SES. In rural Guizhou, some parents (or grandparents as the primary caregivers) had relatively lower levels of formal education and had difficulty filling out the questionnaire independently. Thus, structured individual interviews were conducted to collect the relevant information.

Before the classroom observation, all assessors attended a 2-day training course. The first day focused on introducing the theoretical framework, structure, content, and scoring of the MELE. Following the introductory workshop, there was a half-day in-class observation training followed by a discussion. Any discrepancies in scoring were discussed to reach a consensus. After the 2-day training session, all assessors and the designated gold standard (an expert in the scale) conducted a 2 h observation in a real-life setting. An inter-rater agreement of over 90% (a scoring difference within 1 point was considered acceptable) between the assessor and gold standard was necessary for the assessor to conduct classroom observations of quality independently. During data collection, each assessor was paired with the gold standard to observe the same classroom, and a 90% inter-rater reliability score was achieved. Each whole-day observation took around 5 hours, excluding the children’s naptime. On the day the observation took place, 88% of the lead teachers managed the class and thus were observed, and the rest were managed by assistant teachers.

All EAP-ECDS (SF) assessors also received 3 days of training from an expert in administering individual assessments. Assessors had to reach an inter-rater reliability rate of at least 85% at the item level with the trainer prior to formal data collection. The reliability rate between the assessors and the trainer was reassessed every 20 to 30 administrations of the tool. Inter-rater reliability exceeded 90% at the item level at these reliability checks. Each individual assessment took around 20 to 30 minutes; the administration time varied depending on the children’s ability, mood, and rapport with the administrators.

Analytical Strategies

Missing Data

Before data analysis, the missing values were handled using the Multiple Imputation with Chained Equations (MICE) technique. Complete information on the variables of interest was available for 78.61% of the observations (N = 706). Data were missing for child-level attributes (0.28%–1.98%), family-related covariates (7.93%-8.83%), and classroom-level attributes (1.98%–4.23%). The overall missingness tended to be associated with living in a less developed region, larger school and class sizes, and higher teacher – child ratios. Twenty datasets were generated, and the pooled results are reported. The pooled results are similar to the original data using the listwise deletion method.

HLM Approaches

Due to the nested structure of the data, with 706 children nested in 52 classrooms and 18 distinct districts, children from the same classes and districts were possibly more homogenous. Therefore, hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was adopted to examine the relationships among PE, PD, ECE quality, and child development. We estimated models with random intercepts at the classroom (Level 2, N = 52) and district (Level 3, N = 706) levels, with all predictors at the child and classroom levels included. Multilevel mediation models were constructed to examine whether PE and PD exhibited an influence on child development through ECE quality. Furthermore, to unpack whether such association varied across residence, we conducted a moderation analysis by adding interaction terms between each predictor and the region of residence (e.g., teachers’ initial education level urbanicity) in the HLMs. All continuous predictors were centered at the grand mean, and categorical variables were dummy-coded for ease of interpretation and to avoid collinearity. The standardized coefficients were reported. All multilevel analyses were conducted using Stata 15 software and used cluster-robust standard errors to guard against the dependency of standard errors.

Covariates Selection

Child development differences are co-constructed and influenced by individual characteristics, family, school, and the broader societal environment. A series of child-, family-, and classroom-level covariates were initially selected based on the literature (e.g., children’s age, gender, and family SES; the structural classroom features of class size; the teacher – child ratio; and teachers’ teaching experience and professional rank).

To simplify the model and reduce redundancy, we constructed a separate set of HLMs to examine the relationship between each covariate and classroom quality. The covariates that were significantly associated with the total MELE score were included in the ECE quality model, namely regions of residence, class size, the teacher – child ratio, and teachers’ professional rank. Similarly, the covariates that were significantly associated with child development were included in the child development model, including regions of residence and children’s age, family SES background, and school hours.

