ABSTRACT

Within the context of Australian higher education, Open Educational Practice (OEP) requires a collective response from researchers and practitioners to instantiate novel, sustainable, scalable, and evidence-informed educational practices. This article outlines practice-led research's (PLR) role in educational research in open education and its potential to drive transformation and knowledge creation for practice in and through practice itself. As a creative arts methodology, PLR foregrounds practice as the locus of research activities. Practice-led researchers are deeply embedded in the research process, and knowledge production occurs through the generation of artefacts, processes, and techniques. With a focus on real-time making and research, PLR promotes a culture of knowledge production through the active 'doing' of practice within a process-oriented framework. In this paper, OEP is reframed as a creative project, and PLR, with its stress on researcher/practitioner reflexivity, becomes a methodology capable of fostering open educational practices in becoming.

This speculative conceptual paper situates a discussion of PLR and open educational practice (OEP) as an emerging field within the Australian higher education context. As a creative arts methodology, PLR prioritises practice as the focal point of research activities. Practice-led researchers are intimately embedded within the research and knowledge production emerges from the creation of artefacts, languages, environments, systems, techniques, and processes. As a performative research approach, PLR is a material, situated, interdisciplinary and inventive methodology that involves the adoption of multiple methods, always led by practice. Sharing kinship with other methodological approaches that centre the practitioner as a researcher, PLR is unique in asserting the materiality of practice and the performativity of the research process. Practitioner researchers do not ‘think’ their way through or out of problems, rather, theory follows handling, and solutions are discovered in the doing of practice (Haseman and Mafe Citation2009). Perhaps, the most radical aspect of PLR is the assertion that tools and techniques engaged/invented by the practitioner can act as methods, in their own right.

The adoption of a PLR approach to Open Educational Practice (OEP) research occurs within a dynamic possibility space, implicating the embodiment of a researcher-practitioner, who cannot describe in advance what will emerge through practice. Yet, Open education is not new; the ‘classical’ meaning of ‘open’ education involves lifelong open and flexible learning, which implies easier access and open entry to institutions (Decuypere Citation2018; Mulder and Janssen Citation2013). The term OEP broadly describes ‘practices that include the creation, use and reuse of open educational resources (OER) as well as open pedagogies and open sharing of teaching practices’ (Cronin Citation2017, 2). Embracing such diverse practices within the neoliberal academy necessitates a collaborative endeavour by scholars and practitioners to develop sustainable, scalable, evidence-informed, and ethical solutions that align with the Australian cultural, regulatory, and political context (Stagg et al. Citation2023). PLR is a reflexive methodology showing great promise for exploring and developing new, innovative, situated OEP practices and approaches. Within this methodological framework, the practice intelligence and creativity of the open educational practitioner take centre stage. By framing OEP as a performative practice undertaken by the practitioner/researcher, we resituate openness as a creative educational project.

Thus situated, we specifically locate OEP within the broader global movement and the Australian context. Furthermore, open education is then recast within a New Materialist framework and further elaborated through a Deleuzian philosophy of Becoming (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1994) and Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed (2018). Both philosophical perspectives are brought into new proximity via the emancipatory and active potential of Punk Rock pedagogy (Kahn-Egan Citation1998). As such, we conceptualise OEP as an emergent educational project in becoming, involving ‘more than human’ modes of educational encounter. PLR is a highly reflexive methodology capable of capturing the dynamic practice evolutions the open educational practitioner must invent to progress their practice of openness. This paper asserts the performativity and creativity of PLR and its great promise for unleashing the transformative potential of OEP and expanding methodological frontiers beyond qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches.

Sector-wide transformation through the emerging field of open educational practice in Australia

For education to be transformative in support of the new sustainable development agenda, ‘education as usual’ will not suffice. (UNESCO Citation2016, 183)

Education and the right to access, seek out, receive, and impart knowledge are fundamental human rights (UNESCO Citation2023a). Yet access and participation in formal education can be hindered by a range of formidable barriers, including geographical, cultural, and social norms, prior achievements, individual or household income, the digital divide, physical circumstances, and individual norms (Brown and Czerniewicz Citation2010; Lane Citation2009). If ‘education as usual’ will not deliver the transformation required to support the global sustainable development agenda, new approaches that are student-centred, future-focused, emergent, and capable of this dynamic systemic change are urgently needed. Adopting open practices that reduce or remove barriers to access and participation for diverse learner populations in a globally connected world holds great potential. Open education is thus a challenge to the status quo, holding the higher education sector to account to fulfil its societal obligations. Through the instantiation of open educational practices, there is potential to recalibrate the mission of the academy beyond the perpetuation and vigorous pursuit of the neoliberal agenda of the past decades. We are talking about sector-wide transformation, a radical change agenda, and the re-enchantment of education.

Within the context of Australian higher education and its nascent culture of open, the adoption of open educational resources (OER) is reasonably well understood and adopted. However, the broader work of OEP is yet to emerge, as it has in Europe, America, and Canada (Stagg et al. Citation2018, Citation2023). Stagg et al. (Citation2023), acknowledge a burgeoning engagement with OEP in Australian universities, but also point out that further maturation is required to achieve its desired impacts and sustainability. Moreover, they note the unique cultural, political, and structural architecture of the Australian higher education system requires a sector-wide approach to support this emergent work (Stagg et al. Citation2018).

