ABSTRACT

The European Parliament (EP) has historically positioned itself as an advocate of social Europe. Although the EP has been repositioned from an agenda-setter to a co-legislator, increasing polarisation and politicisation have potentially made agreements on social issues more challenging. This article contributes to the debate on increased politicisation within the EP and its consequences for social Europe, as well as literature on politicisation management, by analysing how politicisation manifests itself and is managed during the committee stage of the EP legislative process. The article asks, to what extent is social Europe politicised within the EP during the committee amendment phase, and how is such politicisation managed at the committee level? Empirically, it analyses three recent directives: the Work-Life Balance Directive (2019), the Minimum Wage Directive (2022) and the Pay Transparency Directive (2023). It finds that the considerable politicisation during the amendment phase is managed by separate, yet simultaneously occurring mechanisms of technocratic filtering and normative filtering. This filtering steers the EP towards a stronger position of social Europe than the initial political division and opposition would suggest while aligning this position to the logic and framing of the Commission’s proposal rather than aiming for a radical expansion of the scope of social Europe.

Introduction

Integration with social Europe is somewhat intermittent. According to the current literature, we can identify three periods of intense activity – the early 1970s, the Delors era and the Lisbon Strategy (broadly from the late 1990s until 2005) (Leibfried, Citation2010). In addition, we can add the current period, which began with the launching of the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR) in 2017 by the Jean-Claude Juncker Commission (2014–2019) and has continued under that of Ursula Von der Leyen (2019–). Both Commissions committed themselves to implementing the EPSR, with the Von der Leyen Commission, along with the Council and the European Parliament (EP), agreeing to the 2021 Porto Action Plan. This renewed momentum has seen the revision of existing directives (e.g., Written Statement Directive), proposals and agreements on other issues (e.g., minimum wage, pay transparency) and new Council Recommendations (e.g., Child Guarantee).

Within the evolution and debate on social Europe, the EP holds a unique position. Not only is the EP the EU’s only directly elected institution and held accountable by the electorate for developments within the integration process, but it has also positioned itself as both an advocate and defender of social Europe in the context of a more cautious and potentially conservative Council (Ahrens & Abels, Citation2017; Copeland & Daly, Citation2012; Roos, Citation2021). Meanwhile, the EP has experienced a continued increase in its powers and, since the Lisbon Treaty (2009), has been able to reposition itself from being an agenda-setter to a co-legislator (Ripoll Servent, Citation2018). The increase of powers has taken place at a time in which the process of European integration – and thereby the EP – has experienced increased politicisation, visible in the polarisation of opinions about integration and specific EU policies. The politicisation has potentially made agreements and policy compromise more challenging, not least because of the erosion of support for the main centre political groups and the increased presence of the more radical left and right and Eurosceptic positions in the EP (Crum, Citation2020; Ripoll Servent, Citation2019). It has also required EU actors, including the EP, to engage in strategic politicisation management that either tends towards the politicisation or depoliticisation of decision-making, behaviour, and policy outcomes (Bressanelli et al., Citation2020; Schimmelfennig, Citation2020).

Within the existing literature on the EP and social Europe, scholars have shown the multiple co-existing political tensions on social issues. The finding is that while increased politicisation and polarisation may hamper the development of a stronger social Europe, the multiple tensions may also provide the basis for new political alliances and coalitions (Crespy & Gajewska, Citation2010; Vesan & Corti, Citation2019). The broader EP literature too has drawn attention to increasing conflicts and cleavages across policy fields, often based on Roll Call Votes (RCV) (e.g., De Ville & Gheyle, Citation2024; Hix et al., Citation2007). Meanwhile, this literature points to a set of operational issues which often help to manage politicisation within the institution, such as the technocratic nature of the EP and the culture of broad political compromises (Brack & Costa, Citation2018; Kreppel & Hix, Citation2003). In sum, even when social Europe is a contested issue, the room for politicisation regarding social policy in the EP may be limited. As suggested by Brack and Costa (Citation2018, p. 66): ‘The EP appears more and more like a non-conflictual and non-political institution, in which MEPs search for consensus through expertise and, then, try to influence the Commission and the Council using a technical rather than a political discourse.’ Nevertheless, politicisation within the EP can be a positive development, as it provides opportunities for MEPs to be perceived as shaping policy in a decision-making process that is often perceived as being technocratic.

This article further contributes to the fledging debate on the increased politicisation within the EP and the consequences of such for social Europe. It does so by analysing the mechanisms through which politicisation manifests itself and is managed during the committee stage of the EP legislative process. Committees are the EP’s legislative backbone, where legislation is shaped and compromises between political groups achieved (Settembri & Neuhold, Citation2009). Committees are at the forefront of politicisation and politicisation management in the EP and in the case of social Europe, such management is centred around the EP’s Committee on Employment and Social Affairs (EMPL). We ask two questions: first, to what extent is social Europe politicised within the EP during the committee amendment phase?; and second, how is such politicisation managed at the committee level? Empirically, we analyse three directives which are part of the implementation of the EPSR: Work-Life Balance Directive (2019), Minimum Wage Directive (2022) and Pay Transparency Directive (2023). Our data consists of policy documents, including draft reports, amendments and texts adopted by the committee. Our qualitative and interpretative theoretical and methodological approach is geared toward the development of new concepts in a dialogue with a systematic empirical analysis. Our contribution to the existing literature is two-fold. First, through focusing on the amendment phase of the committee proceedings and coining the term input politicisation, we draw attention to an under-researched dimension of politicisation in the EP legislative process not visible in the research which focuses on RCVs at the plenary stage. Second, our analysis of institutional politicisation management during the committee negotiations adds a normative dimension to debates about politicisation management within the EP that have often focussed on technocratic aspects of the institution. By doing so, the analysis provides further insight into the impact of politicisation on social Europe within the EP and deepens our understanding of the role and function of the institution and its committees in the face of potential dissensus.

We find considerable input politicisation regarding social Europe during the amendment phase of the EP committee process, both for and against the Commission's proposals. Divisions between the MEPs and the political groups suggest potential difficulties in obtaining a compromise and consensus towards a common institutional position. Nevertheless, politicisation is managed by separate, yet simultaneously occurring, mechanisms of technocratic filtering and normative filtering. Technocratic filtering aligns the EP position with the logic and framing of the Commission’s proposals, with the EP position often focussing on the ‘numbers’ of specific provisions rather than the expansion of the scope and rationale of the proposal. Meanwhile, as a result of normative filtering, the political consensus that emerges from the committee advocates for a significantly stronger position on social Europe than the initial political division would suggest. Whilst increased politicisation requires a technocratic response to manage political division, such technocracy does not undermine the EU’s position as a defender of social Europe, albeit it does limit the potential for a more radical approach to the policy field as it remains within the logic of the political economy of European integration (cf. Elomäki, Citation2023). The findings highlight the importance of institutional norms within the EP during the policy process and how tensions between and within the political groups are managed and resolved. In the short term, the increased politicisation within the EP does not necessarily challenge what has become established norms and values within the institution.

