ABSTRACT

Mentoring relationships are pathways to the sharing of tacit knowledge regarding the realities of professional practice, and good evidence supports the efficacy of mentorship among occupational therapists. Mentorship in specific practice areas can be difficult to recruit, and alternative mentoring models and platforms are emerging. This article presents a model of short-term group mentoring using a remote platform in the assistive technology (AT) practice arena. Conducted as a quality improvement activity within two professional associations, four volunteer mentees and five mentors engaged in three 75-minute Zoom-based mentoring sessions over three months. Content was collaboratively designed by a mentee/ mentor dyad from both professional associations. Pre and post-surveys were conducted and analysed to explore the experiences and outcomes for all participants. Positive outcomes for both mentees and mentors were reported, with a range of benefits identified in this small pilot study, Small group time-limited mentoring on topics of mutual interest are likely to be a time effective ‘starting point’ to partially meet mentorship needs. Mentoring remains an enduring and relevant pathway to support occupational therapists to do, to be and to become reflective and competent practitioners. In the face of pragmatic constraints, strategies such as short-term mentoring, group mentoring, and mentoring in a focal practice area, show great promise and may support further mentoring actions. Use of increasingly ubiquitous virtual/remote platforms, particularly in the twenty-first century and with the influence of pandemic-related distancing, are a promising enabler of connection.

Introduction

Mentoring is thought to have been a common practice in human interactions since the earliest civilisations (Kammeyer-Mueller & Judge, Citation2008) and is widely perceived to be an important part of a health professional’s career development. Mentoring can be defined as ‘both a relationship and process between two individuals who share and build knowledge, expertise and support’ (Jacobs et al., Citation2015, p. 201). The concept of mentoring differs from that of clinical, professional or managerial supervision. In the health professions, clinical or professional supervision refers to ‘a formal process of professional support and learning which enables a practitioner (supervisee) to develop knowledge and competence, assume responsibility for their own practice, and enhance public protection and safety’ (Occupational Therapy Board of Australia, Citation2014, p. 2). Professional supervision aims to promote optimal care, safety, and well-being for service users in accordance with organisations’ and professional standards (College of Occupational Therapists, Citation2015; Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2012). It is part of an organisation’s duty of care for staff in creating safe and supportive opportunities to engage in critical reflection in order to raise issues, explore problems, and discover new ways of handling both the situation and oneself (Occupational Therapy Australia [OTA], Citation2019, p. 7).

Falzarano and Falzarano and Pinto Zipp (Citation2012) investigated some of the characteristics that result in a positive mentoring experience, which include an ability to provide information and support from the mentor; as well as the benefits, such as having someone to go to, easing stress. This is one of the few pieces of literature to include the challenges of not enough time, and the value, or lack thereof, that mentoring is given within an organisation. McAllister et al. (Citation2009) explored the need for targeted mentoring programmes, finding that mentors were more satisfied with the experience in terms of ‘giving back’ to the community than were the mentees who were looking for specific skills as well as psychosocial support. A scoping review by Doyle et al. (Citation2019) reports that mentoring positively affects behaviour, attitude, motivation, job performance, organisational commitment, career productivity and success, and called for ‘occupational therapy practitioners and researchers to continue researching mentoring experiences by integrating theoretical frameworks, uniform definitions, rigorous design and standardised measures to evaluate the effectiveness of mentoring’ (p. 541).

In this study, we regard mentoring as voluntary partnerships for support and growth in a practice area.

Styles of mentoring

There are a range of ways that mentoring can be delivered, including individual (1:1), in dyads or triads, and in groups. Mentoring can be face-to-face, or delivered by telephone, or using online, digital methods (e-mentoring).

E-mentoring is described as an ‘adaptable electronically mediated process that can be scaled to fit the needs of the mentees, mentors and host organizations and is unencumbered by time and geographical restrictions [and can be] personalised, mutually beneficial and asynchronous nurturing mentoring relationships and complementing face-to-face mentoring approaches’ (Chong et al., Citation2020, p. 16). Chong et al’s (Citation2020) extensive review proposed the use of blended programs to manage rapport-building challenges, particularly for medical student education.

