ABSTRACT

Medical Professionalism (MP) defined as values, behaviours and attitudes that promote professional relationships, public trust and patient safety is a vital competency in health profession education. MP has a distinctive uniqueness due to cultural, contextual, conceptual, and generational variations. There is no standard instructional strategy to probe the understanding of MP in a cohesive, structured, interactive manner. This study aimed to investigate undergraduate medical students’ understanding of MP using express team-based learning (e-TBL) at both campuses of Royal College of Surgeons Ireland (RCSI). Using the key principles of a sociocultural theoretical lens in adult learning theory, we designed e-TBL as a context-learning-based educational strategy. We conducted three e-TBL sessions on cross-cultural communication and health disparities, a reflective report on clinical encounters, and professionalism in practice. We collected, collated, and analyzed the student experiences qualitatively using data gathered from team-based case discussions during e-TBL sessions. A dedicated working group developed very short-answer questions for the individual readiness assurance test (IRAT) and MP-based case scenarios for team discussions. In this adapted 4-step e-TBL session, pre-class material was administered, IRAT was undertaken, and team-based discussions were facilitated, followed by facilitator feedback. A qualitative inductive thematic analysis was performed, which generated subthemes and themes illustrated in excerpts. Our thematic analysis of data from 172 students (101 from Bahrain and 71 from Dublin) yielded four unique themes: incoming professional attitudes, transformative experiences, sociological understanding of professionalism, and new professional identity formation. This qualitative study provides a deeper understanding of medical students’ perceptions of medical professionalism. The generated themes resonated with divergent and evolving elements of MP in an era of socioeconomic and cultural diversity, transformative experiences, and professional identity formation. The core elements of these themes can be integrated into the teaching of MP to prepare fit-to-practice future doctors.

Background

Medical Professionalism (MP) is a vital competency for undergraduate medical students worldwide [Citation1]. At Royal College of Surgeons Ireland (RCSI) University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin and Bahrain campus, MP is defined as ‘forming values and developing behaviours and attitudes which foster professional relationships, promote public trust and enhance patient safety’ [Citation2]. By providing this insightful vision which focuses on doctors’ knowledge, clinical skills and judgement, MP is intricately woven into the fabric of the curricular institution. Additionally, MP has recently been introduced in the critical vertical theme of Personal and Professional Identity Development (PPID), spiralled, and integrated throughout the revised curriculum. PPID theme focuses on the process through which medical students internalize their sense of professional ‘self’. This internalization known as Professional Identity Formation (PIF) includes embracing the roles, values and beliefs associated with the medical profession by an explicit education of MP [Citation3]. However, an explicit delivery of MP cognitive base alone will not be suffice to ensure a keen participation and engagement of medical students [Citation4]. Other research has also highlighted poor attention and the lack of perceived relevance of the subject by students, primarily due to ineffective teaching and assessment modalities [Citation5,Citation6].

The multi-dimensional nature of MP has traditionally made it challenging to teach and assess it as a core competency in undergraduate medical education. Consequently, medical fraternity has struggled to develop a consensus on standard teaching and assessment tools for MP to effectively achieve the desired outcomes [Citation7,Citation8]. In this sense, MP can be viewed as a culturally situated practice shaped by the social and cultural contexts in which medical professionals operate. Vygotsky’s sociocultural cognitive learning theory and Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) emphasize the role of social interactions and cultural experiences in shaping an individual’s learning and development [Citation9,Citation10]. Within the context of medical education and the development of MP, both theories can provide valuable insights into how individuals learn, develop, and apply their professional competencies [Citation11]. Moreover, SCT posits that individuals learn through observation, modelling, and imitation [Citation12]. Thus, applying MP concepts through role modelling in clinical practice can significantly impact the development of professionalism among medical students. Educators can facilitate the development of professional competencies among medical students by creating a supportive environment and providing opportunities for feedback and reflection.

Team-Based Learning (TBL) is a teaching approach that aligns with social constructivists. TBL is a comprehensive, student-centred, structured approach for promoting active learning [Citation13–15]. TBL extends beyond the simple transfer of knowledge to the application of knowledge through problem solving [Citation16,Citation17]. The use of TBL in teaching MP is especially beneficial, as it encourages students to learn through social interactions with peers and experts and develop their ethical and social values in a community of practice [Citation18,Citation19]. TBL provides opportunities for students to engage with the multidimensional nature of MP through a series of carefully planned steps, including pre-class preparation, the use of Readiness Assurance Tests (RAT), immediate feedback, team problem-solving activities, and peer review [Citation19–21]. This approach encourages students to become independent and self-directed learners, fostering their development as professionals who can operate effectively, both alone and in teams [Citation17].