Results

Descriptive Information

Raw scores for child, family, teacher, and classroom variables are presented in and . Preliminary analysis suggested that the children from Shanghai performed significantly better in all four domains of development than children in urban and rural Guizhou (ps < .001). Children in urban Guizhou performed better than children in rural Guizhou. The total MELE score and subdomain scores also indicated similar regional variations in ECE quality. The classrooms in Shanghai scored significantly higher on the MELE and its four subdomains than those in urban and rural Guizhou (ps < .001). Within Guizhou, urban Guizhou had a significantly higher score on the MELE and its subdomains, except for the subdomain of Classroom Interaction.

In general, zero-order correlations indicated that PE and PD experience were both significantly associated with ECE quality and child development, but they were more strongly related to the proximal outcome of ECE quality and relatively less related to the distal outcomes of child development. Having a bachelor’s degree was positively associated with ECE quality (rs = 0.29–0.37, p < .001) and child development outcomes (rs = 0.07–0.20, p < .05). Specialization in ECE was modestly correlated with some aspects of ECE quality (rs = 0.09–0.11, p < .05) but not associated with any aspects of child development outcomes. The frequency of externally provided and school-based PD was moderately correlated with the MELE (rs = 0.29–0.54, p < .001) and most domains of child development outcomes (rs = 0.13–0.48, p < .001). The diversity of PD providers and PD contents was positively correlated to most domains of the MELE (rs = 0.09–0.30, p < .05) and some domains of child development. Details are provided in .

Table 3. Correlation matrix of PD, ECE quality, and child development.

PE, PD, and ECE Quality Across Regions

presents the unique contribution of ECE teachers’ PE and PD experience to ECE quality after controlling for other classroom covariates and urbanicity in the two-level model (Model 1). The Model 1 results indicate that ECE quality in urban Guizhou (β = −1.4, p < .001) and rural Guizhou (β = −1.07, p < .001) were significantly lower than in Shanghai. Urbanicity was the strongest predictor of ECE quality. After controlling for other covariates, ECE teachers’ PD, measured by Frequency of school-based PD (β = .32, p < .01) and Diversity of PD providers (β = .28, p < .001), was significantly associated with the total MELE score with medium effect sizes. Unexpectedly, ECE teachers’ PE measured by Bachelor’s degree and specialized training in ECE and PD measured by Frequency of externally-offered PD and Diversity of PD content were not associated with the total MELE score (ps > .05). Meanwhile, having a title denoting a professional rank for teachers (β = .34, p < .05) and class size (β = .07, p < .001) were positively associated with the total MELE score, whereas the teacher – child ratio (β = −.05, p < .05) was negatively associated with the total MELE score.

Table 4. Model 1: Association between PE, PD and ECE quality.

PE, PD, and Child Development Across Regions

Examining the Associations Between PE, PD and Child Development

Similarly, a three-level model (Model 2) was constructed to examine the relations among PE, PD, and child development, as shown in . The results of Model 2 suggest that region of residence remained the strongest predictor of child development. Children living in urban Guizhou (β = −.69, p < .001) and rural Guizhou (β = −.81, p < .001) performed significantly worse than those in Shanghai on the EAP-ECDS assessment. However, there was no evidence that ECE teachers’ PE and PD were directly associated with child development using the EAP-ECDS after controlling for other covariates.

Table 5. Model 2: Associations between PE, PD, and child development outcomes.

Examining the Associations Between PE, PD and Child Development Through ECE Quality

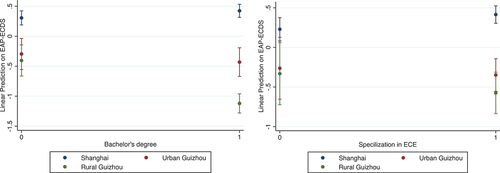

Although PE and PD were not directly associated with child development, there was a possibility that they would be indirectly associated with child development through classroom quality, as we hypothesized based on the Theory of Change model. We adopted a multilevel mediation method to test this hypothesis with all child- and classroom-level covariates included. The results indicate that PE, measured by initial educational level and specialization in ECE, was not indirectly associated with child development. Only teachers’ PD measured by Frequency of school-based PD and Diversity of PD providers was significantly and indirectly associated with child development. As shown in , the direct Path a from Frequency of school-based PD to child development was not significant (β = 0, p > .05), whereas Path b (β = .32, p < .001) and Path c (β = .29, p < .001) were both significant, indicating that despite Frequency of school-based PD not being directly associated with child development, it was modestly and indirectly associated with child development through the ECE quality (β = .10, p < .01). A similar indirect association between Diversity of PD providers and child development (β = .05, p < .05) through the ECE quality was found, as presented in .

