Abstract

Background

Following the initial period of hospitalisation, stroke rehabilitation is increasingly occurring within the home. As such, the home setting becomes a critical environment in the context of rehabilitation service provision.

Objectives

This study aimed to explore what factors influence the experiences of stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists participating in home-based rehabilitation.

Methods

A systematic approach to thematic synthesis of qualitative studies began with search term development, followed by database search (CINAHL, Emcare, Medline, Scopus) from inception to 1 November 2022 using keywords and synonyms of ‘stroke survivor’, ‘therapist’, ‘caregiver’, ‘home rehabilitation’ and ‘experience’. Included studies were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist. Data were analysed inductively for themes using a three-step thematic synthesis approach.

Results

A total of 26 studies were included in this thematic synthesis. Across the data, three overarching analytical themes were constructed, including (i) The significance of place, (ii) The impact of relationships, and (iii) The meaning of therapy.

Conclusions

The home setting offers benefits and challenges to delivery and participation in physical rehabilitation after stroke, shaped by various psychosocial and environmental factors that influence outcomes. Altered roles and relationships developed within the home setting influence participatory experience, whilst the setting can offer a familiar and relevant context to promote engagement in meaningful and purposeful therapy. Prior to hospital discharge, therapists who integrate personalised contexts into therapeutic environments can better prepare stroke survivors and caregivers for therapeutic participation within the home. Furthermore, future studies conducted before, during and after therapy focussing on stroke survivor, caregiver and therapist experiences of home-based rehabilitation can provide greater insight into the barriers and facilitators of home-based rehabilitation acceptance, adherence and implementation.

Introduction

Stroke is the second cause of death and disability world-wide [Citation1]. Globally, 12.2 million people had a stroke in 2019 [Citation2] and an overall increase in the ageing population means that stroke prevalence continues to rise [Citation3]. Thanks to continual advances in the diagnosis and treatment of stroke, increasing numbers of people are surviving, with the majority experiencing mild to moderate symptoms [Citation4].

Following an initial period of hospitalisation, the majority of stroke survivors require rehabilitation to maximise functional abilities and prevent deterioration in activity participation [Citation5,Citation6]. With increasing numbers of stroke survivors and finite health care resources, the delivery of rehabilitation services following stroke has necessitated innovative solutions [Citation7]. Home-based rehabilitation models of care following stroke have come into focus, as evidence suggests coordinated care provided through early supported discharge teams is effective in reducing hospital lengths of stay, without reducing functional outcomes [Citation8].

Additionally, efforts have been made to shift rehabilitation outside of hospital environments to either home-based or outpatient-based services due to the considerable financial burden associated with inpatient stroke care [Citation9]. Direct costs associated with home-based therapy have been demonstrably less than those of centre-based facilities (e.g. day hospital or outpatient clinic) [Citation10]. Greater functional benefits can be gained by those receiving home-based therapy in the early period following hospital discharge [Citation10]. Furthermore, early home-based rehabilitation has been found as equally or more effective than centre-based rehabilitation with regards to hospital readmission rates, activity of daily living functioning and social functioning, particularly benefiting younger stroke survivors and those with a stroke of moderate severity [Citation7].

A systematic review exploring the physical effects of home-based therapy following stroke report moderate improvements in physical functioning, with gains more significant for participants with first-ever stroke, who were ≤6 months after stroke onset and had the assistance of a caregiver supporting therapy participation [Citation11]. Caregivers have reported increased levels of satisfaction with regards to stroke knowledge and general satisfaction with home-based rehabilitation compared to that of centre-based rehabilitation [Citation7].

With a view to inform and improve health care delivery for stroke survivors, caregivers and health care professionals working within rehabilitation settings, it is important to seek understanding of the lived experience of those who provide and utilise services [Citation12]. Over the past 20 years an increasing amount of qualitative research has emerged exploring the experiences of stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists who have participated in home-based rehabilitation programs. However as far as the authors are aware, a synthesis of qualitative studies relating to home-based physical rehabilitation experiences following stroke from the multi-perspectives of stroke survivor, caregiver and therapist, has not been conducted.

Qualitative synthesis is a methodology that collects and analyses existing qualitative research to further understanding of the combined implications and collective meaning of the studies included [Citation13]. Conducting a qualitative synthesis offers a condensed thematic understanding of what is currently known about a particular topic in health care, which can then inform health care practice and policy and support further research direction [Citation14,Citation15]. Given the breadth of qualitative research exploring how home-based physical rehabilitation programs following stroke are experienced from the perspectives of stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists, conducting a thematic synthesis offers an in-depth understanding beyond each individual study. The purpose of this synthesis was to answer the question; ‘What influences the experiences of stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists participating in home-based physical rehabilitation after stroke’.

Methods

This study employed a systematic approach to thematic synthesis, originally outlined by Thomas & Harden [Citation16]. Invoking an inductive approach to the construction of themes across primary studies, the thematic synthesis method provides fresh insights into a broad range of experiences across a diversity of contexts [Citation14,Citation16].

This synthesis involved (i) the development of search terms, (ii) data base searching, (iii) screening of eligible studies based on inclusion and exclusion criteria and study selection, (iv) quality evaluation of included studies using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative checklist (CASP) [Citation17], (v) a three-stage thematic synthesis involving data extraction using a line-by-line coding technique, followed by the development of descriptive and analytical themes [Citation16].

