ABSTRACT

University governing bodies, especially academic boards, play a crucial role in policy formation. However, due to the predominance of managerial values over academic values in the policy-making process, a persistent divide exists between policy formulation and implementation. This divide results from the marginalisation of academics and the dominance of managerial authority figures within these bodies. Our study investigates the latter to determine the precise Foucauldian apparatus used by authority figures to influence policy-making meetings. Using an innovative arts-based method, we analyse ethnographic vignettes through a Foucauldian lens and transform them into collages depicting the apparatus used by authority figures: Strategic Managerial Monumentalism, Managerial Historical Revisionism, Managerial Discursive Dominance, Managerial Panoptic Surveillance, and Managerial Normalisation. We contend that only a well-defined separation of governance powers can effectively counter the encroachment of managerialism and uphold the democratic representation of academic values in university policies to bridge the policy-practice divide.

Introduction

In the theatre of life, we often find ourselves playing the part of either the puppet or the puppeteer. Our title borrows the term ‘pulling the strings’ from the world of puppetry, as it effectively captures the dynamics of power described by Foucault (Citation1972, Citation1982) and those observed in our research. Foucault’s theory of power describes a complex interplay of control and submission pervading all social interactions. Our actions are constantly being shaped by the actions of others (we have our strings pulled), and our own actions also shape the choices of others (we pull the strings). All of us, on the Foucauldian view of power, alternate between being a puppeteer and a puppet, and this often happens without conscious knowledge or intent.

Universities (being part of society) are a site of power relations (Deem et al., Citation2007). At the core of these relations are institutional policies, often required by government regulation (‘Higher Education Standards Framework (Threshold Standards)’, 2021) and endowed with formal authority and symbolic power (Bleiklie & Kogan, Citation2007). However, a gap exists between the articulated policies and the practices of academic and professional staff. This is known as the policy-practice divide (Margetts et al., Citation2023a; Shore & Wright, Citation1999) and manifests as resistance to policy requirements by both professional and academic staff. This paper focuses on the experience of the academy; i.e., all academic staff. The existing literature espouses the academy’s limited sway within governance entities that are responsible for the development and approval of these policies (Kolsaker, Citation2008). Consequently, institutional policies often project an image of aligning with academic values while, in reality due to the policy-practice divide, they do not (De Boer et al., Citation2007).

In order to gain a deeper understanding of the policy-practice divide, the literature calls for empirical research into the power dynamics present in university governance practices, specifically academic boards and their equivalents (Rowlands, Citation2013a). This is the aim of this paper. Based on an ethnographic study of the process of policy development over several academic board meetings, we combine a Foucauldian analysis of power relations with the arts-based technique of collage (Margetts et al., Citation2023) to visualise the power relations at play. This allowed us to capture how power relations were established and how they influenced the discourse that unfolded on what was akin to a theatrical stage during the ‘production’ of a new policy by an academic board.

Our findings reveal a stage filled with actors who, depending on the circumstances, exert control or are controlled. Puppeteers exercise power when pulling the strings of others, but their behaviour is structured, enabled, and constrained by internal and external pressures which serve to reinforce the values of managerialism. While it is known that university academic boards produce institutional policies that reflect managerial rather than academic values (Giroux, Citation2002; Shattock, Citation2005), our findings shed light on the power mechanisms and strategies employed by senior figures to influence the actions of others and steer the course towards managerial outcomes.

Academic boards and the policy-practice divide

Numerous scholars have analysed the policy-practice divide (Baak et al., Citation2021; Freeman, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Harvey & Kosman, Citation2014; Maassen & Stensaker, Citation2019; Margetts et al., Citation2023a; McCaffery, Citation2018; Morley & Gandin, Citation2010; Singh et al., Citation2014; Skerritt et al., Citation2021; Trowler, Citation2002). In higher education, this divide is frequently attributed to two factors: the exclusion of academic staff from the policy-making process (Sabri, Citation2010), which leads to resistance to policy in practice (Becher & Trowler, Citation2001; Jayadeva et al., Citation2021; Margetts et al., Citation2023a; Petersen, Citation2009; Raaper, Citation2016), and the dominance of senior actors over the operation and decision-making processes of the policy-making bodies (Rowlands, Citation2013b). Empirical research suggests this dominance takes the form of governance and organisational structural change leading to tighter ‘vertical steering’ and ‘tightly coupled’ organisations through which the move to ‘organisational policies’ ‘has been less successful’ (Maassen & Stensaker, Citation2019, pp. 456,465). On these views we would posit the modern university has been captured by a managerialist ideology which has coercively excluded traditional academic values. Additionally, these portrayals potentially oversimplify the issue and may disregard the intricate interplay of power dynamics, ideologies, and latent structures. These elements intricately shape the policy process ‘behind the scenes’ to assert influence and control. If these subtle forms of power remain in place, the quest for greater academic involvement in decision-making may prove futile.

A key governance mechanism of all Australian universities is the academic board (also called academic senate or academic council) (Rowlands & Rowlands, Citation2017). As the case study university is Australian-based, we use the term ‘academic board’. These boards are perceived to serve several purposes, including the maintenance of academic standards and, particularly within the case study university, the review and provision of advice on the development and effectiveness of policy relevant to teaching and research. Typically, academic boards consist of members appointed by the university council and those elected by academic staff (Dooley, Citation2007). They are often conceived as an independent body that functions to balance the authority of university councils and executive management, despite these other entities also maintaining a presence on the board. In this regard, academic boards are considered ‘the embodiment of bicameral governance’ (Dooley, Citation2007, p. 5), hailed as ‘the voice of the academy’ (Winchester, Citation2007, p. 1).

Theoretical background

Power

We often think of power in terms of conscious and overt control. This view aligns with many influential accounts of power in the social sciences, which define power as the ability to make others behave in ways they would prefer not to (Dahl, Citation1957), or to exclude others from decision processes (Bachrach & Baratz, Citation1962). This type of power is no doubt important, but power can also be exerted in more subtle ways. Foucault provides a useful framework for conceptualising and identifying these less visible forms of power.

At the most general level, Foucault sees power as a mode of action which does not act directly on other people, but rather on their actions. Power, in contrast to violence, does not aim to directly move or change the physical body (e.g., by physically moving a person into a jail cell) or other elements of the physical world (e.g., by locking the cell door). The threat of force may be an instrument of power, but the defining feature of power is the attempt to influence behaviour (Foucault, Citation1982). Foucault illustrates this concept through the dual meanings of the word ‘conduct’: one meaning being to guide or direct, and the other referring to an individual’s manner of behaving (Foucault, Citation1982, p. 789). When we exercise power, we essentially conduct (i.e., guide) someone else’s conduct (i.e., behaviour); we pull their strings.

Power assumes diverse forms. As the ‘total structure of actions’ used to influence others ‘it incites, it induces, it seduces, it makes easier or more difficult; in the extreme it constrains or forbids absolutely’ (Foucault, Citation1982, p. 789). Power is not something possessed by individuals, but rather arises from collective social interactions. ‘Power exists only when it is put into action’ (Foucault, Citation1982, p. 788).

Power does not simply flow downwards from rulers to the ruled but is a force exercised by everyone over everyone else. Power is a fundamental aspect of social existence, not an anomaly to be removed in the pursuit of justice. Thus, when we claim in this study that one actor exercises power this should not be taken as a condemnation of their actions. Since power exists in all social relations, one cannot criticise a social relation simply by pointing out that power is involved. This is not to say that particular configurations of power cannot be criticised; only by identifying power relations can they be questioned and resisted (Foucault, Citation1982, pp. 791–792). From a normative perspective, our concern is focused on enduring and oppressive patterns of power, not power as such (Foucault, Citation1982, pp. 791–792; Hindess, Citation2006, p. 116).