There is a growing awareness in the Australian context that the discourse of open must extend beyond the tangibility of OER and OER-enabled open educational practices (Stagg et al. Citation2023). Lane (Citation2009) cautions that while openness as a philosophy is important, ‘something being freely available (e.g. open access, open educational resources, etc.) is insufficient to enable many people to successfully engage with a more open educational provision’ (8). Lane argues that openness must be instantiated or structured to meet the specific requirements of excluded groups and that mediation between the various actors, both systems and people is an essential process to deliver on the promise of open. Thus, OEP can be viewed as paradigm-shifting, complex work undertaken by higher education practitioners. While the Australian adoption of OEP may lack maturity within the global context, it also presents the opportunity to build practices responsive to our regulatory, political, and cultural context and learn from the global example.

There are some landmark moments illustrative of the trajectory of open education globally. Notably, the establishment of the Open Education Conference in 2004 (OpenEd19 Citationn.d.), the 2007 Cape Town Open Education Declaration (Cape Town Open Education Declaration Citation2023b), ratified and extended in 2018 (Cape Town Open Education Declaration Citation2023a) and the publication of the OPAL report – Shifting Focus to Open Educational Practices (Andrade et al. Citation2011) a document that signals a shift from the accessibility of OER to an emphasis on quality and the innovation involved in OEP. More recently, a vast body of literature elaborating recommendations and frameworks for open practices (Inamorato Citation2018; Inamorato, Punie, and Castaño Citation2016), critiquing open education (Decuypere Citation2019; Knox Citation2013) and broadening the field of OEP (Brandenburger Citation2022; Conole and Ehlers Citation2010; Cronin Citation2017). These papers, conferences and frameworks are but a few pivotal moments in the ever-expanding discursive field of OEP, which spans systemic change, policy, practice and people. However, our focus is on the practitioners who do this complex work. Specifically, how PLR has the potential to capture their capabilities, inventiveness, and creativity and in turn, contribute to an evidence base for OEP to flourish in Australia.

At this juncture, keeping a cool head and resisting the urge to fetishize open education is essential. Indeed, OEP should not be viewed as a panacea for the neoliberal instrument – it can indeed be co-opted, and its potency corrupted by market forces. A caution elegantly addressed by Mathias Decuypere (2018) who describes the open learner who is instrumentalised, responsiblised, moulded, and conceptualised into the perfect educational subject. Thus conceptualised, the idealised educational subject/learner is covertly, materially, and relationally shaped by the platforms they engage with during their educational experiences. While Decuypere focuses on Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs), others raise similar concerns about the conceptualisation of the open learner and how they are framed by the promotion of OER's as an agent of social and educational transformation. The beneficiaries of open education are often conceived through ‘a set of idealised qualities to which learners are expected to adhere’ (Knox Citation2013, 822). Knox and Decupyere raise salient critiques of how learners are assumed to be universalised learning/consuming subjects within the open educational discourse and the practices and policies that govern them.

The authors share a discomfort with the figure of the ‘open learner’, which has as its mirror image the figure of the ‘open educator’, similarly conceived, if at all addressed directly. The approach we advocate offers a more expansive and philosophically grounded approach to open education that grants autonomy to the humans and the material relations at play in their educational encounters. PLR, then becomes a methodological approach capable of engaging with the entangled relations of people, processes, environments and technologies involved in the open educational assemblage – held together by the personal practice of the open educational practitioner.

Mapping the territory and locating the becoming of the open educational practitioner

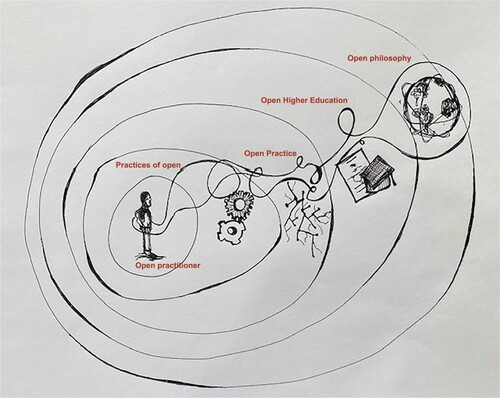

is an ecological model drawn from Adrian Stagg's ecological approach to open educational practice (Stagg Citation2021, Citation2022). A positioning that locates the open educational practitioner at the centre of teaching and learning practice and stresses the systems and context within which such a practice exists. The following diagram presents a simplistic version of Staggs's comprehensive body of work to illustrate the synergistic relations between the open education practitioner, their practice, and the PLR approach. Thus situated, the open practitioner is a figure who utilises the practices of openness. These practices can include the development of OERs and open assessments, or they might engage in open teaching and learning. From a research perspective, they may adopt open-access publishing, open data, open technology and more. Importantly, the open practitioner builds a unique personal practice, in this case, within the particularities of the Australian higher education system. Encompassing and exceeding the practitioner and their unique and situated practice of openness within the higher education system is a philosophy of becoming for open education.

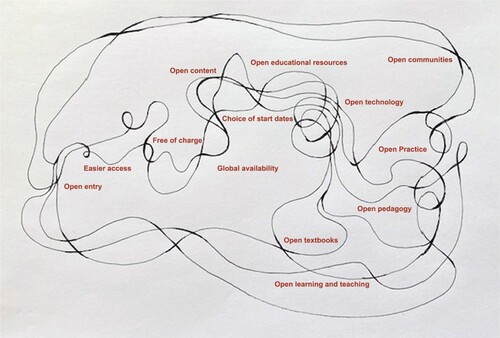

Figure 2. Hamilton, D. (2023). The expanding field of open education – a complex and entangled field of relations.

A philosophy of becoming open provides the connective tissue weaving through the open practitioner's values, behaviours, and approaches. situates the open practitioner as subject to and interacting with the relational fields of open education, exploring, and expanding their practice amidst the barriers and enablers faced when creating such a practice within the neoliberal academy ().

