ABSTRACT

Background: Although extended work activity is often associated with active and healthy ageing, it meets with a polarized response. Studying workers’ lived experience may provide important insights into their motives for working beyond typical retirement age. Objective: This systematic review aims to explore why people who could retire continue to work and applies the dimensions of doing, being, becoming, and belonging to describe prolonged participation in work. Methods: Our search strategy followed the guidelines of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD, 2009). Original studies were identified from databases CINAHL, Web of Science, Business Source Premier, ERIC, and ProQuest. Data were analyzed from the perspective of doing, being, becoming, belonging. A thematic synthesis was applied to summarize key motives. Results: Eleven qualitative studies met the inclusion criteria and achieved the quality criteria of the The Qualitative Assessment Research Instrument. Eight motives were identified that were associated with extrinsic and intrinsic motivational factors. Health was a theme of salience and was both a prerequisite for work and an important motivator in itself. The dimensions of doing, being, becoming, belonging emerged in the description of workers’ motives and formed an interwoven selection of motives that included achievement, positive relationships, helping others, and enjoying work. Conclusion: Retirement-aged workers appear to be a poorly represented population in the scientific literature on work motives. The main findings indicate that workers who prolong labour activity experience work as much more than the act of ‘doing’ or acquiring additional financial resources. This urges us to include the dimensions of ‘being, becoming, belonging’ into contemporary age management.

背景:虽然工作活动延长通常与积极和健康的变老相关,但它会遇到两极分化的反应。研究工人的生活经历可能会为他们在典型退休年龄后工作的动机提供重要的见解。目的:本系统评价旨在探讨为什么可以退休的人会继续工作,并应用做、存在、成为和归属的维度来描述工作参与延长。方法:我们的搜索策略遵循审查与传播中心的指导方针(CRD, 2009)。初始研究得自数据库 CINAHL、Web of Science、Business Source Premier、ERIC 和 ProQuest。从做、存在、成为、归属的角度分析数据。应用主题综合来总结关键动机。结果:11 项定性研究符合纳入标准,并符合定性评估研究工具的质量标准。确定了与外在和内在动机因素相关的八种动机。健康是一个突出的主题,它既是工作的先决条件,本身也是一个重要的动力。做、存在、成为、归属等维度出现在对工人动机的描述中,并形成了一个相互交织的动机选择,包括成就、积极的人际关系、帮助他人和享受工作。结论:在关于工作动机的科学文献中,退休年龄工人似乎是一个代表得不够的人群。主要研究结果表明,延长劳动活动的工人比“做”或获得额外经济资源的行为工作得更多。这促使我们将“存在、成为、归属”的维度纳入当代年龄管理。

Contexte : Bien que l'activité professionnelle prolongée soit souvent associée à un vieillissement actif et sain, elle suscite des réactions polarisées. L'étude de l'expérience vécue des travailleurs peut fournir des informations importantes sur les raisons qui les poussent à travailler au-delà de l'âge typique de la retraite. Objectif : Cette revue systématique vise à explorer les raisons pour lesquelles les personnes qui pourraient prendre leur retraite continuent à travailler et applique les dimensions de faire, être, devenir et appartenir pour décrire la participation prolongée au travail. Méthodes : Notre stratégie de recherche a suivi les directives du Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD, 2009). Des études originales ont été identifiées dans les bases de données CINAHL, Web of Science, Business Source Premier, ERIC et ProQuest. Les données ont été analysées du point de vue du faire, de l'être, du devenir et de l’appartenir. Une synthèse thématique a été appliquée pour résumer les principaux motifs. Résultats : Onze études qualitatives ont satisfait aux critères d'inclusion et aux critères de qualité du Qualitative Assessment Research Instrument. Huit motifs ont été identifiés, associés à des facteurs de motivation extrinsèques et intrinsèques. La santé était un thème saillant et constituait à la fois une condition préalable au travail et un important facteur de motivation en soi. Les dimensions du faire, de l'être, du devenir et de l'appartenir sont apparues dans la description des motifs des travailleurs et ont formé une sélection de motifs entrelacés comprenant l’accomplissement, les relations positives, l'aide aux autres et le plaisir du travail. Conclusion : Les travailleurs à l'âge de la retraite semblent être une population peu représentée dans la littérature scientifique sur les motifs de travail. Les principaux résultats indiquent que les travailleurs qui prolongent leur activité professionnelle considèrent que le travail est bien plus que l'acte de "faire" ou que l’acquisition de ressources financières supplémentaires. Cela nous incite à inclure les dimensions "être, devenir, appartenir" dans la gestion contemporaine des âges.

Antecedentes: aunque la prolongación de la actividad laboral a menudo se asocia con un envejecimiento activo y saludable, genera una respuesta polarizada. El estudio de las vivencias experimentadas por trabajadores puede aportar importantes conocimientos sobre sus motivos para trabajar más allá de la edad típica de jubilación. Objetivo: aplicando las dimensiones de hacer, ser, llegar a ser y pertenecer para describir la participación prolongada en el trabajo, esta revisión sistemática pretende explorar por qué las personas que podrían jubilarse a determinada edad siguen trabajando. Métodos: nuestra estrategia de búsqueda siguió las directrices del Centro de Revisión y Difusión (CRD, 2009). Se identificaron estudios originales en varias bases de datos: CINAHL, Web of Science, Business Source Premier, ERIC y ProQuest. Los datos encontrados se analizaron desde la perspectiva del hacer, ser, llegar a ser y pertenecer, aplicándose una síntesis temática para resumir los motivos clave. Resultados: once estudios cualitativos cumplieron los criterios de inclusión y de calidad establecidos por el Instrumento de Investigación de Evaluación Cualitativa. En estos se identificaron ocho temas asociados a factores motivacionales extrínsecos e intrínsecos. Un tema destacado fue la salud, que operó, a la vez, como un prerrequisito para el trabajo y como un importante motivador en sí mismo. En la descripción de los motivos de los trabajadores se identificaron las dimensiones de hacer, ser, llegar a ser y pertenecer, las cuales formaron un entramado de motivos que incluía el logro, las relaciones positivas, la ayuda a los demás y el disfrute del trabajo. Conclusión: los trabajadores en edad de jubilarse parecen ser una población poco representada en la literatura científica sobre los motivos laborales. Los principales hallazgos indican que los trabajadores que prolongan la actividad laboral experimentan el trabajo como algo que va mucho más allá del acto de “hacer” o adquirir recursos financieros adicionales. Esto insta a incluir las dimensiones de ser, llegar a ser, pertenecer en la gestión contemporánea de la edad.

