Abstract

The early intervention Språkstart Halland targets children aged 0–3 years. During home visits at 6 and 11 months, library staff deliver gift-packs containing books, toys, songs, and rhymes to promote early language stimulation. Parents are encouraged to engage in ‘talk, play, sing, read’ activities to support language development. The aim of the present study was to examine parents’ experiences of the 6- and 11-month visits and develop an understanding of their general impressions and thoughts regarding the perceived impact of the visits. Parents (n = 15) were interviewed in four focus groups and two one-on-one interviews. Data was analysed using qualitative content analysis. The findings show that the intervention changed the parents’ mindset and increased their knowledge regarding early language stimulation. Tools and strategies benefitting the parent-child interaction were gained. A positive experience and personal guidance created motivation for the parents to carry out the language stimulating activities after the visit. Social gains were described. The findings imply usefulness of the intervention in supporting children’s language and literacy development.

Language and literacy environment

The language and literacy environment in children’s homes is clearly associated with children’s language skills [Citation1–3]. Studies have shown that shared book reading from an early age is related to increased language and cognitive development [Citation1,Citation4,Citation5] as well as increased socioemotional competence [Citation6]. The number of conversational turns between toddler and adult positively correlate with IQ and language skills at age 9–14 years [Citation2]. High levels of parent-reported singing interaction at 6 months are associated with significant advantages in word comprehension in the second year of life [Citation3]. Shared play promotes safe, stable and nurturing relationships, which are important for child development [Citation7]. Increased exposure to play and positive interaction with a caregiver in early childhood has been associated with increased IQ and improved school achievement, as well as decreased symptoms of depression, social inhibition and violent behaviour in adulthood [Citation8].

Parents play an important role in forming children’s early language and literacy environment in the home. Their beliefs about shared reading have been shown to be closely related to parental actions regarding reading in the home [Citation9,Citation10]. Frequent reading habits of parents have been found to correlate with more frequent reading habits [Citation11] and higher ability in speaking and listening, reading and writing [Citation12,Citation13] in their children.

Numerous book-gifting interventions have been established globally to help parents support their children’s early language development by promoting shared reading [Citation14–16]. A meta-analysis by De Bondt et al. showed that book-gifting interventions, both with and without parent instruction, had significant effects on a composite measure of the home literacy environment, including, e.g. frequency of shared book reading and parental interest in reading [Citation17]. Another meta-analysis by Dowdall et al. found that book-sharing interventions that included parent instruction had large effects regarding caregiver book-sharing competence, i.e. the degree to which the caregivers were able to apply the techniques included in the intervention [Citation18]. These meta-analyses showed significant effects regarding children’s expressive and impressive language skill [Citation17,Citation18].

Bookstart is a book-gifting intervention that is introduced to families at health care visits, but also at family centres, at libraries and in their homes [Citation14]. A randomised controlled trial carried out by O’Hare and Connoly [Citation19] showed that participation in Bookstart had a significant positive effect on parent’s attitudes to reading and books. Significantly stronger school results have been found among Bookstart children (n = 41) compared to controls [Citation20].

Let’s Read and Reach Out and Read are book-gifting interventions carried out by paediatricians during well-child care visits, taking from 30 s to about five minutes [Citation21,Citation22]. A population-based clustered randomised trial (n = 630) studying children participating in Let’s Read failed to detect any differences in measures of emergent literacy skills and language at four years of age compared with controls [Citation22]. The general consensus in the literature supports that Reach Out and Read is effective, although the quality of studies varies [Citation23].

The early intervention Språkstart Halland

Språkstart Halland – små barns språkutveckling (Språkstart Halland) is an early language and literacy intervention developed in the Swedish region of Halland in western Sweden in 2018. It targets children 0–3 years, and includes three different gift-packs delivered by library staff to families at home visits. The gift-packs were specially developed to inspire language stimulating activities at the ages 6 months, 11 months and 3 years. The material was developed in cross-professional collaboration between units targeting children’s development and language acquisition, i.e. librarians, speech and language pathologists, child health care staff, and education strategists (Ehde Andersson M., personal communication, November 23, 2023). The gift-packs each include books, a toy and a leaflet with songs and rhymes. Some of the books are complemented with Key Word Signs [Citation24].

The present study focuses on the first two parts of the intervention (6 and 11 months). The third gift had not been distributed during the study period. In the municipality where the study was conducted, the intervention targets all children in the relevant age groups. According to the organisation’s internal documentation, it reaches about 90% of the target population (100–130 children per year) for the first visit. Participant rates also remain high for the second and third visits (Ehde Andersson M., personal communication, 23 November 2023).

The intervention is distributed by library staff called language starters. The occupational backgrounds of language starters can differ; an introduction to the task is given by experienced colleagues. The language starter in the present study is a preschool teacher with many years of experience in the field. A postcard, providing brief information about the intervention and a scheduled time for a home visit, is sent to families with children at 6 months of age. During the visit, parents are invited to share their contact details for a second visit at 11 months. Addresses are obtained from the national population register regarding families with children at 6 months and for new residents with children at 11 months.

