Abstract

Background

The conceptualisation of participation is an ongoing discussion with importance for measurement purposes. The aim of this study was to explore the two subjective subdimensions of participation, involvement and engagement. The purpose was related to measure development within the field of paediatric rehabilitation.

Methods

In a scoping review, following the PRISMA-ScR, the databases MEDLINE, PubMed, Academic Research Complete, PsychINFO, and Business Source Complete were searched for publications that described engagement and/or involvement constructs.

Results

Thirty-nine publications met the inclusion criteria. Involvement could be conceptualised as an unobservable state of motivation, arousal, or interest towards a specific activity or product. Building a consensus over different fields of research, engagement can be seen as the individual’s behavioural, cognitive and affective investment during role performance.

Conclusions

This scoping review points in a direction that the two subdimensions of participation need to be separated, with involvement being a more stable internal state of interest towards an activity, and engagement referring to the specific behaviour, emotions, and thoughts meanwhile participating in a specific setting. Clear definition of concepts will enhance the development of measures to evaluate rehabilitation interventions in the field of occupational therapy and related fields.

Introduction

Optimising participation is one of the main goals in modern healthcare and rehabilitation, particularly for children and adolescents with disabilities [Citation1–6]. Participation is described as a primary outcome in paediatric rehabilitation [Citation7], but it lacks a clear and overall accepted definition. For example, involvement and engagement are subjective subdimensions of participation that are often used interchangeably and thus far have often have been neglected in measuring participation [Citation8]. For measuring purposes clear definitions are needed. In paediatric rehabilitation, it is considered preferable to apply self-reporting when measuring childrens’ participation, as child-reported measures support person-centred and value-based care in line with international conventions on the rights of children and persons with disabilities [Citation9,Citation10]. Adair et al. [Citation8] argue that, to measure subjective or internal aspects of participation, it is important to have the individual as a direct informant. Thus far, self-reported instruments that include the individual aspects of participation are rare and, and thus limiting the evaluation, especially of the subjective perspectives of participation [Citation8]. When measuring participation, concepts and constructs need to be clearly defined. The aim of this study was to explore the two subjective subdimensions of participation, involvement and engagement. The purpose was to identify definitions of the two constructs to be used in measure development, regarding activity participation in children and youth with disabilities.

Following the Oxford dictionary [Citation11] participation is defined as ‘the action of taking part in something’. Involvement is defined as ‘the fact or condition of being involved with or participating in something’. Engagement is defined as ‘an arrangement to do something or go somewhere at a fixed time’ in the context of the activity.

In the World Health Organisation (WHO)’s ‘International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health’ (ICF) – the conceptual foundation of healthcare and rehabilitation practice – participation is defined as ‘involvement in life situations’. The WHO does not give a clear definition of the term, besides one single footnote ‘“involvement” incorporates taking part, being included or engaged in an area of life, being accepted, or having access to needed resources’ [Citation12,p.13]. The ICF has been criticised for its lack of conceptual clarity and for not including the individual’s perspectives on their participation [Citation1,Citation13–15]. Moreover, the conceptual issues contribute to difficulty in trying to measure participation. Both activity and participation are represented as covering the same nine life areas in ICF, representing aspects of functioning from an individual (activity) and societal (participation) perspective [Citation16]. The distinction between the participation and activity dimensions in the ICF is complex, but it is argued that participation is more determined by environmental and cultural factors, whereas activity tends to be more distinct and limited by body impairments [Citation16–18]. Granlund et al. [Citation19] argue that environmental factors in the ICF are mainly based on the social model of disability, with society shaping the physical environment and civil rights but lacking the subjective experience.

There are multiple other models of participation. In the context of participation for children and youth with disabilities, the ‘Family of Participation Related Constructs’ model (fPRC-model) [Citation7] is a more recently developed framework that derived from literature on health, disability, psychology, and education. In the fPRC-model participation is defined as attendance and involvement [Citation7]. The fPRC-model defines involvement as ‘the experience of participation while attending, that may include elements of engagement, motivation, persistence, social connection, and affect’ [Citation7,p.18], and engagement as ‘a unifying construct across ecological levels. Thus, it can be defined depending on the ecological level in which it is examined: (1) the person level – the internal state of individuals’ involving focus or effort; (2) between systems level – an active involvement in interactions between systems; (3) at the macro level – active involvement in a democratic society’ [Citation7,p.20].

Neither the ICF nor the fPRC-model clearly distinguish between, or unify, the two subdimensions. As Granlund et al. discuss [Citation19], the ICF could benefit from another subjective qualifier of participation, since the qualifiers of performance and capacity cannot capture the subjective experience of participation. Furthermore, no consensus can be found between the Oxford dictionary, the ICF, and the fPRC-model. Thus, it remains unclear whether both terms are identical or whether there are distinctions to be made.

Clear definitions are a necessity when measuring participation and the subdimensions, involvement and/or engagement [Citation20–24]. Therefore, an enhanced understanding of both subconstructs is required; to attain this understanding. As research on the subjective subdimansions of participation is scarce, occupational therapists and related healthcare professions may benefit from looking into other and related fields of research for definitions.

