ABSTRACT

The effectiveness of work performed through interprofessional practice is contingent on the nature and extent of communication between professionals. To date, there is little research exploring how the patterns of communication may impact interprofessional work. This study focused on communication during interprofessional meetings to better understand the interprofessional work performed through these encounters. Specifically, it examined how interactional discourse, that is, the patterns of language, influenced work performed during interprofessional meetings. A series of four interprofessional meetings in a rehabilitation unit were observed. Twenty-one participants were observed, including medical, nursing, allied health clinicians, and health professions students. Follow-up stimulated-recall interviews were conducted with five meeting participants. The data collection consisted of video and audio recordings and detailed field notes. Data were analyzed using a combination of genre analysis, a form of discourse analysis, and activity system analysis, drawing on Cultural Historical Activity Theory. This facilitated an in-depth examination of the structure of discourse and its influence on meeting outcomes. The meeting structure was defined and predictable. Two distinct forms of discourse were identified and labeled scripted and unscripted. Scripted discourse was prompted by standardized documents and facilitated the completion of organizational work. In contrast, unscripted discourse was spontaneous dialogue used to co-construct knowledge and contributed to collaboration. There was constant shifting between scripted and unscripted discourse throughout meetings which was orchestrated by experienced clinicians. Rather than fragmenting the discussion, this shifting enabled shared decision making. This research provides further insights into the interprofessional work performed during interprofessional meetings. The scripted discourse was highly influenced by artifacts (communication tools) in meetings, and these were used to ensure organizational imperatives were met. Unscripted discourse facilitated not only new insights and decisions but also social cohesion that may influence work within and outside the meeting.

Introduction

Interprofessional practice is an essential principle underpinning effective healthcare, but its implementation faces ongoing challenges (Morgan et al., Citation2015; World Health Organization, Citation2010). The impact of work performed through interprofessional practice is contingent on factors, such as the influence of professional roles, and the nature and extent of communication between professionals (Brown et al., Citation2011; Morgan et al., Citation2015; O’Carroll et al., Citation2016; Reeves et al., Citation2017; Xyrichis & Lowton, Citation2008). One context where this is underexplored is during interprofessional meetings (IPMs). To date, there has been limited examination of how interprofessional communication influences the work performed during meetings. For example, research examining IPMs, a cornerstone of healthcare communication, has occurred broadly across healthcare settings but has focused on specific aspects including information flow (Demiris et al., Citation2008), meeting facilitation (Schmidt et al., Citation1998), decision making (Gibbon, Citation1999; Lanceley et al., Citation2008), communication (Bokhour, Citation2006; Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2010), interactions (Arber, Citation2008; Bell, Citation2001), education (Nisbet et al., Citation2015) and collaboration (Doornebosch et al., Citation2022; Reeves et al., Citation2009; Suter et al., Citation2009). This study was conducted in rehabilitation, a healthcare setting which involves the management of patients with complex and chronic health conditions. Interprofessional practice is essential to best care for such patients and the importance of interprofessional practice in rehabilitation is well recognized (Clarke, Citation2010 ; Wagner, Citation2000).

Background

In rehabilitation, IPMs are routine practice and have been the focus of most existing research examining interprofessional practice in this setting (Ferguson et al., Citation2009 ; Gibbon, Citation1999). Previous studies of interprofessional practice in rehabilitation have highlighted that meetings involve many individuals and provide an opportunity for teams to identify patients’ problems, co-ordinate care, review patient progress, and plan discharge (Ferguson et al., Citation2009; Tyson et al., Citation2012). It has been shown that within IPMs, rehabilitation teams may develop a common language for efficient communication (Gibbon, Citation1999). IPMs in this context offer an opportunity to examine how discourse, that is the written and verbal communication occurring during meetings, influences interprofessional work.

Existing research on interprofessional communication has primarily focused on self-reporting, neglecting contextual influences (Morgan et al., Citation2015). Observational methods might provide more insight into the work performed through communication and interactions. In an integrative review, Morgan et al. (Citation2015) sought to identify studies that had used observational research to investigate interprofessional practice in primary care from 2005 to 2013. They found that out of 105 primary research studies, only 11 incorporated direct observation of clinical practice. This review highlights the importance of attending to the complexities of interprofessional practice by directly examining its enactment within context (Morgan et al., Citation2015).

This study uses observational methods to examine how IPM discourse shapes and is shaped by an orientation to interprofessional work by addressing the following research questions:

What are the discursive patterns and interactions occurring during IPMs in a rehabilitation team?

What work is performed through IPM discourse?

For the purpose of this paper, discourse refers to meaningful language patterns in written texts and spoken interactions (Eggins & Slade, Citation2004). However, it is acknowledged that “discourse” has numerous meanings influenced by disciplinary traditions (Dornan, Citation2014).

Methods

Methodological framing

This study is framed by two theories and has drawn on their analytical tools. The first is genre theory, the second is Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT). These are described below.

Genre theory, a functionally and contextually oriented model, defines a genre (written or spoken text) as a staged, goal-oriented social process (Martin, Citation1997). In healthcare there are many recurring, goal-oriented encounters that can be considered as genres such as, handovers and meetings. Informed by genre theory, genre analysis first involves identifying functional stages within a communication encounter. The second aspect of genre analysis relates to the social context of language which reflects its grounding in Halliday’s (Citation1978) work in functional linguistics. Halliday (Citation1978) positioned language as a social practice through which people construct meaning through language and events. The social dimension relates to the context of the genre. For analytical purpose, elements of the context are referred to as contextual variables; these are what is being said in the text, who is involved and how the text is organized (e.g., written or spoken). Therefore, genre analysis is sensitive to the context in which communication occurs, taking into account how the contextual variables, such as participants, their relations with each other and topics of the text are construed through language to achieve the text’s purpose or social goal (Martin, Citation1997). In this study, genre analysis was used to identify the functional schematic stages of the meeting genre and the language features of the contextual variables (i.e., what, who, and how) occurring during IPMs.

