Abstract

Background

By examining the health needs of the general population and utilising the potential of digitalisation as a driving force, new internet-based services need to be developed in occupational therapy. However, existing guidelines for the development of complex interventions provide scant information on how to develop internet-based interventions.

Aim

The aim of this paper is to share experiences and illustrate important key actions and new perspectives to consider during the innovation process of developing and designing an internet-based occupational therapy intervention.

Method and Materials

International guidelines for intervention development was reviewed to add important perspectives in the innovation process.

Results

The illustration focuses on five key actions in the development phase to highlight new perspectives and questions important to consider when designing new internet-based occupational therapy interventions.

Conclusion

The new perspectives can complement existing guidelines to enhance the development of more effective and sustainable internet-based interventions.

Significance

The illustration provided has potential to improve the sustainability in innovation processes of new internet-based occupational therapy interventions.

Introduction

The digital transformation and societal challenges related to peoples’ health place high demands on innovation of new services in occupational therapy (OT) [Citation1–3]. Together with individuals having to take a greater responsibility for their health, there is a need for rehabilitation and prevention opportunities to adapt to these challenges, including how such interventions are delivered [Citation4–6]. Interventions also need to be more accessible and distributed in a way that promotes equal health for all citizens [Citation4–6]. In this, e-health services delivered through the Internet and associated technologies are a way forward. This is also in line with the core values of welfare innovations [Citation7,Citation8] emphasising increased productivity (e.g. providing more OT services to the same or at a reduced cost), improved service (e.g. more individually tailored OT service), and improved outcomes (e.g. sustainable health, maintaining an active life while living with a life-long chronic condition). However, newly developed innovations in OT services that take advantage of digitalisation possibilities, including products or services such as internet-based interventions, are scarce [Citation9–11].

New OT interventions (e.g. [Citation12,Citation13]) are increasingly being developed based on the MRC guidelines [Citation14,Citation15] that describe how complex interventions are best developed and evaluated. Complex interventions often have a number of interacting components that influence the process and outcome, which require new behaviours from both the receivers and those who deliver the intervention [Citation14,Citation15]. The innovation process can become even more complex if an already existing intervention in a traditional format is adapted to digital modes for delivery. That is, they have to match users’ (clients and professionals) needs and conditions, especially if clients and professionals in the health care organisation have different digital competences. Furthermore, an innovation process often includes the development of a new intervention that includes the use of a new digital solution. Taken together, we argue that those who design internet-based interventions need to have knowledge of the digital competence [Citation16] among different groups of users, be aware of the principles and theories suitable for distance learning, employ a user-centred design [Citation17], and engage in cocreation or coproduction [Citation18–20] of digital solutions. To our knowledge, existing guidelines does not clearly outline and merge together the variety of knowledge needed to scientifically develop and evaluate complex internet-based interventions in OT. Therefore, we set out to illuminate how a sustainable innovation process can evolve based on our experiences while creating the internet-based OT intervention ‘Strategies for Empowering Activities in Everyday life (SEE) version 1.0’ [Citation21]. The ambition is to share experiences and provide an opportunity to learn more about key actions and perspectives that are important to consider for sustainability when a new, digitalised intervention is developed.

The aim of this paper is to share experiences and illustrate important key actions and new perspectives to consider during the innovation process of developing and designing an internet-based OT intervention.

Key actions in an innovation process of an internet-based OT intervention

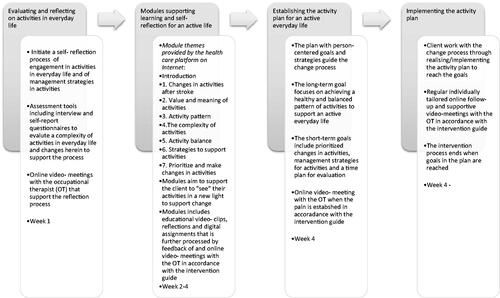

In this paper, we will outline and illustrate five key actions () that we consider to be important in the early stages of the development and design of a new internet-based OT intervention, SEE [Citation21]. During the innovation process, we were inspired by the steps outlined in the MRC model [Citation14,Citation15] as well as other recent international guidelines for intervention development [Citation19,Citation22]. Consequently, the five chosen key actions derive from existing guidelines (that is referred to in the description each key action). We will, also using SEE as a showcase, highlight new perspectives important to consider during the process by providing questions () that can be used during the key actions to guide future innovation processes of internet-based interventions.