The language starter visits the families at their scheduled time for home visits. If needed, the language starter may suggest organizing the visit at the library. During the visit (which usually lasts 30–45 min), families receive the gift-pack and are invited to participate in language-stimulating activities containing hands-on strategies to support the child’s language development. Strategies such as descriptive talk, responsive communication and Key Word Signing are modelled in play-based activities and interactive reading. The language starter demonstrates how to use body language, sounds, gestures, and facial expressions to captivate the attention of the toddler and spark their interest in the activities promoted in the intervention – namely, ‘talk, play, sing, read’ [Citation25]. Families are also invited to activities at the library. Written suggestions of language-stimulating activities using the strategies described above as well as information regarding language development at the current age are provided. The information is available in the 10 most common foreign languages as well as the five Swedish minority languages. Parents are encouraged to talk to the child in their own native language.

Språkstart Halland has previously been evaluated in a student thesis using a small study sample. The results were cautiously positive regarding self-rated frequency of shared reading and effects on children’s language skills, though several measures did not reach significance [Citation26]. Evaluations of early interventions that include book-gifting have mostly focused on the effects on language and literacy environment in terms of shared reading [Citation17–19,Citation27]. Språkstart Halland includes book-gifting, but also explicitly promotes the language and literacy environment in a wider perspective. The purpose of the present study was to examine parents’ experiences of Språkstart Halland and to develop an understanding of their general impressions and thoughts regarding the impact of the intervention.

Materials and methods

To explore the participants’ experiences and gain a deeper understanding of their thoughts and impressions, semi-structured focus group interviews were chosen. Data collection was thought to benefit from a ‘group effect’, insights gained as a result of group interaction [Citation28]. Compared with focus groups, one-on-one interviews can offer more privacy and invite participants to share more personal accounts [Citation29]. Data was analysed using qualitative content analysis with an inductive approach [Citation30].

Participants

The participants (n = 15) consisted of parents of children in a small municipality that can be described as rural industrial, which is home to a large number of foreign-born residents. All participants had participated in at least one Språkstart Halland visit. The language starter in this area, who had had previous contact with all Språkstart participants, aided in selecting possible study participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Participants were selected through purposeful sampling. As far as possible, variation in terms of demographic factors was aimed for (see ). To participate, sufficient Swedish skills were required. This was informally assessed by the language starter and estimated by the participants themselves. An information letter was sent by post to families who had taken part in the intervention. Families were contacted by phone and asked for their participation as well as given the opportunity to ask any questions. A total of 93 families received written information about the study. Among reachable parents, non-participation in the study was attributed to reasons such as family illness, scheduling conflicts, busy family life, and lack of interest to participate.

Table 1. Demographic information, participants.

The mean age of the participants was 33 years (range 24–45). Three of the families had received only the first visit, while 12 had received the first and second visits. The time that had passed from the most recent visit to the time of the interview ranged from about 1 to 19 months. The majority of participants had received the most recent visit no longer than a year ago. The participants’ personal reading habits did not considerably differ from national reading habits [Citation31].

Data collection

Data was mainly gathered in focus group interviews held in September–November 2020. A semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions was developed by the authors in accordance with the aim, based on previous literature. The questions were: (1) What was it like to receive a visit from a language starter? (2) Do you do anything differently at home after the visit? (3) What has Språkstart Halland meant to you? (4) Is there anything that could be done differently? (5) Is there anything else you would like to add? No revision of the interview guide was required during the study. Participants answered a brief background information questionnaire including questions regarding personal reading habits. Interviews were mainly held at a local public library and moderated by the first author, with the assistance of a co-author. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, two of the interviews were held online using a video meeting service. Due to attrition two one-on-one interviews were performed (for participant distribution and interview setting, see ). Interview duration varied between 25 and 70 min. All interviews were audio recorded. After the sixth interview, a majority of the information shared could be recognised from earlier interviews, and further data collection was assumed to add little new information. The data collection was therefore halted at that point.

Table 2. Participant distribution and interview setting.

Data analysis

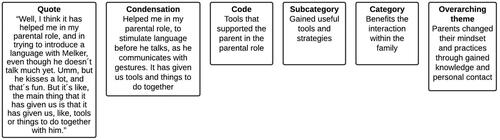

Analysis was carried out by means of qualitative content analysis with an inductive approach [Citation30], using NVivo Pro 2020 [Citation32]. The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by the first author. Transcription (in total 206 pages) was initiated upon completion of the first interview and then carried out continuously after subsequent data collection sessions. The interviews were listened to and read through several times to obtain an overview of the material. One of the audio files was checked for transcription accuracy by the third author. No discrepancies were found. Subsequently, transcripts were segmented into meaning units and condensed [Citation30]. This was carried out by the first author in close contact with co-authors, who double-checked samples of text and occasionally discussed formulations until an agreement was reached. Collaboration between researchers during the analysis strengthened scientific rigour in terms of dependability [Citation33]. Condensed meaning units were then labelled with a code [Citation34]. Codes were inductively sorted into subcategories based on commonality [Citation34]. Subcategories were then sorted into categories based on commonality [Citation33]. Meaning units and codes that deviated from the aim were excluded (15%). Categorisation and subcategorisation were discussed with co-authors until consensus was reached. The analysis included a back-and-forth movement through the described steps, with a later decision sometimes altering earlier parts of the analysis. Finally, the analysis resulted in an overarching theme, running through all included categories. An example of the analytic process from meaning unit to overarching theme is given in . The authors each brought a different knowledge base, pre-understanding and experience to the study and data analysis.