This article proceeds as follows. The second section explores our conceptual framework for analysing politicisation and politicisation management in the EP, while the third section outlines our case study selection, the data used and our methodology. The fourth section outlines our results regarding patterns of input politicisation for the three directives, based on the amendments submitted during the committee process. This is followed by our analysis of the adopted committee reports, with a view of how politicisation was managed in the committee, and the consequences for its position. Within our conclusion we reflect further on our findings.

Theorising politicisation and politicisation management in the European Parliament

Both the process of European integration and EU studies have taken something of a politics turn. As the politics of European integration has become more politicised, academic attention has shifted to analysing the impact of politicisation on European governance as both an enabler and constraint of integration. Over the last three decades integration has shifted from an elite-driven, technocratic, and depoliticised process, to one in which political contestation has become commonplace. As the process of European integration has expanded into ‘core state powers’, such as monetary policy, migration and security, political actors and interest groups have mobilised to contest EU supranationalism, thereby contributing to processes of politicisation (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2014; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009). Since the Eurozone crisis, social Europe has been the subject of increased politicisation and contestation, as decision-making within the Ordinary Legislative Procedure (OLP) has received greater publicity, scrutiny and a tendency for high-level disagreements between the three EU institutions. Meanwhile, the backlash against the EU since its handling of the Eurozone crisis has been interpreted as requiring a different type of European integration and one that should include ‘more Europe,’ including social Europe (Copeland, Citation2022; Vesan et al., Citation2021).

Following De Wilde et al. (Citation2016), the EU studies literature often defines politicisation as the growing domestic salience of European governance, the polarisation of opinions on EU issues, and the expansion of actors and audiences attentive to EU affairs. While most scholars have discussed politicisation as a domestic phenomenon, politicisation as polarisation is a feature across the EU’s multi-level political space and the EU’s institutions, including the EP (e.g., Wendler, Citation2019). Such polarisation signifies the occupation of more extreme positions – either in favour of or against different aspects of EU governance – and/or a depletion of neutral, ambivalent, or indifferent attitudes (De Wilde et al., Citation2016, p. 6). Previous research on politicisation within the EP has drawn attention to how the increased representation of MEPs from outside of the main centrist groups, the European People’s Party (EPP) and the Socialists & Democrats (S&D) has disrupted parliamentary politics (Crum, Citation2020). The subsequent polarisation of opinions has been visible in Eurosceptic contestation as well as through the increasing divisions between and within the political groups visible in votes, debates and committee work across policy fields (e.g., Brack & Behm, Citation2022; Börzel et al., Citation2023; Hix et al., Citation2007). Social policy too is a contested issue within the EP, despite its reputation as a progressive social actor (e.g., Crespy & Gajewska, Citation2010; Michon & Weill, Citation2023; Vesan & Corti, Citation2019). In addition to cleavages between political groups along the left-left/right, pro-/anti-EU and GAL-TAN axes, some tensions cut across the groups. Vesan and Corti (Citation2019) have argued, for instance, that the debate on the EPSR revealed tensions between creditor and debtor countries as well as high-wage/high-welfare and low-wage/low-welfare countries. Conflicts revolved around multiple issues ranging from the content of social policy, the locus of authority and the boundaries of responsibilities. In addition, work by Ahrens et al. (Citation2022), Berthet (Citation2022) and Kantola (Citation2022) highlights increasing political polarisation on gender equality and human rights both between and within the political groups owing to the increased presence of anti-gender MEPs in the EP.

The literature on politicisation management provides another approach to politicisation within EU institutions. Schimmelfennig (Citation2020) and Bressanelli et al. (Citation2020) use this concept to refer to the politicising or depoliticising strategies that EU actors use vis-à-vis potential domestic politicisation. Politicisation strategies entail, among other things, opting for policy designs prone to create controversy, and rhetoric that does not hide behind legalistic and technocratic language (Schimmelfennig, Citation2020, pp. 348–349). In our view, the concept of politicisation management is also a useful tool for analysing how EU institutions respond to internal polarisation and the politicisation strategies of actors within. The literature on the EP has highlighted the growing technocratic nature of the institution as a strategy to manage internal politicisation. The EP has been characterised as a ‘working parliament’ that focuses on passing legislation and gives a smaller role to public debate and deliberation (Brack & Costa, Citation2018; Lord, Citation2018). Over the years, parliamentary work has been shaped in ways that have allowed the EP to intervene more efficiently in the EU decision-making process while constraining deliberation and thereby possibilities for politicisation (Brack & Costa, Citation2018). A second factor limiting politicisation within the EP relates to the long-held tradition of compromise and consensus within the institution, where decision-making has been dominated by compromises between the two largest groups, the centre-right EPP and the centre-left S&D (Hix et al., Citation2007; Kreppel & Hix, Citation2003; Novak et al., Citation2021; Ripoll Servent, Citation2018). The rise of Euroscepticism and other shifts in the EP’s composition (i.e., in the 2019–2024 term the S&D and the EPP no longer had a majority of seats) have required even broader pro-EU majorities (Crum, Citation2020; Ripoll Servent, Citation2019). Simultaneously, the EP’s empowerment has increased the incentives of political groups and MEPs to compromise and be seen as responsible legislators (Ripoll Servent, Citation2015; Bressanelli & Chelotti, Citation2018).

We make two conceptual contributions to the debates about politicisation and politicisation management within the EP, which also constitute the conceptual lens for our analysis. First, the research on politicisation in the EP has focused on RCVs, even if qualitative analyses of politicisation have proliferated in recent years (e.g., Ahrens et al., Citation2022; Elomäki, Citation2023; Petri & Biedenkopf, Citation2021). Notwithstanding the importance of RCV-analyses for understanding polarisation within the EP, empirically they only capture one of the two dimensions regarding politicisation within the EP legislative process. That is, analysing RCVs is output-oriented in that it captures the extent to which MEPs and political groups remain satisfied/dissatisfied with a proposed directive. The second, less studied dimension, is input-oriented and relates to the extent to which there is politicisation during the proposing of amendments to the Commission’s proposals at the committee stage. Studying input politicisation captures whether and how MEPs and the political groups politicise the Commission’s proposal, that is, the extent to which they aim to strengthen or weaken it and how controversial their alternative proposals are. In addition, it captures polarisation between and within political groups at this early stage of the EP legislative process and allows identifying the most polarising themes. In our view, input politicisation requires further examination both in the context of politicisation in the EP, and the specific debate on social Europe. In line with previous research, we expect to see politicising amendments among the elected actors across the political spectrum, but in particular among challenger parties and parties that identify on the GAL/TAN dimension (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009; Schimmelfennig, Citation2020).