The research team included HL, a female Occupational Therapist with 25 years clinical experience who undertook this review as part of her PhD studies; PvV, a female Professor of Physiotherapy specialising in stroke rehabilitation; and MT, a female health researcher with 20+ years of experience teaching and practising qualitative research methods.

Data collection procedures

Search terms and strategies were initially devised in consultation with a university librarian. Based on the purpose and aims of this synthesis, terms and strategies were mapped against the SPIDER tool to frame the search technique (refer to ) [Citation18].

Table 1. SPIDER tool mapping of search terms and strategy.

Under the guidance of MT and PvV, a comprehensive search of four databases (CINAHL, Emcare, Medline and Scopus) was completed by HL from database inception to 1 November 2022, with complementary search methods of reference list scanning and snowballing. All database searches were uploaded into Mendeley Reference Manager and duplicates excluded.

The research team discussed the search yield and studies were included for screening if they were published in English language peer-reviewed journals and used qualitative methods of data collection and analysis. Mixed method studies were only considered if the qualitative component could be extracted and reviewed separately. Individual studies were included if they focussed on physical rehabilitation after stroke and included a form of physical rehabilitation involving the full or part-time presence of a therapist within the home. Exclusion criteria applied if the intervention was conducted in an outpatient or community centre location. Studies focussing on cognitive, psychosocial, speech and language or psychological interventions were excluded. Studies were also excluded if the therapy included forms of tele- or digital interventions/monitoring or technology-facilitated or video-guided interventions.

Quality appraisal of included studies

Two researchers HL and MT critically appraised the included studies using the CASP qualitative checklist with regards to research aims, design, data collection, reflexivity, ethical considerations, data analysis procedures and findings, according to ‘yes’, ‘can’t tell’ or ‘no’ [Citation17].

Thematic synthesis

Data were analysed using the three-step thematic synthesis approach described by Thomas & Harden [Citation16]. Firstly, under the guidance of MT, all text identified as ‘findings’ or ‘results’ from each study was reviewed by HL in its entirety and then line-by-line. Participant quotations and author phrases were initially coded through an inductive process, generated directly from the data to reflect the meaning and text content. The second step conducted by HL in collaboration with MT, involved the development of descriptive themes. Initial codes were grouped and condensed through a process of considering commonalities and diversity relative to the meaning and context of each code. Following this, analytical themes were developed by considering descriptive themes relative to qualitative review aims. Descriptive themes were grouped, providing an interpretive meaning beyond that of each individual study. Analytical themes were iteratively discussed amongst all team members throughout the thematic development process, and differences in opinion between team members were resolved by consensus. To further authenticate and provide evidentiary power to this qualitative synthesis [Citation19], relevant quotations have been incorporated into the findings, presented verbatim from original studies.

Results

Study selection and inclusion

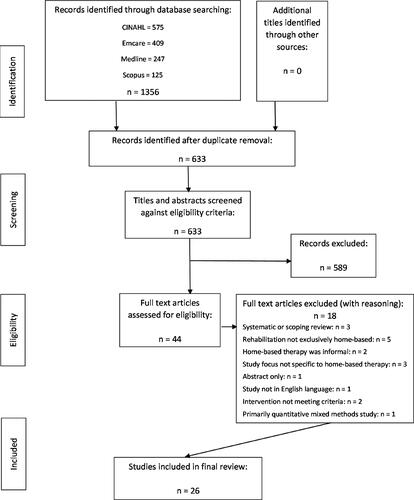

The data base search resulted in a total of 1356 citations, with 723 duplicates. After duplicate removal, 633 study title and abstracts were screened with reference to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Following this, a further 589 studies were excluded. Forty-four (n = 44) articles then underwent a full text screen, resulting in the exclusion of a further 18 studies. The final review consisted of 26 studies.

Details of record identification, screening and eligibility are displayed in , and characteristics of the 26 studies included in the final review are provided in .

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

Characteristics of included studies

Across the 26 studies, the total sample was 464 participants, inclusive of 277 stroke survivors, 84 caregivers and 103 therapists. Participant numbers per study ranged from two to 88. Thirteen studies focussed on stroke survivor experiences [Citation20–32], one study focussed on caregiver experiences [Citation33], four studies focussed on therapist experiences [Citation34–37], five studies explored experiences from the dual perspective of stroke survivor and caregiver [Citation4,Citation38–41], and two studies explored experiences from the dual perspective of stroke survivor and therapist [Citation42,Citation43]. Only one study explored experiences of stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists [Citation44].

Studies had wide ranging representation globally, with research conducted in 15 countries spread across five continents. Studies were published between 1998 – 2022, with 12 of the 26 studies published since 2017 [Citation4,Citation24–26,Citation29,Citation31–33,Citation35,Citation40,Citation41,Citation44].

Of the 26 studies, 24 were qualitative [Citation4,Citation20,Citation22–35,Citation37–44] and two studies [Citation21,Citation36] used a mixed method approach with a clear and separate description of the qualitative findings. Twenty-three of the 26 studies indicated that data collection was primarily obtained through interviews [Citation4,Citation20–34,Citation36–38,Citation40–43], however studies also gathered data through focus groups [Citation31,Citation35,Citation39,Citation42,Citation44], observational techniques [Citation21,Citation43] and field notes [Citation29,Citation40,Citation43]. Each study specified a qualitative methodology, with six studies based on a phenomenological approach [Citation20–23,Citation37,Citation41] and two studies based on grounded theory methodology [Citation34,Citation42]. Data analysis was commonly conducted through a thematic analysis [Citation4,Citation25,Citation28,Citation31,Citation32,Citation36,Citation38,Citation43,Citation44] or a content analysis [Citation23,Citation24,Citation26,Citation27,Citation29,Citation35], however studies also analysed their data using framework analyses methods [Citation39,Citation40].