Figure 1. Example from the analytic process of the content analysis.

Findings

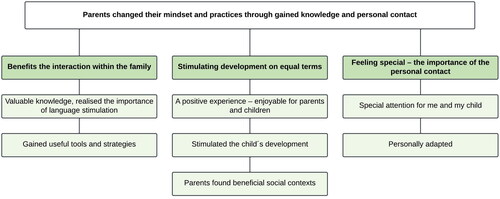

The analysis arrived at three categories, in turn consisting of seven subcategories, and an overarching theme running through the entire material. (see ).

Figure 2. Overview of findings, the overarching theme, categories (n = 3) and subcategories (n = 7) of the result.

Benefits the interaction within the family

This category consisted of two subcategories: (1) Valuable knowledge, realised the importance of language stimulation, and (2) Gained useful tools and strategies.

Valuable knowledge, realised the importance of language stimulation

Parents described gaining knowledge about child development and early language stimulation. The recommendation of shared reading and talking to the child at such a young age was surprising.

Alice: “And above all… that one should start with books that early! I had no idea.”

The visit was described as a push in the right direction. Parents described that the new knowledge led to an awareness regarding early language stimulation and its importance as well as a changed mindset regarding early language stimulation.

Anders: “Yes, there has been a bit of a shift in thinking, so to speak. (…) It’s at this age we shape their future.”

Parents learned about various language-stimulating strategies and realised that the child could benefit from this at such an early age.

Alice: “There were some valuable tips, like one doesn’t think about talking about everyday things at home so that the child can hear.”

Johan: “Exactly, like saying out loud everything you are thinking.”

Alice: “Or talking to the child, you think they are so little, they just lie there.”

Parents new to this knowledge described it as an epiphany.

Selma: “It was like, aha, so that’s how it’s done!”.

Parents with their first child described feeling supported by the recommendations on language stimulation and parenting in general. It was also reported that parents already had knowledge and read and talked to their children prior to the visit. The visit was then perceived as a reminder and eye-opener regarding the importance of early language stimulation. Parents described that the message strengthened and confirmed their previous views.

Parents reported they started to read, sing and talk to the child earlier compared with if they had not received the visit. Language-stimulating activities were reported to be carried out more frequently as well.

Johan: “Well it was more like we tried to read every single day. Or, like, we tried to squeeze it in more often.”

The insights on the importance of language stimulation were described as retained over a year after the visit. Though all parents said they had gained something from the visit, they each remembered different parts of the information. For example, as parents, due to preconceived understandings regarding the aim of the visit, focused a lot on the shared reading, the message of shared play and talk was not as well perceived. Parents who had not perceived this message requested an increased focus on these aspects.

Gained useful tools and strategies

New strategies benefitting the parent-child interaction were acquired. Parents described gaining valuable tools in terms of material and strategies, helping them get started with language-stimulating activities. They described reading, singing and playing with greater involvement, which the child enjoyed. The shared book reading was described to create closeness with the child, compared with screens, which easily became a babysitter. The new shared activities were perceived to strengthen the parental role.

Peter: “Well, I think it has helped me in my parental role, and in trying to introduce a language with Melker, even though he doesn’t talk much yet. Umm, but he kisses a lot, and that’s fun. But it’s like, the main thing that it has given us is that it has given us, like, tools or things to do together with him.”

Parents described that the gift-pack offered a variety of quality material that they would not otherwise have found. The books and toys were highly appreciated by their child and siblings. Receiving the material as a gift and not a loan was appreciated, as the children often handled the books roughly. Parents described their child taking initiative to play with the toys, sing and read the books both alone and together with a parent. The material was well suited for the age, which made a big difference.

Felicia: “We had flipped through books already, but it was great when we got those books, so that we could, well, at his level, you know.”

A generally increased appetite for reading was described. Though it was also described that children showed interest in the material and activities briefly but then quickly turned to something else.

Elsa: “Well, she does seem interested, ‘cause she likes to sit and listen for a while. Then she sees something else that’s interesting, so…. At least we try!”

Parents mentioned they did not read much because the child did not seem interested yet, and that they struggled to sustain the activity and regain the child’s interest. Older siblings were in some cases described to enjoy the material even more. Parents also found it difficult to talk to the child early as the child did not respond verbally.

There were parts of the material that parents felt were hard to assimilate, and a few of them mentioned wanting more from the intervention in order to get started, e.g. Key Word Signs for words that are used more often were requested. It was mentioned that some parts of the material were not liked or used by the child and/or parent. Opinions differed and books that were pointed out by some as less used were mentioned as favourites by others. It was mentioned that parents found the illustrations in one book scary.