CHAT is a socio-cultural theory in which individual or collective activities are understood as bound to social, cultural, and historical settings (Engeström, Citation2018). This theoretical lens was used to attend to the factors that influenced discourse and work performed during IPMs. CHAT informed analysis attends to collective human activities by examining activity systems (see ). CHAT uses diagrammatic representations (activity systems) to explore how collective work is influenced by the rules of practice, tools, divisions of labor and emergent contradictions (Engeström, Citation2018). This allows deep examination of the factors which shape human activity, the goal(s) or objective(s) and the outcomes to be achieved (Engeström, Citation2018) (see ). A fundamental analytical concept of CHAT is the notion of contradictions and tensions which occur within an activity and/or between multiple interrelated activities (Engeström, Citation2018). These dynamic tensions have the potential to be both positive and negative. On one hand, tensions can be perceived as problems or conflicts that are counterproductive to change (Mészáros, Citation1998). On the other, they can be seen as a vital factor as tensions can promote examination and development of social constraints; they also contribute to the forward drive required for organizational change (Engeström & Sannino, Citation2011; Mészáros, Citation1998).

Figure 1. Visual depiction of an activity system adapted from Engeström (Engeström, Citation2018).

While the combined use of genre and CHAT analysis is not common, they complement each other theoretically and functionally. Theoretically, they are both underpinned by a socio-cultural worldview and key connections between the theories have been promoted by Martin (Citation2020). Functionally, genre theory offered an integrated, comprehensive, and systematic way to examine meeting discourse (Eggins & Slade, Citation2004). Using this approach allowed the examination of meeting discourses as interprofessional activities in themselves and therefore enabled the analysis of these activities through CHAT. Employing a combination of methodologies and analytical methods enabled us to address the project’s research aims as we examined the structure of discourse through genre analysis to answer RQ1 and then critically examined the influences and outcomes of the discourse using CHAT-based analysis to answer RQ2.

Design

This study employed qualitative methods, including participant observations and stimulated recall interviews to examine IPM practices. Video and audio data, along with field notes, were collected to systematically analyze meetings. Observations provided detailed descriptions of actions and social interactions (Ajjawi et al., Citation2020; Kent et al., Citation2016). Stimulated recall interviews, which involved using external stimulus (in this case, video of meeting interactions) to prompt discussion, were conducted with meeting participants to clarify ambiguous interactions (Dempsey, Citation2010). The features of the research setting are described in Appendix One.

Participants, sampling, and recruitment

Healthcare professionals (medical, allied health, and nursing clinicians) and students who attended IPMs were the study participants. A convenience approach was used for observations as participant attendance varied each week. Purposive sampling was employed for stimulated recall interviews to include participants from different professions and clinical experience levels (see Appendix One) (Cohen et al., Citation2007). Sample size was determined based on the principle of information power, considering study aim, sample specificity, use of established theory, quality of dialogue and analysis strategy (Malterud et al., Citation2016). These items were considered during the project design, leading to the provisional sample size; N = 4–6 observations and N = 4–8 stimulated recall interviews. Before concluding the data collection, sample size was interrogated using information power and the total number of meetings observed (N = 4) and interviews conducted (N= 5) reflect that data collected had adequate information power for rich analysis.

Prior to recruitment, the primary researcher (JP) engaged with the rehabilitation team to develop rapport and ensure familiarity with the project (Tai et al., Citation2021). Written consent was obtained from all meeting participants before data collection commenced and verbal consent was reconfirmed before meetings were recorded. Participants who agreed to an interview were provided with additional project information and written consent was obtained from interview participants.

Data collection: observations and interviews

The data consisted of video and audio recordings and handwritten field notes. These methods of data collection allowed analysis of verbal and non-verbal behaviors and to link physical and linguistic interactions for analysis (Iedema et al., Citation2006). Video and audio data were anonymized and transcribed verbatim using transcription conventions adapted from Eggins and Slade (Citation2004) (see Appendix Three).

Field notes included relevant information about the study, such as the number of participants, duration of meetings and interactions that could be useful for subsequent stimulated recall interviews and analysis (Tai et al., Citation2021). Stimulated recall interviews were conducted after each meeting to expand or confirm understanding but were not used as data in this study (Nisbet et al., Citation2015). All data collection was conducted by the primary researcher in May 2022.

Data analysis

Data analysis was led by the primary researcher (JP), and frequent meetings were held among the research team. Genre analysis was used to examine the structure of discourse during IPMs, and CHAT analysis examined the influences and outcomes of the discourse.

Genre analysis

Genre analysis involved mapping the data and was informed by Eggins and Slade (Citation2004). This process is outlined in Appendix Two and began with JP reviewing video data to identify how conversation moved through specific stages (Step 1). Data were then examined by JP and RWK to confirm stages and to define their function (Step 2). Then, contextual variables were identified to examine the “who” (meeting attendees), the “what” (the content or focus) and the “how” (the communication artifacts or tools that were used to facilitate communication, both spoken and written) (Step 3). Linguistic analysis, which is the usual fourth and final step of genre analysis, was not incorporated as this was not the focus of our initial analysis. The stages identified through Steps 1–3 were used to develop the analytical framework which guided genre analysis (see Appendix Two). The analytical framework was shared with the rest of the research team EM and CD and multiple sessions to review video data were conducted by the team to reach consensus. Disagreements were resolved through reanalysis of data and discussion.