Jacobs et al. (Citation2015) investigated an e-mentoring programme delivered to post-doctoral health professionals and found that the approach had positive results for accessibility for both mentees, but also for mentors. Thereby they potentially address an issue identified by Chong et al. (Citation2020) of difficulties sourcing and recruiting mentors for health professional programmes, as well as an ability to be responsive to real-time needs for support. Jacobs et al. (Citation2015) also found that their e-mentoring programme has a positive impact on professional development.

Additionally, how mentoring runs can differ, with some programs or organisations offering training to mentors, and others not; varying levels of choice of mentor by mentee, and a wide gamut of methods of evaluation, including no evaluation at all (Ehrich et al., Citation2004). Milner and Bossers (Citation2004) found that many mentor relationships continued informally after the formal period ended.

Uptake of mentoring, and evaluation of mentoring

Mentoring is identified as a professional support with significant potential for occupational therapists and often conducted by professional associations for example, Occupational Therapy Australia (OTA) (Layton & Kuok, Citation2020; Wilding et al., Citation2003) and the Canadian Occupational Therapy (Lapointe et al., Citation2013), with particular focus on the relationship between leadership and mentoring. Due to the impact of competing resourcing demands in professional practice, there is a need for mentoring programmes to be rigorously evaluated in order to demonstrate a positive effect and outcome. There is also a need for more profession-specific, cross-disciplinary and contextually based studies into the phenomenon (Doyle et al., Citation2019; Falzarano & Pinto Zipp, Citation2012; Sambunjak et al., Citation2006). Jacobs et al. (Citation2015) suggest that further investigation is required into the delivery of mentoring via online and digital means (e-mentoring). McAllister et al. (Citation2009) suggest a need for future investigation into the needs and delivery of targeted mentoring approaches.

Taken together, the occupational therapy mentorship literature coheres around the view that the evidence base is not yet fully explored, and that mentoring in specific fields of practice, models of delivery, and mechanisms of evaluation requires additional investigation (Milner & Bossers, Citation2005).

Meeting the assistive technology mentoring needs of an internet-enabled workforce

This study came about as a joint activity between Australia’s peak body for assistive technology, Australian Rehabilitation & Assistive Technology Association (ARATA), and OTA as peak body for occupational therapy. Assistive technology is a key area of practice for occupational therapists and one which requires continuous professional development in light of both technological changes and changing policy contexts both globally and in Australia (World Health Organisation (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Citation2022; Friesen et al., Citation2015).

The broader context is one of increasing graduate numbers from occupational therapy programmes across Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2020); the changing profile of workplaces with a loss of occupational therapy department structures and related supervisory/ mentoring opportunities ‘in house’; increasing sole practitioner positions; and a major increase in the demand for competent assistive technology practice with the advent of Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme (National Disability Insurance Agency [NDIA], Citation2020). The changing nature of volunteering including the difficulty recruiting suitably experienced and qualified mentors can be seen across a range of industries (McAllister et al., Citation2009). Workforce issues including retirement of more experienced professionals leads to a reduction in the pool from which appropriate mentors can be drawn. The combination of these factors results in an increasing need and demand for professional support including mentoring and supervision coupled with a decreasing supply of available resources.

Recruitment of mentors is a common difficulty in mentoring programmes (Milner & Bossers, Citation2005). Individual dyads are the usual mentoring partnership approach supported by OTA, however, with the ratio of mentors to mentees falling short of meeting the emerging need for experienced mentors, an alternative, short-term group mentoring approach was taken, and is evaluated here.

Research aims

To co-design and pilot short term online group mentoring for occupational therapists in assistive technology

To inform communities of practice (OTA, ARATA) regarding the benefits and issues of such a programme to meet the needs of the future workforce.

Methods

Ethics

Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee approved: project ID: 30,025.

Participants

Mentors were sourced through an email invitation to the ARATA listserv. Mentors selected were occupational therapists, members of both OTA and ARATA, and all had a minimum of five years clinical experience. Mentees were sourced from the MentorLink Programme and were selected according to their interest and need. The pilot ran monthly as the Assistive Technology Group Mentoring Series from May to July 2020. Four mentees and five mentors participated.

