ABSTRACT

The desire to reference, interpret, assign value, reconstruct, and envision the past is a critical matter within any culture – especially when expressed in the arts, which always supersede the procrustean limits of linguistic constructs and transcend the iterability inherent in the semantic postulations. The shadowy references in the arts have always illuminated, after scrutiny and in-depth examinations, the contemporaneous cultural sensibilities and emotional conditions that may be harbingers of novel beliefs and perspectives. In fact, one may say with some degree of certainty that history as is selectively constituted and reflected in the arts may well portend the future course of a people. This article is an attempt to examine the intersubjective, subliminal, and conscious portrayals of history, whether as metaphors or metonyms, in contemporary Iranian art. In this essay the contemplation of history conveys a preference for the arbitrary, random, and often fantastic constructs of the past that view history as ‘his’ or ‘her-story’. This ‘Critical-Creative’ approach plays a dominant role in undermining all metaphysical absolutes and Truth-centered ideas, be they religious, political, or philosophical. The outcome of these perspectives and aesthetic perceptions may well presage new social and political structures in the future of Iran.

To see is hence always to see on the horizon.

—Eamannuel Levinas

Meaning is of course in language, and forms also find their valuations in language and in the narratives that are shaped by the limitations of personal ontologies. But there is more than language, and this lies in the art, music, and dance that reside above and beyond the limitations and conceptual repetitions of language. Thus, the arts have uncanny access to the contingencies that manifest the social and cultural course of a people.

To begin, our conceptual question is concerned with the multitudinous ways of restructuring history. Generally speaking, the best classification of history is put forth by Friedrich Nietzsche in his Use and Abuse of History (Nietzsche Citation1957, 11–13), wherein he envisions a threefold constitution of history or of the past. His conceptual divisions are the ‘Monumental’,Footnote1 the ‘Antiquarian’,Footnote2 and the ‘Critical’.Footnote3 Although none of these categories exists in pure form and may overlap with the other two, nevertheless whatever the mélange, the category that dominates defines the type and bespeaks the prevailing intent. During this study I was, however, impelled to divide the ‘Critical’ into the ‘Critical-Structural’ and ‘Critical-Creative’. The latter, the ‘Critical-Creative’, clearly was not an issue in the nineteenth century studies of history. The ‘Critical-Creative’ highlights and foregrounds the subjective and the ontological and, thus, may be a significant reflection of the subliminal and intersubjective envisioning of a past. In this instance, the contemplation of history conveys the arbitrary, random, quantum, emotional, subjective, and even the fantastic constructs of the artists’ view of history as ‘his-story’.

It is this last approach, the ‘Critical-Creative’, that plays the dominant role and reflects the prevalent artistic outlook on history in contemporary Iranian art. The implications of these expressions, regarding present cultural outlooks in Iran, are phenomenal. I say this because the ‘Critical-Creative’ in contemporary Iranian art undermines all metaphysical absolutes and Truth-centered ideas, be they religious, political, or philosophical (Daneshvari Citation2014, 83–84). Contemporary expressions communicate the notion of flux and change rather than stability of belief and knowledge. This outcome may well presage new social and political structures in the future of Iran. The range of artists that are expressive of this outlook is wide and, significantly, a majority constitute the contemporary Iranian avant garde. Artists such as Siamak Filizadeh, Ferydoun Ave, Abbas Kowsari, Farideh Lashai, Azadeh Akhlaghi, Gohar Dashti, Shadi Ghadirian, Parastou Foruhar, Mandana Moghaddam, among others cited in this essay, may at first glance appear to embody various unrelated stylistic approaches and implied valuations. However, despite the spread of their pluralistic styles, they are after analysis united in the crucible of their inferred philosophical and iconographic similarities. One may easily say that the similarities are phenomenologically centered.

The attributes of contemporary Iranian art

What exactly justifies this study to evaluate the vision and portrayal of history in contemporary Iranian art or, for that matter, within any cultural setting? The fact that history has always been a part of the present cannot be denied, but the question of how the present views and reformulates the past, though perplexing, is also quite revealing regarding its own existentialist perceptions. To put it differently, Martin Heidegger’s comment that ‘The oldest of the old follows behind us in our thinking, and yet it comes to meet us’ (Heidegger Citation2003, 22) is a truism and indeed a reminder that the past is inextricably linked to the present; however, the depictions and the interpretations of the past remain open to the manifold structures of hermeneutics.