Stimulating development on equal terms

This category consisted of three subcategories: (1) A positive experience – enjoyable for parents and children, (2) Stimulated the child’s development, and (3) Parents found beneficial social contexts.

A positive experience – enjoyable for parents and children

Parents described that they had not heard of the intervention before. Upon hearing about it, parents described curiosity, suspicion that the offer was too good to be true, and uncertainty regarding what was going to happen. Clearer information would have been appreciated. Multilingual parents expressed uncertainty regarding whether their Swedish language skills were good enough to be able to be understood during the visit. In hindsight, though, this was not perceived as a problem. The intervention was much appreciated, and special because it was not offered everywhere.

Alice: “I was so surprised, and so happy it existed! For me it has been awesome and a super positive thing.”

Parents enjoyed the meetings, and they could see that the children enjoyed the activities as well. The presentation was described to be inspiring, particularly in terms of the way the language starter carried out language-stimulating activities both at the library and during the home visits. Parents described later trying to recreate the experience with the child.

Parents stressed the value of equality in the intervention. It is free and anyone can participate – no one is left out. All children get the same opportunities to learn and develop, regardless of background and other factors.

Johan: “That’s what I think is almost the best part, it’s that everyone gets some books, so, it doesn’t matter if you’re super poor or super rich, you still get one –“

Alice: “All children get the same opportunities to learn and develop.”

Sofie: “Exactly.”

A hope for the program to continue was expressed.

Stimulated the child’s development

Parents described noticing that the children learned from the material and activities. Words, phrases and communicative gestures were learned from the books and from communication in the reading context. A book featuring animal pictures and brief phrases, such as ‘kiss the cat’, was described to teach and encourage the gesture of kissing.

Nathalie: “The kissing book that arrived when she was 6 months, that’s where she learned to kiss. And now every time she opens the book she kisses all the animals (laughter). She still does that (laughter). She started kissing the dogs around the same time.”

There was also parental description of the child learning from the pictures in the books, and the symbolic understanding growing over time. Siblings with delayed language development were described to benefit from the intervention as well. For example, Key Word Signs were sometimes already used in the home with older siblings, and the gifted material supported this practice.

Multilingual parents reported telling the stories in both languages. The visit and material had helped parents and children learn Swedish together, and subsequently they communicated more also in Swedish.

Petra: “I, too, have this language thing, so it helps me quite a lot, too. I’m not sure that I would have talked as much in Swedish with my daughter as I do now, so it has been a good way to, you know, we learn Swedish a bit together at home (…) I think I would have done it more in Danish without Språkstart.”

Parents found beneficial social contexts

Recommendations on suitable activities to attend with the child helped parents find beneficial social contexts outside the home. Parents described being guided to library activities such as the baby café, which includes group-based language-stimulating activities. Parents reported feeling personally invited to the library to borrow books for their children and themselves. It was reported that the visit gave them courage to leave home to a greater extent. Parents appreciated getting nudged to go out and into new social contexts. The home and library visits were described as appreciated as a social event in a new phase of life, e.g. because loneliness could occur in the new life situation.

Felicia: “Well for me it was a lot like, the thing itself (the intervention, author’s comment), that it happened. Because, well, I had my first child, and suddenly I felt very lonely.”

Parents with a different native language than Swedish described that they appreciated the visit in terms of a context that offered opportunities to practise Swedish, to improve their own language skills and to be able to help their children.

Noor: “I hope to meet Swedish people, so that my language is better. For me, or for my children too. My daughter, Anna, will go first grade, second grade, I need to teach her in Swedish to be better in school.”

Parents described that their improved Swedish skills helped them understand the child better, hence communication between child and parent was facilitated.

Noor: “At preschool they talk Swedish, at home we talk Arabic. There are a lot of differences between languages. When she gets home, if I don’t understand Swedish, I can’t talk to her. There are a lot of words she doesn’t understand in Arabic. I need to translate in Swedish. Språkstart has helped me learn new words, from the books or from Annika (the language starter, authors comment).”

Feeling special – the importance of the personal contact

This category consisted of two subcategories: (1) Special attention for me and my child, and (2) Personally adapted.

Special attention for me and my child

The fact that each family received time and special attention centred around the child’s development, and the parents’ strategies to support it, was described as outstanding and valuable.

Noor: “It’s fun and feels good to meet someone, people come and look at what we do, what we think, what we teach my children. Very fun for me.”

Parents described feeling supported regarding their family situation, e.g. in terms of parenting older siblings and receiving occasional book recommendations on the subject. It was emphasised and appreciated that the child and parent, as well as siblings and others present at the visit, were actively engaged and received due attention and consideration during the meeting.

Alice: “…she approached Mira and showed the books to Mira and, like, talked to my child, even though she was only six months old.”

The fact that someone paid attention to the families’ habits regarding language stimulation was described to challenge parents to initiate and enrich language-stimulating practices.

Parents described that it felt special for the child to receive a gift from someone outside the family, and the gift created recognition for the child in a context outside the home, the library. Parents who had their first child described that they did not have so many things for the child yet. Other parents described having many things for the child already, and the gift was more of a pleasant bonus.

