ABSTRACT

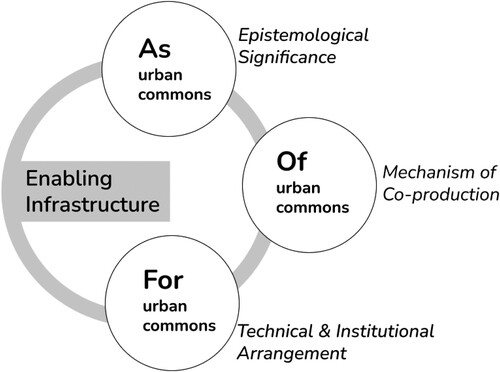

In response to the unprecedented urban challenges, there is an urgent call for alternative system of communal support that enable humanity to respond collectively to the crises it faces. In particular, cities need to proactively provide urban services and infrastructure that are able to adapt to the ever-increasing wicked problems. We propose ‘enabling infrastructure’ as a key instrument for the realization and operation of the enabling city. The essence of infrastructure is reframed from the perspective of urban commons, in which we focus on the necessity of urban commons-based design and provision of infrastructure that enable people to reconfigure their lives autonomously. We illustrate how enabling infrastructure can work in practice by demonstrating infrastructure in three settings: infrastructure AS urban commons (epistemological significance), infrastructure OF urban commons (mechanisms of co-production), and infrastructure FOR urban common (technical and institutional arrangements). First, we discuss how recognizing and (re)defining infrastructure as the urban commons is conducive to enabling people to be active citizens. Second, we examine mechanisms that commons-based production, design, and management of urban infrastructure is practiced for the enabling. Third, we demonstrate that the enabling is further facilitated by using infrastructure as a technical and institutional arrangements for the urban commons. Ultimately, this paper posits that a city itself needs to function as the commons and as a meta-infrastructure organizing other infrastructure into the commons level.

A city needs to become an enabling city to respond to global crises

Infrastructure of the city should be seen from the lens of the urban commons.

The essence of infrastructure is to ‘enable’ people to be active citizens

Enabling Infrastructure can work in three settings: as, of, for the urban commons.

Highlights

1. Introduction

In the face of unprecedented challenges such as climate change, pandemics, and socio-economic crises (Fraser, Citation2022), there is an urgent call for communal support that enable humanity to respond collectively to the crises it faces. In particular, cities need to proactively provide urban services and infrastructure that are able to adapt to the ever-increasing wicked problems (UN-Habitat, Citation2022). However, exiting public solutions (either state-centred or market-oriented) have been found to inadequately respond to the diverse political and social needs and demands that are emerging alongside the wave of rapid urban changes (Bollier, Citation2015, Citation2021; Unger, Citation2015).

Against this backdrop, this paper explores the possibility of an alternative system of collective support and collaboration at the urban scale. We pay particular attention to the concept of the ‘enabling city’ (e.g. Camponeschi, Citation2010, Citation2013), which was proposed more than a decade ago but has not been comprehensively discussed yet.Footnote1 We focus on this concept because it offers a promising avenue to move beyond the traditional ‘state-market’ dichotomy, which has constrained the imaginative and visionary possibilities of contemporary public systems (Bollier, Citation2014; Kostakis & Bauwens, Citation2014). The enabling city emphasizes the importance of empowering people to engage in the collective process of urban transformation, based on their own needs and capacities (Camponeschi, Citation2010, Citation2013). Importantly, here, people are not seen to be mere consumers or passive recipients of public services. The concept focuses on discovering and enabling (new) actors to build public interests and community cooperation.

In practice, however, there has been limited discussion on how this ‘enabling’ aspect can be operated and what mechanisms and levers are needed for enabling. Therefore, this insight paper is to propose ‘enabling infrastructure’ as a key instrument for the realization and operation of the enabling city. In doing so, the essence of infrastructure is reframed from the perspective of urban commons (Borch & Kornberger, Citation2015), in which we focus on the necessity of urban commons-based design and provision of infrastructure that enable people to reconfigure their lives autonomously. We illustrate how enabling infrastructure can work in practice by demonstrating infrastructure in three settings: infrastructure AS urban commons (epistemological significance), infrastructure OF urban commons (mechanisms of co-production), and infrastructure FOR urban common (technical and institutional arrangements). Ultimately, this paper suggests that a city itself needs to function as the commons and as a meta-infrastructure organizing other infrastructures into the commons level.