The aim of this study was to explore the two subjective subdimensions ofthe participation construct. The research questions were: (i) What definitions of engagement and involvement – applicable for measure development – can be found within different fields of research? (ii) Can the subdimensions of participation, involvement and engagement, be used interchangeably or do they need to be differentiated?

Method

A scoping review method was chosen to broadly explore the conceptualisation of involvement and engagement. This method – a type of knowledge synthesis – aims to start a research process, discover knowledge gaps to be developed in future research [Citation25,Citation26]. The research process followed the PRISMA-ScR guidelines [Citation27]. The main database search took place during May/June 2018, and an update search followed in October 2020. The purpose was to cover fields in which engagement and involvement already have been defined and included in measures. These definitions might be transfereable into healthcare and rehabilitation. Several databases were included in the search process: MEDLINE, PubMed, Academic Research Complete, PsychINFO, and Business Source Complete. These databases were chosen through a discussion with researchers experienced in structured literature reviews in diffenrent databases and fields of research. The search was based on preparatory literature search of the terms ‘involvement construct’ and ‘engagement construct’ using Google Scholar. The search showed that research on involvement was quite pronounced in the fields of consumer and leisure research. Since it was important to get an increased knowledge of the constructs, these fields were added representing by the databases Academic Research Complete, PsychINFO (leisure research) and Business Source Complete (consumer research). For engagement, the research seemed to be most distinctive in economics and management, as well as in educational psychology covered by the databases; Business Source Complete (economics), PsychINFO and Academic Research complete (educational psychology). Since the purpose of the study was to gain an understanding of these constructs for application in the field of healthcare and rehabilitation, medical databases MEDLINE and PubMed, were added to the research process as well.

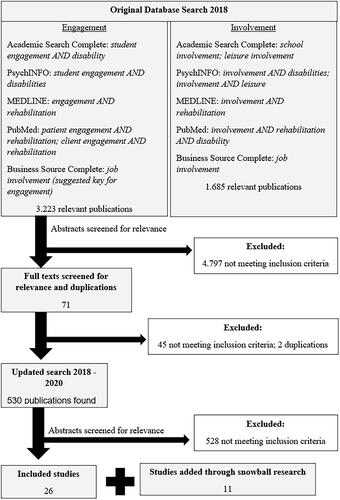

and give an overview of the process of the literature search. Inclusion criteria for publications were: published in English; peer-reviewed; publication defines the ‘involvement’ and/or ‘engagement’ construct; type of publication: theoretical/conceptual article, or instrument development, or review. The inclusion criteria ‘published in English’ and ‘peer-reviewed’ were applied as filters in the initial search in each database. Using only the index words ‘involvement’ or ‘engagement’, the literature search would be too broad and results would not have been manageable in the frame of this scoping review.

Table 1. Detailed overview of database search.

In order to narrow the literature search, additional index words were added. These were based on keywords used by publications found in the initial search on Google-Scholar and the indexed subject headings or controlled terms from a thesaurus/register of each individual database. Since the purpose of the scoping review was related to the field of disability and rehabilitation, the index word ‘rehabilitation’ was added when searching medical databases (MEDLINE and PubMed). For databases within social sciences, the indexed word ‘disability’ or ‘disabilities’ (depending on the index word register of each database) was added. The initial search on ‘involvement construct’ showed high relevance in the field of leisure research, thus ‘leisure’ was used as an additional index word for the involvement construct. Several databases did not include the terms ‘involvement’ and ‘engagement’ as individual index words. In these cases, the suggestions of the individual databases were adapted (see ; ). For example, the database PubMed did not include ‘engagement’ as an individual and index word. Instead, the database suggested ‘patient engagement’ and ‘client engagement’. Because a search on ‘patient engagement’ produced 51,011 results, the search was narrowed using the filter ‘age: child 0–18 years’. Another index word – ‘rehabilitation’ – was added, and as the search still produced 7286 results, a filter (age: child 0–18 years) was added to narrow the search.

In addition – using snowball search – publications that were frequently referred to were added to the search process. The snowball method is a way of finding literature by consulting the bibliography in the key document to find other relevant titles. This strategy ensured the inclusion of articles that might have been excluded due to additionally used index words, or due to different indexing of the articles.

The main search resulted in 3223 publications available for ‘engagement’ and 1685 for ‘involvement’. After screening the titles and abstracts in relation to the inclusion criteria, 71 studies met the inclusion criteria. After excluding duplications (two), the remaining 69 articles were followed up by reading the full texts. Of these, 45 articles did not specifically define the constructs of involvement or engagement. Eventually, 24 publications matched all the inclusion criteria, and were judged resourceful as a basis for a scoping review. The first researcher performed the screening and selection of the articles independently. In the updated search in 2020 – using the same databases and search-terms – another 530 publications were found (87 for engagement; 443 for involvement). After the screening for relevance two additional full-texts were added to the review.

The snowball search resulted in another 11 publications. Thus a total of 37 publications were included in the study (10 for involvement, 27 for engagement). Data extraction was done manually and followed the methodological framework for scoping reviews proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [Citation25]. Data were charted, including information about the author, year of publication, study location, type of study, and researched population. Furthermore, the included publications were screened for definitions and any measures used to capture the constructs of involvement and/or engagement. Charting further included key components of the understanding of the involvement or engagement construct (see and ).