Moderation of Residence

The Influence of PE Across Residence

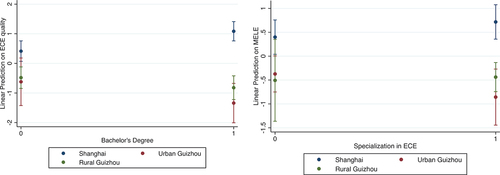

The findings from the moderation analysis suggest that the influence of teachers’ PE varied significantly across area of residence. Specifically, having a bachelors’ degree was significantly associated with a higher ECE quality (β = .67, p < .001) and better child development (β = .12, p < .01) in Shanghai but this was not the case in urban and rural Guizhou. Similarly, teachers’ specialization in ECE was associated with a higher ECE quality (β = .31, p < .05) and better child development (β = .19, p < .01) only for teachers in Shanghai. and illustrate the adjusted means of classroom quality and child development across residence.

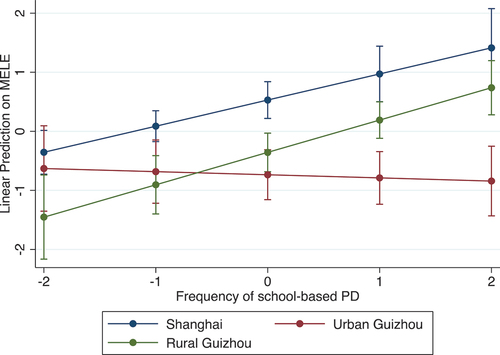

The Influence of PD Across Residence

We then tested the extent to which the influence of PD varied by place of residence. The results indicate that Frequency of school-based PD was not significantly associated with ECE quality for urban Guizhou teachers (β = −.05, p > .05), but it was significantly associated with ECE quality in Shanghai (β = .44, p < .001) and rural Guizhou (β = .55, p < .001). The marginal effect is presented in . No evidence indicated that the influence of Frequency of externally offered PD, Diversity of providers, and Diversity of content differed across residences. In general, PD was associated with ECE quality and child development regardless of region and residence.

Supplementary Analysis

To obtain a more nuanced understanding of associations between ECE teachers’ PE, PD experience, ECE quality, and child development, we examined the associations between PE and PD and each domain of ECE quality and child development. Specifically, having a bachelor’s degree was significantly related to Classroom Interaction (β = .57, p < .001); Frequency of school-based PD was moderately associated with Learning Activities (β = .25, p < .05), Classroom Interaction (β = .37, p < .05), and Classroom Facilities and Safety (β = .53, p < .001); Diversity of PD providers was a strong predictor of Classroom Interaction (β = .30, p < .001), Classroom Arrangement (β = .26, p < .05), and Classroom Facilities and Safety (β = .21, p < .01). These significant associations indicate that ECE teachers’ PD is associated with specific subdomains of ECE quality, and that classroom interaction is significantly associated with both PE and PD experience. However, ECE teachers’ PE and PD are not directly related to any subdomains of child development measured by the EAP-ECDS. More details are documented in .

Table 6. Association between PE, PD and different domains of child development.

Discussion

This study examined the role of ECE teachers’ PE and PD experience in predicting ECE quality and child development and whether such associations varied across regions of China. We build on earlier research by measuring the diversity and frequency of ECE teachers’ PD experience in more detail than in previous studies. Prior research (Hu et al., Citation2020; Hu, Dieker, et al., Citation2016; Hu, Fan, et al., Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2020) has focused more on Chinese ECE teachers’ PE than on teachers’ PD. Meanwhile, we explored the applicability of Desimone’s (Citation2009) Theory of Change model of teacher development. We considered whether a teacher’s professional learning is associated with ECE quality and whether ECE quality is associated with child development. In general, ECE teachers’ PE measured by initial education level was associated with one specific domain of ECE quality: Classroom Interaction. ECE teachers’ PD was moderately associated with ECE quality as measured by the MELE and was not directly associated with child development as measured by the EAP-ECDS. The results also indicate that PD was indirectly associated with child development through ECE quality. Region of residence moderated the influence of PE and PD.