The ecological model of open education, illustrated in , establishes the relational fields and a philosophical positioning of open education. The open educational practitioner, located as they are, encounters a complex educational terrain of new and emergent practices and approaches that bear some unpacking. For instance, open education may entail free-of-charge access, flexible start times, or global availability of education (McAndrew Citation2010). In recent times, openness has also encompassed the open availability of content and resources, accelerated by advances in educational technologies. This evolution has given rise to a range of complex open practices, enabling several student-centred approaches, and contributing to the ongoing consolidation, extension, and expansion of the field of open education, as illustrated in . Furthermore, the onset of the digital revolution has both problematized and liberated global access and participation in formal higher education for teachers and learners. Critically, openness can be implicated in almost every aspect of university life and has expanded the mission well beyond an OER-focused discourse ().

Locating the philosophical and theoretical terrain of OEP

The open practitioner cultivates a practice of openness that prioritises student success, retention, and institutional belonging. For such an ambition to be realised, some common themes and ideas need to be clarified and framed within a philosophy of becoming. Thus enframed, the open practitioner is conceptualised as building a practice of openness, which is, essentially, an open-ended and creative project. Openness is intricately linked to human creativity and the acknowledgment that transformation is a fundamental aspect of existence. The New Materialisms, with their emphasis on materiality, evolution, and the forces of life and creativity, provide a theoretical framework capable of engaging with the complex and emergent nature of open educational practice we advocate. The New Materialisms are an emerging discursive field of twenty-first-century thought that has left its mark in such fields as philosophy, cultural theory, feminism, science studies, and the arts (Dolphijn and Tuin Citation2012). It is a philosophical and theoretical perspective that foregrounds a process-oriented relationship to creative practices, situating matter itself as an active force in the creative process. Technologies, environments, materials, and the world of ideas are not only sculpted by, but also co-productive and active in enabling, social worlds and human expression (Coole and Frost Citation2010).

As a practice orientation, the researcher is positioned within the sensing and feeling of practice, beyond a constructivist-essentialist impasse, because it avoids binary distinctions such as mind/body, nature/culture, and human/nonhuman (Fox and Alldred, Citation2015). Within this context, practice takes on a very particular meaning following the traditions of Bourdiau (Citation1990), Dewey (Citation1904) and Schön (Citation1991), who locate practice as a complex ‘embodied, materially mediated array[s] of human activity centrally organised around shared practical understanding’ (Schatzki Citation2001, 2). Bourdiau theorises a logic of practice, as being in-the-game, actions and interactions that occur in practice are not predetermined, they are emergent and operate according to specific demands of action and movements that occur in time and space (Bourdiau 1990). In this way, practice is synergistic with the new materialisms allowance for the processes/systems/frameworks in becoming and positions them in a vital, living, and enchanted world. Notably, under the New Materialisms, the open education project is reframed as a fluid, dynamic and creative project the open practitioner performs within.

Amongst the key influential figures of the New Materialisms stand Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, whose conceptualisation of becoming is particularly useful because it opposes a history of dualist Western metaphysics (Colebrook Citation2020). This view ascribes the human as a ‘subject’ in a position over and above the ‘object’ of inquiry. The subject/object binary separates humans from the environment as a species above nature, ascribing a godly view of the world to them. Deleuzoguattarian becoming offers a paradigmatic shift that decentres the human from the centre of the world's ordering, as much subjected to the forces of the world as they are acting/interacting with them. Being is classically understood as a fixed entity, goal, or identity. However, in Deleuzian parlance, being is reconceptualised as a process of constant transformation (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1996). Within this philosophical frame, open education is positioned as an emergent project requiring humans capable of dynamic and reflexive shifts in practice in a ‘more than human’ world.

To locate Deleuzian becoming in the field of education, Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed (2018) operates as a complimentary philosophical framework. Deleuze sets in motion the forces of life, Freire sets in motion the human condition. In so doing, he situates openness beyond purely technical matters or a set of rules. Indeed, he proposes an approach to education through which ‘pedagogy should not be reductively explained as a 'teaching method’, rather it is a fully fledged philosophy or a social theory’ (Freire Citation2018, 24). From a Freirean perspective, educational openness is not confined to classrooms but extends to life itself, encompassing our interactions within and beyond institutions towards diverse social contexts.

Freire calls for active and conscious participation in the historical process as responsible subjects. An educational posture that begins an acknowledgment that every ‘thematic investigation which deepens historical awareness is thus really educational, while all authentic education investigates thinking’ (Freire Citation2018, 109). It follows that openness is an essential feature of humanisation – a process of becoming more fully human through critical, dialogical praxis, which involves reflection and action upon the world to transform it (Freire Citation2018). Embracing openness, albeit critically and within certain boundaries, is a holistic commitment that aligns with the ever-changing nature of the world. Within a philosophy of becoming, via Deleuze and through the processes of humanisation posed by Freire, OEP is reframed as an idea beyond the binary position of open or closed. There are degrees of openness implied within this philosophical positioning. We can imagine the abundance of openness available as a catalysing agent for change, transformation, and growth in a ‘more than human’ world. A philosophy of openness then becomes the primary point of connection between the ecology of OEP and PLR.

