ABSTRACT

Despite a vast body of research on inclusive education, students’ perspectives and experiences of inclusive secondary schools have garnered little attention. Yet their perspectives and experiences are central to the development of inclusive schools. To investigate this, we conducted seven group discussions with ninth-year students at German inclusive secondary schools, asking them what makes a school a place where all students can learn well. Using reflexive thematic analysis, we developed three themes (community, justice, and school as a place to live), three cross-thematic areas (limits, teachers, and belonging), and two overarching central discourses (othering and submission to a meritocratic, non-participative school logic). In light of our findings, we argue that inclusive secondary schools still face major challenges vis-a-vis the continuing non-inclusiveness of societies and that students’ views can provide valuable insights into key success factors for inclusive secondary education.

1. Introduction

In the more than 10 years since the ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations Citation2006) and the 25 plus years since the Salamanca Statement, a vast body of academic literature on inclusive education (IE) has grown (Hernández-Torrano et al. Citation2020). Despite the well-established legal right to IE, the debate on what actually constitutes IE remains unresolved. This makes it necessary to continually clarify what we as researchers mean by ‘inclusive education’ (Göransson and Nilholm Citation2014). Underpinning this paper is a ‘broad’ understanding of inclusive education (Thomas Citation2013), which ‘involves a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers with a vision serving to provide all students of the relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience and environment that best corresponds to their requirements and preferences’ (UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Citation2016; emphasis by the authors). Given this right of all students to attend a regular classroom in a suitable non-segregated mainstream school, we understand IE as a transformative movement and ‘call to action’ (Slee Citation2019, 911) that challenges mainstream schools to cater to diverse learners (DeVroey et al. Citation2016). This is especially true for students from poor, migrant and/disabled backgrounds which mainstream schools have historically failed (Ainscow Citation2007; Lindmeier and Lütje-Klose Citation2015; UNESCO Citation2008). Taking this broad understanding of IE as a starting point, we find that most of the existing studies on IE: (a) focus on the views of adults (Hernández-Torrano et al. Citation2020); (b) focus on particular groups of students (Messiou Citation2017); (c) are centred on primary schools as setting (De Vroey et al. Citation2016); and (d) focus on attitudes towards IE (Hernández-Torrano et al. Citation2020; Van Mieghem et al. Citation2020).

1.1. What about the experience of students in inclusive schools?

IE requires an ‘understanding [of] the experiences of education from the perspectives of those who directly encounter it, which in the case of schooling, means children and young people’ (Messiou and Hope Citation2015, 1009). Simply asking adults about children’s views is no substitute for the input of children themselves (Greig et al. Citation2012). Thankfully, recent studies have increasingly focused on the students’ voice (Cook-Sather Citation2018). In IE research, student-centred research is often limited in their scope on particular groups of students (Messiou Citation2017), concentrating for example on typically-developing students (e.g. Bates et al. Citation2015) or disabled students (e.g. Broer et al. Citation2005; Connor and Cavendish Citation2020; Humphrey and Lewis Citation2008) in inclusive contexts. Clearly, this is important research but it does not address the experience of all students there. However, if the idea of inclusive schools as ‘schools for all’ is to be taken seriously, IE research must expand its research scope to reflect the reality of inclusive schooling and move beyond the simplistic binary of dis/abled. Selecting certain students as research participants merely because they belong to an ascribed category risks (a) making unjustified assumptions about their experience of schooling and (b) excluding students that may also face marginalisation (Messiou Citation2017).

IE in secondary schools – especially in the highly stratified, competitive German school system (Powell Citation2011) from which this research stems, faces particular challenges. Structurally, secondary schools are asked to marry ‘equity and excellence’ (De Vroey et al. Citation2016, 111). Since secondary education has been slow to implement inclusive practices compared to primary education, currently there are relatively few studies on inclusive education at the secondary level (De Vroey et al. Citation2016; Pearce et al. Citation2010).

1.2. Experiences, not attitudes

While a few landmark studies have asked students, what constitutes a ‘good’ (secondary) school (e. g. Burke and Grosvenor Citation2005; Lahelma Citation2002), this question is yet to be addressed for inclusive secondary schools. With a predominant focus on attitudinal research (Hernández-Torrano et al. Citation2020; Van Mieghem et al. Citation2020), the existing scholarship on IE in secondary contexts does little to further our understanding of students’ overall experience. The question thus arises: How do students at inclusive secondary schools experience school? Over the past three decades, a handful of studies addressing specific aspects of the student experience focus on two main themes.

A first group of studies addresses how students in inclusive classrooms describe ‘good’ instruction. Sub-themes here relate to fair assessment practices (e. g. Gabryszczak Citation2015; Klingner and Vaughn Citation1999), the different learning speeds of students in the same classroom and their effect on academically strong students (e. g. Dare and Nowicki Citation2018; Hüls and Schneider Citation2015; Klingner and Vaughn Citation1999), the qualities seen by students as essential to teachers of inclusive secondary education (e. g. Cefai and Cooper Citation2010; Connor and Cavendish Citation2020), and how the bustling inclusive secondary environment can serve as a learning barrier for students with specific needs (e.g. Humphrey and Lewis Citation2008). A second group of studies has mainly explored the student perceptions of disabled pupils’ social exclusion in inclusive classrooms (e. g. Bates et al. Citation2015; Buchner Citation2018; Cefai and Cooper Citation2010; Hüls and Schneider Citation2015) and the social support systems that can foster social inclusion (e. g. O’Rourke and Houghton Citation2008).

We were motivated to conduct this study by the dearth of research on inclusive secondary education in general, and on students’ own perceptions (Rose and Shevlin Citation2017, 67) of their experience of inclusive schooling in particular. Following Dyson and Millward’s (Citation2000) ‘organizational paradigm’ (Ainscow Citation2007), our inquiry focusses on institutional conditions that enable learning and participation by all students – instead of investigating individual characteristics of students that enable or hinder it. We thus wanted to know what students at inclusive schools think is necessary to support the effective participation of all students. One caveat here is that extant research shows that students who are asked about their views on IE, often have no concept of IE as educational policy (e.g. in the UK, see Bates et al. Citation2015) – a finding our research also confirmed. This necessitates a slight shift of question: For students at inclusive secondary schools, what makes a good school where all students can learn well?

2. Methods

2.1. Methodological framework

In this paper, we ask what students at inclusive secondary schools – as an under-researched key stake holder group – think makes a school where every student can learn well. To investigate this question, we employed a qualitative methods framework as this (a) is especially helpful to elucidate the perspectives of under-researched groups and research areas and (b) it allows insight into the meaning making processes of students and how, in turn, they draw on relevant social discourses to do so. Our data generation method of choice, group discussions, allow participants to express themselves more freely and among peers compared to other forms of qualitative enquiry, e. g. in interviews. Reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2022) was then applied as analytic procedure that allows recognising patterns of meaning running through the material.

2.2. Participants

To investigate this question, in the spring of 2019 we conducted a total of seven group discussions with 41 ninth-year students (aged 14-17) from four secondary schools (cf. ). Scattered across one state in eastern Germany, the schools were selected based on their previous application for the ‘Jakob Muth Prize for Inclusive Schools’ (awarded by the German UNESCO Commission, the Bertelsmann Foundation and the Federal Government Commissioner for Matters relating to Persons with Disabilities). This selection criterion helped us answer the tricky methodological problem of defining what exactly an ‘inclusive school’ is in the German context – for that legally, all mainstream schools are deemed ‘inclusive’ given that every student has the legal right to attend a mainstream school (Biermann Citation2022; Niemeyer Citation2014). Which, how and to what extend a specific mainstream school actually has inclusive cultures, structures and practices in place is not clear unless one conducts extensive preliminary research at each school one wants to later interview students at. Schools that apply for such an award and describe themselves as inclusive, we assumed, will have inclusive concepts and objectives that shape the structures and actions of stakeholders, thus creating a more inclusive school culture.