For Foucault, power can exist without conscious intent or the awareness of those on either end of the strings (Akram et al., Citation2015, pp. 356–357). This crucial insight shapes our analysis. When we claim that one actor exercises power over another or perpetuates power through processes like monumentalisation, we are not claiming that this occurs with deliberate awareness or intention. Instead, following Foucault, we claim that actors are influenced by the discourse and institutional context in which they are embedded. This influence often elicits actions that inadvertently reinforce existing power (Foucault, Citation1982, pp. 30–33; Lukes, Citation2021).

Enunciative fields

To provide a framework for our analysis of power relations within the context of an academic board, we must acknowledge Foucault’s ‘archaeological’ approach (Foucault, Citation1972), which seeks to unearth the concealed structures that define the actions available to actors in a specific setting. These structures establish the prerequisite conditions for action, including the exercise of power. Foucault calls these concealed structures ‘discursive formations’ (Citation1972, p. 34) or ‘enunciative fields’ (Citation1972, p. 57). We opt to use the latter term.

The enunciative field is constituted by the interaction of ‘statements’ and ‘monuments’ (Foucault, Citation1972, pp. 7, 89–98). Statements are not mere utterances; rather, they combine language and symbols to evoke emotional reactions or create monuments. Statements direct our thoughts and behaviours to serve the interests of the power structure. Consequently, the enunciative field emerges as a structure that sets the limits for what can and cannot legitimately be stated.

Monuments are not passive relics of the past, but rather tangible evidence or material remnants of past discourses, such as documents or other artefacts and structures, that can actively shape our perceptions of the past, present, and future through the historical process (Foucault, Citation1972, pp. 50–63). Monuments serve as crucial anchors within discourses, providing coherence and stability, and influence the boundaries of discourse, manifesting in various forms such as statements within documents, architectural arrangements of meeting spaces that highlight preferred behaviours, and institutional frameworks that dictate what should be discussed.

Foucault (Citation1972, p. 137) argues that history is a tool wielded by power entities, as it is the process by which they select significant monuments and use them to form new statements about the present. He describes the practice of history as ‘historical retro-version[ing]’ (Foucault, Citation1978, p. 150), in which an authority figure constructs a truth of the past by strategically summoning monuments into the present to influence our thoughts and actions. Consequently, monuments can serve as potent historical symbols and play a crucial role in shaping collective memory. By evoking certain narratives more than others, monuments determine which narratives endure and obscure an alternative historical perspective, a process known as historicising or historical revisionism (Krasner, Citation2019).

To explain how the enunciative field relates to power, we draw an analogy from dramaturgy (Goffman, Citation1959): imagine the enunciative field as a theatrical stage, complete with props, costumes, lighting and sound design, as well as the rigging and machinery of the backstage area. This space, or field, as Foucault calls it, functions as an apparatus that shapes and regulates what can be said and done (enunciable), while at the same time acting as a mechanism that restricts or prevents other possible performances from occurring. Foucault (Citation1972) argues that if one holds the controls over an enunciative field – the apparatus – not only can one control what is said and done, but one can also craft what is recognised as historical knowledge, which exerts a profound influence on our interpretations of both the past and present and acts as a monument or guide to our future actions.

Foucault (Citation1972) believed that discourse unfolds within an enunciative field guided by established norms, similar to a theatrical production in which actors adhere to scripts and cues to convey a narrative. In this context, a discourse can be viewed as a choreography of ideas, concepts, and subjects that shapes our understanding and interpretation of the world; a stage on which power struggles are enacted through a series of interconnected statements and monuments.

Theoretical framework – a Foucauldian analysis of university managerialism

The discourse of contemporary university policy has come to be dominated by the assumptions and values of managerialism. In essence, statements, monuments and practices are managerial because they exaggerate or overemphasise (at the expense of other functions) the efficacy and power of ‘the manager’ of an organisation (Klikauer, Citation2023a).

In higher education, academics experience the effects of managerialism through the implementation of ‘absurd’ policy which does not cohere with academic values or the day-to-day realities of teaching and research (Ball, Citation2021; Croucher & Lacy, Citation2020; Deem, Citation2004; Margetts et al., Citation2023a, p. 1; Marginson, Citation2013; Marginson & Considine, Citation2000; Shattock et al., Citation2019; Webb, Citation2014). Managerialism in the contemporary university emphasises neoliberal value and business-like operations, reducing academics to service providers and students to consumers (Anderson, Citation2008; Bosetti & Heffernan, Citation2021; Bottrell & Keating, Citation2019; Connell, Citation2019; Kinman, Citation2014; Marginson & Considine, Citation2000; Morley, Citation2001; Naidoo & Jamieson, Citation2005; Warren, Citation2017; Wheeldon et al., Citation2023b; Winter et al., Citation2000). It also centralises operations and instals an audit culture of performance monitoring which privileges quantifiable outcome measures (Deem & Brehony, Citation2005; Jones et al., Citation2020; Parker et al., Citation2019). This undermines the academic values of knowledge-seeking, open and critical discourse, and collegial decision-making (Wheeldon et al., Citation2023a, Citation2023b, Citation2023c). Of note is that senior academics do take on academic leadership roles and may lead policy development. This complication is acknowledged but is outside the scope of this paper.

As we emphasised earlier, power in the Foucauldian sense is an inherent part of social life. We argue, however, that managerial discourse in contemporary universities has produced a stable and repressive set of power relations. To provide a theoretical framework for our analysis, we take a Foucauldian lens to university managerialism and identify its basic commitments. We call this ‘the managerialist charter’. It can be divided into three Foucauldian elements: the monumental, the historical, and power relations.

The managerialist charter

Monumental beliefs

Monumental beliefs ascribe monumental significance to the manager as a subject and emphasise their power and authority.

Managerial hierarchy as the sole source of decisions: Only managers organised in hierarchical structures have decision-making authority and the decisions of senior managers take precedence (Klikauer, Citation2015; Citation2023a, p. 78).

Implementation, not influence: Although never explicitly stated, employees are only responsible for implementing decisions and should have very little input in decision-making processes; it can be beneficial if they believe they do however (Goh, Citation2017; Margetts et al., Citation2023b).

Intra-hierarchical evaluation: Performance evaluations flow from top down, with senior managers evaluating those who directly report to them; this reinforces the power dynamics and preserves the hierarchy (Fleming, Citation2021).

Privileged voices and spaces: Managers are solely responsible for certain organisational tasks, and their voices should be privileged through various means (Locke & Spender, Citation2011), such as the architectural layout of offices and meeting spaces (Våland & Georg, Citation2018).

Historical beliefs

Historical beliefs maintain and uphold the universality, virtue, and moral rectitude of the manager as a necessary and beneficial force to be valued by society over time.

Universality of managerial capabilities: Only managers possess the sophisticated skills and abilities necessary to run organisations (Locke & Spender, Citation2011). Their capabilities are universally applicable to all types of organisations because differences in the nature of the work are irrelevant (Klikauer, Citation2023b).

