Abstract

Background

Role modelling is recognised as an important element in career choice. In strongly hospital-based medical education settings, students identify few primary care physicians as positive role models, which might impact their career plans and potentially contribute to primary care workforce shortage. At Geneva Faculty of Medicine (Switzerland), a compulsory final-year clerkship in primary care practices was introduced to strengthen primary care teaching in the curriculum.

Objectives

To assess the proportion of graduating students identifying a primary care physician as positive role model, before and after the introduction of the clerkship.

Methods

Cross-sectional survey in four consecutive classes of graduating medical students one year before and three years after the introduction of the clerkship. The main outcome measure was the proportion of students in each class citing a primary care physician role model. Comparisons were analysed using Pearson’s Chi-square test and one-way ANOVA.

Results

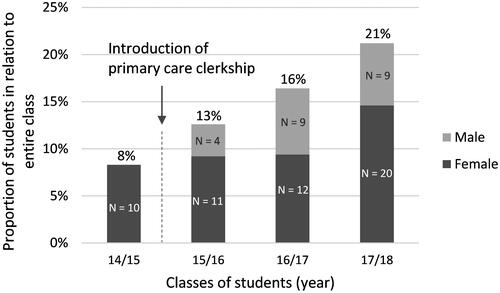

The total sample included 505 students. The proportion of students recalling a primary care physician role model increased steadily from 8% (before introduction of the clerkship) to 13, 16, and 21%, respectively, at 1, 2 and 3 years after the introduction of the clerkship (p = 0.03).

Conclusion

Our exploratory study suggests that introducing a compulsory primary care clerkship may have contributed to increasing the visibility of primary care physicians as role models. Future research should explore primary care physicians’ awareness of role modelling and its contribution to career choices.

KEY MESSAGES

Positive role modelling by primary care physicians increased after introducing an undergraduate primary care clerkship.

The results suggest that exposing students to primary care could contribute to greater visibility of primary care physicians.

This increased visibility may be an opportunity to act on students’ attitudes towards primary care.

Introduction

Medical students’ speciality choice determines the future physician workforce. Medical schools have recognised their impact on students’ career decisions and have increased exposure to primary care, although these efforts vary between and within countries [Citation1].

Career choice is a multifactorial process in which role modelling is one piece of the puzzle [Citation2,Citation3]. Primary care physicians (PCPs) may act as role models, positively and negatively affecting students’ attitudes towards primary care [Citation4,Citation5]. Clinical clerkships are an important opportunity for PCPs to demonstrate the main role modelling attributes of clinical expertise, teaching skills, and personal qualities [Citation2].

Research on role modelling in primary care has mainly focussed on positive or negative attitudes perceived by students and has suggested that there may be a lack of positive role models in primary care [Citation5,Citation6]. Yet, we know little about the magnitude of the phenomenon, i.e. the number of students identifying specific role models in primary care. Taking advantage of a newly introduced primary care clerkship, we aimed to explore PCPs’ role modelling quantitatively. Specifically, we wanted to know what proportion of final-year students actively remembered a PCP as a positive role model. We hypothesised that this proportion would increase after the introduction of the clerkship since students were more exposed to primary care.

Methods

Context

The study was conducted at the Faculty of medicine at the University of Geneva, Switzerland. The undergraduate curriculum lasts six years: A pre-selection year (year 1), pre-clinical years with mostly problem-based teaching (years 2 and 3), a clinical curriculum with mostly hospital-based rotations (years 4 and 5), and a final elective clinical year (year 6), during which students choose their rotations. Graduates may then freely choose their speciality for postgraduate training. In Geneva, at the beginning of this study (i.e. until 2014), primary care was taught through lectures during the pre-clinical years and clinical clerkships in primary care in year 2 (four half-days) and year 4 (eight half-days) [Citation7]. Since 2015, efforts have been made to increase students’ exposure to primary care and a compulsory one-month clerkship in primary care practices was introduced in the final year (starting in the academic year 2015/16). Students freely choose the practice and timing of their clerkship, which can take place at any time during the academic year. Participating PCPs are informed about the clerkships’ learning objectives and are encouraged to participate in training sessions.

In Switzerland, there is no specific primary care specialisation such as ‘general practice.’ The primary care workforce is made up of general internists and paediatricians working in private practice. There is no mandatory gatekeeping system.

Study design

Cross-sectional study in four consecutive academic years, starting in 2014/15 (i.e. the year before introducing the primary care clerkship).

Participants

All final-year medical students in the relevant academic years were invited to participate at the end of their final semester.

Measurements and analysis

Two questions, inspired by the prevailing definition of role modelling in the literature [Citation2], were added to an existing paper-and-pencil survey, whose original aim was to investigate students’ academic progression and career choices, and which was not directly related to primary care: (1) During your studies, did you identify a person you want to resemble professionally? (2) if yes, what was that person’s position? (open-ended question). Students also provided gender, age, and current career intention. Answers to closed-ended questions were extracted automatically by scanning the questionnaires; handwritten responses to the second question were extracted manually. Answers about role models and career intentions were categorised into primary care and non-primary care, using the Swiss definition of primary care (a speciality of general internal medicine or paediatrics, plus private practice as practice type). We compared the sample characteristics and the distribution of the outcome by year, calculating Pearson’s Chi-square to compare frequencies and one-way ANOVA to compare means. Stata® (StataCorp. 2017 Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LLC) was used for all statistical tests. A level of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Per applicable law in Switzerland, the study was granted a waiver from approval by the Ethical Committee of the Canton of Geneva.