Of those studies specifying data collection points, 16 reported collecting data after participation in home-based therapy [Citation20–23,Citation25,Citation26,Citation28,Citation30,Citation32,Citation33,Citation37–42], one study reported collecting data prior to participation in home-based therapy [Citation27], one study reported collecting data concurrently with participation in the home-based therapy program [Citation29], and one study reported collecting data both during program participation and after program completion [Citation43].

Determination of quality

The methodological quality of studies varied, with three of the 26 studies satisfying all 10 criteria included in the CASP checklist (refer to ). Remaining studies demonstrated moderate to high quality methodological rigour, with all studies appropriately utilising a qualitative methodology to address their research question, providing a clear aim of their research and included a comprehensive description of findings. Observed methodological weaknesses identified across the studies included an unclear justification of research design, lack of examination or reflection upon the relationship between the researcher and participants, insufficient explanation of ethical issues and/or the lack of a clear description of data analysis procedures. Of those studies determined to be of a higher quality, the majority were published after 2019 [Citation24,Citation25,Citation32,Citation35,Citation40,Citation41].

Table 3. Methodological quality of included studies mapped against the CASP tool.

Thematic synthesis findings

Within the context of home-based rehabilitation, the experiences of stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists form a multifaceted picture. Initial coding of the 26 studies resulted in 143 codes, which were subsequently grouped into 23 descriptive codes. Following this, three overarching analytical themes were constructed, encompassing the experience of home-based rehabilitation after stroke.

The analytical themes are: (i) The significance of place, (ii) The impact of relationships, and (iii) The meaning of therapy. Source documents for the descriptive codes and analytical themes are presented in .

Table 4. Source documents for descriptive codes and analytical themes.

Analytical themes

The significance of place

‘The significance of place’ was generated from data across 16 of the 26 studies [Citation4,Citation20,Citation22,Citation24,Citation25,Citation27,Citation28,Citation30–32,Citation34–36,Citation38,Citation39,Citation42]. Within these 16 studies, home held significant meaning for stroke survivors and caregivers, also recognised by therapists who delivered home-based therapy.

Following stroke and prior to hospital discharge, stroke survivors described the significance of home from an individual perspective, indicating a yearning to return home [Citation20,Citation27,Citation38] as a place of comfort, where unlike the hospital environment, time and space could be structured by personal needs and desires, supporting individualised, routine practice of therapeutic programmes [Citation4,Citation20,Citation25,Citation32,Citation42]. The transition from hospital to home was also viewed as a significant and positive psychological step within the recovery journey after stroke [Citation4,Citation20].

Once home, the familiar environment contributed to feelings of relaxation, which for some stroke survivors helped maximise outcomes during therapy sessions [Citation30,Citation39,Citation42]. However, for others, the less formal nature of home hindered motivation to participate in therapy [Citation22,Citation42]. Being at home contributed to a sense of security, improving stroke survivor confidence [Citation24]. The relative privacy of home surroundings was both valued as providing an individual space with limited distraction, enabling focussed participation in therapy [Citation38,Citation42], while also acknowledged as potentially isolating and lonely [Citation22], with limited social engagement after stroke [Citation30].

Stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists acknowledged the safety benefits of rehabilitation occurring within the home environment, where therapists were able to assess and identify areas that necessitated modification, prompting adaptations to the home to safeguard stroke survivors, whilst allowing increased independence in daily living [Citation22,Citation32,Citation39]. However some therapists noted that during home-based rehabilitation their own personal safety was occasionally compromised, as equipment used during therapy sessions was not always adjustable or available and adequate space was sometimes lacking [Citation42].

Stroke survivors and caregivers described practical advantages of receiving rehabilitation within the home. This included the convenience, cost and time savings related to less travel and a reduced burden on caregivers, who were often responsible for supporting stroke survivor attendance and participation in therapy [Citation22,Citation32,Citation38,Citation42]. Despite these advantages, therapists acknowledged that travelling to and from home visits required extra planning and time, which could impact on session length [Citation42].

Stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists described how the home environment helped shape goal setting, assessment and delivery of intervention throughout the period of rehabilitation. Stroke survivors could set goals and evaluate progress within their own environments, as at home it was easy for me to notice what was important to practice [Citation28, p. 80]. Therapists described an appreciation of how the impacts of stroke affected a survivor’s ability to function within their own environment, such as how many steps, how narrow the doorways are [Citation34, p. 1937]. Exposure to conditions within the home environment was considered valuable, as challenges that were met by stroke survivors after returning home from hospital were not always anticipated or accurately predicted prior to discharge [Citation24]. Thus, therapists reported a greater understanding of issues when observed within the home, providing increased focus for treatment [Citation36].