Managerial virtues: Profitability is a virtue (Gare, Citation2019). And for the purpose of maximising profit through cost reduction, efficiency is also virtuous (Pollitt, Citation2016). However, the greatest virtue is to respect and not question (Courpasson et al., Citation2012) the decisions of superiors (Klikauer, Citation2023a, pp. 176, 201).

Morally commendable: Managers play a vital role in the operation of organisations by making decisions that affect the lives of many (Mirvis, Citation2014); consequently, managers as moral agents have the right to manage (Shepherd, Citation2018) and should be commended and remunerated for their efforts (Braverman, Citation1998).

Power relation beliefs

Power relation beliefs highlight the establishment and perpetuation of the hierarchical managerial system, with an emphasis on power concentration at senior levels and differential treatment between levels. These beliefs also emphasise surveillance, control, and senior-level immunity.

Panopticon of managerial hierarchy: It is only permitted for superior managers to appoint subordinate managers (Diefenbach, Citation2013). Consequently, managerial values permeate organisational layers, resulting in the formation of a surveillance network in which individuals serve as both the subject and the agent of power.

Senior immunity: Senior managers are exempt from the rules that apply to their subordinates and employees (Magee & Galinsky, Citation2008). Power is exercised through a series of subtle micro-practices, such as ignoring meeting protocol and speaking without directing comments through the chair.

The case

Like other Australian universities, our case university operates within an increasingly regulated environment (Marginson & Considine, Citation2000) and its constituting act requires that the university’s council establish an academic board, determine the membership and decide who is the chairperson. The university’s academic freedom policy is the focus policy of this research study. It investigates the development process by an academic board and its self-appointed working group, as tasked by the university council in response to a request by the Australian Government’s Minister for Education. The request was that all universities develop an academic freedom policy (Department of Education, Citation2021) and base it on a model code (French, Citation2019). This was subsequently followed by the ‘Review of the Adoption of the Model Code on Freedom of Speech and Academic Freedom (Walker, Citation2020).

Methodology

We combine the arts-based method of collage (Mannay, Citation2010; Margetts et al., Citation2023) and Foucauldian analysis to unearth and visualise power relations based on ethnographic observation. As Foucault (Citation1978, p. 86) puts it: power ‘mask[s] a substantial part of itself’ and ‘is proportional to its ability to hide its own mechanisms’. By using collage to visualise the Foucauldian apparatus, we can reveal the mechanisms of managerial power within a policy-making body.

Following collage techniques of Margetts et al. (Citation2023), ethics approval was obtained and the policy’s development was observed through ten meetings of an academic board. Field notes were gathered and transformed into corresponding vignettes provided in the findings (below). This provided a detailed and rich description of specific moments and interactions, including nuances, contextual information, and emotions, especially those that portrayed the social dynamics and power relations at play. By subjecting each vignette to our Foucauldian questions (Appendix A), each vignette was transformed into a reflexive collage () and assigned a thematic Act and Scene emulating the structure of a performance. Each Act represents a meeting that was observed, for a total of six selected meetings that fundamentally correspond to the policy development phases (Althaus et al., Citation2018); there is no Act 2 because no developments were reported at that meeting. Scenes visually depict the progression of activities within each Act and present the Act’s narrative from beginning to end.

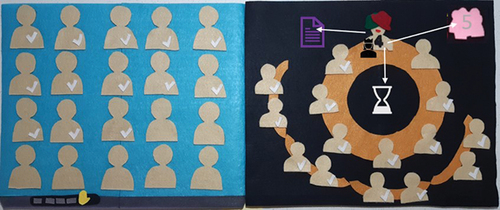

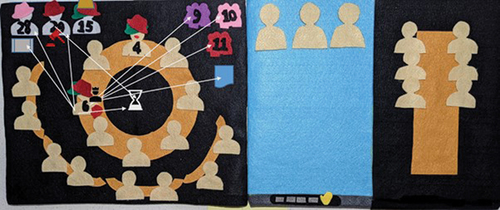

Figure 10. Act 6 Scene 2 - Silent strings and unspoken commands: A masterclass in academic puppetry.

As part of the collage-making procedure, we derive questions from Foucault (Citation1972) to analyse the language, rhetoric, and behaviour portrayed in the vignettes. The questions sought statements that reflected and reinforced managerial values, investigated the power dynamics wielded by authority figures in the meetings, and probed how these figures framed discussions and decision-making processes. In addition, they investigated how dissenting voices or alternative perspectives were silenced or discouraged, and how authority figures controlled the enunciative field by applying the power they held to influence the perception of issues and decisions to align with managerial values. To improve the visual representation of the findings, we created collage iconography (Appendix B).

Findings

Following the creation of the collages, we were able to apply our theoretical framework and search for the manifestation of managerialist beliefs: the monumental (monumentalising), the historical (historicising), and the power relations. Our findings, presented in Acts and Scenes, reveals each of these and we draw attention to the relevant icons in brackets.

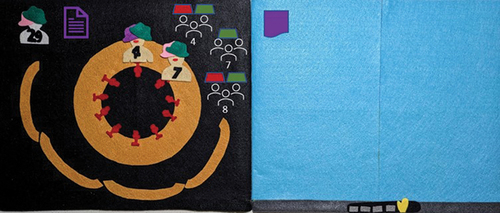

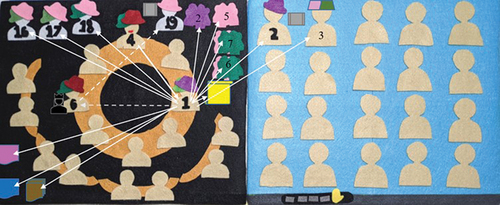

Act 0 scene 0 – behind the puppeteers’ curtains

This vignette was based on post-hoc policy development insights. The collage was developed retrospectively to reflect the stage, props and policy development structures. The management of academic board meetings involves subtle mechanisms through which managerialist values are reinforced. These performances create the impression of open and inclusive leadership for the university’s highest academic governance body (Group 4) and the Australian Government (Group 7 and Actor 29).

The spatial arrangement of the physical meeting chamber monumentalises the managerial hierarchy by positioning senior members in the inner circle equipped with microphones (, left panel). Voting is generally conducted through the raising of physical hands, making conduct visible. The board’s executive committee (Group 8) controls the agenda (purple book) for all meetings. This allows them to shape the enunciative field by favouring in-person meetings and controlling the topics and motions under discussion. These factors allow senior managers to exercise power over others in the meeting chamber to garner their support. The appearance of collective decision-making is maintained, but in reality, the stage is set to steer the board towards managerial outcomes.

The transition to online Zoom meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic (, right panel) temporarily disrupted this staging and challenged the hierarchy. A meeting protocol (purple document) was developed to ‘guide’ meeting behaviours, including the muting of microphones unless asked to speak and use of the ‘raise hand’ button if seeking to speak. During these meetings, only the individual administering the vote (Actor 7, committee support person) could see individual polling choices, reducing the pressure to support the motions put to the meeting by the chair (Actor 4) from the agenda (purple book). Meanwhile, the chat function allowed members to communicate privately with one another.