Theoretical framework

A theoretical foundation for analysis was selected. Wilcock (Citation1999, Citation2007) proposed a framework for occupation-focused practice that revolves around the concepts of doing, being, becoming and belonging (Berger et al., Citation2022; Doroud et al., Citation2018; Hitch et al., Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Hitch & Pepin, Citation2021). Occupational therapists have also applied this framework to the process of forming and reforming professional identity, such as moving from practice into academia (Ennals et al., Citation2016), or through an occupational therapy training programme (Taff et al., Citation2018). When applied this way, ‘doing’ can be seen as comprising of the practice actions of a job or role; ‘being’ can be seen as the development of self-care and resilience to support oneself in role; ‘becoming’ can be seen as the taking on of the professional mantle of the role, and ‘belonging’ can be seen as the apex of professional identity and networking – belonging to the job, role and profession (Wilcock, Citation1999; Citation2007). Mentoring programmes can be viewed as playing a key role in the formation of professional identity and job role expertise in health professionals.

Study design

This study was a small-scale pilot project which was audited for the purposes of quality improvement. A pre- and post-survey were conducted to review the utility and benefit offered by the group mentoring model, and gather recommendations for future directions.

Quantitative and qualitative programme evaluation data was collected. Online surveys were emailed to and completed by participants prior to the programme, and again following the last session with responses returned within three weeks. All responses were anonymous and only accessible by members of the research team.

The survey included a five-point Likert scale (1: very poor – 5: excellent) for participants to rate factors in their professional life thinking specifically about the last month and the area of assistive technology. Mentors were also asked to rate mentor specific factors using the Likert scale (e.g. Mentoring confidence). The survey also included an open-ended section to allow participants to provide clarifications to responses or feedback on the programme.

The components chosen to be rated were outcomes and benefits of mentoring described by the OTA MentorLink programme (Occupational Therapy Australia, Citation2013). Collecting this data provided an insight into whether the benefits described in one-on-one mentoring relationships in occupational therapy could also be observed in a group e-mentoring setting.

Intervention/pilot programme

The programme itself comprised an evidence-based selection of resources, prepared by mentee/ mentor dyad (NL and BK) and provided as background to participants and via screen share during the mentoring group sessions. The format was one of active engagement and mutual recognition. Each session included sharing of backgrounds, motivations, current work situations, and examples from our lives as occupational therapists practicing in assistive technology. Discussions were guided by topics that enabled a question, answer, and turn taking style of conversation and storytelling. summarises the monthly Zoom programme, content and structure.

Table 1. Assistive technology group mentoring protocol.

Data collection and analysis

The qualitative data were separated into mentees and mentors, then analysed for themes to allow the main patterns from multiple responses to be summarised. The Likert scale ratings from each response were formatted into a table to calculate the group average rating for each component. This was performed for both the pre and post data to compare overall differences between group averages following the programme.

Data analysis

To specify and operationalise mentoring concepts for this study, the work of Doyle et al. (Citation2019) is adopted. Focussing on the occupational literature from 2002–2018, Doyle et al synthesised the terms, mechanisms and outcomes of mentoring into four categories: support, learning, process and relationship. Mentoring processes and relationships were facilitated by mechanisms of:

Creating a plan

Using mentoring strategies

Providing support

Knowledge acquisition and translation

Professional behaviours

Increased productivity

Professional networking

Results

Eight female occupational therapists participated in the programme, identifying as mentees (n-3) or mentors (n-5). There were a total of 7 responses for the pre-programme survey (3 mentees, 4 mentors) and 8 responses for the post-programme survey (3 mentees, 5 mentors).

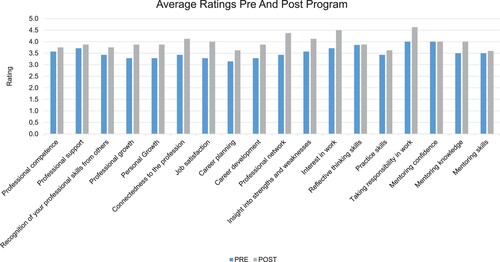

As a group, there were self-reported improvements or no change in all areas with the greatest improvements being in: Professional Network, Interest in Work, Connectedness to the Profession, and Job Satisfaction – illustrated in . There were no self-reported changes with Reflective Thinking Skills.

Figure 1. Average ratings pre and post program (1: very poor, 2: poor, 3: fair, 4: good, 5: excellent).