Table 1. Participants by school type and gender.

As a federal republic, Germany consists of 16 federal states (Bundesländer). Education is devolved to the states meaning each state has its own system of organising public education within the boundaries set by the German constitution. The highly ability-stratified German secondary school system presents a major challenge to the implementation of inclusive education as education for all (Powell Citation2011; Powell, Edelstein and Blanck Citation2016). Apart from a separate special education system still providing segregated education for the majority of students labelled as having ‘special educational needs’ (Kultusministerkonferenz Citation2020; for a comprehensive analysis of the German special education system see Powell Citation2015), two basic types of secondary schools can be distinguished in Germany broadly and in the state this research was conducted at: (1) selective secondary schools award school certificates allowing university entrance by studying up to year 12/13 (Abitur, comparable to ‘A levels’ in British terminology). They recruit their students based on their primary level grades. (2) In non-selective secondary schools, the achievable secondary education degrees allow students admittance to apprenticeships programmes but not university education. While today nearly 50% of a given cohort leave secondary education with A-level equivalent certificates (BMBF Citation2021), the ability-stratification of the German secondary education system has meant a de facto delegation of the implementation of inclusive education to secondary schools not awarding A-level-equivalents (Rabenstein, Stubbe and Horn Citation2020). It was thus crucial that our sample included students from all mainstream school types – without sampling from special schools.

All the schools included in the sample implemented inclusive education as students with mixed-abilities learning in the same classroom and formally belonging to the same class group. An important exception in this regard was the school at which group discussion (GD) 2 and 3 where conducted: while the school also generally implemented mixed-ability classrooms, for this year 9 cohort, the school had created a separate special education class that shared some but not all of the general education classes.

As required per state legislation, parents’ consent was sought for all participants. Students were selected from each class group for the group discussions based on (a) filled-in parental consent forms (b) the students’ willingness and interest in taking part in a group discussion that day and (c) the class group leader’s recommendation for students to talk to after we told them that we wanted to talk to a heterogenous group of students.

Of the total 41 students, 61 percent of the participants were male, and 39 percent were female; 25 percent considered themselves to be disabled, and 10 percent declared a migration background. Students transition to secondary schools in seventh grade in the federal state where the schools were located. We chose to talk to ninth graders because (a) students at that grade level have at least two years’ experience of IE, even if they attended a non-inclusive primary school (maximizing exposure to IE) and (b) few of them leave school before ninth-grade, since all German students must attend school for at least nine years (minimizing the likelihood of excluding students with low school attainment from the sample, who may leave school after the mandatory schooling period). In every school sampled, the student groups were each drawn from a single class group, ensuring that students in each group knew each other already. All of the students participated voluntarily and received no incentive or reward in exchange for their participation. Ethics approval was granted by the state’s Ministry of Education (WU 76-E-2018).

2.3. Generating data: group discussions

Group discussions are an ideal way to gain insight into the views, perspectives, and ideas of young people, as they can create a safe-space for expressing one’s opinions and help to reduce the power imbalances between researchers and participants (Adler, Salanterä, and Zumstein-Shaha Citation2019). Furthermore, we associate the term group discussion with the possibility of exploring the knowledge and meaning-making processes within the group (Bohnsack and Przyborsky Citation2007; Przyborsky and Riegler Citation2010). Each discussion was audio-recorded for later transcription and began with an informed consent procedure. Given our interest in the students’ views on what makes a good school, we always opened our discussions with the same question: What makes a good school where every young person can learn well? Following a loose interview schedule, students were then asked (a) what needed to be in place for equitable learning in school, (b) whether their school allowed all students to learn well and if not, what barriers they saw in that regard, (c) what a school needs in order to enable equitable learning of (dis/)abled young people / students from non-German speaking families / families from low socioeconomic backgrounds and (d) what ‘inclusive education’ or ‘integrative education’Footnote1 meant to them. Each discussion was conducted at the students’ school and lasted between 45 and 120 min. To analyse our data, we used Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2013) reflexive thematic analysis. In contrast to other content analysis procedures that aim on the reduction of the data, reflexives thematic analysis focusses on the construction of themes. These are understood as recurring patterns of meanings relating to the research question across the whole material: ‘Pattern-based analysis rests on the presumption that ideas which recur across a dataset capture something psychologically or socially meaningful’ (Braun and Clarke, Citation2013, 223). Reflexive thematic analysis involves six steps: 1. transcribing the verbal data, 2. generating initial codes, 3. generating initial themes, 4. developing and reviewing themes, 5. refining, defining and naming themes, and 6. writing the report (Braun and Clark, Citation2022). First, during the review of the individual transcripts of the group discussions, significant topics were named, discussed amongst the authors and transferred into initial codes. These codes were then used to examine all the material using MAXQDA. The codes were then reviewed and suggestions for meaningful themes were developed. Taking into account the explicit (semantic) as well as implicit (latent) level of meaning, three cross-code themes were constructed, which represent recurring patterns of meaning (Braun and Clarke, Citation2022).

3. A place of belonging, justice, and wellbeing – an inclusive school from the students’ point of view

Conducting group discussions, we investigated what students at German inclusive secondary schools said makes a good school where all students can learn well. Using reflexive thematic analysis, we developed three themes including multiple sub-themes. We will unfold this interpretation of the data in the following section, anchoring themes by way of direct quotes from the group discussions.

3.1. Theme A: finding belonging in a community with (no) limits

In our group discussions, students framed being part of a school-community as a prerequisite to learning and to their own sense of belonging. In two sub-themes, we tried to capture opposing aspects: First, belonging to a school community creates a sense that one is ‘normal’. Second, the school community itself sets limits on normalcy that not everyone can overcome.

3.1.1. A1: a sense of community as precondition for belonging, learning and ‘feeling normal’

Students identified the class group as key for their sense of community and belonging at school. As the place where they spend most of their time at school, the class group was described as an important arena for finding, forging and maintaining friendships:

And I can also learn quite well here at school and I also like being here, simply because I have my friends, I know I can also come here, I can talk to people, I simply always have someone around me and I don't get any stupid ideas now. (GD5_A204Footnote2)

But I think it's also quite good for some individuals, when people who maybe don't have the best standing, that they then [when students from different class groups come together] maybe flourish a little bit anew. Personally, I think it's a good way to meet new people and make new friends. (GD4_A65)

Students distinguished between feeling a sense of social belonging and having a good working relationship with each other. While they described working together with friends as more conducive to learning, they also acknowledged the importance of working together with others:

Well, there was also a girl in our class who was a bit in conflict [with other students]. I wouldn’t have had anything do with her outside of school, I’ll be honest, but I did group work with her at school and got along with her and I think that’s actually important in a class, in a community, that you rise above it a bit, even if you’ve been arguing with the other person, but then you’re assigned to group work, that it still doesn’t escalate into a fight and you have to work by yourself because of that. (GD5_A205)

Finally, the students seemed to identify with an overall school ethos which aims to create a community of belonging, where differences between students fade to the background:

Maybe that at our school it is so important that all humans are equal. Whether they have a disability, some weakness, some illness, whatever, that they are just as (.) valuable or just as valued as we are as normal people. But they are also normal, right? (GD1_A122)

3.1.2. A2: the limits of community – ‘the others’ belong here, but are not part of ‘us’

When asked about integrative and inclusive education, it struck us that none of the students seemed to regard inclusive education as a meaningful term – even though the term is well established in popular discourse (Althoff Citation2021; Lüte et al. Citation2014), schools and educational policy in Germany (Hinz Citation2017). Instead, the schools they described seemed to be places where every student was formally welcome as part of the school (see A1), but where some groups of students were construed as not belonging to ‘us’: ‘So, we throw something in that doesn't belong and try to make it belong.’ (GD3_A808)

Here, IE is largely understood as them adapting to us, based on an implicit distinction between ‘normal’ and ‘not-so-normal’ pupils. In this quote – speaking very distanced and yet in everyday language – the objectified ‘they’ is understood to be a task for ‘us’: ‘we’ have to make ‘them’ fit within the existing system. In constructing this ‘other’, the students spoke about different groups of pupils: (1) disabled children, (2) ‘problem children’ who fail to conform to (un-) official behavioural rules (confounded with children from poor families or children living with youth services), and (3) non-German speaking students. Thus, ‘us’ usually implied non-disabled, rule-following, German-speaking students:

Interviewer: And why do you think that is? That your classmates have learned German so well and have arrived here so well. Do you have any ideas?