2. Reframing infrastructure from the perspective of urban commons

2.1. Perspective on infrastructure

Infrastructure typically refers to physical structures and facilities like dams, buildings, roads, railways, airports, and communication networks (Oxford languages, Citation2023), which serve as the material foundation that mediates organizations and enables individuals to do meaningful activities (Larkin, Citation2013). However, sustaining the operation and the provision of infrastructure has become ever challenging due to obsolescence, ever-increasing demand (OECD, Citation2014), and breakdown or failure of the system (Graham, Citation2010; Green, Citation2016; Schwenkel, Citation2015). Moreover, infrastructure often causes and leads to disparity in accessibility, social inequality, and anti-ecological effects (Burchardt & Laak, Citation2023; Dhakal, Zhang, & Lv, Citation2021; Graham & Marvin, Citation2001; McFarlane, Citation2010), failing to support the everyday lives of citizens (Berlant, Citation2016), as well as tackling complex problems such as the climate crisis (Degens, Hilbrich, & Lenz, Citation2022). This context motivates a reflexive questioning of what infrastructure is, does, for what, and for whom.

The meaning of infrastructure has expanded to a broader one that includes what was not considered infrastructure traditionally (e.g. finance, digital platform) (Kanoi, Koh, Lim, Yamada, & Dove, Citation2022; Klinenberg, Citation2018; Plantin & Punathambekar, Citation2019). The expanded perspective reconsiders social dimensions, in which infrastructure is situated, examining the relationship between infrastructure and people, and its socio-political ramifications (Kanoi et al., Citation2022; Simone, Citation2004; Star, Citation1999). Such a view provided an opportunity to critically acknowledge that infrastructure often created boundaries, sorting what it enables, and what constraints – e.g. dismissing other people and (indigenous) infrastructures, thereby dispossessing the associated communities (Anand, Gupta, & Appel, Citation2018; Anguelovski et al., Citation2016; Harvey & Knox, Citation2015; Kanoi et al., Citation2022; Schwenkel, Citation2015; Scott, Citation1998).

The expanded epistemology, notably, posits that people are and should be the most integral part of infrastructure (Kanoi et al., Citation2022; Simone, Citation2004, Citation2021). People make infrastructure work by connecting its elements, and organize their daily lives, actively being involved in its operation (Anand, Citation2017). Such a view connotes people themselves as the infrastructure of infrastructure. We advocate this concept of ‘people as infrastructure’ since, as Simone (Citation2021) highlighted, people collectively can exercise constructive capacity by forging essential connections vital to their everyday lives. Thus, the question about infrastructure is not to demarcate what infrastructure is, but to re-establish the essence of infrastructure; infrastructure is created as people’s collective practices and can be defined by its effect ‘enabling’ themselves (Larkin, Citation2013).

2.2. Seeing infrastructure through the lens of the ‘urban commons’

The above perspective aligns with the idea of the urban commons. The urban commons goes beyond traditional discussions on commons (Foster & Iaione, Citation2019). It emphasizes that cities are inherently constituted by encounters of disparate individuals and matters (Borch & Kornberger, Citation2015), challenging the notion that the commons is governed by a community as a bounded group (Ostrom, Citation1990). As an intricate web of humans, matters, and technology, the urban collectively form a relational network (Metzger, Citation2015; Simone, Citation2021; Weber, Citation2015). The concept enables us to see that cities are the ‘collective oeuvre (work)’ of their inhabitants, as Lefebvre (Citation1967) declared, and that the ‘right to the city’ is something to be practised. As a space where people coexist, share resources, communicate, and exchange ideas and bodies, the urban shapes ‘modes of thoughts, action, and life’ (Lefebvre, Citation2003, p. 32).

From this perspective, for the ‘enabling city’, we propose that infrastructure be reconceptualized through the lens of the urban commons, based on the following tenets. First, infrastructure can be redefined as collectively constructed from below rather than from above (Graham & McFarlane, Citation2014). Building upon the ‘right to the city’ (Lefebvre, Citation1967), this perspective allows us to recognize that infrastructure can be intervened in and reconfigured through people's everyday practices. This contrasts with the view that infrastructure is simply hardware that is strategically produced for specific purposes or for certain users to benefit. Infrastructure is both the performative outcome and the collective and collaborative practice through which people maintain and develop their social lives.