Once the framework was finalized, it was clear that most interprofessional work relating to patient care happened during the stage labeled patient care planning, making it the most relevant to our research questions (Vears & Gillam, Citation2022). Therefore, it was decided to further explore the discourse in this stage by conducting an in-depth secondary genre analysis (see ). Secondary analysis involved labeling the patient care planning stage as a micro-genre which can be considered as a genre embedded within an overall macro-genre (Woodward-Kron, Citation2005). In this case, the patient care planning micro-genre was embedded within meetings as a macro-genre. Patient care planning consisted of a series of discrete discussions about individual patients (N = 69). A subset (61%, N = 35) of this underwent secondary data analysis (see ). This subset was reflective of the whole data set and was purposively selected to identify discussions that were representative in terms of duration and patient characteristics (Cohen et al., Citation2007).

Table 1. Overview of genre analysis.

Secondary genre analysis involved analyzing the patient care planning micro-genre by repeating the three steps outlined in Appendix Two. As we were interested in the linguistic features of this micro-genre, i.e., the structure and patterns of discourse, linguistic analysis was then completed (Step 4). This involved developing an adapted Initiation-Response-Follow-up (IRF) model of linguistic analysis to examine discourse structure which is detailed in Appendix Three (Eggins & Slade, Citation2004; Imafuku et al., Citation2014). Through this analysis, we identified key speech functions and discursive moves, which are the patterns of speech functions during discourse (Halliday, Citation1978). When agreement was reached on the steps of secondary analysis, the identified stages, speech functions, and discursive moves were uploaded as NVivo codes and applied to each transcript in the data subset. Associations between codes were explored, and we found that patterns of speech related to certain generic stages within this micro-genre. These associations led us to identify two distinct forms of discourse; labeled scripted and unscripted which were then applied as codes to the data subset.

CHAT analysis

Initial and secondary genre analyses positioned us to conduct a CHAT analysis to examine how discourse is related to meeting objectives and outcomes (i.e., the work performed during this interprofessional discourse). JP applied CHAT activity system factors as codes in NVivo (see ) to the transcribed data subset. Intersections between genre codes and CHAT codes were then examined. Patterns were identified between data coded as scripted or unscripted discourse and between CHAT factors (tools, rules, subjects, and division of labor). Activity system diagrams were used to interrogate patterns. These showed that scripted and unscripted discourse were separate activity systems (i.e., systems that function to complete an outcome or work). JP and RWK convened after independently examining the robustness of the proposed activity systems. Once agreement was reached, the team came together to establish consensus, with disagreements resolved through re-analysis of raw observational data, transcripts of the data subset and discussion. These activity systems, representing scripted and unscripted discourse, were inductively examined to identify objectives (i.e., the goals achieved through discourse) and how these related to interprofessional work as an outcome. Once activity systems and their objectives and outcomes were finalized, activity system diagrams were used to explore connections and contradictions between the two systems (Engeström, Citation2018; Engeström & Sannino, Citation2011).

Researcher positioning and reflexivity

The research team has a diverse mix of expertise which influenced our collaborative work and our interpretation of data. JP has extensive experience as an inpatient rehabilitation physiotherapist which helped her develop rapport with participants. Her intimate knowledge of meeting processes facilitated data collection and analysis (Burns et al., Citation2012). RA works as a consultant in the team constituting our research participants, making her a researcher-participant. This provided a unique perspective which enabled greater insight into some of the nuanced processes and discourse occurring during meetings (Burns et al., Citation2012). However, acting as a researcher-participant presented challenges and risks of bias which were carefully considered during project design. RA was not involved in recruitment or consent processes. She attended meetings as per usual practice and was not involved as an observer or interviewer. CD and EM are experienced medical education researchers with backgrounds in physiotherapy and RWK is a healthcare communication researcher with a background in linguistics. The lenses through which we considered the data reflected our different experiences and worldviews.

Reflexivity was prioritized in this project, particularly during data collection as we recognize the researcher’s pivotal position during this process (Tai et al., Citation2021). The primary researcher completed a reflexive memo immediately after data collection to begin exploring the data generated and to record any new ideas and perceptions developed (Patton, Citation2002).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the participating hospital’s low-risk ethics panel, approval number LR22-002 -80,270.

Results

Four IPMs were attended by 21 participants: medical (N = 5), nursing (N = 1), and allied health (N = 7) clinicians from the rehabilitation team plus clinicians from the Early Supported Discharge (ESD) program, an external program that received referrals from the rehabilitation team (N = 3) and health professional students (N = 5) (see Appendix One for participant details). Duration and participant configuration of meetings varied. Multiple medical clinicians were consistently present, however allied health clinicians and the NUM attended as representatives on behalf of their disciplines. Each week 90 min was allocated for this face-to-face meeting to discuss patient goals, progress, and plan discharge; however, meetings often ran overtime (see ).

Table 2. Meeting details.

Meeting structure and participant roles

Genre analysis identified that meetings had a similar overall structure. A longer, formal stage was bookended by two brief informal stages. The structural and contextual variables of each stage are detailed in Appendix Two. The formal stage followed a defined format in which patients were discussed based on standardized documents that had been developed as part of a model of care used throughout the health service. Each patient was discussed in a predetermined format which was repeated until all patients had been discussed. As such, meetings had a defined and predictable structure. When meeting discussion was not focused on completing standardized documents, it still centered on patient care. During informal meeting stages, team members engaged in brief small talk but mainly discussed patient treatment and discharge planning.

