Abstract

Gambling is a relatively common activity in the Nordic countries, while the incidence and prevalence of problem gambling is relatively stable in this context. Social networks and relationships (e.g., gambling activities among family members and peers) have been put forward as relevant factors to consider when monitoring the epidemiological pathways in regard to gambling and problem gambling. The research on gambling and functional or qualitative aspect of networks and relationships (here labelled psychosocial factors), is however an important emerging area, warranting a synthesis of the evidence. We systematically reviewed the evidence on psychosocial risk factors in relation to gambling and problem gambling in Nordic gambling research. Included articles were identified through systematic searches in 10 scientific databases, covering the time period January 2000–July 2019. Following a systematic screening procedure, the final data set consisted of 21 original studies applying various statistical, interview or narrative methods. The review highlights both less researched psychosocial phenomena and also synthesises the evidence on the most commonly featured psychosocial factors in the included publications – loneliness and social support – evidencing conflicting findings in relation to gambling activities and problem gambling. Although few studies carried evidence to corroborate causal inferences, the risk factors and related epidemiological pathways we identify highlight focal areas that should be considered in both future prevention research and practice, broadening the arena for prevention strategies targeting new health challenges.

Introduction

In this study we systematically review the quantitative and qualitative evidence on psychosocial factors in Nordic gambling studies, assessing the associations, influences or articulated experiences of psychosocial risks in relation to gambling activities and problem gambling reported in the Nordic research literature. We focus on the Nordic context given the prevalent gambling activity and relatively low problem gambling prevalence in these countries, aiming to shed further light on the evidence on psychosocial risk and/or protective factors related to gambling and problem gambling, which could support primary and secondary prevention strategies.

Gambling in the Nordic countries

Gambling is a fairly common leisure activity in the Nordic countries, with past-year gambling participation rates varying between around 60% and 80% among adults (Nordic Welfare Centre, Citation2017). While past-year problem gambling prevalence rates in the Nordic countries are at the same level as the global standardised average rate of 2.3% or lower (Williams, Volberg et al., Citation2012), the broader societal impact of gambling-related harm has been highlighted in the Nordic and international literature (see, for example, Riley et al., Citation2018; Salonen et al., Citation2016). Hence, the Nordic context shows a relatively high frequency of gambling in the population and – from a public health point of view – relatively low and stable problem gambling rates. The question is whether, looking at the Nordic research base, the risk of incidence and prevalence with regard to gambling and problem gambling is influenced by social circumstances ̶ looking at inter-personal psychosocial factors in particular ̶ and in what ways?

Problem gambling from a risk perspective

A public health viewpoint on gambling considers gambling behaviour and related problems on a continuum, with subsequent impacts (be it positive or negative) on the individual, inter-personal, and societal levels (Korn et al., Citation2003; Latvala et al., Citation2019). Factors that can influence gambling behaviour and the risk of a problem gambling development can similarly be viewed on different levels (Abbott et al., Citation2018) ranging from, for example, gambling environment and forms of gambling, to individual factors such as gender, age and socio-economic status. Here, influences of interpersonal networks and relationships, such as gambling activities in one’s family and peer group, also seem to play a role.

Wardle et al. (Citation2018) have earlier presented a socio-ecological model depicting how both harm caused by gambling and also the determinants for problem gambling can be experienced and shaped on individual, family, community and societal levels. Interpersonal harm includes relationship disruption, social isolation and erosion of trust from family, friends and community. The model, integrating both consequential harms and risks, highlights how factors on the interpersonal level such as family or peer gambling culture, but also more general interpersonal factors such as experiences of social support, can be affected by and also influence a person’s gambling engagement and eventual problems. The element of this model encompassing experiences related to one’s social network and relationships, such as perceived social support, will be the focus of this article – here labelled as psychosocial factors or phenomena.

Psychosocial risks and gambling

When considering risk and protective factors for health, a psychosocial framework places emphasis on the pathways and mechanisms mediating the influences of the social determinants on health, more specifically the experience surrounding one’s social network and interpersonal relationships. Martikainen et al. (Citation2002) propose that psychosocial factors are best considered as influences acting primarily between social structural factors and individual-level psychological characteristics. They describe how a social network may provide both instrumental or material aid as well as social contacts and emotional support – but that the contacts and emotional support would qualify as psychosocial. In this study, psychosocial factors are viewed as the functional or qualitative aspect of networks and relationships – such as positive experiences of social support and belonging or negative experiences of loneliness – as opposed to structural factors such as the number of people in one’s network or marital status (Cohen & Wills, Citation1985; Thoits, Citation2011).