Personally adapted

Parents described the home visit as appreciated because it saved the family the hassle of going somewhere else. They also said it offered a calm, safe learning environment that allowed tailoring the information to fit each respective family.

Selma: “It’s more, well, personal, the home visit.”

Parents explained that as they experienced the child’s reaction to the activities and received individually tailored information, they gained insights into the young child’s ability to respond to and engage with language stimulating stimuli and learn. They said this increased the motivation to keep the activities going after the visit.

Alice: I think she said something about that it was good to sing to the child, didn’t she? Selma: yes, she might have, yes, and talk a lot and- Alice: yeah, ‘cause we got those little nursery rhymes, so we started singing early just because, because you could see that she looked at us when you did those little rhymes.

Parents described appreciating the personal relationship formed with the language starter by receiving special attention regarding the child’s development. The personal traits of the language starter were described to be important. Parents explained that they appreciated that the language starter was reliable, knowledgeable and trustworthy as well as easy going, talkative, inviting and inspiring.

Selma: Annika is very talkative and inviting, and it’s easy to ask her questions, so that you–

Johan: yes, a very easy person to deal with

Selma: yes definitely, and that makes us very positive to it, too’

Overarching theme – Parents changed their mindset and practices through gained knowledge and personal contact

An overarching theme was identified to run through the entire material - Parents changed their mindset and practices through gained knowledge and personal contact. Parents described that their mindset changed as they gained knowledge about the child’s early development and the importance of early language stimulation. Parents realised that the child despite a very young age was already an active learner. In enjoyable interaction with the language starter, parents could experience the child’s reaction to activities that scaffold this development. Parents reported changing their habits regarding language stimulating activities post intervention.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine parents’ experiences of the early literacy intervention Språkstart Halland, and to develop an understanding of their general impressions and thoughts regarding the impact of the intervention. Parents described gaining insights and learning about language stimulation, which resulted in changed attitudes and practices. Similar interventions have demonstrated comparable outcomes [Citation35,Citation36]. According to transformative learning theory, adult learning can be seen as an intersubjective process of communicative learning, of which the goal is mutual agreement [Citation37]. The possibility to meet in the family’s home environment, where the language starter communicates information according to each family’s need, facilitates an even power relationship that enhances learning [Citation37]. When service providers listen responsively and treat clients with respect, they are more likely to be effective in promoting positive change [Citation38]. Parents in the current study reported receiving special attention and forming positive relationships with the language starter, as well as receiving personally adapted recommendations based on their current situation. The appreciation of the time given to each family was emphasised. Spending time is an important component of building relationships between service providers and families [Citation38]. The importance of a personal relationship with the service provider has also been previously reported [Citation39].

Learning takes place in interaction, where personal beliefs, feelings, and values that support decisions to act, are internally assessed [Citation37]. Beliefs about shared reading have been shown to be closely related to parental actions regarding reading in the home [Citation9,Citation10]. Parents’ increased knowledge and changed attitudes regarding early language stimulation are therefore important in relation to children’s home language environment.

Various social and biological factors influence people’s motivation to learn, improve skills and make healthy choices [Citation40]. Memories of a learning experience are linked with the reward received and the emotions felt [Citation40]. Motivation can be supported by short– or long term reward [Citation40]. Parents in the present study described positive emotions related to the visit. The positive experience created short-term motivation to repeat the demonstrated activities. Strengthened knowledge regarding the importance of early language stimulation also increased parents’ motivation towards the long-term reward of strengthening the child’s language skills.

Children have intrinsic motivation to explore and be actively involved in play and to achieve mastery of various tasks [Citation40]. Responsiveness from the caregiver in this exploration is important for the child’s development [Citation41]. The interaction between child and parent is a major active ingredient in the developmental process that builds and strengthens neural connections in the child’s brain [Citation38,Citation42]. Parents in the present study reported that the intervention helped them notice the child’s initiatives and reactions and realise that the child at this early age is already an active learner. Strategies to support and stimulate the child’s learning and development were gained, and parents reported changing their interactional behaviour post intervention. Consistent findings have been reported in previous research [Citation36,Citation43].

As the child shows clear evidence of enjoyment, parents are more motivated to engage in language-stimulating activities such as shared reading [Citation44]. Some of the parents in the present study described that their child did not seem interested, which was often interpreted as not yet being mature enough for the activity. It is then likely that the activity will be postponed [Citation36,Citation44]. It is therefore important to create realistic expectations regarding the shared reading situation, and apply strategies that encourage interest, playfulness and interaction [Citation45]. Promoting language-stimulating strategies can, like the present intervention, also provide options that to some families are more accessible, like child-directed speech [Citation46], shared play and singing [Citation25]. These are all strategies that have been shown to influence child language development [Citation2,Citation3,Citation7,Citation8].

Multilingual parents reported that they communicated more also in Swedish after the intervention. Family literacy programmes with a focus on bilingual language development have the potential to increase children’s early literacy in the mainstream language while promoting home language maintenance [Citation47].