Second, while EP literature has highlighted the growing technocratic nature of the institution to manage increased politicisation, this remains an insufficient perspective regarding social Europe. The literature on social Europe has highlighted the historic reputation of the EP as an advocate for social Europe, which is political in and of itself (Copeland & Daly, Citation2012; Roos, Citation2021). We propose that the EP’s management of internal politicisation in the field of social Europe has both technocratic and normative aspects and that it involves two simultaneous mechanisms: technocratic filtering and normative filtering. In line with historical institutionalism, these mechanisms highlight the importance of institutional norms and values (Hall & Taylor, Citation1996; Thelen & Steinmo, Citation1992). Technocratic filtering is connected to the nature of the EU policy-making process, and the dynamics within the EP and between the EU institutions. We expect this mechanism to align the EP’s position on a proposed directive with the logic and frame of the Commission’s proposal and exclude views that radically depart from it. This approach maximises efficiency and the EP’s influence (Brack & Costa, Citation2018, p. 66). We also expect this mechanism to constrain input politicisation and encourage the MEPs, at least from the centrist political groups, to make relatively technical adjustments to the Commission’s proposals instead of fundamentally challenging or expanding them. The second mechanism, normative filtering, highlights the importance of institutional identities and how they are constructed systematically around individual institutions. We expect the political consensus which emerges from the committee to advocate for a significantly stronger position on social Europe than the initial political division would suggest. Both mechanisms therefore draw attention to how actors’ strategies are shaped by the institutional context, the way it structures power relations among them, and how it shapes the goals political actors pursue (Bulmer & Burch, Citation1998; Hall & Taylor, Citation1996; Thelen & Steinmo, Citation1992).

Cases, data and methods

We analyse three legislative case studies during the Juncker and von der Leyen Commissions, which form part of the implementation of the EPSR and relate to chapters I (equal opportunities and access to the labour market) and II (fair working conditions). The Directive on Work-life Balance for Parents and Carers, adopted in 2019, introduced new forms of care-related leave (paternity leave, carers’ leave), made a larger share of parental leave non-transferable between parents, and extended workers’ right to request flexible working time arrangements. The Directive on Adequate Minimum Wages in the European Union, adopted in October 2022, requires member states that have a minimum wage to adopt processes that ensure its adequacy and requires increases to collective bargaining coverage. Finally, the Directive to Strengthen the Application of the Principle of Equal Pay for Equal Work or Work of Equal Value between Men and Women through Pay Transparency and Enforcement Mechanisms, adopted in April 2023, requires companies to share information on salaries and take action if their gender pay gap exceeds a certain limit, and includes provisions on compensation for victims of pay discrimination. The three cases are relatively similar, relating to the labour market and key issues regarding pay and working conditions. They include increased obligations and/or costs for employers and businesses and improve workers’ rights, but only the Work-Life Balance Directive involves increases in public spending, albeit somewhat minimally. All directives establish minimum standards and entail flexibility rather than a strict harmonisation of approach. The similarities between the directives reflect the EU’s legal competence in employment policy and thereby accurately capture the dynamics of politicisation within the EP. Meanwhile, the cases extend across two parliamentary terms with different decision-making logics, which enables capturing shifts that may have occurred over time, even though this is not the focus of the article.

presents an overview of the key actors and processes regarding the three cases. All three directives were debated in the EMPL Committee. The Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality (FEMM) functioned as an associated committee for the Work-life Balance Directive and shared the responsibility for the Pay Transparency Directive. Both committees are left-leaning, progressive committees, that listen to trade unions more than employers and may not fully reflect the EP’s overall stance (Elomäki & Gaweda, Citation2022; Diogini, Citation2017; Yordanova, Citation2009). Different political groups were in charge of each directive: the EPP for the Work-life Balance Directive, the EPP and the S&D for the Minimum Wage Directive, and Renew Europe and the Greens/EFA for the Pay Transparency Directive.

Table 1. Overview of the three directives in the EP committee stage.

Our analysis focuses on input politicisation and politicisation management at the committee stage of the EP legislative process. During the committee stage, the rapporteur(s) submits a draft report on the Commission’s proposal. This is followed by the amendment phase, where committee members (and other MEPs) are free to submit amendments to the proposal, either individually, together with other MEPs or as political groups. During the negotiation phase, the rapporteur(s) and shadow rapporteurs from other political groups negotiate a report constituted of amendments to the Commission’s proposal, which is voted on by the committee before going to the plenary for a vote by all MEPs. The adopted text constitutes the EP’s position in interinstitutional negotiations. The empirical data consists of the draft reports, the amendments submitted during the amendment phase, and the reports adopted by the committee (i.e., the amendments that the committee proposes to make the Commission’s proposal). We do not map political cleavages and coalitions nor interrogate the negotiation dynamics during the agreement of the adopted oppositions (for the former see Crespy & Gajewska, Citation2010; Vesan & Corti, Citation2019; and for the latter see Elomäki, Citation2023).

To analyse these documents, we applied a three-dimensional coding framework: (1) the scope of action (i.e., does the amendment strengthen, weaken or clarify the proposal), which captures the general direction of politicisation vis-à-vis Commission’s proposal; (2) issues and themes (e.g., gender equality, social partners and collective bargaining), which captures the most salient issues and themes; (3) the political group from which the amendment was proposed, which captures polarisation between and within the political groups regarding the scope of action and the issues. To analyse the extent of politicisation within the amendments vis-à-vis the Commission’s proposal, we complemented the code-based content analysis with discursive, interpretive policy analysis (e.g., Bacchi, Citation2009) to assess the extent to which the strengthening and weakening amendments depart from the Commission’s proposal and the intensity of the policy discourse. In other words, we identified amendments that either moved beyond the frame of the Commission’s proposal or proposed a significant change within the frame.

In the analysed time period, the main political groups were the centre-right EPP, centre-left S&D, liberal Renew Europe (ALDE in the 2014–2019 term), the radical right ID (ENF in the 2014–2019 term), Greens/EFA, the conservative ECR, and the Left (GUE/NGL). In addition, the radical right EFDD group existed in the 2014–2019 term, and non-attached MEPs (NI) made amendments in the 2019–2024 term (on political groups, see Kantola et al., Citation2022.). While we are attentive to polarisation within the groups too, it was not possible to systematically code and analyse the amendments based on the nationality of the MEPs, due to the different practices of amendment-making. Some political groups mainly submit amendments as a group (Greens/EFA) and in some, most committee members submit common amendments (S&D). Within the other political groups, MEPs submit amendments individually, by nationality, or by a small group of MEPs from different nationalities. The empirical data was analysed with ATLAS.ti. All three co-authors were involved in the formulation and application of the coding framework (see Annex). Each co-author took the lead on one case study, but we discussed any difficulties and cross-checked a random sample of each other’s coding. The systematic coding allowed for quantified comparisons across the political groups and the three cases.