Table 2. Publications included in the involvement construct (* publications added through snowball research).

Table 3. Publications included in the Engagement construct (* publications added through snowball research).

Results

Involvement

Ten publications were found regarding the construct of involvement. These were from the fields of sports management [Citation28], consumer research [Citation21,Citation29], and leisure research [Citation30–36]. Due to similarities in the populations and settings being researched, the publication in sports-management [Citation28] was considered alongside the publications in leisure research. Even though the WHO has defined ‘involvement’ as being central to the definition of participation, no further explanation of the construct could be identified in the included articles, besides the earlier-mentioned footnote in ICF.

Consumer research

Consumer research views involvement primarily as the ‘perceived importance of a product’ [Citation29,p.43], or ‘a person’s perceived relevance of the object based on inherent needs, values, and interests’ [Citation21,p.342]. To evaluate consumer involvement, measures like the ‘Personal Involvement Inventory’ (PII) [Citation21] and the ‘Customer Involvement Profiles’ (CIP) [Citation29] have been developed. The questionnaires originally were meant to capture consumer perceptions of personal relevance relating to several consumer goods [Citation33].

Leisure research

Studies from leisure research viewed involvement as a complex and multidimensional construct [Citation28,Citation30–35]. Havitz and Dimanche [Citation30,p.346] define leisure involvement, based on Rotschild’s definition from 1984, as ‘an unobservable state of motivation, arousal or interest towards a recreational activity or associated product. It is evoked by a particular stimulus or situation and has drive properties’. With minor variations in the formulation, this definition remained consistent in later publications in leisure research and sports-management, which were included in this review (see also ) [Citation28,Citation31–35]. However, authors from leisure research [Citation33] and sports-management [Citation31] base their understanding of involvement on what has been established in consumer research in the 1980s [Citation21,Citation29].

A measure specific to the leisure context is the ‘Modified Involvement Scale’ (MIS) [Citation33]. The self-report MIS questionnaire consists of 15 items related to a specific activity, answered on a five-point Likert scale. The questionnaire is split into three items for each of the five dimensions (attraction; centrality; social bonding; identity affirmation; identity expression) [Citation33].

In leisure research, involvement is seen as a multidimensional construct [Citation28,Citation30–35]. Havitz and Dimanche [Citation30] incorporated the four dimensions of importance, pleasure, sign, and centrality of lifestyle into their conceptualisation of leisure involvement. Publications after the millennium primarily divided involvement into five dimensions. Within sports management, Funk and James [Citation28] identified the dimensions of attraction, sign, centrality to lifestyle, risk probability, and risk consequence. Three recent publications [Citation33–35], all representing leisure research, include the facets of attraction, centrality, social bonding, identity affirmation, and identity expression – the latter being similar to sign – in their understanding of involvement. Attraction refers to a combination of the individual’s perceived importance, preferences, and pleasure towards a specific activity or product [Citation30]. Centrality (to lifestyle) refers to the extent to which the individual’s lifestyle choices and personal investment are structured around an activity [Citation34]. Social bonding explains the social ties that bind the individual to a specific activity [Citation33]. Identity affirmation includes the degree to which a leisure activity offers opportunities to affirm the self to oneself. Identity expression or sign is how one can express this self to others [Citation33]. Finally, Surhartanto et al. [Citation36] conclude that while the dimensions of involvement have varied between authors, the most relevant dimensions might be importance, centrality and self-expression.

Engagement

For the engagement construct, 27 relevant publications were found. These studies were divided into management/economics [Citation37–43], educational psychology [Citation44–55], and healthcare and rehabilitation [Citation24,Citation56–63]. A more detailed overview of the included publications on engagement can be found in .

Management and economics

The earliest definition included in this study was formed 1990 by Kahn [Citation40,p.694], who referred to personal engagement (in a work context) as the ‘harnessing of organisation members’ selves to their work roles; in engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performances’. Here the three dimensions of ‘physical engagement’, ‘cognitive engagement’, and ‘emotional engagement’ are incorporated into a multi-dimensional construct of engagement.

Later, scholars in the field of human resources management further specified engagement, using the term ‘employee engagement’. This did not focus on the individual, but on how employers could motivate their employees and make them work harder [Citation37,Citation64], or improve the employees’ satisfaction with their job and/or organisation [Citation38,Citation39,Citation41]. Consistent in many publications in the management sector is the approach to engagement as a multidimensional or multi-layered construct [Citation38–41].

Educational psychology

Another area of research that has studied the engagement construct extensively in the field of educational psychology – mostly in a school context, calling it ‘student engagement’. However, many publications/studies in this field lack a common definition [Citation44,Citation45,Citation47,Citation49,Citation50,Citation55]. This signifies that researchers need to clarify how they define the construct in their specific studies [Citation44]. Axelson and Flick [Citation46] argued that the origins of the student engagement construct are grounded in the 1980s’ understanding of ‘student involvement’, defined by Alexander Astin as ‘the quantity and quality of physical and psychological energy that students invest in the college experience’ [Citation46,p.40].