Activating the processes of humanisation and becoming through Punk Rock Pedagogy

OEP and its instantiation within the context of the neo-liberal academy demands nimble, dynamic, and pragmatic approaches. Indeed, the seismic shocks of the global pandemic and Artificial Intelligence are emblematic of the disruptive forces that bedevil higher education globally. While there is a need for the dynamic open practitioner to have the capabilities to ‘play the game’, they must do so on their own terms. To do this, they must understand the landscape, and be able to seek out the open spaces of possibility and potential. We posit that punk rock pedagogy is best placed to activate and materialise Deleuzian and Freirean philosophical perspectives within OEP. However, we acknowledge that punk is a problematic symbol with its angry young men, civil disobedience, and roots in the Situationist International movement. Indeed, punk's intellectual utopian political agenda was cited as the force that ignited the Paris ‘68 riots and brought down the Charles de Gaulle government (Kavanaugh Citation2008). Yes, punk has less than ideal associations, but at its heart, it is a liberatory movement with its do-it-yourself mentality and critical engagement with life, possibility and becoming offering great potential for transformation. In the popular imagination, punk is all about loud music and bizarre fashion. Yet punk culture is more appropriately understood as the social practice of developing oppositional orientations towards the dominant culture (Romero Citation2019). Punk rock pedagogy positions punk like a flag, an open symbol; it only means what people believe it means. Thus, punk is an open-ended concept, a social practice, and a rejection of the status quo (Dunn Citation2016).

Seth Kahn-Egan (Citation1998) coined the term punk rock pedagogy to describe an educational approach that encourages students to learn through practices of self-critique encompassing themselves, their cultures, their government, and institutions. It takes the learner into the streets, building communities, identities, and cultures in becoming (Kahn-Egan Citation1998). Most importantly, punk rock teaches us that opposition does not end with critique, it is a catalyst for action. Punk rock pedagogy is a highly public, participatory discursive field. Rebekah Cordova (Citation2016) describes it as a pedagogy that does not enforce the status quo but fosters inquiring, precocious minds capable of interrogating the world about them and, in so doing, insert themselves actively into the world, through empowering acts of self-description and personal reclamation conducive to educative healing.

If becoming is about being open to the forces of life, and building a critical consciousness is about being a responsible historical subject, then punk rock pedagogy activates these ideas because it embraces a do-it-yourself ethos. It rejects passivity and champions personal and collective empowerment, foregrounding social critique and the politics of everyday life. If Freire is a call to action, punk rock pedagogy is a call to arms. Instead of passively accepting the world as it is, punk inspires people to do something about it, not waiting for someone else to fix what bothers them. "Or, as the oft-quoted punk slogan goes do it yourself or do it with friends’ (Dunn Citation2016, 38). The punk identity requires ‘a lived commitment to egalitarian ways of knowing, being, and becoming part of the world’ (Romero Citation2019, 42). The result is a view of education that occurs through a proliferation of co-investigations and co-becomings between educational actors that are dynamic and open-ended precisely because the stuff they are made up of is the surprise of connection and the shock of the new.

By putting Freire, Deleuze, punk and PLR into relation, we operate within a mode of creativity rather than critique. We seek the productive aspects of the theory, philosophy, pedagogy, and praxis to reveal new knowledge about practice, in and through the practice itself, and signal the rise of the open education practice-led researcher.

Introducing the practice-led researcher and their practice of resistance and creativity

It is important to acknowledge that OEP happens at the edges of the neoliberal academy where practitioner-researchers are likely to encounter systemic barriers to their work. For Australian higher education to undertake the paradigm-shifting, complex work of sector-wide transformation through OEP, we require new research and educational practices that reflect new ways of thinking, knowing and being. To keep up with the dynamism of this creative work and its interplay with the neoliberal academy, we contend that the performativity of PLR, its privileging of practice, creativity, and sensitivity to ‘more than human’ modes of encounter can provide novel practice insights for a genuinely transformative, unique and evidence informed field of OEP to emerge in Australia.

This paper acknowledges PLR is situated within a research culture that prioritises quantitative, data-driven research of the neoliberal academy, over contextual and practitioner-centred approaches. In the field of education research, there is an ongoing debate about research excellence and the emphasis on increasingly rigorous quantitative data driven research methods, leading to the prioritisation of specific objectives or measurable academic achievements for educational activity while marginalising other approaches that engage with the full breadth and complexity involved in educational experience (Biesta Citation2009). This has resulted in a shift from pursuing 'good' education to 'effective' education, characterised by a technical and quantified approach focused on terms such as 'evidence-based' and 'what works’ (Gorur and Koyama Citation2013). Our paper asserts the dynamic, agile, and reflexive nature of creative arts research and its potential to invigorate and enhance the universalising discourse of these approaches. It proposes that creative arts research can contribute to a renewed approach to education, emerging from within the constraints of the neoliberal academy through practice itself.

PLR emerged in the 1980s during a period of rationalist planning in Australian higher education, a time governed by the prevailing view that ‘higher education should contribute more directly to economic development [that] radically altered perceptions about educational expectations and productivity’ (Sullivan Citation2009, 43). Artists and art educators were transitioned from art schools and teacher training colleges into the university. Whilst it was widely acknowledged that artists had a tradition of being teachers, their contribution to research was yet to be established. There was broad agreement that the arts had a part to play in creating new knowledge that would benefit a cultural economy; However, the sciences were used as a benchmark for how the arts might contribute to research in the academy (Sullivan Citation2009, 45). The inheritance of this equivalence strategy is a legacy of research policy that bears little relation to art research. At best, it offers guidance in doing social science research utilising ‘themes and issues that are generated through the arts’ (Sullivan Citation2009, 46), which has led to impoverished outcomes for both. While important relationships and connections can be made, a clear delineation between the doing of social science and creative arts research must be made.