Although TBL has been widely adopted in clinical and pre-clinical health professions, its use in MP-related modules remains minimal [Citation22–25]. However, designing a full-scale TBL remains a functional barrier for its seamless application [Citation26]. The caveats of its implementation include a lack of resources, trained faculty, critical mass, and institutional support. Express Team Based Learning (e-TBL) is a modified version of TBL that utilizes short, focused activities and immediate feedback to support student learning and engagement [Citation27]. Combining individual and team-based activities, e-TBL encourages significant learning through interaction, reflection, discussions and feedback toward a shared objective [Citation28,Citation29]. This structured teaching pedagogy, with sociocultural theories as its educational underpinning, leads to a deep understanding of the subject material and retention of information over time [Citation30].

Using the key principles of the sociocultural theoretical lens of adult learning theory, our qualitative study aimed to determine how medical professionalism is perceived and applied by undergraduate medical students. An understanding of the elements of MP among professionals working alone and in teams will help medical educators prepare potential curriculum amendments. Finally, this research highlights the use of technology-based learning that allows students and faculty to improve their technology-enhanced engagement skills in a configured manner.

Materials and methods

Study objective

This qualitative study aimed to explore the understanding of RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences Dublin and Bahrain undergraduate medical students regarding MP using case scenarios in e-TBL.

Settings

RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences is a global medical institution that fosters transnational collaborations throughout Europe, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. RCSI Bahrain, as a constituent university of RCSI, operates as an international branch campus. Both campuses prioritize student-centred curricula, aiming to create a global educational community that offers exceptional transnational health professions education [Citation31]. In 2019, RCSIat both campuses implemented Transforming Health Education Program I (THEP I), a five-year undergraduate medical program using a blended teaching and learning approach. It includes lectures, tutorials, seminars, and practical sessions to reinforce and enhance the understanding of fundamental concepts. In the first and second years, students were introduced to the integral concepts of MP. However, unlike other science modules in the same years, there were no small or large group tutorials or seminars to reinforce the understanding of MP. In Semester I of the third year, the students covered evidence-based medicine, public health, MP, leadership, and precision medicine before the commencement of clinical placements. A multi-strand 6-week module, Tomorrow’s Health Professionals (THP), covering MP, leadership, quality improvement science, and precision medicine, was introduced during the academic year 2021–22 to year 3 medical students. This was an attempt to provide students with knowledge of the practical aspects of the abovementioned strands across the continuum. THP comprises 12 different MP topics: nine topics are delivered as didactic sessions and three as e-TBL sessions.

Design and participants

The study was conducted during the academic year 2021–2022. The MP strand of the THP module was chosen for intervention. All Year 3 medical students in Bahrain (n = 140) and half of year 3 in Dublin (n = 180) were invited to participate in the study. Although e-TBL was a mandatory curriculum component, the data from this study were used only from students’ contributions, which permitted us to use it for research purposes.

Ethical considerations

This research was approved by the participating institution Research Ethics Committee (REC202108006) at both locations.

Intervention

Using a sociocultural theoretical lens of adult learning theory, which considers interaction and learner-centeredness at the heart of the learning process, we based our e-TBL approach on ‘significant learning. ’ We integrated all the core domains of the participating institution model of MP while envisaging three e-TBL sessions in terms of context and ‘situational factors. ’ We pitched three e-TBL sessions on the MP during this module, as shown in .

Table 1. E-TBL workshop titles, learning objectives and case scenario themes.

We adopted a 4-step e-TBL strategy to design these sessions as a condensed version of standard TBL. We modified the e-TBL design used by Smeby et al., who employed a 3-step e-TBL in teaching undergraduate neuroradiology courses [Citation14]. All three e-TBL sessions were delivered face-to-face in Dublin (as COVID-19 restrictions were lifted) and online in Bahrain (as restrictions had not been removed).A stepwise schema of e-TBL is shown in .

TBL- Team Based Learning, VLE – Virtual Learning Environment, IRAT – Individual Readiness Assurance Test, VSAQs – Very Short Answers Questions

Step I – One week before the e-TBL session, a set of pre-reading materials, pre-recorded lectures, and PowerPoint slides were posted to all year 3 students in our virtual learning environment (Moodle™). Students were also briefed about e-TBL by providing guidance and instructional videos posted on VLE Moodle.

Step II: There was a brief introduction at the start of the session, followed by a Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) Moodle-integrated individual readiness assurance test IRAT (10 min) comprising concise answer questions (VSAQ). VSAQs are a unique set of questions that help learners follow authentic clinical reasoning strategies. At the same time, VSAQs can conveniently evaluate the clinical and ethical reasoning skills of learners of MP [Citation32]. An example of a VSAQ is shown in Box 1.

VSAQ:

During the clerkship, as a part of bedside teaching, you and a fellow student witness the doctor speaking harshly to a patient and exposing his intimate areas in public during physical examination and appearing to cause him pain and distress leading to the patient becoming tearful.

You and your fellow student consider what to do.

Keeping participating institution Medical Professionalism model in mind, mention the relevant professional issues and problems?