A recent show at the Los Angeles Museum of Art offered ample examples of historical signs in contemporary Iranian art (Komaroff Citation2018). Indeed, as I shall argue in this essay, the images copiously revealed present-day Iranian art’s subliminal and intersubjective demands to restructure and reformulate the past. In point of fact, as the displayed examples showed, even though the signs and symbols of history in present day Iranian art are not always in accord and are constituted variously by innumerable styles, yet they do convey a shared iconographic message regarding the view and role of history in contemporary Iran. It is a truism that in every period the view of history or the past betrays a randomly assimilated, randomly selected, and better yet, a polythetic and procrustean construction. Clearly, that these constitutions are to a great extent due to the exigencies of the present cannot be denied and as Benedetto Croce (1866–1952) has said, ‘All true history is the history of the present’ (Lukascs Citation1965, 181).

Therefore, what I have been concerned with in this study is not only the manner in which this past is viewed but also the isolation of the attributes in the expression of the historical signs – and this, so that my assessments of contemporary Iranian art may reflect the subliminal-intersubjective and conscious state of affairs in present-day Iran. In short, how are these evaluated historical signs attempts at a self-ordering system? Thus, it is best to start by isolating the traits that not only bind these works but also reflect contemporary Iranian art’s unprecedented views on history.

The traits that in the short span of this essay I have focused on are the concepts of heterotopia and heterocosm as constituted by intertextuality, given that various degrees of heterotopia and heterocosm appear to be a predominant feature of depicting history or the past in contemporary Iranian art.

Hetropotopian settings

Heterotopia, a term coined by Michel Foucault, serves as a prism through which incongruous realms are juxtaposed, leading to a dramatic confrontation of disparate worlds. These heterotopic spaces, characterised by their inherent dissonance and nonconformity, provoke a subversion of established values, often culminating in ontological nihilism. Foucault articulates heterotopia as a realm where disorder reigns supreme, a space where elements are so diversely situated that they defy traditional placement or categorisation.

There is a worse kind of disorder than that of the incongruous, the linking together of things that are … laid, placed, arranged in sites so very different from one another that it is impossible to find a place of residence for them. (Foucault Citation1970, xviii)

(Heterotopias) are radically discontinuous, and inconsistent, it juxtaposes worlds of incompatible structures. (McHale Citation1987, 44)

In the realm of contemporary Iranian art, this heterotopic vision is manifested within the works of a number of artists who bring to our attention, though perhaps to some degree or another unconsciously, the concept of history as a theatrical production always produced after the fact. These artists such as Siamak Filizadeh, Ferydoun Ave, Abbas Kowsari, Farideh Lashai, Azadeh Akhlaghi, Gohar Dashti, Shadi Ghadirian, Parastou Foruhar, Mandana Moghaddam, and many others not illustrated in this study convey a notion of history as fragmentary, hyperreal, inaccessible, irrational, and as various ontological constructs. Gone are the days when the past was wistfully recalled as ideal, monumental, truthful, and privileged.

Of primary interest are the works of Abbas Kowsari, whose photographs demonstrate the intertextuality of the reconstituted theatre of history with its attendant and coeval reality. Kowsari is a journalist photographer, whose aesthetical choices for reportorial selection best unfold the verisimilitude of intersubjective expressions of its own time and reveal more uncannily the meta-structure of the aesthetical expression and creative advancement in contemporary Iran. The choices of a journalist photographer may show a greater degree of relation to the zeitgeist and, to put it differently, to the broadest common denominator of a time’s emotional state of vision. In addition, Kowsari’s uncanny ability to choose those scenes and moments that transcend the platitudinous conveyances that ‘define the history, the purpose, and even the absurdity of the cultural and personal fates’, (Daneshvari Citation2014, 283) has been repeatedly conveyed.