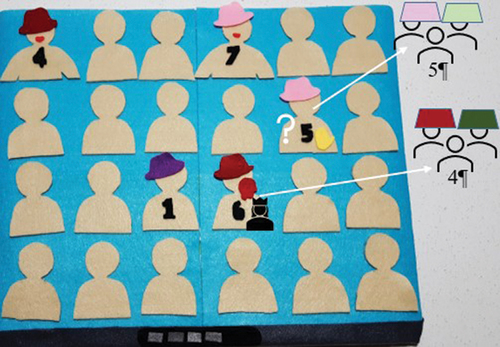

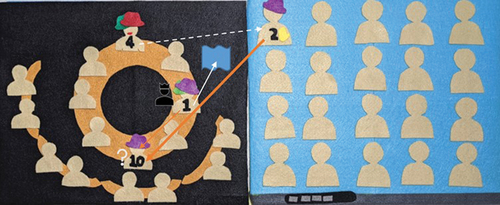

Act 1 scene 2 - power plays and discursive dominance

When Actor 5 seeks permission to speak and questions the policy consultation process (question mark icon), Actors 1 and 6 quickly intervene, bypass the chair (Actor 4) (red face icon) to defend the approach and refer to standard process and the authority of Group 4 (white line icon) to ensure the policy moves forward. This disregard of meeting protocol reveals the immunity of senior managers and clearly signals a gap between ‘de facto’ power and ‘de jure’ authority within the context of the meeting. The capacity to intervene at will suppresses alternative viewpoints and prioritises managerial perspectives.

Actor 6’s defence of the work of Group 4 also involves historicising. Past events are interpreted favourably to justify the approach and are, like all actions in academic board meetings, recorded in the meeting minutes. This has the effect of validating actions and alters the context of future meetings, shaping the enunciative field and creating discursive resources which can later be drawn on. Actor 6 is thus creating monuments which bolster their future authority and influence (monarch icon and dark red ‘power’ hat).

Act 3 scene 1 - carrying the torch for managerialism

Actor 6 is absent from this scene, and they are not explicitly mentioned. Nevertheless, the managerial values they had previously expressed and monumentalised were carried forward by Actors 4 and 1. Actor 4 (chair) referred to Group 4’s role in approving the policy and Actor 1 (working group chair) used authoritative and persuasive language to emphasise the significance of the policy, adding weight to this by referring to numerous validating documentary artefacts, including government documents, legislation, the policies of other universities, the university’s policy repository and previous policy drafts (document icons).

In Foucauldian terms, this scene illustrates the intricate linkage between knowledge, power, and the enunciative field. Documentary artefacts like legislation, policies, scientific findings, and expert judgements are perceived as objective knowledge and authority. However, their impact on behaviour is contingent on their application within specific social contexts, thus serving as a tool of power. Here, it is important to remind ourselves that power in the Foucauldian sense is omnipresent and often benign. The use of evidence and arguments to put one’s case forward is an exercise of power in the sense that it attempts to influence the behaviour of others, but it is also in an obvious sense consistent with academic values. The fact that power is being exercised here is not itself a problem. However, since access to the instruments of power is unevenly distributed, the result may be one of dominance.

Three prerequisites underscore Actor 1’s invocation. First, the availability of authoritative documentary artefacts within the enunciative field. Second, Actor 1’s knowledge in procuring and utilising these artefacts. Lastly, the audience’s acceptance of these artefacts as proof of the statement made.

In this context, the use of artefacts with epistemic or normative force exemplifies ‘ideational power’, as defined by Carstensen and Schmidt (Citation2016). This form of power involves the use of evidence and persuasion to validate an idea or compel an audience to accept an idea, even without complete conviction (Carstensen & Schmidt, Citation2016, pp. 326–327).

The material conditions under which statements are made play a pivotal role. According to Foucault (Citation1972, p. 96), statements must be understood in relation to their discursive environment and the material conditions of their existence. For instance, a senior manager or a working group chair derives authority from their title, which also presents opportunities to gain knowledge of available discursive resources (Margetts et al., Citation2023b). The other board members, who are working academics, may not have the resources or incentives to acquire such knowledge, thus emphasising the unequal distribution of power.

In one sense, the uneven distribution of knowledge and the subsequent variance in influence should come as no surprise and should not necessarily raise objections. Particularly in academic settings, the strength of arguments should ideally steer debates. However, a concern arises when those with greater access to authoritative knowledge wield it to advance a particular set of values and interpret evidence in a manner that favours their perspective, potentially leading to the dominance of their viewpoint within the discourse.

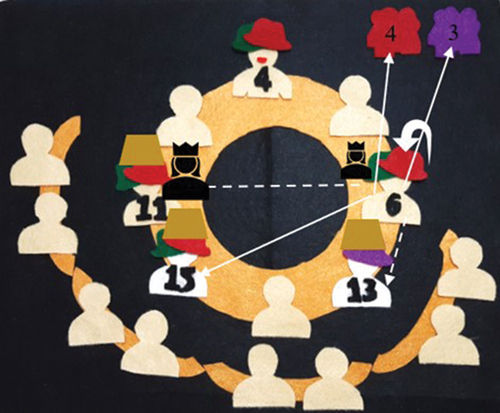

Act 3 scene 4 - how to speak when kings are present

This meeting reveals a change in power dynamics with the presence of Actor 11 (large monarch and gold hat), a member of the powerful Group 4. Actor 6 had previously disregarded meeting protocol in bypassing the chair but now follows protocol. Actor 6’s deference to and praise for Group 4 and its members (Actors 11, 13 and 15) (solid and dashed line icons) can be interpreted as further monumentalisation of the group.

The previous disregard by Actor 6 of meeting protocol contrasts starkly with their current behaviour of waiting to be invited to speak by the chair (Actor 4). This can be interpreted as historicism where present conduct influences perceptions of history when Group 4 is represented. In terms of revealing power relations, Actor 6’s altered behaviour in the presence of Group 4 members indicates that Group 4 possesses substantial power (dark red group icon), with a dominant figure (Actor 6) now having their strings pulled.

Act 3 scene 6 - the clock is ticking

In terms of power relations Actor 6 seemingly relinquishes discourse control and voting to Actor 4 (chair) however Actor 4 is guided by an agenda (purple book), set by a group comprised of actors who form the board, including Actor 6. As previously mentioned, this group is comprised of senior leaders and can decide what is and is not up for discussion and decision, and the sequence of those considerations. They formulate the motions that form monuments and manifest as the second dimension of power.

Actor 4 also engages the pressure of time and political pressure from Group 7 (Australian Government), tactics which from a Foucauldian perspective steer members to take a certain course of action – to vote in favour of the motion, which they obligingly did (white ticks).

As discussed above, power relations in the meetings had already narrowed the range of allowable discourse and discouraged contrary views. The additional discursive constraints of the agenda and the time pressure further limited the range of possibilities and steered the process towards the preferred outcome.

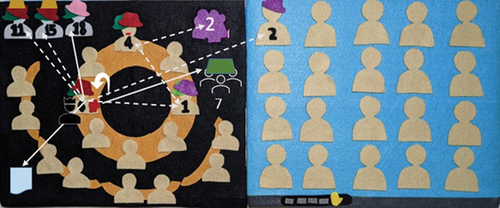

Act 4 scene 2 – back on top of the managerial agenda

Actor 1 enthusiastically expresses gratitude to Actor 6 (dashed white line icon), monumentalising and reinforcing the authority of the latter. Actor 1 again invokes the authority of several powerful groups (Groups 2, 5, 6 and 7) and artefacts to affirm the importance of the policy. They particularly referred to the work of Group 7 (Australian Government) in reviewing the implementation status of academic freedom policies in Australia’s universities. Actor 1 also emphasised past achievements and endorsed past strategies in the policy process, historicising to put a positive spin on history as recorded in the meeting minutes and collective memory.