The VSAQs were developed by a working group of subject experts in MP via repeated deliberations and reaching a consensus after multiple revisions. Essentially, the VSAQs contained a clinical vignette followed by a lead-in question, and the students were instructed to provide their own free-text answers. The students’ answers were marked against assessors’ pre-approved answers. Any answers that did not match the pre-approved options were reviewed retrospectively to determine whether they could be added to the future lists of approved answers. The answers to the VSAQs were revealed to the students at the end of Step III.

Step III: Students were divided into teams of 10: small groups (campus A) and virtual breakout rooms (Campus B) using Blackboard Collaborate. An expert faculty member simultaneously facilitated team discussions for to 4–5 teams each. Team discussions enhanced students’ prior knowledge and helped establish their understanding. All teams simultaneously discussed the same significant MP scenarios using a structured approach [Citation33]. The same working group of experts developed the clinical scenarios for this step. A detailed facilitator guide and toolkit were provided to all facilitators, who also provided training sessions for these activities.

All online and in-person team discussions were documented and saved on team-specific electronic flipcharts (Padlets), providing a rich repository of discussions. The students’ contributions were anonymized using Padlets™. All Padlets™were saved, and later, the contributions from the consented teams were subjected to free-text thematic analysis of the scenarios discussed during the small group and breakout sessions.

Step IV – Finally, the teams reconvened back into one large group. A spokesperson from each team presented the group discussion summary and plausible solutions. The leading facilitator of e-TBL wrapped up the session with lessons learned and key-take-home messages.

Data analysis

All Padlets were reviewed, uniformly formatted into Excel sheets, and saved as two different files for the Bahrain and Dublin students. The organized and formatted data were analysed using Braun and Clark’s 6-step thematic analysis, which yielded a rich, detailed, and complex data account [Citation34]. Thematic analysis is a widely used method for analysing qualitative data that involves identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) systematically within the data [Citation35]. We used an inductive-driven thematic analysis approach, which is ‘data to theme to theory’ meaning we took an open-coding approach to looking at the data without any pre-existing framework in mind; instead, the focus of the analysis was prompted by our research question [Citation36].

Using an inductive approach, we first familiarized ourselves with the data by iteratively reading, highlighting, and taking notes. This led to the development of a coding framework (closely related to data) by segregating the data into small segments, which were later fed into the formation of themes by identifying patterns and instances of patterns that were compared repeatedly. Subsequently, the themes were reviewed, refined, and explained to best represent the dataset. To ensure the rigor and reliability of the thematic analysis, a constant cross-checking of the results with the data and multiple discussions between the SSG, SYG, FRD, and BM were carried out. Considering that thematic analysis is iterative and flexible, we adopted and modified the steps to suit the specific needs and characteristics of the data and research question.

Results

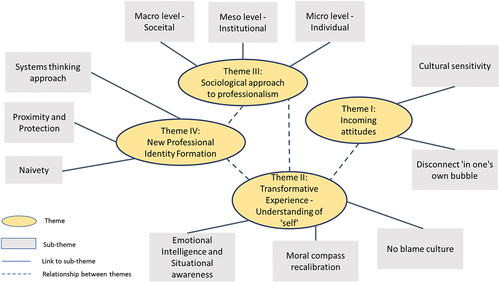

Our thematic analysis of data from 17 Padlets by 172 students (101 from Bahrain and 71 from Dublin) yielded four themes that threaded prominently throughout the data collection. The first main theme ‘incoming professional attitudes’ of the learner, which we define as signifying a disconnect (in one’s bubble) where the data reflected a detached individual from the experiences and perspectives of others. The second theme that emerged was ‘transformative experience,’” which represents a shift in an individual’s understanding, perspectives, values, or beliefs, resulting in a significant change in students’ behaviours and attitudes, manifested through their responses to case discussions. The third theme emerged as an improved understanding of professionalism through segregation of responsibilities at the micro (individual), meso (institution), and macro (society) levels. Finally, the fourth theme showed the germination of a new professional identity, reflected as individuals developing a new sense of self and purpose in their professional lives ().

Theme 1: incoming attitudes

Most responses in the first e-TBL sessions showed a moderate understanding of MP, with some disconnected from others’ perspectives and experiences. Cultural sensitivity was also reflected in most of the statements. Cultural sensitivity has become increasingly important as patient populations have become increasingly diverse. Culture strongly impacts patients’ health, illness, and compliance perceptions. Culturally sensitive healthcare providers are better equipped to address these differences and provide higher-quality and more equitable care to all patients [Citation37,Citation38].

Comfort to the patient – Patient compliance is increased when they believe in their treatment. When there is collaboration between the doctor and patient, more positive outcomes can be achieved. Dublin e-TBL1

To promote cultural sensitivity in healthcare, students received training in cultural competence, engaged in ongoing education and self-reflection, and made an effort to understand and respect each patient’s unique cultural beliefs and practices.