Participation of different team members varied considerably depending on relative levels of influence during meetings. The senior medical clinician had the most clearly defined role as meeting chair. The chair, and to a lesser extent senior allied health clinicians, determined the sequence of patient discussions and managed the flow of conversation by signaling the transition between topics. Experienced medical and allied health clinicians demonstrated clear leadership, whereas less experienced clinicians mainly played supportive roles in meetings. For example, apart from when they were the designated scribe (a meeting role allocated at random), less experienced clinicians generally listened and provided information to substantiate what senior clinicians had stated. Less experienced clinicians typically only responded when questioned directly and provided additional information if prompted by another participant. Undergraduate medical and allied health students were present at all meetings and were observed to take notes during discussions relevant to their discipline. Students did not speak during meetings; however, their regular presence signified that meetings were recognized as a potential learning opportunity.

Scripted and unscripted discourse

Through genre analysis, we identified two distinct forms of discourse that occurred during the formal patient care planning stage of IPMs: scripted and unscripted discourse. Scripted discourse refers to talk driven by the completion of standardized documents, whereas unscripted discourse was spontaneous dialogue. CHAT analysis revealed these two discourses functioned as activity systems and a dynamic tension existed between the two; however, both were used to coordinate interprofessional work.

Scripted discourse

Scripted discourse had a consistent discursive pattern and was associated with the simultaneous completion of standardized documents that were part of each patient’s medical record. The process of completing these documents generated and sustained discourse patterns and team members’ participatory roles. During scripted discourse, the structure and language aligned with the format and wording of the documents, and as such, they formed an agenda that guided meetings. Participants all followed the standardized meeting processes which demonstrated an awareness of organizational procedures and team expectations; however, at times less experienced participants sought guidance. Intraprofessional (i.e., within the same profession) guidance was most common.

Speech was dictated by the standardized language printed on meeting documents; for example, goals were discussed as being achieved, progressing, plateauing, or ceased. provides an example of how discourse unfolded when it was driven by standardized documentsin this case, a “goal setting” form within the medical record. The sections of transcript in which a participant is reading from this form are shown in italic text (see Appendix Three for transcription conventions).

Table 3. Excerpt of scripted discourse.

At the conclusion of this excerpt, the topic of discussion changed once the scribe (M3) had completed the goal-setting form (Turn 25). As such, standardized documents, considered physical tools within the CHAT framework, directed the flow of talk and who was involved in interactions. This demonstrated a strong alignment between tools and division of labour in the scripted discourse activity system (shown in ).

Figure 2. Representation of scripted and unscripted activity systems. Pivotal factors highlighted in bold italics, strong alignment between factors represented by bold lines. Tensions represented by lightning shaped arrows. Tensions were between the subjects and the objective, and the division of labor and the objective of scripted discourse. A tension also existed between the two activity systems (i.e., between scripted discourse and unscripted discourse).

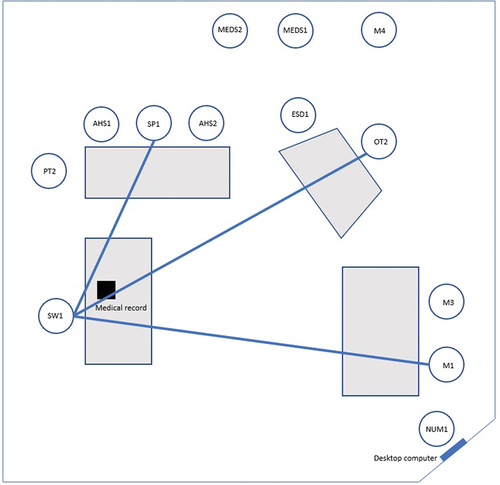

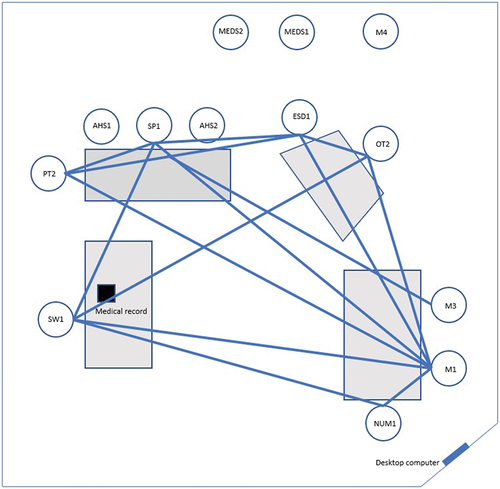

During scripted discourse, leadership was assumed by the scribe and discourse predominantly involved them reading questions aloud from standardized documents. These questions received relatively short responses in which participants provided their disciplinary perspective. Interactions involved few participants and the patterns of interaction, which reflect the rules of scripted discourse, related strongly to the documents (tools) being used by the scribe (considered as a subject) (see ). , developed from field note data, represents an observed scripted interaction. In this example, SW1, as scribe, asked questions that were responded to by SP1 and OT2. M1, as chair, was also involved seeking clarification about a response. Those not directly involved in the interaction were observed to complete other tasks, such as NUM1 who was entering computer data in this example.

Multiple tools were observed throughout meetings and participants relied on written handovers from colleagues who were absent. Participants read handovers and wrote notes to pass on information after meetings, while also attending other tasks, such as being the scribe. Often discussion was paused so the scribe could complete necessary documentation and at times experienced clinicians, most often the chair, would assume leadership and prompt discussion to continue when the scribe was still writing. This may have improved efficiency but potentially also impacted the quality of documentation being completed by the scribe. This meant there was a tension between the completion of documentation (the objective of the scribe) and meeting efficiency (an objective predominantly managed by the chair) (see ).