Table 1. Overview of key actions, new perspectives and questions suggested to inform the innovation process of internet-based interventions in occupational therapy.

Operationalising the idea of a sustainable internet-based OT intervention

The first key action is to operationalise the idea of a sustainable internet-based OT intervention. In other commonly used guidelines, this key action is often limited to problem identification or understanding [Citation19,Citation22]. When operationalising the idea of SEE [Citation21], we (the researchers) considered the driving forces for innovations such as citizens’ needs and growing expectations, new technology and sustainability, as well as the core values of welfare innovation, including striving to improve productivity, services and outcomes [Citation7,Citation8,Citation18] when examining current evidence.

One of the driving forces for SEE [Citation21] was the need for new interventions, a need based on the rights of people with disabilities to engage in activities and live an active life in society on equal terms [Citation23]. This is a societal challenge since a large number of people worldwide live with a neurological disorder and experience activity limitations that can compromise their possibility of living an active life [Citation24,Citation25]. Neurological rehabilitation in the early phases of, for instance, a stroke, is well developed but focuses on restoring function rather than on needs related to living an active everyday life or facilitating the process of change people go through to adapt to a changed capacity and life condition [Citation26–29]. Moreover, access to neurological rehabilitation and prevention is limited and not equally distributed in Sweden [Citation30,Citation31]. Consequently, there is a need for new rehabilitation and prevention interventions that support people when they try to adopt sustainable strategies to regain and maintain an active everyday life. Internet-based services and interventions have been described as suitable alternatives with the potential to improve access to rehabilitation and enhance the provision of individually tailored interventions [Citation9,Citation32–35].

An early decision when operationalising the idea of SEE [Citation21] was to target the change process for an active life rather than taking a starting point based on specific diseases or injuries. Another important aspect was to utilise a person-centred approach where the design of the intervention had to allow for flexibility in adding content associated with specific needs related to an active life. Despite being an individual intervention, its delivery format also had to be flexible enough to be changed to a group format or a team-based intervention later on. Consequently, the intervention was designed to match many clients’ needs, although scientific testing and evaluation were planned for specific diagnostic groups. Designing a general intervention that matches the health needs of many clients may save development resources as well as OT resources when they do not need to access different treatment programmes on different platforms for various health conditions.

Another important early decision was to consider how the content and the outcome would provide tools for sustainable changes in health. Hence, the goal of SEE [Citation21] is to support a balanced pattern of various daily activities, at different places, and together with other people to promote an active life and health. Thus, the content was designed to empower clients to ‘see’ their activities in a new light and develop management strategies in activities. The goal was also to empower clients to take on an active role to prevent and overcome problems and challenges in everyday life that were sustainable over time.

Finally, to ensure the sustainability of the intervention, we examined the context and the prerequisites for internet-based interventions in the specific settings where it was planned to be used. The preliminary draft intervention was discussed with professionals (occupational therapists, managers at different levels in the organisation and health platform administrators). They confirmed and agreed on the relevance of the intervention and mutually agreed to deliver SEE through the ‘support and treatment platform’ within the Swedish 1177 health care guide [Citation36], a secure platform that is accessible in all regions in Sweden and used to a varied extent by both citizens and professionals. Utilising an already existing platform has the potential to facilitate delivery and provide for an equal distribution of the intervention across the country in the future, as well as to avoid problems and save resources.

In summary, starting with clients’ needs, the early decisions described above reflect how the driving forces and the core values of welfare innovations [Citation7,Citation8,Citation18] were considered in different ways during operationalisation. Based on these experiences, we suggest perspectives important to consider during the first key action ‘Operationalizing the idea’ in .