Kowsari’s ‘Reds and Greens’ is an interesting series regarding the heterotopia of history and the concept of reality in contemporary Iran. The photographs of this series display how the grandeur of the past turns false and wholly dreamed up only because of the inordinate contrast with its accompanying reality. On the surface of it, the ‘Reds and Greens’ photographs show documentary imagery of the Shiite passion play actors parading in public spaces, as one facet of reenacting the martyrdom of the Shiite Imam Hussein that is yearly performed in various Iranian urban spaces. Here, however, unlike other cohesive and unequivocal and un-ambiguous representations of this religious rite by, for example, Sadegh Tirafkan’s ‘Ashura’, Kowsari, whether consciously or subconsciously, has shown that the theatre of the myth is incongruous and discordant with the ennui of the quotidian existence. His eye for the colliding spaces of myth and reality, the contrasting spaces of memory and the ineffable present shockingly evokes the hyperreality of the historical constructs. In , one set of images belongs to the place and the other set of images is brought to that place. The past – reenacted in a glittering, dynamic, colourful, and larger than life fashion – unfolds on the abject and ordinary stage of daily life, thus raising the point that these historical settings must have been originally as pitiful, mundane, and messy as the present spaces that they now parade in. The conjoining of the blasé-banal with the extraordinary-miraculous proves that the theatre of history is framed by such concepts as politics, nationality, religion, cultural identity, and the search for absolute meaning, whereas the mundane world is a state of flux preoccupied with motion and entropy. The culturally construed, colourful, ideal, and super-human religious reenactments of ‘Reds and Greens’ highlight the differentiation between the finite reality and the infinite imagination. The fact that, in these photographs, history is so inventively restructured and the present, serving as the backdrop, is so utterly doleful reminds me of Goethe (1749–1832), who wrote that the Trojan war was ‘neither epic nor tragic, and in a true epic treatment, [could] only be seen in the distance either from in front or behind’. (Lukascs Citation1965, 308) The colourful, heroic, and stirring theatre of the myth from more than a millennium ago is a construct of modern imagination rather than of proper recollection. This understanding suggests the oft-repeated dictum in postmodernism that I have already referred to, namely that history is his-story. His-story is not only the end of history but acknowledges that the relation between meaning and being is, and has always been, assumed.

So, what allows for this kind of relation to so easily assert itself without either examination or objection? Perhaps, it is partially due to the fact that only metaphysical beliefs, best expressed through theatrical and symbolic productions, survive because they evoke a sense of meaning and purpose that life itself lacks. They show that history can be legitimised only when it transcends actualities by appealing to dreams and to superhuman phenomena for the sole purpose of positing meaning either to help legitimise powers or to comfort by elucidation of powers where there are none.

Shifting from the journalistic photography of Kowsari to the digitally manipulated photographic art of Siamak Filizadeh, we discern an artist whose subject matter, though practically all historical-referential, offers in a vein similar to Kowsari’s photographs, the deconstruction of the history that it depicts. However, given that his works are not journalistic and belong to the creative sphere, some have viewed his art as contrivance and artifice, others have explained the art via relating the titles of his work to classical historical events and, thus, as explanations for his imagery. Nevertheless, these works are so radically personal that they defy any relevance to the social science of recorded history. In fact, neither opprobrium nor approbation may explain his work. Neither a reading of classic epistemic history derived from the titles, nor the threading of psychoanalytic theories may illuminate them. We must place our emphasis on the structure of his work and recover systematically his artistic subversions and actualisations.

In most of Filizadeh’s works, any space is an intertextual mélange of Iranian historical persona, especially of the Qajar ruler Nasir al-Din Shah and his related characters, concomitant with transmuted compositions of European Renaissance art, modern technological instruments, natural and historical signs, and more. Works in his ‘Underground’ series titled ‘Mirza Reza Khan,’, ‘Nasir al-Din Shah with the British Ambassador’, and ‘Nasir al-Din Shah with the Russian Ambassador’ all are marked by trans-historical signs (culled from various cultures) and occur or transpire in trans-temporal settings; though literal in titles, they are, nevertheless, hyperreal and fantastic in their compositional schemes and inferences. For example, in ‘Mirza Reza Khan’, the assassin of Nasir al-Din Shah, the violence directed against the king is conveyed through erratic and chimerical pathways, structured by intertextual signs that allude to the assassin’s deed by averting the Shah’s assassination through the 1976 American movie ‘Taxi Driver’, wherein the troubled protagonist, played by Robert De Niro, assassinates a pimp. What these two parallel universes share is the meta-structure of assassination, but they differ wholly otherwise. The equivalence of two unrelated events establishes a relation of the metaphysical sensations concerning assassination, but it also offers the very fissure and breach of historical phenomenology. It is easy to conclude that Filizadeh’s titles are literal, but his images and compositional constructs are all figurative and may be understood only as metaphors, but not of historical facticity. These projections are all ontological visions and do not fit the rigorous epistemological and critical assessments of history as practiced by historians. The heterotopia of his work is constituted by the envisaging of the banal as fantastic and the fantastic as banal.

Of course, one may rightly argue that any individual’s perception of history or an event is coloured by the dizzying complexity of his or her own personal aesthetic, intersubjective, and experiential prisms. In brief, the complexity of any perception is truly beyond the sundering and sorting powers of linear, rational, and structured thinking. Thus, here one may safely assume that Filizadeh is reflecting the consciousness of history in the intersecting and intertextual pathways of a perceiving and composing mind. The ontological representations of unfounded and untrue traits (e.g. the Shah wearing modern female leggings or chickens hosted in the royal room of Anis al-Dowleh) and other similar heterotopian and heterocosmic expressions reveal the possibility of annexing a factual historical space to personal fantastic imagination. Heterotopias and heterocosms always undermine metaphysical stability, especially when the level of intertextuality and the individual chimera is excessive and borders on the fantastic.