Prompts provided by the meeting documents reflected that standardized discussion was promoted by the healthcare service. This standardization ensured specific tasks were completed, such as mandatory documentation and the development of action plans for patient care. These were additional objectives of scripted discourse. However, there was a tension between the requirement to develop action plans and the delegation of actionable tasks (a division of labour) as often accountability for actions was not clearly articulated (see ). Although some conflicts existed within scripted discourse, the use of standardized documents helped ensure the team performed the organizational interprofessional work (outcome) required to meet imperatives important to the health service.

Unscripted discourse

Predominantly, scripted discourse was used to discuss patients (from 51% to 98% of each patient discussion); however, there were interruptions of unscripted discourse characterized by departures from the patterns of scripted discourse. These interruptions occurred more frequently at the beginnings of meetings, resulting in longer discussions for patients addressed early on (see ). Unscripted discourse varied in frequency, length, and participant involvement. As shown in , a representation of unscripted interaction developed from field note data, multiple participants were often involved. During this exchange, participants were observed to incrementally “piece” together information and unlike in , the scribe (SW1) was not central to the discussion.

Tools, such as standardized documents, were still used during unscripted episodes; however, the discourse no longer aligned with the language and structure of these documents. The rules of unscripted discourse reflected a change in language, turn lengths, discursive structure, and use of tools which can be seen in . In this example the bold text represents unscripted discourse (see Appendix Three for transcription conventions).

Table 4. Excerpt of unscripted discourse.

In this example, clinical experience and patient-specific knowledge is strongly demonstrated in turn 10 as SP1 explains the impact dysphasia may have on discharge safety. Experience and knowledge, considered cognitive tools within the CHAT framework, played a significant role in unscripted episodes, with experienced clinicians demonstrating expertise and driving interactions. Less experienced clinicians typically expanded on information provided by others or deferred to experienced clinicians’ judgment. Unscripted discourse was always concluded by experienced clinicians who exerted influence and managed the flow of talk with questions, such as “So, what does that mean for discharge?” (PT2) or statements like “We need to move on.” (M1). The unscripted discourse activity system in highlights the strong alignment between experienced clinicians (as subjects), their expertise and knowledge (tools) and their position of leadership (division of labour).

Unscripted discourse was used to discuss complex care needs and introduce new information. Detailed information was brought to the surface and discussed, allowing discussion to go beyond the prompts provided by standardized documentation. It was through this process that the team co-constructed knowledge about patients. Collaborative objectives drove unscripted discourse to expand beyond the boundaries of scripted discourse and through this activity the team engaged in collaborative interprofessional work (outcome).

Shifting between scripted and unscripted discourse: a necessary tension

A dynamic tension existed between completing the necessary organizational work and having sufficient time to engage in more spontaneous collaborative work. Continual shifting between scripted and unscripted discourse served to balance organizational and collaborative objectives and was coordinated by experienced clinician. They directed discourse by prompting spontaneous, unscripted discourse, and determining when to conclude these episodes. For example, unscripted discourse was encouraged with phrases, such as “What do you mean?” (PT2), and “So are we saying … ” (M1), whereas statements like, “Can you work [that out] later? We need to move on.” (OT1) and “Let’s leave [the goal] as is and we’ll discuss next week.” (PT1) indicated it was time to shift back toward scripted discourse.

Shifting between scripted and unscripted discourse served another imported function by facilitating shared decision-making. provides an example of when multiple perspectives informed decision-making by the team. Detailed information provided during unscripted discourse (Turns 31 and 179), led to co-construction of knowledge. A shift from unscripted to scripted discourse was prompted by the scribe (PT2) asking, “[are there] any other goals?” in Turn 180. In this example, the final decisions and actions documented by the scribe (Turn 209) were informed by information shared during both scripted and unscripted discourse.

Table 5. Excerpt of unscripted (bold) and unscripted discourse.

While scripted and unscripted discourse were used to perform separate aspects of interprofessional work, together they contributed to collaborative interprofessional work (see ).

Discussion

The discursive patterns occurring during IPMs were distinctive and shifting between scripted and unscripted discourse produced particular outcomes or work. These shifts were prompted by experienced clinicians, with documentation guiding scripted communication.

Direct observation of interprofessional practice revealed how discourse shaped the work performed during IPMs. Through a novel analytical approach informed by genre theory and CHAT this study highlighted the factors that influenced discourse and the work performed during IPMs.

Genre analysis revealed that IPMs were organizationally constituted encounters consisting of scripted and unscripted discourse. Scripted discourse was more dominant throughout meetings, which aligns with a discursive theory proposed by Laclau and Mouffe (Citation2014). This theory, applied in political and organizational studies, uses the metaphor of a discursive battle, which conceptualizes that a hierarchy of dominant and marginalized discourse exists within an organization (Laclau & Mouffe, Citation2014). As in the proposed model, we identified that scripted discourse did not dominate entirely, and unscripted discourse was interspersed throughout. Other research examining IPMs, has reported similar findings. For example, Bokhour (Citation2006) conducted detailed discourse analysis of meetings in a long-term care facility and identified three distinct communication practices. These practices had similar discursive patterns to our data; “writing reports” and “providing information” together were representative of scripted discourse and “collaborative discussion” was akin to unscripted discourse (Bokhour, Citation2006). However, these authors implied that only “collaborative discussion” helped meet the primary objective of IPMs which was to coordinate patient care and make decisions (Bokhour, Citation2006). Coordinating patient care was identified as the only meeting objective, and as such, other forms of discourse were deemed to impede interprofes-sional work. Another study with similar results was an observational study of rehabilitation IPMs by Ferguson et al. (Citation2009) This study reported that discussion was driven by organizational imperatives which prevented important conversation about patient care (Ferguson et al., Citation2009). There was a tension between performing organizational work and collaborative work, which we also identified in our data. However, we assert that using scripted and unscripted discourse during IPMs offered an opportunity for teams to engage in both organizational and collaborative work. These findings challenge the perception that IPMs serve a singular purpose (Bokhour, Citation2006; Ferguson et al., Citation2009).