Designing the innovation process of developing an internet-based intervention

The second key action is to decide which approach, framework or model, or combination of these [Citation19], can guide the innovation process when developing and designing the internet-based intervention. When developing SEE [Citation21], we considered a variety of innovation models as well as frameworks or approaches for intervention development. Innovation models focussing on designing new products or services can emanate from fields outside health care, often with a focus on business development [Citation7,Citation37] but can be adapted to the context of health care [Citation7,Citation38]. The innovation processes in these models are not necessarily based on reviews of current scientific evidence but rather on experienced needs and relevance in the present context. However, health care interventions need to be based on evidence and developed and evaluated in an evidence-based way to provide evidence-based practice and sustainability [Citation15]. Models for intervention development [Citation19,Citation20,Citation22] can be seen as another kind of innovation model that focuses on a new service in terms of a whole intervention [Citation14,Citation15]. These models are scientifically based but do not necessarily provide the detailed guide and tools necessary to develop a digital solution, e.g. the web layout together with the users. There are also models focussing specifically on designing internet interventions [Citation39–42]. Even if these models are implemented within a scientific framework, they do not necessarily involve the scientific base needed to develop and evaluate a new intervention. Thus, it is important to make an informed decision on how to be guided by different models during the development phase of an internet-based intervention.

In developing SEE, we found it favourable to combine the MRC guidelines for complex interventions [Citation14,Citation15] with other, more comprehensive guidelines that describe the development phase of interventions [Citation19,Citation22]. These guidelines [Citation14,Citation15,Citation19,Citation22] inspired an iterative innovation process for developing and designing interventions on scientific grounds involving several actions. The guidelines [Citation19,Citation22] support a sustainable innovation process based on research and theories, including close collaborations with receivers and deliverers. As these guidelines included different and complementary key actions for the development phase, we considered it as a strength to use both to ensure that important actions not were overlooked. Thus, the feasibility of the intervention as well as the sustainability of the long-term health outcome was optimised. In applying these guidelines [Citation19], researchers are encouraged to be open to whatever actions are relevant rather than following cycles with predetermined actions. Additionally, the guidelines explain how to scientifically scale up an intervention [Citation14,Citation15] that ultimately enables an evidence-based intervention programme and implementation. Individual dialogues and discussion groups with managers and occupational therapists at the clinic revealed that an important vision for the clinic was to digitalise and improve rehabilitation in a way that ensured evidence-based practice. Thus, the relevance of selecting guidelines that enabled this was necessary. Moreover, we found components and tools in the other models for innovation and internet design as valuable resources in other key actions of the innovation process. Based on these experiences, we suggest important perspectives to be considered during the key action ‘designing the innovation process’ in .

Identifying and developing evidence underpinning an internet-based intervention

The third key action is to review and synthesise evidence and, if needed, conduct scientific research to complement the evidence base that supports the design and delivery of the intervention [Citation14,Citation19,Citation22]. When we identified the evidence to develop SEE [Citation21], we considered the core values of innovations, i.e. increased productivity, improved services and outcomes [Citation7,Citation8]. During this process, we reviewed research on clients’ needs and whether existing interventions match these needs (i.e. evidence foremost related to the innovation core value of improved services and outcome). Research on change processes was reviewed to identify therapeutic components important to achieve a change (i.e. evidence foremost related to the innovation core value of improved outcome). Additionally, we reviewed models of internet-based interventions and the evidence of the effectiveness of internet-based interventions in relation to users’ experiences and abilities (i.e. evidence foremost related to the innovation core values of increased productivity and improved service). Consequently, to design this new intervention we needed to review various evidence. This review identified knowledge gaps of peoples’ activities in everyday life that needed to be filled in to inform the content of the OT intervention. Also, knowledge available to inform the web-design and the delivery of the internet- based intervention. These reviews are described more in detail below.

The review of research evidence, based on the aim of the SEE [Citation21], showed a knowledge gap regarding peoples’ experiences of engagement in activities in places outside home, occupational balance, occupational values and self- initiated management strategies in activities. This knowledge was considered as important to improve the service and the outcome (core values of innovation) of the new intervention. Therefore, empirical research on clients’ experiences and a meta-synthesis were conducted to provide a more complete evidence base underpinning SEE. From the synthesis of the present and new evidence (e.g. [Citation25–28,Citation43–52]), it became evident that SEE needs to build on a more complex understanding of activities in everyday life than are commonly applied in current rehabilitation c.f., [Citation44,Citation45,Citation52]. Usually, activities are considered in isolation from each other or from an independence perspective. Our synthesis showed that it was important that the content of the intervention acknowledged the whole pattern of activities to find a sustainable level of engagement in activities in relation to a changed capacity and life situation. The evidence also showed the importance of and the challenge of taking on an active role in developing self-initiated strategies to manage changes in activities in everyday life or to prevent problems from arising, e.g. [Citation44,Citation45,Citation53–56]. In the meta-synthesis [Citation56], a large number of self- initiated management strategies were identified that could be included as therapeutic components in the intervention. Our experiences show the importance of identifying unknown or overlooked perspectives important to the content of the intervention and how they can provide an improved service and outcome. Based on the experiences of SEE, we suggest that during the key action ‘Identifying and developing evidence’, it is important to consider the perspectives in .