Act 4 scene 5 - verbal jousting: pressing towards the managerial goal

Actor 4 invites questions from the meeting in this scene. A specific and potentially challenging question (question mark icon) is posed by Actor 10 (elected member) about the policy. Actor 1 (working group chair) responds dismissively and poses a rhetorical question. Actor 2 (working group member) seeks permission to speak through Actor 4 (chair) and provides a substantive response to the question along with some additional background to reassure Actor 10.

The contrasting discursive styles of Actors 1 and 2 are noteworthy. Actor 1 transparently asserts power through condescending and dismissive language (fine orange line icon), while Actor 2 uses knowledge and accepted forms of conduct (thick orange line) to placate the same potential challenge. Both are pursuing the same end of purporting to upholding the legitimacy and quality of the policy process, but with very different apparatuses of power. For Foucault (Citation1982, p. 789), power is the ‘total structure of actions brought to bear upon possible actions’ and can thus take many forms. Actor 1 incites while Actor 2 seduces.

Additionally, Actor 2’s alternative strategies indicate a challenge to the power of Actor 1, hinting at the ongoing struggle for influence within the institution.

There were no further questions in response to actor 4’s invitation.

Act 4 scene 7 - power plays and polite pretences on the board stage

Actor 6 speaks without directing comments through Actor 4 (chair) (red face icon) and expresses profuse appreciation to Actors 1 and 2 and acknowledges the contribution of powerful members of the governing body (Actors 11 and 15) in the policy’s development (dashed white lines). The possible risk of negative feedback from Group 7 (the Australian Government) is simultaneously averted and Actor 6 notes they have had input (curved arrow) into an external report (light blue document). All other members remain silent except for Actor 4 who extends additional thanks to Group 2 (working group) and notes that endorsement and recommendation of the policy to the governing body at the previous meeting had been a positive outcome.

Act 5 scene 3 – management to the rescue

Actor 6 speaks without directing comments through Actor 4 (chair) to update the meeting on the policy’s progress and alert members to some possible negative attention from Group 9 (external media). Members are reassured that any reports of delayed completion are erroneous – unlike some members of Group 10 (all other Australian universities) – and the policy will be submitted by the required deadline (hourglass) set by Actor 29 (Australian Government minister/red gavel), as earlier advised by Actor 6 to Actor 29 and Group 11 (external review panel). The meeting is updated on plans for implementation and gratitude is once again extended to all contributing parties.

This situation presented an opportunity for Actor 6 to monumentalise themselves as a source of power and authority. Their display of power was in their uninvited update on recent information circulated by the media and reassurances to the meeting that the university was compliant and not on the ‘bad list’. Here Actor 6 monumentalises their ability to handle challenges effectively and protect the university’s reputation – whereas the academic board could not. This intervention was a form of historising, as Actor 6 positions themselves as a problem-solver and saviour, a role that might historically have been attributed to the board.

Act 6 scene 2 - silent strings and unspoken commands: a masterclass in academic puppetry

Enter for the first time, Actor 20 (ex officio member of the board and governing body) who expertly influences Actor 4 (chair) to provide an update on an external meeting related to Actor 4’s role as chair; i.e., Group 12 (national academic board chairs). A somewhat miffed Actor 4 quickly recovers, provides the requested update and takes the opportunity to congratulate the case study university on its satisfactory development of an academic freedom policy, incidentally noting that other members of Group 10 (all other Australian universities) were not so well placed. Actor 4 notes that the case study university had met the timeframe set by Actor 29 (Australian Government minister/red gavel), and referred to the roles of Group 9 (external media) and Group 7 (Australian Government). They again express thanks to Group 2 (working group) for helping achieve this outcome.

Here we see both power relations and monumentalism, as Actor 20 directs Actor 4 (chair) to shape the discussion in a particular way, demonstrating Actor 20’s use of power and authority to strategically influence the outcome of the meeting. Historicising is evident in the crafting of a positive perspective by Actors 4 and 20, limiting any receptivity to diverse viewpoints. This subtle act reminds and revises the meeting’s perception of power dynamics and decision-making processes. The scene highlights the influence of perhaps previously hidden ‘higher authorities’ in the strategic decision-making processes within the academic board, challenging any previous assumptions members may have had about its powers.

Discussion

Our aim in this paper has been to identify the Foucauldian apparatus (the strings) that senior managerial figures used to influence academic board. This is important because when a person in a position of institutional authority is involved in the policy-making process, but not presiding over it using direct governing methods (Bacchi & Goodwin, Citation2016), they can strategically direct and control the enunciative field through a variety of means.

The ideal of the academic board is to provide an academic voice into institutional policy development. If academic boards provide the appearance, but not the reality, of academic inclusion in this process they may in fact reinforce rather than moderate the power of managers and the dominance of managerial values. Much like ‘managed democracies’ use rigged elections to provide the appearance of, but not the reality, of democracy (Wegren & Kinitzer, Citation2007), an academic board which is ‘managed’ towards managerial outcomes may in fact disempower those it claims to represent. Managed academic inclusion may legitimate managerial outcomes by obscuring the power relations which give rise to them.

This management of inclusion need not involve any malicious intent to undermine the independence of the board. On the Foucauldian account, power is omnipresent and is often exercised without any conscious awareness or intent through established practises, norms, and discourses which define the boundaries of accepted knowledge and behaviour. Power in this sense is not a purely negative force. Although it can be repressive, power is also a precondition for any form of knowledge and collective action.

Using a Foucauldian lens to create collages that visually represent key moments in the policy-making process, we have identified five elements of the apparatus, which we refer to as: Strategic Managerial Monumentalism, Managerial Historical Revisionism, Managerial Discursive Dominance, Managerial Panoptic Surveillance, Managerial Normalisation.

First: authority figures strategically build managerial monuments through discursive framing (Fairhurst & Sarr, Citation1996) by employing emotionally charged statements (Foucault, Citation1972). This strategic managerial monument building is accomplished by fashioning statements that invoke higher sources of authority to influence their perception and significance. These statements are transcribed into written records, thereby enshrining them as historical monuments, such as agendas and documented minutes of meetings. It also simultaneously prohibits the building of alternative monuments that may challenge or oppose their viewpoint (Mettler, Citation2016). This strategic act of monument building by an authoritative figure serves not only to define current priorities but also lays the groundwork that will, in due course, wield considerable influence in shaping the board’s history. We coin the term ‘Strategic Managerial Monumentalism’ to describe the deliberate building of enduring monuments by an authority figure to consolidate their influence and control over a body over time.

Second: authority figures deliver interpretive statements about existing monuments, thereby reinforcing the prescribed interpretations, and controlling the narrative. While this practise of delivering interpretive statements about existing monuments is known as ‘Historical Revisionism’ or memory politics (Wulf, Citation1989), our study revealed how an authority figure performs this by utilising statements that invoke currently standing managerial monuments or higher-ranking managerial authority figures. This practice, which we call ‘Managerial Historical Revisionism’, enables them to reconfigure the present within the context of historical monuments to suit their purposes, to remind participants of what was important and by inference what was not, and to influence narratives to maintain or shift power dynamics as required. It is also a method for creating the appearance of consistency and coherence in their actions. Act 3 Scene 1 was an example of this, as Actor 1 emphasised the policy’s historical significance by referencing past efforts and developments, thereby justifying its significance within the university’s larger story, and reinforcing its monument-like status and authority.