At home, stroke survivors were immersed in therapeutic opportunities, where participation in everyday tasks increased the intensity of practice, constantly testing and challenging abilities [Citation4,Citation35]. In turn, stroke survivors reported increased motivation to participate in exercises that promoted a return to valued activities [Citation4] or tasks that were a necessary part of everyday life; I am so fortunate that I need to climb eleven steps just to get into the house. That’s my daily exercise, twice a day, up and down [Citation31, p. 2571]. Despite the home environment providing an enduring therapeutic challenge which provided some stroke survivors with hope, others were reminded of the difficulties presented by everyday activities following their stroke [Citation4].

The impact of relationships

The theme entitled ‘The impact of relationships’ was generated from data across 22 of the 26 studies [Citation4,Citation20,Citation22–26,Citation28,Citation30–37,Citation39–44]. The nature of the relationship between stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists was found to influence the therapeutic process within the home environment, where an understanding of roles and responsibilities influenced engagement in therapy, and effective communication was perceived as integral to determining successful outcomes.

Two studies discussed stroke survivors and caregivers accepting, valuing, and eagerly anticipating therapist visits to their home [Citation20,Citation22]. Compared to a conventional clinical environment, therapists described a changed relationship with stroke survivors and caregivers within their home as you are there on their terms, so your role is very different in their minds [Citation34, p. 1936]. Stroke survivors commonly referred to therapists as trusted experts [Citation24,Citation32] and considered them to be in charge and in control of therapy delivery, owing to their professional expertise [Citation42, p. 62].

Within the home environment, therapists were often perceived as guests and developed a friendship with stroke survivors and caregivers [Citation4,Citation20,Citation34,Citation35,Citation39,Citation42,Citation43]. Therapists observed assuming the role of guest facilitated the empowerment of stroke survivors and caregivers, enabling the home occupants a stronger voice in reporting their needs and wishes [Citation35]. As such, therapists did not always assume a leading role in therapeutic scenarios, which some therapists viewed as more relaxing, actualising a more equal relationship [Citation4,Citation34]. Some therapists reported utilising a flexible wait and see strategy during sessions, whereby stroke survivors presided over activity choice [Citation37, p.784]. Other therapists reported a lack of confidence in taking the lead within the home environment, affecting their ability to control the sessions [Citation42].

The change in roles assumed by the therapist allowed the stroke survivor to take initiative in their own therapy participation, effectively improving survivor confidence and prompting goal setting [Citation43]. The home environment offered a natural context for dialogue between health professional and stroke survivor, resembling a partnership, thus allowing stroke survivors an opportunity to express fear and uncertainty [Citation28]. Time was deliberately spent during therapy sessions talking and listening, where stroke survivors described conversing freely with therapists, counteracting social expectations to limit or control their emotions [Citation22,Citation36,Citation42]. The home was viewed as a safe space to share ones feelings, where stroke survivors described having really good physios who have been sensitive to emotional needs but that’s possibly really important to be aware of…you’ll go into people’s houses and you don’t know what kind of emotional state they’re going to be in and most of the time they’ll be fine but there will be sometimes…there will be a lot that are depressed, that are angry…just wanting to have a big cry [Citation22, p. 10].

Contact with therapists was perceived by stroke survivors as vital, providing supervision, guidance, support and motivation to continue with ongoing participation in therapeutic programmes [Citation22,Citation23,Citation26,Citation40]. Stroke survivors understood the role of the therapist was to guide recovery and this was enabled when therapists were competent communicators, engaged during therapy sessions, displayed empathy and enthusiasm [Citation30]. Adherence to home-based exercise was less likely to occur when the program was poorly supported by health professionals, particularly if the program lacked adequate supervision within the home [Citation26]. Support from therapists, who were trusted and provided extra motivation, enabled ongoing exercise adherence [Citation25], as did feeling accountable and obligated to meet therapist expectations; I need some sort of reference point so that I can see whether I am exercising correctly. If I feel that I am just doing something, I become easily distracted [Citation31, p. 2571].

Therapists recognised that their role included the provision of caregiver support by providing education and instruction, including practical solutions and the provision of motivational counselling and coaching [Citation35,Citation44]. However, therapists were conscious to avoid overburdening caregivers, as some caregivers reported that accumulative responsibilities could limit their ability to assist stroke survivor participation in home therapy programmes [Citation33,Citation41,Citation44]. Additionally, stroke survivors expressed a preference for exercises to be delivered by therapists rather than caregivers due to their own concerns about overburdening caregivers, as they will get tired. The person will get tired and say ‘No’ [Citation44, p. 8]. Regardless, stroke survivors emphasised the supportive role provided by caregivers, acknowledging that their presence could promote participation in therapy [Citation32,Citation40]. In one study, training together resulted in stroke survivors and caregivers spending more time with each other, which for some participants resulted in closer relationships, however others found the experience stressful, straining their relationship [Citation41]. Caregivers described the importance of continually challenging and supporting stroke survivors, at times stifling the urge to make comments about therapy, to maintain their marital relationship and avoid becoming a ‘proxy therapist’ [Citation4, p. 307].

The meaning of therapy

The third theme entitled ‘The meaning of therapy’ was generated from data spanning 25 of the 26 studies [Citation4,Citation20–31,Citation33–42,Citation44]. This theme encompassed experiences of stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists before, during and after participation in therapy, positioning the meaning of therapy within the complex journey of recovery after stroke.