In our data, relational factors relating to power, hierarchy, leadership, and membership were observed to influence participation during IPMs. The central role played by medical clinicians was similar to that described previously in rehabilitation research (Clarke, Citation2010; Ferguson et al., Citation2009; Pryor, Citation2005). Additionally, we found that experienced clinicians demonstrated leadership and contributed more than those less experienced, which reflect results presented by Wittenberg-Lyles et al. (Citation2010), who examined interprofessional collaboration in hospice meetings. Our findings show that not only were experienced clinicians involved more frequently but they coordinated important shifts from scripted to unscripted discourse. Hence, relational factors were found to influence team functioning and were linked to the work practices undertaken by the team. Practical guidance may help encourage the engagement of less experienced clinicians in IPMs. For example, establishing and regularly discussing IPM “ground rules” might be a useful approach to improve participation (Nisbet et al., Citation2015). Beyond the practicalities of the learning meeting processes, it is argued that education on team functioning is essential for the success of interprofessional work (Hall & Weaver, Citation2001). Exploratory research by Nisbet et al. (Citation2015) highlights the potential for IPMs to be used as a setting for workplace learning. These authors identified that meetings were a source of knowledge, allowing participants to gain insights into others’ professional practice, capabilities, and decision-making (Nisbet et al., Citation2015). In our data, practical and academic knowledge was shared through unscripted discourse, which enabled expertise to be demonstrated. This afforded exhibition of “know how” by experienced clinicians and recognition that different professions offered unique knowledge. Mylopoulos and Scardamalia (Citation2008) refer to this as a collective knowledge process and argue that it is through these iterations that improvement and innovation can occur. Collective knowledge was reflected in the interprofessional co-construction of knowledge observed in our data. Nisbet et al. (Citation2015) also showed that learning occurred through active participation and interaction during meetings and that this influenced other areas of interprofessional work. They reported that meeting interactions promoted communication outside meetings and increased confidence in junior clinicians to seek advice from interprofessional team members (Nisbet et al., Citation2015). This latter finding was said to be particularly important for patient safety as it suggested that IPMs had a broader scope of influence on patient safety beyond direct patient information exchange (Nisbet et al., Citation2015).

Further research is needed to understand how the work we observed performed in IPMs (including knowledge extension, role understanding, and social cohesion) influences work outside of the formal meeting space. Such a research approach would also expand on the self-report data presented by Nisbet et al. (Citation2015) examining the impact of meeting discourse on patient care and safety. If the knowledge shared through meeting discourse has the impact suggested by Nisbet et al. (Citation2015) and Mylopoulos and Scardamalia (Citation2008), it will be important for healthcare organizations to consider enhancing collective knowledge sharing within meetings. Our data showed that completing organizational tasks during meetings demanded a substantial amount of time, which reduced the time available for unscripted discourse, necessary to develop collective knowledge. While meetings offer a practical opportunity to complete mandatory organizational tasks, our findings suggest that it may be time to consider the tasks and tenor of IPMs more critically.

Our findings demonstrated a reliance on communication tools, for example, the medical record, to document verbal interactions during IPMs. The connection between the meeting discussion and documentation can be described as intertextuality (Bazerman, Citation2004). Written text, read from communication tools, prompted much of the meeting dialogue which was consequently then documented to direct patient care. It was beyond the scope of this study to examine how dialogue was interpreted outside the meeting context, however, we recognize it could offer important insights. Such interactions of verbal and written texts and, importantly, their impact on patient care have been explored in other healthcare settings. Goldszmidt et al. (Citation2014) explored how medical teams used a combination of recurrent verbal and written texts to collectively care for patients. These authors identified that verbal and written texts were collaboratively and progressively modified as teams refined their understanding of patient problems to develop strategies to address them (Goldszmidt et al., Citation2014). To build on the results from our study, future work should examine intertextual connections that link what is said during IPMs and the provision of patient care. This would support a deeper understanding of how meeting discourse relates to the complex work demands faced by interprofessional teams.

Strengths and limitations

The interpretation of findings is intrinsically strengthened and limited by research design. Strength was gained by including first-hand encounters of communication rather than relying on secondhand accounts obtained through interview (Merriam, Citation2002). Additionally, recording meetings increased the richness of data collection and enabled detailed analysis of interactional features during IPMs. Despite these strengths, data were drawn from one rehabilitation unit, and so may not necessarily be generalizable to other settings. However, the patient cohort and nature of rehabilitation being conducted was typical of rehabilitation units nationally and internationally (Langhorne & Pollock, Citation2022; Read & Levy, Citation2005). Further, this study provides a robust methodology for examining discourse in other healthcare contexts and highlights the relevance of such work. We acknowledge the limitations posed by a lack of gender diversity in our sample, as well as limited representation of some clinical groups, such as nursing and social work, however this reflected the composition of the participating team and is representative of IPMs in other rehabilitation settings (Ferguson et al., Citation2009; Paxino et al., Citation2022).