Patterns of input politicisation during the amendment phase

Work-life balance directive

Based on the committee amendment phase, the Work-Life Balance Directive was the most consensual of the three cases. The Commission’s proposal was already relatively ambitious: it proposed new forms of leave for fathers and carers, called for remuneration at the level of sick pay, and extended non-transferability for parental leave from one to four months. The political groups and the MEPs were overall orientated towards strengthening the Commission’s proposal with more than half of the 679 amendments (52 per cent) in this direction, whereas 25 per cent were for weakening and 23 per cent for clarifying. There was thus an extensive input politicisation for a stronger social Europe, but political polarisation and division remained limited.

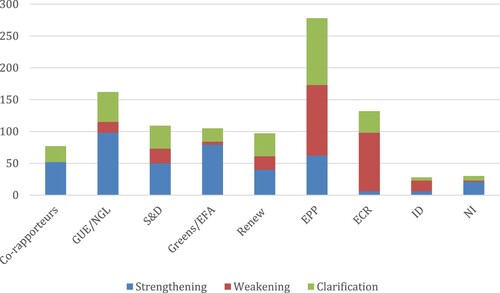

The Greens/EFA, S&D and GUE/NGL took the most consistent strengthening approach to the proposal (81, 69 and 66 per cent, respectively) (see ). Perhaps surprisingly, also the ALDE group that previous research has shown to be divided on social issues (Vesan & Corti, Citation2019) and the radical right EFDD – mainly thanks to the socially progressive Italian M5S delegation – took an overall strengthening stance (61 and 73 per cent, respectively). Social rights and intersectionality were the most salient themes for those aiming to strengthen the proposal. Whereas the Commission had proposed remuneration at the level for sick leave pay, GUE/NGL, Greens/EFA and some S&D and EPP MEPs asked for full remuneration for each type of leave. S&D, GUE/NGL, Greens/EFA and some EPP MEPs also called for paternity leave to be mandatory. The left-leaning groups also tried to broaden the categorisation of individuals able to enjoy the new rights by requesting that different forms of leave should be available irrespective of the length or status of an employment relationship. From an intersectionality perspective, these groups strengthened the directive through inclusive language and provisions that considered parents and children with disabilities, same-sex couples, and different types of family situations.

Figure 1. Committee amendments on the Work-Life Balance Directive by political group and the scope of the amendment.

As significant as many of these amendments were in that they attempted to increase levels of protection and bring new people under them, often in ways that were bound to be polarising, they mainly remained within the logic of the Commission’s proposals. The already ambitious proposal, as well as the shadow of the withdrawn Maternity Leave Directive, where the EP’s demands had made it difficult to compromise with the Council (Ahrens & Abels, Citation2017; Diogini, Citation2017), likely decreased efforts to radically broaden the directive. Notably, there was a pronounced silence around maternity leave. With very few expectations (individual MEPs from the EPP, Greens/EFA and GUE/NGL), MEPs did not use the Work-Life Balance Directive as a wedge to force the Commission to put maternity leave onto its agenda.

Politicisation against the directive was surprisingly scarce, given that many of the Commission's proposals were likely to be controversial for some political groups and member states. The ECR aimed most consistently at weakening the proposal, with more than half (53 per cent) of its amendments in this direction. However, this figure is low compared to the other two cases, and a significant share of ECR amendments (28 per cent) even aimed at strengthening the proposal, illustrating that in the 2014–2019 term, the group was not yet outright opposed to a stronger social Europe. The radical right ENF made hardly any amendments. The directive was internally polarising for the EPP, but a larger share of the amendments was for weakening (41 per cent) rather than strengthening (35 per cent) or clarifying (24 per cent). Efforts to radically weaken the proposal were rare. ECR and EPP MEPs by and large accepted the creation of the new forms of leave but contested their length, remuneration level, flexibilities, as well as who has access to leave. For instance, although almost all EPP and ECR MEPs accepted that family leave should be compensated, they proposed lower compensation levels than the Commission or wanted to leave it to member states to decide. EPP and ECR MEPs also made efforts to weaken bindingness and enforcement. Most radically, a Dutch EPP MEP proposed, evoking subsidiarity, that the directive would only be a recommendation for the member states. The EPP and the ECR also took the perspective of companies: they stressed the need not to disrupt the functioning of companies but also considered the needs and rights of employees through provisions aiming to prevent ‘abuse’ of leave and flexible working arrangements. Finally, the amendments confirm that gender and gender equality are polarising issues within the EP (Berthet, Citation2022; Kantola, Citation2022). ECR MEPs put forward anti-gender narratives and essentialist views on gender roles. The EPP MEPs too stressed ‘traditional values’ and preferred references to women and men over gender, and some GUE/NGL MEPs stressed traditional gender roles and opposed non-transferable parental leave. ()

Minimum wage directive

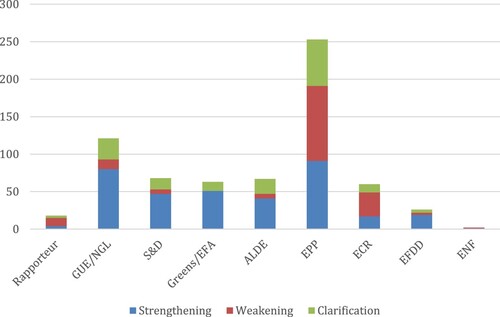

In total 918 amendments were tabled at the committee stage for the Minimum Wage Directive and there was considerable politicisation in the sense of polarisation both within and between the political groups with 38 per cent of amendments for strengthening the directive, 31 per cent for weakening, and 31 per cent for clarification. 72 per cent of the amendments tabled by the Greens/EFA were to strengthen the proposal, with the respective figure for the GUE/NGL being 62 per cent. The radical right groups were against the proposal with 70 per cent of the amendments from the ECR and 66 per cent of those from ID were for weakening. Opposition to social Europe among the radical right had thus increased in comparison to the Work-Life Balance Directive and the 2014–2019 term. The main centre political groups were more divided and internally polarised with 46 per cent of the proposals submitted by the S&D and 41 per cent by Renew to strengthen the proposal, and 40 per cent of those by the EPP to weaken it.

In terms of strengthening the Commission’s proposal, most amendments followed the Commission’s logic and proposed changes to the numbers, such as the calculation of minimum wages, the application and monitoring of minimum wages, and improving the coverage of collective bargaining. The Commission had included the possibility of varying minimum wages between workers e.g., regional variations, which left-leaning political groups were keen to limit or remove, including the S&D. Meanwhile, they were also opposed to the possibility of employers applying deductions from minimum wages, such as those for work-related expenses. When it came to setting minimum wages, the Greens/EFA and the GUE/NGL called for minimum wages to be set at levels to eliminate poverty and to reflect any changes to the cost of living. They also called for a strengthening of the enforcement mechanisms at member state and regional levels, including greater monitoring and data collection for minimum wages to maximum coverage for workers, as well as sufficient resources for labour inspectorates to carry out their functions in the context of enforcing the directive. A final issue for the strengthening of the Commission’s proposal related to collective bargaining. The Commission’s proposal included the provision of improving rates of collective bargaining across the EU – in particular where they fell below 70 per cent of workers – as well as strengthening the role of collective bargaining. The Greens/EFA and the GUE/NGL aimed for a higher level of coverage to include up to 90 per cent of workers, albeit the S&D did not propose such ambitious amendments.