Studies from outside the Nordic setting have highlighted various psychosocial factors in relation to gambling initiation, and development of activities and eventual problems over time (Nuske et al., Citation2016; Reith & Dobbie, Citation2011, Citation2013). An earlier review of risk and protective factors for problem gambling development in longitudinal studies (Dowling et al., Citation2017) included a few studies looking at psychosocial factors; however, these studies were not included in the synthesis of the findings due to their low number. Further, Sharman et al. (Citation2019) included some studies focusing on psychosocial factors (as defined in our study) in a review study, but overall their use of the psychosocial concept was much broader encompassing, for example, mental and physical ill-health, and the study was limited to focusing specifically on certain risk groups.

Methodology

Included and excluded studies

This review study synthesises the research on psychosocial factors and their links to gambling activities and related problems. Studies were included in this review based on publication type (original studies included, review studies, editorials and similar excluded) and study content. Regarding content, studies focusing on factors, outcomes or – in the case of interview or narrative studies – themes or categories, related to a person’s social network and relationships are included, in line with the psychosocial concept outlined in the article introduction. Studies focusing on biomedical perspectives of problem gambling, regulatory and legislative issues related to gambling and other topics unrelated to psychosocial themes are excluded from this review.

Database searches and screening

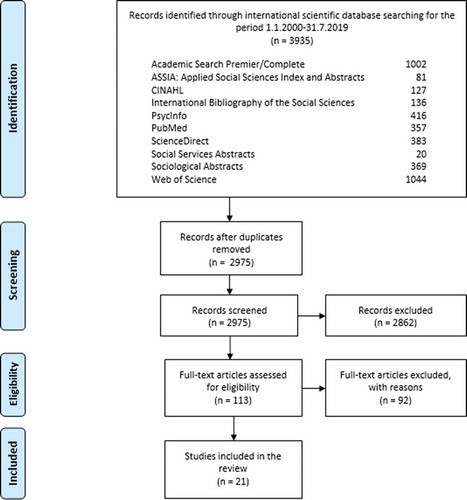

The original search strategies were implemented within the scope of a review exercise (Nordmyr & Forsman, Citation2018) aiming to map (Curran et al., Citation2007; Daudt et al., Citation2013) Nordic gambling studies. Included studies were identified through systematic searches performed in 10 international scientific databases, covering the time period January 2000–July 2019: CINAHL; Academic Search Premier; PsycInfo, Web of Science; Pubmed; ScienceDirect; Sociological Abstracts; Social Services Abstracts; ASSIA: Applied Social Sciences Index Abstracts; International Bibliography of the Social Sciences. The database selection and search strategies are found in the supplemental online material. The number of identified studies in the selected databases and the study screening and selection process can be viewed in . Based on title, abstract and key word information, the first author performed an initial screen of identified studies, where articles clearly irrelevant in relation to the review scope were excluded and original studies potentially focusing on psychosocial factors were identified. Potentially relevant studies or studies where the content remained unclear after the initial screening were thereafter scanned in full text versions for inclusion by both authors. All identified publications reporting on studies applying interview or narrative methods were reviewed in full-text to assess their relevance.

Data extraction and synthesis

We considered the following descriptors for the included records: study design (data/psychosocial measure or dimension/analyses); key findings (emerged themes in interview studies or results of statistical analyses). When reporting on statistical findings, the results of the most advanced analyses are reported. For studies where participants from countries outside the Nordics were also represented, we report on findings applying to the Nordic participants. For studies applying interview or narrative approaches, surfaced themes had to have a comprehensive (thematic) focus on social components. This follows the synthesising or meta-aggregation process outlined by Pearson (Citation2004) where findings in the forms of themes, categories and similar from included review studies are collated.