Second, infrastructure can be seen as a common open platform that facilitates convivial intersections and interactions among different actors, considering the collective and collaborative nature of labour. In practice, infrastructure is often planned, used, and modified in rigid manners (Chester & Allenby, Citation2019) despite that the value of a city can only be created through mediation and collaboration of different entities, human and non-human (Hardt & Negri, Citation2009). In this context, from the urban commons perspective, infrastructure needs to be re-imagined as a flexible and open network that catalyzes the exchange of ideas and ad-hoc collaborations of different agents, even those who would never have imagined that they could collaborate (Rao, Citation2007; Simone, Citation2004).

Third, as an open platform for collaboration, infrastructure contributes to creating new grammars for sharing the commonwealth (created by collaboration) that enable us to (re)produce ourselves as commoners. Seeing infrastructure as urban commons will promote a sense of commonality and thus ultimately prompt us to develop commons-governance skills, i.e. sharing and circulating social goods (Alphandéry et al., Citation2014). The urban area is constantly privatized and segregated. To overcome the illusion of the ‘self-reliant individual’ that has underpinned the current socio-ecological crisis, there is a critical need to expand the space and time for people to share infrastructure as a fundamental basis for collective living, despite myriad differences (De Lange & de Waal, Citation2019).

Overall, using the lens of urban commons provides an epistemological and practical framework to recognize ourselves as a part of the commons. Being seen as the urban commons, infrastructure can be used to spark more convivial and creative social relationships. The openness and flexibility of infrastructure are crucial for activating dynamic collaboration and co-production, expanding networks of care beyond an intimate community. It can contribute to making cities more vibrant, innovative, and problem-solving spaces, favourable for finding adaptive responses to the current socio-ecological crises (Bollier, Citation2014; Kostakis & Bauwens, Citation2014).

3. Enabling infrastructure: infrastructure as, of, for urban commons

Based on the discussion in Section 2, we propose ‘Enabling Infrastructure’ as a key instrument for the realization and operation of enabling cities (). We showcase how enabling infrastructure can work in practice, by demonstrating infrastructure in three settings: (1) infrastructure As urban commons, (2) infrastructure Of urban commons, and (3) infrastructure For urban commons. First, ‘infrastructure as urban commons’ focuses on the epistemological values of infrastructure for communal solidarity. More specifically, we illustrate how recognizing and (re)defining infrastructure as the urban commons can help enabling people as active citizens. Second, ‘infrastructure of urban commons’ discusses the mechanism that enabling can be operated through commons-based production and design of urban infrastructure. Third, ‘infrastructure for urban commons’ demonstrates institutional and technical arrangements for facilitating the co-production and design of urban infrastructure, which can further support the enabling.

3.1. Infrastructure as urban commons

Seeing infrastructure ‘as’ urban commons allows us to radically subvert our thinking and attitudes towards relationships between infrastructure and humans. Such a perspective contributes to not only expanding the scope and the scale of infrastructure but also changing the way infrastructure is initiated and activated. We argue for the importance of fully recognizing and redefining infrastructure as urban commons through conscious and sometimes political actions. Through such practices, people can be enabled to actively engage in the collective process of making cities alongside a myriad of other people.

The protest for better accessibility of disabled people to the Seoul subway in South Korea illustrates the enabling process where people actively re-defined urban infrastructure as the urban commons. The Solidarity Against Disability Discrimination (SADD), an activist group, has led ‘Subway Struggle in Rush Hour’ campaign from December 2021 to July 2023, demanding for the guarantee of ‘mobility right for disabled people’. This action faced a fierce backlash too, revealing a dual attitude – sympathy for the need to expand mobility rights but resistance to the disruptive protests. The ruling party leader denounced the protest as an ‘illegal demonstration’ that caused ‘inconvenience to the largest number of people’ (Na, Citation2022, p. 4.11). While most citizens (80% of them) agreed that disabled people faced significant barriers to using public transport, many of them considered the way protest was organized inappropriate (Jeong, Citation2023, p. 5.16).

The struggle is closely related to the dominant view of infrastructure, which considers infrastructure as a device primarily for increasing the efficiency of urban services. As mass transport systems were designed to boost industrialization and serve mass commuters, a specific view on infrastructure aligned with the systems’ purposes and functions has also been reinforced. Such a view focuses on getting the maximum number of people to their destinations as effectively as possible rather than considering a wider diverse range of potential users such as the rights of minorities like the disabled. In this context, transport services can unintentionally constrain some people who do (can) not fit with the desired outcome of the system which is speed. This reality paradoxically reveals the need for a new way of viewing and thinking about infrastructure. The activists of SADD proactively claimed the transport system as the urban commons with goals of ‘changing relationships between people’ and ‘transforming community environment’ (Goh, Citation2023). Such an action created momentum for citizens to realize that the subway should be the urban commons where various people share the service and expand their capacity to be with others. Through the direct action of recognition and calling their fellow citizens commoners, the group tried to become a part of an enabling infrastructure that knits the social tissue in a new way to live together.