As with the strengthening amendments, those aiming to weaken the Commission’s proposal remained within the Commission’s frame and often juxtaposed those from MEPs aiming to strengthen the Commission’s proposal. In this regard, there was an explicit connection to the EU’s competitiveness agenda and the importance of minimum wage levels for the creation of jobs and growth. This is very familiar territory for the right of the political spectrum and was one followed by EPP and ECR MEPs, albeit the latter was much more consistent. Proposed amendments included greater flexibility in the determination of minimum wages, greater variations within a member state, and possible deductions to minimum wages. Further flexibility was introduced by EPP MEPs who called for exemptions to minimum wages for small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as strengthening the link between minimum wages and labour productivity. Further flexibility was also proposed relating to collective bargaining and monitoring the implementation of the directive. MEPs from both the EPP and the ECR considered the Commission’s proposal to increase rates of collective bargaining to be too ambitious and submitted amendments focused on such provisions being flexible, rather than binding. In addition, any monitoring of minimum wages and collective bargaining coverage was to be minimal, with little or no obligations to gather data and to report on the implementation and coverage of the directive at the EU level. In recognition of their systems of collective bargaining and wage determination, EPP and ECR MEPs from Austria, Denmark and Sweden called for an opt-out from the directive for these member states.

Pay transparency directive

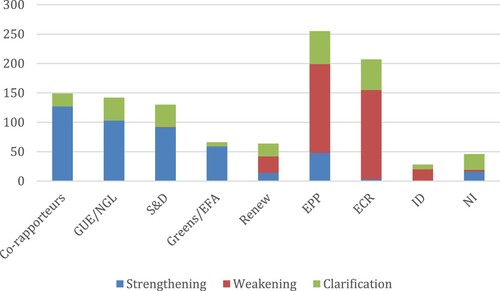

The Pay Transparency Directive was the most politicised of the three cases in the context of MEP’s efforts to strengthen and weaken the Commission’s proposal. The directive was also clearly polarising among the political groups, but the groups were more unified in their strengthening or weakening stance than in the other two cases. There were altogether 1090 amendments – most in the three cases – of which 42 per cent aimed at strengthening the proposal, 33 per cent weakening it, and 25 per cent clarifying. The Commission’s proposal included elements that were prone to initiate polarisation and division on ideological and national grounds, such as the very topic matter of gender equality, the connection to collective bargaining, and new responsibilities for companies. Simultaneously, the draft report by the Greens/EFA and Renew set the agenda strongly towards strengthening the proposal, and the involvement of the progressive FEMM committee led to many amendments that aimed to radically expand the scope of the directive.

The Greens/EFA, GUE/NGL and the S&D took the most coherent strengthening stance: 89, 73 and 70 per cent of their amendments aimed for a stronger or broader directive (see ). The most salient themes in these amendments related to company responsibilities, gender equality, the participation of social partners, and intersectionality. The groups on the left and some EPP and Renew MEPs wanted to add new requirements for companies, such as gender action plans, and bring more companies into the scope of the directive. The co-rapporteurs, supported by the Greens/EFA and S&D MEPs, also tried to broaden the scope of the directive from sex-based to gender-based discrimination and to make the language of the proposal more attuned to gender diversity. MEPs across political groups made amendments to give the social partners a larger role in the design and implementation of pay transparency measures.

Figure 3. Committee amendments on the Pay Transparency Directive by political group and the scope of the amendment.

Most of the strengthening amendments followed the Commission’s logic in the sense that they focused on changing the numbers included in the proposal, such as the size of companies covered, and the size of the pay gap in a company needed to trigger corrective measures. However, they also involved more explicitly politicising efforts to broaden the scope of the directive. Next to introducing the idea of gender-based discrimination, these revolved around the concept and idea of intersectionality, that is, that systems of discrimination and inequality overlap and are interconnected. While the Commission had included language about intersectional discrimination in the recitals, the co-rapporteurs, together with Greens/EFA, S&D and GUE/NGL MEPs, added a definition of intersectional discrimination to the articles of the directive and made this idea visible in its provisions. As could be expected, the strengthening amendments by the Greens/EFA and GUE/NGL tended to be the most far-reaching, but also centrist MEPs from left and right proposed significant expansions.

Simultaneously, a slightly larger share of amendments aimed at weakening the directive than for the other two cases, illustrating a relatively strong politicisation against the Pay Transparency Directive. As could be expected, the ID and the ECR took the most consistent weakening stance: more than 70 per cent of their amendments aimed at weakening the directive and hardly any strengthening it (). While internal polarisation could again be perceived within the EPP and Renew Europe, both groups took a much stronger weakening stance than in the other two cases: 59 per cent of EPP amendments and 44 per cent of Renew amendments were for weakening, whereas only 19 per cent (EPP) and 22 per cent (Renew) aimed to strengthen the proposal. In both groups, the (shadow) rapporteurs and FEMM members took a strengthening stance, a factor that likely pushed dissenting MEPs to express their views. Within the EPP, the opposition focused on the Austrian, German, Swedish and Danish delegations and, similarly to the Minimum Wage Directive, was driven by the understanding that the Directive interfered in the national collective bargaining system.

The most salient themes for the opposing political groups and MEPs were company responsibilities, gender equality and questions related to bindingness. They tried to weaken the obligations for companies proposed by the Commission, including by raising the size of the companies covered by the directive to 500 or even 1000 employees as proposed by EPP MEPs, or by limiting the application to European companies (a type of limited company) as proposed by the ECR. The increasingly anti-gender ECR tried to remove any references to the concept of gender from the draft text, with opposition to gender and gender equality having a more visible role in the ECR’s politicisation against social Europe than in the case of Work-Life Balance Directive. In addition, the opposing MEPs tried to make the directive less binding, for instance by making it more difficult to take cases of pay discrimination to court than the Commission had initially proposed. The most far-reaching politicisation against social Europe came, perhaps against our expectations, from within the EPP. Some EPP MEPs proposed full rejection of the directive or that the directive should not apply in countries with collective bargaining systems, or to companies that participate in collective bargaining.

Managing politicisation in the adopted reports

Social Europe was thus politicised at the amendment phase of the EP committee proceedings by both its supporters and opponents. Moreover, social Europe was a polarising issue between and within the political groups but the extent of polarisation varied by the proposed directive. Analysing the reports adopted by the committee reveals the extent to which the politicisation for and against social Europe is featured within the political compromise and how polarisation and division are managed.