Self-awareness – The doctor should understand her stereotypes and biases, and in the future make an effort to understand the unique situation of each family. Dublin e-TBL1

Understanding cultural paradigms reduces health disparities and improves overall health outcomes for patients from diverse cultural backgrounds.

awareness of high context society communication and saving face or tendency to nod along and avoid ‘conflict’ (questioning) Bahrain e-TBL1

However, another incoming attitude, ‘Being in one’s own bubble,’’ was reflected in the statements, which referred to the preconceived beliefs, opinions, and perspectives that students were bringing with them from previous years’ professional didactic teaching experiences. Being in one’s bubble clearly reflected a lack of empathy, understanding, and connection when dealing with patients from a different culture.

why is he not open to the considerations does he understand the severity of type 1 diabetes and ensuring proper management ask about his thoughts and what his concerns are. perhaps he isn’t open to suggestions because of these concerns Bahrain e-TBL1

Hard to convince any information further due to the nature of the father. Also, high context culture is a significant aspect of consideration where information is given indirectly. So effort should be made from the side of the HCP in dealing with such a situation Dublin e-TBL1

Some student responses explained the prevailing paternalistic attitude, which significantly impacted how students perceived and responded to new situations and experiences.

acceptance the treatment plan + trust the physician Bahrain e-TBL1

Theme 2: transformative experience – understanding of ‘self’

A transformative experience is a significant event or series of events that leads to meaningful personal changes or growth [Citation39]. A shift in an individual’s understanding, perspective, values, or beliefs results in an important change in their behaviour, relationships, or overall life direction. We witnessed these transformations through discussions of the case scenarios, especially in the second round of e-TBL sessions. Exposure to new ideas or perspectives was perceived as a transformation driver, and e-TBL small-group discussions seemed to be a phenomenal factor in this context.

During the e-TBL discussions, understanding of ‘self’ and how its actions were reverberated to other colleagues was insightful.

I would reflect firstly on why my practices are wrong and begin to make changes such as valuing certain things differently and avoid going out to parties which conflict with work. Finally, apologize to all my colleagues. The load they had to bear is unfair. Bahrain e-TBL2

Realisation of my responsibility to actually carry out their responsibility as a doctor who inherently should be caring for their patients like their peers was doing (?) Dublin eTBL2

Get a chance to re-coup, start fresh and re-evaluate your priorities, so it does not happen again. Bahrain e-TBL2

Even though our students had little exposure to reflection, a reflective attitude was evident in the case discussions. It was heartening to note a sense of ‘putting oneself first for improvement’ in future healthcare professionals.

Reflection needed for self-development. Lesson learnt through reflection will help change future behaviour Dublin e-TBL2

Another important subtheme was an understanding of ‘no blame culture, a work environment in which individuals were not held responsible or punished for mistakes or failures. Instead, it focused on learning from mistakes, improving processes, and creating a culture of continuous improvement.

Structure is very important. The intern should be able to manage his time well enough to finish all his duties, however and downfall every once in a while is okay, and in that case, colleagues should be helpful and compassionate. Bahrain e-TBL 2

have supports available to recognize where further attention and mentorship might be required, and have supports that can appreciate the differences in others working styles/strengths/skills Dublin e-TBL 2 Case 2

Moral compass recalibration was the process of adjusting one’s ethical framework in response to new experiences, insights, or challenges [Citation40,Citation41]. This process can be triggered by various experiences, such as exposure to new cultures, perspectives, or information provided during e-TBL sessions.

Advocacy and Compassion – to ensure patient’s needs are met and resources are fairly distributed. Dublin e-TBL 2

try to establish an appropriate and approachable way of bringing any noticed shortcomings forth to the hospital’s management system. Bahrain e-TBL 2

During the e-TBL sessions, case discussions provided some insights into the students’ emotional intelligence and situational awareness qualities, which are thought to play a crucial role in the provision of high-quality care to patients.

Voice out my concerns to HR. Prompt them to carry out QI investigations. If ignored, carry out QI steps. Start with obtaining inputs from colleagues & initiating the PDSA cycle. Dublin eTBL2

Theme 3: sociological approach to professionalism

MP can be realized at the micro, meso, and macro levels. At the micro level, MP refers to an individual’s personal qualities and behaviours in the given settings. This included traits such as ethical behaviour, responsibility, competence, and commitment to continuous learning and improvement.

From a micro perspective students should not be afraid to advocate for their patients and to communicate any concerns to their seniors. Dublin e-TBL3

expecting doctors to act professionally especially in matters that directly affect the patient, to know that information on social media once it’s up it is forever there and one should be responsible while using it. Bahrain e-TBL3

At the meso level, MP refers to a particular profession or organization’s norms, values, and standards. This level of MP is often shaped by professional associations, regulatory bodies, and organizational standards.

make people of “lower” hierarchal positions feel comfortable to voice their inputs as they might notice things other staff members do not recognize Bahrain e-TBL3

Hospital system should create an environment where doctors are able to voice out their concern or complaints. They then would not opt to rant on social media Dublin eTBL3

Make anonymous suggestion box where employees from different specialties no matter how long they worked in the hospital can give anonymous suggestion. Like that we gave the value to the suggestion not to who gave it. Bahrain e-TBL2