Social science research has a rich history of promoting change and liberation through participatory practices (Pascal and Bertram Citation2012). Notable figures such as Freire, Stenhouse, Schön, Whitehead, McNiff, Bourdieu and Wenger have all played a significant role in advancing this approach. This historical legacy is particularly relevant to OEP, aligning with its aspirations for a better future. Yet, the possibility space of OEP, we advocate, is inventive and demands a sensing, feeling practitioner who cannot describe in advance what will later emerge through practice. While other methodologies similarly position the practitioner as a researcher, PLR alone is an approach that exceeds quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods approaches. It exists within a third paradigm, provocatively articulated by Brad Haseman (Citation2010) as performative research, which is research ‘expressed in non-numeric data, but in forms of symbolic data other than words in discursive text. These include material forms of practice, of still and moving images, of music and sound, of live action and digital code’ (151). Performative research is unique to the creative arts because it expands the notion of participation to include ‘more than human’ educational collaborations and the researcher's unique professional practice.

PLR differs from mixed methods approaches, such as action research, design-based research and autoethnographic research that offer a human-centred positioning which is, ultimately, qualitative and apprehended in the form of words. For example, action research shares a kinship with the scientific method, validating ideas through practice via systematic processes and cycles (Efron and Ravid Citation2019, 7–9). Similarly, design-based research involves the interactive study of designed interventions that occur within the context of a natural environment (Anderson and Shattuck Citation2012; Philippakos, Howell, and Pellegrino Citation2021). Both action research and design-based research are practitioner-centred and reflexive. However, they do so through systematic, iterative cycles or designed interventions that invoke a human-centred view of an object or phenomenon under study. Autoethnographic research is also a reflexive approach but incorporates the relational through writing, stories, and methods that ‘connect the autobiographical and personal to the cultural, social, and political’ (Ellis and Adams Citation2020, 360). Nonetheless, the primacy of human interaction and its textual translation privileges the human participants and their perspective in the research design.

In contrast to these valuable practitioner-centred research methodologies, PLR uniquely dethrones the human as the centre of practice, relocating them as a participant in a field of actions of which they are a part. PLR orients itself towards creative processes in becoming where materials, environments, architectures, technologies, theories, and relationships actively participate in practice. PLR is a turn to material thinking and offers a way of ‘considering the relations that take place within the very process or tissue of making’ (Bolt Citation2014, 29). It is a methodology that makes specific demands of the researcher, who is ‘challenged at every turn to employ researcher-reflexivity to deal with emergence in the research process’ (Haseman and Mafe Citation2009, 213). Emergence locates the researcher within a dynamic system of complexity encompassing problem definition, methods, media, environment, and the meshwork of relations alive in creative processes. A complexity that shifts from the outset of the investigation because the ‘problem’ will be defined and redefined throughout the research project, and through this process of redefinition, so too are methods and languages of practice proposed and re-proposed to become the languages and methods of research. Therefore, PLR researchers do not make hypotheses in advance or conjure design approaches for testing – they follow the messiness of practice.

New Materialist scholar, Katve-Kaisa Kontturi (Citation2018), conceptualises following as positioning the researcher/artist within the unfolding of events, attentive and attuned to the affective and material conditions at play in art making. The PLR project will move beyond the original context, and the researcher must follow, naming and claiming along the way. In this regard, the multiple contexts the researcher finds themselves in will ultimately affect the findings. This process-oriented approach leads to possible forms of documentation and reporting that are ongoing and ever-present throughout the research. Following acknowledges the revelatory insistence of the materials and the complex relations humans now share with technologies. A new relationality that requires close attention – especially within the expanding field of open education (see ) and its close connection with technological advances. In this case, our focus is the emergent educational practices of the open educational practitioner, through their professional identity, and the creation of a personal practice of openness within the constraints and limitations of the neo-liberal academy.

Two cautions for PLR that may lead to methodological maturity

While PLR is highly flexible and accommodates various methods, it also presents challenges. The methodology can be open to abuse, with the potential for unsupported claims based on the practice's outcomes without proper theoretical grounding, evidence, and rigour. Additionally, engaging with the complexity of life and living in a constantly evolving world presents a significant challenge to the sustainability and scalability of practice produced through this methodological orientation.

Critics argue that PLR may lack rigour and objectivity, be too individualistic, and focus on marketable outcomes rather than exploring new ideas. It may also not integrate well with existing research. Bearing this criticism in mind, it's important to address two factors that contribute to these concerns. Firstly, PLR can become entrenched in logocentrism. Davies (2023) notes that while PLR has the potential to uncover new knowledge unattainable to traditional methodologies, creative methodologies can also become trapped in the theory/practice divide. Artist researchers do this when they position themselves and their practice as ‘natural, original and/or internal process, compared to theoretical knowledge which is external, artificial, deferred, and/or capable of contaminating the integrity of artistic practice’ (Davis Citation2023, 2). A stance that places the artist at the centre of the creative process with their practice revolving around their ability to manipulate materials according to their will. This is a stance that reinforces the subject/object divide and leads to claims about what the ‘practice tells us’ without properly attending to theoretical groundings capable of supporting claims to new knowledge. Secondly, the practice-led researcher may become too reactive and define their research only by its direct opposition to other, more traditional, research methods.

Both risks can ultimately lead to practice-led researchers making assumptions about the inherent innovation of their unique and original creative practice because of an ‘obsession with manufacturing a picture of its uniqueness in contrast to currently existing research’ (McNamara Citation2012, 12). On the one hand, there is a need to engage with the material nature of creative practice and on the other, there is great potential to be realised when PLR can find new connectabilities with other research approaches – whilst also preserving its unique qualities and maturing itself through these interactions. The following case-study aims to illustrate how this might be navigated.