Before leaving hospital, stroke survivors questioned their competency and capacity to adapt to life after stroke within a home environment [Citation20]. For those returning home to a therapy program, participation was anticipated and therapists were expected to incorporate daily activities and the environment into their rehabilitation; they can see what my place looks like…so they can adapt (my rehab) to it and make sure that I can master my environment more easily than could do here (in hospital) [Citation27, p. 4]. Improvement in efficiency and quality of task performance was an expectation held by stroke survivors prior to participation in home-based therapy [Citation21]. Therapists perceived their role as preparing the stroke survivor for life, made possible within the home by incorporating daily tasks to achieve optimal and safe independent functioning [Citation34].

At home, stroke survivors were immersed within familiar environments, activities and routines, providing an increased sense of normality that helped direct a therapeutic process [Citation20]. Recovery from stroke was viewed as an evolving journey, with normality described as the endpoint [Citation39]. Many stroke survivors perceived participation in home-based therapy as a means to achieve their goals, which often revolved around improved function and resumption of roles, enabling a return to a life they longed for; what I wanted was to rebuild my physical and mental strength so I get back to my regular activities and regular life [Citation24,Citation27, p. 24, Citation28,Citation30–32,Citation36,Citation38–40].

Working towards personal goals provided stroke survivors with hope and motivation throughout therapy sessions, thereby contributing to sustained adherence to therapeutic programs [Citation25,Citation30,Citation40]. Therapists noted that goals focussed on real life issues were observed to be highly motivating [Citation36]. Caregivers perceived home-based exercises as valuable, where it was very much a practical focus for the exercises…So that not only was he doing the exercises but there was a purpose involved to perform the exercises [Citation40, p. 294]. Caregivers learnt to understand stroke survivor limitations at the same time as appreciating their potential ability, which resulted in less worry, simultaneously increasing hope and confidence in the future [Citation39]. However, caregivers also identified that not all goals could be resolved within the scope of a home-based rehabilitation program, which was perceived as frustrating [Citation39].

The home setting enabled in-situ practice of relevant and practical activities, tailor made for individuals within the context of their everyday lives [Citation4,Citation22,Citation23,Citation28,Citation38,Citation40,Citation42]. Therapists were perceived to provide a combination of generic therapy, such as training of motor skills, and specific skills relating to tasks performed within home environments such as showering, where intervention was a combination of education and direct practice [Citation24]. Caregivers observed that active participation within home-based therapy was seen to build confidence and independence [Citation39]. Practicing functional tasks within the home during therapy supported stroke survivors’ ability to cope with life after stroke on a practical level, increasing the meaning and relevance of therapy [Citation28]. Exercises were perceived as positive and meaningful when they were linked to activities of daily living [Citation41], where participation in home-based tasks sustained practice during therapy; I got so into doing the work (pulling weeds) that I forgot I was sick [Citation29, p. 193].

Therapists working in the home setting assisted survivors to regain continuity in life after stroke via associations or links to pre-stroke activities, actively seeking out key tasks unique to each survivor [Citation37]. This therapeutic strategy promoted ongoing problem solving for stroke survivors, where meaningful activity participation led to new developments within an evolving recovery journey [Citation37]. Thus, the home environment provided therapists with opportunities to design appropriate therapy programs based on observable assessment of difficulties in context [Citation42]. Treatment success was generally based on subjective measures of goal attainment, as standardised outcome measures inadequately accounted for what the stroke survivor or therapist was trying to achieve [Citation34].

Perceptions of the rationale for therapy influenced participation, where stroke survivors who had little knowledge of the benefits of therapy were less likely to adhere to home-based programs [Citation26]. The difficulty level of prescribed exercises also influenced a stroke survivors ability to sustain participation; Some of the exercises were impossible to do…if I came across a hard exercise, I didn’t do it otherwise I would get frustrated [Citation25, p. 4]. Personal factors such as boredom, fatigue, pain or frustration with a lack of observable progress was found to hinder exercise adherence, and the influence of socio-cultural norms was also found to limit participation, owing to various spiritual customs or social stigma associated with disability after stroke [Citation26,Citation40].

Integrating therapy into everyday life was challenging, as participation took time, was physically demanding and exhausting, with stroke survivors acknowledging difficulties sustaining motivation for long periods [Citation31,Citation41]. Caregivers were aware that issues such as pain and fatigue limited participation in home exercise programs, however despite their belief that routine practice supported goal attainment, caregivers found it difficult to balance their supporting role with other responsibilities [Citation33,Citation44].

Perceptions regarding duration of program differed, with some stroke survivors suggesting five to six weeks was sufficient, whilst others preferred more time to help redefine important aspects of their lives [Citation30,Citation40]. Stroke survivors expected that ongoing involvement in therapy would result in further improvement in function, where more exercise would lead to recovery [Citation32,Citation40,Citation44]. Therapists described the benefits of a flexible, less rigid session structure, where therapy could be led by stroke survivors and tailored according to individual and caregiver needs [Citation35,Citation37].

Self-management of practice was supported by integrating exercise into an everyday routine and stroke survivors believing the benefits of therapy [Citation26,Citation33,Citation40]. As a training program progressed, stroke survivors learnt to vary their own practice and required less assistance from the therapist to adapt activities [Citation29]. In one study, the use of a training diary helped maintain motivation, allowing stroke survivors to monitor progress [Citation28]. Home-based intervention was perceived to hasten recovery, enabling improved functional ability, reducing fear and anxiety, subsequently increasing stroke survivor confidence [Citation39].