QI is used by hospitals to optimize clinical care by reducing variability and reducing costs, to help meet regulatory requirements, and to enhance customer service quality. Dublin e-TBL2

At the macro level, MP entailed broader cultural, social, and political forces that shaped their meaning and understanding. This level of MP was influenced by broader social and economic trends as well as cultural and political ideologies.

raising public inquiry, an organized and proactive system to manage members of the society Dublin eTBL2

adopt general systems and guidelines recommended by the healthcare system, including guidelines, to raise the hospital’s conditions to national/international standards Bahrain e-TBL2

Theme 4: new professional identity formation

The theme of new professional identity formation followed the process of developing a new sense of self and purpose in professional lives. The process of new professional identity formation was challenging and involved exploring new roles, responsibilities, and values. Individuals needed to let go of old beliefs and behaviours and adopt new ways of thinking and acting professionally. We observed this gradual shift in beliefs between the first and last e-TBL case discussions in the form of systems thinking. However, the need for proximity and protection seemed obvious in some of the naïve responses during the case discussions.

During the analysis, we came upon a glimpse of the systems thinking approach [Citation42] from students who saw the world and its phenomena as interconnected and interdependent systems of elements.

As future doctors, never let our feelings and concerns affect our professional behavior. Our professional behaviour should be the influencer and not the opposite. Bahrain e-TBL3

View culture as an influence and not a determining factor of behaviour. Dublin e-TBL1

Based on the concept of continuous improvement, it essentially tells each of us that no man is perfect. We learn from our shortcomings be it a cleaner or a HCP. It encourages all health care team members to continuously question how they and their system are performing and whether performance can improve. Bahrain e-TBL2

In the patient centredness and cultural approach must be linked and avoid stereotyping at all cost to provide the best care management plan without causing any problems, such as misunderstanding and losing trust. Dublin e-TBL1

Proximity and protection [Citation43] play important roles in shaping human behavior and emotional well-being. By fostering close proximity and promoting protection, role modelling creates supportive social environments that enhance emotional well-being and resilience.

Positive leadership is important to implement and maintain change Bahrain e-TBL2

role models in workplace life is a journey of constantly learning and needing to improve, a positive attitude will show a positive example to colleagues hence you may indirectly become role models Dublin eTBL2

Communication, preparedness, and willingness to work are key to help make change at the workplace. Members of the staff are more likely than not also facing or noticing the issue. Collaborating with other members, departments and appropriate systems to make change will also help adopt a more collaborative and productive work ethic and relationship in the future Bahrain e-TBL2

During case discussions, we recorded some naivety among students when they single-handedly thought how they could influence ‘society.’ However, this thinking could play a role in shaping the world around them, and some of their actions may positively impact others; however, a paradigm shift might take time.

Bringing issue to the attention of the hospital management would result in improvements to the standard of care delivered to patients. Dublin e-TBL2

Don’t be afraid to raise concerns about issues with the system to superiors/administration, communicate the flaws you notice and how they can be improved to enhance patient care Bahrain e-TBL2

Discussion

Our qualitative study findings provide a deeper understanding of third-year participating institution undergraduate medical students regarding the topic of MP using the e-TBL strategy. The study showed students’ strong engagement and problem-solving skills, as evidenced by the generation of new themes and insights about MP. A host of interactive small-group discussions to solve MP-based scenarios in e-TBL format testifies to medical students’ readiness to work individually and in teams. A structured inductive thematic analysis generated four themes: incoming attitudes, transformative experience-understanding of ‘self,’ sociological approach to professionalism, and new identity formation. These themes were thoroughly analysed in the subsequent sections of the article to reveal their significance, relevance, and possible educational reforms in medical curricula.

The first e-TBL session focused on the cultural competence aspect, where students’ pre-existing understanding of MP and cultural sensitivity were reflected in their case discussions. In recent research, Swatsky deliberated on the best ways to teach cultural competency [Citation44]. The e-TBL strategy adopted in our study can be helpful, as educators can only devise best-fit methods once they secure pre-existing understanding and perceptions of the MP construct. In the same report, Swatsky proposed bringing inclusiveness and diversity into teaching the core principles of MP. Discussions and dialogues among students with intricate personal identities can lead to the development of shared understanding about the qualities of a ‘good doctor,’ which facilitates the process of socialization into communities of practices. In our work, e-TBL discussions provided a critical addendum where students mentioned the idea of self-awareness, which highlighted their ability to perform a critical analysis of their insights and to appreciate the cultures from different paradigms [Citation39]. Enhanced intercultural awareness increases learners’ knowledge of the world. It also helps to navigate complex issues such as dealing with stereotypes, helping to build relationships across cultures, easing adaptation to new societies or structures, and increasing empathy and tolerance for different ways of approaching the world of work [Citation45,Citation46].