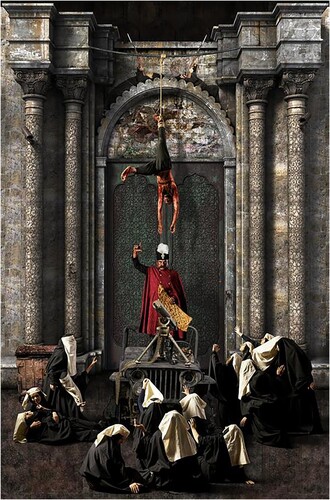

Filizadeh’s startling assemblages of discordant, incongruent, and intertextual spaces, shifting between illusion and reality, are easily discerned in the ‘Bread Riots’, a historical event of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, where Nasir al-Din Shah, standing upon a 1950s military jeep equipped with an antiquated machine gun, holds a sheet of sangag bread (). The women rioters, donned with white cloths as headdresses resembling nuns in habits, crouch at the king’s feet while the body of Tehran’s mayor hangs by one leg above them. The bread riots, the hanging of the mayor, and the mud-covered faces of the women demonstrators are all factual, but the composition of the event is fanciful and imagined. Compositionally speaking, the scheme with the arched niche and the hanging figure is an intertextual intrusion from the European Renaissance, best referring to Piero Della Francesca’s ‘Madonna and Child with Saints’ (1472), where the suspended egg is now replaced by the tortured body of the mayor and the Madonna by the king. In fact, the impact of renaissance imagery in Filizadeh’s work is quite prevalent. For example, among a few other series of images by Filizadeh on the execution of Mirza Reza Khan, his ‘Sham Ajeen’ best depicts the burning-candle pierced body of the Shah’s assassin echoing the arrow-pierced body of St. Anthony in Italian Renaissance art. Another image of Mirza Reza Khan’s multi-lesioned and lacerated body includes women recording the event with their cell phones. The appeal to Italian Renaissance imagery and contemporary technology, intertwined and woven intertextually with Iranian themes and motifs, is a dominant feature of Filizadeh’s work as exemplified by the Pieta-like composition of the ‘Death of Amir Qasim’ and the theme of ‘Resurrection’, wherein the latter, the Shah is modelled after Doubting Thomas. In ‘Vigor’, Nasir al-Din Shah holds a machine gun, mannered after Saddam Hussein, and stands on a balcony resembling the early Renaissance pulpits. These expressions are heterotopian and heterocosmic, the former because of its incongruous and discordant features and the latter because of its mélange of multiple worlds. This further leads us to a novel thought, namely, that when heterotopias, zonal contrasts, and incongruities formulate a sense of history, then the outcome necessarily evokes fantastic zones bearing a lack of perspicuity and lucidity born of the clash of illusion and reality.

Filizadeh’s works, as we have discussed, are quite fitting of a trait that has been popular in the western postmodern arts, namely, the intertextuality of retour de personages.Footnote5 Retour signifies the recovery and restoration of names or images from the past but discarding or removing their original attributes. For example, in ‘Rustam II, The Return’ (16 digital prints, 2009), Filizadeh has brought Shahnameh’s Rustam back as a character in the lore of twentieth-century body builders, soldiers, and theatrical dramatis personae. This Rustam is wearing jeans and carries modern weaponry of war. In our analysis of Filizadeh’s ‘Rustam’ Series, however, we must preemptively acknowledge that while no two periods have ever produced a Shahnameh that is verifiably a true copy or reflection of its assumed original, the earlier periods nevertheless have always attempted to keep a distance between their own Shahnamehs and earlier models by projecting, at least, an antiquated air of weaponry and outfits in their portrayals. Thus, it is obvious that the earlier simulative and copying artists had placed some distance between themselves and the work that they had facsimiled. Filizadeh, however, has drastically narrowed this distance between himself and his chosen historical subjects to zero, and this contributes dramatically to the fantastic air of his compositions. For him the old is the present with all its personal conceptualisations – the historical characters are present-day persona, and this undermines the presence of an archaea.