Bringing it all together with a PLR and OEP illustration

This paper presents a view of PLR as a research methodology that incorporates the fluidity of practice into the research design as part of the research output. In so doing, PLR can generate new knowledge about practice in and through practice itself. To realise the transformational and creative work of OEP, the open education practitioner must be responsive to all facets of university life: peoples, environments, technologies, cultures, beliefs and policy, an intricate meshwork of entangled connections. The following speculative illustration aims to give a tangible case-study that shows how PLR methodology can be applied to an OEP research project. The case-study has been adapted from the creative arts, Unstable Acts: Case study – Exemplifying Multi-methods Led by Practice (Haseman Citation2010, 152–155).

Speculative case study – open education unit redesign: Case – study – A multi-methods approach led by practice

Context

This speculative case study responds to the research question:

How might quality open learning experiences be designed to "balance privacy and openness in their use of social and participatory technologies at four levels: macro (global level), meso (community/network level), micro (individual level), and nano (interaction level)"? (Cronin 2018, 3)

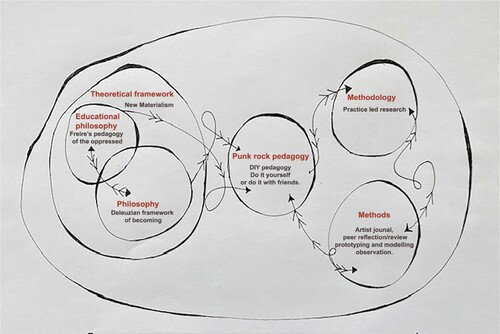

Figure 3. Hamilton, D. (2023). Speculative PLR research project design: Case study: Integrating OEP in a unit Redesign through a PLR approach.

The open practitioner-researcher approaches the research/redesign process by adopting and adapting new hybrid, mutant research methods consistent with their personal approach to educational practice. For this illustration, the inquiry cycle from action research, reflective practice, and diagrammatic analysis offers malleable methods open to emergent processes and practices. However, selecting these methods is arbitrary; their inclusion demonstrates that PLR is a friend to other methodologies, methods and research strategies and can incorporate them into the research process confidently and comfortably (Smith and Dean Citation2009). The critical distinction between PLR and other methodologies is how the researcher engages with particular methods rather than which ones they select because, at all times, the practice-led researcher is making decisions, weaving forward to backward and backward to forward through the emergence and complexity of creative inquiry. Significantly, the methods move with the inquiry and not the reverse. Practice-led data amasses throughout the lifecycle of a creative OEP project through ‘journaling’ processes unique to the researcher/practitioner.

1. Inquiry cycle from action research

Usually the design, delivery, assessment and evaluation of unit development projects happen across multiple development cycles that require the practitioner researcher to plan a change, act in/on and observe the consequences of the change, reflect on the happenings and replan, and so on (Efron and Ravid Citation2019). The Inquiry cycle offers the PLR researcher a method that might be used in whole or in part, depending on the demands of the practice. Practice-led researchers are content to scavenge methods as their practice demands and are little troubled that they are not using the entire apparatus of action research and its other defining features.

2. Reflective practice and the artist journaling process

A model of structured reflection (found in nursing) by Christopher Johns (Citation1994) might be adopted as an effective way of adopting the twin perspectives of ‘looking out’ and ‘looking in’, which, for the open practitioner, offers a series of prompts for reflecting on the aesthetics and ethics of practice (Haseman and Mafe Citation2009). The practitioner/researcher is constantly making decisions; they document in real-time, through process journaling, practice unique to the individual. They do so to keep up with the ever-present emergence of the research and how new knowledge evolves and erupts during the study. Haseman and Mafe (Citation2009) write that "to cope with the 'messy' research project in such a way requires practice-led researchers to have an understanding of not only emergence but its constituting condition of complexity" (217). Reflective practice may be adapted as a compliment to the process journal to properly apprehend practice insights accumulated throughout the development process.

3. Diagrammatic analysis – on the practitioner researchers own creative output

Examples of artefacts collected include practice journals, drawing journals, site writing, prototypes, conceptual mock-ups, observations, code, multi-modal assets, peer review, and feedback. For example, journals should be understood as opportunities to think aloud, problem solve, and create rather than to retrospectively document events. The critical aspect of this mode of data collection is that the researcher generates artifacts from their practice activities. The artifacts produced in practice may be viewed as the cooled sediments of once-fluid action. Throughout the research process, they can be analysed as physical artifacts of how a practice emerged.

Analysis of process artifacts might entail the adoption of diagrammatic analysis. Commonly used in the socio-material analysis of digital platforms, diagrammatic analysis asks the researcher to look beyond textual evidence and collect visual evidence (artifacts can include photographs, diagrams and dashboards) by paying particular attention to the relations at play between the visual and textual elements of digital platforms and how bodies are moved in time and space through interactions that make bodies behave in particular ways (Decuypere 2018, 4). However, in this case, the practitioner generates the artifacts rather than collecting external artifacts to inform practice.

4. Unspecified – tool or technique as method

The limits of a particular teaching method or established educational technology tool might be found in creating open educational research or creating open communities in teaching a learning environment – a new method might emerge by adapting or inventing a fit-for-purpose solution. In effect, research methods can arise from or in direct relation to specific and anachronistic methods familiar to and regularly used by the practitioner /researcher’ (Haseman Citation2010, 154). PLR researchers develop methods specific to their practices and they do not always turn to other disciplines in their research processes. Practice intelligence accumulates through action and interactions with materials, which Bolt (Citation2014) conceptualises as handleability, described as "[T]he double articulation between theory and practice, whereby theory emerges from a reflexive practice at the same time that practice is informed by theory" (29). In this respect, handleability and materiality are not limited to the world of things or objects but to a dynamic and process-oriented relationship between ideas, environments, bodies (human and non-human) and technologies. This is material thinking in action, and material thinking IS the logic of practice itself. PLR then positions materials not as passive objects to be moved about and arranged according to the subjective desire of the practitioner but as "materials and processes of production [that] have their own intelligence that comes into play in interaction with the artist's creative intelligence" (27). Thus, the practice-led researcher theorises out of practice, rather than applies theory to practice.