Boy1: Because they were really integrated, I thought. So, that they were properly accepted and that they got help. The support workers were there for him in the first year and when he was able to speak relatively well, he was on his own. But he gets a lot of help.

Boy2: Yes, I also think that we are very open. We are very open as students, that is whether we know him or not, we still approach him and try to be kind somehow. Try to include him. (GD1_A254-257)

3.1.3. Conclusion theme A

When thinking about how the students talked about the kind(s) of belonging a good inclusive school offers, we were struck by the ambivalence of their comments. Like two sides of a coin, two themes emerged that speak to, yet trouble ideas of schools aiming to be inclusive as offering communities of belonging. On the one hand, the students stressed that at their schools, generally all students – whatever their background – had a place, thus enabling formal belonging for all (cf. Slee Citation2019; Vandenbussche and De Schauwer Citation2018). On the other hand, the language used by students in talking about these issues reflected binary us-versus-them thinking. This logic implicitly separates those who have a legitimate place in the school community from those who must earn this place through a process of assimilation (cf. Baak Citation2019 for an Australian example of the same dynamic; Slee Citation2001). During that process, newcomers must adapt to the dominant ideologies of the ‘normal pupil’ (Baglieri et al. Citation2011; Ratner Citation2016), albeit with the support of ‘normal’ students and teachers alike (cf. Van Mieghem et al. Citation2020, 683).

3.2. Theme B: justice for all – but especially for me

When talking about ‘a school where everyone can learn well’, the students frequently brought up issues of justice and fairness as basic principles of an equitable school. This theme mainly emerged from references to situations in everyday school life which they considered to be unfair. Here, justice was not construed as a universal norm of human coexistence or as something to which everyone at the school was entitled, but as a specific right of students. For both assessment situations and teaching practices, the students described their experience in terms of a tension between universal standards of fairness and individual, needs-based standards of justice. From this, we developed the sub-themes Justice and performance (B1) and Teachers as ‘guardians of justice’ (B2) connected to a third sub-theme: Justice versus equality (B3).

3.2.1. B1: justice and performance

In our data, the students’ idea of justice was closely connected to a performance-oriented notion of learning and rule-following. They described appropriate student behaviour –being attentive during class, doing one’s homework, preparing for tests – as a necessary prerequisite for good marks:

If nobody sits down and studies, then it's not anyone's fault. It's not the teachers’ fault that the grades are like that, it's just the student's own fault because they don't [participate] in class and they don't study at home. (GD2_A104)

Justice also meant the necessity for setting, following, and strictly enforcing clear rules at school: ‘I think it's good that there are rules. Of course, they are sometimes broken, but I also think it's important that there is a firm hand.’ (GD4_A129)

Students seemed to understand school rules not as a framework fundamental to the school’s functioning as an institution or to create a positive learning environment. Rather, they framed (school) rules as a standard in its own right. Rule-following as a behaviour, in this view, can and should be evaluated using the same individualising competitive logic students are familiar with from questions of school achievement. Those who follow the rules win this ‘competition’ – but only if the rule-breakers are punished. If rule breaking remains unpunished, students think it is unfair to all those who comply.

3.2.2. B2: teachers as ‘guardians of justice’

From the students’ point of view, justice and its enforcement are above all the domain of teachers, who, as a kind of ‘guardians of justice’, are required to always act fairly and according to their own standards:

That the teachers don't favour anyone. Or, in general, [it’s bad when] someone is favoured, because I think it's always pretty mean, or others think it's pretty nasty when you just know, ah yes, that they're the teacher's favourite anyway, they will be picked to answer the question or chosen anyway. (GD1_A212)

Furthermore, the students felt that teachers should hold themselves to the very standards they teach:

Student A: Or when we are debating something, she [the teacher] tells us we are arguing. Even though that's what she taught us to do. Student B: Yes, she herself taught us in German class that if we have an opinion, we should substantiate it. When we do that [she says]: ‘stop arguing’. (GD3_A525)

3.2.3. B3: justice vs. equality

When discussing performance-oriented justice and teacher fairness, students grapple with the fact that justice and equality are not necessarily identical. To resolve this dilemma, they either (a) distinguish their group from another which is perceived as receiving preferential treatment, then framing the other group as unfairly privileged or (b) frame different standards of assessment for the same task as unfair, yet – paradoxically – support individualised assessment-standards for their own performance.

Demanding ability-based justice for oneself frequently requires that one distinguishes oneself from other student groups with regard to race, disability or gender (cf. theme A2):

And I also have the feeling that people like that are not properly dealt with. For example, he's always late and has no manners and then they just say and don't crack down on him, but with a German student, for example, with us, if he is late or something, then they do crack down on him. (GD5_575)

Some participants defended the idea of equal rights for students with learning difficulties, arguing that achievement should be assessed based on each student’s aptitude, rather than a universal standard defined for a fictitious ‘average’ student. Others, however, described their experience very differently:

We normal students, I'll just say it, have to fight to get into tenth grade, so that we can make it to tenth grade. Or ninth. And the students with learning disabilities still keep going forward. Despite those grades. Ok they get a different degree, but still, that's unfair to us. I find it unfair in general. I have to fight to get into tenth, the students with learning disabilities don't. They can get sixes, fives [ = E or F; comment by the authors]. They still get ahead. (GD2_A153)

3.2.4. Conclusion theme B

The students’ perceptions of various aspects of justice reflects not only the issue’s central role in school, but also the fact that justice in general is characterized by a tension between equalising and differentiating principles (Flitner Citation1985). Neither schools nor teachers can escape this tension between egalitarian and needs-based distributive justice, i. e. offering everybody the same opportunities and at same time giving everyone what they need according to their abilities and circumstances (Flitner Citation1985). However, IE can be characterised as fundamentally principled on needs-based justice (Kobs, Knigge and Kliegel Citation2021). The incompatibility of individual adaptation and standardized educational goals reflects this dilemma (Speck Citation2019). For Prengel (Citation2012), this is a central paradox of IE itself, because differentiated learning objectives can bar some students’ access to qualifications, thereby putting educational justice at risk: SEN students may reach their final year thanks to adapted curricula and individualised support but, for example, then fail to pass standardised final examinations.

Against this backdrop, the students’ ambivalent struggle for justice appears hardly surprising: Students framed needs-based justice as crucial for their own learning at school. When individualised rules, standards or support are targeted at other students, however, they position this needs-based differential treatment as unjustified given that it violates the principles of egalitarian justice. This is highly problematic for IE given that we know that experiencing school as just has a positive impact on a student’s sense of belonging, stress levels, success in school, and social behaviour (Dalbert Citation2013) – while at the same time equal access to participation opportunities and thus teachers being responsive to students’ individual needs can be seen as a central criterion for school quality (Reich Citation2008). A high degree of transparency as to which principles of justice are applied to whom, when and why, and an open discussion about them among all students could help to avoid irritation and increase a sense of injustice – as well as making these principles themselves the subject of joint discussion.