The rise in the old-age dependency ratio has led countries around the world to encourage prolonged work participation (Arnott & Casscells, Citation2003; Bovenberg, Citation2003; Chand, Citation2018; Eurostat, Citation2020; Heylen & Van de Kerckhove, Citation2019). To promote work past typical retirement age and alleviate the pressure on public finances, older workers and their employers are offered various incentives, mostly in the form of financial benefits (Heylen & Van de Kerckhove, Citation2019). Other common strategies include raising the official retirement age and lowering the pension for early exit from the labour market (Krekula & Vickerstaff, Citation2020). Furthermore, extended work participation has often been associated with the concepts of ‘active ageing’, ‘productive ageing’ and ‘successful ageing’, underpinning a narrative about older people remaining professionally active for as long as possible (Del Barrio et al., Citation2018; Ehni et al., Citation2018). Since these concepts imply and locate a certain responsibility for continuous participation with the individual, the World Health Organization (WHO) recently replaced ‘active ageing’ with ‘healthy ageing’. This conceptual change recognizes the role of society and environmental factors in enabling older people to remain active in a way they value (Rudnicka et al., Citation2020).

Research has demonstrated the benefits of prolonged work participation on multiple levels, including increased independence, preserved routines, better health, and financial stability (Cole & Hollis-Sawyer, Citation2020; Wolverson & Hunt, Citation2015). On the other hand, ageism and negative stereotypes towards older workers remain widespread, limiting their opportunities in the labour market (Čič & Žižek, Citation2017; Cole & Hollis-Sawyer, Citation2020; Fasbender & Wang, Citation2017; Finkelstein et al., Citation2015; Harris et al., Citation2018; Posthuma & Campion, Citation2009). Intergenerational tensions, expressed in the opinion that older workers should step back in favour of the younger generation, are also not uncommon (Björklund Carlstedt et al., Citation2018) and can intensify in the event of an economic crisis when older workers are more likely to be forced into early retirement due to high unemployment rates (Coile & Levine, Citation2011; Phillipson, Citation2019). People who reach the statutory retirement age might, therefore, face an inner conflict when deciding to postpone retirement, juxtaposing their motives and personal preferences against prejudice and societal expectations.

The age at which people get access to a full pension and could arguably become more inclined to withdraw from the labour market differs significantly between countries, ranging from 58 to 67 years in most member states of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), with an average of 63.5 years for women and 64.2 years for men (OECD, Citation2019). There appear to be significant differences in the employees’ intentions to continue working past typical retirement age. For instance, in Malta, less than 3% of women would like to work for as long as possible. In contrast, more than 40% of men would do so in Latvia and Estonia (Eurofound, Citation2017). Furthermore, workers’ opinion about what age they would like to work until often does not match the statutory pension age in that country. In the Nordic countries, where the statutory retirement age is one of the highest in the world, the workers would like to retire on average a year earlier than stipulated. More incongruency has been detected in Cyprus, Greece, Slovenia, and Poland, where workers would like to work between 5 and 7 years less than required (Eurofound, Citation2017).

While the phenomenon of extended working life is complex, policies and initiatives have often focused on workers’ chronological age and health, as well as the economic consequences of early exit from the labor market, somewhat neglecting other aspects of people’s lived experience and the context of their work-related decisions (Nilsson, Citation2016). Moreover, policymakers may overlook the fact that retirement-aged workers are a very heterogenous group, whose decisions are driven by different motives. For instance, some choose to continue working because they enjoy it, while others are forced to work beyond retirement due to economic hardship or caregiving responsibilities (Newton & Ottley, Citation2020). Little attention has also been given to higher-level motives and motivational self-transcendence that may develop late in one’s career (Henning et al., Citation2019), with current focus primarily on the financial sustainability (which should not be ignored). An in-depth understanding of an individual’s motives is needed if workers are to be supported and empowered in their decisions to continue working past typical retirement age, creating a meaningful approach as opposed to applying a standardized, one-size-fits-all tactic (Flynn, Citation2010; Kooij et al., Citation2008; Nilsson, Citation2016, Citation2020).

It has been argued that achieving full understanding of people’s purposeful and meaningful engagement in everyday occupations requires acknowledgement of the dimensions of doing, being, becoming, and belonging, and their interrelatedness with occupation and experience as described within occupational science (Hitch et al., Citation2014; Wilcock, Citation2006). Doing is the visible quality of an occupation that can usually be observed, being links with people’s sense of self and how they experience an occupation, becoming is a process of growth that encompasses development through engagement in occupation, and belonging describes people’s interpersonal relationships and sense of sharing their occupations and their meaning with others (Hitch et al., Citation2014; Hitch & Pepin, Citation2021; Wilcock, Citation2006). These dimensions are usually explored through a qualitative approach that considers the existence of multiple realities and looks at people’s understanding and interpretation of daily reality (Creswell & Poth, Citation2017).

The aim of our study was to synthesize qualitative studies that have described the motives of retirement-aged workers from their own perspective. For this study, retirement-aged workers were defined as people who met the statutory retirement age applicable in their respective country contexts and continued to work even though they are entitled to a pension (state or private) or superannuation. The utilized definition of retirement was chosen because it includes the economic perspective of retirement, and views retirement as a life cycle event that typically involves a pension that (to some extent) replaces an income from employment (Maestas & Zissimopoulos, Citation2010). However, monetary aspects can also be the motive behind extended working life due to incongruency between salary and pension (Cole & Hollis-Sawyer, Citation2020). Receiving pension/retirement income and not participating in the labour force are only two possible measures of retirement. There are several other operationalizations of retirement, including reduction in hours worked, exit from one’s main employer, change of career later in life, and self-assessed retirement (Denton & Spencer, Citation2009). The research questions connected with our systematic review were: 1) Why do retirement-aged workers continue working? and 2) How are motives for prolonged work participation related to the dimensions of doing, being, becoming, belonging? A preliminary search for previous literature reviews on the topic aligning to the same concepts was conducted and no other sources were identified that specifically explored the workers’ perspective.