This case study highlights that PLR is, at its core, inverts the traditional research process. As a performative paradigm, it begins with the unknown and works towards the known. New and existing knowledge structures can be interrogated as they arise through creative action. The practitioner becomes both the researcher and the researched; "the process changes both perspectives because creative and critical inquiry is a reflexive process" (Sullivan Citation2009, 51). A critical aspect of the PLR assemblage is that its methods are contingent upon how the research accounts for the relationship between theory and practice. It seeks to understand and improve both – within a complex and evolving research milieu. Indeed, a fundamental characteristic of PLR is that the researcher introduces their own "anachronistic research methods […] extracted directly from their usual working practices" (Haseman Citation2010, 155). While PLR uses multiple methods, the practice-led researcher does not slavishly follow them, preferring to adapt methods to suit their purposes. PLR is more than a quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods approach because it is built directly from the performativity of the researcher's professional practice. A position that holds great potential in discovering and instantiating a uniquely Australian approach to OEP informed by open educational practitioners themselves.

In conclusion: speculations on PLR and open educational practice

If OEP is to fulfil its potential to usurp 'education as usual', respond to a rapidly changing world, and transform the Australian higher education system, research must play a crucial role. The challenge lies in how to engage with the meshwork and complexity of the swirling forces of life, holding together just long enough to create new meaning, modes of collaboration and educational trajectories capable of anticipating a people and a world to come. This paper is speculative and advocates for the productive and generative relationship between PLR and OEP. The transdisciplinary nature of this research mode is expected to give rise to new practices, approaches and propositions that will occur alongside the emergence of the field of OEP in Australia. Undoubtedly, important empirical studies and more traditional studies must also be undertaken in this space because this project demands multiple perspectives and points of view.

However, stepping into the unknown through a PLR approach is a way of apprehending such complexity and emergence. We assert the unique contribution PLR can make beyond the creative arts, to the broader field of open educational research because it privileges practice and the practice wisdom of practitioners themselves. There is great dignity in not knowing, seeking, and finding new ways of thinking, knowing and being through research, whatever the methodology. Beyond a hierarchical conceptualisation of research excellence, the shock of new modes of encounter found through creative research must not be underestimated. PLR is a valuable research methodology in higher education that can engage uniquely with the complexity and the 'messy' of the open educational assemblage. Practice-led researchers are critical as they understand how to fearlessly navigate a fragile and constantly evolving research landscape. In this regard, we assert the performative power of PLR and its significant potential to unlock the transformative potential of OEP and broaden methodological horizons beyond traditional qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches.

The authors are immensely grateful to the reviewers for their generous engagement with the manuscript's early versions and their suggestions for revision. Their investment in improving this paper embodies the spirit of openness advocated for in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anderson, T., and J. Shattuck. 2012. Design-based research: A decade of progress in education research? Educational Researcher 41, no. 1: 16–25. doi:10.3102/0013189X11428813.

- Andrade, A., A. Caine, R. Carneiro, U. Ehlers, C. Holmberg, A.-K. Kairamo, T. Koskinen, et al. 2011. Beyond OER – Shifting Focus to Open Educational Practices: OPAL Report.

- Biesta, G. 2009. Good education in an age of measurement: on the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 21, no. 1: 33–46. doi:10.1007/s11092-008-9064-9.

- Bolt, B. 2014. The magic is in the handling. In Practice as research: approaches to creative arts enquiry, 27–34. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Bourdieu, P. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Stanford University Press. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=78c48fd0-9846-3d45-9878-f67fdf2ec702.

- Brandenburger, B. 2022. A multidimensional and analytical perspective on open educational practices in the 21st century. Frontiers in Education 7. doi:10.3389/feduc.2022.990675.

- Brown, C., and L. Czerniewicz. 2010. Debunking the ‘digital native’: beyond digital apartheid, towards digital democracy. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 26, no. 26: 357–69. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00369.x.

- Cape Town Open Education Declaration. 2023a. Read the Declaration. Cape Town Open Education Declaration: Unlocking the Promise of Open Educational Resources. https://www.capetowndeclaration.org/read/.

- Cape Town Open Education Declaration. 2023b. Cape Town Open Education Declaration: Ten directions to move open education forward. https://www.capetowndeclaration.org/cpt10/.

- Colebrook, C. 2020. Understanding deleuze. London: Routledge.

- Conole, G.C., and U.-D. Ehlers. 2010. Open educational practices: Unleashing the power of OER, [Paper presentation]. UNESCO workshop on OER, Windoek, Nambia. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ulf-Ehlers/publication/260423350_Open_Educational_Practices_Unleashing_the_power_of_OER/links/5765783508ae421c4489d247/Open-Educational-Practices-Unleashing-the-power-of-OER.pdf.

- Coole, D., and S. Frost. 2010. New materialisms: ontology, agency, and politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Cordova, R. 2016. DIY punk as education: from Mis? education to educative healing. Charlotte: IAP.

- Cronin, C. 2017. Openness and praxis: exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 18, no. 5. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096.

- Davis, O. 2023. The Languaged Exterior and the Felt Interior’: Undercurrents of Logocentrism within Practice-Led Research Scholarship. April. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct = true&db = ir01089a&AN = deun.article.1743&site = eds-live&scope = site.

- Decuypere, M. 2019. Open education platforms: theoretical ideas, digital operations and the figure of the open learner. European Educational Research Journal 18, no. 4: 439–60. doi:10.1177/1474904118814141.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1996. What Is philosophy? New York: Columbia University Press.