Quality assessment was performed for the included studies utilising the recognised NICE checklists, with separate systematic guidelines for quantitative and qualitative studies (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2012a, Citation2012b, based on Jackson et al., Citation2006; Spencer et al., Citation2003). Study quality was assessed by one author and unclear cases were discussed between the authors. Internal and external study validity was coded as ++, +, or -. ++ indicated a high-quality score, with all or most checklist criteria fulfilled (where these had not been fulfilled, the conclusions of the study were unlikely to alter, had this been the case). + indicated moderate quality for internal and external validity, where some checklist criteria had been fulfilled, and where they had not been fulfilled (or adequately described), study conclusions were unlikely to alter. – indicated a low-quality score, with few or no of checklist criteria fulfilled and the conclusions of the study could be easily altered.

Findings

Twenty-one publications fulfilled the review inclusion criteria, focusing on psychosocial factors or themes in relation to gambling or problem gambling. The heterogeneity in, for example, research design and outcome measures applied in the studies meant that this review takes the form of a narrative evidence synthesis rather than a meta-analysis. The key findings of all studies are available in . In the following, we present the collected evidence on the psychosocial factors which have been studied in the included gambling articles.

Table 1. The methods and key findings of the included studies (n = 21)

Psychosocial phenomena with a limited evidence base in Nordic research

The collected studies encompassed analysis of several psychosocial phenomena where the evidence is limited to a single study. In one article (Hanss et al., Citation2015), family cohesion was not associated with gambling nor risk-problem gambling among 17-year-old Norwegians. Similarly, Svensson and Sundqvist (Citation2019), did not find family satisfaction to be associated with past-year gambling or frequent gambling among Swedish adolescents. In another study (Lyk-Jensen, Citation2010), respondents’ retrospective views on their childhood and adolescence experiences related to feeling solitary and left out and feeling understood did not differentiate at-risk gamblers from no-risk gamblers (persons experiencing problem gambling were not included in the study). Further, one cross-sectional study (Nordmyr et al., Citation2016) of a Finnish population sample showed a positive association between low levels of neighbourhood trust and problem gambling, but no risk associated with general trust.

Finally, three studies applying interview and narrative methods reported on ‘sense of belonging’ and related features. In an interview study by Svensson (Citation2011), the theme Gambling – lifestyle and identity encompassed the relevant subtheme Electronic and virtual friends, where the author stated that the participants ‘gambling seems to be influenced by their search for belonging and fellowship’. Under the theme Rituals of belonging and self-determination, Matilainen and Raento (Citation2014) noted how the studied narratives reflected feelings of togetherness, belonging. Kristiansen et al. (Citation2015) also mentioned maintaining a sense of belonging to a social community under the theme Peer groups, and feelings of community under the theme Family, in their results.

The collected evidence on experienced loneliness – quantitative findings

Several studies in the synthesised material looked at experienced loneliness in relation to gambling activities and problem gambling, evidencing mixed results. In one Finnish population study (Castrén et al., Citation2013) loneliness was associated with problem gambling in regression analysis, interestingly however it was not associated with more severe gambling-related problems (such as gambling disorder). In another cross-sectional Finnish study looking at a population sample (Nordmyr et al., Citation2016), loneliness was associated with problem gambling. Sirola et al. (Citation2019) found that excessive gambling was higher among young Finns who reported higher levels of loneliness, with loneliness also positively moderating the association between excessive gambling and daily online gambling community participation in one of the included study samples. On the other hand, a Finnish study did not show loneliness to be associated with at-risk or problem gambling among young men or women in the most comprehensive models applied in the study (Edgren et al., Citation2016). Further, a study looking at loneliness in relation to gambling or risk-problem gambling among Norwegian youth evidenced no significant results (Hanss et al., Citation2015). Another Norwegian study (Sagoe et al., Citation2017) similarly showed that neither loneliness at age 19 nor at age 17 were associated with gambling or risk-and problem gambling. Loneliness was, however, associated with lower odds of risk-or problem gambling, compared to no gambling, among 17-year-olds. In a population study by Castrén et al. (Citation2018) loneliness was not included in regression analyses predicting gambling expenditure in order to avoid multi-collinearity.