Pre-program survey comments

Comments reflected on current practice and identified potential for development within the role and through the program; ‘The last month has involved increased flexibility and growth in my professional practice’.

Mentors specifically commented on goals to develop their mentoring experience:

… looking forward to this opportunity to further develop my skills and experience’; ‘looking forward to developing an active mentoring engagement atmosphere’; ‘ … looking forward to building my mentoring skills further.

Post-programme survey comments

Participants commented on benefits of the programme in developing as an occupational therapist, and suggestions for future programs.

Benefits that were reported involved the social aspects of the programme:

‘it was great to meet different people in the profession’; ‘always helpful to reflect on practice with critical friends, this process enabled this to occur’

‘I have learnt how to develop as an occupational therapist’; ‘ … has been challenging in regard to increased decision making and how to best and most safely deliver services and facilitate best AT [Assistive Technology] outcomes’.

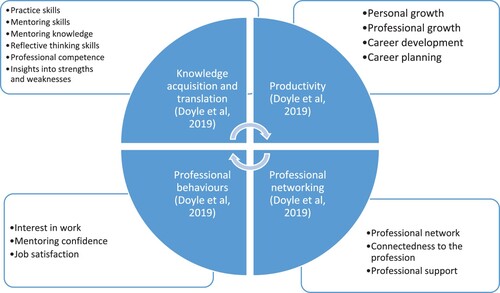

Four core purposes of mentoring are described by Doyle et al. (Citation2019) as knowledge acquisition and translation; productivity, professional behaviours; and professional networking. maps the narrative terms used by participants in this study to each of these outcome areas, reflecting that participant’s experiences resonated across this range of mentoring purposes.

Doing

Conversations about experience in practice validated existing concerns from mentees in work and provided insight to potential challenges that could arise. Mentors enjoyed hearing about current jobs and contemporary practice challenges, some of which were the same as when mentors were new graduates, and some very different. Mentees had current knowledge of models of practice, and mentors had old favourites which were shared and analysed. The overall content of sessions was also observed to be translated through different work contexts with a sense of trajectory across the three sessions.

Figure 2. Mentoring outcomes, using the four core purposes of mentoring as outlined by Doyle et al. (Citation2019). Mentoring Outcomes. In the figure below, the responses from participants in this study are mapped to Doyle et al.’s (Citation2019) four core purposes of mentoring.

Being

Whilst being mindful of meeting the learning needs of mentees, each participant experienced different clinical dilemmas and practice constraints. As a result, there were lots of sharing of ideas and potential strategies based on past practice knowledge.

Mentors and mentees valued the programme. It was learnt that three sessions were useful, but monthly sessions were spaced too far apart. A three-weekly series was recommended. A 6pm time slot worked across time zones, though some participants were commuting home from work during this period. Whether a group format would be a challenge for mentees to share their concerns and dilemmas and seek individualised discussions was considered, however, the results indicated that mentees experienced an uplift in their interest in work and job satisfaction as a result of the programme; and in fact they were seeking out this experience (as were mentors) for growth opportunities.

Becoming

Mentees and mentors commented on the development that had taken place in themselves as occupational therapists, and in their critical thinking skills as an occupational therapist in the assistive technology space as a result of the group mentoring program. For mentors, the pilot programme enabled an opportunity to try out or move into the new professional identity of ‘mentor’ in addition to their occupational therapy identity, as well as exploring the identity of political activists.

Belonging

Group mentoring provided an enjoyable opportunity for participants to meet and talk with colleagues. Mentees described it was beneficial to hear the mentors discuss their practice issues – current and past – and hear the perspectives that a group of ‘critical friends’ could offer. Several mentors offered to continue mentorship arrangements individually.