- Dewey, J. 1904. The relation of theory to practice in education. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education 5, no. 5: 9–30. doi:10.1177/016146810400500601.

- Dolphijn, R., and I. V. Tuin. 2012. New materialism: interviews & cartographies. Open Humanities Press.

- Dunn, K. 2016. Global punk: resistance and rebellion in everyday life. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Efron, S.E., and R. Ravid. 2019. Action research in education: A practical guide. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Ellis, C., and T.E. Adams. 2020. Practicing autoethnography and living the autoethnographic life. In The Oxford handbook of qualitative research, 2nd ed., ed. Patricia Leavy. Oxford Handbooks, Oxford Academic. https://doi-org.ezproxy-b.deakin.edu.au/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190847388.013.21

- Fox, N.J., and P. Alldred. 2015. New materialist social inquiry: designs, methods and the research-assemblage. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18, no. 4: 399–414. doi:10.1080/13645579.2014.921458.

- Freire, P. 2018. Pedagogy of the oppressed: 50th anniversary edition. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Gorur, R., and J. P. Koyama. 2013. “The struggle to technicise in education policy. deakin university.” Journal Contribution. https://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30074816

- Haseman, B. 2010. Chapter 11 rupture and recognition: identifying the performative research paradigm. In Practice as research: approaches to creative arts inquiry,147–58. New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

- Haseman, B., and D. Mafe. 2009. Chapter 11 acquiring know-How: research training for practice-led researchers. In Practice-led research, research-led practice in the creative arts,211–28. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. doi:10.1515/9780748636303-012

- Inamorato, A. D. S. 2018. Going open: policy recommendations on open education in Europe (OpenEdu policies). JRC Publications Repository

- Inamorato, A. D. S., Y. Punie, and M. J. Castaño. 2016. Opening up education: A support framework for higher education institutions. JRC Publications Repository.

- Johns, C. 1994. Nuances of reflection. Journal of Clinical Nursing 3, no. 2: 71–4. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.1994.tb00364.x.

- Kahn-Egan, S. 1998. Pedagogy of the pissed: punk pedagogy in the first-year writing classroom. College Composition and Communication 49, no. 1: 99–104. doi:10.2307/358563.

- Kavanaugh, L. 2008. Situating situationism: wandering around new babylon with mille plateaux. Architectural Theory Review 13, no. 2: 254–70. doi:10.1080/13264820802216874.

- Knox, J. 2013. Five critiques of the open educational resources movement. Teaching in Higher Education 18, no. 8: 821–32. doi:10.1080/13562517.2013.774354.

- Kontturi, K.-K. 2018. Ways of Following. London: Open Humanities Press. Disponível em: Acesso em: 23 January. 2024. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id = e55c82c4-fda7-37c0-8a09-454045c85fbe.

- Lane, A. 2009. The impact of openness on bridging educational digital divides. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 10: 5. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v10i5.637.

- McAndrew, P. 2010. Defining openness: updating the concept of "open" for a connected world. Journal of Interactive Media in Education 2010, no. 2: 10. doi:10.5334/2010-10.

- McNamara, A. 2012. Six rules for practice-led research. TEXT 16, no. Special 14. doi:10.52086/001c.31169.

- Mulder, F., and B. Janssen. 2013. Opening Up Education. In Trend Report: Open Educational Resources 2013.

- OpenEd19. n.d. About the open education conference. https://openeducationconference.org/about.

- Pascal, C., and T. Bertram. 2012. Praxis, ethics and power: developing praxeology as a participatory paradigm for early childhood research. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 20, no. 4: 477–92. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2012.737236.

- Philippakos, Z.A., E. Howell, and A. Pellegrino, eds. 2021. Design-based research in education: theory and applications. Guilford Publications.

- Romero, N. 2019. Pilipinx becoming, punk rock pedagogy, and the new materialism. International Education Journal 18: 40–54.

- Schatzki Theodore, A. 2001. Introduction: practice theory. In The practice turn in contemporary theory, eds. T Schatzki, K Knorr Cetina, and E von Savigny, 1–14. London: Routledge.

- Schön, D.A. 1991. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Taylor and Francis. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id = 9c5cfb07-c263-3e6c-a301-cbcd0a678515.

- Smith, H., and R.T. Dean. 2009. Practice-led research, research-led practice in the creative arts.

- Stagg, A. 2021. The ecology of the open practitioner: A conceptual framework for open research. Open Praxis 9, no. 4: 363–71. doi:10.5944/openpraxis.9.4.662.

- Stagg, A. 2022. “The Ecology of Open Educational Practices in Australian higher education: a practitioner-focused mixed methods study”, (PhD Thesis, Tasmanian Institute for Learning and Teaching), 255-258. University of Tasmania.

- Stagg, A., L. Nguyen, C. Bossu, H. Partridge, J. Funk, and K. Judith. 2018. Open educational practices in Australia: A first-phase national audit of higher education. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 19, no. 3.

- Stagg, A., H. Partridge, C. Bossu, J. Funk, and N. Linh. 2022. Engaging with open educational practices: mapping the landscape in Australian higher education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 1–15. doi:10.14742/ajet.8016.

- Sullivan, G. 2009. Chapter 2 making space: The purpose and place of practice-led research. In Practice-led research, research-led practice in the creative arts,41–65. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. doi:10.1515/9780748636303-003

- UNESCO. 2016. Education for people and planet: creating sustainable futures for all Global education monitoring report. https://doi.org/10.54676/AXEQ8566.

- UNESCO. 2023a. The Right to Education. June 26. https://www.unesco.org/en/right-education.