To underpin the modelling of the web design and delivery of SEE [Citation21], additional research evidence was sought to complement models for designing internet interventions [Citation39–42]. The evidence of internet-based interventions focussing on active everyday life for people with neurological conditions is limited [Citation9,Citation10,Citation32,Citation57,Citation58]. Thus, evidence was also sought related to internet-based interventions in general to identify important aspects such as feasibility, adherence and effectiveness, e.g. [Citation59–62]. Furthermore, evidence of target group access to and the ability to use everyday technology such mobile phones, tablets and computers as well as services connected to these was sought, e.g. [Citation50,Citation63]. Our experiences show how evidence related the design, delivery and usability of interventions on the Internet are important to improve service and outcome as well as productivity (all being core values of innovation). Based on the experiences of SEE, we suggest perspectives important to consider during the key action ‘Identifying and developing evidence’ in .

Articulating programme theory

The fourth key action is to form programme theory that articulates and includes all knowledge needed, i.e. the crucial therapeutic components that make the intervention work as intended [Citation14,Citation19,Citation22,Citation64]. Based on the intention to develop an intervention delivered by the internet [Citation21], we found it necessary to consider knowledge that would enable effective delivery in this format. This knowledge was needed to provide for the modelling of the therapeutic components, i.e. the mechanism of change that makes the internet-based intervention work. In this process, we also found it important to again consider the three core values of welfare innovations, i.e. striving to improve productivity, services and outcomes [Citation7,Citation8], to ensure a sustainable intervention.

An overview of examples of questions asked to identify the various components in the program theory of SEE and their role in making the intervention work as intended is presented in . Based on the empirical research forming SEE (third key action), a review identified occupational therapy theories of the complexity of engagement in activities in everyday life [Citation65–68]. Together with theoretical perspectives and principles of person-centeredness [Citation69–72], the foundation of the intervention was formed, including each unique client’s situation and needs, with participation, sharing and transparency as important elements. The process of self-management [Citation29,Citation33,Citation73–79] added knowledge of the importance of the clients’ active role when adopting strategies and implementing these strategies into their everyday life. Perspectives on motivation [Citation80–82] were also identified and they play an important role during the intervention process as well as for improving the outcome where professionals can use the tool of motivation interviewing. Rehabilitation methodology [Citation83] is also a component of the programme, as it contains principles for how to actively involve the client when the plan for their change process is established. As the programme is internet-based, pedagogical principles, i.e. flipped classroom [Citation84–86] techniques suitable for distance learning and having the potential to support self-regulated learning, were integrated into the programme. That is, new knowledge is mediated through short videos prior to meetings with the OT. This leaves more time for processing the content of the films and supporting the client in taking on an active role in the change process instead of spending time on providing basic information. This suggests that the service provided, as in SEE, can be improved and has potential for improving cost-effectiveness. Based on the experiences of SEE, we suggest important perspectives to be considered during the key action ‘articulating programme theory’ in .

Table 2. The questions and components forming the program theory of SEE version 1.0.

Modelling the prototype

Based on a knowledge synthesis of the above key actions, the fifth key action concerned modelling the prototype, including the intervention process as well as its outcome measures [Citation19,Citation22]. This key action aimed to ensure and increase its applicability in practice. When modelling the prototype of SEE [Citation21], we found that it is important to design an intervention that realises the core values of welfare innovations [Citation7,Citation8] to ensure improved outcomes, services and productivity.