Common to the understanding of engagement in educational psychology is the multidimensionality of the construct. Most of the authors in this scoping review included several dimensions in the definition. There is a behavioural or social dimension, as well as a cognitive and an affective, emotional or psychological dimension [Citation44–47,Citation49,Citation50,Citation52,Citation55]. In the context of the affective dimension, authors use the terms ‘affective’, ‘emotional’, and ‘psychological’ interchangeably, describing the same aspects for engagement. Specific to the educational setting, several authors divided the observable behaviours related to engagement into a social/behavioural component and an academic dimension [Citation44,Citation45,Citation49].

Combining all components in educational psychology, engagement is often referred to as a meta-construct [Citation46,Citation50]. Finn and Zimmer [Citation49,p.102–103] define each sub-dimension: academic engagement is seen as the ‘… observable behaviours related directly to the learning process …’; behavioural/social engagement as the ‘… extent to which a student follows written and unwritten classroom rules of behaviour …’; cognitive engagement as ‘… the expenditure of thoughtful energy needed to comprehend complex ideas in order to go beyond the minimal requirements …’; and affective/emotional/psychological engagement as the ‘… emotional response characterised by feelings of involvement in school as a place and a set of activities worth pursuing …’.

Traditionally, observable components of engagement have been prioritised for the evaluation of engagement. Several authors have pointed out that a focus on the cognitive and affective components is now necessary [Citation44,Citation45,Citation52]. To study the cognitive and affective components, self-reported measures such as the ‘Student Engagement Instrument’ (SEI) [Citation45] and the ‘Motivation and Engagement Scale’ (MES) [Citation54] have been developed and tested for their psychometric properties. The SEI measures the student's level of cognitive and affective engagement in their specific school environment [Citation45]. The MES measures the students’ motivation and engagement towards learning, how to study, and their perception of themselves as a student. There are different versions for different settings, like Primary School (MES-Junior School; MES-JS), High School (MES-HS), or Collage and University (MES-UC) [Citation65].

Healthcare and rehabilitation

Discussion on the engagement construct within healthcare and rehabilitation, included in this scoping review, started in the first decade of the 2000s. For the development of the Hopkins Rehabilitation Rating Scale (HRERS), Kortte et al. [Citation60,p.881] define rehabilitation engagement as

… a construct that captures multiple elements, including a patient’s attitude toward the therapy, his/her level of understanding or acknowledgment of a need for treatment, the need for verbal or physical prompts to participate, the level of active participation in therapy activities, and the level of attendance throughout the rehabilitation program.

Later, Lequerica and Kortte [Citation61] specified that rehabilitation engagement is specifically focussed on the rehabilitation or therapy process, being the effort and commitment the patient shows in working towards the goals of the intervention, through both active participation and collaboration with the treatment provider. This is in accordance with the conceptualisation of engagement by ‘The US Centre for Advancing Health’, quoted by Rieckmann et al. [Citation63,p.204] as ‘… actions individuals must take to obtain the greatest benefit from the healthcare services available to them’.

Algeria et al. [Citation56] limited the construct of engagement to the attendance of scheduled health appointments, whereas King, Currie and Peterson conceptualised engagement as a multidimensional construct, defining engagement as ‘… a multifaceted state of affective, cognitive, and behavioural commitment or investment in the client role over the intervention process’ [Citation24,p.2]. King et al. [Citation24] defined engagement as a combination of an affective, a cognitive, and an observable behavioural component. All these components influence one another. King et al. [Citation59] used this definition when developing the ‘Paediatric Rehabilitation Intervention Measure of Engagement-Observation’ (PRIME-O). In the Prime-O the healthcare professionals fills out an observation-protocol on the clients engagement in relation to eigth observable indicators of engagement [Citation59].

In their review of the engagement construct in healthcare and rehabilitation Bright et al. [Citation57] viewed engagement as both a state of being ‘engaged in’ (e.g. activity) and a process of ‘engaging with’ (e.g. someone). They agreed on the multidimensionality of the construct and argued for measures that include items focussing on the internal state of engagement. Bright et al. [Citation57] also pointed out the difference between engagement and involvement, with involvement existing on a continuum – from being a passive recipient of information to being autonomously in one's decisions – and, engagement being more than that, and incorporating active partaking in the specific activity.

Based on prior research by Bright et al. [Citation57], Mayhew et al. [Citation62] adapted the HRERS for the reablement context in England. In this context, they define engagement based as ‘a purposeful act, with collaboration and cooperation being an active choice on the part of the patient and done in order to maximise outcomes or to improve their experience of receiving an intervention’ [Citation62,p.778]. They also give five dimension for the observation of patient engagement in the reablement context. These consist of attendance, need for physical or verbal prompts to participate, positive attitude towards the therapy activity, acknowledgement/acceptance of need for services, active participation

Discussion

The results from this scoping review indicates that the two subdimensions of participation need to be separated, with involvement being a more stable internal state of interest towards an activity and engagement refering to the specific in behaviour, emotions, and thoughts meanwhile participating in a specific setting. However, both constructs also overlap at some points and interact with each other.