Role of ECE Teachers’ PE and PD on ECE Quality

Consistent with findings from previous intervention studies and reviews conducted both in high-income countries (Egert et al., Citation2018; Markussen-Brown et al., Citation2017) and LMICs (Yoshikawa et al., Citation2015), ECE teachers’ PD was moderately associated with ECE quality in this study. The magnitude of the association between ECE teachers’ PD and ECE quality across subdomains is promising. Specifically, an increase of one standard deviation (SD) in ECE teachers’ participation in school-based PD led to a 0.32-SD increase in the total MELE score. This finding adds quantitative evidence to previous qualitative studies in Chinese secondary school settings showing that school-based PD can improve classroom teaching quality (Wong, Citation2012). Similarly, one SD increase in the diversity of PD providers brought about a 0.28-SD increase in the total MELE score, consistent with the conclusion of one of the largest synthesis studies (Guskey & Yoon, Citation2009). Yet, the frequency of externally offered PD was not associated with the total MELE score. The seemingly contradictory findings further indicate the importance of involving multiple external experts for effective PD activities (Guskey & Yoon, Citation2009). Beyond the frequency of externally offered PD, engaging multiple external experts can bring unique skills and expertise and complement each other. Preschools should organize school-based PD activities regularly to provide ECE teachers with timely and contextualized support that taps into their daily practice.

Furthermore, local educational bureaus and higher education institutions should work closely with preschools to involve external experts in PD. For example, external experts can regularly join group meetings, acting as facilitators to help teachers by questioning, connecting, and expanding ideas, as well as by providing professional resources. The diversity of PD content was not found to be associated with ECE quality. As previous research has shown, an effective PD program should be both focused and specific because too many foci could prevent in-depth learning (Desimone, Citation2009). A PD program that covers a range of topics, such as teacher content knowledge, child-centered beliefs, and teacher – child interaction strategies, may risk teachers getting lost in the excessive content, reducing the overall effect of the PD program itself.

Existing research yields mixed findings about the association between ECE teachers’ education level and overall ECE quality (Early et al., Citation2007; Lin & Magnuson, Citation2018; Manning et al., Citation2019). We found that ECE teachers’ education level was associated with one specific subdomain of ECE quality measured by the MELE, Classroom Interaction, which has been shown to be pivotal for child development. This substantial association might have been detected because we used teachers’ initial education level, not their highest education level, reflecting teachers’ full-time preparation experience. Similar to studies conducted in the Chinese and other contexts (Su et al., Citation2021a; Hu, Dieker, et al., Citation2016; Lin & Magnuson, Citation2018), there seems to be a lack of association between specialized training in ECE and ECE quality. The lack of association suggests that ECE teacher preparation programs may need to better prepare teachers so they may provide high-quality ECE.

The finding of few associations between ECE teachers’ PE and ECE quality does not justify lowering job entrance requirements. On the one hand, ECE teachers’ initial education level substantially impacted classroom interaction, indicating potential benefits for children’s development. On the other hand, requiring a degree with specialized training professionalizes the ECE workforce. It brings with it more career advancement opportunities, which in turn ensures ECE teachers’ wages are comparable to those of primary school teachers (Yang & Rao, Citation2023). Consequently, the adequate remuneration of ECE teachers can improve child development. Considering cost-effectiveness, it is not feasible to improve the quality of the ECE workforce by depending entirely on teacher preparation programs, especially in LMICs (Rao et al., Citation2022; Neuman et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, the complexity of teaching requires ongoing professional support in addition to the pre-service preparation. Therefore, we argue that a combination of PE and PD is needed to improve the ECE workforce and ECE quality.