Results

The relevant survey questions were completed by 505 students (overall response rate 85%). presents the characteristics and outcomes, which were similar over the four years in terms of gender, age and number of students recalling any role model. Overall, 18% of students intended to become PCPs, and this proportion remained unchanged. The number and proportion of students identifying a PCP role model progressively and significantly increased over the three years after the introduction of the clerkship (). The numbers for the outcome were too small for a statistically valid comparison by gender.

Figure 1. The Figure presents the proportions of final year medical students recalling a primary care physician role model in a cross-sectional survey administered one year before and in each of the three years following the introduction of a compulsory final-year clerkship in primary care practices. Percentages relate to the proportion of all students in each class. N = number of females and males, respectively.

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics and cross-sectional survey results, presented by class of students (academic year).

Discussion

Main findings

In this exploratory cross-sectional study, we found that the proportion of final-year students recalling a PCP as positive role model progressively increased in the three years following the introduction of a primary care clerkship. However, we did not observe a change in the proportion of students intending to become PCPs.

Strengths and limitations

Our study’s main strength is that the survey was unrelated to a specific clerkship or primary care and that we used an open-ended question, allowing us to explore the role models actively recalled by students. The main limitation is the cross-sectional, observational design, not allowing for detailed investigation of processes and longer-term impacts. Using an already existing survey, the number of questions was limited. Thus, we did not investigate contextual factors which could impact role modelling, notably the timing of the clerkship. Students having had the clerkship more recently could have remembered a PCP more often than others through recall bias. Also, we cannot conclude that a causal relationship exists between the clerkship and role modelling. Additional factors may have contributed to this association, such as other curricular activities in earlier study years or societal factors (e.g. media campaigns favouring primary care or political support). As our study took place in a single medical school, the findings may have limited generalisability. Nevertheless, given the heterogeneity of the primary care situation in Europe (in terms of the importance of primary care in the health system and in medical education) [Citation1], there may be contexts similar to ours for which our findings could be of interest.

Interpretation of results

We are unaware of studies using a similar method to explore the proportion of students recalling a specific positive role model. More than three-quarters of students in our study mentioned having encountered a positive role model during their studies, confirming the overall importance of role modelling in medical education, as previously described in the literature [Citation2].

Despite our study’s limitations, the finding that more students recalled a PCP as their positive role model is encouraging, meaning that the clerkship may have contributed to PCPs being more visible, representing an opportunity to make primary care a more attractive career option [Citation4]. However, we need to keep in mind that negative role modelling may happen, too, when PCPs transmit a discouraging image of their practice [Citation5]. Although most clinical preceptors seem to be aware of the importance of role modelling, many don’t use it explicitly as an educational method [Citation8]. Thus, most clinicians – including PCPs – could benefit from explicit training to become more effective role models.

We did not observe changes in students’ career intentions regarding primary care. Although this finding may be related to our study’s limitations and represent a short-term outcome, we interpret this in the context of the multifactorial nature of career decisions [Citation3]. Many studies have described the positive impact of primary care clerkships on students’ career choices but their impact depends on the nature and quality of the clerkship and the broader curricular and extra-curricular context [Citation9]. Thus, we would not expect a single clerkship to influence students’ career intentions instantly.

The increase in PCPs’ role modelling without a concomitant increase in primary care career intentions could mean that PCPs may also act as positive role models for students who do not intend to become PCPs. It has been suggested that undergraduate clinical experiences should not be limited to promoting primary care as a career choice but may benefit all future physicians [Citation10]. PCPs may take advantage of their unique position in hospital-focussed educational contexts by modelling a type of practice that students are less exposed to in hospital rotations, such as patient-centred, comprehensive, and community-based care. PCPs could thus impact students’ overall professional identity formation, helping them determine what type of doctor they want to be, beyond speciality choice.

Conclusion

Our exploratory study suggests that introducing a compulsory primary care clerkship may increase PCPs’ visibility and offer them the opportunity to act as positive role models. Their impact may be beneficial for all students, independently of their career intentions. Future research should focus on PCPs' awareness of being role models and the possible implications on students' attitudes towards primary care and career choices.

Prior presentations

The outcomes of this study have been presented as a conference abstract at the 47th NAPCRG Annual Meeting in Toronto, Canada, November 16–20, 2019.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brekke M, Carelli F, Zarbailov N, et al. Undergraduate medical education in general practice/family medicine throughout Europe – a descriptive study. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:157.

- Passi V, Johnson S, Peile E, et al. Doctor role modelling in medical education: BEME guide no. 27. Med Teach. 2013;35(9):e1422–e1436.

- Pfarrwaller E, Audétat MC, Sommer J, et al. An expanded conceptual framework of medical students’ primary care career choice. Acad Med. 2017;92(11):1536–1542.

- Deutsch T, Lippmann S, Frese T, et al. Who wants to become a general practitioner? Student and curriculum factors associated with choosing a GP career-a multivariable analysis with particular consideration of practice-orientated GP courses . Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(1):47–53.

- Wass V, Gregory S, Petty-Saphon K. By choice—not by chance: supporting medical students towards future careers in general practice. London: Health Education England and the Medical Schools Council; 2016.

- Parekh R, Jones MM, Singh S, et al. Medical students' experience of the hidden curriculum around primary care careers: a qualitative exploration of reflective diaries. BMJ Open. 2021;11(7):e049825.

- Tandjung R, Ritter C, Haller DM, et al. Primary care at Swiss universities-current state and perspective. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:308.

- Cote L, Laughrea PA. Preceptors' understanding and use of role modeling to develop the CanMEDS competencies in residents. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):934–939.

- Pfarrwaller E, Sommer J, Chung C, et al. Impact of interventions to increase the proportion of medical students choosing a primary care career: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1349–1358.

- Lawson E, Kumar S. The Wass report: moving forward 3 years on. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(693):164–165.