The absence of an archaea,Footnote6 be it the originary Shahnameh or the originary of Kowsari’s images of the Shiite passion plays, destabilises the concept of knowledge and by extension history. Filizadeh’s historically referenced imagery and Kowsari’s captured images of Shiite religious theatres reveal, being subconsciously constructed and framed, the distinctive nature of history as narratives born of emotion and the ontological will to power. These works have shown that what truly remains from the past are names and dates, but their contextual emotional valuations and detailed physical unfolding are a matter of the hermeneutical games of their settings. One significant implication of this realisation is, above all, that contemporaryIranian art indicates a shift from the ontology of knowledge to the impossibility of knowledge. I can say with a high degree of certainty that the notion of the impossibility of knowledge is the emotional perspective across a significant expanse of modern Iran’s visual arts.

However, looking only at Filizadeh’s images I am inclined to think of his presentations of history as the paragon and the exemplar for a passage in Derrida’s Margins of Philosophy:

… [T]hink of a writing without presence and without absence, without history, without cause, without archia [sic], without telos, a writing that absolutely upsets all dialectics, all theology, all teleology, all ontology. (Derrida Citation1982, 67)

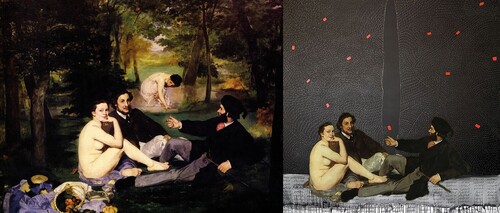

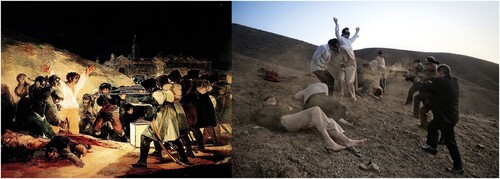

The phenomenon of retour de personage is especially pertinent and germane to recursive expressions, copies of copies, especially across cultural and temporal sectors. One example is Farideh Lashai’s ‘Déjeuner au Park Mellat’, (2010, ), which represents one of her three appropriations of Manet’s ‘Déjeuner sur l’herb’ (1863, Réunion des Musée Nationaux). Manet’s ‘Déjeuner’ was after Marcantonio Raimondi’s tapestry of the same theme, itself after the now lost painting of Raphael’s ‘Judgement of Paris’, and further back to earlier Roman examples. Other Iranian examples in this same vein of recursive appropriations are Gohar Dashti‘s ‘Home’ series (, ‘Home # 6’, of the Home series, 2017), which represents reformulations of Walter De Maria’s ‘The New York Earth Room’ at 141 Wooster Street in New York (1977); Arman Stepanian’s ‘Card Players’ (2008), simulating Cezanne’s ‘Card Players’ (1890s, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), in which Stepanian includes a copy of Cezanne’s original on the wall adjacent to his ‘Card Players’; and Azadeh Akhlaghi’s ‘Execution of Bijan Jazani, 1975’ (), 2015 after Francisco Goya’s ‘The Third of May, 1808’ (1814, Museo del Prado, Madrid) and Manet’s ‘Execution of Emperor Maximilian, 1863’ (1868–1869, Kunsthalle Manheim).

Figure 3. Left, Edouard Manet, Déjeuner sur l’herb (1863). Right, Farideh Lashai, Déjeuner au Park Mellat (2010).

Figure 4. Left, Walter De Maria, The New York Earth Room at 141 Wooster Street in New York (1977). Right, Gohar Dashti, Home #6, from the ‘Home’ series (2017).

Figure 5. Left, Francisco Goya, The Third of May, 1808 (1814). Right, Azadeh Akhlaghi, Execution of Bijan Jazani, 1975, from the ‘Eye Witness’ series (2012).

To discuss only three examples of recursively structured work, necessitated by the limitations of this venue, I am limiting my analysis to Farideh Lashai’s ‘Déjeuner au Park Mellat’ (), Dashti’s ‘Home’ series (), and Akhlaghi’s ‘Execution of Bijan Jazani’ (Derrida Citation1982, 67) (). The primary question is, What can we say about this type of intertextuality, namely, reiterations or copies of copies, especially when they are transzonal and transtemporal? First, we know that serial simulations or copies of copies seem to establish corresponding parities between or among structurally and thematically analogous indicative signs.Footnote7 The question remains as to whether these indicative signs may also function as expressive signs, namely, to communicate a new meaning within their own reiterated context? The primary response in ‘Dejeuner au Park Mellat’, the ‘Execution of Bijan Jazani’, and Dashti’s Home series is an inclination to refer back to Manet, Goya, and De Maria, respectively, for meanings that may be or are embedded in their original models. This, however, soon turns moot as the adopted iterability at each level of simulation, even if a perfect copy, embodies variations (culturally, morphologically, zonally, temporally, individually, etc.) that is not only divorced from the original’s meaning but is also as a copy without a local ground and remains alien to its own context and local iconographic content.Footnote8 For example, in Akhlaghi’s ‘Execution of Bijan Jazani’, which is partly Francisco Goya’s 1814 ‘Third of May, 1808’, partly Manet’s 1868–1869 ‘Execution of Emperor Maximilian’, and partly Akhlaghi, the facts regarding the moment of Jazani’s execution are not at play. Neither are evident the contemporaneous facts of the more subtle recursive works of Lashai’s ‘Dejeuner au Park Mellat’ after Manet, and Dashti’s ‘Home #6’ after De Maria. Any copy or simulation in a transzonal context is devoid of historical facticity and at best embodies valuations in terms of its psychological and aesthetic inclinations.