3.3. Theme C: school as place for living and learning

This theme looks at the features of school as a place where teenagers spend significant amounts of their time. Here, two topics stand out in our data, that point to significant impact factors for student wellbeing: (1) the school as built environment and (2) teachers’ personality, behaviour and actions.

3.3.1. C1: OUR school building? (No) space(s) for us

In terms of school as a built environment, the students describe a good school as one that serves all students by offering them general cleanliness, functioning basic facilities (like toilets), spacious, friendly and well-lit rooms with adaptable furniture and comfortable chairs, and a variety of locations for breaks and eating. In describing these features, students implicitly point to the fact that they are human beings, not just pupils:

I don't like the chairs here at all, for example, because I can't sit there at all, because I always get back pain. So, a certain level of cosiness, so that you don't have to squeeze in there, that's actually quite pleasant. So that you feel comfortable in the place of learning. (GD4_A117)

The worst thing in the gyms are always the bathrooms, no one wants to go to the toilet there, because it's really dirty. (GD6_A156)

Students framed the experiences brought on by a shortage of space – feeling cramped, lacking sufficient space during breaks, or having to rush to get a seat to eat lunch – as stressful and detrimental to their wellbeing. The students saw school as a complex environment that must serve a range of student needs not met by merely enlarging existing common areas. Rather, they wanted schools to provide various specific spaces for specific needs, e.g. bright classrooms, a cafeteria with a sufficient number of seats, places to hang out with their peers or informal areas to use computers/the internet – spaces that would also give students a sense of ownership of their own school. In comparison to this vision of a desirable school environment, students often considered their schools to be inadequate – for example, in terms of accessibility:

We have a wheelchair ramp downstairs, […] but if there are lessons on the second floor, how is the child supposed to get up there in a wheelchair? That's just – really the elevator would be a good thing, but it is about money. (GD6_A570)

3.3.2. C2: teachers who care

For the students, the ideal teacher appears to be fundamentally an attachment figure who shows genuine interest in their students, behaves and communicates in a nice and student-focused way, and uses these qualities to create an atmosphere of wellbeing and support for students. Instead of being ‘robots […] [who] just want to get done with their content of the curriculum, [and] don’t even smile.’ (GD7_A650 - 652), good teachers are construed as affable, authentic people, who can see eye- to-eye with students and are interested in building real relationships with them:

I think it's also very important that the teachers respond to the students and cover their fields of interest and […] when they are able to learn well in a certain working atmosphere, the teachers should continue to provide that atmosphere. (GD4_39)

3.3.3. Conclusion theme C

From the students’ point of view, school has to be understood as a place of learning and living. Students stressed that the school environment, and the teacher’s ability to create a comfortable learning atmosphere at school, affected their wellbeing at school. Like others have shown, how teachers interact and engage with students clearly impacts their achievement (Connor and Cavendish Citation2020; Powell et al. Citation2018). Structural conditions that are clean and appealing are equally important to the creation of a positive, effective learning environment in school (Ramelow and Gugglberger Citation2014). Furthermore, student wellbeing can be seen as a basic indicator of school inclusiveness (Külker et al. Citation2017). However, it seems that the students we talked to must adapt to non-inclusive school conditions, while their schools (cl)aim for inclusiveness.

4. The ethos of inclusive education and its tensions

4.1. Cross-thematic areas: teachers, limits, and belonging

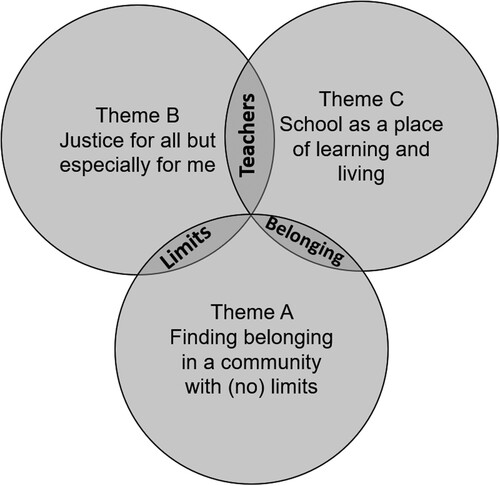

In comparing the three themes developed from our data, we noticed three cross-thematic areas – teachers, limits, and belonging ():

Experiencing community in school (theme A) and the students’ sense of justice (theme B) were interconnected in being construed as limited as opposed to limitless. While our participants described the school community as one that secured the formal belonging of all students, their comments also revealed limits to their social acceptance of differences in ability or race. Time and again, the school community emerged as splintered into sub-communities. The same ambivalent fault lines fractured the students’ construction of fairness. Here, needs-based distributive justice was framed as desirable for oneself, but as unfairly privileging when applied to other groups. This resonates with the well-established finding that ableist and racist exclusionary practices persist in contexts that claim inclusivity (e. g. Bates et al. Citation2015; Berryman and Eley Citation2019; Cefai and Cooper Citation2010; Humphrey and Lewis Citation2008) and point to IE being an ongoing transformative process that promotes belonging (Slee Citation2019) while working hard to reduce exclusion.

Teachers played a central role at the intersection between schools as places to live (theme C) and students’ sense of fairness (theme B). Like a thread running through our data, the students construed teachers as responsible and able to (a) enact teaching practices that would ensure fairness in all areas of school and (b) implement student-friendly interaction patterns and c) create the right spatial conditions to ensure student wellbeing. Thus, teachers are seen as moral leaders offering authentic relationships, not as mere instructors. This jells with quantitative studies showing the significance of teachers for good schools in general (Hattie Citation2008) and for good IE in particular (e. g. Schwinger et al. Citation2020 for inclusive primary education). It also connects with students’ perspectives on the ideal characteristics of inclusive teachers (e. g. Connor and Cavendish Citation2020; Klingner and Vaughn Citation1999) and their role in ensuring fairness (e. g. Gorard Citation2012).

Belonging emerged as key to understanding the intersection between the themes of experiencing school as a community (theme A) and school as a place to live (theme C). In our data, a sense of belonging arose on the one hand from a sense of community and was crucial for learning and relates to notions ‘being normal’. On the other hand, belonging is lacking where school – its processes as well as its structural conditions – is not adapted to the needs of the students (cf. Vandenbussche and De Schauwer Citation2018). The need to feel like you belong is a fundamental human motive (Deci and Ryan Citation2000; Leary and Baumeister Citation1995) and points back to the fact that school is not (only) a place of education, but also an arena of socialization and psycho-social development where friendships, belonging and being recognized as a member of a community are crucial (Fend Citation2005). A sense of beloning is also strongly connected to student’s wellbeing (Roffey Citation2013). Given the continuing exclusion in wider society, achieving belonging in the context of IE is essential, but challenging (Slee Citation2019).

4.2. Overarching discourses: othering and submission to a meritocratic, non-participative logic of schooling

Abstracting a bit further, we observed two dominant discourses running through our analysis: Othering and submission to a meritocratic, non-participative logic of school.