Third: from a Foucauldian perspective, our analysis uncovers a phenomenon we term ‘Managerial Discursive Dominance’ in the behaviour of authority figures. This manifestation involves a strategic exercise of managerial control over discourse. By intertwining language with their authoritative physical presence, they construct themselves as an institutional monument within the designated enunciative field. This monument resonates with the essence of their language, reinforcing their identity and position as a symbol of authority within the institution. Within this framework, an authority figure’s discourse becomes a tool for asserting power and shaping discourse itself, aligning with Foucault’s (Citation1972) insights into the intricate interplay between power, discourse, and the establishment of monuments within the enunciative field.

Fourth: authority figures employ Foucault’s panopticon-derived ‘Managerial Panoptic Surveillance’. This is accomplished by devising means to make the membership of such bodies feel as though they are under constant surveillance by authority figures, especially during voting and preamble discussions. To avoid potential consequences, individuals are more likely to conform to the dominant discourse when they are aware they are being observed.

During our observations, we determined that it was preferred that members be physically present during voting and discussion preceding a vote. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual meetings presented difficulties for this mechanism, as they were unable to continue in the panoptic spatial configuration of the meeting chamber, and the ability to monitor voting and member interactions diminished. Due to an insistence on the resumption of in-person meetings, the concept of Managerial Panoptic Surveillance was revealed more explicitly, highlighting its role in maintaining control within the enunciative field.

Fifth: when viewed through a Foucauldian lens, our investigation reveals a final layer of observation – ‘Managerial Normalisation’ - in which authority figures uphold communication guidelines, behavioural standards, and interaction models that align with their managerial beliefs, but believe they are exempt from these norms. In our study, while board members waited to be acknowledged by the chair before speaking, Actor 6 almost constantly did not follow the protocol.

This reinforcement of existing hierarchical power dynamics not only regulates discourse but also marginalises voices of dissent, preserving the dominance of senior managerial figures. This dynamic suggests that members of these university bodies have internalised, or been conditioned, to communicate and engage in meetings in manners sanctioned by those in power. This signifies a form of disciplinary control, echoing Foucault’s insights on how institutional mechanisms shape behaviour and establish the boundaries of acceptable participation. In practice what this looks like is that members of these academic boards know no other ways of behaving.

Concluding remarks

Our analysis inspires a nuanced perspective that transcends the characterisation of any one actor as a lone antagonist. Instead, it highlights the intricate web of power dynamics that ensnares all senior members of the university administration under the pervasive influence of managerialism. They operate within a discursive framework in which conformity to managerial norms is crucial to maintaining their positions and salaries. Viewing the actions of Actor 6 as responses to the disciplinary mechanisms embedded within managerialism acknowledges their dual role as both puppeteer (agent) and puppet (subject) within this larger managerial apparatus.

Managerialism’s disregard for the doctrine of the separation of powers is one of its most notable characteristics (Clarke & Newman, Citation1997; Davies, Citation2003; Deem et al., Citation2007). This is reflected in the hierarchical committee structure adopted by universities, that allows governing bodies such as academic boards to be managed by university executive officers like vice-chancellors. The terms of reference for academic boards often imply that these bodies advise the university executive, which puts senior actors in a power position where they can exert their dominance of the decision-making processes and operations (Rowlands, Citation2013b). Our study’s visualisation of power dynamics within policy-making meetings has lifted the curtain on the very apparatus through which these authority figures consolidate their dominance. It reveals the intricate interplay between managerialism, institutional structure, and individual behaviour. It exposes how authority figures wield power while simultaneously being shaped by its constraints.

This study stands as a call to action, echoing Foucault’s stance on understanding and critiquing power dynamics. It urges a reconsideration of how universities structure their governance to ensure a separation of power. Only then will we see a recalibration of power structures and any meaningful change where academic values are embodied in policy. Until then, managerial values will predominate, and the policy-practice divide will persist.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akram, S., Emerson, G., & D, M. (2015). (Re)conceptualising the third face of power: Insights from Bourdieu and Foucault. Journal of Political Power, 8(3), 345–362. Retrieved September 11, 2023 from https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2015.1095845

- Althaus, C., Bridgman, P., & Davis, G. (2018). The Australian policy handbook (6th ed.). [ (1998)]. Allen and Unwin.

- Anderson, G. (2008). Mapping academic resistance in the managerial university [article]. Organization, 15(2), 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508407086583

- Baak, M., Miller, E., Sullivan, A., & Heugh, K. (2021). Tensions between policy aspirations and enactment: assessment and inclusion for refugee background students. Journal of Education Policy, 36(6), 760–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1739339

- Bacchi, C., & Goodwin, S. (2016). Poststructural policy analysis: A guide to practice. Springer.

- Bachrach, P., & Baratz, M. (1962). Two faces of power. The American Political Science Review, 56(4), 947–952. https://doi.org/10.2307/1952796

- Ball, S. J. (2021). Response: Policy? Policy research? How absurd? Critical Studies in Education, 62(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2021.1924214

- Becher, T., & Trowler, P. R. (2001). Academic tribes and territories - Intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines (2nd ed.). SRHE & Open University Press. https://www.researchgate.net/file.PostFileLoader.html?id=559d66595e9d9750378b45e4&assetKey=AS%3A273809418981383%401442292660493

- Bleiklie, I., & Kogan, M. (2007). Organization and governance of universities. Higher Education Policy, 20(4), 477–493. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300167

- Bosetti, L., & Heffernan, T. (2021). Diminishing hope and utopian thinking: Faculty leadership under neoliberal regime. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 53(2), 106–120. Retrieved January 26, 2022 from. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2021.1910219

- Bottrell, D., & Keating, M. (2019). Academic wellbeing under rampant managerialism: from neoliberal to critical resilience. In D. Bottrell & M. Keating (eds.), Resisting neoliberalism in higher education volume I (pp. 157–178). Springer.

- Braverman, H. (1998). Labor and monopoly capital: The degradation of work in the twentieth century. nyu Press.

- Carstensen, M., & Schmidt, V. (2016). Power through, over and in ideas: Conceptualizing ideational power in discursive institutionalism. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(3), 18–337. Retrieved 12 Septenber 2023, from. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1115534

- Clarke, J., & Newman, J. (1997). The managerial state: Power, politics and ideology in the remaking of social welfare. Sage.

- Connell, R. (2019). The good university: What universities actually do and why its time for radical change. Zed Books Ltd.

- Courpasson, D., Dany, F., & Clegg, S. (2012). Resisters at work: Generating productive resistance in the workplace. Organization science, 23(3), 801–819. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0657

- Croucher, G., & Lacy, W. B. (2020). The emergence of academic capitalism and university neoliberalism: Perspectives of Australian higher education leadership. Higher Education, 83(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00655-7

- Dahl, R. (1957). The concept of power. Behavioral Science, 2(3), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830020303

- Davies, B. (2003). Death to critique and dissent? The policies and practices of new managerialism and of evidence-based practice. Gender and Education, 15(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954025032000042167

- De Boer, H., Enders, J., & Schimank, U. (2007). On the way towards new public management? The governance of university systems in England, the Netherlands, Austria, and Germany. In D. Jansen (ed.), New Forms of Governance in Research Organizations (pp. 137–152). Dordrecht, NL: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5831-8_5

- Deem, R. (2004). The knowledge worker, the manager-academic and the contemporary UK University: New and old forms of public management? Financial Accountability & Management, 20(2), 107–128. Article. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0408.2004.00189.x

- Deem, R., & Brehony, K. J. (2005). Management as ideology: The case of ‘new managerialism’in higher education. Oxford Review of Education, 31(2), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980500117827

- Deem, R., Hillyard, S., Reed, M., & Reed, M. (2007). Knowledge, higher education, and the new managerialism: The changing management of UK universities. Oxford University Press.