Historically, participating institution works on the capital of diverse student populations, which was recently considered a necessary upgrade for the medical profession in the form of ‘educational dividends’ [Citation47]. This approach was conveniently utilized by adopting e-TBL in our pedagogical approach. We believe that such educational interventions can easily provide the pedagogical space necessary for professional identity formation. A recent study mentioned that identity is fragile, fissured, cracked, and referential, with an important element of co-construction by one’s inner self and social context [Citation48]. Hence, we witnessed an element of disconnect in the incoming attitudes, reflecting the conflicting stages of multiple identity acquisition where individuals experience internal conflicts or tensions between different aspects of their identity [Citation3]. The concept of multiple identities was important, as our third-year students transitioned from preclinical to clinical settings. In our study, we documented a few responses which could highlight how students dealt with the hierarchical nature of their multiple identities and still found a conflict between themselves and the contextual relevance of the medical profession [Citation3,Citation49].

In the second e-TBL session, several responses from the students highlighted the transformative moments in their professional identity development. The students’ responses were compassionate, ethical, and emotionally intelligent. Understanding the complexities of clinical practices and putting patient-centred care at heart, participants’ approach to raising concerns without shifting the blame on one element aligned with the change of ‘frame of reference’. According to transformative learning theory, the ‘frame of reference’ comprises of ‘habits of mind’ and point of view. Where ‘habits of mind’ (abstract, orienting, habitual ways of thinking, feeling, and acting) while ‘point of view’ (complex feelings, beliefs, judgments, and attitudes) sits at two opposite paradigms [Citation39]. Its established that ‘point of view’ is more accessible to awareness and is malleable to feedback from others compared to habits of mind which are durable and ingrained. In this context, the no-blame culture, shift in ethical practices, and situational awareness manifested as a change in point of view and as a transformative experience through deliberate discussions and communicative learning [Citation50]. During the thematic analysis, we recorded all such pragmatic changes in the form of inclusive, discriminatory, self-reflective, and integrative experiences of others. Such practices are important in healthcare industries, where a continuous learning approach, responding effectively to team members’ needs, and contextual relevance can safeguard patient safety.

Considering MP as a social contract, in our second and third e-TBL sessions, we implied a sociological approach to case analysis [Citation51]. We looked at the scenarios from the narrowest and most elementary layer of social behaviours micro; professionalism as the personal qualities and behaviours of individuals in the workplace). Meso; the interaction between two persons (professionalism as the norms, values, and standards of a particular profession or industry) to macro; a progressive extension of our perspective to social groups (professionalism as the broader cultural, social, and political forces that shape the meaning and understanding) [Citation52]. Boateng used this pluralist approach to locate and visualize the roles of micro and macro levels in influencing meso levels in the decision-making attitudes of the healthcare industry [Citation53]. Learning such an intersubjective understanding of social orders, which can give rise to complex patterns of social interaction, is essential for future doctors [Citation54].

Progressing from the first to the third e-TBL, we noticed an emerging new professional identity formation in our students. There was sufficient evidence that in the successful formation of a new professional identity, individuals needed to continuously self-reflect, seek out new perspectives, and build new relationships [Citation55]. Using the e-TBL strategy, we implemented a situated-learning approach that enhanced students’ clinical judgment by addressing the cognitive elements of MP using the participating institution model of professionalism. Students’ analysis of case scenarios reflects their sense of self’ and the purpose of professional life’ by understanding the interconnectedness of various components in the entire system [Citation56]. However, since professionalism is a life-long process, the need for revisiting role models, mentors, and collaboration has been highlighted [Citation57]. In a four-year longitudinal study, proximity and protection principles as apprenticeship models affirm professional identity formation in congruence with the principle of the social baseline theory [Citation43,Citation58]. In the same theme of professional identity formation, we noticed some naivety in the understanding of our medical students, which reflected a misconception about how one individual can influence society. This can be interpreted as an ‘idea of agency’ for the digitally native Gen-Z, which is in sharp contrast to the digitally immigrant Gen-X [Citation59]. Generic knowledge and awareness about the use of social media adds value to the emerging concept of professional competence in the digital realm [Citation60,Citation61].

Strengths and Limitations

Although the study used a small sample size, the process was well-planned and executed. The generated data were rich enough to provide a deeper understanding of the MP. The generalizability of the results cannot be claimed due to the content, context, participant’s unique nature, variability in facilitation skills, and lack of long-term follow-up.