I say this because each recursive level of expression is in fact a new ontological level (McHale Citation1987, 112–113), and its meaning must be reconstituted within each and every reiterated level. For example, Lashai’s ‘Dejeuner au Park Mellat’ which is primarily understood through another work and its multifarious interpretations, does suspend and undermine the ostensive historical character of the copy and vice versa, unless the observer is not aware of its structural configuration. Thus, all these copies of copies demonstrate chasmic iconographic jumps, especially even more when transzonal. Lashai’s or Akhlaghi’s or Dashti’s expressions uniquely further the opacity and even the incoherence of their expressive historical signs. A piece of the past, whose meaning is irrelevant, is an indicative sign for a presence that is likewise without expressive ground, of course, inner soliloquies excluded. What matters to us regarding their view of history is that the past is the present and the present is also the past. There are of course differences between and among the copies, but what remains unalterable is that the cause and effect (the origin and the copy) can exchange places and this is metalepsis. Nothing undermines the concept of apodicticity and verifiable historical truth more potently than metalepsis. In Lashai, this complexity is furthered because she complements the two primary levels of the copies by projecting videos upon them, one synchronic and the other diachronic. Lashai’s final product is a collage that foregrounds fabulation or confrontations of discontinuous worlds vis a’ vis a past, thus expressing a heterotopian and heterocosmic outcome. At best, meanings in such configurations survive as metaphors within a pool of discursive interpretations.

Another important aspect regarding the expressive powers of copies of copies is, for example, in Akhlaghi’s ‘Execution of Bijan Jazani’. The two cohabiting spaces, one Spanish from 1814 and the other Iranian from 2012, as I have said previously, not only remain alien to one another but also only generate meaning through the universal signifiers and metaphysical powers of language or the cross transference of emotions regarding political execution, injustice, sacrifice, brutality of power, and other universal values salient to execution – all predicated by certain morphological similarities and not by the unfolding realities of the moment of Jazani’s execution. In Dashti, the concept of nature entrapped in human constructs, the immeasurable earth within measurable confines of human constructs, is the universal signifier and yet neither work may go beyond that except for the differences in the western and eastern architectural models and the typology of the earth used, one with plants and the other without. Lashai’s ‘Dejeuner au Park Mellat’ shares with Manet similar universal concepts as individuation and gathering outdoors.Footnote9 In other words, within the chain of copies, what remains to some degree of certainty is the default linguistic reduction of the totality to its smallest common denominator, namely the thematic labels in language. Of course, having said all that, for most readers outside the field of art history, the intuitive response is primarily aesthetical.

More so, the strategies adopted by these artists reveal an important facet of the philosophical undertones regarding their views of history. For example, Akhlaghi’s art is indeed mostly eschatological and hypodiegetically constructed as are the Shiite rituals captured by Kowsari in his ‘Reds and Greens’. Both of these hypodiegetic theatres of art and life are edited for maximum dramatic impact. As Kowsari’s journalistic photographs expose an incommensurable, glorified, sacrosanct, and biased restructuring of the past constituted by the ruling clergy, Akhlaghi offers a similar incommensurable, unhallowed, and politically biased restructuring of the Pahlavi regime (1925–1979). Akhlaghi’s valorisation of the past regime is as mono-syllabic and non-dialectically structured as is the theatre of Ashura constituted by the clergy. Kowsari, as a creative observer, and Akhlaghi as a creative producer, in a strange twist of outcomes, are both the Parousia of Shiite salvation, one religious and the other political.

Conclusion

Precisely because history means this inner process … . [t]hat History is foremost a history of the soul.