Indirect Association with Child Development

Consistent with previous findings (Su et al., Citation2021a; Piasta et al., Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2020; Yoshikawa et al., Citation2015), ECE teachers’ PE and PD experiences were not directly associated with child development after controlling for residence and other classroom and child characteristics. However, the diversity and frequency of ECE teachers’ PD were indirectly associated with child development through ECE quality. A similar indirect association has also been reported in science learning intervention studies (Gropen et al., Citation2017; Piasta et al., Citation2015). This finding adds empirical evidence to support Desimone’s (Citation2009) Theory of Change model in ECE settings. This holds that effective teacher learning has an effect on ECE quality, which, in turn, influences child development. This finding also indicates that classroom quality may be the conduit that transfers PD into desired child outcomes. Thus, to improve ECE quality, PD activities must focus on assisting teachers to improve their pedagogical quality.

Moderating Effect of Residence

ECE teachers’ PE and PD did not generally benefit ECE quality and child development more in less developed regions than in developed regions, such as Shanghai. Our finding does not support the compensatory hypothesis, which suggests that (quality) ECE interventions will have a larger positive effect on children from economically disadvantaged families than their more advantaged peers. In contrast, teachers’ PE as measured by initial education level and specialization in ECE was positively associated with ECE quality and child development in Shanghai but not in urban and rural Guizhou. Previous studies conducted in rural China have also found teachers’ PE not to be associated with classroom quality and child development (Hu et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2020). The gap in the quality of teacher preparation programs across regions may explain the stronger positive influence of PE in Shanghai than in Guizhou. As in other countries (Sutcher et al., Citation2019), renowned teacher preparation programs in China are primarily located in developed regions. According to the MoE (Citation2021), only one ECE teacher training program is rated good quality in Guizhou province. Unlike Shanghai, which can attract qualified teacher candidates from across the country, less developed provinces, such as Guizhou, rely more on local teacher preparation programs. Again, we echo our previous discussion that there is an increasing need to ensure the quality of teacher preparation programs in China.

Compared to PE, ECE teachers’ PD was not generally moderated by region of residence. PD, as measured by diversity, benefited classroom quality across regions. This supports the notion that regardless of where ECE teachers work, in general, more access to PD offered by diverse providers can benefit teachers’ practice equally. The association between the Frequency of school-based PD and ECE quality was weaker for the urban Guizhou teachers than for other teachers. A plausible interpretation could be that there are variations in the quality of school-based PD across regions, which was not captured in the study. ECE teachers from more developed regions tend to receive high-quality PD that taps into their practice (Hu, Fan, et al., Citation2016). Thus, school-based PD in Shanghai may be of higher quality in influencing teachers’ practices than in urban Guizhou. Compared to teachers in urban Guizhou teachers in rural Guizhou ECE teachers generally received less PE but similar amounts of PD activities. PD may have had a stronger influence in rural Guizhou than urban Guizhou because smaller class sizes and better teacher-to-child ratios may have made it easier for rural teachers to implement their learnings than teachers in urban Guizhou. Therefore, to eliminate the ECE quality gap, ensuring that all ECE teachers across all regions have equal access to high-quality PD and that teacher to child ratios are favorable is paramount. To meet the challenge of limited funding, the priorities may have to shift to support ECE teachers in less developed regions and rural areas.

Limitations and Future Directions

Some caveats need to be acknowledged in interpreting the findings. First, this study was cross-sectional and precludes causal inference. Children’s baseline developmental scores and prior ECE quality were not measured and controlled for. It is sensible to conduct mediation analysis with cross-sectional data if the temporal order among the constructs is logical (Fairchild & McDaniel, Citation2017). For example, we used the teachers’ retrospective reports of their PE and PD experience in the past year, which occurred before the other two constructs: our classroom observation (the MELE) and child assessments. However, a longitudinal study design is more appropriate to test this hypothesis. At the same time, teacher reports may reflect a social desirability bias, and retrospective reports may be inaccurate because they rely on memory, which may not be exact (Downer et al., Citation2009). Future studies should address this limitation by implementing a longitudinal study design or an experimentally designed intervention to clarify causality.