Involvement

The scoping review identified two fields of research that both defined and measured involvement – consumer research [Citation21,Citation29] and leisure research [Citation30–36]. Since one of the main goals and outcomes of rehabilitation interventions is increasing participation [Citation12,Citation15], the conception given in leisure research – focussing on leisure activity and products associated with them – seems closer to rehabilitation than consumer research – focussing on the consumption of products by consumers. There seems to be a consensus on defining involvement as an unobservable state of motivation, arousal or interest towards a specific activity or product [Citation28,Citation30–35]. This internal state is triggered by a specific stimulus or situation. Moreover, leisure research agrees on the multidimensionality of the construct, with the earlier described five sub-dimensions, (attraction; centrality; social bonding; identity affirmation; identity expression) [Citation33–35]. Surhartanto et al. [Citation36] argue that of these dimensions, attraction, centrality and identity-expression might be the most relevant. Havitz and Mannell [Citation66] further distinguish between ‘situational involvement’ and ‘enduring involvement’. The former is more connected to an individual situation and context, while the latter describes a more stable state over a long time period. In regards to measuring involvement, Havitz and Mannell [Citation66] argue that situational involvement can only be measured validly in the individual situation since it depends to a large extent on the specific context – as engagement does. In the view of the authors, possible measure of participation will assess the general patterns of participation and levels of involvement towards different activities (enduring involvement).

An important take-home message of this study is that involvement seems to be an internal state (e.g. ‘interest in’ football, classical music, etc.) that can affect the individual’s behaviour [Citation21,Citation31]. It is hardly observable because it does not imply actively executing the activity. A youngster with disability could, for example have high levels of involvement with football without ever playing the game, by being most interested in the ‘product’ of football (e.g. professional football leagues). Of course, this interpretation depends on how far one stretches the concept of participation. Is someone already participating in football simply by watching a match on TV, or does one have to be on the pitch, kicking the ball? Following the general definition of participation in the Oxford dictionary, the former version would not be sufficient [Citation11].

Existing measures of involvement are often proxy and retrospectively rated, focussing on enduring involvement. Since involvement seems to be an internal state it would probably be difficult to capture involvement by someone else than the child or youth itself, or for them to recreate how they might have been thinking or feeling at an earlier time when they were ‘involved’. The lack of self-report or self-ratings in healthcare and rehabilitation is therefore a limitation and needs to be addressed [Citation8]. Furher, since involvement seems to be a rather stable internal state it could perferably be measured longitundinally.

Engagement

A similarity finding in the literature from economics/management, educational psychology, and healthcare and rehabilitation is the multidimensionality of the construct of engagement, consisting of an observable component of ‘behavioural engagement’ and two unobservable components ‘affective/emotional/psychological engagement’ and ‘cognitive engagement’ [Citation24,Citation40,Citation44–46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation54,Citation59].

Using football as an example once again, an adolescent could engage in the activity during physical education lessons. In that situation, she could follow all the rules, having many effective contacts with the ball, and contributing to the team’s success (high level of behavioural engagement), yet feel uncomfortable and experience a poor relationship with the teacher and/or team-mates (affective engagement). Moreover, one might not see any value in the activity for future endeavours or personal development (cognitive engagement), since it teaches the individual no skills that will be needed in future life. For example an adolescent might participate in football for different reasons: in order to participate together with friends, in order to compete in tournements, or just to stay fit. In this case, the individual would have a low level of cognitive and affective engagement.

A definition of engagement across all the included fields of research, should comprise the individual’s behavioural, cognitive and affective investment during role performance. Role performance implies that the individual is executing and experiencing their specific role, for example, as a student, playmate, player in a sports team etc., in a specific context (e.g. school, peer group, sports club). Going back to the football example our youngster might participate in playing football at P.E. lessons as a student in order to earn grades, or playing football as a peer together with friends just for fun, or as a team-mate in a sportsclub in order to compete. Eventhough participation take place in the same activity every time, the different contexts will effect the person’s role, motivation and the expectations towards the activity. This scoping review has shown that the unobservable aspects of engagement are subjective [Citation44,Citation45,Citation49,Citation57,Citation60]. Most definitions refer to a specific role – often already applied in the terminology – in a specific context. In management and economics authors speak of ‘employee engagement’ in the context of a specific work environment, organisation, or company [Citation38,Citation39,Citation42,Citation43]; in educational psychology, scholars speak of ‘student engagement’ in the specific context of a school [Citation44,Citation46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation52]; and in healthcare and rehabilitation researchers refer to ‘client engagement’ [Citation24], or ‘patient engagement’ [Citation57,Citation63] in the context of a rehabilitation, or therapy interventions. This notion of different contexts influencing the individual is in line with the transactional framework for paediatric rehabilitation, proposed by King et al. [Citation67], were the authors argue that transactional processes between diffenrent contexts and individuals lead to development.

A change in setting (e.g. transitioning through school) will also influence the subjective perception of the child/adolescent regarding its experience during participating in an activity. Accordingly, before measuring engagement, a definition of both role and setting is necessary in order to choose an appropriate measuring instrument. Moreover, data on engagement of a child/adolescent in one setting may not automatically be transferred to another setting. Furthermore, engagement is always connected to the actual execution of, or participation in, a specific activity, in a specific context/setting.

Within educational psychology, healthcare and rehabilitation, researchers have pointed out that in the past the observable components have dominated the measurement of engagement, and that a focus on the internal and subjective components is now required [Citation8,Citation15,Citation45]. To examine the subjective, unobservable components of cognitive and/or affective engagement self-reported instruments like the SEI [Citation45] or the MES [Citation54] in educational psychology are necessary. In healthcare and rehabilitation, engagement has thus far mainly been assessed by referring to medical records and frequency of attendance [Citation56], therapist-reported questionnaires like the HRERS [Citation60] or HRERS-RV [Citation62], or observable protocols like the PRIME-O [Citation59]. At the same time, Adair et al. have recommended more self-reported instruments [Citation8].