The Italian Water Privatization Referendum is another example demonstrating that reclaiming infrastructure as urban commons is vital. In the early 2000s, Italian legal academia groups established ‘Rodotà Commission (la Commissione Rodotà)’ and they tried to legalize public goods as ‘demanio’ (those public goods subjected to a lien of inalienability) (Vercellone, Citation2020, p. 4). With the global financial crisis, the government and the parliament tried to legislate the privatization of public water distribution service; however, huge social movements for the defence of public water as commons took place. On the one hand, some jurists in the Commission prepared a draft of the queries of the referendum against the water privatization law. On the other hand, a common front was formed as associations involving the third sector, environmental organizations, political parties, and legal academia as allies (Vercellone, Citation2020, pp. 6–8). With the referendum in June 2011, the twenty-seven million residents voted and 97% of them said ‘yes’ in favour of the defence of water as belonging to the commons (Eligendo, Citation2011; Vercellone, Citation2020, p. 7).

Afterwards, the notion of commons and ‘demanio’ began to enter the door of legislative reform (Vercellone, Citation2020, pp. 7–8), while social movements continuously tried to make public infrastructure such as the former theatre and opera house as commons (Bailey & Marcucci, Citation2013). In this stream, ‘the Bologna Regulation on collaboration between citizens and the City for the care and regeneration of urban commons (Regolamento Sulla Collaborazione Tra Cittadini E Amministrazione Per La Cura E La Rigenerazione Dei Beni Comuni Urbani)’ was officially adopted by the city of Bologna in 2014. The Regulation outlined ‘how local authorities, citizens and the community (SMEs, nonprofits, knowledge institutions) can manage public and private spaces and assets together’ (The Urban Media Lab, Citation2014). It played a critical role in enabling people to be ‘resourceful and imaginative agents in their own right’, and the government to be ‘re-imagined as a hosting infrastructure for countless self-organized commons (Bollier, Citation2015).’

3.2. Infrastructure of urban commons

Infrastructure of urban commons revolves around the ‘mechanisms’ that facilitate collaborative efforts in defining, creating, managing, and utilizing resources for communal well-being. A fundamental principle is that people collaboratively are engaged throughout the entire process, being enabled to co-produce resources and establish systems for information and knowledge management (Mitlin, Citation2008). This engagement enables people to shape their collective subjectivity as commoners (Foster & Iaione, Citation2019).

Three important mechanisms can be identified, through which the enabling infrastructure works. First, people have created the infrastructure that underpins the reproduction and enhancement of their lives through a process of social collaboration, moving towards self-governance. Second, people are enabled to define the infrastructure and design its operating systems by themselves. Along the way, people try to dismantle and reconfigure – or even hack – existing infrastructure to improvise alternative flexible systems (De Lange & de Waal, Citation2019). Third, people can enable themselves to become commoners, transcending the dichotomy between providers and consumers of infrastructure. By performing these self-organizing practices, people accumulate experiences of the commons in which they work as designers of infrastructure who initiate the process from defining and organizing resources to devising innovative forms. In the end, the infrastructure of urban commons enables people to become active citizens living together with others.

Bin-Go, a financial commons in Seoul, South Korea, is an illustrative case (Han, Citation2019, Citation2021). Originating from a grassroots co-housing initiative launched in 2008 to address housing challenges in Seoul, Bin-Go has evolved into a peer-to-peer financing system. In this setup, participants can deposit (referred to as ‘pooling’ in Bin-Go's terms) their funds without limitations and subsequently borrow (termed as ‘usage’ in Bin-Go's lexicon) the pooled money to establish alternative spaces, regardless of the amount they contributed. Distinctively, Bin-Go appropriates the Korean rental system, jeonse, to convert capital (generating interest) into a common shared by all.Footnote2 As of 2023, Bin-Go boasts 467 individuals and 53 community members, including those involved in communal lands, co-housing projects, activist spaces, and community cafes.

Two facets from this case example need attention. Firstly, Bin-Go stands apart from interest-free or low-interest banks supporting vulnerable populations. Its users, primarily urban precarious youth, invest in Bin-Go due to their awareness of the existing financial system's unequal, opaque, and predatory nature. Therefore, despite outwardly resembling a conventional bank, participants understand that their funds follow a different financial trajectory, contributing to the expansion of the commons. In essence, Bin-Go, as a financial infrastructure, enables individuals to autonomously and collectively organize a financial flow not for capital gains but for the commons and to recognize themselves as commoners.