4.2.1. Othering

In our analysis, we were struck by a recurring undercurrent of othering, which was most prominent in the students’ construal of community and justice. Theoretically, othering can be understood through social-dominance theory as a mechanism that creates and upholds hierarchical relations between social groups (in school) based on psychological, institutional and societal factors (Sidanius and Pratto Citation2012). In talking about equitable schools, the students we spoke to differentiate certain groups of students from themselves in order to protect their own sense of normalcy (cf. Boxall Citation2016; Brehme Citation2017). Normalcy is a highly fraught and dangerous concept as it defines the only legitimate way of existing (Titchkosky and Michalko Citation2009). In modern western school systems like the German education system, normalcy plays a key role until today (Buchner and Kremsner Citation2019; Hacking Citation2009) enabling the management of human variation in the student population through standardisation (Kelle and Mierendorff Citation2013) by teaching to the fiction that is the ‘normal student’ (Annamma et al. Citation2013; Baglieri et al. Citation2011). Schools (re-)produce social inequality based on the notion of ab/normalcy: students who are construed as too far away from the ‘average student’ face deficit-based labels, stigma and finally, segregation in ‘special schools’ as legitimised forms of marginalisation and exclusion. Categories such as ‘special educational needs’ produce life-long disadvantage for those stigmatised by it (Pfahl and Powell Citation2011). IE scholars of various persuasions have argued against normalcy: At the more moderate end, some argue for the critical questioning of notions of normalcy that educational policy, education systems, schools and teachers are reproducing (e. g. Hirschberg and Köbsell Citation2021; Ratner Citation2016). Others have powerfully argued for the rejection of any notion of normalcy in the context of inclusive education (e.g. Köbsell Citation2012; Mallett, Ogden, and Slater Citation2016) in favour of transnormalistic understandings of learning (Lingenauber Citation2013; Schildmann Citation2019) that understand human variation as an unshakable starting point rather than a problem to be solved (cf. Davis Citation2014). Yet, normalcy also bears protective potential: all those who can claim normalcy can find protection from the ‘penalties of difference’ (Boxall Citation2016, 277), e. g. economic or social disadvantage and discrimination. Normalcy can be a powerful tool demand adequate support, rights and anti-discrimination measures that enable those facing discrimination to fully participate in their school like those construed to be ‘normal’ (Boger Citation2015).

We read the students’ ambivalent talk about ‘others’ as an attempt to navigate this tension between more equitable ways of speaking about a heterogeneous student body while maintaining the exclusionary boundaries of normalcy (Hall and Link Citation2004). In following the well-trodden paths of ability and race, manifestations of ‘ableist normativity’ (Campbell Citation2009, 1; see also Wolbring Citation2008) shine through that serve as a legitimising hierarchy-enhancing myth: ways of thinking, speaking and acting that promote or ‘justify the establishment and maintenance of group-based social inequality’ (Sidanius and Pratto Citation2012: 419). These ableist undercurrents can also be witnessed in the continuing primacy of meritocratic understandings of student achievement in inclusive schools found by us and others (e.g. Merl Citation2021). Like an empirical thorn in the theoretical flesh of IE, the patterns of othering running through our data are at odds with (broad) understandings of IE as schools that strive to be less exclusionary (Ainscow Citation2007; Thomas Citation2013) – for that othering serves to uphold this very exclusionary logic. What remains surprising to us, at the end of all this, is that for the students we talked to, formal belonging of each and every student to the school community appeared nevertheless to be uncontested, and incontestable.

4.2.2. Submission to a meritocratic, non-participative logic of schooling

Across all themes and cross-thematic areas, students’ perspectives on school seemed to be undergirded by a traditional logic of school. This logic a) is based on the meritocratic principles of individualised effort, achievement, and efficiency to which the students continually refer and b) implicitly views students as subordinate to teaching staff – a position from which they cannot or should not participate meaningfully in the running of school (e. g. have a say in the organisation of school), let alone emancipate themselves (e. g., contesting and changing the hierarchies at play in school to shape a school that meets their needs). In our group discussions, the students’ subordinate standing vis-a-vis the teachers might explain that students were often complaining about or making demands on schools, and especially teachers (at least in part, though, our main interview question, which asked students to think about how an inclusive school should be may have contributed to this focus). Thus, students retreat to a passive and ultimately defensive position, from which their own potential contributions and participation remain invisible. On the one hand, this stance may reflect the students’ apparent lack of experience in shaping their school in a democratic and participatory way for that students’ perspectives are grounded in their experiences of school (Buchner Citation2018): Being active co-creators of school seems to be unthinkable for the students we spoke to. On the other hand, this passive position also seems comfortable: it frees them from responsibility (e. g. for creating or maintaining school as a place to live) and allows them to focus on ‘surviving’ school. Although understandable, this is ultimately against their own interests in making school a place of learning and living that is focused on the needs of learners (Holzkamp Citation1995, Citation2013). Participation for all – taking the needs and interests of all students seriously based on democratic principles – remains a blank space at the inclusive schools we surveyed, standing in sharp contrast to the idea of IE as participatory education (Cummings, Dyson and Millward Citation2003; Danforth and Naraian Citation2015; Portelli and Koneey Citation2018). Although fostering student participation in school might be structurally difficult (Jones and Bubb Citation2020), our data points to its great significance for students’ sense of belonging, justice and wellbeing.

4.3. Researching student voice on inclusive education: limitations and further research avenues

While we believe our paper can offer valuable insights into students’ perspectives on secondary schools that strive to be inclusive in the German context, the underlying theoretical and methodological framework necessarily implies certain limitation and point at fruitful avenues for further research. We purposefully conducted group discussions without the reliance on recruiting students based on a label or (ascribed) membership to a collective identity (cf. Messiou Citation2017). To offer a more nuanced analysis, future IE research could investigate and contrast the perspectives of students from various backgrounds, e.g. those labelled as having ‘special educational needs’, students facing economic hardship or students with a history of (forced) migration. Such research would ideally employ an intersectional lens (Bešić Citation2020; Liasidou Citation2012) which has the power to elucidate how the multifaceted nature of student identity (e. g. being a disabled young man or a young woman from a poor family) shapes their perspectives on inclusive education. Regarding the generation of data, while the students we spoke to talked about their schools as places to live, further research employing a more open question about students’ overall school experience may provide a more holistic picture, for example by shedding more light on the role of friends and peers for inclusive education. Finally, ethnographic enquiries into the student’s lives at inclusive secondary schools could further our understanding of the situated function and role in everyday school life of the themes developed in this paper. Participant observation would thus allow following the themes generated here and investigate questions such as what is the functioning of the undercurrent of othering in student talk about IE or how are the students claiming school as their space?

5. Conclusion

From the students’ point of view, inclusive secondary schools (or those who describe themselves as such) face the same challenges as other schools. In addition to providing knowledge that leads to good performance and school-leaving certificates, they must also take into account students’ needs for community, justice and school wellbeing. This may be more challenging at inclusive schools because of their heterogeneous student body and its diverse needs. Nevertheless, our data point to the same obstacles that have been always present in schools: a dilemma between equal treatment and responsive support, high pressure to adapt for all students, and a lack of student participation. Furthermore, traditional ingroup vs. outgroup processes persist, and are often performed along well-trodden categories of social exclusion.

As students of secondary schools describing themselves as inclusive, the participants in our group discussions explicitly asserted that all students are entitled to a place in their (school) community. At the same time, they described exclusionary practices based on a broadened but not abandoned understanding of normalcy. Pessimistically interpreted, students in inclusive secondary schools simply learn to ‘talk the talk’, that is, to discuss human difference in socially-desirable ways. Instead, we take the more optimistic view that this ambivalence points to an ongoing shift in the way students think about what it means to be human that may ultimately lead students to reject notions of normalcy altogether. Our analysis shows the potential of listening to students’ experiences when investigating the reality of IE and the challenges it faces. The students pointed us towards the significance of belonging, community, fairness and participation as key success factors for inclusive schools – which, in turn, all can only be achieved with the active involvement of students.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful for the in-depth comments and helpful suggestions of the two anonymous reviewers and to Laura Cunniff and Lene Geißler for their assistance with the copy editing of this manuscript. We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt- Universität zu Berlin.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrea Kleeberg-Niepage

Andrea Kleeberg-Niepage is a psychologist and professor for developmental and educational psychology at Europa Universität Flensburg. She is interested in children's and young people’s perspectives on their life-world and their processes of self- and identity construction, as well as the significance of the social and cultural context for understanding childhood and human development. Current research projects focus on young people’s perspectives on inclusive education, children’s and young people’s use of digital media, and the significance of mobile online dating for the life and relationship formation of young adults.