Jan Patočka, Heretical Essays in the Philosophy of History (Patočka Citation1996, 103)

Somehow or another, contemporary Iranian art undermines and, at a minimum, opacifies the past and delegitimises the narratives that stand as archaea. Examples are many, but the demand for brevity impels me to cite only a few. Among the artists who subvert and erode the archaea that grounds history as a metaphysical model for existential valuations are Mandana Moghaddam’s ‘Cube’, also called ‘Alethia’ (Truth), installed at the Gothenburg Art Museum of Sweden. The cube in Islam and its ancient precedent belief systems symbolised God’s order, His throne, and the image of His metaphysical perfection and values, as well as the navel of the earth and the site of the creation of Adam. Yet, the innards of this Truth hold stacks of newspapers next to a red ball. The former is a sign of the quotidian man-made narratives and circadian reports, and the red ball stands as the reified symbol of the heavenly light. In practically, most of Moghaddam’s work, such as ‘Sara’s Paradise’ (2009) or her ‘Chelgis’ series, the essence of metaphysics as a physical ploy is unveiled. Similarly, the items in Shadi Ghadirian’s ‘Everyday’ series (2001–2002) convey in stark terms that the archaea for the veiling of the female (chador) is no more than the male’s desire to facilitate his own daily demands of eating and other physical gratifications. The chasm between the philosophically unyielding metaphysics or the so-called sacred valuations and the daily demands of the quotidian reality is the staple of contemporary Iranian art, and I refer the reader to the image of Parastou Forouhar’s ‘Trauerfeier’ (‘Funeral Service’, 2003), devised of office chairs covered with Shiite funerary banners. The heavenly phenomenon is now disclosed as rhetoric on textiles, and the chairs exemplify the only possible heavenly seat of the divine powers.Footnote10

All of these works communicate the concepts that the depth of being lies on the surface of being and that metaphysics is physics renamed. They all reference, after examination, that the hardest thing to know is not what we have assumed as an origin or as a non-earthly source of Truth, but it is the quotidian manifestations of life and daily presences. The usual daily or, as Nietzsche has put it, ‘ … The familiar is the usual, and the usual is hardest to know, that is to see as a problem, that is to see as alien, as distant, as outside’. (Morgan Citation1965, 87). It is the hardest because it is the flux, and the unpredictable motion and as a result the unicity and rigidity of the metaphysical constructs are accepted as relief from the reality of the aleatory existence.

It seems clear that this mode of critical-creative in contemporary Iranian art is, in my opinion, a result of the exhaustion of possibilities of belief in transcendent ideologies and peerless metaphysical-cultural and religious declarations. It also signals a philosophical nihilism where fragmentation and individuation bespeak divorce from the pervading belief systems and the suffused historical transcendental narratives. One significant implication of this historical referencing is that the idea of history, as expressed in contemporary Iranian art, is undermined as an intellectually accessible and systematically explicable phenomenon. Among the artists discussed who express the dominant of contemporary Iranian art on history, most are either critically questioning or are creatively reconstructing, leaning often in favour of the fantastic, chimerical, and the quixotically envisioned phenomena rather than the monumental in history. In fact, the idea of history comes across as constructs without an accessible ground of germination or a reliable and predictable telos.

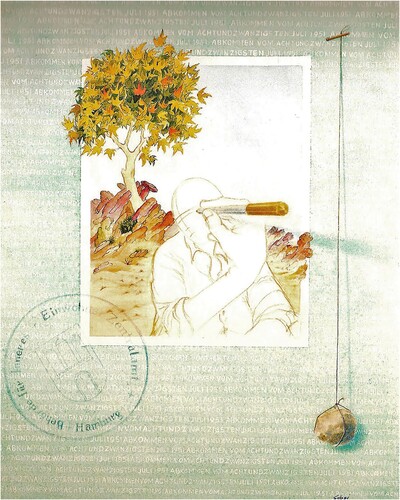

There is a much-neglected 1987 work by Mahmoud Sabzi, titled ‘Metamorphoses’, that in one sense encapsulates the dilemma of modern Iran with its own past and present. Sabzi’s watercolour embodies two incongruous worlds, one depicting an envisioned and dreamt-up ideal past conveyed by a tree of variegated colours copied from a Timurid miniature, and the other showing the artist in the act of redrawing and restructuring himself in German exile. The seal of German immigration alludes to his presence in an alien world, and the primitive plumb line is perhaps a sign of the desire to rebuild and restructure himself in exile (). This paradox of simultaneous presence in a history that is also absent is not only the focal point of this work but also of contemporary Iranian art. In today’s Iran, history’s feigned and cloaked presence is precisely the expression of its absence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Abbas Daneshvari

Professor Abbas Daneshvari is the author and editor of 10 books and forty plus articles. He was educated at the California State University, East Bay; Brandeis University, the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and received his PhD from UCLA. He has taught at the University of California at Berkeley from whence he became the recipient of a Fulbright Scholar in Egypt during 1981-82.