Parents in the present study praised the intervention for giving the same opportunity to everyone. A meta study has shown that early literacy interventions yield positive effects for children’s language development at all socioeconomic levels [Citation18]. Numerous studies show that early literacy interventions produce the greatest gains in groups with the greatest speech, language and communication needs, e.g. in groups with low socio-economic status [Citation1,Citation4,Citation14,Citation48]. Positive outcomes have been identified in children with language impairment as well [Citation49]. It has been claimed that early language development must be a public health priority [Citation50–52]. Support for children’s speech, language, and communication need is needed at different levels. Universal support that targets and benefits all children is important, as is support that targets children exhibiting language weakness and vulnerability [Citation51,Citation53].

Future studies could evaluate the effects on home language and literacy environment beyond measures of shared reading, which is currently dominating in the literature [Citation17–19,Citation27].

Methodological aspects

The present study used content analysis and the following terms of trustworthiness, credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability were considered and used to meet methodological considerations [Citation54].

A limitation of the study was the high attrition rate, which could be attributed to data collection occurring during the pandemic, likely contributing to increased difficulties for participants to engage. The unintentional two-fold design of one-on-one interviews and focus groups served as a form of triangulation that strengthened the credibility [Citation55]. In the two interviews that unintentionally ended up being one-on-one interviews, participants were not able to benefit from the group effect [Citation29,Citation56]. Most of the content, though, was similar across interview types, which indicated strengthened credibility and no considerable loss of information. The online interviews offered a different conversation dynamic than the in-person interviews. Participants were less likely to engage in each other’s stories, which might have affected the information shared. Occasionally, parents with Swedish as a second language seemed to be struggling to understand and fully participate. This may have hindered them from sharing their full experience, which might have affected the credibility of this subgroup [Citation33]. However, all participants assured us that they had nothing more to add.

It is possible that other events (pre or post intervention) influenced parents’ views on language stimulation, especially for parents who received the intervention less recently. These parents might not have remembered all the details regarding the intervention, yet they had the possibility to share how the messages were perceived and retained over time. The majority of participants had received the most recent visit no longer than a year ago at the time of the interview, which strengthens credibility of the findings. However, we do acknowledge that it could be a limitation of present study, that there was a large discrepancy between time for interview and the intervention in some cases.

The intervention is primarily centred around home visits, although visits at the library are also offered if needed. The mode of delivery may influence how the intervention is perceived. In the present study, both home visits and visits held at the library were represented. The variation among participants in mode of delivery of the intervention (home or library visit), and the variation regarding demographic factors such as language background and educational level, provide enough data to cover relevant variation of the studied phenomena [Citation33]. It should also be noted that this variability could create some interpretation challenges.

The decision to exclude participants with limited Swedish skills resulted in excluding families in the target population. This limits transferability of the study to demographically similar samples [Citation55]. However, the study sample was still quite diverse in terms of demographic factors such as language background and educational level, which enhances transferability.

Many parents who participated expressed enthusiasm regarding the intervention. It is possible that parents with neutral or negative attitudes might have been less eager to participate, or that these thoughts were not fully expressed due to group dynamics. This could affect the transferability and external validity of the results [Citation55].

Using a semi-structured question guide for all interviews strengthened the dependability and helped keep the focus on the aim of the study during the interviews [Citation54]. Confirmability was considered by presenting quotes from all focus groups and individual interviews to illustrate the connection between the interview data and the analysis. During the analysis, continuous discussions were held between co-authors to strive for a transparent and reflective analysis [Citation54]. Many similar studies show similar results [Citation17,Citation39,Citation43], which strengthens confirmability [Citation33].

Conclusion

Parents described how the early language and literacy intervention Språkstart Halland changed their mindset regarding early language stimulation and provided new helpful tools benefitting the parent-child interaction. The positive experience from the shared activities during the visit along with knowledge regarding the importance of early language stimulation created motivation to carry out language-stimulating activities according to the received guidance after the visit. The personal relationship with and special attention given by the language starter along with personally adapted guidance was described to be of great importance. Social gains for the parent and child from the meeting itself as well as from the guidance towards social activities at the library were described.

In summary, the results resemble those of earlier similar studies. The applied strategies are in line with current policy recommendations [Citation38]. This suggests usefulness of the intervention in increasing learning opportunities in the home environment.

Future directions

The findings suggest potential areas for further refinement in the design of the intervention. Specifically, it appears crucial to enhance certain aspects, including the provision of comprehensive information to parents in advance. Additionally, there is a need to underscore the significance of presenting examples of activities beyond shared book-reading.

Future studies could explore experiences of parents who have not yet acquired the majority language, as well as reach out to a larger number of participants, e.g. by means of a questionnaire. A wide focus on language and literacy environment is preferrable. The programme’s effect on children’s language skills could also be explored.

Ethical approval

The regional ethical review board in Uppsala granted ethical approval of the study (Dnr 2020-01105). All participants gave their informed written consent. The participants were informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study without explanation at any point. The data was handled confidentially. Names were replaced with pseudonyms.

Authors’ contribution

The authors contributed equally to the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Shahaeian A, Wang C, Tucker-Drob E, et al. Early shared reading, socioeconomic status, and children’s cognitive and school competencies: six years of longitudinal evidence. Sci Stud Read. 2018;22(6):485–502. doi: 10.1080/10888438.2018.1482901.