The collected evidence on experienced loneliness – qualitative findings

An interview and observation study (Lalander, Citation2006) exploring social dimensions of Swedish gambling machine environments specifically mentioned loneliness in the results section under the theme The gamblers and the staff/owners of restaurants: ‘For the customer, who might otherwise have felt lonely, this social contact nonetheless had great importance’. In the group interview material studied by Pöysti and Majamäki (Citation2013), an emerged theme was Social and situational pathways. Here, Finnish and French recreational gamblers expressed the view that social and situational issues such as loneliness and relationship problems were risk pathways that may lead to problem gambling. Finally, interview data from the longitudinal Swedish Swelogs study (Samuelsson et al., Citation2018) showed that important life events (many of them of a social nature such as relationship breakdown) and Lack of supportive network and meaningful employment were identified as factors increasing the risk for increased gambling engagement and related problems. Here the authors specifically mention that ‘Loneliness, unemployment, and problems with social relations were also reported as reasons for gambling taking precedence in life’ (p. 518).

The collected quantitative evidence on experienced social support

The results concerning social support – either from parents, peers or other people, e.g., teachers – were mixed. A Finnish study (Räsänen et al., Citation2016a) found that social support from parents and school staff decreased gambling among both boys and girls, whereas social support from friends increased boys’ gambling (no association for girls). Räsänen et al. (Citation2016b), utilising the same data, mirrored these results for boys and girls with regard to support from parents and school personnel and also the positive association between boys gambling and social support from friends. However, for girls, social support from friends was negatively associated with gambling. Another study (Oksanen et al., Citation2019), found that weaker social support from close people was associated with competent gambling among young Finns, while higher perceived social support was associated with entertainment gambling. In another Finnish study, no direct associations were found between social support from close people and problem gambling, while high levels of social support did moderate the association between peer group identification and problem gambling (Savolainen et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, Fröberg et al. (Citation2013) did not find social support to be associated with gambling among young Swedes, and Nordmyr et al. (2016) did not find social support to be associated with problem gambling in a Finnish sample. A Swedish longitudinal population study similarly found that social support did not predict online gambling (Svensson & Romild, Citation2011).

The collected qualitative evidence on experienced social support

Looking at longitudinal interview data, Samuelsson et al. (Citation2018) found that factors increasing gambling included important life events (many of them of a social nature), and Lack of supportive network while Support from significant others also appeared when looking at factors decreasing gambling and helping a person abstain from gambling.

Research design of the included studies

When reviewing study quality (see ), the majority of included studies were rated as being of good quality. Six of the included studies applied different interview, observation or narrative methods while the remaining 15 studies applied statistical approaches. Considering the studies applying statistical methods, most were of a cross-sectional nature utilising representative population survey data. Four publications utilised data from one or more waves of longitudinal or follow-up studies (Kristiansen et al., Citation2015; Lyk-Jensen, Citation2010; Sagoe et al., Citation2017; Samuelsson et al., Citation2018). Regarding measurement of a psychosocial dimension, several standardised instruments and scales were used alongside single-item questions (see for full range of measures), for example, Roberts’s 8-item loneliness scale (Roberts et al., Citation1993); the Oslo 3-item Social Support Scale (OSS-3, Brevik & Dalgard, Citation1996); and the six-item Family Relations/Cohesion scale (as described in Oregon Mentors, Citation2019). Statistical methods used can be found in .

Within the cluster of studies applying a qualitative design, varying individual and focus group approaches, ethnographic observations and elicited written data methods were used. Further information on the analyses and common themes generated from the collected data can be viewed in .

Discussion

In this review, we focused on psychosocial factors – functional or qualitative aspect of networks and relationships – in relation to gambling and problem gambling; an under-explored research area. The heterogeneity in research design and outcome measures used in the included studies meant that this review takes the form of a narrative evidence synthesis. We limited our review to studies carried out in Nordic contexts where loneliness and social support emerged as the most commonly studied psychosocial phenomena. The included studies also encompassed analysis of psychosocial phenomena such as family cohesion or family satisfaction, where the evidence is limited to a single study applying quantitative methods. The evidence on feelings of belonging and togetherness was on the other hand limited to interview studies.

The results regarding experienced loneliness and social support are mixed, with varying evidence concerning the role and direction of psychosocial pathways, in part due to most of the included studies being of a cross-sectional nature. Here studies applying qualitative approaches serve to highlight the inherent complexity of psychosocial phenomena. As earlier highlighted by Holdsworth et al. (Citation2015), psychosocial factors may constitute risk and protective factors in themselves, they can be the result of problems related to gambling, and they can also have a mediating/moderating effect on the links between various factors and gambling or problem gambling through functioning as resiliency factors and in influencing coping (for example, social support). In the study by Savolainen et al. (Citation2019), no direct associations were found between social support and problem gambling, while social support moderated the association between peer group identification and problem gambling. Among Finnish young people, problem gambling was more common among those who strongly identified with an online peer group but experienced low social support.