The modelling of SEE was conducted in several phases together with users, and resulted in three parts: i) the internet-based intervention, ii) an intervention guide, and iii) a professional internet-based educational programme [Citation21]. gives an overview of the intervention. The researchers designed an early prototype version of the internet-based intervention that included modelling the intervention, the intervention process and the outcomes [Citation19,Citation22]. Early on, it was decided that the internet-based intervention would comprise an initial pedagogical part that would be followed by an activity plan with individually tailored sessions. The pedagogical part of the intervention was designed as a number of flexible modules that are easy to change in the future. It was decided that only one module would include changes and needs in activities in everyday life related to the diagnostic group in focus (e.g., stroke, module 1) and that the other modules would be general to provide for flexibility. Each module focussed on different aspects of how a balanced pattern of various activities in everyday life can be obtained and it was designed in a flipped classroom manner. That is, each module was delivered the same way starting out with short videos and related client assignments, followed by regular feedback and online sessions with the occupational therapist. During this design process, preliminary prioritisation was made by the researchers regarding the content, modes of delivery, dose, intensity, and time duration to find an optimal balance between efforts, costs and outcomes [Citation15]. Furthermore, an activity plan for active everyday life was designed to guide the forthcoming change process when the modules were completed. The activity plan includes long- and short-term goals, strategies/actions, time frames and evaluation. In this innovation process, we also chose assessment tools that have the potential to i) identify and recruit suitable clients to the programme; ii) support clients in starting a process of change; and iii) evaluate the outcomes of participating in the programme. The process of modelling the internet-based intervention continued with several discussion groups [Citation87], with reference panels of occupational therapists and managers working at different clinics where the intervention was planned to be applied. When the content was finalised, the modelling of the intervention was conducted within the frames of the platform in the Swedish 1177 health care guide [Citation36], together with an administrator experienced in distance rehabilitation. During this process, it became evident that the occupational therapist needed an intervention guide and education about the programme theory to ensure that the intervention was implemented as intended. The educational programme for the occupational therapist also included knowledge of how to support a client in their process of change and how the national health care platform was used together with clients. The modelling of these parts (the intervention guide and education programme) was conducted through consultation, critical reading and workshops with the occupational therapists and with lecturers experienced in distance learning for occupational therapists. Currently, the SEE prototype (SEE version 1.0) () is being evaluated scientifically in a case study [Citation88] and feasibility studies [Citation15], involving clients, occupational therapists and managers at different organisation levels, with the aim of refining and finalising the modelling of the intervention. Based on the experiences of SEE, we suggest important perspectives to consider during the key action ‘modelling the prototype’ in .

Concluding remarks

This paper provides perspectives and questions important to add to the innovation process when internet-based interventions are designed and developed. These new perspectives can complement current intervention guidelines in the early stages of development. Consequently, the new perspectives should be used together with existing guidelines [Citation14,Citation15,Citation19,Citation22] that provide more knowledge about key actions, scientific methods and co-creation during development. Our ambition is to share experiences and provide an opportunity to learn more about key actions and new perspectives that are important to consider during the innovation process. Potentially, our experiences can contribute to the more effective and sustainable development of internet-based interventions. Nevertheless, our discussions are limited to our own experiences and the fact that the key actions undertaken are influenced by team competence as well as the context of the SEE intervention. Moreover, there is a need for flexibility when methods for collaboration are applied as the innovation process evolves. Readers are encouraged to consider the relevance of each key action, new perspective, question and methods in relation to their specific intervention idea and context as well as the team constitution.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful for the valuable contribution of the occupational therapists at Sunderby Hospital, Paramedicine and Rehabilitation Medicine, and at the Primary Health Care in Luleå and their managers, when the SEE intervention was developed. We thank Alexandra Olofsson PhD and OT, Luleå University of Technology (LTU), for her contribution in research that formed the basis of SEE. We also thank Monika Lindberg PhD student and OT, Maria Ranner, PhD and OT, and Carina Karlsson, MsC and OT, all at LTU, for support during the development of material related to the application of SEE. The authors are also grateful to Catharina Nordin, PhD and PT at Region Norrbotten, for support with applying and administrating SEE in the Swedish 1177 Health care guide.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Larsson-Lund M. The digital society: occupational therapists need to act proactively to meet the growing demands of digital competence. Br J OccupTher. 2018;81(12):733–735.

- Larsson-Lund M, Nyman A. Occupational challenges in a digital society: a discussion inspiring occupational therapy to cross thresholds and embrace possibilities. Scand J Occup Ther. 2019;27(8):550–553.