- Gilkerson J, Richards JA, Warren SF, et al. Language experience in the second year of life and language outcomes in late childhood. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20174276. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4276.

- Franco F, Suttora C, Spinelli M, et al. Singing to infants matters: early singing interactions affect musical preferences and facilitate vocabulary building. J Child Lang. 2022;49(3):552–577. doi: 10.1017/s0305000921000167.

- Raikes H, Alexander Pan B, Luze G, et al. Mother-child bookreading in low-income families: correlates and outcomes during the first three years of life. Child Dev. 2006;77(4):924–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00911.x.

- Flack ZM, Field AP, Horst JS. The effects of shared storybook reading on word learning: a meta-analysis. Dev Psychol. 2018;54(7):1334–1346. doi: 10.1037/dev0000512.

- O’Farrelly C, Doyle O, Victory G, et al. Shared reading in infancy and later development: evidence from an early intervention. Journal Appl Dev Psychol. 2018;54:69–83. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.12.001.

- Yogman M, Garner A, Hutchinson J, et al. The power of play: a pediatric role in enhancing development in young children. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3):e20182058. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2058.

- Walker SP, Chang SM, Vera-Hernández M, et al. Early childhood stimulation benefits adult competence and reduces violent behavior. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):849–857. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2231.

- Debaryshe BD, Binder JC. Development of an instrument for measuring parental beliefs about reading aloud to young children. Percept Mot Skills. 1994;78(3_suppl):1303–1311. doi: 10.2466/pms.1994.78.3c.1303.

- Iflazoglu A, Feyza N, Deretarla E. Investigation of parents’ early literacy beliefs in the context of Turkey through the parent reading belief inventory (PRBI). European J ED Res. 2018;7(4):985–997. doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.7.4.985.

- Clark C, Hawkins L. Young people’s reading: the importance of the home environment and family support: more findings from our national survey. London: National Literacy Trust; 2010.

- Hartas D. Inequality and the home learning environment: predictions about seven-year-olds’ language and literacy. British Educational Res J. 2012;38(5):859–879. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2011.588315.

- Van Bergen E, Van Zuijen T, Bishop D, et al. Why are home literacy environment and children’s reading skills associated? What parental skills reveal. Read Res Q. 2017;52(2):147–160. doi: 10.1002/rrq.160.

- Adenfelt M, Segerström A, Strandberg R. Bokstart i världen: metoder och forskning om bokgåvoprogram för små barn och deras familjer. [Bookstart worldwide: methods and research on book-gifting programs for young children and their families.] Stockholm: Statens Kulturråd; 2020. Swedish.

- Egan SM, Hoyne C, Moloney M. Shared book reading with infants: a review of international and national baby book gifting schemes. J Early Child Studies. 2020;13(1):49–64.

- European Commission. Eu high level group of experts on literacy: final report. Luxembourg: European Union; 2012. doi: 10.2766/34382.

- De Bondt M, Willenberg IA, Bus AG. Do book giveaway programs promote the home literacy environment and children’s literacy-related behavior and skills? Rev Educ Res. 2020;90(3):349–375. doi: 10.3102/0034654320922140.

- Dowdall N, Melendez-Torres GJ, Murray L, et al. Shared picture book reading interventions for child language development: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Dev. 2020;91(2):e383–e399. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13225.

- O’Hare L, Connolly P. A cluster randomised controlled trial of “bookstart”: a book gifting programme. J Child Serv. 2014;9(1):18–30. doi: 10.1108/JCS-05-2013-0021.

- Wade B, Moore M. A sure start with books. Early Years. 2000;20(2):39–46. doi: 10.1080/0957514000200205.

- Zuckerman B, Khandekar A. Reach out and read: evidence based approach to promoting early child development. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010; 22(4):539–544. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833a4673.

- Goldfeld S, Quach J, Nicholls R, et al. Four-year-old outcomes of a universal Infant-Toddler shared reading intervention: the let’s read trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(11):1045–1052. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1099.

- Yeager Pelatti C, Pentimonti JM, Justice LM. Methodological review of the quality of reach out and read. Clin Pediatr . 2014;53(4):343–350. doi: 10.1177/0009922813507995.

- Cologon K, Mevawalla Z. Increasing inclusion in early childhood: key word sign as a communication partner intervention. Int J Incl Educ. 2018;22(8):902–920. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2017.1412515.

- Språkstart Halland – små barns språkutveckling. [Internet] Region Halland: Region Halland; 2023 [cited 2023 Sept 22]. Available from: https://www.regionhalland.se/kultur/kulturbarnunga/sprakstart/.

- Lundqvist J, Almqvist Tangen J. En utvärdering av Språkstart Halland - hur en regional och kommunal insats med inslag av gemensam bokläsning kan främja förskolebarns språkutveckling [An evaluation of Språkstart Halland - how a regional and municipal initiative involving shared reading can promote language development in preschool children] [Masters’ thesis]. Lund: Lund University; 2020. Swedish.