Reith and Dobbie (Citation2013) have earlier highlighted inter- and intra-individual variance in positive or negative consequences of life events and social networks for both reducing and increasing gambling behaviour. The Swedish longitudinal study by Samuelsson et al. (Citation2018) echoes these findings and illustrates well the complexity in the role of psychosocial factors as both risk and supportive factors. This can help explain the differing, arguably contradictory, results of some studies. Räsänen et al. (Citation2016a), for example, showed that gambling among boys was correlated with positive social support from friends (as opposed to negative correlations with support from parents or school staff). This result can be considered in light of an earlier study showing that young people who get along with, and are liked by, their peers were found to be more at risk for problem gambling (Yücel et al., Citation2015). On the other hand, the study by Sagoe et al. (Citation2017) included in this review found loneliness among 17-year-olds as a factor decreasing the risk of problem gambling.

Given these aforementioned examples of the complexity of psychosocial phenomena, it is viewed as a particular strength that the multi-level model of Wardle et al. (Citation2018) highlights how risk factors on interrelated levels can act as determinants of problem gambling and also how harms can be experienced across these levels. Our review findings support the recognition of not only structural factors related to an individuals’ social networks and relationships in this model, but also related experiences, as risk (but also in some instances protective) factors to consider in relation to the onset, occurrence or reoccurrence of problem gambling. While social support is the only psychosocial factor (as labelled in this review) included in the model, our findings highlight loneliness as a factor also evidencing some research support. As emphasised by Wardle and colleagues and also Abbott et al. (Citation2018), a sole focus on personal characteristics in relation to problem gambling overlooks relevant contextual features. The findings of this review support and strengthen this notion that prevention should not concentrate exclusively on risk and protective factors at the individual or societal and communal levels, but also action to influence and mitigate risks at the inter-personal level.

Together with other approaches to health epidemiology such as life course approaches, the psychosocial approach directs more research emphasis to the risk and protective pathways and mechanisms mediating the influences of multi-level social determinants on health and health problems. While it is established that social factors on the macro-level, shaped by socioeconomic and political context, as well as individual-level circumstances and socioeconomic position contribute to a person´s experience of health and wellbeing (e.g., Marmot et al., Citation2012), individual-level psychosocial factors are increasingly recognised as influencing these effects (Aldabe et al., Citation2011; Moor et al., Citation2014, Citation2017). The findings from these large-scale studies highlight psychosocial factors such as social support as a target for prevention interventions to decrease broad health inequalities due to their direct and indirect impacts on health.

In the context of gambling activities and related potential risks more specifically, the limited but growing evidence on psychosocial pathways offers a basis for new approaches, warranting new multi-professional cooperation in both the implementation and evaluation of prevention initiatives. This should be considered in relation to the field of primary and secondary prevention interventions targeting problem gambling, where the majority of existing interventions aim to control the gambling environment and the promotion of responsible gambling by individuals (McMahon et al., Citation2019; Williams, West et al., Citation2012). Factors such as support networks, provide a framework on which prevention and support interventions can be based (Holdsworth et al., Citation2015).

Study limitations

Common limitations in review methodology concern for example, journal indexing or bibliographical information records affecting the screening process. It is considered a strength that the search strategies focused on gambling studies broadly, limiting the risk of missing studies due to narrow interpretations or labelling of psychosocial concepts by the reviewers. As this review is limited to publications in international scientific journals, potentially relevant studies published in more limited fora (in terms of e.g., language) are not included. The strength of limiting the review to these publications is increased rigour through e.g., systematic and detailed information in publication coding in research databases as well as improved possibilities for study replication. As database searches were not limited to certain study designs or methods, studies applying various interview or narrative approaches were screened for inclusion. It can be noted that the number of Nordic gambling studies applying interview or narrative methods is limited in number compared to those applying statistical methods – a gap in the field in itself.

The overall quality of the studies included in the review was overall high. We do not consider that the removal of three studies with a higher level of perceived limitations would have drastically altered our review findings.