We did not focus on a specific PE or PD intervention program, which is generally the focus of research (Koellner & Jacobs, Citation2015) that favors more robust statistical inference (e.g., causal inference). We intentionally shifted attention to ECE teachers’ whole professional learning experience. Studies that report the effectiveness of PD have generally been designed and rigorously controlled by researchers, but such interventions are not always accessible to the majority of ECE teachers (Powell et al., Citation2010). In fact, most Chinese ECE teachers have experienced PD either through school-based PD activities or seminars offered by local educational bureaus. These PD activities integrate ECE teachers’ overall PD experience and influence ECE quality and child development. That stated we recognize the importance and necessity of rigorously designed and implemented PD intervention programs.

We should acknowledge issues with the measurement of key variables. The lack of a direct effect on child development may be a function of measurement issues. In this study, we measured teachers’ PE considering completed degrees and college majors, and measured PD from aspects of frequency and diversity. However, we did not measure the quality of PE and PD. Therefore, it is possible for a given teacher to attend a large number of PD activities but also for the quality of these activities to be insufficient to have a direct influence on child development. Future research should develop more comprehensive definitions and measures to capture the multi-dimensional and specific practices of teachers’ PE and PD, especially quality. For example, Lin and Magnuson (Citation2018) used indicators of completed degrees, numbers of ECE-related credits, and position on the professional ladder to reflect teachers’ PE.

In addition, like many child assessment tools, the EAP-ECDS focuses more on children’s constrained skills. Examples are counting, naming shapes, and writing names, which can be taught through direct instruction and rote practices. However, children’s higher-order cognitive ability, which is generally acquired through scaffolded interactions, is not measured. Examples include self-regulation, problem-solving, and critical thinking (Burchinal, Citation2018). Suppose measures only focus on children’s unconstrained skills. In that case, they cannot reflect the contemporary emphasis on child-centered and play-based pedagogy and the disdain for didactic teaching in current teacher preparation and professional training (MoE, Citation2012). Thus, a disconnect may exist between measured PE and PD practice and child development. Moreover, the mechanism of how teachers’ learning brings about changes in the teachers themselves and in child development remains unclear. It requires more in-depth discussion through case studies and ethnographic observations.

Conclusions

It is widely accepted that a professionally trained ECE workforce can provide high-quality ECE and promote children’s development. The complexity of teaching in the early years requires ECE teachers to be professionally supported throughout their careers. Like many other countries, China has endeavored to improve the quality of the ECE workforce by establishing professional standards, initiating teacher preparation programs, and providing continuing PD opportunities. However, little is known about whether such efforts are effective in improving ECE quality and child development. This is one of the few empirical studies that have examined the associations between ECE teachers’ PE, PD, ECE quality, and child development across different regions of China. The findings of this study provide evidence that across regions, ECE teachers’ overall PD experience generally contributes to ECE quality and child development. Besides, ECE teachers’ initial education level is closely related to teacher – child interaction, the strongest predictor of child development. Region of residence moderates the influence of PE greatly. These findings call for more policy and research attention to the quality of ECE teacher preparation and professional support.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Professional rank: Teachers are given a professional rank to denote their level of seniority. A teacher’s professional rank reflects teaching experience, professional training, professional competence, and pedagogical expertise. The Local Education Authority of the government determines the professional rank. A teacher’s professional rank is a matter of great significance as the rank determines teachers’ salaries, welfare benefits, and eligibility for PD experiences.