Always helpful to reflect on practice with critical friends, this process enabled this to occur. Particularly useful to reflect on a career of practice, through the eyes of newer graduates, as this provides insights about ways of thinking, contemporary models etc. – Mentor

Discussion

This article describes the assistive technology group mentoring programme pilot including the benefits and areas of improvement. Improvement in the domains of professional networking, interest in work, job satisfaction and connectedness to the profession were seen across the particular framework areas of being and belonging (Doyle et al., Citation2019; Wilcock, Citation1999; Citation2007). To a lesser extent, the framework areas of doing and becoming were enhanced through discussion of specific practice contexts and situations and the sharing of practice resources; and in the development of critical thinking skills and new professional identities (Doyle et al., Citation2019; Wilcock, Citation1999, Citation2007). Three out of the four mentors have signed up to provide individual mentoring. This pilot demonstrated significant potential to connect people interested in assistive technology, develop occupational therapists across the four framework areas of doing, being, becoming and belonging (Wilcock, Citation1999, Citation2007); and may be a useful addition to any individual mentoring program as it runs. While this pilot was able to use a pre and post research design, as suggested in the literature, it was unable to avoid some of the pitfalls of research in the area, such as a small-scale single case design and a reliance on self-reports (Doyle et al., Citation2019; Falzarano & Pinto Zipp, Citation2012; Milner & Bossers, Citation2005; Sambunjak et al., Citation2006).

Further research is needed to establish the long-term impact of mentoring on the development of professional practice skills, professional resilience, the formation of professional identity and its role in developing a sense of belonging to a community of practice (Doyle et al., Citation2019). The role that group mentoring could play in this, both in terms of process and wise use of resources requires further investigation. The use of e-mentoring techniques within group and individual mentoring sessions would be beneficial to explore further (Doyle et al., Citation2019; Falzarano & Pinto Zipp, Citation2012; Milner & Bossers, Citation2005; Sambunjak et al., Citation2006). Whilst the small-scale, pilot nature of this study limits its validity and reliability, as a pilot project it provides a valid test of the method of delivery of group e-mentoring in this practice area, a valid test of the survey questions asked, as well as indicators of what might be an appropriate sample size should further research be completed.

Limitations

This study was a small-scale pilot project which was audited for quality improvement purposes. It contained a small group of participants, and its single case design represents a unique population. As such, the results are not intended to be generalisable across populations and should be interpreted and used with caution.

Conclusion and implications

This pilot study demonstrates the feasibility and acceptability of group e-mentoring in the arena of assistive technology. These findings mirror the literature in regard to the positive effect that mentoring may have on a range of work-based and professional domains, such as knowledge acquisition and translation, professional behaviours, the potential for increased productivity (related to higher levels of motivation and job satisfaction), and professional networking. Additionally, the findings may strongly support the development of professional resilience, particularly in mentees, but also in mentors, who spoke about the benefit to themselves of speaking about challenging practice contexts and situations, demonstrating a novel use of therapeutic use of self, a recognised part of the occupational therapy process. Despite its small scale, learnings from this Australian study suggests group e mentoring could be shared and scaled.

Author’s declaration of authorship contribution

BK and NL conceived and designed the study, provided initial analysis and interpretation of data, and completed first draft. AV provided the literature review, developed the theoretical lens for the discussion, provided interpretation of the results within the theoretical lens, and conducted major revisions to drafts. LS oversaw the project, read and edited drafts, and provided critical advice. All members were involved with analysing and interpreting the data, and all members are to be involved in the final approval of the version to be published.

Acknowledgements

The professional bodies ARATA and OTA, and the mentors and mentees who participated in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). Health workforce. Retreived March, 2020. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-workforce.

- Berger, M., Asaba, E., Fallahpour, M., & Farias, L. (2022). The sociocultural shaping of mothers’ doing, being, becoming and belonging after returning to work. Journal of Occupational Science, 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1845226

- Chong, J. Y., Ching, A. H., Renganathan, Y., Lim, W. Q., Toh, Y. P., Mason, S., & Krishna, L. K. R. (2020). Enhancing mentoring experiences through e-mentoring: A systematic scoping review of e-mentoring programs between 2000 and 2017. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 25(1), 195–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-019-09883-8

- College of Occupational Therapists. (2015). Occupational therapy standards & code of ethics. Retreived March, 2020. https://www.rcot.co.uk/practice-resources/rcot-publications/downloads/rcot-standards-and-ethics.