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the discursive interprofessional work performed during IPMs in rehabilitation. These results challenge the dominant perception that IPMs are primarily for exchanging information directly related to patient care. Instead, meetings were shown to provide opportunities to engage in organizational and collaborative interprofessional work which facilitated knowledge building and shared decision-making.

While scripted and unscripted discourse served different purposes, rather than causing fragmented discussions, the continual shifting between them served to balance organizational and collaborative work. This was orchestrated by experienced clinicians and contributed to interprofessional collaboration. Unscripted discourse enabled the sharing of unique clinical experience and profession-specific knowledge. Not only did this spontaneous offering of information influence decisions made about patient care but there was also likely “work” produced in the form of interprofessional relationship and knowledge-building. The study highlights the impact of discourse on meeting outcomes. Future research should explore the influence of discursive encounters on relationships and work beyond the meeting itself and vice versa.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (70.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2024.2343833

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Julia Paxino

Julia Paxino has experience in healthcare research and has a background as a physiotherapist. She has recently submitted her PhD in the area of interprofessional communication in rehabilitation, and works as a research fellow in collaborative practice and health professions education. Julia has published her work in international peer reviewed journals and has presented at a number of local and international conferences.

Elizabeth Molloy

Elizabeth Molloy is Associate Dean, Learning and Teaching, in the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences. She is also Professor of Work Integrated Learning in the Department of Medical Education, Melbourne Medical School, at the University of Melbourne. She has extensive experience in healthcare research and started her career as a physiotherapist. She completed her PhD on feedback in clinical education and has published more than 115 peer reviewed journal articles, book chapters and books, with a focus on workplace learning, feedback, and assessment, interprofessional education and clinical supervisor professional development.

Charlotte Denniston

Charlotte Denniston is a senior lecturer in Medical Education in the Department of Medical Education, University of Melbourne. She has experience in healthcare research and has a background as a physiotherapist. She completed her PhD in teaching and learning communication skills in the health professions and has over 10 scholarly outputs.

Rania Abdelmotaleb

Rania Abdelmotaleb is the Medical Director of Rehabilitation Medicine at Eastern Health and an adjunct senior lecturer at Eastern Health Clinical School Research (Monash University). She has extensive experience in qualitative and quantitative research in the field of rehabilitation research, including research conducted at Eastern Health.

Robyn Woodward-Kron

Robyn Woodward-Kron is the Director of Research Training in the Department of Medical Education, University of Melbourne. She is also Professor of Healthcare Communication, Department of Medical Education, University of Melbourne. She completed her PhD in educational linguistics and has over 100 research and scholarly outputs.

References

- Ajjawi, R., Hilder, J., Noble, C., Teodorczuk, A., & Billett, S. (2020). Using video‐reflexive ethnography to understand complexity and change practice. Medical Education, 54(10), 908–914. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14156

- Arber, A. (2008). Team meetings in specialist palliative care: Asking questions as a strategy within interprofessional interaction. Qualitative Health Research, 18(10), 1323–1335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732308322588

- Bazerman, C. (2004). Intertextuality: How texts rely on other texts. In C. Bazerman & P. Prior (Eds.), What writing does and how it does it: An introduction to analyzing texts and textual practices (pp. 83–96). Routledge.

- Bell, L. (2001). Patterns of interaction in multidisciplinary child protection teams in New Jersey. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00224-6

- Bokhour, B. G. (2006). Communication in interdisciplinary team meetings: What are we talking about? Journal of Interprofessional Care, 20(4), 349–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820600727205

- Brown, J., Lewis, L., Ellis, K., Stewart, M., Freeman, T. R., & Kasperski, M. J. (2011). Conflict on interprofessional primary health care teams–Can it be resolved? Journal of Interprofessional Care, 25(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2010.497750

- Burns, E., Fenwick, J., Schmied, V., & Sheehan, A. (2012). Reflexivity in midwifery research: The insider/outsider debate. Midwifery, 28(1), 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2010.10.018

- Clarke, D. J. (2010). Achieving teamwork in stroke units: The contribution of opportunistic dialogue. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 24(3), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820903163645

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education, 6. Routledge.

- Demiris, G., Washington, K., Oliver, D. P., & Wittenberg-Lyles, E. (2008). A study of information flow in hospice interdisciplinary team meetings. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 22(6), 621–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820802380027

- Dempsey, N. P. (2010). Stimulated recall interviews in ethnography. Qualitative sociology, 33(3), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-010-9157-x

- Doornebosch, A. J., Smaling, H. J., & Achterberg, W. P. (2022). Interprofessional collaboration in long-term care and rehabilitation: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 23(5), 764–777.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.12.028

- Dornan, T. (2014). When I say … discourse analysis. Medical Education, 48(5), 466–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12291

- Eggins, S., & Slade, D. (2004). Analysing casual conversation. Equinox Publishing Ltd.

- Engeström, Y. (2018). Expertise in transition: Expansive learning in medical work. Cambridge University Press.

- Engeström, Y., & Sannino, A. (2011). Discursive manifestations of contradictions in organizational change efforts: A methodological framework. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 24(3), 368–387. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811111132758

- Ferguson, A., Worrall, L., & Sherratt, S. (2009). The impact of communication disability on interdisciplinary discussion in rehabilitation case conferences. Disability & Rehabilitation, 31(22), 1795–1807. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280902810984

- Gibbon, B. (1999). An investigation of interprofessional collaboration in stroke rehabilitation team conferences. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 8(3), 246–252. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00240.x

- Goldszmidt, M., Dornan, T., & Lingard, L. (2014). Progressive collaborative refinement on teams: Implications for communication practices. Medical Education, 48(3), 301–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12376

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. Hodder Education.