David Brehme

David Brehme is a psychologist and ethnographer currently working as a doctoral researcher at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. He is interested in how normalcy is constructed and inclusive education from the students’ perspective. He works at the intersection of inclusive education, disability studies and social psychology.

Lena-Marie Bendfeldt

Lena-Marie Bendfeldt is a teacher. Her master's thesis, written together with Kathrin Jansen at Europa-Universität Flensburg based on some of the group discussions presented here, explored adolescent students perspectives on inclusion in school.

Kathrin Jansen

Kathrin Jansen is a teacher. Her master's thesis, written together with Lena-Marie Bendfeldt at Europa-Universität Flensburg based on some of the group discussions presented here, explored adolescent students perspectives on inclusion in school.

Notes

1 In the German context, ‘integrative education’ and ‘inclusive education’ are often still used interchangeably. Interestingly, the German scholarly movement of integrative education originally shared many theoretical positions with today’s broad understanding of inclusive education. In the course of the 1980-2000s, though, integrative education was often implemented as an individualistic support for disabled students in otherwise unchanged mainstream classrooms (Hinz, Citation2002; Powell, Edelstein and Blanck Citation2016)

2 All citations from the group discussion have been translated by the authors from the German original. Numbers in brackets refer to the location of the excerpt in the transcripts

3 Available household income in the school’s county compared to national German reference level (based on Deutschlandatlas Citation2022). Income statistics are not available for each individual school but for each county (Kreis) the school recruits its students from. NB: School D is a private school with income-dependent school fees, starting from zero fees for children from low-income families.

References

- Adler, Kristin, Sanna Salanterä, and Maya Zumstein-Shaha. 2019. “Focus Group Interviews in Child, Youth, and Parent Research: An Integrative Literature Review.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18: 1–15. doi:10.1177/1609406919887274.

- Ainscow, Mel. 2007. “Taking an Inclusive Turn.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 7 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2007.00075.x.

- Althoff, Frederik. 2021. “Inklusion in den Printmedien: Eine kritische Diskursanalyse zur Inklusion in überregionalen deutschen Tages- und Wochenzeitungen.” (Phd. Diss.). Cologne University.

- Annamma, Subini A., Amy L. Boelé, Brooke A. Moore, and Janette Klingner. 2013. “Challenging the Ideology of Normal in Schools.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 17 (12): 1278–1294. doi:10.1080/13603116.2013.802379.

- Baak, Melanie. 2019. “Racism and Othering for South Sudanese Heritage Students in Australian Schools: Is Inclusion Possible?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (2): 125–141. doi:10.1080/13603116.2018.1426052.

- Baglieri, Susan, Lynne M. Bejoian, Alicia A. Broderick, David J. Connor, and Jan Vall. 2011. “[Re] Claiming “Inclusive Education” Toward Cohesion in Educational Reform: Disability Studies Unravels the Myth of the Normal Child.” Teachers College Record 113 (10): 2122–2154.

- Bates, Helen, Aileen McCafferty, Ethel Quayle, and Karen McKenzie. 2015. “Review: Typically-Developing Students’ Views and Experiences of Inclusive Education.” Disability and Rehabilitation 37 (21): 1929–1939. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.993433.

- Berryman, Mere, and Elizabeth Eley. 2019. “Student Belonging: Critical Relationships and Responsibilities.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (9): 985–1001. doi:10.1080/13603116.2019.1602365.

- Bešić, Edvina. 2020. “Intersectionality: A Pathway Towards Inclusive Education?” Prospects 49 (3–4): 111–122. doi:10.1007/s11125-020-09461-6.

- Biermann, Julia. 2022. Translating Human Rights in Education: The Influence of Article 24 UN CRPD in Nigeria and Germany. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. doi:10.3998/mpub.12000946.

- Boger, Mai-Anh. 2015. “Theorie Der Trilemmatischen Inklusion.” In Herausforderung Inklusion: Theoriebildung Und Praxis, 3rd ed., edited by Irmtraud Schnell, 51–62. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

- Bohnsack, R., and A. Przyborski. 2007. “Gruppendiskussionsverfahren und Focus Groups.” In Qualitative Marktforschung, edited by Renate Buber, and Hartmunt Holzmüller, 491–506. Heidelberg: Springer Link.

- Boxall, K. 2016. “In Praise of Normal: Re-Reading Wolfensberger.” In Theorising Normalcy and the Mundane: Precarious Positions, edited by Rebecca Mallett, Cassandra A. Ogden, and Jenny Slater, 260–281. Chester: Chester University Press.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2022. Thematic Analysis. A Practical Guide. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Brehme, David. 2017. Normalitätskonzepte Im Behinderungsdiskurs: Eine Qualitative Befragung Inklusiv-Beschulter Brandenburger Grundschulkinder. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

- Broer, Stephen M., Mary Beth Doyle, and Michael F. Giangreco. 2005. “Perspectives of Students with Intellectual Disabilities about their Experiences with Paraprofessional Support.” Exceptional Children 71 (4): 415–430.

- Buchner, Tobias. 2018. Die Subjekte der Integration. Schule, Biographie und Behinderung. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

- Buchner, Tobias, and Gertraud Kremsner. 2019. “Behinderung Als Normalität – Normalität Als Behinderung.” In Inklusion Im Spannungsfeld von Normalität Und Diversität: Grundfragen Der Bildung Und Erziehung, edited by Elisabeth von Stechow, Phillip Hackstein, Kirsten Müller, Marie Esefeld, and Barbara Klocke, 145–156. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

- Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung. 2021. “Anteil der Studienberechtigten an der altersspezifischen Bevölkerung (Studienberechtigtenquote) nach Art der Hochschulreife.” BMBF, December 16. https://www.datenportal.bmbf.de/portal/de/Tabelle-2.5.85.html.

- Burke, Catherine, and Ian Grosvenor. 2005. The School I’d Like: Children and Young People’s Reflections on an Education for the 21st Century. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Campbell, Fiona Kumari. 2009. Contours of Ableism. The Production of Disability and Abledness. New York: Springer VS.

- Cefai, Carmel, and Paul Cooper. 2010. “Students without Voices: The Unheard Accounts of Secondary School Students with Social, Emotional and Behaviour Difficulties.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 25 (2): 183–198. doi:10.1080/08856251003658702.

- Connor, David, and Wendy Cavendish. 2020. “‘Sit in my Seat’: Perspectives of Students with Learning Disabilities about Teacher Effectiveness in High School Inclusive Classrooms.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 24 (3): 288–309. doi:10.1080/13603116.2018.1459888.

- Cook-Sather, Alison. 2018. “Tracing the Evolution of Student Voice in Educational Research.” In Radical Collegiality Through Student Voice: Educational Experience, Policy and Practice, edited by Roseanne Bourke, and Judith Loveridge, 17–38. Singapore: Springer Singapore. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-1858-0_2.

- Cummings, Colleen, Alan Dyson, and Alan Millward. 2003. “Participation and Democracy: What’s Inclusion Got to do with It?” In Inclusion, Participation and Democracy: What is the Purpose?, edited by Julie Allan, 49–65. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/0-306-48078-6_4.

- Dalbert, Claudia. 2013. “Die Bedeutung schulischen Gerechtigkeitserlebens für das subjektive Wohlbefinden in der Schule.” In Gerechtigkeit in der Schule, edited by Claudia Dalbert, 127–143. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Danforth, Scot, and Srikala Naraian. 2015. “This New Field of Inclusive Education: Beginning a Dialogue on Conceptual Foundations.” Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 53 (1): 70–85. doi:10.1352/1934-9556-53.1.70.

- Dare, Lynn, and Elizabeth Nowicki. 2018. “Strategies for Inclusion: Learning from Students’ Perspectives on Acceleration in Inclusive Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 69: 243–252. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.10.017.