This review was limited to the Nordic context. From the risk approach perspective, it is justified to focus on the unique welfare state context that the Nordic countries constitute (e.g., Esping-Andersen, Citation1990). The Nordic context simultaneously exhibits high prevalence of gambling activities and, from a public health point of view, relatively low rates of problem gambling within the population (Nordic Welfare Centre, Citation2017). This motivates the study of social circumstances and especially the under-researched psychosocial risk factors evidencing influences on, or associations with, gambling or problem gambling in this context. Apparent differences in three included studies encompassing comparative elements with participants from the U.S. (Savolainen et al., Citation2019; Sirola et al., Citation2019) and France (Pöysti & Majamäki, Citation2013) mean that the applicability of review results to other contexts is cautioned.

Conclusion

Our research contributes to synthesising the limited evidence base on psychosocial risks and pathways in relation to gambling-related issues in the Nordic context where gambling is prevalent. The findings highlight lesser researched psychosocial phenomena and synthesise the evidence on the most commonly featured psychosocial factors in the included publications – loneliness and social support. Although few studies carried evidence supporting causal inferences, the review findings highlight focal areas that should be considered in future research and practice, broadening the concept of social factors and circumstances by including also inter-personal psychosocial factors in the understanding of the risk pathways and related prevention strategies targeting problem gambling.

CHRS-2019-0104-File004.doc

Download MS Word (60.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- Abbott, M., Binde, P., Clark, L., Hodgins, D., Johnson, M., Manitowabi, D., Quilty, L., Spångberg, J., Volberg, R., Walker, D., & Williams, R. (2018). Conceptual framework of harmful gambling: An international collaboration (3rd ed.). Gambling Research Exchange Ontario (GREO).

- Aldabe, B., Anderson, R., Lyly-Yrjänäinen, M., Parent-Thirion, A., Vermeylen, G., Kelleher, C. C., & Niedhammer, I. (2011). Contribution of material, occupational, and psychosocial factors in the explanation of social inequalities in health in 28 countries in Europe. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 65(12), 1123–1131. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.102517

- Bonke, J. (2007). Ludomani i Danmark II Faktorer af betydning for spilleproblemer [Gambling in Denmark II factors involved in problem gambling]. Institute of Social Research.

- Brevik, J. I., & Dalgard, O. (1996). The Oslo health profile inventory. Oslo, Norway: University of Oslo.

- Castrén, S., Basnet, S., Salonen, A. H., Pankakoski, M., Ronkainen, J. E., Alho, H., & Lahti, T. (2013). Factors associated with disordered gambling in Finland. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 8(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-8-24

- Castrén, S., Kontto, J., Alho, H., & Salonen, A. H. (2018). The relationship between gambling expenditure, socio‐demographics, health‐related correlates and gambling behaviour—a cross‐sectional population‐based survey in Finland. Addiction, 113(1), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13929

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

- Curran, C., Burchardt, T., Knapp, M., McDaid, D., & Li, B. (2007). Challenges in Multidisciplinary Systematic Reviewing: A Study on Social Exclusion and Mental Health Policy. Social Policy & Administration, 41(3),289–312. doi:10.1111/spol.2007.41.issue-3

- Daudt, H. M. L., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

- Dowling, N. A., Merkouris, S. S., Greenwood, C. J., Oldenhof, E., Toumbourou, J. W., & Youssef, G. J. (2017). Early risk and protective factors for problem gambling: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.008

- Edgren, R., Castrén, S., Jokela, M., & Salonen, A. H. (2016). At-risk and problem gambling among Finnish youth: The examination of risky alcohol consumption, tobacco smoking, mental health and loneliness as gender-specific correlates. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 33(1), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1515/nsad-2016-0005

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Polity Press.