Relationship between involvement and engagement

In educational psychology, Axelson and Flick [Citation46] argued that even though student engagement is grounded in student involvement theory from the 1980s, the two concepts may have grown apart over time. Duchan [Citation48] specified the difference between the constructs, saying that engagement is a display of ‘involvement in action’. This can be supported within healthcare and rehabilitation by Bright et al. [Citation57], who argue that being active in the specific setting of therapy is the necessary component that separates engagement from involvement, making involvement a precondition for engagement.

The fact that authors in healthcare and rehabilitation [Citation59] or educational psychology [Citation49] label their sub-dimensions of engagement with behavioural, affective or cognitive ‘involvement’, or use the term ‘involvement’ in their descriptions of the engagement construct, makes the discussion difficult. At the same time, such cases exemplify the ongoing confusion about the two constructs.

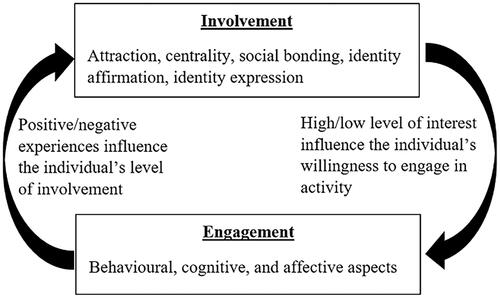

From the perspective of this scoping review – searching for definitions on involvement and engagement, especially feasible for measure development – the constructs of involvement and engagement need to be separated. Involvement describes a general internal interest and arousal towards, or motivation for, a specific activity or activity-related product, whereas engagement refers to the specific demonstrated behaviour and internal experience while performing an activity in a specific setting. Undoubtedly, both concepts interact with one another and are likely to be transactional. High levels of involvement (i.e. interest in professional football) may support a willingness to engage in the activity and interact with others in a given activity/situation (i.e. attending training at a football team/club); and positive experiences while engaging in an activity may positively affect the person’s subsequent level of involvement. Thus, both constructs overlap, especially when comparing situational involvement and the internal aspects of engagement. When measuring participation in general, researchers should focus on enduring involvement for the general interest in specific activities (e.g. football). Cognitive and affective engagement are to be measured context-specific (e.g. the experience of participating in football during P.E. lessons at school).

Following the understanding of the involvement and engagement constructs in this scoping review, one could consider rephrasing the definition of participation in the ICF (‘involvement in life situation’ [Citation12,p.9]) into ‘engagement in life situations’. Involvement in a life situation would merely describe a person’s interest, or perceived relevance towards, a specific life situation or setting, be it education, work, or leisure. This does not necessarily imply taking part in the life situation. Moreover, the footnote in the ICF, describing the WHO’s understanding of involvement – ‘… ’involvement’ incorporate taking part, being included or engaged in an area of life, being accepted, or having access to needed resources’ [Citation12,p.13] – seems much more congruent with the concept of engagement in the literature reviewed in this scoping review. ‘Taking part’ would reflect the behavioural dimension of engagement and ‘being included’ or ‘being accepted’ would reflect the affective dimension of engagement. This approach is similar to Krieger et al. [Citation68, p.2], who extent the ICF definition in the context of adolescents with autism spectrum disorder as ‘… being engaged in and/or performing meaningful activities in occupational and social roles …’ Approaches like that could enrich the ICF-framework and might give it more clearity.

With regard to the fPRC model [Citation7], the findings of this scoping review point towards an argument that characterises involvement in a way that most sources of this review would define as engagement. This accounts mostly for the statement ‘… experience of participation while attending …’ [Citation7, p.18] in the fPRC-model’s definition of involvement, which literature in this review would use to describe as engagement. At the same time, Imms et al. [Citation7] refer to personal preferences, as a separate intrinsic factor of participation. Where the fPRC-model sees engagement more as a precondition of involvement, which the literature of this review connects to the involvement sub-dimension of attraction. The results of this scoping review lead to the argument that it might be the other way around, with involvement as an internal state of motivation, working as a prerequisite of engagement. However, this might be a ‘what was first: egg or hen?’-argument, since both constructs may interact in a kind of loop effect (as shown in ). Therefore, it strongly dependends on the individual’s standpoint.

This study has to recognise some limitations. The main one would be that most of the screening and charting was executed by one person (the first author). Moreover, the number of fields of research and databases searched this was not deemed feasible. Future studies, focussing on singular aspects in single fields of research, should use fewer index words and limitations, to wider the scope of publications included in the first round of screening. This could, for example, also increase the variety of perspectives within one field of research. The choice of databases can also be discussed as other databases may have given other perspectives. No evaluation was done of the studies quality regarding their risk of bias. Since the aim was to evaluate the definition of constructs and not the effect of interventions the evaluation was conisered to not be necessary.