Discussion

This thematic synthesis provides insight into the complexity of influences that stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists experience when participating in home-based physical rehabilitation. Home-based rehabilitation following stroke can be shaped by an interaction between various psychosocial and environmental factors [Citation45]. Thematically, the three influences on experience generated from this synthesis include the significance of the home environment within which rehabilitation is located, the impact that relationships have throughout the home rehabilitation process, and the personal meaning ascribed to therapy in the context of home-based rehabilitation. It is the interplay between the influences on experience and the perspectives of those involved that contribute to the complex nature of a home-based rehabilitation experience.

The significance of place is a widespread phenomenon, with stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists throughout various countries highlighting the benefits and challenges of undertaking rehabilitation within the home context. Following stroke, survivors and caregivers have been found to experience a deep sense of loss and uncertainty, impacting upon self-concept [Citation46,Citation47]. For the stroke survivor, the act of returning home after hospital admission can have a positive influence on affect, where a sense of belonging and connectedness to home has been found to improve well-being and restore functioning [Citation48]. Therapy occurring in the home environment allows for the development of context dependent goals [Citation43] and transfer of skills, as practice occurs in ‘real world’ situations, using objects of relevance to the stroke survivor [Citation49]. Recognising the benefits of enhanced activity engagement through the provision of familiar and meaningful tasks and objects, therapists have sought to extend these concepts by replicating aspects of the home environment through environmental enrichment in clinical settings [Citation50,Citation51].

To facilitate acceptance, adherence and continued participation in home-based therapy programs, it is necessary for physical environments to be compatible with rehabilitation requirements. Many homes are not necessarily designed for the purposes of therapy [Citation52], with architectural, interior design and ambient features found to either promote or prevent optimal rehabilitation after stroke [Citation48]. By informing stroke survivors and caregivers of possible environmental considerations required within the home setting to enable ongoing home-based rehabilitation prior to hospital discharge, therapists could further support practical aspects of the transition to home process. Additionally, given the shift towards stroke rehabilitation increasingly occurring within the home, more studies focussing on facilitators and barriers to the implementation of home rehabilitation and the impact of the environment on therapy participation are recommended.

The relational aspect of home-based stroke rehabilitation featured prominently across the studies included in this thematic synthesis. Relationships between each stroke survivor, caregiver and therapist were considered an essential element of the recovery process. Collaborative communication between stroke survivors and therapists is important in supporting rehabilitation participation and outcomes [Citation53,Citation54]. A well-functioning therapeutic relationship between therapists and stroke survivors has been found to support effective goal setting and achievement, promoting motivation throughout therapy [Citation53]. The caregiver-therapist relationship is also critical, with caregivers highlighting the importance of therapist-led education, training and information provision supporting fulfilment of caregiving role requirements [Citation55].

Stroke survivors and therapists assume different roles depending on the setting in which rehabilitation occurs, which influences therapeutic relationships. Roles assumed by stroke survivors whilst participating in therapy at home are much more than the passive roles observed in hospital environments [Citation43]. Therapist roles extend in the home beyond the more traditional role set of ‘teacher/expert’ in the hospital environment ( [Citation43], p 370). Thus, the home environment provides therapists and stroke survivors opportunities to change or extend roles, allowing for the development of a more meaningful therapeutic relationship, where the needs of stroke survivors can be better understood and acknowledged, positively influencing health and well-being outcomes [Citation48].

A prominent influence affecting stroke survivor, caregiver and therapist experience before, during and after participation in home-based therapy can be the meaning that individuals ascribe to therapy. Each stroke survivor and caregiver approached therapeutic participation with an expectation and intention that resulted in an emotional response, signifying personal meaning-making within the context of their home environment. By assuming a responsibility to (re)prepare a stroke survivor for life [Citation34] and support stroke survivors to regain continuity in life [Citation37], it is recommended therapists continue to undertake a process of integrating personalised contexts into therapy program development. Given the significance of place that home represents, the setting provides an ideal environment and opportunity for therapists to create and deliver rehabilitation programs of maximal relevance, adding value to the everyday lives of stroke survivors and their caregivers.

From this review, 21 of the 26 studies focussed on stroke survivor perspectives, either individually, in a dyad or triadic circumstance. Therapists’ perspectives were explored in six of the 26 studies, and caregivers’ perspectives were explored twice. It is evident that to date, qualitative research exploring the experiences of home-based physical rehabilitation has been heavily weighted towards the stroke survivor. Given that caregivers are often expected to assume responsibilities of support towards ongoing recovery once the stroke survivor has transitioned from hospital to home [Citation56], it would appear an imperative to further investigate caregiver perceptions and experiences of home-based rehabilitation. Additional exploration of therapist perspectives would enable greater insight into the benefits and challenges of delivering home-based rehabilitation, thus contributing to the knowledge base encompassing stroke recovery for survivors and their caregivers, further informing therapy service development and provision.

This review also highlighted data collection commonly occurring at only one time point, primarily taking place after program completion, with 16 of the 26 studies collecting data at therapeutic program conclusion. Gathering data prior to and during participation in home-based rehabilitation programs is useful in exploring stroke survivor, caregiver and therapist expectations which can influence program acceptance and adherence, as well as providing opportunities to identify barriers and facilitators to participation in-situ. It is therefore recommended that future studies include multiple data collection points, including before, during and after therapeutic program participation.