Notes

1 The ‘Monumental’ view of history aims to evoke a sense of tribal ownership, grandeur, and idealism. It proffers a transcendent and heroic vision of the past, always attuned to the ideal deed and the promise of a utopian telos. Though it may seem a platitude, the monumental view of history revives the past mostly to give us access to such concepts as heritage and identity. A few examples are such works as the 1926 ‘Shahnameh Majlis’ of Hadi Khan Tajvidi, the 1950s ‘Rustam Battling Sohrab’ by Hossein Golar Aghasi, and the 1966 ‘Sokhan Ma‘rifat az Halqeh Darvishan Pors’ by Abu Talib Moghimi Tabrizi, among many others.

2 The second type of historical envisioning is the ‘Antiquarian’. At first glance the antiquarian perspective conveys the objective and transparent state of historical perception. The works fall within the mimetic mode of conveyance as reminders of bygone days or as archeological curiosities, though their scope of the past is always limited to the survived signs and their own ontological gravitations. Initially, the historical fragments depicted and reflected in the antiquarian outlook do not offer a total or comprehensive view of the past. However, the appeal of these selected images is fully dependent upon the prevailing narratives regarding a time and a period to which the image belongs. These so-called mimetic expressions, as exemplified by the works of Antoin Sevruguin (1851–1933), Katayoun Karami (b. 1967), Najaf Shokri (b. 1980), and Newsha Tavakolian (b. 1981), among many others, shall in time, depending on the hermeneutical structures applied, easily revert the mimetic aspects of their works into the romantic-monumental or the critical.

3 The ‘Critical’ view of history may be viewed as a twofold or a two-pronged phenomenon. The first, the ‘Critical-Structural’, is epistemological as exemplified by the academic historians who seek the recording and interpretation of the past as a social-science so that it may portend to the understanding of the past and even, in some cases, the prediction of future events. In the arts, the ‘Creative-Structural’ is often epistemic and is focused on discovering patterns within history to ultimately gain access to its workings and manners of unfolding. One such example is the graphic works of Koorosh Shishegaran (b. 1944) that, in spite of their artistic license, easily fit the notion of the Critical-Structural. The Critical-Creative is a postmodern phenomenon in contemporary Iranian art as discussed in this essay.

4 Metalepsis, as referred to in this essay, conveys the reversal of the hierarchy of cause and effect, by which the effect precedes the cause.

5 Retour is an amply discussed concept in modern and postmodern literature. For summaries see Aranda (Citation2004, 351–362); McHale (Citation1987, 57–58).

6 Without origin and originary cause there is no archaea, no meaning and no teleology.

7 Indicative signs are signs that stand for, or point to, other signs.

8 Of course, if examined outside the context of art history, any meanings read over the head of these works are born of the subjective and ontological spheres of the onlookers and are outside of the sphere of philosophical analysis.

9 Manet’s ‘Déjeuner’ symbolised the transformation of gods into common men and his models stood as transformed survivals of the ancient and Christian concepts of divinity, exemplifying a parallelism to the Nietzschean ‘Death of God’. However, Lashai’s ‘Déjeuner au Park Mellat’ is without any such archaea-models within the Iranian context.

10 I refer the reader to Daneshvari (Citation2014) for a host of such examples.

References

- Aranda, Daniel. 2004. “Les retours hybrides de personnages.” Poétique 139/3: 351–362.

- Daneshvari, Abbas. 2014. Amazingly Original: Contemporary Iranian Art at Crossroads. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1982. Margins of Philosophy, translated by Alan Bass. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Foucault, Michel. 1970. The Order of Things: An Archeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Pantheon.

- Heidegger, Martin. 2003. Philosophical and Political Writings, edited by Manfred Stassen. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Komaroff, Linda. 2018. In the Field of Empty Days: The Intersection of Past and Present in Contemporary Iranian Art. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1969. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority, translated by Alphonso Lingis. Pittsburg: Duquense University Press.

- Lukascs, Gerog. 1965. The Historical Novel, translated by Hannah and Stanley Mitchell. London: Merlin Press.

- McHale, Brian. 1987. Postmodernist Fiction. New York and London: Methuen.

- Morgan, Allen George. 1965. What Nietzsche Means. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1957. The Use and Abuse of History. 3rd ed. New York and Indianapolis: Bobbs Merril Company.

- Patočka, Jan. 1996. Heretical Essays in the Philosophy of History, translated by Erazim Kohák, edited by James Dodd with Paul Ricoeur’s preface to the French edition. Chicago and La Salle: Open Court.