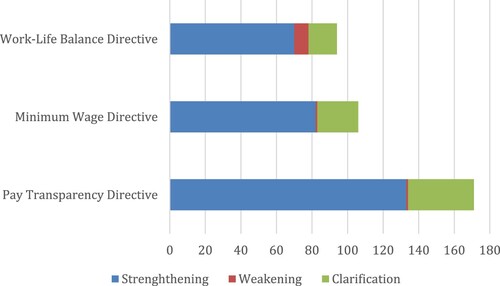

The results of applying the coding framework to the adopted reports can be seen in . In all three cases, the adopted reports that constituted the EP’s position in interinstitutional negotiations overwhelmingly strengthened the Commission’s proposal. Given the extent of input politicisation and polarisation during the amendment phase, the consistency of the political compromise and a strong normative position towards a more expansive vision of social Europe is striking. The numerous proposals to weaken the directives were either completely excluded from the adopted reports or reduced to descriptive sentences with little impact on specific provisions. In other words, the opposing politicisation around social Europe was normatively filtered out in the committee negotiations and did not significantly affect the EP’s position on the directives. Opposing views regarding the EU’s competencies on social issues, and the concern for the costs and burdens that the proposed directives could impose on companies were hardly visible, suggesting that compromises were not representative of the divergent positions within the EP, including those often found within the EPP and the liberals.

Figure 4. Amendments in adopted committee reports for the three directives by directive and the scope of the amendment.

While the adopted reports took a strong normative position in favour of social Europe, they also continued with the technocratic approach evident during the amendment phase. In other words, the outcome of committee negotiations was also affected by the mechanisms of technocratic filtering. The more radical ideas visible in amendments by the GUE/NGL and Greens-EFA and some S&D and EPP MEPs that broadened the scope of the directives were absent within the adopted reports. In the case of the Work-Life Balance Directive, this meant proposals for making paternity leave mandatory and references to maternity leave. Regarding the Minimum Wage Directive, the GUE/NGL proposal for a compulsory level of remuneration at 60 per cent of the median wage across the Eurozone came nowhere near being included within the political compromise. In all three cases, almost all the strengthening amendments in the adopted reports followed the logic of the Commission’s proposal, focusing on changes to the numbers. This is not to say that the EP’s amendments were insignificant, but rather they follow a particular approach. For example, in the case of the Minimum Wage Directive, the adopted report pushed for member states to improve their coverage of collective bargaining to 80 per cent of the workforce, up from 70 per cent in the Commission’s proposal. For the Work-Life Balance Directive, the EP specified that instead of sick leave pay as proposed by the Commission, remuneration should be equivalent to maternity leave pay and 80 per cent of the gross wage for parental leave and carers’ leave. For the Pay Transparency Directive, the EP aimed to widen the application of the transparency requirements from companies with more than 250 employees to companies with more than 50 employees. Perhaps the most far-reaching EP amendments with the potential to expand the scope of social Europe beyond the Commission’s proposals were related to the concept of gender and intersectionality in the case of the Pay Transparency Directive. Here the EP used the directive to bring gender-based rather than sex-based discrimination and intersectional discrimination into EU law.

The EP also made changes to the Commission’s proposals which were less supportive of a more social Europe. The small number of weakening amendments, almost all of which were for the Work-Life Balance Directive, remained within the logic proposed by the Commission. On the one hand, the EP added references across the directive which aimed to further take into consideration the impact of the directive on employers. On the other hand, the EP made changes to the flexibility of leave arrangements, proposing that parental leave and flexible working arrangements were possible before a child reaches the age of 10, instead of 12 in the Commission’s proposal. This proposal had already been included in the draft report by the EPP rapporteur and some EPP, Renew and S&D MEPs had proposed an even lower age limit.

The reasons why the mechanisms of technocratic and normative filtering so strongly shape negotiations on social Europe at the committee stage of the EP legislative process are worth exploring. In part, the approach adopted within social Europe is indicative of the institutional dynamics within the EP and between the EU institutions. The technocratic filtering supports or is the result of the long-term institutional norm of consensus-seeking across the left/right divide and the need to find a compromise that can be negotiated with the Council. Meanwhile, the Council’s modest positions on social Europe create an EP institutional response in which it positions itself as being more ambitious than the Commission, in the belief that the compromise will be somewhere between the positions of the two institutions. Here we would argue that despite the individual positions of MEPs and political groups at the amendment stage, the collective image of the EP as a defender of social Europe steers the committee negotiations in the direction of a compromise to favour social Europe. On numerous occasions, the EP has publicly positioned itself as the defender of social Europe vis-à-vis the Commission and the Council. and this communicative discourse, in the context of the EP’s position as the EU’s only democratically elected institution, appears to be a significant contributory factor. This highlights the importance of institutional norms and values within the EP and the role they play in the context of increased politicisation within the EP. In other words, while increased politicisation within the EP incites a technocratic response in line with institutional norms related to policymaking, this intersects with the established values of the institution via a process where the technocratic and normative mechanisms of politicisation management merge into techno-normative filtering.

Thanks to institutional politicisation management mechanisms, politicisation has not yet undermined the EP as a defender of social Europe. However, the exclusion of opposition to certain aspects of the proposed directives – a significant part of which emerged from within the EPP – has made it necessary to reach majorities in social Europe with the help of the left-leaning groups and the supportive EPP and liberal MEPs. The challenges of reaching majority positions have been more pronounced since the 2019 European Elections and may increase in the future.

Conclusions

Within this article we have analysed the patterns of politicisation and institutional politicisation management within the EP in the context of three legislative agreements adopted under the EPSR: the Work Life Balance Directive, the Minimum Wage Directive, and the Pay Transparency Directive. While the power of the EP as a co-legislator has steadily increased in recent years, it is also required to manage increased internal politicisation to reach a strong (i.e., large majority) common position vis-á-vis the Council during the OLP. Existing research on the EP and social Europe has mapped the political cleavages within and between the political groups (Crespy & Gajewska, Citation2010; Vesan & Corti, Citation2019). Meanwhile, the broader EP and EU literature provides insight into how increased politicisation and polarisation are managed within the EP and across the EU policy-making process (Brack & Costa, Citation2018; Schimmelfennig, Citation2020). To delve deeper into these empirical and conceptual debates, we have positioned our analytical lens on the committee stage within the EP legislative process. More specifically, we analyse the extent of input politicisation, that is, the extent to which MEPs aim to strengthen and weaken the Commission’s proposal, the extent of the consequential political polarisation, and the mechanisms through which this politicisation is managed.

Our empirical findings confirm the politicisation of social Europe during the EP committee stage both by its supporters and opponents. Both strengthening and weakening politicisation, particularly from the main political groups, remained within the logic of the Commission’s proposals and often had to do with the numbers: the size of companies covered by the directive and the level of remuneration for family-related leave. The few efforts to expand the boundaries of the directives for social Europe, and to include new issues and perspectives, were mainly from the GUE/NGL and the Greens/EFA, that is, from left-leaning challenger groups with a GAL-identity. On occasion, MEPs from the radical right ECR and ID, and perhaps surprisingly the largest group the EPP, politicised the process by proposing significant weakening changes to the numbers. MEPs from these groups also proposed radical rejections of various aspects of the Commission’s proposals.