Limitations

There are limitations to this review. Firstly, studies were limited to those written in English, and although research conducted across 15 countries was included, excluding publications based on the mono-lingual abilities of the research team may have resulted in an incomplete synthesis with limited wide ranging ethno-cultural representation. Secondly, although the CASP tool is the most frequently reported quality appraisal tool used in social and health-related qualitative synthesis and recommended for novice researchers [Citation57], there remains relatively little guidance on tool application and as such, appraisal results may lack reproducibility [Citation15].

Conclusion

Home-based rehabilitation has been expansively integrated across a wide range of health systems and cultures, providing meaningful and practical physical rehabilitation to meet the needs of stroke survivors and their caregivers worldwide. Whether delivered as part of an early supported discharge program or many years after stroke, home-based rehabilitation provides stroke survivors with familiar and comfortable surrounds within which to participate in therapy. The home setting offers stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists the opportunity to participate in education and training programs that are goal driven, unique to each individual and based on relevant tasks designed to enable a return to functional activities and meaningful roles. Effective communication and a partnership between stroke survivors, caregivers and therapists plays an integral role in successful home-based rehabilitation.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Debbie Booth, University of Newcastle Library for her assistance with search term development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- GBD 2016 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):439–458.

- World Stroke Organization. World Stroke Organisation Annual Report 2021. Geneva: world Stroke Organization; 2021.

- Li L, Scott CA, Rothwell PM. Trends in stroke incidence in high-income countries in the 21st century. Stroke. 2020;51(5):1372–1380.

- Lou S, Carstensen K, Møldrup M, et al. Early supported discharge following mild stroke: a qualitative study of patients’ and their partners’ experiences of rehabilitation at home. Scand J Caring Sci. 2017;31(2):302–311.

- Langhorne P, Bernhardt J, Kwakkel G. Stroke rehabilitation. Lancet. 2011;377(9778):1693–1702.

- Alexander T, Capell J, Simmonds F. NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation Rehabilitation Unwarranted Clinical Variation Project FINAL REPORT. Australasian Rehabilitation Outcomes Centre, Australian Health Services Research. University of Wollongong; 2017.

- Siemonsma P, Döpp C, Alpay L, et al. Determinants influencing the implementation of home-based stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review. Disability Rehabil. 2014;36(24):2019–2030.

- Langhorne P, Baylan S. Early supported discharge trialists. Early supported discharge services for people with acute stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7(7):CD000443-CD.

- Godwin KM, Wasserman J, Ostwald SK. Cost associated with stroke: outpatient rehabilitative services and medication. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2011;18:676–684.

- Hillier S, Inglis-Jassiem G. Rehabilitation for community-dwelling people with stroke: home or Centre based? A systematic review. Int J Stroke. 2010;5(3):178–186.

- Chi N-F, Huang Y-C, Chiu H-Y, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of home-based rehabilitation on improving physical function among home-dwelling patients with a stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(2):359–373.

- VanderKaay S, Moll SE, Gewurtz RE, et al. Qualitative research in rehabilitation science: opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Disability Rehabil. 2018;40(6):705–713.

- Bearman M, Dawson P. Qualitative synthesis and systematic review in health professions education. Med Educ. 2013;47(3):252–260.

- Flemming K, Noyes J. Qualitative evidence synthesis: where are we at? Int J Qual Methods. 2021;20:160940692199327.

- Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Res Methods Med Health Sci. 2020;1(1):31–42.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP qualitative studies checklist 2022. 2020 Aug 18. Available from: https://casp-uk.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf.

- Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–1443.

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Presenting syntheses of qualitative research findings. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York: springer Publishing Company; 2007. p. 235–262.

- Collins G, Breen C, Walsh T, et al. An exploration of the experience of early supported discharge from the perspective of stroke survivors. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2016;23(5):207–214.

- Gillot AJ, Holder-Walls A, Kurtz JR, et al. Perceptions and experiences of two survivors of stroke who participated in constraint-induced movement therapy home programs. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57(2):168–176.

- Hale L, Bennett D, Bentley M, et al. Stroke rehabilitation – comparing hospital and home-based physiotherapy: the patient’s perception. NZ J Physiother. 2003;31(2):84–92.

- Kåringen I, Dysvik E, Furnes B. The elderly stroke patient’s long-term adherence to physiotherapy home exercises. Adv Physiother. 2011;13(4):145–152.

- Kylén M, Ytterberg C, von Koch L, et al. M. How is the environment integrated into post-stroke rehabilitation? A qualitative study among community-dwelling persons with stroke who receive home rehabilitation in Sweden. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;20:1–11.

- Levy T, Christie J, Killington L, et al. “Just that four letter word, hope”: stroke survivors’ perspectives of participation in an intensive upper limb exercise program; a qualitative exploration. Physiother Theory Pract. 2021;37(11):1624–38.

- Mahmood A, Nayak P, Kok G, et al. Factors influencing adherence to home-based exercises among community-dwelling stroke survivors in India: a qualitative study. Eur J Physiother. 2021;23(1):48–54.

- Nordin Å, Sunnerhagen KS, Axelsson ÅB. Patients’ expectations of coming home with very early supported discharge and home rehabilitation after stroke - an interview study. BMC Neurol. 2015;15(235):235–235.

- Reunanen MAT, Järvikoski A, Talvitie U, et al. Individualised home-based rehabilitation after stroke in Eastern Finland - the client’s perspective. Health Soc Care Commun. 2016;24(1):77–85.