Secondly, Bin-Go has demonstrated the nitty-gritty practices of grassroots collaboration, actively defining, producing, and organizing the commons. The necessity for an alternative financial infrastructure arose during the co-housing experiment, leading to the creation of Bin-Go. Its development involved continuous improvisions based on collective studies, reflections, and applications, marked by a multitude of trial and error. Simultaneously, efforts have been made to maintain Bin-Go as a flexible and open structure, incorporating contingent elements rather than rigidifying it into a totalizing system.

3.3. Infrastructure ‘for’ urban commons

Enabling requires institutional and technical arrangements that play a role of ‘middleware’ for facilitating co-production of urban services and infrastructure at multiple levels. In this context, infrastructure needs to be understood as a means ‘for’ achieving the urban commons. For example, a poly-centric system can enable multiple entities or authorities at different scales to effectively manage and maintain common urban goods (Foster & Iaione, Citation2019). In such a system, norms and rules are created within the own domain of different groups while the government, both at central and local levels, remains an essential actor in facilitating and providing the necessary tools to govern shared resources (Frischmann, Citation2012; Hwang, Citation2023; Ostrom, Citation2010). It can also help the public sector to be open to innovation in providing, producing, and encouraging the co-production of essential goods and services at the local level (Ostrom, Citation2005).

With technological innovation, in the twenty-first century, infrastructure (e.g. new media technology, ICT) can contribute to enabling a poly-centric platform that facilitates open and multi-dimensional flow of information and resources among the wide range of actors (Kourtit, Elmlund, & Nijkamp, Citation2020) – e.g. city to citizen, citizen to citizen, and citizen to city. The essence of the open platform is to create an integrated communication system, through which the continuous processes of ‘exchanging’, ‘merging’, ‘sharing’, and ‘conflicting’ of ideas and resources take place both on and offline (Derrible, Citation2016; Lee, Babcock, Pham, Bui, & Kang, Citation2023; Poderi, Citation2019). The operation of such a platform can facilitate the process of identifying and tackling emergent, temporal and diverse social issues such as inequal accessibility to basic public services.

In Buiksloterham, an open innovation platform played a critical role of ‘middleware’ for effective management and maintenance of common urban goods. With a platform called Amsterdam Smart City (ASC), the municipal government, citizens, knowledge institute, and entrepreneurs together applied innovative approaches to sustainable and equitable production of urban services (e.g. mobility, water, and energy) (Cowley & Caprotti, Citation2019; Joss, Sengers, Schraven, Caprotti, & Dayot, Citation2019). A (networked) group was engaged in initiating and implementing urban experiments for sustainable living and circular neighbourhood (Gladek, van Odijk, Theuws, & Herder, Citation2016). For pilot projects including circular energy and mobility, the open platform enabled multi-directional information flow, knowledge exchange, resource sharing and distribution, and social learning at multiple levels, among multiple actors including companies, public agencies, self-builders, and knowledge institutes (Lee et al., Citation2023). Here, the binary notion of ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ are not strictly relevant (Luque-Ayala & Marvin, Citation2015).

The poly-centric decision-making needs to be supported by the foundational principles – to be set up by the public sector – e.g. specific regulation of social and environmental impacts, and open data and privacy protections (Dembski, Citation2013; Savini, Boterman, van Gent, & Majoor, Citation2016). However, it should be noted that if the regulations and procedures are too strict, the co-production process will only become more complex thereby demotivating the proactive engagement of diverse actors. In the case of Buiksloterham, no strict zoning and no fixed development plan exited while a set of basic rules and guidelines were established for what people wished to implement (Gladek et al., Citation2016). Furthurmore, specific ethics and social norms need to be established alongside for enabling the co-production of urban services through the collective governance. For example, since a variety of stakeholders need to learn to work together in an informal atmosphere, mutual trust before collective practices should become the norm.

Overall, ideally, with the technical and institutional arrangements, infrastructure should enable co-creative partnership to be formulated, in which multi-stakeholders can ‘co-design’, ‘co-fund’, ‘co-deliver’, and ‘co-evaluate’ products and services. In practice, infrastructure can play the role of middleware only if it is radically recognized and practiced as urban commons with the support of formal and informal rules agreed among multiple actors.