Methods

Search methods

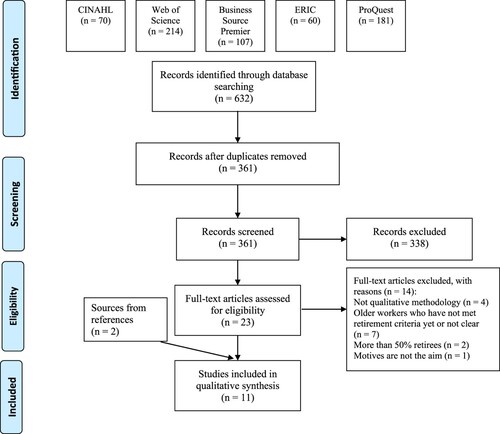

The guidelines of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD, Citation2009) were used to conduct a qualitative systematic literature review, which has been described as a “method for integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies. It looks for ‘themes’ or ‘constructs’ that lie in or across individual qualitative studies” (Grant & Booth, Citation2009, p. 94). In January and February 2021, we searched five databases relevant to the phenomenon of the study. Since our topic requires a multidisciplinary approach, the databases reflected different perspectives, namely healthcare (CINAHL), social sciences (ProQuest), economy and management (Business Source Premier) and education (ERIC). Web of Science was also used as a general multidisciplinary database.

The keywords chosen for the search reflected the three main concepts: retirement-aged worker, motive, worker’s perspective. The search included multiple term synonyms of the main search keyword groups using Boolean operators (AND, OR) and wildcards (). Although we were interested specifically in retirement-aged workers, we also included keywords connected to the words ‘older worker’ and ‘bridge worker’, such as senior worker, older employee, and bridge job. This decision was made after the initial search revealed that some studies did not make a clear distinction between these expressions and could use the term older worker or bridge worker (and related words) to refer to retirement-aged employees. With regard to the concept ‘motive’, we identified most frequently recurring key terms related to this concept, such as reward and incentive. Finally, the search strategy for ‘worker’s perspective’ was based on the knowledge that people’s perspectives are usually represented in qualitative articles studying people’s experience; therefore, search terms related to qualitative methodology and experience were chosen. We adopted a comprehensive search strategy in order not to miss relevant articles.

Table 1. Keywords used in the search strategy

Inclusion and exclusion criteria followed the PICO review protocol for qualitative studies (participants, phenomena of interest, context, type of studies) (Munn et al., Citation2018) and are presented in . In most cases, we were able to establish from the study if the article met the inclusion criteria. For one study, we contacted the authors to clarify the characteristics of the sample and local regulations. Since we wanted to access data from original qualitative research, gray literature was not included. There was no year limitation for the publications. In total, we identified 361 studies after duplicates were removed and the filters for language and type of publication (i.e., article) were applied. The search strategy was documented for every database and presented in the search matrix (available on request). Search results were saved in a reference management software Zotero for identification of duplicates and further analysis.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All original studies were first screened by title (n = 361). In this way, 200 studies were excluded. The abstracts of the remaining 161 articles were read and carefully examined against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Many of these articles did not fit the purpose of our study from a methodological or content perspective and were therefore excluded (n = 138). Twenty-three articles remained and were read in full. Nine articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis. In addition, the references in the original studies selected for inclusion were searched manually to identify additional sources relevant to the review (CRD, Citation2009). Two sources were found in this way, bringing the total number of articles to 11 (see for search strategy and inclusion). The search was repeated in June 2021 and limited to publications from year 2021; however, we did not identify any new studies that would meet the inclusion criteria.

Methodological quality assessment

The original studies chosen for the review (n = 11) were screened using the critical appraisal tool for qualitative studies developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), also known as The Qualitative Assessment Research Instrument (QUARI) (JBI, Citation2014). QUARI consists of 10 evaluation criteria that are applied to each article to provide a score. We decided that studies achieving less than half of the quality criteria would be excluded from the review in order to sustain best quality in evidence chosen for systematic review analysis (CRD, Citation2009). However, all selected articles achieved a score of 6 out of 10 or higher, therefore, none were excluded due to methodological weaknesses.

Data extraction and synthesis

All selected articles were added to the data matrix that collated and summarized the results according to the research questions and included the following items: Author(s) and Year, Objective, Participants, Context, and Key Findings. The findings were analyzed from the perspective of doing, being, becoming, belonging and any presence of these concepts was noted for each article ().

Table 3. Data matrix from selected articles

Since the focus of the review was on the experiences of workers, a thematic synthesis was chosen to further examine the data. It has been argued that thematic synthesis can be an appropriate method within qualitative systematic reviews that aim to summarize key issues relevant to the review while trying not to de-contextualize the data (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). The data and key concepts relevant to our study were found in the Results and Discussion sections, therefore, those sections in each article were read carefully. We extracted the relevant data connected to the workers’ motives. We then applied thematic synthesis that was based on the three-stage analysis process presented by Thomas and Harden (Citation2008). The process involved line by line coding of text from the primary studies. In this way, 67 free codes that pertained to work motives were identified. These codes were summarized into 12 descriptive themes. In the third step, we revealed eight themes that represented eight key motives that constituted our results. The first author completed the analysis, with the aid of computer software Atlas.ti, version 9, which helped with data management and organization of codes. The software facilitated the analytical approach; however, the process of creating codes, merging codes into homogeneous groups, and identifying themes was performed by the researcher. To increase methodological rigour, there was an ongoing critical discussion among all authors about the selected articles and analysis that involved juxtaposing different perspectives and exploring alternative interpretations.

Results

Eleven qualitative studies were included in the final analysis. Ten of the studies were conducted in seven countries: three in the United States, two in Slovenia, and one in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Sweden, Australia, and Iran. The final study was transnational and included professionals from Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Six studies included different professional groups; however, two studies included only nurses, two included only academics, and one focused on the fashion design industry. In five of the studies, it was clear that all the participants continued working in their career employment. In the other six, it was either not specified (n = 2) or some of the participants changed their occupational categories after meeting the retirement criteria (n = 4). The participants’ ages ranged from 50 years to 91 years, with the majority of the articles (n = 9) including people aged 62 or older. Six studies included only workers over 65 and two studies only workers who were 70 or older.