- Booktrust. Bookstart national impact evaluation. Leeds: Booktrust;2009.

- MacPherson I, McKie L. Qualitative research in programme evaluation. In: Bourgeault I, Dingwall R, De Vries R, editors. The SAGE handbook of qualitative methods in health research; 2010. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. p. 454–477.

- Barbour RS. Focus groups. In: Bourgeault I, Dingwall R, Vries RD, editors. The SAGE handbook of qualitative methods in health research. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2010. p. 327–352.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Hellingwerf K, Facht U. Textmedier. In: Ohlsson J, editor. The Media Barometer 2020. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, Nordicom - Nordic Information Centre for Media and Communication Research; 2021. p.76–79. doi: 10.48335/9789188855497.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo (released in march 2020). Alfasoft; 2020. Available from: https://alfasoft.com/sv/programvara/statistik-och-dataanalys/qda-kvalitativ-dataanalys/nvivo/.

- Graneheim UH, Lindgren BM, Lundman B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: a discussion paper. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;56:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002.

- Lindgren B-M, Lundman B, Graneheim UH. Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;108:103632. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103632.

- Bookstart. (2010). 2009/10 ‘A Social Return on Investment (SROI) Analysis’: prepared for Book- trust by Just Economics LLP. Leeds, England: Booktrust.

- Bleses D, Andersen MK. Kan bogstart gøre en forskel? En undersøgelse af bogstarts potentiale som led i det forebyggende arbejde for at understøtte sprogtilegnelsen hos børn i udsatte boligområder. [Can bookstart make a difference? An investigation into the potential of bookstart as part of preventive efforts to support language acquisition in children in disadvantaged residential areas]. Odense: Center for Børnesprog, Syddansk Universitet; 2011. Danish.

- Mezirow J. Transformative learning as discourse. J Transform Educ. 2003;1(1):58–63. doi: 10.1177/1541344603252172.

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Three principles to improve outcomes for children and families: 2021 update. Cambridge (MA): Harward University; 2021.

- Espersen HH. Evaluering af samarbejdet i projekt bogstart. En opsøgende biblioteksindsats over for familier med førskolebørn i udsatte boligområder [Evaluation of the collaboration in project bookstart. An outreach library initiative for families with preschool children in disadvantaged housing areas]. Copenhagen: KORA: Det Nationale Institut for Kommuners og Regioners Analyse og Forskning; 2016. Danish.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Understanding motivation: building the brain architecture that supports learning, health, and community participation. : working Paper No. 14. Cambridge (MA): Harward University; 2018.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Young children develop in an environment of relationships., Working Paper 1. Cambridge (MA): Harward University; 2004.

- Romeo RR, Leonard JA, Grotzinger HM, et al. Neuroplasticity associated with changes in conversational turn-taking following a family-based intervention. Dev Cogn Neurosci; 2021;49:100967.

- Yaun J, Bach M, Bakke J, et al. Evaluation of a language and literacy enhancement program. Clin Pediatr 2019;58(1):100–109. doi: 10.1177/000992281880946.

- Preece J, Levy R. Understanding the barriers and motivations to shared reading with young children: the role of enjoyment and feedback. J Early Child Lit. 2020;20(4):631–654. doi: 10.1177/1468798418779216.

- Towell JL, Bartram L, Morrow S, et al. Reading to babies: exploring the beginnings of literacy. J Early Child Lit. 2019;21(3):321–337. doi: 10.1177/1468798419846199.

- Bleses D, Höjen A. Bogstart endelig rapport [Bogstart final report]. [Aarhus]: Aarhus University; 2015. Danish.

- Anderson J, Anderson A, Sadiq A. Family literacy programmes and young children’s language and literacy development: paying attention to families’ home language. Early Child Dev Care. 2017;187(3-4):644–654. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2016.1211119.

- Bleses D, Dale PS, Justice L, et al. Sustained effects of an early childhood language and literacy intervention through second grade: longitudinal findings of the SPELL trial in Denmark. PLOS One. 2021;16(10):e0258287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258287.

- Marulis LM, Neuman SB. How vocabulary interventions affect young children at risk: a meta-analytic review. J Res EducEff. 2013;6(3):223–262. doi: 10.1080/19345747.2012.755591.

- Beard A. Speech, language and communication: a public health issue across the lifecourse. Paediatr Child Health. 2018;28(3):126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.paed.2017.12.004.

- Law J, Levickis P. Early language development must be a public health priority. Health Visit. 2018;6(12):586–589. doi: 10.12968/johv.2018.6.12.586.

- Fäldt A. Targeting toddlers’ communication difficulties at the Swedish child health services - a public health perspective [dissertation]. Uppsala: Uppsala University; 2020.

- Ebbels SH, McCartney E, Slonims V, et al. Evidence-based pathways to intervention for children with language disorders. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2019;54(1):3–19. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12387.

- Polit DF. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. Eleventh edition Beck CT, editor. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2021.

- Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–488. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05627-6.

- Tracy SJ. Interview practice embodied, mediated, and focus-group approaches Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact., First Edition, Chichester (UK): Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2013. p. 157–182.