4. Towards enabling cities

We propose ‘enabling infrastructure’ as an instrument for the realization and operation of the enabling city. It should be noted that moving towards enabling cities is a difficult task, which necessitates challenging various modern dichotomies such as market-state, subject-object, consumer-provider, and society-technology. At the core, it requires the inclusion of not only physical objects, but also diverse people and their relationships with each other as part of the infrastructure. Also, the strict distinction between producers and consumers needs to be removed as everyone participates in commons-based production. Moreover, it is necessary to consider not only a technocratic issue – e.g. how to deploy the most advanced facilities and new digital technologies, but also a social issue – e.g. how to facilitate the innovation ecosystem in society. Overall, enabling cities can be created through social, technological, and cultural connections between complex relationships of diverse actors who participate in the systems of collective production and sharing.

We ultimately suggest that a city itself needs to become an enabling infrastructure. The city should function both as the commons and as a meta-infrastructure organizing other infrastructures into the commons level. This view goes beyond the idea of making individuals active citizens or merely giving them more access. What matters is that through the enabling infrastructure, people encounter others and become active and collaborative for their own lives of conviviality, the essence of what the urban commons is all about. Here, the city embodies the actual foundations and collaborative relations for citizens-initiated biopolitics, which aligns closely with Lefebvre's notion of the ‘right to the city’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The concept of ‘enabling’ was discussed in the 1980s and 90s with the intention of promoting more market-friendly state reforms by contracting out or consumerising the work of local government (Brooke, Citation1991; Smith, Citation2000; Wistow, Knapp, Hardy, & Allen, Citation1992). Since then, however, the term has expanded beyond the narrow sense of enabling, including more participatory values such as social solidarity, cooperatives, community government and partnerships. The concept of the ‘enabling city’ has a strong affinity with this broader approach to ‘enabling’.

2 Jeonse is a yearly or biannual housing lease contract unique to Korea (Kim, Citation2013). A tenant deposits a lump sum of cash, typically from 50% to 80% of the property value, at the beginning of the contract. The interest generated from the key-money during the contract is taken in place of monthly rent, while the deposited key-money is refunded when the tenant moves out but without interest. Landlords favoured joense as they could utilize the key-money as a source of funds to invest in housing, which has been ‘regarded as a superior investment compared to financial savings’ (Kim, Citation2013, p. 339). Joense system not only facilitated real estate speculation and encouraged ordinary Koreans to conduct financial practices to increase household assets but also imposed great pain on those who did not have access to a large sum of money. In this context, the co-housing experiment began by commoning key money.

References

- Alphandéry, C., et al. (2014). Abridged version of the Convivialist manifesto. [www document]. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://lesconvivialistes.fr

- Anand, N. (2017). Hydraulic city: Water and the infrastructures of citizenship in Mumbai. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Retrieved from https://www.dukeupress.edu/hydraulic-city

- Anand, N., Gupta, A., & Appel, H. (Eds.). (2018). The promise of infrastructure. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Retrieved from https://www.dukeupress.edu/the-promise-of-infrastructure

- Anguelovski, I., Shi, L., Chu, E., Gallagher, D., Goh, K., Lamb, Z., … Teicher, H. (2016). Equity impacts of urban land use planning for climate adaptation. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 36(3), 333–348.

- Bailey, S., & Marcucci, M. E. (2013). Legalizing the occupation: The Teatro Valle as a cultural commons. The South Atlantic Quarterly, 112(2), 396–405.

- Berlant, L. (2016). The commons: Infrastructures for troubling times. Environment and planning D: Society and Space, 34(3), 393–419.

- Bollier, D. (2014). Think like a commoner: A short introduction to the life of the commons. Gabriola Island, BC: New society Publishers.

- Bollier, D. (2015). Bologna, a laboratory for urban commoning. [www document]. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from http://www.bollier.org/blog/bologna-laboratory-urban-commoning

- Bollier, D. (2021). The Commoner’s catalog for changemaking: Tools for the transitions ahead. Schumacher Center for a New Economics. https://www.commonerscatalog.org/

- Borch, C., & Kornberger, M. (Eds.). (2015). Urban commons: Rethinking the city. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Brooke, R. (1991). The enabling authority. Public Administration, 69, 525–532.

- Burchardt, M., & Laak, D. (Eds.). (2023). Making spaces through infrastructure: Visions, technologies, and tensions (Vol. 16). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

- Camponeschi, C. (2010). The enabling city: Place-based creative problem solving and the power of the everyday [www document]. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://www.enablingcity.com/read

- Camponeschi, C. (2013). Enabling City 2: Enhancing creative community resilience. [www document]. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://www.enablingcity.com/read

- Chester, M. V., & Allenby, B. (2019). Toward adaptive infrastructure: Flexibility and agility in a non-stationarity age. Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure, 4(4), 173–191.