The dimensions of doing, being, becoming, and belonging all featured in the description of workers’ motives (). Doing was often connected with engagement in activities (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Nobahar et al., Citation2015), having something to do (Fraser et al., Citation2009; Hovbrandt et al., Citation2019), maintaining routines (Sewdas et al., Citation2017), and exercising the body and mind (Friedrich et al., Citation2011; Grah et al., Citation2019). Being could be understood as a sense of work-related identity (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Hutchings et al., Citation2020), having a role such as a teacher/mentor or an expert (Friedrich et al., Citation2011), and having a purpose in life (Fraser et al., Citation2009; Hovbrandt et al., Citation2019; Sewdas et al., Citation2017). Becoming featured in a wish for continuous professional development (Dorfman, Citation2000; Friedrich et al., Citation2011), and learning and growth (Grah et al., Citation2019; Ulrich & Brott, Citation2005). Finally, the belonging dimension was recognized in a sense of belonging to a certain work community or an organization (Fraser et al., Citation2009; Friedrich et al., Citation2011; Hovbrandt et al., Citation2019; Hutchings et al., Citation2020) and a wish to contribute to a greater good (Nobahar et al., Citation2015; Reynolds et al., 2015).

Findings of thematic synthesis

Eight main themes were developed through the analysis, describing different motives for workers’ extended engagement in the labor market. These motives were: Maintaining health, Finances, Achievement and growth, Positive relationships, Helping others and society, Enjoying work, Purpose in life, and Keeping familiar patterns. The identified motives were found across several studies, suggesting a level of agreement between different contexts. includes each motive as a theme from the analysis and provides a definition. An exploratory association with dimensions of doing, being, becoming, and belonging is also provided for each motive, most motives exhibiting an overlap of dimensions.

Table 4. Synthesis of motives for prolonged work activity from the workers’ perspective

Maintaining health was mentioned by participants in almost all studies, being a salient theme across all the included studies. Health could take on different meanings in the workers’ narratives. For instance, in order to continue working it was important to feel healthy enough (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Grah et al., Citation2019; Hovbrandt et al., Citation2019; Sewdas et al., Citation2017; Ulrich & Brott, Citation2005). Some workers continued working but reduced their hours due to health problems (Hutchings et al., Citation2020). Flexible work arrangements were crucial in deciding to continue working (Fraser et al., Citation2009; Nobahar et al., Citation2015; Sewdas et al., Citation2017). On the other hand, work was often perceived as a way to maintain health in old age, both physically and mentally, prompting the participants to prolong their work participation in order to preserve good health and vitality (Fraser et al., Citation2009; Friedrich et al., Citation2011; Nobahar et al., Citation2015). Reynolds et al. (Citation2012) also indicated that the motivation to continue working was to maintain a sense of youthfulness. An unexpected finding in one of the studies was represented by a choice of continued work, despite poor health, because the person assessed that their disability would prevent them from having an active retirement with meaningful occupations (Dorfman, Citation2000).

Finances were mentioned by participants in almost all studies. Some workers experienced financial insecurities (Nobahar et al., Citation2015) or had other needs and obligations connected to material resources; for instance, they wanted a better lifestyle (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020) or had to support another family member (Reynolds et al., Citation2012). On the other hand, money was not identified as the most important or only factor in the workers’ decision to extend their working lives. In fact, some of the participants in the identified studies rejected the financial motive altogether (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Grah et al., Citation2019) or emphasized that money was less important than other motives for continued work (Hovbrandt et al., Citation2019).

Achievement and growth were described as motives in many of the included studies (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Fraser et al., Citation2009; Friedrich et al., Citation2011; Grah et al., Citation2019; Hovbrandt et al., Citation2019; Hutchings et al., Citation2020; Reynolds et al., Citation2012; Sewdas et al., Citation2017; Ulrich & Brott, Citation2005). This theme included the concept of autonomy, described as being able to continue working yet stop at any time, and having control over what one does, which seemed to be an important motivating factor for many of the participants and contributed to their sense of achievement. The theme also included various aspects of identity that were associated with work (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Fraser et al., Citation2009; Grah et al., Citation2019; Hovbrandt et al., Citation2019) and with being an expert in a particular field (Friedrich et al., Citation2011; Hutchings et al., Citation2020).

Positive relationships were often cited as a reason to continue working (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Dorfman, Citation2000; Fraser et al., Citation2009; Friedrich et al., Citation2011; Hovbrandt et al., Citation2019; Hutchings et al., Citation2020; Nobahar et al., Citation2015; Sewdas et al., Citation2017; Ulrich & Brott, Citation2005). Workers considered both their relationships at work (with co-workers and supervisors) as well as relationships outside of work. For instance, some continued to work in order to synchronize the timing of their retirement with that of their spouse (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Hutchings et al., Citation2020).

Helping others and society were mentioned as important motivations to work beyond retirement age as well (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Dorfman, Citation2000; Grah et al., Citation2019; Fraser et al., Citation2009; Friedrich et al., Citation2011; Hutchings et al., Citation2020; Nobahar et al., Citation2015; Ulrich & Brott, Citation2005). Workers experienced pleasure in passing on their knowledge (Dorfman, Citation2000; Grah et al., Citation2019; Friedrich et al., Citation2011; Ulrich & Brott, Citation2005) and giving back to society in the latter part of their careers (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Hutchings et al., Citation2020; Nobahar et al., Citation2015).

Enjoying work was often mentioned as an intrinsic motivator, with work itself being a reward (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Dorfman, Citation2000; Fraser et al., Citation2009; Friedrich et al., Citation2011; Hovbrandt et al., Citation2019; Hutchings et al., Citation2020; Ulrich & Brott, Citation2005). Some occupations were ranked as particularly enjoyable, such as teaching and research (Dorfman, Citation2000; Grah et al., Citation2019). Some also experienced a more balanced life overall, especially if they reduced their work hours, which helped them enjoy work more than before, when life was dominated by work obligations (Hovbrandt et al., Citation2019; Hutchings et al., Citation2020; Ulrich & Brott, Citation2005).

Purpose in life was also described as a motive for delayed retirement in some of the reviewed studies (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Dorfman, Citation2000; Fraser et al., Citation2009; Hovbrandt et al., Citation2019; Sewdas et al., Citation2017; Ulrich & Brott, Citation2005). Some participants described their work as a vocation and source of self-actualization (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Grah et al., Citation2019). Work could define people in very powerful ways, as described in the study by Grah et al. (Citation2019), in which the participant articulated that without work, she might cease to exist.