The empirical findings from the three case studies also demonstrate that social Europe was a polarising issue both between but also within the groups, albeit this varied across the three directives. This reflects the specific sensitivities and contexts of each of the proposals, the shifts in the EP’s composition and more vocal opposition to social Europe among the radical right groups, but also practical factors, such as the selection of rapporteur(s) and the committees in charge. Social Europe was most contested in the case of the Pay Transparency and Minimum Wage Directives. For the Minimum Wage Directive, there was significant polarisation also within the groups on the left, which was less of a feature within the other two case studies. The scope of EU action (protection of national collective bargaining), the impact of legislation on companies, and gender equality and the concept of gender were the most polarising issues at the amendment stage.

It may be tempting to infer further generalisations or patterns regarding the political groups for social Europe, but their socio-political positioning is complex and varies from one directive to another. MEPs from the radical left and right groups are more consistent in their socio-economic positioning, but even then, there may be some internal divisions (but less so than the groups from the centre). Political division amongst the MEPs is, in part, ideologically driven and such divisions have increased with the changing composition of the Parliament from 2014–2019 to 2019-2024. Given the uniqueness of the EP political groups vis-à-vis national political parties, other important factors such as those mentioned above also influence the position of MEPs and the groups. It could be that the socio-economic positioning of MEPs demonstrates more consistency on specific themes (e.g., competitiveness, gender) found across EU social legislation. Whether this is the case requires more empirical data, but it may explain why some directives are more contentious within the political groups than others.

While there is considerable politicisation during the amendment stage, the adopted reports for all three case studies illustrate that such politicisation is managed and normatively filtered towards an EP position that is more supportive of social Europe than the initial loud opposition and polarisation would suggest. Politicisation against social Europe is almost completely side-lined from political compromises despite its visibility in the amendments, including within the ranks of the EPP and the liberals. In addition, the more radical proposals to strengthen social Europe and to push the boundaries of the Commission’s proposals were muted through a process of technocratic filtering that aligned the EP’s position with the rationale and logic of the Commission’s proposal. In other words, true to the EP’s reputation as a social actor, the EP positions are overwhelmingly supportive of social Europe. Yet they remain within the limits of a technical discourse and do not challenge the premise of the Commission’s proposal, which often sets both minimum – and sometimes flexible – standards across the EU rather than a strict harmonisation of policy. Overall, the mechanisms of normative and technocratic filtering demonstrate the important role of EP’s institutional norms and values and how they intersect in politicisation management processes and shape negotiations on social Europe at the committee level.

Our three case studies therefore demonstrate that the EP has mainly used its increased legislative powers to minimise political division and polarisation and to support and strengthen already existing aspects of Commission proposals. The increased politicisation within the EP is therefore not a hindrance nor barrier to the development of a stronger social Europe. If the political momentum surrounding EPSR continues, the EP is therefore likely to continue its role as a defender of social Europe and to politically capitalise on the strengthening of the field. Nevertheless, broader issues regarding the development of social Europe and the political economy of European integration remain. Whilst in the short-term social Europe may expand, the approach and behaviour of the EP is very much one that supports the current status quo within social Europe and is about expanding its parameters. Whether this approach, necessary though it may be to navigate politicisation and the dynamics of the OLP, proves itself sufficient to stem the backlash against the European project remains an open question. At the heart of the Juncker Commission’s approach to launching the EPSR, and one that has continued under the Commission of von der Leyen, is the need to respond to the negative electoral consequences of austerity and to expand social Europe. Yet this expansion continues with what Bremer and McDaniel (Citation2020) refer to as a social democratic interpretation of austerity, which legitimises austerity as an approach, but pledges social investment in supply-side economics in areas such as education, childcare, and active labour market policies while cutting other public spending. As noted by Elomäki (Citation2023, p. 5), from the perspective of social justice, the alternative model provided by the social investment paradigm is limited. Given the limited space within the EP for the emergence of new ideas and a genuine alternative to the EU’s current model of political economy, the approach adopted may prove itself politically unsustainable in the longer term.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Paul Copeland

Paul Copeland is Professor of Public Policy at Queen Mary University of London

Anna Elomäki

Anna Elomäki is Academy Research Fellow at Tampere University

Barbara Gaweda

Barbara Gaweda is Senior Researcher at University of Helsinki

References

- Ahrens, P., & Abels, G. (2017). Die Macht zu gestalten – die Mutterschutzrichtlinie im legislativen Bermuda-Dreieck der Europäischen Union. FEMINA POLITICA – Zeitschrift für Feministische Politikwissenschaft, 26(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.3224/feminapolitica.v26i1.03

- Ahrens, P., Gaweda, B., & Kantola, J. (2022). Reframing the language of human rights? Political group contestations on women’s and LGBTQI rights in European Parliament debates. Journal of European Integration, 44(6), 803–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2021.2001647

- Bacchi, C. (2009). Analysing policy. Pearson Higher Education.

- Berthet, V. (2022). Norm under fire: Support for and opposition to the European union’s ratification of the Istanbul convention in the European parliament. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 24(5), 675–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2022.2034510

- Börzel, T. A., Broniecki, P., Hartlapp, M., & Obholzer, L. (2023). Contesting Europe: Eurosceptic dissent and integration polarization in the European parliament. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 61(4), 1100–1118. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13448

- Brack, N., & Behm, A. S. (2022). How do Eurosceptics wage opposition in the European Parliament? Patterns of behaviour in the 8th legislature. In P. Ahrens, A. Elomäki, & J. Kantola (Eds.), European parliament’s political groups in turbulent times (pp. 147–172). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brack, N., & Costa, O. (2018). Democracy in parliament vs. democracy through parliament? Defining the rules of the game in the European Parliament. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 24(1), 51–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2018.1444625

- Bremer, B., & McDaniel, S. (2020). The ideational foundations of social democratic austerity in the context of the great recession. Socio-Economic Review, 18(2), 439–463. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwz001

- Bressanelli, E., & Chelotti, N. (2018). The European Parliament and economic governance: Explaining a case of limited influence. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 24(1), 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2018.1444627

- Bressanelli, E., Koop, C., & Reh, C. (2020). EU Actors under pressure: Politicisation and depoliticisation as strategic responses. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1713193

- Bulmer, S., & Burch, M. (1998). Organizing For Europe: Whitehall, The British state and European union. Public Administration, 76(4), 601–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00128

- Copeland, P. (2022). The Juncker Commission as a politicising bricoleur and the renewed momentum in social Europe. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 60(6), 1629–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13336

- Copeland, P., & Daly, M. (2012). Varieties of poverty reduction: Inserting the poverty and social exclusion target into Europe 2020. Journal of European Social Policy, 22(3), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928712440203

- Crespy, A., & Gajewska, K. (2010). New parliament, new cleavages after the eastern enlargement? The conflict over the services directive as an opposition between the liberals and the regulators. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 48(5), 1185–1208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02109.x

- Crum, B. (2020). Party groups and ideological cleavages in the European Parliament after the 2019 elections. In S. Kritzinger, C. Pledcia, K. Raube, J. Wilhelm, & J. Wouters (Eds.), Assessing the 2019 European parliament elections (pp. 54–65). Routledge.