- Davis, Lennard J. 2014. The End of Normal: Identity in a Biocultural Era. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- Deci, Edward, and Richard Ryan. 2000. “Self-determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” American Psychologist 55 (1): 68–78.

- Deutschlandatlas. 2022. “Verfügbares Einkommen privater Haushalte.” Deutschlandatlas, Accessed 15 July 2022. https://www.deutschlandatlas.bund.de/DE/Karten/Wie-wir-arbeiten/071-Verfuegbares-Einkommen-privater-Haushalte.html.

- De Vroey, Annet, Elke Struyf, and Katja Petry. 2016. “Secondary Schools Included: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 20 (2): 109–135. doi:10.1080/13603116.2015.1075609.

- Dyson, Alan, and Alan Millward. 2000. Schools and Special Needs: Issues of Innovation and Inclusion. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Fend, Helmut. 2005. Entwicklungspsychologie des Jugendalters. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Flitner, Andreas. 1985. “Gerechtigkeit als Problem der Schule und als Thema der Bildungsreform.” Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 31 (1): 1–26.

- Gabryszczak, Nina. 2015. “Themenbereich Inklusion: Die Lehrer müssen auf jeden Fall kompetenter werden, was das angeht.” In Schule aus Schülersicht: Ein Feedback über die Neuerungen in Unterricht und Schule: Alle Schulformen, edited by Ansgar Hüls, and Jost Schneider, 23–49. Berlin: Cornelsen.

- Göransson, Kerstin, and Claes Nilholm. 2014. “Conceptual Diversities and Empirical Shortcomings – A Critical Analysis of Research on Inclusive Education.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 29 (3): 265–280. doi:10.1080/08856257.2014.933545.

- Gorard, Stephen. 2012. “Experiencing Fairness at School: An International Study.” International Journal of Educational Research 53: 127–137. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2012.03.003.

- Greig, Anne, Jane Taylor, and Tommy MacKay. 2012. Doing Research with Children: A Practical Guide. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Hacking, Ian. 2009. “Normal People.” In Modes of Thought: Explorations in Culture and Cognition, edited by David R. Olson, and Nancy Torrance, 59–71. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Hall, Mirko M., and Jürgen Link. 2004. “From the ‘Power of the Norm’ to ‘Flexible Normalism’: Considerations after Foucault.” Cultural Critique 57: 14–32. doi:10.1353/cul.2004.0008.

- Hattie, John. 2008. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hernández-Torrano, Daniel, Michelle Somerton, and Janet Helmer. 2020. “Mapping Research on Inclusive Education Since Salamanca Statement: A Bibliometric Review of the Literature Over 25 Years.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 26 (9): 893–912. doi:10.1080/13603116.2020.1747555.

- Hinz, Andreas. 2002. “Von der Integration zur Inklusion: terminologisches Spiel oder konzeptionelle Weiterentwicklung?” Zeitschrift für Heilpädagogik 53: 354–361.

- Hinz, Andreas. 2017. “Inklusion im Schulsystem.” In Entwicklung und Qualität des deutschen Schulsystems: Neuere empirische Befunde und Entwicklungstendenzen, edited by Hans Günter Holtappels, 173–193. New York: Waxmann.

- Hirschberg, Marianne, and Swantje Köbsell. 2021. “Disability Studies in Education: Normalität/en im inklusiven Unterricht und im Bildungsbereich hinterfragen.” In Handbook of Inclusive Education: Global, National and Local Perspectives, edited by Andreas Köpfer, Justin J. W. Powell, and Raphael Zahnd, 127–146. Berlin: Barbara Budrich.

- Holzkamp, Klaus. 1995. Lernen: subjektwissenschaftliche Grundlegung. Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag.

- Holzkamp, Klaus. 2013. “The Fiction of Learning as Administratively Plannable.” In Psychology from the Standpoint of the Subject: Selected Writings of Klaus Holzkamp, edited by Ernst Schraube, and Ute Osterkamp, 115–132. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Hüls, Ansgar, and Jost Schneider. 2015. Schule aus Schülersicht: ein Feedback über die Neuerungen in Unterricht und Schule. Alle Schulformen. Berlin: Cornelsen.

- Humphrey, Neil, and Sarah Lewis. 2008. “'Make Me Normal’: The Views and Experiences of Pupils on the Autistic Spectrum in Mainstream Secondary Schools.” Autism 12 (1): 23–46. doi:10.1177/1362361307085267.

- Jones, Mari-Ana, and Sara Bubb. 2020. “Student Voice to Improve Schools: Perspectives from Students, Teachers and Leaders in ‘Perfect’ Conditions.” Improving Schools 24 (3): 233–244. doi:10.1177/1365480219901064.

- Kelle, Helga, and Johanna Mierendorff. 2013. Normierung und Normalisierung der Kindheit. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

- Klingner, Janette K., and Sharon Vaughn. 1999. “Students’ Perceptions of Instruction in Inclusion Classrooms: Implications for Students with Learning Disabilities.” Exceptional Children 66 (1): 23–37. doi:10.1177/001440299906600102.

- Kobs, Scarlett, Michel Knigge, and Reinhold Kliegl. 2021. “Gerechtigkeitsbeurteilungen zu SchülerInnen-Lehrkraft-Interaktionen in der inklusiven Schule – Eine experimentelle Studie unter Berücksichtigung sonderpädagogischer Förderbedarfe.” Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 24: 1309–1334. doi:10.1007/s11618-021-01040-5.

- Köbsell, Swantje. 2012. “Anders’ sein dürfen oder ,normal’ sein müssen? Gedanken zum Behinderungsbild in der Inklusionsdebatte.” In Inklusiv Gleich Gerecht? Inklusion Und Bildungsgerechtigkeit, edited by Simone Seitz, Nina-Kathrin Finnern, Natascha Korff, and Katja Scheidt, 180–184. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

- Külker, Anna, Marlena Dorniak, Sabine Geist, Harry Kullmann, Natascha Lutter, Birgit Lütje-Klose, and Christoph Siepmann. 2017. “Schulisches Wohlbefinden als Qualitätsmerkmal im Rahmen eines Lehrer-Forscher-Projekts an der Laborschule Bielefeld.” In Leistung inklusive? Inklusion in der Leistungsgesellschaft II: Unterricht, Leistungsbewertung und Schulentwicklung, edited by Annette Textor, Sandra Grüter, Ines Schiermeyer-Reichl, and Bettine Streese, 48–59. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

- Kultusministerkonferenz. 2020. Sonderpädagogische Förderung in Schulen 2009 bis 2018: Statistische Veröffentlichungen der Kultusministerkonferenz, Dokumentation Nr. 223. KMK, February. Accessed 17 July 2022. https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/pdf/Statistik/Dokumentationen/Dok223_SoPae_2018.pdf.

- Lahelma, Elina. 2002. “School is for Meeting Friends: Secondary School as Lived and Remembered.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 23 (3): 367–381. doi:10.1080/0142569022000015418.

- Leary, Mark R., and Roy F. Baumeister. 1995. “The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachment as a Fundamental Human Motivation.” Psychological Bulletin 117 (3): 497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

- Liasidou, Anastasia. 2012. “Inclusive Education and Critical Pedagogy at the Intersections of Disability, Race, Gender and Class.” Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies 10: 168–184.

- Lindmeier, Christian, and Birgit Lütje-Klose. 2015. “Inklusion als Querschnittsaufgabe in der Erziehungswissenschaft.” Erziehungswissenschaften 26 (51): 7–16.

- Lingenauber, Sabine. 2013. “Normalität.” In Handlexikon Der Integrationspädagogik. Kindertageseinrichtungen, 2nd ed., edited by Sabine Lingenauber, 165–173. Bochum/Freiburg: Projektverlag.