Keeping familiar patterns was another important motive for extended working life. Maintaining a daily routine that included work was critical for many participants (Nobahar et al., Citation2015; Sewdas et al., Citation2017). Some participants also wanted to avoid having nothing to do post-retirement and therefore continued to work (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Fraser et al., Citation2009; Hovbrandt et al., Citation2019). Established routines helped to elude the experience of ‘not doing’ and the so called ‘occupational void’ of retirement (Bratun & Zurc, Citation2020; Hutchings et al., Citation2020).

Discussion

This systematic literature review aimed to identify the motives of retirement-aged workers in relation to continued labour participation from their perspective. Although some scholars have argued for the use of qualitative methodology in the study of the phenomenon of work beyond retirement age, the approach has been insufficiently pursued (Amabile, Citation2019; Nilsson, Citation2017). This was confirmed by our literature review that identified a small number of qualitative studies that explored the workers’ perspective. Furthermore, when screening the articles, we found that some studies did not distinguish between older workers and retirement-aged workers, making the selection process more challenging. It has been argued that being a retirement-aged worker is not the same as being an older worker; the two terms should not be used as synonyms (Friedrich et al., Citation2011). In international policies on workforce, the cut-off age for an older worker is usually 55 years (McCarthy et al., Citation2014), which is below the statutory retirement age in most countries. Older workers do not necessarily meet the retirement criteria yet and may be required to continue working regardless of their preferences. Therefore, it is important not to combine the findings of studies that include older workers with those that examine workers who work past the statutory retirement age, as their experience may be fundamentally different due to a different context and level of choice. Only when a person meets the retirement criteria and continues to work can they fully grasp and experience the context of the situation.

According to our review, retirement-aged workers appear to be a poorly represented population in the scientific literature on work motives. Also, their motives for extended working life are versatile. We will discuss some of the themes related to motivational factors that emerged from the findings of the review in connection with the dimensions of doing, being, becoming, and belonging. We recognize that there might be an overlap between the motives and that some are closely connected with more than one dimension of occupation.

Doing work: The importance of health and occupational patterns

Maintaining health was a salient theme. In the included studies, good health was identified as an important prerequisite for work, which is often reported in studies on prolonged work participation (Anxo et al., Citation2019; Furunes et al., Citation2015). Health was also perceived as a desired outcome of continued work participation that could help to defy some of the constraints of chronological age. It has been argued that the decision to continue working can be more closely related to a person’s perception of their health than age (Anxo et al., Citation2019); however, this is seldom reflected in policies and programs aimed at supporting retirement-aged workers. Moving beyond chronological age is essential for contemporary age management, particularly as age is often associated with various stereotypes, especially when it comes to older workers and their opportunities for work (e.g., Čič & Žižek, Citation2017; Cole & Hollis-Sawyer, Citation2020; Fasbender & Wang, Citation2017; Finkelstein et al., Citation2015; Harris et al., Citation2018; Posthuma & Campion, Citation2009). When age-related stereotypes become internalized—which is not uncommon—this can have far-reaching implications. For instance, it can affect the workers’ sense of belonging, their emotions, and social motivation (Rahn et al., Citation2021). From a worker’s perspective, it might be more meaningful to focus on health promotion and health maintenance rather than adopting an approach based on age (e.g., statutory retirement age). Moreover, when talking about workers’ age, we should not consider just their date of birth, but also their biological, cognitive, and social age, which might not necessarily match (Nilsson, Citation2020).

The findings of the systematic review also suggested that the fear of having nothing to do could be an important driver to continue working. Keeping familiar patterns was often a drive behind working longer. Alternatively, people incorporated new occupations and co-occupations into their routines. Co-occupations, a concept that describes the involvement of two or more people in a chosen occupation, is something that has been described in the occupational science literature before, specifically post retirement (van Nes et al., Citation2012). In addition, Jonsson (Citation2008) found that in the transition from work to retirement, another type of occupation, engaging occupation, can play a significant role in promoting people’s well-being and can be associated with more satisfying occupational patterns. Therefore, engaging occupations may be important in guiding people who face a transition such as retirement (Jonsson et al., Citation2001). For example, a person with an engaging occupation in the occupational repertoire might feel less anxious about having nothing to do post-retirement.

Being and becoming through work

Achievement and growth motives were associated with a sense of autonomy, which is an essential component of self-determination theory (SDT). SDT explains intrinsic motivation as a synthesis of the need for competence, relatedness, and autonomy (Deci & Ryan, Citation1985; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). If societies want to promote intrinsic motivation in retirement-aged workers, these needs should probably be placed at the heart of age and diversity management and consideration given to how to address them in the work milieu. For example, efforts should be made to include all workers in the work environment so that they feel connected to it, provide opportunities for continuous professional development of competence, and allow autonomy over the work process and decisions regarding work.

Another aspect of work that was important to participants was the sense of identity it provided. The role of a worker is one that cannot be easily replaced, which has been viewed as one of the most challenging aspects of the work-to-retirement transition (Eagers et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, experienced workers often assume new roles, such as mentor or teacher, which can be an inspiring source of motivation for them. However, intergenerational knowledge transfer is still underutilized in many work settings and does not occur automatically due to various barriers, including tensions in values, behaviour, and identity (Fasbender & Gerpott, Citation2021). This should probably be addressed, as sharing and teaching others seems to be an important motivator for retirement-aged workers and can contribute to a meaningful work identity of an older worker, as well as contribute to a sense of competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Furthermore, knowledge transfer is critical to the competitiveness and sustainability of modern organizations (Avery & Bergsteiner, Citation2011).