Conclusion

This qualitative study reports on the use of e-TBL for teaching MP by employing pre-class activities, IRAT, group discussions, and feedback tailored to the newly developed THP module of participating institution. During e-TBL, interactive discussions to solve MP-based scenarios under trained faculty fostered a deeper understanding of students. The themes of incoming attitudes, transformative experience – understanding of ‘self, sociological approach to professionalism, and new professionalism identity formation can be potentially inculcated in the responsive medical curriculum for its better understanding in teaching and practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Guraya SY, Norman RI, Roff S. Exploring the climates of undergraduate professionalism in a Saudi and a UK medical school. Med Teach. 2016;38(6):630–11. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2016.1150987

- Ali A, Staunton M, Quinn A, et al. Exploring medical students’ perceptions of the challenges and benefits of volunteering in the intensive care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e055001. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055001

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, et al. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1446–1451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

- Goldie J. Integrating professionalism teaching into undergraduate medical education in the UK setting. Med Teach. 2008;30(5):513–527. doi: 10.1080/01421590801995225

- Guraya SY, Guraya SS, Almaramhy HH. The legacy of teaching medical professionalism for promoting professional practice: a systematic review. Biomed Pharm J. 2016;9(2):809–817. doi: 10.13005/bpj/1007

- Guraya SY, Guraya SS, Mahabbat NA, et al. The desired concept maps and goal setting for assessing professionalism in medicine. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(5):JE01. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/19917.7832

- Guraya SY, Sulaiman N, Guraya SS, et al. Understanding the climate of medical professionalism among university students; a multi-center study. Innovations Educ Teach Int. 2021;58(3):351–360. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2020.1751237

- Li H, Ding N, Zhang Y, et al. Assessing medical professionalism: a systematic review of instruments and their measurement properties. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177321

- Vygotsky LS, Cole M. Mind in society: development of higher psychological processes.Michael Cole C, Vera Jolm S, Sylvia S, Ellen S, editors. Harvard university press; 1978. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. p. 23–28.

- Taylor DC, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE guide no. 83. Med Teach. 2013;35(11):e1561–e72. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.828153

- Gryka R, Kiersma ME, Frame TR, et al. Comparison of student confidence and perceptions of biochemistry concepts using a team-based learning versus traditional lecture-based format. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2017;9(2):302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2016.11.020

- Fatmi M, Hartling L, Hillier T, et al. The effectiveness of team-based learning on learning outcomes in health professions education: BEME guide no. 30. Med Teach. 2013;35(12):e1608–e24. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.849802

- Smeby SS, Lillebo B, Slørdahl TS, et al. Express team-based learning (eTBL): a time-efficient TBL approach in neuroradiology. Acad Radiol. 2020;27(2):284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2019.04.022

- Liu S-N, Beaujean AA. The effectiveness of team-based learning on academic outcomes: A meta-analysis. Scholarship of teaching and learning in psychology. Scholarsh Teach Learn Psychol. 2017;3(1):1. doi: 10.1037/stl0000075

- Edmunds S, Brown G. Effective small group learning: AMEE guide no. 48. Med Teach. 2010;32(9):715–726. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.505454

- Burgess A, van Diggele C, Roberts C, et al. Team-based learning: design, facilitation and participation. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(2):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02287-y

- Haidet P, O’Malley KJ, Richards B. An initial experience with “team learning” in medical education. Acad Med. 2002;77(1):40–44. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200201000-00009

- Parmelee D, Michaelsen LK, Cook S, et al. Team-based learning: a practical guide: AMEE guide no. 65. Med Teach. 2012;34(5):e275–e87. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.651179

- Levine RE, Hudes PD. How to design and implement TBL. How-to guide for team-based learning. Springer International Publishing; 2021 Mar 29. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-62923-6_2

- Sharma A, Janke KK, Larson A, et al. Understanding the early effects of team-based learning on student accountability and engagement using a three session TBL pilot. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2017;9(5):802–807. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2017.05.024

- Vasan NS, DeFouw DO, Compton S. A survey of student perceptions of team‐based learning in anatomy curriculum: favorable views unrelated to grades. Anat Sci Educ. 2009;2(4):150–155. doi: 10.1002/ase.91

- Nieder GL, Parmelee DX, Stolfi A, et al. Team‐based learning in a medical gross anatomy and embryology course. Clin Anat. 2005;18(1):56–63. doi: 10.1002/ca.20040

- Chung E-K, Rhee J-A, Baik Y-H. The effect of team-based learning in medical ethics education. Med Teach. 2009;31(11):1013–1017. doi: 10.3109/01421590802590553

- Simon M. Team-based learning in medical ethics education: evaluation and preferences of students in Oman. J Med Educ. 2020;19(3). doi: 10.5812/jme.106280

- Burgess A, Matar E. Team-based learning (TBL): Theory, planning, practice, and implementation. In: Nestel, D, Reedy, G, McKenna, L, Gough S, editors. Clinical Education for the Health Professions: Theory and Practice. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. 1–29.