- De Ville, F., & Gheyle, N. (2024). How TTIP split the social-democrats: Reacting to the politicisation of EU trade policy in the European parliament. Journal of European Public Policy, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2223226

- De Wilde, P., Leupold, A., & Schmidtke, H. (2016). Introduction: The differentiated politicisation of European governance. West European Politics, 39(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1081505

- Diogini, M. K. (2017). Lobbying in the European parliament. Battle for influence. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Elomäki, A. (2023). Austerity and its alternatives in the European parliament: From the Eurozone crisis to the COVID-19 crisis. Comparative European Politics, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-023-00363-3

- Elomäki, A., & Gaweda, B. (2022). Looking for the ‘social’ in the European semester: The ambiguous ‘socialisation’ of EU economic governance in the European parliament. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 18(1), 166–183. https://doi.org/10.30950/jcer.v18i1.1227

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2014). Introduction: Beyond market regulation. Analysing the European integration of core state powers. In P. Genschel, & M. Jachtenfuchs (Eds.), Beyond the regulatory polity? The European integration of core State powers (pp. 1–23). Oxford University Press.

- Hall, P., & Taylor, R. (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44(5), 936–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x

- Hix, S., Noury, A. G., & Roland, G. (2007). Democratic politics in the European parliament. Cambridge University Press.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From PermissiveConsensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Kantola, J. (2022). Parliamentary politics and polarisation around gender: Tackling inequalities in political groups in the European Parliament. In P. Ahrens, A. Elomäki, & J. Kantola (Eds.), European parliament’s political groups in turbulent times (pp. 221–243). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kantola, J., Elomäki, A., & Ahrens, P. (2022). Introduction: European parliament’s politics groups in turbulent times. In P. Ahrens, A. Elomäki, & J. Kantola (Eds.), European parliament’s political groups in turbulent times (pp. 1–23). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kreppel, A., & Hix, S. (2003). From ‘grand coalition’ to left-right confrontation: Explaining the shifting structure of party competition in the European Parliament. Comparative Political Studies, 36(1-2), 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414002239372

- Leibfried, S. (2010). Social policy: Left to the markets and the judges. In H. Wallace, W. Wallace, & M. Pollack (Eds.), Policy making in the European union (pp. 253–282). Oxford University Press.

- Lord, C. (2018). The European Parliament: A working parliament without a public? The Journal of Legislative Studies, 24(1), 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2018.1444624

- Michon, S., & Weill, P. E. (2023). An ‘East-West split’ about the posting of workers? Questioning the representation of socio-economic interests in the European Parliament. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 31(3), 719–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2022.2029370

- Novak, S., Rozenberg, O., & Bendjaballah, S. (2021). Enduring consensus: Why the EU legislative process stays the same. Journal of European Integration, 43(4), 475–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1800679

- Petri, F., & Biedenkopf, K. (2021). Weathering growing polarization? The European Parliament and EU foreign climate policy ambitions. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(7), 1057–1075.

- Ripoll Servent, A. (2015). Institutional and policy change in the European Parliament: Deciding on freedom, security and justice. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ripoll Servent, A. (2018). The European parliament. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Ripoll Servent, A. (2019). The European parliament after the 2019 elections: Testing the boundaries of the 'Cordon sanitaire'. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 15(4), 331–342. https://doi.org/10.30950/jcer.v15i4.1121

- Roos, M. (2021). The parliamentary roots of European social policy: Turning talk into power. Springer Nature.

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2020). Politicisation management in the European union. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(3), 342–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1712458

- Settembri, P., & Neuhold, C. (2009). Achieving consensus through committees: Does the European parliament manage?*. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 47(1), 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2008.01835.x

- Thelen, K., & Steinmo, S. (1992). Historical Institutionalism in comparative politics. In S. Steinmo, K. Thelen, & F. Longstreth (Eds.), Structuring politics: Historical institutionalism in comparative analysis (pp. 1–32). Cambridge University Press.

- Vesan, P., & Corti, F. (2019). New tensions over social Europe? The European pillar of social rights and the debate within the European parliament. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(5), 977–994. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12863

- Vesan, P., Corti, F., & Sabato, S. (2021). The European commission's entrepreneurship and the social dimension of the European semester: From the European pillar of social rights to the COVID-19 pandemic. Comparative European Politics, 19(3), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-020-00227-0

- Wendler, F. (2019). The European Parliament as an arena and agent in the politics of climate change: Comparing the external and internal dimension. Politics and Governance, 7(3), 327–338. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i3.2156

- Yordanova, N. (2009). The rationale behind committee assignment in the European Parliament: Distributive, informational and partisan perspectives. European Union Politics, 10(2), 253–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116509103377

Annex 1: Coding scheme

One amendment could only be coded with one code under each category. Often, however, one amendment could do several things at once. In these cases, the most prominent orientation was picked.

1 Scope of action

1.1 Strengthening: Amendments that can be interpreted to strengthen the Commission’s proposal from the perspective of social Europe.

1.2 Weakening: Amendments that can be interpreted to weaken the Commission’s proposal from the perspective of social Europe.

1.3 Clarification: Amendments that clarify the Commission’s proposal without significantly changing its content. The category includes unclear amendments.

2. Issues and themes

2.1 Scope/role of EU action: References to subsidiarity and proportionality, respect for national collective bargaining, need of strong EU action, impacts of EU legislation

2.2 Extent of bindingness: References to bindingness, flexibility, penalties and compensations, litigation, and monitoring and implementation mechanisms

2.3 Company responsibilities and perspectives: References to responsibilities for companies, size of companies covered, administrative burdens

2.4 Public spending: References to EU budget and funding programmes, national budgets, need for investment, costs

2.5 Social partners: References to social partners, collective bargaining (issues related to autonomy and respect of national bargaining under scope of EU action)

2.6 Intersectionality: References to race/ethnicity, migrant background, disability, sexual orientation, how grounds of discrimination interact

2.7 Gender equality: References to the concept of gender, gender diversity, and gender equality

2.8 Social rights: References to social rights, expanding or narrowing the group of individuals covered by the proposal

2.9 Role of case law and acquis communautaire, other legal mechanisms

2.10 Other

3. Political group

3.1 EPP

3.2 S&D

3.3 Renew Europe / ALDE

3.4. ID

3.5. Greens/EFA

3.6 ECR

3.7. GUE/NGL

3.8. EFDD / NI