- Cason J. Telehealth: a rapidly developing service delivery model for occupational therapy. Int J Telerehabil. 2014;6(1):29–35.

- Nergårdh A, Andersson L, Eriksson J, et al. God och nära vård–En primärvårdsreform. [Good and close care - A primary care reform]. Stockholm: Social departementet; 2018.

- Strategi för genomförde av e-hälsa vision 2025. [Strategies for the implementation of The EHealth vision 2025]. Stockholm: Sveriges kommuner och regioner; [cited 2020 Dec 10]. Available from https://ehalsa2025.se/

- eHealth: digital health and care. European Comission; [cited 2020 Dec 10]. Available from https://ec.europa.eu/health/ehealth/home_

- Lubanski N, Klaesøe B, Johns L. Välfärdsinnovation. [Welfare innovation]. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2015.

- Bason C. Leading public design: discovering human-centred governance. Bristol: Policy Press; 2017.

- Zonneveld M, Patomella A-H, Asaba E, et al. The use of information and communication technology in healthcare to improve participation in everyday life: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2020; 42(23):3416–3423.

- Hung Kn G, Fong KN. Effects of telerehabilitation in occupational therapy practice: a systematic review. Hong Kong J Occup Ther. 2019;32(1):3–21.

- Iacono T, Stagg K, Pearce N, et al. A scoping review of Australian allied health research in ehealth. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):1–8.

- Kamwesiga JT, Eriksson GM, Tham K, et al. A feasibility study of a mobile phone supported family-centred ADL intervention, F@ ce™, after stroke in Uganda. Global Health. 2018;14(1):1–13.

- Patomella A-H, Guidetti S, Mälstam E, et al. Primary prevention of stroke: randomised controlled pilot trial protocol on engaging everyday activities promoting health. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e031984.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

- Richards DA, Hallberg IR. Complex interventions in health: an overview of research methods. New York (NY): Routledge; 2015.

- Vuorikari R, Punie Y, Gomez SC, et al. DigComp 2.0: the digital competence framework for citizens. Update phase 1: the conceptual reference model. Seville: European Commission, Joint Research Centre; 2016.

- Gulliksen J, Göransson B, Boivie I, et al. Key principles for user-centred systems design. Behav Info Tech. 2003;22(6):397–409.

- Bason C. Leading public sector innovation 2E: co-creating for a better society. Bristol: Policy Press; 2018.

- O'Cathain A, Croot L, Duncan E, et al. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e029954.

- Hawkins J, Madden K, Fletcher A, et al. Development of a framework for the co-production and prototyping of public health interventions. BMC Publ Health. 2017;17(1):689.

- Larsson-Lund M, Månsson Lexell E, Nyman A. Strategies for Empowering activities in Everyday life (SEE 1.0): study protocol for a feasibility study of an Internet-based occupational therapy intervention for people with stroke. Re-Submitted. 2021.

- Bleijenberg N, Janneke M, Trappenburg JC, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste by optimizing the development of complex interventions: enriching the development phase of the Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;79:86–93.

- United Nations. Convention on rights of people with disabilities (UNCRPD). Geneva: United Nations; 2008.

- Daniel K, Wolfe CD, Busch MA, et al. What are the social consequences of stroke for working-aged adults? A systematic review. Stroke. 2009;40(6):e431–e440.

- Audulv Å, Packer T, Versnel J. Identifying gaps in knowledge: a map of the qualitative literature concerning life with a neurological condition. Chronic Illn. 2014;10(3):192–243.

- Ellis-Hill C, Payne S, Ward C. Using stroke to explore the Life Thread Model: an alternative approach to understanding rehabilitation following an acquired disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(2):150–159.

- Robison J, Wiles R, Ellis-Hill C, et al. Resuming previously valued activities post-stroke: who or what helps? Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(19):1555–1566.

- Lund A, Mangset M, Wyller TB, et al. Occupational transaction after stroke constructed as threat and balance. J Occup Sci. 2015;22(2):146–159.

- Warner G, Packer TL, Kervin E, et al. A systematic review examining whether community-based self-management programs for older adults with chronic conditions actively engage participants and teach them patient-oriented self-management strategies. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(12):2162–2182.

- Socialstyrelsen. Vård vid multipel skleros och Parkinsons sjukdom. Nationella riktlinjer– Utvärdering. Sammanfattning med förbättringsområden. [Care for multiple sclerosis and parkinson disease. National guidelines- evalutation. Summary and areas of improvement]. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2016.