References

- Brunsek, A., Perlman, M., McMullen, E., Falenchuk, O., Fletcher, B., Nocita, G., Kamkar, N., & Shah, P. S. (2020). A meta-analysis and systematic review of the associations between professional development of early childhood educators and children’s outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 217–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.03.003

- Burchinal, M. (2018). Measuring early care and education quality. Child Development Perspectives, 12(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12260

- Cohen, S., Doyle, W. J., & Baum, A. (2006). Socioeconomic status is associated with stress hormones. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68(3), 414–420. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000221236.37158.b9

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140

- Downer, J. T., Kraft-Sayre, M. E., & Pianta, R. C. (2009). Ongoing, web-mediated professional development focused on teacher–child interactions: Early childhood educators’ usage rates and self-reported satisfaction. Early Education and Development, 20(2), 321–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280802595425

- Early, D. M., Maxwell, K. L., Burchinal, M., Alva, S., Bender, R. H., Bryant, D., Cai, K., Clifford, R. M., Ebanks, C., Griffin, J. A., Henry, G. T., Howes, C., Iriondo‐Perez, J., Jeon, H., Mashburn, A. J., Peisner‐Feinberg, E., Pianta, R. C., Vandergrift, N., & Zill, N. (2007). Teachers’ education, classroom quality, and young children’s academic skills: Results from seven studies of preschool programs. Child Development, 78(2), 558–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01014.x

- Egert, F., Fukkink, R. G., & Eckhardt, A. G. (2018). Impact of in-service professional development programs for early childhood teachers on quality ratings and child outcomes: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 88(3), 401–433. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317751918

- Fairchild, A. J., & McDaniel, H. L. (2017). Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: Mediation analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 105(6), 1259–1271. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.117.152546

- Gerde, H. K., & Powell, D. R. (2009). Teacher education, book-reading practices, and children’s language growth across one year of head start. Early Education and Development, 20(2), 211–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280802595417

- Gropen, J., Kook, J. F., Hoisington, C., & Clark-Chiarelli, N. (2017). Foundations of science literacy: Efficacy of a preschool professional development program in science on classroom instruction, teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge, and children’s observations and predictions. Early Education and Development, 28(5), 607–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2017.1279527

- Guskey, T. R., & Yoon, K. S. (2009). What works in professional development? Phi Delta Kappan, 90(7), 495–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170909000709

- Hu, B. Y., Dieker, L., Yang, Y., & Yang, N. (2016). The quality of classroom experiences in Chinese kindergarten classrooms across settings and learning activities: Implications for teacher preparation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 57, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.03.001

- Hu, B. Y., Fan, X., Locasale-Crouch, J., Chen, L., & Yang, N. (2016). Profiles of teacher-child interactions in Chinese kindergarten classrooms and the associated teacher and program features. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 37, 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.04.002

- Hu, B. Y., Wang, S., Song, Y., & Roberts, S. K. (2020). Profiles of provision for learning in preschool classrooms in rural China: Associated quality of teacher-child interactions and teacher characteristics. Early Education and Development, 33(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2020.1802567

- Koellner, K., & Jacobs, J. (2015). Distinguishing models of professional development: The case of an adaptive model’s impact on teachers’ knowledge, instruction, and student achievement. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114549599

- Kreft, I. G. G. (1996). Are Multilevel Techniques Necessary? An Overview, Including Simulation Studies [ Unpublished Manuscript]. California State University.

- Li, J., Xu, Z., & Xue, E. (2020). The problems, needs and strategies of rural teacher development at deep poverty areas in China: Rural schooling stakeholder perspectives. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101496

- Lin, Y.-C., & Magnuson, K. A. (2018). Classroom quality and children’s academic skills in child care centers: Understanding the role of teacher qualifications. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 42(1), 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.10.003

- Manning, M., Wong, G. T. W., Fleming, C. M., & Garvis, S. (2019). Is teacher qualification associated with the quality of the early childhood education and care environment? A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 89(3), 370–415. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319837540

- Markussen-Brown, J., Juhl, C. B., Piasta, S. B., Bleses, D., Højen, A., & Justice, L. M. (2017). The effects of language- and literacy-focused professional development on early educators and children: A best-evidence meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38(1), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.07.002

- Ministry of Education. (2012). Opinions on deepening the reform of teacher education (in Chinese). http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A10/s7011/201211/t20121108_145544.html

- Ministry of Education. (2019). Educational statistics year book of 2018. http://www.moe.gov.cn/s78/A03/moe_560/jytjsj_2017/qg/201808/t20180808_344728.html