- Cowley, R., & Caprotti, F. (2019). Smart city as anti-planning in the UK. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(3), 428–448.

- Degens, P., Hilbrich, I., & Lenz, S. (2022). Analyzing infrastructures in the anthropocene. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 47(4), 7–28.

- De Lange, M., & de Waal, M. (2019). The Hackable city: Digital media and collaborative city-making in the network society. Singapore: Springer.

- Dembski, S. (2013). Case study Amsterdam Buiksloterham, the Netherlands: The challenge of planning organic transformation. Context Report, 2. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam. [www document]. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/1523659/124693_CONTEXT_Report_2.pdf

- Derrible, S. (2016). Complexity in future cities: The rise of networked infrastructure. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 21(1), 68–86.

- Dhakal, S., Zhang, L., & Lv, X. (2021). Understanding infrastructure resilience, social equity, and their interrelationships: Exploratory study using social media data in hurricane Michael. Natural Hazards Review, 22(4), 04021045.

- Eligendo. (2011). Referendum 12/06/2011 Area ITALIA. [www document]. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://elezioni.interno.gov.it

- Foster, S., & Iaione, C. (2019). Ostrom in the city: Design principles and practices for the urban commons. In B. Hudson, J. Rosenbloom, & D. Cole (Eds.), Routledge handbook of the study of the commons (pp. 52–62). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Fraser, N. (2022). Cannibal capitalism: How our system is devouring democracy, care, and the planet – and what we can do about it. London: Verso.

- Frischmann, B. (2012). Infrastructure: The social value of shared resources. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gladek, E., van Odijk, S., Theuws, P., & Herder, A. (2016). Transitioning Amsterdam to a circular city: Circular Buiksloterham vision and ambition. [www document]. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://buiksloterham.nl/

- Goh, B. (2023). 포함의 정치를 넘어 공동의 삶으로 - 시민사회에 대한 장애운동의 도전(2021∼2023) [Making communal life beyond the politics of inclusion – the disability movement’s challenge to civil society in Korea (2021∼2023)]. 경제와 사회 [Economy and Society], 139, 92–117.

- Graham, S. (2010). Disrupted cities: When infrastructure fails. London: Routledge.

- Graham, S., & Marvin, S. (2001). Splintering urbanism: Networked infrastructures, technological motilities and the urban condition. London: Routledge.

- Graham, S., & McFarlane, C. (Eds.). (2014). Infrastructural lives: Urban infrastructure in context. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Green, S. (2016). When infrastructures fail: An ethnographic note in the middle of an Aegean crisis. In P. Harvey, C. Jensen, & A. Morita (Eds.), Infrastructures and social complexity (pp. 289–301). London: Routledge.

- Han, D. K. (2019). Weaving the common in the financialized city: A case of urban cohousing experience in South Korea. In Y. L. Chen & H. Shin (Eds.), Neoliberal urbanism, contested cities and housing in Asia (pp. 171–192). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Han, D. K. (2021). Practicing urban commons between autonomy and togetherness: A genealogical analysis of the urban precariat movements in Tokyo and Seoul (Doctoral dissertation). London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Hardt, M., & Negri, A. (2009). Commonwealth. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Harvey, P., & Knox, H. (2015). Roads: An anthropology of infrastructure and expertise. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Hwang, J. T. (2023). Urban commons and the state: Critical reflections on Korean experiences. City, 27(5–6), 795–811.

- Jeong, Y. W. (2023, May 16). Jihacheolsiwileul balaboneun uli sahoeui du siseon [Two perspectives on the subway struggle]. KBS [www document]. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://n.news.naver.com/article/056/0011485597?type=editn&cds=news_edit

- Joss, S., Sengers, F., Schraven, D., Caprotti, F., & Dayot, Y. (2019). The smart city as global discourse: Storylines and critical junctures across 27 cities. Journal of Urban Technology, 26(1), 3–34.

- Kanoi, L., Koh, V., Lim, A., Yamada, S., & Dove, M. R. (2022). ‘What is infrastructure? What does it do?’: Anthropological perspectives on the workings of infrastructure(s). Environmental Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability, 2(1), 012002.

- Kim, J. (2013). Financial repression and housing investment: An analysis of the Korean Chonsei. Journal of Housing Economics, 22(4), 338–358.

- Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the people: How social infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civic life. New York, NY: Crown.

- Kostakis, V., & Bauwens, M. (2014). Network society and future scenarios for a collaborative economy. London: Springer.

- Kourtit, K., Elmlund, P., & Nijkamp, P. (2020). The urban data deluge: Challenges for smart urban planning in the third data revolution. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 24(4), 445–461.

- Larkin, B. (2013). The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42, 327–343.

- Lee, J., Babcock, J., Pham, S., Bui, T., & Kang, M. (2023). Smart city as a social transition towards inclusive development through technology: a tale of four smart cities. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 27(sup1), 75–100.

- Lefebvre, H. (1967). Le droit à la ville. L Homme et la société, 6(1), 29–35.

- Lefebvre, H. (2003). The urban revolution. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749j.ctt5vkbkv

- Luque-Ayala, A., & Marvin, S. (2015). Developing a critical understanding of smart urbanism? Urban Studies, 52(12), 2105–2116.

- McFarlane, C. (2010). Infrastructure, interruption, and inequality: Urban life in the global south. In S. Graham (Ed.), Disrupted cities: When infrastructure fails. London: Routledge. Retrieved from https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203894484-14/infrastructure-interruptioninequality-urban-life-global-south

- Metzger, J. (2015). The city is not a Menschenpark: Rethinking the tragedy of the urban commons beyond the human/non-human divide. In C. Borch & M. Kornberger (Eds.), Urban commons: Rethinking the city (pp. 22–46). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Mitlin, D. (2008). With and beyond the state — co-production as a route to political influence, power and transformation for grassroots organizations. Environment and Urbanization, 20(2), 339–360.

- Na, K. H. (2022, April 11). Ijunseog daepyonim neomu geobnaeji masibsio [Do not be intimidated, Mr. Lee]. Sisain [WWW document]. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://www.sisain.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=47240

- OECD. (2014). Private financing and governmental support to promote long-term investments in infrastructure. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2010). Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. American Economic Review, 100(3), 641–672.

- Oxford languages. (2023). Definition of infrastructure. Retrieved December 14, 2023, from https://google.com

- Plantin, J. C., & Punathambekar, A. (2019). Digital media infrastructures: Pipes, platforms, and politics. Media, Culture & Society, 41(2), 163–174.

- Poderi, G. (2019). Sustaining platforms as commons: Perspectives on participation, infrastructure, and governance. CoDesign, 15(3), 243–255.

- Rao, V. (2007). Proximate distances: The phenomenology of density in Mumbai. Built Environment, 33(2), 227–248.

- Savini, F., Boterman, W., van Gent, W., & Majoor, S. (2016). Amsterdam in the 21st century: Geography, housing, spatial development and politics. Cities, 52, 103–113.

- Schwenkel, C. (2015). Spectacular infrastructure and its breakdown in socialist Vietnam. American Ethnologist, 42(3), 520–534.

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Simone, A. (2004). People as infrastructure: Intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Public culture, 16(3), 407–429.

- Simone, A. (2021). Ritornello: “People as infrastructure”. Urban Geography, 42(9), 1341–1348.

- Smith, B. (2000). The concept of an ‘enabling’ local authority. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 18, 79–94.

- Star, S. L. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist, 43(3), 377–391.

- The Urban Media Lab. (2014). Bologna regulation on public collaboration for urban commons. [WWW document]. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://labgov.city/theurbanmedialab/bologna-regulation-on-public-collaboration/

- Unger, R. M. (2015). Conclusion: The task of the social innovation movement. In A. Nicholls, J. Simon, & M. Gabriel (Eds.), New frontiers in social innovation research (pp. 233–251). London: Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved from https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/27885.

- UN-Habitat. (2022). World cities Report 2022: Envisaging the future of cities assessing city performance. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

- Vercellone, A. (2020). The Italian experience of the commons: Right to the city, private property, fundamental rights. The Cardozo Electronic Law Bulletin, 1–37.

- Weber, A. (2015). Reality as commons: A poetics of participation for the Anthropocene. In B. David & H. Silke (Eds.), Patterns of commoning. Amherst, MA: The Commons Strategy Group. Retrieved from https://patternsofcommoning.org/reality-as-commons-a-poetics-of-participation-for-the-anthropocene/

- Wistow, G., Knapp, M., Hardy, B., & Allen, C. (1992). From providing to enabling: Local authorities and the mixed economy of social care. Public Administration, 70, 25–47.