- Socialstyrelsen. Utvärdering av vård vid stroke – Huvudrapport med förbättringsområden Nationella riktlinjer – Utvärdering. [Evalutation of the care for stroke. Main report. National guidelines- evalutation]. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2018.

- Amatya B, Galea M, Kesselring J, et al. Effectiveness of telerehabilitation interventions in persons with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4(4):358–369.

- Whitehead L, Seaton P. The effectiveness of self-management mobile phone and tablet apps in long-term condition management: a systematic review. J Med Int Res. 2016;18(5):e97.

- Wildevuur SE, Simonse LW. Information and communication technology-enabled person-centered care for the ‘big five’ chronic conditions: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(3):e77.

- Johansson T, Wild C. Telerehabilitation in stroke care-a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17(1):1–6.

- Vårdguiden 1177. [The Swedish 1177 Health Care Guide]. Stockholm: Sveriges Regioner; [cited 2020 Dec 7]. Available from https://www.1177.se/

- Bergvall-Kareborn B, Stahlbrost A. Living Lab: an open and citizen-centric approach for innovation. IJIRD. 2009;1(4):356–370.

- Innovationsguiden. Användardriven innovation [Internet]. [The innovation guide, user-driven innovation]. Stockholm: Sveriges Kommuner och regioner; [cited 2020 Dec 7]. Available from www.innovationsguiden.se

- Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Cox DJ, et al. A behavior change model for internet interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(1):18–27.

- Floryan MR, Ritterband LM, Chow PI. Principles of gamification for Internet interventions. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(6):1131–1138.

- Hilgart MM, Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, et al. Using instructional design process to improve design and development of Internet interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(3):e89.

- Short C, Rebar A, Plotnikoff R, et al. Designing engaging online behaviour change interventions: a proposed model of user engagement. Europ Health Psychologist. 2015; 17(1):32–38.

- Kassberg A-C, Nyman A, Larsson Lund M. Perceived occupational balance in people with stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;43(4):1–6.

- Olofsson A, Larsson Lund M, Nyman A. Everyday activities outside the home are a struggle: narratives from two persons with acquired brain injury. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;27(3):194–203.

- Olofsson A, Nyman A, Larsson Lund M. Engagement in occupations outside home - experiences of people with acquired brain injury. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80(8):486–493.

- Lexell EM, Iwarsson S, Lexell J. The complexity of daily occupations in multiple sclerosis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2006;13(4):241–248.

- Lexell EM, Lund ML, Iwarsson S. Constantly changing lives: experiences of people with multiple sclerosis. Am J Occup Ther. 2009;63(6):772–781.

- Risser R, Lexell E, Bell D, et al. Use of local public transport among people with cognitive impairments–a literature review. Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav. 2015;29:83–97.

- Olofsson A, Nyman A, Kassberg AC, et al. Places visited for activities outside the home after stroke: relationship with the severity of disability. Br J Occup Ther. 2020;83(6):405–412.

- Malinowsky C, Larsson-Lund M. The match between everyday technology in public space and the ability of working-age people with acquired brain injury to use it. Br J Occup Ther. 2016;79(1):26–34.

- Eriksson G, Tham K, Borg J. Occupational gaps in everyday life 1–4 years after acquired brain injury. J Rehabil Med. 2006;38(3):159–165.

- Nyman A, Kassberg A-C, Lund ML. Perceived occupational value in people with acquired brain injury. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;28(5):391–398.

- Haggstrom A, Lund ML. The complexity of participation in daily life: a qualitative study of the experiences of persons with acquired brain injury. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(2):89–95.

- Larsson Lund M, Lövgren Engström A-L, Lexell J. Response actions to difficulties in using everyday technology after acquired brain injury. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19(2):164–175.

- Kassberg A-C, Prellwitz M, Larsson Lund M. The challenges of everyday technology in the workplace for persons with acquired brain injury. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20(4):272–281.

- Nygård L, Ryd C, Astell A, et al. Self-initiated management approaches and strategies in everyday occupations used by people with cognitive impairment; 2020.

- Chen J, Jin W, Zhang X-X, et al. Telerehabilitation approaches for stroke patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(12):2660–2668.