Going beyond the self at work: Belonging and transcending

Helping others and society were powerful motivators as well. This could suggest that some workers prioritize values beyond their own personal success. For example, the feeling of belonging to something greater than oneself might be more pronounced among some individuals, driving their desire to continue to participate in work-related occupations that benefit others and society. An element of contributing and serving was mentioned in most studies, regardless of location, suggesting that the gap between more and less individualistic societies may narrow as people age. This finding could be congruent with the theory of gerotranscendence (Tornstam, Citation1989). Gerotranscendence purports that, regardless of culture, some people might reconsider their priorities later in life and experience a shift in their meta-perspective from a material to a more transcendental view that involves becoming less self-centered and feeling more connected to the world (Tornstam, Citation1989). Although people can experience this mental shift at different stages of life, Tornstam (Citation1989, Citation1997, Citation2005) described it as a gradual progression toward maturity and wisdom that results in well-being. The process can include a careful selection of occupations that match the person’s altered priorities and standards. It is possible that people who achieve gerotranscendence are more likely to stop working when they reach retirement age and disengage from productivity values to focus on other life priorities. However, if they continue to work, they might be driven by the non-material rewards of prolonged labour engagement, such as serving others and facilitating the development of younger generations.

The connection between the meaning of work and spirituality has been discussed previously (Chang et al., Citation2021; May et al., Citation2004; Rosso et al., Citation2010). For some, work can be a source of purpose in life, a vocation or calling, and gives them an opportunity to transcend the self and experience a deep sense of meaning in life (Rosso et al., Citation2010). Purpose in life was identified as an important motivator in this study, too. It is possible that people who experienced purpose through their work were motivated by this throughout their careers. It is also possible that they had a harder time disengaging from their work than someone who experienced work more casually. Furthermore, some people can develop a strong attachment to a certain group through their work—whether it is a professional group, a team of co-workers or an organization as a whole—that shares a common goal or has a vision they believe in. The importance of positive relationships at work has been noted previously (Furunes et al., Citation2015). Even when studying the experience of work from retirees’ perspective, Eagers and colleagues (Citation2019) found that work relationships were an integral part of the work narrative and could sometimes be compared to belonging to a family unit.

Positive relationships in this study extended to social networks outside of work and highlighted the importance of familial support and the social context; the decision to continue working does not happen in isolation from other areas of a person’s life. When developing new competencies related to managing a diverse workforce and supporting the well-being of older workers, it could be essential to focus not only on the individual, but also on the social and family context that might play an essential role in the worker’s decision to either postpone retirement or retire. While retirement has often been viewed as one of the major transitions in a person’s life (Amabile, Citation2019), its impact may extend beyond the individual and require careful (re)orchestration of the entire family unit and its occupations.

Limitations and future directions

As per our inclusion criteria, we made an effort to only include qualitative studies about workers who met the retirement criteria and could access a pension or superannuation. It is possible that some articles that were excluded due to a lack of information that could help us assess whether they met the inclusion criteria nevertheless met them, potentially reducing the number of themes we identified. However, it has previously been argued that when doing systematic reviews of qualitative studies, the sample can sometimes be purposive rather than exhaustive (Doyle, Citation2003). Another limitation could be that different countries apply different laws and regulations to retirement and continuous work participation, therefore, the samples differed in their age range and context depending on the location of the study. Although workers’ chronological ages and contexts differed, they shared the experience of fulfilling the retirement criteria and having access to a pension.

A possible methodological limitation was also that the thematic synthesis was conducted by only one of the researchers due to time constraints. However, the other two authors critically examined the findings and provided feedback that was considered in the final version of the analysis. The critical dialogue between the authors increased the rigour of the analysis and followed what has been termed the ‘critical friend’ approach, where the purpose was not to achieve consensus but to encourage reflexivity (Smith & McGannon, Citation2017).

The advantages and disadvantages of doing thematic synthesis as part of a qualitative systematic review have been discussed previously and we are aware of the risks of generalizing based on these findings or taking findings out of a particular context (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). If a reader wants to get an uncondensed picture and a better understanding of the richness of the data in a particular study, they need to access individual articles. We felt that by summarizing the relevant data, we were able to bring findings together and thereby synthesize aspects of relevance for future studies as well as inform policy and practice.

In this study, we applied the concepts of doing, being, becoming, and belonging to the study of motives for prolonged work engagement, which, to the best of our knowledge, has not been considered before. External motives, such as Finances, that were more closely associated with the doing or observable dimension of occupation, were an important element in the decision to continue working. Nonetheless, many of the identified motives related to non-material rewards and could be described as intrinsic incentives for work, such as having A sense of purpose in life, fostering Positive relationships and Helping others and society.

While financial perks most likely play a role in the decision to continue working, there might be a group of workers who are not motivated by finances, or less so. Fideler (Citation2012), too, found that 70% of Baby boomers work past retirement for reasons other than financial, suggesting that an approach that goes beyond tangible rewards is required if we are to support and empower older workers who consider delaying retirement. On the other hand, we need to consider that the samples in the included qualitative studies consisted of a large number of educated professionals who were probably in a privileged position compared to their peers in less skilled jobs or from lower socio-economic backgrounds, therefore, could be in an advantageous position to focus on the intrinsic rewards of work. In addition, data from non-Western contexts were in the minority, so the results should be considered as limited to certain regions of the world.

Future studies could use other theoretical frameworks or conceptual models to provide a more in-depth analysis of the revealed motives. For example, the Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance Model or PEOP Model (Baum et al., Citation2015) could provide a valuable lens to elaborate on the importance of person-environment fit when supporting retirement-aged workers’ engagement in work occupations and could also be applied at population and organizational levels. The Model of Human Occupation or MOHO (Kielhofner, Citation2008) could help explain the volition and habituation aspects of prolonged labour engagement, while the Sustainable Working Life for All Ages (SwAge) model (Nilsson, Citation2020) could be used to examine the micro (individual), meso (organizational), and macro (societal) levels of extended working life from an occupational perspective.

Conclusions

This systematic review confirmed that workers who prolong formal employment experience work as more than the act of ‘doing’ and remuneration. Other dimensions of this occupation, which might be less tangible and more challenging to describe, appear to be at least as important to this group of workers. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the individual experience of an extended working life, the dimensions of doing, being, becoming, and belonging should be considered together and explored for the meaning ascribed to work.