- Lüke, Timo, Matthias R. Hastall, Christian Marschler, and Michael Grosche. 2014. “Was liest man über Inklusion? Konzeption einer Medieninhaltsanalyse deutschsprachiger Printmedien.” Poster Presented at AESF Autumn Conference, Potsdam, November, 28.

- Mallett, Rebecca, Cassandra A. Ogden, and Jenny Slater. 2016. Theorising Normalcy and the Mundane: Precarious Positions. Chester: University of Chester Press.

- Merl, Thorsten. 2021. “In/Sufficiently Able: How Teachers Differentiate between Pupils in Inclusive Classrooms.” Ethnography and Education 16 (2): 198–209. doi:10.1080/17457823.2021.1871853.

- Messiou, Kyriaki. 2017. “Research in the Field of Inclusive Education: Time for a Rethink?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (2): 146–159. doi:10.1080/13603116.2016.1223184.

- Messiou, Kyriaki, and Max A. Hope. 2015. “The Danger of Subverting Students’ Views in Schools.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 19 (10): 1009–1021. doi:10.1080/13603116.2015.1024763.

- Niemeyer, Mona. 2014. “The Right to Inclusive Education in Germany.” The Irish Community Development Law Journal 3 (1): 49–64.

- O’Rourke, John, and Stephen Houghton. 2008. “Perceptions of Secondary School Students with Mild Disabilities to the Academic and Social Support Mechanisms Implemented in Regular Classrooms.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 55 (3): 227–237. doi:10.1080/10349120802268321.

- Pearce, Michelle, Jan Gray, and Glenda Campbell-Evans. 2010. “Challenges of the Secondary School Context for Inclusive Teaching.” Issues in Educational Research 20 (3): 294–313.

- Pfahl, Lisa, and Justin J.W. Powell. 2011. “Legitimating School Segregation. The Special Education Profession and the Discourse of Learning Disability in Germany, 1908-2008.” Disability & Society 26 (2): 449–462.

- Portelli, John P., and Patricia Koneeny. 2018. “Inclusive Education: Beyond Popular Discourses.” International Journal of Emotional Education 10 (1): 133–144.

- Powell, Justin J. W. 2011. Barriers to Inclusion: Special Education in the United States and Germany. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Powell, Justin J. W. 2015. Barriers to Inclusion: Special Education in the United States and Germany. London: Routledge.

- Powell, Justin J. W., Benjamin Edelstein, and Jonna M. Blanck. 2016. “Awareness-raising, Legitimation or Backlash? Effects of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on Education Systems in Germany.” Globalisation Societies and Education 14: 227–250. doi:10.1080/14767724.2014.982076.

- Powell, Mary Ann, Anne Graham, Robyn Fitzgerald, Thomas Nigel, and Nadine Elizabeth White. 2018. “Wellbeing in Schools: What do Students Tell us?” The Australian Educational Researcher 45: 515–531. doi:10.1007/s13384-018-0273-z.

- Prengel, Annedore. 2012. “Kann inklusive Pädagogik die Sehnsucht nach Gerechtigkeit erfüllen? – Paradoxien eines demokratischen Bildungskonzepts.” In Inklusiv Gleich Gerecht? Inklusion Und Bildungsgerechtigkeit, edited by Simone Seitz, Nina-Kathrin Finnern, Natascha Korff, and Katja Scheidt, 16–31. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

- Przyborski, Aglaja, and Julia Riegler. 2010. “Gruppendiskussion und Fokusgruppe.” In Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie, edited by Günter Mey, and Katja Mruck, 436–448. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Rabenstein, Kerstin, Tobias C. Stubbe, and Klaus-Peter Horn. 2020. Inklusion und Gymnasium: Studien zu Perspektiven von Lehrkräften und Studierenden. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen.

- Ramelow, Daniela, and Lisa Gugglberger. 2014. “Die Dimensionen eines gesunden Schulklimas für Schülerinnen und Schüler.” Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung 9 (4): 253–258. doi:10.1007/s11553-014-0436-3.

- Ratner, Helene. 2016. “Modern Settlements in Special Needs Education: Segregated Versus Inclusive Education.” Science as Culture 25 (2): 193–213. doi:10.1080/09505431.2015.1120283.

- Reich, Eberhard. 2008. Schule und Gerechtigkeit. Anspruch und pädagogische Praxis. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Roffey, Sue. 2013. “Inclusive and Exclusive Belonging – The Impact on Individual and Community Well-Being.” Educational and Child Psychology 30 (1): 38–49.

- Rose, Richard, and Michael Shevlin. 2017. “A Sense of Belonging: Children’s Views of Acceptance in “Inclusive” Mainstream Schools.” International Journal of Whole Schooling 13 (1): 65–80.

- Schildmann, Ulrike. 2019. “Inklusive Pädagogik Zwischen Flexibelnormalistischen Und Transnormalistischen (Diskurs-)Strategien. Normalismustheoretische Analyse Gesellschaftlicher Entwicklungen.” In Inklusion Im Spannungsfeld von Normalität Und Diversität Band I : Grundfragen Der Bildung Und Erziehung, edited by Elisabeth Von Stechow, Philipp Hackstein, Kirsten Müller, and Marie Esefeld, 40–56. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

- Schwinger, Malte, Maike Trautner, Nantje Otterpohl, Birgit Lütje-Klose, and Elke Wild. 2020. “Dabei sein ist alles? Psychosoziale Entwicklung von Kindern mit Förderschwerpunkt Lernen in inklusiven vs. exklusiven Fördersettings.” Empirische Sonderpädagogik 12 (1): 64–78.

- Sidanius, Jim, and Felicia Pratto. 2012. “Social Dominance Theory.” In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, edited by Paul A. M. Van Lange, Arie W. Kruglanski, and E. Tory Higgins, 418–438. London: SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781446249222.

- Slee, Roger. 2001. “Social Justice and the Changing Directions in Educational Research: The Case of Inclusive Education.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 5 (2–3): 167–177. doi:10.1080/13603110118387.

- Slee, Roger. 2019. “Belonging in an Age of Exclusion.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (9): 909–922. doi:10.1080/13603116.2019.1602366.

- Speck, Otto. 2019. Dilemma Inklusion. Wie Schule allen Kindern gerecht werden kann. München: Ernst Reinhardt Verlag.

- Thomas, Gary. 2013. “A Review of Thinking and Research about Inclusive Education Policy, with Suggestions for a New Kind of Inclusive Thinking.” British Educational Research Journal 39 (3): 473–490. doi:10.1080/01411926.2011.652070.

- Titchkosky, Tanya, and Rod Michalko. 2009. “Introduction.” In Rethinking Normalcy: A Disability Studies Reader, edited by Tanya Titchkosky, and Rod Michalko, 1–14. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2016. “General Comment No. 4, Article 24: Right to Inclusive Education.” United Nations, November 25. Accessed 17 July 2022. https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no-4-article-24-right-inclusive.

- UNESCO. 2008. Inclusive Education: The Way of the Future. Paris: UNESCO.

- United Nations (UN). 2006. “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).” United Nations. Accessed 04 July 2022. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

- Vandenbussche, Hanne, and Elisabeth De Schauwer. 2018. “The Pursuit of Belonging in Inclusive Education–Insider Perspectives on the Meshwork of Participation.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 22 (9): 969–982. doi:10.1080/13603116.2017.1413686.

- Van Mieghem, Aster, Karine Verschueren, Katja Petry, and Elke Struyf. 2020. “An Analysis of Research on Inclusive Education: A Systematic Search and Meta Review.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 24 (6): 675–689. doi:10.1080/13603116.2018.1482012.

- Wolbring, Gregor. 2008. “The Politics of Ableism.” Development 51 (2): 252–258. doi:10.1057/dev.2008.17.