- Doroud, N., Fossey, E., & Fortune, T. (2018). Place for being, doing, becoming and belonging: A meta-synthesis exploring the role of place in mental health recovery. Health & Place, 52, 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.05.008

- Doyle, N., Gafni Lachter, L., & Jacobs, K. (2019). Scoping review of mentoring research in the occupational therapy literature, 2002–2018. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12579

- Ehrich, L. C., Hansford, B., & Tennent, L. (2004). Formal mentoring programs in education and other professions: A review of the literature. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40(4), 518–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X04267118

- Ennals, P., Fortune, T., Williams, A., & D'Cruz, K. (2016). Shifting occupational identity: Doing, being, becoming and belonging in the academy. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(3), 433–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1107884

- Falzarano, M., & Pinto Zipp, G. (2012). Perceptions of mentoring of full-time occupational therapy faculty in the United States. Occupational Therapy International, 19(3), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.1326

- Fitzpatrick, S., Smith, M., & Wilding, C. (2012). Quality allied health clinical supervision policy in Australia: A literature review. Australian Health Review, 36(4), 461–464. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH11053

- Friesen, E., Walker, L., Layton, N., Astbrink, G., Summers, M., & De Jonge, D. (2015). Informing the Australian government on AT policies: ARATA’s experiences. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 10(3), 236–239. https://doi.org/10.3109/17483107.2014.913711

- Hitch, D., & Pepin, G. (2021). Doing, being, becoming and belonging at the heart of occupational therapy: An analysis of theoretical ways of knowing. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 28(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2020.1726454

- Hitch, D., Pepin, G., & Stagnitti, K. (2014a). In the footsteps of Wilcock, part one: The evolution of doing, being, becoming, and belonging. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 28(3), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2014.898114

- Hitch, D., Pepin, G., & Stagnitti, K. (2014b). In the footsteps of Wilcock, part two: The interdependent nature of doing, being, becoming, and belonging. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 28(3), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2014.898115

- Jacobs, K., Doyle, N., & Ryan, C. (2015). The nature, perception, and impact of e-mentoring on post-professional occupational therapy doctoral students. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 29(2), 201–213. https://doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2015.1006752

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Judge, T. A. (2008). A quantitative review of mentoring research: Test of a model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(3), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.09.006

- Lapointe, J., Baptiste, S., von Zweck, C. M., & Craik, J. M. (2013). Developing the occupational therapy profession through leadership and mentorship: Energizing opportunities. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin, 68(2), 38–43. https://doi.org/10.1179/otb.2013.68.1.011

- Layton, N., & Kuok, B. (2020). Exchanging ideas, knowledge and support. Connect, 17(4), 30–32.

- McAllister, C. A., Harold, R. D., Ahmedani, B. K., & Cramer, E. P. (2009). Targeted mentoring: Evaluation of a program. Journal of Social Work Education, 45(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2009.200700107

- Milner, T., & Bossers, A. (2004). Evaluation of the mentor-mentee relationship in an occupational therapy mentorship programme. Occupational Therapy International, 11(2), 96–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.200

- Milner, T., & Bossers, A. (2005). Evaluation of an occupational therapy mentorship program. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(4), 205–211. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.05.0003

- National Disability Insurance Agency. (2020). National disability insurance scheme. Retreived March, 2021. https://www.ndis.gov.au/.

- Occupational Therapy Australia. (2013). Health professionals supporting each other: MentorLink education workbook.

- Occupational Therapy Australia. (2019). Professional supervision framework. Retreived September, 2020. https://www.otaus.com.au/practice-support/position-statements.

- Occupational Therapy Board of Australia. (2014). Supervision guidelines for occupational therapy. Retreived September, 2020. https://www.occupationaltherapyboard.gov.au/codes-guidelines.aspx.

- Sambunjak, D., Straus, S. E., & Marusic, A. (2006). Mentoring in academic medicine. JAMA, 296(9), 1103–1115. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1103

- Taff, S. D., Price, P., Krishnagiri, S., Bilics, A., & Hooper, B. (2018). Traversing hills and valleys: Exploring doing, being, becoming and belonging experiences in teaching and studying occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 25(3), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2018.1488606

- Wilcock, A. A. (1999). Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 46(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1630.1999.00174.x

- Wilcock, A. A. (2007). Occupation and health: Are they one and the same? Journal of Occupational Science, 14(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2007.9686577

- Wilding, C., Marais-Strydom, E., & Teo, N. (2003). Mentorlink: Empowering occupational therapists through mentoring. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 50(4). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1630.2003.00378.x

- World Health Organisation (WHO) & United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (2022). Global report on assistive technology [Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO]. Retrieved March 20, 2023, from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/354357.