According to the studies included in the review, both intrinsic end extrinsic motivation for work feature in the narratives of retirement-aged workers. Work often provides a sense of purpose, achievement, autonomy, and enjoyment, resulting in increased well-being of individuals and groups. The ways in which work permeates many people’s sense of self and the world around them should be considered when people who wish to continue working are compulsorily retired—for example, through implementation of a mandatory retirement age—and what impact this might have on their health and well-being. Furthermore, strategies and policies aimed at prolonged work engagement should probably go beyond the rhetoric of active ageing and address the motivation for prolonged working life in a holistic way that appreciates the heterogeneity of retirement-aged workers and their occupations. Societies should strive for a system that could support the diversity of workers and provide opportunities for the development of different levels of motives within the work environment and beyond.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Amabile, T. M. (2019). Understanding retirement requires getting inside people’s stories: A call for more qualitative research. Work, Aging and Retirement, 5(3), 207–211. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waz007

- Anxo, D., Ericson, T., & Herbert, A. (2019). Beyond retirement: Who stays at work after the standard age of retirement? International Journal of Manpower, 40(5), 917–938. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-09-2017-0243

- Arnott, R. D., & Casscells, A. (2003). Demographics and capital market returns. Financial Analysts Journal, 59(2), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v59.n2.2511

- Avery, G., & Bergsteiner, H. (2011). Diagnosing leadership in global organisations: Theories, tools and cases. Tilde.

- Baum, C. M., Christiansen, C. H., & Bass, J. D. (2015). The Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) model. In C. H. Christiansen, C. M. Baum, & J. D. Bass (Eds.), Occupational therapy: Performance, participation, and well-being (4th ed., pp. 49–56). Slack.

- Björklund Carlstedt, A., Brushammar, G., Bjursell, C., Nystedt, P., & Nilsson, G. (2018). A scoping review of the incentives for a prolonged work life after pensionable age and the importance of “bridge employment.” Work, 60(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-182728

- Bovenberg, A. L. (2003). Financing retirement in the European Union. International Tax and Public Finance, 10(6), 713–734. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026390122672

- Bratun, U., & Zurc, J. (2020). The motives of people who delay retirement: An occupational perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2020.1832573

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). (2009). Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. University of York, CRD. https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf

- Chand, M. (2018). Aging in South Asia: Challenges and opportunities. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 7(2), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-09-2017-0103

- Chang, P.-C., Gao, X., & Wu, T. (2021). Sense of calling, job crafting, spiritual leadership and work meaningfulness: A moderated mediation model. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(5), 690–704. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-09-2020-0392

- Coile, C., & Levine, P. (2011). The market crash and mass layoffs: How the current economic crisis may affect retirement. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 11(1), 1–42. https://ideas.repec.org/a/bpj/bejeap/v11y2011i1n22.html

- Cole, E., & Hollis-Sawyer, L. (Eds.). (2020). Older women who work: Resilience, choice, and change. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pubs/books/older-women-who-work

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Čič, Ž. V., & Žižek, S. Š. (2017). Intergenerational cooperation at the workplace from the management perspective. Naše Gospodarstvo/Our Economy, 63(3), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1515/ngoe-2017-0018

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self determination in human behavior. Plenum Press.

- Del Barrio, E., Marsillas, S., Buffel, T., Smetcoren, A.-S., & Sancho, M. (2018). From active aging to active citizenship: The role of (age) friendliness. Social Sciences, 7(8), Article 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7080134

- Denton, F. T., & Spencer, B. G. (2009). What is retirement? A review and assessment of alternative concepts and measures. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 28(1), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980809090047

- Dorfman, L. T. (2000). Still working after age 70: Older professors in academe. Educational Gerontology, 26(8), 695–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/036012700300001368

- Doyle, L. H. (2003). Synthesis through meta-ethnography: Paradoxes, enhancements, and possibilities. Qualitative Research, 3(3), 321–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794103033003

- Eagers, J., Franklin, R. C., Broome, K., & Yau, M. K. (2019). The experiences of work: Retirees’ perspectives and the relationship to the role of occupational therapy in the work-to-retirement transition process. Work, 64(2), 341–354. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-192996

- Ehni, H., Kadi, S., Schermer, M., & Venkatapuram, S. (2018). Toward a global geroethics – Gerontology and the theory of the good human life. Bioethics, 32(4), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12445

- Eurofound. (2017). Extending working life: What do workers want? Eurfound. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2017/eu-member-states/extending-working-life-what-do-workers-want

- Eurostat. (2020). Ageing Europe – Statistics on working and moving into retirement. Eurostat. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_statistics_on_working_and_moving_into_retirement#Employment_patterns_among_older_people

- Fasbender, U., & Gerpott, F. H. (2021). Knowledge transfer between younger and older employees: A temporal social comparison model. Work, Aging and Retirement. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waab017

- Fasbender, U., & Wang, M. (2017). Negative attitudes toward older workers and hiring decisions: Testing the moderating role of decision makers core self-evaluations. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 2057. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02057

- Fideler, E. (2012). Women still at work: Professionals over sixty and on the job. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Finkelstein, L. M., King, E. B., & Voyles, E. C. (2015). Age metastereotyping and cross-age workplace interactions: A meta view of age stereotypes at work. Work Aging and Retirement, 1(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/wau002

- Flynn, M. (2010). Who would delay retirement? Typologies of older workers. Personnel Review, 39(3), 308–324. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483481011030511

- Fraser, L., McKenna, K., Turpin, M., Allen, S., & Liddle, J. (2009). Older workers: An exploration of the benefits, barriers and adaptations for older people in the workforce. Work, 33(3), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2009-0874

- Friedrich, L. A., Prasun, M. A., Henderson, L., & Taft, L. (2011). Being a seasoned nurse in active practice. Journal of Nursing Management, 19(7), 897–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01294.x

- Furunes, T., Mykletun, R. J., Solem, P. E., de lange, A. H., Syse, A., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ilmarinen, J. (2015). Late career decision-making: A qualitative panel study. Work Aging and Retirement, 1(3), 284–295. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/wav011

- Grah, B., Perme, E., Colnar, S., & Penger, S. (2019). Age management: What can we learn from high-end luxury fashion designer with more than 50 years of working experience? Organizacija, 52(4), 325–344. https://doi.org/10.2478/orga-2019-0020

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Harris, K., Krygsman, S., Waschenko, J., & Laliberte Rudman, D. (2018). Ageism and the older worker: A scoping review. The Gerontologist, 58(2), e1–e14. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw194

- Henning, G., Stenling, A., Tafvelin, S., Hansson, I., Kivi, M., Johansson, B., & Lindwall, M. (2019). Preretirement work motivation and subsequent retirement adjustment: A self-determination theory perspective. Work, Aging and Retirement, 5(2), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/way017