- Fröberg, F., Hallqvist, J., & Tengstrom, A. (2013). Psychosocial health and gambling problems among men and women aged 16-24 years in the Swedish national public health survey. European Journal of Public Health, 23(3), 427–433. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cks129

- Hanss, D., Mentzoni, R. A., Blaszczynski, A., Molde, H., Torsheim, T., & Pallesen, S. (2015). Prevalence and correlates of problem gambling in a representative sample of Norwegian 17-year-olds. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(3), 659–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9455-4

- Holdsworth, L., Nuske, E., & Hing, N. (2015). A grounded theory of the influence of significant life events, psychological co-morbidities and related social factors on gambling involvement. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13(2), 257–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-014-9527-9

- Jackson, R., Ameratunga, S., Broad, J., & Heneghan, C. (2006). The GATE frame: Critical appraisal with pictures. Evidence Based Medicine, 11(2), 35–38. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebm.11.2.35

- Korn, D., Gibbins, R., & Azmier, J. (2003). Forming public policy towards a public health paradigm for gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 19(2), 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023685416816

- Kristiansen, S., Trabjerg, M. C., & Reith, G. (2015). Learning to gamble: Early gambling experiences among young people in Denmark. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.933197

- Lalander, P. (2006). Swedish machine gamblers from an ethnographic perspective. Journal of Gambling Issues, 18(18), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2006.18.5

- Latvala, T., Lintonen, T., & Konu, A. (2019). Public health effects of gambling – Debate on a conceptual model. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7391-z

- Lyk-Jensen, S. (2010). New evidence from the grey area: Danish results for at-risk gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 26(3), 455–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-009-9173-5

- Marmot, M., Allen, J., Bell, R., Bloomer, E., & Goldblatt, P. (2012). WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. The Lancet, 380(9846), 1011–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8

- Martikainen, P., Bartley, M., & Lahelma, E. (2002). Psychosocial determinants of health in social epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(6), 1091–1093. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/31.6.1091

- Matilainen, R., & Raento, P. (2014). Learning to gamble in changing sociocultural contexts: Experiences of Finnish casual gamblers. International Gambling Studies, 14(3), 432–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2014.923484

- McMahon, N., Thomson, K., Kaner, E., & Bambra, C. (2019). Effects of prevention and harm reduction interventions on gambling behaviours and gambling related harm: An umbrella review. Addictive Behaviors, 90, 380–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.048

- Moor, I., Rathmann, K., Stronks, K., Levin, K., Spallek, J., & Richter, M. (2014). Psychosocial and behavioural factors in the explanation of socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent health: A multilevel analysis in 28 European and North American countries. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68(10), 912–921. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-203933

- Moor, I., Spallek, J., & Richter, M. (2017). Explaining socioeconomic inequalities in self-rated health: A systematic review of the relative contribution of material, psychosocial and behavioural factors. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71(6), 565–575. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-207589

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2012a). Appendix G quality appraisal checklist – Quantitative studies reporting correlations and associations. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Retrieved May 10, from https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/appendix-g-quality-appraisal-checklist-quantitative-studies-reporting-correlations-and

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2012b). Appendix H quality appraisal checklist – Qualitative studies. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Retrieved May 10, from https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/appendix-h-quality-appraisal-checklist-qualitative-studies#ftn.footnote_17

- Nordic Welfare Centre. (2017). Gambling in the Nordic countries. Nordic Welfare Centre. Retrieved May 15, 2020, from https://nordicwelfare.org/en/nyheter/gambling-in-the-nordic-countries/

- Nordmyr, J., & Forsman, A. K. (2018). A systematic mapping of nordic gambling research 2000–2015: Current status and suggested future directions. Addiction Research & Theory, 26(5), 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2018.1426753

- Nordmyr, J., Forsman, A. K., & Österman, K. (2016). Problematic alcohol use and problem gambling: Associations to structural and functional aspects of social ties in a Finnish population sample. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 33(4), 381. https://doi.org/10.1515/nsad-2016-0032

- Nuske, E. M., Holdsworth, L., & Breen, H. (2016). Significant life events and social connectedness in Australian women’s gambling experiences. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 33(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1515/nsad-2016-0002

- Oksanen, A., Sirola, A., Savolainen, I., & Kaakinen, M. (2019). Gambling patterns and associated risk and protective factors among Finnish young people. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 36(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072518779657

- Oregon Mentors. (2019). Family relations/Cohesion scale. Oregon Mentors. Retrieved August 1 from http://oregonmentors.org

- Pearson, A. (2004). Balancing the evidence: Incorporating the synthesis of qualitative data into systematic reviews. JBI Reports, 2(2), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-6988.2004.00008.x

- Pöysti, V., & Majamäki, M. (2013). Cultural understandings of the pathways leading to problem gambling: Medical disorder or failure of self-regulation? Addiction Research & Theory, 21(1), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2012.691580