- Ministry of Education. (2021). Circular on the list of teacher preparation programs that have passed the quality standards in 2021 (in Chinese). http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A10/s7011/202110/t20211021_574101.html

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2019). China statistical year book 2018 (in Chinese). http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2018/indexch.htm

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2021). Announcement on the update of national statistical district codes and urban and rural division codes. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjbz/tjyqhdmhcxhfdm/2021/index.html

- National People’s Congress. (2019). Report of early childhood education development and reform (in Chinese). http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c30834/201908/1c9ebb56d55e43cab6e5ba08d0c3b28c.shtml

- National Professional Development Center on Inclusion. (2008). What do we mean by PD in the early childhood field?. The University of North Carolina, FPG Child Development Institute.

- Neuman, M. J., Josephson, K., & Chua, P. G. (2015). A review of the literature: Early childhood care and education (ECCE) personnel in low-and middle-income countries. UNESCO.

- Piasta, S. B., Logan, J. A. R., Pelatti, C. Y., Capps, J. L., & Petrill, S. A. (2015). Professional development for early childhood educators: Efforts to improve math and science learning opportunities in early childhood classrooms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(2), 407–422. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037621

- Powell, D. R., Diamond, K. E., Burchinal, M. R., & Koehler, M. J. (2010). Effects of an early literacy professional development intervention on head start teachers and children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(2), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017763

- Raikes, A., Koziol, N., Davis, D., & Burton, A. (2020). Measuring quality of preprimary education in sub-saharan Africa: Evaluation of the measuring early learning environments scale. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 571–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.06.001

- Rao, N., & Lau, C. (2016). Development of a conceptual framework for the Survey of Teachers in Pre-Primary Education (STEPP) survey. UNESCO.

- Rao, N., Pearson, E., Piper, B., & Lau, C. (2022). Building an Effective Early Childhood Education Workforce. In M. Bendini & A. E. Devercelli (Eds.), Quality Early Learning: Nurturing Children’s Potential. Human Development Perspectives. World Bank.

- Rao, N., Richards, B., Sun, J., Weber, A., & Sincovich, A. (2019). Early childhood education and child development in four countries in East Asia and the Pacific. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.08.011

- Schachter, R. E. (2015). An analytic study of the professional development research in early childhood education. Early Education and Development, 26(8), 1057–1085. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2015.1009335

- Su Y., Rao, N., Sun, J., & Zhang, L. (2021a). Preschool quality and child development in China. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 56(3), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.02.003

- Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2019). Understanding teacher shortages: An analysis of teacher supply and demand in the United States. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27(35), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.27.3696

- Sylva, K., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2010). ECERS-E: The early childhood environment rating scale curricular extension to ECERS-R. ERIC.

- Wang, L., Dang, R., Bai, Y., Zhang, S., Liu, B., Zheng, L., Yang, N., & Song, C. (2020). Teacher qualifications and development outcomes of preschool children in rural China. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53(4), 355–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.05.015

- Wong, J. L. N. (2012). How has recent curriculum reform in China influenced school-based teacher learning? An ethnographic study of two subject departments in Shanghai, China. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 40(4), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2012.724654

- Yang, Y., & Rao, N. (2021). Teacher professional development among preschool teachers in rural China. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 42(3), 219–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2020.1726844

- Yang, Y., & Rao, N. (2023). The status, pathways and discourses of professionalism for early childhood education teachers in Chinese policies. International Journal of Educational Development, 99(102760), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2023.102760

- Yoshikawa, H., Leyva, D., Snow, C. E., Treviño, E., Barata, M. C., Weiland, C., Gomez, C. J., Moreno, L., Rolla, A., D’Sa, N., & Arbour, M. C. (2015). Experimental impacts of a teacher professional development program in Chile on preschool classroom quality and child outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 51(3), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038785

- Zheng, M. (2014). On the three years’ project for preschool education (in Chinese). Studies in Early Childhood Education, 8, 34–43.

- Zhou, J., Zhang, L., & Rao, N. (2018). The early developmental status and differences of young children in China: A report from the EAP—ECDS validation study (in Chinese). Global Education, 47(7), 114–128.