- Heylen, F., & Van de Kerckhove, R. (2019). Getting low educated and older people into work: The role of fiscal policy. Journal of Policy Modeling, 41(4), 586–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2019.02.001

- Hitch, D., & Pepin, G. (2021). Doing, being, becoming and belonging at the heart of occupational therapy: An analysis of theoretical ways of knowing. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 28(1), 13–25. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10. 1080/11038128.2020.1726454

- Hitch, D., Pépin, G., & Stagnitti, K. (2014). In the footsteps of Wilcock, part two: The interdependent nature of doing, being, becoming, and belonging. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 28(3), 247–263. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10. 3109/07380577.2014.898115

- Hovbrandt, P., Håkansson, C., Albin, M., Carlsson, G., & Nilsson, K. (2019). Prerequisites and driving forces behind an extended working life among older workers. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 26(3), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2017.1409800

- Hutchings, K., Wilkinson, A., & Brewster, C. (2020). Ageing academics do not retire - they just give up their administration and fly away: A study of continuing employment of older academic international business travellers. International Journal of Human Resource Management. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1754882

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (2014). Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual (2014 ed.). The Joanna Briggs Institute. https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/JBI/docs/ReviewersManuals/ReviewersManual.pdf

- Jonsson, H. (2008). A new direction in the conceptualization and categorization of occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 15(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2008.9686601

- Jonsson, H., Josephsson, S., & Kielhofner, G. (2001). Narratives and experience in an occupational transition: A longitudinal study of the retirement process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55(4), 424–432. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.55.4.424

- Kielhofner, G. (2008). Model of human occupation: Theory and application. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Kooij, D., de Lange, A., Jansen, P., & Dikkers, J. (2008). Older workers’ motivation to continue to work: Five meanings of age: A conceptual review. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(4), 364–394. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810869015

- Krekula, C., & Vickerstaff, S. (2020). The ‘older worker’ and the ‘ideal worker’: A critical examination of concepts and categorizations in the rhetoric of extending working lives. In A. Ni Leine, J. Ogg, M. Rašticová, D. Street, C. Krekula, M. Bédjová, & I. Madero-Cabib (Eds.), Extended working lives policies (pp. 29–45). Springer Open. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40985-2_2

- Maestas, N., & Zissimopoulos, J. (2010). How longer work lives ease the crunch of population aging. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(1), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.24.1.139

- May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892

- McCarthy, J., Heraty, N., Cross, C., & Cleveland, J. N. (2014). Who is considered an ‘older worker’? Extending our conceptualisation of ‘older’ from an organisational decision maker perspective. Human Resource Management Journal, 24(4), 374–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12041

- Munn, Z., Stern, C., Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., & Jordan, Z. (2018). What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4

- Newton, N., & Ottley, K. (2020). Work-related choice and identity in older women. In E. Cole, & L. Hollis-Sawyer (Eds.), Older women who work: Resilience, choice, and change (pp. 69–86). American Psychological Association.

- Nilsson, K. (2016). Conceptualisation of ageing in relation to factors of importance for extending working life - A review. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 44(5), 490–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494816636265

- Nilsson, K. (2017). Active and healthy ageing at work – A qualitative study with employees 55-63 years and their managers. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 5(7), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2017.57002

- Nilsson, K. (2020). A sustainable working life for all ages – The swAge-model. Applied Ergonomics, 86, Article 103082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2020.103082

- Nobahar, M., Ahmadi, F., Alhani, F., & Khoshknab, M. F. (2015). Work or retirement: Exploration of the experiences of Iranian retired nurses. Work, 51(4), 807–816. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-141943

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2019). Pensions at a glance 2019: OECD and G20 indicators. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/99acb105-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/99acb105-en#tablegrp-d1e15882

- Phillipson, C. (2019). ‘Fuller’ or ‘extended’ working lives? Critical perspectives on changing transitions from work to retirement. Ageing and Society, 39(3), 629–650. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18000016

- Posthuma, R. A., & Campion, M. A. (2009). Age stereotypes in the workplace: Common stereotypes, moderators, and future research directions. Journal of Management, 35(1), 158–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308318617

- Rahn, G., Martiny, S. E., & Nikitin, J. (2021). Feeling out of place: Internalized age stereotypes are associated with older employees’ sense of belonging and social motivation. Work, Aging and Retirement, 7(1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waaa005

- Reynolds, F., Farrow, A., & Blank, A. (2012). “Otherwise it would be nothing but cruises”: Exploring the subjective benefits of working beyond 65. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, 7(1), 79–106. https://doi.org/10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.127179

- Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

- Rudnicka, E., Napierała, P., Podfigurna, A., Męczekalski, B., Smolarczyk, R., & Grymowicz, M. (2020). The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas, 139 (September 2020), 6-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.05.018

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2017). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10. 1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Sewdas, R., de Wind, A., van der Zwaan, L., van der Borg, W. E., Steenbeek, R., van der Beek, A. J., & Boot, C. R. L. (2017). Why older workers work beyond the retirement age: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 17, Article 672. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4675-z

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, Article 45, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Tornstam, L. (1989). Gero-transcendence: A meta-theoretical reformulation of the disengagement theory. Aging: Clinical and Experimental Research, 1(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03323876

- Tornstam, L. (1997). Gerotranscendence: The contemplative dimension of aging. Journal of Aging Studies, 11(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-4065(97)90018-9

- Tornstam, L. (2005). Gerotranscendence: A developmental theory of positive aging. Springer.

- Ulrich, L. B., & Brott, P. E. (2005). Older workers and bridge employment: Redefining retirement. Journal of Employment Counseling, 42(4), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2005.tb01087.x

- van Nes, F., Jonsson, H., Hirschler, S., Abma, T., & Deeg, D. (2012). Meanings created in co-occupation: Construction of a late-life couple’s photo story. Journal of Occupational Science, 19(4), 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2012.679604

- Wilcock, A. A. (2006). An occupational perspective of health (2nd ed.). Slack.

- Wolverson, C., & Hunt, L. A. (2015). Sustainability. In L. A. Hunt, & C. Wolverson (Eds.), Work and the older person: Increasing longevity and well-being (pp. 135–145). Slack.