- Räsänen, T., Lintonen, T., Tolvanen, A., & Konu, A. (2016a). Social support as a mediator between problem behaviour and gambling: A cross-sectional study among 14-16-year-old Finnish adolescents. BMJ Open, 6(12), e012468. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012468

- Räsänen, T., Lintonen, T., Tolvanen, A., & Konu, A. (2016b). The role of social support in the association between gambling, poor health and health risk-taking. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 44(6), 593–598. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494816654380

- Reith, G., & Dobbie, F. (2011). Beginning gambling: The role of social networks and environment. Addiction Research & Theory, 19(6), 483–493. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2011.558955

- Reith, G., & Dobbie, F. (2013). Gambling careers: A longitudinal, qualitative study of gambling behaviour. Addiction Research & Theory, 21(5), 376–390. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2012.731116

- Riley, B. J., Harvey, P., Crisp, B. R., Battersby, M., & Lawn, S. (2018). Gambling-related harm as reported by concerned significant others: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of empirical studies. Journal of Family Studies, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2018.1513856

- Roberts, R. E., Lewinsohn, P. M., & Seeley, J. R. (1993). A brief measure of loneliness suitable for use with adolescents. Psychological Reports, 72(3_suppl), 1379–1391. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3c.1379

- Romild, U., Volberg, R., & Abbott, M. (2014). The Swedish longitudinal gambling study (Swelogs): Design and methods of the epidemiological (EP-) track. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 23(3), 372–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1449

- Sagoe, D., Pallesen, S., Hanss, D., Leino, T., Molde, H., Mentzoni, R. A., & Torsheim, T. (2017). The relationships between mental health symptoms and gambling behavior in the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 478. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00478

- Salonen, A. H., Alho, H., & Castrén, S. (2016). The extent and type of gambling harms for concerned significant others: A cross-sectional population study in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 44(8), 799–804. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494816673529

- Samuelsson, E., Sundqvist, K., & Binde, P. (2018). Configurations of gambling change and harm: Qualitative findings from the Swedish longitudinal gambling study (Swelogs). Addiction Research & Theory, 26(6), 514–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2018.1448390

- Savolainen, I., Sirola, A., Kaakinen, M., & Oksanen, A. (2019). Peer group identification as determinant of youth behavior and the role of perceived social support in problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9813-8

- Sharman, S., Butler, K., & Roberts, A. (2019). Psychosocial risk factors in disordered gambling: A descriptive systematic overview of vulnerable populations. Addictive Behaviors, 99, 106071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106071

- Sirola, A., Kaakinen, M., Savolainen, I., & Oksanen, A. (2019). Loneliness and online gambling-community participation of young social media users. Computers in Human Behavior, 95, 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.023

- Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Dillon, L., & National Centre for Social Research. (2003). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence. Government Chief Social Researcher’s Office.

- Svensson, J., & Romild, U. (2011). Incidence of internet gambling in Sweden: Results from the Swedish longitudinal gambling study. International Gambling Studies, 11(3), 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2011.629203

- Svensson, J., & Sundqvist, K. (2019). Gambling among Swedish youth: Predictors and prevalence among 15-and 17-year-old students. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 36(2), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072518807788

- Svensson, O. (2011). Gambling: Electronic friends or a threat to one’s health and personal development? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 6(2), 7207. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v6i2.7207

- Thoits, P. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395592

- Wardle, H., Reith, G., Best, D., McDaid, D., & Platt, S. (2018). Measuring gambling-related harms: A framework for action. Gambling Commission.

- Williams, R. J., Volberg, R. A., & Stevens, R. M. G. (2012, May 8). The population prevalence of problem gambling: Methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences, and Worldwide trends. Guelph: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.

- Williams, R. J., West, B. L., & Simpson, R. I. (2012, October 1). Prevention of problem gambling: A comprehensive review of the evidence and identified best practices. Guelph: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

- Yücel, M., Whittle, S., Youssef, G. J., Kashyap, H., Simmons, J. G., Schwartz, O., Lubman, D. I., & Allen, N. B. (2015). The influence of sex, temperament, risk-taking and mental health on the emergence of gambling: A longitudinal study of young people. International Gambling Studies, 15(1), 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2014.1000356