- Prasasti H, Susilaningsih E, Sulistyaningsih T. Development e-TBL to analyze critical thinking skills and problem solving in learning of substance and characteristics. J Innov Sci Educ. 2020;9(3):327–334. doi: 10.15294/jise.v9i1.36844

- Roossien L, Boerboom TBB, Spaai GWG, et al. Team-based learning (TBL): each phase matters! An empirical study to explore the importance of each phase of TBL. Med Teach. 2022;44(10):1125–1132. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2064736

- Parmelee DX, Michaelsen LK. Twelve tips for doing effective team-based learning (TBL). Med Teach. 2010;32(2):118–122. doi: 10.3109/01421590903548562

- Arievitch IM, Haenen JP. Connecting sociocultural theory and educational practice: galperin’s approach. Educ Psychol. 2005;40(3):155–165. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep4003_2

- Morgan MP, Thomas W, Rashid-Doubell F. Academic staff perspectives on delivering a shared undergraduate medical module on three transnational campuses: practical considerations and lessons learned. Med Teach. 2020;42(1):36–38. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1649380

- Sam AH, Westacott R, Gurnell M, et al. Comparing single-best-answer and very-short-answer questions for the assessment of applied medical knowledge in 20 UK medical schools: cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e032550. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032550

- Haidet P, Levine RE, Parmelee DX, et al. Perspective: guidelines for reporting team-based learning activities in the medical and health sciences education literature. Acad Med. 2012;87(3):292–299. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318244759e

- Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):328–352. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Holmqvist K, Frisén A. “I bet they aren’t that perfect in reality:” appearance ideals viewed from the perspective of adolescents with a positive body image. Body Image. 2012;9(3):388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.03.007

- Berbyuk Lindström N Intercultural communication in health care. Non-Swedish physicians in Sweden. rapport nr: gothenburg monographs in linguistics 36. 2008.

- Seeleman C, Essink-Bot M-L, Stronks K, et al. How should health service organizations respond to diversity? A content analysis of six approaches. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1159-7

- Mezirow J. Transformative learning: theory to practice. New directions for adult and continuing education. New Dir Adult Contin Educ. 1997;1997(74):5–12. doi: 10.1002/ace.7401

- Johnstone M-J. Setting nursing’s moral compass. Aust Nurs Midwifery J. 2017;25(1):16.

- Moore C, Gino F. Ethically adrift: how others pull our moral compass from true North, and how we can fix it. Res Organizational Behav. 2013;33:53–77. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2013.08.001

- Leischow SJ, Best A, Trochim WM, et al. Systems thinking to improve the public’s health. Am J Preventive Med. 2008;35(2):S196–S203. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.014

- Beckes L, Coan JA. Social baseline theory: the role of social proximity in emotion and economy of action. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2011;5(12):976–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00400.x

- Sawatsky AP, Beckman TJ, Hafferty FW. Cultural competency, professional identity formation and transformative learning. Med Educ. 2017;51(5):462–464. doi: 10.1111/medu.13316

- Deardorff DK. Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. J Stud Int Educ. 2006;10(3):241–266. doi: 10.1177/1028315306287002

- Fantini AE. Assessing intercultural competence. The SAGE Handbook Of Intercultural Competence. 2009;456:476.

- Nivet MA. Commentary: diversity 3.0: A necessary systems upgrade. Acad Med. 2011;86(12):1487–1489. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182351f79

- Brown AD. Identities in and around organizations: towards an identity work perspective. Human Relations. 2022;75(7):1205–1237. doi: 10.1177/0018726721993910

- Monrouxe LV. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Med Educ. 2010;44(1):40–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03440.x

- Sjølie E, Francisco S, Langelotz L. Communicative learning spaces and learning to become a teacher. Pedagogy Culture Soc. 2019;27(3):365–382. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2018.1500392

- Serpa S, Ferreira CM. Micro, meso and macro levels of social analysis. Int’l J Soc Sci Stud. 2019;7(3):120. doi: 10.11114/ijsss.v7i3.4223

- Hartmann E. Violence: constructing an emerging field of sociology. Int J Confl Violence (IJCV). 2017;11:a623–a.

- Boateng W. A sociological overview of knowledge management in macro level health care decision-making. J Sociol Res. 2013;4(2):135–146. doi: 10.5296/jsr.v4i2.3165

- Kurawa SS. Social order in sociology: its reality and elusiveness. Sociology Mind. 2012;2(1):34. doi: 10.4236/sm.2012.21004

- Crigger N, Godfrey N. From the inside out: A new approach to teaching professional identity formation and professional ethics. J Prof Nurs. 2014;30(5):376–382. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.03.004

- Healey RA. Holism and nonseparability. J Philos. 1991;88(8):393–421. doi: 10.2307/2026702

- Benner P. Educating nurses: a call for radical transformation-how far have we come? J Nurs Educ.2012;51(4): 183–4 .

- Boudreau JD, Macdonald ME, Steinert Y. Affirming professional identities through an apprenticeship: insights from a four-year longitudinal case study. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1038–1045. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000293

- Berkup SB. Working with generations X and Y in generation Z period: management of different generations in business life. Mediterr J Soc Sci. 2014;5(19):218. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n19p218

- Guraya SY, Almaramhy H, Al-Qahtani MF, et al. Measuring the extent and nature of use of Social Networking Sites in Medical Education (SNSME) by university students: results of a multi-center study. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1505400. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1505400

- Guraya SS, Guraya SY, Yusoff MSB. Preserving professional identities, behaviors, and values in digital professionalism using social networking sites; a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02802-9