- Department of Education. (2021). Independent review of adoption of the model code on freedom of speech and academic freedom: Release of Australian government response. Australian Government. Retrieved April 11, 2023 from https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-reviews-and-consultations/independent-review-adoption-model-code-freedom-speech-and-academic-freedom

- Diefenbach, T. (2013). Hierarchy and organisation: Toward a general theory of hierarchical social systems. Routledge.

- Dooley, A. H. (2007). The role of academic boards in University Governance. AUQA occasional Publications(12).

- Fairhurst, G., & Sarr, R. (1996). The art of framing. Jossey-Bass.

- Fleming, P. (2021). The ghost university: Academe from the ruins. Emancipations: A Journal of Critical Social Analysis. https://doi.org/10.54718/MTVL8214

- Foucault, M. (1972). The archaeology of knowledge. Routledge.

- Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality: An introduction. Pantheon Books. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=mI-FAAAAIAAJ

- Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8(4), 777–795. Retrieved September 11, 2023, from https://doi.org/10.1086/448181

- Freeman, B. (2014a). Evaluation of the University of southern Queensland policy refresh project. T. U. o. Melbourne.

- Freeman, B. (2014b). Policy practitioners: Front-loading the policy cycle lessons from the United States, New Zealand, and Papua New Guinea. ATEM Policy Development Forum X. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Brigid_Freeman/publication/272747119_Policy_practitioners_front- loading_the_policy_cycle_Lessons_from_the_United_States_New_Zealand_and_Papua_New_Guinea/links/54ed2b110cf2465f5330d89c.pdf

- French, R. (2019). Report of the Independent Review of Freedom of Speech in Australian Higher Education Providers. D O E A Training. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22media%2Fpressrel%2F6607701%22

- Gare, A. (2019). Philosophical Anthropology and Business Ethics: Reviving the Virtue of Wisdom. In G. Pellegrino & M. Di Paola (eds.), Handbook of Philosophy of Management Handbooks in Philosophy (pp. 693–711). Cham, Vietnam: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-76606-1_6

- Giroux, H. A. (2002). Neoliberalism, corporate culture, and the promise of higher education: The University as a democratic public sphere. Harvard Educational Review from. 72(4), 425–463. Retrieved September 5, 2023, from https://www.academia.edu/download/105403904/43282912080b7af29627b55d966a1f836fe4.pdf https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.72.4.0515nr62324n71p1

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday, Anchor Books.

- Goh, P. C. (2017). Systemic practice and workplace as community: Alternatives to managerialism. Voluntary Sector Review, 8(1), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1332/204080517X14882017380371

- Harvey, M., & Kosman, B. (2014). A model for higher education policy review: The case study of an assessment policy [article]. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 36(1), 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2013.861051

- Hindess, B. (2006). Bringing states back in. Political Studies Review from. 4(2), 115–123. Retrieved September 11, 2023, from https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-9299.2006.000102.x

- Jayadeva, S., Brooks, R., & Lažetić, P. (2021). Paradise lost or created? How higher-education staff perceive the impact of policy on students. Journal of Education Policy, 1–19. Retrieved December 4, 2021, from https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2021.1903083

- Jones, D. R., Visser, M., Stokes, P., Örtenblad, A., Deem, R., Rodgers, P., & Tarba, S. Y. (2020). The performative university: ‘targets’, ‘terror’ and ‘taking back freedom’ in academia. Management Learning, 51(4), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507620927554

- Kinman, G. (2014). Doing more with less? Work and wellbeing in academics. Somatechnics, 4(2), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.3366/soma.2014.0129

- Klikauer, T. (2015). What is managerialism? Critical Sociology, 41(7–8), 1103–1119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920513501351

- Klikauer, T. (2023a). The language of managerialism: Organizational communication or an ideological tool?. Springer International Publishing. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=FWypEAAAQBAJ

- Klikauer, T. (2023b). Managerialism and Leadership. In A. Samad, E. Ahmed, & N. Arora (eds.), Global Leadership Perspectives on Industry, Society, and Government in an Era of Uncertainty (pp. 1–18). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-8257-5.ch001

- Kolsaker, A. (2008). Academic professionalism in the managerialist era: A study of English universities. Studies in Higher Education, 33(5), 513–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802372885

- Krasner, B. (2019). Historical revisionism. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=N7jXDwAAQBAJ

- Locke, R. R., & Spender, J. C. (2011). Confronting managerialism : How the business elite and their schools threw our lives out of balance. Zed Books. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usq/detail.action?docID=773745

- Lukes, S. (2021). Power: A radical view (3rd ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Maassen, P., & Stensaker, B. (2019). From organised anarchy to de-coupled bureaucracy: The transformation of university organisation. Higher Education Quarterly from. 73(4), 456–468. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/hequ.12229 https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12229

- Magee, J. C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Social hierarchy: The self‐reinforcing nature of power and status. The Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 351–398. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520802211628

- Mannay, D. (2010). Making the familiar strange: Can visual research methods render the familiar setting more perceptible? Qualitative Research, 10(1), 91–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109348684

- Margetts, F., van der Hoorn, B., & Whitty, S. J. (2023). Playing With Power: Using Collage to Bring Reflexivity to Management Studies. Sage Research Methods: Business. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529624762

- Margetts, F., Whitty, S. J., & van der Hoorn, B. (2023a). A leap of faith: Overcoming doubt to do good when policy is absurd. Journal of Education Policy, 39(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2023.2198488

- Margetts, F., Whitty, S. J., & van der Hoorn, B. (2023b). A leap of faith: Overcoming doubt to do good when policy is absurd. Journal of Education Policy, 1–23. Retrieved August 22, 2023, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/02680939.2023.2198488

- Marginson, S. (2013). The impossibility of capitalist markets in higher education. Journal of Education Policy, 28(3), 353–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.747109

- Marginson, S., & Considine, M. (2000). The enterprise university: Power, governance and reinvention in Australia. Cambridge University Press.

- McCaffery, P. (2018). The higher education manager’s handbook: Effective leadership and management in universities and colleges (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/lib/usq/detail.action?docID=5495412

- Mettler, S. (2016). The policyscape and the challenges of contemporary politics to policy maintenance. Perspectives on Politics, 14(2), 369–390. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592716000074

- Mirvis, P. H. (2014). Mimicry, miserablism, and management education. Journal of Management Inquiry, 23(4), 439–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492614537175

- Morley, L. (2001). Subjected to review: Engendering quality and power in higher education. Journal of Education Policy, 16(5), 465–478. Retrieved February 6, 2022 from https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930110071057

- Morley, L., & Gandin, L. S. A. (2010). Momentum and melancholia - women in higher education internationally. In M. W. Apple & S. J. Ball (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of the sociology of education (pp. 384–395). Routledge.

- Naidoo, R., & Jamieson, I. (2005). Empowering participants or corroding learning? Towards a research agenda on the impact of student consumerism in higher education. Journal of Education Policy, 20(3), 267–281. Retrieved February 6, 2022 from https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930500108585

- Parker, L., Martin-Sardesai, A., & Guthrie, J. (2019). Four decades of neo-liberalism, new public management, and Australian universities: An accountability transformation by stealth. 25th New Public Sector Seminar (NPSS): NPM - the final word, University of Edinburgh, Scotland. Edinburgh, UK: University of Edinburgh.