- Hall, P., & Weaver, L. (2001). Interdisciplinary education and teamwork: A long and winding road. Medical Education, 35(9), 867–875. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00919.x

- Iedema, R., Long, D., Forsyth, R., & Lee, B. B. (2006). Visibilising clinical work: Video ethnography in the contemporary hospital. Health Sociology Review, 15(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2006.15.2.156

- Imafuku, R., Kataoka, R., Mayahara, M., Suzuki, H., Saiki, T. (2014). Students’ experiences in interdisciplinary problem-based learning: A discourse analysis of group interaction. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 8(2), 1. https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1388

- Kent, F., Francis-Cracknell, A., McDonald, R., Newton, J. M., Keating, J. L., & Dodic, M. (2016). How do interprofessional student teams interact in a primary care clinic? A qualitative analysis using activity theory. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 21(4), 749–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-015-9663-4

- Laclau, E., & Mouffe, C. (2014). Hegemony and socialist strategy: Towards a radical democratic politics (Vol. 8). Verso Books.

- Lanceley, A., Savage, J., Menon, U., & Jacobs, I. (2008). Influences on multidisciplinary team decision-making. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, 18(2), 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00991.x

- Langhorne, P., & Pollock, A. (2022). What are the components of effective stroke unit care? Age and Aging, 31(5), 365–371. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/31.5.365

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- Martin, J. R. (1997). Analysing genre: Functional parameters. In Christie, F., & Martin, J. R (Eds.), Genre and institutions: Social processes in the workplace and school (pp. 3–39). Continuum.

- Martin, J. R. (2020). Genre and activity: A potential site for dialogue between Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) and Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT). Mind, Culture, and Activity, 27(3), 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2020.1781898

- Merriam, S. B. (2002). Introduction to qualitative research. Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis (pp. 1–17). John Wiley & Sons.

- Mészáros, I. (1998). Dialectical transformations: Teleology, history and social consciousness. In Ollman, B., & Smith, T. (Eds.), Dialetics for the New Century (pp. 135-150). Palgrave MacMillan.

- Morgan, S., Pullon, S., & McKinlay, E. (2015). Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: An integrative literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(7), 1217–1230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.03.008

- Mylopoulos, M., & Scardamalia, M. (2008). Doctors’ perspectives on their innovations in daily practice: Implications for knowledge building in health care. Medical Education, 42(10), 975–981. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03153.x

- Nisbet, G., Dunn, S., & Lincoln, M. (2015). Interprofessional team meetings: Opportunities for informal interprofessional learning. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 29(5), 426–432. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1016602

- O’Carroll, V., McSwiggan, L., & Campbell, M. (2016). Health and social care professionals’ attitudes to interprofessional working and interprofessional education: A literature review. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1051614

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325002001003636

- Paxino, J., Molly, E., Denniston, C., & Woodward-Kron, R. (2022). Dynamic and distributed exchanges: An interview study of interprofessional communication in rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 45(15), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2096125

- Pryor, J. (2005). A Grounded theory of nursing’s contribution to inpatient rehabilitation. Deakin University.

- Read, S., & Levy, J. (2005). Differences in stroke care practices between regional and metropolitan hospitals. Internal Medicine Journal, 35(8), 447–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2005.00882.x

- Reeves, S., Pelone, F., Harrison, R., Goldman, J., & Zwarenstein, M. (2017). Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(8), 6. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub3

- Reeves, S., Rice, K., Conn, L. G., Miller, K. L., Kenaszchuk, C., & Zwarenstein, M. (2009). Interprofessional interaction, negotiation and non-negotiation on general internal medicine wards. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 23(6), 633–645. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820902886295

- Schmidt, I. B., Claesson, C., Westerholm, B., Nilsson, L. G., & Svarstad, B. L. (1998). The impact of regular multidisciplinary team interventions on psychotropic prescribing in Swedish nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 46(1), 77–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01017.x

- Suter, E., Arndt, J., Arthur, N., Parboosingh, J., Taylor, E., & Deutschlander, S. (2009). Role understanding and effective communication as core competencies for collaborative practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 23(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820802338579

- Tai, J., Fischer, J., & Noble, C. (2021). Focus on methodology: Observational studies in health professional education research. Focus on Health Professional Education, 22(1), 2204–7662. https://doi.org/10.11157/fohpe.v22i1.536

- Tyson, S. F., Greenhalgh, J., Long, A. F., & Flynn, R. (2012). The influence of objective measurement tools on communication and clinical decision making in neurological rehabilitation. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(2), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01555.x

- Vears, D. F., & Gillam, L. (2022). Inductive content analysis: A guide for beginning qualitative researchers. Focus on Health Professional Education: A Multi-Disciplinary Journal, 23(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.11157/fohpe.v23i1.544

- Wagner, E. H. (2000). The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 320(7234), 569–572. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7234.569

- Wittenberg-Lyles, E., Parker Oliver, D., Demiris, G., & Regehr, K. (2010). Interdisciplinary collaboration in hospice team meetings. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 24(3), 264–273. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820903163421

- Woodward-Kron, R. (2005). The role of genre and embedded genres in tertiary students’ writing prospect: an Australian Journal of TESOL, 20(3), 24–44.

- World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. World Health Organization.

- Xyrichis, A., & Lowton, K. (2008). What fosters or prevents interprofessional teamworking in primary and community care? A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(1), 140–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.01.015