- Khan F, Amatya B, Kesselring J, et al. Telerehabilitation for persons with multiple sclerosis. A Cochrane review. Europ J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51(3):311–325.

- Webb T, Joseph J, Yardley L, et al. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(1):e4.

- Kelders SM, Kok RN, Ossebaard HC, et al. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(6):e152.

- Brouwer W, Kroeze W, Crutzen R, et al. Which intervention characteristics are related to more exposure to internet-delivered healthy lifestyle promotion interventions? A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1):e2.

- Schubart JR, Stuckey HL, Ganeshamoorthy A, et al. Chronic health conditions and internet behavioral interventions: a review of factors to enhance user engagement. Comput Inform Nurs. 2011;29(2):81–92.

- Kottorp A, Malinowsky C, Larsson-Lund M, et al. Gender and diagnostic impact on everyday technology use: a differential item functioning (DIF) analysis of the Everyday Technology Use Questionnaire (ETUQ). Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(22):2688–2694.

- Mills T, Lawton R, Sheard L. Advancing complexity science in healthcare research: the logic of logic models. BMC Med Res Method. 2019;19(1):1–11.

- Eklund M, Orban K, Argentzell E, et al. The linkage between patterns of daily occupations and occupational balance: applications within occupational science and occupational therapy practice. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24(1):41–56.

- Erlandsson L-K, Persson C. Valmo-modellen. Arbetsterapi för hälsa genom görande. [The Valmo- model. Occupational therapy for health through doing]. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2020.

- Eklund M, Gunnarsson B, Hultqvist J. Aktivitet och relation. [Occupation and relation]. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2020.

- Dickie V, Cutchin MP, Humphry R. Occupation as transactional experience: a critique of individualism in occupational science. J Occupt Sci. 2006;13(1):83–93.

- Leplege A, Gzil F, Cammelli M, et al. Person-centredness: conceptual and historical perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(20–21):1555–1565.

- Rogers CR. Significant aspects of client-centered therapy. Am Psychol. 1946;1(10):415–422.

- Ranner M, Guidetti S, von Koch L, et al. Experiences of participating in a client-centred ADL intervention after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(25):3025–3033.

- Ranner M, von Koch L, Guidetti S, et al. Client-centred ADL intervention after stroke: occupational therapists' experiences. Scand J Occup Ther. 2016;23(2):81–90.

- Jones F, Riazi A. Self-efficacy and self-management after stroke: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(10):797–810.

- Jones F, Riazi A, Norris M. Self-management after stroke: time for some more questions? Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(3):257–264.

- Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1–7.

- Parke HL, Epiphaniou E, Pearce G, et al. Self-management support interventions for stroke survivors: a systematic meta-review. PloS One. 2015;10(7):e0131448.

- Pearce G, Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, et al. Experiences of self-management support following a stroke: a meta-review of qualitative systematic reviews. PloS One. 2015;10(12):e0141803.

- Warner G, Packer T, Villeneuve M, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of stroke self-management programs for improving function and participation outcomes: self-management programs for stroke survivors. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(23):2141–2163.

- Wray F, Clarke D, Forster A. Post-stroke self-management interventions: a systematic review of effectiveness and investigation of the inclusion of stroke survivors with aphasia. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(11):1237–1251.

- Holm Ivarsson B. Motiverande samtal. Praktisk handbok för hälso-och sjukvården.[Motivation interviewing. Guidance for use in health care]. Stockholm: Gothia förlag; 2009.

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. New York (NY): Guilford press; 2012.

- Lexell J, R, Fischer M. Rehabiliteringsmetodik [Rehabilitation methodology]. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2017.

- Moffett J. Twelve tips for ‘flipping’ the classroom. Med Teach. 2015;37(4):331–336.

- Låg T, Sæle RG. Does the flipped classroom improve student learning and satisfaction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. AERA pen. 2019;5(3):233285841987048–233285841987017.

- Abeysekera L, Dawson P. Motivation and cognitive load in the flipped classroom: definition, rationale and a call for research. Higher Edu Res Develop. 2015;34(1):1–14.

- Doria N, Condran B, Boulos L, et al. Sharpening the focus: differentiating between focus groups for patient engagement vs. qualitative research. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4(1):1–8.

- Yin RK. Case study research. Design and methods. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE; 2003.