- Petersen, E. B. (2009). Resistance and enrolment in the enterprise university: An ethno‐drama in three acts, with appended reading. Journal of Education Policy, 24(4), 409–422. Retrieved February 5, 2022 from https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930802669953

- Pollitt, C. (2016). Managerialism redux? Financial Accountability & Management, 32(4), 429–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12094

- Raaper, R. (2016). Academic perceptions of higher education assessment processes in neoliberal academia. Critical Studies in Education, 57(2), 175–190. Retrieved May 3, 2019 from https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2015.1019901

- Rowlands, J. (2013a). Academic boards: Less intellectual and more academic capital in higher education governance? Studies in Higher Education, 38(9), 1274–1289. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.619655

- Rowlands, J. (2013b). The effectiveness of academic boards in university governance. Tertiary Education and Management, 19(4), 338–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2013.822926

- Rowlands, J., & Rowlands, M. (2017). Academic governance in the contemporary university. Springer.

- Sabri, D. (2010). Absence of the academic from higher education policy. Journal of Education Policy, 25(2), 191–205. Retrieved February 5, 2022 from https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930903428648

- Shattock, M. (2005). European universities for entrepreneurship: Their role in the Europe of knowledge the theoretical context. Higher Education Management and Policy, 17(3), 13. Retrieved September 5, 2023, from https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=ac913861-55cf-485e-9dce-d72b74bb61be%40redis.

- Shattock, M., Horvath, A., & Marginson, S. (2019). The governance of British higher education: The impact of governmental, financial and market pressures. Bloomsbury Academic. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=458yEAAAQBAJ

- Shepherd, S. (2018). Managerialism: An ideal type. Studies in Higher Education, 43(9), 1668–1678. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1281239

- Shore, C., & Wright, S. (1999). Audit culture and anthropology: Neo-liberalism in British higher education. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 5(4), 557–575. https://doi.org/10.2307/2661148

- Singh, P., Heimans, S., & Glasswell, K. (2014). Policy enactment, context and performativity: Ontological politics and researching Australian national partnership policies. Journal of Education Policy, 29(6), 826–844. Retrieved 28 October 2021, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/02680939.2014.891763?casa_token=xdFwL47jxOgAAAAA:m3n0P_aTplyou7cKZinQlBdvsDC8chh-ySczNIQxj3CUxjDVDYGsJExZ3A2xLMI1IPc2ahsK1HTuyA

- Skerritt, C., McNamara, G., Quinn, I., O’Hara, J., & Brown, M. (2021). Middle leaders as policy translators: Prime actors in the enactment of policy. Journal of Education Policy, 38(4), 1–19. from. Retrieved December 4, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2021.2006315

- Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. (2021). Higher Education Standards Framework (Threshold Standards). 6.2 Corporate Monitoring and Accountability. https://www.teqsa.gov.au/how-we-regulate/higher-education-standards-framework-2021/hesf-domain-6-governance-and-accountability.

- Trowler, P. (2002). Fige 1.1 the implementation staircase (adapted from Reynolds and Saunders (1987)). Open University Press.

- Våland, M.S., & Georg, S. (2018). Spacing identity: Unfolding social and spatial-material entanglements of identity performance. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 34(2), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2018.04.002

- Walker, S. (2020). Review of the adoption of the model code on freedom of speech and academic freedom. S. a. E. Department of Education. https://www.education.gov.au/download/10391/report-independent-review-adoption-model-code-freedom-speech-and-academic-freedom/16890/report-independent-review-adoption-model-code-freedom-speech-and-academic-freedom/pdf

- Warren, S. (2017). Struggling for visibility in higher education: Caught between neoliberalism ‘out there’ and ‘in here’ – an autoethnographic account. Journal of Education Policy, 32(2), 127–140. Retrieved February 5, 2022 from. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1252062

- Webb, P. T. (2014). Policy problematization. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27(3), 364–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2012.762480

- Wegren, S., & Kinitzer, A. (2007). Prospects for managed democracy in Russia. Europe-Asia Studies, 59(6), 1025–1047. Retrieved September 11, 2023, fromhttps://doi.org/10.1080/09668130701489204

- Wheeldon, A. L., Whitty, S. J., & van der Hoorn, B. (2023a). Centralising professional staff: Is this another instrument of symbolic violence in the managerialised university? Journal of Educational Administration and History, 55(2), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2022.2095993

- Wheeldon, A. L., Whitty, S. J., & van der Hoorn, B. (2023b). Fish‐out‐of‐office: How managerialised university conditions make administrative knowledge inaccessible to academics. Higher Education Quarterly, 77(2), 342–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12404

- Wheeldon, A. L., Whitty, S. J., & van der Hoorn, B. (2023c). Historical role preparedness: A bourdieusian analysis of the differential positions of professional staff and academics in an Australian managerialised university. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/17411432231191173

- Winchester, H. P. M. (2007, 11–13 July 2007. Academic board and the academy: seizing the moment https://www.academia.edu/download/48937346/Investing_in_ones_future_Are_the_costs_20160918-17610-7alswz.pdf#page=169

- Winter, R., Taylor, T., & Sarros, J. (2000). Trouble at mill: Quality of academic worklife issues within a comprehensive Australian university. Studies in Higher Education, 25(3), 279–294. Retrieved February 6, 2021 from https://doi.org/10.1080/713696158

- Wulf, M. (1989). The Struggle for Official Recognition of ‘Displaced’ Group Memories in Post-Soviet Estonia. In M. Kopecek (ed.), Past in the Making: Historical Revisionism in Central Europe after 1989, (pp. 221–246). Budapest, NY: Central European University Press. https://directory.doabooks.org/handle/20.500.12854/55765

Appendix A

– Foucauldian questions posed to the vignettes to assist with collage creation

Statements and Monuments

Does the language and rhetoric employed by actors influence the framing of discussions and policy directions, shaping the discourse within the meetings?

Are there recurring statements or phrases used by actors that reflect and reinforce managerial values, contributing to the formation of specific discursive patterns?

Do the monuments (e.g., policies, decisions, documents) generated within the meeting reflect the influence of specific actors and emphasise managerial values, solidifying their power in the institutional discourse?

Power Relations and Authority

Does the presence of any actor or actors influence the power dynamics within the meeting, shaping the hierarchies and determining who holds the authority to speak, propose ideas, or influence decision-making?

In what way does the institutional authority of a dominant actor impact the distribution of power and authority within the meeting?

Are there instances where an actor’s position of authority is used to shape the discourse and suppress alternative viewpoints, controlling the narrative within the meetings?

Framing of Discussions and Decision-Making Processes

Does an actor influence or shape the framing of discussions within the meeting, shaping the formation of knowledge and discursive practices?

Are certain topics or perspectives prioritised or marginalised based on an actor’s influence, and does this reflect the power dynamics at play?

In what ways does an actor advocating for their own will and/or managerial values impact the decision-making processes, and how does this shape the overall discourse?

Control of Discourse and Receptivity

Do specific actors control the flow of discourse within the meetings, employing mechanisms or practices to limit what can be said or discussed?

Are dissenting voices or alternative perspectives suppressed or discouraged in the meetings, shaping the overall receptivity to diverse viewpoints?

Do other members of the meetings respond to the directions of a dominant actor, and what factors contribute to their apparent receptivity or resistance to those directions?