Conclusion and future directions

This scoping review explored knowledge from other and partly unreleated fields. The results gained, point in a direction that the two subdimensions of participation need to be separated, with involvement being a more stable internal state of interest towards an activity and engagement refering to the specific in behaviour, emotions, and thoughts meanwhile participating in a specific setting. However, both constructs also overlap at some points and interact with each other. This knowledge is useful in the development of self-reported measures of participation for occupational theapists in the field of paediatric rehabilitation as well as in other fields or for other professionals. The subdimension, involvement, can be used for measuring general participation of the individual longitudinally, since it is assumed to be rather stable over time. However, engagement, being connected to a specific settings, could be used when evaluating participation in specific activities in specific settings. The results of this study may be useful for future research in this area.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bedell G, Coster W, Law M, et al. Community participation, supports, and barriers of school-age children with and without disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(2):315–323.

- Chien C-W, Rodger S, Copley J, et al. Comparative content review of children's participation measures using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health-Children and Youth. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(1):141–152.

- Coster W, Law M, Bedell G, et al. Development of the participation and environment measure for children and youth: conceptual basis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(3):238–245.

- Imms C, Adair B, Keen D, et al. 'Participation': a systematic review of language, definitions, and constructs used in intervention research with children with disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(1):29–38.

- Mei C, Reilly S, Reddihough D, et al. Activities and participation of children with cerebral palsy: parent perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(23):2164–2173.

- Shikako-Thomas K, Kolehmainen N, Ketelaar M, et al. Promoting leisure participation as part of health and well-being in children and youth with cerebral palsy. J Child Neurol. 2014;29(8):1125–1133.

- Imms C, Granlund M, Wilson PH, et al. Participation, both a means and an end: a conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(1):16–25.

- Adair B, Ullenhag A, Rosenbaum P, et al. Measures used to quantify participation in childhood disability and their alignment with the family of participation-related constructs: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(11):1101–1116.

- Simeonsson RJ, Leonard M, Lollar D, et al. Applying the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) to measure childhood disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25(11–12):602–610.

- Arvidsson P, Dada S, Granlund M, et al. Content validity and usefulness of Picture My Participation for measuring participation in children with and without intellectual disability in South Africa and Sweden. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;27(5):336–348.

- Lexico [Internet]. Oxford University Press. 2019. [cited 2019 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.lexico.com/en?search_filter=dictionary.

- World Health Organisation. International Classification of Function, Disability, and Health World Health Organisation. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

- Hemmingsson H, Jonsson H. An occupational perspective on the concept of participation in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health-some critical remarks. Am J Occup Ther. 2005;59(5):569–576.

- Coster W, Bedell G, Law M, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Participation and Environment Measure for Children and Youth. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(11):1030–1037.

- Cogan AM, Carlson M. Deciphering participation: an interpretive synthesis of its meaning and application in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(22):2692–2703.

- Whiteneck G, Dijkers MP. Difficult to measure constructs: conceptual and methodological issues concering participation and environmental factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(11):22–35.

- Badley EM. Enhancing the conceptual clarity of the activity and participation components of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(11):2335–2345.

- Mitra S, Shakespeare T. Remodeling the ICF. Disabil Health J. 2019;12(3):337–339.

- Granlund M, Arvidsson P, Niia A, et al. Differentiating activity and participation of children and youth with disability in Sweden: a third qualifier in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health for children and youth? Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91(13):84–96.

- Himmelfarb HS. Measuring religious involvement. Soc Forces. 1975;53(4):606–618.

- Zaichkowsky JL. Measuring the involvement construct. J Consum Res. 1985;12(3):341–352.

- Barki H, Hartwick J. Rethinking the concept of user involvement. MIS Q. 1989;13(1):53–63.

- Andrews JC, Durvasula S, Akhter SH. A framework for conceptualizing and measuring the involvement construct in advertising research. J Advert. 1990;19(4):27–40.

- King G, Currie M, Petersen P. Child and parent engagement in the mental health intervention process: a motivational framework. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2014;19(1):2–8.

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodogical framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473.

- Funk DC, James J. The psychological continuum model: a conceptual framework for understanding an individual’s psychological connection to sport. Sport Manage Rev. 2001;2001(4):119–150.

- Laurent G, Kapferer J-N. Measuring consumer involvement profiles. J Market Res. 1985;22(1):41–53.

- Havitz ME, Dimanche F. Leisure involvement revisited: conceptual conundrums and measurement advances. J Leisure Res. 1997;29(3):245–278.

- Wiley CGE, Shaw SM, Havitz ME. Men's and women's involvement in sports: an examination of the gendered aspects of leisure involvement. Leisure Sci. 2000;22(1):19–31.

- Funk DC, Ridinger LL, Moorman AM. Exploring origins of involvement: understanding the relationship between consumer motives and involvement with professional sport teams. Leisure Sci. 2004;26(1):35–61.

- Kyle G, Absher J, Norman W, et al. A Modified Involvement Scale. Leisure Stud. 2007;26(4):399–427.

- Jun J, Kyle GT, Vlachopoulos SP, et al. Reassessing the structure of enduring leisure involvement. Leisure Sci. 2012;34(1):1–18.

- Havitz ME, Kaczynski AT, Mannell RC. Exploring relationships between physical activity, leisure involvement, self-efficacy, and motivation via participant segmentation. Leisure Sci. 2013;35(1):45–62.