- Rowe VT, Neville M. Client perceptions of task-oriented training at home: “I forgot I was sick”. OTJR. 2018;38(3):190–195.

- Taule T, Strand LI, Skouen JS, et al. Striving for a life worth living: stroke survivors’ experiences of home rehabilitation. Scand J Caring Sci. 2015;29(4):651–661.

- Dongen L, Hafsteinsdóttir TB, Parker E, et al. Stroke survivors’ experiences with rebuilding life in the community and exercising at home: a qualitative study. Nurs Open. 2021;8(5):2567–2577.

- Cameron TM, Koller K, Byrne A, et al. A qualitative study exploring how stroke survivors’ expectations and understanding of stroke early supported discharge shaped their experience and engagement with the service. Disabil Rehabil. 2022:1–8.

- Scorrano M, Ntsiea V, Maleka D. Enablers and barriers of adherence to home exercise programmes after stroke: caregiver perceptions. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2018;25(7):353–364.

- Hale LA, Piggot J. Exploring the content of physiotherapeutic home-based stroke rehabilitation in New Zealand. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(10):1933–1940.

- Van Der Veen DJ, Döpp CME, Siemonsma PC, et al. Factors influencing the implementation of home-based stroke rehabilitation: professionals’ perspective. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0220226.

- von Koch L, Holmqvist LW, Wottrich AW, et al. Rehabilitation at home after stroke: a descriptive study of an individualized intervention. Clin Rehabil. 2000;14(6):574–583.

- Wottrich AW, von Koch L, Tham K, et al. The meaning of rehabilitation in the home environment after acute stroke from the perspective of a multiprofessional team (including commentary by Jensen GM). Phys Ther. 2007;87(6):778–788.

- Cobley CS, Fisher RJ, Chouliara N, et al. A qualitative study exploring patients’ and carers’ experiences of early supported discharge services after stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(8):750–757.

- Gilbertson L, Ainge S, Dyer R, et al. Consulting service users: the stroke association home therapy project. Br J Occup Ther. 2003;66(6):255–262.

- Schnabel S, van Wijck F, Bain B, et al. Experiences of augmented arm rehabilitation including supported self-management after stroke: a qualitative investigation. Clin Rehabil. 2021;35(2):288–301.

- Stark A, Färber C, Tetzlaff B, et al. Stroke patients’ and non-professional coaches’ experiences with home-based constraint-induced movement therapy: a qualitative study. Clin Rehabil. 2019;33(9):1527–1539.

- Stephenson S, Wiles R. Advantages and disadvantages of the home setting for therapy: views of patients and therapists. Br J Occup Ther. 2000;63(2):59–64.

- von Koch L, Wottrich AW, Holmqvist LW. Rehabilitation in the home versus the hospital: the importance of context. Disabil Rehabil. 1998;20(10):367–372.

- Scheffler E, Mash R. Figuring it out by yourself: perceptions of home-based care of stroke survivors, family caregivers and community health workers in a low-resourced setting, South Africa. Afr J Primary Health Care Fam Med. 2020;12(1):1–12.

- Cunningham P, Turton AJ, Van Wijck F, et al. Task-specific reach-to-grasp training after stroke: development and description of a home-based intervention. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(8):731–740.

- Satink T, Cup EH, Ilott I, et al. Nijhuis-van der sanden MW. Patients’ views on the impact of stroke on their roles and self: a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(6):1171–1183.

- Salter K, Hellings C, Foley N, et al. The experience of living with stroke: a qualitative meta-synthesis. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(8):595–602.

- Marcheschi E, Koch V, Pessah‐Rasmussen L, et al. M. Home setting after stroke, facilitators and barriers: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(4):e451–e9.

- Hsieh Y-W, Chang K-C, Hung J-W, et al. Effects of home-based versus clinic-based rehabilitation combining mirror therapy and task-specific training for patients with stroke: a randomized crossover trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(12):2399–2407.

- Janssen H, Ada L, Bernhardt J, et al. An enriched environment increases activity in stroke patients undergoing rehabilitation in a mixed rehabilitation unit: a pilot non-randomized controlled trial. Disability Rehabil. 2014;36(3):255–262.

- White JH, Bartley E, Janssen H, et al. Exploring stroke survivor experience of participation in an enriched environment: a qualitative study. Disability Rehabil. 2015;37(7):593–600.

- Axelrod L, Fitzpatrick G, Burridge J, et al. The reality of homes fit for heroes: design challenges for rehabilitation technology at home. J Assistive Technol. 2009;3(2):35–43.

- Lawton M, Haddock G, Conroy P, et al. Therapeutic alliances in stroke rehabilitation: a meta-ethnography. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(11):1979–1993.

- Luker J, Lynch E, Bernhardsson S, et al. Stroke survivors’ experiences of physical rehabilitation: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(9):1698–1708.e10.

- Denham AMJ, Wynne O, Baker AL, et al. The long-term unmet needs of informal carers of stroke survivors at home: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Disability Rehabil. 2022;44(1):1–12.

- Kokorelias KM, Lu FKT, Santos JR, et al. Caregiving is a full-time job" impacting stroke caregivers’ health and well-being: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(2):325–340.

- Dalton J, Booth A, Noyes J, et al. Potential value of systematic reviews of qualitative evidence in informing user-centered health and social care: findings from a descriptive overview. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;88:37–46.