- Suhartanto D, Dean D, Sumarjan N, et al. Leisure involvement, job satisfaction, and service performance among frontline restaurant employees. J Qual Assur Hosp Tour. 2019;20(4):387–404.

- Bhuvanaiah T, Raya RP. Employee engagement: key to organizational success. SCMS J Indian Manage. 2014;11(4):61–71.

- Madan S. Moving from employee satisfaction to employee engagement. CLEAR Int J Res Comm Manage. 2017;8(6):46–50.

- Harashitha. Employee engagement: a literature review. Int J Res Comm Manage. 2015;6(12):97–100.

- Kahn WA. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad Manage J. 1990;33(4):692–724.

- Ho Kim W, Park JG, Kwon B. Work engagement in South Korea: validation of the Korean version 9-item Utrecht work engagement scale. Psychol Rep. 2017;120(3):561–578.

- Kumar V, Pansari A. Competitive advantage through engagement. J Market Res. 2016;53(4):497–514.

- Megha S. A brief review of employee engagement: definition, antecendents and approaches. CLEAR Int J Res Comm Manage. 2016;7(6):79–88.

- Appleton JJ, Christenson SL, Furlong MJ. Student engagement with school: critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychol Schs. 2008;45(5):369–386.

- Appleton JJ, Christenson SL, Kim D, et al. Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: validation of the student engagement instrument. J Sch Psychol. 2006;44(5):427–445.

- Axelson RD, Flick A. Defining student engagement. Change. 2010;43(1):38–43.

- Dhanesh GS. Putting engagement in its proper place: state of the field, definition and model of engagement in public relations. Public Relat Rev. 2017;43(5):925–933.

- Duchan JF. Engagement: a concept and some possible uses. Semin Speech Lang. 2009;30(1):11–17.

- Finn JD, Zimmer KS. Student engagement: What is it? Why does it matter? In: Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C, editors. Handbook of research on student engagement. Buston: Springer; 2012. p. 93–128.

- Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH. School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev Educ Res. 2004;74(1):59–109.

- Fredricks JA, Bohnert AM, Burdette K. Moving beyond attendance: lessons learned from assessing engagement in afterschool contexts. New Dir Youth Dev. 2014;2014(144):45–58.

- Hollingshead A, Carnahan CR, Lowrey KA, et al. Engagement for students with severe intellectual disability: the need for a common definition in inclusive education. Inclusion. 2017;5(1):1–15.

- Kemp C, Kishida Y, Carter M, et al. The effect of activity type on the engagement and interaction of young children with disabilities in inclusive childcare settings. Early Childhood Res Q. 2013;28(1):134–143.

- Liem GA, Martin AJ. The motivation and engagement scale: theoretical framework, psychometric properties, and applied yields. Aust Psychol. 2012;47(1):3–13.

- Moreira PAS, Bilimoria H, Pedrosa C, et al. Engagement with school in students with special educational needs. Int J Psychol Psychol Ther. 2015;15(3):361–375.

- Alegria M, Carson N, Flores M, et al. Activation, self-management, engagement, and retention in behavioral health care: a randomized clinical trial of the DECIDE intervention. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):557–565.

- Bright FAS, Kayes NM, Worrall L, et al. A conceptual review of engagement in healthcare and rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(8):643–654.

- Graffigna G, Barello S, Bonanomi A. The role of Patient Health Engagement Model (PHE-model) in affecting patient activation and medication adherence: a structural equation model. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179865–19.

- King G, Chiarello LA, Thompson L, et al. Development of an observational measure of therapy engagement for pediatric rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(1):86–97.

- Kortte KB, Falk LD, Castillo RC, et al. The Hopkins Rehabilitation Engagement Rating Scale: development and psychometric properties. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(7):877–884.

- Lequerica AH, Kortte K. Therapeutic engagement: a proposed model of engagement in medical rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89(5):415–422.

- Mayhew E, Beresford B, Laver-Fawcett A, et al. The Hopkins Rehabilitation Engagement Rating Scale – Reablement Version (HRERS-RV): development and psychometric properties. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;2019;27(3):777–787. ():

- Rieckmann P, Boyko A, Centonze D, et al. Achieving patient engagement in multiple sclerosis: a perspective from the multiple sclerosis in the 21st Century Steering Group. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4(3):202–218.

- Zinger D. William Kahn: Q&A with the founding father of engagement. 2017. https://www.saba.com/blog/william-kahn-qa-with-the-founding-father-of-engagement-part-1 & https://www.saba.com/blog/william-kahn-qa-with-the-founding-father-of-engagement-part-2.

- Martin AJ. Examining a multidimensional model of student motivation and engagement using a construct validation approach. Br J Educ Psychol. 2007;77(Pt 2):413–440.

- Havitz ME, Mannell RC. Enduring involvement, situational involvement, and flow in leisure and non-leisure activities. J Leisure Res. 2005;37(2):152–177.

- King G, Imms C, Stewart D, et al. A transactional framework for pediatric rehabilitation: shifting the focus to situated contexts, transactional processes, and adaptive developmental outcomes. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(15):1829–1841.

- Krieger B, Piskur B, Schulze C, et al. Supporting and hindering environments for participation of adolescents diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202071.